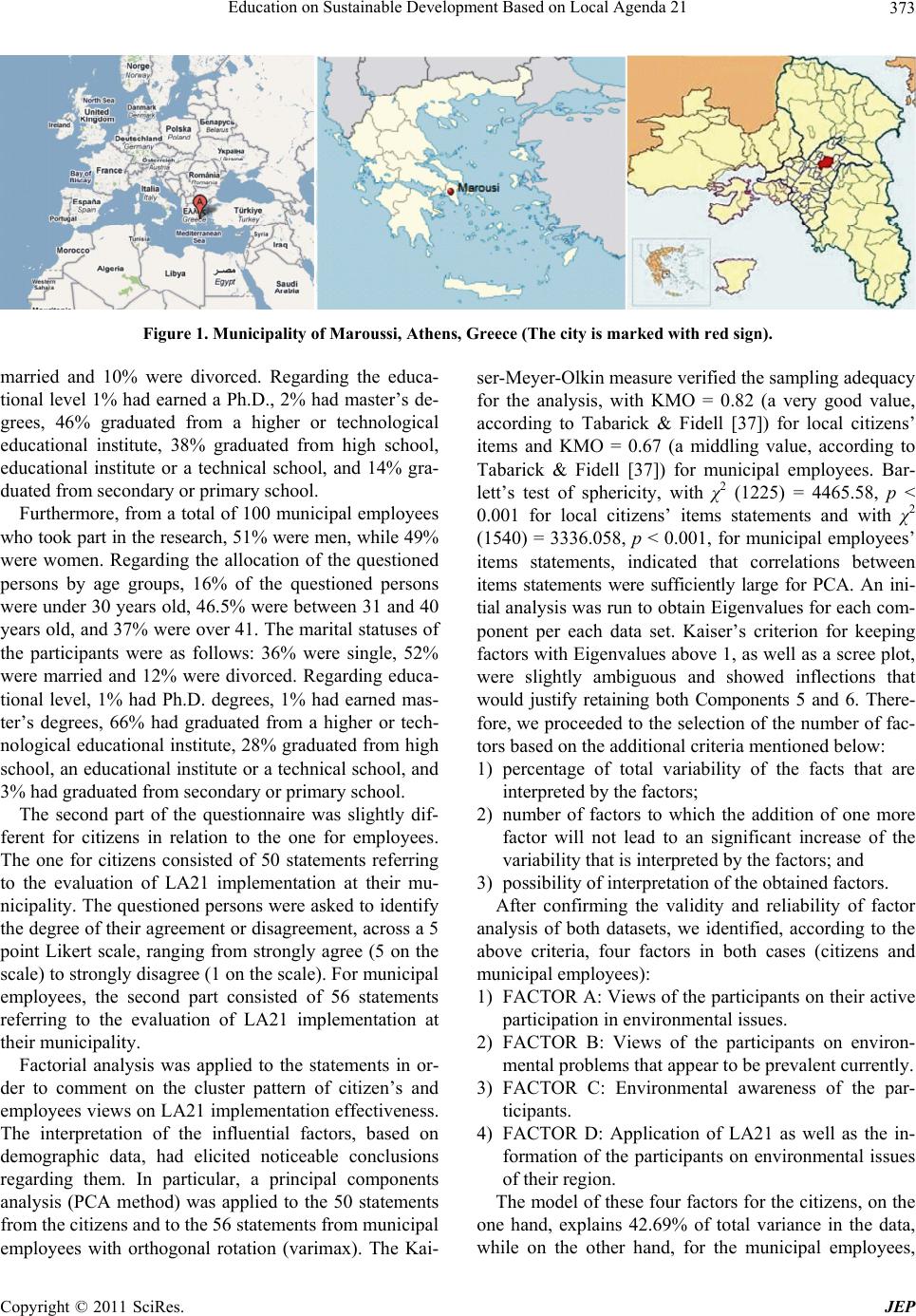

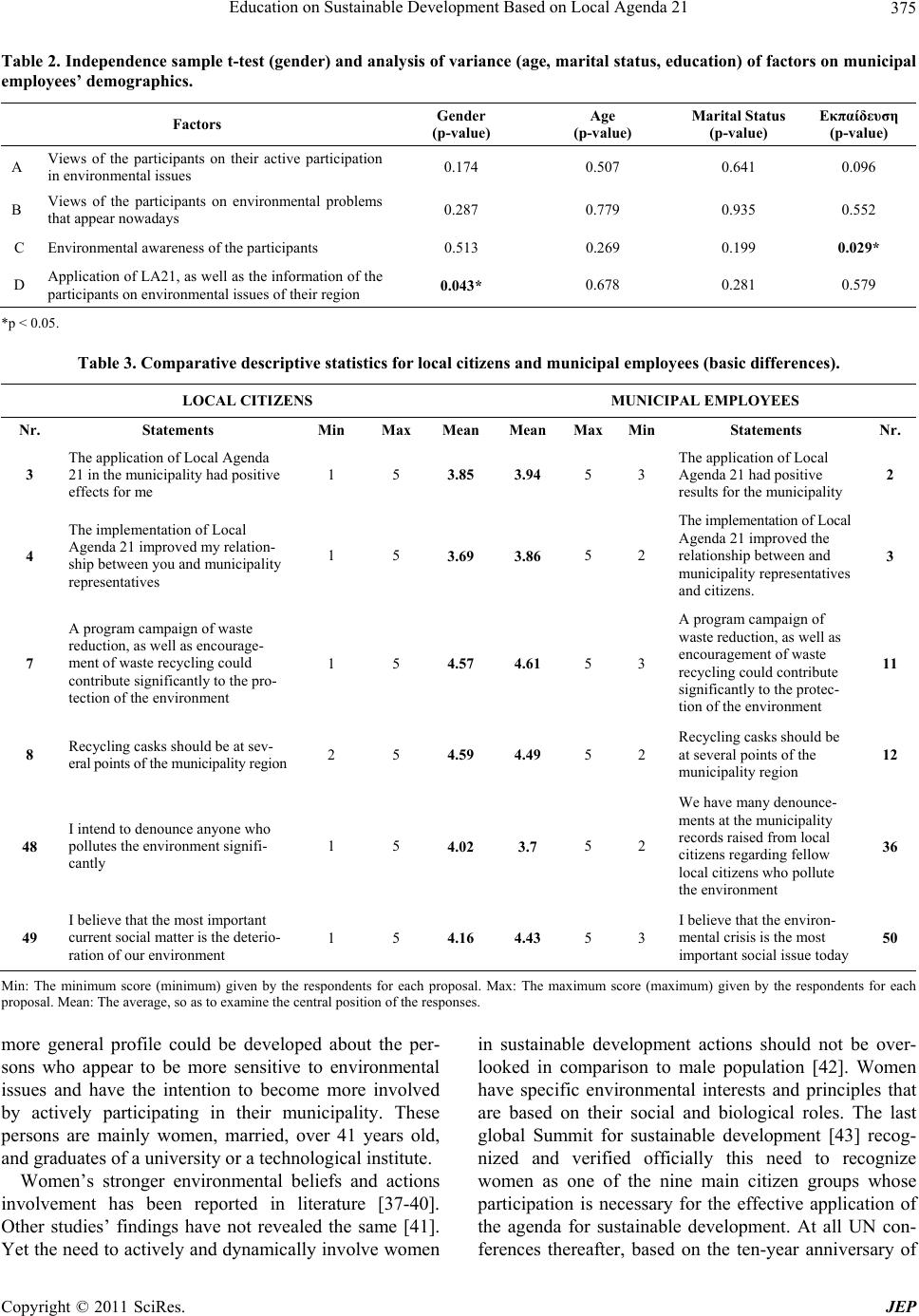

Journal of Environmental Protection, 2011, 2, 371-378 doi: 10.4236/jep.2011.24041 Published Online June 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jep) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 371 Education on Sustainable Development Based on Local Agenda 21 Constantina Skanavis, Polytimi Zacharaki, Christos Giannoulis, Vasiliki Petreniti Department of Environment, University of the Aegean, Greece. Email: cskanav@aegean.gr, cgiannoulis@env.aegean.gr Received January 15th, 2011; revised February 21st, 2011; accepted April 2nd, 2011. ABSTRACT The study is contextualized through evaluating the implementation of Local Agenda Action Plan (LAAP). The goal was to address environmental challenges facing a city under the framework of sustainable development and planning. The evaluation of this conceptual framework was tested at a selected municipality of Athens (Greece), that has used a LAAP. The research was based on a structured questionnaire survey of a sample of 300 respondents selected from municipal employees (100 persons) and citizens of the selected municipality (200 persons). Analysis and interpretation of data through descriptive and factor analysis statistics establish that both municipality employees and citizens are primarily concerned with issues of environmental management. They firmly believe that sustainability initiatives at municipality might best be implemented through a collaborative approach at the local community level, involving local citizens working in partnership with local government. Furthermore, the study established the importance of education, aware- ness and training as a response to environmental issues currently facing the municipality. The awareness and training activities should be developed and should involve the members of the community in the needed environmental manage- ment processes. In view of the Decade Education for Sustainable Development (UNESCO 2 005-2015), this should en- able the Council to create opportunities for income generation, while simultaneously promoting citizens’ environmental responsible behaviors and improving service delivery by municipality employees. Keywords: Environmental Policy, Local Agenda 21, Education, Sustainable Development, Greece, Evaluation 1. Introduction 21 had lofty ambitions. Many hoped that the adoption of Agenda 21 would lead to new era of environmental sus- tainability around the world, while at the same time would reduce poverty. Although considerable gains have been made in some areas of sustainable development, many of the world’s most pressing development and en- vironmental problems continue to remain unaddressed almost 20 years after the initiation idea of Agenda 21. Moreover, the multilateral trading system is showing very few signs of improving market access conditions for agricultural products from developing countries. These observations have led to the conclusion that Agenda 21 has been largely unsuccessful and that some alternative development trajectory must be found. Agenda 21 estab- lished the UN Commission on Sustainable Development, which was given the task of overseeing its implementa- tion. In 2002, the UN held the World Summit on Sus- tainable Development (dubbed “Rio +10”) in Johannes- burg, South Africa, to review the implementation of Agenda 21 and to forge a new implementation strategy Sustainable development presupposes public participa- tion in local government. The context for this role has come from the argument of academics and others that it is only public participation at local scale that sustainabil- ity can be enacted and maintained. International support for this position has come from principally following the United Nations Conference on Environment and Devel- opment in Rio de Janeiro in 1992; through Chapter 28 of Agenda 21. The outcome of this conference was the de- velopment of a lengthy action plan that pertains to a wide variety of problems regarding the environment, devel- opment and social equity [1]. In Chapter 28 of Agenda 21, the local authorities of each country are called to proceed to consulting procedures with local populations in order to achieve their consent to Local Agenda 21 (LA21) [2]. The LA21 is focused on the role of local government in the application of sustainable develop- ment programs in each country [3]. Needless to say, the governments that drafted Agenda  Education on Sustainable Development Based on Local Agenda 21 372 [4]. This summit underlined the importance of local gov- ernments as the main component of sustainable devel- opment [5], and established the requirements for its achievement starting from the need to educate citizens on the issue. In this framework, the Declaration of the Dec- ade of Education for Sustainable Development 2005- 2015 was stated. According to the International Council for Local En- vironmental Initiatives (ICLEI), LA21 procedures are applied, or will soon be, in 6400 European Local Gov- ernment Organizations (LGO). The first countries in Europe to proceed with Local Agenda 21 were Ireland and Sweden with 288 municipalities totally. Denmark, with two-thirds of its municipalities, and the United Kingdom, with 90% of its municipalities implementing Local Agenda 21 are also in the frontline of this effort to ensure sustainable development at the local level. Italy follows with a percentage of 30%, while the performance of Cataluña is remarkable. In Australia, a national strat- egy for Local Agenda 21 has been adopted with more than 60 municipalities having applied it. In other coun- tries, the decision to apply Local Agenda 21 has intro- duced radical changes to the structure of their local gov- ernments, such as the creation of interdisciplinary plan- ning units or the creation of state administration units in neighborhoods and villages. In Peru, the Cajamarca prov- ince started the application of Local Agenda 21 by the decentralization of its administration in 76 urban and rural administrative units, so as to encourage local par- ticipation and to ensure transparent procedures in the establishment of Local Agenda 21 [6]. ICLEI studies show that although many municipalities have made significant progress, the majority have not worked on LA21 and its efficient application [7,8]. Al- though the reasons for this are diverse, they are funda- mentally explained by the difficulties, costs and risks perceived by local governments [9]. Garcia-Sanchez & Prado-Lorenzo’s [10] reveal that the social participation plan, which is a vital element in the success of the mu- nicipality’s action, is only implemented in 62% of the cities and towns participating in LA21 in the European Union (EU). Similarly, Pini and Mckenzie’s [11] study show limited community involvement in environmental management in rural local government areas in Australia. Regions in South Europe have made little progress re- garding the application of LA21 [12]. Greece is a repre- sentative example of such pattern. According to ICLEI study, 39 cases out of 1031 LGO have implemented LA21 procedure. Three municipalities though, have placed the state of art in LA21 procedures implementation. Of these, two are in the extended Athens area (Maroussi and Chalandri), and the third is in the island of Crete (mu- nicipality of Heraclion). Studies addressing LA21 evolution describe its appli- cation in various countries, such as Portugal [13,14], Ja- pan [15], Spain [16], Germany [17], Italy [18], Turkey [19], Dominican Republic, Grenada and Santa Lucia [20], Basque region [21], Australia [22,23] and various other cities [24-32] These studies analyze data, derived from procedures and structural changes monitoring, both at lo- cal and national levels, in order to evaluate the evolution of LA21 application, its outcome and drawbacks experi- enced. Although most of these studies emphasize the role that active citizens could play in the efficient application of LA21, most research is focusing only on the action taken by LGO. In practice the role of citizens has not been re- searched adequately. Consequently we have little infor- mation on citizens’ knowledge and skills to effectively respond to LA21. Same goes for LGO motivation to educate citizens. Civic participation concerns are some- how addressed by Bullard [33] and Lindström and Johnsson [34]. On the other hand it has been demon- strated that citizens’ environmental education enhances environmental knowledge and skills that could build their active participation in decision-making processes and strengthen their support of LA21 [35]. This paper at- tempts to address the above mentioned concerns in one Greek municipality where LA21 implementation has received considerable attention. The aim of this research is the assessment of citizens and employees’ views re- garding local government ability and effectiveness to implement LA21 procedures in order to address envi- ronmental problems. 2. Method and Data Collection A structured questionnaire was designed in consideration of collecting data from a random sample of local popula- tion. The sample consisted of 300 persons, or 3% of the total population that covers the region of the study (the municipality of Maroussi). A hundred of the participants work in the municipality of Maroussi (Figure 1), while the remaining 200 are residents in the same municipality. The first part of the questionnaire included some demographic questions (e.g., sex, age, marital status, place of residence, main degree and profession for citizens, while municipality employees were asked to answer ad- ditional questions regarding years of service and mu- nicipality department where they work). In particular, from the 200 local citizens who partici- pated in the research, 49.5% were men, while 50.5% were women. As far as the allocation of the questioned per- sons by age group is concerned: 21% of the participants were less than 30 years old, 25% were between 31 and 40 years old, while 54% were over 41 years old. Regard- ng the marital status 34% were single, 55% were i Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Education on Sustainable Development Based on Local Agenda 21 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 373 Figure 1. Municipality of Maroussi, Athens, Greece (The city is marked with red sign). married and 10% were divorced. Regarding the educa- tional level 1% had earned a Ph.D., 2% had master’s de- grees, 46% graduated from a higher or technological educational institute, 38% graduated from high school, educational institute or a technical school, and 14% gra- duated from secondary or primary school. Furthermore, from a total of 100 municipal employees who took part in the research, 51% were men, while 49% were women. Regarding the allocation of the questioned persons by age groups, 16% of the questioned persons were under 30 years old, 46.5% were between 31 and 40 years old, and 37% were over 41. The marital statuses of the participants were as follows: 36% were single, 52% were married and 12% were divorced. Regarding educa- tional level, 1% had Ph.D. degrees, 1% had earned mas- ter’s degrees, 66% had graduated from a higher or tech- nological educational institute, 28% graduated from high school, an educational institute or a technical school, and 3% had graduated from secondary or primary school. The second part of the questionnaire was slightly dif- ferent for citizens in relation to the one for employees. The one for citizens consisted of 50 statements referring to the evaluation of LA21 implementation at their mu- nicipality. The questioned persons were asked to identify the degree of their agreement or disagreement, across a 5 point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree (5 on the scale) to strongly disagree (1 on the scale). For municipal employees, the second part consisted of 56 statements referring to the evaluation of LA21 implementation at their municipality. Factorial analysis was applied to the statements in or- der to comment on the cluster pattern of citizen’s and employees views on LA21 implementation effectiveness. The interpretation of the influential factors, based on demographic data, had elicited noticeable conclusions regarding them. In particular, a principal components analysis (PCA method) was applied to the 50 statements from the citizens and to the 56 statements from municipal employees with orthogonal rotation (varimax). The Kai- ser-Meyer-Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis, with KMO = 0.82 (a very good value, according to Tabarick & Fidell [37]) for local citizens’ items and KMO = 0.67 (a middling value, according to Tabarick & Fidell [37]) for municipal employees. Bar- lett’s test of sphericity, with χ2 (1225) = 4465.58, p < 0.001 for local citizens’ items statements and with χ2 (1540) = 3336.058, p < 0.001, for municipal employees’ items statements, indicated that correlations between items statements were sufficiently large for PCA. An ini- tial analysis was run to obtain Eigenvalues for each com- ponent per each data set. Kaiser’s criterion for keeping factors with Eigenvalues above 1, as well as a scree plot, were slightly ambiguous and showed inflections that would justify retaining both Components 5 and 6. There- fore, we proceeded to the selection of the number of fac- tors based on the additional criteria mentioned below: 1) percentage of total variability of the facts that are interpreted by the factors; 2) number of factors to which the addition of one more factor will not lead to an significant increase of the variability that is interpreted by the factors; and 3) possibility of interpretation of the obtained factors. After confirming the validity and reliability of factor analysis of both datasets, we identified, according to the above criteria, four factors in both cases (citizens and municipal employees): 1) FACTOR A: Views of the participants on their active participation in environmental issues. 2) FACTOR B: Views of the participants on environ- mental problems that appear to be prevalent currently. 3) FACTOR C: Environmental awareness of the par- ticipants. 4) FACTOR D: Application of LA21 as well as the in- formation of the participants on environmental issues of their region. The model of these four factors for the citizens, on the one hand, explains 42.69% of total variance in the data, while on the other hand, for the municipal employees,  Education on Sustainable Development Based on Local Agenda 21 374 reveals 39.92% of total variance in the data. The further addition of more factors in the model does not increase the total variability of the data that is interpreted by the factors. Finally, comparisons of the factor scores were made in order to identify important differences in these among the varying categories of the demographic data (e.g., sex, age, marital status, etc.). In other words, we explored whether the demographics seem to influence the attitudes of both citizens and employees on different is- sues. The significance level in all tests is defined to be equal to 95% (p < 0.05). In cases where the variable has two levels (i.e., sex: male-female), the independent sam- ple t-test was chosen for the comparison of the mean value of the factor scores. In all other cases where the variable has more than 2 levels (i.e. age, education and marital status), the analysis of variance was chosen for the comparison of the mean value of factor scores. 3. Results 3.1. Local Citizens According to the factor analysis comparison of means with the demographic characteristics (Table 1), we found that the views of the citizens concerning their active par- ticipation in environmental issues and the views of the citizens on environmental issues are statistically different, according to their gender (Factors Α, p-value = 0.002 and Factor Β, p-value = 0.032). On the contrary, it was equally supported by both sexes both a positive view regarding the outcome of the application of LA21 and high quality of the relevant information they had re- ceived. Thus, gender influences only two of the four re- search factors. Age seems to influence only the environ- mental consciousness of the citizens (Factor C, p-value = 0.037), while marital status does not appear to influence any of the above mentioned four factors. Finally, educa- tional level constitutes an important point of differentia- tion in the answers of the citizens, as it influences three out of four factors: the views of the citizens concerning their active participation in environmental issues, their environmental consciousness and their information on the environment (Factor Α, p-value = 0.002, Factor C, p-value = 0.004, Factor D, p-value = 0.004). 3.2. Municipal Employees According to the factor analysis comparison of means with the demographic characteristics (Table 2), gender influences only the fourth factor, that is, the views of the municipal employees on the weaknesses of the environ- mental measures already taken (Factor D, p-value = 0.043). On the contrary, demographic data such as age, marital status and years of service do not appear to in- fluence the positive attitude of the municipal employees on research issues, as well as their answers, as all factors remain uninfluenced. Finally, their educational level ap- pears to influence significantly the views of the munici- pal employees on the existing situation (third factor), (p-value = 0.029). The comparative analysis, of the answers given by the citizens of the Municipality of Maroussi and the em- ployees of the municipality, is considered substantial because views between citizens and employees are simi- lar on the issue of the potential effectiveness of LA21 implementation (Table 3) and on the fact that it could improve the municipality-citizens relationship. There is a slight convergence on the importance of their municipal- ity waste management program. The abundance of recy- cle bins in different parts of municipality is considered to be an important factor to the protection of the environ- ment to both groups. While citizens have the intention to report someone that pollutes the environment (score 4.02), this is not carried on as an action (score 3.70). The employees of the municipality appear slightly more sen- sitive on the environmental issues, but with a small dif- ference in the score (4.43 versus 4.16). 4. Discussion Based on the descriptive analysis of the data collected, a Table 1. Independence sample t-test (gender) and analysis of variance (age, marital status, education) of factors on citizens’ demographics. Citizens Factors Gender (p-value) Age (p-value) Marital Status (p-value) Education (p-value) A Views of the participants on their active participation in environmental issues 0.002* 0.646 0.993 0.002 B Views of the participants on environmental problems that appear nowadays 0.032* 0.357 0.494 0.616 C Environmental awareness of the participants 0.536 0.037* 0.601 0.004* D Application of LA21, as well as the information of the participants on environmental issues of their region 0.996 0.704 0.830 0.004* * p < 0.05 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Education on Sustainable Development Based on Local Agenda 21375 Table 2. Independence sample t-test (gender) and analysis of variance (age, marital status, education) of factors on municipal employees’ demographics. Factors Gender (p-value) Age (p-value) Marital Status (p-value) Εκπαίδευση (p-value) A Views of the participants on their active participation in environmental issues 0.174 0.507 0.641 0.096 B Views of the participants on environmental problems that appear nowadays 0.287 0.779 0.935 0.552 C Environmental awareness of the participants 0.513 0.269 0.199 0.029* D Application of LA21, as well as the information of the participants on environmental issues of their region 0.043* 0.678 0.281 0.579 *p < 0.05. Table 3. Comparative descriptive statistics for local citizens and municipal employees (basic differences). LOCAL CITIZENS MUNICIPAL EMPLOYEES Nr. Statements Min Max MeanMean MaxMinStatements Nr. 3 The application of Local Agenda 21 in the municipality had positive effects for me 1 5 3.85 3.94 5 3 The application of Local Agenda 21 had positive results for the municipality 2 4 The implementation of Local Agenda 21 improved my relation- ship between you and municipality representatives 1 5 3.69 3.86 5 2 The implementation of Local Agenda 21 improved the relationship between and municipality representatives and citizens. 3 7 A program campaign of waste reduction, as well as encourage- ment of waste recycling could contribute significantly to the pro- tection of the environment 1 5 4.57 4.61 5 3 A program campaign of waste reduction, as well as encouragement of waste recycling could contribute significantly to the protec- tion of the environment 11 8 Recycling casks should be at sev- eral points of the municipality region 2 5 4.59 4.49 5 2 Recycling casks should be at several points of the municipality region 12 48 I intend to denounce anyone who pollutes the environment signifi- cantly 1 5 4.02 3.7 5 2 We have many denounce- ments at the municipality records raised from local citizens regarding fellow local citizens who pollute the environment 36 49 I believe that the most important current social matter is the deterio- ration of our environment 1 5 4.16 4.43 5 3 I believe that the environ- mental crisis is the most important social issue today 50 Min: The minimum score (minimum) given by the respondents for each proposal. Max: The maximum score (maximum) given by the respondents for each proposal. Mean: The average, so as to examine the central position of the responses. more general profile could be developed about the per- sons who appear to be more sensitive to environmental issues and have the intention to become more involved by actively participating in their municipality. These persons are mainly women, married, over 41 years old, and graduates of a university or a technological institute. Women’s stronger environmental beliefs and actions involvement has been reported in literature [37-40]. Other studies’ findings have not revealed the same [41]. Yet the need to actively and dynamically involve women in sustainable development actions should not be over- looked in comparison to male population [42]. Women have specific environmental interests and principles that are based on their social and biological roles. The last global Summit for sustainable development [43] recog- nized and verified officially this need to recognize women as one of the nine main citizen groups whose participation is necessary for the effective application of the agenda for sustainable development. At all UN con- ferences thereafter, based on the ten-year anniversary of Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Education on Sustainable Development Based on Local Agenda 21 376 the Education for Sustainable Development, gender equality, with special reference to women and girls, has been a common concern, and there has also been a con- sensus that their participation in education is critical for enabling development and sustainability in local gov- ernance. In particular, LA21 evaluation, both from local citi- zens as well as from municipal employees, is considered significant for the increase of the environmental con- sciousness of the citizens, the improvement of the man- agement of environmental problems, the improvement of municipality-citizen relations, the recognition and incor- poration of the LA21 principles to routines of the mu- nicipality, and the increase of the citizens’ participation to everyday issues and their desire to be involved in their resolution. The environmentally friendly profile, revealed by the study’s results, can only be sustained, if funding from the national government supports the necessary enhancement actions. An effective local government must base its operation on a clear application of the LA21 procedures. The LGO have to encourage citizens’ participation in public debates on the environmental problems of the municipality. The rule of thumb would be to have municipality employees truly support the LA21 procedures. Sustainable development educational programs designed to the specific needs of the partici- pants could bring us close to the mentioned challenging goals. Ninety percent of participants express willingness to participate in the municipality procedures but need support in actualizing it. This way LΑ21 would not be limited to recycling actions! LA21 refers to behavior change and successful partnership between local gov- ernment and citizens. Intensions are great but actions are by far better. LA21 effective implementation is linked to environmental education for all. 5. Conclusion From concept to local practice, ongoing debates increas- ingly underline the need to measure education for sus- tainable development capacity based on indicators or evaluation criteria. One of the most common applications consists in comparing municipalities, notably to support local decision-making processes. However, it seems that the actual role of citizens has not been researched ade- quately, especially in view of citizens’ public participa- tion beliefs and priorities. In this article, we try to ad- dress this research gab based on structured questionnaire survey of a sample of municipal employees and local citizens at a selected municipality of Athens (Greece) that has used a LAAP. Although we recognize the sub- jective nature of our approach, we believe that it can al- low a comprehensive mapping of citizens’ environmental profile. The results of our study indicated that the people who show greater intention to participate in environ- mental decision making processes are highly educated married women in the middle of their forties. In addition, our analysis demonstrates that current practices related to Local Agenda 21 implementation cannot meet standard objectives without sustained funding of lifelong envi- ronmental education programs. Considering the contra- diction between the need to obtain indicators that allow comparison between jurisdictions and the desire to reflect local concerns, it is probable that consensus on certain principles as a prerequisite to these objectives being met. Nonetheless, it should be acknowledged that this field will surely benefit from ongoing and future research. REFERENCES [1] P. Jacobi, “Agenda 21 and Cities in Developing Coun- tries,” Politics and the Life Sciences, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2002, pp. 61-65. [2] R. Tuts, “Localizing Agenda 21 in Small Cities in Kenya, Morocco and Vietnam,” Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 10, No. 2, 1998, pp. 175-190. doi:10.1177/095624789801000207 [3] A. L. Owen And J. Videras, “Trust, Cooperation, and Implementation of Sustainability Programs: The Case Of Local Agenda 21,” Ecological Economics, Vol. 68, No. 1, 2008, pp. 259-272. doi:10.1016/J.Ecolecon.2008.03.006 [4] A. Baldwin, “Agenda 21,” In: P. Robbins, Ed., Encyclo- pedia of Environment and Society, Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, 2007, pp. 10-11. [5] M. Joas and B. Grönholm, “A Comparative Perspective on Self-Assessment of Local Agenda 21 in European Cit- ies,” Boreal Environment Research, Vol. 9, No. 6, 2006, pp. 499-507. [6] F. Steinberg and L. Miranda, “Local Agenda 21, Capacity Building and the Cities of Peru,” Habitat International, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2005, pp. 163-182. doi:10.1016/J.Habitatint.2003.07.001 [7] International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, (Iclei), “Second Local Agenda 21 Survey,” United Na- tions Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Back- ground Paper No. 15, 2002. [8] J. M. Barrutia And C. Echebarria, “Developing a New Framework to Explain Transverse Evolution of Knowl- edge-Driven Regional Policy Networks,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2010, pp. 906-924. doi:10.1111/J.1468-2427.2010.00910.X [9] C. Echebarria, J. M. Barrutia And I. Aguado, “The Isc Framework: Modelling Drivers For The Degree Of Local Agenda 21 Implantation In Western Europe,” Environ- ment and Planning A, Vol. 41, No. 4, 2009, pp. 980-995. doi:10.1068/A40301 [10] I. M. Garcia-Sanchez and J. Prado-Lorenzo, “Determinant Factors in the Degree of Implementation of Local Agenda 21 in the European Union,” Sustainable Development, Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Education on Sustainable Development Based on Local Agenda 21377 Vol. 16, No. 1, 2008, pp. 17-34. doi:10.1002/sd.334 [11] F. Mckenzie and B. Pini, “Challenging Local Govern- ment Notions of Community Engagement as Unnecessary, Unwanted and Unproductive: Case Studies From Rural Australia,” Journal Of Environmental Policy & Planning, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2006, pp. 27-44. doi:10.1080/15239080600634078 [12] F. Coenen, “Local Agenda 21: ‘Meaningful And Effec- tive’ Participation?,” In F. Coenen, Ed., Public Participa- tion and Better Environmental Decisions, Springer Neth- erlands, Dordrecht, 2009, pp. 165-182. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9325-8_10 [13] N. Carter, F. N. Da Silva and F. Magalh Es, “Local Agenda 21: Progress in Portugal,” European Urban and Regional Studies, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2000, pp. 181-186. doi:10.1177/096977640000700207 [14] T. Fidelis and S. M. Pires, “Surrender or Resistance yo the Implementation of Local Agenda 21 in Portugal: The Challenges Of Local Governance For Sustainable Devel- opment,” Journal of Environmental Planning and Man- agement, Vol. 52, No. 4, 2009, pp. 497-518. doi:10.1080/09640560902868363 [15] B. Barrett and M. Usui, “Local Agenda 21 in Japan: Transforming Local Environmental Governance,” Local Environment, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2002, pp. 49-67. doi:10.1080/13549830220115411 [16] C. Echebarria, J. M. Barrutia and I. Aguado, “Local Age- Nda 21: Progress In Spain,” European Urban and Re- gional Studies, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2004, pp. 273-281. doi:10.1177/0969776404041490 [17] K. Kern, C. Koll and M. Schophaus, “The Diffusion of Local Agenda 21 in Germany: Comparing The German Federal States” Environmental Politics, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2007, pp. 604-624. doi:10.1080/09644010701419139 [18] W. Sancassiani, “Local Agenda 21 in Italy: An Effective Governance Tool For Facilitating Local Communities Participation And Promoting Capacity Building For Sus- tainability,” Local Environment, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2005, pp. 189-200. doi:10.1080/1354983052000330770 [19] C. Varol, O. Y. Ercoskun and N. Gurer, “Local Participa- tory Mechanisms and Collective Actions for Sustainable Urban Development in Turkey,” Habitat International, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2011, pp. 9-16. doi:10.1016/J.Habitatint.2010.02.002 [20] J. Rosenberg and L. S. Thomas, “Participating or Just Talking? Sustainable Development Councils snd The Im- plementation of Agenda 21,” Global Environmental Poli- tics, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2005, pp. 61-87. doi:10.1162/1526380054127763 [21] J. M. Barrutia, I. Aguado and C. Echebarria, “Networking for Local Agenda 21 Implementation: Learning From Experiences With Udaltalde And Udalsarea In The Basque Autonomous Community,” Geoforum, Vol. 38, No. 1, 2007, pp. 33-48. doi:10.1016/J.Geoforum.2006.05.004 [22] V. Kupke, “Local Agenda 21: Local Councils Managing For The Future,” Urban Policy And Research, Vol. 14, No. 3, 1996, pp. 183-198. doi:10.1080/08111149608551595 [23] D. Mercer and B. Jotkowitz, “Local Agenda 21 and Bar- riers to Sustainability at the Local Government Level in Victoria, Australia,” Australian Geographer, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2000, pp. 163-181. Doi:10.1080/713612242 [24] J. Peris, M. Acebillo-Baqué and C. Calabuig, “Scrutiniz- ing the Link between Participatory Governance and Ur- ban Environment Management. The Experience in Are- quipa During 2003-2006,” Habitat International, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2011, pp. 84-92. doi:10.1016/J.Habitatint.2010.04.003 [25] A. Tonami and A. Mori, “Sustainable Development in Thailand. Lessons from Implementing Local Agenda 21 in Three Cities,” Journal of Environment and Develop- ment, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2007, pp. 269-289. doi:10.1177/1070496507306223 [26] A. Scipioni, A. Mazzi, M. Mason and A. Manzardo, “The Dashboard of Sustainability to Measure the Local Urban Sustainable Development: The Case Study Of Padua Mu- nicipality,” Ecological Indicators, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2009, pp. 364-380. doi:10.1016/J.Ecolind.2008.05.002 [27] J. Feichtinger and M. Pregernig, “Participation and/or/ Versus Sustainability? Tensions between Procedural and Substantive Goals in Two Local Agenda 21 Processes in Sweden and Austria,” European Environment, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2005, pp. 212-227. Doi:10.1002/Eet.386 [28] D. Roberts and N. Diederichs, “Durban’S Local Agenda 21 Programme: Tackling Sustainable Development In A Post-Apartheid City,” Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2002, pp. 189-201. doi:10.1177/095624780201400116 [29] M. Gaye, L. Diouf and N. Keller, “Moving towards Local Agenda 21 in Rufisque,” Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2001, pp. 201-214. doi:10.1177/095624780101300216 [30] I. Roberts, “Leicester Environment City: Learning How To Make Local Agenda 21, Partnerships And Participa- tion Deliver,” Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2000, pp. 9-26. Doi:10.1177/095624780001200202 [31] M. Hordijk, “A Dream of Green and Water: Community Based Formulation Of A Local Agenda 21 In Peri-Urban Lima,” Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 11, No 2, 1999, pp. 11-30. Doi:10.1177/095624789901100203 [32] R. Tuts, “Localizing Agenda 21 in Small Cities in Kenya, Morocco and Vietnam,” Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 10, No. 2, 1998, pp. 175-190. doi:10.1177/095624789801000207 [33] J. E. Bullard, “Raising Awareness of Local Agenda 21: The Use Of Internet Resources,” Journal of Geography in Higher Education, Vol. 22, No. 2, 1998. pp. 201-210. doi:10.1080/03098269885903 [34] M. Lindström and P. Johnsson, “Environmental Concern, Self-Concept and Defence Style: A Study Of The Agenda 21 Process In A Swedish Municipality,” Environmental Education Research, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2003, pp. 51-66. doi:10.1080/13504620303470 [35] C. Skanavis, M. Sakellari and V. Petreniti, “The Potential Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Education on Sustainable Development Based on Local Agenda 21 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 378 of Free-Choice Learning for Environmental Participation in Greece,” Environmental Education Research, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2005, pp. 321-333. doi:10.1080/13504620500081194 [36] B. Tabachnick and L. Fidell, “Using Multivariate Statis- tics,” 5th Edition, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 2007. [37] S. Buckingham-Hatfield, “Gendering Agenda 21: Women’s Involvement In Setting The Environmental Agenda,” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1999, pp. 121-132. [38] L. Zelezny, P. Chua and C. Aldrich, “New Ways of Thinking about Environmentalism: Elaborating On Gen- der Differences In Environmentalism,” Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 56, No. 3, 2000, pp. 443-457. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00177 [39] L. Zelezny and M. Bailey, “A Call for Women to Lead A Different Environmental Movement,” Organization & Environment, Vol. 19, No 1, 2006, pp. 103-109. doi:10.1177/1086026605285588 [40] B. Agarwal, “Gender and Forest Conservation: The Im- pact Of Women’s Participation In Community Forest Governance,” Ecological Economics, Vol. 68, No. 11, 2009, pp. 2785-2799. doi:10.1016/J.Ecolecon.2009.04.025 [41] N. Mukherjee, “Reflections on Gender Training for Gov- ernment Officials in India,” Proceedings of Iied/Ids Workshop on Pra and Gender, Brighton, December 1993. [42] C. Skanavis and M. Sakellari, “Gender and Sustainable Tourism: Women’s Participation In The Environmental Decision-Making Process,” European Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2008, pp. 78-93. [43] I. Von Frantzius, “World Summit on Sustainable Devel- opment Johannesburg 2002: A Critical Analysis And As- sessment Of The Outcomes,” Environmental Politics, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2004, pp. 467-473. doi:10.1080/09644010410001689214

|