Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2015, 3, 39-47 Published Online September 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2015.39007 How to cite this paper: Della Volpe, V. (2015) ICT and Inclusion in Higher Education: A Comparative Approach. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 3, 39-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2015.39007 ICT and Inclusion in Higher Education: A Comparative Approach Valentina Della Volpe Department of Human and Social Sciences, Educational Research, Foro Italico University, Rome, Italy Email: valentina.dellavolpe@uniroma4.it Received 1 June 2015; accepted 13 September 2015; published 18 September 2015 Abstract The following research describes an attempt to combine ICT and Special Education through an in- clusive pedagogical perspective. It examines how an innovative use of Information and Communi- cation Technology can help create inclusive environments on the web. Specifically, the study fo- cuses on the way the University responds to diversity and to e-inclusion through some develop- ment phases of an experimental research project, which is most far-reaching called “Net- work@ccessible: teaching/learning together and for everyone in a life project” carried out by six Italian universities and research institutions, from 2009 to 2014, and involved 1174 students (1.6% disabled students). This study is split into two main parts: 1) description and analysis of the data collected following the administration of an inquiry tool, developed to detect the climate expe- rienced by the students involved in the online working groups; 2) investigation and detection of the elements of change that can encourage the process of inclusion in online learning environ- ments to acquire credits allocated to the university courses. This study proposes further research to take place in the area of inclusive online university courses. Keywords Inclusion, Information and Communication Technology, Online Tutoring, Disability 1. Introduction The Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) can offer good chances to spread and create inclusion processes: putting together different people and different subjects moving from an informal to a formal dimen- sion and vice-versa during the learning process can enhance and develop a common background dimension to encounter the different educational needs of people [1]. In an inclusive context we can offer more learning opportunities by favoring the development of knowledge and enhancing the process of creating the competences in regards to the potentialities of everyone. This paper examines the roles of both multimedia and special education applied to distance university courses. The concept of an inclusive approach of multimedia here focuses not only on the ways in which the needs of all students, including those with disabilities, in accessing, attending and achieving potentials on the program are met, but also on the ways the University responds to diversity under the following elements: quality of educa-  V. Della Volpe tional path, method and organization of educational environment, tutors’ professional skills, integrated strategies and methodologies [2]. The research aims at creating the conditions to develop inclusive contexts on the Internet, by connecting learning and pedagogical aspects in the learning process together with the Internet technologies [3]-[5]. A spe- cific focus is kept on the structural and cultural accessibility, based on the new concept of accessibility, as estab- lished by the Convention on Rights of People with Disabilities from the United Nations in 2006, validated in It- aly in 2009, and reiterated in the more recent programs of the European Union [6]. We discuss the elements of change, both pedagogical and technological, that are introduced in the training in order to define an environment for virtual inclusive education. 2. Description of the Study 2.1. Delimitations of the Study The FIRB research project Network@ccessible is a scientific experiment that has identified both the short-term and the long-term effects of an inclusive online education program for students with and without disability of master degree courses. From 2009 through 2014, six Italian Universities and research institutions, coordinated by Lucia de Anna from the University of Rome “Foro Italico” operated the Network@ccessible program for university students, including those with disabilities, in order to help them know and think about inclusion, but mainly to be able to understand and to deal with different situations. This allows them to become participant citizens by dealing with the responsibilities coming from the principles of the above mentioned UN Convention on rights of disabled people and related problems. If all of us fully understand the meaning of participation, i.e. helping other people’s participation, it means that we are able to listen to others and that we are creating an environment for the others, in which we can oper- ate together [7]. Such environment can be the Internet, platforms, discussion forums, the creation of knowledge, the exchange of experiences, the diffusion of knowledge of ourselves, our issues, but also our desires and chal- lenge s. 2.2. Research Problems The current research is aimed at finding out the answers of the following questions: 1) Tutorship Dimension. The tutor, which is expert in the inclusion processes and has the competences to de- velop independent learning skills in every student within the online environment by integrating pedagogical and technological competences, is he/she able to manage complexity in an online learning environment? 2) Educational Purposes Dimension. Can an online learning environment, developed to include miscellaneous university students and for the inclusion of those with disabilities, favour the cooperative creation of know- ledge through a sort of social negotiation and the awareness of the different learning paces of everyone? What is the best way to organise an online learning environment to offer permanent and accessible features for everybody? 3) Planning Approach Dimension. How does a university student, in this specific case belonging to the “Foro Italico” University, evaluate the importance of an online educational path in terms of expectations, impact and results on the topic of inclusion? What is the role of the student in the teaching/learning process? What is the level of satisfaction about the own educational path in regards to knowledge, competences, achieved goals and innovation of the proposed didactics and methodologies used? 4) Interaction Dimension. Given a specific learning environment, in which the creation of the topics are nego- tiated between teachers and students, is it possible to detect issues, intuitions, needs and hypotheses that in the traditional didactics would get lost and the common potentials with the creation of online forums? 2.3. Research Population and Sample We identified a sample of 1174 students (1.6% of which were disabled students). 900 of them were students in Psychology and Pedagogy (coming from different universities, namely Roma Tre University, Bologna and Naples University), while the remainder 274 were students of Human Sciences, Sport and Movement Depart- ment which were also qualifying in Special Education. 694 students were randomly assigned to a program group  V. Della Volpe PG that received a high-quality inclusive training on the Network@ccessible platform while 480 were instead assigned to another group that received no high-quality training NPG. Because of the random assignment strat- egy, the students’ web training experience remains the only explanation for subsequent group differences in their performance over the project phases. We collected data on a monthly basis, from both groups during the months September through January and again at February and May, with a missing data rate of only 10% across all measures. After each period of data collection, staff analyzed the information and developed a comprehensive official report. 2.4. Research Tool As mentioned in the abstract, this work presents the description and the analysis of the data collected following the administration of a questionnaire, developed to detect the climate experienced by the students involved in the online working groups. The questionnaire gathered the opinions of students about the experience they lived in inclusive cooperative activities in view of four dimensions (Tutorship, Educational Purposes, Planning Ap- proach and Interaction). The tool evaluates the quality and efficacy of the education-training experience realized and of the e-tutors formative action in the construction and facilitation of inclusive processes. The questionnaire was developed based on the literature review, i.e. analysis and review of the literature on the specific research topic. We have then applied the Delphi method and we have created an expert panel (group of experts) to reach the final stage. More precisely we have used a specific technique of the method, systematic and interactive, face to face meetings, so we can in fact talk about Mini-Delphi or Estimate-talk-Estimate (ETE). The test has been validated through the measurement of the reliability of the internal coherence between areas and items and their significance (the consistency of the framework has a value of 0.970 Cronbach’s alpha. Such value is close to excellence). We analyzed the inter-relation between the four dimensions that form the tool by calculating the stability in- dex represented by the Pearson’s coefficient (all correlations in our analysis are substantial and positive). The questionnaire used in the trial consists of 40 questions: the first three (A, B, C) are open questions with free answers, the others are structured questions, each of them providing predetermined responses articulated according to a Likert scale with four levels (Very, Enough, Little, Not at all). It was decided to administer the questionnaire only at the end of the training process. Table 1 indic ates the four dimensions and the subdivision of the items for each of them. 3. Data Analysis The number of questionnaires returned and analyzed was 694 from the PG, and 420 from NPG. The coding and decoding of the responses was conducted in SPSS, with retrospective codification using ma- cro-categories for answers to open questions and with conventional procedures for quantitative answers to closed questions. The questionnaires were submitted to bivariate analysis, to observe, synchronously, the actual outcome of the experience compared to specific issues; to multivariate analysis to represent the data position related to selected items on a Cartesian axis, according to a specific perspective. In general the results obtained have been very positive and there were not large gaps between input and output opinions or between the expectations towards cooperative learning and the realization of activities in the group, except for some cases that will be highlighted below. Table 1. Inquiry dimension. Number Dimension Number of items Dimension (one) Tutorship 12 Dimension (two) Educational purposes 12 Dimension (three) Planning approach 8 Dimension (four) Interaction 8 Total 40  V. Della Volpe In particular, regarding questions A and B, students considered that cooperative activities have allowed the construction of relations of positive interdependence, improved the relationship with the e-tutors and have given a favorable disposition towards the acquisition of topics concerning inclusion culture. They also expressed the opinion that it would be interesting to have work-group activities also in other courses, as research was useful and interesting and that in depth analysis has enhanced their learning experience because the team-work “forced” them to reflect on their own comprehension and cooperation processes. It is interesting to observe that within experimental groups, as far as the option “My experience during the course gave me a new perspective on soft skills (teamwork, problem solving, ability to handle problem situa- tion…)” in question B is concerned, the out-going data has increased by +3.4% (+3.6% for students with dis- abilities), and in the context of control group, the alternative “The team-work will force/help you to reflect on your learning process” has achieved an increase of +2.4% (the same for students with disabilities), and also the alternative “the learning style and the learning pace of each student were respected” has increased by +4.1% (+7.3% for students with disabilities). This shows that the students of experimental group found a strong help relationship, as a scaffolding in order to facilitate the learning process, and support in team-work and hope to find the same in other courses; on the other hand, the students have especially perceived the metacognitive di- mension in cooperative work. 3.1. Tutorship The results of the multivariate analysis confirms the information taken from both the univariate and bivariate analyses, which provided a very positive feedback, especially about the importance of the e-tutor role in manag- ing the relationship between the members of the group, both in the relational field and on the taking charge of common responsibility in the working activity. As previously stated, the presence of an e-tutor which is expert on special education in the course of experimental group has helped students to create a situation of online co- operation more relaxed and effective between all students, including those with disabilities. In particular, for students that received a high-quality inclusive training on the Network@ccessible platform, the work group experience was satisfactory, especially for the role of the tutor as a valuable support in over- coming difficulties. Table 2 summarizes the skills that students attribute to the e-tuto rs . This raises the issue that e-tutors of an online inclusive community have to develop, more than methodologi- cal proficiency and accuracy to transmit an inclusive culture, or strong disciplinary, technology, communicative skills to deal with an emerging cyber-culture. To paraphrase Depover [8] and Moliterni [9], developing inclusive pedagogical competences would mean developing an attitude of openness and flexibility, acquiring knowledge of societal and individual interaction, and developing skills to critically interpret new cultural knowledge and every learning style. In short as a tutor, mediator and facilitator of a learning methodology that makes students progressively autonomous in their own cognitive processes. The e-tutor, operating in an inclusive virtual environment, has to have deep understanding of the integration processes. The e-tutor has to be able to create and activate formative processes based on specific needs of any single student, in order to have the students succeed, by making the learning experience effective and successful. The e-tutor might also help students follow the most suitable paths necessary to reach their personal goals. Table 2. Student view of e-tutor roles. Soft Skills Pedagogical and technology skills • Develop receptivity, collective harmony, apprenticeship, deductive learning • Encourage motivation and keep the interest alive • Encourage and develop cooperation and participation of all, creativity, inductive learning • Be a facilitator, organiser • Be a model of how to find out • Be a friendly critic • Encourage to find own answers • Develop critical thinking • Promote meta-cognitive learning • Be an authority, expert • Be a model: knowing that, how to • Promote and support advancement of knowledge on the issues of inclusion • Give answers, clear guidance: teach us what to do • Learn methods, technical advances • Focus on process of learning, research skills • Attention to the specificity of each student • Know students’ problems and specificity stile learning • Promote and support advancement in technology and the web  V. Della Volpe 3.2. Educational Purp ose In Table 3, we can notice the percentage reported in discriminating items for this investigated dimension. We have compared the values expressed by the experimental group, non-disabled students and disabled students. The most important fact that emerges is that students who participated in the project seem to have taken a great active role in the inclusive online environment for the implementation of their own educational path. In more detail, 71.6% of them seem to consider that the online learning environment has favored the coopera- tive creation of knowledge through a sort of social negotiation and 66.3% the awareness of the different learning paces of everyone. Online work sessions have proposed didactic strategies on how to learn through acting, in which students were the main actors of the learning process in regards to self-cognition, responsibility and reflection, with an active role in the creation of their own knowledge and acquisition of competences. In fact, the main goal of the inclusion is to get students to actively participate within the class [10], and everyone has to have the same for- mative resources. Hence, the analysis of the data in such research area shows that one of the educative goals of the path focused on the development and consolidation of cross competences. It is necessary to get to a proposing pedagogy that supports the conversational and dialogic value of the learning paths, in which everyone’s issues are gathered and re-elaborated through an effective interactive com- munication, activating a positive inter-dependence that can incentivize a socialized external learning as well as meta -cognitive skills that allow the development of personal and social skills of the students [11]. 3.3. Planning Approach A multiple correspondence analysis among items requiring considerations about management of the work has been carried out. Answers to questions 38, 39, and 40 have been cross-checked; those questions required stu- dents to indicate the course's focus (knowledge, used tools and technologies, methods and practices of inclusive education) in order to better understand the background of the course. Results of the analysis are shown in Fig- ure 1. The outcome was that the higher percentage of students felt that each skill, listed in 40, could have been ac- quired and developed through experiences similar to the one done. The most part of the students of groups (51%) that received a high-quality inclusive training on the Network@ccessible platform, responded that they prefer methods and practices of inclusive education study to optimize the working times, to exchange ideas and opi- nions, to become aware of the contents that are mastered and of those to delve deeper into. In particular, for sample students, the experience about inclusive topic and practices was satisfactory, especially for the manage- ment of the work in an informal way, the content sharing and the reflection about it, both in meta-cognitive and in social relation dimension. There are no significant statistical differences between the students in the experi- mental group (51%) and students with disabilities (52%). At the same it is also very important to acquire good learning content (29.3% Program group, 26% Disabled students), and technological skills (29% Program group, 19.7% disabled students). On the other hand, 47% of the students from the control group discovered that team work was more focused Table 3. Stances and opinions about online environment. Statement I Agree (Strongly Agree/Agree) Program group Percentage % Students with disabilities Percentage % The on-line course was a fast and efficient way to acquire and improve my knowledge and my skills 70 69 The working sessions have always supported my motivation and my interest 85 87 The training was innovative 90 90 The course was a creative way to acquire new soft skills (teamwork, problem solving, ability to handle problematic situations) 96 97 In the course I have actively participated in the creation/sharing of knowledge 7 1,6 74 The course was an opportunity to try out new learning and teaching methods 93 95  V. Della Volpe on learning contents. In F igure 2, we can notice that students who participated in the project seem to have acquired more skills and knowledge when compared to the no-program group. In more detail, 40% of them has familiarized with inclusion Figure 1. Network@cces sibl e platform background. Figure 2. Skills and knowledge acquired.  V. Della Volpe topics, while 92% of them claim that students with disabilities should have the same educational opportunities also in online courses and has thought of using the acquired skills in other educational settings. 84% of them claim that they have gathered new knowledge and new skills through dynamic, interdisciplinary, informal activ- ities. All program group students claim that they care about the inclusive education more than they used to, and all program group students claim that ICT can advance the inclusion processes. On the other hand, only 40% of the students from no-program group has familiarized with inclusion topics, only 40% of them has thought of us- ing the acquired skills in other educational settings, and they have not used new learning methods. However 70% of them claim that ICT can favor the inclusion processes. While analyzing the data, we have found out that online learning is based on an environment that is free from the strict rules of an objective approach, but it enhances the exchange of knowledge and information, promote study and investigation within authentic contexts; encourages the growth of student responsibility, initiative, de- cision making and intentional learning; cultivates collaboration among students and students and teachers; uti- lizes dynamic, interdisciplinary, generative learning activities (methods and practices of inclusive education) that promote higher order thinking processes to help students develop rich and complex knowledge structures. Finally it helps assess student progress in content and learning to learn within authentic contexts using realistic tasks and performances. Inclusive online learning environment engages students in a continuous collaborative process of building and reshaping understanding as a natural consequence of their experiences and interactions within learning environ- ments that authentically reflect the world around them. The attention moved from the product to the process, in which the strategy is measured with the variety of situations and problem, and such change impacts the planning that has to be flexible and complementary [12]. We can try to define the inclusive online learning environment as: • A formative scenario with an integrating background; • A context intentionally fitted for non-structured activities; • An informal active environment. Planning the inclusion means investigating and learning through acting and experiencing [13]; hence the na- ture of the project develops while it’s being carried out, and the elements of self-analysis impacts the planning hypothesis within an itinerary of development of goals, formative contents and competences. 3.4. Interaction Figure 3 indicates that the most part of students of program group (87%) that received a high-quality inclusive training on the Network@ccessible platform have gathered new knowledge by sharing their point of view with others and by collaborative writing, 90% of them claim that multimedia tools (forums, chat, wiki, etc.) encour- age and simplify communication and group work; 88% of them agree that the covered topics in the forum have offered many points for reflection on the issues and 75% of them claim that subjects and platform’s areas were very accessible and usable. The theory of active involvement, applied to online learning environments shows that students learn effec- tively through the interaction with others. The individual shares the same point of view and acts alike the group he/she belongs to, thanks to stimulating working tasks [14]-[16]. Data analysis and this statement suggests that between the components of an online learning environment, the electronic tools for communication, such as discussion forums, offer multiple points of view that help develop cognitive flexibility and represent a space of shared knowledge, enhancing its dialog power. To create an inclusive didactic environment through multimedia tools, it is important to know and let every- body know how to interact in a virtual classroom, in consideration of all other aspects such as learning, cogni- tive styles, intelligence quality, self-efficiency and motivation [17]. An online forum hence represents an environment where the individuals involved can observe themselves and the others, confronting with the others and with their points of view [18] [19]. Everyone can share his/her point of view and express it openly. In this way the forum can be a valid educational and formative tool, not only on an informational level, but in particular to create interrelationships with others, thanks to the usability. 4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives The experimentation of activities carried out in the university inclusive and cooperative learning online in 5  V. Della Volpe Figure 3. Information and feature about online learning environment. years was overall very positive. All students, including disabled ones (the National Statistics told us that stu- dents with disabilities were 1.6% of the university population, the percentage was the same in our experimental course s), felt themselves involved in the learning process and in the construction of the course through the topics developed in work group in the Network@ccessible platform. Students have discovered that the online work group helps to develop cognitive, meta-cognitive, and social skills. Also, they argue that the ICT can advance the inclusion processes and that similar experiences are desira- ble in their academic path. Moreover, the operations of analysis, synthesis, evaluation and correction of the online path followed, the use and testing of methods and practices of inclusive education, have helped to strengthen their self-esteem, a sense of belonging to a learning community where every student should have the same educational opportunities and a positive disposition towards dialogue and openness to the others. It was also observed, in the comparison between the two program and no-program group, that the presence of an e-tutor, who acted as a systematic and continuous support, helped to create a climate of greater cooperation related to the undertaking of individual responsibility in the performance of assigned tasks, and helped to de- velop the advancement of knowledge on the issues of inclusion through attention to the specificity of each stu- dent. The findings also suggest that an interdisciplinary and an informal approach, as well as accessible and usable multimedia tools, are crucial to ensure the active participation of all students. This study proposes further research to take place in the area of inclusive on-line university courses. In the future it would be desirable to incorporate the activities of online inclusive cooperative learning in other course s, to train students on diversity and cooperation, active listening, strategies for inclusive education, shar- ing of knowledge and skills, as well as to offer them an area of aggregation and dialogue using an e-learning platfor m. References [1] de Anna, L. and Della Volpe, V. (2014) The Research Project Firb Network@ccessibile. “Technological and Higher Education in the World”. Bulletin of National Institute of Educational Resources and Research, 64, 95-120 . http://www.naer.edu.tw/ezfiles/0/1000/attach/81/pta_7247_1329391_15783.pdf  V. Della Volpe [2] Della Volpe, V. (2012) Inclusive Online Learning Environments: Pedagogical Reflections and Possible Applicable Models. PhD Thesis, Foro Italico University, Rome. [3] de Anna, L. and Della Volpe, V. (2011) FIRB Network@ccessibile Project: An International Dimension for an Inclu- sive E-Learning. Educational and Social Inclusion, 10, 254-266. [4] de Anna, L. and Della Volpe, V. (2012) FIRB Network@ccessibile Project: Ternational Perspective between Italy and Brazil. In: Steren dos Santos, B. and de Anna, L., Eds., Annals of III SIPASE—Psychopedagogic Areas in Different Scenarios, 160-174. http://www.pucrs.br/orgaos/edipucrs/ [5] de Anna, L., Canevaro, A., Ghislandi, P., Striano, M., Maragliano, R. and Andrich, R. (2014) Net@ccessibility: A Re- search and Training Project Regarding the Transition from Formal to Informal Learning for University Students Who Are Developing Lifelong Plans. ALTER, European Journal of Disability Research, 8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2014.02.002 [6] European Commission (2010) European Disability Strategy 2010-2020: A Renewed Commitment to a Barrier-Free Europe. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0636:FIN:EN:PDF [7] Can evaro, A. (2008) Outcropping Stones. E ri ckso n, Tre n to . [8] Depover, C., De Lievre, B., Peraya, D., Quintin, J.J. and Jaillet, A. (2011) Tutoring in Distance Education. de Boeck, Bruxell es. [9] Moliterni, P. (2014) Studying at University: Strategies for Learning and Training Contexts. Franco Angeli, Milano. [10] Ianes, D. (2005) Special Education for Inclusion. Erickson, Trent o . [11] Andrich Miato, S. and Miato, L. (2003) The Inclusive Education. Organizing Cooperative and Metacognitive Learning. Eric kson , Tre n t o . [12] Rossi, P.G. (2009) Technology and Construction of Worlds: Post-Constructivism, Language and Learning Environ- ments. Armando, R oma . [13] de Anna, L. (2013) E-Inclusion and University Teaching. Inclusive Learning Environments’s Design. Fridericiana Edi- trice Universitaria, Napoli. [14] Khan, H.B. (2003) E-Learning: Planning and Management. Erickson, Tren t o . [15] Trentin, G. (2004) Online Learning and Knowledge Sharing: Role, Dynamics and Technologies of Online Professional Communities. Franco An ge l i , M i lan o . [16] Song, L. and Xiong, H. (2011) Advances in Computer Science, Environment, Ecoinformatics and Education. Spring-Verlang, Berlin. [17] De Beni, R., Meneghetti, C. and Pezzullo, L. (2010) Metacognitive Approach and Universitary Distance Education. Tecnologie Didattiche, 1, 21-28. [18] Calvani, A., Fini, A. and Molino, M. (2010) Assess Online Collaborative Groups within Institutional Contexts: A Mul- tidimensional Approach. Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society, 6, 99-108. [19] Spiro, R.J., Collins, B.P. and Ramchandran A.R. (2006) Modes of Openness and Flexibility in “Cognitive Flexibility Hypertext” Learning Environments. In: Khan, B., Ed., Flexible Learning. Englewood Cliffs, Educational Technology Publications, N.J. http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59904-32 5-8.ch002

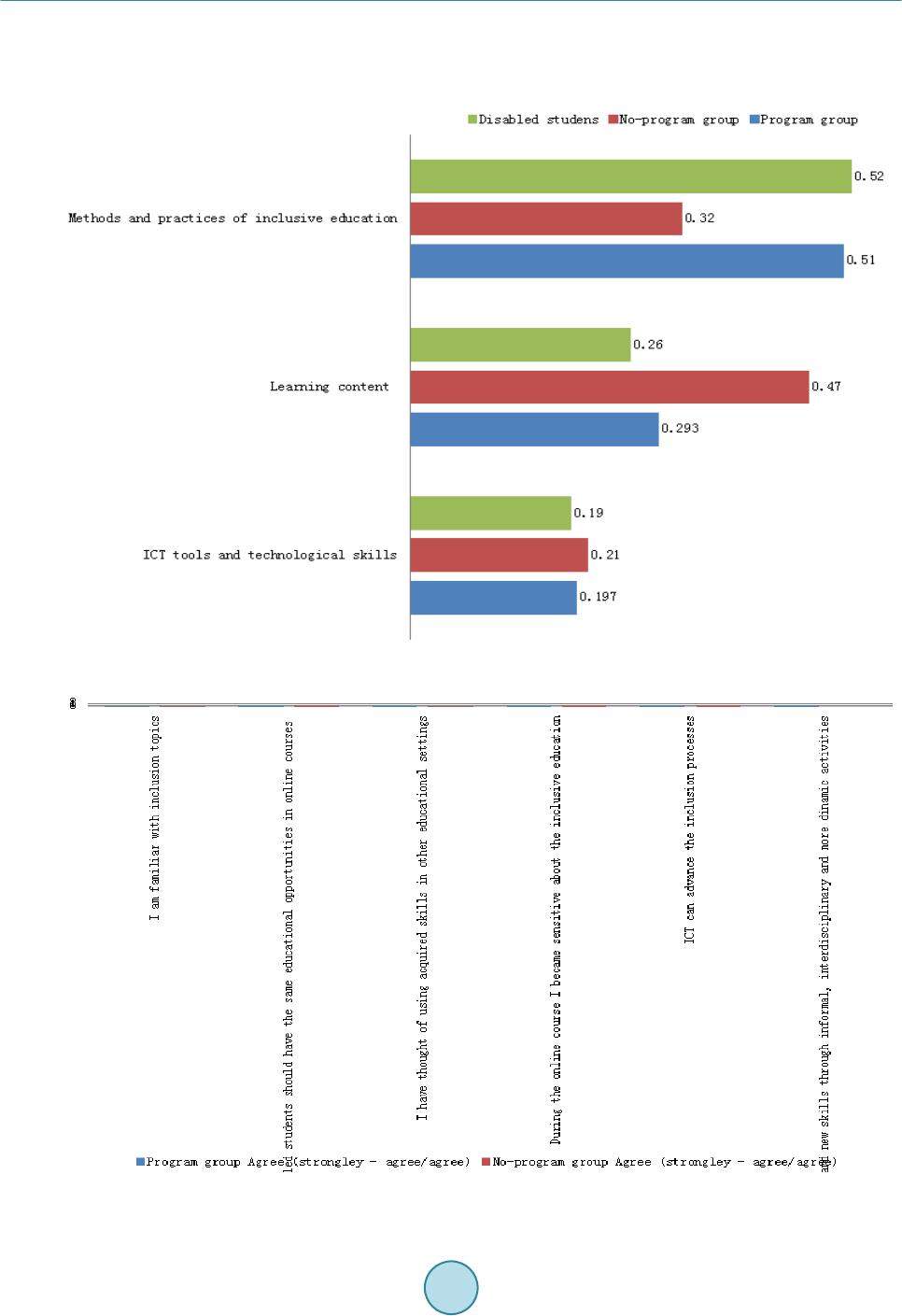

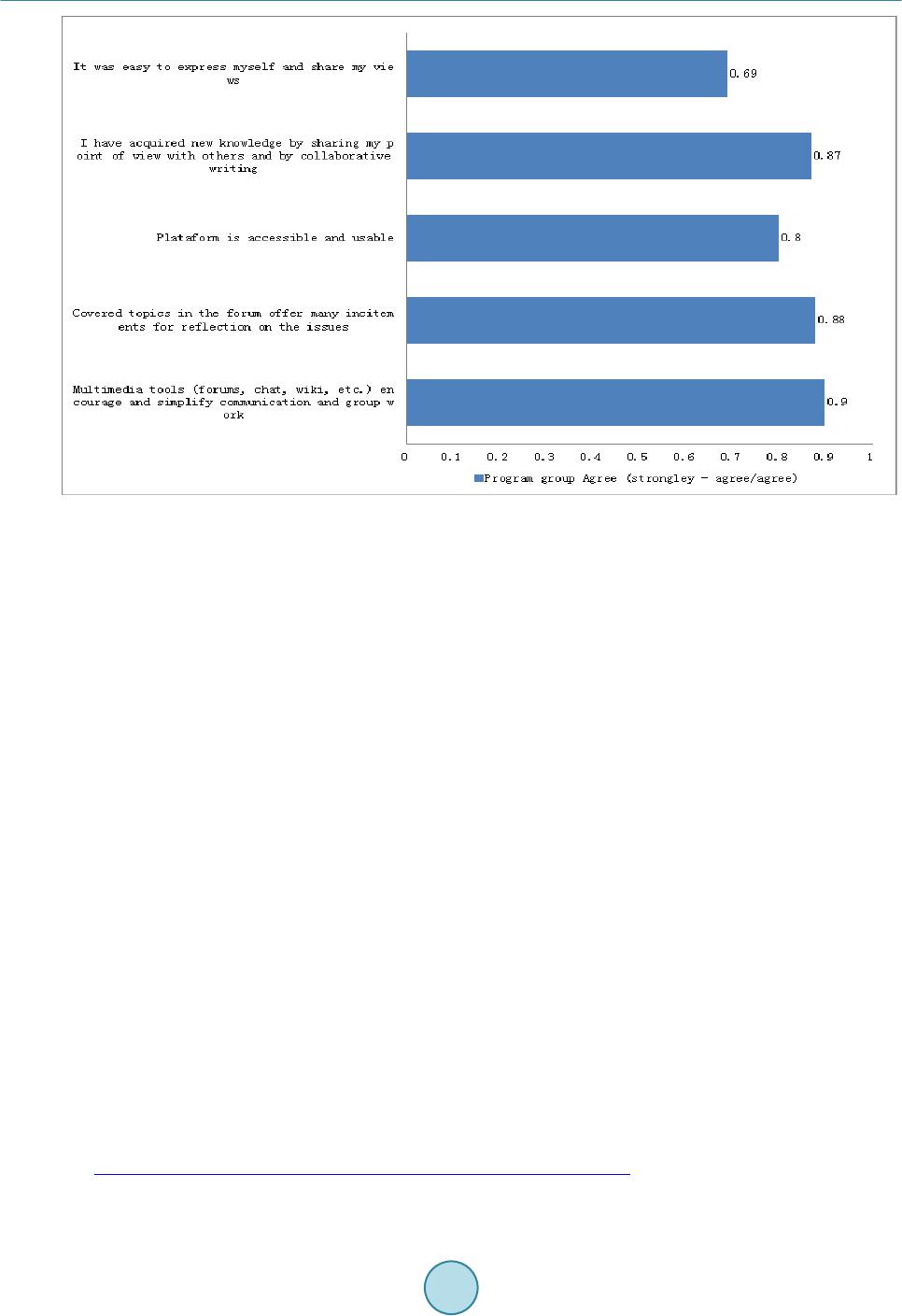

|