Journal of Environmental Protection, 2011, 2, 620-628 doi:10.4236/jep.2011.25071 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP Chemical and Bacteriological Analysis of Drinking Water from Alternative Sources in the Dschang Municipality, Cameroon Emile Temgoua University of Dschang, Faculty of Agronomy and Agricultural Science, Dschang, Cameroon. Email: emile.temgoua@univ-dschang.com Received February 28th, 2011; revised April 2nd, 2011; accepted May 9th, 2011. ABSTRACT In the poor zones of sub-Saharan Africa, the conventional drinking water network is very weak. The populations use alternative groundwater sources which are wells and springs. However, because of urbanization, the groundwater sources are degrading gradually making pure, safe, healthy and odourless drinking water a matter of deep concern. There are many pollutants in groundwater due to seepage of organic and inorganic pollutants, heavy metals, etc. Sev- enteen alternative water points created in 2008, for drinking water in Dschang municipality were examined for their physicochemical and bacteriological characteristics. The results revealed that water from managed points in Dschang is of poor quality. Most of the water samples were belo w or out of safety limits (standards) provided by WHO. The wa- ter is characterized by high turbidity and presence of feacal coliforms. It can be used for drinking and cooking only after prior treatment. This situation shows that water point management was limited only to the drawing up comfort. These water points require installation of suitable surfaces of filtration and the development of a chlorination follow-up plan. Specific concerns o f well water were raised and the management options to be taken proposed. Keywords: Sub-Saharan Region, Alternative Water Assessing Point, Water Quality 1. Introduction From time immemorial, water assessment has always been a major concern. Today, the principal difficulty with which we are confronted is not so much access to water but more precisely the access to suitable water for drinking. Indeed the problem arises in terms of the qua- lity of water resources and it is on this point that all the attention is focused, in Cameroon like elsewhere. Water can be the vehicle of a very high number of pathogenic agents voided into the external medium by the human or animal faeces and can thus be at the origin of many wa- terborne diseases. In 1996, WHO quantified to 4 billion, the number of diarrhea episodes which occurred in the world, and were responsible for the death of 3.1 million people of whom the large majority were children less than five years [1]. In the light of these figures, one rea- lizes the importance of the problem of drinking water assessment and the capital need to seek solutions to im- prove the situation in this sector. In Cameroon, the rate of access to drinking water hardly reaches 32% [2]. The town of Dschang, like majority of the medium-sized cities in Cameroon, encounters enormous difficulties of access to drinking water. In a general way, the only one water supplier (CAMWATER) recognized by the State cannot satisfy the request of the increasing population. Thus, this population tries as it can to be supplied with water of very doubtful potability. Many studies in African cities report that, wells, rivers and springs are ubiquitously used for water supply. For these points known as alternative sources (different from conventional network), the quality of water is not known and represents a considerable stake for the municipalities. No authority can authorize even less to invest for a water point of doubtful quality. The practices known as alter- native are quite simply tolerated in the absence of being prohibited. Indeed, many neighbouring pit latrines are opened bottom and can create localised saturated flow conditions that imply great risks of using groundwater [3-5]. The standards only define, at a given moment, a level of acceptable risk for a given population. They depend in addition narrowly on scientific knowledge and the avail- able techniques, in particular in health risks and the che-  Chemical and Bacteriological Analysis of Drinking Water from Alternative Sources in the 621 Dschang Municipality, Cameroon mical analysis domains. They can thus be modified con- stantly according to made progress. Hence, all the coun- tries do not follow the same standards. Some enact their own standards. Others adopt those advised by the World Health Organization (WHO). In Europe, standards are fixed by the European Communities Commission. Today, 63 parameters control the quality of the water for Euro- peans [6]. Groundwater is a valuable natural resource for various human activities [7]. Natural water always con- tains dissolved and suspended substances of organic and mineral origin. The pollution of groundwater is of major concern, firstly because of increasing utilization for hu- man needs and secondly because of the ill effects of the increased industrial activity. High concentration of fae- cal pollutants in groundwater is a considerable health problem in several cities of the sub-Saharan region [5,8]. Regarding water sources that could be supplied for drinking supply in the region of greater urban Dschang there are over 3,000 discrete access points public and private plus additional sources such as bottled, river and rain water. Since 2003 the municipal administration of Dschang devoted considerable resources for development of the water supply and waste management infrastructure at Dschang in partnership with a variety of domestic and foreign non-profits. This municipal initiative has endured through two administrations and two generations of di- agnostic study and constructive innovation spearheaded by the Cameroonian nonprofit making organization (NGO) Environment Research Action (ERA) in 2003, in collaboration with AIMF and the city of Nantes, France in 2005 [9]. The most recent generation of municipal development in urban Dschang’s public water supply sector has been primarily concerned with the expansion of the capacity to deliver adequate quan tities of water to a needy popula- tion, while the issue of water quality has been largely left for the individual to address. However, existing data on trends in public water use and perceptions of water qua- lity reveals a distressingly low prevalence of home-based treatment by the individual. In addition, where treatment solutions are employed by the individual, the elevated level of contamination in the original public water supply often surpasses the effective capacity of the treatment options available [10]. An analysis of the potability of available drinking wa- ter has been synthesized from a body of over 200 micro- bial analyses describing 98 drinking water access points collected by five different studies [5,9,11-13] over the past seven years. These sources can be divided into nine distinct categories: unmanaged springs, treated tap water, managed springs, public wells, private wells, bottled wa- ter, rainwater, untreated tap water, and surface water. Wells include cased and uncased hand dug wells as well as boreholes/tube wells supplying populations, and may be equipped with hand pumps or bucket systems for drawing water. Managed springs is a category that comprises all con- structed ground water capture systems, many of which incorporate slow sand filtration and piped de- livery to public stand posts. Unmanaged springs include natural flowing springs and small hillside stream banks which may or may not have modest improvements such as cemented discharge points and outlet pipes. The surface water category includes larger rivers and streams. Summarizing these studies, one notes the predominant reliance of the population on unmanaged and generally polluted water source. The categories of public wells and managed springs falling within the Dschang municipality reveal the extensive scope (approximately 30% of all consumption) of the city’s role in supplying residents with drinking water. Following close behind comes the second largest single actor, CAMWATER with 23% of total consumption, a significant but largely inadequate figure considering CAMWATER’s position as the sole provider of uniformly uncontaminated drinking water. Water points managed by AIMF concern six (06) drill- ings, seven (07) wells and nine (09) managed springs. So the present study was undertaken to assess the qua- lity of water for 17 of the 22 AWAP of Dschang council where water is available. The sampling for water analysis was done in the month of July 2009 at various location viz. drillings, open wells, and managed springs from Ds- chang council in Cameroon. 2. Methods During the field work, we made in situ measurement of the physical parameters (electric conductivity, Tempera- ture and pH). We also described the environment of each point and when it was possible the water collecting tech- nique was described. We sampled water for physico- chemical and bacteriological analyses (Table 1). 3. Results and discussion Seventeen (17) water points were described and sampled for analysis. These points are shown on Figures 1 and 2. 3.1. Physicochemical Parameters and Cations in Studied Water The results of these parameters in water of the Dschang council are presented in Table 2. 3.1.1. pH The pH values were between 5.1 and 6.9; they excep- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Chemical and Bacteriological Analysis of Drinking Water from Alternative Sources in the Dschang Municipality, Cameroon Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 622 Table 1. Types of apparatuses use d, techniques of selec ted analyses and laboratories requested for the practical realization of work. physico-chemical parameters Type of used apparatus Analysis technique Laboratory pH Portatif SympHony SP80PD de VWRDirect reading In the field conductivity WTW LF318 portatif Direct reading In the field Nitrates NO3- Spectrophotometer DR2500 Hach Cadmium Reduction Method DBO5 BodTrackTM Hach Respirometric Method, incubation at 20˚C during 5 days TDS DCO Spectrophotometer DR2500 Hach Reactor digestion Laboratoire de physiologie végétale Turbidity Spectrophotometer DR2500 Hach Photometric method -//- Faecal Coliforms Culture on Petri boxes With the lactosed gelose with the including TTC and tergitol and counting of the elements Faecal Streptococci Filter membranes Culture in Petri boxes (gelose to the bile, the esculine and the sodium acid) counting of the elements Laboratoire de Biochimie Chlore, bicarbonates, sulfates Titration Direct measurement Na, K, Ca, Mg Flame Photometer JENWAY PFP7 Direct reading Laboratoire d’analyse des sols et de chimie de l’environnement (LASCE) Figure 1. Localization of the Dschang Council in the Western Region of Cameroon in Africa, and various Drinking Water Points managed by AIMF in the rural zone of Dschang and analyzed within the framework of this study. Source: Services techniques, Dschang council.  Chemical and Bacteriological Analysis of Drinking Water from Alternative Sources in the 623 Dschang Municipality, Cameroon Figure 2. Localization of various Drinking Water Points managed by the AIMF in the town of Dschang and analyzed within the framework of this study; Source: Services techniques, Dschang municipality. Figure 3. Showing 100% of correlation between conductivity and Total Dissolved Solid. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Chemical and Bacteriological Analysis of Drinking Water from Alternative Sources in the Dschang Municipality, Cameroon Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 624 Table 2. Physicochemical parameters and cations in studied water. ConductivityTurbidityTDSCaMgK Na SO42- Cl– HCO3-NO3- Water point Type pH microS/cmFTU mg/l 1 Fossong Wentcheng Spring 5.80 47 6 200.161.222.403.50 1.25 0 42.70 3.5 2 Busy Home Spring 5.50 31 7 200.342.640.670.83 0.96 0 6.10 3.0 3 Fongo Ndeng Spring 5.95 17 3 150.122.601.770.83 1.23 0 34.16 17.0 4 Lefock Spring 5.26 81 0 350.361.562.618.54 1.23 1.9 21.35 3.5 5 Atchouazong Spring 6.15 65 0 350.641.960.541.69 1.19 0 91.50 2.8 6 Tchouale Spring 5.50 40 0 200.261.661.432.58 0.23 0 70.15 2.5 7 La Vallée Spring 5.51 80 0 400.641.902.615.43 2.32 0 48.80 5.6 8 Aza’a Foreke-Dschang Drilling 6.15 35 6 250.181.121.842.58 3.90 0 27.45 2.2 9 Centre de santé de Nkeuli Drilling 5.52 51 0 300.361.181.294.45 1.25 0 112.853.0 10 Zembing Drilling 5.15 30 2 200.221.481.430.83 2.44 0 54.90 2.7 11 Ngui Spring 5.60 102 4 450.541.081.502.58 2.98 0 149.452.6 12 Keleng Spring 8.80 27 10 15.60.240.360.060.83 4.87 1.07 67.10 0.9 13 Famla Well6.54 570 6 1272.760.446.4937.73 4.11 1.07 549 2.6 14 Haoussa Well9.94 1400 11 2801.440.1617.7191.83 6.16 0.88 45.75 1.9 15 Tchouale Well6.94 480 10 2681.841.226.1326.56 1.62 0 1210.002.7 16 Fiankop Well6.14 619 12 3001.340.068.9648.45 2.16 3.15 161.6512.2 17 Siteu Drilling 5.20 14 4 20 tionally high (8 to 9) in Keleng and the Haoussa quarters respectively. The pH is evaluated between 0 and 14 and expresses the concentration of the H+ ions in solution. This value for water of good quality must be between 6.9 and 9.2 according to WHO [1] standards. Thus, water sources with pH values lower than 6 are numerous in Dschang. This water is slightly acid. Acid water is corro- sive for the pipes of distribution. 3.1.2. Electrical Conductivity Electrical conductivity is the ability of a solution to lead electrical current. It expresses also the quantity of dis- solved matter (often called salinity). USEPA [14] rec- ommends the limiting value of 300 μS/cm. The electrical conductivity of analyzed water varies between 30 and 100 for the majority of cases examined, except for the following wells (Famla, Haoussa, Tchoualé and Fiankop) whose conductivities were between 480 and 1400 μS/cm. With the exception of well water, all other water points had electrical conductivities in the acceptable range. 3.1.3. Turbidity The turbidity values of less than 5 FTU are limiting for WHO [1]. In line with this, only water obtained in drill- ing of the “Centre de santé de Nkeuli’’ and that of Zembing met this condition. All other water sources were turbid and required filtration before distribution. This is due to the fact that surface water contributes to these sources. 3.1.4. Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) This parameter expresses the salt reaction in solution, or the organic level of pollution of water. Allowable values of TDS range between 500 and 1500 mg/l [1]. For ana- lyzed water, the values of TDS were between 15 and 45 mg/l for the majority of sources examined; water from wells was exceptions where the values of TDS were be- tween 120 and 300 mg/l. In all the cases, TDS values were lower than the range accepted by the standards. 3.1.5. The Ca tions Ca, Mg, K and N a The presence of cations in water expresses the hardness of water. The limiting values according to WHO stan- dards are 75 - 200, 30 - 150, 20, 50 - 60 mg/l respectively for Ca, Mg, K and Na. For the Office cantonal of Vaud (Switzerland), the limiting values of these parameters are 40 - 125, 5 - 30, ≤ 10 and ≤ 20 respectively. The values of these parameters in analyzed water ranged between 0.1 and 0.6; 0.06 to 2.6; 1 to 2.6; 0.8 to 8 mg/l respec- tively for Ca, Mg, K and Na. Calcium (1.3 to 2.7 mg/l), potassium (6 to 17 mg/l) and sodium (37 to 91 mg/l) values were slightly higher in the wells. It appears that only well water has the recommended sodium value. All the other water sources were very slightly mineral-bearing. 3.2. Anions in Studied Water The results of the anions in water of the Dschang council are presented in Table 2.  Chemical and Bacteriological Analysis of Drinking Water from Alternative Sources in the 625 Dschang Municipality, Cameroon 3.2.1. Sulph at es The sulphates in water represent agricultural pollution. The value allowed by the USEPA is ≤ 250 mg/l. For wa- ter of the Dschang council, the values of sulphates were between 0.2 and 6 mg/l; with the high values reported coming from wells (1.6 to 6.16 mg/l). In all the cases, water of Dschang is not polluted according to their sul- phates content. 3.2.2. Chl ori des The chlorides in water are known to come from rainwater. The accepted values are between 200 and 600 mg/l. In water of Dschang, the values obtained were between 0 and 3 mg/l. This water is thus low in chlorides and thus of good quality with respect to chlorides. 3.2.3. Bicarbonates Total alkalinity is the sum of carbonates and bicarbonates. The values of bicarbonates are also used to express alka- linity, in the absence of carbonates. Only one sample showed the presence of carbonates (16 mg/l in the Haou- ssa well). The acceptable values of alkalinity are 200 mg/l. Water of strong alkalinity has a bad taste. For water of Dschang, alkalinity was between 6 and 160 mg/l; however, the water of Tchoualé well had an alkalinity of almost 1200 mg/l. Apart from this point, the other sources were of good alkalinity. 3.2.4. Nitrates The nitrates in water result from pollution by urines and agricultural entrants. The value recommended by WHO is between 40 - 50 mg/l. The elevated nitrate contents cause the disease known as “Blue-baby” or Methaemo- globinase [15]. In Dschang, values were between 0.9 and 3.5 mg/l for the majority of management points. The Fongo Ndeng spring water, and Fiankop wells have raised rates (17 and 12 mg/l respectively) because of nitrates. Agriculture and free grazing animals can explain the first case whereas the second could be an effect of the urban environment. 3.3. Microbiological Parameters in Studied Water Studied water average microbiological density is repre- sented in Table 3. The total coliforms are observed in all water, except for the drilling of Aza’a Foréké- Dschang, and that of the “Centre de santé de NKeuli”, the spring of Keleng and the Haoussa well. The pathogenic bacteria here are faecal coliforms. They result from the contami- nation by excreta. The allowed value by WHO is 0 CFU for 100 ml of water. However, Duchemin [16], sanitary engineer of pS-Eau (France cooperation NGO) delimited in sub saharian zone, less than 20 faecal CFU/100 ml the number of coliforms and faecal streptococci in water intended for human use. One found them in great quan- tity in water of Busy Home, Atchouazong, spring of Tchoualé, spring of Ngui, spring La Vallée and the well of Fiankop. The faecal streptococci sp. were detected only in the spring of Ngui. Table 3. Microbiological analysis of studied water (average of three analyses). samples DBO5 DCO mg/lTotal coliforms (CFU/100 ml) Faecal coliforms (CFU/100 ml) Faecal streptococci (CFU/100 ml) 1 Fossong Wentcheng 9.4 9 42 × 104 0 nd 2 Busy Home 5.6 20 4.55 × 106 2 × 103 nd 3 Fongo Ndeng 11.3 6 3.50 × 106 0 nd 4 Lefock 6.0 5 3.75 × 106 0 nd 5 Atchouazong 5.5 7 2.05 × 104 1 × 103 nd 6 Tchouale 5.5 10 1.50 × 104 1.15 × 104 nd 7 La Vallée 6.6 5 3 × 103 1 × 103 nd 8 Aza’a Foreke-Dschang 9.4 12 0 0 nd 9 Centre de santé de Nkeuli 5.5 15 0 0 nd 10 Zembing 8.5 20 0 0 nd 11 Ngui 12.5 19 3.40 × 104 3 × 103 4 × 103 12 Keleng 10.7 17 0 0 nd 13 Famla 10.5 10 13 × 104 0 nd 14 Haoussa 4.2 12 0 0 nd 15 Tchouale 7.5 13 1 × 103 0 nd 16 Fiankop 8.5 25 9 × 103 3 × 103 nd 17 Siteu 23 nd nd 20 10 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Chemical and Bacteriological Analysis of Drinking Water from Alternative Sources in the 626 Dschang Municipality, Cameroon The DBO5 and DCO are parameters which present organic pollution. They present acceptable values [1,16]. 3.4. Water Quality in Dschang is Due to Urban Environment and Type of Water Point Management Popular practices regarding the raising of livestock and management of human and household wastes reveal ad- ditional knowledge gaps regarding the link between poor sanitation practices and the incidence of water-borne disease. Studies performed in the Dschang area have shown that both human and animal waste contain sig- nificant concentrations of pathogenic organisms. Each inhabitant of the Dschang city, as far as possible, builds its water supply (well in particular) and sanitation devices. Generally there exist in Dschang nearly 8000 open bottom pit toilets, built not far from the water wells [17] and, dug to the groundwater [5]. The full pits are quite simply closed and others dug in the vicinity. The old pits remain thus hidden, becoming a durable source of pollution for the groundwater. Solid waste is voided in the backwaters, the gutters or on open lands. Also, a study conducted in 2002 [18] on the fecal matter of do- mestic chickens, goats, pigs, dogs found that zoonotic infection was prevalent across a variety of species. In- festation by Nematode species was predominant (57.1% testing positive), followed by Cestodes (21.4%), Trema- todes (14.3%) and various Protozoa (7.1%). In a study on quality of drinking water of Kalama re- gion in Egypt, 30% of samples from public waters were contaminated with coliform bacteria [19]. Other studies in Iran showed that total bacteria mean count for tap wa- ter was 1.3 × 104 CFU/ml, and 41% - 67% of water samples from open water sources in India contained coliform and/or faecal coliform bacteria [20]. Djuikom et al. [21] in a study on bacteriological quality of water used by population in Douala stated that faecal coliforms densities varied from 200 and 44 × 103 CFU/100 ml. The management of water points consisted in setting up curbstones, hillocks and the feet supports (Oral com- munication from Dschang Technical Staff). This im- proves much esthetics of drawing up but the analysis of laboratory for the quality of water required was neces- sary before installation. Then, no precaution of protection against anthropic pollution was taken. 3.5. Chemical Pollution is Minimized The health concerns associated with chemical constitu- ents of drinking-water differ from those associated with microbial contamination and arise primarily from the ability of chemical constituents to cause adverse health effects after prolonged periods of exposure [1]. There are few chemical constituents of water that can lead to health problems resulting from a single exposure, except through massive accidental contamination of a drinking-water supply. Moreover, experience shows that in many, but not all, such incidents, the water becomes undrinkable owing to unacceptable taste, odour and appearance. Figure 3 shows the better correlation between TDS and conductivity. Table 4 shows that correlations are also good (86% to 100%) between K and Na, between K and Na and finally between the DBO5 and the DCO. This shows that these parameters are affected between them and that the change of the one influences the other. Table 4. Correlations betw ee n the various studied parameters. pH Cond TurbTDS Ca Mg K Na SO42– Cl– HCO3 NO3 DBO5DCO pH 1.00 Cond 0.52 1.00 Turb 0.67 0.70 1.00 TDS 0.51 1.00 0.70 1.00 Ca 0.35 0.73 0.44 0.73 1.00 Mg –0.60 –0.60 –0.61–0.60 –0.511.00 K 0.65 0.86 0.59 0.86 0.63 –0.601.00 Na 0.68 0.87 0.61 0.87 0.68 –0.650.991.00 SO4 0.79 0.36 0.56 0.35 0.37 –0.700.560.59 1.00 Cl 0.21 0.53 0.43 0.53 0.35 –0.590.440.49 0.23 1.00 HCO3 0.14 0.54 0.34 0.54 0.69 –0.200.220.23 0.00 –0.031.00 NO3 –0.21 0.13 0.04 0.14 –0.070.25 0.050.02 –0.280.27 –0.12 1.00 DBO5 0.01 0.26 0.48 0.26 –0.13–0.270.030.06 0.11 0.32 –0.07 0.09 1.00 DCO 0.06 0.29 0.52 0.30 0.05 –0.370.080.14 0.17 0.29 0.03 –0.05 0.94 1.00 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Chemical and Bacteriological Analysis of Drinking Water from Alternative Sources in the 627 Dschang Municipality, Cameroon 3.6. Health Risks from Water Quality Given the extensive contamination of available water supplies and the health risks posed, the health impacts are going to be largely dependent on the methods and prevalence of home treatment. A limited survey con- ducted on 148 households by ERA-Cameroun [17] re- vealed that only 43% of reporting households subject their drinking water to home based physical or chemical treatment. Of the treatment methods most commonly employed (boiling, bleach, chloramines, ceramic candle filter, membrane filter, cotton filter), their weighted ef- fectiveness amounts to a pathogen removal rate of 92%; inadequate for the levels of contamination observed in one half of the sources analyzed [10]. The inhabitants complain about many diseases, espe- cially the enteric ones which are diseases related to water that they use and with the lack of hygiene. This situation was already revealed by several studies of which: The diagnosis of UN Habitat [22] which announces the cases of typhoid, of the intestinal parasites and di- arrhea like recurring diseases in the city; The study of Boon [9] which announces 18.8% of the patients suffering from the diseases related to water on a whole of 8000 patients indexed in the hospitals, pharmacies and in the tradi-experts of the city: hel- minthiasis: 7.2%, typhoid: 6%, amoebic diarrhea/dy- sentery: 4.9%, intestinal mushrooms: 0.7%). The study of Boon [9] attributes these diseases to the proximity between the Men and the domestic animals (breeding behind the houses). ERA-Cameroun [17] an- nounces that the proximity of the open pit toilets is a main factor at 70%. 4. Conclusions In a general way, the water studied in the Dschang coun- cil is unacceptable for human consumption. For the con- cerns raised below, this consumption could be favorable only when certain constraints will have been overcome: 1) Water from well is turbid and has a high electric conductivity. It is essential to install there a filtration device. 2) All water is slightly mineral-bearing. 3) The water of the Tchoualé well has a high percent- age of bicarbonates (and thus alkalinity). This parameter should be controlled: research of the source and remedia- tion. 4) Water of Busy Home, Atchouazong, spring of Tchoualé, spring of Ngui, spring La Vallée and of the well of Fiankop contains feacal coliforms in great quan- tity. Their treatment by chlorine or bleach is essential. Also, the source of pollution must be detected and elimi- nated. 5) And spring waters of Fongo Ndeng and well of Fi- ankop, have high rates of nitrates. The sources of pollu- tion must be eliminated 6) Sand in water observed in Fossong Wentcheng calls for a complete revision of the system of filtration. For example by laying out filter materials according to adapted particle size, and supporting the water run-off by the filter roof. These water points were already provided to the popu- lations but they require the installation of filtration area and the development of a follow-up plan of chlorination. If the use of chlorine is tiresome, the bleach amounts can be prescribed. 5. Acknowledgements The author is grateful to the International Foundation for Sciences (IFS) for the research grant (Grant W/4206-2). I also appreciate Dr TABI and NIBA of the University of Dschang for proofreading this paper. REFERENCES [1] WHO, “Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, Third Edition, Incorporating the First and Second Addenda, Volume 1: Recommendations,” WHO, Geneva, 2008. [2] INS, “Annuaire Statistique du Cameroun 2007,” Institut National de Statistique, 2008. [3] E. Tanawa, “Gestion et valorisation des eaux usées dans les zones à habitat planifié et leurs périphéries,” Rapport Leseau/ENSP Yaoundé Cameroun/Equipe Développement Urbain INSA de Lyon, September 2002. [4] E. Tanawa, H. B. Djeuda Tchapnga, E. Ngnikam, E. Temgoua and J. Siakeu, “Habitat and Protection of Water Resources in Suburban Areas in African Cities,” Building and Environment, Vol. 37, No. 3, 2002, pp. 269-275. doi:10.1016/S0360-1323(01)00024-5 [5] E. Temgoua, E. Ngnikam and B. Ndongson, “Drinking Water Quality: Stakes of Control and Sanitation in the Town of Dschang – Cameroon,” International Journal of Biology and Chemical Sciences, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2009, pp. 441-447. [6] European Union, “Directive du conseil 98/83/EC sur la qualité de l’eau attendue pour la consommation humaine, ” 1998. [7] B. G. Prasad and T. S. Narayana, “Subsurface Water Quality of Different Sampling Stations with Some Se- lected Parameters at Machilipatman Town,” Nature, En- vironment and Pollution Technology, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2004, pp. 47-50. [8] H. B. Djeuda Tchapnga, E. Tanawa and E. Ngnikam, “L’eau au Cameroun. Tome 1: approvisionnement en eau potable,” Presses Universitaires de Yaoundé, Coll. Con- naissances de …, 2001. [9] N. Boon, “Environmental Burden of Water Borne Disease Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Chemical and Bacteriological Analysis of Drinking Water from Alternative Sources in the 628 Dschang Municipality, Cameroon in Dschang, Western Provence-Cameroon: Health im- pacts and causal factors,” Breaking Ground Report, 2008. [10] V. Katte, M. F. Fonteh and G. N. Guemeh, “Effectiveness of Home Water Treatment Methods in Dschang, Camer- oon,” Cameroon Journal of Experimental Biology, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2005, pp. 102-106. [11] G. N. Guemuh, “Quality of Domestic Water Supply and Effectiveness of Some Locally Used Treatment Me- thods,” Master’s Thesis, the Department of Agricultural Engineering, University of Dschang, Dschang, 2003. [12] A. Da Costa, “L’approvisionnement en eau potable des populations de la ville de Dschang,” Master’s Thesis, the Department of Geography, University of Bordeaux III, 2004. [13] J. Ndounla, “Caractéristiques biologiques et physico- chimiques de l’eau de consommation et influence du mode d’approvisionnement sur la santé des populations à Dschang,” Masters Thesis, the Department of Animal Biology, University of Dschang, Dschang, 2007. [14] USEPA, “Standard Methods for the Examination of Wa- ter and Wastewater, 21st Edition,” Washington DC, 2005. [15] P. Jain, J. D. Sharma, D. Sohu and P. Sharma, “Chemical Analysis of Drinking Water of Villages of Sanganer Tehsil, Jaipur District,” International Journal of Environ- mental Science and Technology, Vol. 2, No. 4, 2005, pp. 373- 379. [16] J. P. Duchemin, “Impact des conditions d’alimentation en eau potable et d’assainissement sur la santé publique,” Document de synthèse pS-Eau, Ouagadougou, 1998. [17] ERA – Cameroun, “Diagnostic de l’approvisionnement en eau et de l’assainissement dans la ville de Dschang,” CUD, 2005. [18] C. Keambou, ”Inventaire des genres parasitaires gastroin- testinaux à potentiel zoonosiques des hommes et des animaux domestiques à Dschang (Ouest-Cameroun),” Thèse de Master, Département de biologie animale, Université de Dschang, Dschang, 2002. [19] M. D. Ennayat, K. G. Mekhael, M. M. El-Hossany, M. Abdel-El Kadir and R. Arafa, “Coliform Organisms in Drinking Water in Kalama Village,” Bulletin of the Nutri- tion Institute of the Arab Republic of Egypt, Vol. 8, 1988, pp. 66-81. [20] H. Moshtaghi and M. Boniadian, “Microbial Quality of Drinking Water in Shahrekord (Iran),” Research Journal of Microbiology, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2007, pp. 299-302. doi:10.3923/jm.2007.299.302 [21] E. Djuikom, E. Temgoua, L. B. Jugnia, M. Nola and M. Baane, “Pollution bactériologique des puits d’eau utilisés par les populations dans la Communauté Urbaine de Douala – Cameroun,” International Journal of Biology and Chemical Sciences, Vol. 3, No. 5, 2009, pp. 967-978. [22] UN-HABITAT, “Municipalité de Dschang: une ville au passé glorieux face aux nouveaux défis,” 2005. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP

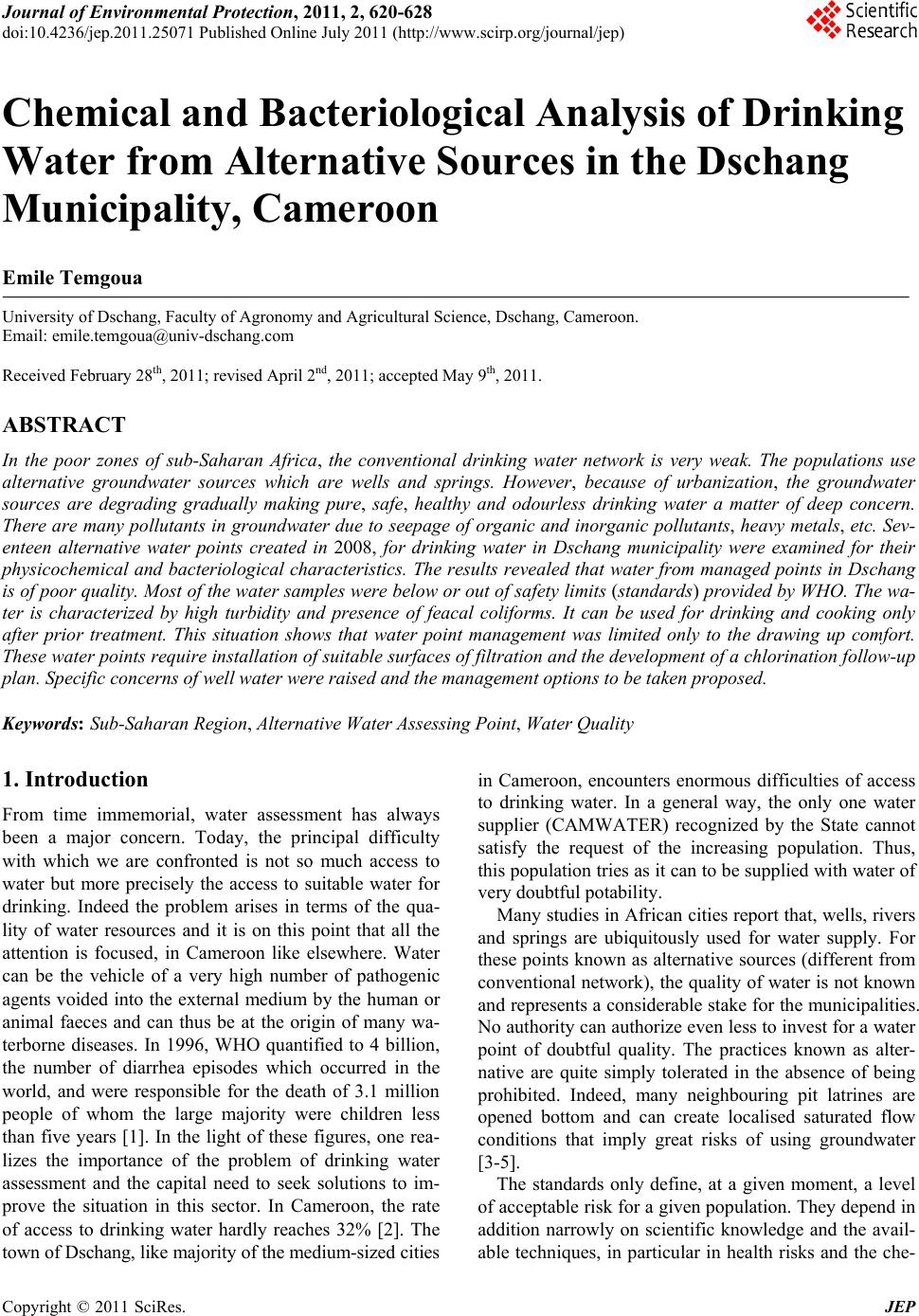

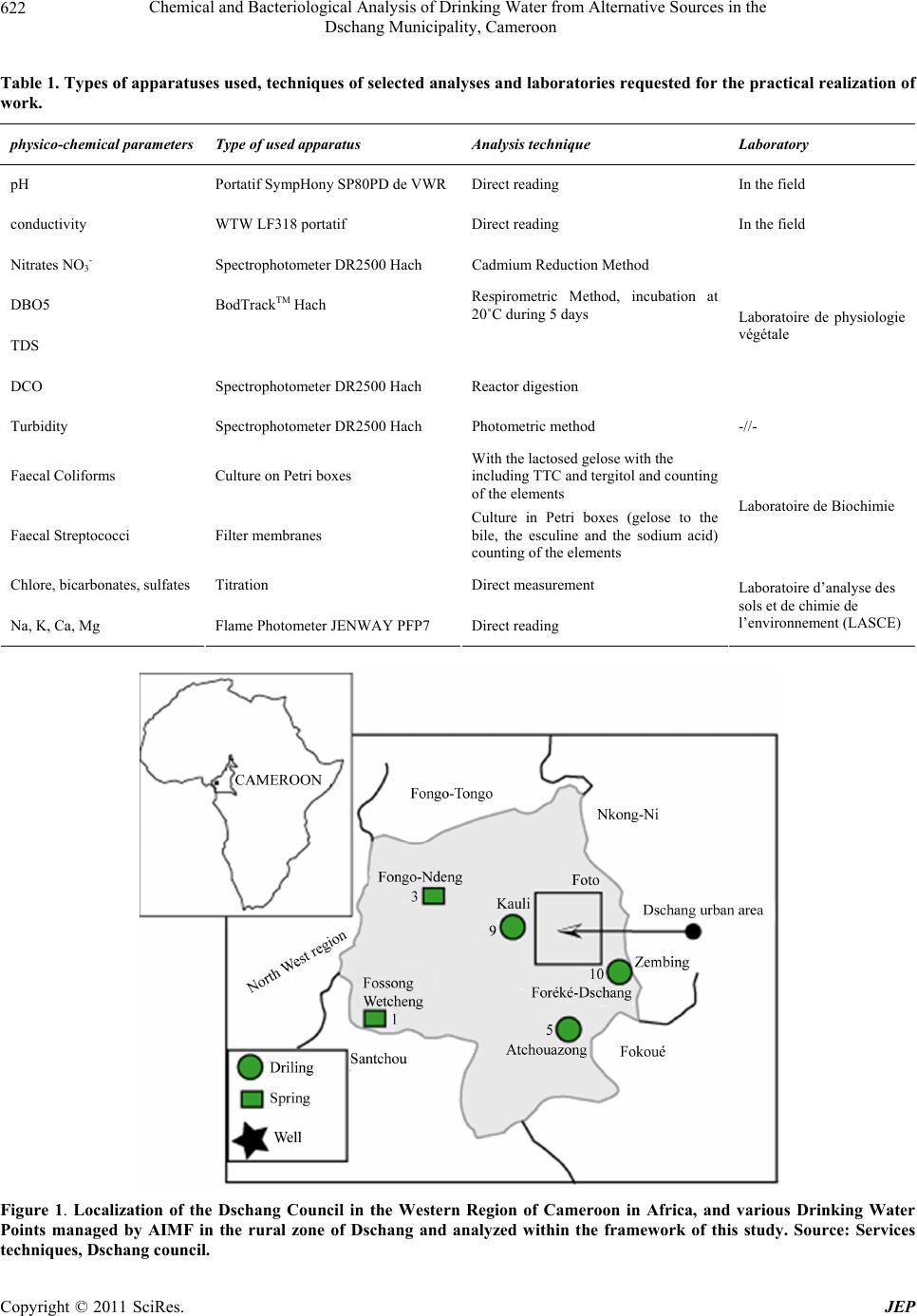

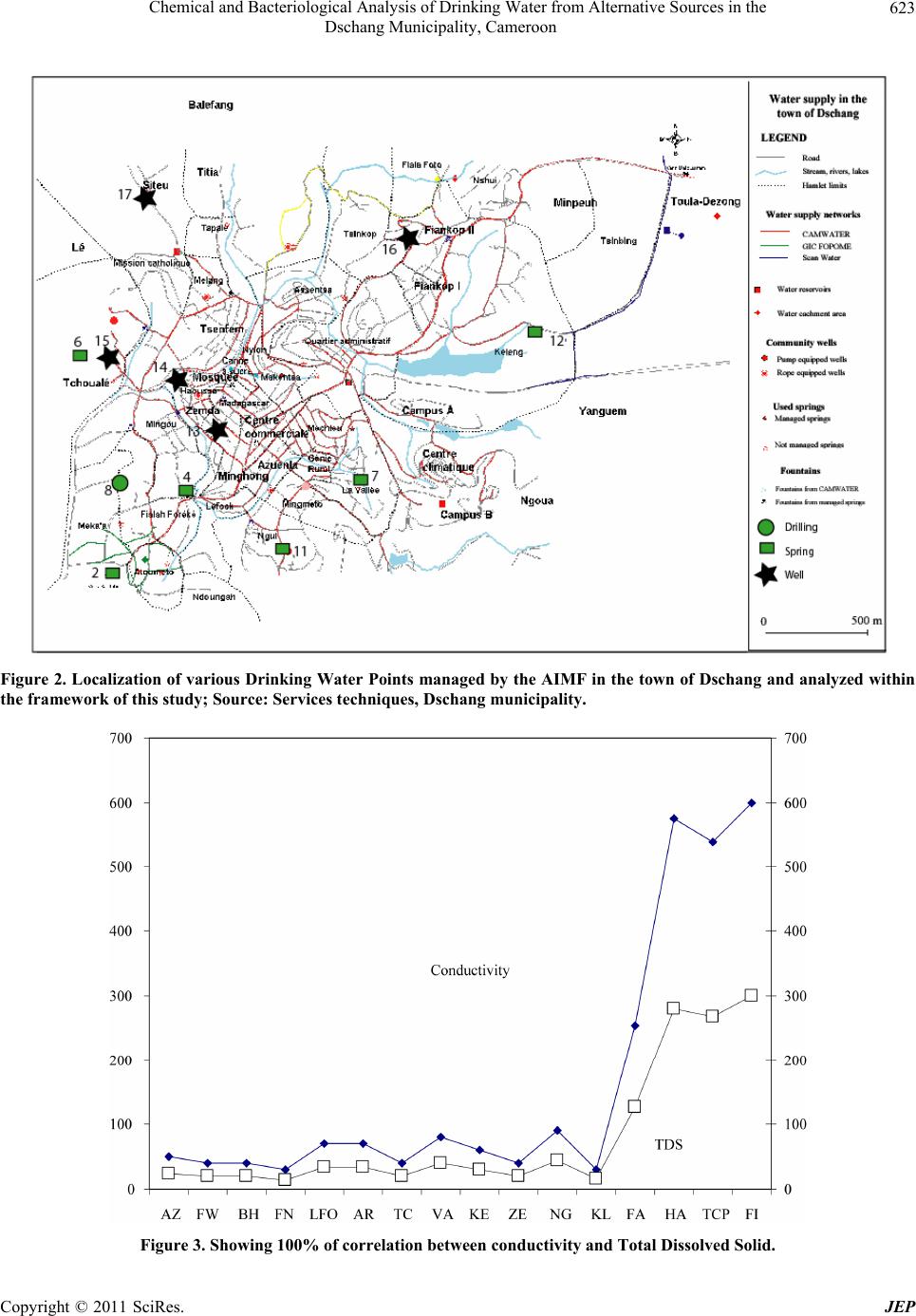

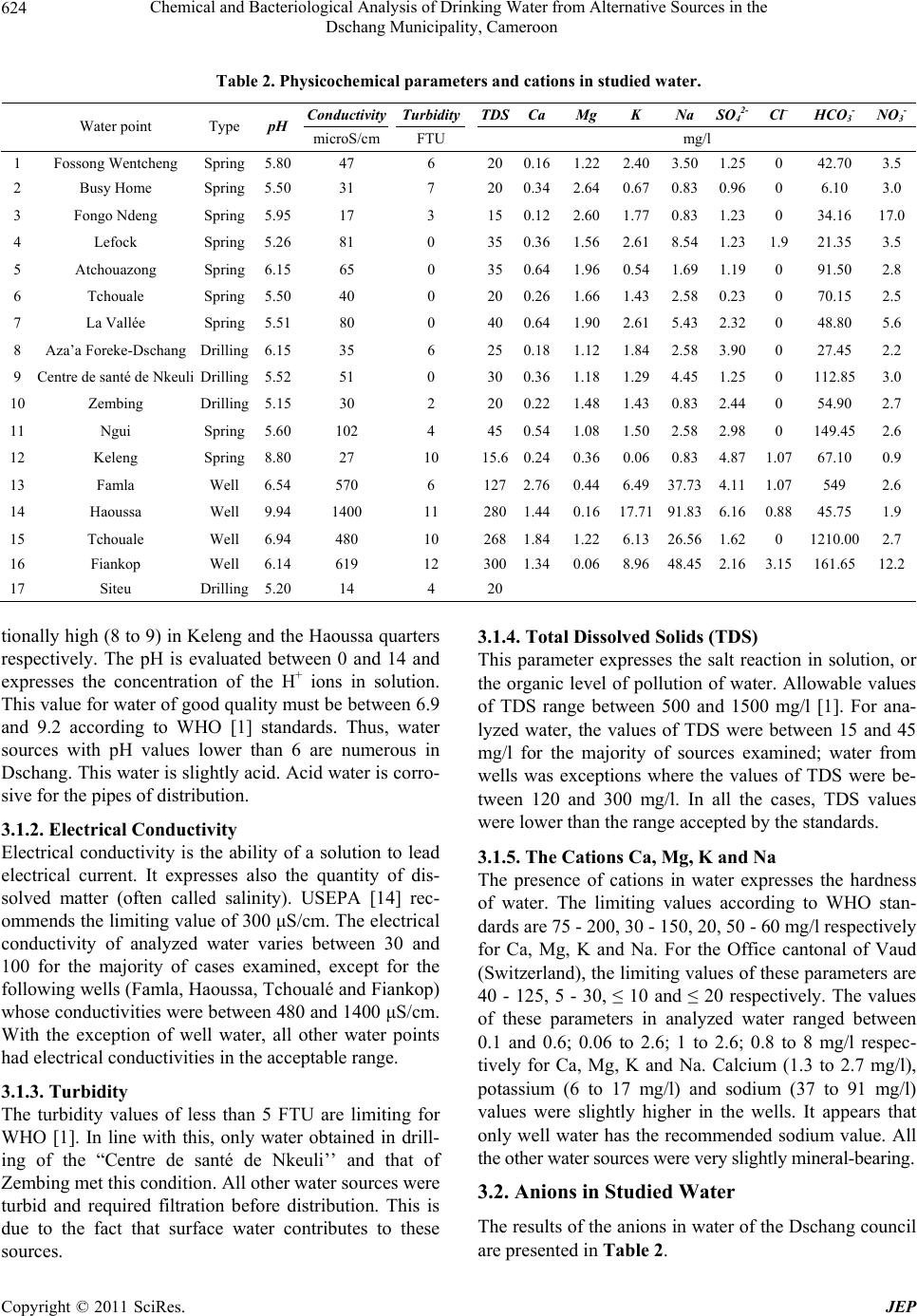

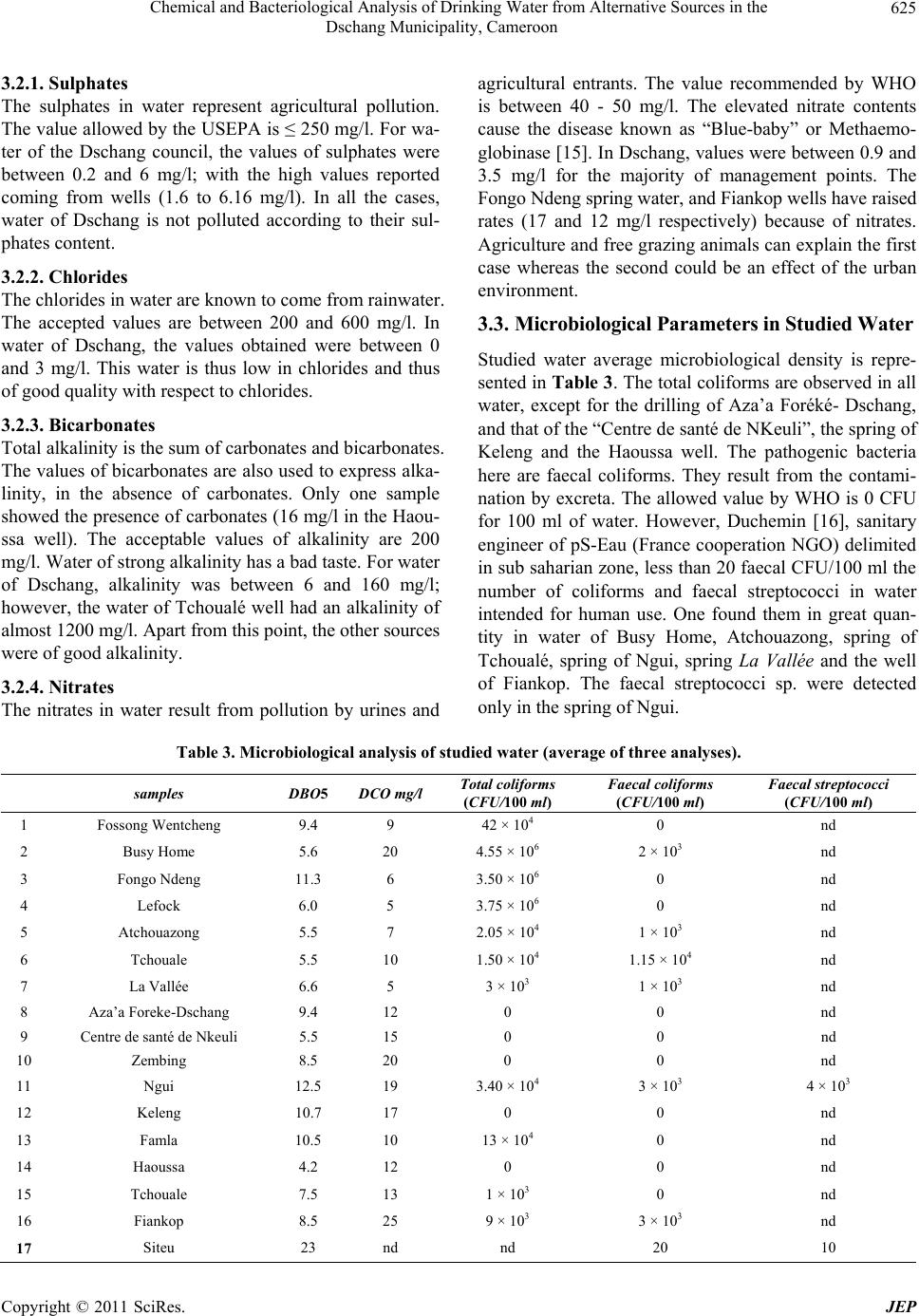

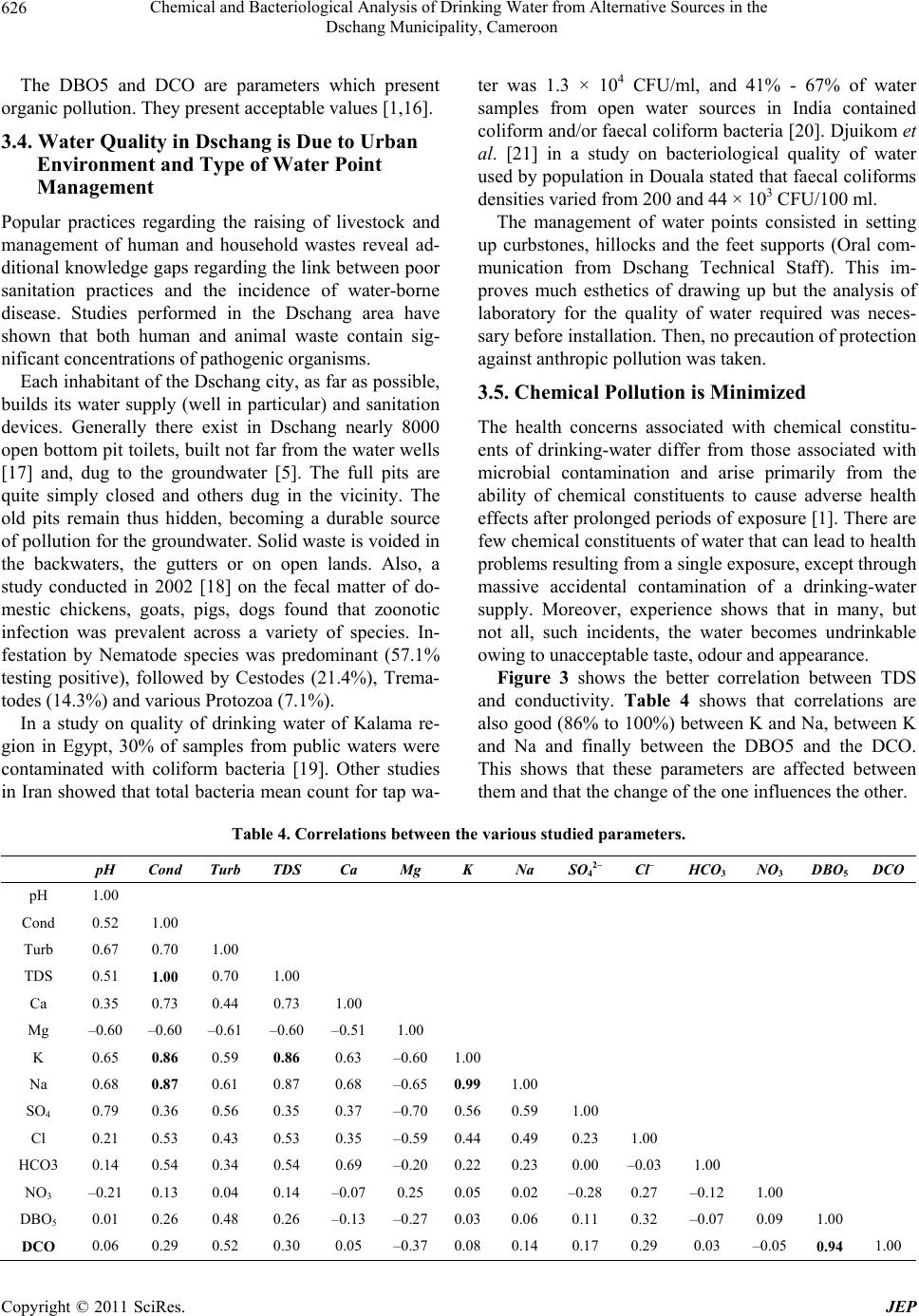

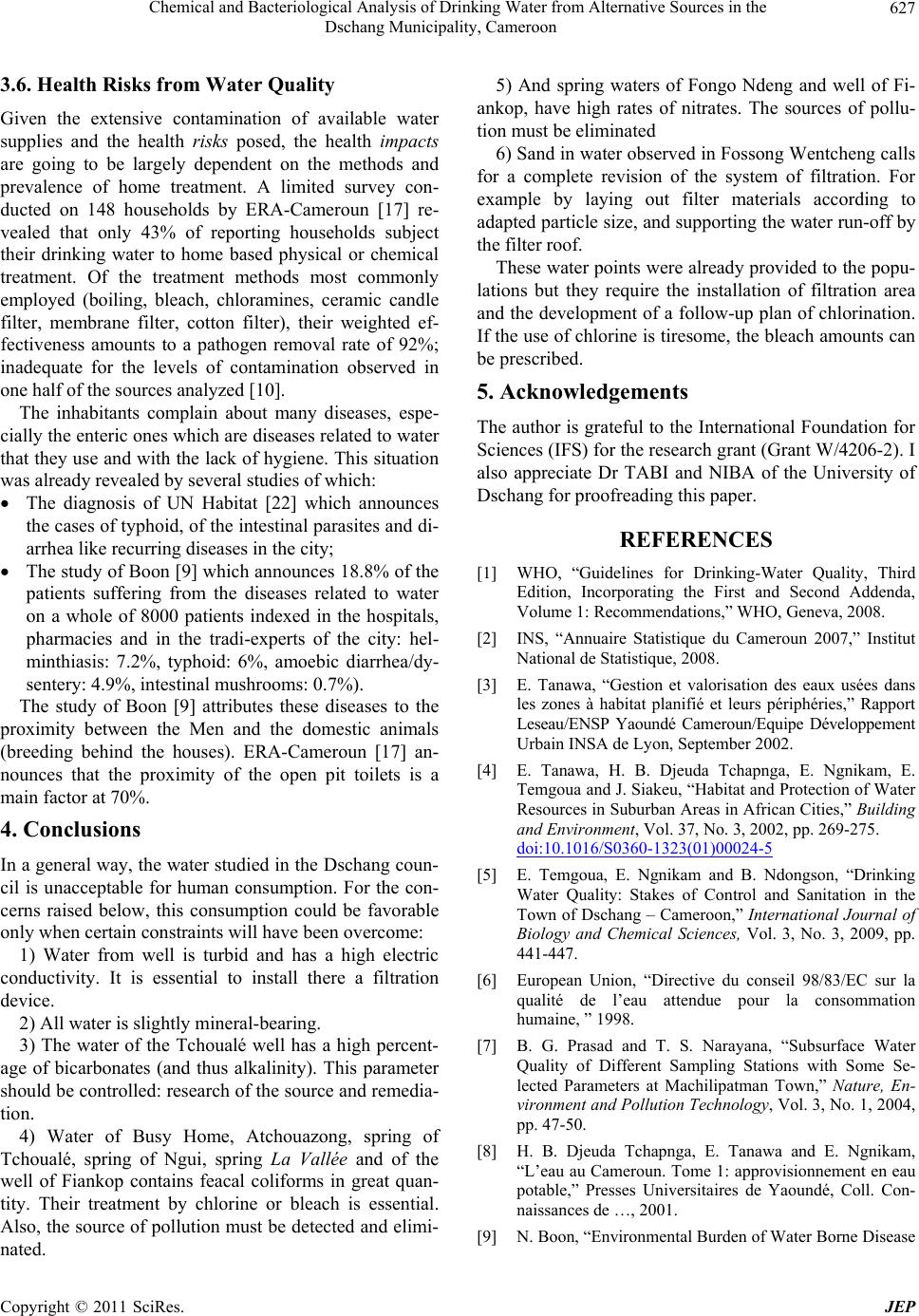

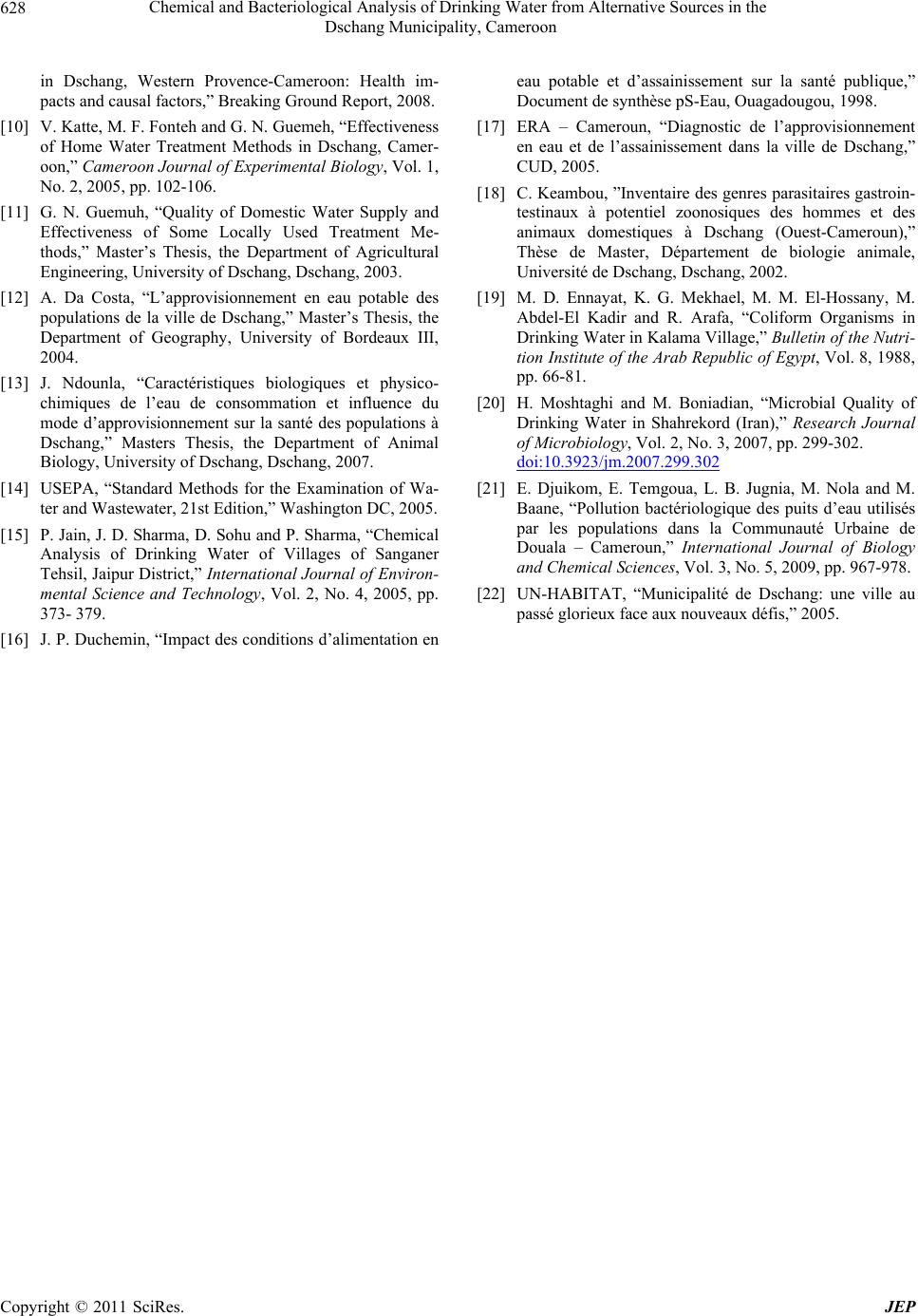

|