Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

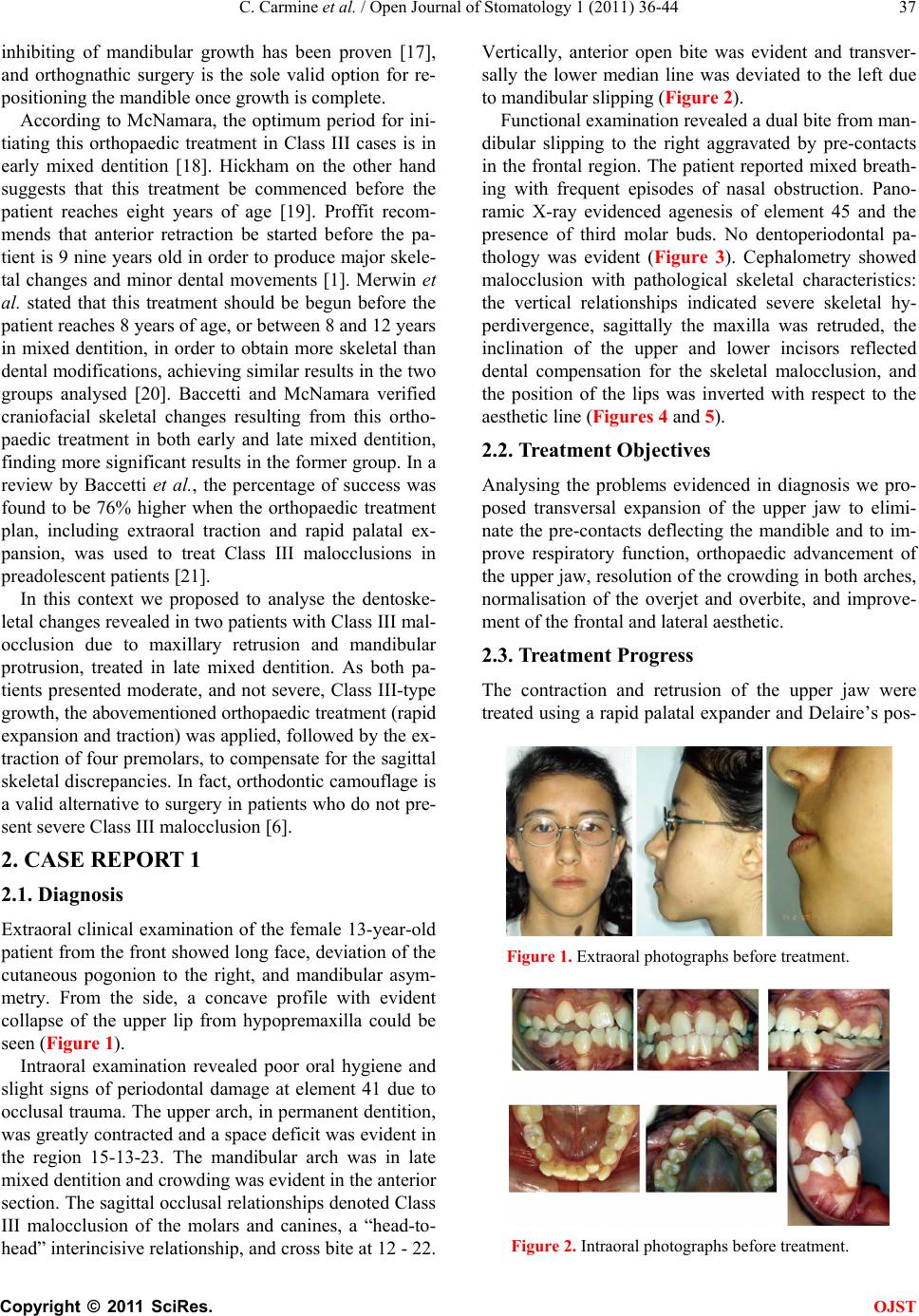

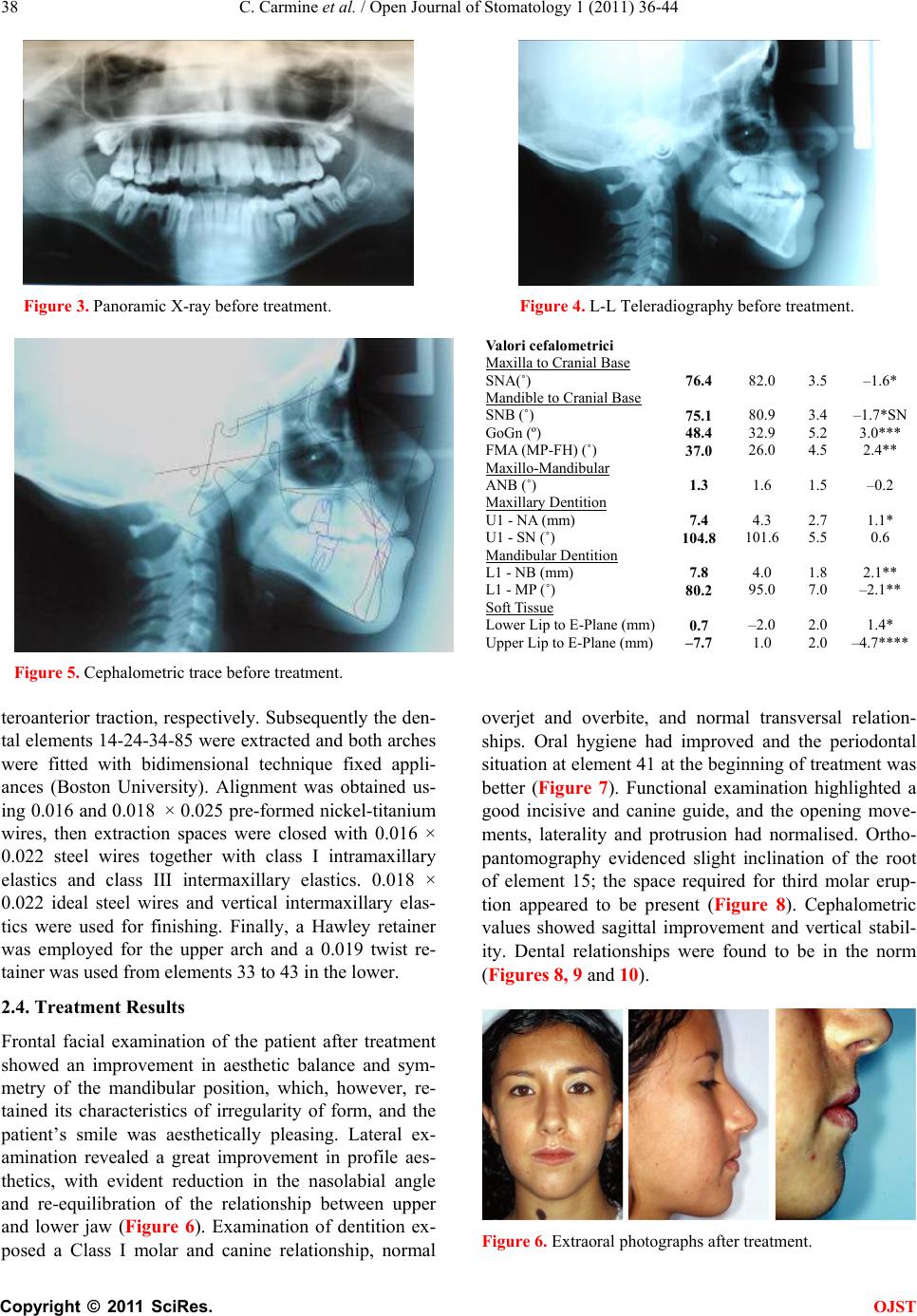

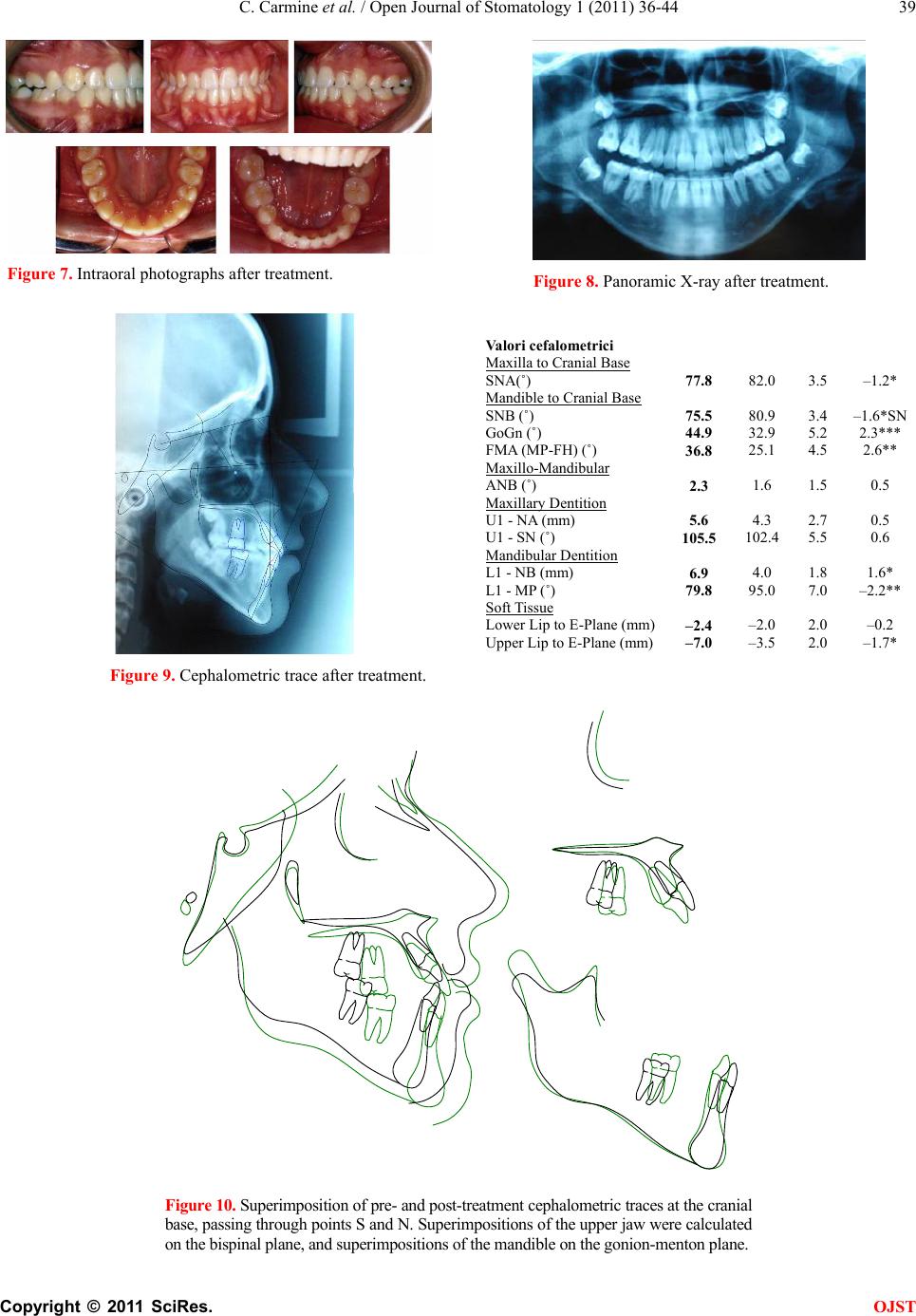

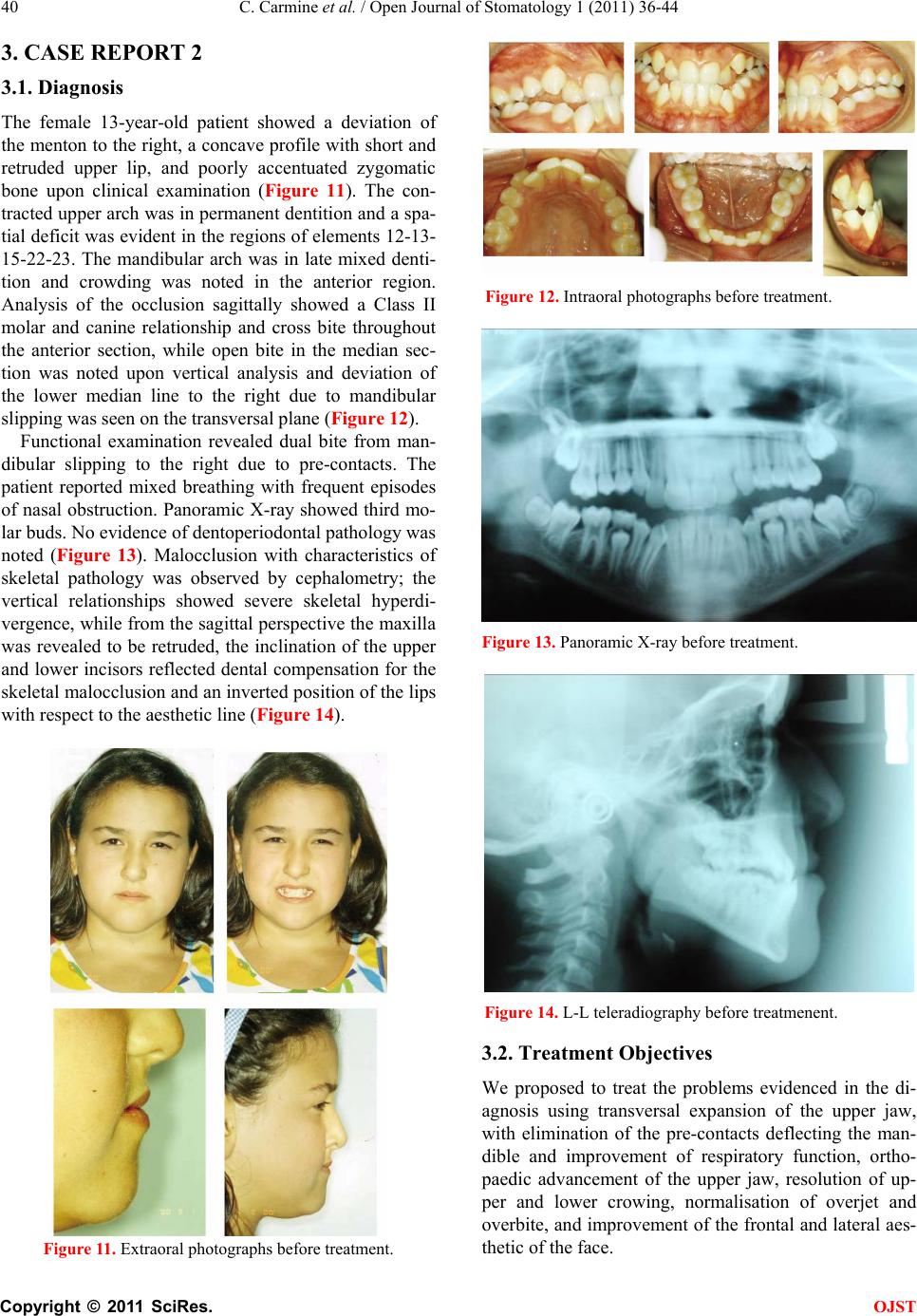

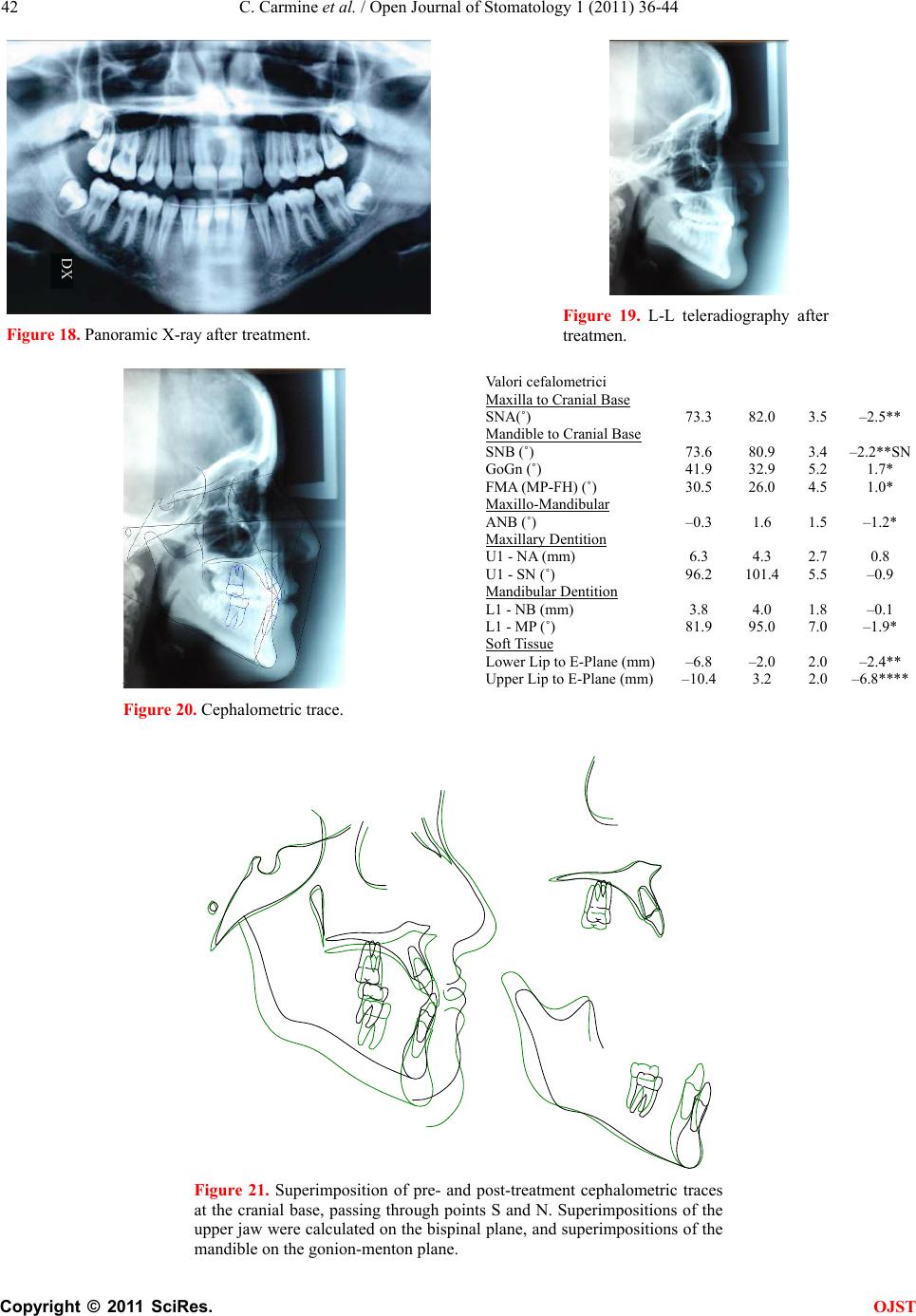

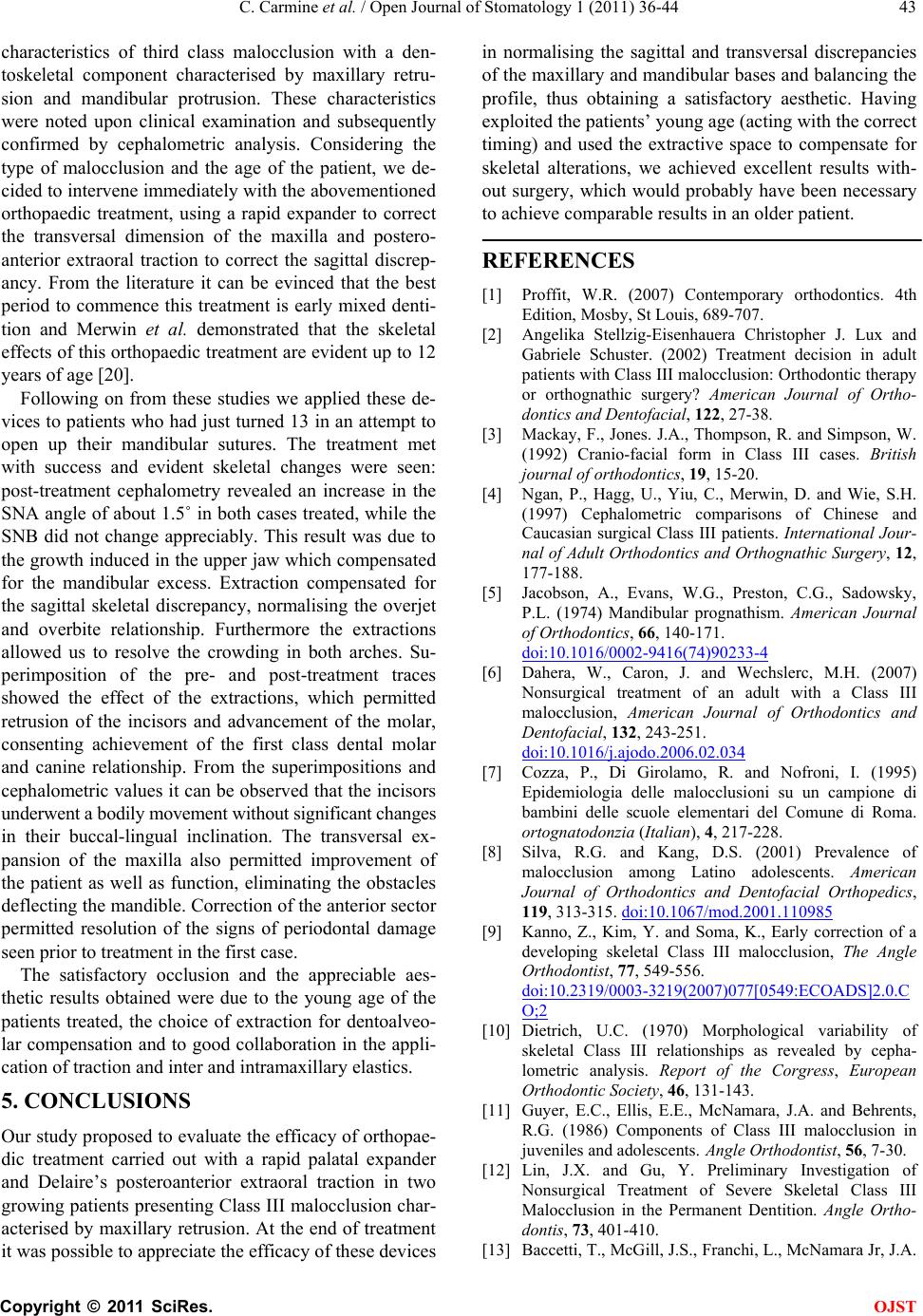

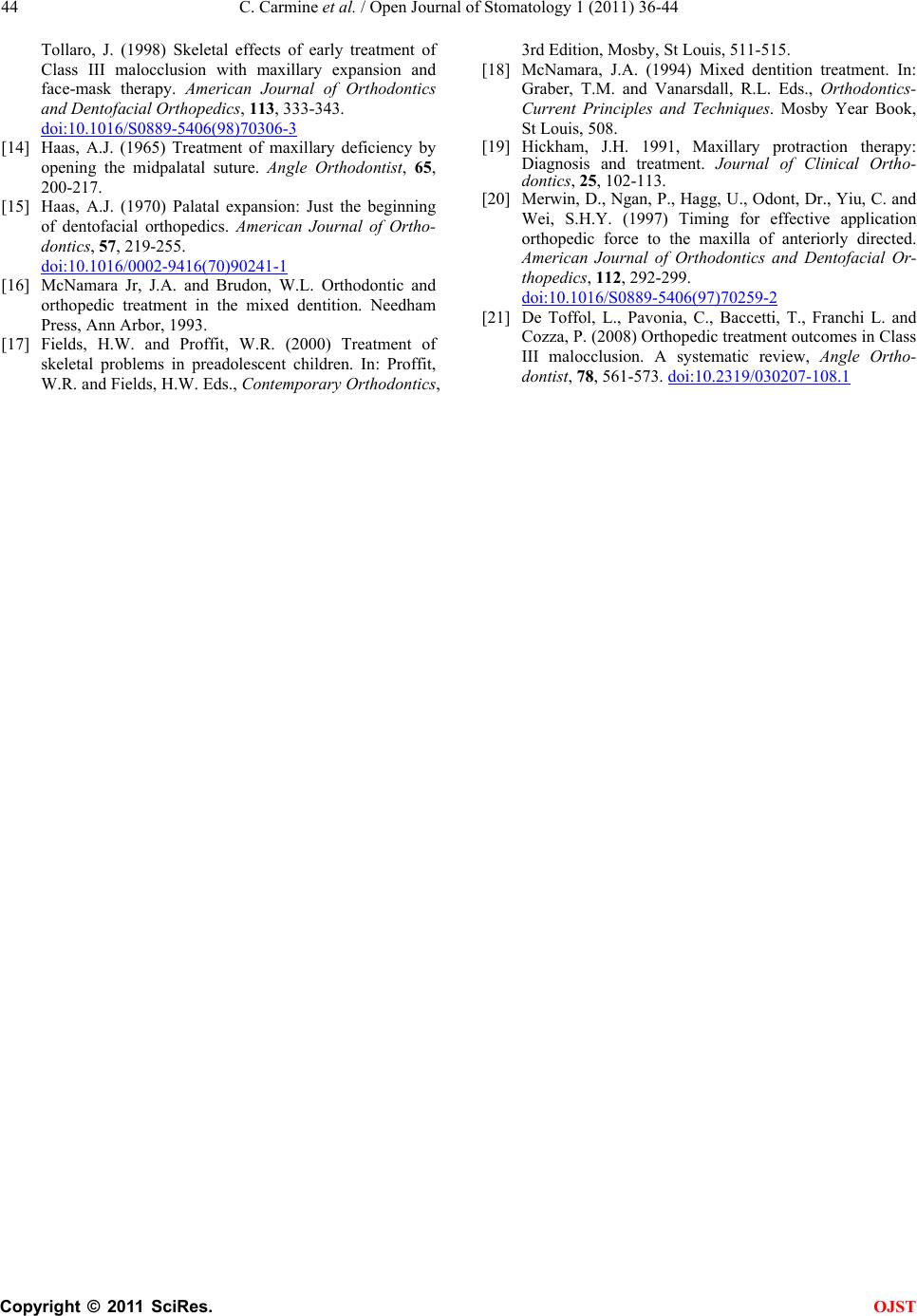

Open Journal of Stomatology, 2011, 1, 36-44 OJST doi:10.4236/ojst.2011.12007 Published Online June 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/OJST/). Published Online June 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJST Extractive orthopaedic treatment to compensate for skeletal Class III in preadolescents Chiusolo Carmine, Gennaro Caiazzo, Luca Lombardo, Maria Paola Guarneri, Giuseppe Siciliani Postgraduate School of Orthodontics of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy. E-mail: lulombardo@tiscali.it Received 11 March 2011; revised 13 April 2011, accepted 30 April 2011. ABSTRACT Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of extractive or- thopaedic orthodontic treatment in mixed late denti- tion in two female patients presenting Class III mal- occlusion and hyperdivergent facial types due to maxillary retrusion. Materials and Methods: The or- thopaedic phase, carried out using posteroanterior extraoral traction combined with rapid palatal ex- panders, was followed by extraction of four premo- lars and application of bidimensional technique fixed appliances (Boston University). Results: We achieved functional and aesthetic improvement via normalisa- tion of the transversal dimensions and a sagittal in- crease in the maxilla while maintaining vertical sta- bility. The extractions permitted resolution of the crowding problem and normalisation of the overbite and overjet, and Class I molar and canine occlusion was achieved. Conclusions: Timely intervention and exploitation of extractive space to compensate for skeletal alterations using only orthopaedic orthodon- tic treatment can allow achievement of excellent re- sults. Keywords: Extractive; Orthopaedic; Treatment 1. INTRODUCTION Class III malocclusion may involve the dental compo- nent alone or it may be aggravated by a poor relationship between the maxillary and mandibular bases. In the for- mer case, the lower molar is positioned half a cuspid towards the midline with respect to the upper molar, without skeletal alteration, whereas the latter type also involves a poor relationship between maxilla and man- dible on the sagittal plane caused by maxillary retrusion and/or mandibular protrusion [1]. Patients presenting a sagittally reduced maxilla also frequently show skeletal contraction of this jaw on the transversal plane [2]. The majority of Class III patients present both dentoalveolar and skeletal components [3-5]. Various factors are implicated in the aetiology of Class III, namely heredity (e.g. race), environmental factors (e.g. functional anterior deviation of the mandi- ble or mouth breathing, which can be a positive stimulus for mandibular growth), and several pathologies (e.g. pituitary tumours responsible for acromegaly) [6]. The incidence of this type of malocclusion in Cauca- sian populations varies between 1 and 5 %, in Asian populations it reaches an upper range which fluctuates between 9% to 19%, and in Latin populations it is roughly 5% [7 , 8] . Early treatment of Class III malocclusion reduces the necessity of a second phase of treatment in permanent dentition [1]. Howev er, successful orthodontic treatment of Class III preadolescents depends not only on adequate timing but also on individual growth. In fact, the deci- sion to treat patients with moderate to severe skeletal Class III early on, or to wait until the end of growth, is a difficult one, especially as it cannot be predicted wh eth er growth will permit successful development of the de- sired skeletal modifications following orthopaedic or- thodontic treatment [9]. Several studies have reported that Class III skeletal discrepancies worsen with age [10,11]. Thus the diffi- culty in treating preadolescent patients successfully in- creases with time. Nonetheless, the majority of patients presenting severe skeletal Class III are candidates for orthognathodontic surgery, the only means of obtaining functional occlusion and aesthetic profile [12]. In early diagnosis of Class III malocclusion with max- illary deficiency in late deciduous dentition or early mixed dentition, the combination of a rapid palatal ex- pander with posteroanterior traction is a useful treatment option [13]. This traction is of ten used in synergy with a maxillary expander in preadolescent patients as this de- vice is presumed to act by opening the circumaxillary sutures and thus facilitate the orthopaedic effect of facial traction [14-16]. However, if the skeletal discrepancy is caused by excessive mandibular growth, this device seems to be of scarce therapeutic action as the impossibility of  C. Carmine et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 36-44 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 37 inhibiting of mandibular growth has been proven [17], and orthognathic surgery is the sole valid option for re- positioning the mandible once growth is complete. According to McNamara, the optimum period for ini- tiating this orthopaedic treatment in Class III cases is in early mixed dentition [18]. Hickham on the other hand suggests that this treatment be commenced before the patient reaches eight years of age [19]. Proffit recom- mends that anterior retraction be started before the pa- tient is 9 nine years old in order to produce major skele- tal changes and minor dental movements [1]. Merwin et al. stated that this treatment should be begun before the patient reaches 8 years of age, or b etw een 8 an d 1 2 years in mixed dentition, in order to obtain more skeletal than dental modifications, ach ieving similar results in the two groups analysed [20]. Baccetti and McNamara verified craniofacial skeletal changes resulting from this ortho- paedic treatment in both early and late mixed dentition, finding more significant results in the former group. In a review by Baccetti et al., the percentage of success was found to be 76% higher when the orthopaedic treatment plan, including extraoral traction and rapid palatal ex- pansion, was used to treat Class III malocclusions in preadolescent pati ent s [2 1] . In this context we proposed to analyse the dentoske- letal changes revealed in two patients with Class III mal- occlusion due to maxillary retrusion and mandibular protrusion, treated in late mixed dentition. As both pa- tients presented moderate, and not severe, Class III-type growth, the abovementioned orthopaedic treatment (rapid expansion and traction) was applied, followed by the ex- traction of four premolars, to compensate for the sagittal skeletal discrepancies. In fact, orthodontic camouflage is a valid alternative to surgery in patients who do no t pre- sent severe Class III malocclusion [6]. 2. CASE REPORT 1 2.1. Diagnosis Extraoral clinical examination of the female 13-year-old patient from the front showed long face, deviation of the cutaneous pogonion to the right, and mandibular asym- metry. From the side, a concave profile with evident collapse of the upper lip from hypopremaxilla could be seen (Figure 1). Intraoral examination revealed poor oral hygiene and slight signs of periodontal damage at element 41 due to occlusal trauma. The upper arch, in permanent dentition, was greatly contracted and a space deficit was evident in the region 15-13-23. The mandibular arch was in late mixed dentition and crowdi ng was evident in the anterior section. The sagittal occlu sal relationships deno ted Class III malocclusion of the molars and canines, a “head-to- head” interincisive relationship, and cross bite at 12 - 22. Vertically, anterior open bite was evident and transver- sally the lower median line was deviated to the left due to mandibul ar slipping (Figure 2). Functional examination revealed a dual bite from man- dibular slipping to the right aggravated by pre-contacts in the frontal region. The patient reported mixed breath- ing with frequent episodes of nasal obstruction. Pano- ramic X-ray evidenced agenesis of element 45 and the presence of third molar buds. No dentoperiodontal pa- thology was evident (Figure 3). Cephalometry showed malocclusion with pathological skeletal characteristics: the vertical relationships indicated severe skeletal hy- perdivergence, sagittally the maxilla was retruded, the inclination of the upper and lower incisors reflected dental compensation for the skeletal malocclusion, and the position of the lips was inverted with respect to the aesthetic line (Figures 4 and 5). 2.2. Treatment Objectives Analysing the problems evidenced in diagnosis we pro- posed transversal expansion of the upper jaw to elimi- nate the pre-contacts deflecting the mandible and to im- prove respiratory function, orthopaedic advancement of the upper jaw, resolution of the crowding in both arches, normalisation of the overjet and overbite, and improve- ment of the frontal and lateral aesthetic. 2.3. Treatment Progress The contraction and retrusion of the upper jaw were treated using a rapid palatal expander and Delaire’s pos- Figure 1. Extraoral photographs before treatment. Figure 2. Intraoral photographs before treatment.  C. Carmine et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 36-44 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 38 Figure 3. Panoramic X-ray before treatment. Figure 4. L-L Teleradiography before treatment. Figure 5. Cephalometric trace before treatment. teroanterior traction, respectiv ely. Subsequently the den- tal elements 14-24-34-85 were extracted and both arches were fitted with bidimensional technique fixed appli- ances (Boston University). Alignment was obtained us- ing 0.016 an d 0.018 × 0.025 pre-formed nickel-titanium wires, then extraction spaces were closed with 0.016 × 0.022 steel wires together with class I intramaxillary elastics and class III intermaxillary elastics. 0.018 × 0.022 ideal steel wires and vertical intermaxillary elas- tics were used for finishing. Finally, a Hawley retainer was employed for the upper arch and a 0.019 twist re- tainer was used from elements 33 to 43 in the lower. 2.4. Treatment Results Frontal facial examination of the patient after treatment showed an improvement in aesthetic balance and sym- metry of the mandibular position, which, however, re- tained its characteristics of irregularity of form, and the patient’s smile was aesthetically pleasing. Lateral ex- amination revealed a great improvement in profile aes- thetics, with evident reduction in the nasolabial angle and re-equilibration of the relationship between upper and lower jaw (Figure 6). Examination of dentition ex- posed a Class I molar and canine relationship, normal overjet and overbite, and normal transversal relation- ships. Oral hygiene had improved and the periodontal situation at element 41 at the beginning of treatment was better (Figure 7). Functional examination highlighted a good incisive and canine guide, and the opening move- ments, laterality and protrusion had normalised. Ortho- pantomography evidenced slight inclination of the root of element 15; the space required for third molar erup- tion appeared to be present (Figure 8). Cephalometric values showed sagittal improvement and vertical stabil- ity. Dental relationships were found to be in the norm (Figures 8, 9 and 10). Figure 6. Extraoral photographs after treatment. Valori cefalometrici Maxilla to Cranial Base SNA(˚) 76.4 82.0 3.5 –1.6* Mandible to Cranial Base SNB (˚) 75.1 80.9 3.4 –1.7*SN GoGn (º) 48.4 32.9 5.2 3.0*** FMA (MP-FH) (˚) 37.0 26.0 4.5 2.4** Maxillo-Mandibular ANB (˚) 1.3 1.6 1.5 –0.2 Maxillary Dentition U1 - NA (mm) 7.4 4.3 2.7 1.1* U1 - SN (˚) 104.8 101.6 5.5 0.6 Mandibular Dentition L1 - NB (mm) 7.8 4.0 1.8 2.1** L1 - MP (˚) 80.2 95.0 7.0 –2.1** Soft T i ssue Lower Lip to E-Plane (mm)0.7 –2.0 2.0 1.4* Upper Lip to E-Plane (m m)–7.7 1.0 2.0 –4.7****  C. Carmine et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 36-44 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 39 Figure 7. Intraor al photog raphs after treatment. Figure 8. Panoramic X-ray after treatment. Figure 9. Cephalometric trace after treatment. Figure 10. Superimpos ition of pre- and post-treatment cephalometric traces at the cranial base, passing through points S an d N. Superimpositions of the upper jaw were calculated on the bispinal plane, and superimpositions of the mandible on the gonion-menton plane. Valori cefalometrici Maxilla to Cranial Base SNA(˚) 77.8 82.0 3.5 –1.2* Mandible to Cranial Base SNB (˚) 75.5 80.9 3.4 –1.6*SN GoGn (˚) 44.9 32.9 5.2 2.3*** FMA (MP-FH) (˚) 36.8 25.1 4.5 2.6** Maxillo-Mandibular ANB (˚) 2.3 1.6 1.5 0.5 Maxillary Dentition U1 - NA (mm) 5.6 4.3 2.7 0.5 U1 - SN (˚) 105.5 102.4 5.5 0.6 Mandibular Dentition L1 - NB (mm) 6.9 4.0 1.8 1.6* L1 - MP (˚) 79.8 95.0 7.0 –2.2** Soft T i ssue Lower Lip to E-Plane (mm)–2.4 –2.0 2.0 –0.2 Upper Lip to E-Plane (m m)–7.0 –3.5 2.0 –1.7*  C. Carmine et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 36-44 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 40 3. CASE REPORT 2 3.1. Diagnosis The female 13-year-old patient showed a deviation of the menton to the right, a concave profile with short and retruded upper lip, and poorly accentuated zygomatic bone upon clinical examination (Figure 11). The con- tracted upper arch was in permanent dentitio n and a spa- tial deficit was evident in the regions of elements 12-13- 15-22-23. The mandibular arch was in late mixed denti- tion and crowding was noted in the anterior region. Analysis of the occlusion sagittally showed a Class II molar and canine relationship and cross bite throughout the anterior section, while open bite in the median sec- tion was noted upon vertical analysis and deviation of the lower median line to the right due to mandibular slipping was seen on the transversal plane (Figure 12). Functional examination revealed dual bite from man- dibular slipping to the right due to pre-contacts. The patient reported mixed breathing with frequent episodes of nasal obstruction. Panoramic X -ray showed third mo- lar buds. No evidence of dentoperiodontal pa t hol o gy was noted (Figure 13). Malocclusion with characteristics of skeletal pathology was observed by cephalometry; the vertical relationships showed severe skeletal hyperdi- vergence, wh ile from the sagittal perspective the maxilla was revealed to be retruded, the inclination of the upper and lower incisors reflected dental compensation for the skeletal malocclusion and an inverted position of the lips with respect to the aesthetic line (Figure 14). Figure 11. Extraoral photographs before treatment. Figure 12. Intraoral photographs before treatment. Figure 13. Panoramic X-ray before treatment. Figure 14. L-L teler adiogra phy before treatmenent. 3.2. Treatment Objectives We proposed to treat the problems evidenced in the di- agnosis using transversal expansion of the upper jaw, with elimination of the pre-contacts deflecting the man- dible and improvement of respiratory function, ortho- paedic advancement of the upper jaw, resolution of up- per and lower crowing, normalisation of overjet and overbite, and improvement of the frontal and lateral aes- thetic of the face.  C. Carmine et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 36-44 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 41 Figure 15. Cephalometric trace before treatment. 3.3. Treatment Progress A rapid palatal expander and Delaire’s posteroanterior traction were used to treat the contraction and retrusion of the upper jaw, respectively. The patient then under- went extraction of dental elements 14-24-34-44 and bidi- mensional technique fixed appliances (Boston Univer- sity) were applied to both arches. 0.016 and 0.018 × 0.025 pre-formed nickel-titanium archwires were em- ployed in alignment, and 0.016 × 0.022 steel wires with class I intramaxillary elastics and class III intermaxillary elastics were used to close the extraction spaces. Ideal 0.018 × 0.022 steel wires and vertical intermaxillary ela- stics were used for finishing, and retention was achieved by a Hawley retainer in the upper arch an d a 0.019 twist retainer from elements 33 to 43 in the lower. 3.4. Treatment Results Facial examination from the front upon termination of treatment showed better aesthetic balance and mandibu- lar symmetry, and the patient had an aesthetically pleas- ing smile. Lateral examination showed a much improved profile aesthetic, an evident reduction in the nasolabial angle and a re-equilibration of the relationship between upper and lower lip (Figure 16). Dental examination showed Class I molar and canine relationship, and nor- mal overjet, overbite and transversal relationships (Fig- ure 17). Functional examination showed a good incisive and canine guide, and normal opening movements, late- rality and protrusion. Orthopantomographical analysis revealed a slight mesioinclination of the root of element 15 and the presence of space for third molar eruption (Figure 18). Cephalometric values demonstrated sagittal improvement and vertical stability. Dental relationships were normal (Figures 19 and 20). 4. DISCUSSION The two cases analysed and treated both presented the Figure 16. Extraoral photographs after treatment. Figure 17. Intraoral photographs after treatment. Valori cefalometrici Maxilla to Cranial Base SNA(˚) 71.7 82.0 3.5 –2.9** Mandible to Cranial Base SNB (˚) 74.0 80.9 3.4 –2.0**SN GoGn (˚) 41.3 32.9 5.2 1.6 FMA (MP-FH) (˚) 31.0 26.0 4.5 1.1** Maxillo-Mandibular ANB (˚) –2.3 1.6 1.5 –2.6** Maxillary Dentition U1 - NA (mm) 6.5 4.3 2.7 0.8 U1 - SN (˚) 94.9 101.4 5.5 –1.2* Mandibular Dentition L1 - NB (mm) 4.9 4.0 1.8 0.5 L1 - MP (˚) 81.7 95.0 7.0 –1.9* Soft T i ssue Lower Lip to E-Plane (mm)–2.4 –2.0 2.0 –0.2 Upper Lip to E-Plane (mm)–7.8 3.2 2.0 5.5*****  C. Carmine et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 36-44 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 42 Figure 18. Panoramic X-ray after treatment. Figure 19. L-L teleradiography after treatmen. Figure 20. Cephalometric trace. Figure 21. Superimposition of pre- and post-treatment cephalometric traces at the cranial base, passing through points S and N. Superimpositions of the upper jaw were calculated on the bispinal plane, and superimpositions of the mandible on the gonion-menton plane. Valori cefalometrici Maxilla to Cranial Base SNA(˚) 73.3 82.0 3.5 –2.5** Mandible to Cranial Base SNB (˚) 73.6 80.9 3.4 –2.2**SN GoGn (˚) 41.9 32.9 5.2 1.7* FMA (MP-FH) (˚) 30.5 26.0 4.5 1.0* Maxillo-Mandibular ANB (˚) –0.3 1.6 1.5 –1.2* Maxillary Dentition U1 - NA (mm) 6.3 4.3 2.7 0.8 U1 - SN (˚) 96.2 101.4 5.5 –0.9 Mandibular Dentition L1 - NB (mm) 3.8 4.0 1.8 –0.1 L1 - MP (˚) 81.9 95.0 7.0 –1.9* Soft T i ssue Lower Lip to E-Plane (mm)–6.8 –2.0 2.0 –2.4** Upper Lip to E-Plane (mm)–10.4 3.2 2.0 –6.8****  C. Carmine et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 36-44 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 43 characteristics of third class malocclusion with a den- toskeletal component characterised by maxillary retru- sion and mandibular protrusion. These characteristics were noted upon clinical examination and subsequently confirmed by cephalometric analysis. Considering the type of malocclusion and the age of the patient, we de- cided to intervene immediately with the abovementioned orthopaedic treatment, using a rapid expander to correct the transversal dimension of the maxilla and postero- anterior extraoral traction to correct the sagittal discrep- ancy. From the literature it can be evinced that the best period to commence this treatment is early mixed denti- tion and Merwin et al. demonstrated that the skeletal effects of this orthopaedic treatment are evident up to 12 years of age [20]. Following on from these studies we applied these de- vices to patients who had just turned 13 in an attempt to open up their mandibular sutures. The treatment met with success and evident skeletal changes were seen: post-treatment cephalometry revealed an increase in the SNA angle of about 1.5˚ in both cases treated, while the SNB did not change appreciably. This result was due to the growth induced in the upper jaw which compensated for the mandibular excess. Extraction compensated for the sagittal skeletal discrepancy, normalising the overjet and overbite relationship. Furthermore the extractions allowed us to resolve the crowding in both arches. Su- perimposition of the pre- and post-treatment traces showed the effect of the extractions, which permitted retrusion of the incisors and advancement of the molar, consenting achievement of the first class dental molar and canine relationship. From the superimpositions and cephalometric values it can be observed that the incisors underwent a bodily m ovem ent without si gnificant changes in their buccal-lingual inclination. The transversal ex- pansion of the maxilla also permitted improvement of the patient as well as function, eliminating the obstacles deflecting the mandible. Correction of the anterior sector permitted resolution of the signs of periodontal damage seen prior to treatment in the first case. The satisfactory occlusion and the appreciable aes- thetic results obtained were due to the young age of the patients treated, the choice of extraction for dentoalveo- lar compensation and to good collaboration in the appli- cation of traction and inter and intramaxillary elastics. 5. CONCLUSIONS Our study proposed to evaluate the efficacy of orthopae- dic treatment carried out with a rapid palatal expander and Delaire’s posteroanterior extraoral traction in two growing patients presenting Class III malocclusion char- acterised by maxillary retrusion. At the end of treatment it was possible to appreciate the efficacy of these devices in normalising the sagittal and transversal discrepancies of the maxillary and mandibular bases an d balancing the profile, thus obtaining a satisfactory aesthetic. Having exploited the patients’ young age (acting with the correct timing) and used the extractive space to compensate for skeletal alterations, we achieved excellent results with- out surgery, which would probably have been necessary to achieve comp arable results in an older patient. REFERENCES [1] Proffit, W.R. (2007) Contemporary orthodontics. 4th Edition, Mosby, St Louis, 689-707. [2] Angelika Stellzig-Eisenhauera Christopher J. Lux and Gabriele Schuster. (2002) Treatment decision in adult patients with Class III malocclusion: Orthodontic therapy or orthognathic surgery? American Journal of Ortho- dontics and Dentofacial, 122, 27-38. [3] Mackay, F., Jones. J.A., Thompson, R. and Simpson, W. (1992) Cranio-facial form in Class III cases. British journal of orthodontics, 19, 15-20. [4] Ngan, P., Hagg, U., Yiu, C., Merwin, D. and Wie, S.H. (1997) Cephalometric comparisons of Chinese and Caucasian surgical Class III patients. International Jour- nal of Adult Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery, 12, 177-188. [5] Jacobson, A., Evans, W.G., Preston, C.G., Sadowsky, P.L. (1974) Mandibular prognathism. American Journal of Orthodontics, 66, 140-171. doi:10.1016/0002-9416(74)90233-4 [6] Dahera, W., Caron, J. and Wechslerc, M.H. (2007) Nonsurgical treatment of an adult with a Class III malocclusion, American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial, 132, 243-251. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.02.034 [7] Cozza, P., Di Girolamo, R. and Nofroni, I. (1995) Epidemiologia delle malocclusioni su un campione di bambini delle scuole elementari del Comune di Roma. ortognatodonzia (Italian), 4, 217-228. [8] Silva, R.G. and Kang, D.S. (2001) Prevalence of malocclusion among Latino adolescents. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 119, 313-315. doi:10.1067/mod.2001.110985 [9] Kanno, Z., Kim, Y. and Soma, K., Early correction of a developing skeletal Class III malocclusion, The Angle Orthodontist, 77, 549-556. doi:10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077[0549:ECOADS]2.0.C O;2 [10] Dietrich, U.C. (1970) Morphological variability of skeletal Class III relationships as revealed by cepha- lometric analysis. Report of the Corgress, European Orthodontic Society, 46, 131-143. [11] Guyer, E.C., Ellis, E.E., McNamara, J.A. and Behrents, R.G. (1986) Components of Class III malocclusion in juveniles and adolescents. Angle Orthodontist, 56, 7-30. [12] Lin, J.X. and Gu, Y. Preliminary Investigation of Nonsurgical Treatment of Severe Skeletal Class III Malocclusion in the Permanent Dentition. Angle Ortho- dontis, 73, 401-410. [13] Baccetti, T., McGill, J.S., Franchi, L., McNamara Jr, J.A.  C. Carmine et al. / Open Journal of Stomatology 1 (2011) 36-44 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJST 44 Tollaro, J. (1998) Skeletal effects of early treatment of Class III malocclusion with maxillary expansion and face-mask therapy. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 113, 333-343. doi:10.1016/S0889-5406(98)70306-3 [14] Haas, A.J. (1965) Treatment of maxillary deficiency by opening the midpalatal suture. Angle Orthodontist, 65, 200-217. [15] Haas, A.J. (1970) Palatal expansion: Just the beginning of dentofacial orthopedics. American Journal of Ortho- dontics, 57, 219-255. doi:10.1016/0002-9416(70)90241-1 [16] McNamara Jr, J.A. and Brudon, W.L. Orthodontic and orthopedic treatment in the mixed dentition. Needham Press, Ann Arbor, 1993. [17] Fields, H.W. and Proffit, W.R. (2000) Treatment of skeletal problems in preadolescent children. In: Proffit, W.R. and Fiel ds, H.W. Eds., Contemporary Orthodontics, 3rd Edition, Mosby, St Louis, 511-515. [18] McNamara, J.A. (1994) Mixed dentition treatment. In: Graber, T.M. and Vanarsdall, R.L. Eds., Orthodontics- Current Principles and Techniques. Mosby Year Book, St Louis, 508. [19] Hickham, J.H. 1991, Maxillary protraction therapy: Diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Ortho- dontics, 25, 102-113. [20] Merwin, D., Ngan, P., Hagg, U., Odont, Dr., Yiu, C. and Wei, S.H.Y. (1997) Timing for effective application orthopedic force to the maxilla of anteriorly directed. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Or- thopedics, 112, 292-299. doi:10.1016/S0889-5406(97)70259-2 [21] De Toffol, L., Pavonia, C., Baccetti, T., Franchi L. and Cozza, P. (2008) Orthopedic treatment outcomes in Class III malocclusion. A systematic review, Angle Ortho- dontist, 78, 561-573. doi:10.2319/030207-108.1 |