Open Journal of Stomatology

Vol.3 No.1(2013), Article ID:28735,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojst.2013.31006

Patients with dental hemorrhagic complications undergoing warfarin therapy exhibit excessive international normalized ratio prolongation: A report of 2 cases

![]()

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Saitama Medical University, Moroyama-machi, Japan

2Developmental Biology, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, USA

Email: tsato@saitama-med.ac.jp

Received 16 January 2013; revised 23 February 2013; accepted 1 March 2013

Keywords: Warfarin Therapy; International Normalized Ratio; Hypoalbuminemia; Vitamin K Deficiency

ABSTRACT

Dental hemorrhagic complications, including postoperative bleeding and traumatic hemorrhage as emergency cases, often occur in patients undergoing oral anticoagulant therapy such as warfarin therapy. Recent research recommends that warfarin dosage should be assessed every 12 weeks. Therefore, most physicians generally accept international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring at longer intervals. However, cases are encountered in which the INR prolongation is observed despite of invariable dosage of warfarin. In this report, we present 2 cases of patients with dental hemorrhagic complications undergoing oral anticoagulant therapy who exhibited excessive INR prolongation. These patients exhibited decreased appetite and hypoalbuminemia. We speculate that longterm appetite loss resulted in the increase in the serum concentration of free warfarin and vitamin K deficiency. Our study indicates that we should notice malnourishment when we treat patients who have undergone warfarin therapy with dental surgical procedures. It is recommended that measurement of INR just before a dental surgical treatment.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dental hemorrhagic complications, including postoperative bleeding and traumatic hemorrhage as emergency cases, often occur in patients undergoing oral anticoagulant therapy. Warfarin deters clot formation by inhibiting vitamin K-dependent synthesis of clotting factors and is commonly used in anticoagulant therapy to prevent thromboembolism such as venous thromboembolism and ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) [1,2]. Warfarin acts by inhibiting the synthesis of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors, which include Factors II, VII, IX, and X, and the anticoagulant proteins C and S. Warfarin is thought to interfere with clotting factor synthesis by inhibition of the C1 subunit of vitamin K epoxide reductase enzyme complex, thereby reducing the regeneration of vitamin K1 epoxide. Therapeutic levels of warfarin are measured using the international normalized ratio (INR). To check INR prolongation is useful for the diagnosis of oral anticoagulant therapy. American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology and European Society of Cardiology recommend an INR range of 2.0 - 3.0 to prevent thromboembolism in patients with AF [3]. However, the Japanese guidelines recommend that target INR levels for patients with nonvalvular AF range from 1.6 - 2.6 [4]. Because approximately 1% patients for whom the warfarin therapy was withdrawn for dental surgical treatment or endoscopy experienced severe thrombosis, became disabled, or died [5,6], continuous administration of a maintenance dose of warfarin is recommended during dental surgical treatment [7-9].

Although the American College of Chest Physician guidelines recommend that INR monitoring should be performed at a maximum interval of 4 weeks [10], recent research recommends that warfarin dosage should be assessed every 12 weeks. Therefore, most physicians generally accept INR monitoring at longer intervals. However, cases are encountered in which the INR prolongation is observed despite of invariable dosage of warfarin. Here, we present 2 cases of patients with dental hemorrhagic complications undergoing oral anticoagulant therapy who exhibited excessive INR prolongation associated with hypoalbuminemia and vitamin K deficiency.

2. CASE REPORTS

The 2 cases reported in this study are of patients who were diagnosed between 2007 and 2011 at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Saitama Medical University Hospital.

2.1. Case 1

An 83-year-old female patient with hemorrhage after teeth-extraction (teeth 35, 36, and 37) was transported to our hospital by an ambulance in 2011 (Table 1). Four days before the transfer to the hospital, her teeth were extracted a primary visiting dentist at her residence. Both 250 mg cefaclor (Kefral®) 3 times daily were prescribed for 2 days and 400 mg acetaminophen (Calonal®) at 1 time were prescribed. She took cefaclor for 2 days and acetaminophen twice. Persistent minor hemorrhage occurred after tooth extraction, and the dentist advised her and her family to compress the wound surface with a surgical gauze. Her medical history revealed paradoxical cerebral embolism, which may have been caused by patent foramen ovale, as diagnosed at our hospital in 2006 that was subsequently followed up by a primary care physician. For the last month, she experienced a decreased appetite because of dental trouble, and ate only 1 meal per day. She was treated with the following medication for each disease: 2.5 mg warfarin potassium (Warfarin®) per day for cerebral embolism, 25 mg fluvoxamine (Luvox®) and 400 mg sodium valproate (Depakene®) per day for a major depressive disorder, and 20 mg fu-

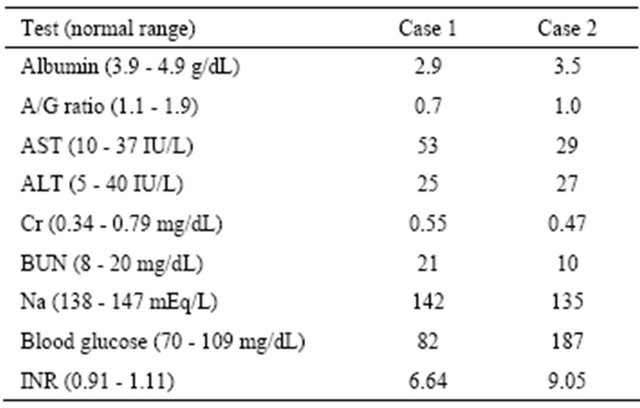

Table 1. Background of the 2 patients.

rosemide (Lasix®) per day for hypertension. INR monitoring was conducted every 2 months through follow-up. The most recent INR value was 1.83, taken almost 1 month before presentation. Laboratory data on the day of hospital visit showed that both serum albumin and the ratio of albumin to globulins (A/G ratio) were low (2.9 g/dL and 0.7 g/dL, respectively), suggesting that the patient was malnourished (Table 2). Although aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was slightly high (53 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was within normal limits (25 IU/L), indicating that the liver function was normal. INR value was 6.64. She was diagnosed as having secondary hemorrhage after tooth extraction. Hemostasis was achieved using Surgicel® and suture. Menatetrenone (15 mg/day) was prescribed orally, and the patient was treated with heparin under hospital care. Her INR value decreased to 1.49 after 4 days.

2.2. Case 2

An 82-year-old female patient with hemorrhage after injury was transported to our hospital by an ambulance in 2007 (Table 1). She had tripped and fallen on her face in the house and was experienced a hard blow to the mandible. Her medical history revealed that she had been treated for breast cancer and had cardiogenic embolism that was diagnosed at our hospital in 2006 and that was followed up by a primary care physician. She reported a decreased appetite and consumed 1 or 2 meals per day for the last 3 months. She was treated with the following medication for each of the disease: 3.0 mg warfarin potassium (Warfarin®) and 5 mg nitroglycerin (Nitroderm TTS®) per day for cardiogenic embolism, 2.5 mg glibenclamide (Euglucon®) per day for diabetes mellitus, 6 g sodium chloride (Sodium chloride®) per day for hyponatremia, 0.25 mg brotizolam (Lendormin®) per day for insomnia, and 15 mg lansoprazole (Takepron OD®) per day for gastric ulcer. She was followed up by INR monitoring every 6 months, with her most recently recorded

Table 2. Laboratory data for 2 cases.

A/G: albumin to globulins; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; Cr: creatinine. BUN: blood urea nitrogen.

INR value being 2.02. Laboratory data on the day of her first visit showed that both serum albumin (3.5 g/dL) and A/G ratio (1.0) were low, suggesting that she was malnourished (Table 2). Her INR value was 9.05. She was diagnosed as having alveolar bone fracture of the mandibular bilateral central incisor and gingival laceration. We extracted her teeth (31 and 41) and inserted Avitene® sheet in the extraction socket with a suture. She was administered menatetrenone (10 mg/day) intravenously under hospital care. Her INR value decreased to 1.65 after 2 days.

3. DISCUSSION

In this report, we presented 2 cases of INR prolongation. We adopted “above 4.50” as the standard of INR prolongation as reported previously [11]. The risk of overanticoagulation is increased by the following factors: poor drug compliance, hyperthyroidism, hypertension, renal failure, long-term administration of antibiotics and analgesics, hepatic dysfunction, loss of vitamin K and hypoalbuminemia [11-13].

The cognitive ability in both patients was normal despite being elderly, suggesting that their drug compliance was good. As mentioned previously, hepatic function was normal in both the cases. Moreover, both the patients did not have hyperthyroidism. Although the patient in Case 1 had hypertension, the disease progression was stable. The patient in Case 2 had diabetes mellitus, but renal failure was not complicated. Renal function in both the patients was normal. Antibiotics and analgesics were prescribed in Case 1. Recent studies demonstrated that the consumption of antibiotics or analgesics for a long time (i.e., for more than 7 days) may elevate INR values [14-16]. However, the duration of administration in the present case was so short that the probability of INR prolongation was very low.

In the elderly, poor oral intakes of dietary vitamin K is the most likely explanation for the marked prolongation of INR despite a stable dose of warfarin [17]. We could not exclude the possibility that both cases were insufficient for taking vitamin K. On the other hand, hypoalbuminemia due to appetite loss exhibits a marked prolongation of INR [18]. Since warfarin strongly binds to serum albumin [19], low levels of serum albumin increase the risk of INR prolongation [20,21]. A slight decline in albumin can also increase the INR value [18]. In our cases, serum albumin as well as A/G ratio was low, suggesting that hypoalbuminemia increased INR value. We speculate that long-term appetite loss resulted in the increase in the serum concentration of free warfarin and vitamin K deficiency. This case report indicates that we should attend to long-term appetite loss in elderly people undergoing oral anticoagulant therapy. Our study indicates that we should notice malnourishment when we treat patients who have been taking oral anticoagulant therapy with dental surgical procedures. It is recommended that measurement of INR just before a dental surgical treatment.

REFERENCES

- Owens, C.D. and Belkin, M. (2005) Thrombosis and coagulation: Operative management of the anticoagulated patient. Surgical Clinics of North America, 85, 1179- 1189. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2005.09.008

- Menke, J., Luthje, L., Kastrup, A. and Larsen, J. (2010) Thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation. American Journal of Cardiology, 105, 502-510. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.018

- Fuster, V., Ryden, L.E., Cannom, D.S., Crijns, H.J., Curtis, A.B., and Ellenbogen, K.A., et al. (2006) ACC/AHA/ ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 2001 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation): Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation, 114, e257-e354. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177292

- Group, J.J.W. (2010) Guidelines for pharmacotherapy of atrial fibrillation (JCS2009): Digest version. Circulation Journal, 74, 2479-2500. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-88-0001

- Wahl, M.J. (1998) Dental surgery in anticoagulated patients. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 1610-1616. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.15.1610

- Blacker, D.J., Wijdicks, E.F. and McClelland, R.L. (2003) Stroke risk in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing endoscopy. Neurology, 61, 964-968. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000086817.54076.EB

- Perry, D.J., Noakes, T.J. and Helliwell, P.S. (2007) Guidelines for the management of patients on oral anticoagulants requiring dental surgery. British Dental Journal, 203, 389-393. doi:10.1038/bdj.2007.892

- Pototski, M. and Amenabar, J.M. (2007) Dental management of patients receiving anticoagulation or antiplatelet treatment. Journal of Oral Science, 49, 253-238. doi:10.2334/josnusd.49.253

- Sacco, R., Sacco, M., Carpenedo, M. and Mannucci, P.M. (2007) Oral surgery in patients on oral anticoagulant therapy: A randomized comparison of different intensity targets. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology & Endodontics, 104, e18-e21. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.12.035

- Ansell, J., Hirsh, J., Hylek, E., Jacobson, A., Crowther, M., Palareti, G., et al. (2008) Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest, 133, 98S-160S.

- Hayashi, M., Okada, M., Takahashi, A., Iritani, K., Suzuki, T. and Fukuoka T. (2005) Study on risk factors for excessive prolongation of international normalized ratio of prothrombin time in patients receiving warfarin. Japanese Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Care and Science, 31, 978-985. doi:10.5649/jjphcs.31.978

- Habib, G., Nashashibi, M., Khateeb, A., Goichman, S. and Kogan, A. (2008) Excessive prolongation of prothrombin time among patients treated with warfarin and admitted to the emergency room. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 19, 129-134. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2007.08.006

- Landefeld, C.S., Rosenblatt, M.W. and Goldman, L. (1989) Bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin: Relation to the prothrombin time and important remediable lesions. American Journal of Medicine, 87, 153-159. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(89)80690-4

- Parra, D., Beckey, N.P. and Stevens, G.R. (2007) The effect of acetaminophen on the international normalized ratio in patients stabilized on warfarin therapy. Pharmacotherapy, 27, 675-683. doi:10.1592/phco.27.5.675

- Stoner, S.C., Lea, J.W., Dubisar, B.M. and Farrar, C. (2003) Possible international normalized ratio elevation associated with celecoxib and warfarin in an elderly psychiatric patient. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 728-729. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00228.x

- Kelly, M., Moran, J. and Byrne, S. (2005) Formation of rectus sheath hematoma with antibiotic use and warfarin therapy: A case report. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 3, 266-269. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2005.12.005

- Couris, R., Tataronis, G., McCloskey, W., Oertel, L., Dallal, G., Dwyer, J., et al. (2006) Dietary vitamin K variability affects International Normalized Ratio (INR) coagulation indices. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research, 76, 65-74. doi:10.1024/0300-9831.76.2.65

- Saito, R., Akao, H., Kaseno, K., Nomura, Y., Kitayama, M., Tsugawa, H., et al. (2009) Marked PT-INR prolongation associated with appetite loss due to urinary tract infection in a late elderly case with chronic atrial fibrillation. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi, 46, 541-544. doi:10.3143/geriatrics.46.541

- O’Reilly, R.A. (1967) Studies on the coumarin anticoagulant drugs: Interaction of human plasma albumin and warfarin sodium. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 46, 829-837. doi:10.1172/JCI105582

- Tincani, E., Mazzali, F. and Morini, L. (2002) Hypoalbuminemia as a risk factor for over-anticoagulation. American Journal of Medicine, 112, 247-248. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00957-3

- Abdelhafiz, A.H., Myint, M.P., Tayek, J.A. and Wheeldon, N.M. (2009) Anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and renal impairment as predictors of bleeding complications in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A secondary analysis. Clinical Therapeutics, 31, 1534-1539. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.07.015