Vol.3, No.6, 343-356 (2011) doi:10.4236/health.2011.36059 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health Assessment of strategic management practice of malaria control in the Dangme West district, Ghana ——Article submitted to the West African College of Nursing for the award of a fellow Adelaide Maria Ansah Ofei School of Nursing, University Of Ghana, Legon, Ghana. adelaideofei@yahoo.com Received 23 February 2011; revised 1 April 2011; accepted 6 April 2011. ABSTRACT Strategic management (SM) practice was as- sessed in all HCFs both in the public and priv ate and some chemical shops within the Dangme West district using semi-structured question- naires. In-depth interviews were carried out with healthcare managers in their clinical setting. The study utilized both qualitative and quantita- tive methods in describing the SM practice. Healthcare managers were using all the ele- ments of SM in the management of malaria but these were not holistically coordinated. Present were short ranged informal planning based on the objectives of NMCP and day-to-day opera- tion of the HCFs especially with Ghana Health Service facilities. Due to homogenous nature of Dangme West district, management of culture wasn’t given much attention by healthcare managers though healthcare providers were acutely aware of its importance to quality ser- vice delivery. Competition was woefully absent in the healthcare environment. No formal struc- ture has been created for the management of malaria control activities with the exception of the involvement of Community Based agents. The district was widely implementing all the strategies of the NMCP with favourable outcomes. Keywords: Assessment; Strategic Management; Practice; Malaria Control; Dangme West 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Background The healthcare system in Ghana is con fro nted with the formidable task of improving and guaranteeing the health and well-being of all people living in Ghana. Such a broad goal encompasses many specific objectives for individuals and populations, e.g. increased life expec- tancy, reduction in avoidable deaths and improvement in quality of life. Recognizing that resources are never adequate, a rethinking and restructuring of priorities is inevitable at all levels. Thus, the health care system has since independence gone through series of progressive reforms intended to develop and improve public health practice in Ghana. Prominent among these reforms, are the adoption of Primary Health Care (PHC) concept, creation of the Ghana Health Service by an act of par- liament (Act 525), development of the Medium Term Health Strategy (MTHS) and a 5-year Programme of Work (PoW). In all these developmental approaches malaria control has been given some form of promi- nence. Malaria as a public health challenge seems to be on the increase globally with over 1 - 2 million deaths each year. Over 90% of these are African children who due to poor access to health care facilities and local perceptions about the disease fail to seek prompt help. Indeed, ma- laria is accredited to be a major cause of poverty and low productivity especially in poor countries [19]. It is esti- mated that the annual economic burden of malaria in Africa is about US$ 1.7 billion or 1% of the Gross Do- mestic Product. In Ghana, malaria is hyper-endemic and accounts for more than 44% of reported out-patient visit and an estimated 22% of under-5 mortality. Reported cases however, represent only a small fraction of the actual number of malaria episodes in the population be- cause the majority of people with symptomatic infec- tions are treated at home and not reported [11]. Malaria is a life threatening disease in individuals with low or impaired immunity, but malaria is both pre- ventable and curable. Ghana therefore, has identified Malaria as one of its priority diseases targeted for con- trol in the medium term. Resources are sent directly by the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP), with support from the Global Fund, Development Partners, etc. to the district for the management of malaria and  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 344 other diseases of public health concern to help strengthen decentralization (MTHS, 1995). For instance available data at the NMCP office showed that from 2004 to 2006 first quarter, a total of thirty thousand and one dollars, ninety seven cents ($30,001.97c) was sent to the Dangme West district health directorate for malaria con- trol activities. The issue is, what management processes have these healthcare managers (HCMs) put in place to cope with the increasing trend of morbidity and mortal- ity associated with malaria? Strategic management (SM) according to Duncan [10] is a major thrust that would guide the management of healthcare organizations to anticipate and cope with the variety of external forces operating beyond their control. “Strategic” is the most overused word in the vocabu- lary of business. Frequently, it is just another way of saying, “this is important”, but the aim of true strategy is to master environment by understanding and anticipatin g the actions of other economic agents, especially com- petitors [16]. A strategy to a program is amongst other things a plan of how the program can achieve its goals and objectives [6,26]. It is a ‘commitment of present resources to future expectations’ [9]. The aim of SM is to decide on program goals, the means of achieving those goals, and ensuring that the program is sustainably posi- tioned in order to pursue these goals. Furthermore, the strategies developed provide a base for managerial deci- sion making [3,32,31]. 1.2. Statement of the Problem As GHS continues with its decentralization process, resources are being disbursed directly to the district for the delivery of healthcare services. For example, finan- cial data at the Dangme West DHD showed that between 2005 and 2006 firs t quarter the NMCP/Global Fund sent twenty thousand, six hundred and thirty dollars, seventy six cents ($20,530.76c) to the DHD for malaria control activities. It is however, uncertain what structures the districts have developed to manage the health system in coping with the increasing malaria morbidity and mor- tality. Malaria is a public health problem which no doubt accounts for a substantial disease burden in the Dangme West and for many years various control measures have been undertaken with limited success. The percentage of reported cases of febrile illness presumed as malaria at the OPD has consistently risen over a period of five years (2002-2006) with annual OPD reported cases of 17,675 to 30,070. Current percentage rate of reported cases of febrile illness presumed malaria at the OPD was 51 percent [8], which was just the tip of ice-burg be- cause most people managed uncomplicated malaria at home. What management processes have the HCMs practiced all this while and how have they managed in- creased morbidity and mortality in malaria control? What are the outcomes of the efforts exerted by HCMs in malaria control? This study describes the extent to which SM process is being used to manage malaria control in the Dangme West district. There are numerous decisions and actions that managers and administrators take in the course of operating a development program. While all of them have an impact on the direction of the program and its outcome, certain interventions by the government and the program leadership is critical in that they prov ide the basic framework for operational decisions and set the pace for program performance. This means that for ef- fective and efficient malaria control, we should go be- yond the leadersh ip, reso urces and political commitment bit and use holistic approach or the SM approach in the management of malaria within the district as suggested by Paul [30]. Pertinent questions that need to be asked in this study are what management processes have the district devel- oped for malaria control and how has management thought their way out to cope with increasing morbidity and mortality of malaria? The reason for using the SM model was that this area has not been studied in depth although it is a promising area. 1.3. Objective To evaluate the extent to which the practice of SM is fully integrated into the management principles of GHS at the district levels and to make recommendations for improvement. 1.4. Significance for the Study SM when applied at th e district level will give a holis- tic approach to management such that malaria control programmes can wholly be linked to their environment with realistic objectives and packages that can always be verified. It will also ensure appreciable handling of the three major spheres of administrative responsibility of HCMs namely, day-to-day operations, management of the culture of the healthcare facility (HCF) and man- agement of strategy. All th ree must coexist and synergize each other for optimal performance or output. The district is the operational level of the GHS. It is the operational level where all decisions concerning the delivery of healthcare are implemented. The study will provide knowledge about issues and needs of district health system management and directions for SM in malaria control. It will let the membership of district health management team (DHMT) appreciate the im- portance of their environments especially, the concept of  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 345345 competition. Develop a common sense of purpose and shared values with the community thus, improving ef- fectiveness and efficiency of malaria control program within the district since malaria is a developmental issu e. It will encourage management training for all healthcare providers regardless of the size and site of the HCF. Furthermore, it will provide literature for further studies in this area. 1.5. Literature Review SM can be defined as a continuous, iterative process aimed at keeping an organization as a whole appropri- ately matched to its environment [5]. It is a process of making explicit the goals of the enterprise, the environ- ment in which it operates, the strategies, and finally the feedback loops that tell the firm whether each of these steps has been identified correctly [37]. One important element of SM process is the development of a vision for the organization by top management. SM is in large part, a decision-making activity. Strategy therefore, is the re- sult of a series of managerial decisions often supported by a great deal of quantitative data. Strategic decisions are fundamentally judgemental and generally the more important the decision, the less quantifiable it is and the more it is reliant on opinions of others [10]. Vision according to Hussey [20] is an expression of hope and is simply regarded as statement of basic prin- ciples that governs the direction in which a program seeks to develop. Critical to management is the choice of objectives which provides guidance and unified direction, facilitates planning, inspires motivation and commitment, and promotes control [17]. Multiple objectives are usu- ally pursued in a homogenous environment whereas sin- gle-service strategy is pursued in diverse environment where uncertainty in relation to market or public re- sponse is high [30]. Mintzberg [26] acknowledged that informal planning is an implicit strategy worked out by a dominant leader without the support of a formal process which is a highly ordered logical process developed purposefully for developmental programs. Formal plan- ning becomes increasingly important to programs when; their markets stop growing, there is increase in competi- tion and the rate of environmental change is dramatic [10]. Hussin [18] asserted that long-range planning and strategic thinking is common to most HCMs but not SM which is still vague to many managers. External envi- ronmental analysis is a process for understanding the external environment of organizations and acts as a window through which, HCMs can view external envi- ronment for information and/or issues [10] and develop packages to satisfy consumers. Internal involvement of staff in the exposition of the planning processes and inter-institutional communica- tion patterns between top and bottom layers of the HCFs according to Hussin et al. [18] are strategies used to re- duce resistance. Implementation is critical, in that if planning is creative and brillian t but strateg ies are poorly implemented, little is likely to change. Technical and financial support to districts for situation analysis ac- cording to Teklehai manot [38] is to ensure that interven- tions will be adapted to local needs which will be sus- tained after RBM support. Interventions required ade- quate resources but Duncan et al. [10] acknowledged that although financial resources are important reality checks to strategic decision making, the vision of man- agement should not be limited by the financial resources available. Duncan et al. [10] reiterated that there are dedicated personnel whose attraction to the field goes beyond monetary rewards and is mostly focused on some of the “strategic uniqueness” of healthcare. These strategic unique characteristics of the healthcare are in- spiration-related currencies, task-related currencies, po- sition-related currencies, relationship-related currencies, and personal-related currencies. As malaria morbidity and mortality continues to in- crease in most countries in Africa, international agencies and malaria control program managers have identified the strengthening of program evaluation as an important strategy for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of malaria control programs [4]. Evaluation helps man- agers to account for the investment made, refine strate- gies and identify and correct flaws in program imple- mentation. It provides decision-makers with the required tools for refined planning and modified strategies by updating on progress, as well as any problems or con- straints. 2. METHODS 2.1. Study Area The Dangme-West District is located in the south- eastern part of Ghana, in close proximity to Tema, the country’s largest seaport, and Accra, the capital city. It is the largest district (about 1,700 square kilometers) in the Greater Accra Region and its capital is Dodowa. The district is one of the two rural districts in the Greater Accra region which has not yet been caught up by the rapid urbanization of the peripheral areas surrounding the city of Accra. The Dangme West district according to Ghana Statistical Survey [13] is extremely poor and pre- dominantly rural with both poor socio-economic and infrastructural development [22] making financial access to health quite difficult. The district is sparsely popu- lated with most inhabitants living in scattered small communities less than 2,000 people, sometimes with very poor road access which gets worse in the rainy  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 346 district reports and documents for the past five years to enrich information for the study. season. The district was selected for the study because it is among the first 20 districts that implemented the RBM programme suppor ted by the Global Fund. 2.3. Stud y Population 2.2. Stud y Design The study population was all persons who provide healthcare services in the Dangme West district. All HCFs in the district; both public (n = 10) and private (n = 5) and all chemical shops (n = 25) in the district. All HCMs in the 15 HCFs took part in the study. Pur- posive sampling was used to select 17 chemical sellers out of 25 chemical shops from the communities se- lected for the study due to the vast nature of the district and money constraints. The list of chemical shops in the district was collected from the president of the chemical sellers association in his pharmacy shop at Dodowa. Those who couldn’t participate were shop assistant or attendants who could barely write and/or had little or no knowledge on current trends in malaria control practices. The study was a cross-sectional exploratory descrip- tive study of the processes for the management of ma- laria control activities in the Dangme West based on the conceptual model (Figure 1). The stud y used both quan- titative and qualitative methods of data collection in as- sessing strategic management practice. The researcher held semi-structured in-depth interviews with all the in- charges of HCFs and operators of chemical shops. These respondents were termed as HCMs for the study. Fur- thermore, discussions were held with the district phar- macist, the Global Fund representative of the district and the Public Relation Officer at the district assembly to gather information on managerial support to malaria control. Additionally, there was desk review of annual Status of key malaria control indicators Vision of NMCP, Mi ssi on/ Op era t io na l g oal s of NMCP, Objectives of NMCP External an alys is of the environment (Opportunities and threats) Inte rn al analys is of heal t h ca re facili t y (Strengt hs and weakness) Pla n ning pr oc e s s f or ma l a r ia co nt rol program wou ld gen er a te strategies a nd activities for the program (STRATEGY FORMULATION) Promotion of N MCP objectives Implementation of planned strategies and activities of malaria control (STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION) Monito ri ng and eva luation of s t rategies and activities of malaria control (STRATEGY CONTROL) Feedback Feedback Figure 1. The conceptual framework. Openly accessible at  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 347347 2.4. Data Analysis Analysis of data was both qualitative and quantitative using the SPSS 12.0.1 for Windo ws, (2003 ) and Epi-info ™ version 3.3.2 for windows, (2005). Qualitative data was analyzed manually by grouping, themes, sub-themes and trends after collating all data. After the question- naires have been checked for consistency, they were coded and entered primarily into Epi-info. The Epi-info data was later transferred into the Excel Spreadsheet then to SPSS software for analysis using a number of descriptive statistical techniques such as, cross tabula- tion, simple frequency tables, means, bar charts and pie chart to describe the various dimensions of the SM process. 2.5. Ethical Consideration At the district, consent was sought from all those who were involved in the study particularly from the DHA, chiefs and opinion leaders of the selected communities and the district assembly. Confidentiality an d anonymity was maintained throughout the study. 3. RESULTS Out of the 32 HCMs 16 (50.0%) were chemical sellers, whereas, 8 (31.3%) were nurses, 34.7% of the HCMs were beyond the age of 50 years. The conduct of the situational analysis involved both internal and external analysis of the HCFs and is the building blocks of stra- tegic planning for managing malaria control activities in the district. Information presented below informs the HCMs on the strengths and weaknesses of their HCFs and the opportunities and threats within their environ- ments. This is used to formulate strategies towards management of malaria control within the district. Out of 32 HCMs interviewed, all the 10 in the public HCFs representing 41.7 percent could state the vision of NMCP, again, all 5 (20.8%) in the private HCFs knew about the vision of NMCP. Whereas, out of the 17 chemical sellers interviewed, 9 (52.9%) knew the vision of NMCP. Vision of the HCFs was found displayed in only 2 facilities and it was a replica of the vision of the parent organization. Though an operational strategy hasn’t been developed by many of the HCMs, but because malaria is a house- hold or common disease, intuitively they effectively communicated their ideals through the following strate- gies. Out of the 32 HCMs, only 5 (15.6%) have devel- oped operational strategies for the control of malaria. None of the 17 chemical sellers have developed opera- tional strategies for malaria control because they were interested only in selling their drugs and not p articularly interested in any one disease condition. Operational strategies developed by the HCMs for management of malaria vividly expressed the intent of management to- wards healthcare delivery. The HCMs acknowledged their desire to give quality care to their clients, ensuring that all the tenets of NMCP were strengthened. The op- erational strategy of malaria control was given by Miss Cee HCM in a private-not-profit facility as: To provide quality care in the most effective and in- novative manner especially in the areas of curative, preventive and promotive health care to the community we serve at all times acknowledging the dignity of the patient; Similarly, Madam Aggie, HCM of public healthcare facility stated: To give quality care, education and effective manage- ment, and to ensure all cases are treated with Artesu- nate-Amodiaquine and encouraged children under five and pregnant women to sleep in ITNs. Communication of operational strategies has been outlined below and the media was sparingly used as compared to the other mediums of communication. The NMCP have designed a set of objectives to ensure uniformity in the organization, coordination and imple- mentation of the activities of malaria control within the districts. There was keen interest of HCMs in both pub- lic and private HCFs in meeting these objectives. The implementation of these objectives was ardently super- vised by the district health administration regularly. The Ta bl e 1 shows that the most common tools used in the planning process were community assessment (68.8%), objectives set by the NMCP (56.3%), SWOT analysis (40.6%), make reference to previous objectives with some analysis (50.0%), information technology, expert opinion and finally through scenario building. This indicated that management of malaria in the district was both community and NMCP related. Out of the 32 HCMs, 56.3 percent (18) used objec- tives set by the NMCP for their planning process; 9 (50.0 percent) from the public, 4 (22.2 percent) from the pri- vate and 5 (27.8 percent) from the chemical sellers. Ad- ditionally, out of the 32 HCMs, 40.6 percent (13) used the SWOT analysis; 7 (53.8 percent) from the public, 3 (23.1 percent) from the private with 3 (23.1 percent) being chemical sellers. Environmental factors were analyzed by HCMs to identify opportunities and threats within their environ- ment. Whereas HCMs in both public and private HCFs were really concerned about the socio-economic back- ground of healthcare consumers, ironically the chemical sellers were not bothered. The concept of competition was nonexistent for the HCMs, even the chemical sellers who were business entities. I would recount an amazing incident that chan ced during the interview of Miss Bee a HCM and her colleague at Osudoku sub-district:  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 348 Table 1. Management tools used in the situational analysis. Tools Percentage Public Private Chem. shop Information technology 32 (100%) 8 (25.0%) Scenario building 32 (100%) 3 (10.7%) Expert opinion (Consultants) 10 (31.3%) Make reference to previous objectives with some analysis 16 (50.0%) 8 (50.0%) 2 (12.5%) 6 (37.5%) Make use of objectives of NMCP 32 (100%) 18 (56.3%) 9 (50.0%) 4 (22.2%) 5 (27.8%) SWOT analysis 32 (100%) 13 (40.6%) 7 (53.8%) 3 (23.1%) 3 (23.1%) Community assessment 32 (100%) 22 (68.8%) 10 (45.5%) 4 (18.2%) 8 (36.4%) Source: Healthcare facility survey Having just answered in the negative about competi- tion, a drug peddler carrying his wares passed by. The peddler took some time in exchanging pleasantries with the healthcare manager before continuing on his mission. Then I asked her: You claimed there are no competitors here, what about the peddler who just passed by? Is he not offering some form of healthcare? Don’t you have chemical sellers around? Are they not treating malaria? All these questions were answered in the affirmative. She then admitted that both the activities of chemical sellers and drug peddlers posed a great challenge for malaria contro l within the community. Generally, the HCMs utilized most of the environ- mental factors especially the political, social, regulatory and epidemiological factors in coming up with plans for malaria control. Opportunities identified by HCMs within their environment that enhanced malaria control were generally community participation, interpersonal relationship between staff and clients, extensive use of ITNs, research on rectal Artesunate for children under five and involvement of CBAs in home-base care. Teyi, a HCM of a private HCF in the Prampram sub-district recalled opportunities as: Good interpersonal relationship between staff and clients urged them to openly discuss their problems, there were also organized groups such as churches, youth clubs, schools, etc., which makes BCC a whole lot easier. Finally the involvement of community based agents in home-base care greatly influenced incidence of malaria in the under fives. Miss Adotey a HCM of a public HCF on her part claimed: Community members’ are always in haste to identify- ing health problems for healthcare providers to solve and their eagerness to learn innovative ideas concerning malaria control. There is again, overwhelming collabo- ration between the healthcare facility and the communi- ties, extensive use of ITNs, communal spirit of most communities, and research on rectal Artesunate for chil- dren under five years by the HRU; and administration of rectal Artesunate suppositories to under five-year olds by the CBAs. Whereas Mr.Kweinor a chemical seller at Ayikuma remarked: Education of the community on home-base care by the DHD, education of market women and the HE-HA-HO programme by the NMCP on radio have increased the knowledge-base of the people on malaria. Environmen- tal cleanliness is also encouraging. Threats basically were challenges that impinged on the success of intended objectives. Generally threats identified by the HCMs ranged between environmental sanitation to unemployment, poverty and illiteracy. Threats as retorted by Dr. Kwei a HCM in Prampram sub-district were abound and he remarked: Since this community is still growing, new buildings are springing up with open trenches all over the place which collect water when it rains thus, creating a con- venient environment for the breeding of mosquitoes. Again, there are no toilet facilities in the communities, so individuals dig holes which become breeding places for mosquitoes. Miss. Ayi also in the Prampram sub-district described threats identified as: The activities of chemical shops and drug peddlers, unemployment, poverty, increase in the premium of the National health insurance scheme; high illiteracy rate, lack of transportation and portable water in some com- munities. Similarly, Miss Lee at Osudoku sub-district re marked: The rice farms in the community breed a lot of mos- quitoes. The choice of medicine to use for malaria is crucial since there are several options at the chemical shops that are relatively cheaper than the recommended drug for malaria by the government. Mr. Tetteh a chemical seller in the Ayikuma sub-dis- trict declared: Unemployment with its associate effects of poverty has been a major hindrance in the purchasing of rec- ommended drug Artesunate-Amodiaquine which, they  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 349349 considered expensive. There are a lso pit latrines all over the communities and these are potential places for breeding of mosquit oes. At Old Ningo Mr. Agyeman a chemical seller had this to say: There are no gutters in the community thus; there are pools of standing water all over the community with reckless disposal of refuse also compounding the already compromised situation. Most people are illiterates and there is no communal spirit. Mr. Akoto also a chemical seller acknowledged that: The choice of medicine to be used is a major threat to the control of malaria. Clients always come with their demands and preferences, which usually depend on af- fordab ility. They reckon ed that the recommended drug is too expensive for the ordinary man hence, their reliance on other equally efficacious alternatives such as the herbal preparations. Methods used for assessing strengths and weakness within the HCFs and conducting community assessment are outlined in Table 2. Facility strengths identified by HCMs generally were availability of recommended drugs for the management of malaria, relatively moderate fees charged for service delivery, promotion of the tenets of NMCP and knowl- edgeable staff. This was expressively put by Dr. Nartey a HCM in Prampram as: We are always ready to receive clients and there is good relationship between clients and us. We charge relatively low fees and clients spend less time at the clinic. Again, we have in stock most of the drugs for malaria. Similarly Miss Agartha, a HCM in Ayikuma remark- ed: We have adequate logistics; provision of free ITNs, provision of free folic acid, and Artesunate Amodiaquine for one year. Additionally, we have stocks of antima laria drugs e.g. Quinnee, Artesunate and Amodiaquine. Mr. Dakey a chemical seller in Asutuare said: The experience gained from persistent training en- sured delivery of quality service to clients and I have in stock adequate drugs for the management of malaria. Miss Adotey a HCM in Dodowa declared: Our staff ensures that clients receive quality care thus; there is good staff-client relationship. We have available all malaria drugs and laboratory facility for confirma- tion of the diag nosis of malaria. Facility weaknesses identified by HCMs were inade- quate quality and quantity of staff; inadequate logistics; no definite plan for the program; inadequate finance; inadequate motivation of staff; insensitive attitude of some staff; infrequent in-service training for staff; and lack of privacy. Attitude toward risk was non existence, and all 32 HCMs declared they did not encounter any risk in either planning or implementation. Almost all staff especially those in the public HCFs were involved in the planning process whereas in the private and chemical shops only the HCMs did the planning. Out of the 32 HCMs, 3 (9.4 percent) did have formal plans, 18 (56.3 percent) had informal plans whereas 11 (34.4 percent) had both formal and informal plans. Even the 3 HCMs with formal plans could not readily produce their plans. Table 2. Methods used for internal auditing. Type of healthcare facility Method Public Private Chemical shop Total (n = 32) Utility rate 6 (46.2%) 5 (38.5%) 2 (15.4%) 13 (40.6%) Government assessment 8 (42.1%) 5 (26.7%) 6 (31.6%) 19 (59.4%) Measuring the market share 5 (38.5%) 3 (23.1%) 5 (38.5%) 13 (40.6%) Studying the gap 9 (50.0%) 4 (22.2%) 5 (29.4%) 18 (56.3%) Benchmarking other facilities 4 (40.0%) 2 (20.0%) 4 (40.0%) 10 (31.3%) Perception testing of key constituency groups 8 (53.3%) 3 (20.0%) 4 (26.7%) 15 (46.9%) Community assessment Activity parameters of the facility 5 (50.0%) 4 (40.0%) 1 ( 1 0 % ) 10 (31.3%) Simple on-going conversation 7 (33.3%) 5 (23.8%) 9 (42.9%) 21 (65.6%) Informal gathering of local leaders 6 (40.0%) 4 (26.7%) 5 (33.3%) 15 (46.9%) Structured questionnaire 4 (36.4%) 2 (18.2%) 5 (45.5%) 11 (34.4%) Focus group discussion 6 (46.2%) 3 (23.1%) 4 (30.8%) 13 (40.6%) Healthcare facility’s discharge data 9 (56.3%) 4 (25.0%) 3 (18.8%) 16 (50.0%) Traditional database and health statistics indicators 4 (44.4%) 2 (22.2%) 3 (33.3%) 9 (28.1%) Source: Healthcare facility survey  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 350 Out of the 32 HCMs, 17 (53.1 percent) developed plans for malaria every year. 6 (15.6 percent) asserted the duration of their plans were two years while 2 (6.3 percent) had five-year plan for their HCFs. The remain- ing 8 (25.0 percent) HCMs declared they neither had plans nor duration for their plans. The mean duration period was 1.5years. Out of the 32 HCMs, 2 (6.3 percent) had annual planning meetings. 1 (3.1 percent) had semi- annual meetin gs, 9 (28.1 percent) had quarterly meetings while 10 (31.3 percent) had monthly meetings. For 10 (31.3 percent) of the HCMs however, planning meetings were contingent and usually ensued as situation de- mands. The first barrier towards implementation in any de- velopmental program has been resistance to change. Out of the 32 HCMs interviewed, 4 (12.5 percent) admitted to facing much resistance to change, 9 (28.1 percent) claimed they faced little resistance, while 15 (59.4 per- cent) asserted to facing no resistance during implemen- tation. HCMs remarked that factors relevant to implementa- tion of malaria control were leadership, training, ade- quate resources, and organizational culture. See Ta bl e 3 for detailed description. The factor that ostensibly im- pacted on implementation of malaria control was lead- ership; the use of non coercive influence to shape the HCF’s goals, motivate behaviour towards the achieve- ment of goals and help define organizational culture. Out of the 32 HCMs, 23 (71.9 percent) had their staff trained and delegated the authority needed to produce the quality of healthcare services demanded. All the 10 (43.5 percent) public HCMs had their staff trained, 4 (17.4 percent) of the private HCFs also had their staff trained whereas, 9 (39.1 percent) of the chemical shops had their staff trained too. 9 (29.0 percent) HCMs had adequate number of qualified clinical staff on duty at all times to ensure that clients receive prompt and high quality healthcare services. Frequency of In-service train- ing offered to staff to upgrade knowledge, skills and at- titude ranged between quarterly 9 (28.1%), annually 8 (25.0%), twice a year 7 (21.9%), weekly 2 (6.3%), thrice a year 1 (3.1%), twice in three years 1 (3.1%) to none 4 (12.5%). Most of the chemical sellers either had annual training 8 (47.1%) or had training twice a year 5 (29.4%). Out of 32 HCMs, 15 (46.9 percent) had flexible cul- tures, 4 (12.5 percent) had very flexible cultures, while the 3 (9.4 percent) had a rigid, and 1 (3.1 percent) had very rigid cultures. 9 (28.1 percent) had somehow neu- tral culture for malaria control. Leadership style pro- moted in the HCFs according to the 32 HCMs were management team leadership style 18 (56.3 percent), and the combined style of leadership 12 (37.5 percent). An- other fact was that all HCMs who pursued a combined style of leadership also had flexible cultures. The chi- square was 13.338 with a p-value of 0.345. F-statistics was 3.937 with a p-value of 0.047, and a correlation co- efficient of –0.207. Implementation of malaria control within the facilities was done through the assignment of responsibilities for each aspect of the plan 13 (40.6 percent), trust and open communication 12 (37.5 percent), establishment of rela- tionship among people 11 (34.4 percent) and finally delegation of authority 6 (18.8 percent). Management of malaria control was carried out in such a way that it pro- vided staff with a sense of security, au tonomy and at the same time motivation (91.7 percent). This was done by giving incentives, open recommendation of staff, re- warding extra work, and verbal encouragement of staff. Arguably almost all the HCFs had in place similar moti- vational strategies. One important factor was the zeal of healthcare providers to see that everything was in order, thus, even when there were no incentives, work was ac- complished without any hindrance. The regular work- shops on malaria organized to upgrade knowledge, skills and attitude equally enhanced competence, commitment and confidence. Furthermore, appraisals and good inter- personal relationship between management and staff ensured contentment among colleagues. Table 3. Factors that impact on implementation of malaria control. Factor Most imp. Imp. Least imp. Total Leadership 19 (59.4%) 7 (21.9%) 6 (18.8%) 100 Training 19 (59.4%) 7 (21.9%) 6 (18.8%) 100 Motivation 10 (31.3%) 10 (31.3%) 12 (37.5%) 100 Adequate resources 15 (46.9%) 5 (15.6%) 12 (37.5%) 100 Need to build Information sys tem 16 (50.0%) 6 (18.8%) 10 (31.3%) 100 Organizational culture 10 (31.3%) 7 (21.9%) 15 (46.9%) 100 Organizational structure 11 (34.4%) 8 (25.0%) 13 (40.6%) 100 Source: Community Survey  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 351351 Out of the 32 HCMs, 18 (56.3 percent) had their staff trained on the strategies of NMCP, basic S&S and man- agement; 9 (50.0 percent) from the public HCFs, 5 (27.8 percent) from private with 4 (22.2 percent) being chemical sellers. 17 (53.1 percent) out of the 32 HCMs did also involve opinion leaders, district assembly and religious institutio ns in their BCC; 8 (47.1 percent) from the public HCFs, all the 5 (29.9 percent) private HCFs and 4 (23.5 percent) from chemical shops. Out of the 32 HCMs, 14 (43.8percent) had standard case definition of malaria developed and pasted at van- tage points within their HCFs; 8 (57.1 percent) from the public, 4 (28.6 percent) from the private and 2 (14.3 percent) chemical sellers. 18 (56.3 percent) HCMs out of the 32 persistently carried out BCC on malaria preven- tion within the communities; 9 (50.0 percent) from the public HCFs, 3 (16.7 percent) from the private HCFs whil e 6 (33.3 percent) were chemical sellers. Out of the 32 HCMs, 14 (43.8 percent) would request for laboratory test for confirmation of diagnosis; 7 (50.0 percent) were pu bl i c HCFs , 5 (35. 7 p ercent) were private HCFs while 2 (14.3 percent) were chemical shops. Other measure identified was the requisition for blood film for malaria parasites (BF) for pregnant women before SP was given when clients develop malaria by 1 public healthcare manager. 14 HCMs representing ( 43 .8 percent) out of the 32, acknowledged the involvement of school children in their BCC; 7 (50.0 percent) from the public HCFs, 3 (21.4 percent) from the private HCFs while 4 (28.6 percent) were chemical shops. 12 (37.5 percent) HCMs out of the 32, developed and distributed simpli- fied case definition of malaria leaflets to households; 7 (58.3 percent) from the public, 1 (8.3 percent) from the private HCF whereas 4 (33.3 percent) were chemical shops. Systems developed to ensure appropriate response and referral has been enumerated in Ta bl e 4. Prompt atten- tion to emergency cases and provision of approved treatment was important to the groups. In almost all the HCFs visited, protocols for case management of malaria were visibly displayed on the walls. Some HCFs had drugs such as Artesunate suppositories, Folic acid and iron tablets free for children under five-years and preg- nant women. See Table 5 for detailed description. Table 4. Systems developed for appropriate response and referral. Type of healthcare facility System Public (n = 10) Private (n = 5) Chem. shop (n = 17) Total (n = 32) Protocol for malaria case management in al l c l i n ical areas 9 (60.0%) 4 (26.7%) 2 (13.3%) 15 (46.9%) Provision of approved malaria treatment in the facility 9 (50.0%) 4 (22.2%) 5 (27.8%) 1 8 (56 3%) Prompt attention to emergency cases 9 (42.9%) 5 (23.8%) 7 (33.3%) 21 (65.6%) Effective system of referral 9 (56.3%) 5 (31.3%) 2 (12.5%) 16 (50.0%) Source: Survey of Healthcare Facilities Table 5. Measures for delivering quality healthcare services. Type of healthcare facility Measures Public (n = 10) Private (n = 5) Chem. shop (n = 17) Total (n = 32) Effective use of performance appraisal to identify Staff needs for subsequent training 4 (50.0%) 2 (25.0%) 2 (25.0%) 8 (25.0%) Patients are given prompt attention 9 (37.5%) 5 (20.8%) 10 (41.7%) 24 (75.0%) Patients are always given all their treatment at the facility 10 (52.6%) 5 (26.3%) 4 (21.1%) 19 (59.4%) Improved staf f at ti tu de t o cl ie nt s 8 (44.4%) 4 (22.2%) 6 (33.3%) 18 (56.3%) Horizontal integration with some agencies within the community to ensure easy access to resources 1 (20.0%) 3 (50.0%) 1 (20.0%) 5 (15.6%) Provision of incentives 1 (16.7%) 4 (66.7%) 1 (16.7%) 6 (18.8%) Open recommendation of hard working staff 7 (46.7%) 5 (33.3%) 3 (20.0%) 15 (46.9%) Source: Facility Survey  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 352 HCMs asserted that clients’ concerns were acknowl- edged through friendly attitude of staff towards clients which coaxed them to air their grievances to them when- ever possible; they also questioned clients about effec- tive use of drugs or provision of other services. Addi- tionally, complaints were sometimes lodged with opin- ion leaders or the assemblymen, following-up of cases, and open discussions during staff or advisory board meetings. Apart from Dodowa HCF that had a sugges- tion box, the remaining HCFs basically resorted to in- formal measures in soliciting for clients’ concerns. Qualitative data suggested that home-based manage- ment of malaria was essentially carried out by education, counseling and home visits to ensure that mothers did the right thing however; others have not been doing anything. Wh ereas, the HCMs in both the pubic and pr i- vate resorted to BCC on care of children at home to care takers, the chemical seller largely engaged in talking to clients on how to take medicine. Namely, mothers were trained to tepid sponged their children when there is fe- ver and to give Paracetamol before sending them to the CBAs for rectal Artesunate, they were also encouraged to use ITNs especially for children under five years and to give ORS when there was diarr h oea a nd vomiting. Qualitative data suggested that although, HCMs were not aware of what they have been doing, maintaining competitive edge was essential to all the HCFs. They ensured prompt attention to clients to avoid client frus- tration and maintained cordial staff-clients’ relationship to enhance maximum satisfaction. Occasionally, mass educational campaigns were carried out, canvassing community members to use their HCFs. Offering of 24-hour quality service to clients and ensuring that cli- ents receive all treatments at the facility. Fees charged were relatively moderate and clients have been encour- aged to join the NHIS to be able to always patronize their services. Qualitative data indicated that special efforts adopted in both public and private HCFs to enhance NMCP strategies were Behavio ur Chan ge Commu nic ation (BCC) which was carried out both massively and individually. These educational campaigns emphasized multiple pre- vention strategies such as the use of ITNs, IPT and en- vironmental cleanliness. HCFs also had in stock recom- mended drugs. Staff especially, those in the public HCFs have all been trained in current trends and training was carried out periodically to update skills, knowledge and attitude of staff. Distribution of ITNs to children less than two years was on-going in all the public HCFs, to- gether with the administration of SP. The chemical sell- ers on the other hand, have embarked upon education and counseling of customers. Multiple strategies adopted to reduce the occurrence of malaria within the district by HCMs were basically promotion of insecticide treated materials, liaising with the district assembly for educational campaigns, en- couraging communities on good environmental sanita- tion and administration of chemotherapy to pregnant women. 24 (75.0 percent) HCMs out of the 32 encouraged the use of insecticide treated materials in combating malaria; apart from 9 (37.5 percent) chemical sellers, the 15 (68.5 percent) were all HCMs from both public and private HCFs. Out of the 32 HCMs, 13 (40.6 percent) liaised with the district assembly for health educational cam- paigns; 7 (53.8 percent) from the public, 3 (23.1 percent) from the private and 3 (23.1 percent) being chemical sellers. 22 (68.8 percent) out of the 32 HCMs, did en- courage drainage, mosquito proofing and general sanita- tion through education campaigns in the fight against malaria; 9 representing 40.9 percent were public HCMs, 4 representing 18.2 percent were from the private and 9 (40.9 percent ) be i n g c hemical sellers. Administration of chemotherapy to pregnant women was carried out by 14 (43.8 percent) out of the 32 HCMs; 9 (64.3 percent) from the public, 3 (21.4 percent) from the private, with 2 (14.3 percent) being chemical sellers. Additionally, residual spraying was carried out by 6 (18.8 percent) HCMs out of the 32, while larviciding was done by 5 ( 15.6 perc ent) HCMs. HCFs are primarily community assets thus, the com- munity 32 (100 percent) partner whatever the HCMs embarked upon to ensure their effectiveness. Equally important in this partnership was the religious institu- tions 20 (62.5 percent), educational institutions 13 (40.6 percent) and the district assembly 10 (31.3 percent). Partnering the religious institutions were 7 (35.0 percent) from the public, 5 (25.0 percent) from the private and 8 (40.0 percent) chemical sellers. Partnering educational institutions were 7 (53.8 percent) from the public, 3 (23.1 percent) from the private and 3 (23.1 percent) chemical sellers. Partnering the district assembly were 6 from the public, 3 from the private and 1 chemical seller. The activities of NGOs 5 (15.6 percent) were not wide spread within the district, apart from the World Vision International who was assisting in staff training; the Catholic Church was also assisting with the financial management of one HCF. Hence, community participa- tion in malaria control was exceedingly important to the HCMs and every effort was being used to sustain it. The health system in the district has been using the integrated approach to public health diseases in the management of malaria. Thus, there has not been any structural change within the HCFs for the sole manage- ment of malaria. Qualitative data suggested there have been the creation of community based agents (CBAs) in  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 353353 the communities. These volunteers have been identified and trained to administer rectal artesunate supposito ry at the community level. They have been giving artesunate suppositories to be used as first aid in the management of malaria in the under fives. Caretakers were instructed to rush their infants to the CBAs for insertion of the suppository before taking them to HCF for treatment continuation. However, because the rectal artesunate was free, many caretakers preferred going to just the CBAs for the free rectal suppository without going to HCFs for further management due to cost. The CBAs have also been trained in the principles of IPT; they roamed the community to ensure that all pregnant women attended ANC. The defaulters were then referred to the HCFs for antenatal care and SP. The midwives would then issue these women chits to be given to the CBAs so as to ensure constant communica- tion between the CBA and the client. The reporting system used sporadically to co nduct the control process indicated that out of the 32 HCMs, 50.0 percent (16) followed a quarterly control approach whereas 6.3 percent (2) had an annual approach. The remaining 9.4 percent (3) of the HCMs conducted it monthly while 12.5 percent (4) did interfere immediately when the need arose. 7 (21.9%) did not have any control mechanism in place. Ta ble 6 depicts the control process for malaria activities. The process which is common to all the groups was studying, analyzing and evaluating the outcomes and taking corrective measures where necessary (62.5 percent). Informal processes such as feedback through conver- sation, frequent team meetings, direct contact and inter- views were used in all the HCFs. There was no doubt that the HCMs’ ability to orchestrate planning and im- plementation in the light of changing conditions was greatly strengthened by the operation of this sensitive process. Use of feedback in supervision was mainly verbal and immediate or during staff meetings. Partners involved in the management of malaria within the district were the Health research unit, NGOs such as World vision international and the Catholic Church, the district assembly, educational and religious institutions, opinion leaders and the community as a whole. These agencies carried out periodic researches, pilot surveys; provided assistance for BCC, distribution of ITNs, training and organized communal labours. Most of these partners were members of the DHMT; they communicated constantly to plans and constituted a core group within the d istrict helping to reduce morbidity and mortality attributable to malaria. Partnership according to HCMs was maintained by constant communication. The DHMT for instance would confront them with their problems after receiving quarterly reports. Challenges were addressed by these partners through dialogue and feedback on how resources have been utilized. 4. DISCUSSION Conduction of situational analysis was prevalent though, the researcher couldn’t really fathom usage of information generated from the analysis. There was no formal documentation of any conduct of situational analysis; as formal plans were infrequently used in the management of HCFs. Data presented therefore, were simply perceived conduct of situational analysis by the HCMs. The vision of NMCP was widely known in both private and public HCFs. The high knowledge of the strategic vision could be due to the increased in-service training and promotion of malaria control within the district by the health directorate. Dangme West typically being an indigenous district, her environment was natu- rally uncompetitive [10], all the HCM were pursuing multiple goal and multiple service strategies as ac- knowledged by Paul [30] for better outputs of malaria control. As suggested by Hussey [20] and Senge [34] knowledge of the vision, mission and objectives is criti- cal because it would guide the direction of the program and create energy for changing reality which ensure higher performance and disciplined program. It is very sad though, that none of the HCFs could boast of a computer, which is very basic to effective planning. The development of timely, accurate, system- atic, consistent and useful information system is crucial for analysis of dynamic forces of the environment for efficient planning as noted by Sprague and McNurlin [35]. Therefore, to have a structured plan the DHD should endeavour to equip the HCFs with computers to facilitate planning. SWOT analysis according to Duncan et al. [10] is an essential logical element that combines analysis with judgment in planning. HCMs constantly carried out SWOT analysis to enhance collaboration with the com- munities as indicated by both Bopp [1] and Ofosu- Amaah [29]. Community participation in malaria control was important to global RBM [8] and frantic efforts were being made by the HC M s to enhance this objective. Opportunities identified were overwhelming collabora- tion between HCFs and the communities, extensive use of ITNs, increased communal spirit in some communi- ties and research on rectal Artesunate for children under five years by the health research unit (HRU). The activi- ties of the HRU kept malaria control active in the district which confirms the assertion of Paul [30] that integration of pilot projects enhances program effectiveness and keeps it reengineered. Threats identified included unemployment, high illit- eracy, poverty, and poor environmental conditions which  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 354 challenged the control process. The district is predomi- nantly rural with poor socio-economic and infra-struc- tural development; hence, in some communities the NHIS was initiated and sponsored by International La- bour Organization, this encouraged many residents to utilize the HCFs. After the project residents simply stopped using the HCFs due to finance. This is of im- mense concern to the management of malaria. A peculiar situation captured during the study, was a virtually empty HCF during working hours. Explanation given was that residents were looking for money to pay-up their prem i ums. Conventional methods were used in assessing strengths and weaknesses. Common among them were govern- ment assessment, perception testing of key constituency groups and studying the gap, which were mostly used by the public HCFs because of centralization of administra- tion within th e district h ealth system. Benchmark ing was a novelty and w as sparing ly used b y the HCMs pr obably because of its uncertainties in practice as stated by Macmillan and Tampoe [24] or its comparative nature as planning was basically informal. Community assessment was fairly utilized by all the HCMs; simple on-going conversation and informal gathering of local leaders were most favoured method. Common strengthens among the HCFs were av ailabil- ity of recommended anti-malarias, charging of moderate fees and promotion of the tenets of NMCP. Attitude of healthcare providers were particularly good because of the indigenous nature of the district. HCMs readily ac- cepted that due to the rural nature of the district, most professionals refused postings to the area hence, inade- quate quality and quantity of healthcare providers was a major weakness to almost all the HCFs (GHS). Inade- quate resources, no definite plans for the program, in- adequate motiv ation of staff, insensitive attitude of some staff, infrequent in-service training for staff, and lack of privacy were some weaknesses identified with the HCFs. Analysis of all the above data set the pace for effective planning though there w ere no formal plans in almost all the HCFs just as Botchie [2] confirmed this to be very common in public services in Gh ana. Planning for malaria control activities in the district was much more informal than formal. HCMs were more interested in the day-to-day management of their facili- ties due to the homogenous nature of district. Planning in such an environment according to Duncan et al. [10] can be mostly informal especially with smaller entities such as the HCFs found in the district. Though almost all the healthcare managers used either informal or combined planning process relevant to the situation, there was con- sistency in decision making, and management of malaria control within the HCFs was relatively effective. Duncan et al. [10] reiterated that when there is an increase either in the level of competition or changes in environmental factors, the need for a formal planning process appreci- ates. The attitude of the HCMs therefore, was due to doing business in an uncompetitive and relatively stable environment. As discovered by Hussin et al. [18] the general prac- tice of HCFs was more towards short-term than long term, and the duration ranged between one to five years with an average of 1.5 years. Generally, it can be con- cluded that strategic orientation did not exist in the dis- trict and so was strategic thinking since plans were mostly informal or combined with short-term duration. This was not unforeseen ; the districts are the operational level and normally are implementers of plans orches- trated either by the regional or national levels of GHS. Frequency of planning meetings ranged between quar- terly and monthly meetings though, many preferred con- tingency planning meetings to bridge up gap on trends of malaria control with colleagues. Ensuring access to basic quality healthcare services was a key strategic objective of the health sector [27] and since various studies [7,15] have observed relation- ship between user-perception of quality of care and healthcare seeking behaviour for malaria and other ill- nesses, clients were assured of prompt attention for all treatment being given at the facility and more impor- tantly improved attitude of healthcare providers. As Wyss rightly put it a well-functioning health system de- pended on motivated workforce, much more was being done both at the district and national level to help moti- vate healthcare providers to give off their best. The use of performance appraisal has always been a thorny issue in the GHS and there have been several attempts in re- viewing its use. Only a quarter of the healthcare provid- ers admitted to using the tool although, it is very effi- cient and effective in identifying weaknesses in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes for further training. It is an open secret that this important management tool is used just for promotional purposes and its contents were never analyzed for developmental gains. Monitoring of client’s concern is an essential way of assessing clients’ perception on quality healthcare delivery and improving performance based on user perspective which would ultimately guide healthcare providers in satisfying cli- ents’ needs. Although the DHD has recommended the use of suggestion boxes to formalize concerns, like the proverbial African, concerns were still generated through informal means. This again is of great concern since clients could be victimized and/or ignored through this process. HCMs need to be encouraged to have sugges- tion boxes installed in all HCFs so as to generate i mpar- tial perceptions of their output or impact from the gen- eral public which would ultimately improve performance  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 355355 and attitude of staff. In maintaining competitive edge HCMs naively u s ed a combination of approaches suggested by Macmillan and Tampoe [24]. Time based approach was significantly used to avoid client frustration and maximize satisfac- tion; this appro ach couldn’t be well executed at the pub- lic facilities where work load was almost always high. Healthcare delivery being a professional service was undoubtedly a knowledge-intensive enterprise thus; de- velopment of knowledge have been a strategy in sus- taining commitment, competencies, and confidence of the workforce to g uarantee delivery of qu ality healthcare to clients in the district as confirmed in all these studies [14,21,25,33]. Hence, in carrying out most of their man- date, knowledge and technology generated from research [28] were used in curbing the ascendancy of severe ma- laria. With the upsurge of morbidity and mortality, streng- thening of programme evaluatio n was essential to en sure effectiveness and efficiency of malaria control [4]. HCMs in evaluating malaria control activities mostly studied, analyzed and evaluated outcomes; taking imme- diate steps to make amends where necessary. They again organized frequent staff durbars to discuss achievements and the way forward. Thus, HCMs used both outcome- based and impact-based approach in their evaluation and extensively involved their colleagues which encouraged commitment to the ideals of malaria control. An effective feedback system provides the workforce with the opportunity to reflect on their past performance and improve upon it, thereby enhancing performance. Feedback again promotes commitment among staff, strengthening competence and confidence. The study acknowledged that HCMs used more informal ap- proaches such as conversation than the formal appro- aches. This was seen more with the HCFs, where con- versation appeared to be the favourite of the healthcare managers. Chemical sellers appeared not to be bothered about this approach and never really patronized it. It is however; important to note that giving constructive feedback is very essential in management as stated by Mary Parker Follet that management is “working through people to achieve organizational goals”. Feed- back always have the magic of ensuring that individuals’ creative ability is accessed jointly as a team to boost competitive edge, achieving organizational goals and ensuring that workforce becomes committed, competent and confidence. Partnership in malaria control was very important and was maintained by effective communica- tion. Partners involved in the control process were the DHD, HRU, NGOs and the wider society. These partners had roles in planning, sometimes implementation and even evaluation; they assisted wherever necessary to ensure that malaria control remained effective and effi- cient. 5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY The approach used for data collection was both quan- titative and qualitative b ut generally due to the technical nature of management and the educational background of most of the respondents especially the HCMs, most questions had to be explained vividly before they could complete the data collection tools. This may perhaps have affected some of the responses that were generated. 6. CONCLUSIONS The study generally identified many elements of the practice of SM in the district. However, these elements were not being managed holistically thu s, construing the main tenets of the systems’ theory, on which the SM theory was developed; that is the whole is greater than the sum of its part. Thus, though the status of key ma- laria control indicators was remarkable, this would have been further enhanced if SM had been holistically prac- ticed in the district. 7. RECOMMENDATIONS The diverse findings identified presents implications for public health practice, education, research, and pol- icy formulation. The In-Service Training of GHS should endeavour to develop SM as a taught course for senior managers using the experiential teaching method to give it a practical approach. HCMs who have had the advan- tage of being at GIMPA and exposed to the SM course should be encouraged to make use of knowledge ac- quired through training to enrich malaria control and other health issues of public health con cern. BCC should be encouraged within the district and more effort is still needed to extend community participation. This will enhance acknowledgment of health programmes and usage of basic tools developed to improve health. DHD should persuade HCMs to have continuous BCC, taking advantage of local nuances so as to increase knowledge and acceptance of new health trends and issues. The in- volvement of CBAs in healthcare delivery is very com- mendable and this should be encouraged to ensure that all pregnant women attend ANC and caretakers improve their skills on home-based care of malaria. The DHD should organize workshops and seminars on the principles of business management especially, customer care and work ethics. HCMs should be en- couraged to have formal plans for their HCFs. Finally, HCMs should focus on persistent upgrading of knowl- edge, skills and attitudes of their staff to ensure sustain- able delivery of quality healthcare. The DHD should  A. M. A. Ofei et al. / Health 3 (2011) 343-356 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 356 align themselves with the chemical shops to supervise their activities, to ensure that they at least record malaria or febrile cases handled and also to ensure that they fol- low regulations promulgated by the Pharmacy Council. This would at least help in the assessment of actual in- cidence and prevalence of malaria because lots of chemi- cal sellers are selling and dispensing drugs wrongly to unsuspected healthcare consumers. There should be a firm grip on the chemical sellers within the district since the Pharmacy Council is too remote and their infrequ ent visits are not helping much. Openly accessible at REFERENCES [1] Bopp, M. (1994). The illusive essential: Evaluating par- ticipation in non-formal education and community de- velopment. Con vergence. Vol. XXVII. 1. [2] Botchie, G. (1986). Planning and implementation of de- velopment plans in Ghana: An appraisal. Rural develop- ment in Ghana. Ghana University Press, Accra. [3] Browne, M. (1994). The evolution of strategic manage- ment thought: Background Paper-Strategic Management Educators' Conference, Australian Centre in Strategic Management QUT [4] Bryce, J., Roungou, J.B., Nguyen-Dinh, P., Naimoli, J.F., & Breman, J.G. (1994) Evaluation of national malaria control programs in Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 72, 371-381. [5] Certo, S.C., Peter, P.J. (1988). Strategic Management: Concepts and Applications. New York: Random House Business Division, (1st. Edition). [6] Davies, W. (2000). Understanding strategy. Strategy and Leadership, 28, 25-30. [7] de Savigny, D., Mayombana, C., Mwageni, E., Masanja, H., Minhaj, A., Mkilind, Y., Mbuya, C., Kasale, H., Reid, G. (2004). Care-seeking patterns for fatal malaria in tan- zania. Malaria Journal, 3, 27. [8] District Health Directorate/GHS (2002-2006). Annual Reports. DHD/GHS, Dangme West. [9] Drucker, Peter F. (1999). Change Leaders. http//www.inc.com/magazine/199990601/804.html [10] Duncan, W.J., Ginter, P.M., Swayne, L.E. (1996). Strate- gic Management of Healthcare Organizations. 2nd Edition. Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Cambridge, Massachusetts. [11] Gates Malaria Partnership. (2006). GMP Report 2001- 2006. Greenford Printing Co. Ltd., Pinstone Way, Bucks. [12] Ghana Health Service (2001). Roll Back Malaria Base- line Survey. GHS, Accra. [13] Ghana Statistical Service (2000). Ghana Living Stan- dards Survey Report of the Fourth Round (GLSS4); Ghana Statistical Service, Accra. [14] GHS/HRDD, Ghana (2006). A manual on In-service Training policy and Guidelines for Implementation. NHLMC, Kumasi. [15] Goodman, C., Coleman, P., Mills, A. (2003). Economic Analysis of Malaria Control in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Global Forum for Health Research. WHO, Geneva. [16] Greenwald, Bruce; Kahn, Judd (2005). All Strategy is Local. Harvard Business Review. September, 94. [17] Griffins, Ricky W. (1999). Management. 6th Ed. Hough- ton Mifflin Company. Boston, New York. [18] Hussin, J, Hejase; Dima, A. Baltagi; Kassem, Kassak. (2000). Assessment of Strategic Management Practice in Private Non Profit Hospitals in Greater Beirut. Health- care Management Present and Future Challenges. April 11-13, Beirut-Lebanon Presented Papers. [19] Ijumba, Jasper; Kitua, Andrew Y. (2004). Enhancing the Application of Effective Malaria Interventions in Africa through Training. American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, vol. 71, 253-258. [20] Hussey, David. (1994). Strategic Management: Theory and Practice. 3rd Ed. The Alden Press, Oxford, UK. [21] Katz, Ralph (1998). Managing Professionals in Innova- tive Organizations. Ballinger Publishing Company, Cambridge, Massachusetts. [22] Kpabitey (1996). Five Year Medium Term Development Plan (1996 – 2000). Dangme West District Assembly. [23] Jauch, Lawrence R; Glueck, William F. (1988). Business Policy and Strategic Management. New York: McGraw- Hill Book Company, (5th. Edition). [24] Macmillan, Hugh; Tampoe, Mahen (2000). Strategic Management. Process, Content and Implementation. Oxford University Press Inc. New York. [25] Maister, D. H. (1993). Managing the Professional Ser- vices Firm. Free Press, New York. [26] Mintzberg, Henry (1978). Patterns in Strategy Formula- tion. Management Science 24, No 9. [27] Ministry of Health (2003). 5 Year Program of Work. Ministry of Health, Ghana. [28] Ministry of Health (2000). Roll Back Malaria Strategic Plan for Ghana. MOH: Ghana. [29] Ofosu Amaah, V. (1983). National Experience in the Use of Community Health Workers: A review of Current Is- sues and Problems. World Health Organization. Geneva. [30] Paul, Samuel (1983). Strategic Management of Devel- opment Programs: Evidence from an International Study. International Review of Administrative Sciences 1/1983, 73-86. [31] Porter, Michael (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. The Free Press, New York. [32] Robbins, S; Bergman, R; Stagg, I; Coulter, M. (2000). Management. Prentice Hall, New Jersey [33] Scott, M. C. (1998). Profiting and Learning from Profes- sional Service Firms. Wiley & Sons, Chichester. [34] Senge, P. M, (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of Learning Organization. Doubleday, New York. [35] Sprague, R. H; McNurlin, B. C. (1993). Information Systems in Practice. 3 rd Ed., Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. [36] Business Dictionary.com. (2010). [37] Gardner, James R; Rachlin, Robert; Allen, Swe eny H. W. (1986). Handbook of Strategic Planning. John Wiley & Sons, New York. [38] Teklehaimanot, A. (2005). Coming to grips with malaria in the new millennium. UN Millennium Project. Working Group on Malaria.

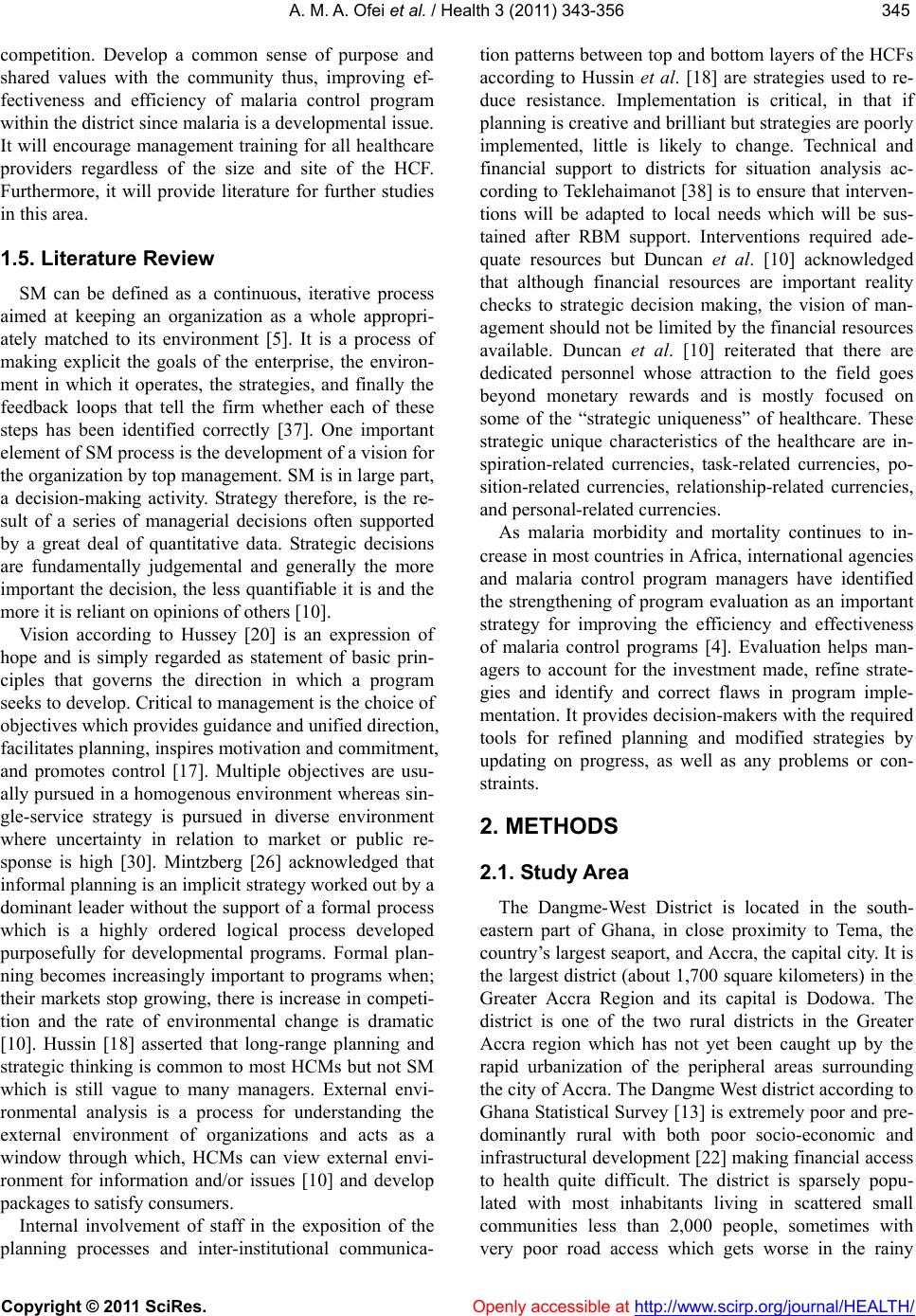

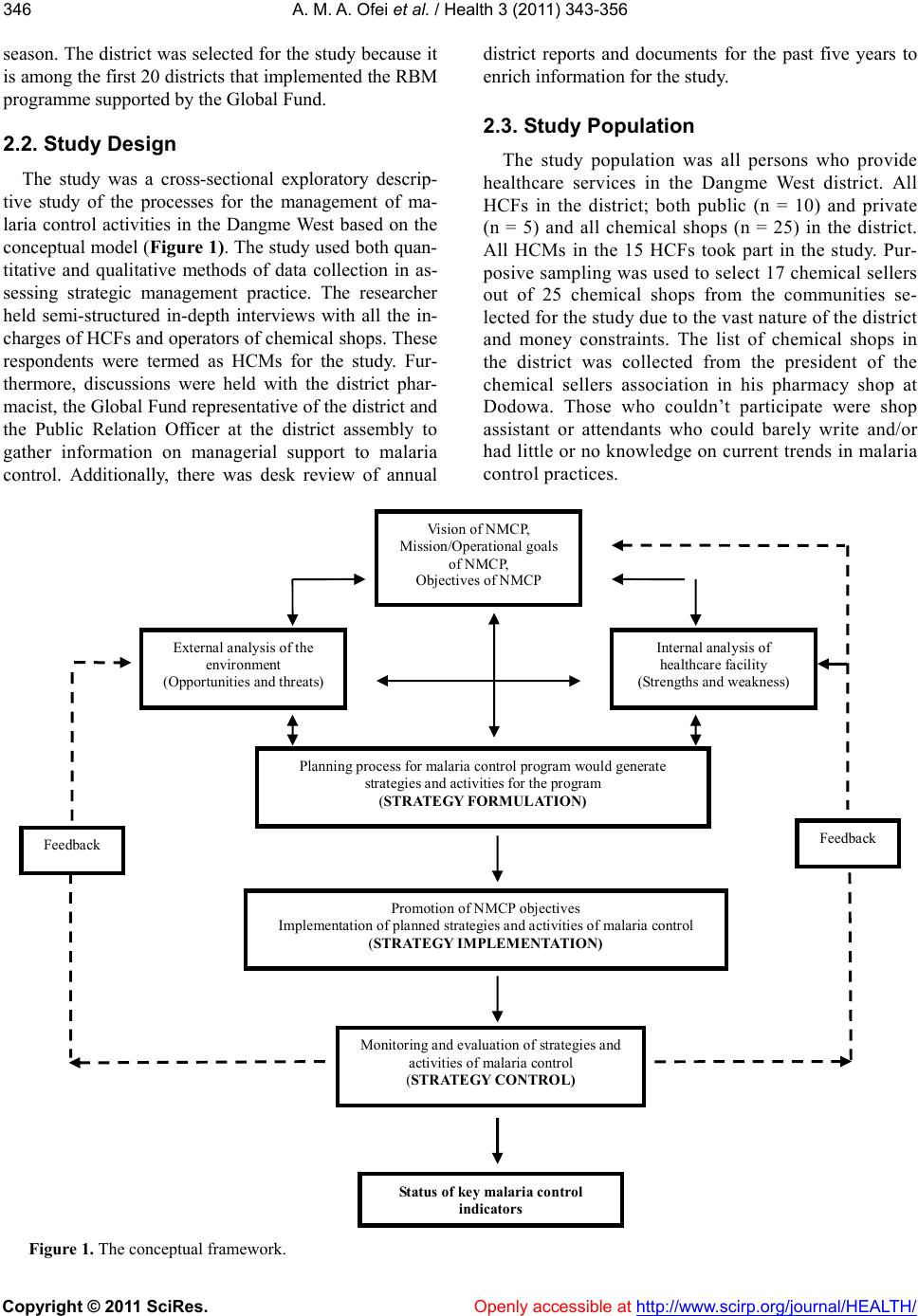

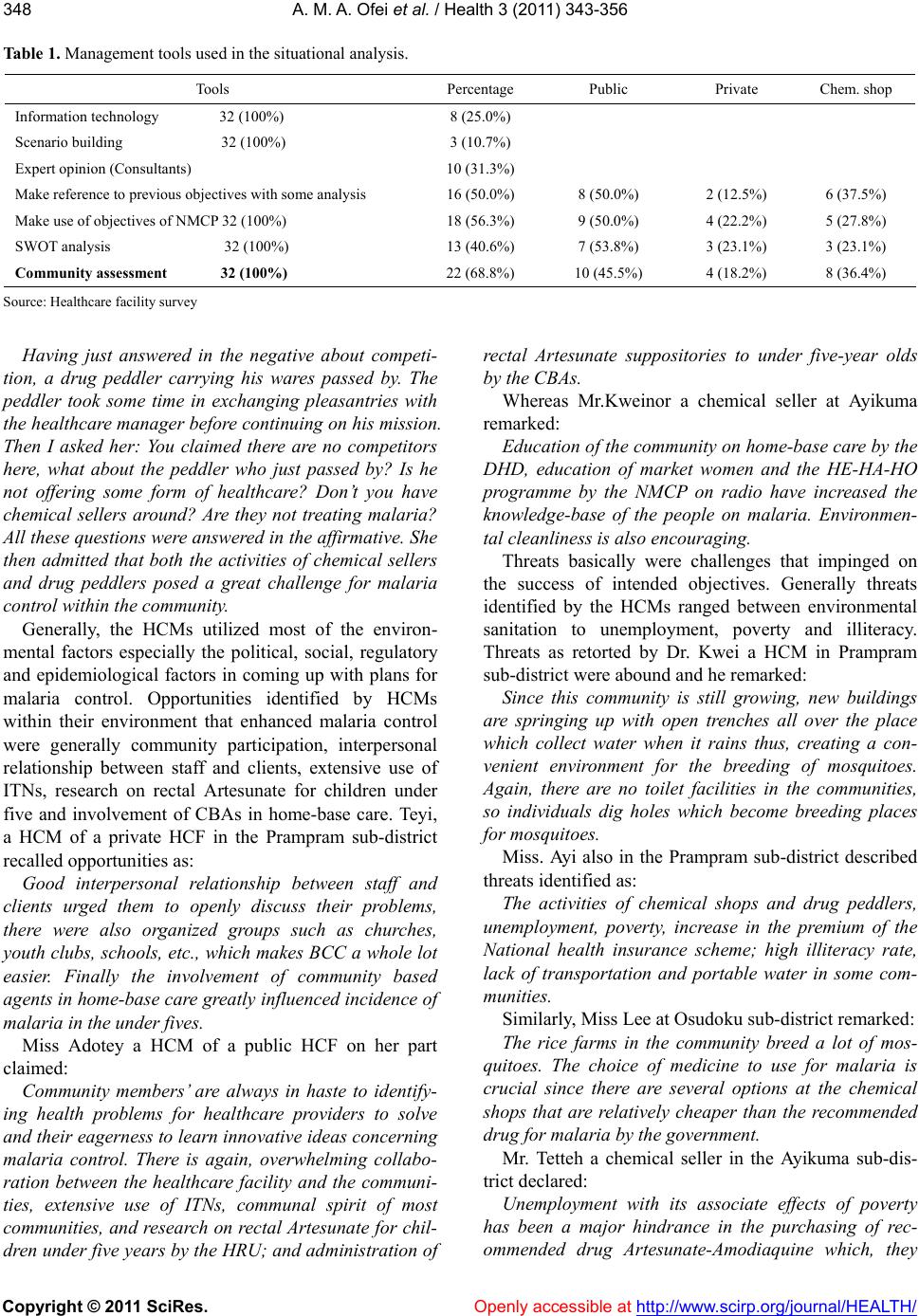

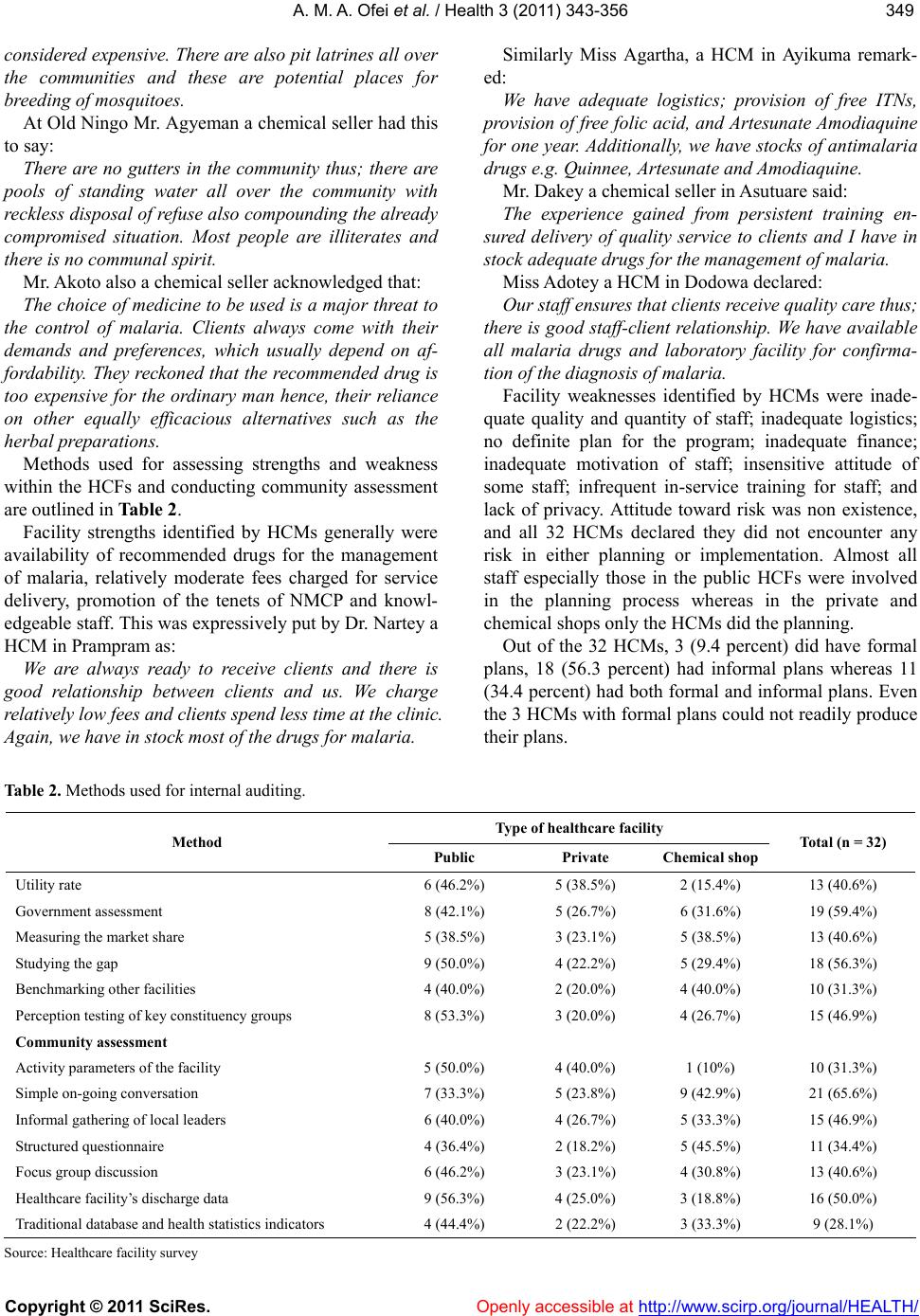

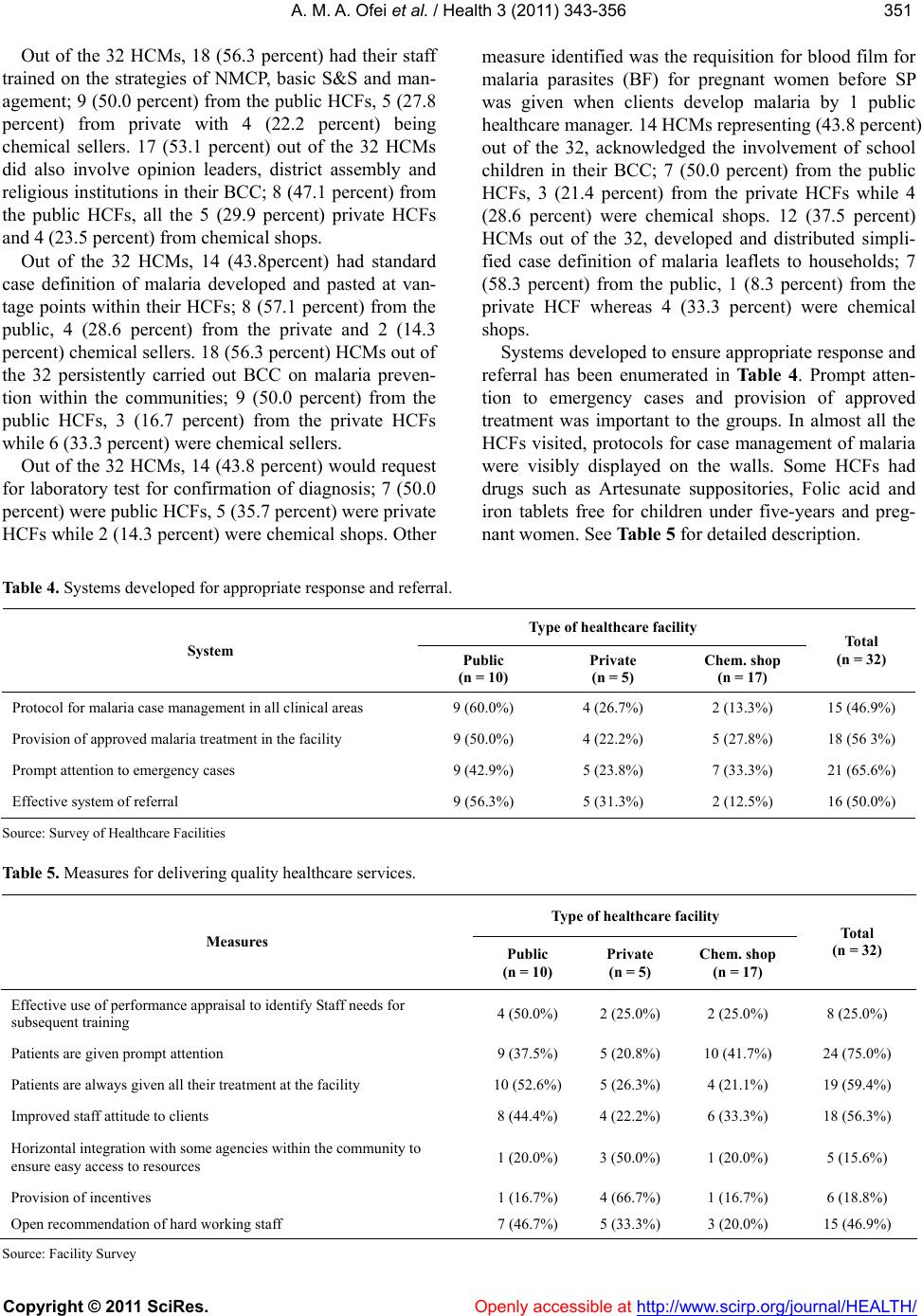

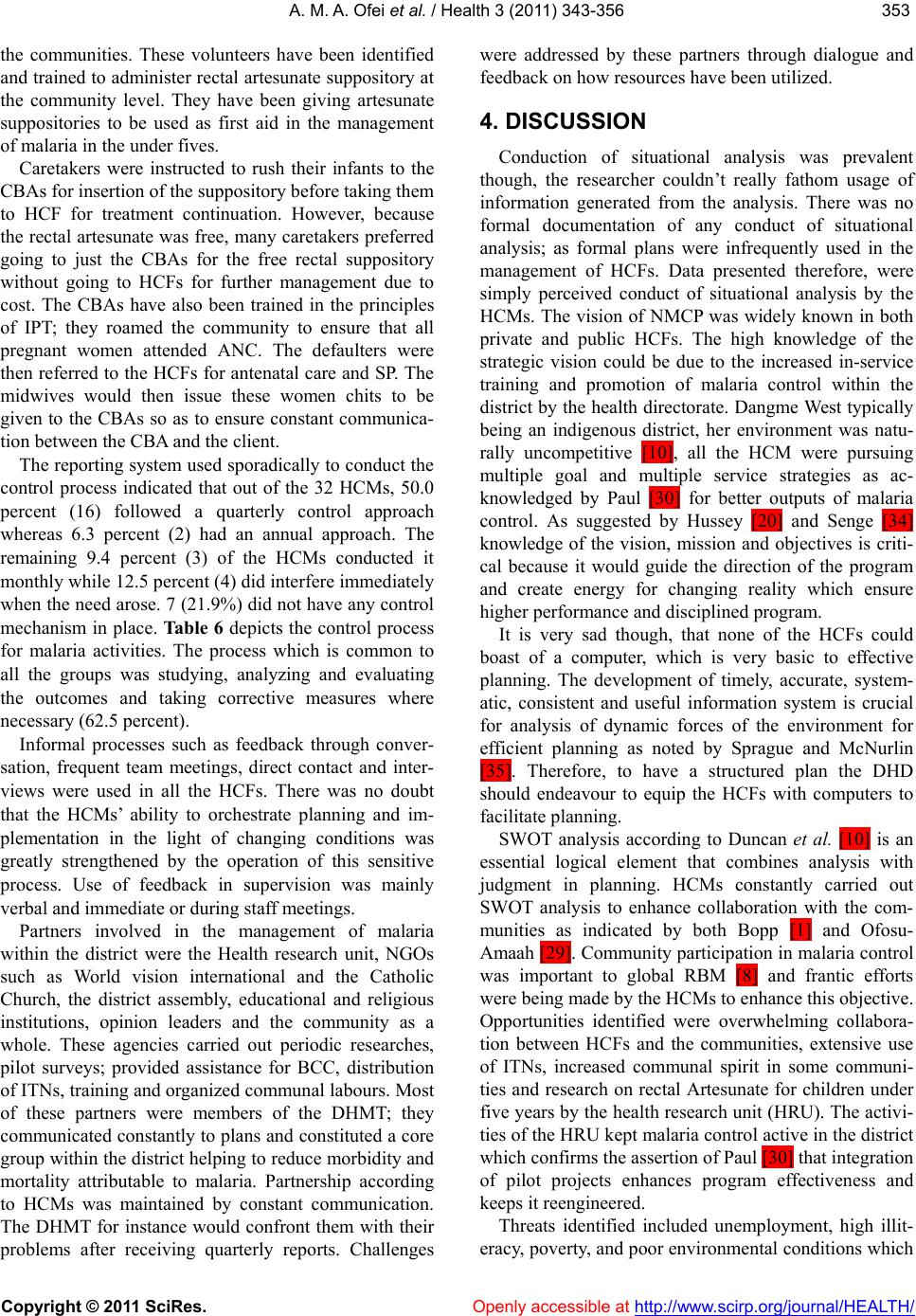

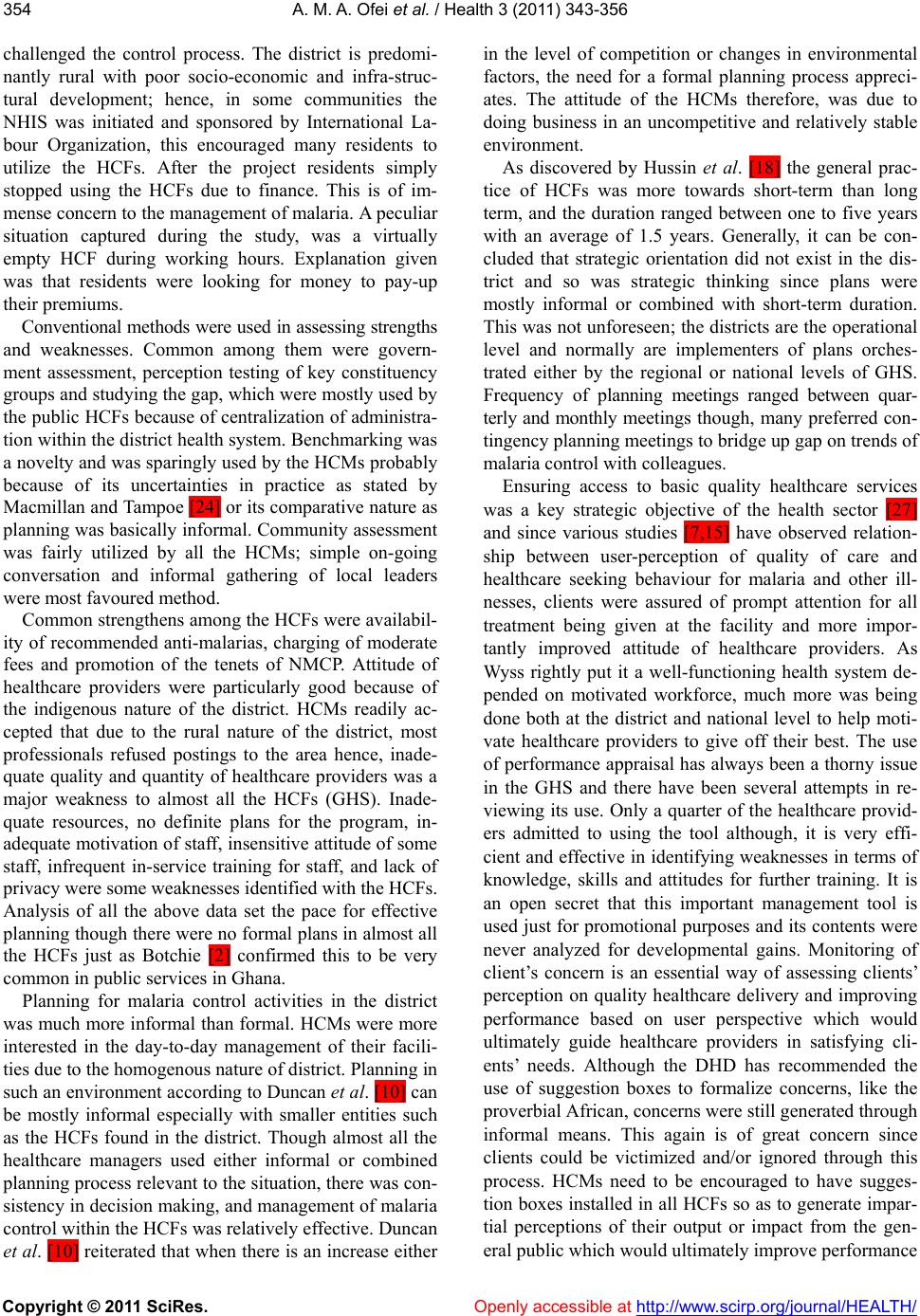

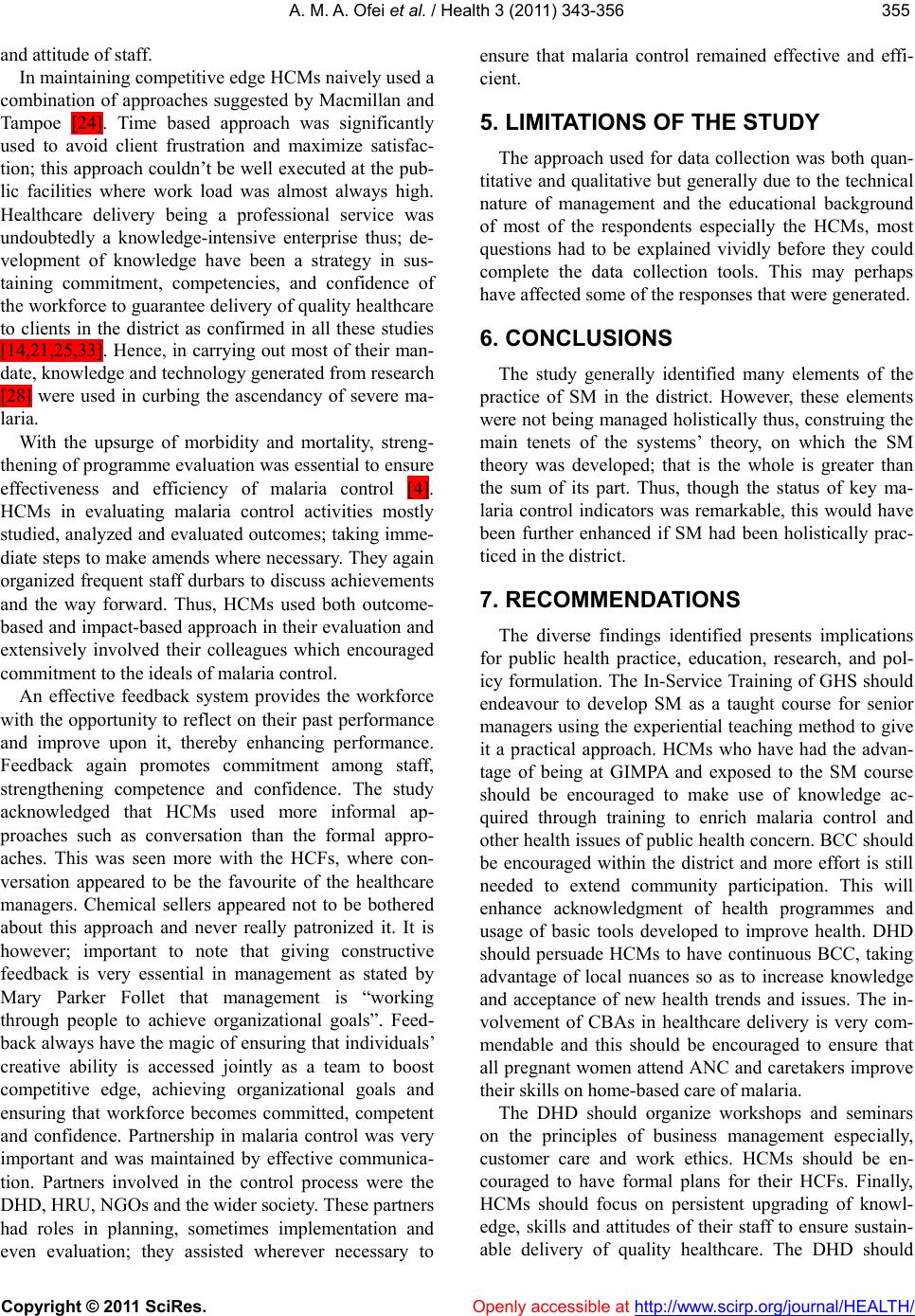

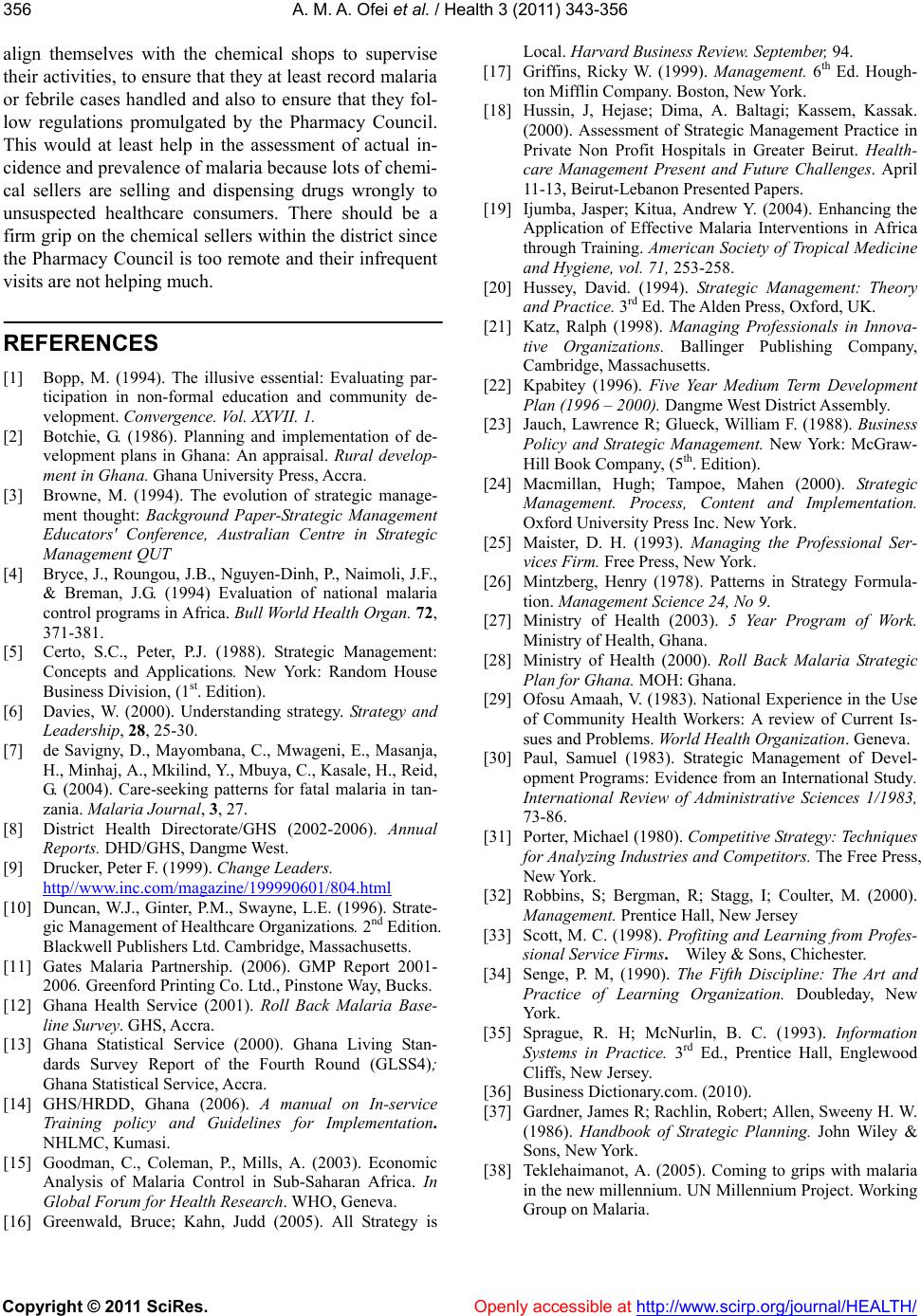

|