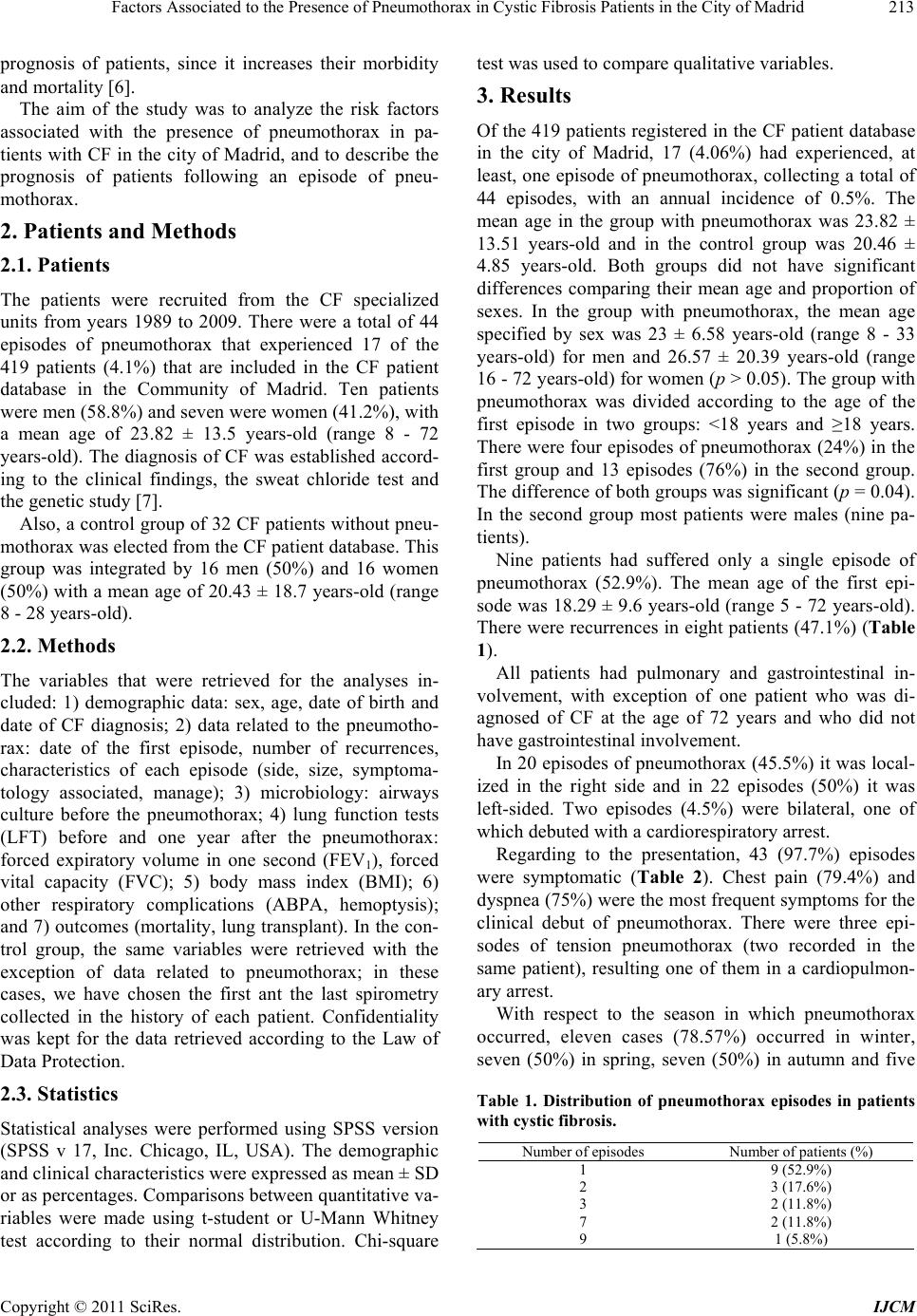

International Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2011, 2, 212-217 doi:10.4236/ijcm.2011.23035 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ijcm) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM Factors Associated to the Presence of Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis Patients in the City of Madrid Prados Concepción1*, Carpio Carlos2, Martínez María Teresa3, Máiz Luis4, Girón Rosa5, Barrio Isabel6, Salcedo Antonio7, García Hernández Gloria8, Gómez Carrera Luis9, Álvarez-Sala Rodolfo10, The Neumomadrid Cystic Fibrosis Work Group11 1Prados Sánchez, Concepción, Department of Pneumology, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 2Carpio Segura, Carlos Javier, Department of Pneumonology, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 3Martínez Martínez, María Teresa, Department of Pneu- monology, Doce de Octubre University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 4Máiz Carro, Luis, Department of Pneumonology, Ramón y Cajal University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 5Girón Moreno, Rosa, Department of Pneumonology, La Princesa University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 6Barrio de Agüero, María Isabel, Department of Pediatric Pneumonology, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 7Salcedo Posadas, Antonio, Department of Pediatric Pneumonology, Gregorio Marañón University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 8García Hernández, Gloria, Department of Pediatric Pneumonology, Doce de Octubre University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 9Gómez Carrera, Luis, Department of Pneumonology, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 10Álvarez-Sala Walther, Rodolfo, Department of Pneumonology, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; 11Carmen Antelo Landeira, Carmen Martínez Carrasco, Juan José Cabanillas Martin, Jose Ramón Villa Asensi, Madrid, Spain. Email: *conchaprados@gmail.com, carlinjavier@hotmail.com, lmaiz@hrc.insalud.es, med002861@nacom.es, gloriagh@eresmas.net, {mmartinezm.hdoc, asalcedop.hgugm, ralvarezw.hulp}@salud.madrid.org Received January 4th, 2011; revised March 16th, 2011; accepted April 1st, 2011. ABSTRACT Background: To identify risk factors associated with pneumothorax and to determine the prognosis of cystic fibrosis patients following an episode of pneumothorax in the city of Madrid. Methods: Records of 17 patients (10 males; age 24.4 ± 17.5 years) and 32 controls, and a total of 44 pneumothorax episodes were studied. We have analyzed the char- acteristics of the pneumothorax, the microbiology, the lung function tests (LFT) and the prognosis of patien ts. Two con- trols with cystic fibrosis and without pneumothorax matched for sex and age were selected. Results: Eight male and three female patients with pneumothorax were older than 18 years. The mean age of the first pneumothorax episode was 18 .3 years (±9.6). The group with pneumothorax had a mean body mass index of 19.2(±2.42 kg/m2) and in the con- trol group it was 26.5 (±1.98 kg/m2). Pseudomonas aeruginosa was present in fourteen patients (82%) with pneu- mothorax and in eleven patients (34.4%) in the control group (p = 0.002). Pneumothorax predominantly occurred in the coldest seasons. There was a significant drop in both forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) after the pneumothorax. In the same way, FEV1 and FVC were greater in the control group. Six pa- tients (35.4%) with pneumothorax and two patients in the control group have died (p < 0.05). Conclusions: Patients with pneumothorax are more likely to have P. aeruginosa colonization. LFT drop after an episode of pneumohorax. Patients with pneumothorax have worse LFT than patients without pneumothorax. Mortality is greater in patients with pneumothorax. Keywords: Cystic Fibrosis, Pleural Disease, Pneumoth orax 1. Introduction Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disease caused by the presence of mutations in a single gene on chromosome 7, which encodes the cystic fibrosis trans- membrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein [1]. CF originates different respiratory complications like pneumothorax, hemoptysis and allergic bronchopulmo- nary aspergillosis (ABPA) [2]. Pneumothorax is a fre- quent and life-threatening complication in patients with CF with an average annual incidence of 0.64% to 1% [3,4]. Pneumothorax has been related to the presence of increased transpulmonary air pressure difference and lung hyperinflation due to chronic inflammation of the airways [5]. This respiratory complication worsens the  Factors Associated to the Presence of Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis Patients in the City of Madrid 213 prognosis of patients, since it increases their morbidity and mortality [6]. The aim of the study was to analyze the risk factors associated with the presence of pneumothorax in pa- tients with CF in the city of Madrid, and to describe the prognosis of patients following an episode of pneu- mothorax. 2. Patients and Methods 2.1. Patients The patients were recruited from the CF specialized units from years 1989 to 2009. There were a total of 44 episodes of pneumothorax that experienced 17 of the 419 patients (4.1%) that are included in the CF patient database in the Community of Madrid. Ten patients were men (58.8%) and seven were women (41.2%), with a mean age of 23.82 ± 13.5 years-old (range 8 - 72 years-old). The diagnosis of CF was established accord- ing to the clinical findings, the sweat chloride test and the genetic study [7]. Also, a control group of 32 CF patients without pneu- mothorax was elected from the CF patient database. This group was integrated by 16 men (50%) and 16 women (50%) with a mean age of 20.43 ± 18.7 years-old (range 8 - 28 years-old). 2.2. Methods The variables that were retrieved for the analyses in- cluded: 1) demographic data: sex, age, date of birth and date of CF diagnosis; 2) data related to the pneumotho- rax: date of the first episode, number of recurrences, characteristics of each episode (side, size, symptoma- tology associated, manage); 3) microbiology: airways culture before the pneumothorax; 4) lung function tests (LFT) before and one year after the pneumothorax: forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC); 5) body mass index (BMI); 6) other respiratory complications (ABPA, hemoptysis); and 7) outcomes (mortality, lung transplant). In the con- trol group, the same variables were retrieved with the exception of data related to pneumothorax; in these cases, we have chosen the first ant the last spirometry collected in the history of each patient. Confidentiality was kept for the data retrieved according to the Law of Data Protection. 2.3. Statistics Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version (SPSS v 17, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). The demographic and clinical characteristics were expressed as mean ± SD or as percentages. Comparisons between quantitative va- riables were made using t-student or U-Mann Whitney test according to their normal distribution. Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative variables. 3. Results Of the 419 patients registered in the CF patient database in the city of Madrid, 17 (4.06%) had experienced, at least, one episode of pneumothorax, collecting a total of 44 episodes, with an annual incidence of 0.5%. The mean age in the group with pneumothorax was 23.82 ± 13.51 years-old and in the control group was 20.46 ± 4.85 years-old. Both groups did not have significant differences comparing their mean age and proportion of sexes. In the group with pneumothorax, the mean age specified by sex was 23 ± 6.58 years-old (range 8 - 33 years-old) for men and 26.57 ± 20.39 years-old (range 16 - 72 years-old) for women (p > 0.05). The group with pneumothorax was divided according to the age of the first episode in two groups: <18 years and ≥18 years. There were four episodes of pneumothorax (24%) in the first group and 13 episodes (76%) in the second group. The difference of both groups was significant (p = 0.04). In the second group most patients were males (nine pa- tients). Nine patients had suffered only a single episode of pneumothorax (52.9%). The mean age of the first epi- sode was 18.29 ± 9.6 years-old (range 5 - 72 years-old). There were recurrences in eight patients (47.1%) (Table 1). All patients had pulmonary and gastrointestinal in- volvement, with exception of one patient who was di- agnosed of CF at the age of 72 years and who did not have gastrointestinal involvement. In 20 episodes of pneumothorax (45.5%) it was local- ized in the right side and in 22 episodes (50%) it was left-sided. Two episodes (4.5%) were bilateral, one of which debuted with a cardiorespiratory arrest. Regarding to the presentation, 43 (97.7%) episodes were symptomatic (Table 2). Chest pain (79.4%) and dyspnea (75%) were the most frequent symptoms for the clinical debut of pneumothorax. There were three epi- sodes of tension pneumothorax (two recorded in the same patient), resulting one of them in a cardiopulmon- ary arrest. With respect to the season in which pneumothorax occurred, eleven cases (78.57%) occurred in winter, seven (50%) in spring, seven (50%) in autumn and five Table 1. Distribution of pneumothorax episodes in patients with cystic fibrosis. Number of episodes Number of patients (%) 1 9 (52.9%) 2 3 (17.6%) 3 2 (11.8%) 7 2 (11.8%) 9 1 (5.8%) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM  Factors Associated to the Presence of Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis Patients in the City of Madrid 214 Table 2. Symptoms of patients with pneumothorax. Symptom Number of episodes (%) Thoracic pain 35 (79.5%) Dyspnea 33 (75%) Hemoptysis 1 (2.3%) Cyanosis 1 (2.3%) Cardiorrespiratory arrest 1 (2.3%) Asymptomatic 1 (2.3%) Unknown 6 (13.8%) (35.71%) in summer. The number of episodes occurred in summer was less than in the other seasons (p < 0.05). In the same way, it was observed a non-significant dif- ference between the number of episodes in spring or autumn comparing to them in winter, (p = 0.098). Also, the total number of pneumothorax episodes occurred in the most cold seasons or with greater climate variability (winter, spring and autumn), was higher than the number of episodes in summertime (p < 0.05). Concerning microbiological cultures in the group with pneumothorax, Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonized the airways of 14 patients (82.4%). Other pathogens isolated were Staphylococcus aureus in three cases (17.6%), Haemophilus influenzae in two cases (11.8%), and both Klebsiella ozonae and Burkholderia cepacea in one case (5.8%) each one (Table 3). We found a significant dif- ference comparing colonization by P. aeruginosa in the group with pneumothorax with respect to the control group (p = 0.002). The nutritional status was established based upon the BMI. The group with pneumothorax had a mean BMI of 19.2 ± 2.42 kg/m2; and in the control group it was 26.5 ± 1.98 kg/m2. Significant differences were found between both groups (p = 0.01). With regard to the LFT, FVC and FEV1 prior to the episode of pneumothorax were 62.5% ± 17.8% (range 45% - 119%) and 43.4% ± 13.5% (range 20% - 83%), respectively; and one year after the event, they were 45.2% ± 18.8% (range 22% - 88%) and 32.5% ± 15.4% (range 18% - 71%), respectively. The difference in the LFT before and after pneumothorax was significant in both parameters (p = 0.008) (Figure 1). For the control group, we analyzed the first and the last LFT we had in the CF patient database. The initial FVC and FEV1 were Table 3. Culture of the airway of CF patients with and without pneumothorax. Sputum culture Pneumothorax (%) n = 17 Control (%) n = 32 P. aeruginosa* 14 (82.4%) 11 (34.2%) S. aureus 3 (17.6%) 13 (44.0%) H. influenzae 2 (11.8%) 5 (15.6%) K. ozonae 1 (5.9%) 1 (3.1%) B. cepacea 1 (5.9%) 1 (3.1%) *p < 0.01 Figure 1. Lung functional tests in pneumothorax and con- trol group be fore and o ne year after pneumothor ax espisode. FEV1 pre = forced expiratory volume in one second before pneumothorax; FEV1 post = forced expiratory volume in one second after pneumothorax; FVC pre= forced vital capacity before pneumothorax; FVC post = forced vital capacity after pneumothorax. *p < 0.05. 84.8% ± 18.5% (range 47% - 119%) and 82.53% ± 22.8% (range 25% - 119%) respectively; and the last record for both parameters were 87.5% ± 21.51% (range 40% - 146%) and 78.4 ± 25.6 (range 26% - 136%) re- spectively. The difference between the first and the last LFT was not significant in both parameters. FVC and FEV1 in the group with pneumothorax were lower than in the control group, both before and after pneumothorax (p < 0.05) (Figure 1). ABPA was presented in six patients (53.4%) in the group with pneumothorax and in four patients (12.5%) in the control group. The difference was not significant. Regarding treatment, eight (18.2%) episodes were re- solved with conservative treatment, thirty-three (75%) with chest tube drainage-aspiration, nine (20.5%) with surgical pleurodesis, two (4.5%) with chemical pleuro- desis, and one (2.3%) with suturing of bullaes (Table 4 ). There were recurrences in eight patients (47.1%), and one patient had nine recurrences. At present, in the group with pneumothorax, three pa- tients have needed lung transplantation (17.6%). Six patients (35.4%) have died, but only two (4.5%) in direct relation to the episode of pneumothorax. In the control group, two patients have died (6.3%). The difference of mortality between both group was statistically signify- Table 4. Management of pneumothorax e pisode s. Method of treatment Episodes number (%) Observation 8 (18.2%) Chest tube drainage 33 (75.0%) Surgical pleurodesis 9 (20.5%) Chemical pleurodesis 2 (4.5%) Suturing of bullaes 1 (2.3%) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM  Factors Associated to the Presence of Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis Patients in the City of Madrid 215 cant, presenting the group with pneumothorax a higher mortality (p < 0.05). cant, presenting the group with pneumothorax a higher mortality (p < 0.05). 4. Discussion Survival in CF patients has increased in the recent years due to the early diagnosis and the creation of multidisci- plinary treatment units [8-10]. This increased survival has been accompanied with the presence of a greater number of age-related complications such as pneumo- thorax. It is observed in our patients since most of them showed the first episode of pneumothorax beyond 18 years of age, indicating that this respiratory complica- tion is more prevalent in those who have a longer sur- vival, as is shown in the literature [3,4,11,12]. Further- more, in our study we have observed that patients who had their first episode after the 18 years were predomi- nantly men. This is explained because, as already men- tioned in the literature, women have a tendency to lower survival [13]. Similarly, almost 50% of patients with pneumothorax experienced recurrences. It might had been because treatments performed were less invasive and less aggre- ssive than those used in pneumothorax caused by other diseases, given that many patients may specify in the future a lung transplant [14,15]. The most frequent symptoms of pneumothorax in our patients were dyspnea and chest pain, which coincides with that described in other series [3,4,16]. The number of episodes in each hemithorax was almost the same. Two patients had a bilateral pneumothorax, one of which debuted with a cardiorespiratory arrest, representing 2.3% of all cases. This form of presentation and the rate of occurrence are somewhat higher than that described by Graf-Deuel et al. [15]. It has been discussed about the seasonal predomi- nance in the appearance of pneumothorax, however in- formation in patients with CF is scarce in this topic [18,19]. We have found that this complication occurs predominantly in colder seasons or in seasons showing more climate variation as are fall, winter and spring time. One possible explanation would be that there are more atmospheric and barometric changes in these times of the year, which may increase the frequency of respira- tory exacerbations and the frequency of treatments with physiotherapy or aerosols, which implies a change in intra- and extra- thoracic pressures. Those patients with CF and pneumothorax had more frequent the presence of P. aeruginosa than other mi- croorganisms in their airways. It is similar to results of other studies that concluded that colonization by P. aeruginosa doubles the likelihood of having a pneu- mothorax and that is associated with a greater and more rapid functional decline [3,4,15,20]. Regarding to the nutritional status, we have seen that the mean BMI of patients with pneumothorax was below the normal values. Some studies had postulated that the nutritional status in these patients is directly related to the respiratory prognosis [21,22]. However, medical li- terature does not indicate any association between this index and the occurrence of pneumothorax in patients with CF. We believe that monitoring the nutritional status of CF patients is important to avoid further com- plications The LFT were affected in the pneumothorax group. The low mean FEV1 before the first episode of pneu- mothorax and its decrease suggest that these patients have a severe pulmonary involvement and that it wors- ens after a pneumothorax episode. As others authors have mentioned, a poor respiratory functional status favors the presence of certain pulmonary complications [12]. We have also found that this complication worsens the respiratory disorder of these patients. We therefore consider that pneumothorax clearly affects the morbidity of CF patients, as the literature postulate [3,4,11,23]. Thirteen patients with pneumothorax (76.4%) had gastrointestinal involvement. Six patients (35.2%) were receiving treatment or had been treated for ABPA, and it was not different from the control group. However, in the work of Flume et al. it was concluded that ABPA increases 1.5 the risk of having a pneumothorax [3]. Regarding treatment, most authors agree that observa- tion alone is only effective for small pneumothorax, where the risk of progression and of recurrence is low [3,23-26]. In our series, in agreement with other series, the most frequent method of therapy was chest tube drainage, although this method seems to be subject of recurrences [23,24,27,28]. This conservative tendency to manage pneumothorax in CF patients is due to the diffi- culty to perform a future lung transplant. For this reason, the less intrusive methods are often used, even when bullectomy or surgical pleural abrasion have demon- strated that are the most effective methods and with less recurrences [4,29]. At present, large pneumothorax (>20% of the hemithorax) are treated initially with chest tube drainage, and only those that are not resolved within seven to 15 days or that recourse, shall be treated with a more aggressive method such as the apical ble- bectomy with thoracoscopy, the ablation of blebs with laser and the apical thoracoscopic talc poudrage [25,30,31]. Chemical pleurodesis is reserved for patients with high surgical risk [23]. Regarding mortality, six patients (35.3%) died in the group with pneumothorax, two directly related to pneu- mothorax and the remaining four within the five years of follow-up. In the control group, two patients (6.3%) died. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM  Factors Associated to the Presence of Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis Patients in the City of Madrid 216 In relation to mortality, the differences were significant between both groups, probably due to the worsening of the respiratory function. According to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consen- sus Conference report, patients with CF should avoid maneuvers or situations which will create marked fluc- tuations in intrapleural pressure to prevent pneumotho- rax. These include intense isometric exercises. In the same way, no air travel or LFT should be undertaken for at least two weeks following resolution of a pneu- mothorax [32-34]. In conclusion, the percentage of episodes of pneu- mothorax observed in our patients is similar to that de- scribed in the literature. Most of these episodes are symptomatic. Low nutritional status, respiratory in- volvement, P. aeruginosa positive-culture and the pres- ence of cold seasons or with more variation in the cli- mate are associated with the apparition of pneumothorax in CF patients. The occurrence of pneumothorax in CF is associated with worsening morbidity and mortality of patients. 5. Acknowledgements Role of sponsors: No commercial sponsor had any in- volvement in the design and conduct of this study, namely collection, management, analysis, and interpre- tation of the data and preparation, decision to submit, review, or approval of the manuscript. Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: Non conflict of interests indicated by the authors. Other contributions: We want to thank to Mr. Ramiro Lopetegui due to his careful lecture and correc- tions of the manuscript. REFERENCES [1] F. S. Collins, “Cystic Fibrosis: Molecular Biology and Therapeutic Implications,” Science , Vol. 256, No. 5053, 1992, pp. 74-79. doi:10.1126/science.1375392 [2] L. Máiz, F. Baranda, R. Coll, C. Prados, M. Vendrell, A. Escribano, et al., “Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Respiratory Involvements in Cystic Fibrosis,” Archivos de Bronconeumología, Vol. 37, No. 6, 2001, pp. 316-324. [3] P. A. Flume, C. Strange, X. Ye, M. Ebeling, T. Hulsey and L. L. Clark, “Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis,” Chest, Vol. 128, No. 2, 2005, pp. 720-728. doi:10.1378/chest.128.2.720 [4] P. A. Flume, “Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis,” Chest, Vol. 123, No. 1, 2003, pp. 217-221. doi:10.1378/chest.123.1.217 [5] F. M. Schramel, P. E. Postmus and R. G. Vanderschueren, “Current Aspects of Spontaneous Pneumothorax,” Euro- pean Respiratory Journal, Vol. 10, No. 6, 1997, pp. 1372-1379. doi:10.1183/09031936.97.10061372 [6] M. L. Spector and R. C. Stern, “Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis: A 26-Year Experience,” The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, Vol. 47, No. 2, 1989, pp. 204-207. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(89)90269-5 [7] J. R. Yankaskas, B. C. Marshall, B. Sufian, R. H. Simon and D. Rodman, “Cystic Fibrosis Adult Care: Consensus Conference Report,” Chest, Vol. 125, No. S1, 2004, pp. 1-39. doi:10.1378/chest.125.1_suppl.1S [8] J. A. Dodge, P. A. Lewis, M. Stanton and J. Wilsher, “Cystic Fibrosis Mortality and Survival in the UK: 1947-2003,” European Respiratory Journal, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2007, pp. 522-526. doi:10.1183/09031936.00099506 [9] A. MacDuff, J. Tweedie, L. McIntosh and J. A. Innes, “Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis: Prevalences and Out- come in Scotland,” Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2010, pp. 246-249. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2010.04.005 [10] N. J. Simmonds, S. J. Macneill, P. Cullinan and M. Hod- son, “Cystic Fibrosis and Survival to 40 Years: A Case- Control Study,” European Respiratory Journal, Vol. 36, No. 6, 2010, pp. 1277-1283. doi:10.1183/09031936.00001710 [11] G. M. Hafen, O. C. Ukoumunne and P. J. Robinson, “Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis: A Retrospective Case Series,” Archives Disease of Childhood, Vol. 91, No. 11, 2006, pp. 924-925. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.095083 [12] M. T. Martínez, “Complicaciones Pulmonares no Infecciosas en la Fibrosis Quística del Adulto,” Archivos de Bronconeumología, Vol. 34, No. 7, 1998, pp. 400-404. [13] S. C. FitzSimmons, “The Changing Epidemiology of Cystic Fibrosis,” The Journal of Pediatrics, Vol. 122, No. 1, 1993, pp. 1-9. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(05)83478-X [14] A. Stenbit and P. A. Flume, “Pulmonary Complications in Adult Patients with Cystic Fibrosis,” The American Journal of Medical Sciences, Vol. 335, No. 1, 2008, pp. 55-59. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31815d2611 [15] T. G. Liou, M. S. Woo and B. C. Cahill, “Lung Trans- plantation for Cystic Fibrosis,” Current Opinion Pulmo- nary Medicine, Vol. 12, No. 6, 2006, pp. 459-463. doi:10.1097/01.mcp.0000245716.74385.3f [16] D. V. Schidlow, L. M. Taussig and M. R. Knowles, “Cys- tic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Conference Report on Pulmonary Complications of Cystic Fibrosis,” Pediatric Pulmonology, Vol. 15, No. 3, 1993, pp. 187-198. doi:10.1002/ppul.1950150311 [17] E. Graf-Deuel and A. Knoblauch, “Simultaneous Bilateral Spontaneous Pneumothorax,” Chest, Vol. 105, No. 4, 1994, pp. 1142-1146. doi:10.1378/chest.105.4.1142 [18] B. Bulajich, D. Subotich, D. Mandarich, R. V. Kljajich and M. Gajich, “Influence of Atmospheric Pressure, Outdoor Temperature, and Weather Phases on the Onset of Spontaneous Pneumothorax,” Annals of Epidemiology, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2005, pp. 185-190. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.04.006 [19] D. Gupta, A. Hansell, T. Nichols, T. Duong, J. G. Ayres and D. Strachanet, “Epidemiology of Pneumothorax in England,” Thorax, Vol. 55, No. 8, 2000, pp. 666-671. doi:10.1136/thorax.55.8.666 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM  Factors Associated to the Presence of Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis Patients in the City of Madrid Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCM 217 [20] L. A. Garske, R. Tam, M. F. Windsor and S. Bell, “Novel Application of Biological Glue in the Management of a Complicated Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis,” Pediatric Pulmonology, Vol. 34, No. 2, 2002, pp. 138-140. doi:10.1002/ppul.10112 [21] P. M. Farrel, M. R. Kosorol, M. J. Rock, A. Laxova, L. Zeng, H. C. Lai, et al., “Early Diagnosis of Cystic Fibro- sis through Neonatal Screening Prevents Severe Malnu- trition and Improves Long-Term Growth,” Pediatrics, Vol. 107, No. 1, 2001, pp. 1-13. doi:10.1542/peds.107.1.1 [22] K. Gaskin, D. Gurwittz, P. Durie, M. Corey, H. Levison and G. Forstner, “Improved Prognosis in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis with Normal Fat Absorption,” The Jour- nal of Pediatrics, Vol. 100, No. 6, 1982, pp. 857-862. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(82)80501-5 [23] C. Prados, L. Máiz, C. Antelo, H. Baranda, J. Blázquez, J. M. Borro, et al., “Cystic Fibrosis: Consensus on the Treatment of Pneumothorax and Massive Hemoptysis and on the Indications for Lung Transplantation,” Archivos de Bronconeumología, Vol. 36, No. 7, 2000, pp. 411-416. [24] A. R. Penketh, R. K. Knight, M. E. Hodson and J. C. Batten, “Management of Pneumothorax in Adults with Cystic Fibrosis,” Thorax, Vol. 37, No. 11, 1982, pp. 850- 853. doi:10.1136/thx.37.11.850 [25] M. Noppen, E. Dhondt, T. Mahler, A. Malfroot, I. Dab and W. Vincken, “Successful Management of Recurrent Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis by Localized Apical Thoracoscopic Talc Poudrage,” Chest, Vol. 106, No. 1, 1994, pp. 262-264. doi:10.1378/chest.106.1.262 [26] R. Amin, P. G. Noone and F. Ratjen, “Chemical Pleu- rodesis versus Surgical Intervention for Persistent and Recurrent Pneumothoraces in Cystic Fibrosis,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Vol. 2, 2009, CD- 007481. [27] S. Fiel, “Clinical Management of Pulmonary Disease in Cystic Fibrosis,” Lancet, Vol. 341, No. 8852, 1993, pp. 1070-1074. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)92423-Q [28] D. J. Seddon and M. E. Hodson, “Surgical Management of Pneumothorax in Cystic Fibrosis,” Thorax, Vol. 43, No. 9, 1988, pp. 739-740. doi:10.1136/thx.43.9.739 [29] H. J. Curtis, S. J. Bourke, J. H. Dark and P. A. Corris, “Lung Transplantation Outcome in Cystic Fibrosis Pa- tients with Previous Pneumothorax,” Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, Vol. 25, No. 7, 2005, pp. 865-869. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2004.05.024 [30] S. R. Hazelrigg, R. J. Landrenean, M. Mack, T. Acuff, P. E. Seifert, J. E. Auer, et al., “Thoracoscopic Stapled Re- section for Spontaneus Pneumothorax,” The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Vol. 105, No. 2, 1993, pp. 392-393. [31] A. Wakabayashi, N. Brenner, A. Wilson, Y. Tadir and W. Berns, “Thoracoscopic Treatment of Spontaneus Pneu- mothorax Using Carbon Dioxide Laser,” The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, Vol. 50, No. 1, 1990, pp. 86-90. [32] D. V. Schidlow, L. M. Tausing and M. R. Knowles, “Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Conference Re- port on Pulmonary Complications of Cystic Fibrosis,” Pediatric Pulmonology, Vol. 15, No. 3, 1993, pp. 187- 198. doi:10.1002/ppul.1950150311 [33] P. A. Flume, P. J. Mogayzel Jr, K. A. Robinson, R. L. Rosenblatt, L. Quittell and B. C. Marshall, “Clinical Prac- tice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee, Cys- tic Fibrosis Pulmonary Guidelines: Pulmonary Complica- tions: Hemoptysis and Pneumothorax,” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Vol. 182, 2010, pp. 298-306. doi:10.1164/rccm.201002-0157OC [34] P. A. Flume, “Pulmonary Complications of Cystic Fibro- sis,” Respire Care, Vol. 54, No. 5, 2009, pp. 618-627. doi:10.4187/aarc0443

|