International Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2011, 2, 246-253 doi:10.4236/ijcm.2011.23039 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ijcm) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM Clinical Presentation and Outcome in Patients of over 75 Years Old with Malignant Lymphoma —Clinical Presentation and Outcome in Elderly Lymphoma Patients Noriyasu Fukushima1, Hideaki Itamura1, Chisako Urata1, Mariko Tanaka1, Takashi Hisatomi1, Yasushi Kubota1, Eisaburo Sueoka2, Shinya Kimura1* 1Division of Hematology, Respiratory Medicine and Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Saga Univer- sity, Saga, Japan; 2Department of Transfusion Medicine, Saga University Hospital, Sage, Japan. Email: *shkimu@post.saga-med.ac.jp Received March 25th, 2011; revised June 5th, 2011; accepted July 1st, 2011. ABSTRACT We analyzed the relationship between the clinical charac teristics, comorbidity, average relative dose intensity (aRDI) and outcome in patients of over 75 years old with malignant lymphoma. Of the 98 patients studied, the m ean age wa s 79.9 years, and 68 patients (69.4%) had B-cell lymphomas, corresponding to mainly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The 5-year overall survival rate was 32.2% in 97 malignant lymphoma patients. T/NK subtype, poor performance status (PS) and high-intermediate/high international prognostic index (IPI) were found to be predictive of significantly poorer overall survival, as is the case in young patients. Correlation between como rbidity index and surviva l rate was not observed. We also analyzed the aRDI of cyclophosphamide and pirarubicin for 64/97 patients. The proportion of patients receiving ≤84% of the planned DI during five cycles gradually increased. Most patients could not maintain aRDI ≥ 85%. However, overall survival was not significantly different between patients with aRDI ≥ 0.85 and those with aRDI ≤ 0.84. In conclusion, the prognoses of very elderly patients with malignant lymphoma were not so poor when they were appropriately treated with modification of the applied dose and the duration of chemotherapy ac- cord in g to their s tatus. Keywords: Malignant Lymphoma, Elderly, Comorbidity, Relative Dose Intensity 1. Introduction The medical burden of the elderly Japanese population is increasing very rapidly, with people aged > 75 years now accounting for >10% of the population [1]. With an in- creasingly aged population, morbidity and mortality due to various cancers, including malignant lymphoma, among people aged > 70 years will also increase. In 2000, the age-specific incidence rates of malignant lymphoma in Japan were 56 - 81 per 100,000 populations among men aged > 75 years and approximately 30 per 100,000 populations among women aged > 75 years [2]. Patients with malignant lymphoma can follow various clinical courses and prognoses, depending on their histo- logical subtype. Some of subtypes of malignant lym- phoma are now curable with the development of new therapeutic options. However, age has been recognized as one of the strongest adverse prognostic indicators in patients with malignant lymphoma [3-5]. One of reasons for this is that elderly patients sometimes receive insuf- ficient therapy due to factors such as chronic comorbid conditions, poor performance status (PS), and abnormal organ function. In practice, physicians can have diffi- cultly choosing the optimal management for very elderly patients, in terms of which medication and what dose. Although many studies have reported data for lymphoma patients aged 60 - 80 years, there is relatively little evi- dence for the management of very elderly patients. We have therefore analyzed the relationships between clini- cal characteristics, comorbidities, treatment and outcome in patients with malignant lymphoma aged > 75 years. 2. Patients and Methods 2.1. Patients, Clinical Assessment and Treatment From January 1998 to March 2007, 435 patients with malignant lymphoma, diagnosed according to REAL  Clinical Presentation and Outcome in Patients of over 75 Years Old with Malignant Lymphoma247 classification [6]/the World Health Organization (WHO) classification [7], were followed in our institution. For this study, we conducted a retrospective review of the results from 98 patients (22.5%) aged > 75 years. Of these, 97 patients were candidates for survival analysis, and one patient had no available clinical data except for pathological findings. Clinical variables were age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS, Ann Arbor stage, number of extra nodal involved sites, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), international prognostic index (IPI) and comorbidity index (Charlson’s comor- bidity index [CCI] [8,9]) and the hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCTCI) [10]. Over the study period, the standard treatment at our institute was a pirarubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone (THP-COP) or THP-COP-like regimen with or without rituximab. The doses and schedules of THP-COP and rituximab according to age are shown in Table 1. Some patients with localized lymphoma re- ceived three cycles of THP-COP following involved field irradiation. Patients with advanced lymphoma were planned to receive at least six cycles of THP-COP. For patients with poor PS, physicians modified the dose ac- cording to their own judgment. The cycle duration was also modified at the physician’s discretion (≥21 days, depending on the grade of myelosuppression and adverse events). For some patients, in the absence of institutional policy, the choice of treatment (including palliative care) was based on the referring physician’s judgment and the patient’s wishes. General condition and coexisting organ dysfunction were the major criteria that affected treat- ment decisions. The patients and their outcomes have been followed closely, and where possible, the cause of death has been identified. 2.2. Relative Dose Intensity We analyzed the agent-specific relative dose intensity (RDI) [11] as the ratio of the dose actually delivered to the planned dose intensity in 64 malignant lymphoma patients who received a THP-COP or THP-COP-like regimen ± rituximab. The average RDI (aRDI) was cal- culated by averaging the delivered RDI of cyclophos phamide and pirarubicin for THP-COP ± rituximab. We analyzed overall survival comparisons of three groups Table 1. Chemotherapy regimen reference planned doses and schedule. ≤79 years 80 years Pirarubicin 40 mg/m2 (Day 3) 30 mg/m2 (Day 3) Cyclophosphamide 650 mg/m2 (Day 3) 400 mg/m2 (Day 3) Vincristine 1 mg/m2 (Day 3) 1 mg/m2 (Day 3) Prednisolone 40 mg/m2 (Days 3 - 7) 30 mg/m2 (Days 3 - 7) Rituximab 375 mgmg/m2 (Day 1) 375 mgmg/m2 (Day 1) that were categorized as ≥0.85 of RDI, ≤0.84 of RDI and incomplete chemotherapy for 31 advanced aggressive lymphoma patients. This cutoff was based on an analysis by Lyman et al. [12]. 2.3. Statistical Analysis The relationships between age and sex, PS, stage, IPI, therapy and comorbidity index was analyzed using the student’s t-test. Overall survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death according to the method of Kaplan and Meier [13]. Comparisons were made using a log-rank test with the following variables: age, sex, PS, stage, serum LDH level, immunophenotype of lymphoma, IPI and comorbidity index (by HCTCI and CCI) in all patients. We also analyzed overall survival comparisons of the above variables, except for comorbidity index, along with use or not of rituximab in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. 3. Results 3.1. Patient Characteristics and Relationship between Age and Clinical Variables The clinical characteristics of the patients are summa- rized in Table 2. The median follow-up period was 659 days. The mean age was 79.9 years (range 75 - 89 years). Poor PS (2-4), advanced stage (III or IV), raised LDH and high-intermediate and high risk IPI were seen in 41%, 56%, 55%, and 53% of patients, respectively. According to the WHO classification, 68 of 98 patients (69.4%) presented a B-cell lymphoma (Table 3). The most fre- quent histological subtype was diffuse large B-cell lym- phoma (n = 48). It is noteworthy that the proportion of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) was relatively high (n = 12), because the Saga prefecture area of Japan, where the study was carried out, is an endemic area of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-I). When patients were divided into three groups (stan- dard chemotherapy, radiation alone, and palliative ther- apy), there was a trend towards a relationship between age and palliative care versus chemotherapy (p = 0.056), but no relationship between age and other combinations of treatment. This suggests that physicians tended not to select aggressive chemotherapy for older patients. There was no significant correlation between age and other clinical variables (sex, subtype, PS, stage and IPI). 3.2. Survival Analysis The 5-year overall survival rate was 32.2% among 97 malignant lymphoma patients (Figure 1(a)). Median survival time was 378 days among 62 deceased patients. The main reasons for death were malignant lymphoma (n = 27, 43.5%), infection ( = 4, 6.5%) and other ma- n Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM  Clinical Presentation and Outcome in Patients of over 75 Years Old with Malignant Lymphoma Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM 248 Table 2. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in all lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. All patients (n = 97) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n = 48) n 5-year OS% p n 5-year OS% p Age NS <0.05 ≤7943 26.3 26 20.9 ≥8054 42.1 22 57.3 Sex <0.05 0.088 Male54 23.1 20 N.R. Female43 44.2 28 47.5 PS 0.005 NS 0-157 42.3 28 43.1 2-440 18.1 20 30.7 LDH <0.03 0.01 ≤normal44 41.0 19 55.6 >normal53 26.4 29 26.2 Stage <0.005 <0.0001 I, II43 45.3 26 55.6 III, IV54 21.9 22 N.R. Immunologic phenotype <0.0001 B-cell68 41.9 NK/T cell26 5.6 Other3 N.R IPI <0.001 <0.005 Low 22 45.0 13 60.4 Low-INT24 50.7 12 52.5 High-INT18 18.1 7 N.R. High33 18.5 16 N.R. Rituximab <0.05 yes 23 40.9 no 16 16.7 N.R. Observation time does not reach 5 years. Table 3. Subtypes of lymphoma. All patients (n = 98) subtype B-cell 68 FCL 5 MCL 2 MALT 4 DLBCL 48 Burkitt’s like 1 IVL 2 Other B-cell 6 NK/T cell 27 PTCL,NOS 7 AITL 3 ATL(indolent) 2 ATL (aggressive) 10 Nasal NK/T 2 ALCL 1 Other T 2 HD 1 Unclassified 2 Abbrevation; FCL; follicular lymphoma, MCL; mantle cell lymphoma, MALT; extranodal mucosal associated tissue type lymphoma, DLBCL; diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, IVL; intravascular lymphoma, PTCL, peri- pheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, AITL; angioimmu- noblastic T-cell lymphoma, ATL; adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, ALCL; anaplastic large cell lymphoma, HD; Hodgkin’s lymphoma. lignant disease (n = 3, 4.8%). The overall survival rate was significantly higher in the following groups: female, PS 0-1, stage I/II, normal serum LDH level, B-cell sub- type, and low/low-intermediate IPI, but there was no significance difference between those aged ≤ 79 vs. ≥ 80 years (Table 2). Among DLBCL patients, 5-year overall survival rate was 36.6% (Figure 1(b)). The overall survival rate was significantly higher in the following groups: female, stage I/II, normal serum LDH level, low/low-intermediate IPI, and age ≥ 80 vs. ≤ 79 years (Table 2). Thirty-nine patients with DLBCL received a THP- COP or THP-COP-like regimen, and 23 of these also received rituximab. The 5-year overall survival rate was significantly higher among patients who received che- motherapy in combination with rituximab than among those who did not receive rituximab (40.9% vs 16.7%, p < 0.05). 3.3. Relationship between Comorbidity and Survival Major comorbidities according to HCTCI and CCI are summarized in Table 4. Seventy-three patients (75%) had more than one comorbidity. A previous history of cardio- vascular diseases (including arrhythmia, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, cardiac failure, pacemaker, and valve disease) was found in 28 patients. Diabetes  Clinical Presentation and Outcome in Patients of over 75 Years Old with Malignant Lymphoma249 Table 4. Major comorbidity-defining organ or disease categories according to HCTCI and CCI. n 5-years OS(%) p HCTCI score CCI score Yes 22 12.7 Arrythmia No 75 38.2 n.s. 1 0 Yes 14 27.9 Cardiac No 83 33.4 n.s 1 1 Yes 0 - Inflammatory bowel disease No 97 32.2 n.s. 1 0 Yes 10 25.4 Diabetes No 87 32.4 N.E 1 1 Yes 19 31.5 Cerebrovascular disease No 78 35.4 n.s. 1 1 Yes 2 N.R. Psychiatric disturbance No 95 32.6 n.s. 1 Not included Yes 0 - Obesity No 97 32.2 n.s. 1 Not included Yes 6 0.0 Infection No 91 34.9 0.001 1 Not included Yes 8 0.0 Mild pulmonary No 89 43.0 n.s. Not included 1 Yes 3 0.0 Rheumatologic No 94 33.8 n.s. 2 1 Yes 6 16.7 Peptic ulcer No 91 33.2 0.07 2 1 Yes 0 - Moderate/severe renal No 97 32.2 n.s. 2 2 Yes 5 20.0 Moderate pulmonary No 92 32.8 n.s. 2 2 Yes 22 32.9 Prior solid tumor No 75 32.1 n.s. 3 2 Yes 3 50.0 Heart valve disease No 94 31.3 n.s. 3 0 Yes 1 N.R. Severe pulmonary No 96 31.8 n.s. 3 1 Yes 5 N.R. Moderate/severe hepatic No 92 33.4 <0.01 3 3 CCI, Charlson’s comorbidity index; HCTCI, hematopoietic cell transplantation morbidity index; N.E., Not evaluated; N.R., Not reached; n.s., not significant. co (a) (b) Figure 1. Overall survival in (a) all malignant lymphoma patients and (b) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM  Clinical Presentation and Outcome in Patients of over 75 Years Old with Malignant Lymphoma 250 was found in 10 and cerebrovascular disease was found in 19 patients. Prior or simultaneous malignnant disease was found in 22 patients. Patients were separated into three categories: 0, 1, 2, and ≥3 according to the original description of the HCTCI and CCI scoring systems. Overall survival was significantly poorer among patients with infection and moderate/severe liver dysfunction (Table 4), but the HCTCI and CCI score did not impact overall survival. (Figure 2) 3.4. Relative Dose Intensity in Elderly Malignant Lymphoma In this study, 64 or 97 patients received a THP-COP or THP-COP-like regimen. We analyzed aRDI for these patients. Status, subtype, and outcome profiles in these patients are shown in Figure 3. Of 31 patients with ad- vanced aggressive lymphoma, 21 had B-cell lymphomas and 10 had T-cell lymphomas. Sixteen patients accom- plished six cycles of THP-COP. However, only three patients (9.7%) with these advanced aggressive lym- phomas had an aRDI for cyclophospamide and pirarubi- cin ≥ 0.85. Fifteen patients stopped THP-COP, due to exacerbation of lymphoma (n = 9), adverse effects (n = 2), changing hospital (n = 3), and patient’s decision (n = 1). The proportion of patients receiving ≥ 0.85 of the planned dose intensity during five cycles of treatment decreased gradually across cycles of chemotherapy (Figure 4). Furthermore, the proportions of patients with RDI ≥ 0.85 in the first cycle of chemotherapy were < 50% in all patient who received THP-COP and in the (a) (b) Figure 2. The overall survival by (a) hematopoietic cell transplantation specific comorbidity index (HCTCI) and (b) Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) in all malignant lymphoma patients. Figure 3. Profile of lymphoma patients who received a THP-COP or THP-COP-like regimen. Subtypes of aggressive lym- phoma are DLBCL (n = 20), Burkitt-like (n = 1), AITL (n = 2), PTCL-u (n = 1) and ATL (n = 7). Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM  Clinical Presentation and Outcome in Patients of over 75 Years Old with Malignant Lymphoma251 Figure 4. Proportions of patients receiving relative dose intensity ≥ 85% and ≤ 84% during the first five cycles of chemotherapy. 31 patients with advanced aggressive lymphoma. The prognosis of patients with advanced aggressive lym- phoma who completed their THP-COP regimen was better than those who did not complete the regimen. However, overall survival was not significant different between those with aRDI ≥ 0.85 or ≤ 0.84. 4. Discussion The population in Saga prefecture where our hospital is located is approximate 852,000 in the 2009 national population census. Of these, 12.9% were >75 years old, which is higher than average in Japan. However, this is likely to be the case in the rest of Japan in near future. The consultation rate of elderly hematological patients at our hospital is high, and the number of patients with lymphoma was 2 to 3-fold higher in 2005-2007 than it was in 1998-2000. Numerous studies about clinical presentation for very elderly patients with malignant lymphoma have been reported from western countries [14-19], but there is limited practical information in Japan. It is therefore very important to analyze the current picture of lymphoma patients in Japan and to be aware of this issue, in order to be prepared for the aging Japanese society. We analyzed a relationship between age and clinical index, including PS, stage, comorbidity, histology, and initial therapy. There were no significant differences between age and clinical indexes, except for initial ther- apy. Some of patients, their family and physician chose palliative or no chemotherapy rather than aggressive chemotherapy for older patients on ground of patients’ will and lack confidence in receiving chemotherapy. They tended to select the therapy based on age, even if PS and comorbidities were not poor. Elderly patients could not always understand the benefits and detriments of therapy, despite adequate information, because most of them have a reduced emotional tolerance about their disease diagnosis and its treatment. Therefore, a pa- tient’s family often decided the best therapy for the pa- tient. Also, some of the patients were conscious of their age, and some refused chemotherapy on the basis of their advanced age. However, there was no significant difference between those aged ≤ 79 years compared with those aged ≥ 80 years group in our study. Furthermore, the prognosis of the elderly patients was actually quite reasonable. These factors may make the chance of cure less likely, and shorten the survival time for patients with curable lymphoma. Aging is not a reason not to choose aggressive chemotherapy, as has been showed in other studies [17,20]. Comorbidity index (using HCTCI and CCI) is an im- portant prognostic factor in elderly acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) patients and stem cell transplantation [9, 21-23]. However, there are few data on whether comor- bidity index is a useful prognostic factor in elderly lym- phoma patients. We found that both HCTCI and CCI were not significantly prognostic, except for infection and severe liver disease. This finding suggests that some of subtypes of lymphoma are curable, if elderly patients receive reduced-intensity chemotherapy. Comorbidity index is, therefore, a useful predictive prognostic marker in diseases that require strong chemotherapy, such as elderly AML and stem cell transplantation, but not for elderly malignant lymphoma. Once a complete remis- sion has been achieved, the disease-free survival can be similar to that of a younger patient, even if the first-line chemotherapy regimen was less aggressive [24]. Other studies have also reported that CCI is not associated with survival in retrospective analyses [14,18]. In contrast, PS was one of the most important vari- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM  Clinical Presentation and Outcome in Patients of over 75 Years Old with Malignant Lymphoma 252 ables predictive of survival. PS reflects tolerance of pa- tients, organ function, and disease progression, and it is the most important factor for judging whether patients can receive aggressive chemotherapy. Comorbidity index may be prognostic factor, as with PS, in some lymphoma subtypes, but comorbidity index needs to be evaluated in prospective trials of patients with each subtype to con- firm this. Our data suggest that lymphoma phenotype is a strong prognostic factor. Patients with T/NK cell lymphoma had a very inferior prognosis compared with patients with B-cell lymphoma. Our geographic area is endemic for HTLV-I, and elderly ATL is frequently diagnosed. Aggressive ATL generally has a poor prognosis and it is difficult to prolong the survival time even with intensive chemotherapy [25]. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is now considered a promising treatment for young patients with ATL [26,27], but is not indicated in elderly patients due to higher toxicities and poor completion rates. Currently, chemotherapy for elderly ATL patients should focus on safety above efficacy, because this disease is not curable. Some reports have shown that maintaining a high RDI of doxorubicin provides a survival benefit [11,12,28]. Lyman et al. showed that a subset of patients aged > 60 years who were treated with doxorubicin at dose intensi- ties > 10 mg/m2/week had a 5-year survival rate similar to that seen in younger patients [12]. However, in pa- tients aged > 75 years old, it is difficult to maintain dose intensity because most elderly patients have some co- morbid disease and poor PS. Indeed, only 10% of the patients with aggressive lymphoma in our study who received a THP-COP or THP-COP-like regimen man- aged to maintain RDI > 0.85. This was partly due to a prolonged recovery of bone marrow after chemotherapy, but also due to insufficient dosing. This is particularly problematic for elderly patients due to problems getting to the hospital and the absence of a care assistant at home. However, patients treated at RDI ≤ 0.84 in the > 75-year old group did not have a significantly poorer outcome. This may be due to the small number of pa- tients in this study. However, to the best of our knowl- edge, this is the first study to focus on very elderly lymphoma patients. Our findings suggest that it is pref- erable to carry on treatment at a lower dose, thereby minimizing adverse events, rather than strictly adhering to high dose intensity. However, a large-scale study is recommended in order to validate this proposal. In conclusion, age is not always an adverse prognostic factor, if the patient has good PS, favorable histology, and lower-risk IPI. As is the case in younger patients, the most important prognostic factors were lymphoma subtype, PS, and IPI. Comorbidity index, however, did not have an impact on survival. Maintaining a high RDI during chemotherapy is recommended, but in practice, this can be difficult. Modification of the applied dose and the duration of chemotherapy may be required to improve survival in very elderly patients. REFERENCES [1] “White Paper on the Aging Society in 2010,” in Japanese, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan, 2010. [2] T. Marugame, K. Kamo, K. Katanoda, W. Ajiki and T. Sobue, “Cancer Incidence and Incidence Rates in Japan in 2000: Estimates Based on Data from 11 Population-Based Cancer Registries,” Japanese Journal of Clinical Onco- logy, Vol. 36, No. 10, 2006, pp. 668-675. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyl084 [3] The International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project, “A Predictive Model for Aggressive Non- Hodgkin’s Lymphoma,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 329, No. 14, 1993, pp. 987-994. doi:10.1056/NEJM199309303291402 [4] P. Solal-Céligny, P. Roy, P. Colombat, J. White, J. O. Armitage, R. Arranz-Saez, et al., “Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index,” Blood, Vol. 104, No. 5, 2004, pp. 1258-1265. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434 [5] J. M. Vose, J. O. Armitage, D. D. Weisenburger, P. J. Bierman, S. Sorensen, M. Hutchins, et al., “The Importance of Age in Survival of Patients Treated with Chemotherapy for Aggressive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 6, No. 12, 1988, pp. 1838-1844. [6] N. L. Harris, E. S. Jaffe, H. Stein, P. M. Banks, J. K. Chan, M. L. Cleary, et al., “A Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms: A Proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group,” Blood, Vol. 84, No. 5, 1994, pp. 1361-1392. [7] E. S. Jaffe, N. L. Harris, H. Stein and J. W. Vardiman, Eds., “WHO Classification of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues,” IARC Press, Lyon, 2001. [8] M. E. Charlson, P. Pompei, K. L. Ales and C. R. MacKenzie, “A New Method of Classifying Prognostic Comorbidity in Longitudinal Studies: Development and Validation,” Journal of Chronic Diseases, Vol. 40, No. 5, 1987, pp. 373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [9] A. Etienne, B. Esterni, A. Charbonnier, M. J. Mozzi- conacci, C. Arnoulet, D. Coso, et al., “Comorbidity is an Independent Predictor of Complete Remission in Elderly Patients Receiving Induction Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia,” Cancer, Vol. 109, No. 7, 2007, pp. 1376-1383. doi:10.1002/cncr.22537 [10] M. L. Sorror, M. B. Maris, R. Storb, F. Baron, B. M. Sandmaier, D. G. Maloney et al., “Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT)-Specific Comorbidity Index: A New Tool for Risk Assessment before Allogeneic HCT,” Blood, Vol. 106, No. 8, 2005, pp. 2912-2919. [11] R. Epelbaum, N. Haim, M. Ben-Shahar, Y. Ron and Y. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM  Clinical Presentation and Outcome in Patients of over 75 Years Old with Malignant Lymphoma Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM 253 Cohen, “Dose-Intensity Analysis for CHOP Chemotherapy in Diffuse Aggressive Large Cell Lymphoma,” Israel Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 24, No. 9-10, 1988, pp. 533-538. [12] G. H. Lyman, D. C. Dale, J. Friedberg, J. Crawford and R. I. Fisher, “Incidence and Predictors of Low Chemotherapy Dose-Intensity in Aggressive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Nationwide Study,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 22, No. 21, 2004, pp. 4302-4311. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.03.213 [13] E. L. Kaplan and P. Meier, “Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 53, No, 282, 1958, pp. 457- 481. doi:10.2307/2281868 [14] C. Thieblemont, A. Grossoeuvre, R. Houot, F. Broussais- Guillaumont, G. Salles, C. Traullé, et al., “Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in Very Elderly Patients over 80 Years. A Descriptive Analysis of Clinical Presentation and Outcome,” Annals of Onc ology , Vol. 19, No. 7, 2008, pp. 774-779. [15] M. Mori, K. Kitamura, M. Masuda, T. Hotta, T. Miyazaki, A. B. Miura, et al., “Long-Term Results of a Multicenter Ran-Domized, Comparative Trial of Modified CHOP versus THP-COP versus THP-COPE Regimens in Elderly Pa Tients with Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma,” International Journal of Hematology, Vol. 81, No. 3, 2005, pp. 246-254. doi:10.1532/IJH97.03147 [16] M. Pfreundschuh, J. Schubert, M. Ziepert, R. Schmits, M. Mohren, E. Lengfelder, et al., “Six versus Eight Cycles of Bi-Weekly CHOP-14 with or without Rituximab in Elderly Patients with Aggressive CD20+ B-Cell Lymphomas: A Randomised Controlled Trial (RICOVER-60),” The Lancet Oncology, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2008, pp. 105-116. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70002-0 [17] M. Pfreundschuh, “How I Treat Elderly Patients with Dif- Fuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma,” Blood, Vol. 116, No. 24, 2010, pp. 5103-5110. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-07-259333 [18] S. T. Lim, S. W. Hee, R. Quek and M. Tao, “Performance Status Is the Single Most Important Prognostic Factor in Lymphoma Patients Aged Greater than 75 Overriding Other Prognostic Factors Such as Histology,” Leuk Lymphoma, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2008, pp. 149-151. doi:10.1080/10428190701647895 [19] J. O. Armitage, “Is Lymphoma Occurring in the Elderly the Same Disease?” Leuk Lymphoma, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2008, pp. 14-16. doi:10.1080/10428190701742522 [20] A. S. Huerta, J. Gómez-Codina, M. Pastor, R. Gironés, J. A. Pérez-Fidalgo and R. Díaz, “Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in Older People: Age Is Not Always an Adverse Prog- nostic Factor,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Vol. 50, No. 11, 2002, pp. 1911-1912. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50529.x [21] F. J. Giles, G. Borthakur, F. Ravandi, S. Faderl, S. Verstovsek, D. Thomas, et al., “The Haematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index Score Is Predictive of Early Death and Survival in Patients over 60 Years of Age Receiving Induction Therapy for Acute Myeloid Leukaemia,” British Journal of Haematolog, Vol. 136, No. 4, 2007, pp. 624-627. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06476.x [22] N. Vey, D. Coso, V. J. Bardou, A. M. Stoppa, A. C. Braud, R. Bouabdallah, et al., “The Benefit of Induction Chemotherapy in Patients Age,” Cancer, Vol. 101, No. 2, 2004, pp. 325-331. doi:10.1002/cncr.20353 [23] M. L. Sorror, S. Giralt, B. M. Sandmaier, M. D. Lima, M. Shahjahan, D. G. Maloney, et al., “Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Specific Comorbidity Index as an Outcome Predictor for Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia in First Remission: Combined FHCRC and MDACC Experiences,” Blood, Vol. 110, No. 13, 2007, pp. 4606-4613. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-06-096966 [24] Y. Bastion, J. Y. Blay, M. Divine, P. Brice, D. Borde- ssoule, C. Sebban, M. Blanc, et al., “Elderly Patients with Aggressive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Disease Presen- tation, Response to Treatment, and Survival—A Grou- ped’ Etude Des Lymphomes De L’adulte Study on 453 Patients Older than 69 Years,” Journal of Clinical Onco- logy, Vol. 15, No. 8, 1997, pp. 2945-2953. [25] K. Tsukasaki, A. Utsunomiya, H. Fukuda, T. Shibata, T. Fukushima, Y. Takatsuka, et al., “Japan Clinical Oncol- ogy Group Study JCOG9801. VCAP-AMP-VECP Com- Pared with Biweekly CHOP for Adult T-Cell Leuke- Mia-Lymphoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG9801,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 25, No. 34, 2007, pp. 5458-5464. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9958 [26] T. Fukushima, Y. Miyazaki, S. Honda, F. Kawano, Y. Moriuchi, M. Masuda, et al., “Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Provides Sustained Long-Term Survival for Patients with Adult T-Cell Leukemia/Lym- phoma,” Leukemia, Vol. 19, No. 5, 2005, pp. 829-834. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2403682 [27] S. Shiratori, A. Yasumoto, J. Tanaka, A. Shigematsu, S. Yamamoto, M. Nishio, et al., “A Retrospective Analysis of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Adult T Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma (ATL): Clinical Impact of Graft-Versus-Leukemia/Lymphoma Effect,” Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Vol. 14, No. 7, 2008, pp. 817-823. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.04.014 [28] L. W. Kwak, J. Halpern, R. A. Olshen and S. J. Horning, “Prognostic Significance of Actual dose Intensity in Diffuse Large-Cell Lymphoma: Results of a Treestructured Survival Analysis,” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 8, No. 6, 1990, pp. 963-977

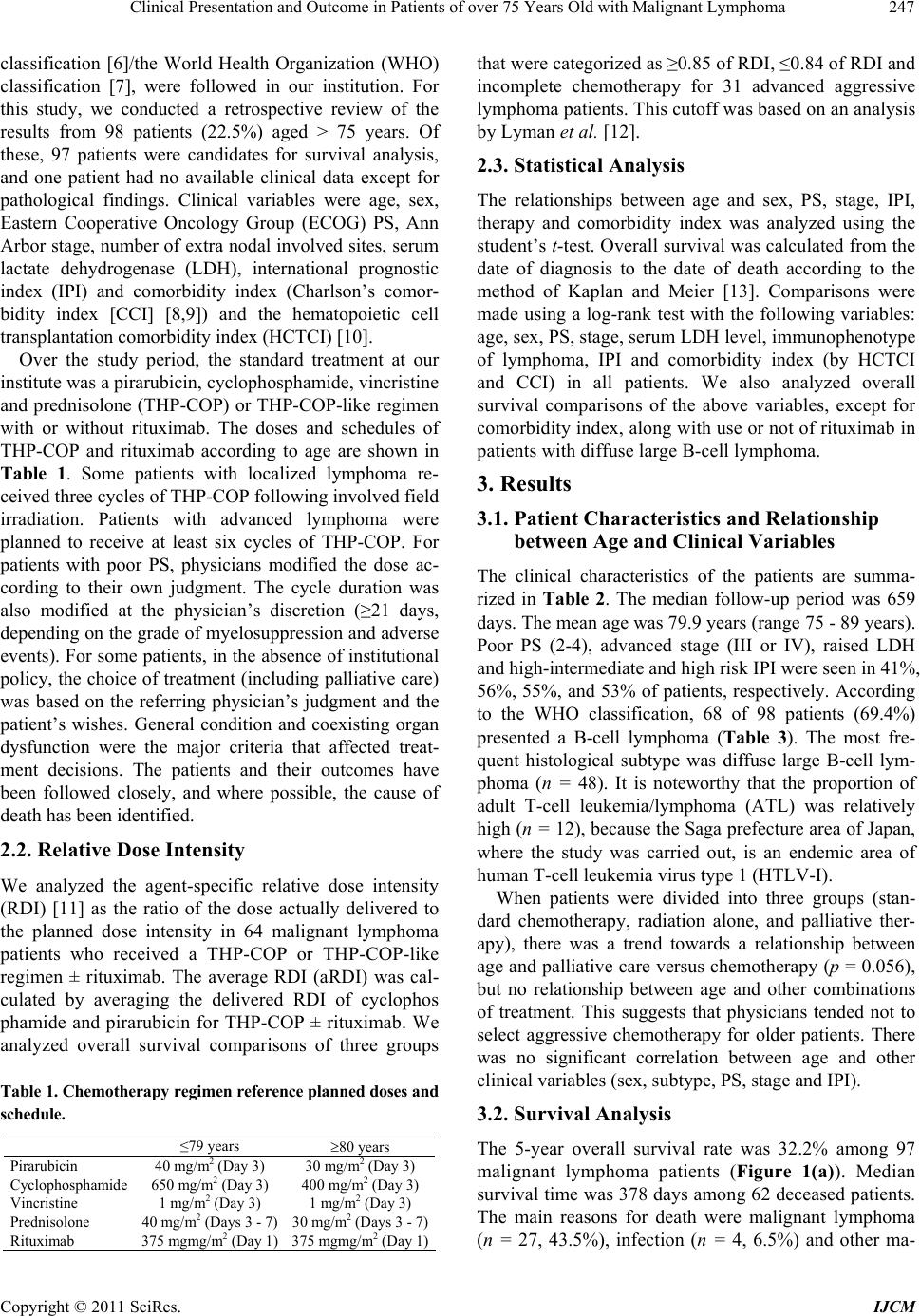

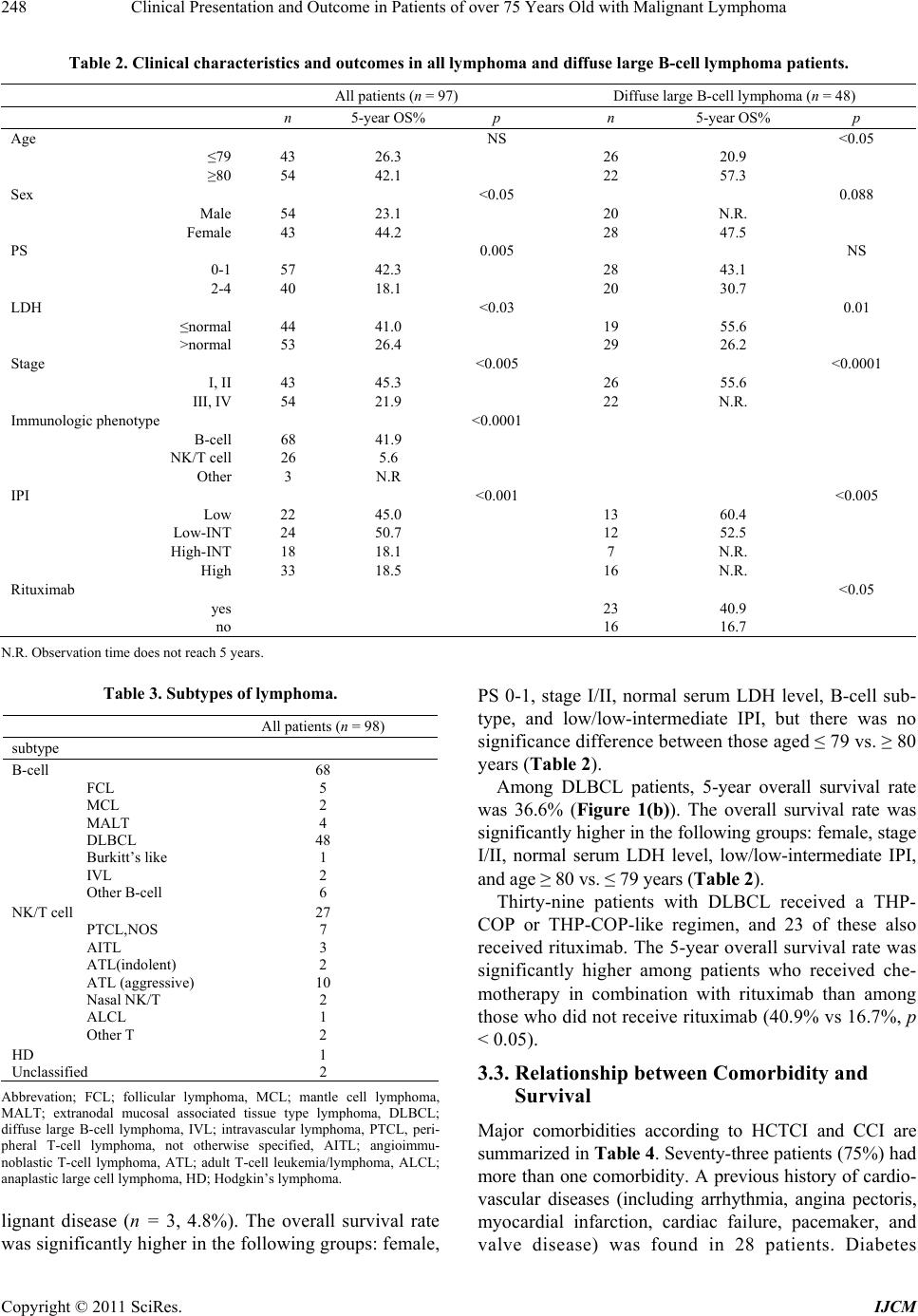

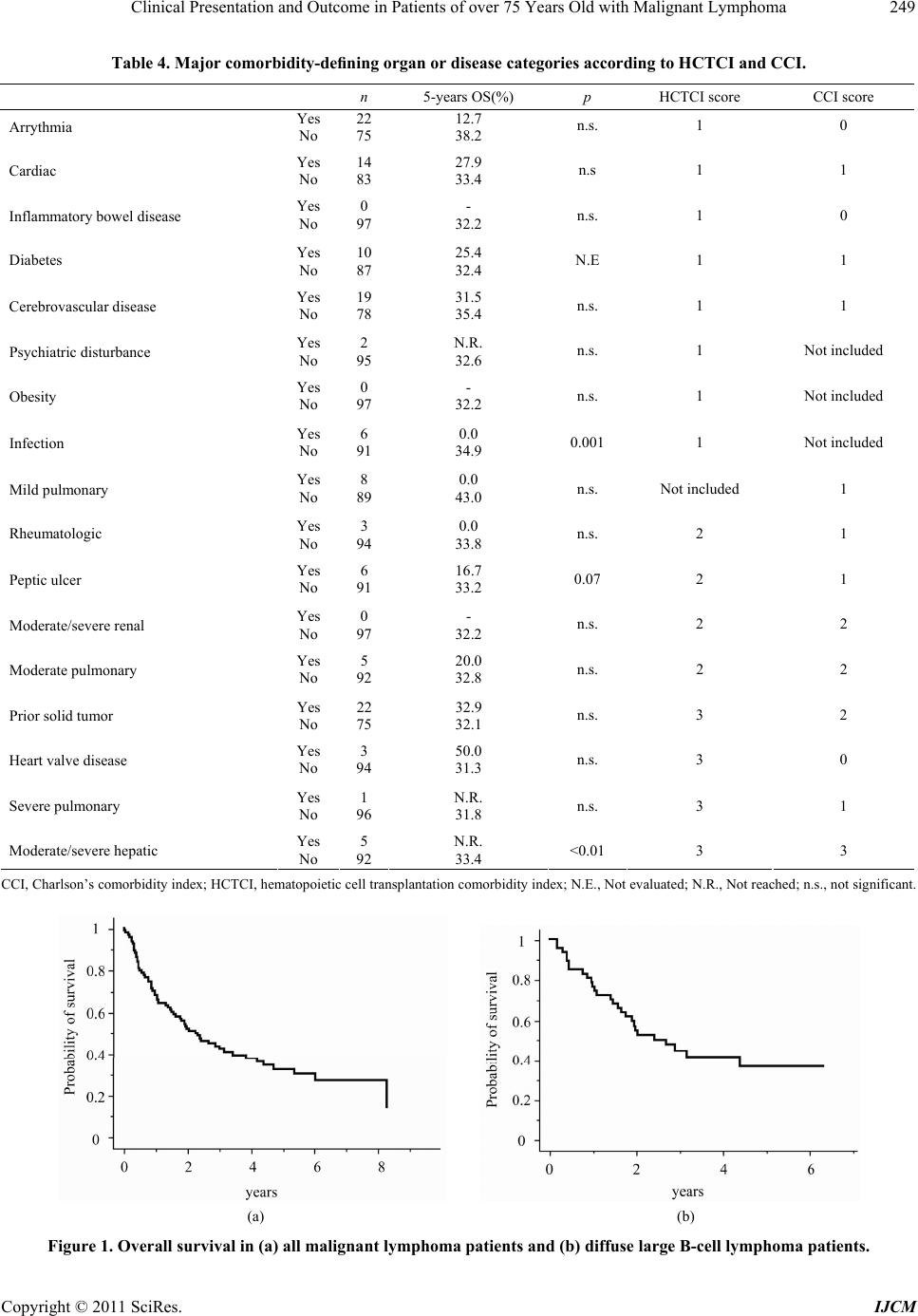

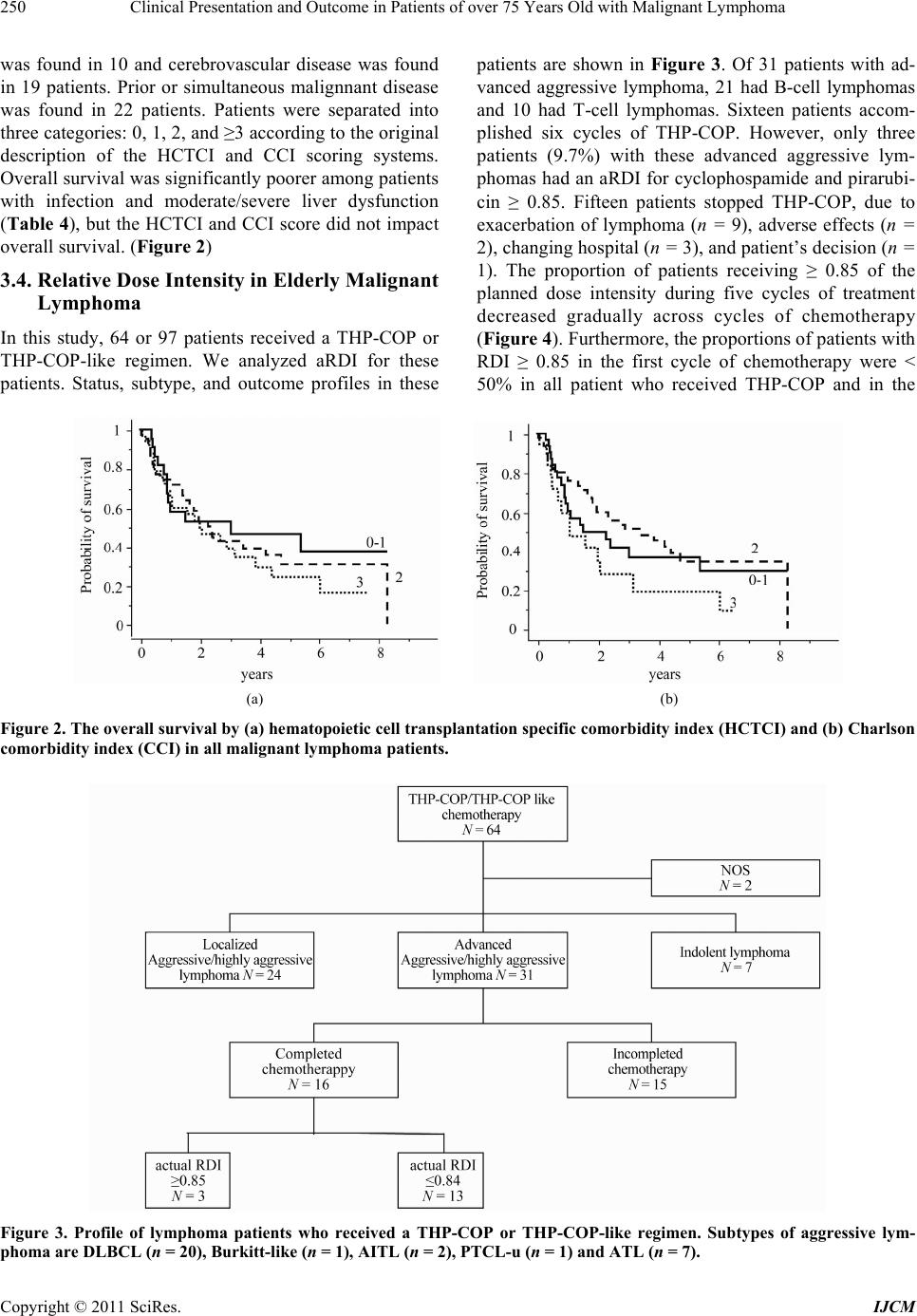

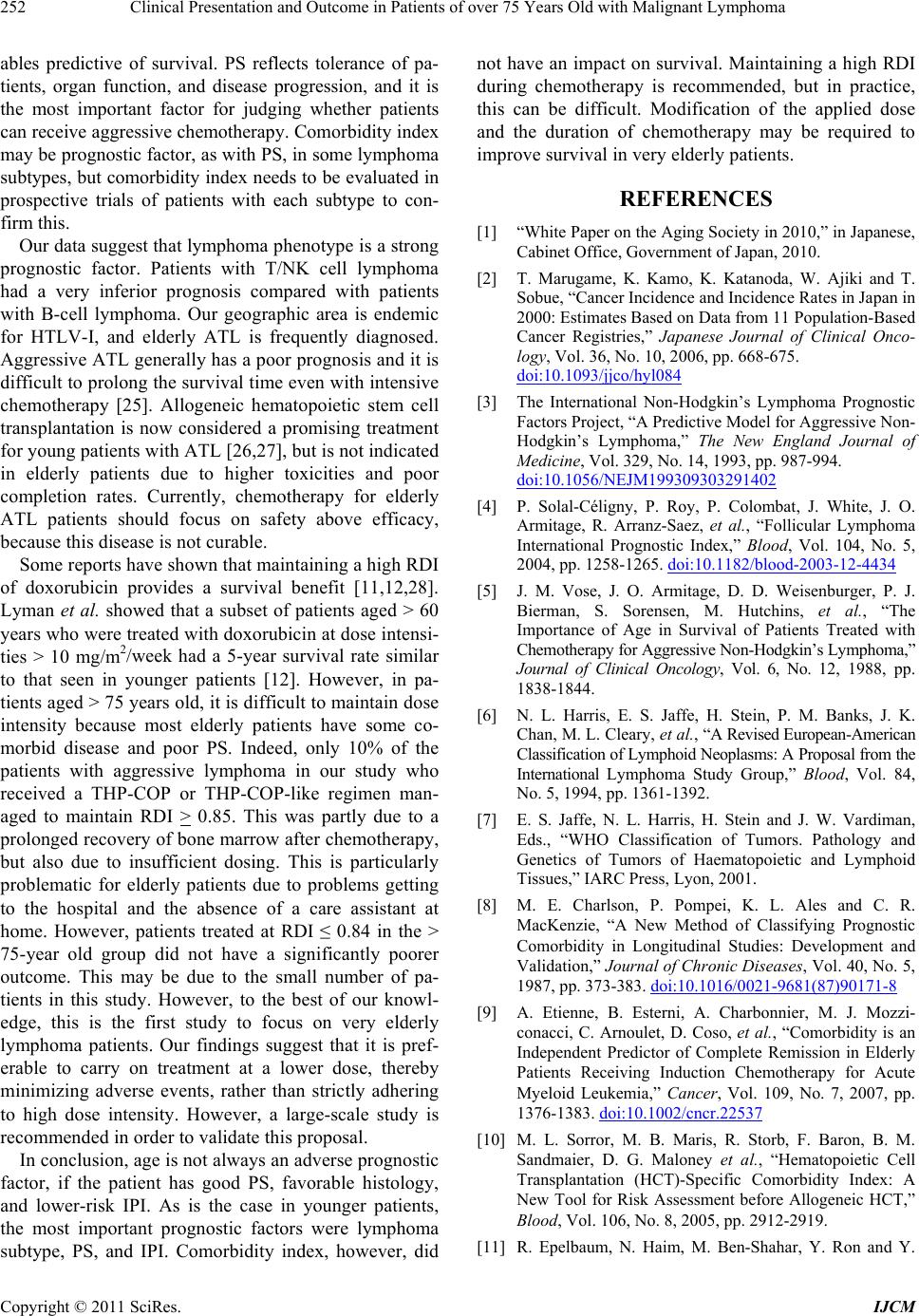

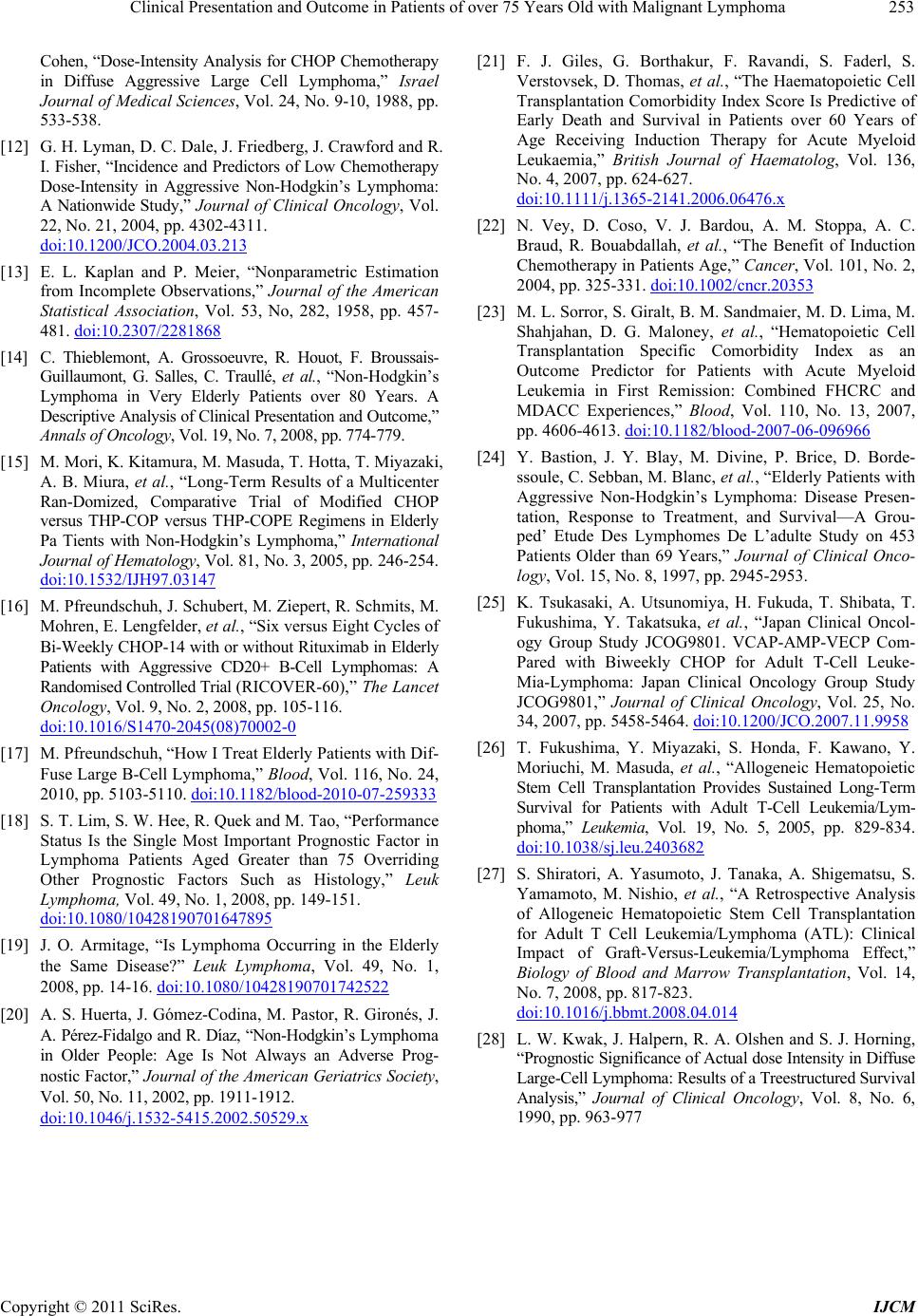

|