Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.2 No.3(2012), Article ID:23138,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2012.23028

Psychometric evaluation of a Swedish version of Krantz Health Opinion Survey*

![]()

1School of Social and Health Sciences, Halmstad University, Halmstad, Sweden

2Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University Hospital of Lund, Lund, Sweden

3Centre of Health Care Sciences Orebro University Hospital, Orebro, Sweden

4University College of Haraldsplass, Bergen, Norway

5School of Health and Caring Sciences, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden

6General Practice and Public Health, Halland County Council, Falkenberg, Sweden

7Department of Nursing, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

8School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

9The Faculty of Health and Society, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

Email: #petra.svedberg@hh.se

Received 11 June 2012; revised 8 July 2012; accepted 28 July 2012

Keywords: Heart Diseases; Consumer Health Information; Questionnaire; Reliability; Content Validity

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of a Swedish version of The Krantz Health Opinion Survey (KHOS). A convenience sample of 79 persons (47 men and 32 women) was recruited from The Heart and Lung Patients’ National Association at ten local meeting places in different areas in Sweden. The questionnaire was examined for face and content validity, internal consistency and test-retest reliability. The findings showed that the Swedish version of KHOS is acceptable in terms of face and content validity, internal consistency and test-retest reliability over time among 79 individuals >65 years of age and with a cardiac disease. In conclusion, wider evaluations of the psychometric use of KHOS for other populations and settings are recommended.

1. BACKGROUND

Patient information from the perspective of the healthcare professional is a means to help patients become active participants in their own care as well as to ensure that patients have the knowledge in order to be responseble for their own care [1]. A high level of quality of information and education for patients is one of the most important parts of the healthcare organisation [2]. Information and patient education programme for patients with chronic illnesses are well established methods for improving patients’ own knowledge and ability to care for themselves and participate in healthcare [3,4]. However, providing patients with information and advice relating to health, lifestyle, illness and its treatment is a complicated issue for healthcare professionals. Patients are to a greater extent seeking additional health information through the internet [5]. Healthcare organizations do not know to what extent patients actively seek information about their illness as well as where and when they seek advice, treatment and answers to their questions. In order to gain more knowledge in this field there is a need for methods, both assessing the patient’s requirement for information as well as evaluating the information provided. No such method was found in Sweden. There is thus a need for a questionnaire addressing these issues in a Swedish context.

Various illnesses or situation-specific instruments exist for measuring patient’s learning and/or information needs as well as questionnaires measuring patients’ behaviours in connection with information [6]. Example of situationspecific questionnaires are “Information Styles Questionaire” (ISQ) [7], Information Preference Questionnaire (IPQ) [8], Patient Learning Needs Scale (PLNS) [9], Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) [10], The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-INFO26 [11]. There are also questionnaires measuring patient behaveiours in connection with information, for example Miller Behavioral Style Scale (MBSS) [12], Health Locus of control scale (HLC) [13]. However, The Krantz Health Opinion Survey (KHOS) also called Krantz HOS [14] was created for use in a variety of settings and with different populations and related to routine aspects of health care. It was originally developed to measure preference for healthcare information, self-treatment and active involvement in healthcare. The questionnaire consists of two domains: an information subscale and a behaviour involvement subscale [14]. Validity of the two-factor original model has been provided as a less-than-adequate representation of data from a previous sample [15]. Internal consistency reliability has been reported as 0.68 to 0.77 [14,16] for the total scale, 0.55 to 0.78 for the behavioural involvement subscale [14-18] and 0.56 to 0.76 for the information subscale [14-16,19-21]. The test-retest reliability has been reported for the total scale as 0.74 [14], for the behavioural involvement subscale 0.53 to 0.71 [14,21] and 0.38 to 0.59 [14,22] for the Information subscale.

Studies with the KHOS scale have been conducted in a wide range of settings with populations such as elderly [23], myocardial infarction [24], patient-controlled analgesia [25], parents in paediatric oncology [26], renal transplantation [27] and endometriosis [28]. To our knowledge no questionnaire is available for use in general settings in Sweden, measuring how much information the patient requires and how actively they want to seek information. According to Streiner and Norman [29] a questionnaire must be re-evaluated when it is used on a different sample or when it is translated into another language because this may change the questionnaire.

Aim

The aim of this study was thus to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Swedish version of KHOS. Two main issues were focused on: 1) an investigation of the internal consistency of the Swedish version of the instrument and 2) an evaluation of the test-retest reliability of the instrument.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design and Settings

The present study had a methodological design where the translated version of the KHOS was psychometrically tested. It was carried out during spring 2007 at The National Association of Heart and Lung Patients in Sweden, which is a non-profit organization working for the goal of quality of life for people with heart and lung disease [30].

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

A convenience sample of persons was recruited from The National Association of Heart and Lung Patients at ten local meeting places in different areas in Sweden. The intension was to recruit ten respondents at each local meeting. A majority (80%) of the members in the Heart and Lung Patients’ National Association are >65 years of age [30]. The inclusion criteria were that the respondents had own experiences of cardiac disease and lived with a partner. At each meeting, a member of the nurse research team informed about the study and asked the respondents to fill in the questionnaires on two occasions with a time interval of two weeks in order to be able to investigate the test-retest reliability of the questionnaire. The questionnaires, including a return envelope, were distributed to the respondents after this information. The first questionnaire was filled in directly and was collected by the researchers and the second was mailed to the researchers.

The final sample consisted of 79 respondents (47 men and 32 women) who agreed to participate and completed the questionnaires (a response rate of 79%) on both occasion 1 and 2.

2.3. Ethics

The study was conducted according to the rules of the Helsinki Declaration on informed consent and confidentiality [31]. The respondents were informed about the purpose and the structure of the study, after which they gave their informed consent. Participation was voluntary and the respondents were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

2.4. Questionnaire

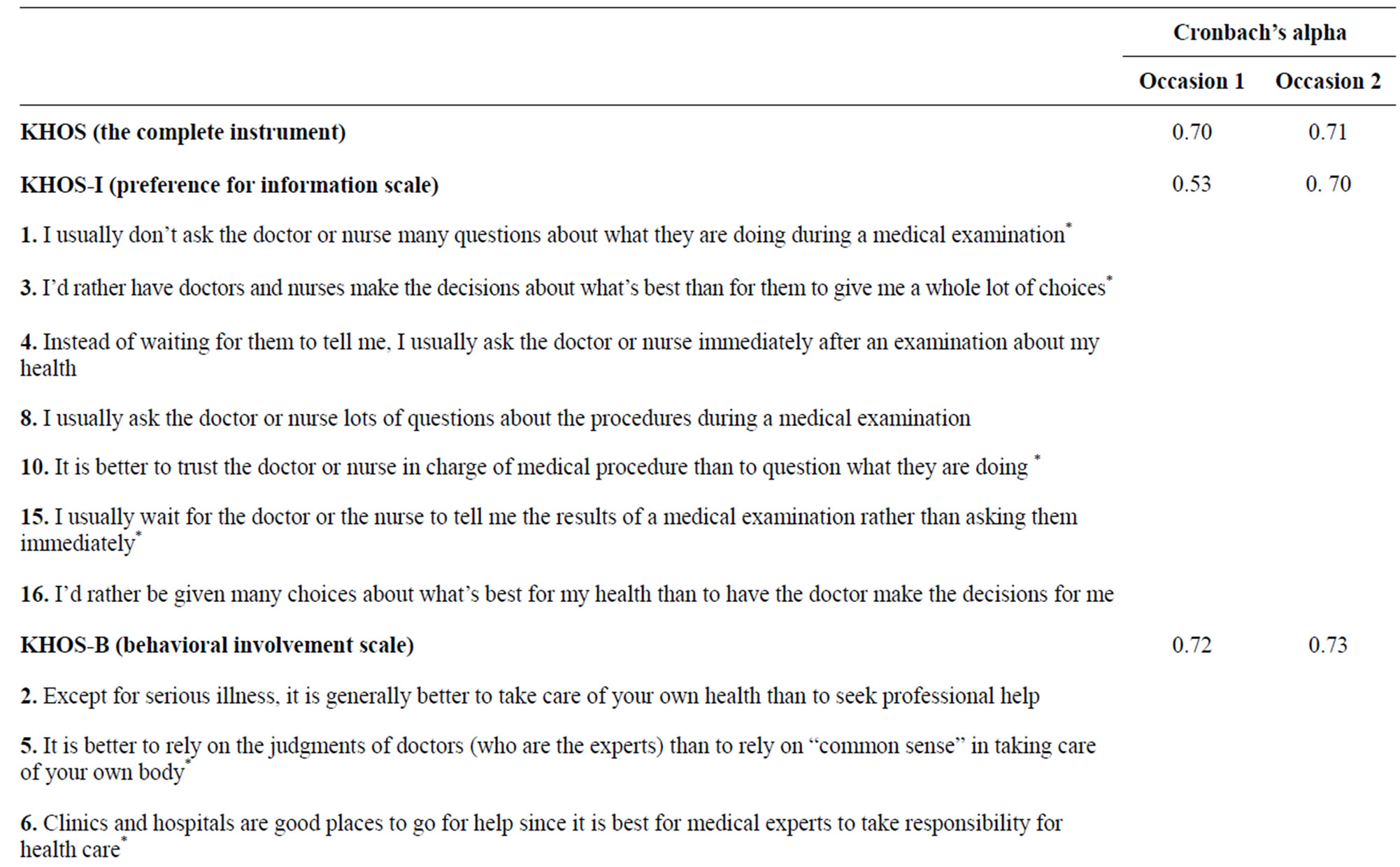

KHOS is a 16-item self-rating questionnaire (Table 1), including two subscales and used to measure patients’ desire for involvement in healthcare. The Information subscale (KHOS-I) consists of seven items and measures the desire to ask questions and be informed about medical decisions. The Behaviour Involvement subscale (KHOS-B) includes nine items relating to behaviour control preferences for involvement and self-initiated action in healthcare situations. The respondents rate their answers in a forced-choice format as agree or not agree. Higher scores indicate greater need for information seeking and preferences for control in health care situations [14].

2.5. Translation Procedure

The original version of KHOS was translated into Swedish, following a forward-backward method [32,33]. Independently of each other two bilingual healthcare professionals and researchers translated from English to Swedish and back again. First a native Swedish speaker, fluent in both English and Swedish, translated the scale to Swedish and then a native English speaker, also fluent

Table 1. Cronbach’s alpha, items and factors of the original Krantz Health Opinion Survey (KHOS).

in both languages, with no previous knowledge of the original scale, retranslated it into English in order to minimize the risk for misinterpretations between the original and the retranslated version. Differences between the original version and the retranslated version were discussed at several times by the study group in order to improve the quality of the items and the translation into Swedish.

2.6. Data Analysis

The questionnaire was examined for face and content validity, internal consistency and test-retest reliability. With regard to face and content validity the respondents who completed the questionnaire were asked to review the questions for relevance, clarity and readability as suggested by Polit and Beck [34]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to calculate the internal consistency of relevant measures and subscales in the Swedish scale and was recommended as acceptable if alpha ≥ 0.70 was attained [35]. Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) were calculated for each item in the instrument in order to investigate test-retest reliability. The first and second occasion had a time interval of two weeks [29]. The ICC produces a value of 1.0 only when the scores on the first occasion are exactly the same as those on second occasion. Guidelines used for interpretation of ICCs were based on studies demonstrating that for ordinal data ICCs are mathematically equivalent to the weighted kappa statistic [36,37]. ICC values < 0.20 were considered poor agreement, between 0.21 - 0.40 fair, 0.41 - 0.60 moderate, 0.61 - 0.80 good and between 0.81 - 1.00 very good agreement [29]. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software 17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, II, USA).

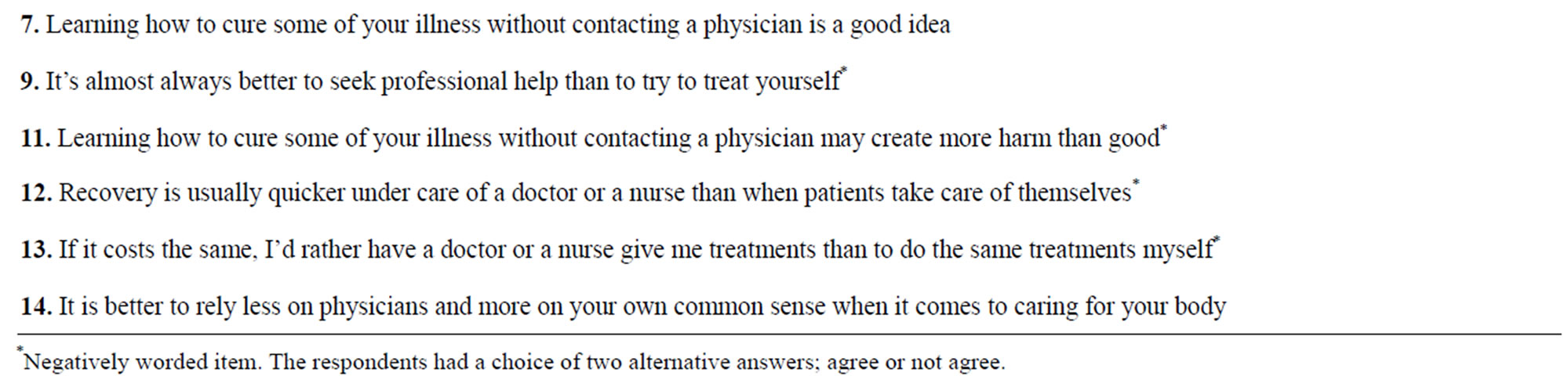

Table 2. Test-retest reliability calculated by Kappa analysis for occasion 1 and occasion 2.

3. RESULTS

The respondents understood the statements in the questionnaire and evaluated the items as being relevant for the focus of the measure as well as having sufficient clarity and readability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the original version was found to be acceptable for both the complete instrument with a range from 0.699 - 0.712, and for the subscales (KHOS-I and KHOS-B) with a ranged from 0.535 - 0.703 on the first occasion and from 0.723 - 0.731 on the second occasion (Table 1). Test-retest reliability according to ICC was ranged from 0.285 - 0.710 (Table 2). One of the items (6%) showed good agreement, nine items (56.5%) showed moderate agreement and 6 items (37.5%) showed fair agreement between the two occasions.

4. DISCUSSIN

This study focused on the psychometric properties of the Swedish version of KHOS, which measures subjective experiences of the patients’ preferences to be informed about and how they want to participate in their own healthcare. KHOS in its original form consists of 16 items divided into two subscales [14], which are frequently used in studies, both as a pair and each one on its own. In terms of internal consistency, reliability was found to be acceptable, both for the total instrument (0.70 on the first occasion and 0.71 on the second) and for the subscales (from 0.53 to 0.73). This finding was similar with earlier score of internal consistency reliability for both the total scale [14,16] and for the subscales [14-21]. This level of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient meets the criteria of 0.70 for a developing questionnaire and 0.80 for a more established questionnaire [38].

The stability of the instrument showed an ICC range between 0.285 - 0.710 and 62.5% of the items presenting moderate or good agreement for the test-retest investigation. The value was fair for six items, probably depending on culture differences or other circumstances over time. The test-retest reliability has to our knowledge only been reported for the total scale as 0.74 and for the subscales as 0.38 to 0.71 [14,21,22], but not for the separate item. Our findings are thus not directly comparable to earlier research. As we expected, ICC values higher than 0.80 for the test-retest reliability may be difficult to attain when testing an instrument that measures preference for healthcare information, self-treatment and active involvement in healthcare among persons who are members of the National Association of Heart and Lung Patients. Furthermore some of the members may not have an ongoing contact with a doctor and nurses in the health care services. The test-retest reliability findings should thus be interpreted with caution. The small sample size can also be a contributing factor for this cautionary approach.

In this study a convenience sample of persons (n = 79) was recruited from The National Association of Heart and Lung Patients at 10 local meeting places in different areas of Sweden. There might, however, be a risk with a convenience sample in that the participants who completed the instruments differed in important aspects from those who declined to participate. The response rate was high (79%) and the background characteristics of those who declined to participate are not known. The characteristics of the patients who participate in the study were limited to their having previous experience of a cardiac illness. The most important characteristic of the participants is probably the fact that the majority of the members of the National Association of Heart and Lung Patients are over 65 years old (80%) and 59 % are women and 41 % are men [30]. The high response rate may have been influenced by the members from The National Association of Heart and Lung Patients probably feeling a strong commitment to the association and supporting each other; sharing knowledge and exercising together in order to increase well-being [39]. This could lead them to being highly motivated to participate in studies to increase knowledge in the field as well as actively seeking information. The most conservative estimate would be that the findings of the present study may only be representative for those participating in it. The questionnaire should therefore be further tested on a larger sample of individuals with different socio-demographic and clinical backgrounds in order to test its validity and reliability as well as to determine whether it can be used as a generic instrument in health services.

Finally, regarding the clinical feasibility, the trend towards short in-hospital care, the heavy workload in the nursing profession [40] as well as the easy access to the Internet, healthcare professionals need to have useful and appropriate instruments to meet the information needs of all patients and their next-of-kin. One important issue is that, when Krantz et al. [14] in 1980 developed the KHOS with the purpose of providing information and encouraging active involvement or self-care, information technology as we know it today was not available. Dramatic changes have taken place and people now have easy access to the Internet and there is an opportunity for the healthcare organisation for electronic delivery of diagnosis, management, education and support to both patients and next-of-kin [41]. Leino-Kilpi et al. [16] found out that persons who are active in searching information tend to receive less knowledge than more passive patients. They draw the conclusion that the findings may be attributed to the fact that information-giving to patients who are more active in seeking health information should be tailored since they already have some knowledge and thus may not perceive the current information being given to them as something new. Anker et al. [42] stated in a review that healthcare professionals should be encouraged to find out whether their patients searched for information and what channels they used and then evaluate how patients used the information. Therefore, a questionnaire such as KHOS could be a useful tool for healthcare professionals in clinical practice in order to provide essential indications about patients’ information needs. In addition, there is a need for further research of the Swedish version of KHOS.

5. CONCLUSION

The results from the present study show that the Swedish version of KHOS is acceptable in terms of face and content validity, internal consistency and test-retest reliability over time for individuals >65 years of age and with a cardiac disease. The questionnaire should be further tested on a larger sample of individuals with different socio-demographic and clinical backgrounds in order to test its validity and reliability as well as to determine whether it can be used as a generic instrument in health services. It would also be valuable to further investigate whether there are associations between information and associated phenomena, such as empowerment, social support and patient satisfaction with care. There is also a strong necessity for additional research of the use of the questionnaire in a Swedish clinical context.

6. IMPLICATIONS

High quality of information and education to patients is one of the most important parts of the healthcare organisation. The use of this questionnaire could be a helpful tool for the healthcare professionals in relation to the patient in order to evaluate the level and needs of information.

REFERENCES

- Leino-Kilpi, H., Iire, L., Suominen, T., Vuorenheimo, J. and Välimäki, M. (1993) Client and information: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2, 331-340. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.1993.tb00190.x

- Sheard, C. and Garrud, P. (2006) Evaluation of generic patient information: Effects on health outcomes, knowledge and satisfaction. Patient Education and Counseling, 61, 43-47. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.004

- Coster, S. and Norman, I. (2009) Cochrane reviews of educational and self-management interventions to guide nursing practice: A review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46, 508-528. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.09.009

- Newman, S., Steed, L. and Mulligan, K. (2004) Selfmanagement interventions for chronic illness. Lancet, 364, 1523-1537. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17277-2

- Rahmqvist, M. and Bara, A.-C. (2007) Patients retrieving additional information via the Internet: A trend analysis in a Swedish population, 2000-05. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 35, 533-539. doi:10.1080/14034940701280750

- Frank-Stromborg, M. (2004) Instruments for clinical health-care research. 3rd Edition, Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury.

- Cassileth, B.R., Zupkis, R.V., Sutton-Smith, K. and March, V. (1980) Information and participation preferences among cancer patients. Annual of Internal Medicine, 92, 832-836.

- Hopkins, M.B.R.N. (1986) Information-seeking and adaptational outcomes in women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. Cancer Nursing, 9, 256-262. doi:10.1097/00002820-198610000-00006

- Bubela, N., Galloway, S., McCay, E., McKibbon, A., Nagle, L., Pringle, D., Ross, E. and Shamian, J. (1990) The patient learning needs scale: Reliability and validity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 15, 1181-1187. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1990.tb01711.x

- Moerman, N., Van Dam, F.S., Muller, M.J. and Oosting, H. (1996) The Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS). Anesthia & Analgesia, 82, 445-451.

- Arraras, J.I., Kuljanic-Vlasic, K., Bjordal, K., Yun, Y.H., Efficace, F., Holzner, B., Mills, J., Greimel, E., Krauss, O. and Velikova, G. (2007) EORTC QLQ-INFO26: A questionnaire to assess information given to cancer patients a preliminary analysis in eight countries. Psycho-Oncology, 16, 249-254. doi:10.1002/pon.1047

- Miller, S.M. (1987) Monitoring and blunting: Validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 345-353. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.2.345

- Wallston, B.S., Wallston, K.A., Kaplan, G.D. and Maides, S.A. (1976) Development and validation of the Health Locus of Control (HLC) scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 44, 580-585. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.44.4.580

- Krantz, D.S., Baum, A. and Wideman, M.V. (1980) Assessment of Preferences for self-treatment and information in health care. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 977-990. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.977

- Robinson-Whelen, S. and Storandt, M. (1992) Factorial structure of two health belief measures among older adults. Psychology and Aging, 7, 209-213. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.7.2.209

- Leino-Kilpi, H., Heikkinen, K., Hiltunen, A., Johansson, K., Kaljonen, A., Virtanen, H. and Salanterä, S. (2009) Preference for information and behavioural control among adult ambulatory surgical patients. Applied Nursing Research, 22, 101-106. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2007.05.003

- Strauss, S.S. (1988) Information preferences and information-seeking in hospitalized surgery patients. In: Waltz, C.F. and Strickland, O., Eds., Measurement of Nursing Outcomes, Springer, New York, 61-79.

- Välimäki, M., Leino-Kilpi, H., Grönroos, M., Dassen, T., Gasull, M., Lemonidou, C., Scott, P.A. and Benedicta, M. (2004) Self-determination in surgical patients in five European countries. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36, 305-311. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04056.x

- Caldwell, L.M. (1991) The influence of preference for information on preoperative stress and coping in surgical outpatients. Applied Nursing Research, 4, 177-183. doi:10.1016/S0897-1897(05)80093-X

- Garvin, B.J. and Kim, C.-J. (2000) Measurement of preference for information in U.S. and Korean cardiac catheterization patients. Research in Nursing & Health, 23, 310-318. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<310::AID-NUR7>3.0.CO;2-#

- Strauss, S.S. and Sawin, K.J. (1990). The Krantz Health Opinion Survey: A measurement model. In: Strickland, O. and Waltz, C.F., Eds., Measurement of Nursing Outcomes, Springer, New York, 229-249.

- Christensen, A.J., Smith, T.W., Turner, C.W. and Cundick, K.E. (1994) Patient adherence and adjustment in renal dialysis: A person × treatment interactive approach. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 17, 549-566. doi:10.1007/BF01857597

- Campbell, R.J. and Nolfi, D.A. (2005) Teaching elderly adults to use the Internet to access health care information: Before-after study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 7, e19. doi:10.2196/jmir.7.2.e19

- Garvin, B.J., Moser, D.K., Riegel, B., McKinley, S., Doering, L. and An, K. (2003) Effects of gender and preference for information and control on anxiety early after myocardial infarction. Nursing Research, 52, 386-392. doi:10.1097/00006199-200311000-00006

- Gagliese, L., Jackson, M., Ritvo, P., Wowk, A. and Katz, J. (2000) Age is not an impediment to effective use of patient-controlled analgesia by surgical patients. Anesthesiology, 93, 601-610. doi:10.1097/00000542-200009000-00007

- Gagnon, E.M. and Recklitis, C.J. (2003) Parents’ decision-making preferences in pediatric oncology: The relationship to health care involvement and complementary therapy use. Psychooncology, 12, 442-452. doi:10.1002/pon.655

- Christensen, A.J., Ehlers, S.L., Raichle, K.A., Bertolatus, J.A. and Lawton, W.J. (2000) Predicting change in depression following renal transplantation: Effect of patient coping preferences. Health Psychology, 19, 348-353. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.19.4.348

- Lemaire, G.S. (2004) More than just menstrual cramps: Symptoms and uncertainty among women with endometriosis. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 33, 71-79. doi:10.1177/0884217503261085

- Streiner, D.L. and Norman, G.R. (2003) Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. 3rd Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Swedish Heart and Lung Association (2007). http://www.hjart-lung.se

- World Medical Association (2008) Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical principles for medical research involving Human subjects. The World Medical Association (WMA), Seoul.

- Brislin, R.W. (1970) Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 185- 216. doi:10.1177/135910457000100301

- Cha, E.S., Kim, K.H. and Erlen, J.A. (2007) Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: Issues and techniques. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58, 386-395. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04242.x

- Polit, D.F. and Beck, C.T. (2008) Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 8th Edition, Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

- Burns, N. and Grove, S. (2001) The practice of nursing research: Conduct, critique & utilization. 4th Edition, Saunders, Philadelphia.

- Fleiss, L. and Cohen, J. (1973) The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 33, 613-619. doi:10.1177/001316447303300309

- Landis, J.R. and Koch, G.G. (1977) Measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159-174. doi:10.2307/2529310

- Rattray, J. and Jones, M.C. (2007) Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16, 234-243. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01573.x

- Hildingh, C. and Fridlund, B. (2004) A 3-year follow-up of participation in peer support groups after a cardiac event. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 3, 315-320. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2004.05.003

- Aiken, L.H., Clarke, S.P., Sloane, D.M., Sochalski, J.A., Busse, R., Clarke, H., Giovannetti, P., Hunt, J., Rafferty, A.M. and Shamian, J. (2001) Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs, 20, 43-53. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43

- Endacott, R., Boulos, M.N.K., Manning, B.R. and Maramba, I. (2009) Geographic information systems for healthcare organizations: A primer for nursing professions. Computer, Informatics and Nursing, 27, 50-56. doi:10.1097/NCN.0b013e31818e4660

- Anker, A.E., Reinhart, A.M. and Feeley, T.H. (2011) Health information seeking: A review of measures and methods. Patient Education and Counseling, 82, 346-354. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.008

NOTES

*Thanks for the SAMMI-study group’s contribution to this paper.

*Conflict of Interest: None declared.

#Corresponding author.