Natural Resources, 2011, 2, 130-139 doi:10.4236/nr.2011.22018 Published Online 6 2011 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/nr) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? Thokozani Simelane Centre for African Ecology, Nelson Mandela University and South African National Parks, Port Elizabeth, South Africa E-mail: tsimelane@ai.org.za Received April 13th, 2011; revised May 9th, 2011; accepted May 18th, 2011. ABSTRACT A perception that there is a proportional relationship between the size of a conservation area and the occurrence or abundance of resources available was tested in this paper. This was done by evaluating the occurrence (from records of plant and animal species) of traditionally used biological resources from four national parks of South Africa that have different sizes. Results o btained show tha t contrary to a general be lief that bigger con s ervation areas migh t have higher proportions and possibly abundance of traditionally used resources, this is not true. In addition, results reflected that the occurrence of traditionally used biological resources within the conservation areas is not a function (in terms of the size) of their sizes. Drawing this relationship has put forth a question of whether there is a direct relationship between the biodiversity of conservation estates and the resources available. While this study did not attempt to provide an ab- solute answer to this question, it has laid a fou ndatio n to tackle it fu rth er. Prov iding answers to questions like these will not only increase the eco logical value of conserva tion areas among traditional societies b ut will also help to a lign con- servation estates with TRIPS (trade related aspects of intellectual property) and other international instruments like CBD (Convention on biodiversity). All which call for inclusive approach to the management of natural resources and biodiversity. Keywords: Conservation, Traditionally Used Resources, Conservation Areas, National Parks, Biodiversity 1. Introduction In addition to their primary functions of conserving biodiversity and fragile ecosystems, conservation areas are known to promote the protection of different species of plants and animals that are used as traditional resources (e.g. traditional medicines). These are referred to as tradi- tionally use biological resources [1-3]. To date more than 3000 plant species are known to be used as traditional medicines. These include not less than 350 species that are freely traded on streets and herbalists’ shops [3,4]. Approximately 20 000 tons of these plants species are harvested annually for trading as traditional medicines [5,6]. Trading with these plants provides income for some communities [5,7] and it is estimated that not less than $ 90 million is generated annually [7-11]. Considering the conservation statuses of most of these plant species [12], their presence in conservation areas demonstrates a critical role that is played by conservation areas in conserving and preserving a component of bio- diversity that is used as traditional resources. Their exis- tence within conservation areas can further be considered as representing a portion of biodiversity that is better un- derstood and recognized by traditional societies [13,14]. As the case with plant species, more than 280 verte- brates species are known to be used and sold for tradi- tional and cultural purposes [15]. These include 171 mammals, 58 birds, 31 reptiles and various marine organ- isms [15]. A larger proportion of these species, some with critical conservation status (e.g. Panthera pardus and Eri- naceus frontalis), are also freely available for sale in street markets and herbalists’ shops [15]. This happens in spite of heightened efforts by conservation agencies to con- serve them. Of all animal groups that are traded in the markets, mammals constitute the highest proportion (about 61%), with more than 150 species being found in herbalist shops [16,17]. Of critical note is that thirty one percent of these species are listed in Red Data Books [8,18-20]. The gen- eral tendency is that species with critical conservation status are in high demand and are thus highly priced [21,22]. This could be one of the causes of the reduction (in numbers) of these species outside conservation areas  Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? 131 [17,23,24,]. In this context, the role of conservation areas in protecting these species is quite critical. With addi- tional effects of climate change, habitat destruction, hunting [25], road kills, illegal poaching, poisoning and deaths through natural diseases, it is obvious that the fu- ture existence, outside conservation areas, of most ani- mals that are used as traditional resources cannot be guaranteed [23,26,27]. As numbers of traditionally used resources continue to decline outside conservation areas, there is a growing perception that these resources are in abundant within the borders of conservation areas. This perception is some- how a major cause for conflict between conservation au- thorities and communities around conservation areas, who demand access to these resources. In addition to this, there also exist a perception that larger conservation areas are rich in traditionally used resources, both in terms of diversity and abundance. In the existence of this perception, this analysis was con- ducted with the aim of determining the availability of these resources in relation to the size and biodiversity of the parks. The study analyzed four national parks of South Africa (i.e. Addo Elephant National Park (AENP), Golden Gate Highlands National Park (GGHNP), Moun- tain Zebra National Park (MZNP) and Karoo National Park (KRNP)). In the face of changing conservation phi- losophies and the stance of conservation authorities on biodiversity and its management through community support [12], the presence of traditionally used biological resources within conservation areas represent a buffer between western based conservation approaches and tra- ditional methods of managing and conserving biodiver- sity [28,29]. This analysis considered that highlighting the role of conservation areas in protecting a component of biodiversity that is used as traditional resources could increase the awareness of the importance of conserving of biodiversity by users of these resources and thus enhance the value of conservation of biodiversity among all com- munities. The study tested the hypotheses that: a) conservation areas are rich in plant and animal spe- cies used as traditional resources, b) these resources are a function of the number of spe- cies available in a conservation areas, c) their presence within the conservation area differ in the proportion of plant and animal species available, d) they tend to have critical conservation statuses and e) their proportions within conservation areas vary between taxa and the size of the conservation area. Many years ago, Siegfried [30] made a significant comment on the lack of reliable comprehensive biodiver- sity records and analysis for conservation areas. Since this comment, considerable efforts were made to address this issue, particularly for national parks. This resulted into a number of publications and establishment of data bases on records of plants (especially within the national parks of South Africa) (KSANP Data Base 1985-1998; van Wyk [31], Du Preez & Bezuidenhout [32], Pond [33], Botha [34] available within conservation areas. With a combined impetus of these efforts and investments made on determining values of biodiversity to human develop- ment, additional importance and meaning of biodiversity to various communities (including traditional societies) have also been determined and defining biodiversity through values provided by all societies (inclusive of tra- ditional societies) has become critical. 2. Research Methods Existing records such as Liversidge [35], Roberts [36], Bates [37], Earlė & Lawson [38], Bezuidenhout [39,40], Johnson [41], Williams [42] and checklists such as van Wyk [31], Zietsman [43] as well as unpublished data of plants (KSANP1 Data Base 1985-1998) and animals Knight & Hall-Martin [44], Castley & Knight [45] that occur within four national parks of South Africa (AENP, MZNP, KRNP and GGHNP) were used in this study, to compile lists of traditionally used plant and animal spe- cies available. In addition data bases such as PRECIS, SARARES and MEDBASE were inspected for additional information (http://www.nbi.ac.za/information/databases. htm) on traditional uses of various species. Additional information about traditional and cultural uses of identi- fied species was obtained from the published literature [1,34,46-55] traditional healers, street vendors and com- munities around the studied national parks. In determin- ing the possible impacts of traditional uses of identified plants and animals species conservation statuses of iden- tified species were determined using the Red Data Books: Smithers [18] for mammals, Branch [56] for reptiles, Hil- ton-Taylor [57] for plants and Barnes [58] for birds. 2.1. Statistical Analyses The number of plant and animal species recorded in each park was correlated to the number of available tradition- ally used plant and animal species, through a Spearman’s correlation analysis [59]. This tested the hypothesis that traditionally used resources available in a park could be the function of the number of species available and size of the park; thereby investigating the possibility that more diverse conservation areas may have higher proportions of traditionally used resources. The differences in the availability of traditionally used resources between the parks were compared statistically through a Chi-squared (2 ) analysis [59]. This tested the hypothesis that parks differ in the proportions of plant and 1 Kimberley South African National Parks Herbarium C opyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR 132 animal species used as traditional resources. Differences in the proportions of plant and animal species used as traditional resources in each park and the proportions of plant and animal species not used were again compared statistically, using a Chi-squared analysis. Differences between the used and threatened proportions of plant and animal species (as indicated by being listed in Red Data Books) and those listed but not used were also compared statistically using a Chi-Squared analysis [59]. This tested the hypothesis that plants and animals used as traditional resources tend to have threatened conservation statuses. In addition, differences between the taxa of vertebrate species recorded as used for different traditional purposes were compared using a Chi-squared analysis. This tested the hypothesis that proportions of species used as tradi- tional resources in conservation areas vary between the taxa. 3. Results 3.1. Plant Species Used as Traditional Resources A total of 1463 plant species were recorded as occurring within the four studied national parks. Six hundred and twenty five of these species (42.7%) occurred in AENP, 479 (32.7%) in MZNP, 124 (8.5%) in GGHNP and 235 (16.1%) in KRNP (Table 1). One hundred and seventy three of these species (9.5%) were found to be used for different traditional purposes, with MZNP (30%) having higher proportions of traditionally used plant species than the three other parks (AENP, GGHNP and KRNP) (Ta- ble 1). The occurrence of traditionally-used plant species (in the parks) was positively correlated (r = 0.43, df = 4, p < 0.05) to the total number of species available within each park. Eighty five percent (124) of the identified traditional resource plant species were mainly used as traditional medicines and 17% for non-medicinal uses. The non- medicinal uses included food (17 species), tools (10 spe- cies) and building material (7 species). Fruits and berries of some species were identified as being eaten, with some being particularly important as a dietary supplement dur- ing times of famine. Roots, bulbs and tubers served as starch supplements and leaves of certain species (mostly herbs) as vegetables. Parts targeted for medicinal uses varied and ranged from the whole plant (for herbs and geophytes) to roots, leaves and fruits. While the chemical content of the plant species is con- sidered to be the main determinant of most species used in traditional medicine [60], the use of other species e- merged to be largely due to their association with tradi- tional beliefs. Of note Celtis africana, whose wood is believed to provide protection against the bad intentions of sorcerers, Kigelia africana, whose fruit if hung in the hut is believed to provide protection against whirlwinds and Halleria lucida, which is believed to provide protec- tion against evil spirits. Although the recorded traditionally used plant species are largely harvested for sale or used by individual tradi- tional healers, five of these (Table 2) were found to be already commercially exploited with Pelargonium si- doides and Harpagophytum procumbens considered to have potential for international commercialization [3]. In this regard, Harpagophytum procumbens is regarded as a medicinal plant of international importance that is being successfully propagated on a limited commercial scale [3]. Only four (2.2%) of the recorded traditionally used plant species were listed in Red Data Book [57]; as rare (Crassula arborescens), vulnerable (Kniphofia rooperi) and not threatened (Cotyledon orbiculata, Nemesia fruti- cans). Three of these species are also listed as endemic (i.e. Kniphofia rooperi, Cotyledon orbiculata and Cras- sula arborescens) to South Africa. Listed species oc- Table 1. Number of plant species identified as used for traditional purposes (AENP = Addo Ele phant National Park, MZNP = Mountain Zebra National Park, GGHNP = Golden Gate Highlands National Park, KRNP = Karroo National Park). Plant species recorded in the park Plant species identified as used for traditional purposes Species used Species not used Park Families Species % representation of plant species recorded in SA Families n % n % AENP 73 625 2.7% 27 43 6.8 582 93.2 MZNP 82 479 2.1% 30 53 11.0 426 89.0 GGHNP 46 124 0.5% 26 37 29.8 87 70.2 KRNP 56 235 1.0% 27 23 9.8 212 90.2 Total 322 1785 7.8% 143 211 14.9 1574 85.1  Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? 133 Table 2. Commercially Exploited Traditionally Used Plants (AENP = Addo Elephant National Park, MZNP = Moun- tain Zebra National Park). Family Common and species names Park where it occurs Use Asteraceae Chicory (Cichorium intybus). AENP Roots are processed into a com- mercial product known as chic- ory, which is sold as a coffee additive or coffee substitute. The root has tonic, sedative an mild laxative activities (van Wyk, Oudtshoorn & Gericke 1997). Sapindaceae Jacket plum (Pappea cap- ensis) AENP Fruit used for jelly and edible seed oil used to make soap (van Wyk, Oudtshoorn & Gericke 1997). Aspho- delaceae Bitter aloe Aloe ferox AENP and MZNP Leaf exudates used as laxative medicine. Also used in self-care remedies such as “lewenses- sens”, and “Schweden bitters” (van Wyk, Oudtshoorn & Ge- ricke 1996 . Geraniaceae Rabas (Pelar- gonium si- doides AENP Used as an ingredient fo “Umckaloabo”, a German me- dicinal remedy used to trea bronchitis in children (van Wyk, Oudtshoorn & Gericke 1997). curred in AENP (Crassula arborescens), KRNP (Coty- ledon orbiculata) and MZNP (Kniphofia rooperi). One of the endemic, rare species (Crassula arborescens) is listed as internationally threatened. There were signifi- cantly fewer (2 = 0.83, df = 4, p < 0.05) used listed species than the listed, not-used species. There was no statistically significant (2 = 5, df = 4, p > 0.05) differ- ence between the parks with regard to the occurrence of the threatened, used species. However, GGHNP recorded a comparatively high proportion (2.3%) of listed, not-used species (Table 3). 3.2. Animal Species Used as Traditional Re- sources One hundred and twelve species of vertebrates that oc- curred within the studied national parks were identified as being used for different traditional and cultural purposes (Table 4). The traditional uses of the identified vertebrate species included meat for consumption, traditional attire, decoration of traditional healer’s consulting rooms and traditional medicines. Species used in traditional medi- cines either served as ingredients additional to medicinal plants or were used without being mixed. Mammals (60 species) had the highest proportion (53.6%) of species used, followed by birds (27 species (24%)) and reptiles (23 species (20.5%)). While birds and mammals were used for various traditional purposes that include meat, attire and treating different illnesses, the highest propor- tion (67%) of reptiles was specifically used for traditional medicinal purposes. As in the case of the plant species, some animal species were associated with traditional beliefs. Notable among these were bird species such as ground hornbill (Bucorvus leadbeateri), which is believed to possess powers of causing a thunderstorm and the hamerkop (Scopus um- bretta), which was widely associated with witchcraft, and all species of owls, which were regarded as the birds of ill omen and witchcraft. Unlike plant species, which were used for diseases that Table 3. Total numbers of traditionally used plant spe c i es from four studied national parks. Plant species not used Plant species used Parks Total number of species occurring in the park Number of species not used but listed in SA red data book Number of species not used and not listed in red data book Number of species used Number of species used and listed in SA red data book Number of species used but not listed in SA red data book AENP 625 5 (0.85%) 577 (92.3%) 43 1 (0.2%) 42 (24.3%) MZNP 479 8 (1.9%) 471 (98.3%) 53 1 (0.2%) 52 (30.0%) GGHNP 124 2 (2.32%) 122 (98.4%) 37 0 (0.0%) 37 (22%) KRNP 235 3 (1.4%) 232 (98.0%) 23 1 (0.5%) 22 (12.3%) Total 1785 22 1720 211 4 211 The table also shows total numbers of species listed in South Africa’s red data books (following Hilton-Taylor 1996). Numbers in brackets reflect the percent- ages of listed species in each park. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? 134 Table 4. Vertebrate species from the four analyzed National Parks, which were identified as used in traditional cultural prac- tices and medicinal purposes. Park Taxon Total No of species recorded in the park % Representation of the total number of species known to occur in South Africa No of species used for traditional and cultural purposes (with % of total species in the park) No of species not used (with % of total species in the park) 2 value for test- ing the difference between used and not used species P < 0.001 Mammals 92 37.2 31 (33.7%) 61 (66.3%) Birds 318 41.0 18 (5.7%) 300 (94.3%) Reptiles 49 16.4 8 (16.3%) 41 (83.7%) 26.4** AENP Total 459 57 402 Mammals 79 32.0 36 (45.6%) 43 (55.4%) Birds 265 34.2 19 (7.2%) 246 (92.8%) Reptiles 53 17.7 20 (37.7%) 33 (62.3%) 38.6** MZNP Total 397 75 322 Mammals 79 32.0 36 (45.6%) 43 (55.4%) Birds 255 33.0 15 (5.9%) 240 (94.1%) Reptiles 35 11.7 3 (8.6%) 32 (91.4%) 60.5** GGHNP Total 369 54 315 Mammals 77 31.2 36 (46.8%) 41 (53.2%) Birds 226 29.2 15 (6.6%) 211 (93.4%) Reptiles 67 22.4 19 (28.4%) 48 (71.6%) 40.8** KRNP Total 370 70 300 are well defined in scientific terms, animal species were also used in traditional medicines for disease and illnesses that are difficult to define. Some of these illnesses include izitshopi, imeqo, ukwethuka and inyoni, which are exten- sively described by Ngubane [54] as being caused by stepping over the tracks of certain animal species (snakes) or through spells cast by witchdoctors using some animal species (owls) as their agents. The use of animals to cure these illnesses reflects the general interpretation of the causes of illnesses by traditional healers. This perception normally determines the inclusion of animal species in potions used to cure the perceived illness and does not rely on a pharmacological action. Twenty (18%) traditionally-used vertebrate species are considered threatened [18,56,58]. These include 14 (70%) mammals (listed as rare (6), indeterminate (2), endan- gered (2), not designated (1) and vulnerable (4, 28.5%)) and six birds (listed as rare (1), vulnerable (2) and re- quire monitoring (3)) (Table 5). In all parks, mammals comprised of a significantly (2 = 3.7, df = 3, p < 0.001) higher proportion of the listed used species (Table 5). 3.3. Relationship between Identified Resources and the Size of the Park While it was expected that the occurrence of traditionally used resources within the parks would be directly corre- lated to the size of the park (Table 6), the occurrence of these resources within the parks was found not to differ between the parks (2 = 168.0, df = 156, p > 0.05), in- dicating that all five studied parks had similar proportions of traditionally used resources. 4. Discussion What has emerged from this analysis is that while most earlier studies on traditional resources [1,34,42,49,60-62] Table 5. Conservation status of animal species recorded as used for different traditional purposes. Animal species used Animal species not Parks Taxon ThreatenedNot threat- ened Threatened Not threatened Mammals4 (15.4%)22 (84.6%) 10 (15.2%)56 (84.8%) Birds 3 (9.1%)19 (90.9%) 21 (7.1%)275 92.9% Reptiles0 (0.0%)18 (100%) 1 (3.2%)30 (96.8%) AENP Total 7 59 32 361 Mammals3 (8.3%)33 (91.7%) 7 (16.3%)36 (83.7%) Birds 3 (15.8%)16 (84.2%) 17 (6.9%)229 93.1% Reptiles0 (0.0%)21 (100%) 1 (3.2%)31 (96.8%) MZNP Total 6 70 25 296 Mammals5 (13.9%)31 (86.1%) 6 (14.0%)37 (86.0%) Birds 3 (15.0%)17 (85. 5%) 20 (8.5%)215 91.5% Reptiles0 (0.0%)13 (100%) 0 (0.0%)22 (100%) GGHNP Total 8 61 26 274 Mammals4 (11.4%)31 (88.6%) 6 (14.2%)36 (85.8%) Birds 2 (11.8%)15 (88.2%) 15 (7.2%)194 92.8% Reptiles0 (0.0%)15 (100%) 0 (0.0%)52 (100%) KRNP Total 6 61 21 282 Threatened conservation status indicated by being listed in the Red Data Books, Smithers [18] for mammals, Branch [19] for reptiles and Barnes [58] for birds. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? 135 concentrated on listing the presence of traditionally used plants or animals within conservation areas, investigating the occurrence of these resources in relation to their con- servation statuses and sizes of conservation areas should be considered and used as a new approach of defining the biological wealth of conservation areas. Contrary to a perception that conservation areas are rich in traditionally used biological resources [63], this analysis has demonstrated that the occurrence of these resources within the conservation areas is of limited ex- tent, with traditionally used plants being less well repre- sented than the traditionally used animals (Table 3 and 4). The analysis further demonstrated that the traditionally used species within conservation areas is a function of the number of species available within the conservation es- tates but not the size of the estate. Thus, conserved areas with large number of plants or animal species can be re- garded as having higher proportions of traditionally used biological resources but this may not be linked to the sizes of a conservation area. Through this study it also emerged that the numbers of traditionally used resources differ among the conservation areas. This heterogeneous occurrence of these resources within the conservation areas reflects that not all conservation areas can be re- garded as being rich in traditionally-used biological re- sources. This thus calls for the identification of conserva- tion areas that can be regarded as rich in traditionally- used resources. Similar studies on species abundance and endemism as well as biodiversity richness has helped to draw to the attention of conservation agencies, areas that require conservation priority and this has led to the map- ping and increased conservation efforts of biodiversity hotspots of the world [64-68]. The emergence of these facts draws to our attention a need to investigate if traditionally used resources are a function of the biodiversity of conservation areas. This requires the development of an index that will link the biodiversity of conservation areas with traditional re- sources present within the conservation estates. Such an index will be an important tool that can be used in as- sessing conservation areas according to traditional values, resources and perceptions provided by local communities. This is also of great significance as most conservation areas were solely established with the purpose of protect- ing plant or animal species identified to have critical con- servation statuses (Table 6). With the new view of as- sessing conservation areas according to attached tradi- tional values [13,67] and their contribution to biodiversity management can help bridge the gap that exists between current conservation objectives and expectations of the societies residing around the conservation areas [68]. Table 6. Park sizes, objectives and their resources (biodiversity). Park Name Size Park objectives Biodiversity AENP139 000ha The park was pro- claimed so as to con- serve a viable popula- tion of Addo Elephants (Loxodonta Africana), African buffalo (Synce- rus caffer) and black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis). The park hosts repre- sentatives of four of South Africa’s seven terrestrial biomes i.e. Nama karoo, Fynbos, forest and thicket. MZNP18 994ha The park was pro- claimed with the aim of saving the Cape Moun- tain Zebra (Equus zebra zebra) from extinction. Its additional aim is to preserve the karoo vegetation that is suit- able for the conserva- tion of Cape Mountain Zebras. The vegetation of the park is dominated by an abundance of grasses and dwarf shrubs-classified as the Eastern Mixed Karoo. GGHNP11 630ha The park was pro- claimed so as to con- serve a representative part of the spectacular Clarens Sandstone for- mation. It also aims to conserve the highland sourveld at the upper reaches of the catchment area of Klein Caledon River. The vegetation in the park can be divided into grassland and woodland/forest. Vir- tually, the entire park carries grassland vege- tation. KRNP69 624ha The park was pro- claimed so as to con- serve the Karoo flora and to protect a repre- sentative example of this vegetation against further degradation and exploitation. Variations in altitude have resulted to a park to have a distinct con- trast between the vegetation of upper and the lower plateau. The upper. Overall, the presence of traditional resources within the conservation areas provides various advantages for con- servation [13,68-70]. They provide opportunities for the extension of conservation awareness among communities [71]. They offer opportunities of implementing philoso- phies of community-based natural resource management [72]. Contrary to previous law enforcement management methods of managing these resources, participation of communities in managing traditionally used biological resources will improve the relationships between conser- vation authorities and communities [73] as cooperative management broadens the understanding of conservation objectives by communities and increases their under- standing of the role played by conservation areas in con- serving natural resources and biodiversity [74]. Although traditional used biological resources appear to occur in limited proportions within the conservation areas (Table 3 and 4), their abundance within conserva- C opyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? 136 tion areas is generally comparatively higher than neigh- bouring unprotected land [75]. This effect is particularly strongly developed for larger animals, which do not per- sist outside of conservation areas, such as elephant, leop- ard and lions [76]. Thus their presence within conserva- tion areas offers them protection. For instance, the occur- rence of some traditionally used plants that have critical conservation statuses within some parks reflected the significant role played by these parks in protecting threat- ened resources [69]. In spite of this, what can be said is that each conserved area supports the conservation of a distinctive proportion of traditionally-used plant and ani- mal species (Table 3 and 4), which may be threatened outside conservation areas not only by overexploitation but also by different forms of land use like development, agriculture or persecution due to beliefs or stigmas asso- ciated with them [22]. Of critical note is that while this analysis provides a broad picture about the occurrence of traditional re- sources within conservation areas and relates them to their conservation statuses, it does not estimate the abun- dance or dynamics of these resources within the conser- vation areas-important indicators of sustainability. This thus implies the necessity of supplementing this study with the investigation of the abundance and dynamics of the identified traditional resources within the national parks. Such studies should provide guidelines of harvest- ing traditionally used resources within the conservation areas. It must also provide strategies of forging collabora- tive management. Organizations like TRAFFIC have already started with collaborative management of traditionally used natural resources, working directly with the people whose liveli- hoods depend on these resources [27]. This has set the stage for partnerships between the conservation agencies and communities, where both parties strive to ensure the sustainable supplies of valued resources for the future generations [27]. Benefits of co-operative management of natural resources are manifold [77,78]. As conservation areas struggle to incorporate local communities into their management, participation of communities in designing control measures and policies of resources they associate with will increase self-sufficiency among communities and this will increase chances of developing the social support of conservation of biodiversity. Although most traditionally-used biological resources do not feature prominently in Red Data Books (Table 3 and 5), most of these resources are already threatened outside conservation areas [3,72] due to various threats that include over-harvesting and unsustainable forms of land use. This is obvious with traditionally used animals [8,24]. Animal species like the leopard, spotted genet and many other species used for traditional attire and medi- cine are now largely confined within the boundaries of the conservation areas [72]. Those that still occur outside conservation areas are limited in distribution and their future persistence is uncertain [18,79]. Therefore, this study reflects a need to re-assess the Red Data Book statuses of traditionally used species to increase their conservation efforts. In the meantime, conservation areas need to prioritize the conservation of all traditional re- sources, and improve their protection by developing ef- fective management programmes that will ensure their protection while developing relationships between con- servation areas and local communities. However, to sus- tain the collaborative management of these resources in conservation areas, there is a need to: 1) develop invento- ries of the available traditionally used biological re- sources within conservation areas and those that are available outside conservation areas that are used by communities; 2) educate communities about the contribu- tion of conservation areas towards the conservation of traditionally used biological resources and development opportunities associated with conservation of natural re- sources; 3) improve the participation of local communi- ties in the management of these resources through pro- jects that may enhance the communities’ conservation awareness and 4) devise strategies that would promote the sustainable harvesting of the required resources [80,81]. REFERENCES [1] J. M. Watt and M. G. Breyer-Brandwijk, “The Me- dicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and East- ern Africa,” Livingstone, London, 1962. [2] F. W. Fox and N. Young, “Food from the Veld,” Delta, Johannesburg, 1982. [3] B. Van Wyk, B. Oudsthoorn and N. Gericke, “Me- dicinal Plants of South Africa,” Briza publications, Pretoria, 1997. [4] A. B. Cunnigham, “Imithi Isizulu: The Traditional Medicine Trade in Kwazulu-Natal,” Master of So- cial Science dissertation, University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg, 1992. [5] R. Scott-Shaw, “A Directory of Medicinal Plants Trade in Natal with Zulu Names and Conservation Status,” Natal Parks Board internal Report, Natal Parks Board, 1990. [6] M. Mander, “Marketing of indigenous medicinal plants in South Africa: A case study in Kwa- zulu-Natal,” Rome-Food and Agriculture Organiza- tion of the United Nations, 1998. [7] L. V. Williams, “The Witwatersrand Muti Trade,” Veld & Flora, March 1996, pp. 12-14. [8] A. B. Cunningham, “An Investigation of the Herbal Medicine Trade in KwaZulu,” Investigational Re- C opyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? 137 port No.29, Institute of Natural Resources, Univer- sity of Natal, Pietermaritzburg, 1988. [9] A. B. Cunningham, “Income, Sap Yield and Effects of Sap Tapping on Palms in the South-Eastern Af- rica,” South African Journal of Botany, Vol. 56,No. 2, 1990, pp. 137-144. [10] A. B. Cunningham and A. S. Zondi, “Striped Wea- sel: Traditional Medicine and Conservation,” En- dangered Wildlife, Vol. 11, 1992, pp. 10-15. [11] S. A. McCartan and J. van Staden, “Micropropa- Gation of Members of the Hyacinthaceae with Me- dicinal and Ornamental Potential,” South African Journal of Botany, Vol. 65, No.5-6, 1999, pp. 361-369. [12] T. S. Simelane, “Role of Conservation Areas in Conserving Traditionally Used Natural Resources and Biodiversity,” Ph.D. thesis. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, 2005. [13] J. Botha, “Perceptions of Availability and Values of Medicinal Plants Traded in Areas Adjacent to the Kruger National Park,” MSc thesis dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 2001. [14] A. B. Cunningham, “Indigenous Plant Use: Bal- ancing Human Needs and Resources,” B. J. Huntley (ed.) “Biotic Diversity in Southern Africa: Concepts and Conservation,” Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1989. [15] T. S. Simelane, “The Traditional Use of Indigenous Vertebrates,” MSc Dissertation, University of Port Elizabeth, Port Elizabeth, 1996. [16] A. B. Cunningham and A. S. Zondi, “Use of Ani- mal Plants for Commercial Trade in Traditional Medicine,” Institute of Natural Resources, Report 76, 1991, pp. 1-40. [17] T. S. Simelane and G. I. H. Kerley, “The Conserva- tion Implications of the Use of Indigenous Verte- brates by Traditional Healers: With Reference to Xhosa Traditional Healers,” South African Journal of Wildlife Research, Vol. 28, 1998, pp. 121-126. [18] R. H. N. Smithers, “South African Red Data Book-Terrestrial Mammals,” South African Na- tional Scientific Programme Report No.125, FRD & CSIR, Pretoria, 1986. [19] W. R. Branch, “South African Red Data Book: Reptiles and amphibians,” South African Scientific programme, Report 151, 1988, pp. 1-24. [20] J. Hilton-Taylor, E. T. F. Witkowski and C. M. Shackleton, “An inventory of medical plants traded on the western boundary of the Kruger National Park, South Africa,” Koedoe, Vol. 44, No. 2, 2001, pp. 7-46. [21] A. B. Cunningham and A. S. Zondi, “Striped Wea- sel: Traditional Medicine and Conservation,’ En- dangered Wildlife, Vol. 11, 1992, pp. 10-15. [22] T. S. Simelane and G. I. H. Kerley, “Recognition of Reptiles by Xhosa and Zulu Communities in South Africa, With Notes on Traditional Beliefs and Uses,”African Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 41, 1997, pp. 49-53. doi:10.1080 /21564574 .1997.96499 75 [23] J. G. Castley and G. I. H. Kerley, “The Paradox of Forest Conservation in South Africa,” Forest Ecol- ogy and Management, Vol. 85, 1996, pp. 35-46. doi:10.1016 /S0378-112 7(96)03748 -6 [24] C. Fabricius and M. Burger, “Comparison between a nature reserve and adjacent communal land in Xeric Succulent Thicket – an Indigenous Plant User’s Perspective,” South African Journal of Sci- ence, Vol. 93, 1997, pp. 259-262. [25] C. A. Peres, “Effects of Hunting on Western Ama- zonian Primate Communities,” Biological Conser- vation, Vol. 5, 1990, pp. 47-59. doi:10.1016 /0006-3207 (90)90041- M [26] E. Bowen-Jones and S. Pendry, “The Treat of Pri- mates and Other Mammals from the Bushmeat Trade in Africa, and How this Threat could be Di- minished,” Oryx, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1999, pp. 233-246. [27] A. Rosser, N. Ash and M. Sorola, “Approaches to the conservation of species used in traditional medicines,” South African Journal of Medicine, Vol. 48, 2000, pp. 1688-1690. [28] F. Berkes, J. Colding and C. Folke, “Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management,” Ecological Applications, Vol. 10, No. 5, 2000, pp. 1251-1262. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2 [29] M. Richards, “Protected Areas, People and Incen- tives in Search for Sustainable Forest Conservation in Honduras,” Economic Conservation Vol. 23, No. 3, 1996, pp. 207-217. [30] W. R. Siegfried, “Preservation of Species in South- ern African Nature Reserves,” B. J. Huntley, “Bi- otic Diversity in Southern Africa-concepts and Conservation,” Oxford University Press, New York. 1989. [31] B. E. Van Wyk, C. M. Van Wyk and P. Novellie, “Flora of the Zuurberg National Park. An anno- tated Checklist of Ferns and Seed Plants,” Bothalia, Vol. 18, 1988, pp. 221-232. [32] D. Tilman, “Biodiversity: Population versus eco- system stability,” Ecology, Vol. 77, No. 2, 1996, pp. 350-363. doi:10.2 307/2265614 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? 138 [33] U. Pond, B. B. Beesley, L R. Brown and H. Be- zuidenhout, “Floristic Analysis of the Zebra Na- tional Park, Eastern Cape,” Koedoe, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2002, pp. 335-357. [34] J. Botha, E. T. F Witkowski and C. M. Shackleton, “An inventory of medical plants traded on the west- ern boundary of the Kruger National Park, South Africa,” Koedoe, Vol. 44, No. 2, 2001, pp. 7-46. [35] R. Liversidge, “The Birds of the Addo Elephant National Park,” Koedoe, Vol. 8, 1965, pp. 41-67. [36] B. R. Roberts, “The Vegetation of the Golden Gate Highlands National Park,” Koe d oe, Vol. 12, 1969, pp. 15-28. [37] M. F. Bates, “A Provisional Checklist of Reptiles and Amphibians of the Golden Gate Highlands Na- tional Park,” Koedoe, Vol. 34, No. 2, 1991, pp. 153-155. [38] K. A. Earlè and A. B. Lawson, “An Annotated Checklist of the Birds of The Golden Gate High- lands National Park,” Koedoe, Vol. 31, 1988, pp. 227-244. [39] H. Bezuidenhout, “An Ecological Study of the Ma- jor Vegetation of the Vaalbos National Park, North- ern Cape – The Than Droogeveld section,” Koedoe, Vol. 37, No. 2, 1994. pp. 19-41. [40] H. Bezuidenhout, “An Ecological Study of the Ma- jor Vegetation of the Vaalbos National Park North- ern Cape – The Than Graspan-Holpan section,” Koedoe, Vol. 338, No. 2, 1995, pp. 65-83. [41] C. F. Johnson, R. M. Cowling and P. B. Phillipson, “The Flora of the Addo National Park, South Africa: Are Threatened Species Vulnerable to Elephant Management,” Biodiversity and Conservation, Vol. 8, 1999, pp. 1447-1456. doi:10.1023 /A:1008980120 379 [42] V. L. Williams, K. Balkwill and E. T. F. Witkowski, “A Lexicon of Plants Traded on the Witwatersrand Umuthi Shops, South Africa,” Bothalia, Vol. 31, 2001, pp. 71-98. [43] P. C. Zietsman, P. J. du Preez and H. Bezuidenhout, “A Preliminary Checklist of Flowering Plants of the Vaalbos National Park,” Koedoe, Vol. 42, No. 2, 1992, pp. 95-112. [44] M. H. Knight and A. J. Hall-Martin, “Helicopter Surveys of the Addo Elephant Park,” Internal Re- port, South African National Parks, Kimberley, March-May 1994. [45] J. G. Castley and M. H. Knight, “Helicopter Based Survey of Addo Elephant National Park,” Unpub- lished Internal Report, South African National Parks, Kimberley, February 1998. [46] F. W. Fox and N. Young, “Food from the Veld,” Delta, Johannesburg, 1982. [47] E. Palmer and N. Pitman, “Trees of Southern Af- rica,” Vol. 1, Balkema, Cape Town, 1972. [48] A. Hutchings, A. H. Scott, G. Lewis and A. Cun- ningham, “Zulu Medicine Plants – An Inventory,” University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg, 1996. [49] F. Venter and J. Venter, “Making the Most of In- digenous Trees,” Briza publication, Pretoria, 1996. [50] B. Van Wyk and N. Gericke, “People’s Plants– A Guide to Useful Plants of Southern Africa,” Briza publications, Pretoria, 1999. [51] A. B. Cunningham and A. S.Zondi, “Use of Animal Plants for Commercial Trade in Traditional Medi- cine,” Institute of Natural Resources, Rep. 76, pp. 1991, 1-40. [52] A. B. Cunningham and A. S. Zondi, “Striped Wea- sel: Traditional Medicine and Conservation,” En- dangered Wildlife, Vol.11, 1992, pp. 10-15. [53] J. Bryom, “Field guide to the Game of the Natal and Zululand,” Sealandair, Durban, 1977. [54] H. Ngubane, “Body and Mind in Zulu medicine: An Ethnology of Health and Diseases in Nyuswa-Zulu Thought and Practice,” Academic Press, London, 1977. [55] T. S. Simelane, “The Traditional Use of Indigenous Vertebrates,” MSc dissertation, University of Port Elizabeth, Port Elizabeth, 1996. [56] W. R. Branch, “South African Red Data Book: Rep- tiles and amphibians,” South African Scientific pro- gramme, Report 151, 1988, pp. 1-24. [57] C. Hilton-Taylor; O. A. Leistner and B. A. Mom- berg, “Red Data List of Southern African Plants (Strelitzia),” National Botanical Institute, 1996. [58] K. N. Barnes, “The Eskom Red Data Book of Birds in South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland,” Birdlife South Africa, Johannesburg, 2000. [59] J. H. Zar, “Biostatistical Analysis,” 2nd edition, Pentice Hall, New Jersey, 1984. [60] J. O. Kokwaro, “Medical Plants of East Africa,” East African Literature Bureau, Nairobi, 1983. [61] A. T. Bryant, “Zulu Medicine and Medicine-Men,” C. Struik, Cape Town, 1966. [62] B. Akendengue, “Medical Plants Used by Fang Tra- ditional Healers in Equatorial Guinea,” Journal of Ethnopharmacolog , Vol. 37, 1992, pp. 165-173. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(92)90075-3 [63] O. L. B. Phillips and A. H. Gentry, “The Useful Plants of Tambota, Peru I: Statistical Hypothesis C opyright © 2011 SciRes. NR  Are Traditionally Used Resources within Conservation Areas a Function of Their Sizes? Copyright © 2011 SciRes. NR 139 Tests with a New Quantitative Technique,” Eco- nomic Botany , Vol. 47, 1993, pp. 15-32. doi:10.1007/BF02862203 [64] H. N. Balyamujura and H. G. van Schalkwyk, “Na- ture Conservation Versus Human Needs: The Case of Manyeleti Game Reserve,” Agrekon, Vol. 38, 1999, pp. 861-873. doi:10.1080/03031853.1999.9524895 [65] C. M. Shackleton, “Demography and Dynamics of Dominant Woody Species in a Communal and Pro- tected Area of the Transvaal Lowveld,” South Afri- can Journal of Bot any , Vol. 59, 1993, pp. 569-574. [66] D. W. Schemske, B. C. Husband, M. H. Ruckel- shans, C. Goodwill, I. N. Parker and J. G. Bishop, “Evaluating Approaches to the Conservation of Rare and Endangered Plants,” Ecology, Vol. 75, 1994, pp. 584-606. doi:10.2307/19417 18 [67] V. H. Heywood, “Global Biodiversity Assessment,” Cambridge University Press, New York, 1995. [68] C. M. Shackleton, “Comparison of the Plant Diver- sity in Protected and Communal Lands in the Bushbuckridge Lowveld Savanna, South Africa,” Biological Conservation, Vol. 94, 2000, pp. 273-280. do i:10.1016/S000 6-3207(00)0 0001-X [69] T. M. Caro, “Species Richness and Abundance of Small Mammal inside and Outside African National Park,” Biological Conservation, Vol. 98, 2001, pp. 251-257. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00105-1 [70] H. Else and J. du P. Bothma, “Developing Partner- ships in a Paradigm to Achieve Conservation Real- ity in South Africa,” Koedoe, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2000, pp. 19-26. [71] B. M. Sibanda and A. K. Omwega, “Some reflec- tions on conservation, sustainable development and equitable sharing of benefits from wildlife in Africa: the case of Kenya and Zimbabwe,” South African Wildlife Research, Vol. 26, No. 4, 1996, pp. 175-181. [72] C. Quiroz, “Indigenous Knowledge and Develop- ment,” Mon ito r , Vol. 6, No. 2, 1998, pp. 1-3. [73] G. D. La Cock and J. H. Briers, “Bark Collecting at Tootabie Nature Reserve, Eastern Cape, South Af- rica,” South African Journal of Botany, Vol. 58, 1992, pp. 505-509. [74] A. B. Cunningham, “People, park and plant use. Recommendations for Multiple Use Zones and De- velopment, Alternatives around Bwindi Impenetra- ble National Park of Uganda,” People & Plants working paper 4, UNESCO, Paris, 1996. [75] J. A. Richardson, “Wildlife Utilization and Biodi- versity Conservation in Namibia: Conflicting Objec- tives?” Biodiversity and Conservation, Vol. 7, 1998, pp. 549-559. doi:10.1023/A:1008883813644 [76] J. H. Haynes, “Involving Communities in Managing Protected Areas: Contrasting Initiatives in Nepal and Britain,” Parks, Vol. 8, 1998, pp. 54-61. [77] C. Fabricius and M. Burger, “Comparison between a Nature Reserve and Adjacent Communal Land in Xeric Succulent Thicket – An Indigenous Plant User’s Perspective,” South African Journal of Sci- ence, Vol. 93, 1997, pp. 259-262. [78] G. I. H. Kerley, R. L. P. Pressey, R. M. Cowling, A. F. Boshoff and R. Simms-Castley, “Options for the Conservation of the Large and Medium-Sized Mammals in the Cape Floristic Hotspot, South Af- rica,” Biological Conservation, Vol. 112, 2002, pp. 196-190. [79] B. M. Sibanda and A. K. Omwega, “Some Reflec- tions on Conservation, Sustainable Development And Equitable Sharing of Benefits from Wildlife in Africa: The Case of Kenya And Zimbabwe,” South African Wildlife Research, Vol. 26, No. 4, 1996, pp. 175-181. [80] D. Hanekom and L. Liebenberg, “Utilization of Na- tional Parks With Special Reference to the Costs and Benefits to Communities,” Bulletin of Grassland Society of Sout h Afri ca, Vol. 5, 1994, pp. 25-36. [81] M. Richards, “Protected Areas, People and Incen- tives in Search for Sustainable Forest Conservation in Honduras,” Economic Conservation , Vol. 23, No. 3, 1996, pp. 207-217.

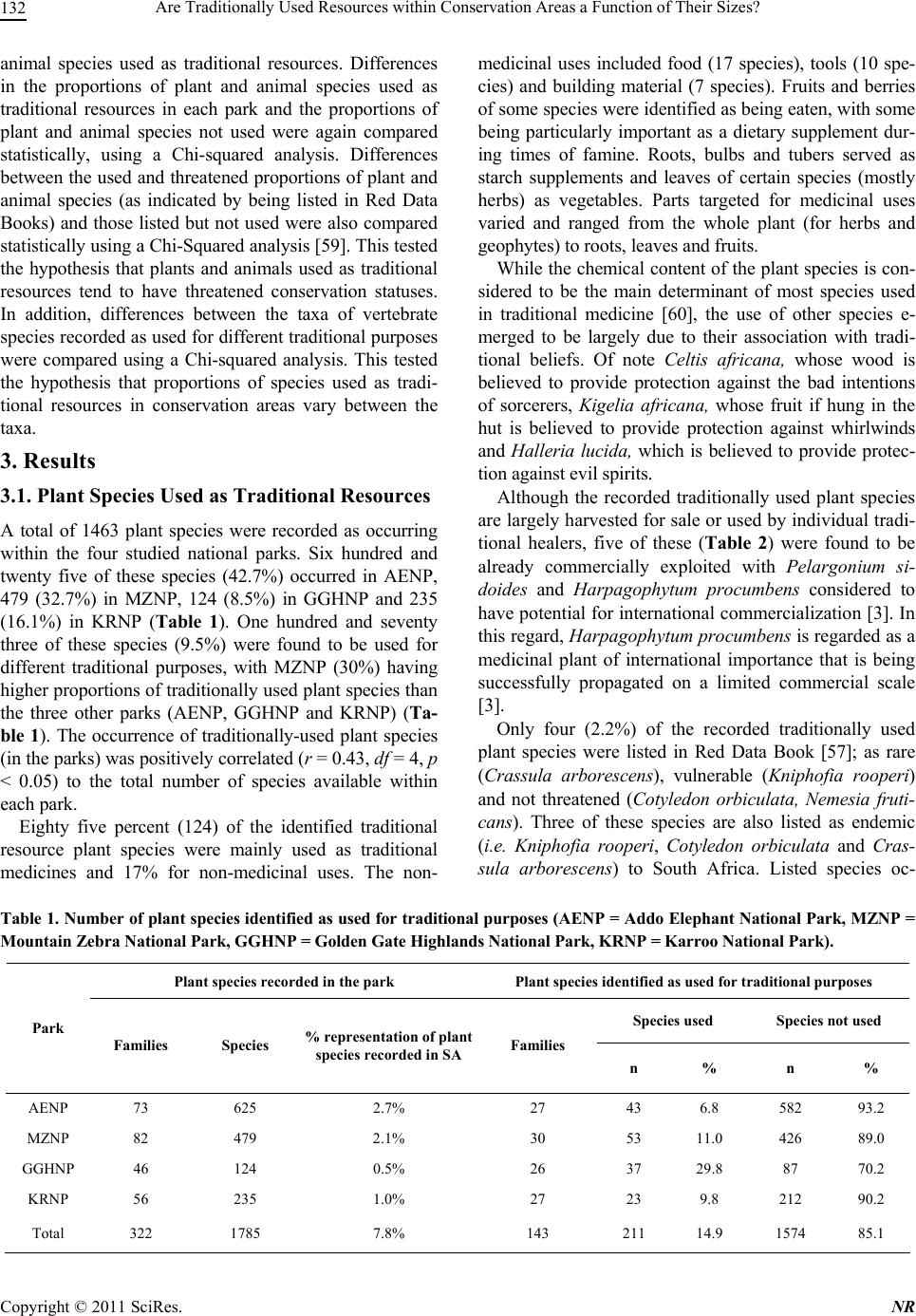

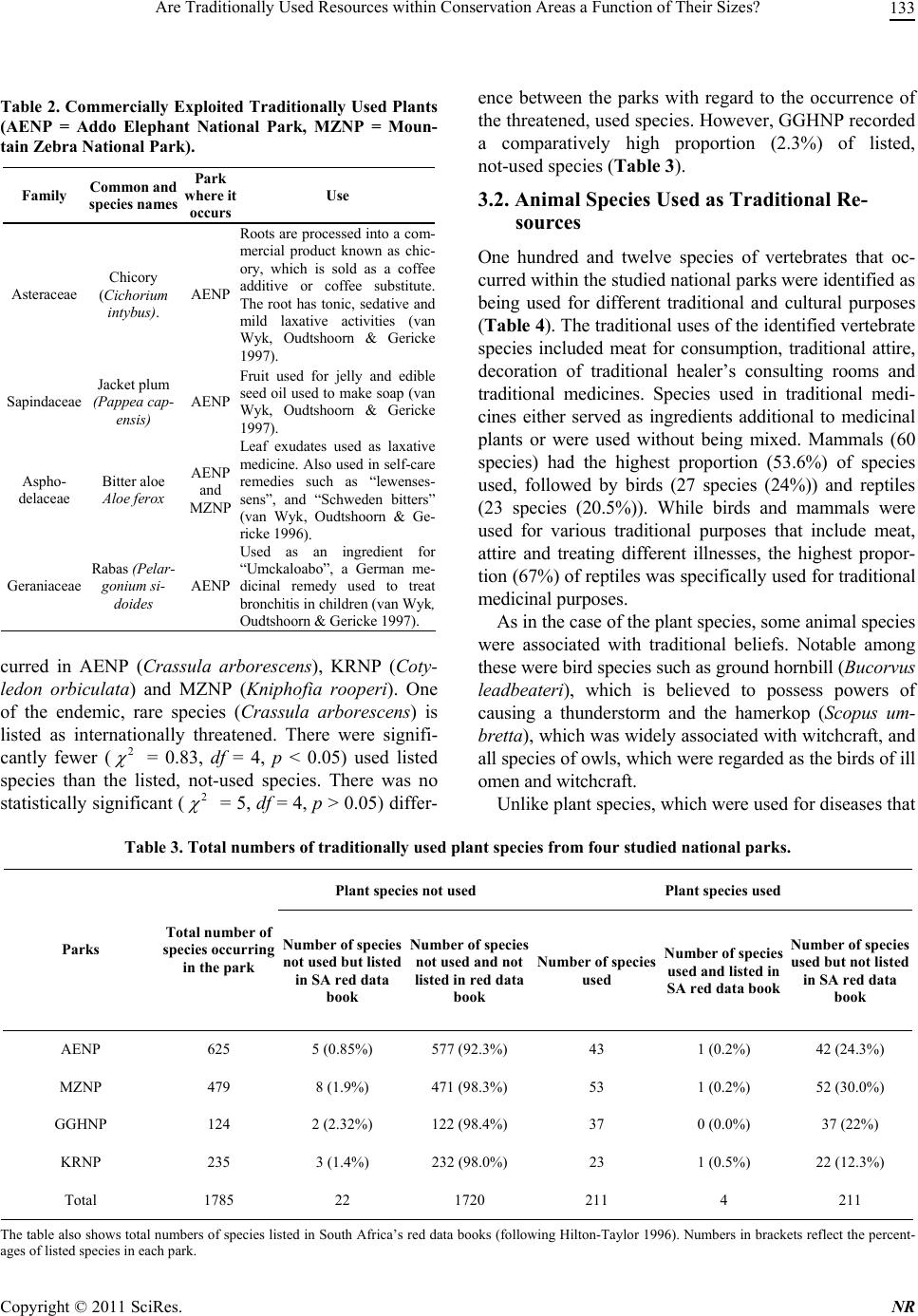

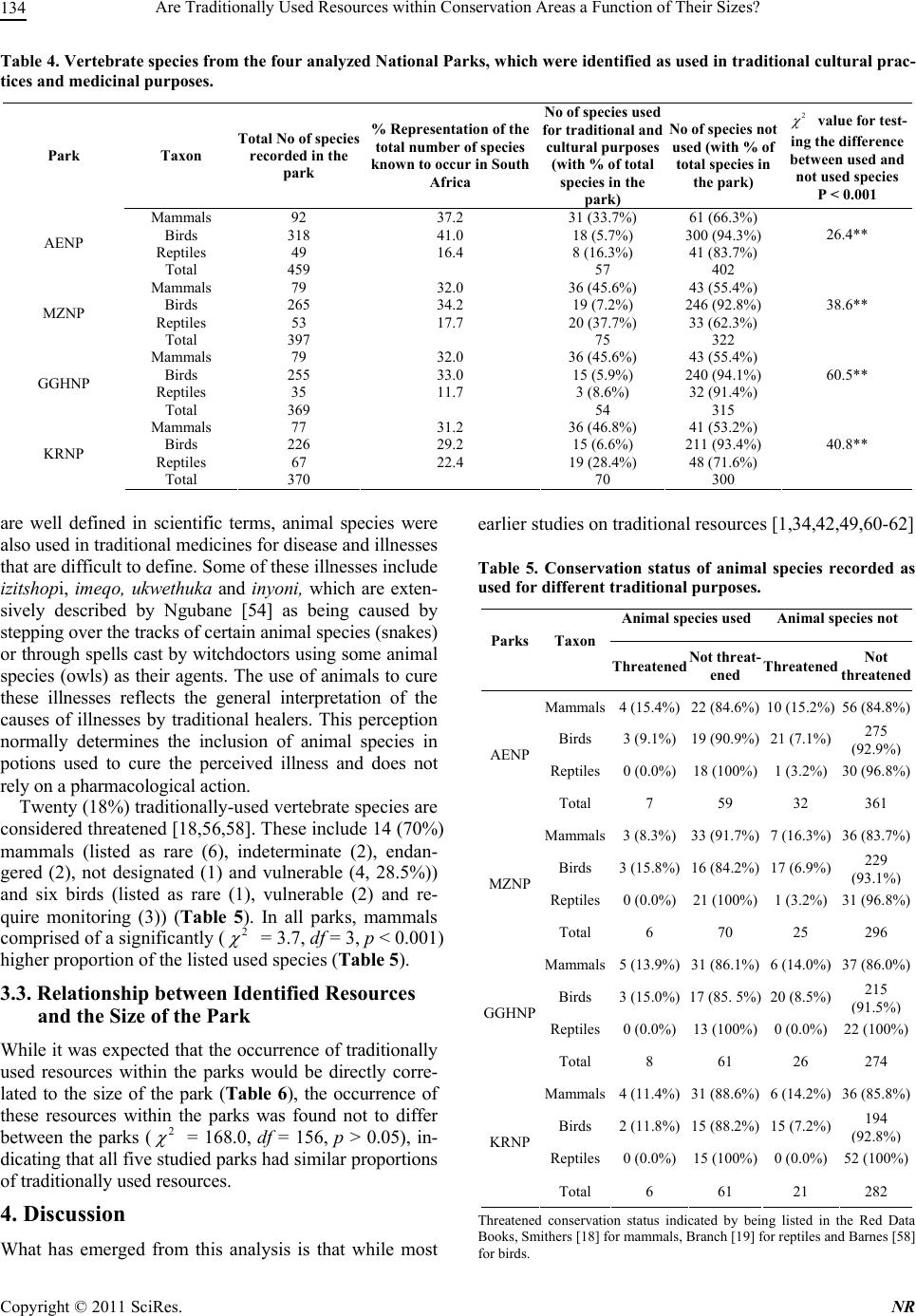

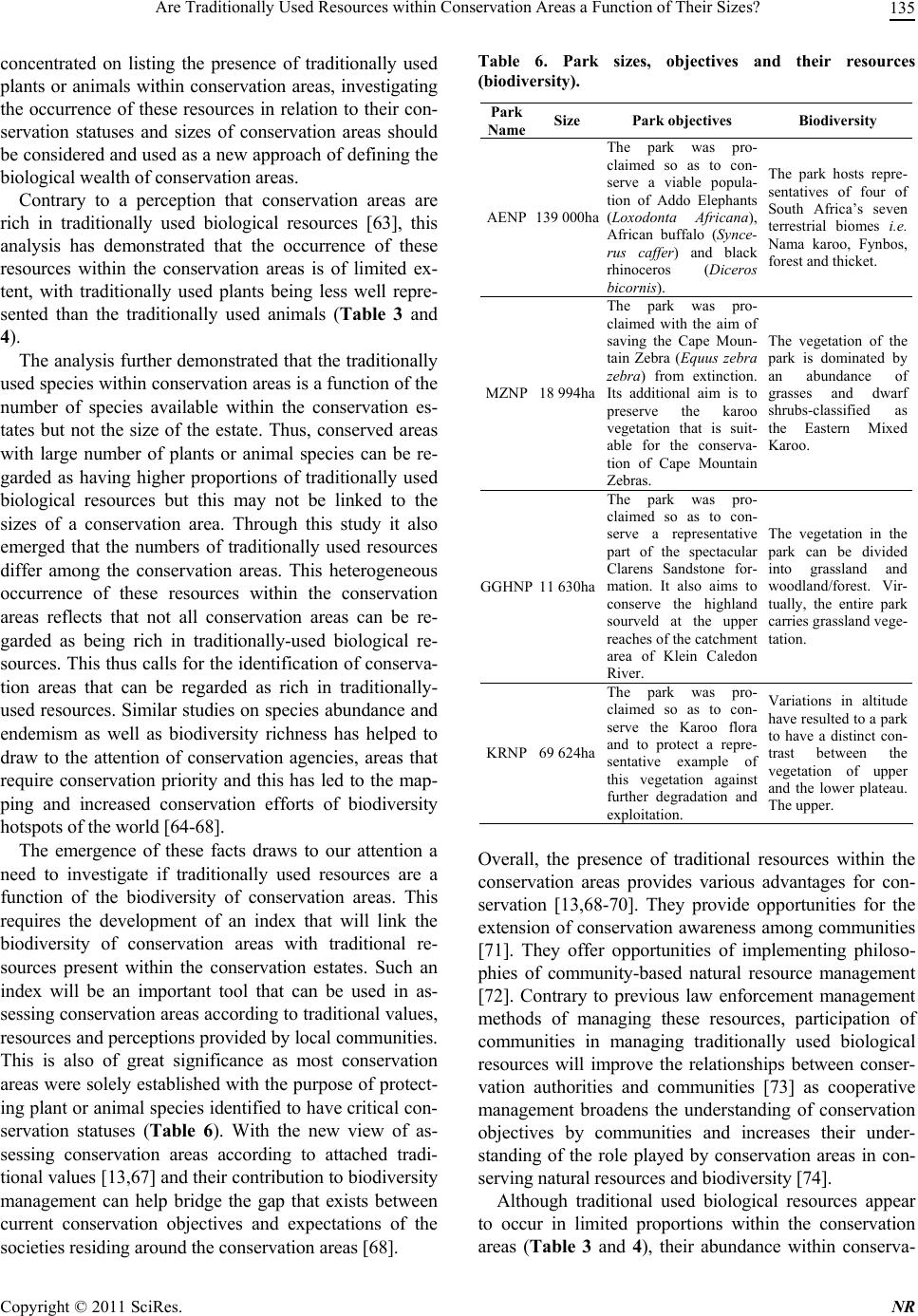

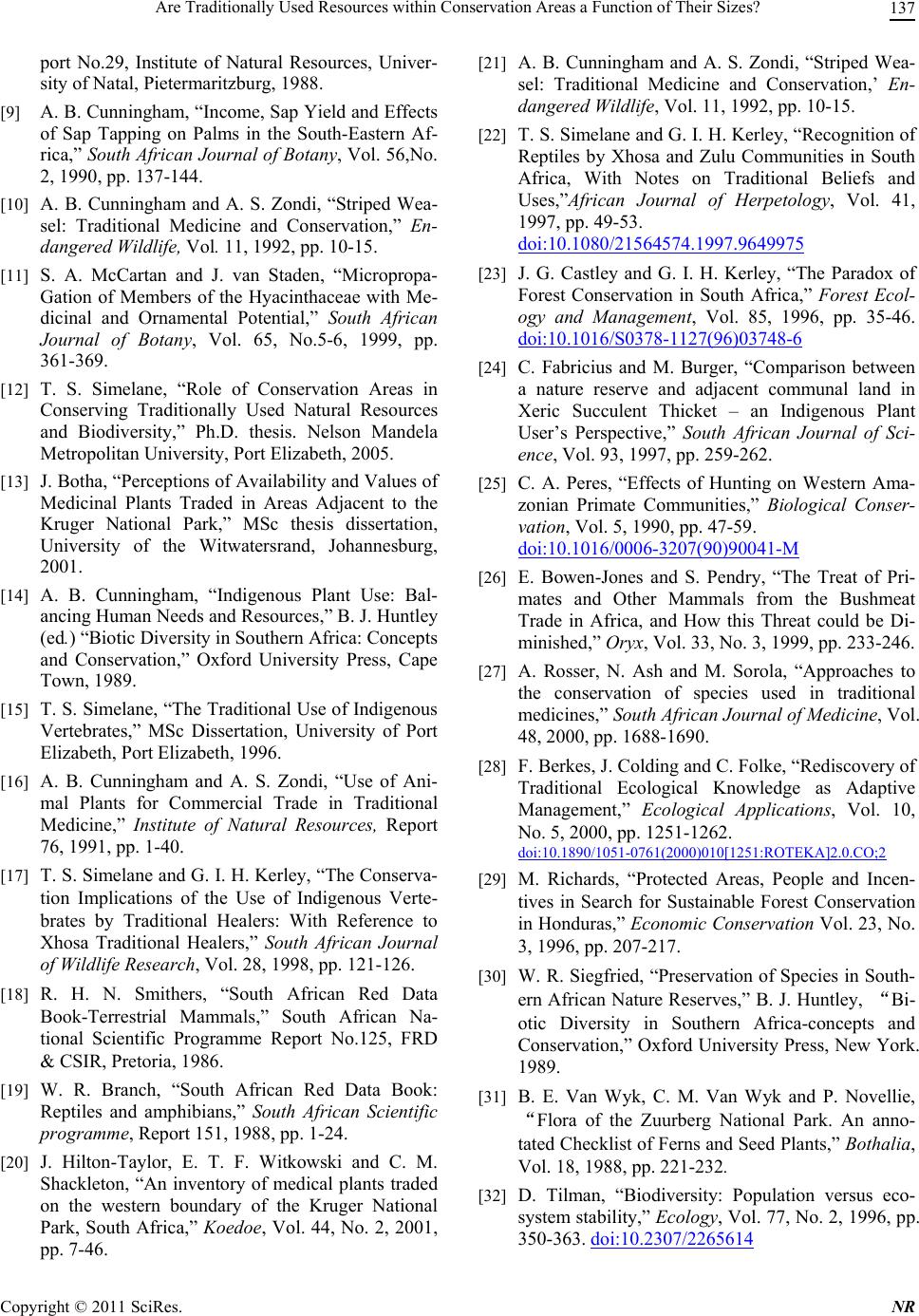

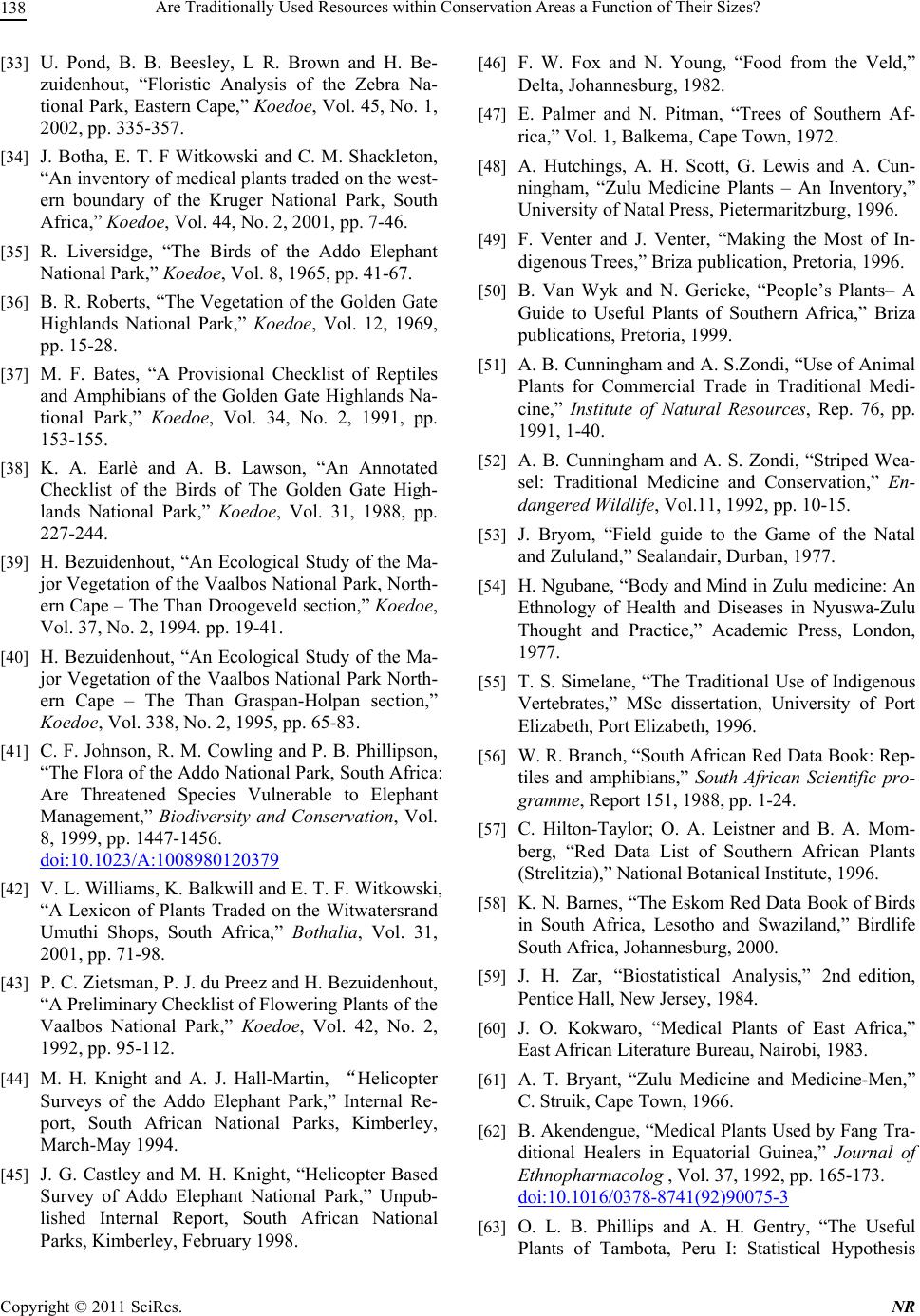

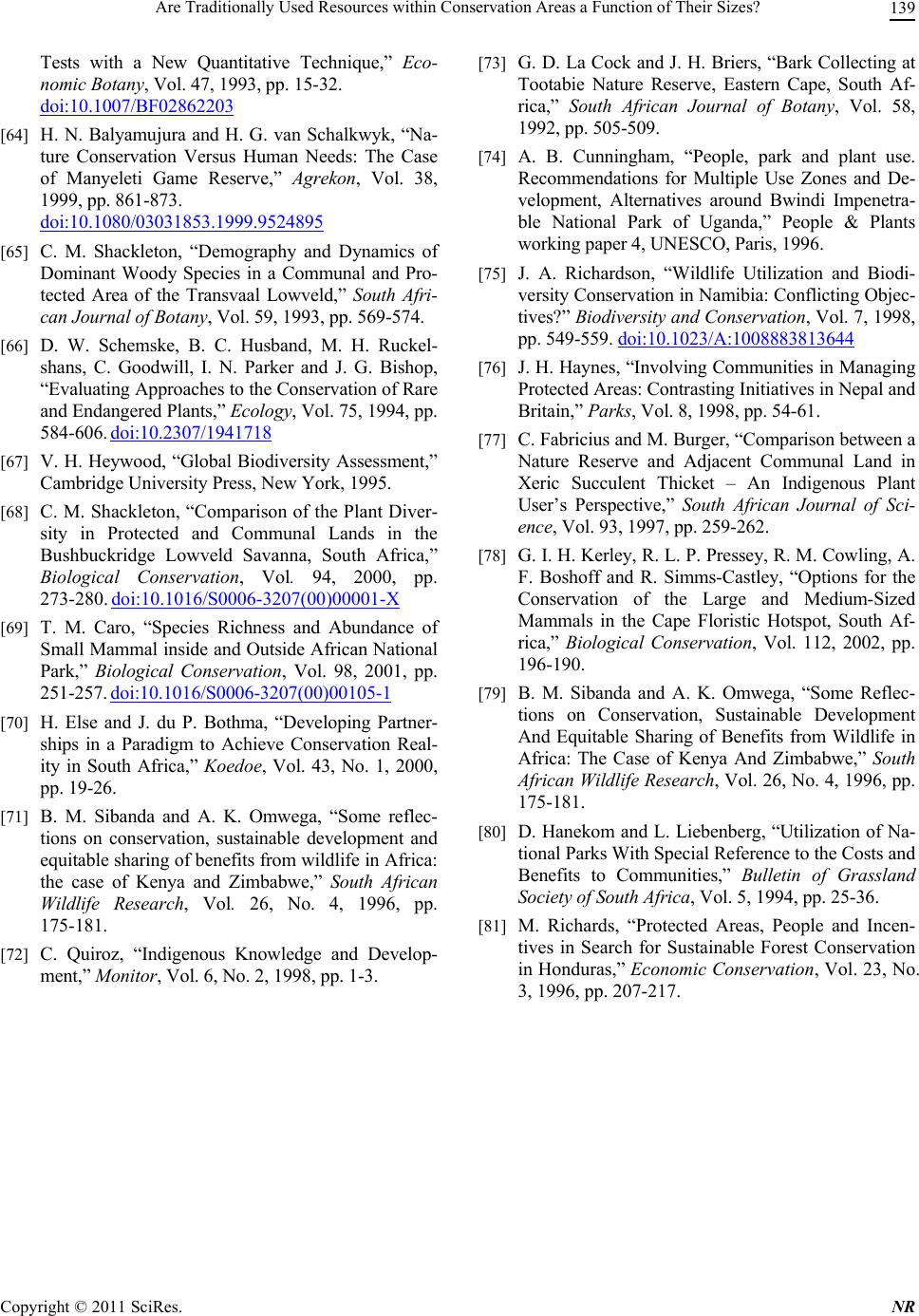

|