Psychology 2011. Vol.2, No.3, 155-161 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/psych.2011.23025 Associations between Dispositional Humility and Social Relationship Quality Annette Susanne Peters1, Wade Clinton Rowatt2, Megan Kathleen Johnson2 1University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, USA; 2Baylor University, Waco, USA. Email: wade_rowatt@baylor.edu Received March 16th, 2011; revised April 18th, 2011; accepted May 19th, 2011. Quality social relationships depend, in part, on deferring self-interest to another person or group. Being too ar- rogant or self-focused could negatively affect relationship quality. In two studies we examined possible connec- tions between trait humility and social relationship quality (SRQ). Participants completed survey measures of each construct. Self and peer-reported humility correlated positively with SRQ, even when social desirability (Study 1) and other relevant personality dimensions (e.g., Big Five, agency, communion) were statistically con- trolled (Study 2). These findings indicate humility could be an important trait with regard to interpersonal rela- tions. Implications are discussed for the cultivation of humility and its potential relevance in other social con- texts. Keywords: Humility, Relationship Quality, Positive Psychology, Well-Being Introduction Forming and maintaining quality social relationships with family, friends, and co-workers may depend, in part, on the ability to humbly defer self-interest to others. Expressing too much arrogance or self-focus could negatively affect relation- ships. Building on previous research which connected Big Five personality dimensions and relationship satisfaction (Malouff, Thorsteinsson, Schutte, Bhullar, & Rooke, 2010), we investi- gated the possible association between understudied trait hu- mility and social relationship quality. We also examined whether the association between humility and relationship qual- ity persisted when other important personality constructs were controlled. The primary purpose of this research, however, was to examine the relationship between humility and social rela- tionship quality. By social relationship quality (SRQ) we sim- ply mean the degree to which one is happy or satisfied with social relationship partners, such as friends or roommates. SRQ is very similar to marital satisfaction (Norton, 1983) but is more appropriate for study among non-married college students who comprised our samples. Humility Defined Humility has been identified as a part of a sixth personality dimension (Lee & Ashton, 2004) and conceptualized as a virtue or character strength (Exline et al., 2004; Tangney, 2002, 2009). Consistent with both conceptualizations, we define humility as a characteristic and enduring way of being more humble, mod- est, respectful, and open-minded than arrogant, self-centered, or conceited. Like other theorists (Davis, Worthington, & Hook, 2010; Landrum, 2011; Tangney, 2009), we contend humility is not simply the absence of negative qualities but also the pres- ence of positive qualities. That is, a humble person does not simply lack arrogance or self-focus, but also possesses humble qualities like being modest or intellectually open (Roberts & Wood, 2003). The trait or virtue of humility may include several facets and specific behavioral tendencies. For example, humble persons are likely down-to-earth (i.e., easy with whom to relate), will- ing to admit limits, not self-centered (Emmons, 2000; Exline et al., 2004; Myers, 1995; Rowatt et al., 2006), rarely call atten- tion to the self, and prefer not to stand out in a crowd (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Humble persons may also accurately assess personal characteristics and abilities relative to others (Tangney, 2002) rather than inflate self-evaluations. Possible Connections between Humility and Social Relationship Quality Why might humility and relationship quality be connected? One team of scholars noted that humility includes important relational characteristics, such as a recognition one cannot control all social encounters, an attitude of patience- gentleness with other people, and a sense of empathy (Means, Wilson, Sturn, Biron, & Back, 1990). By being patient, gentle, non-controlling, empathetic, or realizing similarities with others (Worthington, 1998), humble persons may set the stage for quality relationships. That humble persons are probably liked more than their ar- rogant counterparts could also impact relationship quality (Landrum, 2011). When asked to describe a very humble per- son, and why the person was viewed as humble, a majority of participants mentioned humble individuals’ kindness or caring toward others (Exline & Geyer, 2004). There are ties between humility and other pro-social qualities as well that could in- crease relational well-being. For example, Worthington (1998) posited humility was critical in the process of forgiving a fam- ily member. Powers et al. (2007) found that self-reported hu- mility and forgiveness correlated positively. People have been  A. S. PETERS ET AL. 156 found to be cooperative in a bargaining game with a self-ef- facing, humble person they expected to meet (Marlowe, Gergen, & Doob, 1966). Honest-humble persons were observed to be cooperative in an economic game (Hilbig & Zettler, 2009). Humble persons have offered more help to a person in need than less humble persons (LaBouff, Rowatt, Johnson, Tsang, & McCullough, 2010). That humility has been associated with positive qualities and behaviors (e.g. forgiveness, cooperation, helping) provides further support for a possible humility-rela- tionship quality connection. Hypotheses and Predictions Study 1 examined whether measures of dispositional humil- ity and social relationship quality were related. We predicted humility and relationship quality would correlate positively. Whereas humility and relationship quality appear to be socially desirable traits, it was important to include a measure of im- pression management for use as a statistical control. Further- more, because some humble persons might not self-report being humble, we also assessed participant humility with peer-ratings. Study 1 Method Participants A sample of 109 college students (87 women; M age = 19 years) participated to fulfill a course requirement or for extra credit. The sample was somewhat ethnically diverse (62% Caucasian, 12% Asian, 12% Hispanic, 7.4% Black, 1% Ameri- can Indian, 5.6% selected “other”). In addition, the humility of 63 participants was rated by a close acquaintance who returned by mail a brief printed survey. Measures and Procedure Self- and other-reported trait humility was assessed with a seven-item semantic differential scale (Rowatt et al., 2006). We used this humility measure, in part, to assess humility inde- pendently from honesty (cf. Lee & Ashton, 2004) or modesty (cf. Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The following terms appeared between 7-point rating scales: arrogant/humble, immodest/ modest, disrespectful/respectful, egotistical/not self-centered, conceited/not conceited, intolerant/tolerant, and closed-minded/ open-minded. Higher scores indicated more humility. The sim- ple statement, “I see myself as...,” was printed at the top of the page. To obtain ratings of participants’ humility from other persons, participants were asked to give an envelope containing the same humility measure to someone who knew them well. An instruction on the peer-report survey read, “Please circle the number that best describes this person on each trait below.” The peer-rater then returned the survey by mail. To assess social relationship quality, we revised the Quality Marriage Index (Norton, 1983) to apply to unmarried individu- als. For example, the item “Our marriage is strong” was changed to “My social relationships are strong.” Respondents were instructed, “The following items refer to your social rela- tionships (i.e., friends, roommates).” The following five items were rated by the participant (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = neutral, 7 = strongly agree): I have good social relationships; My social relationships are very stable; My social relationships are strong; My social relationships make me happy; I feel like part of a team in my social relationships. Higher scores indicated higher perceived SRQ. Respondents also completed the 20-item impression-management subscale of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR-IM) (Paulhus & Reid, 1991). Results and Discussion As shown in Table 1, self-reported and other-reported humil- ity correlated positively with social relationship quality (rs = .27 and .31, respectively). However, both self- and other- reported humility correlated with impression management (both rs = .31), so we computed partial correlations. Both self- and other-reported humility still correlated significantly with SRQ when impression management was statistically controlled (par- tial rs = .19 and .29). No gender difference on self-reported humility was found (Men: M = 5.24, SD = .78; women: M = 5.53, SD = .76), F(1,107) = 2.33, p = .13. However, women were rated by others to be more humble (M = 5.88, SD = .80) than men (M = 5.01, SD = 1.56), F(1,59) = 7.35, p = .009. When controlling for gender, the correlations persisted between social relationship quality and self-reported humility (partial r = .27, p = .005) and peer-reported humility (partial r = .32, p = .015). No gender difference was found on SRQ. We also found self-reported and other-reported humility cor- related positively (r = .33, p = .02). This is important because it could be argued humble persons do not self-report being hum- ble. That self and other ratings of humility correlated positively suggests some agreement of others with self-assessments of humility. Table 1. Study 1: zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics. 1 2 3 Mean SD α 1. Humility (self-report, n = 109) - .31* .19* 5.47 .77 .75 2. Humility (peer-report, n = 63) .33* - .29* 5.71 1.05 .89 3. Quality of social relationships .27** .31* - 5.82 1.13 .93 4. Impression management .31** .13 .31* .30 .16 .70 Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; partial correlations controlling for impression management appear above the diagonal and zero-order bivariate correlations appear below the diagonal.  A. S. PETERS ET AL. 157 Study 2 Study 1 revealed a positive relationship between humility and social relationship quality (SRQ) even when social desir- ability and gender were statistically controlled. In Study 2 we examined whether the humility-relationship quality connection remained when statistically controlling for the Big Five person- ality dimensions and other personality variables implicated in social well-being (i.e., agency, communion; Bakan, 1966; Hel- geson, 1994). We are not the first to suggest that a personality dimension like humility might account for unique variability in important social processes. Honesty-humility was found to better predict negative qualities like self and other-reported materialism, ethical violations, and criminality (all inversely) than other personality dimensions (Ashton & Lee, 2008). This is a preliminary indication that trait humility will account for unique variability in relationship-relevant constructs when the Big Five are statistically controlled. Humility, the Big Five, and Subjective Well-being Previous research has revealed connections between self- reported humility, the Big Five personality dimensions, and personal life satisfaction (Rowatt et al., 2006). In specific, self-reported humility correlated positively with agreeableness, openness, and personal satisfaction with life, negatively with neuroticism, and negligibly with conscientiousness and extra- version (Rowatt et al., 2006). In a large meta-analysis, neuroti- cism was found to be negatively related to subjective well- being measures, whereas extraversion, agreeableness, conscien- tiousness, and openness were shown to be positively related to subjective well-being (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998). Longitudinal research has also implicated husbands’ and wives’ neuroticism in marital dissatisfaction and divorce (Kelly & Conley, 1987). Given these patterns, it could be the relationship between hu- mility and SRQ we found in Study 1 was an artifact of the Big Five or another personality dimension. Humility, Agency/Communion, and SRQ We also investigated whether the association between humil- ity and relationship quality was due in part to personal qualities like agency or communion. Somewhat unlike humble persons, agentic individuals are self-focused, independent, and seek to separate from others (Helgeson, 1994). Similar to humble per- sons, communal people focus more on others than the self and strive to connect with others (Helgeson, 1994). Agency and communion can also be unmitigated (Helgeson, 1994). For example, agency unmitigated by communion or unmitigated agency (UA) refers to “a focus on the self to the exclusion of others” (Helgeson & Fritz, 1999: p. 132), and was operationalized with terms like arrogant, boastful, and egotisti- cal (see Spence, Helmreich, & Holahan, 1979). UA is a con- ceptual opposite of humility. Unmitigated communion (UC) refers to “a focus on others to the exclusion of the self” (Hel- geson & Fritz, 1999: p. 132) and was assessed with items like, “I always place the needs of others above my own” and “Even when exhausted, I will always help other people” (see Helgeson & Fritz, 1999). Previous research has revealed that both UA and UC were inversely associated with personal and relational well-being. For example, UA and UC were positively associated with fre- quency of negative social interactions when sex, agency, and communion were statistically controlled (Helgeson & Fritz, 1999). UA and UC were also negatively related with general well-being when sex and communion were controlled statisti- cally (Helgeson & Fritz, 1999). Hypothesis and Predictions Whereas humble persons are less self-centered, we predicted a measure of trait humility would correlate negatively with measures of agency and unmitigated agency. Whereas humble persons may strive to connect with others, we predicted a measure of trait humility would correlate positively with com- munion and unmitigated communion. Some humble persons may be so humble they neglect the self relative to others. Fi- nally, we hypothesized humility accounts for unique variability in SRQ above and beyond the Big Five, agency, or communion. Method Participan t s, M aterials, and Procedure A convenience sample of 258 undergraduate students com- pleted an online survey (198 women, M age = 19 years). The sample was somewhat diverse with regard to ethnicity: 56% Caucasian, 17% Hispanic, 14% Asian, 10% African American, 2% other ethnicity, and 1% Native American. Participants re- ceived one credit that satisfied a course research participation requirement or extra credit. Trait humility, social relationship quality, and impression management were assessed with the self-report measures de- scribed in Study 1. The Extended Personal Attributes Ques- tionnaire (Spence et al., 1979) was used to assess agency, communion, and unmitigated agency. The Revised Unmitigated Communion Scale (Helgeson & Fritz, 1999) was used to meas- ure unmitigated communion (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). On the Extended PAQ, two items appeared between a 5-point scale as a semantic differential (i.e., 1 = not at all arro- gant, 5 = very arrogant). Example agency items included inde- pendent, competitive, and feels very superior. Example com- munion items included easy to devote self to others, gentle, and aware of other’s feelings. Example unmitigated agency items included: arrogant, boastful, and looks out for self. An example unmitigated communion item was, “I always place the needs of others above my own.” Gosling, Rentfrow, and Swann’s (2003) measure of the Big Five was used to assess extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, conscientiousness, and emotional stability. An example extraversion item was: “extra- verted, enthusiastic” (1 = disagree strongly, 7 = agree strongly). Results Humility correlated positively with relationship quality (r = .24; see Table 2), even when impression management was controlled (partial r = .17, p < .05).1 This replicates Study 1. In 1Descriptive statistics and internal consistency estimates for Study 2 are provided in Table 2 (last three columns). Because each Big Five facto contained only two items, Cronbach alphas were not computed for those subscales. With increased sample size, we found women self-reported more humility than men (women M = 5.44, SD = .84; men: M = 5.10, SD= .69), (1,257) = 10.07, p = .002. As in Study 1, no gender difference in relation- shi ualit was found.  A. S. PETERS ET AL. 158 addition, humility was negatively correlated with unmitigated agency and neuroticism, and positively correlated with agree- ableness, communion, unmitigated communion, and conscien- tiousness. Hierarchical regression analyses were used to investigate whether humility accounted for unique variability in SRQ above and beyond the Big Five. In the first step, the Big Five personality factors were entered (see Table 3, Model 1 col- umns). In the second step, humility was entered (see Table 3, Model 2 columns). Humility accounted for unique variability in relationship quality when the Big Five were simultaneously con- trolled. Extraversion and neuroticism (inversely) were also asso- ciated with SRQ in models one and two (see Table 3). When gender was added to these regression models, the patterns were virtually unchanged; gender was unrelated to relationship quality. A similar approach was used to examine whether humility accounted for unique variability in SRQ above and beyond gender, agency, communion, unmitigated agency, and unmiti- gated communion. Because men tend to be agentic and women tend to be more communal, gender was included in these regres- sion models. In the first step of the regression analysis we entered gender, agency, communion, unmitigated agency, and unmitigated communion (see Table 4, Model 1 columns). Humility was entered in the second step (see Table 4, Model 2 columns). Both agency and communion were positively associated with SRQ (see Table 4). The influence of humility on relationship quality was marginally significant with a two-tailed signifi- cance test. Given our a priori directional prediction (i.e., humil- ity will be positively correlated with relationship quality) and Table 2. Study 2: zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics. Personality/Self-Concept Measures 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 MeanSD 1. Humility Semantic Differential - 5.37.74.71 2. Quality of Marriage Index .24***- 5.651.25.92 4. Agency −.06 .24** - 3.42.62.75 5. Communion .39***.31*** .04 - 4.02.54.76 6. Unmitigated Agency −.67** −.20** .18* −.47** - 2.44.56.75 7. Unmitigated Communion .22***.12 −.06 .44***−.30** - 3.54.58.70 8. Extraversion −.05 .31*** .44** .22***.09 .14* - 8.703.25- 9. Agreeableness .40*** .25*** −.12 .52***−.56** .30***.02 - 10.732.43 - 10. Conscientiousness .18** .16** .25** .16** −.29** .06 .04 .19** - 11.022.45 - 11. Neuroticism −.19** −.27*** −.26** .03 .19** .16* −.04 −.25***−.15* - 6.742.91- 12. Openness .11 .15* .27** .11 .00 −.01 .25***.08 −.05 −.16* - 10.382.17- 13. BIDRIM .30*** .25*** .16* .20***−.43***.21***.05 .27***.34***−.18** −.05 - 17.02.18.76 Note: * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. * For Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness two item inter-correlations were reported in the alpha columns. Table 3. Study 2: multiple regressions of relationship quality on big five traits (Model 1) and humility (Model 2). Model 1 Model 2 β T β t F change R2 change Extraversion .28 4.91*** .30 5.15*** Agreeableness .17 2.96** .12 1.96 Conscientiousness .09 1.57 .07 1.29 Neuroticism −.20 −3.38** −.19 −3.22** Openness .04 <1 .03 <1 Humility - - .15+ 2.40* R2 .20 .22 F 13.25*** 12.21** 5.74* .02* Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.  A. S. PETERS ET AL. 159 Table 4. Study 2: multiple regressions of relationship quality on agency, communion (Model 1) and humility (Model 2). Model 1 Model 2 β t β t F change R2 change Sex −.01 <1 −.02 <1 Agency .25 4.22*** .24 4.11*** Communion .24 3.39** .26 3.29** UA −.13 −1.91+ −.05 <1 UC −.01 <1 −.01 <1 Humility - - .13 1.74+ R2 .16 .17 F 9.52*** 8.50*** 2.75* .01* Note: + p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001; sex (male = 0, female = 1), UA = unmitigated agency, UC = unmitigated communion. F change is a test for the differ- ence between models one and two (when humility was added). direct observation of this in Study 1, it was appropriate to use a one-tailed significance test (i.e., p < .099/2 < .05). As such, we concluded humility accounts for unique variability in relation- ship quality when the Big Five or agency/communion variables were statistically controlled. General Discussion The positive correlation between humility and social rela- tionship quality observed in Study 1 replicated in Study 2. We also found self-reported humility correlated positively with SRQ, even when the Big Five and agency-communion vari- ables were controlled in separate regression models. These findings indicate trait humility could be important for social relationships. It should also be noted that extraversion, neuroti- cism (inversely), agency, and communion also account for unique variability in social relationship quality. These patterns fit with previous research about extraversion and happiness (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998) and agency/communion and well- being (Helgeson, 1994). We encourage psychologists and researchers in other related disciplines to consider the role of humility in relationships and other domains. As psychological science has developed, more attention has been placed on negative traits like narcissism, which affect interpersonal relationships, and for good reasons. In contrast to humility, some people think and act like they are the center of the universe (i.e., narcissists). Narcissists have an unstable overly positive sense of self that could, over time, be relationally repulsive. Narcissism is not the exact opposite of humility, but measures of the two constructs are inversely re- lated (Rowatt et al., 2006). Furthermore, as narcissism increases, perceptions of humility as a positive quality decrease (Exline & Geyer, 2004). Unlike humility, however, narcissism is associ- ated with a variety of relationship problems. For example, nar- cissism correlates with qualities linked to exploitation of others (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Facets of narcissism, such as enti- tlement or arrogance, appear to contribute to unstable or poor social relationships and other self-defeating behaviors (Vazire & Funder, 2006). Although narcissists were perceived initially by others as agreeable and well-adjusted, they were rated more negatively after group interactions (Paulhus, 1988). Potential Benefits of Humility Relative to Narcissism In contrast with narcissism, we suggest humility has potential personal, relational, and organizational benefits. At the personal level, humility has been found to correlate positively with aca- demic performance even when other known correlates of good grades were controlled (Owens, 2009; see Rowatt et al., 2006, Study 2). Realizing that one does not know and being open to learning could facilitate intellectual growth and progress. At the relational level, Studies 1 and 2 reveal humility correlated with relationship quality even when other personality dimensions were controlled. Humbly recognizing one cannot control others and being patient, gentle, and empathic with others (cf. Means et al., 1990) may also facilitate relational well-being. At the organizational level, Collins (2001, 2005) discovered compa- nies with CEOs who possessed a paradoxical combination of humility and strong professional will went from being merely “good” to being “great” (as measured by stock performance). Johnson, Rowatt, and Petrini (2011) found that honesty-humility predicts supervisor ratings of job performance. Humility could have other benefits for organizations as well (see Owens, Ro- watt, & Wilkins, 2011). Future Direc t io ns a nd Cautions Future research should examine how humility affects out- comes in business, industry, education, law, medicine and other contexts. We suspect humility is important for some, but not all contexts. For example, humility might not predict performance in competitive sales environments or public performers who depend on self-promotion for success. A few limits and possible alternative interpretations also merit brief discussion. Given the correlational design, we can- not determine the causal nature of the humility-relationship quality connection. We suggest humility increases relational quality, but the reverse is possible. Experiencing quality social relationships could engender humility in individuals. Perhaps being among close friends leads to less focus on the self that increases personal humility.  A. S. PETERS ET AL. 160 Measurement of humility also merits brief discussion. De- spite its perceived value (Exline & Geyer, 2004), agreement among theorists that humility is a positive quality (Exline et al., 2004; Tangney, 2009), and representation in many languages (Ashton et al., 2004), the construct of humility has received very little empirical attention from personality researchers. Part of the challenge appears to be there is not a gold-standard measure of humility (Davis et al., 2010; Tangney, 2009). We used a brief measure of humility that is relatively independent from modesty or honesty. Other existing scales assess humility in combination with qualities like modesty (i.e., Peterson & Seligman, 2004) or honesty (i.e., Lee & Ashton, 2004), or indi- rectly through estimates of the degree to which humble quali- ties are liked (Landrum, 2011). At this time, our purpose is not to say one definition or measure is best. Each conceptualization captures some of the essence of humility. Trait humble persons are likely modest (Exline et al., 2004), honest (Ashton & Lee, 2008), and less arrogant (Rowatt et al., 2006) than less humble persons. Meas- ures of humility-modesty, humility-honesty, and humility-ar- rogance likely correlate positively. A gold-standard measure may emerge as data and findings accumulate. Readers who plan to study humility are encouraged to consult Davis et al. (2010) for a more thorough discussion of measurement issues. In closing, perhaps paradoxically, humility appears to be an important quality. Future research is needed to determine whether state or trait humility is connected with other positive outcomes and whether state or trait humility can be cultivated. We speculate state humility can be induced by broadening one’s perspective and contemplating how small (but not neces- sarily insignificant) one is relative to the known universe. If trait humility can be developed, it could have even more lasting and enduring personal and social benefits. References Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2008). The HEXACO model of personality structure and the importance of the H factor. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1952-1962. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00134.x Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., Perugini, M., Szarota, P., De Veries, R. E., Di Blas, L., Boies, K., & De Raad, B. (2004). A six-factor structure of personality-descriptive adjectives: Solutions from psycholexical stud- ies in seven languages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 356-366. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.356 Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally. Collins, J. (2001). Good to great. New York, NY: Harper, Collins. Collins, J. (2005). Level 5 leadership: The triumph of humility and fierce resolve. Harvard Business Review, 7, 136-146. Davis, D. E., Worthington, E. L., & Hook, J. N. (2010). Humility: Review and measurement strategies and conceptualization as person- ality judgment. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 243-252. doi:10.1080/17439761003791672 DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197-229. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197 Emmons, R. A. (2000). Is spirituality an intelligence? Motivation, cognition, and the psychology of ultimate concern. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 10, 3-26. doi:10.1207/S15327582IJPR1001_2 Exline, J. J., Campbell, W. K., Baumeister, R. F., Joiner, T., Krueger, J., & Kachorek, L. V. (2004). Humility and modesty. In C. Peterson and M. Seligman (Eds.), The values in action (VIA) classification of strengths (pp. 461-475). Cincinnati, OH: Values in Action Institute. Exline, J. J. & Geyer, A. L. (2004). Perceptions of humility: A prelimi- nary study. Self and Identity, 3, 95-114. Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big Five personality domains. Journal of Re- search in Personality, 37, 504-528. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1 Helgeson, V. S. (1994). The relation of agency and communion to well-being: Evidence and potential explanations. Psychological Bul- letin, 116, 412-428. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.412 Helgeson, V. S., & Fritz, H. L. (1999). Unmitigated agency and un- mitigated communion: Distinctions from agency and communion. Journal of Research in Personality, 33, 131-158. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1999.2241 Hilbig, B. E., & Zettler, I. (2009). Pillars of cooperation: Hon- esty-Humility, social value orientations, and economic behavior. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 516-519. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.01.003 Johnson, M. K., Rowatt, W. C., & Petrini, L. (2011). A new trait on the market: Honesty-humility as a unique predictor of job performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 857-862. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.011 Kelly, E. L., & Conley, J. J. (1987). Personality and compatibility: A prospective analysis of marital stability and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 27-40. Landrum, E. (2011). Measuring dispositional humility: A first ap- proximation. Psychological Reports, 108, 217-228 LaBouff, J. P., Rowatt, W. C., Johnson, M. K. Tsang, J. A., & McCul- lough, G. (2010). Humble people are more helpful than less humble persons: Evidence from three studies. Manuscript under review. Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO Personality Inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 329-358. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3902_8 Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Schutte, N. S., Bhullar, N., & Rooke, S. E., (2010). The five-factor model of personality and rela- tionship satisfaction of intimate partners: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 124-127. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.09.004 Marlowe, D., Gergen, K. J., & Doob, A. N. (1966). Opponent’s person- ality, expectation of social interaction, and interpersonal bargaining. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 206-213. doi:10.1037/h0022898 Means, J. R., Wilson, G. L., Sturm, C., Biron, J. E., & Bach, P. J. (1990). Humility as a psychotherapeutic formulation. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 3, 211-215. doi:10.1080/09515079008254249 Myers, D. G. (1995). Humility: Theology meets psychology. Reformed Review, 48, 195-206. Norton, R. (1983). Measuring martial quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 141- 151. doi:10.2307/351302 Owens, B. P. (2009). Humility in organizations: Establishing construct, nomological, and predictive validity. Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Academy of Manage- ment. Owens, B. P., Rowatt, W. C., & Wilkins, A. L. (2011). Exploring the relevance and implications of humility in organizations. In K. S. Cameron and G. M. Spreitzer (Eds.), Handbook of positive organiza- tional scholarship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Paulhus, D. L. (1988). Interpersonal and intrapsychic adaptiveness of trait self-enhancement: A mixed blessing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1197-1208. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1197 Paulhus, D. L., & Reid, D. B. (1991). Enhancement and denial in so- cially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 60, 307-317. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.2.307 Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 556-563. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6 Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and  A. S. PETERS ET AL. 161 virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; New York: Oxford University Press. Powers, C., Nam, R., Rowatt, W. C., & Hill, P. (2007). Associations between humility, spiritual transcendence, and forgiveness. In R. Piedmont (Ed.), Research in the social scientific study of religion (pp. 74-94). Herndon, VA: Brill Academic Publishers. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004158511.i-301.32 Roberts, C. R., & Wood, W. J. (2003). Humility and epistemic goods. In M. DePaul, & L. Zagzebski (Eds.), Intellectual virtue: Perspec- tives from ethics and epistemology (pp. 257-279). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Rowatt, W., Powers, C., Targhetta, V., Comer, J., Keenedy, S., & La- bouff, J. (2006). Development and initial validation of an implicit measure of humility relative to arrogance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 198-211. doi:10.1080/17439760600885671 Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R. L., & Holahan, C. K. (1979). Negative and positive components of psychological masculinity and femininity and their relationships to self-reports of neurotic and acting out behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1673-1682. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.10.1673 Tangney, J. P. (2002). Humility. In S. Lopez and C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (pp. 411-419). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Tangney, J. P. (2009). Humility. In S. J. Lopez and C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (pp. 483-490). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Vazire, S., & Funder, D. C. (2006). Impulsivity and the self-defeating behavior or narcissists. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 154-165. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_4 Worthington, E. L., & Jr. (1998). An empathy-humility-commitment model of forgiveness applied within family dyads. Journal of Family Therapy, 20, 59-76. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.00068

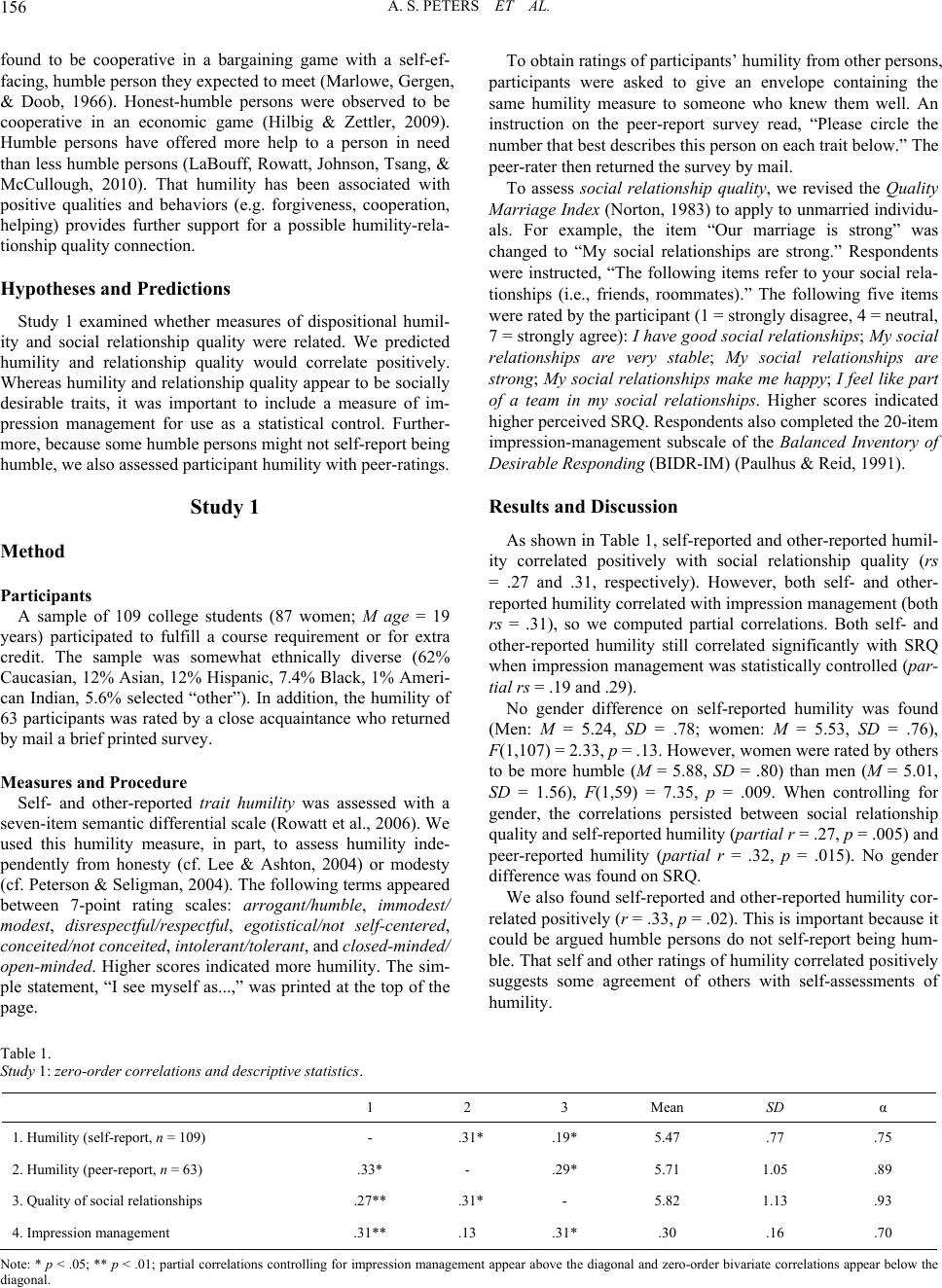

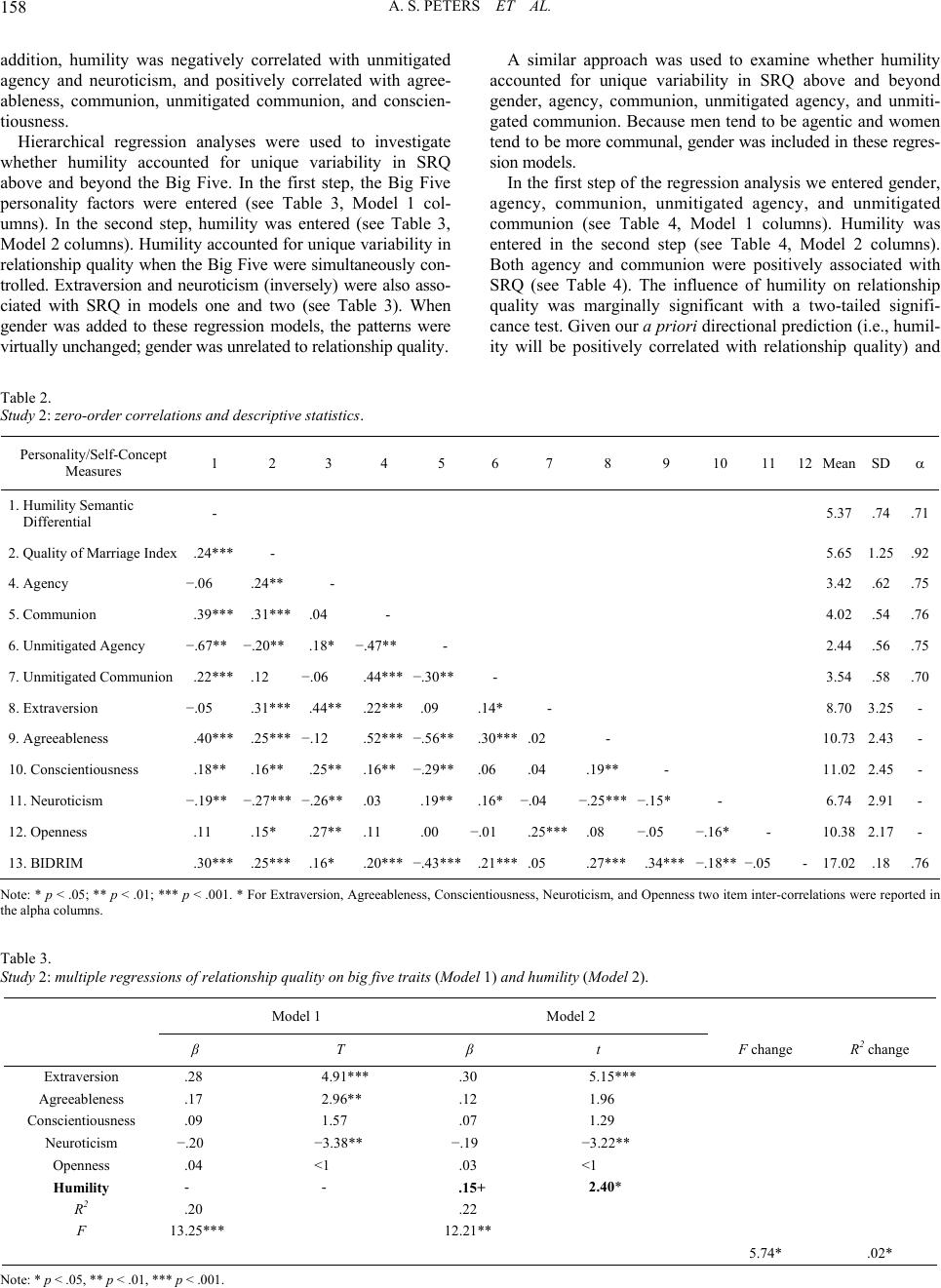

|