Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

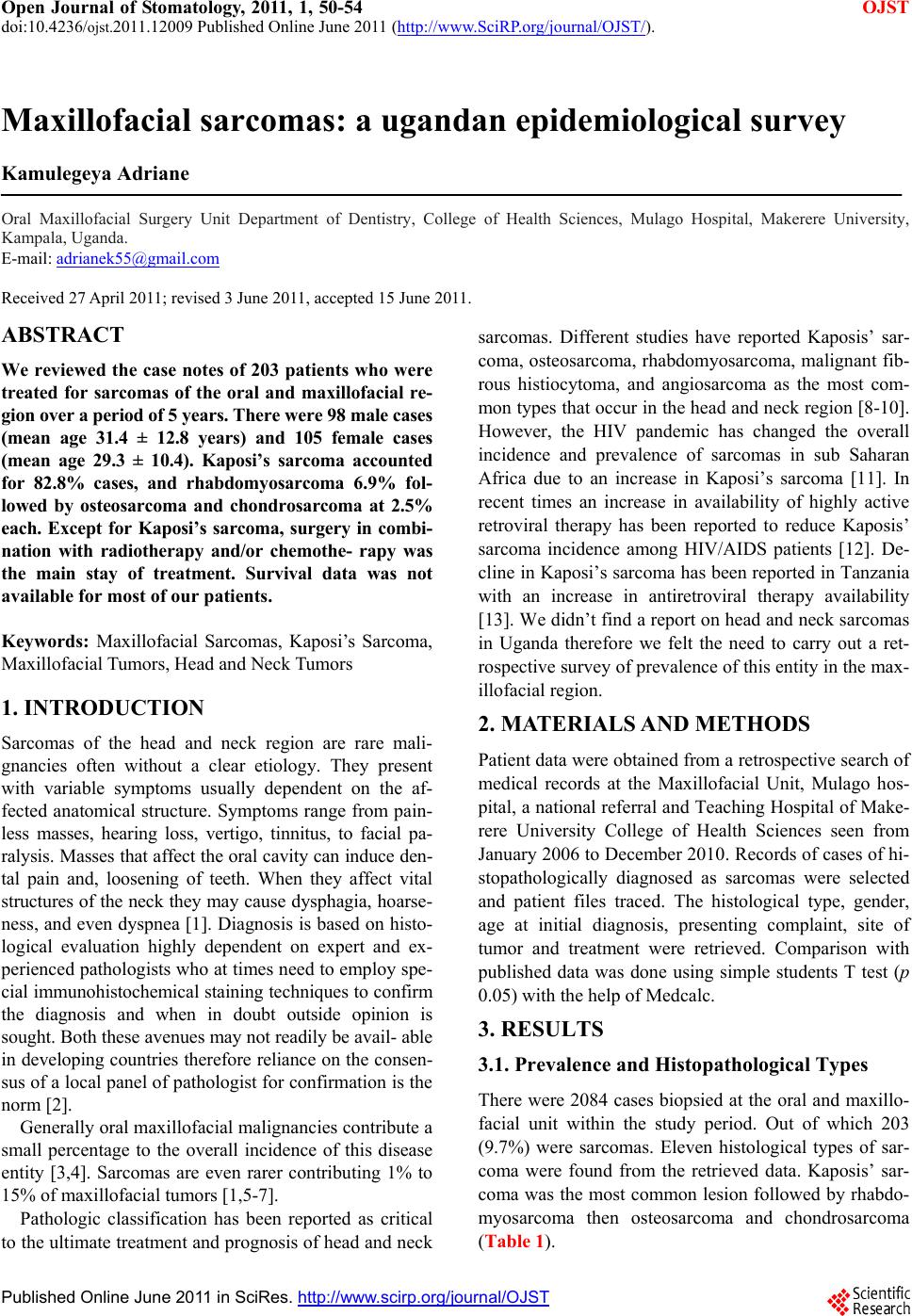

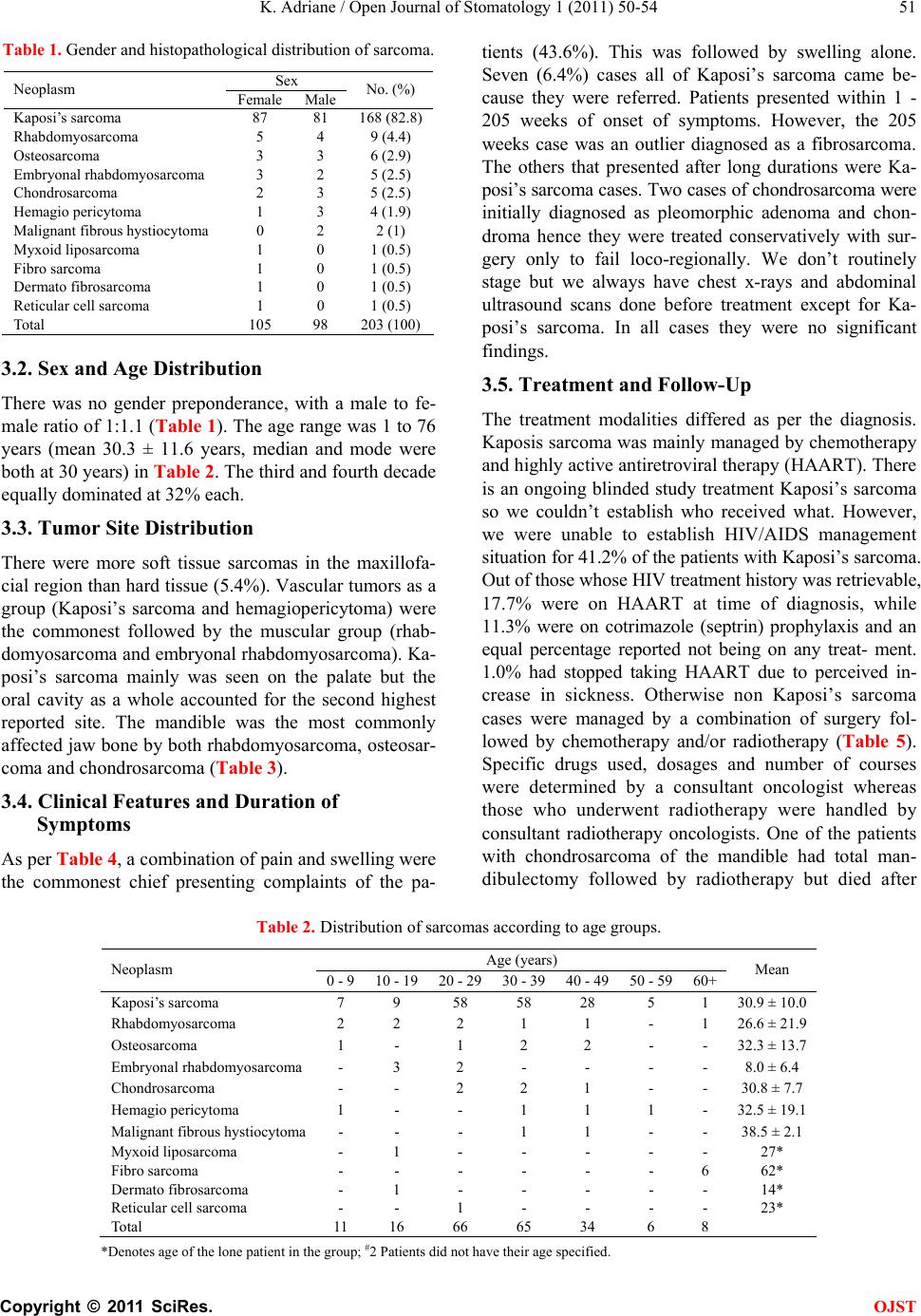

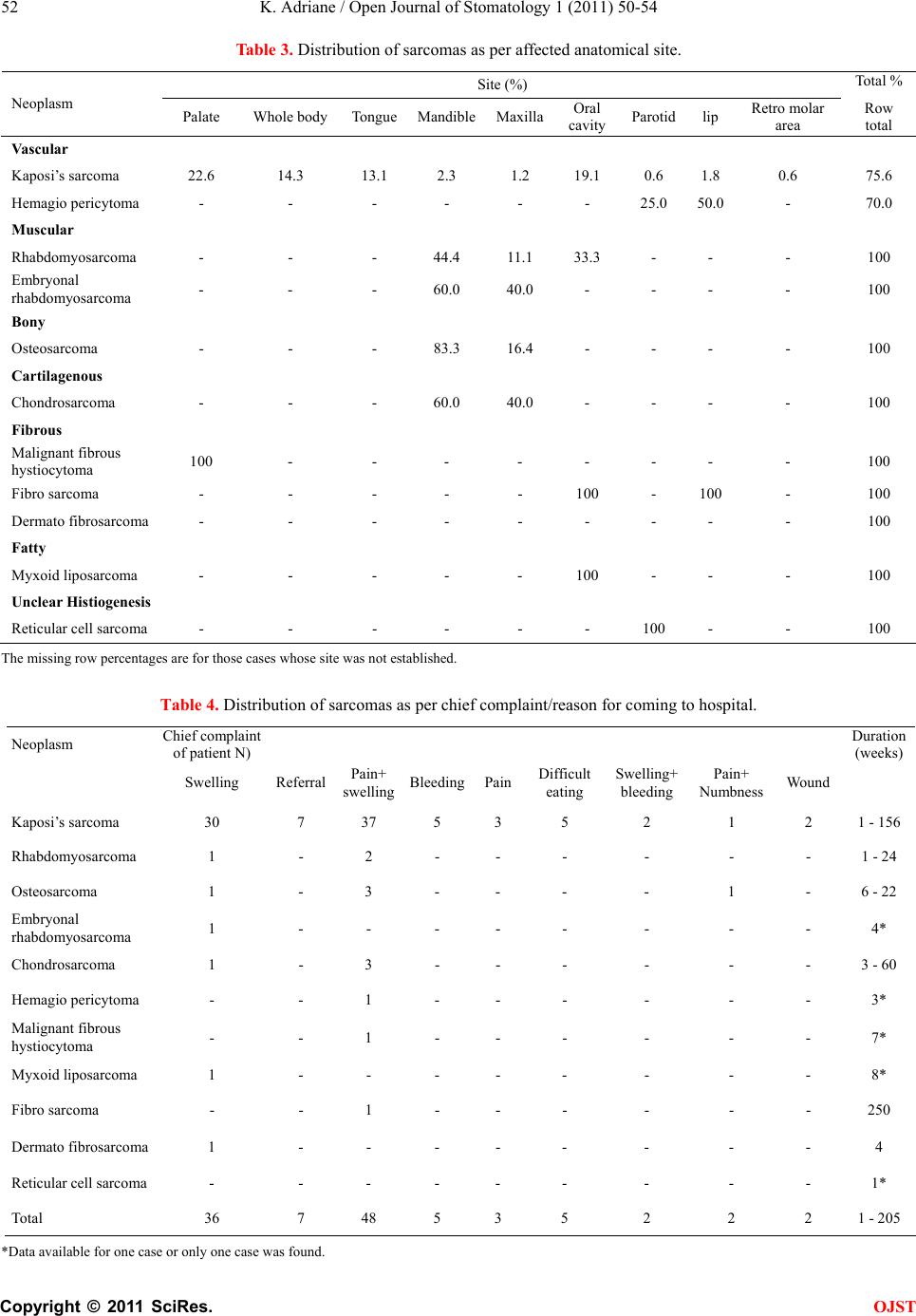

Open Journal of Stomatology, 2011, 1, 50-54 OJST doi:10.4236/ojst.2011.12009 Published Online June 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJST/). Published Online June 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJST Maxillofacial sarcomas: a ugandan epidemiological survey Kamulegeya Adriane Oral Maxillofacial Surgery Unit Department of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, Mulago Hospital, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. E-mail: adrianek55@gmail.com Received 27 April 2011; revised 3 June 2011, accepted 15 June 2011. ABSTRACT We reviewed the case notes of 203 patients who were treated for sarcomas of the oral and maxillofacial re- gion over a period of 5 years. There were 98 male cases (mean age 31.4 ± 12.8 years) and 105 female cases (mean age 29.3 ± 10.4). Kaposi’s sarcoma accounted for 82.8% cases, and rhabdomyosarcoma 6.9% fol- lowed by osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma at 2.5% each. Except for Kaposi’s sarcoma, surgery in combi- nation with radiotherapy and/or chemothe- rapy was the main stay of treatment. Survival data was not available for most of our patients. Keywords: Maxillofacial Sarcomas, Kaposi’s Sarcoma, Maxillofacial Tumors, Head and Neck Tumors 1. INTRODUCTION Sarcomas of the head and neck region are rare mali- gnancies often without a clear etiology. They present with variable symptoms usually dependent on the af- fected anatomical structure. Symptoms range from pain- less masses, hearing loss, vertigo, tinnitus, to facial pa- ralysis. Masses that affect the oral cavity can induce den- tal pain and, loosening of teeth. When they affect vital structures of the neck they may cause dysphagia, hoarse- ness, and even dyspnea [1]. Diagnosis is based on histo- logical evaluation highly dependent on expert and ex- perienced pathologists who at times need to employ spe- cial immunohistochemical staining techniques to confirm the diagnosis and when in doubt outside opinion is sought. Both these avenues may not readily be avail- able in developing countries therefore reliance on the consen- sus of a local panel of pathologist for co nfirmation is the norm [2]. Generally oral maxillofacial malignan cies contribute a small percentage to the overall incidence of this disease entity [3,4]. Sarcomas are even rarer contributing 1% to 15% of maxillofacial tumors [1,5-7]. Pathologic classification has been reported as critical to the ulti mate treatment and prognosis of head and neck sarcomas. Different studies have reported Kaposis’ sar- coma, osteosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, malignan t fib- rous histiocytoma, and angiosarcoma as the most com- mon types that occur in the head and neck region [8-10]. However, the HIV pandemic has changed the overall incidence and prevalence of sarcomas in sub Saharan Africa due to an increase in Kaposi’s sarcoma [11]. In recent times an increase in availability of highly active retroviral therapy has been reported to reduce Kaposis’ sarcoma incidence among HIV/AIDS patients [12]. De- cline in Kaposi’s sarcoma has been reported in Tanzania with an increase in antiretroviral therapy availability [13]. We didn’t find a report on head and neck sarcomas in Uganda therefore we felt the need to carry out a ret- rospective survey o f prevalence of this en tity in the max- illofacial region. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS Patient data were obtained from a retrospective search of medical records at the Maxillofacial Unit, Mulago hos- pital, a national referral and Teaching Hospital of Make- rere University College of Health Sciences seen from January 2006 to December 2010. Records of cases of hi- stopathologically diagnosed as sarcomas were selected and patient files traced. The histological type, gender, age at initial diagnosis, presenting complaint, site of tumor and treatment were retrieved. Comparison with published data was done using simple students T test (p 0.05) with the help of Medcalc. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Prevalence and Histopathological Types There were 2084 cases biopsied at the oral and maxillo- facial unit within the study period. Out of which 203 (9.7%) were sarcomas. Eleven histological types of sar- coma were found from the retrieved data. Kaposis’ sar- coma was the most common lesion followed by rhabdo- myosarcoma then osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma (Table 1).  K. Adriane / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 50-54 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 51 Table 1. Gender and histopathological distribution of sarcoma. Sex Neoplasm Female Male No. (%) Kaposi’s sarcoma 87 81 168 (82.8) Rhabdomyosarcoma 5 4 9 (4.4) Osteosarcoma 3 3 6 (2.9) Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma 3 2 5 (2.5) Chondrosarcoma 2 3 5 (2.5) Hemagio pericytoma 1 3 4 (1.9) Malignant fibrous hystiocytoma 0 2 2 (1) Myxoid liposarcoma 1 0 1 (0.5) Fibro sarcoma 1 0 1 (0.5) Dermato fibrosarcoma 1 0 1 (0.5) Reticular cell sarcoma 1 0 1 (0.5) Total 105 98 203 (100) 3.2. Sex and Age Distribution There was no gender preponderance, with a male to fe- male ratio of 1:1.1 (Table 1). The age range was 1 to 76 years (mean 30.3 ± 11.6 years, median and mode were both at 30 years) in Table 2. The third and fourth decade equally dominated at 32% each. 3.3. Tumor Site Distribution There were more soft tissue sarcomas in the maxillofa- cial region than hard tissue (5.4%). Vascular tumors as a group (Kaposi’s sarcoma and hemagiopericytoma) were the commonest followed by the muscular group (rhab- domyosarcoma and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma). Ka- posi’s sarcoma mainly was seen on the palate but the oral cavity as a whole accounted for the second highest reported site. The mandible was the most commonly affected jaw bone by both rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosar- coma and chondrosarcoma (Table 3). 3.4. Clinical Features and Duration of Symptoms As per Table 4, a combinatio n of p ain and swellin g were the commonest chief presenting complaints of the pa- tients (43.6%). This was followed by swelling alone. Seven (6.4%) cases all of Kaposi’s sarcoma came be- cause they were referred. Patients presented within 1 - 205 weeks of onset of symptoms. However, the 205 weeks case was an outlier diagnosed as a fibrosarcoma. The others that presented after long durations were Ka- posi’s sarcoma cases. Two cases of chondrosarcoma were initially diagnosed as pleomorphic adenoma and chon- droma hence they were treated conservatively with sur- gery only to fail loco-regionally. We don’t routinely stage but we always have chest x-rays and abdominal ultrasound scans done before treatment except for Ka- posi’s sarcoma. In all cases they were no significant findings. 3.5. Treatment and Follow-Up The treatment modalities differed as per the diagnosis. Kaposis sarcoma was mainly managed by chemotherapy and highly active antiretrov iral therap y (HAART). Th ere is an ongoing blinded study treatment Kaposi’s sarcoma so we couldn’t establish who received what. However, we were unable to establish HIV/AIDS management situation for 41.2% of the patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma. Out of those whose HIV treat m e nt hi story was retri evabl e, 17.7% were on HAART at time of diagnosis, while 11.3% were on cotrimazole (septrin) prophylaxis and an equal percentage reported not being on any treat- ment. 1.0% had stopped taking HAART due to perceived in- crease in sickness. Otherwise non Kaposi’s sarcoma cases were managed by a combination of surgery fol- lowed by chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy (Table 5). Specific drugs used, dosages and number of courses were determined by a consultant oncologist whereas those who underwent radiotherapy were handled by consultant radiotherapy oncologists. One of the patients with chondrosarcoma of the mandible had total man- dibulectomy followed by radiotherapy but died after Table 2. Distribution of sarcomas according to age groups. Age (years) Neoplasm 0 - 9 10 - 1920 - 2930 - 3940 - 4950 - 5960+ Mean Kaposi’s sarcoma 7 9 58 58 28 5 1 30.9 ± 10. 0 Rhabdomyosarcoma 2 2 2 1 1 - 1 26.6 ± 21.9 Osteosarcoma 1 - 1 2 2 - - 32.3 ± 13.7 Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma - 3 2 - - - - 8.0 ± 6.4 Chondrosarcoma - - 2 2 1 - - 30.8 ± 7.7 Hemagio pericytoma 1 - - 1 1 1 - 32.5 ± 19.1 Malignant fibrous h ystiocytoma - - - 1 1 - - 38.5 ± 2.1 Myxoid liposarcoma - 1 - - - - - 27* Fibro sarcoma - - - - - - 6 62* Dermato fibrosarcoma - 1 - - - - - 14* Reticular cell sarcoma - - 1 - - - - 23* Total 11 16 66 65 34 6 8 *Denotes age of the lone patient in the gro up; #2 Patients did not have their age specified.  K. Adriane / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 50-54 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 52 Table 3. Distribution of sarcomas as per affected anatomical site. Site (%) Total % Neoplasm Palate Whole body TongueMandibleMaxillaOral cavity Parotidlip Retro molar area Row total Vascular Kaposi’s sarcoma 22.6 14.3 13.1 2.3 1.2 19.1 0.6 1.8 0.6 75.6 Hemagio pericytoma - - - - - - 25.0 50.0 - 70.0 Muscular Rhabdomyosarcoma - - - 44.4 11.1 33.3 - - - 100 Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma - - - 60.0 40.0 - - - - 100 Bony Osteosarcoma - - - 83.3 16.4 - - - - 100 Cartilagenous Chondrosarcoma - - - 60.0 40.0 - - - - 100 Fibrous Malignant fibrous hystiocytoma 100 - - - - - - - - 100 Fibro sarcoma - - - - - 100 - 100 - 100 Dermato fibrosarcoma - - - - - - - - - 100 Fatty Myxoid liposarcoma - - - - - 100 - - - 100 Unclear Histiogenesis Reticular cell sarcoma - - - - - - 100 - - 100 The missing row percentages are for those cases whose site was not established. Table 4. Distribution of sarcomas as per chief complaint/reason for coming to hospital. Neoplasm Chief complaint of p atient N ) Duration ( weeks ) Swelling Referral Pain+ swelling Bleeding PainDifficult eating Swelling+ bleeding Pain+ Numbness Wound Kaposi’s sarcoma 30 7 37 5 3 5 2 1 2 1 - 156 Rhabdomyosarcoma 1 - 2 - - - - - - 1 - 24 Osteosarcoma 1 - 3 - - - - 1 - 6 - 22 Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma 1 - - - - - - - - 4* Chondrosarcoma 1 - 3 - - - - - - 3 - 60 Hemagio pericytoma - - 1 - - - - - - 3* Malignant fibrous hystiocytoma - - 1 - - - - - - 7* Myxoid liposarcoma 1 - - - - - - - - 8* Fibro sarcoma - - 1 - - - - - - 250 Dermato fibrosarcoma 1 - - - - - - - - 4 Reticular cell sarcoma - - - - - - - - - 1* Total 36 7 48 5 3 5 2 2 2 1 - 205 *Data available for one case or onl y one case was found.  K. Adriane / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 50-54 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 53 Table 5. Distribution of sarcomas as per treatment modality. Treatment (% of cases) Neoplasm Chemo and or HAARTSurgRadioSurg RadioSurg+ChemoSurg Chemo Radio Not established Kaposi’s sarcoma 73.3 - - - 0.6 - 26.2 Rhabdomyosarcoma - - - 55.6 - - 44.4 Osteosarcoma 16.7 - - 16.7 50.1 16.7 - Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma 20.0 - - - - - 80.0 Chondrosarcoma - - - - 20.0 80.0 - Hemagio pericytoma 50.0 50.0- - - - - Malignant fibrous hystiocytoma 50.0 - - - - - 50.0 Myxoid liposarcoma 100 - - - - - - Fibro sarcoma 100 - - - - - - Dermato fibrosarcoma 100 - - - - - - Reticular cell sarcoma - - - - - - 100 Those under not established are cases whose files couldn’t be traced. the second dose of chemotherapy. We were only able to follow a few patients due to distances involved. 4. DISCUSSION Little is known of the epidemiology of oral maxillofacial sarcomas in a Ugandan population. The data analyzed here differed a bit with the general epidemiology of the disease probably due to the high number of Kaposi’s sarcoma cases (Table 1) seen at our centre [1,3,7,8]. Although a study f rom Ken ya [8 ] reported Kaposi’s sar- coma as the commonest sarcoma, their percentage was not as high as that seen in this stu dy (P 0.001 chi 72.19). On the other hand, a Nigerian [7] study reported only one case therefore either other centers have most of the biopsies for Kaposi’s sarcoma diagnosis taken by other specialties or the oral facial component of the disease is the main manifestation among our population. This has been alluded to by Ziegler et al. [14]. All Kaposi’s sar- coma patients were HIV positive with up to 17.7% being on HAART at the time of diagnosis. This was not a sur- prise given the fact that increased incidence of HIV/ AIDS associated Kaposis sarcoma has been reported by other authors [15]. We could not ascertain the exact treatment that our Kaposi’s sarcoma patients got due to an ongoing research randomizing them in HAART group and other arms. However, the main stay of treat- ment in the cou n tr y is HAA RT ex c ep t in a fe w cas e s th at are given chemotherapy as well. It has become standard practice in this era of HAART to expect a resolution of the lesions with improving immunity and increase in CD4 cell count [16,17]. Rhabdomyosarcoma was the second commonest sar- coma in our series followed by osteosarcoma and then chondrosarcoma. The data in this study is slightly dif- ferent in that respect when compared to other reports that rank rhabdomyosarcoma second to fourth in preva- lence [1,7,8,18,19]. Chondrosarcoma is reported to be rare in the head and neck region [1,7,18] therefore the prevalence in this study was rather high but not statisti- cally significantly different from that reported by a Ke- nyan study that picked just 3 cases over a ten year period (P = 0.12 chi 2.38). A Nigerian [7] report had only 2 cases of chondrosarcoma that were loco-regional failures from other centre in a twenty year study. It is hard to tell if the prevalence in Uganda is higher or it’s because our unit is the only fu nctional maxillofacial uni t in the coun- try at present. Unfortunately the risk factors for sarco- mas have not been well addressed and it was not any different in this study therefore we could not establish if there are any particular factors to explain this high oc- currence. The majority of our patients presented with swelling and pain as the chief complaints. This differed with re- ports from developed country [18,20]. Sarcomas are known to present as painless swelling therefore pain on set is either because of advancement or supra infection. In this study painful swellings were the commonest chief complaints. This probably was due to delayed reporting and supra infection. In fact one of the chondrosarcoma patients decided to try traditional healers un til pain set in before she came back for surgery. In this study surgical intervention for non Kaposi’s sarcoma disease was the primary treatment modality just as reported by other authors [1,7,8,18]. Surgery was ac- companied by some form of adjuvant therapy with either radiation and/or chemotherapy. However, the few whose outcome was established, the results were discouraging as many died within a short time.  K. Adriane / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 50-54 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 54 Future research should focus on survival of patients and the factors that affect treatment outcomes. A mecha- nism for long term follow up has to be implemented. With increasing mobile teleph one penetration, a window of opportunity is available to aid us in follow up. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors acknowledge the contributions of the pathologist at Mak- erere University department of pathology, radio oncologists of Mulago hospital and medical oncologists of Uganda cancer institute in the diagnosis and treatment of the patien ts. REFERENCES [1] Sturgis, M.E. and Potter, O.B. (2003) Sarcomas of the head and neck region. Current Opinion in Oncology, 15, 239-252. doi:10.1097/00001622-200305000-00011 [2] Ahmad, Z., Qureshi, A. and Khurshid, A. (2009) The practice of histopathology in a developing country: difficulties and challenges; plus a discussion on the te- rrible disease burden we carry. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 62, 97-101. doi:10.1136/jcp.2008.061606 [3] American Cancer Society. (2008) Cancer Facts & Figures. American Cancer Society, Atlanta. [4] Boutayeb, A. and Boutayeb, S. (2005) The burden of non communicable diseases in developing countries. Inter- national Journal for Equity in Health, 4, 2. http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/4/1/2 doi:10.1186/1475-9276-4-2 [5] Dillon, P., Maurer, H., Jenkins, J., Krummel, T., Parham, D., Webber, B. and Salzberg, A. (1992) A prospective study of nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas in the pediatric age group. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 27, 241-245. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(92)90320-7 [6] Gurney, J.G., Swensen, A.R. and Bulterys, M. (1999) Malignant bone tumors. In: Reis, L.A.G., Smith, M.A., Gurney, J.G., et al., Eds. Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: United States SEER Program, 1975-1995. National Cancer Institute SEER Program. NIH Pub., Bethesda, No. 99-4649, 99-110. [7] Adebayo, T.E., Ajike, O.S. and Adebola. A. (2005) Maxillo-facial sarcomas in Nigeria. Annals of African Medicine, 4, 23-30. [8] Chidia, L.M., Swaleh, M.S. and Godiah. M.P. (2000) Sarcomas of the head and neck at Kenyatta National Hospital. East African Medical Journal, 77, 256-259. [9] Yamaguchi, S., Nagasawa, H., Suzuki, T., Fujii, E., Iwaki, H., Takagi, M. and Amagasa, T. (2004) Sarcomas of the oral and maxillofacial region: a review of 32 cases in 25 years. Clinical Oral Investigations, 8, 52-55. doi:10.1007/s00784-003-0233-4 [10] Pandey, M., Chandramohan, K., Thomas, G., Mathew, A., Sebastian, P., Somanathan, T., Abraham, K.E., Rajan, B. and Krishnan Nair, M. (2003) Soft tissue sarcoma of the head and neck region in adults. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 32, 43-48. doi:10.1054/ijom.2001.0218 [11] Parkin, M.D., Bray, F., Ferlay, J. and Pisani, P. (2005) Global Cancer Statistics, 2002. CA: Cancer Journal for Clinicians 55, 74-108. http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/content/full/55/2/74 doi:10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74 [12] Ledergerber, B., Telenti, A. and Effer, M.(1999) Risk of HIV related Kaposi’s sarcoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with potent antiretroviral therapy: prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal, 319, 23-24. [13] Omar, J.M., Hamza, O.J., Matee, M.I., Simon, E.N., Kikwilu, E., Moshi, M.J., Mugusi, F., Mikx, F.H., Verweij, P.E. and van der Ven, A.J. (2006) Oral manifestations of HIV infection in children and adults receiving highly active anti-retroviral therapy [HAART] in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Oral Health, 6, 12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-12. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-6-12 [14] Ziegler, J.L. and Katongole-Mbidde, E. (1996) Kaposi’s sarcoma in childhood:an analysis of 100 cases from Uganda and relationship to HIV infection. International Journal of Cancer, 65, 200-203. [15] Orem, J., Otieno, W.M. and Remick, C.S. (2004) AIDS- associated cancer in developing nations. Current Opinion in Oncology, 16, 468-476. doi:10.1097/00001622-200409000-00010 [16] Dupin, N. and Giudice, D.P. (2008) Treatment of kaposi sarcoma in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 47, 418-420. doi:10.1086/589866 [17] Dupont, C., Vasseur, E., Beauchet, A., Aegerter, P., Berthe, H., de Truchis, P., et al. (2000) Long-term effi- cacy on Kaposi’s sarcoma of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-positive patients. AIDS, 14, 987-993 doi:10.1097/00002030-200005260-00010 [18] Herzog, E.C. (2005) Overview of sarcomas in the adolescent and young adult population. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 27, 215-218 doi:10.1097/01.mph.0000161762.53175.e4 [19] Chidzonga, M. and Mahomva, L. (2007) Sarcomas of the oral and maxillofacial region: A review of 88 cases in Zimbabwe. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 45, 317-318. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.11.008 [20] van der Waal, R. and van der Waal, I. (2007) Oral non-squamous malignant tumors; diagnosis and treatment. Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal, 12, E486-91. |