Journal of Environmental Protection, 2011, 2, 639-647 doi:10.4236/jep.2011.25073 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design Anthopoulos K. Petros1, Julia N. Georgi2 1Department of Physical Education and Sport Science, Democritus University of Thrace, Komotini, Greece; 2Hellenic Open Univer- sity, Patras, Greece. Email: panthopo@phyed.duth.gr, jgeorgi@tee.gr Received March 20th, 2011; revised May 1st, 2011; accepted June 13th, 2011. ABSTRACT This paper examined users’ preferences for landscape design of grounds and spaces surrounding hospitals, in order to assess how they perceived the landscape facilities so as to make future open spaces of hospitals suitable to users’ needs. The method of the research was based on quantifying a questionnaire survey of a representative sample of personnel (doctors, nurses, administrative staff and medical students) by using the stratified sample research programme that was carried out in March 2007 at the University Hospital of the city of Alexandroupolis, situated in northeastern Greece. The results of study show that users of hospital cared about footpaths, resting areas, social and public spaces, personal spaces, water features and a dominant, limited range of colors in landscaping. They also require environment that supports the principles and specifications of Therapeutic Hospital Gardens. Based on the results of this research, 1) interventions have been proposed (e.g., footpaths, resting areas, social and public spaces, personal spaces, water fea- tures and a dominant, limited range of colors in landscaping), and 2) the principles and specifications for the landscape design of Therapeutic Hospital Gardens have also been evaluated and have been redefined in the light of the study findings. These results also provide the opportunity for health care decision makers to apply and to incorporate user considerations into overall landscape design for current and future health care programs. Keywords: Therapeutic Garden, Horticultural Therapy, Landscape Design, Sample Investigation 1. Introduction and Methods People that were living in large and dense cities, a good quality of life depend largely on the quality of the urban environment [1]. Nearly four out of five European citi- zens live in urban areas where existing environmental quality limits are breached. Public parks and private gardens play a critical role in supporting biodiversity and providing important ecosys- tem services in urban areas [2,3]. Especially, green areas outside hospitals are considered not only to be necessary but also beneficial. Renewed interest in nature within the hospital environment has resulted in research document- ing the benefits of nature for reducing stress, improving mood, and increasing healthcare satisfaction [4-8]. Stud- ies described that even a few minutes of visual exposure to nature can significantly reduce patients stress [9]. The benefits that individuals can derive from plants and con- tact with nature have been discussed for thousands of years. Historical accounts suggest that this belief was an organizing principle for the exemplary hospitals of the past, where a primary goal was making patients more comfortable [10]. The main goal of this study was to investigate users’ attitudes towards landscape design regarding the existing and future improvements to outdoor grounds and spaces, by using a case study in order to collect data from the hospital users. The objectives of the study were: to deve- lop an understanding of users experience within the land- scape surrounding the hospital buildings; to investigate users considerations of landscape design in the impro- vement and maintenance of the landscape; to recognize and estimate the characteristics that the users who were surveyed felt they had contributed towards a sustainable friendly environment; to outline a set of recommenda- tions to improve the landscape that surrounds the hospi- tals; and to consider users’ needs in the planning and design of hospitals. 1.1. Historic Overview: Integration of Green Spaces in the Design of Hospitals Historical data have shown that the design of the spaces around hospitals was an important consideration in en-  Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design 640 suring that patients could feel comfortable, and that land- scape design played a very important role [10]. The no- tion of a healing space has its roots back to ancient Greece. Temples such as the sanctuary at Epidaurus were built for the god Asclepius, where ill people went in the hope of having dreams where he would reveal the cures for ailments [11]. Since the Middle Ages, hospitals with- in monasteries used the monastery gardens as areas for therapy and healing [12]. The patients’ rooms had a view of the hospital gardens, which could provide the patient with exposure to sunshine, a small lake, seasonal flowers, rest areas or footpaths. Saragossa hospital in Spain, which was built in 1409, is one such example that was used as inspiration from the landscape designers of that era, particularly with regards to the way patients could interact with one another. This became known in the ni- neteenth century as ‘Ethical Therapy’. In the Saragossa hospitals, patients were not shut in their rooms. Instead, the hospital’s garden was used for their treatment, and patients generally communicated with one another throughout the day in the outdoors [12]. Later, in 1860, Florence Nightingale extolled ventilation and fresh air as “the very first canon of nursing,” along with elimination of unnecessary noise, proper lighting, warmth, and clean water [11]. In contrast to that, American hospitals in the 17th cen- tury were offering bad environments for their patients. Buildings were small, rooms had no windows, there were no gardens and the treatment of psychopathic patients included the “tying of patients on piles” or the use of a type of “gallows” [13]. The European Romanticism Movement of the 18th century was the cause of many important changes in the design of hospital facilities and grounds. The theory connecting medical therapy with the existence of a natu- ral environment around hospitals was revived. Romanti- cism was a “pervading cultural movement, aiming at the unification of human emotions with morals and nature” [12]. Cooper Marcus [14] mentioned that in the 18th cen- tury, Dorothea Linde Dix (1802-1887) was the first to be interested in amending the patient’s therapy methods and, by extension, the hospital environment. She proposed certain basic principles to the American Legislative As- sembly concerning the arrangement of areas in these in- stitutions. However, in the 20th century, the progress in medical science, urbanization and technological developments and other economic forces led to the neglect of the ex- ternal areas of many hospitals [15]. Many hospitals in Europe added a method called “hor- ticultural therapy” (gardening) to their therapeutic pro- grams, which was aimed at “keeping the patients’ mind away from disaster and drive it to creative action” [12]. Horticultural therapy developed from the profession of occupational therapy and emerged as a distinct profes- sion in the U.S. in the 1950s. A well-designed hospital garden offers security, reduces stress, nourishes social contact and interaction, allows visitors to enjoy nature and helps in the development of senses, which cannot be developed within the structural environment of a city [9]. 1.2. Benefits of Nature Findings from several studies of non-patient groups sug- gest that even brief visual encounters with real or simu- lated natural settings can elicit significant psycho-phy- siologic restoration within as little as 3 - 5 min [6,16-18]. This restoration is manifested as reduced negative effects, and heightened positive effects and changes in physiolo- gic systems that are indicative of reduced arousal or stress mobilization (electrocortical, cardiovascular, neuroendo- crine and musculoskeletal) [17]. Accordingly, Sherman et al. [19] focused on the ac- tivities of the users in the hospital, and found that 66% of staff garden usage was in the form of “walk-throughs” from one place to another. Although this activity does not fully exploit the gardens to their full capacity, re- search such as Kaplan’s [20] on micro-restorative ex- periences suggests that even these brief encounters may enhance staff’s well-being and job satisfaction, both of which are predictors of patient healthcare satisfaction [21]. Furthermore, Douglas and Douglas [22] investigated patients’ perceptions based on qualitative and quantitative methodologies. The results from a questionnaire survey provide suggestions for radical improvements, and found a sustainable health care environment to be supported of the patients’ health and recovery. A number of studies have discussed the relationship between mental stress and the healing effect of the natu- ral and urban environment [6, 23-27]. One study supports the view that the hospital environment is stressful be- cause it is considered to be complex and not friendly [28]. The authors believe that continuous exposure to such an environment leads to mental (spiritual) exhaustion. In such cases, they recommend exposure to a less complex natural environment, which would enable them to rest, develop companionship and burden them with a smaller amount of information. Humans have a natural tendency to prefer the natural landscape rather than the built-up environment, particu- larly when the latter presents an absolute lack of vegeta- tion and water [29,30]. Many people who are under stress seek solace in the natural environment, which they be- lieve could make them feel better [13,31]. Cooper-Marcus and Barnes [13] evaluated four hospi- C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design641 tal gardens in the US with the use of observations and interviews of patients, visitors and staff. Their findings showed that from those interviewed 95% experienced a positive change of mood in the garden. During an inves- tigation conducted by Cooper-Marcus [32], a sample of students in California was asked to describe where they go when they wish to escape from a stressful situation. The majority (75%) answered that they go outdoors to a natural or designed environment. Ulrich [9], of the University of Texas, found that pa- tients’ views towards natural settings are associated with shorter hospital stays. Examining medical records, he found that patients who viewed trees during their recove- ry period needed fewer strong painkillers and their reco- very was quicker compared with patients who had a view of a wall. Furthermore, patients who were able to view trees more frequently received positive written comments from staff about their condition in their medical records (“patient is in good spirits”). Those patients with views of a wall, however, had far more negative evaluative comments (“patient is upset”, and “needs much encour- agement”). The hospital staff can also benefit from it by having access to windows that make it possible to view garden spaces [33]. Indirect proof of the aforementioned is the satisfaction that patients and staff express when they find themselves in a natural environment, compared with be- ing inside the hospital building [13]. 2. Methodology Initially, a team of expert scientists (Landscape architect, Forester, Medical doctor) edit a questionnaire with ques- tions including refreshing area, cheerful environment, scenic view; open space, freedom to play, and a variety of activities were asked upon the users for the outdoor space of hospital. The collection of the information was conducted through questionnaires to 102 users (5% of the total population occupied in the hospital). 2.1. User Attitude Survey Method This research was carried out at the new University Hos- pital of Alexandroupolis (Greece), which is located 6 km west of the city and is developed along the coastal road axis. The existing environmental situation surrounding the hospital is at an early stage and no specific plans have been applied. The University Hospital in northeastern Greece (Figure 1) provides local, regional and national services, has approximately 630 beds, and employs 1,180 staff. It was established in 2002 after the relocation of Alexandroupolis National Hospital. From the front of the hospital one can see panoramic views of the coast line and from the back view the surrounding mountains. These factors influence the users’ perceptions, their ex- Figure 1. Map of Greece where it is pointed out the area of study. periences and their subsequent view and opinions for the surrounding environment of the hospital [22]. 2.2. Method Description This research includes the compilation of a questionnaire with pre-coded questions, so it would be easy for those being asked to answer them. The answers were collected through personal interviews, which were given by the hospital staff face-to-face and were then processed with the use of a statistic program SPSS V 15. The questionnaire was developed according to the fol- lowing principles: 1) limitation of a question to one idea; 2) no ques- tions accepting multiple complex answers; 3) avoiding leading questions; 4) simple language; 5) avoiding ne- gative or conditional answers; and 6) posing only neces- sary questions [34,35]. The responders were chosen from groups of staff me- mbers that work in the hospital. Their responses repre- sented their own preferences and perceptions as well as their knowledge of the experiences from patients and vi- sitors. Most efforts with regards to the aesthetics evalua- tion of the landscape are based on users and not on “spe- cial estimators” (Landscape architecture, Forester). Ex- pert scientists accept that the evaluation of each land- scape depends on human needs, wishes, and, consequ- ently, human preferences [36]. The method used for the landscape evaluation on the basis of people’s preferences is a basic method, which has become more and more accepted [37,38]. This is because it achieves the direct participation of the public, which is indeed the group of people who are directly, interested in “decision taking while expressing their preferences” [39]. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design 642 This research was carried out using a method referred as ‘stratified sampling’. The total population was divided into homogeneous, non-overlapping sub-population groups, called ‘strata’. This stratified sampling method is indi- cated for similar research, because it presents smaller losses in the evaluation of the various parameters com- pared with the ‘simple random sampling’ method [40]. People were divided into four strata on the basis of their specialty in the hospital. The strata were as follows: stra- tum Α: doctors; stratum Β: nurses; stratum C: adminis- trative Staff; stratum D: medical students. Responders were selected to provide diversity both in terms of their length of experience and the type of speci- alty area across the major clinical divisions of the hospi- tal. Thus, the researchers sought to interview a variety of responders comprising the young and middle-aged as well as males and females. Consequently, sample size was determined using the method of “proportional allocation” of the number in each stratum. The size of each stratum was as follows: doctors: 350; nurses: 450; administrative staff: 380; and medical students: 683. The size of each sample was 5% of the people surveyed. We observed a limitation of n/N < 0.10 (Ν is the size of people and n is the size of sam- ple), this is required so that sample taking is considered to be independent and the sample is considered to be random. It also enables us to avoid “finite population correction” [41]. We obtained a final sample of approxi- mately 6%, which is close to the original target of 5% of the total population occupied in the hospital. This meets the aforementioned requirements and additionally gives a value of n = 102 (doctors 21, nurses 23, administrative staff 24, and medical students 34), which is also accepted by the following formula for n-optimum: 2 2 2 11 a nNS dzN where S2: Dispersion, 1-a: level of trust, and d: area of error. For acceptable values of error d departure of estima- tors from estimated data, as well as trust level 1-a. S 2 factor has been estimated from a first sample [42]. 3. Results From the field survey, an average response rate of 95% participated and completed the questionnaires from ap- proximately 6% of the population. For most questions responses were satisfactorily numerous and provided sufficiently distinct decisions to make reasonably confi- dent predictions for the overall population and for com- parison between the different groups. The first question in the survey of the selected hospital staff asked them how satisfied the person was with the current outdoor space area of the hospital. The majority of doctors, nurses, administrative staff and medical stu- dents replied “a little” and “not at all” (Table 1). These responses are expected because of the current condition of the hospital outdoor spaces. The second question asked which part of the outdoor space of the hospital would the responder would like to increase its availability. As shown in Table 2, the major- ity of users of outdoor space prefer “green areas” (50% nurses to 90% doctors) and “rest areas” (5% doctors to 37.5% nurses). A significant percentage of administrative staff (18.3%) prefers to increase the “parking areas” even though currently, the hospital provides parking that ac- commodates 350 spaces. This response may be because the staff would like to have more convenient access to parking spaces, especially after long hours of work. In the third question, when the responders were asked whether they would wish for a garden with trees and bushes in the outdoor space of the hospital, the majority of doctors, nurses, administrative staff and medical stu- dents expressed their wish for this type of garden as it can be seen in Table 3. The fourth question asked whether the person believes that landscape design with green areas in the outdoor space of the hospital would positively affect their psy- chology. The majority of doctors (95%) gave a positive answer, compared with nurses (79.2%), whereas the re- maining 20.8% doubted the effect that greenery would have on their psychology. Two-thirds (72.7%) of admin- istrative staff favored the effect of greenery on their mood, whereas 18.2% had doubts about the effects, and 9.1% considered greenery to have no effect. Table 4 provides shows the findings for question four. The ma- jority of Students believed that greenery would have a positive effect on their mood. Regarding question five, which asked whether the per- son would wish to spend their rest time in a well-designed landscape surrounding the hospital, the majority of doc- tors, nurses, administrative staff and medical students gave a positive answer. We believe that a high percent- age of Administrative Staff gave a negative answer be- cause of too much pressure of work as it can be seen in Table 5. Question six asked what kind of vegetation the person would wish to be planted in the hospital’s garden. The majority of users wished for a combination of trees and bushes because the variation of trees and bushes can pro- vide a natural character to the garden (Table 6). A sig- nificant percentage of nurses seem also to prefer medium and small trees. Question seven asked whether the person would wish for water features in the outdoor space of the hospital. As shown in Table 7, a high percentage (70%) of doctors and 91.7% of nurses, and 80.6% of students wished for C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 643 Table 1. How satisfied are you with the current outdoor space area of the hospital? (%). a lot a little not at all Doctors 5 45 50 Nurses 12.5 75 12.5 Administrative Staff 13.6 63.7 22.7 Medical Students 8.3 75 16.7 Table 2. Which part of the outdoor space of the hospital would you wish to increase? (%) Green areas Parking areasRest areas Isolated areas Water formations Doctors 90 5 5 0 0 Nurses 50 4.2 37.5 8.3 0 Administrative Staff 63.6 18.3 13.6 0 4.5 Medical Students 52.8 13.9 25 8,3 0 Table 3. Would you like a garden with trees and bushes in the outdoor space of the hospital to exist? (%) a lot a little not at all Doctors 90 10 0 Nurses 70.8 29.2 0 Administrative Staff 77.3 18.2 4.5 Medical Students 80.6 16.6 2.8 Table 4. Do you believe that landscape design with green areas in the outdoor space of the hospital would positively affect your psycho logic status? (%) Yes Maybe No Doctors 95 5 0 Nurses 79.2 20.8 0 Administrative Staff 72.7 18.2 9.1 Medical Students 91.7 8.3 0 Table 5. Do you want to spend your r est time in a well-designed landscape surr o unding the hospital? (%) Yes No Doctors 85 15 Nurses 95.8 4.2 Administrative Staff 81.8 18.2 Medical Students 94.4 5.6 Table 6. What kind of vegetation would you like to be plante d in the hospital’s gar den? (%) High trees Medium height treesSmall trees Bushes Combination of trees and bushes Doctors 5 15 15 15 50 Nurses 4.2 29.2 20.8 8.3 37.5 Administrative Staff 9.2 4.5 13.6 0 72.7 Medical Students 11.1 22.2 11.1 0 55.6 Table 7. Do you wish for water features in the outdoor space of the hospital? (%) Yes No Doctors 70 30 Nurses 91.7 8.3 Administrative Staff 50 50 Medical Students 80.6 19.4  Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design 644 water features, while only 50% of administrative staff gave a positive answer. Question eight asked what combination of colors would the person wish to see prevail in the hospital’s garden. As shown in Table 8, a monochromatic color character received low preferences from the responders: 10% of doctors, 8.3% of nurses, 4.5% of administrative staff, and 8.3% of students. The preference responses increased for a garden with color: variegated character garden (40% of doctors, 50% of nurses, 31.8% of admin- istrative staff and 44.4% of students; while preference for a limited number of colors in a garden received medium range responses: 50% of doctors, 41.7% of nurses, 63.7% of administrative staff and 47.3% of students. In question nine which asked what kind of activities would the person wish to have to exercise in the hospi- tal’s garden; the results vary between the responders. The detailed responses are shown in Table 9. Where 50% of doctors, 41.7% of nurses, 36.4% of administrative staff and 61.1% of students would wish to use the garden to rest, 10% of doctors, 8.3% of nurses and 9.1% of admin- istrative staff would wish to be able to observe the land- scape from inside the buildings. Furthermore, the garden as a place for having lunch received a preference of 10% from doctors, 8.3% from nurses, 22.7% from administra- tive staff, and 19.4% from students; while the garden as a place to go to avoid stressful work situations was pre- ferred by 30% of doctors, 29.2% of nurses, 31.8% of administrative staff and 16.7% of students. In addition, 12.5% of nurses and 2.8% of students would wish to be able to have a garden to walk in. Question ten asked whether the responder believes that a garden would help the patients to recover. The review of the responses in Table 10 show that the majority of doctors, nurses, administrative staff and students replied “a lot”. It is worth noting that a significant number of administrative staff (27.3%) replied “a little”. It appears that the administrative staff’s response maybe due to the fact that the majority of the staff has only secondary level education as it can be seen in Table 10. In question eleven, which asked what type of physical improvements would the responder wish to be carried out in the outdoor spaces of the hospital, the majority of the responders would wish for footpaths (55.6% - 72.7%); a place to have lunch in the open air is preferred by doctors (10%), by nurses (16.7%), by administrative staff (9.1%), and by students (27.8%). Other improvements included shade areas where people could rest and observe (5% of doctors, 8.3% of nurses, 4.5% of administrative staff and 2.8% of students); and a playground for the pediatrics division and for the young visitors to the hospital (5% of doctors, 9.1% of administrative staff and 5.6% of stu- dents (Table 11). 4. Discussion The results of this research project are revealing and give us insight on the views and preferences of the staff at the Alexandroupolis University hospital, with regards to open space associated with the hospital. The majority of respondents were not satisfied with the current situation of the open space surrounding the hospital. With the ex- ception of the installation of some hard surfaces and parking lots, no other open space and green space impro- vements were made since the hospital was constructed. The staff expressed a strong desire for a well-designed landscape that surrounds the hospital, and it felt that this would make for a positive contribution to its mood and well being, and would offer the opportunity to spend part of their free time there. Similar results were found in a study about the behavior of consumers in a children’s hospital in U.S. [8]. The results of this research demonstrate that people prefer a well-designed landscape that includes a variety of plant materials. However, if we examine the results from question three we observed an indifference to the presence of a garden by the nursing staff (29.2%), ad- ministrative staff (22.7%), and medical students (19.4%). The respective percentage of the medical staff is particu- larly low (10%). A possible explanation for the afore- mentioned results is that nurses and administrative staff have a high workload, which directly results in not al- lowing them to spend much time outside of the hospital buildings. They prefer to spend their free time in places that allow for more social interaction and entertainment. Similar studies have been carried out by Cooper-Marcus and Barnes [16], in which they used a combination of behavioral observations and interview methods to evalu- ate four hospital gardens in California. They found that restoration from stress, including improved mood, was by far the most important category of benefits derived by nearly all users of the gardens - patients, family and em- ployees. Similarly, another study of a garden in a chil- dren’s hospital identified mood improvement and resto- ration from stress as primary benefits for users [8]. Most people working in the hospital would wish for additional planting of various types of plants, and for certain areas to be defined at their perimeter with tall trees. The majority of staff (54%) would wish to see new trees and shrubs of a variety of sizes and height. This variation in size of trees and shrubs can give a natural character to the garden, creating the feeling of a ran- domly planted natural environment. Planting design of these open areas should be sensitive to views afforded from inside the hospital buildings, so that views from se- lected areas to the outdoor spaces can remain unobstructed, and contribute to the mood of both patients and vistors. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design645 Table 8. What combination of colors would you like to see prevailing in the hospital’s garden? (%). Monochromie Limited number of colours Variegation Doctors 10 50 40 Nurses 8.3 41.7 50 Administrative Staff 4.5 63.7 31.8 Medical Students 8.3 47.3 44.4 Table 9. What kind of activities would you wish to exercise in the hospital’s garden? (%). Rest Landscape observation picnic Avoidance of a stressful environment Walking Doctors 50 10 10 30 0 Nurses 41.7 8.3 8.3 29.2 12.5 Administrative Staff 36.4 9.1 22.7 31.8 0 Medical Students 61.1 0 19.4 16.7 2.8 Table 10. Do you believe a garden would help the patie nts to recover ? (%). A lot A little Doctors 100 0 Nurses 83.3 16.7 Administrative Staff 72.7 27.3 Medical Students 88.9 11.1 Table 11. What constructions would you wish to be carried out in the outdoor space of the hospital? (%). Footpaths Picnic areas Playgrounds Gymnastic areasVegetation Indoor areas Doctors 70 15 5 0 5 5 Nurses 70.8 20.8 0 0 4.2 4.2 Administrative Staff 63.6 18.2 9.1 0 9.1 0 Medical Students 58.3 36.1 2.8 2.8 0 0 The results of the study show that the majority of the responders (92.2%) wished for a landscape scheme that is multi-colored as opposed to monochromatic plantings. This was also true for the students who prefer plant spe- cies that provide good shade during summer and could create an improved microenvironment. Native species of local origin should generally be preferred [43] and non- indigenous plants should be avoided [44]. The selection of trees and shrubs should be done carefully, with special attention to the mix of color of foliage and flower as ex- pressed by responders. In addition, the responders seemed to favor the con- struction of footpaths, rest areas, social and public areas, and water features. A “garden” is expected to provide people with the convenience to walk, stand, and rest in areas that are especially arranged for this purpose, and where people have the possibility to enjoy their lunch or the cool breeze. Finally, the staff understood, to a large extent, the im- portance of having a green landscape for improving the psychology and healing of patients. They understand that the presence of a planted landscape would compliment conventional therapy methods, ensuring faster and better results. It should be pointed out that all doctors who re- sponded to the survey (100%) gave a positive reply for the possibility of improving the psycho logic status of the patients with the use of outdoor gardens. Evidence from studies of a number of different hospitals and diverse categories of patients (adults, children, and elderly pa- tients; ambulatory or outpatient settings; and inpatient acute care wards) strongly suggests that the presence of nature—indoor and outdoor gardens, plants and window views of nature—increases both patient and family satis- faction [8,13,45]. 5. Conclusions While the healing garden is a preceding concept, it is being revived in modern societies because of the com- prehensive therapeutic benefits such places can offer. These benefits have high implication for hospital staff Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design 646 and students who are at a critical stage of development of their bodies and minds. In similar finding conclude the research by English et al. [46] where they suggest a strong interplay between emotions and place such that emo- tional geographies, which appear to be embedded within places of healing, play an important role in shaping and maintaining therapeutic landscapes. Furthermore, the research suggests a strong interplay between emotions and place such that emotional geogra- phies, which appear to be embedded within places of healing, play an important role in shaping and maintain- ing therapeutic landscapes. All the groups of the users of the case study hospital gave their considerations for the external design of the hospital, so the profession of expert scientists of land- scape planning will be easier and more properly. Users of hospital cared about footpaths, resting areas, social and public spaces, personal spaces, water features and a do- minant, limited range of colors in landscaping. Users re- quire environment that supports the principles and speci- fications of Therapeutic Hospital Gardens. This study of hospital gardens demonstrates the feasi- bility of objective and landscape guidelines from which valid design implications can be drawn. When designing a hospital garden, these findings suggest that designers should include design features that enable the patient to sit and socialize or to relax, as well as being able to enjoy the water features and the paths around the garden. These results also provide the opportunity for health care deci- sion makers to apply and to incorporate user considera- tions into overall landscape design for current and future health care programs. 6. Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank Professor Menelaos Trianta- fillou (Harvard University Graduated) at University of Cincinnati for his pre-review of the paper. The authors wish also to thank the users of the hospital that took place and agreed to be interviewed. REFERENCES [1] E. S. Van Leeuwen, R. Vreeker and C. A. Rodenburg, “A Framework for Quality of Life Assessment of Urban Green Areas in Europe: An Application to District Park Reudnitz Leipzig,” International Journal of Environ- mental Technology and Management, Vol. 6, No. 1-2, 2006, pp. 111-122. doi:10.1504/IJETM.2006.008256 [2] K. J. Gaston, P. H. Warren, K. Thompson and R. M. Smith, “Urban Domestic Gardens (IV): The Extent of the Resource and Its Associated Fearures,” Biodiversity Con- servation, Vol. 14, No. 14, 2005, pp. 3327-3349. doi:10.1007/s10531-004-9513-9 [3] R. M. Smith, K. J. Gaston, P. H. Warren and K. Thomp- son, “Urban Domestic Gardens (V): Relationships be- tween Land Cover Composition, Housing and Land- scape,” Landscape Ecology, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2005, pp. 235-253. doi:10.1007/s10980-004-3160-0 [4] K. M. Beauchemin and P. Hays, “Sunny Hospital Rooms Expediate Recovery from Severe and Refractory Depres- sions,” Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 40, No. 1-2, 1996, pp. 49-51. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(96)00040-7 [5] C. Cooper-Marcus and M. Barnes, “Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations,” John Wiley, New York, 1999. [6] R. S. Ulrich, “Effects of Interior Design on Wellness: Theory and Recent Scientific Research,” Journal of Healthcare Interior Design, Vol. 3, 1991, pp. 97-109. [7] J. W. Varni, T. M. Burwinkle, P. Dickinson, S. A. Sher- man, P. Dixon, J. A. Ervice, et al., “Evaluation of the Built Environment at a Children’s Convalescent Hospital: Development of the Peds QLTM Parent and Staff Satis- faction Measures for Pediatric Healthcare Facilities,” Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Vol. 25, 2004, pp. 10-25. doi:10.1097/00004703-200402000-00002 [8] S. Whitehouse, J. W. Varni and M. Seid, C. Coo- per-Marcus, M. J. Ensberg, J. R. Jacobs, et al., “Evaluat- ing a Children’s Hospital Garden Environment: Utiliza- tion and Consumer Satisfaction,” Journal of Environ- mental Psychology, Vol. 21, 2001, pp. 301-314. doi:10.1006/jevp.2001.0224 [9] R. S. Ulrich, “View through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery,” Science, Vol. 224, No. 4647, 1984, pp. 420-421. doi:10.1126/science.6143402 [10] A. B. Stein, “Thoughts Occasioned by the Old Testa- ment,” In: M. Francis and R. T. Hester, Eds., The Mean- ing of Gardens, The MIT Press, Mass, 1990, pp. 38-45. [11] S. Ananth, “Building Healing Spaces Optimal Healing Environments,” Explore, Vol. 4, No. 6, 2008, p. 393. [12] S. B. Warner Jr., “The Periodic Rediscoveries of Restora- tive Gardens: 1100 to the Present,” In: M. Francis, P. Lindsey and J. S. Rice, Eds., The Healing Dimensions of People-Plant Relations, Proceedings of a Research Sym- posium, Davis, University of California, 1995, pp 5-12. [13] C. Cooper-Marcus and M. Barnes, “Gardens in Health- care Facilities: Uses, Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations,” The Center for Health Design, Mar- tinez, 1995. [14] B. L. Fredrickson and R. W. Levenson, “Positive Emo- tions Speed Recovery from the Cardiovascular Sequelae of Negative Emotions,” Cognitive Emotions, Vol. 12, No. 2, 1998, pp. 191-220. doi:10.1080/026999398379718 [15] N. Sachs, “The Therapeutic Value of Outdoor Space in Psychiatric Healthcare Facilities,” MLA Thesis, Univer- sity of California, Berkeley, 1999. [16] T. Hartig, A. Book, J. Garvill, T. Olsson and T. Garling, “Environmental Influences on Psychological Restora- tion,” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, Vol. 37, No. 4, 1995, pp. 378-393. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.1996.tb00670.x [17] R. Parsons and T. Hartig, “Environmental Psychophysi- C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 647 ology,” In: J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, G. G. Bernt- son, Eds., Handbook of Psychophysiology, 2nd Edition, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2000, pp. 815-846. [18] A. Van den Berg, S. L. Koole and N. Y. Van der Wulp, “Environmental Preference and Restoration: How Are They Related?” Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2003, pp. 135-146. doi:10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00111-1 [19] S. A. Sherman, J. W. Varni, R. S. Ulrich and V. L. Mal- carne, “Post-Occupancy Evaluation of Healing Gardens in a Pediatric Cancer Center,” Landscape and Urban Plan- ning, Vol. 73, No. 2-3, 2005, pp. 167-183. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2004.11.013 [20] R. Kaplan, “The Nature of the View from Home: Psy- chological Benefits,” Environmental Behavior, Vol. 33, No. 4, 2001, pp. 507-542. doi:10.1177/00139160121973115 [21] M. P. Leiter, P. Harvie and C. Frizzell, “The Correspon- dence of Patient Satisfaction and Nurse Burnout,” Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 47, No. 10, 1998, pp. 1611- 1617. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00207-X [22] C. H. Douglas and M. Douglas, “Patient-Friendly Hospi- tal Environments: Exploring the Patients’ Perspective,” Health Expectations, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2004, pp. 61-73. doi:10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00251.x [23] R. Kaplan and S. Kaplan, “The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective,” Cambridge University Press, 1989. [24] R. S. Ulrich, “A Theory of Supportive Design for Health- care Facilities,” Journal of Healthcare Design, Vol. 9, 1997, pp. 3-7. [25] T. Hancock, “Creating Health and Health Promoting Hospitals: A Worthy Challenge for the Twenty-First Century,” International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance incorporating Leadership in Health Services, Vol. 12, No. 2, 1999, pp. 8-19. doi:10.1108/13660759910266784 [26] S. Francis, R. Glanville, A. Noble and P. Scher, “50 Years of Ideas in Health Care Buildings,” The Nuffield Trust, London, 1999. [27] M. Riediker, H. S. Koren, “The Importance of Environ- mental Exposures to Physical, Mental and Social Well- Being,” International Journal of Hygiene and Environ- mental Health, Vol. 207, No. 3, 2004, pp. 193-201. doi:10.1078/1438-4639-00284 [28] R. Kaplan and S. Kaplan, “Cognition and Environment: Functioning in an Uncertain World,” Praeger Publishers, New York, 1983. [29] R. S. Ulrich, “Visual Landscape Preference: A Model and Application,” Man-Environment Systems, Vol. 7, No. 5, 1977, pp. 279-293. [30] H. W. Schroeder, “Preference and Meaning of Arboretum Landscapes: Combining Quantitative and Qualitative da- ta,” In: A. Sinha, Ed., Readings in Environmental Psy- chology and Landscape Perception, Academic Press, San Diego, 1995. [31] R. B. Bechtel, “Environment and Behavior: An Introduc- tion,” Sage Publications, Inc, 1997, p. 709. [32] C. Cooper Marcus, “Places People Take Their Problems,” In: M. Francis, P. Lindsey and J. S. Rice, Eds., The Heal- ing Dimensions of People-plant Relations: Proceedings of a Research Symposium, University of California, Davis, 1995. [33] S. F. Verderber, “Dimensions of Person—Window Tran- sactions in the Hospital Environment,” Environment and Behavior, Vol. 18, No. 4, 1986, pp. 450-466. doi:10.1177/0013916586184002 [34] D. M. Crapo and M. Chubb, “Recreation Area Day-Use Investigation Techniques: A Study of Survey Methodol- ogy”, Techical Report, Michigan State University, Vol. 6, 1969, p. 118. [35] N. Eleftheriadis, N. J. Georgi, S. Athanasiadis and E. Koutsukidou, “Forest Recreation and Landscape Archi- tecture,” T.E.I. Kavala, Drama (in Greek), 2002. [36] T. C. Daniel and J. Vinning, “Methodological Issues in Assessment of Landscape Quality,” Behavior and the Natural Environment, Vol. 2, 1983, pp. 39-83. [37] S. Kaplan, “Where Cognition and Affect Meet: A Theo- retical Analysis of Preference,” In: P. Bart, Ed., Knowl- edge for Design, Washington D.C., 1982, pp. 183-188. [38] S. Amir and E. Gidalizon, “Expert Based Method for the Evaluation of Visual Absorption Capacity of the Land- scape,” Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 30, 1990, pp. 251-263. doi:10.1016/0301-4797(90)90005-H [39] M. C. Dunn, “Landscape with Photographs: Testing the Preference Approach to Landscape Evaluation,” Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 4, 1976, pp. 15-26. [40] M. Loukakis, “Cluster Analysis. Algorithmic Approach in the Frames of Theory of Histograms,” Thessaloniki, 1982. [41] Ch. Zacharopoulou, “Statistics. Methods—Application Part A,” Giachouli & Son, Thessaloniki, 1993. [42] Ch. Damianos, “Introduction of the Theory of Sampling Method,” Athens (in Greek), 1986. [43] J. N. Georgi and D. Dimitriou, “The Contribution of Ur- ban Green Spaces to the Improvement of Environment in cities: Case Study of Chania,” Building and Environment, Greece, 2010. [44] P. Anthopoulos, “Evaluation and Landscape Design of the Surrounding Site of Hospitals. Case Study: General Pre- fecture University Hospital of Alexandroupolis,” M.Sc. Thesis, Hellenic Open University, Patra, 2003, p. 150 (in Greek). [45] Picker Institute and Center for Health Design, “Assessing the Built Environment from the Patient and Family Per- spective: Health Care Design Action Kit,” The Center for Health Design, Walnut Creek, 1999. [46] J. English, K. Wilson and S. Keller-Olaman Health, “Health Healing and Recovery: Therapeutic Landscapes and the Everyday Lives of Breast Cancer Survivors,” So- cial Science & Medicine, Vol. 67, No. 9, 2008, pp. 68-78. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.043

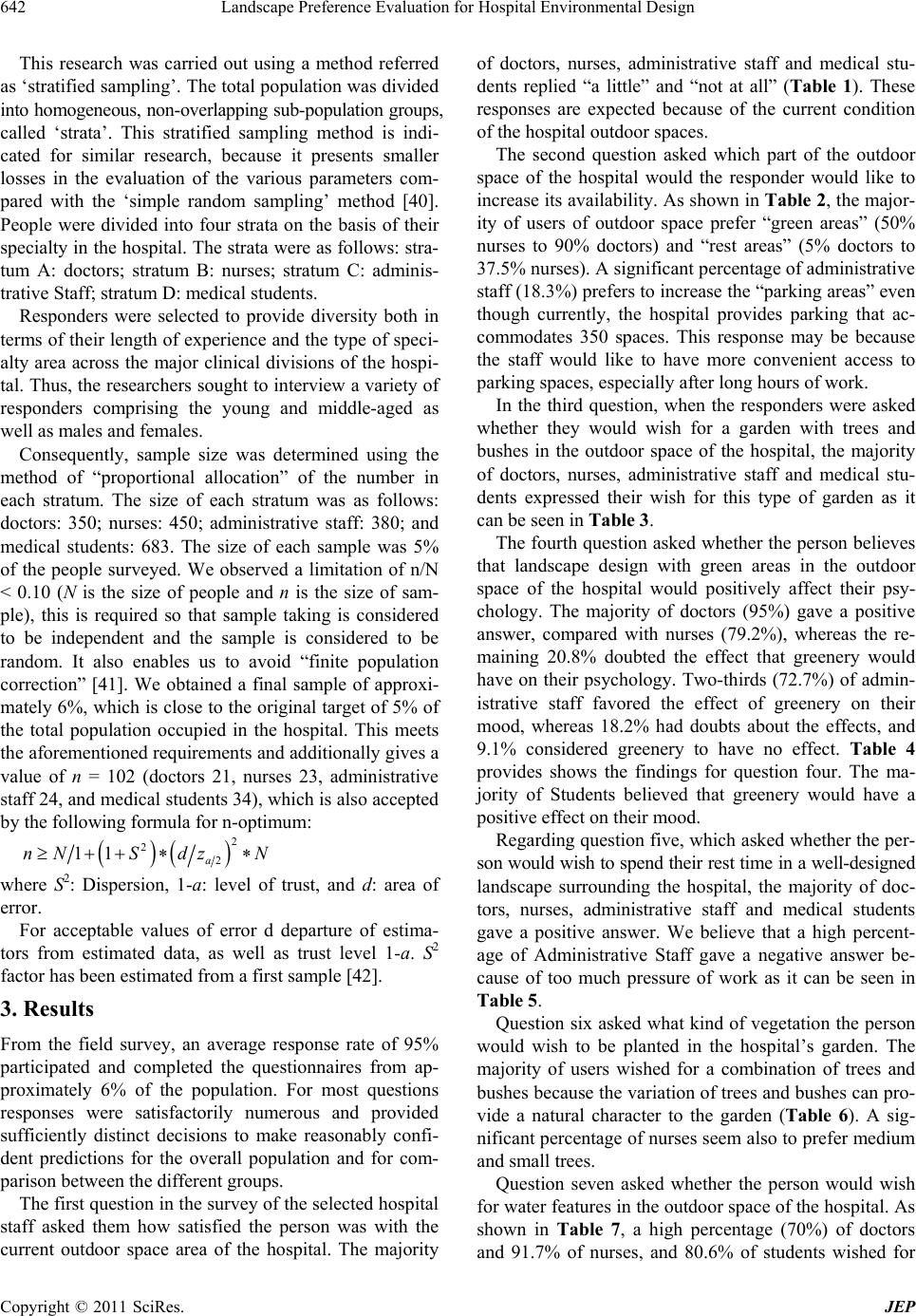

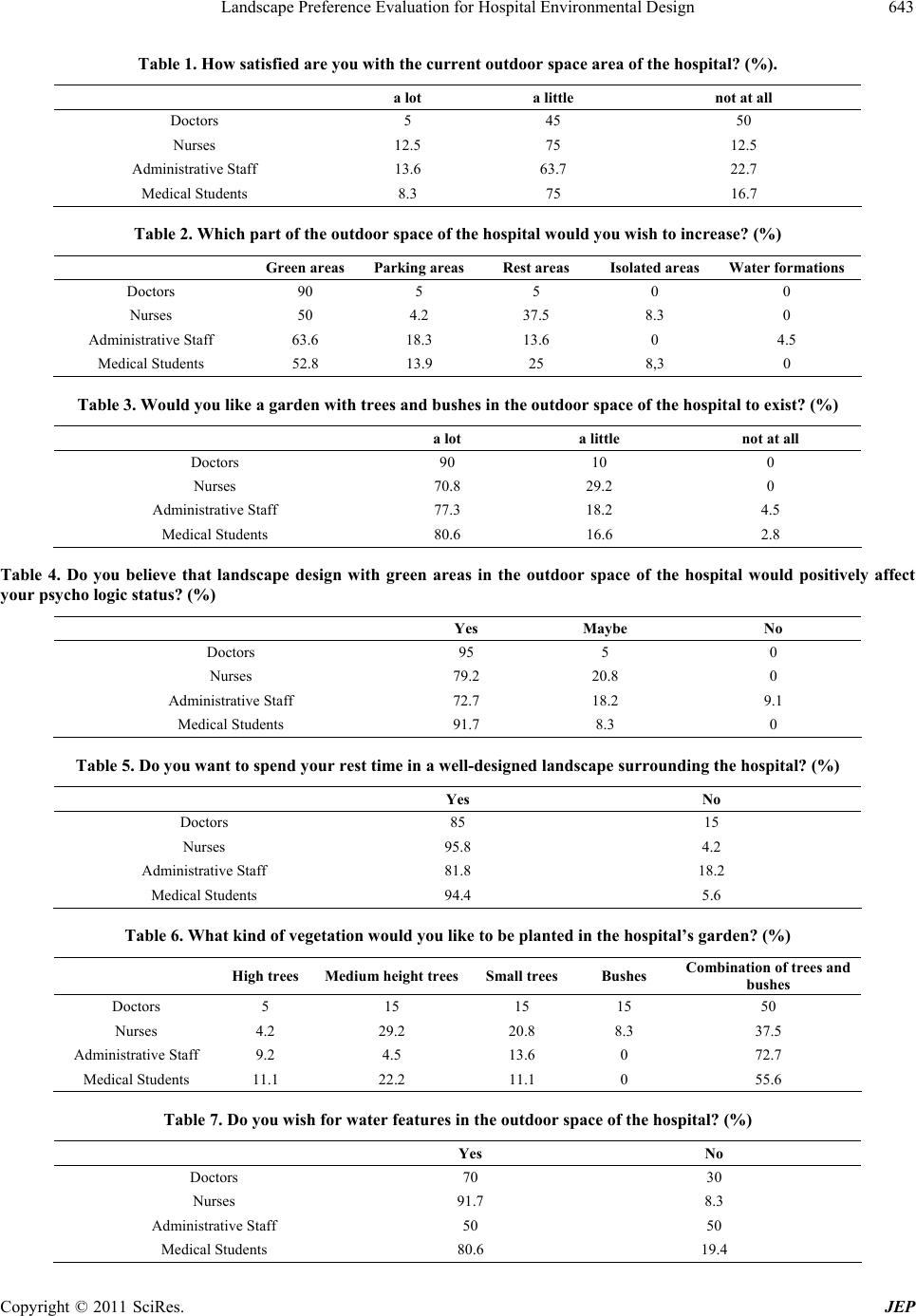

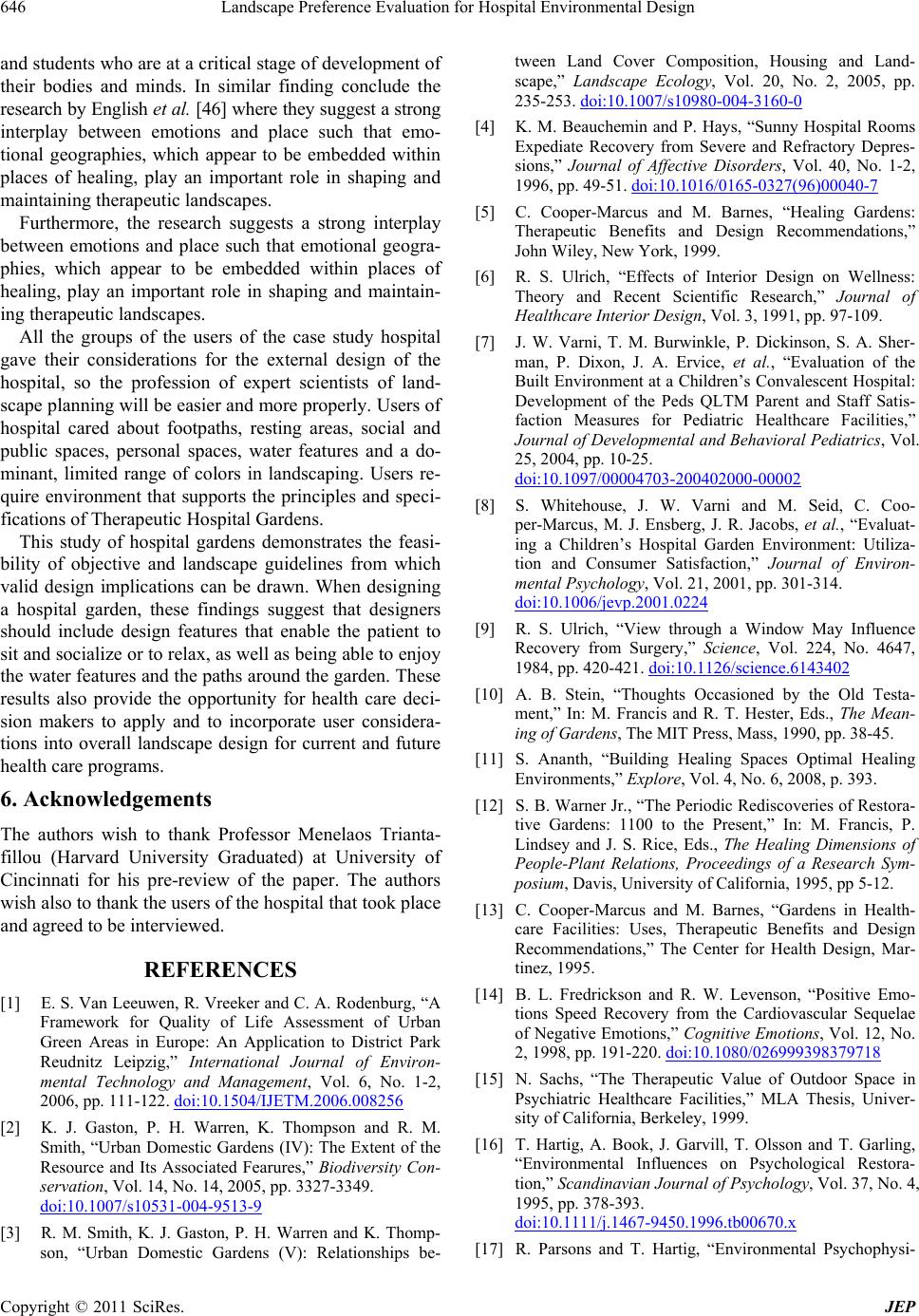

|