Open Journal of Psychiatry, 2011, 1, 56-65 OJPsych doi:10.4236/ojpsych.2011.12009 Published Online July 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJPsych/). Published Onl ine July 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPsych Executive function impairments in high IQ children and adolescents with ADHD Thomas Edwa rds Brown, Philipp Christian Reichel, Donald Michael Quinlan Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, U.S.A. E-mail: thomas.e.brown@yale.edu Received 7 June 2011; revised 1 July 2011; accepted 9 July 2011. ABSTRACT Objective: To demonstrate that high IQ children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD tend to suffer from executive function (EF) impairments that: a) can be identified with a combination of standardized measures and normed self-report data; and b) occur more frequently in this group than in the general population. Method: From charts of 117 children and adolescents aged 6 to 17 years with high IQ ( ≥ 120) who fully met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD, data on 8 normed measures of executive function (EF) were extracted: IQ index scores for working memory and processing speed, a standardized measure of au- ditory verbal memory, and 5 clusters of the Brown ADD Scale, a normed, age-graded rating scale for ADHD-related executive function impairments in daily life. Significant impairment was computed for each individual relative to age-appropriate norms for each measure and comparisons were made to base-line rates in the general population. Results: Sixty-two percent of participants were significantly impaired on at least 5 of these 8 markers of EF. Chi-square com- parisons of scores from these high IQ participants were significantly different (p < 0.001) from standar- dization norms for each of the eight EF measures. Conclusions: High IQ children and adolescents with ADHD, despite their cognitive strengths, tend to suf- fe r f ro m s ignificant impairm ents of exe cutive functions that can be assessed with these measures ; incidence of these impairments is significantly greater than in the general population. These results are fully consistent with data on high IQ adults diagnosed with ADHD. Keywords: ADHD; Executive Functions; High IQ; Working Memory; Processing Speed 1. INTRODUCTION In our clinical practice, often children and adolescents with IQ scores in and above the superior range are brought by their parents for evaluation and treatment of chronic impairments related to symptoms of ADHD. Many of these parents report that they have been told repeatedly by teachers, clinicians and others that their son or daughter was very bright, but doing poorly in school because of chronic problems with inadequate focus, inconsistent effort, insufficient organization, and excessive forgetfulness. When the parents have inquired as to whether these difficulties of their offspring might be due to an attention deficit disorder, many have been told that such problems do not occur among individuals with such high levels of intellectual ability. Clinically, parents of these very bright students report that their son or daughter has always been able to work very effectively on certain tasks in which they have strong personal interest. Yet these students who demon- strate strong motivation and impressive cognitive strengths on those specific tasks that interest them tend to have much greater difficulty than most of their peers in trying to make themselves do homework, studying, and other important tasks that do not, for them, hold the same intense interest. Many of these students had earned grades in the A range throughout most of their schooling, but had been dropping into the low C to D range over the preceding two years. When provided treatment appropri- ate for ADHD, these very bright students often show significant improvement in their ability to work effec- tively while their medication is active. While there are some data showing that groups of children diagnosed with ADHD tend to have lower full-scale IQ scores than children without ADHD [1], other studies demonstrate that high IQ individuals can suffer from this disorder. Katusic, Voight, Colligan, and colleagues [2] reported data from 331 children in a pop- ulation-based birth cohort study. They found core symp- toms and age of onset of ADHD, rates of comorbid learning and psychiatric disorders, rates of substance abuse, and rates of treatment to be similar across 34  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 56-65 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych children with high IQ, 276 with normal IQ and 21 with low IQ who fully met diagnostic criteria for ADHD. Thus far the scientific literature has provided little evi- dence of the nature of the cognitive impairments expe- rienced by persons with high IQ and ADHD and whether those impairments differ significantly from those of oth- ers with ADHD or from t he ge neral pop ulation. One study by Antshel, Faraone, and colleagues [3] described 49 high IQ ( ≥120) children who fully met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD and showed a pattern of cognitive, psychiatric and behavioral features typical of children with average IQ diagnosed with ADHD. They found that these very bright children with ADHD tended to have significant difficulty with schoolwork; 22% had repeated a grade at least once, while only 3% of matched controls had ever been re- tained. These children also had more comorbid psycho- pathology and were more impaired in multiple domains, relative to similarly bright children without ADHD. Moreover, incidence of ADHD among first degree rela- tives of these bright children with ADHD was much higher (22.9%) than among such relatives of matched controls (5.6%). Antshel et al. [3] concluded that the diagnos i s of ADHD can be v a l id in high IQ c hildren. In a follow-up study, Antshel and colleagues [4] demonstrated that over a 4.5 year period high IQ child- ren with ADHD, in comparison to high IQ controls without ADHD, continued to have higher rates of mood, anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders. Participants with ADHD also continued to demonstrate elevated rates of impairment relative to controls across most social, academic and family function domains. The high IQ scores of both groups persisted without significant change over the 4.5 year follow-up period. While studies by Katusic [2] and Antshel [3,4] have demonstrated that high IQ children can fully meet diag- nostic criteria for ADHD, and Antshel has shown that high IQ students demonstrate significant problems in their schoolwork, those studies did not identify specific cognitive functions underlying academic underachieve- ment of their samples. Over the past decade there has been increasing recog- nition that symptoms of ADHD enumerated in the DSM-IV-TR constitute a syndrome of developmental impairments of self-regulation that overlap with the concept of Executive Function [5-10], a term that refers to activities of a variety of brain circuits that prioritize, integrate and regulate other cognitive functions. Miyake, Friedman, et al. [11] described EF as general purpose control mechanisms that modulate operation of various cognitive subprocesses and thereby regulate the dynam- ics of human cognition. These functions develop slowly over the first two decades of life to manage the brain’s cognitive functions and provide the mechanism for the multiple aspects of “self-regulation” in daily life [12,13]. ADHD increasingly is being recognized as essentially developmental impairment of these self-regulatory func- tions. EF impairments are not equivalent to overall impair- ments of cognition measured by standard tests of IQ. Delis and colleagues [14] did a large scale correlational study between measures of EF and measures of IQ using data from 470 normal functioning children and adoles- cents. Their data demonstrated that IQ and EF skills are divergent cognitive domains and that IQ tests do not provide a sufficient or comprehensive assessment of higher-level executive functions. IQ measu res accounted for only 0% to 18% of the variance on variou s measures of EF administered in that study. Similar conclusions about the inadequacies of IQ tests for assessing EF were reported by Ardila, Pineda and Rosselli in their study of 50 students’ ages 13 to 16 years [15]. This view of IQ and EF as independent of one another is also supported by data from Rommelse, Altink, et al [16] whose large study of children with ADHD vs. con- trols found that group differences on EF were not ex- plained by group differences on IQ and vice versa. In principal components analysis that study also demon- strated that EF and IQ are relatively independent of each other in the same child. This is co nsistent with the argu- ment of Schuck and Crinella [17] that children with ADHD do not necessarily have low IQ; they demon- strated that correlations between EF measures and IQ scores account for less than 5% of the variance. Many studies, e.g. Seidman [18-20]; Doyle and col- leagues [21,22]; Martinussen and Hayden [23]; Mar ti- nussen and Tannock [24]; McInnes, Humphries, et al, [25]; Quinlan and Brown [26]; Shanahan, Pennington, et al,[27]; Bedard [28] and Rapport, et al. [29] have re- ported that children and adolescents with ADHD tend to show impairments of executive functions (EF) such as working memory, processing speed, and auditory verbal memory. Yet these studies have not addressed whether those with ADHD and high IQ manifest such weak- nesses. Seidman [18-20] and Doyle and colleagues [21,22] used neuropsychological measures of EF to assess im- pairments of executive function in children and adoles- cents with ADHD. They found that about 30% of child- ren and adolescents in their ADHD sample were signifi- cantly impaired on traditional neuropsychological tests of EF. They concluded that psychometrically defined impairments of EF should be considered a comorbid problem that is present in about one third of individuals with ADHD, a comorbidity that compounds the already compromised school functioning of children and ado-  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 56-65 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych lescents with ADHD. While such findings from neuropsychological “tests of EF” clearly identify individuals who suffer from severe impairments of EF, it is not clear that such tests are suf- ficiently sensitive to pick up the full range of EF im- pairments that are characteristic of individuals with ADHD. Investigators of executive functions in the el- derly [30,31] and some researchers in ADHD [6-10] have argued that the complex, multifaceted nature of executive functions is such that traditional neuropsy- chological “tests of EF” are not valid measures of EF impairments, because they “fractionate” these integrative functions, are too situationally specific, and have too low a ceiling to be sufficiently sensitive. They argue that clinical interview and rating scale data provide more adequate measures of the w ide range of EF impairments found in persons with ADHD. This may be particularly relevant among those with higher IQ. In a sample of adults with ADHD, Biederman, et al. [32] demonstrated that neuropsychological testing of EF identified individ- uals with relatively lower IQ and ach ievemen t test scores, while questionnaire-based assessments of EF impair- ments identified adults with higher levels of ADHD symptoms, psychiatric comorbidity and interpersonal deficits. Limitations of neuropsychological “tests of EF” were shown by Shallice and Burgess [33] who demonstrated that patients with frontal lobe damage were unable ade- quately to perform everyday errands that required plan- ning and multi-tasking, even though they achieved av- erage or well-above-average scores on traditional neu- ropsychological tests of language, memory, perception, and “executive functions.” Similar results from assessing EF impairments in “real life” situ ations wer e reported by Alderman and others [34] who assessed adults doing tasks in a shopping mall. Wilcutt, et al. [35] reviewed published studies and found that current neuropsycho- logical tests are not sensitive enough to pick up ADHD symptoms in children or adolescents. Brown [10] and Barkley [7] have summarized theoretical and practical issues underlying these conflicting views of EF in ADHD. They argue that all individuals with ADHD suf- fer from impaired EF that ADHD is essentially deve- lopmental impairment of EF. Most studies of EF impairments, however measured, in those with ADHD have involved participants with a wide range of IQ. They did not address the issue of whether individuals with ADHD and high IQ demon- strate the same problems of EF as do those in the wider range of IQ scores. Most of these other studies, includ- ing Antshel, et al., [3,4] did not administer a full IQ test to their subjects; they estimated IQ from just a few key subtests. This method is adequate for estimation of over- all cognitive abilities, but it does not provide data ne- cessary for comparing various combinations of subtests useful for assessment of a person’s relative strengths and weaknesses in cognitive abilities. The study reported here used a combination of stan- dardized measures and rating scale data to test the hypo- thesis that children and adolescents with high IQ ( ≥ 120) diagnosed with ADHD suffer from executive function (EF) impairments that: 1) can be identified with a com- bination of standardized measures and rating scale data; and 2) tend to occur more commonly in this group than in the gene ra l population. 2. METHODS 2.1. Sample After approval from the Human Investigations Commit- tee of Yale University, charts of all children and adoles- cents who came during a four year period for evaluation in either of two ADHD clinics, one private, another in a university medical center, were reviewed to select every patient aged 6 to 17 years diagnosed with DSM-IV ADHD, any type, who had high IQ as defined by WISC III/IV [36,37] or WAIS-III [38] index scores for Verbal Comprehension (VCI) and/or Perceptual Organiza- tion/Perceptual Reasoning (POI) ≥120 (top 9% of popu- lation). These index scores were selected because they are measures of overall cognitive abilities less sensitive to cognitive impairments associated with EF. Full-scale IQ scores and factor scores for Verbal and Performance IQ on these Wechsler tests would be less valid because they incorporate several subtests that assess working memory and processing speed, aspects of EF. Charts of all patients between the ages of 6 years and 17 years diagnosed with ADHD and scoring at o r above the ≥120 cutoff for VCI or POI were included. Of the obtained 117 patients, 75% were male. ADHD diagnosis for these patients had been made on the basis of school reports and extended clinical interviews with parents and child. Each fully met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD. Subtype classification, based on current im- pairments, was 62% Predominantly Inattentive Typ e and 38% Combined Type. Within the sample 26% were aged 6 to 11 years, 24%; 12 to 15 years, and 50% were 16 - 17 years. A significant percentage of our sample of high IQ youths with ADHD also currently met diagnostic criteria for one or more additional psychiatric disorders. Most frequent comorbidities were anxiety disorders 25%, dysthymia or unipolar depression 21%, and specific learning disorders 18%. Other disorders occurring in more than 5% of the sample included obsessive compul- sive disorder 15%, Asperger ’s disorder 11%, opposition- al defiant disorder 10% and cannabis abuse 9%. No cur-  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 56-65 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych rent comorbidities were found in 39% of the sample while 37% met diagnostic criteria for one additional di s- order; 16% for two, and 8% for three or more comorbid- ities. Cannabis abuse was found only in youths who were 14 years or older. No patients with psychosis, bi- polar disorder, or autism were included. 2.2. Measures This study assessed charts of children and adolescents with high IQ who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD to determine their relative impairment on stan- dardized measures of 3 executive functions: working memory, processing speed, and short-term auditory ver- bal memory, and on 5 clusters of EF assessed by parental report (6 to 12 year olds) or self-report (12 to 17 year olds) on the Brown ADD Scales, normed rating scales for ADHD-related impairments of EF. Each patient had been evaluated in a two hour clinical interview by a licensed clinical ps ychologis t exper ienced in assessing ADHD. During this interview the Brown ADD Scale for Children or Adolescents [39,40] and Story Memory Test of the Children’s Memory Scales [41] or Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Third Edition [42] were administered. Diagnosis of ADHD was made according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. In a separate session the age-appropriate ve rsion of the full Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - Third or Fourth Edition [36,37], or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition [38] was administered to each subject according to published guidelines. Two index scores from the Wechsler IQ test, Working Memory (WMI) and Processing Speed (PSI), were se- lected to assess participants’ ability to hold in mind and manipulate numerical information (WMI) and to scan and output visual information under timed conditions (PSI). In a sample of 678 children aged 6 to 16 years diagnosed with ADHD, Mayes and Calhoun found that these two index scores of the WISC-III/WISC-IV were the most powerful predictors of academic impairment [43]. Seidman has argued that these two index scores are most likely to be impaired in adults with ADHD [44]. Rather than to compare group means on these mea s- ures, this study compared each individual participant’s WMI and PSI with the stronger of that individual’s VCI or POI index scores on the Wechsler IQ test adminis- tered. Kaufman and Lichtenberger [45] have recom- mended a similar individual profile analysis approach as a valid and useful way to compare the individual’s cog- nitive strengths against measures of executive functions necessary to deploy those strengths. Working memory is not a unitary variable; different working memory functions are associated with different modalities and different types of information [28,29,46]. Often working memory is assessed with the Digit Span test which is not always sensitive to impairments of working memory for more complex verbal information. Quinlan and Brown [26] demonstrated that ADHD adults, in comparison to the general population, tend to be impaired in their ability to recall two brief stories immediately after hearing each one; that sample of ADHD adults also showed greater impairment for recall of the complex narrative content of the stories than on recall of strings of digits, a component of the WAIS-III Working Memory Index. For this present study of children and adolescents w ith both ADHD and high IQ, we asked each subject to listen to each of the two age-appropriate stories of the Child- ren’s Memory Scale [42] or the WMS-III Logical Mem- ory subtest [43] and then scored their immediate recall of each according to scoring guidelines described by Quinlan and Brown [26]. The resulting score was then transformed to an IQ-like score (mean of 100, SD of 15) which was then subtracted from that individual’s VCI index score on the Wechsler IQ test. In this way we cor- rected for the correlation between overall verbal ability and the person’s recall of the stories. This correction is necessary because the national standardization sample for the WMS-III [43] found a .58 correlation between immediate auditory memory and Verbal IQ. To obtain a more comprehensive measure of each par- ticipant’s EF impairment in multiple activities of daily life, the clinician administered the Brown ADD Scale [33,34] orally to each parent (for children aged 6 to 11 years) or to the patient (for ages 12 to 17 years) during the initial evaluation. This normed and validated scale elicits parental report and/or self-report data regarding 5 clusters of ADHD-related EF. These include: 1) Organizing, prioritizing and activating to work 2) Focusing, sustaining and shifting attention to tasks 3) Regulating alertness, sustaining effort, and processing speed 4) Managing frustra t ion and modulat i ng emotion s 5) Utilizing working memory and accessing recall Rather than to merge data from all of these clusters into one total score, we treated each cluster as a separate item. This provided a more detailed profile of each sub- ject’s reported level of EF impairment on each of these five clusters. With these data we determined each subject’s relative impairment on standardized measures of 3 executive functions: working memory, processing speed, and short-term auditory verbal memory, and on 5 clusters of executive functions assessed with the Brown ADD Scale for Children [41] for ages 6 to 12 years or the Brown ADD Scale for Adolescents [40] for ages 13 to 17 years, normed and validated rating scales for ADHD-related  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 56-65 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych imp a i rments of executive functions in daily life. 2.3. Data Analysis From the chart of each individual entered in this study, we extracted scores for the three standardized measures and the 5 clusters of self-report data described above. This yielded 8 different measures of EF. For each meas- ure we had defined a specific cut score to be taken as indication of significant impairment and a higher cut score to serve as a marker of severe impairment. Each patient’s Wechsler I Q test index score for Verbal Comprehension (VCI) or Perceptual Organization (POI) (whichever was higher) was compared against his index scores for working memory (WMI) and processing speed (PSI) on the same test. An index score for working memory or processing speed 1 SD (15 points or more) lower than that individual’s VCI or PSI was considered a marker for significant impairment; 2 SD was considered a marker for severe impairment. Each patient’s score on the standardized story memory test (Children’s Memory Scale or Logical Memory sub- test from the WMS-III) was compared with his VCI. A story memory score 1 SD (15 points or more) lower than that individual’s VCI was considered a marker for sig- nificant impairment; 2 SD was taken as indicating severe imp a i rment. Each patient’s cluster scores on the Brown ADD Scales were compared with the scale’s published norms for that age group to determine degree of impairment reported for that specific cluster of ADHD-related EF. A T- Score of 65 or greater, 1.5 SD above the mean, was taken as indicative of significan t impair ment. Results were calculated in two ways. First, we deter- mined how many of our 8 EF measures were impaired in each of these high IQ participants with ADHD. While we did not expect that each individual would be im- paired on every one of these measures, we predicted that most would be impaired on 5 or more of the eight meas- ures. Our second analysis of the data involved comparisons between the percentage of our high IQ participants with ADHD scoring in the impaired range on each of our 8 measures of EF relative to percentage rates of compara- ble impairment in standardization groups for the respec- tive measures. For the two index scores from the WISC-III/IV and WAIS-III published data allowed us to compare with general population norms for the same age in the same IQ range, ≥120. Use of these norms provided an answer to the question of whether discrepancies ob- tained between verbal comprehension and or perceptual reasoning index scores vs. working memory and processing speed index scores are attributable to ADHD or are found in the general population of children in this age group who score in the superior range of IQ. For the Children’s Memory Scale and the WMS-III story memory task and the Brown ADD Scale for Child- ren and the Brown ADD Scale for Adolescents, we used age-based norms for the general population because separate norms for those with superior IQ were not available. To assess the ADHD participants’ rate of significant or extreme impairment on the eight measures of executive function, Chi-square tests were calculated by using the rate found in the standardization samples as the expected value and the observed rate in the ADHD sample as the observed value. This method was chosen because the number of participants in the various standardization samples was larger than our sample, and was different in number from one measure to the other. 3. RESULTS All patients in this study were selected because they demonstrated cognitive strengths on verbal and/or per- ceptual factors of the Wechsler IQ tests that placed them in the top 9% of their age group in the general popula- tion. Significant impairment on the Working Memory Index was found in over 74% while severe impairment was found in 40% (Figure 1). Processing Speed Index was significantly impaired in over 80% and was severely impaired in more than 42% (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows that over 88% showed significant impairment on their Story Memory Index relative to their high Verbal Comprehension Index on the Wechsler IQ test while over 37% were severely impaired. Analy- sisof each patient’s scores on the Brown ADD Scale in dicated that more than 64% of patients had significant Figure 1. Percentage of high IQ participants significantly im- paired or severely impaired on working memory index vs. VCI or PRI with comparison to typically developing high IQ stu- dents.  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 56-65 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych Figure 2. Percentage of high IQ participants significantly im- paired or severely impaired on processing speed index vs. VCI or PRI with comparison to typically developing high IQ stu- dents. Figure 3. Percentage of high IQ participants significantly im- paired or severely impaired on story memory index vs. VCI with comparison to typically developing students reported impairment on at least 4 of 5 clusters of symp- toms on the Brown ADD Scale (Figure 4). Figures 1-4 also show the percentage of individuals within similar age groups in the general population who score at similar levels of impairment, as reflected in published norms for these measures. For the two Wech- sler IQ test index scores, comparisons are with others whose IQ was ≥120. For scores on the Children’s Mem- ory Scale, WMS-III Logical Memory and the Brown ADD Scales, comparisons were made to the general population of children sampled for published age norms of those specific measures. Figure 4. Percentage of high IQ participants with T-scores ≥ 65 on clusters of the Brown ADD Scale with comparison to typi- cally developing students. On all 8 measures of EF assessed in this study, the percentage of patients impaired was very significantly greater than percentage impaired in relevant standardiza- tion samples for these measures (Figure 1-4). Tab le s 1 and 2 show that each of the eight chi-square values was significant at (p < 0.001). Even with correction for number of tests, the occurrence of EF disruption was significantly greater in the ADHD samples than in the standardization samples. Moreover, despite their high IQ, 62% of these very bright children and adolescents showed significant im- pairment in 5 or more of the 8 markers of EF impairment. These multiple measures converge to indicate that this sample of youths with ADHD and high IQ showed sig- nificant impairment on multiple measures of EF, despite high IQ 4. DISCUSSION These data provide evidence that among children and adolescents with high IQ are some who fully meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD. This study can- not provide any estimate of what percentage of persons with high IQ have ADHD, but it clearly demonstrates that having high IQ does not preclude the possibility that one might have ADHD. We found strong support for the hypothesis that youths with high IQ who meet diagnostic criteria for ADHD tend to have significant weaknesses in working memory, processing speed, and auditory verbal working memory relative to their own cognitive ab ilities and that they tend to report more impairments in executive func tions (EF) than are reported for a comparable age group in the general population. While some of these relative imp a i rments may be within the average range of scores on an absolute scale, they represent significant difficul- ties for these very bright individuals who tend to have great difficulty in achieving at the academic level gener- ally expected from those with such high overall cogni- tive abilities. Our analysis of the percentage of individ u-  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 56-65 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych Table 1. Expected vs. obtained numbers of participants scoring ≥1 or 2 SD on cognitive tasks.*Chi-Square (df = 1) all p < 0.001. Variable Number+ Number– Expected+ Expected– Chi-Square (corrected)* Working Memory Index 1SD 87 30 43 74 67.99 2SD 47 70 6 111 158.81 Processing Speed Index 1SD 94 23 31 86 168.48 2SD 49 68 10 107 157.90 Story Memory Index 1SD 103 14 29 88 244.32 Table 2. Expected vs. obtained numbers of participants scoring t = ≥ 65 on BADDS. *Chi-Square (df = 1) all p < 0.001. BADDS clusters Number + Number – Expected + Expected – (Corrected)* Effort 77 40 7 11 0 723.42 als with these impairments may be a more useful meas- ure for clinicians than group means because group means tend to submerge individual variabilities. Data in this study regarding impairments of auditory verbal memory in youths with ADHD are fully consis- tent with findings from the study by Quinlan and Brown [26] of 176 adults with ADHD whose IQ scores spanned the full normal range. This suggests that that children and adolescents with high IQ diagnosed with ADHD suffer from similar impairments of executive function, at least for auditory verbal memory, as do adults with ADHD on the wider spectrum of IQ scores. Our findings in this study of children and adolescents with high IQ are fully consistent with those of our pre- viously published study of 157 adults with high IQ and ADHD in which the same measures and methods were utilized [47]. High IQ clearly does not protect individu- als in childhood, adolescence or adulthood from having impairments of ADHD. Despite the elevated percentages of high IQ youths with ADHD impaired on these measures, the measures used in this study cannot be considered sufficient, singly or in combination, to make or rule out a diagnosis of ADHD. There are some with ADHD and high IQ who are not significantly impaired on these measures, and there are some impaired on these measures who do not qualify for a diagnosis of ADHD. Yet these measures, when combined with adequate clinical interview data and additional relevant information, may provide useful evidence to assist in identifying youths suffering from EF impairments of ADHD, particularly those w hos e high IQ may make their ADHD impairments more difficult to recognize. Clinical interviews w ith these youths and their par ents indicated that children and adolescents with high IQ who have ADHD may be at increased risk of having recogni- tion and treatment of their ADHD symptoms delayed until relatively late in their educational careers because teachers and parents tend to blame the student’s disap- pointing academic performance on boredom or laziness. Many parents of these high IQ youths reported that situational variability of their offspring’s inattention symptoms was the primary reason for their ADHD im- pairments not being recognized earlier. Like most others with ADHD, these individuals all have a few specific domains in which they have always been able to focus very well, e.g. sports, computer games, artistic or musi- cal pursuits, reading self-selected materials, etc. Parents and teachers tended to assume that these very bright children, could focus on any other tasks equally well, if only they chose to do so [8]. Many parents also reported that their bright offspring with ADHD often demonstrated considerable prowess in performing specific tasks in which they had little posi- tive personal interest, when they experienced considera- ble fear of immediate negative consequences if they did not complete that particular task by some imminent deadline. Adolescent patients often described this as a character trait, “I’m just a severe procrastinator” or “I always work be s t u nder pressure.”  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 56-65 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych Doing well at tasks in which one has strong personal interest, and being unable to begin a task until the very last minute when a harsh deadline immediately looms, are characteristics found in most individuals with ADHD [8], but such traits can be especially problematic for high IQ individuals with ADHD. When these very bright in- dividuals with ADHD often do very well on tasks they enjoy and/or when they are seriously “under the gun,” those who know them are especially likely to see their ADHD impairments in other situations as under volun- tary control. The assumption that such self-management can readi- ly be shaped by conscious intentions is being challenged by a number of studies demonstrating that cognitive self-control tends to operate in an extremely rapid, au- tomatized manner, largely under the influence of less conscious emotional and cognitive motivational processes [48-50]. Research is needed to test how these automatized processes are related to executive function impairments associated with ADHD. For most of these high IQ youths with ADHD, it was not until relatively late in their school years that their EF impairments significantly interfered with their ability to perform well. During early school years, many had been placed in special classes or programs for talented and gifted students, only to be removed eventually from these programs as they failed to keep up with work re- quirements in these more demanding classes. For many, such failures and loss of status caused escalating demo- ralization as they progressed through their elementary and secon da r y s c hooling. A number of the high IQ adolescent students in this study were not evaluated for ADHD until their high school years. Half of our sample were 16 or 17 years old at the time of their first evaluation. Many of these stu- dents reported that during elementary school years they were able to function in ways that lived up to high ex- pectations for academic success that were held by their parents, their teachers and themselves. As was found in the study of Langberg, et al., [51], it was in secondary school settings where they had to keep track of various homework assignments for many different teachers, without anyone to help them to prioritize and reme mb er, that ADHD impairments of these individuals became apparent. Some might question the validity of an ADHD diag- nosis for individuals who do not manifest symptoms of the disorder before age 7 years as stipulated by the DSM-IV. Yet Faraone and colleagues [52] have demon- strated that adults whose ADHD does not become ap- parent until well past the DSM-IV stipulated age of on- set at 7 years do not differ in functional impairment, psychiatric comorbidity or family transmission of ADHD when compared to adults whose ADHD symp- toms were apparent by age 7. High IQ individuals with ADHD may be at particular risk of protracted delays in having their ADHD impairments recognized, evaluated and treated, during which time they are likely to be blam e d and p u nished for their ADHD impairments. To our knowledge, this is, thus far, the largest sample of high IQ children and adolescents with ADHD in the published literature and the only one that utilized full IQ tests. Our sample includes a wide range of ages, from 6 years to 17 years, a range over which progressive de- velopment of EF is expected. It should be noted, howev- er, that each measure used in the study utilized age-corrected norms, thus each participant was com- pared with others of the same age and, in the case of the IQ index scores, others of the same age and with the same high level of IQ. 5. CONCLUSIONS This study demonstrates that individuals with high IQ can fully meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD and that they tend to suffer significant impairments on executive functions measured by three standardized tests and five separate clusters of a normed self-report scale. Our data are reported in percentages of participants who scored above or below the stipulated score cut-points. We believe that such a presentation provides information that may be more useful to clinicians as- sessing individual children and adolescents than would be group means which may submerge individual differ- ences. Limitations of the study One limitation of this study is that comparisons were made with published age-based norms for the measures used rather than with a matched set of high IQ youths who did not have ADHD. Our data on discrepancies between IQ index scores, however, were compared with national, population-based norms for matched age groups with IQ in the same high range as our sample. Comparisons for our other measures of EF were to age-based normative samples of youths in the general population, not specifically in the same range of IQ. Despite these limitations, this study can serve to alert educators and clinicians to the fact that some children and adolescents with high IQ suffer from ADHD and that their ADHD-related EF impairments can readily be assessed with measures used in this study. Clinicians evaluating high IQ children and adolescents who are underachieving should consider ADHD as a possible diagnosis and utilize appropriate measures to assess re- lated EF impairments. This study also adds to the accu- mulating data to demonstrate that general intelligence is  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 56-65 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych not the same as executive functions; these are separate aspects of integrated cognitive operations which should be evaluated separately. Competing interests Dr. Brown is a consultant for Eli Lilly and Shire; he has received research support from Eli Lilly and Shire and receives royalties from The Psychological Corpora- tion, American Psychiatric Press and Yale University Press. The other authors declare that they have no com- peting interests. REFERENCES [1] Frazier, T.W., H.A. Demaree, et al. (2004). Meta-analysis of intellectual and neuropsychological test performance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropschol- ogy, 18, 543-555. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.18.3.543 [2] Katusic, M .Z., Voight , R. G. , Colligan, R.C., Weaver, A.L. and Homan, K.J., et al. (2011) Attention-deficit hyperac- tivity disorder in children with high intelligence quotient: Results from a population-based study. Journal of Deve- lopmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 32, 103-109. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e318206d700 [3] Antshel, K.M., Faraone, S.V., et al. (2007) Is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder a valid diagnosis in the presence of high IQ? Results from the MGH longitudinal family studies of ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 687-694. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172eecf [4] Antshel, K.M., S.V. Faraone, et al. (2008) Temporal Sta- bility of ADHD in the High-IQ Population: Results from the MGH Longitudinal Family Studies of ADHD. Jour- nal of American Academy Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 817-825. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172eecf [5] Castellanos, F.X. (1999) Psychobiology of ADHD. In: Quay, H.C. and Hogan, A.E. Eds., Handbook of Disrup- tive Behavior Disorders. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Pub- lishers, New York, 179-198. [6] Barkley, R.A. (2006) Attention-deficit hyperactivity dis- order: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. 3th Edi- tion, Guilford Press, New York. [7] Barkley, R.A. (2011) Barkley deficits in executive func- tioning scale (BDEFS). Guilford Press, New York. [8] Brown, T.E. (2005) Attention deficit disorder: The unfo- cused mind in children and adults. Yale University Press, New Haven. [9] Brown, T.E. (2009) Developmental complexities of at- tentional disorders and comorbidities. In Brown T.E. Ed., ADHD comorbidities: Handbook for ADHD complica- tons in children and adults. American Psychiatric Pub- lishing, Inc, Washingt on, 3-22. [10] Brown, T.E. (2006) Executive functions and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Implications of two con- flicting views. International Journal of Disability, De- velopment and Education, 53, 35-46. doi:10.1080/10349120500510024 [11] Miyake, A., Friedman, N.P., Emerson, M.J., Witzki, A.H., et al. (2000) Unity and diversity of executive functions and their contribution to complex ‘frontal lobe’ tasks: A latent variable anal ysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41, 49-100. doi:10.1006/cogp.1999.0734 [12] Eslinger, P.J. (1996) Conceptualizing, Describing, and measuring components of executive function. In G.R. Lyon and N.A. Krasnegor, Eds., Attention, Memory and Executive Function. Paul Brookes Publishing Co., Bal- timore, 367-395. [13] Baumeister, R.F. and Vohs, K.D. Eds., (2004) Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory and applications. Guilford Press, New York. [14] Delis, D.C., Houston, W.S., Wetter, S. Han, S.D., et al. (2007) Creativity lost: The importance of testing execu- tive function in school-age children and adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 25, 291-240. doi:10.1177/0734282906292403 [15] Ardila, A., Pineda, D. and Rosselli, M. (2000) Correla- tion between intelligence test scores and executive func- tion measures. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 15, 31-36. [16] Rommelse, N.N.J., Altink, M.E., Oosterlaan, J., Busch- gens, C.J.M., Buitelaar, J.K. and Sergeant, J. (2008) Support for an independent familial segregation of ex- ecutive and intelligence endophenotypes in ADHD fami- lies. Psychological Medicine, 38, 1595-1606. doi:10.1017/S0033291708002869 [17] Schuck, S.E.B. and Crinella F.M. (2005) Why children with ADHD do not have low IQs. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38, 262-280. doi:10.1097/00004583-199703000-00015 [18] Seidman, L.J., Biederman, J., Faraone, S.V., Weber, W., Mennin, D. and Jones, J. (1997a) A pilot study of neu- ropsychological function in girls with ADHD. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 366-373. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.65.1.150 [19] Seidman, L.J., Biederman, J., Faraone, S.V., Weber, W., and Ouellette, C. (1997b) Toward defining a neuropsy- chology of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder: Per- formance of children and adolescents from a large clini- cally referred sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 150-160. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.15.4.544 [20] Seidman, L.J. (2001) Learning disabilities and executive dysfunction in boys with attention-deficit/hyper-activity disorder. Neuropsychology, 15, 544-556. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.477 [21] Doyle, A.E., Biederman, J., Seidman, L.J., Weber, W. and Faraone, S.V. (2000) Diagnostic efficiency of neuropsy- chological test scores for discriminating boys with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 477-488. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.477 [22] Doyle, A.E., Faraone, S.V., Dupre, E.P., and Biederman, J. (2001) Separating attention deficit hyperactivity dis- order and learning disabilities in girls: A familial risk analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1666-1672. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1666 [23] Martinussen, R., Hayden, J., et al. (2005) A meta-analysis of working memory impairments in children with atten- tion-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 377-384. doi:10.1080/13803390500205700 [24] Martinussen, R. and Tannock, R. (2006) Working mem- ory impairments in children with attention-deficit hyper-  T. E. Brown et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 1 (2011) 56-65 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPsych activity disorder with and without comorbid language learning disorders. Journal Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 28, 1073-1094. doi:10.1080/13803390500205700 [25] McInnes, A., T. Humphries, et al. (2003) Listening com- prehension and working memory are impaired in atten- tion-deficit hyperactivity disorder irrespective of lan- guage impairment. Journal Abnormal Child Psychology, 31, 427-443. doi:10.1177/108705470300600401 [26] Quinlan, D. M. and Brown, T.E. (2003) Assessment of short-term verbal memory impairments in adolescents and adults wi th ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 6, 143-152. doi:10.1177/108705470300600401 [27] Shanahan, M.A., Pennington, B.F., et al. (2006) Processing speed deficits in attention defi- cit/hyperactivity disorder and reading disability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 585-602. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9037-8 [28] Bedard, A.C., Jain, U., Hogg-Johnson, S. and Tannock, R. (2007) Effects of methylphenidate on working memory components: Influence of measurement. Journal of Child Psycholog y and Psychiatry, 48, 872-880. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01760.x [29] Rapport, M., Alderson, R., Kofler, M., Sarver, D., Bolden, J. and Sims, V. (2008) Working memory deficits in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): The contribution of executive and subsystem processes. Journal Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 825-839. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9215-y [30] Rabbitt, P. (1997) Methodologies and models in the study of executive function. In: Rabbitt P. Ed., Methodology of Frontal and Executive Function, Psychology Press Pub- lishers, East Sussex, 1-38. [31] Burgess, P.W. (1997) Theory and methodology in execu- tive function research. In: P. Rabbit Ed., Methodology of Frontal and Executive Function, Psychology Press Pub- lishers, East Sussex, 81-116. [32] Biederman, J., Petty C., et al. (2008) Discordance be- tween psychometric testing and questionnaire-based de- finitions of executive functions in individuals with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 92-102. doi:10.1177/1087054707305111 [33] Shallice, T. and Burgess, P.W. (1991) Deficits in stra tegy application following frontal lobe damage in man. Brain, 114, 727-741. doi:10.1093/brain/114.2.727 [34] Alderman, N., Burgess, P.W., et al. (2003) Ecological validity of a simplified version of the multiple errands shopping test. Journal of the International Neuropsycho- logical Society, 9, 31-44. doi:10.1017/S1355617703910046 [35] Willcutt, E.G., Doyle, A.E. et al. (2005) Validity of the executive function theory of attention deficit hyperactiv- ity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Biological Psychia- try, 57, 1336-1346. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006 [36] Wechsler, D. (1991) Wechsler intelligence scale for children. 3rd Edition, The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [37] Wechsler, D. (2003) Wechsler intelligence scale for children. 4th Edition, The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [38] Wechsler, D. (1997) Wechsler adult intelligence scale. Third Edition, The Psychological Corporation, San An- tonio. [39] Brown, T.E. (1996) Brown attention deficit disorder scales for adolescents and adults. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [40] Brown, T.E. (2001) Brown attention deficit disorder scales for children and adolescents. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [41] Cohen, M.J. (1997) Children’s memory scale manual. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [42] Wechsler, D. (1997) Wechsler memory scale. 3rd Edition, The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio. [43] Mayes, S.D. and Calhoun, S.L. (2007) Wechsler intelli- gence scale for children. 3rd-4th edition, predictors of academic achievement in children with attention defi- cit/hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Quarterly, 22, 234-249. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.22.2.234 [44] Seidman, L.J., Doyle A., et al. (2004) Neuropsychologi- cal function in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 27, 261-282. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2003.12.005 [45] Kaufman, A.S. and Lichtenberger, E.O. (2006) Assessing adolescent and adult intelligence. 3rd Edition, John Wi- ley & Sons, Hoboken. [46] Baddeley, A. (2007) Working memory, thought and ac- tion. Oxford University Press, New York. [47] Brown, T.E., Reichel, P.C. and Quinlan, D.M. (2009) Executive function impairments in high IQ adults with ADHD. Journal of At tention Disor ders, 13, 161-171. doi:10.1177/1087054708326113 [48] Phelps, E. (2005) The interaction of emotion and cogni- tion: The relationship between the human amygdala and cognitive awareness. In: Hassin, R. Uleman J. and Bargh J. A. Eds., The New Unconscious, Oxford University Press, New York, 61-76. [49] Glaser, J. and Kihlstrom, J.F. (2005) Compensatory au- tomaticity: Unconscious volition is not an oxymoron. In: Hassin R., Uleman J. and Bargh J. A. Eds., The New Un- conscious, N ew York, Oxford Uni versity Pr ess, 171-195. [50] Hassin, R.R. (2005) Nonconscious control and implicit working memory. In: Hassin R., Uleman J. and J.A. Bargh Eds., The New Unconscious, Oxford University Press, New York, 196-222. [51] Langberg, J., Epstein, J. N., et al. (2008) The transition to middle school is associated with changes in the deve- lopmental trajectory of ADHD symptomatology in young adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 651-663. [52] Faraone, S., Biederman, J., Spencer, T., Mick, E., Murray, K. Petty, C., et al. (2006) Diagnosing adult attention def- icit hyperactivity disorder: Are late onset and subthre- shold diagnoses valid? American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 1720-1729. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.10.1720

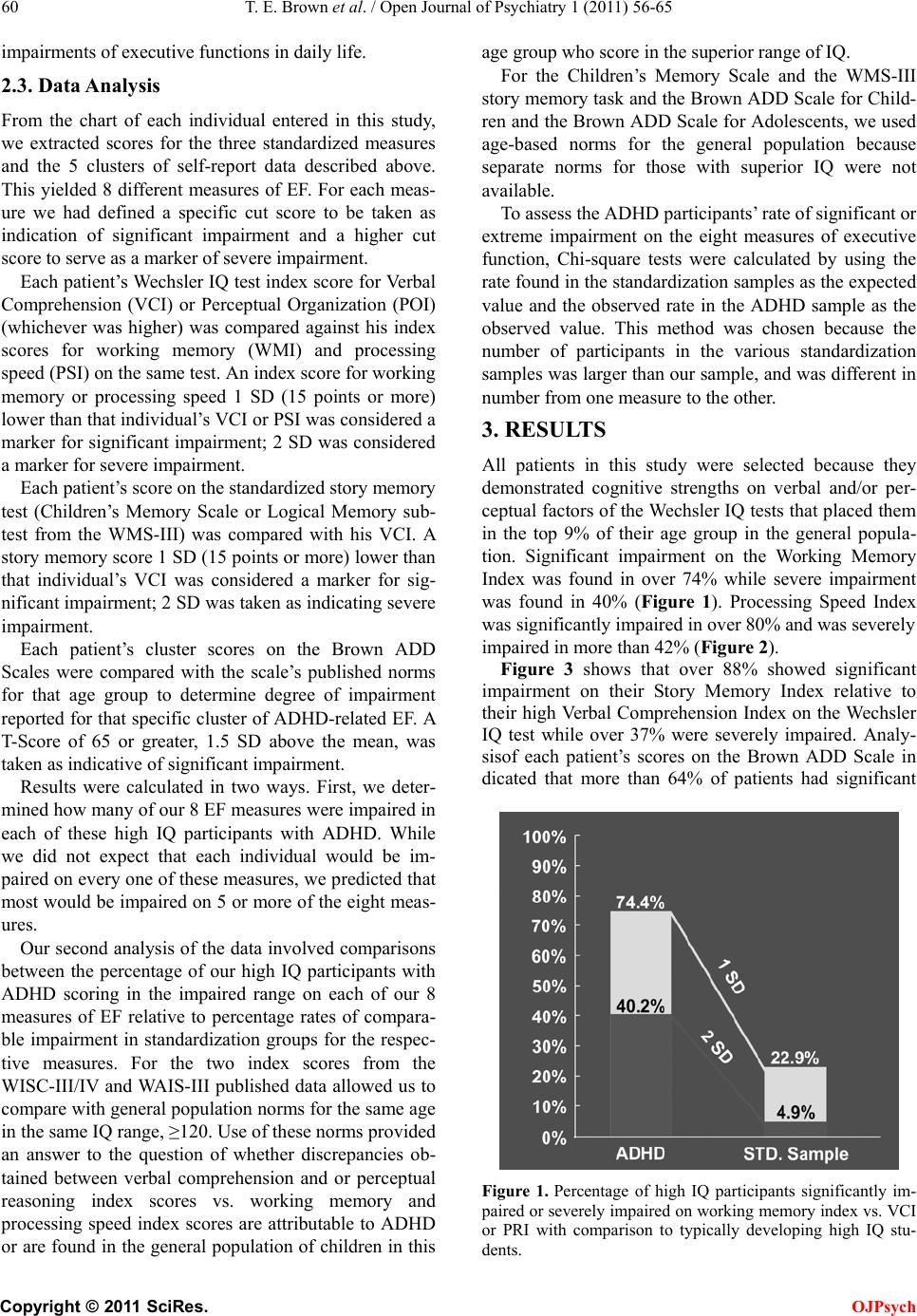

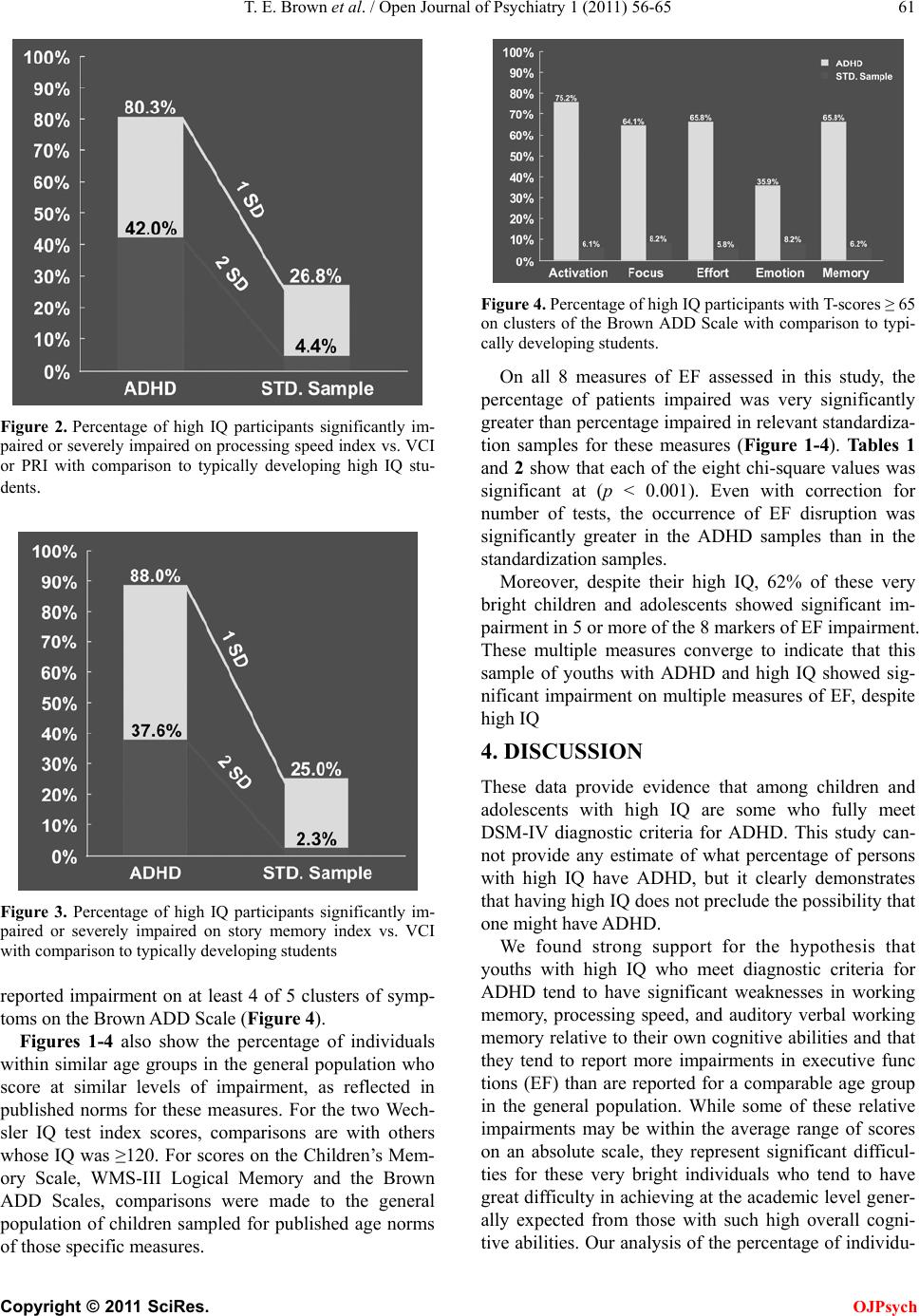

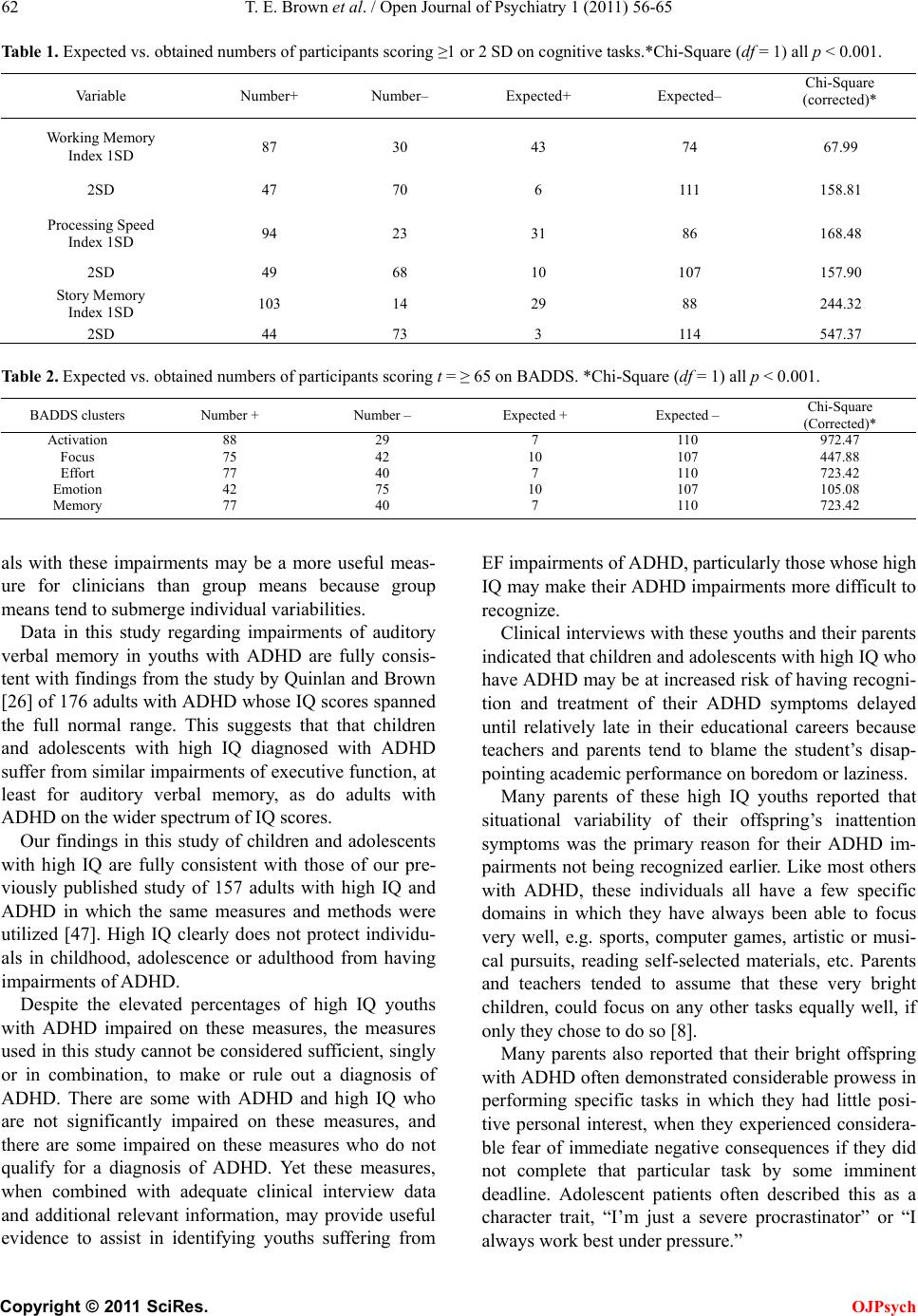

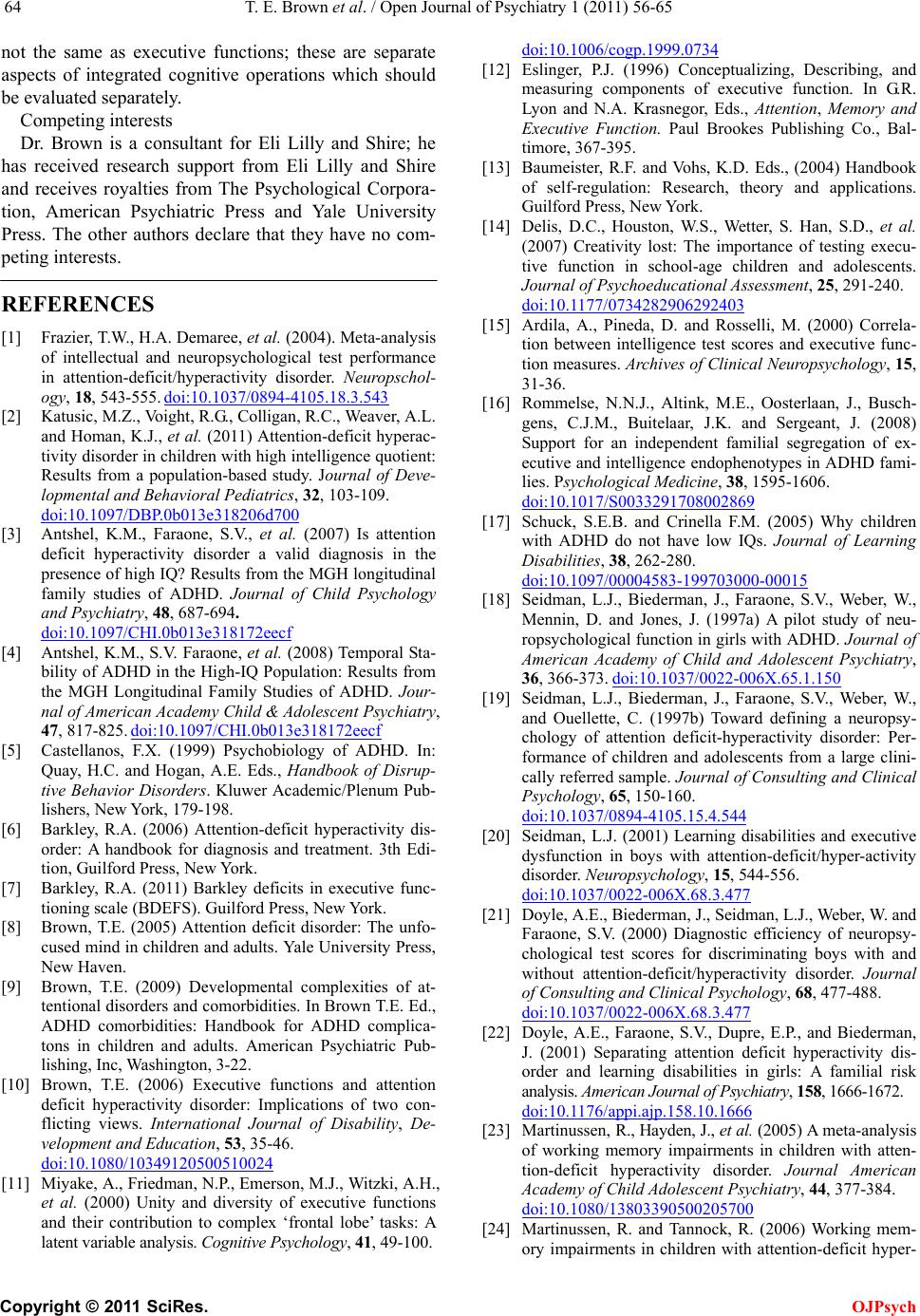

|