Journal of Service Science and Management

Vol.09 No.01(2016), Article ID:63462,9 pages

10.4236/jssm.2016.91005

Research about the Influence of CEPA on the Service Trade in Mainland China and Hong Kong

Chen Yan

School of Economics, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 11 January 2016; accepted 14 February 2016; published 17 February 2016

ABSTRACT

Development of service industry and service trade plays an important role in the transition of economic structure of our country. Based on the CEPA, this paper uses service trade data of Hong Kong and its five principal trade partners with 48 sub-industries between the year of 1998 and 2013 to carry out descriptive statistical research and difference-in-difference empirical analysis about the service trade export from Hong Kong to Mainland China after implementing CEPA. Research results show: firstly, CEPA greatly promotes the level of service trade between Mainland China and Hong Kong and the amount of service trade exports from Hong Kong to Mainland China averagely increases by 10.7 - 10.8 billion Hong Kong dollars; secondly, the service trade from Hong Kong to Mainland China presents structural imbalance, and traditional service industries like tourism and transportation have prominent promotion while modern service industries like finance and commerce have little promotion. Aiming at these conclusions mentioned above, this paper puts forward some suggestions in the aspect of magnifying the effect of CEPA, adjusting service trade structure and further putting the policies of CEPA into practice.

Keywords:

CEPA, Service Trade, Difference-in-Difference

1. Introduction

Arrangement about Establishing Closer Economic and Trade Relations between Mainland China and Hong Kong (hereinafter referred as CEPA) was officially implemented on January 1st, 2004 and then many supplementary agreements were signed. The goal of CEPA is to strengthen the trade and investment cooperation between Mainland China and Hong Kong through taking the following measures: first, gradually reduce or eliminate all the tariff and non-tariff barriers of goods trade materially between the two parties; second, gradually realize service trade liberalization and reduce or eliminate all measures of discrimination materially between the two parties; third, promote trade and investment facilitation. CEPA mainly contains three topics: goods trade, service trade and investment facilitation. Among the three topics, the arrangement about service trade should be paid more attention. Because in the aspect of service trade, there exists a great gap in competitive power between Mainland China and Hong Kong and the liberalization of service trade between the two parties will exist huge trade creation effect. In addition, both Mainland China and Hong Kong face the problem of economic transition, and the implementation of CEPA benefits the development of service trade of the two parties and promotion of industrial restructuring. In the aspect of service industry, specific commitments of CEPA and other supplementary agreements mainly reflect in the aspect of preferential measures aiming at all kinds of service market access and the preferential forms include allowing sole proprietorship, reducing the limits of shareholding, reducing requirement of capital stock, enlarging business lines and reducing geographic restrictions. Up until the end of 2014, CEPA involves 48 industries in total, including all service components in Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department. Since CEPA was implemented, what influences it has had on service trade between the two parties? What are the problems existing in the process of implementing CEPA service trade clauses? These problems are attracting scholars’ extensive attention. Measuring service trade creation effect between Hong Kong and Mainland China is the focus of this paper.

2. Literature Review

Since CEPA was signed, many scholars have carried out deeper academic researches centering on the functions and effects of CEPA on service trade between the two parties. Through establishing the model of producer service trade liberalization under the assumptions of perfect competition and constant returns to scale, Chen Guanghan (2005) analyzed and proved the implementation of CEPA has positive influence on service industry both in Mainland China and Hong Kong [1] . Luo Nianbei (2006) used trade openness, foreign capital openness, RCA indexes and TSC indexes to analyze service trade effect of CEPA, knowing Mainland China and Hong Kong had strong complementary in the field of service trade and both of them can achieve win-win from it [2] . Zhang Jie and Xu Zhenyan (2007) used RCA indexes to analyze and got the result that since the CEPA was implemented, both the relation between Mainland China and Hong Kong and service trade complementarity have been reinforced [3] . Hua Xiaohong (2008) analyzed the influence of CEPA on the different fields of service trade between Mainland China and Hong Kong, finding CEPA had smaller influence on traditional field than that in newly- developing field; in addition, she also pointed out the design capacity of CEPA hadn’t been not fully given play and the investment of Hong Kong on Mainland China service scope mainly focused on traditional fields [4] . Cai Hongbo (2011) made use of Revealed Comparative Advantage index and Trade Specialization Coefficient indexes to analyze and get the result that since the year of 2004, the competitive advantages of Hong Kong over Mainland China didn’t affect by measures of liberalization, but further strengthened in the process of comprehensive fusion with Mainland China [5] . Mao Yanhua (2013) utilized Balassa Model to carry out static effect analysis about bilateral service trade, getting the result that CEPA had service trade creation effect both on Mainland China and Hong Kong; through analyzing dynamic effect of bilateral service trade, get CEPA has strengthened complementarity and competitiveness of service trade between Mainland China and Hong Kong, and at the same time, it benefited industrial structure upgrade of the two places; besides, she also pointed out CEPA didn’t have obvious promotion on bilateral service trade and the proportion that modern service industry took up was rather low [6] . Zhang Yingwu (2015) also proved CEPA didn’t have significant effects on Hong Kong service export in the aspect of amount, but in the lay of industry, CEPA promoted service export in the field of tourism and finance of Hong Kong to Mainland China, and as well as the service export in the field of insurance [7] . Researches of literatures mentioned above offer good references, and meanwhile we also can see researches in recent years don’t reach consistent results and mainly concentrate on the aspect of qualitative researches. This paper attempts to further study from the aspect of quantification and proposes empirical evidences for enacting policies.

3. General Situation about Bilateral Service Trade between Hong Kong and Mainland China

3.1. General Developing Status of Bilateral Service Trade

Firstly, amount of service trade export from Hong Kong to Mainland China has increased greatly in recent years, and the volume of trade has increased to 63.2 billion Hong Kong dollars in 2003 from 44 billion Hong Kong dollars of 1998, which increases by 1.6 times, and the average rate of growth has reached to 9.9% in Figure 1. After CEPA was officially implemented in 2004, volume of trade increases to 317 billion Hong Kong dollars in 2013 from 78.9 billion Hong Kong dollars of 2004, the amount of service trade export has increased by above 4 times and the average rate of growth reaches to 16.7%. It can be seen that compared to the years before the CEPA was implemented, the amount of service trade export from Hong Kong to Mainland China has greater increase after the implementation of CEPA. Along with the increase in amount of service trade export, the proportion of service export from Hong Kong to Mainland China which accounts for in the amount of service export of Hong Kong also increases, especially after CEPA was carried out, the proportion has increased to 40.6% in 2013 from 25.2% of 2004 and Mainland China becomes the largest exporter of service trade of Hong Kong.

Secondly, the increase in service trade import from Mainland China to Hong Kong is relatively steady. The volume of trade increases to 235.9 billion Hong Kong dollars from the 197.7 Hong Kong dollars of 1998, which increases by about 1.2 times with the average rate of growth of 0.32%. In can be seen the growth in amount of service import is far from the service export. At the same time, after the year of 2004, the proportion of service trade import from Mainland China to Hong Kong which accounts for in the amount of service import of Hong Kong gradually decreases, but in 2013, it still maintains 40.7% and Mainland China is still the largest importer of service trade of Hong Kong.

Finally, with the great increases in amount of service trade export and the steady growth of amount of import, Hong Kong achieved the transformation of bilateral service trade from deficit to surplus in 2012.

3.2. Internal Structure of Bilateral Service Trade

The bilateral service trade between Hong Kong and Mainland China realized the transformation from deficit to surplus in 2012, but what are the reasons that contribute to this transformation on earth?

From the structure of service import from Mainland China to Hong Kong in Table 1, we can see the proportion which traditional service industry takes up is very large and the proportion which modern service industry accounts for is rather small. In traditional service industry, the proportion of manufacturing service is the maximum which is higher than 50% in recent years; the proportion which tourism service takes up maintains above 10% all the time; transportation service basically is in a rising situation and in 2012, its proportion has already exceeded 10%. The sum of proportion of the three departments mentioned above which takes up in total proportion is 84% in the year of 2012. In modern service industry, finance, electronic reference and other commerce increase, but they still fluctuate in the low position.

Figure 1. General current situation of bilateral service trade.

Table 1. Structural table of bilateral service trade (%).

From the structure of service export from Hong Kong to Mainland China, we can see the proportion which traditional service industry accounts for is still very large and the proportion which modern service industry takes up is very small, but there is difference in structure. In traditional service industry, tourism sees the most significant rising range of proportion, increasing to 71.6% in 2012 from 28.6% of 1998; the proportion of transportation presents obvious downtrend, but in the year of 2012, its proportion maintains 16%, ranking only second to tourism; the proportion which manufacturing service takes up is rather small, which can basically ignore. In modern service industry, the proportion of finance, electronic reference and other commerce of modern service industry increases, but they still fluctuate in low position.

According to the analysis above, the main reasons for the emergence of service trade deficit are that the amount of manufacturing service export from Hong Kong to Mainland China is small while the amount of manufacturing service import from Mainland China from Hong Kong is very large. The decrease in tourism export from Hong Kong to Mainland China is the major reason which prompts the transformation of Hong Kong service trade from deficit to surplus. It is thus clear that traditional service industry plays a significant role in the transformation process while modern service industry plays a minor role.

4. Empirical Test and Result Analysis

From the analyses above, we can see the influence of CEPA on the export and import of bilateral service trade and traditional and modern service industry is inconsistent. In order to verify our speculations, the article below uses the data of industrial service trade of Hong Kong and its principal trade partners between the year of 1998 and 2013 and verifies the influence of CEPA on service trade export from Hong Kong to Mainland China through establishing difference-in-difference model.

4.1. Model Specification

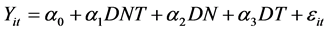

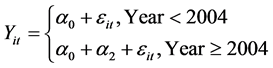

The equation utilizing difference-in-difference to estimate the influence of CEPA on service trade is as follow:

. (1)

. (1)

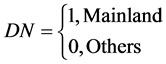

In the Equation (1),  indicates the amount of industrial service trade export of Hong Kong to experimental groups and control groups, and in this equation, i shows service industries of different countries and regions and t shows time. The meaning of dummy variable can be indicated by the following equations:

indicates the amount of industrial service trade export of Hong Kong to experimental groups and control groups, and in this equation, i shows service industries of different countries and regions and t shows time. The meaning of dummy variable can be indicated by the following equations:

(2)

(2)

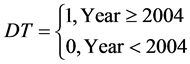

(3)

(3)

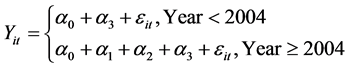

In the Equation (1), the changes of trade volume of experimental groups in two periods before and after the amendment of CEPA are respectively as:

(4)

(4)

In the Equation (4), we can see the difference of trade volume of experimental groups in two periods before and after the implementation of CEPA is , including common effect of CEPA and other factors.

, including common effect of CEPA and other factors.

Similarly, the changes of trade volume of control groups in the two s before and after the implementation of CEPA are respectively as:

(5)

(5)

In the Equation (5), we can see the difference of trade volume of control groups in the two periods is , reflecting the influence of other factors on experimental groups. Thus, the difference of experimental groups minus the difference of control groups is the net impact of the implementation of CEPA on experimental groups.

, reflecting the influence of other factors on experimental groups. Thus, the difference of experimental groups minus the difference of control groups is the net impact of the implementation of CEPA on experimental groups.  is the index of interaction term DNT which is called as the estimator of “difference-in-difference”, reflecting the net impact of the implementation of CEPA on service trade export from Hong Kong to Mainland China, which is the center which the paper pays attention to.

is the index of interaction term DNT which is called as the estimator of “difference-in-difference”, reflecting the net impact of the implementation of CEPA on service trade export from Hong Kong to Mainland China, which is the center which the paper pays attention to.

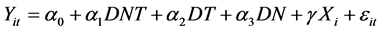

The application of difference-in-difference reduces the necessity of introducing control variable, but there are still some reasons thinking the influence of other factor may not be eliminated. Thus, we expend regression Equation (1) as the following form:

. (6)

. (6)

We will explain some specific practices of this article. This article takes service trade export from Hong Kong to Mainland China as the experimental group and takes service trade export from Hong Kong to other principal trade partners as the corresponding control group. In the CEPA agreement and previous supplementary agreements, most clauses relax the restriction of Mainland China on service industry of Hong Kong. 48 industries which Mainland China is open to Hong Kong contain full service components of Hong Kong service industries, so the service trade export from Hong Kong to Mainland China is affected by CEPA. The regulations of CEPA about the service trade import from Mainland China to Hong Kong only include the aspect of finance, thus CEPA has little influence on service import from Mainland China to Hong Kong, and at the same time, because of availability of data, this article doesn’t carry out difference-in-difference analysis. Therefore, the experimental group in this article is the service trade export from Hong Kong to Mainland China and the service trade export from Hong Kong to other principal trade partners is the control group.

In the aspect of control variable, CEPA has made promises to merchandise trade in goods, service trade and investment facilitation at the same time, so in order to control the possible impact of other two aspects on results, we introduce five control variables: outward foreign direct investment of Hong Kong (S_OutDI), inward direct investment of Hong Kong (S_InDI), import (S_JK), export products of Hong Kong (S_HCK) and carrying trade (S_ZK). In addition, this article uses the practice of Zhang Yingwu (2014) for reference and introduces explanatory variable which is common in gravity model as control variable to control other factors affecting trade. Specifically, represents GDP of Hong Kong; indicates CDP of other countries and regions; indicates the distance between principal trade partners and Hong Kong; language (Clang) is dummy variable and represents whether it has common official language or not. The assignment of Mainland China, America, Britain, Singapore and Chinese Taipei is 1, and the assignment of Japan is 0; dummy variable (Culture) represents whether it has common culture or not. Mainland China, Hong Kong and Chinese Taipei have common culture with an assignment of 1 and the assignment of other countries and regions are 0.

4.2. Source of Data

Figures of test group and control group in this text are all from Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong. Figures of direct outward investment (S_OutDI), inward direct investment (S_InDI), import (S_JK), export of Hong Kong products (S_HCK) and intermediary trade (S_ZK) in the controlled variable are from Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong. GDP figures of Mainland China, Hong Kong (China), America, Japan and Singapore come from National Bureau of Statistics of China, GDP figures of Chinese Taipei are derived from Chinese Taipei Statistical Data Book, and all GDP figures are in US dollars. Data of the distance of Hong Kong to their business partners comes from Google Maps, except straight-line distance of Hong Kong to Guangzhou is used for Mainland China; linear distance of Hong Kong to other business partners is to their capital city. The data of service trade output from Hong Kong to Mainland China are from 48 sections of sub-industries. While the data of service trade output from Hong Kong to other major business partners are from 48 sub-industry sections of 5 countries and areas, which are the USA, UK, Japan, Chinese Taipei and Singapore, according to the ranking of the total output of service trade in Hong Kong in 2013.

4.3. Empirical Analysis

Firstly, in Table 2, let’s see the influences of CEPA upon overall output of service industry from Hong Kong to Mainland China; after the other two policies and other factors affected the trade are controlled, the regression coefficient of DNT estimator by difference-in-difference method is always positive at 5% of significant level. The above result shows that the output of trade in services (all departments) from Hong Kong to Mainland China has averagely increased by 10.7 billion to 10.9 billion Hong Kong dollars per year after CEPA has been implemented and CEPA has significantly promoted the output of trade in services from Hong Kong to Mainland China.

To better analyze the influence of CEPA upon the output of trade in services from Hong Kong to Mainland China, we will individually regress according to the classification of service industry made by the census & statistics department of Hong Kong. Refer to the following Table 3 for regression result.

In the aspect of tourism output, CPEA has greatly promoted the tourism service output from Hong Kong to Mainland China. Hong Kong is a free port with commodities from all over the world at relative lower prices (such as electronic products and cosmetics) because most commodities have no tariff. As the improvement of the living standards of Mainland China residents, under the stimulation of “individual traveling “plans, a large

Table 2. Regression result of the output of trade in services (Million Hong Kong dollar).

Note: the number in the bracket is standard error; *, **, *** respectively denotes 10%, 5% and 1% significance level.

Table 3. The regression result of different industries (Million Hong Kong dollar).

Note: the number in the bracket is standard error; *, **, *** respectively denotes 10%, 5% and 1% significance level.

number of Mainland China residents go to Hong Kong for traveling and shopping, which leads to the proportion of tourism output of Hong Kong in either the absolute scale or all services outputs has substantially increased and the promoting effect of CEPA is significant. According to the data, after CEPA was implemented, the amount of tourists to Hong Kong increased to 48,610,000 in 2012 from 21,810,000 in 2004, which increased 123%. The tourism service output increased to 192.9 billion in 2012 from 34.5 billion in 2003, which increased 5.6 times. The proportion of tourism service output accounted for all services outputs of Hong Kong increased to 71.3% in 2012 from 49.9% in 2003. We can see that CEPA has greatly promoted the tourism service output from Hong Kong to Mainland China.

In aspect of insurance service, CEPA has promoted the insurance service output from Hong Kong to Mainland China but the effect is less [8] . According to the survey result of Hong Kong Monetary Development Authority, the response of Hong Kong insurance companies to CEPA terms is general with following reasons: Firstly, shareholding limit is lower and procedures for examination and approval are still complex; Secondly, as for investment business, the insurance industry in Hong Kong generally consider that Renminbi investment is narrow pipelines especially bonds issued in Renminbi; Thirdly, the threshold for insurance companies entering Mainland China is higher. According to the influences of above reasons, CEPA has small promoting effect to insurance service trade.

In aspect of finance, the coefficient of interaction terms is not significant, which is mainly caused by financial system of Mainland China and opening degree of CEPA terms. The provisions of CEPA on financial aspect are mainly lowering the threshold for Hong Kong financial institutions entering Mainland China, allowing Hong Kong financial professionals to enter Mainland China to operate as well as supporting and encouraging Mainland China financial industry to develop toward Hong Kong, etc. [9] . Specifically speaking, by the end of 2013, there had been 13 banks registered in Hong Kong establishing business in Mainland China with operating over than 440 branches in the local. The data of China Securities Regulatory Commission displays that: there are 185 enterprises are listed abroad, 182 of which are listed in Hong Kong with the market value accounting for 57% of total market value of Hong Kong stocks and the transaction amount accounting for 70% of total transaction amount. We can see that after CEPA is implemented, the financial exchanges of Hong Kong and Mainland China has been widely strengthened but people in Hong Kong industry generally believe that the effect of CEPA in financial field is not as good as expected. The reasons are as follows: Firstly, the opening fields are less; For example, the scope of sub-branch measures is less which restricts the development of banks from Hong Kong in Mainland China and the opening scope of the funds is less. Secondly, the relatively closed financial environment and the strict financial regulations in Mainland China has caused the development of financial industry is not as good as expected [10] .

In the aspect of other business services, the effect of CEPA is not significant. Taking accounting service as an example, CEPA terms mainly include: Firstly, promoting professors from Hong Kong to work in Mainland China; Secondly, mutual recognition of examination, for example realizing mutual exemption of some subjects of CPA examination; Thirdly, developing the agency operation of bookkeeping, allowing the consulting firms established in Mainland China by Hong Kong accountants in accordance with laws to be engaged in bookkeeping business; Allowing qualified Hong Kong accountants to work as the person in charge of agency operation of bookkeeping [11] . As can be seen, the opening to the accounting business mainly concentrates in the flow of professionals and the less regulations on accounting business thus causes the promoting effect of CEPA to be not significant.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Adopting the data of service trades of 48 sub-industries between Hong Kong and its 5 major trading partners from 1998 to 2013, this paper has concluded through descriptive statistical analysis that: service trade output from Hong Kong to Mainland China has been greatly improved after the implementation of CEPA. It also turned into a surplus from a deficit in 2012 and further established the position of Hong Kong as a world trade center and financial center, wherein the output of traditional services like tourism and others has been greatly improved but the proportion of modern service industry is not high.

Through difference-in-difference analysis we conclude that: First, service trade output from Hong Kong to Mainland China has been significantly promoted by CEPA [12] . After the implementation of CEPA, the service trade output from Hong Kong to Mainland China was averagely increased by 10.7 billion Hong Kong dollars to 10.9 billion Hong Kong dollars. Second, in the aspect of transportation service trade, the result was not as good as expected which is mainly determined by the trade terms and trade status between Hong Kong and Mainland China. Third, in the aspect of tourism, CEPA has a great promotion effect. Fourth, in the aspect of insurance, CEPA has promoted the output of insurance services from Hong Kong to Mainland China but the effect is small. Fifth, in the aspect of financial industry and other business service aspects, the promotion effect of CEPA is not significant. Based on the study conclusions of this paper, this paper has proposed the following recommendations to the further development of China’s service trades and CEPA [13] .

Firstly, the recommendations of further improving the opening effect of CEPA. First, under the premise of completely considering the existed differences between Mainland China and Hong Kong in aspects of economic scales, social forms, regulatory environment and others, Mainland China needs to accelerate the construction of legalization international business environment and continues to clean up and amend the laws and regulations for accessing relevant service industries appropriately, improving the detailed rules for the implementation and the supporting policies and measures of all CEPA provisions and at the same time further delegates the authority to examine and approve to lower levels and simplifies approval procedures in order to play the opening policy effect of CEPA. Secondly, Hong Kong shall accelerate the transformation of service industries to high value added sectors while Mainland China shall accelerate the pace of economic structure adjustment; the market size of bilateral trade in services shall be continuously expanded during the process of deepening the deep rooted division of labor of both Hong Kong and Mainland China and the complementary advantages of trade in services [14] . Finally, the advantages of service departments of Hong Kong, such as financial department, legal operation department, insurance department, tax department, accounting department, planning department and consulting department, shall be taken and enterprises from Mainland China and Hong Kong shall be actively guided to join together to “going out” and cooperate to develop international market in ways such as joint investment, joint bidding and joint contracting projects to expand the market space of trades in services of CEPA.

Secondly, advice on reasonable adjustment of CEPA structure. On one hand, Mainland China shall take more proactive measures to enlarge the openness of modern service industries with priority to Hong Kong, such as finance, insurance, medical care, lawyer, and test certification, to expand the potential of cooperation in modern service industries [15] [16] . At present, it is particularly to speed up the implementation of each new measures of financial cooperation listed in the Supplementary Agreement IX in CEPA. For example, to constantly improve the level and quality of the openness to Hong Kong banks; to support Hong Kong insurance companies set up business offices or by equity participation to enter Mainland China market; to support the innovation and development of Hong Kong offshore RMB financial products; to expand the scope of cross-border trade RMB settlement to the whole country; to issue RMB bonds in Hong Kong as a long-term policy arrangements. On the other hand, to further relax the standards of service providers and enrich the content of trade and investment facilitation under the framework of CEPA; meanwhile, Hong Kong service providers should seize the strategic opportunities of Mainland China in the mode of transformation of accelerated expanding domestic demand, the development of the service industry and emerging industries, promotion of urbanization, promotion of scientific and technological progress and innovation, development of resource conservation and environment friendly society, to accelerate the finance, insurance, logistics, advertising, exhibition, accounting, consulting, education modern service sector into Mainland China market, in order to promote the cooperation of the two sides in the modern service industries.

Thirdly, advice on further implementation of CEPA. To speed up the implementation of Framework Agreement on Hong Kong-Guangdong, to further support construction in Hong Kong as the leading financial regional cooperation, to build modern circulation economic circle, to co-construct the Pearl River Delta high-quality life circle, deepen the service industry cooperation between Guangdong and Hong Kong. To promote processing trade transformation and upgrade model area of Pearl River Delta, to support Hong Kong enterprise steady development and transformation and upgrade, in order to deepen business service cooperation of two places [16] . Vigorously push construction of Shenzhen-Hong Kong Cooperation on Modern Service Industries in Qian Hai Area, actively develop innovative financial, modern logistic, information service, technology service and other professional services, giving support on policy implementation, project arrangement, system and mechanism innovation and so on. Taken good use of Shenzhen Qian Hai, Guangzhou Nanshan and Zhuhai Hinging demonstration areas, they will try first to improve the service standard and shifted policy and other areas. Obstacles encountered in the system in view of the individual development of the service industry; both sides of Guangdong and Hong Kong can put forward suggestions on improving the related laws and regulations and policies, to explore experience on the implementation of CEPA.

Cite this paper

ChenYan, (2016) Research about the Influence of CEPA on the Service Trade in Mainland China and Hong Kong. Journal of Service Science and Management,09,36-44. doi: 10.4236/jssm.2016.91005

References

- 1. Zhou, Y.H. (2012) Does CEPA Change the Influence of Trade between Hong Kong and Chinese Mainland on Hong Kong Economic Growth? Statistical Research, 3.

- 2. Zhang, Y.W. and Xu, L.P. (2015) Does CEPA Promote Service Trade between Mainland and Hong Kong? Journal of International Economics, 2.

- 3. Wooton, I. (1986) Preferential Trading Agreements: An Investigation. Journal of International Economics, 21, 81-97.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1996(86)90006-1 - 4. Viner, J. (2014) The Customs Union Issue. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199756124.001.0001 - 5. Trifler (2001) The Long and Short of the Canada-US. Free Trade Agreement. The American Economic Review, 4.

- 6. Sampson, G.P. and Snape, R.H. (2007) Identifying the Issues in Trade in Services. World Economy, 8, 171-182.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.1985.tb00421.x - 7. Robson, P. (1998) The Economics of International Integration. Psychology Press.

- 8. Meade, J.E. (1955) Trade and Welfare. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- 9. Magee, C.S.P. (2008) New Measures of Trade Creation and Trade Diversion. Journal of International Economics, 75, 349–362.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2008.03.006 - 10. Zhang, Y.W. and Xu, L.P. (2014) Does CEPA Promote Service Trade between Mainland and Hong Kong? Journal of International Economics, 2.

- 11. Mao, Y.H. (1985) Comparative Advantage and International Trade and Investment in Services. Trade & Investment in Services Canada/US Perspectives Toronto Ontario Economic Council, 39-71.

- 12. Cai, H.B. (1972) Economies of Scale and Customs Union Theory. The Journal of Political Economy, 465-475.

- 13. Hua, X.H. (2007) Splintering and Disembodiment of Services and Developing Nations. World Economy, 7, 133-144.

- 14. Zhang, J. and Xu, Z.Y. (2007) How Much Should We Trust Difference indifferences Estimates? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 27.

- 15. Luo, N.B. (2006) The Effect of Tax Rebate Policy Change on China’s Exports: An Empirical Analysis. China Economic Quarterly, 10.

- 16. Chen, G.H. (1967) Trade Creation and Trade Diversion in the European Common Market. The Economic Journal, 1-21.