Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2014, 2, 32-40 Published Online November 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.211005 How to cite this paper: Pidgeon, A.M. and Giufre, A.C. (2014) Shoulda’ Put a Ring on It: Investigating Adult Attachment, Relationship Status, Anxiety, Mindfulness, and Resilience in Romantic Relationships. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2, 32-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.211005 Shoulda’ Put a Ring on It: Investigating Adult Attachment, Relationship Status, Anxiety, Mindfulness, and Resilience in Romantic Relationships Aileen M. Pidgeon, Alexandra C. Giufre Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia Email: alexa nd ragiu fre@ liv e.c om Received Sep te mber 2014 Abstract This study aimed to investigate the predictive ability of relationship status, anxiety, mindfulness, and resilience in relation to the two orthogonal dimensions of adult attachment: attachment anxie- ty and attachment avoidance. 156 participants completed measures assessing relationship status, adult attachment, anxiety, mindfulness and resilience. The results showed that resilience and the relationship status of single significantly predicted attachment anxiety, whereas anxiety and being either single or divorced significantly predicted attachment avoidance. A significant mediating role of resilience in the prediction of attachment anxiety from being single was also observed. The main implications of this study provided preliminary support for the significant predictive value of resilience in attachment anxiety. Keywords Attachment, Romantic Relationships, Relationship Status, Anxiety, Mindfulness, Resilience 1. Introduction Romantic relationships are one of the most important relationships formed in many people’s lives with interper- sonal communication being central to romantic relationships. The way two people interact when they first meet can either ignite or extinguish hopes of future romance [1]-[3]. Although numerous benefits emerge from en- gaging in romantic relationships [4] [5], challenges such as relationship conflict can also arise [3]. For many in- dividuals, the costs of a successful relationship can sometimes far outweigh the benefits, resulting in many men and women terminating their romantic relationship. Relationship termination can represent the end of a rela- tionship resulting in singlehood, separation from a partner, or divorce. Extensive research has shown that sepa- ration, divorce, and singlehood can increase the risk of negative emotions, behaviours, and health concerns [6] [7]. Such negative consequences warrant extending upon previous research to further our understanding of the modifiable factors that predict a successful and high quality romantic relationship.  A. M. Pidgeon, A. C. Giufre The theory of adult attachment styles has its roots in Bowlby [8], and offers a promising theoretical frame- work for understanding variations in the quality of romantic relationships [3] [9]. Research on adult attachment indicates the importance of secure attachments for well-being and interpersonal functioning [2]. Individuals with different attachments differ greatly in the nature and quality of their close relationships [3]. Adult attachment in romantic relationships can be reliably assessed by self-report measures that examine two orthogonal dimensions: attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance [10] [11]. The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale [11] which measures these dimensions has been criticized by its problematic length, and thus a psychometrically sound shorter version of the measure was developed named the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-Sho r t Form [12]. However to date, no study has utilised this shortened measure of adult attachment. This current study will inves ti gate the predictive factors of romantic relationships in regards to both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance assessed by the ECR-S. 2. Relationship Status A paucity of research to date has directly examined the issue of the association between adult attachment and relationship status. For example, research by Adamczyk and Bookwala [13] investigated the association between adult attachment and relationship status (single vs. partnered) in a Polish university sample. Within their study, adult attachment was determined based on a three-dimensional measure conceptualised by Collins and Read [14]. These three dimensions captured an individual’s confidence that a partner would be loving (anxiety dimen- sion), belief of a partner’s availability and responsiveness (depend dimension), and desire for close contact with a partner (close dimension). In terms of scoring, the “depend” and “close” dimensions were combined in order to create one factor that incorporated the two factors. Collins and Reads’ three-dimensional model is similar to that of Brennan et al. [11] as both contain an anxiety dimension, with the combined factor of “depend” and “close” equating to the avoidance dimension. The results of Adamczyk and Bookwala’s study showed that indi- viduals classified as single reported higher levels of worry about being rejected or feeling unloved (anxiety di- mension), lower levels of comfort with closeness (close dimension), and lower levels of comfort with depending on other people (depend dimension) compared to partnered individuals. This current study will add to the body of knowledge by examining whether individuals who are single will score significantly higher on both attach- ment anxiety and attachment avoidance dimensions, as determined by the ECR-S. Additionally, a study that investigated relationship status in regards to both the orthogonal dimensions of adult attachment was conducted by Noftle and Shaver (2006) [15]. The results demonstrated that relationship status was a significant predictor of both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, where individuals who were not in a relationship scored significantly higher on both these dimensions. However, although Noftle and Shaver investigated people who were single (i.e., those who were not currently dating, in a committed relation- ship, or married), a limitation of their study was that the predictive ability of individuals who were separated or divorced was not examined. Therefore, the current study will expand upon Noftle and Shavers’ study by ad- dressing this limitation and examining adult attachment amongst individuals who are single, defacto, married, separated, and divorced. 2.1. Anxiet y Close relationships play a vital role with the onset, duration, and treatment of anxiety [16]. As such, the presence of anxiety can have detrimental long-term effects on romantic relationships. For instance, a study by Schachner et al. [7] within a community sample of single and coupled adults identified an association between the ortho- gonal dimensions of adult attachment and anxiety. In particular, significant main effects for anxiety were found where individuals who scored high on attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance also scored significantly higher on anxiety. As Schachner and Colleagues established that attachment anxiety and avoidance significantly predicted higher levels of anxiety, the present study will aim to determine whether this relationship is bi-direc- tional, by determining whether high scores of anxiety will significantly predict attachment anxiety and avoid- ance. 2.2. Mindfulness A predictor of adult attachment that has not been extensively examined in the literature is mindfulness. Bowlby [8] initially raised awareness that some of the most intense emotions experienced are those concerned with close  A. M. Pidgeon, A. C. Giufre relationships. This concept has since been investigate by Barnes Brown, Krusemark, Campbell, and Roggee (2007) [17] who examined whether mindfulness was associated with greater satisfaction in romantic relation- ships, in addition to the capacity of mindfulness to manage relationship related stress. Their results showed that individuals who scored higher on mindfulness reported greater levels of satisfaction, and better capacities to re- spond to relationship stress. Additionally, Barnes and Colleagues noted that because their sample was comprised of only dating university students, it was not established whether their results were generalisable to married couples. Conversely, it can also be assumed that their results did not generalize to single, separated, or divorced individuals. Additionally, a recent study by Leigh and Anderson [18] investigated the potential contribution of adult at- tachment to self-reported mindfulness. In particular, the researchers were interested in examining how university students who had not received mindfulness training developed the mindfulness tendencies that they reported. The researchers investigated whether attachment theory assisted in understanding the development of mindful- ness and concluded that the orthogonal dimensions of attachment anxiety and avoidance did in fact negatively predict mindfulness. In terms of methodological considerations, Leigh and Anderson measured mindfulness and attachment from the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire [19] and the Experiences in Close Relationships [11] respectively, and it is therefore of interest to the present study to determine if the findings from Leigh and An- dersons [18] study can be replicated using the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory [20] and the ECR-S [12]. 2.3. Resilience An additional variable of interest in relation to adult attachment that has limited empirical evidence available is resilience. To date, the relationship between resilience and adult attachment as determined by the ECR-S has not been directly investigated. However, a study by Caldwell and Shaver (2012) [21] investigated the relationship between attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, rumination, negative affect, mood repair, and ego resiliency. The authors defined ego resiliency as a “positive adjustment by fostering an open, flexible, and optimistic ap- proach to life’s diverse and often unpredictable challenges” [21], which appears to be a similar definition of re- silience used in the present study. Although Caldwell and Shavers’ study found that both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance predicted lower ego-resiliency, a structural equation model was utilized which may have influenced the results by taking into account other variables of rumination, negative affect, and mood repair. Therefore, this study will address this issue by investigating the predictive ability of resilience in relation to at- tachment anxiety and avoidance without the combination of additional variables. 2.4. The Current Study The current study aimed to examine the association of relationship status, anxiety, mindfulness, and resilience to changes in attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. H1: It was hypothesised that in regards to attachment anxiety: a Being single, separated, and divorced would be significant predictors of attachment anxiety, where individu- als who are classified as single, separated, or divorced will score higher on attachment anxiety than individ- uals who are in a relationship. b Mindfulness and resilience would be significant predictors of attachment anxiety, where individuals with lo- wer scores of mindfulness and resilience will have higher scores of attachment anxiety. c Anxiety would be a significant predictor of adult attachment, where individuals who score higher on anxiety will have higher scores of attachment anxiety. H2: It was hypothesised in regards to attachment avoidance: a Being single, separated, and divorced would be significant predictors of attachment avoidance, where indi- viduals who are classified as single, separated, or divorced will score higher on attachment avoidance than those who are in a relationship. b Mindfulness and resilience would be significant predictors of attachment avoidance, where individuals with lower scores of mindfulness and resilience will have higher attachment avoidance. c Anxiety will be a significant predictor of attachment avoidance, where individuals with high scores of an- xiety will have high attachment avoidance. H3: Resilience would mediate the relationship between being single and attachment anxiety.  A. M. Pidgeon, A. C. Giufre 3. Method 3.1. Participants Participants were 27 male and 129 female university students (N = 156). Inclusion criteria required participants to be aged 18 years or above. 3.2. Measures Demographic Questions. Participants were asked to provide information regarding their age, gender, and re- lationship status relevant to the study. Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21). The DASS-21 is a short form of the original 42-item self- report measure assessing depression, anxiety, and stress. For the purpose of the current study, the depression and stress scales were not used, as anxiety was the only variable of interest. A total anxiety score was given by summing participant’s scores, with greater scores indicating higher greater levels of anxiety. Experiences in Close Relationship Scale—Short Form (ECR-S). The ECR-S [12] assesses romantic adult relationships in general, independent from participants’ current relationship status. Items measure two underly- ing and continuous dimensions of adult attachment: attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI-14). The FMI-14 [20] is a 14-item scale measuring experiences of mindfulness over a seven-day period. Possible scores range from 14 to 56, with higher scores indicative of great- er levels of mindfulness. The Connor Davidson-Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). The CD-RISC [22] is a 25-item scale measuring stress coping ability over a month long period. Possible scores range from 25 to 125, with higher scores indicating greater levels of resilience. 4. Results Assumptions for Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses. Mean and standard deviations for each vari- able are shown in Table 1. Prior to the main analysis, a bivariate correlation was conducted to measure the lin- ear association between the predictor and criterion variables. As seen in Table 2, Anxiety was significantly positively correlated with the relationship stat us single and married, and also with attachment anxiety and at- tachment avoidance. Mindfulness was significantly negatively correlated with attachment anxiety and anxiety. Resilience was significantly negatively correlated with the relationship status single, attachment anxiety, anxiety, and positively correlated with the relationship status married and mindfulness. Main Analysis Two hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted to examine the predictive ability of relationship status (single, defacto, married, separated, and divorced), anxiety, mindfulness, and resilience on adult attachment. As relationship status, anxiety, mindfulness and resilience were all significantly correlated with attachment anxiety, these predictor variables were all included in the first hierarchical multiple regression predicting attachment an- xiety. However, as mindfulness and resilience did not significantly correlate with attachment avoidance, they were therefore excluded from the second hierarchical multiple regression predicting attachment avoidance. Table 1. Number of participants, mean scores, and standard deviations for attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, anxiety, mindfulness, and resilience. N M SD Attachment Anxiety 156 22.31 6.602 Attachment Avoidance 156 20.02 4.279 Anx i ety 156 4.93 4.762 Mindfulness 156 39.05 7.356 Resilience 156 69.06 13.692 Note: N = Number of Participants; M = Mean Score; SD = Standard Deviation.  A. M. Pidgeon, A. C. Giufre Table 2. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis predicting attachment anxiety from relationship status, an- xiety, mindfulness, and resilience. Predictor R R² Change B SE B β Step 1 0.258* Single 3.587** 1.267 0.232 Separated 5.394 6.538 0.065 Divorced -3.273 3.884 −0.068 Step 2 0.288 0.016 Anx i ety 0.183 0.111 0.132 Step 3 0.322 0.021 Mindfulness −0.134 .071 −0.149 Step 4 0.367* Resilience −0.117* .051 −0.243 *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 . A new categorical variable of “in a Relationship” was created in order to combine married and defacto into a single variable for comparison. Therefore, “in a Relationship” was excluded from the regression models to compare individuals who were in a relationship (married and defacto) to those who were not (single, separated, and divorced). Adjusted R2 was used over R2 as it provided a more accurate estimate of the true extent of the re- lationship between the predictor and criterion variables. Relationship Status, Anxiety, Mindfulness, and Resilience as Predictors of Attachment Anxiety. On step one of the hierarchical multiple regression, relationship status accounted for a significant 4.8% of variance in at- tachment anxiety, F(3, 152) = 3.603, p = 0.015. On step two, anxiety was added and accounted for an additional non-significant 1.6% of variance in attachment anxiety, ∆F(1, 151) = 2.708, p = 0.102. On step three, mindful- ness was added and accounted for an additional non-significant 2.1% of variance in attachment anxiety, ∆F(1, 149) = 3.598, p = 0.060. On step four, resilience was added and accounted for an additional significant 3.1% of variance in attachment anxiety ∆F(1, 149) = 5.346, p = 0.022. In combination, relationship status, anxiety, mind- fulness, and resilience accounted for 10% of variance in attachment anxiety, adjusted R2 = 0.100, F(6, 149) = 3.872, p = 0.001. By Cohen’s (1988) conventions, a combined effect of this magnitude can be considered “me- dium” (f² = 0.15). As can be seen in the standardised beta coefficients, relationship status and resilience were the strongest predictors of attachment anxiety, where individuals who were single had higher scores on attachment anxiety than individuals who were in a relationship, and those who scored lower on resilience also scored higher on attachment anxiety. Relationship Status and Anxiety as Predictors of Attachment Avoidance. On step one, relationship status accounted for a significant 11.4% of the variance in attachment avoidance, adjusted R2 = 0.114, F(3, 152) = 7.637, p = < 0.001. On step two, anxiety was added to the regression equation and accounted for an additional significant 5.9% of variance in attachment avoidance, ∆R2 = 0.059, ∆F(1, 151) = 11.042, p = 0.001. In combina- tion, relationship status and anxiety accounted for 16.9% of variance in attachment avoidance, adjusted R2 = 0.169, F(4, 151) = 8.867, p = < 0.001. By Cohen’s [23] conventions, a combined effect of this magnitude can be considered “medium” (f² = 0.23). As can be seen from the standardised beta coefficients in Table 3, relationship status was the greatest predictor of attachment avoidance, where individuals who were single had higher scores of attachment avoidance compared to individuals who were in a relationship. Additionally, divorce was the only relationship’ status that significantly predicted attachment anxiety. Furthermore, individuals who scored higher on anxiety also scored higher on attachment avoidance. Resilience as a Mediator between being Single and Attachment Anxiety. The four criteria stated by Baron and Kenny (1986) [24] were used to determine whether resilience mediated the relationship between being sin- gle and attachment anxiety. Thus, linear and hierarchical multiple regression analysis, and a Sobel test [25] were performed to test the third hypothesis that resilience mediated the relationship between being single and attach-  A. M. Pidgeon, A. C. Giufre Table 3. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis predicting attachment avoidance from relationship status and anxiety. Predictor R R2 Change B SE B β Step 1 0.362** Single 3.710*** 0.792 0.370 Separated 4.939 4.089 0.092 Divorced 4.939* 2.429 0.159 Step 2 0.436** 0.190 Anx i ety 0.225** 0.068 0.251 Note: N = 156; CI = confidence interval. *p < 0.05 ; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. ment anxiety. In the simple regression analysis, being single accounted for a significant 5.1% of the variability in attachment anxiety, adjusted R2 = 0.051, F(1, 154) = 9.379, p = 0.003. Examination of the coefficients indi- cated being single predicted higher attachment anxiety (B = 3.707, SE = 1.210, β = 0.240, p = 0.003), with 95% confidence the true score is not zero. The second criteria was also met where being single accounted for a significant 4.7% of the variability in re- silience, adjusted R2 = 0.047, F(1, 154) = 8.652, p = 0.004. Examination of the coefficients indicated that being single predicted lower scores of resilience (B = −7.400, SE = 2.516, β = −0.231, p = 0.004), with 95% confi- dence the true score is not zero. The third criteria was also met where resilience accounted for a significant 8.4% of variability in attachment anxiety, adjusted R² = 0.084, F(1, 154) = 15.291, p < 0.001. Examination of the coefficients indicated that lower resilience predicted higher attachment anxiety, (B = −0.145, SE = 0.037, β = −0.301, p < 0.001), with 95% con- fidence the true score is not zero. In addition, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine if the fourth criteria stated by Baron and Kenny (1986) [24] was satisfied. As can be seen in Figure 1, the standardised regression coeffi- cient between being single and attachment anxiety decreased when resilience was added to the model (a shift of β = 0.240 to β = 0.180). Resilience was found to reduce the significance of the standardised regression coeffi- cient between being single and attachment anxiety (a shift of p = 0.003 to p = 0.022), indicating a full mediation of being single by mindfulness in prediction of attachment anxiety. Figure 1 shows the mediating relationship of resilience between being single and attachment anxiety. As the addition of resilience weakened the strength of the predictive relationship between being single and attachment anxiety, a Sobel test [25], was conducted to de- termine whether this observed change was significant. This analysis showed the change in the predictive value of being single was significant. Z = 2.35, p = 0.01, indicating that the relationship between being single and at- tachment anxiety was mediated by resilience. 5. Discussion The purpose of the current study was to investigate the relationship between adult attachment, relationship status, anxiety, mindfulness, and resilience in romantic relationships. In particular, this study aimed to determine whe- ther relationship status, anxiety, mindfulness, and resilience significantly predicted scores of attachment anxiety and avoidance as measured by the ECR-S. The results indicated that the 12-item Experiences in Close Relation- ship Scale—Short Form [12] provided a reliable and valid measure of adult attachment within romantic rela- tionships. To the researchers knowledge this is the first study to utilise the short form of the original Experiences in Close Relationship Scale [11] since its establishment, and therefore provides replicability and support of the ECR-S within a non-clinical and student population. The main findings of this study showed that in regards to the first aspect of hypothesis one, which predicted attachment anxiety from relationship status, being single was the only relationship status that significantly pre- dicted attachment anxiety. This is consistent with previous research by Noftle and Shaver (2006) [15] who found that within a sample of single individuals, relationship status was a significant predictor of attachment anxiety, where individuals who were not in a romantic relationship scored significantly higher on attachment anxiety. Furthermore, these findings are also in support of the increased anxiety reported by single individuals [7].  A. M. Pidgeon, A. C. Giufre Figure 1. The relationship between being single and attachment anxiety, with resilience as a mediator. Note: Values represent the standardised β weights. β in the parenthesis indicates the changed value after resilience was added to the regression model. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Additionally, resilience was also found to significantly predict attachment anxiety. This relationship supports the research by Caldwell and Shaver (2012) [21] who investigated the r esilience -attachment relationship. How- ever, in contrast to resilience, mindfulness was not found to be a significant predictor of attachment anxiety. This finding is inconsistent with research by Barnes et al. (2007) [17] that have associated mindfulness to posi- tive relationship functioning. In regards to attachment avoidance, being single or divorced were both found to be significant predictors, however, this relationship changed to only divorced being significant when the variable of anxiety was added into the regression equation. These findings that individuals who were either single or divorced significantly predicted attachment avoidance were consistent with previous research by Noftle and Shaver (2006) [1 5]. Mindfulness and resilience were not found to significantly predict attachment avoidance, as the main analyses could not be examined as both mindfulness and resilience did not significantly correlate with attachment avoid- ance. This was not anticipated as previous research as shown a negative relationship between attachment avoid- ance and mindfulness [18] and ego-resiliency (Caldwell & Shaver, 2012) [21]. It is possible that this occurred due to different sampling and methodological issues in the present study compared to previous research. Additionally, anxiety was found to be a significant predictor of attachment avoidance. These results are in support of previous research such as Schachner et al. [7], who found that attachment avoidance predicted higher levels of anxiety. Although the current study was interested in whether anxiety predicted attachment avoidance, the results are still in favour of Schachner’s and Colleagues anxiet y-attachment relationship. Finally, the results showed that resilience fully mediated the relationship between being single and attachment anxiety. As previously mentioned, the standardised regression coefficient between being single and attachment anxiety decreased when resilience was added into the model. Additionally, resilience was found to reduce the significance of the standardised regression coefficient between being single and attachment anxiety. These re- sults suggest that although individuals who are single are predictive of attachment anxiety, if they also possess high levels of resilience, then this in turn can decrease their levels of attachment anxiety. This is a substantially important contribution to the field of adult attachment, considering that single individuals tend to report in- creased, depression, anxiety, and sexual displeasure [7]. To the researchers knowledge this is the first study to investigate whether resilience significantly mediates the relationship between being single and attachment anxi- ety. Therefore, the obtained results provide promising preliminary findings for future research on adult attach- ment, relationship status, and resilience. A limitation must be considered when interpreting the results of this study. It is possible that the “si ngle ” category did not only include individuals who were single but also those who were “single again” as a result of separation, divorce, or widowhood. It is therefore likely that participants who classified themselves as “single” were in fact not true members of the single category. This is important to address for future research on romantic attachments, as experiences of individuals who have always been single may differ from those who find them- selves single again after previously being married or in a long-term committed relationship. The results obtained in this study further expand upon previous literature within adult attachment, in addition to establishing a platform for future research focusing on adult attachment and resilience. Not only has the cur- rent study highlighted the importance of investigating the different types of relationship status (single, defacto, married, separated, and divorced) in regards to adult attachment, but the findings also provide preliminary sup- port for the significant predictive value of resilience in regards to attachment anxiety. As such, this study raised Attachment Anxiety Single Resilience −0.231** −0.301*** 0.240** (0.180)  A. M. Pidgeon, A. C. Giufre awareness and created dialogue of a promising arena of adult attachment that has very minimal research cur- rently available. As resilience was found to be a significant predictor of attachment anxiety, in conjunction with significantly decreasing the relationship between being single and attachment anxiety, investigating resilience within romantic relationships is therefore a fundamental avenue in need of further research. In particular, an area that may warrant further investigation is the introduction of attachment-based resilience interventions within romantic relationships. Such interventions may address the consequences and issues concerning individuals who experience attachment anxiety, in conjunction with how resilience can enhance the quality of an individual’s romantic relationship. In conclusion, this study established a number of new and important relationships to the field of adult attach- ment that deserve further attention and replicability in order to fully ascertain the influence of the predictive factors that constitute a successful, healthy, and “loved up” r elations hip. References [1] Collins, W.A., Welsh, D.P. and Furman, W. (2009) Adolescent Romantic Relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 631-652. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459 [2] Mikulincer, B. and Shaver, P.R. (2007) Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change. Guilford Press. [3] Plessis, K.D., Clarke, D. and Woolley, C.C. (2007) Secure Attachment Conceptualisations: The Influence of General and Specific Relational Models on Conflict Beliefs and Conflict Resolution Styles. Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationshi ps , 1, 25-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.5964/ijpr.v1i1.3 [4] Assad, K.K., Donnellan, M.B. and Conger, R.D. (2007) Optimism: An Enduring Resource for Romantic Relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 285-297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.285 [5] Wachs, K. and Cordova, J.V. (2007) Mindful Relatin g: Exploring Mindfulness and Emotion Repertoires in Intimate Relationships. Journal of Marital Family Therapy, 33, 464-481. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606 .20 07. 0003 2.x [6] Amato, P.R. (2000) The Consequences of Divorce for Adults and Children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 1269- 1287. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01269.x [7] Schachner, D.A., Shaver, P.R. an d Gillath, O. (2008) Attachment Style and Long-Term Singlehood. Personal Rela- tionships, 15, 479-491. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00211.x [8] Bowlby, J. (1973) Attachment and Lo ss . Basic Books, New Yor k. [9] Daniel, S.I. (2006 ) Adult Attachment Patterns and Individual Psychotherapy: A Review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 968-984. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.02.001 [10] Bartholomew, K. and Horowitz, L.M. (1991) Attachment Styles among Young Adults: A Test of a Four-Category Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61. 2.22 6 [11] Brennan, K.A., Clark, C.L. and Shaver, P.R. (1998) Self-Report Measurement of Adult Attachment: An Integrative Overvi e w. In: Simpson, J.A. and Rholes, W.S., Eds., Attachment Theory and Close Relationships, Guilford Press, New York, 46-76. [12] Wei, M., Russell, D.W., Mallinckrodt, B. and Vogel, D.L. (2007) The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR) —Short Form: Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88, 187-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223890701268041 [13] Adamczyk, K. and Bookwala, J. (2013) Adult Attachment and Single vs. Partnered Relationship Status in Polish Un i - versit y Students. P sychol ogica l Topics, 22, 481-500. Retrieved from Adult Attachment and Single vs. Partnered Rela- tionship Status in Polish University Students—ProQuest. [14] Collins, N.L. and Read, S.J. (1990) Adult Attach ment, Working Models, and Relationship Quality in Dating Couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 644-663. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644 [15] Noftle and Shaver (2006). [16] Whisman, M.A. (2007) Marital Distress and DSM-IV Psychiatric Disorders in a Pop ulat ion -Based National Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 638-64 3 . http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.638 [17] Barnes Brown, Krusemark, Campbell and Roggee (2007). [18] Leigh, J. and Anderson, V.N. (2013) Secure Attachment and Autonomy Orientation May Foster Mindfulness. Con- temporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 14, 265-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14639947.2013.832082 [19] Baer, R.A., Smith, G.T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J. and Toney, L. (2006) Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets of Mi ndfulness. Assessment, 13, 27-45. http ://d x.doi .o rg/10 . 1177 /10 7319 11 0528 35 04 [20] Walach, H., Buchheld, N., Buttenmuller, V., Kleinknecht, N. and Schmidt, S. (2006) Measuring Mindfulness—The  A. M. Pidgeon, A. C. Giufre Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 1543-1555. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025 [21] Caldwell and Shaver (2012). [22] Connor, K.M. and Davidson, J.R. (2003) Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18, 76-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.10113 [23] Cohen, J. (1998) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale. [24] Baron and Kenny (1986). [25] Sobel, M.E. (1982) Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects in Structural Equation Models. In: Leinhardt, S., Ed. , Sociological Methodology, American Sociological Association, Washington DC, 290-312 .

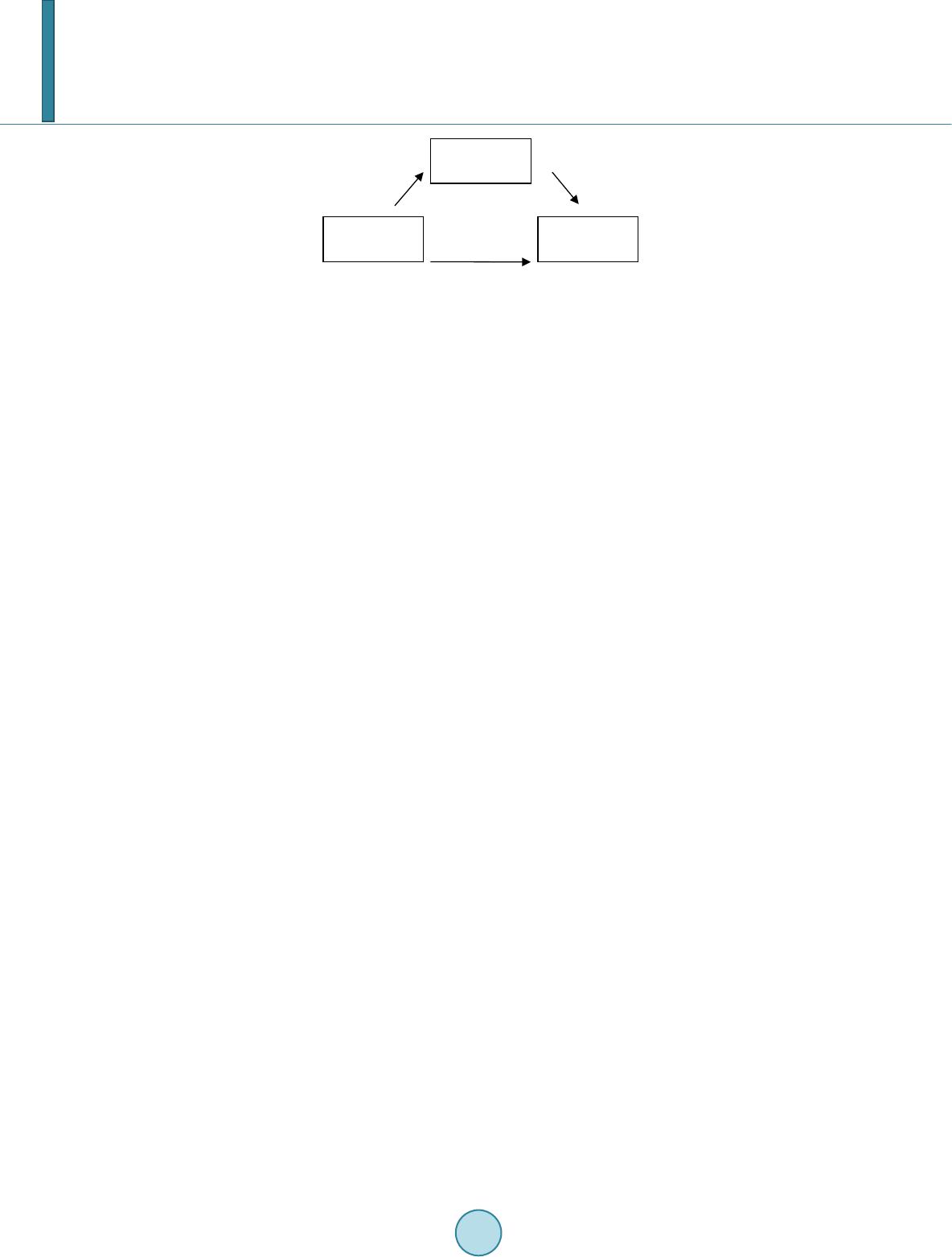

|