Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.4 No.9(2014), Article

ID:49181,6

pages

DOI:10.4236/ojn.2014.49070

Investigating Veteran Status in Primary Care Assessment

Marietta Stanton

Capstone College of Nursing, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, USA

Email: mstanton@ua.edu

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 8 July 2014; revised 3 August 2014; accepted 15 August 2014

ABSTRACT

This paper emphasizes how in the process of interviewing patients, questions related to their veteran status need to be assimilated into our assessment process. Failure to determine that they are veterans may allow important issues and problems related to their health status to go undetected. Adding questions to our repertoire and knowing how to access a few key resources may assist patients in maximizing their health care options.

Keywords:Military, Veteran, Assessment, Primary care

1. Introduction

After practicing in the rural primary healthcare clinic, it has become obvious over the past semesters that there are a number of male and female veterans who seek health care through the rural healthcare clinic. A portion of these veterans may be eligible for treatment through the Veterans Administration (VA) health care but may not have access to facilities because they reside in remote rural areas. A number of these veterans do not want to pursue VA services for various personal reasons. Other veterans may not be eligible for VA care even though they served for a time in the military. Veterans not eligible for VA coverage may have health insurance through a civilian employer or Medicaid and still others may not have any health care coverage at all. About two fifths of the returning veterans receive health care and social services within the VA, and the remainder obtains care from community clinics, primary care providers, and other community services [1] . The result is that a number of veterans who have served in combat are seeking health care through the rural clinic and from other civilian agencies in the area. These veterans in many instances do not alert the primary clinic provider of their veteran status. Many civilian providers are not familiar with the unique health care issues of veterans especially the problems in mental health area. This is critical in that PTSD and mental health problems among veterans who receive care within the VA as well as among those who do not are increasing. The escalation in PTSD and stress reaction is causing suicide rates, substance abuse and chronic depression to rise among veterans. The lack of knowledge about this in civilian health care has produced a crisis in health care [2] . The rural clinic is no exception.

There is acknowledgement in the civilian, military and VA health care community that this lack of awareness imperils veterans who seek or require care outside the military and VA medical systems [3] . In fact, the American Association of Colleges of Nurses [4] has joined forces with the military and VA systems to develop a tool kit for civilian providers so that they can adequately meet the needs of veterans and mitigate health care issues for veterans of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF-Afghanistan) [4] .

Therefore, clinic procedures have to be in place in the rural primary clinic that will encourage staff to assess veteran status, integrate that information related to the patient’s veteran status into the electronic health record, and stimulate appropriate follow-up referrals as well as assess physical and mental health care problems.

The assessment of veteran status is a safety issue in which there are real health risks for veterans that if not properly included within the treatment plan may result in serious short and long term health consequences for the veterans and their families. Veterans in the rural health clinic are especially vulnerable and at risk because most rural residents do not have good access to mental health and substance abuse services [5] . Rural residents because of their culture are reluctant to seek rural mental health services because of the lack of anonymity and the perceived stigma of receiving mental health support [6] . Access to mental health services in the rural area is poor [5] -[7] . Being a rural resident puts rural veterans with mental health issues such as a Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) at double risk. Civilian providers who do treat veterans in rural or urban environments are often unaware of the unique needs of veterans in terms of health assessment and treatment as well [8] . This discussion has focused on OIF/OEF veterans but there are veterans from other wars and conflicts that do not experience symptoms until years after their service. The diagnosis of PTSD came into existence in the early 1980’s long after many Vietnam veterans had returned home [9] . Anecdotally, I was on a date in the late 70’s or early 80’s with a fellow professor and we went to see Apocalypse Now. In the middle of the movie, the gentleman stood straight up with sweat pouring off of his face and started screaming about “getting out”. I was scared beyond imagination and tried to calm and reassure him as well as removed him from the theater. He had served in Vietnam in 1968 and had never had a similar incidence prior to that night. He had a very profound flashback that night and eventually at a later time did receive mental health counseling. Therefore, providers in the civilian health care system need to inquire about veteran status from every patient whether young or old. PTSD can happen years after the tour of duty is over [9] .

There are a number of physical disease conditions besides mental health conditions that should be considered when treating veterans in the rural primary care clinic. Specifics about the physical conditions are available at www.publichealth.va.gov/diseases-conditions.asp. Rather than attempting to address all of the physical health conditions, this current paper will focus on mental health problems since this is the most dangerous and pervasive health problem for veterans in rural areas. PTSD and other mental health issues such as depression and nightmares, and sleep issues can appear individually or can co-occur and affect a large number of veterans [1] .

For this project, an examination of mental health issues of veterans will be explored in this paper. A process for insuring that this information is assessed during patient intake in the rural clinic will be identified and is included in the electronic health record for that patient will be delineated. A protocol for treatment of veterans will be outlined and a list of resources will be developed for dissemination to veterans. A plan for staff development will be designed, so that all providers as well as administrative staff are familiar with procedures and materials available for veterans.

2. Mental Health Issues for Veterans

According to the latest military statistics, there are over 21.6 veterans in the United States [2] . This includes veterans from World War II up to and including those who have served in Afghanistan and Iraq. Over 2.2 million have served in OID/OEF since 2201 [2] . Veterans who have served in combat have a variety of mental health disorders including PTSD, anxiety, depression and substance abuse [10] . In 2012, there were 349 suicides among veterans, almost one per day [11] . In 2010, there were nearly 22 per day, almost one for every hour. The largest portion of these occurred in men and women over the age of 50 [11] . Approximately, 11 percent of the suicides reported in this country occur in the veteran population [11] .

Substance abuse is another mental health problem which has been identified for veterans. Although most of the data reported concerning substance abuse comes from data collected from veterans within the VA, it provides some indication of the problem for all veterans. The VA reports that the rate of substance abuse, alcohol, drugs or both, is approximately 11 percent [2] .

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is very prevalent among OIF/OEF veterans. These injuries can be mild to severe. The Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) tracks TBI in the military. They supply a cumulative number of injuries which are updated each quarter. The cumulative total as of Quarter 2, 2013 is 280,734 and the majority of these are in the Army [12] . Although TBI is a physical injury, there are mental, emotional and behavioral sequelae which may require mental health interventions.

OIF/OEF has seen significant deployment of females [13] . They experience the same trauma as a result of service in a combat environment as their male counterparts. Additionally, it is estimated that one in five women have experienced military sexual trauma (MST) while serving in the military [2] . This provides additional mental health issues that appear unique to women yet many women are unaware of the benefits they can receive for any subsequent mental health issues from these experiences [13] . Women make up about 15 percent of the active duty workforce yet few VA facilities even offer inpatient/residential mental health programs for woman veterans [13] . The issue then is to make sure that women are asked about prior service as well as men. Further information can be obtained from www.legion.org/womenshealthcare.

Another issue that needs to be addressed with regard to mental health issues involves Reserve versus Active duty military forces. Reserve soldiers for the most part live their lives in the civilian world. They live in communities, have families, are employed in civilian jobs and are connected to the military through Reserve units. These Reserve units may be based in communities at a great distance from any Active Duty post, fort, installation or post. Reservists attend drills for the most part on a monthly basis and have extended training two or more weeks per year. The Reserves have the same branches as the Active military and may be Army, Air Force, or Navy. Reserve soldier train in specific specialties that mirror the same specialties as their Active Duty counterparts and often are called to active duty when the military needs back up forces or specific specialties found in select Reserve Units. These are considered Federal troops and during OEF/OIF were deployed and redeployed and are still redeploying. National Guard troops are also a type of “reserve force” that are under the control of the State where the Unit is located. They are often call up for extended tours of duty in response to civilian emergencies i.e. Hurricane Katrina. However, some of the “State” units are federalized and if their particular skill set is required may be activated as part of Active duty forces. Because these soldiers when activated are abruptly removed from their normal civilian life and careers, there are many adjustments when they are deployed and when they transition back to civilian life [14] . Even though these soldiers serve willingly, the change in culture and environment can make adjustment either on deployment or reintegration can produce overwhelming stress [14] . Once they are reintegrated into their home environment, they may lack the support systems and networks they had on active duty especially if they are activated individually rather than as a whole Reserve Unit. The importance of this is that often these soldiers have a higher incidence of PTSD and suicide than their Active Duty counterparts. They are more likely to seek help in their community than to travel long distances for treatment at an Active duty post. If they live in rural areas, they may not be near a VA. They are less likely to seek help for mental health issues [14] . It is also important to note that many stress reactions type symptoms like nightmares, anxiety and insomnia occur in activated Reservists just from the deployment experience even if the soldier is not sent to a combat area [14] . Therefore, even soldiers called to active duty stateside do experience stress reaction from the deployment experience and may exhibit mental health symptoms. In conclusion, reintegration stress is real and is causing another set of problems. The VA and other Federal agencies are examining ways to more effectively supporting National Guard and Reserve troops that are activated and experience reintegration stress [14] .

3. Intervention

As was previously discussed at the beginning of this paper, an interventive process to increase the safety and well-being of veterans seeking care at the rural clinic will be delineated. Much of the content for this process is based on the resources that are available at AACN website “Joint Forces: Enhancing Veterans’ Care Tool Kit” [4] . There are over 403,982 veterans in Alabama in a state with a total population of 4,779,736 [15] . Approximately one out of every 10 people in Alabama is a veteran. Less than half obtain care through the VA. That leaves a large number receiving care at non-military, non-VA facilities [2] .

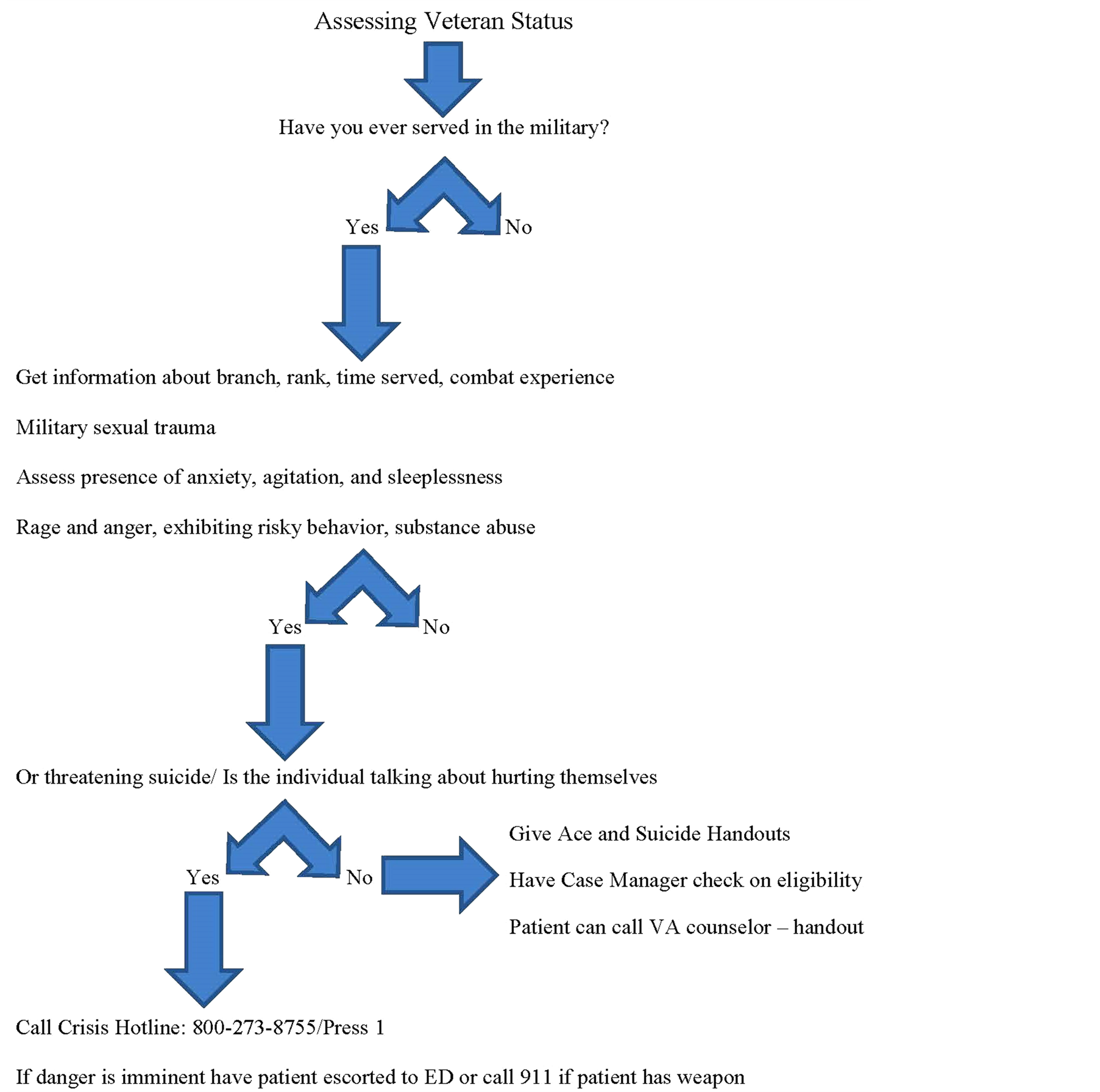

The easiest change to make to intervene on behalf of veterans is to simply hang a sign in each treatment rooms that reminds patients to let the provider know if they have prior military service. The National Association of State Directors of Veteran Affairs (NASDVA) [16] passed a resolution that a simple question should be asked by civilian health care providers “Have you ever served in the military?” NASDVA projects that this campaign will benefit approximately one million veterans [16] . The next easiest change to make to the process and procedures for the clinic will be to include a question in the social history for new and existing patients about whether or not they served in the military. This can be easily added to the assessment in the electronic health record (EHR). If the patient answers “yes” there are a series of questions from the aforementioned tool kit [4] pertaining to branch, time of service, length of service, exposure to combat among others. These six or seven questions could be added as a pop up within the EHR. There are questions concerning anxiety, sleeplessness, agitation and mood swings among other symptoms. There are several handouts one a brochure “Suicide Prevention for Veterans and Family and Friends” (2013) and an “ACE” pocket card (2013) discussing mental health issues. These can be provided to the patient and family. Additionally, if mental health issues or PTSD are evident and the patient meets the basic criteria for veteran status, the case manager can direct the veteran to the VA website to complete VA Form, 10-10EZ which is available online www.va.gov/healthbenefits/online. There also is a list of VA counselors with numbers and addresses that can be provided to the patient where they can call about other veteran benefits and programs. There are also several additional questions concerning lethality that could be asked if the provider perceives that the patient has significant mental health issues and poses a threat to themselves. These questions query whether or not the veteran has tried or thinks about hurting himself. If the danger is imminent, the AACN toolkit [4] suggests that the patient be escorted to the Emergency Room and that the provider call the VA Suicide Hotline (1-800-273-TALK, Press 1). If the patient has overdosed on drugs, has a weapon or is on the phone threatening suicide, the tool kit [4] suggests calling 911 immediately.

If a soldier has been a victim of MST whether they are male or female, they are eligible for counseling from the VA [17] . This is true even though they may not qualify for VA care using the normal criteria for eligibility. So if a veteran discusses such an assault and describes mental health related issues, there is a website they can be referred to access information and arrange for follow up care. Again the clinic case manager can provide help and support for veterans who need to access this service. The website is www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/trauma.asp.

There may be instances where patients who have served in the military are deemed ineligible for VA care and follow up. Soldiers who have been dishonorably discharged or do not meet VA criteria will not be eligible for care [17] . Soldiers discharged due to substance abuse are problematic. Patients with suspected drug abuse issues will be referred to the local community mental health clinic if they are not eligible for VA services. If they can obtain counseling though VA, they will be referred appropriately. There is a handout for providers that will help determine eligibility entitled “Mental Health”. It is available at http://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/communityproviders/index.asp. This will help providers understand how eligibility is determined.

An algorithm to assess veteran status is included in Figure 1.

4. Plan for Staff Development

The clinic is busy and so on site type classroom experiences are not well received nor well attended. Through the AACN website “Joining Forces: Enhancing Veterans’ Care Tool Kit” [4] , there is a plethora of great information for providers. Of course, the handouts discussed in this paper will be made available to patients and staff in hard copy. There is also a publication, Psychological First Aid PFA Field Operations Guide 2nd Edition [18] produced by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network and the National Center for PTSD that is available at www.aacn.nche.edu/downloads/joining-forces-tool-kit/general-resources. This booklet provides ample information about stress reactions in not only adults but children as well. This may be very valuable for family members and children living with a veteran experiencing PTSD. Additionally, there are seven mini clinics that are available online and are provider oriented. These clinics examine PTSD, serious mental illness, smoking and tobacco use, substance abuse, suicide prevention and issues for women veterans. These are available at

http://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/communityproviders/index.asp. These are free and are readily available for use. In addition the VA has posters, handouts and other materials to raise provider awareness that can be downloaded

Figure 1. Algorithm for assessing veteran status.

and posted on bulletin boards, added to newsletters, and distributed at staff meeting to raise awareness.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, an attempt to examine a safety issue involving veterans in a rural primary health care clinic was completed. Although, there are many excellent resources, there are thousands of soldiers who will return from combat and as the data predicts will be “damaged” by those experiences [19] . Not all of these veterans will line up outside the nearest VA to receive care. Many of them especially National Guard and Reservists will return to civilian life and their local healthcare systems. These healthcare systems need to be ready to provide them with timely and appropriate health care especially in the mental health arena. There is a whole gamut of physical health conditions that were not addressed for this paper due to limitations of space but pocket cards and websites exist detailing these problems for veterans from every period of service.

References

- National Center for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (2013) Conditions That Co-Occur with PTSD. United States Department of Veteran Affairs (USDVA). http://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USVHA/bulletins/66d9da

- Substance Abuse and Mental Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2012) Behavioral Health Issues among Afghanistan and Iraqi War Veterans. In Brief, 7, 1-10.http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Behavioral-Health-Issues-Among-Afghanistan-and-Iraq-U-S-War-Veterans/SMA12-4670

- Anonymous (2013) What Providers Should Know: Facts and Resources. Health Progress, 94, 10-13. http://www.chausa.org/publications/health-progress/article/may-june-2013/what-providers-should-know-facts-and-resources

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) (2013) Joining Forces: Enhancing Veterans’ Care Tool Kit. www.aacn.nche.edu/downloads/joining-forces-tool-kit/general-resources

- Winters, C.A. and Lee, H.S. (2010) Rural Nursing: Concepts, Theory and Practice. 3rd Edition, Springer Publishing, New York. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00147.x

- Golub, A., Vazan, P., Bennett, A.S. and Liberty A. (2013) Unmet Needs for Treatment of Substance Abuse Disorders and Serious Psychological Distress among Veterans: A Nationwide Analysis Using the USDUH. Military Medicine, 178, 107-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00131

- Lynch, D., Strom, J.L. and Egede, L.E. (2011) Disparities in Diabetes Self-management and Quality of Care in Rural Versus Urban Veterans. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 25, 387-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2011.08.003

- Romanoff, M.R. (2006) Assessing Military Veterans for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Guide for Primary Care Physicians, Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 18, 409-413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00147.x

- Crawford, M. (2013) Catholic Providers Reach Out to Vets. Health Progress, 94, 52-56.http://www.chausa.org/publications/health-progress/article/may-june-2013/catholic-providers-reach-out-to-vets

- Friedman, M. (2012) Older Veterans Also Have Mental Health Needs.http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-friedman-lmsw/veterans-mental-health_b_2037857.html

- Gibbons, R.D., Brown, C.H. and Hur, K. (2012) Is the Rate of Suicide among Veterans Elevated? American Journal of Public Health, 102, S17-S19. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300491

- Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) (2013) DoD Worldwide Numbers for TBI. http://www.dvbic.org/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi

- The American Legion (2013) Legion Report: Women Vets Struggle with Status. The American Legion.http://www.legion.org/veteranshealthcare/217159/legion-report-women-vets-struggle-status

- Lane, M.E., Hourani, L.L., Bray, R.M. and Williams, J. (2012) Prevalence of Perceived Stress and Mental Health Indicators among Reserve Component and Active Duty Military Personnel. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1213-1220. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300280

- United States Census Bureau (2013) State and County Quick Facts. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/01000.html

- National Association of State Directors of Veterans Affairs (NASDVA) (2013) Leading Organization to Improve Quality of Veterans’ Healthcare. http://bit.ly/AAN-NASDVA

- United States Department of Veteran Affairs (USDVA) (2012) Understanding the Military Experience. http://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/communityproviders/military.asp#sthash.ViNy4tuS.dpbs

- Brymer, M., Jacobs, A., Layne, C., Pynoos, R., Ruzek, J., Steinberg, A., Vernberg, E., Watson, P., National Child Traumatic Stress Network and National Center for PTSD (2006) Psychological First Aid: Field Operations Guide. 2nd Edition. www.nctsn.org

- Kennedy, M.S. (2012) The Hidden Wounds of War. American Journal of Nursing, 112, 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000422231.87190.3f