Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics

Vol.03 No.02(2015), Article ID:53653,10 pages

10.4236/jamp.2015.32017

The Effective Chiral  Model of Quantum Hadrodynamics Applied to Nuclear Matter and Neutron Stars

Model of Quantum Hadrodynamics Applied to Nuclear Matter and Neutron Stars

Hiroshi Uechi

Osaka Gakuin University, Suita, Japan

Email: uechi@ogu.ac.jp

Received 9 October 2014

ABSTRACT

We review theoretical relations between macroscopic properties of neutron stars and microscopic quantities of nuclear matter, such as consistency of hadronic nuclear models and observed masses of neutron stars. The relativistic hadronic field theory, quantum hadrodynamics (QHD), and mean-field approximations of the theory are applied to saturation properties of symmetric nuclear and neutron matter. The equivalence between mean-field approximations and Hartree approximation is emphasized in terms of renormalized effective masses and effective coupling constants of hadrons. This is important to prove that the direct application of mean-field (Hartree) approximation to nuclear and neutron matter is inadequate to examine physical observables. The equations of state (EOS), binding energies of nuclear matter, self-consistency of nuclear matter, are reviewed, and the result of chiral Hartree-Fock  approximation is shown. Neutron stars and history of nuclear astrophysics, nuclear model and nuclear matter, possibility of hadron and hadron-quark neutron stars are briefly reviewed. The hadronic models are very useful and practical for understanding astrophysical phenomena, nuclear matter and radiation phenomena of nuclei.

approximation is shown. Neutron stars and history of nuclear astrophysics, nuclear model and nuclear matter, possibility of hadron and hadron-quark neutron stars are briefly reviewed. The hadronic models are very useful and practical for understanding astrophysical phenomena, nuclear matter and radiation phenomena of nuclei.

Keywords:

A Relativistic Field Theory of Nuclei: Quantum Hadrodynamics (QHD), The Equivalence of Mean-Field Approximations and Hartree Approximation, Density Functional Theory (DFT), Maximum Masses of Neutron Stars

1. Introduction

1.1. Brief History of Supernova and Neutron Stars

A neutron star is a high density object that is anticipated from the gravitational collapse of a massive star during a supernova explosion. Such stars are hypothesized as high density objects mainly composed of neutrons and supported against further collapse because of Pauli exclusion principle exerted by nuclear particles. Hence, the balance between gravitational force and quantum mechanical force produced by nucleons is considered as the reason for stable existence of neutron stars.

The Fermi energy and pressure are produced by nuclear strong interactions, and therefore, properties of astrophysical phenomena and nuclear strong interactions can be directly interconnected.

This is an active research field of nuclear astrophysics. Several relations between many-body system of strongly interacting particles (nuclear matter) and high density matter, such as neutron, hyperon and quark matter are theoretically expected and explained by using relativistic models of nuclear physics [1].

In seeking an explanation for the origin of supernova and high density stars, neutron stars were proposed to be formed in a supernova explosion process (see, Figure 1). Supernovae are suddenly appearing dying stars expected to occur once in 500 - 1000 years in our galaxy, whose luminosity outshines an entire galaxy for days and weeks.

It is proposed that the release of the gravitational binding energy of neutron stars powers the supernova and if the central part of a massive star before its collapse contains about , a neutron star of

, a neutron star of  can be formed (

can be formed ( : the solar mass). An observed, typical neutron star has a mass from 1.35 to about

: the solar mass). An observed, typical neutron star has a mass from 1.35 to about , with a radius R ~ 12 km. Theoretical calculations of neutron stars were performed by Tolman, Oppenheimer and Volkoff, and in 1967, a radio pulsar was discovered. Radio pulsars are rapidly rotating with periods in the range

, with a radius R ~ 12 km. Theoretical calculations of neutron stars were performed by Tolman, Oppenheimer and Volkoff, and in 1967, a radio pulsar was discovered. Radio pulsars are rapidly rotating with periods in the range . Non-rotating and non-accreting neutron stars were also discussed, whose temperature is expected to be

. Non-rotating and non-accreting neutron stars were also discussed, whose temperature is expected to be  and a radius

and a radius .

.

1.2. Observables of Neutron Stars and High Density Equations of State (EOS)

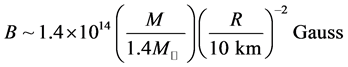

A magnetar is a type of neutron star with an extremely powerful magnetic field, and the emission of copious amounts of high energy electromagnetic radiation is considered as X-rays and gamma rays. The radiation can only be observed when the beam of emission is pointing towards the Earth, which is called the lighthouse effect. The strong magnetic field may have significant effects on both the equation of state (EOS) and the structure of neutron stars.

The magnitude of the magnetic field strength,  , is estimated as,

, is estimated as,

(1)

(1)

where  and

and  are mass and radius of a neutron star. The effect of strong magnetic field on EOS of magnetars is one of the important problems to be investigated. An image and hypothetical structure of a neutron star are shown in Figure 2. The inside of neutron stars is assumed to be composed of hadrons and possibly quarks.

are mass and radius of a neutron star. The effect of strong magnetic field on EOS of magnetars is one of the important problems to be investigated. An image and hypothetical structure of a neutron star are shown in Figure 2. The inside of neutron stars is assumed to be composed of hadrons and possibly quarks.

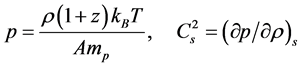

The polytropic equation of state is a useful approximation to consider many cosmological phenomena, because any material will be expected to behave like an ideal gas at a high enough temperature. When the temperature is far enough above the chemical potential or single particle energy of material, its macroscopic behavior is considered well described by a polytropic EOS, for example,

(2)

(2)

Figure 1. An image of neutron star formation after supernova explosion.

Figure 2. A schematic picture of a magnetized neutron star with magnetic field, B, and the rotation axis Ω.

and

(3)

(3)

where

The radiation pressure of blackbody and systems in which radiation is important or dominant is expressed as

where

The radius

is implied from thermal observations of neutron star’s surface. Redshift is defined as

Moments of inertia, I

The physics of neutron stars offers an interesting interplay between nuclear physics and astrophysical observables. The relevant densities of neutron stars are far from the normal nuclear matter density,

The relevant degrees of freedom may not be the same in the crust region where the density is much smaller than the saturation density of nuclear matter, and also, hadronic models may be questionable in the center of the star where density is so high. It is essential to study these questions quantitatively by comparing hadronic and QCD equations of state, and discrepancies of predictions or model-independent predictions of both hadronic and quark theories are important in order to understand nuclear physics and sub-nuclear microscopic dynamics.

Within non-relativistic lowest-order Brueckner theory, it suggests that all the new phase-shift equivalent nucleon-nucleon potentials yield essentially similar equations of state up to densities of

However, the relativistic approaches, three-body interactions, onset of hyperons, pion and kaon condensations, superfluidity, and hadron-quark phase transitions are known to yield significant corrections to EOS above saturation density. In order to obtain consistent results from different approaches, it is essential to examine conditions and constraints to nuclear models and calculations.

2. Nuclear Matter as the Assemblage of Protons and Neutrons

B. D. Serot and J. D. Walecka started applications and analyses of relativistic field theory of nucleons known as quantum hadrodynamics (QHD) [5] [6] to properties of nuclear matter and neutron stars. Since then, so many papers concerning nuclear astrophysics have been published and the field has developed as an active interdisciplinary discipline between nuclear physics and astrophysics.

As one of the extended QHD models, the chiral effective

where

If coulomb forces were negligible and the number of nucleus was so large that the nucleus was the size of neutron stars

Figure 3. Nuclear matter is a self-bound system.

The mean-field approximation of (7) and other analogous nonlinear hadronic models are defined by replacing meson quantum fields with classical fields as,

and pion does not appear directly in the level of mean-field (Hartree) approximation, but the pion contributions appear from HF approximation. The definition of mean-field approximation is equivalent to Hartree approximation [6]-[8].

When J. D. Walecka introduced the mean-field approximation by replacing meson fields with classical fields, it was shown by B. D. Serot [6] that the mean-field approximation is equivalent to Hartree (tadpole diagrams) approximation (see, Figure 4). This fact is important to understand and extend calculations of the mean-field approximations.

3. The Equivalence between Mean-Field Approximations and the Hartree Approximation

Although the QHD calculations have been successful during the last quarter of 20th century, the original QHD model and approximations to QHD have been extended by including nonlinear interactions of mesons and chiral symmetry (reviews in Chapters 2, 3 and 5, 6 in [1] and references are highly recommended to interested readers).

Nonlinear hadronic models and chiral effective models based on QHD generate nonlinear interaction terms in the form of

much less than 1). The requirement of renormalizability in the level of Lagrangian is abandoned in the effective model of hadrons, but the nonlinear terms are considered as effective interactions in the level of approximations to QHD.

It is shown that nonlinear interactions are interpreted as manifestations of many-body interactions of hadrons and renormalized as effective masses

Figure 4. The mean-field (Hartree) approximation in terms of tadpole diagrams.

Figure 5. Effective masses of nucleons and mesons in the mean-field approximation of nonlinear chiral Hartree approximation (CHA) [7].

The self-consistency of approximations is essential to prove that all nonlinear approximations with meson interactions are equivalent to the mean-field approximation (Hartree approximation). The requirement of self- consistency is rigorously examined by the functional derivative of energy density,

where

4. The Dirac-Hartree-Fock

The equivalence of the mean-field approximation with the Hartree approximation indicates that the mean-field approximation is not sufficient as the first approximation to nuclear matter. The exchange contributions, Fock terms, should be included, which are as important as the Hartree approximation. Hence, the self-consistent Dirac-Hartree-Fock approximation is sufficient for the first approximation to nuclear matter.

It is important to emphasize that the fundamental requirement (9) is necessary to construct the self-consistent DHF approximation, which is termed as the conserving DHF approximation (CDHF) [11] [12]. The Feynman diagram representation of Hartree-Fock approximation is shown in Figure 6.

One should be careful that the construction of HF approximation as well as other sophisticated approximations by way of Feynman diagram method or the functional derivative method are not necessarily equivalent [8]. The retardation interactions (energy transfers) in interaction processes cause the discrepancy between the Feynman diagram and density functional methods. The self-consistent renormalization of interactions should be carefully defined in an approximation and should be checked by the Equation (9).

The CDHF approximation improves experimental values derived from Hartree (mean-field) approximation, and physical reasons for the improvement can be explained by the binding energy curve at nuclear matter saturation density (Figure 7) and the saturation curves given by Hartree-sector and Fock-sector contributions, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 6. The Feynman diagram for nucleons and mesons in HF approximation.

Figure 7. Binding energy curves derived from CHA and CHFA. VFC means the vacuum fluctuation corrections.

Figure 8. The contributions to binding energy from Hartree and Fock terms, respectively.

The exchange interactions (Fock contributions) to binding energy are important at low densities compared to Hartree contributions and should not be neglected for nuclear matter calculations.

Therefore, mean-field (Hartree) approximations with nonlinear interactions proposed by other researchers are not sufficient to examine nuclear matter calculations. One can conclude that Hartree-Fock approximation is the correct ground state for nuclear matter calculations.

The equation of state (EOS) derived from the conserving effective CDHF

where

The exchange interactions produce attractive interactions at low densities similar to those of Hartree contributions, which render the EOS of Hartree approximation softer around saturation density. The parameters of the effective chiral mean-field model are

It shows that self-consistency and chiral-symmetry are essentially related to saturation mechanism and confined by physical quantities, such as self-energies, effective masses of baryons and mesons, effective meson- nucleon coupling constants and properties of neutron stars.

In the calculation, nuclear symmetry energy,

where

the conserving effective DHF

5. Hadron and Hadron-Quark (H-Q) Neutron Stars

The stability criterion for neutron stars is given by the derivative of neutron star mass with respect to central energy:

The MIT-bag model of QCD is employed to the equation of state for quark-phase calculations. The equation of state generated by MIT-bag model is connected to the hadronic phase (assumed the first-order phase transition) to calculate hadron-quark neutron stars [14].

As hadron-quark (H-Q) stars are 2-phase compact stars (i.e., the quark phase for a star’s core and hadron phase for a mantle), the stability of H-Q stars should be considered carefully. One can see that the quark-core (monotonically increasing dotted line in Figure 9) has a simple positive slope,

Hence, the stability criterion,

The Figure 9 indicates that stable pure hadronic stars

The total mass of H-Q stars decreases at high densities (

star-core with quark particles by way of hadron-quark phase transition, resulting in the development of a stable quark-core.

Therefore, the H-Q star is stable in the sense that a stable quark-core is developing, although the total mass of the star decreases. The decreasing mass of hadron-mantle or equivalently the decreasing energy of hadron-man- tle could be used to convert hadrons to produce free quark particles in the deconfined vacuum relative to the confined vacuum, which may be the concept of the bag-constant,

By comparing stable energy densities of the quark phase with those of H-Q stars, the central energy density of stable H-Q stars is found to be extended at higher densities than that of single phase stars. This suggests that compact stars consisting of a mantle and a high density core are more stable at extremely high densities than stars in a homogeneous single phase structure [15] [16].

When the QCD coupling constant,

Figure 9. Hadron (solid curve) and hadron-quark (dotted-curve) neutron stars.

Figure 10. Imaginary pictures of pure hadron (left) and hadron- quark (right) neutron stars.

and (

Although neutron stars and high density objects have been discussed in a rigorous fashion, they are still in a state of conjecture because of unknown, uncertain observables and parameters of theories and experiments. The interactions of related fields are important for the progress of science and understanding of nuclear astrophysics.

6. Conclusions on the Hadronic Nuclear Mean-Field Theory

The mean-field approximations by replacing meson quantum fields with classical fields in nuclear hadronic models are all equivalent to the Hartree approximation when nonlinear interactions are properly renormalized [17]. It immediately suggests that exchange contributions (Fock interactions) should be included and the Hartree-Fock approximation must be employed as a correct ground state approximation to examine properties of nuclear matter and neutron stars. The contributions from Fock exchange interactions are important to evaluate experimental values of nuclear and neutron stars, and mean-field calculations should be extended.

The hadronic model employed in Section 4 yields reasonable results for properties of nuclear and neutron stars. However, the scalar

The nuclear physics and astrophysics are interrelated on the fundamental level, and hence, discoveries of each field would generate remarkable progresses on theories and technologies for both fields. The knowledge of nuclear physics is important for applications to diverse fields of science. Nuclear energy has been investigated to maintain the energy requirement for our societies. Radioactive materials are very useful for studies and applications of diverse fields. The progress of technologies to control energies is therefore essential, and we have to understand nuclear energies as clearly as possible both in theoretical structures and technological applications in order to control them for the purpose of our societies and environments.

Cite this paper

Hiroshi Uechi, (2015) The Effective Chiral Model of Quantum Hadrodynamics Applied to Nuclear Matter and Neutron Stars. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics,03,114-123. doi: 10.4236/jamp.2015.32017

References

- 1. Uechi, H., Uechi, S.T. and Serot, B.D. (2012) Neutron Stars: The Aspect of High Density Matter, Equations of State and Observables. Nova Science Publishers, New York.

- 2. Baym, G. and Pethick, C. (1978) In: Bennemann, K.H. and Ketterson, J.B., Eds., The Physics of Liquid and Solid Helium, Part II, John Wiley, New York.

- 3. Lattimer, J.M. and Prakash, M. (2007) Phys. Rep., 442, 109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2007.02.003

- 4. Heiselberg, H. and Hjorth-Jensen, M. (2000) Phys. Rep., V328, 237. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0370-1573(99)00110-6

- 5. Walecka, J.D. (1974) A Theory of Highly Condensed Matter. Annals of Physics (N.Y.), 83, 491. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(74)90208-5

Walecka, J.D. (1995) Theoretical Nuclear and Subnuclear Physics. Oxford University Press, New York. - 6. Serot, B.D. and Walecka, J.D. (1986) Advances in Nuclear Physics, Vol. 16. Negele, J.W. and Vogt, E., Eds., Plenum, New York.

- 7. Uechi, S.T. and Uechi, H. (2009) The Open Nuclear and Particle Physics Journal, V2, 47. Uechi, S.T. and Uechi, H. (2010) arXiv:1003.3630 [nucl-th]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1007.3630

- 8. Uechi, H. (2004) Progress of Theoretical Phys., 111, 525. http://dx.doi.org/10.1143/PTP.111.525

- 9. Baym, G. and Kadanoff, L.P. (1961) Phys. Rev., 124, 287. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.124.287

Baym, G. (1962) Phys. Rev., 127, 1391.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.127.1391 - 10. Kohn, W. and Sham, L.J. (1965) Phys. Rev., 140, A1133. Kohn, W. (1999) Rev. Mod. Phys., 71, 1253. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.71.1253

- 11. Uechi, H. (2012) The Annual Meeting of Japan Physical Society (JPS), Sept. 26aHB-6.

- 12. Takada, Y. (1995) Phys. Rev., B52, Article ID: 12708.

- 13. Misner, C.W., Thorne, K.S. and Wheeler, J.A. (1973) Gravitation. W. H. Freeman and Company.

- 14. Serot, B.D. and Uechi, H. (1989) Ann. of Phys., 179, 272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(87)90137-0

Uechi, S.T. and Uechi, H. (2009) Advances in High Energy Phys., Article ID: 640919.

Uechi, S.T. and Uechi, H. (2010) arXiv:1003.4815 [nucl-th].

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1003.4815v1. - 15. Witten, E. (1984) Phys. Rev., D30, 272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.30.272

- 16. Farhi, E. and Jaffe, R.L. (1984) Phys. Rev., D30, 2379. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.30.2379

- 17. Uechi, H. (2006) Nucl. Phys. A, 780, 247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2006.10.015

Uechi, H. (2008) Nucl. Phys. A, 799, 181.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2007.11.003