Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.06 No.14(2015), Article ID:61115,14 pages

10.4236/jmp.2015.614208

Model and Statistical Analysis of the Motion of a Tired Random Walker in Continuum

Muktish Acharyya

Department of Physics, Presidency University, Calcutta, India

Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 14 October 2015; accepted 13 November 2015; published 16 November 2015

ABSTRACT

The model of a tired random walker, whose jump-length decays exponentially in time, is proposed and the motion of such a tired random walker is studied systematically in one-, two- and three- dimensional continuum. In all cases, the diffusive nature of walker breaks down due to tiring which is quite obvious. In one-dimension, the distribution of the displacement of a tired walker remains Gaussian (as observed in normal walker) with reduced width. In two and three dimensions, the probability distribution of displacement becomes nonmonotonic and unimodal. The most probable displacement and the deviation reduce as the tiring factor increases. The probability of return of a tired walker decreases as the tiring factor increases in one and two dimensions. However, in three dimensions, it is found that the probability of return is almost insensitive to the tiring factor. The probability distributions of first return time of a tired random walker do not show the scale invariance as observed for a normal walker in continuum. The exponents, of such power law distributions of first return time, in all three dimensions are estimated for normal walker. The exit probability and the probability distribution of first passage time are found in all three dimensions. A few results are compared with available analytical calculations for normal walker.

Keywords:

Return Probability, Exit Probability, First Passage Time

1. Introduction

In statistical physics, process of polymerization [1] [2] , diffusion [3] in restricted geometry etc. are some classic phenomena, which have drawn much attention of the researcher in last few decades. The underlying mechanism of such physical phenomena is tried to explain by random walk [4] . Different types of random walk are studied on the lattice in different dimensions by the method of computer simulation. The absorbing phase transition in a conserved lattice gas with random neighbour particle hopping is studied [5] . Quenched averages for self avoid- ing walks on random lattices [6] , asymptotic shape of the region visited by an Eulerian walker [7] , linear and branched avalanches are studied in self avoiding random walks [8] ; effects of quenching are studied in quantum random walk recently [9] . The drift and trapping in biased diffusion on disordered lattices are also studied [10] .

Very recently, some more interesting results on random walk were reported. The average number of distinct sites visited by a random walker on the random graph [11] , statistics of first passage time of the Browian motion, conditioned by maximum value of area [12] are studied recently. It may be mentioned here that the first passage time in complex scale invariant media was studied [13] . The theory of mean first passage time for jump pro- cesses is developed [14] and verified by applying in Levy flights and fractional Brownian motion. The statistics of the gap and time interval between the highest positions of a Markovian one dimensional random walker [15] , the universal statistics of longest lasting records of random walks and Levy flights are also studied [16] .

The random walks in continuum are studied to model real life problems. The exact solution of a Brownian inchworm model and self-propulsion was also studied [17] ; theory of continuum random walks and application in chemotaxis was developed [18] . Random walks in continuum were also studied for diffusion and reaction in catalyst [19] . Very recently, the random walk in continuum is studied with uniformly distributed random size of flight [20] . The statistics of Pearson walk are studied [21] [22] in two dimensions for shrinking stepsize and found a transition of the endpoint distribution by varying the initial stepsize.

The living random walker in continuum gradually becomes tired as the time passes, in reality. This would reduce its energy, as a result the size of flight gets reduced gradually with time. The first-passage properties [23] of a walker are important in various aspects, namely, the fluorescence quenching in which a fluoresecent mole- cule stops while reacting with a quencher, firing neurons when the fluctuating voltage level first reaches a speci- fied value, in econophysics, the execution of buy/sale orders when a stock price first reaches a threshold. What will be the first passage properties if the stepsize of a Pearson walker decreases exponentially in time? In this paper, addressing this particular problem, a model of tired random walker is proposed in continuum and statistics of its motion are studied systematically in one-, two- and three-dimensional continuum. The first passage properties, return and exit probabilities are studied here. The numerical results of detailed statistical analysis of the motion of a tired random walker are also reported here. This paper is organised as follows: In the next section (Section 2) the model of tired random walk is proposed and the results obtained from numerical simulations are given. The paper ends with a summary given in Section 3.

2. Model and Results

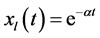

Generally, the motion of a random walker is studied by considering the time (t) independent size (R) of flight in each move. In this study, the model of a tired random walker is proposed in such a way that the size of flight of a walker decreases exponentially as . A simple logic behind it may be stated as follows: if a living cell is moving continuously, its energy (basically kinetic energy) gradually decreases and hence the velocity, which in turn reduces its size of flight (i.e., jump-length per unit time). Here,

. A simple logic behind it may be stated as follows: if a living cell is moving continuously, its energy (basically kinetic energy) gradually decreases and hence the velocity, which in turn reduces its size of flight (i.e., jump-length per unit time). Here,  is tiring factor. The statistical behaviour of such a tired random walker is studied in one-, two- and three-dimensional continuum. It may be noted here that such kind of behaviour of a tired random walker cannot be studied on the lattice.

is tiring factor. The statistical behaviour of such a tired random walker is studied in one-, two- and three-dimensional continuum. It may be noted here that such kind of behaviour of a tired random walker cannot be studied on the lattice.

In one dimension, the size of flight in each time step is . A walker starts its journey from the origin having the equal probability of choosing the left and right direction. The updating rule, in one dimem- sional tired walk, may be expressed as:

. A walker starts its journey from the origin having the equal probability of choosing the left and right direction. The updating rule, in one dimem- sional tired walk, may be expressed as:

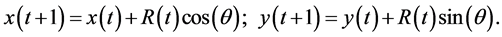

In two dimensions (planar continuum), the tired walker starts its journey from the origin and it has a uniform probability of choosing any random direction (θ) distributed between 0 and . Its motion can be represented mathematically as:

. Its motion can be represented mathematically as:

(1)

(1)

The displacement at time t is . In planar continuum, the area of the region visited by a tired walker is obviously shorter than that visted by a normal walker, in a specified course of time. A typical such comparison is shown in Figure 1 with α = 0.001. As a result, the mean square displacement does not show diffusive behaviour as shown by a normal walker. In long time, it gets saturated (motion stops practically).

. In planar continuum, the area of the region visited by a tired walker is obviously shorter than that visted by a normal walker, in a specified course of time. A typical such comparison is shown in Figure 1 with α = 0.001. As a result, the mean square displacement does not show diffusive behaviour as shown by a normal walker. In long time, it gets saturated (motion stops practically).

A typical such comparison is shown in Figure 2 for α = 0.001 and α = 0.0005. The similar behaviours are also observed in one and three dimensions (not shown). The tired walk is not diffusive  as observed in normal

as observed in normal  walk. It is also observed that the motion stops earlier if the tiring factor α increases.

walk. It is also observed that the motion stops earlier if the tiring factor α increases.

Figure 1. A sample random walk in 2D continuum. The top one shows a walk for  and the bottom one shows a tired walk for

and the bottom one shows a tired walk for . Here, in both figures same sequence of random numbers are used. Note the scales of the axes of two figures.

. Here, in both figures same sequence of random numbers are used. Note the scales of the axes of two figures.  in both cases.

in both cases.

Now, let it be discussed systematically in one, two and three dimensions. In one dimensions, the probability distribution of the displacements of a walker are studied for  (normal), 0.001(moderately tired) and 0.01(heavily tired). As usual, the distribution is normal (Gaussian) with zero mean in all the cases. However, as the tiring factor increases the distribution becomes sharper and sharper. These are depicted in Figure 3. Here, it may be mentioned that the values of α and the maximum time allowed

(normal), 0.001(moderately tired) and 0.01(heavily tired). As usual, the distribution is normal (Gaussian) with zero mean in all the cases. However, as the tiring factor increases the distribution becomes sharper and sharper. These are depicted in Figure 3. Here, it may be mentioned that the values of α and the maximum time allowed  are such that the walker gets frozen (due to exponential decrease of step-size after such long time). The distribution shown in Figure 3, is practically the density distribution of frozen walker. It would be interesting to study the density distribution of these frozen walker as a function of

are such that the walker gets frozen (due to exponential decrease of step-size after such long time). The distribution shown in Figure 3, is practically the density distribution of frozen walker. It would be interesting to study the density distribution of these frozen walker as a function of

What will be the probability of return

Figure 2. The mean square displacement

Figure 3. The distribution

[24] in one dimensional normal random walk. It may be noted here that for α = 0, the walker returns at origin (the starting point also) and the probability of return can be compared to that obtained in random walk on one dimensional lattice. As the tiring factor increases, PR decreases. For moderately tired

How long a tired walker takes to return first time within returing zone? How does the distribution of this first returning time

Figure 4. Probability of return (PR) plotted against the maxi- mum time Nt in one dimension. Different symbols correspond to different values of

Figure 5. Probability of return (PR) plotted against the absolute distance rz of returning zone

walker is shown in Figure 6. A normal walker

In one dimension, how long

bability to escape through a given point (say

Figure 6. Probability distribution

Figure 7. Probability distribution

limit

What is the probability of exit

In two dimensions, the motion of a tired random walker is studied by using the rule given in Equation (1). Here, the mean square displacement

The distribution of absolute displacement is nonmonotonic unimodal function. It is shown in Figure 9. It is observed that the maximum probability of finding the walker at a distance

What will be the probability of return

For a fixed value of

Here, like in one dimensional tired walker, the probability distribution of first returning time

lation of

In two dimensions, the distribution of first passage time (for a fixed distance re = 25.0), is studied for different values of α and shown in Figure 13. As the α increases, the most probable first passage time and mean first

Figure 8. Exit probability Pe plotted against re in one dimension. Different symbols correspond to different values of α. α = 0.0 (o),

Figure 9. The distribution of displacements (r) of a tired random walker in two dimensions. (o) represents

Figure 10. Probability of return

passage time decreases.

The exit probability (for a fixed time of observation

The tired walk in three dimensional continuum can also be generalized. The updating of coordinates obey the following rule:

where

Figure 11. Probability of return

Figure 12. Probability distribution

random angle between 0 and

In 3D continuum, the motion of a tired random walker is studied by using the rule given in Equation (2). Here, the mean square displacement

shown). However, a tired

The probability distribution of absolute displacement (or the density distribution of frozen walker in reality) in 3D continuum is observed to be a nonmonotonic unimodal function. It is shown in Figure 15. It is observed that the maximum probability of finding the walker at a distance

What will be the probability of return in 3D continuum? The probability of return within a sphere of return having radius

Figure 13. Probability distribution

Figure 14. Exit probability Pe plotted against re in two dimensions. Diffe- rent symbols correspond to different values of α. α = 0.0 (o), α = 0.001 (g) and α = 0.01 (*). Here,

For a fixed value of

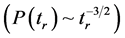

In 3D continuum, the probability distribution of first returning time

diction

In three dimensions, the distribution of first passage time (for a fixed distance

The exit probability (for a fixed time of observation Nt) from a spherical zone of radius re (measured from the origin) is also studied, in two dimensions, as a function of

Figure 15. The distribution of the displacements of a tired random walker in three dimensions. (o) represents α = 0.0,

Figure 16. Probability of return (PR) versus Nt in three dimensions. Diffe- rent symbols correspond to different values of α. α = 0.0 (o), α = 0.001 (,) and α = 0.01 (*). Here in all cases Ns = 105. The radius of spherical re- turning zone is rz = 0.5.

Figure 17. Probability of return (PR) versus rz in three dimensions. Diffe- rent symbols correspond to different values of α. α = 0.0 (o), α = 0.001 (,) and α = 0.01 (*).

Figure 18. Probability distribution

Figure 19. Probability distribution

Figure 20. Exit probability Pe plotted against re in three dimensions. Diffe- rent symbols correspond to different values of α. α = 0.0 (o), α = 0.001 (g) and α = 0.01 (*). Here,

3. Summary

In this article, a model of tired random walker in continuum is proposed. Generally, a random walker moves with constant size of flight. However, as the time passes, if the walker gets tired, one should think of a time dependent size of flight. Here, this size of flight decays exponentially with time. The motion of such a tired walker is studied in one-, two- and three-dimensional continuum. In this statistical investigation, the distribution of the absolute displacement, mean displacement, probability of return (within a specified zone), distribution of time of first return are studied systematically. In one- and two-dimensional continuum, the probability of return decreases as the tiring factor increases. However, in three-dimensional continuum, this probability of return seems to be independent of the tiring factor. The distribution of first returning time in all dimensions (for normal walker with tiring factor α = 0), shows power law behaviours. This scale invariance of the distribution of first returning time breaks down for

The exit probability and the distribution of first passage time are studied. In all dimensions, the exit pro- bability is found to decrease as the size of the zone (from where the tired walker exits out) increases. The rate of decrease of the exit probability was found to increase as the tiring factor α increases. Here also the probability of first passage (for α = 0) can only be compared with analytical calculations [23] in one dimension, if it is defined as the probability of escape through a particular point.

The first passage time is defined (in this simulational study) as the time required by a walker to exit from a specified zone. This time has a distribution and this distribution is studied for various values of α. It is observed that, in all dimensions, the most probable first passage time decreases as α increases. A rigorous analysis and possible scaling behaviour (if any) may be investigated.

Some more interesting studies can be done in this field. In this paper, only the numerical results are reported. A rigorous mathematical formulation of first passage properties for tired walk has to be developed following the same already developed [23] for normal walk

The possibilities of scaling of distribution of return time, distribution of first passage time, distribution of distances and exit probabilities with respect to the tiring factor (α) have also to be explored.

Acknowledgements

Author would like to express sincere gratitudes to D. Dhar, S. S. Manna and P. Sen for important discussions. The library facilities of Calcutta University is gratefully acknowledged.

Cite this paper

Muktish Acharyya, (2015) Model and Statistical Analysis of the Motion of a Tired Random Walker in Continuum. Journal of Modern Physics,06,2021-2034. doi: 10.4236/jmp.2015.614208

References

- 1. Bhattacherjee, S.M., Giacometti, A. and Maritan, A. (2013) Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, 25, Article ID: 503101.

- 2. Hsu, H.-P. and Grassberger, P. (2011) Journal of Statistical Physics, 144, 597.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10955-011-0268-x - 3. Bhattacharjee, J.K. (1996) Physical Review Letters, 77, 1524.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.1524 - 4. Tejedor, V. (2012) Ph.D. Thesis, Universite Pierre and Marie Curie, France and Technische Universitat, Munchen, Germany.

- 5. Lubeck, S. and Hucht, F. (2001) Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 34, L577.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/34/42/103 - 6. Sumedha and Dhar, D. (2006) Journal of Statistical Physics, 115, 55.

- 7. Kapri, R. and Dhar, D. (2009) Physical Review E, 80, Article ID: 1051118.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.80.051118 - 8. Manna, S.S. and Stella, A.L. (2002) Physica A, 316, 135.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4371(02)01497-8 - 9. Goswami, S. and Sen, P. (2012) Physical Review A, 86, Article ID: 022314.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.86.022314 - 10. Dhar, D. and Stauffer, D. (1998) International Journal of Modern Physics C, 9, 349.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S0129183198000273 - 11. De Bacco, C., Majumdar, S.N. and Sollich, P. (2015) Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 48, Article ID: 205004.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/48/20/205004 - 12. Kearney, M.J. and Majumdar, S.N. (2014) Journal of Statistical Physics, 47, Article ID: 465001.

- 13. Condamin, S., Benichou, O., Tejedor, V., Voituriez, R. and Klafter, J. (2007) Nature, 450, 77-80.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature06201 - 14. Tejedor, V., Benichou, O., Metzler, R. and Voituriez, R. (2011) Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 44, Article ID: 255003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/44/25/255003 - 15. Majumdar, S.N., Mounaix, P. and Schehr, G. (2014) Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2014, Article ID: P09013.

- 16. Godreche, C., Majumdar, S.N. and Schehr, G. (2014) Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 47, Article ID: 255001.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/47/25/255001 - 17. Baule, A., Vijay Kumar, K. and Ramaswamy, S. (2008) Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008, Article ID: P11008.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/11/P11008 - 18. Schnitzer, M.J. (1993) Physical Review E, 48, 2553-2568.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.48.2553 - 19. Drewry, H.P.G. and Seaton, N.A. (1995) AIChE Journal, 41, 880-893.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/aic.690410415 - 20. Acharyya, A.B. (2015) Return Probability of a Random Walker in Continuum with Uniformly Distributed Jump-Length. arxiv.org:1506.00269[cond-mat,stat-mech].

- 21. Serino, C.A. and Redner, S. (2010) Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2010, Article ID: P01006.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2010/01/P01006 - 22. Krapivsky, P.L. and Redner, S. (2004) American Journal of Physics, 72, 591.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.1632487 - 23. Redner, S. (2001) A Guide to First-Passage Process. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606014 - 24. Poyla, G. (1921) Mathematische Annalen, 84, 149-160.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01458701