iBusiness

Vol.3 No.3(2011), Article ID:7475,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ib.2011.33035

Generative Mechanisms of Growth of a New High-Tech Firm

![]()

Department of Management, Oulu Business School, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland.

Email: vesa.puhakka@oulu.fi

Received June 13th, 2011; revised July 20th, 2011; accepted August 3rd, 2011.

Keywords: Firm Growth, Generative Mechanism, Growth Model, High-Tech Business

ABSTRACT

In this paper we conduct a review on the studies on firm growth and suggest some criticism towards growth research so far. We address that it could be time to approach firm growth from processual and cross-disciplinary starting point. Based on this assumption we carried out a literature review of the studies on firm growth, entrepreneurship, organizational change and high-tech industry. We identified the following factors to have an impact on the emergence of growth of a new high-tech firm: 1) resources of the firm, 2) firm’s strategic posture, 3) business opportunity, 4) business environment, 5) growth behavior, 6) opportunity exploitation, and 7) outcome of the process. Building on these elements and interaction among them we describe the behavior which we call in this paper as generative mechanisms of growth. We also propose a theoretical framework for studying the emergence of growth of a new high-tech firm.

1. Introduction

Firm growth is regarded as an important key to economic development and growth is at the top of the list in many companies [1,2]. Some companies manage to take temporary spurts of growth but are not able to keep it up. Generating sustained, profitable growth is an important challenge for firms in the current rapidly changing business environments [3,4]. This is especially true in the case of high-technology industries whose technological change is considered to be one of the main drivers of economic growth [5-9]. During the change of the millennium great expectations were placed on the growth potential of new technology-firms [10]. However, technological, competitive and market uncertainty caused many of them to fail and expectations were proven to be too optimistic.

On these grounds it is not surprising that firm growth has attracted a lot of interest among researchers [11,12]. Many theories about the growth of firm have been proposed since Penrose [13] depicted hers but none of them have been widely approved by the academic society [14, 15]. Based on prior research we know about different factors and circumstances that have influence on firm growth but this knowledge is fragmented and limited [16,17].

In this paper we approach this gap in the literature through conducting a short theoretical review on the research of firm growth. From this starting point we analyze the results and shortcomings in the previous research by stressing the emergence of growth in a new high-tech firm context. On the basis of our analysis we gather important theoretical aspects together and use them to build seven theoretical elements constituting the generative mechanisms of growth of a new high-tech firm. By combining these elements we describe the interactions and relations among them and suggest propositions and a theoretical framework for the study of growth.

In the following, we start with an overview of previous research on firm growth approaching it from the viewpoints of generative mechanisms. Second, we discuss high-tech business as context for growth. Third, we introduce propositions and build a conceptual framework for studying growth of high tech firms. Building on these elements we lastly conclude the contribution and implications of study.

2. Growth Research from the Viewpoint of Generative Mechanisms

Growth of entrepreneurial firms has been under the spotlight in a number of studies [11,16,17]. The discussion as a whole can be described as a complex one starting from the point that growth as a multifaceted phenomenon [12] has pulled researchers to make a variety of definitions for growth. Different definitions, in turn, have created a great diversity of studied variables. In the end, there is considerable lack of reliability and comparability of the results and fragmentation of previous research. Zahra, Sapienza and Davidsson [18] conclude that previous research has not provided an empirically based explanation why some firms continually create growth while others do not.

When studying growth it is important to consider the definition of the concept itself [17,19]. Is growth something that can be captured in a causal model and described through different phases and actions [20] or is it something that is emerging and thus possible to understand only as a process [21]? Prior studies on entrepreneurial growth have mostly applied the previous definition with overwhelming use of positivistic, variancebased methods [22]. This kind of research aims at explaining and predicting what happens in a social reality by searching natural law like regularities and causality within research phenomena [23,24]. Therefore, prior research on growth has not taken into account that most events in social world take place in spatiotemporal open systems in which events do not follow a determined and recurrent pattern [25]. This makes it difficult to find general causalities and patterns of growth that would be applicable on a firm level.

To overcome this problem, some recent studies have applied process approach on growth studying different overlapping episodes that are not tied to certain sequence of execution or time in firm’s life-cycle [14,26]. This moves the focus from the static descriptions of growth towards analyses of growth as a spatiotemporal process including generative behavioral practices. Based on this, we claim that studying growth is not only a methodological issue [15] but as well an ontological and epistemological issue how to approach the change and development behavior of human beings [22].

We apply the latter definition of growth stressing the behaviors and attitudes inside the firm and the temporal nature of growth. This way of seeing growth, which significantly differs from the traditional conception, is important because it offers a basis for a real-time study of how and why firms grow. Further, we suggest that the emergence of growth is related to contextual actions emphasizing questions on how something is emerging in a social dialogue [27]. It could be concluded that growth research has started to look new conceptual building blocks based on which it could be redefined. These are proposed here to be processuality of organizations and contextuality of growth.

3. High-Tech as Context for Growth

We have chosen a new high-tech firm as our research subject because of three reasons. Firstly, high-tech industry has grown fast in recent two decades and become an important part of the global economy [28], and many new firms are being established on it. Secondly, it serves as a good example of the post-modern business environment in which change, turbulence, hostility, different uncertainties and technological developments are complicating the operations of firms [24]. High-tech firms must be innovative and put a lot of effort to research and development. To do this successfully they should be able to recognize, sense and interpret different signals from their environment to support their own decision-making. The behavior described later in the paper focuses more on creating different business opportunities for the use of the high-tech firm’s technological know-how because technological skills alone cannot create growth for a new high-tech firm [29].

The capability to create unique customer value rises as an important issue in the competitive and changing high-tech business [10]. Thus, to be able to answer the changing customer needs and to find the opportunities for growth, the new high-tech firm needs to keep its eyes on the customers but also on the coming market and technological trends. Based on this it can be argued that mechanism of organizational learning together with gathering of information is essential when thinking growth from a long-term point of view. Access to valuable information demands broad social and professional networks [10,30], which can be difficult to build in the early phase of the firm without previous experience. Moreover, the new high-tech firm needs managerial capabilities to organize multiple product innovation [31], which is needed for the evaluation and exploitation of perceived business opportunities. This is important because the ability to identify new opportunities is crucial for continued growth [13]. Thirdly, we see that firm behavior is strongly related to its business environment [32], both the business and internal, and therefore it is necessary to study the generative mechanisms of growth in a certain business environment. All the decisions that a firm makes are contingent on the information that is available in the particular business environment.

High-tech business is one of the major drivers of innovation and economic growth [6]. High-tech business, however, is not only about how to commercialize new technologies, but more broadly about the interplay between new technologies and business in which business processes and ways of organizing new ventures are constantly redefined [33]. High-tech business is, therefore, very malleable and there is no single route to growth, but the strategic actions of the involved actors co-produce the outcome [5]. Taken together, high-tech business is not an individual or a firm level process, but rather a process embedded in networks of economic actors and driven by entrepreneurial level action [29].

We propose that this area of research should focus on examining how growth comes into the existence in a dynamic business environment and how the dialogue between technological innovations and new venture creation add new economic value. In the rest of the paper we will present our proposals for such a theoretical framework which could be suitable for studying the generative mechanisms of growth from the basis of emphasizing firm behavior. There are not many studies on firm growth that would argue about the factors behind the growth phenomenon itself.

4. Theoretical Framework of Generative Mechanisms of Growth of a New High-Tech Firm

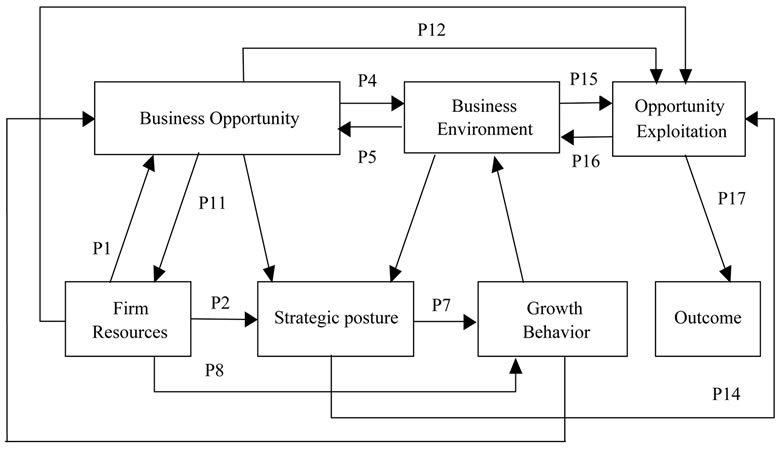

In this part of the paper we present the theoretical elements that constitute the basis for the theoretical framework that is presented later on. The framework constitutes of seven elements: resources, strategic posture, growth behavior, business opportunity, environment, business opportunity exploitation, and the outcome of the process. Theoretical elements are based on prior research on the above-mentioned disciplines of entrepreneurship, organizational change and firm growth. In some cases the theoretical background consists of all three disciplines while in others it is narrower. The benefit in one comprehensive framework is that it also offers more simplified view of the generative mechanisms of growth. Davidsson [34] used the same approach to entrepreneurship literature and more recently Barringer et al. [14] on growth studies but they do not touch particularly about the emergence of growth. There is no such framework with the above-mentioned focus towards growth.

There are two fundamental assumptions that must be stated out before explaining the framework in detail. First of all, we see that the present understanding of entrepreneurship affects strongly in the background of the behavior of the firm. Entrepreneurship can be understood at general level as creation of new business in an existing firm or in the form of a new firm [35]. Thus, entrepreneurship can be seen as the study of “how opportunities to bring into existence future goods and services are discovered and exploited, by whom and with what consequences” [36,37]. Discovery of opportunities relates to identifying of market gaps and possibilities to create new value and exploitation to realization of the opportunity in form of a venture. This suggestively shows the importance of different behaviors of firm in the study of emergence of growth.

Another important aspect in entrepreneurship research is the entrepreneurial orientation. It is strongly linked to motivation towards growth [38]. It can be assumed that if a firm wants to grow, it has to be motivated to seek growth and take growth into account in its decisionmaking and operation [15]. If a firm is not motivated to seek growth then the possibility for growth to happen is smaller. Entrepreneurial orientation illustrates this attitude and it has been noted that there are significant differences among firms in this matter [39]. This brings up the significance of understanding the mental issues and attitudes of a firm in the study of the generative mechanisms of growth of new high-tech firms.

4.1. Propositions

The persons involved in the opportunity recognition phase form a collection of resources, which Penrose [13] already pointed out. At that time firm does not have all the necessary resources but they develop and take shape during the activities [40]. Under these circumstances it is possible to assume that individual characteristics of persons involved play a crucial part in starting up the business and also in compilation of strategic posture. Based on prior studies, characteristics of individuals like prior industry experience in the same industry as current business [41,42], technical and market knowledge [43], educational background [44], broadness of social network [45], and attitude towards change [21] come up. The resources form also the base for business opportunity recognition [34]. On these grounds it is reasonable to postulate the following propositions:

1) Resources of a new high-tech firm have an influence on business opportunity recognition.

2) Resources of a new high-tech firm have an influence on the development of firm’s strategic posture.

The type and novelty of recognized business opportunity [46,47] affect the way how the opportunity will be exploited by the new high-tech firm. Business opportunity is defined to be a situation in which ideas, beliefs and actions to create new economic value become manifested as economic artifacts [47]. Type of opportunity also defines what kinds of other resources, e.g. financing, are needed at this early stage for achieving forthcoming growth [48] and how the resources must be coordinated for creation of core competence [49]. Other important factor is how a firm sees the value innovation [50], which can be seen to be especially important in the high-tech business context where services are coming more essential all the time. The type of opportunity affects as well the firm’s upcoming business environment whose characteristics affect then the opportunity refinement [34]. In addition, changes in the external environment affect the development of firm’s strategic posture. On these grounds the following propositions are presented:

3) The type of business opportunity has an influence on the development of a new high-tech firm’s strategic posture.

4) The type of business opportunity defines the business environment of a new high-tech firm.

5) The business environment has an influence on the exploitation of a business opportunity in a new high-tech firm.

6) The external environment has an influence on the strategic posture of a new high-tech firm.

A firm aligns its usage of resources in the strategy [51] which reflects the level of entrepreneurial orientation in the firm [39] and the importance of seeking growth [50]. These factors influence on time and resources that firm uses to opportunity searching. Resources like managerial capacity [13], motivation [52], technological and market knowledge [43] and also attitude towards change [21] interact with this opportunity searching behavior. Given the studies above the following propositions are presented:

7) The strategic posture defines the importance of seeking growth opportunities in a new high-tech firm.

8) Resources of a new high-tech firm affect the amount of resources allocated to opportunity search.

Entrepreneurs gather information of the business environment’s development on a broad and a narrow scale by investigating products and services on the markets, their distribution channels, competitors, and upcoming trends [53]. Entrepreneurs try to find gaps and niches that are not crowded by competitors but still big enough business wise [54]. They search information through behavior such as environmental scanning [54-56], proactive searching [57-59] and innovative behavior [60,61]. Information through this kind of activities is needed for helping the firm to be able to react or predict environmental changes [62]. Based on the above it is possible to present the following propositions:

9) A new high-tech firm uses growth behavior to search for business opportunities in its environment.

10) A new high-tech firm discovers business opportunities from its environment due to growth behavior.

The type of a business opportunity [46,47] sets demands towards the resources, if the firm decides to exploit the opportunity. Firm might need to acquire new resources [34] if the opportunity demands know-how which the firm does not have at the moment. This highlights the meaning of other resources like social networks. Based on given above it is possible to present following propositions:

11) The exploitation of a business opportunity sets demands for the resources of a new high-tech firm.

12) The type of business opportunity sets demands to the way that a new high-tech firm exploits it.

13) The resources of a new high-tech firm define which opportunities will be exploited.

In the exploitation phase of discovered opportunities the firms strategic thinking is important. It also matters does the firm think mainly through causation or effectuation processes [27], which have an effect on the exploitation process. Additionally, firms’ semi-structures, namely future visions and sequenced steps between projects [31], are important for the outcome of the exploitation process, and therefore for growth also. Based on these statements it is possible to present the following propositions:

14) The strategic vision and strategic posture have an influence on the way that a new high-tech firm exploits opportunities.

15) It is worthwhile for a new high-tech company to observe the environment during the opportunity exploitation.

16) A new high-tech firm should observe the reaction of the environment during the opportunity exploitation.

17) The opportunity exploitation process affects the outcome and the emergence of growth.

4.2. Theoretical Framework

Theoretical elements and the propositions between them form together generative mechanisms of growth of a new high-tech firm. It is possible to suggest that the mechanisms above describe the micro processes that create change and eventually growth of a firm.

In the theoretical framework presented in Figure 1 we aim to describe the generative mechanisms of growth behavior of a new high-tech firm. We assume there to exist an entrepreneurial and motivated mindset for aspiring growth. The main idea is to outline how the entrepreneurship occurs in a high-tech firm, how a high-tech firm recognizes opportunities, what elements lead to exploitation of the opportunity in profitable manner and what kind of behavior and sort of knowledge and skills are needed for growth to take place. We also want to remark that the question is not about acquiring different resources and growing by that way. We stress more the behavior and certain things that could be useful to do with the existing resources or, how to use them in growth creating ways.

5. Conclusions

We have undertaken this study in an attempt to explain what processes constitute the generative mechanisms of growth of a new high-tech firm and how the model of growth builds up in these firms. We proposed that the generative mechanisms of growth could be better

Figure 1. Theoretical framework of generative mechanisms of growth of a new high-tech firm.

explained by trying to understand the different kinds of behaviors of a firm with relation to its environment. We suggested six theoretical elements and their interaction to create an entity which constitutes our view of growth creating behavior. The content of these elements is unique in every firm because it is impossible that two firms or persons could hold exactly same kind of resources, information, and skills [63]. They are all heterogenic in nature [12]. Thus, it is possible to assume that every firm has its own way or model for generating growth. There is not one right answer or model which could describe growth in such a way that it would be right for every company [34].

Growth behavior of a firm can be expressed in many ways because it depends on firm-specific content of the theoretical elements in the framework. Essential thing for a firm is to recognize different mechanisms, like organizational learning, different information gathering behaviors, and to build such an environment where these have been notified. This builds the base and environment where the growth behavior can happen. The behavior occurs relative to firm’s physical and immaterial resources, and they offer many possibilities but at the same time set up constraints to their execution. In this case the growth behavior can mean removing of those constrains or trying to find new possibilities. This highlights the firm’s ability to create and exploit opportunities. They can be taught to be at the core of generative mechanisms of growth. It can be proposed that the theoretical framework illustrates symbiosis between the behavior and resources. The former creates and exploits opportunities and the latter makes them possible to execute.

We contributed to the existing research on firm growth in two particular ways. Firstly, we demonstrated that firm growth is driven by generative mechanisms, i.e. processes through which causal relations come about. Secondly, we pointed out that the generative mechanisms of growth could be better explained by trying to understand the different kinds of behaviors of a firm embedded in its particular context, namely high-tech in this study. This way we suggestively introduced new knowledge on the ways how firm growth is actually accomplished. The results will help researchers and practitioners to further understand the entrepreneurial behavior, dynamism, and episodic nature of firm growth. Furthermore, the results offer insight into understanding more deeply how firms learn and develop new capabilities for creating and sustaining competitiveness in rapidly changing and uncertain business environments.

REFERENCES

- M. Colombo and L. Grilli, “Founders’ Human Capital and the Growth of New Technology-Based Firms: A Competence-Based View,” Research Policy, Vol. 34, No. 6, 2005, pp. 795-816. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2005.03.010

- G. Haour, “Israel, a Powerhouse for Networked Entrepreneurship,” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, Vol. 5, No. 1-2, 2005, pp. 39-48. doi:10.1504/IJEIM.2005.006336

- C. Christensen and M. Raynor, “Innovator’s Solution,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2003.

- K. Weick and K. Sutcliffe, “Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty,” JosseyBass, San Francisco, 2007.

- B. Carlsson and G. Eliasson, “Industrial Dynamics and Endogenous Growth,” Industry and Innovation, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2003, pp. 435-455. doi:10.1080/1366271032000163676

- M. Pohjola, “The New Economy in Growth and Development,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 18, No. 3, 2002, pp. 380-396. doi:10.1093/oxrep/18.3.380

- P. M. Romer, “Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 94, No. 5, 1986, pp. 1002-1037. doi:10.1086/261420

- J. A. Schumpeter, “The Theory of Economic Development,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1934.

- R. M. Solow, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 70, No. 1, 1956, pp. 65-94. doi:10.2307/1884513

- D. J. Hoch, C. R. Roeding, G. Purkert, S. K. Lindner and R. Mueller, “Secrets of High-Tech Success: Management Insights from 100 High-Tech Firms around the World,” Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 1999.

- P. Davidsson and J. Wiklund, “Conceptual and Empirical Challenges in the Study of Firm Growth,” In: D. Sexton and H. Landström, Eds., The Blackwell Handbook of Entrepreneurship, Blackwell, Oxford, 2000, pp. 26-44.

- F. Delmar, P. Davidsson and W. B. Gartner, “Arriving at the High-Growth Firm,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2003, pp. 189-216. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00080-0

- E. T. Penrose, “The Theory of the Growth of the Firm,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1959.

- B. R. Barringer, F. F. Jones and D. O. Neubaum, “A Quantitative Content Analysis of the Characteristics of Rapid-Growth Firms and Their Founders,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 20, No. 5, 2005, pp. 663-687. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.03.004

- P. Davidsson, F. Delmar and J. Wiklund, “Entrepreneurship and the Growth of Firms,” Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, 2006.

- F. Delmar, “Measuring Growth: Methodological Considerations and Empirical Results,” In: R. Donckels and A. Miettinen, Eds., Entrepreneurship and SME Research: On Its Way to the Next Millennium, Aldershot, Brookfield, 1997, pp. 190-216.

- M. Dobbs and R. T. Hamilton, “Small Business Growth: Recent Evidence and New Directions,” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2007, pp. 296-322. doi:10.1108/13552550710780885

- S. Zahra, H. Sapienza and P. Davidsson, “Entrepreneurship and Dynamic Capabilities: A Review, Model and Research Agenda,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2006, pp. 917-955. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00616.x

- A. H. Van de Ven and M. S. Poole, “Explaining Development and Change in Organizations,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1995, pp. 510-540. doi:10.2307/258786

- L. E. Greiner, “Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grow,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 50, No. 4, 1972, pp. 37-45. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6248.1997.00397.x

- H. Tsoukas and R. Chia, “On Organizational Becoming: Rethinking Organizational Change,” Organisation Science, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2002, pp. 567-582. doi:10.1287/orsc.13.5.567.7810

- A. H. Van de Ven and M. S. Poole, “Alternative Approaches for Studying Organizational Change,” Organisation Studies, Vol. 27, No. 11, 2005, pp. 1617-1638. doi:10.1177/0170840605056907

- G. Burrell and G. Morgan, “Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis,” Heinemann, London, 1979.

- A. Rehn, L. Strannegård and K. Tryggestad, “Putting Process through Its Paces,” Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 229-232. doi:10.1016/j.scaman.2007.05.002

- H. Tsoukas, “The Validity of Idiographic Research Explanations,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, No. 4, 1989, pp. 551-561. doi:10.5465/AMR.1989.4308386

- D. Dutta and S. Thornhill, “The Evolution of Growth Intentions: Toward a Cognition-Based Model,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 23, No. 3, 2008, pp. 307-332. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2007.02.003

- S. D. Sarasvathy, “Causation and Effectuation:Toward a Theoretical Shift from Economic Inevitability to Entrepreneurial Contingency,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2001, pp. 243-288. doi:10.2307/259121

- D. G. Messerschmitt and C. Szyperski, “High-Tech Ecosystem: Understanding an Indispensable Technology and Industry,” MIT Press, Cambridge, 2003.

- J. Park, “Opportunity Recognition and Product Innovation in Entrepreneurial Hi-Tech Start-Ups: A New Perspective and Supporting Case Study,” Technovation, Vol. 25, No. 7, 2005, pp. 739-752. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2004.01.006

- B. Johannisson, “Economies of Overview-Guiding the External Growth of Small Firms,” International Small Business Journal, Vol. 9, No. 1, 1990, pp. 32-44.

- S. L. Brown and K. M. Eisenhardt, “The Art of Continuous Change: Linking Complexity Theory and Time-Paced Evolution in Rentlessly Shifting Organizations,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 1, 1997, pp. 1- 34.

- Y.-F. Kuo and C.-W. Yu, “3G Telecommunication Operators’ Challenges and Roles: A Perspective of Mobile Commerce Value Chain,” Technovation, Vol. 26, No. 12, 2006, pp. 1347-1356. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2005.08.004

- E. Carayannis, D. Popescu, C. Sipp and M. Stewart, “Technological Learning for Entrepreneurial Development (TL4ED) in the Knowledge Economy (KE): Case Studies and Lessons Learned,” Technovation, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2006, pp. 419-443.

- P. Davidsson, “A Conceptual Framework for the Study of Entrepreneurship and the Competence to Practice It,” JIBS Working Paper Series, Jönköping University, Jönkö- ping, 2000.

- R. Amit, L. Glosten and E. Muller, “Challenges to Theory Development in Entrepreneurship Research,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 30, No. 5, 1993, pp. 815-834. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.1993.tb00327.x

- S. A. Shane and S. Venkataraman, “The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2000, pp. 217-226. doi:10.2307/259271

- S. Venkataraman, S., “The Distinctive Domain of Entrepreneurship Research: An Editor’s Perspective,” In: J. Katz and R. Brockhaus, Eds., Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth, JAI Press, Greenwich, 1997, pp. 119-138.

- J. Wiklund, “Entrepreneurial Orientation as Predictor of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Performance in Small Firms—Longitudinal Evidence,” In: P. D. Reynolds, W. B. Bygrave, N. M. Carter, S. Manigart, C. M. Mason, G. D. Meyer and K. G. Shaver, Eds., Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson College, Wellesley, 1998, pp. 283-296.

- J. Wiklund and D. Shepherd, “Entrepreneurial Orientation and Small Business Performance: A Configurational Approach,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 20, No 1, 2005, pp. 71-91. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.001

- T. Baker and R. E. Nelson, “Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 50, No. 3, 2005, pp. 329-366. doi:10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329

- I. C. MacMillan and D. L. Day, “Corporate Ventures into Industrial Markets: Dynamics of Aggressive Entry,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1987, pp. 29-39. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(87)90017-6

- R. Siegel, E. Siegel and I. C. MacMillan, “Characteristics Distinguishing High-Growth Ventures,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1993, pp. 169-180. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(93)90018-Z

- E. Autio and A. Lumme, “Does the Innovator Role Affect the Perceived Potential for Growth? Analysis of Four Types of New, Technology-Based Firms,” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1998, pp. 41-54. doi:10.1080/09537329808524303

- A. C. Cooper and F. J. Gimeno-Gascon, “Entrepreneurs, Processes of Founding and New Firm Performance,” In: D. Sexton and J. Kasarda, Eds., The State of the Art in Entrepreneurship, PWS Publishing Co., Boston, 1992, pp. 301-340.

- E. Shaw and S. Conway, “Networking and the Small Firm,” In: S. Carter and D. Jones-Evans Eds., Enterprise and Small Business, Prentice Hall, Harlow, 2000.

- R. Saemundsson and Å Dahlstrand, “How Business Opportunities Constrain Young Technology-Based Firms from Growing into Medium-Sized Firms,” Small Business Economics, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2005, pp. 113-129. doi:10.1007/s11187-003-3803-6

- S. D. Sarasvathy, S. Venkataraman, N. Dew and R. Velamuri, “Three Views of Entrepreneurial Opportunity,” In: Z. J. Acs and D. B. Audretsch, Eds., Handbook of Entrepreneurship, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, 2003, pp. 141-160.

- E. Garnsey, “A Theory of the Early Growth of the Firm,” Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 13, No. 3, 1998, pp. 523-556. doi:10.1093/icc/7.3.523

- G. Hamel and C. K. Prahalad, “The Core Competence of the Corporation,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 68, No. 3, 1990, pp. 79-91.

- W. C. Kim and R. Mauborgne, “Value Innovation: The Strategic Logic of High Growth,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 75, No. 1, 1997, pp. 102-112.

- R. M. Grant, “The Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage: Implications for Strategy Formulation,” California Management Review, Vol. 33, No. 2, 1991, pp. 114-135.

- L. Kolvereid, “Growth Aspirations among Norwegian Entrepreneurs,” Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 7, No. 3, 1992, pp. 209-222. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(92)90027-O

- E. Cadotte and R. Woodruff, “Analysing Market Opportunities for New Ventures,” In: G. Hills, Ed., Marketing and Entrepreneurship: Research Ideas and Opportunities, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1994.

- A. De Koning and D. Muzyka, “The Convergence of Good Ideas: When and How Do Entrepreneurial Managers Recognize Innovative Business Ideas?” In: N. Churchill, W. Bygrave, J. Butler, S. Birley, P. Davidsson, W. Gartner and P. McDougall, Eds., Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson College, Wellesley, 1996.

- F. J. Aguilar, “Scanning the Business Environment,” MacMillan Co., New York, 1967.

- D. Miller, “The Correlates of Entrepreneurship in Three Types of Firms,” Management Science, Vol. 29, No. 7, 1983, pp. 770-791. doi:10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

- P. S. Christensen, O. O. Madsen and R. Peterson, “Conseptualizing Entrepreneurial Opportunity Identification,” In: G. Hills, Ed., Marketing and Entrepreneurship: Research Ideas and Opportunities, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1994.

- A. C. Cooper, “Strategic Management: New Ventures and Small Business,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 14, No. 5, 1981, pp. 39-45. doi:10.1016/0024-6301(81)90006-6

- G. Hills, “Opportunity Recognition by Successful Entrepreneurs: A Pilot Study,” In: M. Hay, W. Bygrave, S. Birley, N. Churchill, R. Keeley and W. Wetzel Jr., Eds., Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson College, Wellesley, 1995.

- [61] B. Gilad, “Entrepreneurship: The Issue of Creativity in the Market Place,” Journal of Creative Behavior, Vol. 18, No. 3, 1984, pp. 151-161.

- [62] R. Peterson, “Creating Contexts for New Ventures in Stagnating Environments,” In: J. Hornaday, E. Shils, J. Timmons and K. Vesper, Eds., Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson College, Wellesley, 1985.

- [63] D. O. McKee, P. R. Varadarajan and W. M. Pride, “Strategic Adaptability and Firm Performance: A MarketContingent Perspective,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 53, No. 3, 1989, pp. 21-35. doi:10.2307/1251340

- [64] F. A. Hayek, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” American Economic Review, Vol. 35, No. 4, 1945, pp. 519-530.