Open Journal of Psychiatry, 2011, 1, 66-74 OJPsych doi:10.4236/ojpsych.2011.12010 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJPsych/). Published Onl ine July 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPsych Anger and hostility in the aftermath of a wildfire disaster in Greece Dimitrios Adamis1,2*, Vicky Papanikolaou3 1Research and Academic Institute of Athens, Athens, Greece; 2Institute of Psychiatry, Kings College, London, UK; 3Department of Health Service Management, National School of Public Health, Athens, Greece. E-mail: *dimaadamis@yahoo.com Received 23 May 2011; revised 22 June 2011; accepted 1 July 2011. ABSTRACT Previous studies reported that anger and hostility are often presented in the victims of a disaster. Th is study investigates the symptoms of anger and hostility after a wildfire disaster in a rural area of Greece. Cross sectional case control study of adult population (18 - 65 years old). Face to face interview. Data collected were demographic, Symptom Checklist 90-Revised for assessment of hostility, type and number of losses, trust in institutions personal and social attitudes. It was found that more of the victims of the wildfires reported symptoms of hostility compared to controls but this difference was disappeared when we adjust for other variables. Risk factors for development of hostility among the victims were mistrust in military forces and media, high levels of anxiety and distress, younger age and having higher education. It was concluded that anger and hostility after a disaster perhaps are not only related to disaster but other factors concerning demographic and personal cha- racteristics may play an important role. Keywords: Disaster, Greece, Hostility, Anger, Trust, Wildfires 1. INTRODUCTION Hostility and anger have been reported as often pre- sented in the victims of a disaster. Glass [1], in his se- minal work has classified hostility in the last phase of a disaster (the post-impact period). In this phase hostility and anger appears against those possible responsible, against society and against its leaders. [2 ]. The terms “anger” and “hostility” are often used syn- onymously in disasters literature, but the two constructs can be distinguished. Anger has been described as a neg- ative feeling, an emotional state ranging from irritation to rage; anger is an emotional expres sion of ho stility. On the other hand hostility has been described as a general cognitive personality trait consisting of enmity, denigra- tion, and ill will [3-5]. Hostility is a multidimensional trait but the two key components are cynicism, (the be- lief that others are motivated by selfish concerns), and mistrust, (the belief that other people will tend to be hurtful) [5]. However there are not yet standard defini- tions and Barefoot [6] viewed hostility as an “antagon is- tic interpersonal attitude”, in relation to cognitions (cy- nicism and hostile attribution s), affect (hostile emotions), and beha vi our (aggressive ne ss). Although ther e is a bulk of theoretical work where of- ten has been reported that hostility and anger are com- mon in the aftermath of a disaster there is a lack of em- pirical evidence which examine the prevalence and the factors contributed in the appearance of hostility in the victims of a natural disaster [7]. This perhaps due to that research in natural disasters is focused more on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) than other symptoms or disorders [8,9] and also to that PTSD in- corporates symptoms of irritability and anger. There is evidence, however, that anger and hostility may be dis- tinguished from other symptoms of PTSD in following a more protracted course [10,11]. Hostility has been seen in individuals or may be col- lective and organised and may be directed towards indi- viduals or groups [12]. Often relief workers maybe the focus of hostility of the victims whom they help [13], however, recent research has showed that relief workers also can develop elevated levels of anger and hostility especially those with more severe symptoms of PTSD [7,14,15]. Moreover, hostility after a disaster may have severe implications for the recovery. Individuals with hostility less often visited medical clinics in the aftermath of a disaster [16], although they are in higher risk for cardi- ovascular problems [17], they may have higher levels of lipids in their blood, [18,19], their cortisol levels are  D. Adamis et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 66-74 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych increased [20] and they are in higher risk of all-cause mortality independently of other risk factors (e.g., smoking, cholesterol levels) [4,21]. In addition it has been suggested that severity of anger and hostility is a risk factor of family violence and substance abuse [22], and also that is a factor for maintenance of psychological problems and mostly PTSD [7]. On the other hand, it has been proposed that in some cases the return of anger and hostility can be a sign of a return to normal [23]. Besides, different kind of disaster may have a different impact on mental health and especially in the hostility symptom [24], and it has been suggested [8] that it is important to distinguish continuing situations from time-limited, acute disasters. Likewise different cause of disasters can have impact on the development and ex- pression of hostility and anger. Purely natural disasters (e.g. earthquakes, tsunamis, tornados) can be seen as an uncontrollable event or “act of God” affecting everyone, and fate can determine who is affected. On the other hand human made or technological disasters may evoke more easily anger, hostility and blaming behaviour as they due to human error or miscalculation [25-28]. Hos- tility and anger can become dominant as victims blame what they perceive to be the responsible agent, [25] and they disagree over acts to stop or remediate the event or over relief or rescue methods [25,26]. However, there is not clear distinction of manmade and natural in the case of wildfire disasters. Wildfires can be caused from hu- man error or deliberately but also can be caused acci- dentally from natural causes (lighting, weather condi- tions) [29]. In a previous analysis of our data [30] where we ex- amined only the psychopathology we have found that those victims of the disaster without losses were more hostile compared to those with losses. We had speculated that those with d amages were in priority to receive most of the support and so they may were less hostile. How- ever, given that hostility is a personality trait and given that hostility and anger can be affected by other social, demographic, and personal attitudes, as above reported, hostility may pre-existed the disaster and perhaps disas- ter may exacerbated it. Similarly, other factors like per- sonal attitudes, believes, and trust which were not ex- amined in the previous study may influence hostility and anger. Consequently, in the present study we hypothe- sised that hostility after a disaster may is not only related to the disaster but perhaps socio-demographic and per- sonal factors contribute as well. The present study is a post-hoc analysis of collected data after a wildfire disa s- ter. Therefore the aims of the present study are threefold: a) to estimate the time prevalence of hostility symptoms in the victims of a disaster, b) to investigate risk factors for hostility, and c) to evaluate the associations of losses, demographic and social factors with hostility sympt oms. 2. METHODS 2.1. History In August of 2007 an intense wildfire broke out in the Peloponnesus peninsula in Greece. This was the worst of a century in Greece. Sixty to eighty people were reported killed and 5392 people affected from the disaster [31]. About 1500 square kilometers of forests, olive trees, farmland, and villages were burned in these fires and the economic damages were estimated around 1,750,000 (×1000) US$. 2.2. Design of the Study This study was a cross sectional case control study. Cas- es and controls were closely matched for gender, age, educational, marital and regional distributions. The de- sign, procedure, and the measures for this study are more fully described in a previous study [30]. 2.3. Participants Residents aged from 18 years to 65 years old who lived in the five prefectures designated by the Hellenic Re- public Ministry of Interior to be disaster areas served as cases and residents from nearby non affected areas as controls. The number of respondents surveyed in each prefecture was proportion al to its adult population. 2.4. Measurements 1) Demographic characteristics (age, gender, educational background, mar ita l s ta tus, occupation). 2) Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90-R) [32]. A Greek validated version of SCL-90-R was used [33]. The SCL-90R has 90 items, which measure the degree of distress experienced the individual during the last 7 days, using a 5-point scale (0 to 4) that ranges from “not at all” to “extremely.” The SCL-90R can be scored for nine symptom dimensions. In addition to the nine dimensions, there are three global indices that are computed. The Global Severity Index (GSI), which reflects both the number of symptoms endorsed and the intensity of per- ceived distress. The Positive Symptom Total (PST) which is a measure of the number of symptoms endorsed and can be interpreted as a measurement of symptoms span, and the Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI), which is a measure of “intensity” corrected for the num- ber of symptoms. According to SCL-90-R caseness is defined when a respondent has a GSI score greater or equal to a T score of 63, or if any of two dimensions scores are greater than or equal to a T score of 63. 3) Hostility: To measure hostility the 6 questions of hostility dimension of the SCL-90-R were used. Those  D. Adamis et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 66-74 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych are “feel easily annoyed or irritated”, “temper outbursts that you cannot control”, “have urges to beat, injure or harm somebody”, “have urges to break or to smash things”, “have frequent arguments”, “shouting or throw- ing things”. The hostility dimension of SCL-90-R re- flects thoughts feelings or actions that are characteristics of anger. The six questions of SCL-90-R asses quantities such as aggression, irritability, rage, and resentment [32]. 4) Number and type of losses as a result of the fire in- cluding: a) damage to property, b) complete damage and loss of property, c) personal injury or injury of a close family member, and d) deaths of close family members. 5) A questionnaire which examines the trust of res- pondents in 12 institutions/ establishments/ organiza- tions namely: Government, Church, Military, Local government, Private sector, Trade-unions, Non Govern- mental/Voluntary organizations, Justice, Education, Po- lice, Political parties, and Media. 6) A questionnaire with 21 social values in which the participants could choose which were most important for them. Among the social values were Prestige, Devotion, Autonomy, Ostentation of power, Mutual Help, Modesty, Wealth, Equality, Tradition, Public recognition, Safety, and others. 2.5. Procedure Data were collected in face-to-face interviews conducted during a 14-day period beginning 6 months after the outbreak of the wildfires (March 2008). The interviewers were qualified psychologists and social workers, who had a previous training for the use of SCL-90-R. Households in designated disaster areas and in the near- by undamaged by fire areas were selected randomly from residency data provided by the municipalities sur- veyed. Participants were given cards upon which the survey questions were printed. Because educational le- vels in this region are relatively low, each question was read out loud by the interviewer as well, who recorded the participants’ responses. 2.6. Ethics The study has been approved by the Ministry of Health and informed consent was obtained from each partici- pant. 2.7. Statistical Analy sis The Q Local v 2.1.11, (NCS Pearson Inc, MN, USA), was used for the estimation of the standardized T scores from the raw data for the SCL-90-R scale. Data were analysed with PASW (SPSS) v18, using appropriate bi- variate statistics. For the non-normally distributed data, non-parametric tests were used. To identify risk factors for hostility caseness a logistic regression analysis was performed. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Demographics The initial sample consisted of 800 participants: 409 cases (victims from the disaster) and 391 controls. Be- cause of missing data, uncompleted questionnaires, and exclusion of individuals who gave the same rate (0 or 4) in all the questions in the SCL-90-R, the final analysed sample here consisted of 615 participants (353 cases and 262 controls). The finally analysed two groups were closely matched regarding gender, age, education, occu- pation and regional characteristics. (See table 1). 3.2. Caseness According to SCL-90-R (Psychopathology Dimensions). Those who had a T score of 63 and above in each psy- chopathology dimension of SCL-90-R defined as case- ness. Table 2 shows the caseness’ actual numbers and percentages in each psychopathology dimension for cas- es (victims) and controls. 3.2.1. Hostility Those participants who had T scores of 63 and above in the hostility dimension of SCL-90-R defined as hostile (caseness). By this definition 110 participants (18%) of the sample (N = 615) were found to have increased the dimension of hostility (T scores ≥ 63). Using X2 tests we compared the two populations (those with hostility and those without) in terms of socio-demographic characte- ristics (age, gender, marital status, occupation, educa- tion), sampled group (controls or victims from the disas- ter), losses (number of losses, property damages, com- plete damages of property, injuries of self or relatives, death of close relative), trust in institu- tions/establishments (Government, Church, Military, Local government, Private sector, Trade-unions, Non Governmental/Voluntary organizations, Justice, Educa- tion, Police, Political parties, Media), and Social values and Personal attitudes (Dialogue/communication among people, Stable social rules, Os tentation of power/wealth, Autonomy, Mutual support, Modesty, Wealth, Variety, Equality, Compliance with law, Adventure, Leisure, Na- ture, Prestige, Creativity, Devotion, Public recognition, Safety, Having a good time, Tradition, State). No differ- ences were found in the two groups with the exception in the variables showed in Table 3. Thus, victims of the wildfire, those who did not trust the police and the jus- tice system, and those who value more nature and leisure but not modesty as a per- sonal value had statistically significa nt i ncrease d the dim ens i on of hostility.  D. Adamis et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 66-74 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych Table 1. Demographic characteristics of sample. Table 2. Caseness accordi ng to SCL-90-R. Cases N = 353(%) Controls N = 262(%) Count Row % Count Row % SOMATIZATION NO 290 55.3% 234 44.7% YES 63 69.2% 28 30.8% OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE (OC) NO 253 55.7% 201 44.3% YES 100 62.1% 61 37.9% INTERPESONAL SENSITIVITY (IS) NO 261 56.0% 205 44.0% YES 92 61.7% 57 38.3% DEPRESSION NO 247 53.2% 217 46.8% YES 106 70.2% 45 29.8% ANXIETY NO 273 55.3% 221 44.7% YES 80 66.1% 41 33.9% HOSTILITY NO 279 55.2% 226 44.8% YES 74 67.3% 36 32.7% PHOBIC ANXIETY NO 287 55.2% 233 44.8% YES 66 69.5% 29 30.5% PARANOID NO 228 53.1% 201 46.9% YES 125 67.2% 61 32.8% PSYCHOTISM NO 278 55.4% 224 44.6% YES 75 66.4% 38 33.6% GSI NO 250 53.8% 215 46.2% YES 103 68.7% 47 31.3% PSDI NO 224 56.9% 170 43.1% YES 129 58.4% 92 41.6% PST NO 276 54.2% 233 45.8% YES 77 72.6% 29 27.4% Cases N = 353(%) Controls N = 262(%) Pearson X2 Gender male 182(51.6) 131(50.0%) X2 = 0.15, df = 1, p = 0.7 (NS) female 171(48.4) 131(50.0) Age group 18 - 25 59(16.7) 36(13.7) X2 = 1.32, df = 4, p = 0.86 (NS) 26 - 35 79(22.4) 59(22.5) 36 - 45 72(20.4) 59(22.5) 46 - 55 76(21.5) 55(21.0) 56 - 65 67(19.0) 53(20.2) Education Primary school 101(28.6) 72(27.5) X2 = 5.6, df = 2, p = 0.06 (NS) Secondary s chool 222(62.9) 152(58.0) College/university 30(8.5) 38(14.5) Marital status married 240(68.0) 180(68.7) X2 = 0.043, df = 3, p = 0.98 (NS) single 99(28.0) 72(27.5) divorced 4(1.2) 3(1.1) windowed 10(2.8) 7(2.7) Occupation professional occupation 59(16.7) 46(17.6) X2 = 0.50, df = 2, p = 0. 78 ( NS) sales and customer service occupation 57(16.1) 47(17.9) elementary occupation 237(67.2) 169(64.5)  D. Adamis et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 66-74 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych 3.2.2. Logistic Regression. (Predictors of Hostility). To control for the confounding variables a logistic re- gression model were conducted with dependent variable the hostility (outcome yes/no) and independent variables all the above measured variables plus the psychopathol- ogy dimensions of SCL-90-R and the three indices (GSI, PST, PSDI). The b ackward stepwise (Wald) method was used. The final more parsimonious model is presented in Table 4. The final model predicts overall correctly 86.5% of participants and the prediction in creases for those without hostility fo r whom the model classify co r- rectly 94 % while the prediction for the hostility drops to 51%. Thus, those of the participants who scored higher (pa- thological) levels of hostility were those in youngerage groups (18 - 55 years old), those who did not trust the military forces and the media, those who had higher le- vels of anxiety (pathological) and they had a broader and more intensive number of symptoms (PST and PSDI). 3.2.3. Predict ors of Hostility in the Victims of the Disaster. Further we analyse only the victims of the disaster. From the 353 victims the 74 (21%) had increased hostility. Doing the same analysis as above on the victims’ sample (logistic regression) we found that those hostile victims were those who did not trust the military forces and the media. Although overall age and education did not con- tribute significantly to the model those in the 26 - 55 groups ages were more hostile compared to older group age (56 - 65 years old group). Similarly with education, overall education did not have any effect on hostility but those with higher education (college/univ ersity), appears to be more hostile compared to those who finished pri mary school. As with the entire sample, victims with increased hostility had also increased levels of anxiety and they had more intensive and wider number of symptoms. Tab l e 5 shows the final model with the pre- dictive variables. The final model predicts overall cor- rectly the 84% of the victims and for those without ho s- tility classifies correctly the 94% while those with hos- tility the model classifies correctly the 44.5%. 4. DISCUSSION This study addresses the relationship between a natural disaster (wildfires) and the hostility symptom of psy- chopathology. Although, bivariate analysis showed that the victims of the wildfires had increased hostility com- pared to controls, after adjusting for other sociodemo- graphic factors neither the impact of disaster nor the losses caused by it, had any effect on the symptom of hostility. In other words the symptom of hostility was independent by both disaster and losses caused by the Table 3. Hostility (Bivariat e statistics). NO (%) YES (%) Pearson X X2 = 5.3, df = 1, p = 0.02 Trust in Justice X2 = 5.29, df = 1, p = 0.021 YES 40(7.9) 2(1.8) X2 = 6.23, df = 1, p = 0.013 X2 = 7.91, df = 1, p = 0.005 Nature NO 257(50.9) 38(34.5) X2 = 9.67, df = 1, p = 0.002 X2 = 4.97, df = 1, p = 0.026 Table 4. Predictors of hostility. B S.E. Wald χ2 df Sig. Exp(B) 95% C.I.for EXP(B) Lower Upper Age group 14.089 4 0.007 18 - 25 1.671 0.470 12.625 1 0.000 5.316 2.115 13.359 26 - 35 1.230 0.446 7.626 1 0.006 3.423 1.429 8.196 36 - 45 1.296 0.464 7.805 1 0.005 3.654 1.472 9.069 46 - 55 1.363 0.449 9.220 1 0.002 3.908 1.621 9.422 Trust in military 1.122 0.472 5.649 1 0.017 3.071 1.217 7.744 Trust in media 1.404 0.637 4.862 1 0.027 4.071 1.169 14.178 PST –1.046 0.369 8.047 1 0.005 0.351 0.171 0.724 PSDI –1.357 0.271 25.029 1 0.000 0.257 0.151 0.438 Anxiety –2.017 0.347 33.783 1 0.000 0.133 0.067 0.263 Constant –2.165 0.836 6.703 1 0.010 0. 11 5  D. Adamis et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 66-74 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych Table 5. Predictors of hostility only in the victims. B S.E. Wald χ2 df Sig. Exp(B) 95% C.I.for EXP(B) Lower Upper 36 - 45 1.226 0.590 4.317 1 0.038 3.407 1.072 10.830 Safety –0.601 0.338 3.166 1 0.075 0.548 0.283 1.063 disaster. In addition young er age, mistrust in the military forces and the media and high levels of anxiety and dis- tress were predictors for the symptom of hostility. It is important to note here that the military forces were the most important aid for the relief of the victims but also they had played a crucial role in the fire-fighting to stop the catastrophic event. Literature on exposure to other types of natural disas- ter (floods) indicates increased hostility in the victims [22]. Similarly, Bland [34] reported in creased hos tility in male residents of Pozzuoli following an earthquake compared to non-residents and further analysis showed that hostility was more increased in those relocated and in those victims with financial losses. In manmade dis- asters (technological) it was reported the surprising finding that employees in the damaged nuclear plant in the Three Mile Island accident had lower scores on the hostility and mistrust than other residents of the area [35]. However, surrounding circumstances of the Three Mile Island accident (initial failure of plant operators to recognize the situation, and the release of the film The China Syndrome few days before the accident) may ex- plain this finding. Therefore, although hostility has been observed in the victims of a disaster other reasons may contribute as well. The above reported studies did not control for other factors and they found that victims are more hostile compared to controls (like in the present study, when bivariate analysis was used). However, a study of survi- vors of the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire of 1977 (Green [36]) in which regression analysis was used, re- ported that hostility was predicted from the stress caused by the fire and demographic factors (particularly age). Although direct comparison of Green et al.’s study with the present one is difficult, because of the different type of disaster, different methodology, and different meas- ured variables, the Green et al study further supports the indication that hostility and perhaps other symptoms of psychopathology are not only related to victim/control distinction, but they may related also to other factors concerning social and personal attitudes. Similarly, emo- tional and psychological support, supportive network, close family ties may influence the outcome of trauma. However, it is important to consider both the positive and negative consequences of social involvement be- cause it was found for instance that spouse support may reduce male symptomatology but this is associated with increased symptomatology in exposed to disaster fe- males. Very strong social ties may be more burdensome than supportive in extreme stress [37]. Nevertheless, including other variables such as social may add more to predictive outcome than a simple comparison of vic- tims/controls psychopathology or distress. It has been argued that manmade disasters are pheno- menologically and etiologically different from natural disasters [38], and as above reported wildfires some- times can be in the middle. During the time of wildfires in Greece there was a political campaign for the national election. There was a suspiciousness that the fires might have been set by political extremists, to disrupt political campaign. This suspiciousness was not only among laymen but also the Prime Minister in a nationally tele- vised address suggested it. [39]. Media spread it as well [40], but six months later when this study was carried  D. Adamis et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 66-74 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych out nobody has been held responsible. This could ex- plain to some degree the mistrust to the media. However, general the lack of trust has also been re- ported in other studies investigating victims of disaster e.g. [41]. Previous studies have showed that trust is es- sential component of resilience, and individuals and communities can effectively respond to a disaster by gathering together trust, and social support, to either re-establish a previous state of equilibrium or develop a different but still adaptive state e.g. [42-46]. A previous study has shown that Greeks have a low level of trust in the most public institutions [47]. Simi- larly, a more recent survey on younger Greek population (18 to 28 years old) also reported a low trust in public institutions and politics. In addition, the same survey reported that more than half (53%) of the Greek young people are unconcerned about others and only 21.5% trust others to some degree [48]. Mistrust and a negative attitude toward others are es- sential components to hostility [49]. Thus, it is very likely that in both cases and controls the mistrust and the negative attitude pre-existed to the disaster and so we do not find any effect from the disaster because it was con- founded with pre-disaster attitudes. Alternatively, if the disaster had provoked mistrusts and disbelief to others we should find that victims were more hostile than con- trols. In addition to our hypothesis that hostility pre-exists to disaster is that hostility is rather a personal- ity trait and an attitude that may be derived from nega- tive interpersonal experiences and thus it is more likely to be a long standing symptom rather than a symptom caused instantly after the disaster [50]. Moreover, bio- logical (serotonergic system) and genetic factors regulate so many of the behavioural and psychosocial characte- ristics. Research on genes has focused on variants in genes encoding for proteins involved in the regulation of serotonergic function. It is suggested that the serotonin 1B receptor gene play an important role in phenotypes of personality domains related to anger and hostility [51,52]. A rather surprising finding of this study was that hos- tility in the victims of wildfire was associated with high- er education. Generally educated people report less hos- tility and anger toward others but when worried, anxious, or tense, they are more likely to report anger along with it [53]. A previous study of explosive anger in post-conflict victims showed that among others, higher levels of education is negatively associated with anger [11]. However, not all the studies in d isasters hav e found that education has a protective effect on hostility e.g. among survivors of the Oakland/Berkeley firestorm [54], on individuals exposed to a flood in South Africa [55]. There is no obvious explanation for this finding. A spec- ulation is this suggested by Gibbs [56]. Considering that higher education is associated with higher income and possible higher social class when those individu als were equally affected by disaster as lower class individuals, it may be that higher social class individuals have more to lose in the disaster. Their expectations and the standards of living may be higher and more crudely disrupted than the expectations of lower class or less educated individ- uals. Although, in the present study, we did not find any effect of the type or the number of losses in the hostility dimension, it is possible that more educated people may have greater expectations than less educated, and thus they are perhaps more hostile than the less educated. A second possibility is that hostility effects of a traumatic experience may affect more those educated who may have more pressure and responsibilities compare to oth- ers and perhaps take also responsibilities for other non-educated people. 4.1 Limitations of the Study Culture and milieu may have influenced the relationship of hostility and victims of the wildfire disas ter. Although SCL-90-R estimate psychopathology based in the last 2 weeks there is possibility of recall bias or influences in the other measurements as well, since the study was conducted 6 months after disaster. We did not use other measures of hostility. However, SCL-90-R is a good measurement of hostility as it evaluates hostility as a spectrum from anger to aggression. REFERENCES [1] Glass, A.J. (1959) Psychological aspects of disaster. Journal of American Medical Association, 171, 222-225. [2] McGonagle, L.C. (1964) Psychological Aspects of Dis- aster. American Journal of Public Health and the Na- tion’s Health, 54, 638-643. doi:10.2105/AJPH.54.4.638 [3] Spielberger, C.D., Jacobs, G., Russell, S.F. and Crane, R.S. (1983) Assessment of anger: The state-trait anger scale. In: Butcher, J.N. and Spielberger, C.D. Eds., Ad- vances in Personality Assessment, Erlbaum , Hillside. [4] Smith, T.W., Glazer, K., Ruiz, J.M. and Gallo, L.C. (2004) Hostility, anger, aggressiveness, and coronary heart dis- ease: An interpersonal perspective on personality, emo- tion, and health. Journal of Personality, 72, 1217-1270. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00296.x [5] Powell, L.H. and Williams, K. (2007) Hostility. In: Fink, M.G. Eds., Encyclopedia of Stress, Academic Press, New York, 354-358. [6] Barefoot, J.C., Dodge, K.A., Peterson, B.L., Dahlstrom, W.G. and Williams, R.B.Jr. (1989) The Cook-Medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict surviv- al. Psychosomatic Medicine, 51, 46-57. [7] Jayasinghe, N., Giosan, C., Evans, S., Spielman, L., and Difede, J. (2008) Anger and posttraumatic stress disorder in disaster relief workers exposed to the September 11, 2001 World Trade Center disaster: One-year follow-up  D. Adamis et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 66-74 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196, 844-846. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e31818b492c [8] Weiss, M.G., Saraceno, B., Saxena, S. and van Ommeren, M. (2003) Mental health in the aftermath of disasters: Consensus and controversy. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191, 611 -615. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000087188.96516.a3 [9] Hussain, A., Weisaeth, L. and Heir, T. (2010) Psychiatric disorders and functional impairment among disaster vic- tims after exposure to a natural disaster: A population based study. Journal of Af fective Disorders, 128, 135-141. [10] Orth, U., Cahill, S.P., Foa, E.B. and Maercker, A. (2008) Anger and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in crime victims: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Con- sulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 208-218. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.208 [11] Silove, D., Brooks, R., Steel, C.R.B., Steel, Z., Hewage, K., Rodger, J. and Soosay, I. (2009) Explosive anger as a response to human rights violations in post-conflict Ti- mor-Leste. Social Science & Medicine, 69, 670-677. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.030 [12] Edwards, J.G. (1976) Psychiatric aspects of civilian dis- asters. British Medical Journal, 1, 944-947. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.6015.944 [13] I. Palmer. (2005) ABC of conflict and disaster. Psycho- logical aspects of providing medical humanitarian aid. British Medical Journal, 331, 152-154. [14] Ursano, R.J., Fullerton, C.S., Kao, T.C. and Bhartiya, V.R. (1995) Longitudinal assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression after exposure to traumatic death. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 183, 36-42. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7509.152 doi:10.1097/00005053-199501000-00007 [15] Evans, S., Giosan, C., Patt, I., Spielman, L. and Difede, J. (2006) Anger and its association to distress and so- cial/occupational functioning in symptomatic disaster re- lief workers responding to the September 11, 2001, World Trade Center disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19, 147-152. doi:10.1002/jts.20107 [16] Donker, G.A., van der Velden, P.G., Kerssens, J.J. and Yzermans, C.J. (2008) Infrequent attendance in general practice after a major disaster: A problem? A longitudinal study using medical records and self-reported distress and functioning. Family Pr actice, 25, 92-97. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmn007 [17] Beckham, J.C., Flood, A.M., Dennis, M.F. and Calhoun, P.S. (2009) Ambulatory cardiovascular activity and hos- tility ratings in women with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological P sychiatry, 65, 268-272. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.024 [18] Brindley, D.N., McCann, B.S ., Niaura, R., Stoney, C.M. and Suarez, E.C. (1993) Stress and lipoprotein metabol- ism: Modulators and mechanisms. Metabolism, 42, 3-15. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(93)90255-M [19] Lane, J.D., Pieper C.F., Barefoot J.C., Williams, R.B.Jr. and Siegler, I.C. (1994) Caffeine and cholesterol: Interac- tions with hostility. Psychosomatic Medicine, 56, 260-266. [20] Wang, H.H., Zhang, Z.J., Tan, Q.R., Yin, H., Chen, Y.C., Wang, H.N., Zhang, R.G., Wang, Z.Z., Guo, L., Ta ng, L.H. and Li. L.J. (2010) Psychopathological, biological, and neuroimaging characterization of posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of a severe coalmining disas- ter in China. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44, 385-392. doi:10.1007/s10865-005-9016-5 [21] Zhang, J., Niaura, R., Todaro, J.F., McCaffery, J.M. and Shen, B.J., Spiro, A. and Ward, K.D. (2005) Suppressed hostility predicted hypertension incidence among mid- dle-aged men: The normative aging study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28, 443-454. doi:10.1016/S1068-8595(00)80020-3 [22] Clemens, P., Hietala, J.R., Ry tter, M.J., Schmidt, R.A. and Reese, D.J. (1999) Risk of domestic violence after flood impact: Effects of social support, age, and history of domestic violence. Applied Behavi oral Sc ienc e Rev ie w, 7, 199-206. doi:10.1016/S1068-8595(00)80020-3 [23] Ursano, J.R., Fullerton, S.C. and Benedek, M.D. (2009) What is Psychopathology after Disasters? Considerations about the nature of the psychological and behavioral consequences of disasters in mental health and disasters. In: Neria, Y., Galea, S. and Norris, F.H. Eds., Mental Health and Disasters, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 131-145. [24] Norris, F.H., Friedman, M.J. and Watson, P.J. (2002) 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part II. Summary and im- plications of the disaster mental health research. Psy- chiatry, 65, 240-260. doi:10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169 [25] Cuthbertson, B.J. and Nigg, J.M. (1987) Technological disaster and the nontherapeutic community: A question of true victimization. Envir onmen t and Beha vior, 19, 462-483. [26] Kroll-Smith and J.S. and Couch, S. (1990) The real dis- aster is above ground: A mine fire and social conflict. University of Kentucky Press, Lexington. [27] Quarantelli, E., Dynes, R.R. (1976) Community conflict: Its absence and its presence in natural disasters. Mass Emergencies, 1, 139-156. [28] Havenaar, J.M. and Rumyantzeva, G.M., van den Brink, W., Poelijoe, N.W., van den Bout J., van Engeland, H. and Koeter, M.W. (1997) Long-term mental health ef- fects of the Chernobyl disaster: An epidemiologic survey in two former Soviet regions. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1605-1607. [29] Taylor, A.J. (1987) A taxonomy of disasters and their victims. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 31, 535-544. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(87)90032-8 [30] Papanikolaou, V., Adamis, D., Mellon, R.C. and Prodro- mitis, G. (2011) Psychological distress following wild- fires disaster in a rural part of Greece: A case-control population-based study. International Journal of Emer- gency Mental Health, in press. [31] EM-DAT. (2008) The OFDA/CRED International Disas- ter Database Prevention Web http://www.preventionweb.net/english/countries/stat istics/index.php?cid=68. [32] Derogatis, L.R. (1992) SCL-90-R: Administration, scor- ing & procedures manual-II, for the (revised) version and other instruments of the psychopathology rating scale se- ries. 2nd Edition, Clinical Psychometric Research, Tow- son. [33] Donias, S., Karastergiou, A. and Manos, N. (1991) Stan- dardization of the Symptom Checklist 90 rating scale in a Greek population. Psychiatriki, 2, 42-48. [34] Bland, S.H., O’Leary, E.S., Farinaro, E., Jossa, F. and Tr e visanm, M. (1996) Long-term psychological effects of natural disasters. Psychosomatic Medicine, 58, 18-24.  D. Adamis et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 66-74 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych [35] Chisholm, R.F., Kasl, S.V., Dohrenwend, B.P., Dohren- wend, B.S., Warheit, G.J., Goldsteen, R.L., Goldsteen, K. and Martin, J.L. (1981) Behavioral and mental health ef- fects of the three mile island accident on nuclear workers: A preliminary report. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 365, 134-135. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb18127.x [36] Green, B.L., Grace, M.C. and Gleser, G.C. (1985) Iden- tifying survivors at risk: Long-term impairment follow- ing the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire. Journal of Con- sulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 672-678. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.53.5.672 [37] Solomon, S.D ., Smith, E.M., Robins, N.L. and Fischbach, R.L. (1987) Social Involvement as a Mediator of Disas- ter-Induced Stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 17, 1092-1112. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1987.tb02349.x [38] Green, B.L., Lindy, J.D. and Grace, M.C. (1995) Psy- chological effects of toxic contamination. In: Ursano, R.J., McCaughey, B.G., Fullerton, C.S. Eds., Individual and Community Responses to Trauma and Disaster: The Structure of Human Chaos, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [39] CNN (2007) Greek leader suggests political extremists set fires. http://articles.cnn.com/2007-08-25/world/greece.fires_1_ fire-victims -t op-fire-offici al-pel. [40] M. Nodaros (2007) Land of Death Eleftherotypia, Tego- poulos, Athens. http://archive.enet.gr/online/online_text/c=112,dt =26.08.2007,id=2440200 [41] Quinn, S.C. (2006) Hurricane Katrina: A social and pub- lic health disaster. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 204. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.080119 [42] Rolfe, R.E. (2006) Social cohesion and community resi- lience: A multidisciplinary review of literature for rural health research. Department of International Develop- ment Studies Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research Saint Mary’s University, Halifax. [43] Schellong, A., Wolfgang, J. and Main, F. A. (2007) In- creasing social capital for disaster response through so- cial networking services (SNS) in Japanese Local Gov- ernments. Harvard University, Cambridge. [44] Sakamoto, M. and Yamor y, K. (2009) A Study of life recovery and social capital regarding disaster victims–A case study of Indian ocean tsunami and central java earthquake recovery. Journal of Natural Disaster Science, 21, 13-20. [45] Paton, D., Houghto n, B.F., Gregg, C.E., McIvo r, D., Johns- ton, D.M., Burgelt, P., Larin, P., Gill, D.A., Ritchie, L.A., Meinhold, S. and Horan, J. (2009) Managing Tsunami risk: Social context influences on Preparedness. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 3, 27-37. doi:10.1097/01.crd.0000246318.59658.25 [46] Kirmay er, J.L., Sehdev, M., Whitley, R., Dandeneau, F.S. and Isaac, C. (2009) Community resilience: Models, me- taphors and measures. Journal of Aboriginal Health, 5, 62-117. [47] Lyberaki, A. and Paraskevopoulos, J.C. (2002) Social capital measurement in Greece. Paper presented at the International Conference on Social Capital Measurement. www.oecd.org/dataoecd/22/15/2381649.pdf [48] Papadimitriou, V. (2007) Family is a supporting system for the 60% of young people. Apogeumatini tis Kyriakis, Athens, 18-19. [49] Schulman, J.K. and Stromberg. S. (2007) On the value of doing nothing: Anger and cardiovascular disease in clin- ical practice. Cardiology Review, 15, 123-132. doi:10.1097/01.crd.0000246318.59658.25 [50] Berkowitz, L. (1993) Aggression: Its causes, conse- quences, and control. Temple University Press, Philadel- phia. [51] Lesch, K.P., Bengel, D., Heils, A., Sabol, S.Z., Greenberg, B.D., Petri, S., Benjamin, J., Muller, C.R., Hamer, D.H. and Murphy, D.L. (1996) Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science, 274, 1527-1531. [52] Conner, T.S., Jensen, K.P., Tennen, H., Furneaux, H.M., Kranzler, H.R. and Covault, J. (2010) Functional poly- morphisms in the serotonin 1B receptor gene (HTR1B) predict self-reported anger and hostility among young men. American Journal of Medical Genetics part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetic, 153B, 67-78. [53] Mirowsky, J. and Ross, C.E. (2007) Education levels and stress. In: Fink M.G. Ed., Encyclopedia of Stress, Aca- demic Press, New York, 888-892. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30955 [54] North, C.S., Hong, B.A., Suris, A. and Spitznagel, E.L. (2008) Distinguishing distress and psychopathology among survivors of the Oakland/Berkeley firestorm. Psychiatry, 71, 35-45. doi:10.1080/00224545.1970.9919957 [55] Strumpfer, D.J. (1970) Fear and affiliation during a dis- aster. Journal of Social Psychology, 82, 263-268. doi:10.1080/00224545.1970.9919957 [56] Gibbs, M.S. (1989) Factors in the victim that mediate between disaster and psychopathology: A review. Journal of Traum atic Stre ss, 2, 489-514. doi: 10.1007/BF00974604

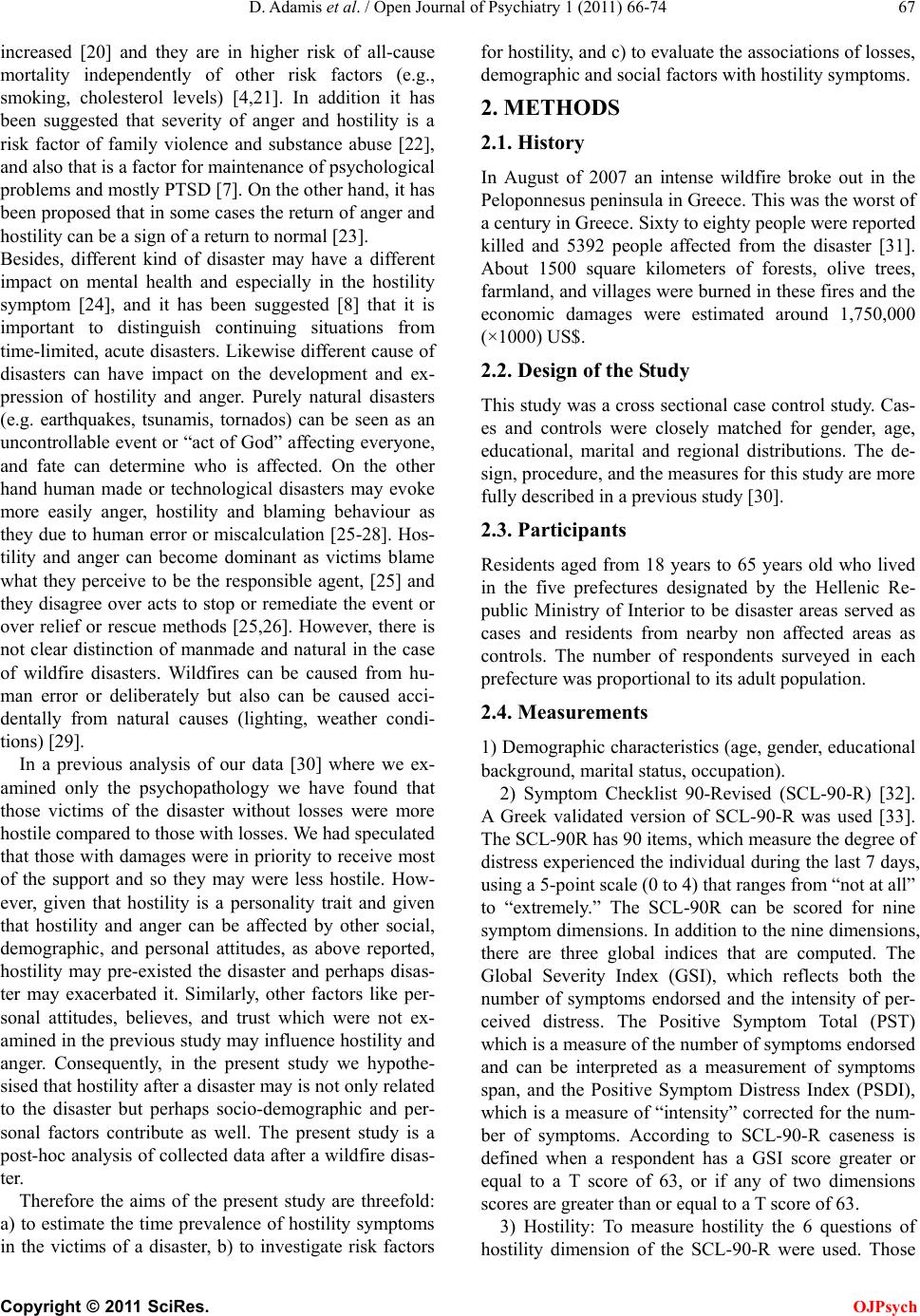

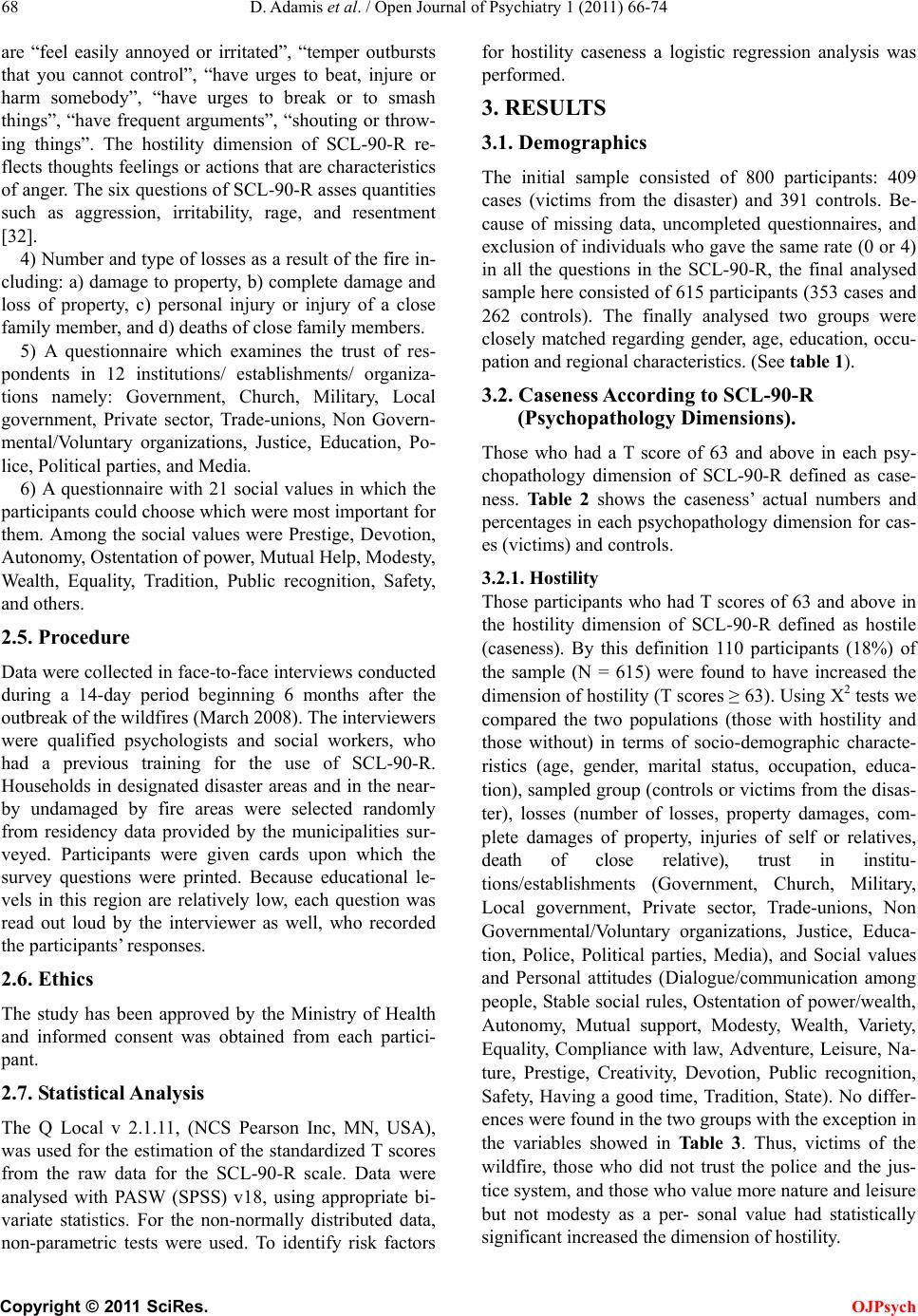

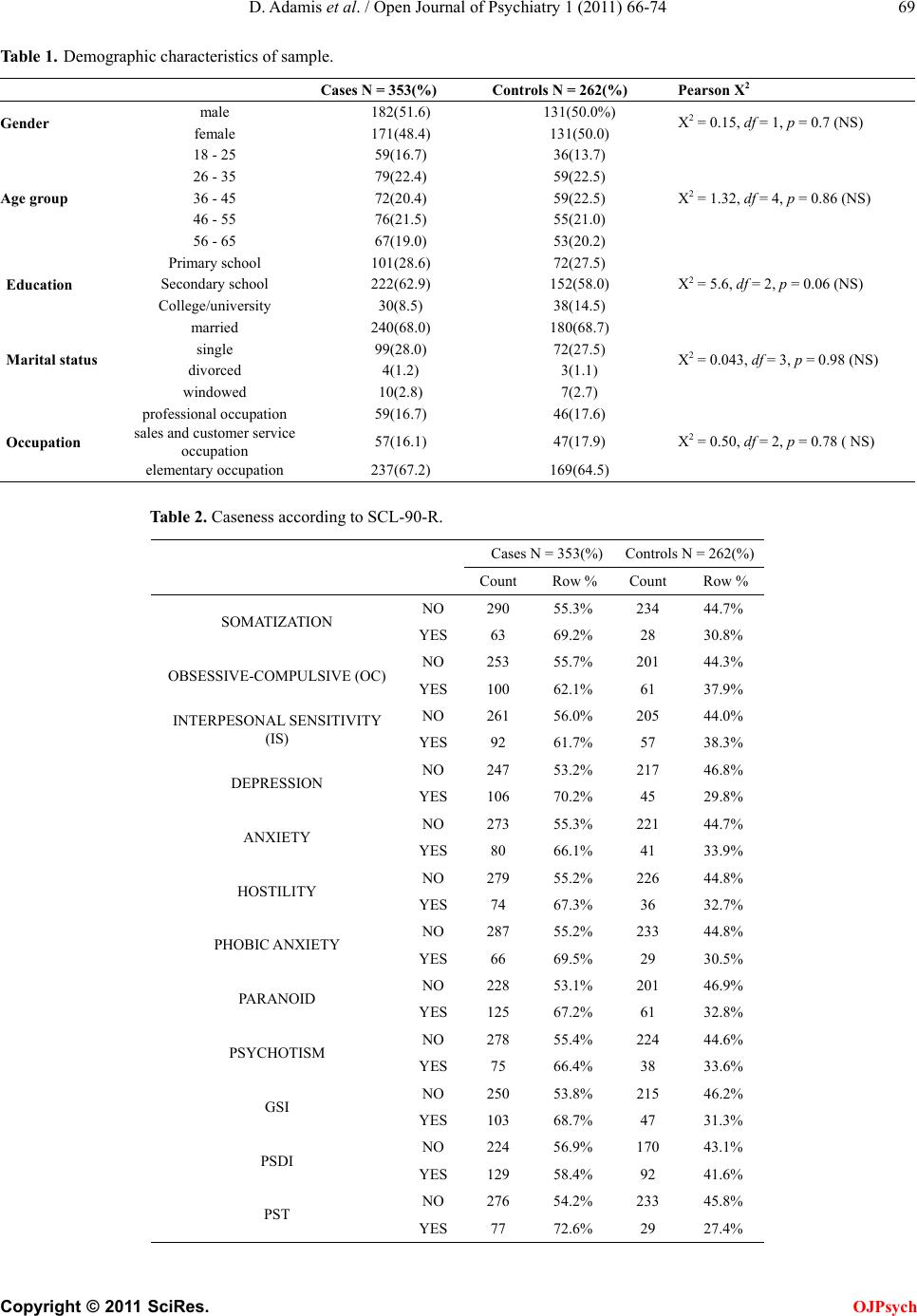

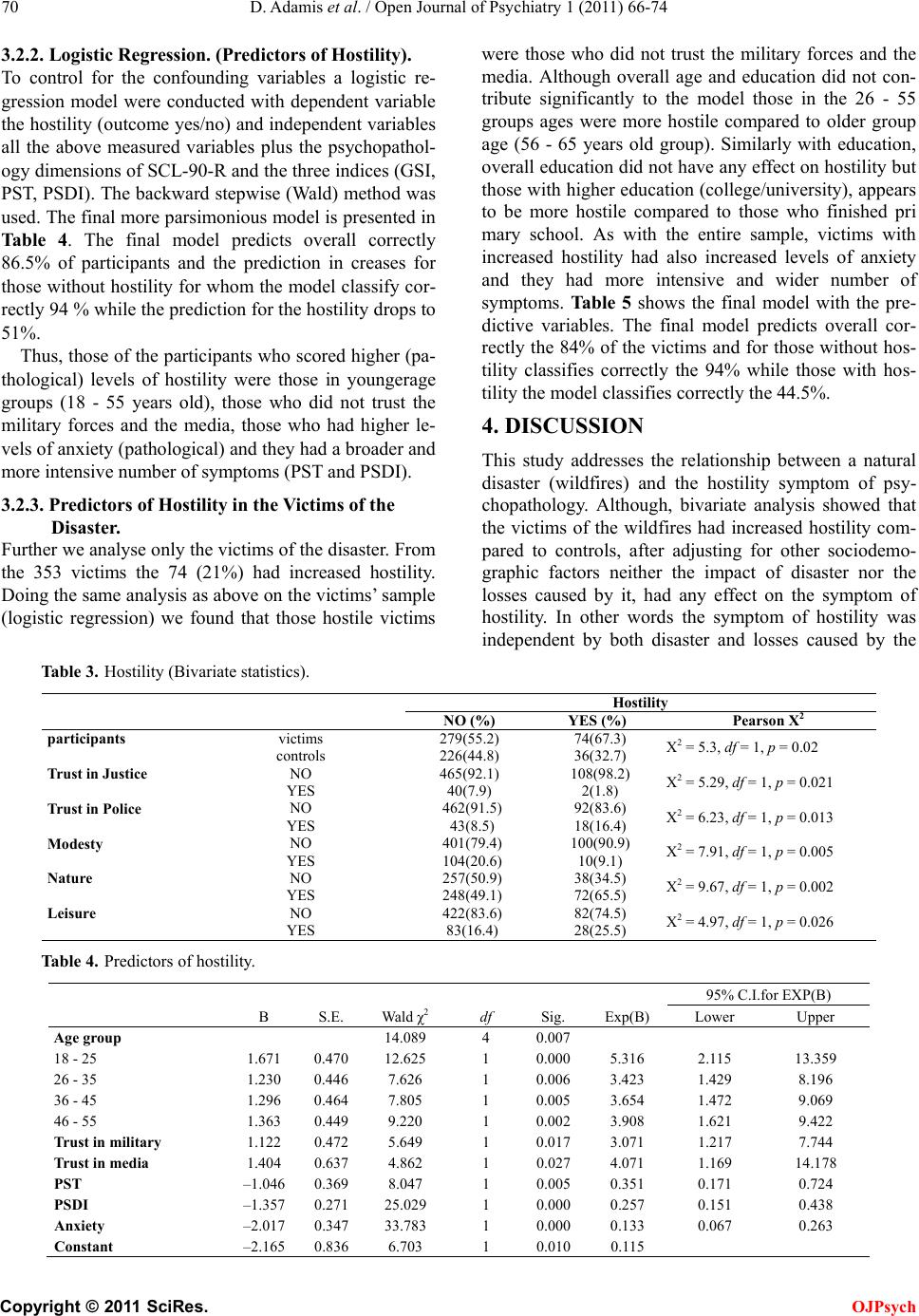

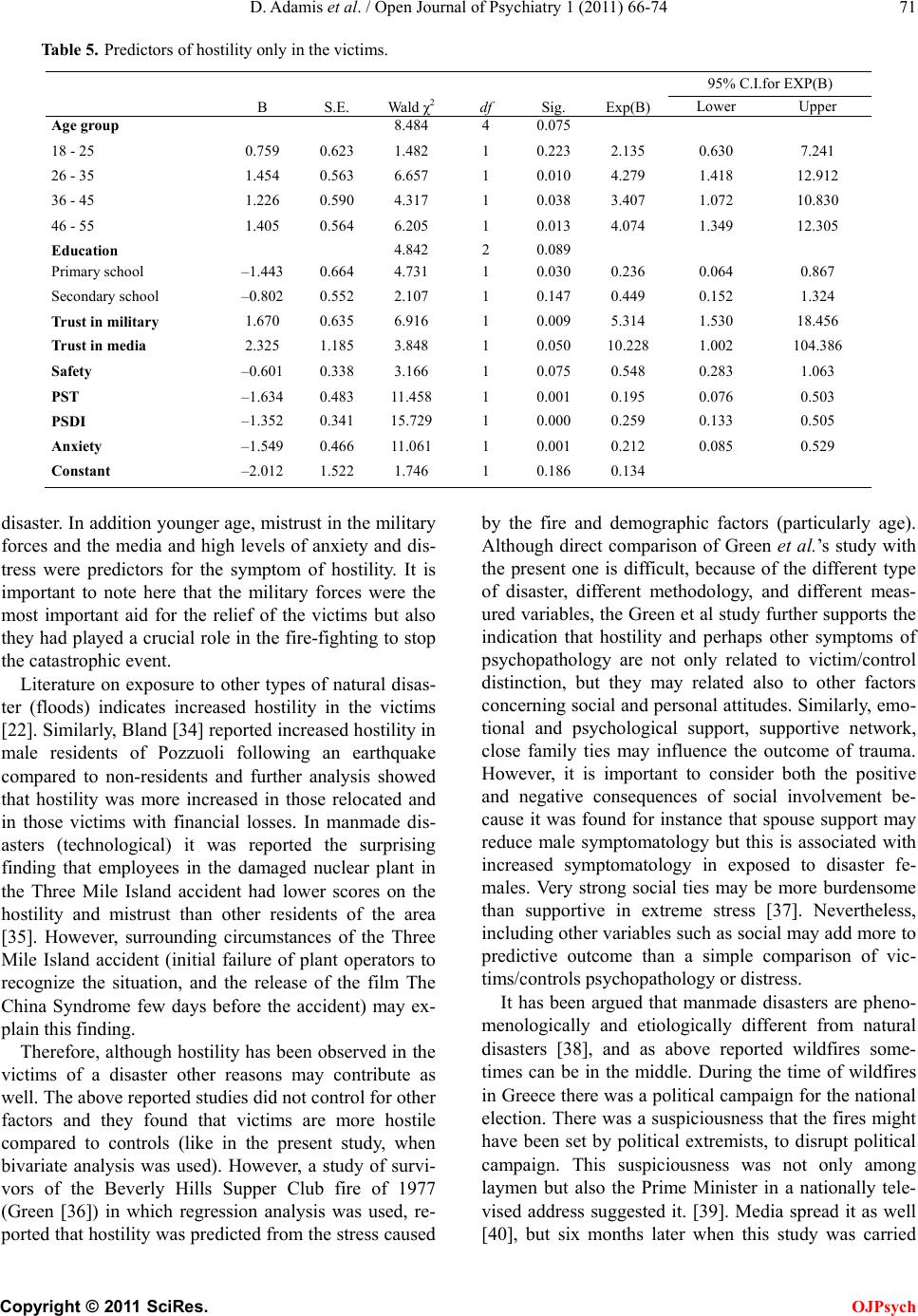

|