Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.08 No.02(2017), Article ID:74430,17 pages

10.4236/jmp.2017.82017

Accelerated Expansion of Space, Dark Matter, Dark Energy and Big Bang Processes

Auguste Meessen

UCL, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

Copyright © 2017 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: December 3, 2016; Accepted: February 25, 2017; Published: February 28, 2017

ABSTRACT

The accelerated expansion of our universe results from properties of dark matter particles deduced from Space-Time Quantization. This theory accounts for all possible elementary particles by considering a quantum of length a in addition to c and h. It appears that dark matter particles allow for fusion and fission processes. The resulting equilibrium enables the cosmic dark matter gas to produce dark energy in an adaptive way. It keeps the combined matter-energy density at a constant level, even when space is expanding. This accounts for the cosmological constant Λ and the accelerated expansion of space without requiring any negative pressure. The Big Bang is related to G, c, h and a. It started with a “primeval photon” and led to the cosmic matter-antimatter asymmetry as well as inflation.

Keywords:

Accelerated Expansion, Dark Matter, Dark Energy, Space-Time Quantization, Big Bang, Inflation, Matter-Antimatter Asymmetry

1. Introduction

1998 was said to be “a very good year for cosmology” [1] , because of the unexpected discovery that the expansion of our universe is accelerating [2] [3] [4] . It became also clear that our universe contains about 4% of ordinary matter, 23% of Dark Matter (DM) and 73% of Dark Energy (DE). However, the nature of DM and DE, as well as the cause of the accelerated expansion of our universe are still unknown. We show here that these problems are related to one another and to elementary particle physics. The semi-empirical Standard Model calls itself for explanations and has to be completed to account at least for DM particles.

This is possible, by generalizing Relativistic Quantum Mechanics. The value a of the smallest measurable length is unknown, but the resulting theory of Space-Time Quantization (STQ) is logically consistent. Moreover, it is sufficient that , to justify the Standard Model and to complete it in regard to DM particles [5] [6] . Predicted properties of the cosmic DM gas are confirmed by astrophysical observations [7] . Here, we examine other consequences, especially for the accelerated expansion of space and Big Bang processes.

, to justify the Standard Model and to complete it in regard to DM particles [5] [6] . Predicted properties of the cosmic DM gas are confirmed by astrophysical observations [7] . Here, we examine other consequences, especially for the accelerated expansion of space and Big Bang processes.

The idea of an expanding universe arose from realizing that our universe should fatally collapse, since all masses attract one another. Einstein’s theory of General Relativity (GR) revealed that space itself would contract because of gravity. This resulted from the fact that a homogeneous and isotropic universe allows that all measured distances are proportional to the same scale factor. It could be a function  of universal cosmic time. Since our universe seems to be stable, Einstein assumed that gravitational collapse is prevented by another force. He characterized its strength by the cosmological constant Λ. Lemaître realized that Einstein’s equation for

of universal cosmic time. Since our universe seems to be stable, Einstein assumed that gravitational collapse is prevented by another force. He characterized its strength by the cosmological constant Λ. Lemaître realized that Einstein’s equation for  allowed for an expansion of our universe that starts at

allowed for an expansion of our universe that starts at . Although it was then possible to set

. Although it was then possible to set , Lemaître considered that this would be arbitrary. He treated Λ as a parameter of unknown value and showed that the expansion of space would eventually become accelerated when

, Lemaître considered that this would be arbitrary. He treated Λ as a parameter of unknown value and showed that the expansion of space would eventually become accelerated when . This has now been established and suggests that the cosmological constant should be related to DE [8] .

. This has now been established and suggests that the cosmological constant should be related to DE [8] .

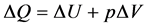

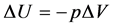

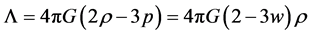

Since the underlying physics is not yet known, the discovery of the accelerated expansion of our universe was very important. It led in 2011 to the Nobel Prize in physics [9] , but also to great perplexity. Where could the required energy come from? Does space contain energy [10] or is it provided by some yet unknown substance? It would then have to be present everywhere in the whole universe and has been called quintessence [11] . This refers to the ancient concept of a fifth element, but requires the existence of some hypothetical field and corresponding particles [12] . Actually, there are various models and scenarios, providing equivalent descriptions [13] , since any fluid that is evenly spread out in the whole universe leads to a cosmological constant . The pressure p of this fluid depends on its mass-energy density

. The pressure p of this fluid depends on its mass-energy density , according to the equation of state

, according to the equation of state  Since

Since , it would be necessary that

, it would be necessary that . The “cosmological constant problem” seems then to be reduced to imagining a substance that has great negative pressure. Actually, it is necessary to determine the real value of Λ by means of measurements and to explain it in a physically coherent way.

. The “cosmological constant problem” seems then to be reduced to imagining a substance that has great negative pressure. Actually, it is necessary to determine the real value of Λ by means of measurements and to explain it in a physically coherent way.

The cosmologist Michael Turner, who coined the term “dark energy” in 1998, stated in 2002 that it is “the causative agent of the current epoch of accelerating expansion”. Since  for matter and

for matter and  for photons, DE is “more energy-like than matter-like… The challenge is to understand it” [14] . He considered that this problem is essential for future developments [15] : “Dark energy is just possibly the most important problem in all physics… As a New Standard Cosmology emerges, a new set of questions arises: What is physics underlying inflation? What is the dark-matter particle? How was the baryon asymmetry produced?… What is the nature of the Dark Energy?… The big challenge for the New Cosmology is making sense of dark energy.”

for photons, DE is “more energy-like than matter-like… The challenge is to understand it” [14] . He considered that this problem is essential for future developments [15] : “Dark energy is just possibly the most important problem in all physics… As a New Standard Cosmology emerges, a new set of questions arises: What is physics underlying inflation? What is the dark-matter particle? How was the baryon asymmetry produced?… What is the nature of the Dark Energy?… The big challenge for the New Cosmology is making sense of dark energy.”

The standard Lambda-Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM) model assumes non-rela- tivistic collision-less DM particles. This yields . However, DM particles do interact with one another [6] [7] [16] . To determine the nature and properties of DM particles and to explain how it is related to DE seems to be of fundamental importance. Actually [17] , “both dark matter and dark energy require extensions of our current understanding of particle physics… The existence of nonbaryonic dark matter implies that there must be new physics beyond the standard model of particle physics.” It has even been stated that the scene may be set for a Kuhnian paradigm shift [18] . The historical context suggests, indeed, that “a new theory will emerge, sooner or later” and that it “will radically change our vision of the world” [10] . Since STQ generalizes present-day theories and determines essential properties of DM particles, it is necessary to explore its possible consequences in regard to DE and the accelerated expansion of space. We try to do that by expressing relevant ideas as simply as possible.

. However, DM particles do interact with one another [6] [7] [16] . To determine the nature and properties of DM particles and to explain how it is related to DE seems to be of fundamental importance. Actually [17] , “both dark matter and dark energy require extensions of our current understanding of particle physics… The existence of nonbaryonic dark matter implies that there must be new physics beyond the standard model of particle physics.” It has even been stated that the scene may be set for a Kuhnian paradigm shift [18] . The historical context suggests, indeed, that “a new theory will emerge, sooner or later” and that it “will radically change our vision of the world” [10] . Since STQ generalizes present-day theories and determines essential properties of DM particles, it is necessary to explore its possible consequences in regard to DE and the accelerated expansion of space. We try to do that by expressing relevant ideas as simply as possible.

In Section 2, we begin with a review of the evolution of ideas concerning the expansion of space, to locate the basic problem before proposing a new solution. It replaces the conventional model of DM and DE by another one, based on the theory of STQ and the resulting properties of DM particles. They allow for fusion and fission processes. This accounts for the production of DE and the accelerated expansion of space. Section 3 recalls some basic results of STQ, to prepare Section 4. It relates the Big Bang to particle physics. Section 5 summarizes results and raises some new questions.

2. The Accelerated Expansion of Space

2.1. The Cosmological Constant

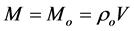

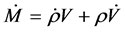

The basic problem results from the fact that masses can only attract one another. Newton postulated that these forces are everywhere identical in the whole universe. Their strength is determined by the constant G and they vanish for great separations of the interacting masses, but they are additive. The astronomer Hugo von Seeliger noted in 1895 that this leads to an inconsistency [19] . It is reasonable, indeed, to assume that the average mass density ρ is everywhere identical in the whole universe. A very large sphere of radius r would thus contain a mass , where

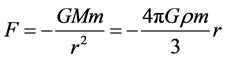

, where . Any object of mass m that is situated on the surface of this sphere is then attracted towards its center by the force

. Any object of mass m that is situated on the surface of this sphere is then attracted towards its center by the force

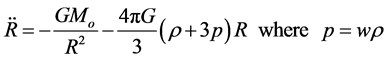

Because of the large-scale homogeneity of our universe, the center of this sphere can be arbitrarily chosen. The whole universe should thus collapse. According to classical mechanics, this would even happen with respect to absolute space. However, Einstein realized in 1905 that space and time can only be defined in terms of possible results of measurement, since the velocity c is a universal constant. His theory of Special Relativity (SR) disclosed that mass and energy are equivalent. From now on, we consider thus that ρ defines a mass-energy density (c = 1). Einstein became also aware of the fact that gravitational forces can be replaced by accelerations of the chosen reference frame. His theory of General Relativity (GR) related thus gravitational forces to the local metric of space and time.

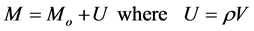

This theory was published in 1915 and in 1917, Einstein applied the new concept of gravity to the whole universe [20] . Because of the cosmological principle, stating that our universe is everywhere identical at sufficiently large scales, the coupled equations of GR were reduced to a single one. It can be established in a more direct and conceptually simpler way, by considering again a very large sphere of volume . Its mass-energy content

. Its mass-energy content

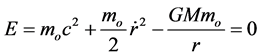

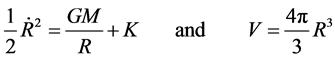

We consider the case where the kinetic energy is small compared to the rest energy, since this is possible and will be sufficient. The negative potential energy accounts for gravitational attraction towards the center of the sphere. We set

K is a constant. The theory of GR yields the same result, but K depends then on the curvature of space. Einstein considered a closed space of constant curvature, as for the surface of a hypersphere. K is then positive, but would be negative for an open, hyperbolic space. The intermediate “flat” space yields Euclidean geometry and

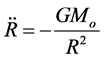

Considering only ordinary matter, distributed with the same mass-energy density

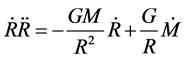

This means that even the new theory of gravity cannot prevent gravitational collapse. The acceleration is greater for small values of R, because of stronger forces. However, it is now attributed to variations of the scale factor

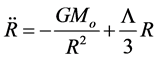

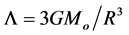

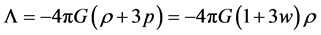

The so-called “cosmological constant” Λ can be viewed as defining the strength of a repulsive force that would be opposed to gravity at cosmological scales. It should be noted that (5) results from (3), when we assume that

Willem de Sitter noted already in 1917 that variations of

Lemaître published this theory in 1927 [21] and republished it in 1931 [22] . He translated himself the text from French to English, but dropped some minor parts and added another text. Lemaître insisted always on the assumption that our universe is homogeneous, but his most brilliant idea was that

In 1927, Lemaître had transmitted the initial paper to Einstein, before they met at the fifth Solvay Conference in Brussels. Einstein accepted the mathematical treatment of Equation (5), but rejected the idea of an expanding universe. He thought that such a bold interpretation of (5) is not plausible. He told Lemaître about similar work of Alexander Friedmann, who had studied mathematical physics and published in German. Friedmann considered also a function

Lemaître ignored this work in 1927. Since he studied engineering, he was concerned with the real world and considered the problem of a possible variation of

The term “Big Bang” was introduced by Hoyle in 1949, to ridicule this idea. He preferred a “steady state” cosmology to the concept of a universe that emerged from a single point and could even blow-up when the cosmological constant

Today, we know that the Big Bang occurred about 17.8 billion years ago and that the accelerated expansion of space began about 5 billion years ago. Thus

2.2. The Conventional DM and DE Model

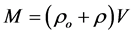

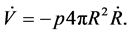

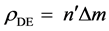

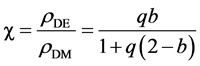

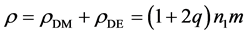

We can assume that DM and DE are substances that have together a mass- energy density

We have thus to determine the value of

This is equivalent to (5) when the cosmological constant

Since

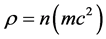

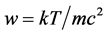

We showed that DM particles interact with one another by exchanging N2 bosons and that this does usually lead to elastic scattering [6] . The cosmic DM gas behaves then like a usual molecular gas. The actual nature and mass of DM particles are irrelevant here. Their average kinetic energy would be

2.3. The Model of Adaptive DM and DE

Since

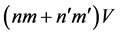

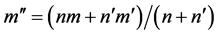

This may seem to be unbelievable, since it requires that DM and DE have the capacity to keep their mass-energy density

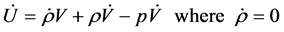

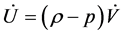

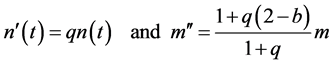

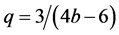

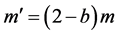

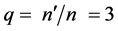

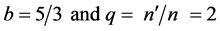

This yields

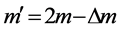

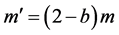

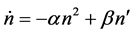

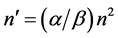

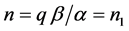

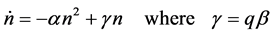

The density n would remain constant when

To verify if this equilibrium is stable, we consider a local perturbation for constant values of the parameters

The rate Equation (11) is then reduced to

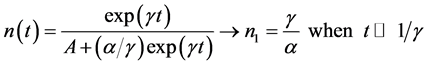

Setting

The constant A is determined by

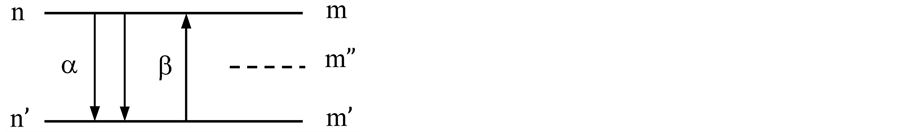

Figure 1. Fusion and fission processes of DM particles yield an equilibrium that accounts for the accelerated expansion of space.

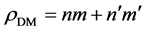

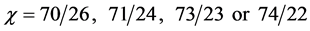

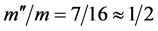

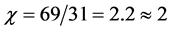

According to reported values of

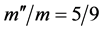

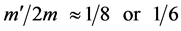

It also appears that fusion of DM particles would be characterized by a high binding energy, so that

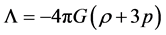

The accelerated expansion of space is due to the adaptability of the cosmic DM gas. When the volume V increases, fusion and fission processes continue to equilibrate one another by producing more DM and more DE. Since DM particles are electrically neutral, they cannot produce photons and they are not heated or cooled by contact with ordinary matter [6] . Invisible cosmic DM gas is thus isothermal in the whole universe. Even when space is expanding, its density and temperature is regulated everywhere by mutually controlled fusion and fission processes. Thermal agitation leads to pressure effects. They are important for the constitutions of DM atmospheres [7] , but nearly negligible for the accelerated expansion of space. By measuring Λ, we could determine the average mass-energy density ρ.

Einstein’s conjecture (5) was very remarkable, since the existence of DM and DE was totally unknown. The conjecture that the scale factor

3. Space-Time Quantization

3.1. The Positive Energy Content of Our Universe

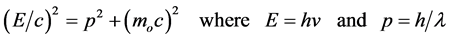

To prepare the following chapter, we present some essential consequences of the theory of STQ in a short and different way. The basic idea was that Nature could impose a third restriction in addition to those which led to the development of relativity and quantum mechanics. In a nutshell, they are summarized by Einstein’s energy momentum relation and de Broglie’s redefinition of

The function

The value of a is thus determined by the highest possible momentum

3.2. All Possible Elementary Particles

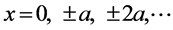

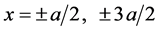

They can be distinguished from one another by means of their wave functions when the quantum of length

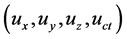

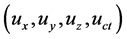

Such a modulation of wave functions is possible for any reference frame in our four-dimensional space-time. This yields four quantum numbers

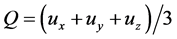

The electric charge is always determined (in units e) by

The Standard Model is not complete, since the u-quantum numbers are not only equal 0 or ±1, but also to ±2, for instance. Moreover, there are states of type

3.3. Conservation Laws for Possible Transformations

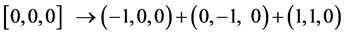

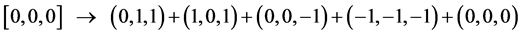

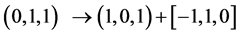

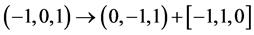

Elementary particles can be transformed into one another by means of annihilation and creation processes. However, the sum of u-quantum numbers has to be conserved for every one of the four space-time axes, as well for bosons as for fermions. This accounts for the fact that a quark can change its color by creating or annihilating a gluon. For instance,

All compound particles have to be “color neural”. This means that the three spatial reference axes have to be involved with the same probability. Nucleons are thus constituted of 3 quarks in R, G and B color states. Narks can constitute a greater variety of compound particles. We called them “neutralons”, since they are electrically neutral. Nucleons interact with one another by exchanging π mesons, while neutralons interact with one another by exchanging N2 bosons [6] . The cosmic DM gas is composed of neutralons and compound neutral particles. They interact most frequently by elastic scattering, which leads to pressure effects and explains astrophysical observations [7] . DM particles allow also for fusion and fission processes. They are important for cosmology, but STQ has also other consequences.

4. Big Bang Processes

4.1. The Primeval Photon

Georges Lemaître justified the idea of an expansion of space, starting at

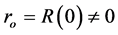

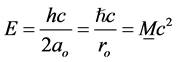

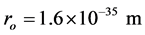

The primeval photon had even to be in a quantum mechanical state where all orientations of its momentum vector were equally probable. Their magnitude was defined by

The primeval photon was confined by gravity on the surface of the hypersphere of radius

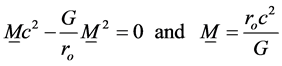

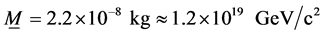

By combining (18) and (19), we see that the initial radius

This yields

4.2. The Matter-Antimatter Asymmetry

According to STQ any particle state

This would respectively correspond to the production of a neutron, combining

Elementary particles of the first generation were most frequently produced, since they have lower energies. They had also the greatest chance to survive. Moreover, quarks in R, G and B color states had to be created with equal probabilities, since the 3 spatial reference axes are physically equivalent. DM particles could not be directly created by the primeval photon, but any quark can create a gluon, by changing color. This gluon is annihilated by other quarks or creates two narks in other color states. This allowed for the creation of a compatible ensemble of narks, participating in the general particle-antiparticle asymmetry [6] .

We can also explain why the Big Bang “opted” for particles instead of antiparticles. Their production would have been equally probable, but that does not imply simultaneity. Once the primeval photon started to be transformed into so- called “particles”, this process was immediately amplified by stimulated emission. Einstein discovered this process in 1917, when he tried to explain Planck’s law for the frequency distribution of black body radiation. Emission of photons can be spontaneous, but also stimulated by the presence of other photons of the adequate type. In quantum mechanics, this is justified by means of great intensities of quantized fields and would also apply to material particles.

4.3. The Initial Inflation

The Big Bang was triggered by the transformation of the primeval photon into quarks and narks. Since they are spin-

Science progresses by successive approximations. Lemaître solved Equation (5) and developed the concept of an expanding universe by adopting the simplest possible hypothesis:

5. Conclusions

Initially, we wanted only to find out if space and time are continuous or not. It appeared that Space-Time Quantization (STQ) is possible and accounts for elementary particle physics [6] . This theory applies also to DM particles and we showed here that they account for the accelerated expansion of space. This results from fusion and fission of DM particles. They liberate and require energy in such a way that the common mass-energy density remains constant, even when space is expanding.

The conventional model called for strong negative pressure. They cannot be justified by elastic collisions of DM particles and are not necessary to account for the cosmological constant Λ and the resulting accelerated expansion of space. It is also possible to account for Big Bang processes and to prove that the initial value

It should be noted that the reality of STQ is justified by many remarkable empirical observations, summarized by the Standard Model of elementary particle physics [6] . STQ leads also to the concept of pressure for the cosmic DM gas, which is confirmed by astrophysical observations [7] . STQ accounts even for cosmological processes, but many new questions are emerging. It is necessary, for instance, to clarify the mechanism of fission and fusion processes. Observations of the evolution of Λ and the masses of DM particles in galactic halos may be helpful. This will eventually lead to the development of DM physics, partially similar to nuclear physics. At least DM-electron interactions allowed already for direct detection of DM particles [7] , but we are only beginning to unravel the mysteries of the dark sector of our universe.

Instead of worrying about the ultimate fate of our universe, we have to realize that its accelerated expansion cannot continue forever. This would imply an unphysical divergence, which can only result from an approximation. Actually, the accelerated expansion cannot exceed the capacity of DM to generate more DM. It depends on the transition probabilities α and β, as well as the parameter q. Since fusion of DM particles constitutes an energy source, at least in the form of creating more DM particles, we may wonder if it can be harnessed. At first sight, this seems to be impossible, since they are electrically neutral, but creation of hybrid particles is not excluded [6] . Could much older ET civilizations be using this energy source for interstellar space travel? Anyway, the essential conclusion of this article is that the validity of STQ is confirmed by applying it to cosmology. The intimate connection between cosmology and elementary particle is strengthened and invites to challenging research.

Cite this paper

Meessen, A. (2017) Accelerated Expansion of Space, Dark Matter, Dark Energy and Big Bang Pro- cesses. Journal of Modern Physics, 8, 251- 267. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2017.82017

References

- 1. Turner, M.S. (1999) Dark Matter and Dark Energy in the Universe, ASP Conf.

http://cds.cern.ch/record/372618/files/9811454.pdf - 2. Riess, A.G., et al. (1998) The Astronomical Journal, 116, 1009-1038.

https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/9805201 - 3. Perlmutter, S., et al. (1999) The Astrophysical Journal, 517, 565-586.

https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/9812133 - 4. Tonry, J.L., et al. (2003) The Astrophysical Journal, 594, 1-24.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/astro-ph/0305008.pdf - 5. Meessen, A. (2011) Space-Time Quantization, Elementary Particles and Dark Matter.

http://arxiv.org/abs/1108.4883 - 6. Meessen, A. (2017) Journal of Modern Physics, 8, 35-56.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2017.81004 - 7. Meessen, A. (2017) Journal of Modern Physics, 8, 268-298.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2017.82018 - 8. Peebles, P.J.E. and Ratra, B. (2003) The Cosmological Constant and Dark Energy, RMP. 75, 559-606.

https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0207347 - 9. Kungl. Wetenskaps Akademien (2011) The Accelerating Universe, Scientific Background on the Nobel Prize in Physics.

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2011/advanced-physicsprize2011.pdf - 10. Elizalde, E. (2012) Chapter 1: Cosmological Constant and Dark Energy: HistoricalInsight, In: Olmo, G.L., Ed., Open Questions in Cosmology, InTech, 1-30.

http://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs-wm/41230.pdf - 11. Steinhardt, P.J. (2011) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A, 361, 2497-2513.

http://physics.princeton.edu/~steinh/steinhardt.pdf - 12. Tsujikawa, S. (2013) Classical and Quantum Gravity, 30, Article ID: 214003.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1304.1961v2.pdf - 13. Bamba, K., et al. (2012) Astrophysics and Space Science, 342, 155-228.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1205.3421.pdf - 14. Turner, M.S. (2002) Dark Matter and Dark Energy: The Critical Questions.

http://arxiv.org/pdf/astro-ph/0207297.pdf - 15. Turner, M. (2001) Dark Energy and the New Cosmology.

https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0108103 - 16. Spergel, D.N. and Steinhardt, P.J. (2000) Observational Evidence for Self-Inte-racting Cold Dark Matter.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/astro-ph/9909386v2.pdf - 17. Spergel, D.N. (2015) Science, 347, 1100-1102.

https://inspirehep.net/record/1361841/references - 18. Horvath, J.E. (2009) Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, 5 287-303.

https://arxiv.org/abs/0809.2839 - 19. Von Seeliger, H. (1895) Astronomische Nachrichten, 137, 130-136.

- 20. Einstein, A. (1917) Sitzungsberichte der K öniglich Preubischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1, 142-152.

- 21. Lemaître, G. (1927) Annales de la Soci ét é Scientifique de Bruxelles, 47A, 49-59.

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1927ASSB...47...49L - 22. Lemaître, G. (1931) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 91, 483-490.

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1931MNRAS..91..483L - 23. Lemaître, G. (1931) Letters to Nature, 127, 706,

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v127/n3210/full/127706b0.html - 24. Friedman, A. (1922) Zeitschrift für Physik, 10, 377-386.

http://www.ymambrini.com/My_World/History_files/Friedman_1922.pdf - 25. Slipher, V. (1913) Lowell Observatory Bulletin, 1, 56-57.

http://www.roe.ac.uk/~jap/slipher/slipher_1913.pdf - 26. Hubble, E. (1929) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 15, 168-173.

http://www.pnas.org/content/15/3/168.full.pdf - 27. Lema ître, G. (1949) The Cosmological Constant. In: Schilpp, Ed., Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist II, Harper Torch, New York, 437-456.

- 28. Scolnic, D. (2014) The Astrophysical Journal, 795, 45.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1310.3824v2.pdf - 29. Riess, A.G., et al. (2016) The Astrophysical Journal, 826, 56R.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1604.01424 - 30. Planck Collaboration (2016) Astronomy & Astrophysics, 594, A13.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1502.01589v3.pdf - 31. Weinstein, G. (2013) George Gamow and Albert Einstein: Did Einstein Say That the Cosmological Constant Was the “Biggest Blunder” He Ever Made in His Life?

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1310/1310.1033.pdf - 32. Luminet, J.P. (2014) Georges Lemaître: The Scientist Lemaître’s Big Bang (Slide 25/29).

https://fys.kuleuven.be/ster/meetings/lemaitre/lemaitre-luminet.pdf - 33. Lemaître, G. (1946) L’Hypothése de l’atomeprimitif: Essai de cosmogonie. Griffon & Dunod.

- 34. Guth, A.H. (1997) The Inflationary Universe: The Quest for a New Theory of Cosmic Origins, Jonathan Cape.