Vol.2, No.2, 104-1 doi:10.4236/as.2011.22015 C opyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 10 (2011) Agricultural Sciences Assessment of microbial pools by an innovative microbiological technique during the co-composting of olive mill by-products Teresa Casacchia1, Pietro Toscano1, Adriano Sofo2*, Enzo Perri1 1CRA, Centro di Ricerca per l’Olivicoltura e l’Industria Olearia, c. da Li Rocchi-Vermicelli, Rende, Italy; teresa.casacchia@entecra.it; pietro.toscano@entecra.it; enzo.perri@entecra.it 2Dipartimento di Scienze dei Sistemi Colturali, Forestali e dell’Ambiente, Università degli Studi della Basilicata, Potenza, Italy; *Corresponding Author: adriano.sofo@unibas.it Received 25 January 2011; revised 9 February 2011; accepted 2 March 2011. ABSTRACT Different mixtures of olive pomace (OP), olive mill wastewater (OMWW) and olive pruning residues (OPR) were aerobically co-composted under natural conditions. Compost temperature showed a sharp increase in the first 40 - 60 days, followed by a stabilization at 60°C and a decline after 150 days, whereas compost water content ranged from 50% - 55% to 25% - 30%. Total and selective microbial counts were followed throughout the experiment by means of innova- tive (IMT) and conventional (CMT) microbiologi- cal techniques. Pseudomonas spp., anaerobic bacteria, actinomycetes, and fungi reached lev- els of 8, 7, 5 and 6 log CF U g–1 compost, respec- tively, with a slight depression after 30-80 days. Total and fecal coliforms strongly decreased during the composting process. The use of IMT allowed to detect a higher and more stable growth of microorganisms if compared to CMT. IMT was demonstrated to be an appropriate and reliable method for monitoring the microbial pools during the co-composting process. Keywords: Composting; Olive Mill Wastewater; Olive Pomace; P runing Re sidues 1. INTRODUCTION The olive pomace (OP), also called ‘sansa vergine’ in Italian or ‘orujo’ in Spanish, is defined as the residue that remains after the first oil extraction from olives (crude olive cake). The OP is a dry material with a 8% - 10% moisture and is composed of ground olive stones and pulp, with a high lignin, cellulose, and hemicellu- loses content, and a 3% - 5% oil content, depending on the olive mill typology (pressure or centrifugation) [1]. This by-product is usually used for residual oil extrac- tion by solvents, heating, animal feed supplement, or as an organic amendant for olive grove or other crops soils [2]. In terms of agronomic value, OP watered with olive mill wastewater (OMWW), another product of olive milling, or with other organic material lead to a product that supplies nutrients to plants and is an efficient method for the disposal of olive mill residuals [3,4]. According to the Italian law 574/1996, it is possible to use not-composted OMWW and OP for agronomic pur- poses, as they are considered simple plant amendants, with no limitations on the amounts of OP to be applied to the soil, but the CEE Regulation 91/156 indicates that composting is one of the methods to recycle and recov- ery organic wastes. Olive-mill wastewater (OMWW) is composed by the own water of the olives (vegetation water) and the water used in the different stages of oil elaboration [1]. From an environmental point of view, OMWW is an environ- mental emergency as it has a considerable polluting or- ganic load, with a maximum biological oxygen demand and chemical oxygen demand of about 100 and 220 kg·m–3, respectively, an average concentrations of vola- tile solids and inorganic matter of 15% and 2%, respec- tively, and organic matter fraction that includes sugars, tannins, polyphenols, polyalcohols, pectins and lipids [5]. Therefore, a series of studies focused on the degradation of OMWW and its chemical components [5-8], and many authors used specific microorganisms for OMWW treatment [9-13]. Microbiological and physicochemical parameters were used as indicators to study the kinetic of OMWW biodegradation, such as chemical oxygen demand (COD), dissolved organic carbon, counts of heterotrophs, filamentous fungi, and yeasts, and content of K, P and N [8-14]. As OMWW does not generally contain sufficient N and P for an adequate aerobic puri- fication process, OMWW degradation may be performed  T. Casacchia et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 104-110 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 105 by co-composting, anaerobic digestion or enzymatic treatment [8-15]. Some authors obtained satisfactory results, in terms of OMWW degradation and ameliora- tion of soil physicochemical properties, by adding this liquid waste to agro-industrial and urban wastes and monitoring the physicochemical parameters during the composting process of these matrices [16-18]. Angeli- daki and Ahring [19] studied a combined anaerobic di- gestion of OMWW together with manure, household waste or sewage sludge, and with this method they managed to degrade OMWW without previous dilution, without addition of external alkalinity and without addi- tion of external nitrogen source. Other authors [3] effi- ciently monitored over four months a compost made of OP, OMWW and poultry manure, by following tem- perature, pH, humidity and C/N ratio, in order to ascer- tain its maturity, and tested its effectiveness in increasing potato agronomic production. Furthermore, the co- composting of exhausted olive cake with poultry manure and sesame shells was recently investigated, and this process was followed by studying some physicochemical parameters [4]. Generally, the study on composting process of olive mill by-products was focused on their physicochemical aspects. On this basis, the present study was performed to evaluate if mixtures of olive mill pomace, olive mill wastewater and olive pruning residues (OPR), without the adding of any other additive external to olive grove, can be efficiently composted under “in farm”, non-in dustrial procedures conditions, based on spontaneous aerobic degradation by autochthonous microorganisms. This methods of compost production needs limited re- sources, low energetic inputs, and uses machinery and equipment often already present in the farm. As informa- tion on selective media for the microorganism responsi- ble for the spontaneous aerobic degradation of compost deriving from different olive material, and in particular from OP, is lacking, we have tested an innovative micro- biological technique (IMT) based on microorganisms cultivation using a broth extracted from the matrix to be composted. This method could be used to monitor the biomass degradation process during OP co-composting. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Compost Production The composting trials were carried out in a three-year period (2006-2008) under “in farm” and open field en- vironmental conditions located in San Demetrio Corone (Southern Italy, Calabria Region, 39°34’ N, 16°21’ E). The matrix for compost production included: olive po- mace (OP) and olive mill wastewater (OMWW) deriving from a three-phases olive mill, and rain water, added with grinded olive branches and leaves deriving from pruning residues (OPR). OPR were added in order to give a better structure of the composting matrices. Depending on the by-products availability in the ex- perimental field, the matrix composition in the three years was, respectively: year 2006 (from 17 March to 4 October): 200 q OP + 8 m3 OMWW + 20 q OPR; year 2007 (from 14 March to 28 September): 300 q OP + 80 q OPR; year 2008 (from 21 March to 30 September): 400 q OP + 5 m3 OMWW + 250 q OPR. The matrix, uniformly mixed to form a trapezoidal parallelepiped pile (volume = 52, 60 and 129 m3 in 2006, 2007 and 2008, respectively) placed outdoor in open field, resulted to have a semi-solid consistency. It was blended with a mechanical shovel every 7 days, in order to ensure the aeration and control the warmth of the biomass, and was subjected to a spontaneous degradation by autoch- thonous microorganisms. The aeration allowed to reduce anaerobic fermentation and the consequent high produc- tion of putrefactive, toxic compounds for aerobic micro- organisms. Compost maturation was followed by weekly sam- plings to monitor compost temperature (CT) and compost water content (CWC). The values of CT were measured by a digital thermometer (model 46908; TR snc, Italy). The values of CWC were determined from the weight differences of compost samples before and after drying at 105˚C for 24 h, and expressed as percentages of water on dry matter. The mean chemical parameters measured at the end of the composting process in the three years were the following: humidity = 27.5 ± 1.48% (SD), pH = 7.05 ± 0.35, C/N = 24.15 ± 1.06, total organic carbon = 31.4 ± 0.99%, organic matter = 54 ± 1.70%, N = 1.3 ± 0.10%, P2O5 = 0.7 ± 0.03%, K2O = 1.15 ± 0.10%. Approximately every 25 days, compost samples (5 kg) were randomly collected in different parts and depths of the pile during reversal procedures using sterile gloves, placed in sterile plastic bags, and stored in a refrigerated box at 4˚C for 1 h. Before the microbiological analyses, compost samples were sieved at 4 mm and successively at 2 mm, to eliminate the roughest fractions. 2.2. Microbiological Analysis The screening of microbic pools has been carried out at different steps of composting process. Two methods were utilized: an innovative microbiological technique (IMT) here applied for the first time, and a conventional microbiological technique (CMT) by methods usually adopted in soil analysis [20]. For CMT, a 10 g aliquot of compost was mixed to 90 ml of sterile peptoned water (triptone 10 g·L–1 and so- dium chloride 5 g·L–1; pH 7.2) and diluted up to 108 in a  T. Casacchia et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 104-110 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 106 physiological solution. Microbial community has been assessed through plate-counter and expressed as col- ony-forming units (CFU) per mL. Serial dilutions, using peptoned water as diluent, were prepared to obtain CFU counts in the range of 30 - 300 per plate and 100 µl of the corresponding decimal dilutions were plated in triplicate the following specific nutritive media: Plate Count Agar (PCA; Oxoid Lim., Hampshire, UK) for total cultural bacteria; Yeast Dextrose Agar (YPD: 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) supplemented with 150 ppm chloramphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) for moulds and yeast; Pseudomonas Agar Base medium (Oxoid) with the addition of Pseudomonas C-N supplement (Oxoid) for Pseudomonas spp.; PCA under anaerobic conditions for anaerobic bacteria; Violet Red Bile Agar (VRBA; Merck and Co. Inc., NJ, USA) for total coliforms; and Slanetz and Bartley medium (Merck) for fecal coliforms. All plates were incubated at 25˚C, as this temperature is adequate for mesophilic microorganisms [20], with the exception of fecal coliforms, that were incubated at 44˚C. Microbial counting took place after 24, 36 and 48 h. For IMT, a 10-g aliquot of compost was mixed to 90 ml of sterilized olive matrix broth (OMB), extracted from the matrix. The OMB was obtained by melting 1 kg of compost matrix in 3 L of sterile de-mineralized water. The 1:3 ratio was chosen on the basis of various trials carried out in our laboratory. The solution was fil- tered with a cheesecloth, and successively sterilized at 121˚C for 20 min, in order to obtain the final OMB. For the microbiological analyses of each compost sample, the OMB used was obtained from that specific sample. The values of pH in the OMBs used ranged from 6.7 to 7.2, with a mean of 7.0 ± 0.2 (SD). For IMT, OMB was utilized as a diluents both for scalar dilutions and sub- strate preparation. The serial dilutions procedures and the growth media used were the same of CMT. Each measurement was replicated three times and the mean values (± SD) were calculated. 2.3. Statistical Analysis Data were treated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the SAS software (SAS Institute, NC, USA) in order to detect significant differences (PROC GLM). 3. RESULTS AND DIS CUSSION A new approach in fruit orchard management is im- posed by environmental emergencies, such as soil deg- radation, water shortage and greenhouse effect [21]. In particular, in olive groves a positive influence of sus- tainable orchard management, including pruning residues re-use and compost application, on soil biochemical cha- racteristics and soil microbial diversity was recently ob- served [22,23]. Among the agronomic sustainable prac- tices, the input of soil organic matter as compost is one of the most important factor affecting soil fertility, in terms of enhancement of soil permeability and water retention, better endowment and availability of nutrients for plants, higher CO2 uptake and carbon fixation, and reduction of soil erosion [23-26]. In all the three years of the experiment, the CT values of the matrices showed a similar trend, with a sharp in- crease in the first 40 - 60 days followed by a stabilization (Figure 1). This period, characterized by high values of CT, corresponds to the so called active composting time (ACT), the phase of bio-oxidation, during which the de- gradation processes of labile organic components facili- tated by pile aeration occurs, with high heat release and oxygen consumption [2,15]. During the ACT, CT remained quite stable for about 40-50 d, reaching maximum values of about 60˚C (Fig- ure 1). These high temperatures allows compost hy- gienization during the ACT and thus are an important requisite for the following utilization of the compost. The bio-oxidative phase was considered finished after 140, 160 and 155 days in 2006, 2007, 2008, respectively, when CT started to decrease and reheating did not occur (Figu Figure 1. Compost temperature (black circles) and compost water content (white circles) during the year (a) 2006, (b) 2007 and (c) 2008. The values represent the averages (± SD) of 10 independent replicates.  T. Casacchia et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 104-110 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 107 re 1). In fact, during the following maturation time (curing), degradation processes and heat production fin- ish, whereas the biosynthesis of humic compounds occurs by fungi [24]. As for CT, the values of CWC showed similar trends in the three years, starting from values of 50-55% and reaching values of about 25% - 30% at the end of curing, with a progressive and gradual decrease throughout the degradation process (Figure 1). While some authors used OMWW as a substrate for the production of enzymes and organic compounds by mi- croorganisms [27,28], the microbiological application of sterilized compost extracts were never studied. The use of IMT allowed to detect a higher growth of microorganisms if compared to CMT (Figur e 2), likely due to the fact that OMB is richer of nutrients if compared to peptoned water, and its compositions is similar to that usually experienced by the microorganisms living in the compost. Another Figure 2. (a) Total cultural bacteria, (b) Actinomycetes, and (c) yeasts and moulds counts (read after a 36-h incubation) using the innovative microbiological technique (IMT; dashed lines) or the conventional microbiological technique (CMT, continuous lines). Experimental period: 2006 (black circles), 2007 (white circles) and 2008 (triangles). The values represent the averages (± SD) of three independent replicates. All the IMT and the respective CMT resulted to be significantly different (P ≤ 0.05). advantage is that the cultures based on OMB showed more stable and comparable values both throughout the experimental period and between the three years (Figure 2), a basic requisite for their use as bio-indicators of the composting degradation process. The trends of microbial number detected by IMT (Figures 2 and 3), and in par- ticular the kinetics of total and fecal coliforms (Figure 3(c,d)), indicate that this technique could be also adopted for olive grove soils, and urban and industrial sludge, two Figure 3 . (a) Pseudomonas spp., (b) anaerobic bacteria, (c) total coliforms, and (d) fecal coliforms counts (read after a 36-h incubation) using the innovative microbiological technique (IMT; dashed lines) or the conventional microbiological tech- nique (CMT, continuous lines). Experimental period: 2006 (black circles), 2007 (white circles) and 2008 (triangles). The values represent the averages (± SD) of three independent rep- licates. All the IMT values and the respective CMT values resulted to be significantly different (P ≤ 0.05), with the excep- tion of those with the asterisk on the top. Total culturable bacteria (log CFU g–1 compost) Actinomvcetes (log CFU g–1 compost) Fungi (log CFU g–1 compost) Pseudomonas spp. (log CFU g–1 compost) Anaerobic ba cteria (log CFU g–1 compost) Total coliforms (log CFU g–1 compost) Fecal coliforms (log CFU g–1 compost) 2006 2007 2008 Innovative Conventional  T. Casacchia et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 104-110 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 108 matrices that host microorganisms living in conditions similar to those studied in this paper [3,8]. Total cultural bacterial counts determined by IMT did not significantly differ during the three years (Figure 2(a)), so highlighting that bacterial growth is not inhib- ited by the different percentages of OMWW, a by-product with a very high concentration of polyphenols [1,4]. Ac- tinomycetes (e.g., Streptomyces), fungi produce a number of enzymes that help degrade organic plant material, such as lignin and chitin, and so are abundant in soils rich of organic matter [20]. Furthermore, actinomycetes are able to use root exudates as carbon source, supply roots with easily assimilable nitrates, and are involved in the sup- pressive action of the soil [23]. Actinomycetes (Figure 2(b)), and fungi (Figure 2(c)), counted by IMT, reached levels of about 5 and 6 log CFU g–1 compost, respectively. The use of specific cultural media allowed the isolation of important physiological groups of microorganisms related to compost maturation (Figure 3). Pseudomonas spp. and anaerobic bacteria (e.g., Bacillus spp.) are the main decomposers of complex polymers, such as ligno- celluloses and chitin, but they also have proteolytic en- zymes and are of key-importance important for the pro- duction of assimilable nitrogen in soils [20]. The ob- served trends of microbial counts using IMT, show that Pseudomonas spp. (Figure 3(a)) and anaerobic bacteria (Figur e 3(b)) reached levels of about 8 and 7 log CFU g–1 compost, respectively. The slight decrease of the micro- bial numbers of these two groups during the first 30-40 days (Figure 3(a,b)) was likely due to the increase of temperature [1]. Moreover, this depression started earlier if compared to Actinomycetes, and yeasts and moulds, that declined during the first 70-80 days (Figure 2(b,c)). The high number of Pseudomonas spp. observed throughout the composting process (Figure 3(a)) indi- cates that these microorganisms are affected by the or- ganic content of the matrix and are able to initiate their oxidative biodegradation without being particularly in- hibited by polyphenols. The presence of anaerobic bac- teria (Figure 3b) indicates that, considering the size of the compost pile and the high microbial activity, with the consequent strong oxygen demand, mechanical aeration did not allow the complete removal of anaerobic degra- dation processes. On the other hand, the use of compost in agriculture is often associated with health risks because of the possible presence of human pathogens, enteric in origin, such as bacteria, viruses, protozoa and helminthes [25]. The number of total and fecal coliforms strongly decreased during compost maturation (Figure 3(c,d)), so attesting the efficiency of degradation process and the good hygi- enic conditions of the matrix. In fact, coliform bacteria are of key importance because the low number or the absence Figure 4. Total cultural bacteria counts read after an incubation time of 12 h (black columns), 24 h (white columns) and 36 h (grey columns) by using (a) the innovative microbiological technique (IMT) or (b) the conventional microbiological tech- nique (CMT). The values represent the three-years averages (± SD) of three independent replicates. All the values obtained by 12-h incubation time were significantly different (P ≤ 0.05) from those of 24-h and 36-h incubation times, whereas no sig- nificant differences (P ≤ 0.05) were found between the values of 24-h and 36-h incubation times. of this group of micro-organisms indicates compost heal- thiness and safety [25]. Notwithstanding the widespread use as amendants of olive mill residues and by-product in Mediterranean countries, legislative limits for compost deriving from these matrices are lacking. The only micro- biological threshold values for compost application in agriculture, present in the EC Regulation 1774/2002, are 1000 CFU g–1 compost for both Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp., and 0 CFU g–1 compost for Salmo- nella spp. Thus, we suggest that the use of total and fecal coliforms could be efficacious bio-indicators, more spe- cific and less variable than the microbial groups listed in EC Regulation 1774/2002. Our investigation also focused on the more appropriate incubation time before colonies counting. In Figure 4 we reported the averages total cultural bacterial counts calcu- lated from the values of the three years, determined by IMT (Figure 4(a)) and CMT (Figure 4(b)). For both CMT and IMT, a counting time of 36 h was the most reliable, as total and specific microbial counts ranged between 4 and 9 log CFU g–1 compost. In fact, the range of microbial number after 24 h was lower (between 0 and 2 log CFU g–1 com- post), whereas after 48 h it did not vary significantly from the that obtained after a 36-h incubation. Total culturable bacteria (log CFU g–1 compost)  T. Casacchia et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 104-110 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ 109 00. 4. CONCLUSIONS Our experiment demonstrated that sterilized olive ma- trix broth can represent an efficacious diluent to be used for monitoring the microbial pools during the co-com- posting of olive mill by-products. The results also show that the aerobic stabilization of olive pomace, suitably co-composted with olive mill wastewater and/or other crop by-products, is a real sustainable agronomical prac- tice, that allows to obtain a low-cost stabilized organic amendant, in line with the legislative parameters of mixed composted amendants (Italian law 748/1984). The ap- plication of this product could recovery, maintain or in- crease soil fertility, with environmental benefits and positive influence on crop yields. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Authors thanks to Mr. Carlo Priori, owner of composting site, for his hospitality and support during the experimental field activities. REFERENCES [1] Niaounakis, M. and Halvadakis, C.P. (2006) Olive proc- essing waste management: Literature review and patent survey. 2nd Edition, Elsevier Ltd., Kidlington. [2] Alburquerque, J.A., Gonzálvez, J., García, D. and Cegarra, J. (2004) Agrochemical characterisation of “Alperujo”, a solid by-product of the two-phase cen- trifugation method for olive oil extraction. Bioresource Technology, 91, 195-2 doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(03)00177-9 [3] Hachicha, S., Sallemi, F., Medhioub, K., Hachicha, R. and Ammar, E. (2008) Quality assessment of composts prepared with olive mill wastewater and agricultural wastes. Waste Management, 28, 2593-2603. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2007.12.007 [4] Sellami, F., Jarboui, R., Hachicha, S., Medhioub, K. and Ammar, E. (2008) Co-composting of oil exhausted olive-cake, poultry manure and industrial residues of agro-food activity for soil amendment. Bioresource Technology, 99, 1177-1188. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.02.018 [5] Benitez, J., Beltran-Heredia, J., Torregrosa, J., Acero, J.L. and Cercas, V. (1997) Aerobic degradation of olive mill wastewaters. Appied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 47, 185-188. doi:10.1007/s002530050910 [6] Vitolo, S., Petrarca, L. and Bresci, B. (1996) Treatment of olive oil industry wastes. Bioresource Technology, 67, 129-137. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(98)00110-2 [7] Beccari, M., Carucci, G., Lanz, A.M., Majone, M. and Petrangeli Papini, M. (2002) Removal of molecular weight fractions of COD and phenolic compounds in an integrated treatment of olive oil mill effluents. Biodeg- radation, 13, 401-410. doi:10.1023/A:1022818229452 [8] Amaral, C., Lucas, M.S., Coutinho, J., Crespí, A.L., do Rosário Anjos, M. and Pais, C. (2008) Microbiological and physicochemical characterization of olive mill wastewaters from a continuous olive mill in northeastern Portugal. Bioresour ce Technology, 99, 7215-7223. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.12.058 [9] Robles, A., Lucas, R., Alvarez de Cienfuegos, G. and Gálvez, A. (2000) Biomass production and detoxification of wastewaters from the olive oil industry by strains of Penicillium isolated from wastewater disposal ponds. Bioresource Technology, 74, 217-221. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00022-5 [10] Tsioulpas, A., Dimou, D., Iconomou, D. and Aggelis, G. (2002) Phenolic removal in olive oil mill wastewater by strains of Pleurotus spp. in respect to their phenol oxi- dase laccase activity. Bioresource Technology, 84, 251- 257. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00043-3 [11] D’Annibale, A., Ricci, M., Quaratino, D., Federici, F. and Fenice, M. (2004) Panus tigrinus efficiently removes phenols, color and organic load from olive-mill waste- water. Research in Microbiology, 155, 596-603. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2004.04.009 [12] Dias, A.A., Bezerra, R.M. and Nazaré Pereira, A. (2004) Activity and elution profile of laccase during biological decolorization and dephenolization of olive mill waste- water. Bior esource Technology, 92, 7-13. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2003.08.006 [13] Lanciotti, R., Gianotti, A., Baldi, D., Angrisani, R., Suzzi, G., Mastrocola, D. and Guerzoni, M.E. (2005) Use of Yarrowia lipolytica strains for the treatment of olive mill wastewater. Bior esource Technology, 96, 317-322. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2004.04.009 [14] Fadil, K., Chahlaoui, A., Ouahbi, A., Zaid, A. and Borja, R. (2003) Aerobic biodegradation and detoxification of wastewaters from the olive oil industry. International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation, 51, 37-41. doi:10.1016/S0964-8305(02)00073-2 [15] Paredes, C., Bernal, M.P., Cegarra, J. and Roig, A. (2002) Bio-degradation of olive mill wastewater sludge by its co-composting with agricultural wastes. Bioresource Technology, 85, 1-8. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00078-0 [16] Paredes, C., Roig, A., Bernal, M.P., Sánchez-Monedero, M.A. and Cegarra, J. (2000) Evolution of organic matter and nitrogen during co-composting of olive mill waste- water with solid organic wastes. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 32, 222-227. doi:10.1007/s003740000239 [17] Paredes, C., Bernal, M.P., Roig, A. and Cegarra, J. (2001) Effects of olive mill wastewater addition in composting of agroindustrial and urban wastes. Biodegradation, 12, 225-234. doi:10.1023/A:1017374421565 [18] Paredes, C., Cegarra, J., Bernal, M.P. and Roig, A. (2005) Influence of olive mill wastewater in composting and impact of the compost on a swiss chard crop and soil properties. Environment International, 31, 305-312. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2004.10.007 [19] Angelidaki, I. and Ahring, B.K. (1997) Codigestion of olive oil mill wastewaters with manure, household waste or sewage sludge. Biodegradation, 8, 221-226. doi:10.1023/A:1008284527096 [20] Picci, G. and Nannipieri, P. (2002) Metodi di analisi mi- crobiologica del suolo-Ministero delle Politiche Agricole e Forestali. Franco Angeli Edizioni, Milan. [21] Hochstrat, R., Wintgens, T., Melin, T. and Jeffrey, P. (2006) Assessing the European wastewater reclamation and reuse potential—A scenario analysis. Desalination,  T. Casacchia et al. / Agricultural Sciences 2 (2011) 104-110 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/AS/ Openly accessible at 110 188, 1-8. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2005.04.096 [22] Moreno, B., Garcia-Rodriguez, S., Cañizares, R., Castro, J. and Benítez, E. (2009) Rainfed olive farming in south-eastern Spain: Long-term effect of soil manage- ment on biological indicators of soil quality. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 131, 333-339. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2009.02.011 [23] Sofo, A., Palese, A.M., Casacchia, T., Celano, G., Ricciuti, P., Curci, M., Crecchio, C. and Xiloyannis, C. (2010) Genetic, functional, and metabolic responses of soil mi- crobiota in a sustainable olive orchard. Soil Science, 175, 81-88. doi:10.1097/SS.0b013e3181ce8a27 [24] Toscano, P., Casacchia, T. and Zaffina, F. (2009) Recu- perare i reflui oleari per ri-fertilizzare i suoli. Olivo e Olio, 4, 49-53. [25] Diacono, M. and Montemurro, F. (2010) Long-term ef- fects of organic amendments on soil fertility. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 30, 401-422. doi:10.1051/agro/2009040 [26] Toscano, P., Casacchia, T. and Zaffina, F. (2009) The “in farm” olive mill residual composting for by-products sustainable reuse in the soils organic fertility restoration. Proceedings of the 18th Symposium of the International Scientific Centre Of Fertilizers—More Sustainability in Agriculture: New Fertilizers And Fertilization Manage- ment, 8-12 November 2009, Rome,116-121. [27] D’Annibale, A., Giovannozzi Sermanni, G., Federici, F. and Petruccioli, M. (2006) Olive-mill wastewaters: A promising substrate for microbial lipase production. Bio- resource Technology, 97, 1828-1833. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2005.09.001 [28] Papanikolaou, S., Galiotou-Panayotou, M., Fakas, S., Komaitis, M. and Aggelis, G. (2008) Citric acid produc- tion by Yarrowia lipolytica cultivated on olive-mill wastewater-based media. Bioresource Technology, 99, 2419-2428. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.05.005

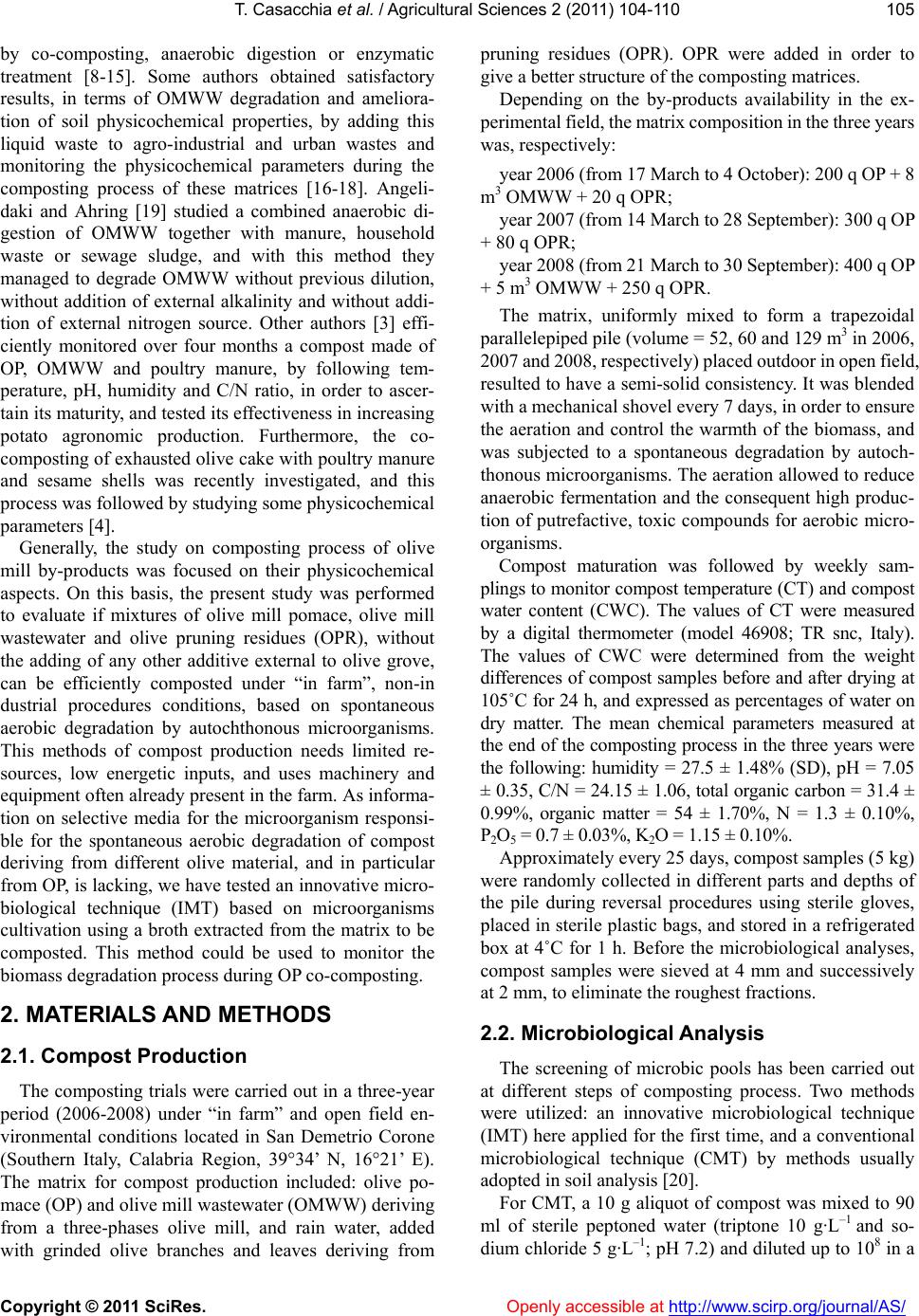

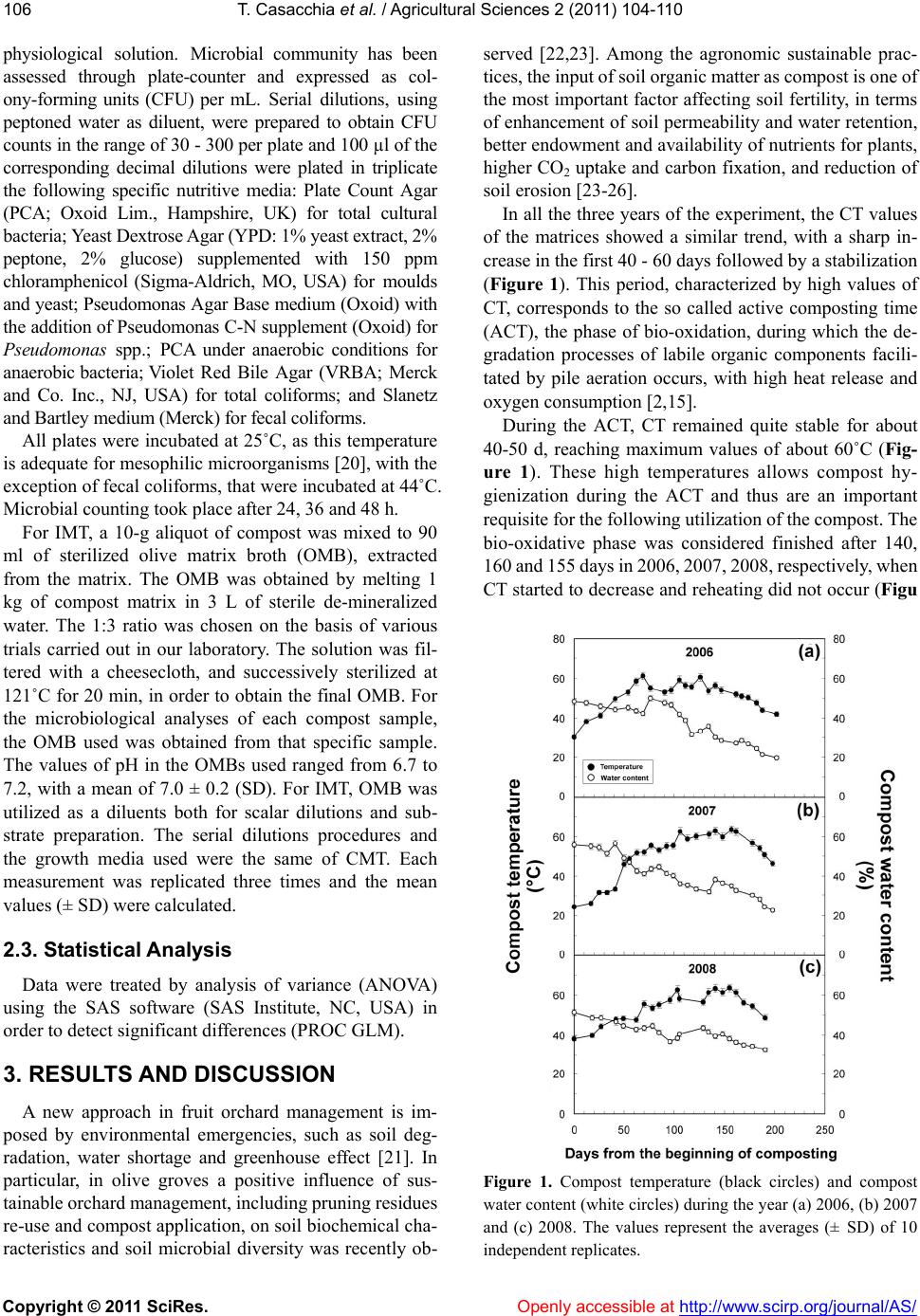

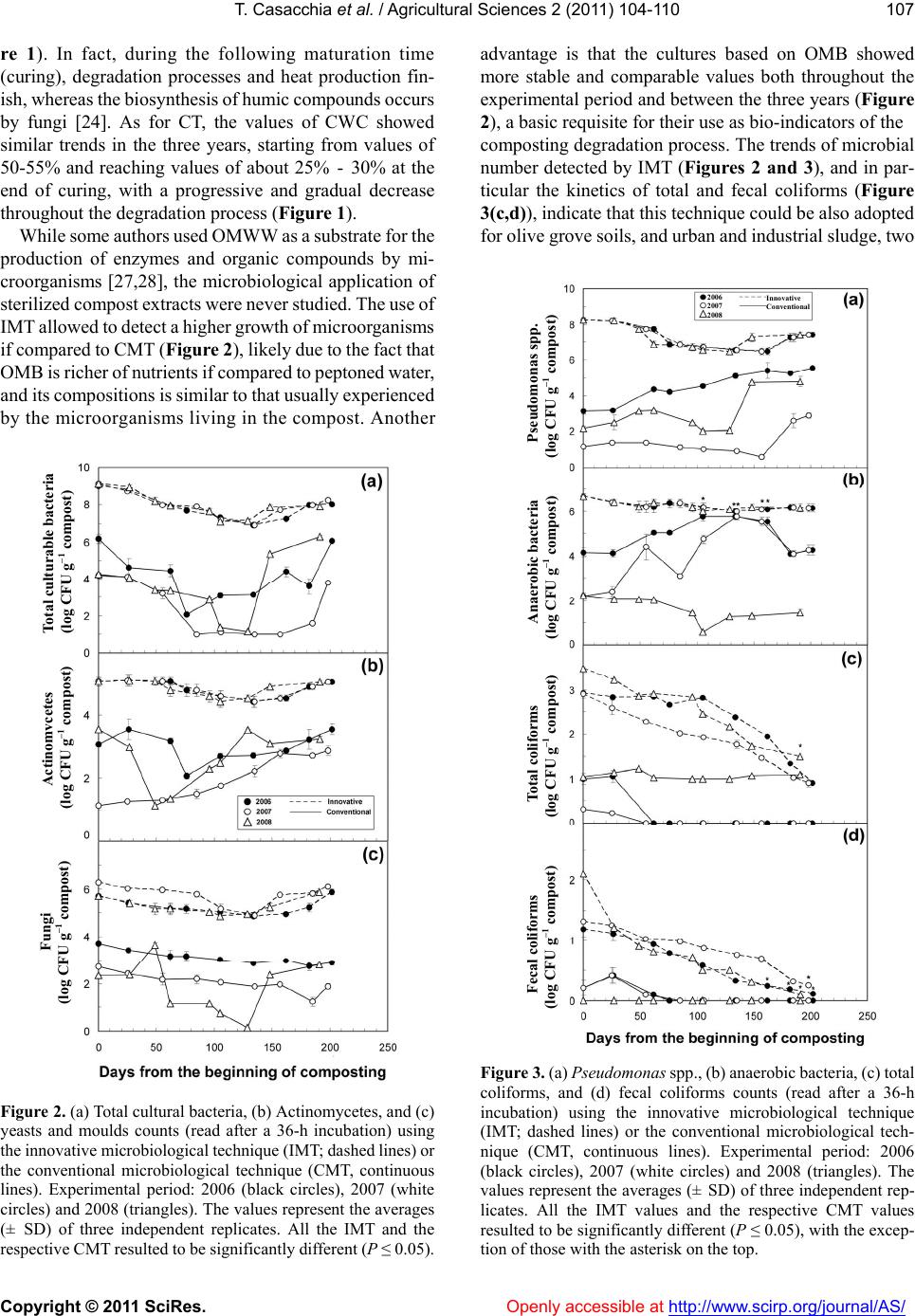

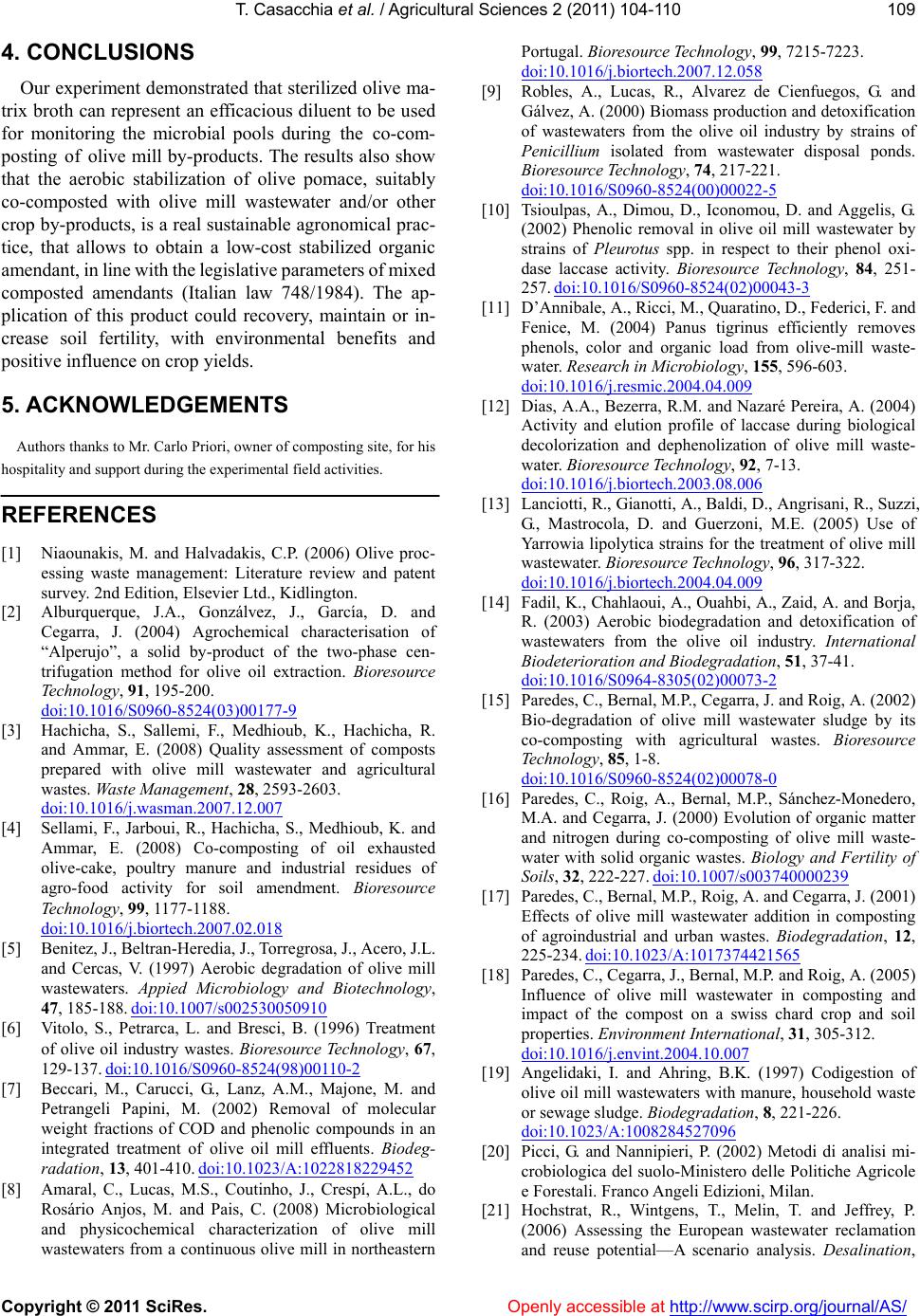

|