Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

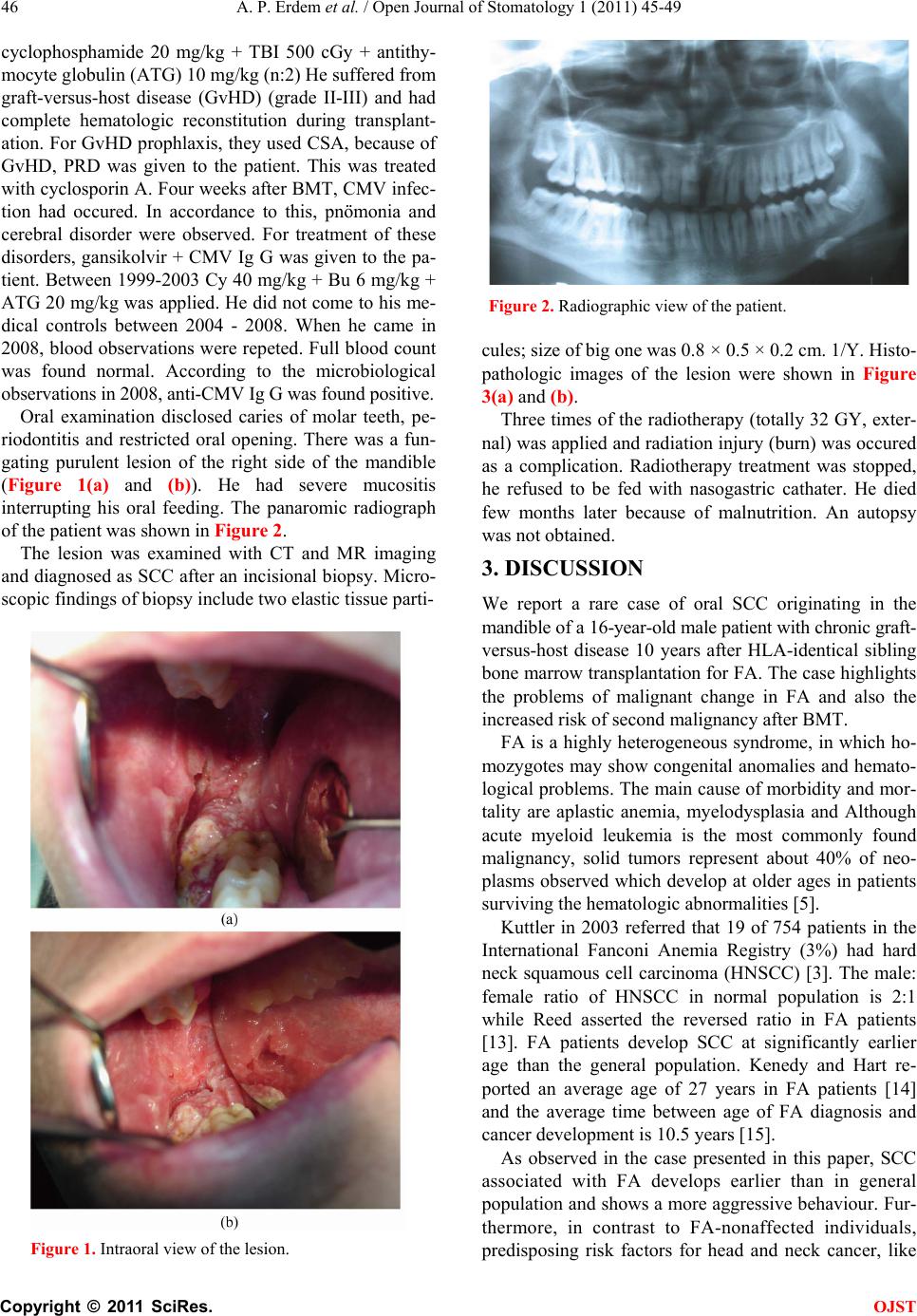

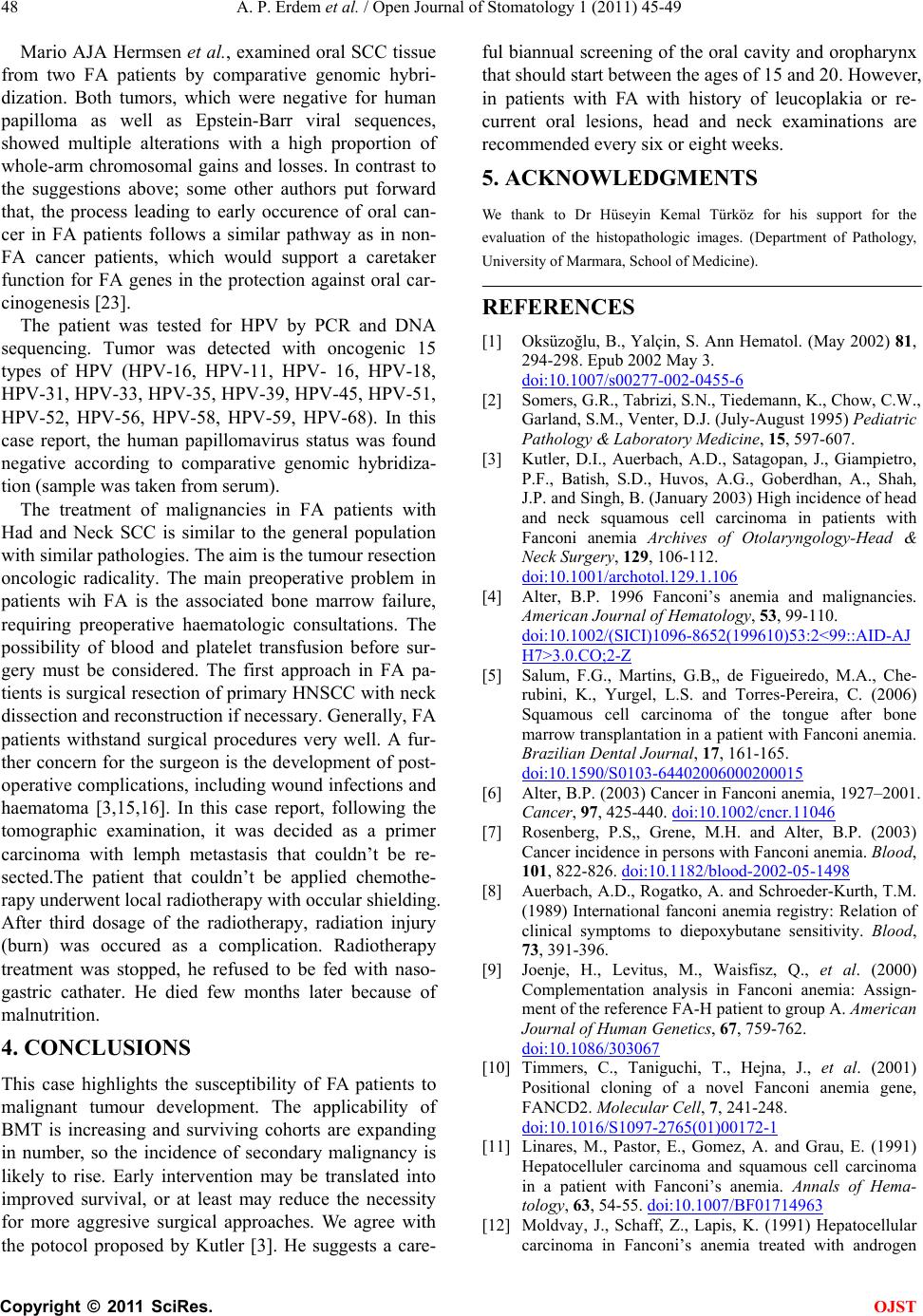

Open Journal of Stomatology, 2011, 1, 45-49 OJST doi:10.4236/ojst.2011.12008 Published Online June 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJST/). Published Online June 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJST Fanconi anemia manifesting as a squamous cell carcinoma of the mandible: a case report A. Pinar Erdem 1, G. Ikikarakayali1, N. Yalman2, G. Ak3, M. A. Erdem 4, M. B. Bilgic5, E. Sepet1 1Department of Pedodontics, Dentistry Faculty, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey; 2Department of Medical Biology, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey; 3Department of Oral Surgery and Medicine, Dentistry Faculty, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey; 4Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dentistry Faculty, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey; 5Department of Pathology, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey. E-mail: goksenkayali@gmail.com Received 16 March 2011; revised 20 April 2011, accepted 3 May 2011. ABSTRACT Progressive bone marrow failure and development of malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and solid tumors the most important features of Fan- coni’s Anemia (FA). This paper reports the case of a 16-year-old patient with FA who developped squa- mous cell carcinoma of the mandible, ten years after the bone marrow transplantation (BMT). Keywords: Squamous Cell Carcinoma; Fanconi’s Anemia; Mandible; Bone Marrow Transplantation 1. INTRODUCTION Fanconi’s anemia is an autosomal recessive disorder cha- racterized by constitutional aplastic anemia and conge- nital abnormalities [1]. FA is defined by chromosomal breakage in which many patients present with pancyto- penia, hypoplastic bone marrow, hyperpigmentation of the skin, skeletal malformations, small stature, hypogo- nadism, and chromosomal aberrations [2]. FA is char- acterized by a high degree of genomic instability and predisposition to cancer development [3]. The most im- portant features of FA are progressive bone marrow failure and development of malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and solid tumors [4,5]. Such patients are prone to the development of hematological malignancies and squamous cell carcinoma, especially of the head and neck [2,6,7]. FA is characteristically defined by its cellular hyper- sensitivity to DNA cross-linking agents such as diepoxy- butane and mitomycin [2,8]. Based on the presence of mutations in one of the FA genes, FA can be divided into 8 complementation groups (A-G, including D1 and D2), with each group having in common the cellular hypersensitivity to cross-linking agents [9,10]. Current therapy regimen consists of supportive treatment and androgens, steroids and cytokines. But allogenic bone marrow transplantation is the definite treatment of choice for FA patients with progressive bone marrow failure. FA patients are at risk for secondary malignan- cies, for example leukemia, squamous cell carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma [11,12]. The risk of squamous cell carcinoma development is especially high in the anogenital region as well as the head and neck region [1]. A review of the literature revealed 40 cases of SCC in FA patients. 14 of these cases involved oral carcinoma, with tongue being the most frequently affected site. In this review, all of the reported SCC in FA patients origi- nated in mucosal and mucocutaneous sites, especially oral (n = 25) and anogenital sites (n = 8) and the esopha- gus (n = 6), with the exception of two patients with mul- tiple cutaneous involvement [1]. We report SCC of the mandible in a patient with FA. Only one case of SCC of the mandible in a patient with FA patient was reported in 1980 by Vaitiekaitis AS et al. This is a report of a second case. 2. CASE REPORT We report the case of a 16-year-old boy with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the mandible. On January 2, 2008 he was referred to Istanbul University, Faculty of Dentistry with a mass on the right side of the mandible. FA with an unknown complementation group had been diagnosed at the age of 5 years. He is the second child of the consangenious marriage. He underwent BMT at 1998 with marrow donated by her HLA-identical sister who did not have FA. Pre-transplant conditioning con- sisted of cyclophosphamide 20 mg/kg + total body irra- diation (TBI) 750 cGy (n:11). At 1998 before the BMT the dosage of the medicine regimen was changed as  A. P. Erdem et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 45-49 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 46 cyclophosphamide 20 mg/kg + TBI 500 cGy + antithy- mocyte globulin (ATG) 10 mg/kg (n:2) He suffered from graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) (grade II-III) and had complete hematologic reconstitution during transplant- ation. For GvHD prophlaxis, they used CSA, because of GvHD, PRD was given to the patient. This was treated with cyclosporin A. Four weeks after BMT, CMV infec- tion had occured. In accordance to this, pnömonia and cerebral disorder were observed. For treatment of these disorders, gansikolvir + CMV Ig G was given to the pa- tient. Between 1999-2003 Cy 40 mg/kg + Bu 6 mg/kg + ATG 20 mg/kg was applied. He did not come to his me- dical controls between 2004 - 2008. When he came in 2008, blood observations were repeted. Full blood count was found normal. According to the microbiological observations in 2008, anti-CMV Ig G was found positive. Oral examination disclosed caries of molar teeth, pe- riodontitis and restricted oral opening. There was a fun- gating purulent lesion of the right side of the mandible (Figure 1(a) and (b)). He had severe mucositis interrupting his oral feeding. The panaromic radiograph of the patient was shown in Figure 2. The lesion was examined with CT and MR imaging and diagnosed as SCC after an incisional biopsy. Micro- scopic findings of biopsy include two elastic tissue parti- Figure 1. Intraoral view of the lesion. Figure 2. Radiographic view of the patient. cules; size of big one was 0.8 × 0.5 × 0.2 cm. 1/Y. Histo- pathologic images of the lesion were shown in Figure 3(a) and (b). Three times of the radiotherapy (totally 32 GY, exter- nal) was applied and radiation injury (burn) was occured as a complication. Radiotherapy treatment was stopped, he refused to be fed with nasogastric cathater. He died few months later because of malnutrition. An autopsy was not obtained. 3. DISCUSSION We report a rare case of oral SCC originating in the mandible of a 16-year-old male patient with chronic graft- versus-host disease 10 years after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation for FA. The case highlights the problems of malignant change in FA and also the increased risk of second malignancy after BMT. FA is a highly heterogeneous syndrome, in which ho- mozygotes may show congenital anomalies and hemato- logical problems. The main cause of morbidity and mor- tality are aplastic anemia, myelodysplasia and Although acute myeloid leukemia is the most commonly found malignancy, solid tumors represent about 40% of neo- plasms observed which develop at older ages in patients surviving the hematologic abnormalities [5]. Kuttler in 2003 referred that 19 of 754 patients in the International Fanconi Anemia Registry (3%) had hard neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [3]. The male: female ratio of HNSCC in normal population is 2:1 while Reed asserted the reversed ratio in FA patients [13]. FA patients develop SCC at significantly earlier age than the general population. Kenedy and Hart re- ported an average age of 27 years in FA patients [14] and the average time between age of FA diagnosis and cancer development is 10.5 years [15]. As observed in the case presented in this paper, SCC associated with FA develops earlier than in general population and shows a more aggressive behaviour. Fur- thermore, in contrast to FA-nonaffected individuals, predisposing risk factors for head and neck cancer, like  A. P. Erdem et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 45-49 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 47 Figure 3. Histopathologic images of the lesion. tobacco and alcohol abuse, are rare in these patients. Jansisyanont reported that the commonest localizations of SCC in FA patients in descending order are: tounge, anogenital region, pharynx, larynx, oral [5] mucosa, mandible and skin [16]. In this report, development of malignancy occured 10 years after BMT, which is a longer period than that observed by Deeg et al. who reported that malignancy development occured in a peak between 8 and 9 years after BMT [5]. Although FA appears to be genetically heterogeneous, all cases display abnormalities of DNA repair. A gene defective in one of the four subsets of FA patients has been defined. Defects in this gene are thought to play a role in the development of neoplasia in FA patients. However, many other factors may also contribute to the development of malignancies. Some of the authors suggested that patients that have endured BMT have a greater incidence of malignancies development. In these patients, there are four additional factors including pre- transplant total body irradiation, cyclophosphamide treat- ment, chronic GvHD, and prolonged immunosuppresive treatment after transplantation [2,15-17]. Most patients who develop malignancy after BMT also have chronic GvHD. Additionally, some authors observed the development of such tumors on sites initially in- volved with GvHD-related inflammatory processes [5]. It was proposed that TBI and certain treatments for acute GvHD were risk factors in the development of secondary tumors. Lishner et al., also reported solid tu- mors in patients with chronic GvHD after BMT for a variety of conditions including aplastic anemia [18]. A single patient with FA who developed SCC of the tounge at age 29, 10 yeras after BMT complicated by chronic GvHD, has been reported [19]. A 12 year old boy with FA developed SCC of the tounge 74 months after BMT [20]. It was estimated by the same investi- gators that there is a 22-fold higher risk of solid tumor development in patients transplanted for aplastic anemia (AA) than in the general population. Salum et al; reported the case of a 12-year-old patient with FA who had been submitted to BMT at the age of 5 and exhibited oral lesions characteristic of chronic GvHD. Eleven years after the BMT, he developed SCC of the tongue with an aggressive behavior, which was considered an untreatable condition [5]. Millen et al, reported a case of oral SCC originating in the buccal mucosa of an 18-year-old fe- male patient with chronic GvHD 9 years after HLA-identical sibling BMT for FA. They su- pported that the patient could be seen to have had multiple risk factors including genetic predisposition, pretransplant conditioning with both cyclophosphamide and TBI, chronic GvHD and prolonged immunosu- ppresive treatment [18]. The patient presented in this case report showed GvHD following the bone marrow transplantation, four weeks later CMV sepsis was developed. Abdelsayed et al. advocated that oral cancer in pa- tients with GvHD may have an aggressive biologic po- tential with increased tendency for recurrence and deve- lopment of new lesions [5]. Spardy et al. suggested that FA patients have an incresed risk for SCC at sites of predilection for infec- tion with high-risk human papillomavirus types includ- ing the oral cavity and the anogenital tract. They esta- blished that the FA pathway as an early host cell re- sponse to high-risk HPV infection [21]. The patients with FA may be particularly susceptible to HPV-induced carcinogenesis [3]. HPV vaccines, which are currently under development, might help to prevent HPV infection in both the cervix and the oro- pharynx [22].  A. P. Erdem et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 45-49 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 48 Mario AJA Hermsen et al., examined oral SCC tissue from two FA patients by comparative genomic hybri- dization. Both tumors, which were negative for human papilloma as well as Epstein-Barr viral sequences, showed multiple alterations with a high proportion of whole-arm chromosomal gains and losses. In contrast to the suggestions above; some other authors put forward that, the process leading to early occurence of oral can- cer in FA patients follows a similar pathway as in non- FA cancer patients, which would support a caretaker function for FA genes in the protection against oral car- cinogenesis [23]. The patient was tested for HPV by PCR and DNA sequencing. Tumor was detected with oncogenic 15 types of HPV (HPV-16, HPV-11, HPV- 16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, HPV-39, HPV-45, HPV-51, HPV-52, HPV-56, HPV-58, HPV-59, HPV-68). In this case report, the human papillomavirus status was found negative according to comparative genomic hybridiza- tion (sample was taken from serum). The treatment of malignancies in FA patients with Had and Neck SCC is similar to the general population with similar pathologies. The aim is the tumour resection oncologic radicality. The main preoperative problem in patients wih FA is the associated bone marrow failure, requiring preoperative haematologic consultations. The possibility of blood and platelet transfusion before sur- gery must be considered. The first approach in FA pa- tients is surgical resection of primary HNSCC with neck dissection and reconstruction if necessary. Generally, FA patients withstand surgical procedures very well. A fur- ther concern for the surgeon is the development of post- operative complications, including wound infections and haematoma [3,15,16]. In this case report, following the tomographic examination, it was decided as a primer carcinoma with lemph metastasis that couldn’t be re- sected.The patient that couldn’t be applied chemothe- rapy underwent local radiotherapy with occular shielding. After third dosage of the radiotherapy, radiation injury (burn) was occured as a complication. Radiotherapy treatment was stopped, he refused to be fed with naso- gastric cathater. He died few months later because of malnutrition. 4. CONCLUSIONS This case highlights the susceptibility of FA patients to malignant tumour development. The applicability of BMT is increasing and surviving cohorts are expanding in number, so the incidence of secondary malignancy is likely to rise. Early intervention may be translated into improved survival, or at least may reduce the necessity for more aggresive surgical approaches. We agree with the potocol proposed by Kutler [3]. He suggests a care- ful biannual screening of the oral cavity and oropharynx that should start between the ages of 15 and 20. However, in patients with FA with history of leucoplakia or re- current oral lesions, head and neck examinations are recommended every six or eight weeks. 5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank to Dr Hüseyin Kemal Türköz for his support for the evaluation of the histopathologic images. (Department of Pathology, University of Marmara, School of Medicine). REFERENCES [1] Oksüzoğlu, B., Yalçin, S. Ann Hematol. (May 2002) 81, 294-298. Epub 2002 May 3. doi:10.1007/s00277-002-0455-6 [2] Somers, G.R., Tabrizi, S.N., Tiedemann, K., Chow, C.W., Garland, S.M., Venter, D.J. (July-August 1995) Pediatric Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 15, 597-607. [3] Kutler, D.I., Auerbach, A.D., Satagopan, J., Giampietro, P.F., Batish, S.D., Huvos, A.G., Goberdhan, A., Shah, J.P. and Singh, B. (January 2003) High incidence of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in patients with Fanconi anemia Archives of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, 129, 106-112. doi:10.1001/archotol.129.1.106 [4] Alter, B.P. 1996 Fanconi’s anemia and malignancies. American Journal of Hematology, 53, 99-110. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199610)53:2<99::AID-AJ H7>3.0.CO;2-Z [5] Salum, F.G., Martins, G.B,, de Figueiredo, M.A., Che- rubini, K., Yurgel, L.S. and Torres-Pereira, C. (2006) Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue after bone marrow transplantation in a patient with Fanconi anemia. Brazilian Dental Journal, 17, 161-165. doi:10.1590/S0103-64402006000200015 [6] Alter, B.P. (2003) Cancer in Fanconi anemia, 1927–2001. Cancer, 97, 425-440. doi:10.1002/cncr.11046 [7] Rosenberg, P.S,, Grene, M.H. and Alter, B.P. (2003) Cancer incidence in persons with Fanconi anemia. Blood, 101, 822-826. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-05-1498 [8] Auerbach, A.D., Rogatko, A. and Schroeder-Kurth, T.M. (1989) International fanconi anemia registry: Relation of clinical symptoms to diepoxybutane sensitivity. Blood, 73, 391-396. [9] Joenje, H., Levitus, M., Waisfisz, Q., et al. (2000) Complementation analysis in Fanconi anemia: Assign- ment of the reference FA-H patient to group A. American Journal of Human Genetics, 67, 759-762. doi:10.1086/303067 [10] Timmers, C., Taniguchi, T., Hejna, J., et al. (2001) Positional cloning of a novel Fanconi anemia gene, FANCD2. Molecular Cell, 7, 241-248. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00172-1 [11] Linares, M., Pastor, E., Gomez, A. and Grau, E. (1991) Hepatocelluler carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in a patient with Fanconi’s anemia. Annals of Hema- tology, 63, 54-55. doi:10.1007/BF01714963 [12] Moldvay, J., Schaff, Z., Lapis, K. (1991) Hepatocellular carcinoma in Fanconi’s anemia treated with androgen  A. P. Erdem et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 45-49 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 49 and corticosteroid. Zentralblatt fur Pathologie, 137, 167-170. [13] Reed, K., Ravikumar, T.S., Gifford, R.R., Grage, T.B. (1983) The association of Fanconi’s anemia and Squa- mous cell carcinoma. Cancer, 52, 926-928. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19830901)52:5<926::AID-CNC R2820520530>3.0.CO;2-T [14] Kennedy, A.W., Hart, W.R. (1982) Multiple squamous cell carcinomas in Fanconi’anemia. Cancer, 50, 811-814. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19820815)50:4<811::AID-CNC R2820500432>3.0.CO;2-I [15] Lustig, J.P., Lugassy, G., Neder, A. and Sigler, E. (1995) Head and neck carcinoma in fanconi’s anemia-report of a case and review of the literature. European Journal of Cancer Part B: Oral Oncology, 31, 68-72. doi:10.1016/0964-1955(94)00044-5 [16] Jansisyanont, P., Pazoki, A. and Ord, R.A. (2000) Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue after bone marrow transplantation in a patiant with Fanconi’s ane- mia. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 58, 1454-1457. doi:10.1053/joms.2000.19212 [17] Socie, G., Scieux, C., Gluckman, E., Soussi, T., Clavel, C., Saulnier. P., Birembault, P., Bosq, J., Morinet, F. and Janin, A. (1998) Squamous cell carcinoma after allogenic bone marrow transplantation for aplastic anemia: Further evidence of a multistep process. Transplantation, 66, 667-670. doi:10.1097/00007890-199809150-00023 [18] Millen, F.J., Rainey, M.G., Hows, J.M., Burton, P.A,, Irvine, G.H. and Swirsky. D. (1997) Oral squamous cell carcinoma after allogenic bone marrow transplantation for Fanconi anemia. British Journal of Haematology, 99, 410-414. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3683184.x [19] Bradford, C.R., Hoffman, H.T., Wolf, G.T., Carey, T.E., Baker, S.R. and McClatchey, K.D. (1990) Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in organ transplant recipients: Possible role of oncogenic viruses, The Laryn- goscope, 100, 190-194. [20] Socie, G., Henry-Amar, M., Cosset, J.M., Devergie, A., Girinsky, T. and Gluckman, E. (1991), Increased ince- dence of solid malignant tumors after bone marrow trans- plantation for sever aplastic anemia. 78, 277-279. [21] Spardy, N., Duensing, A., Charles, D., Haines, N., Nakahara, T., Lambert, P.F., Duensing, S. (December 2007) The human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein activates the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway and causes accelerated chromosomal instability in FA cells. The Journal of Virology, 81, 13265-13270. doi:10.1128/JVI.01121-07 [22] Gillison, M.L. and Lowy, D.R. (2004) A casual role for human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer. The Lancet, 363, 1488-1489. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16194-1 [23] Hermsen, M.A., Xie, Y., Rooimans, M.A., Meijer, G.A., Baak, J.P., Plukker, J.T., Arwert, F. and Joenje, H. (2001) Cytogenetic characteristics of oral squamous cell carcinomas in Fanconi anemia. Familial Cancer, 1, 39-43. doi:10.1023/A:1011528310346 |