Applied Mathematics

Vol.09 No.01(2018), Article ID:82113,42 pages

10.4236/am.2018.91005

Restrictions on the Material Coefficients in the Constitutive Theories for Non-Classical Viscous Fluent Continua

K. S. Surana1, A. D. Joy1, J. N. Reddy2

1Department of Mechanical Engineering, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA

2Department of Mechanical Engineering, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA

Copyright © 2018 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: December 12, 2017; Accepted: January 27, 2018; Published: January 30, 2018

ABSTRACT

This paper considers conservation and balance laws and the constitutive theories for non-classical viscous fluent continua without memory, in which internal rotation rates due to the velocity gradient tensor are incorporated in the thermodynamic framework. The constitutive theories for the deviatoric part of the symmetric Cauchy stress tensor and the Cauchy moment tensor are derived based on integrity. The constitutive theories for the Cauchy moment tensor are considered when the balance of moments of moments 1) is not a balance law and 2) is a balance law. The constitutive theory for heat vector based on integrity is also considered. Restrictions on the material coefficients in the constitutive theories for the stress tensor, moment tensor, and heat vector are established using the conditions resulting from the entropy inequality, keeping in mind that the constitutive theories derived here based on integrity are in fact nonlinear constitutive theories. It is shown that in the case of the simplest linear constitutive theory for stress tensor used predominantly for compressible viscous fluids, Stokes’ hypothesis or Stokes’ assumption has no thermodynamic basis, hence may be viewed incorrect. Thermodynamically consistent derivations of the restrictions on various material coefficients are presented for non-classical as well as classical theories that are applicable to nonlinear constitutive theories, which are inevitable if the constitutive theories are derived based on integrity.

Keywords:

Non-Classical Continua, Polar Continua, Eulerian Description, Viscous Fluids, Material Coefficients

1. Introduction, Literature Review, and Scope of Work

In fluent continua, velocities are observable quantities and the deformation physics is completely contained in the velocities ( ) and the velocity gradient tensor ( ). Thus, the velocities and the velocity gradient tensor in their entirety must form the basis for the thermodynamic framework that describes the behavior of fluent continua. The velocity gradient tensor can be decomposed into symmetric ( ) and antisymmetric tensors ( ). The symmetric part represents strain rates and the antisymmetric part contains rotation rates. Alternatively, the polar decomposition of yields right or left stretch rate tensors ( or ) and the rotation rate tensor ( ). The tensors , , and contain the same physics in different forms related to strain rates. Likewise, contains rotation rates whereas is a rotation rate matrix. The same physics of rotation rates is contained in both but in different forms. The classical continuum theories for fluent continua are derived using only and ; or are not considered at all in the derivation of the conservation and balance laws and the constitutive theories.

We note that contains rotation rates that are completely defined by the antisymmetric part of the velocity gradient tensor. We refer to these as internal rotation rates (as these arise due to ), and the associated continuum theory as non-classical continuum theory with internal rotation rates or simply non-classical internal polar continuum theory. Recent papers by Surana, et al. [1] - [10] contain details of the derivations of such non-classical continuum theories and associated constitutive theories for solid and fluent continua. Prior to these works, there have been many published works under the title couple stress theories [11] - [19] , particularly in context with solid continua that contain somewhat similar derivations, but use completely different motivation and rationale. Some concepts similar to those used in References [1] - [10] can also be traced in various different forms in the works of Eringen [20] - [28] related to micro-theories of various types.

In the present work, we consider non-classical continuum theories for fluent continua in which both and , that is, in its entirety, are incorporated in deriving the conservation and balance laws and the constitutive theories for thermoviscous compressible fluids without memory. Constitutive theories are derived using the conditions resulting from entropy inequality and the representation theorem (or theory of generators and invariants). Such constitutive theories, when based on integrity, are nonlinear in most instances. The investigation presented in this paper establishes necessary restrictions on the material coefficients in the constitutive theories that ensure that the resulting constitutive theories satisfy the conditions resulting from the entropy inequality. The work presented in this paper is compared and contrasted with the published works.

In the thermodynamic framework for the non-classical continuum theory used here, we have additional physics of rotation rates due to which, when resisted, result in conjugate moments that lead to Cauchy moment tensor (through Cauchy principle). This physics is absent in the classical continuum theory for fluent continua. Thus, it is natural to ask “are the conservation and balance laws of classical continuum theories sufficient when this new physics of rotation rates is present to ensure equilibrium of the deforming matter?’’ Surana, et al. [1] - [10] [29] [30] and Yang, et al. [31] have shown that in the case of non-classical solid and fluent continua, an additional balance law is required, the balance of moments of moments to ensure equilibrium of the deforming matter. The constitutive theories for the moment tensor are affected by the absence or the presence of this balance law. In the work presented here, we examine the constitutive theories in the presence as well as absence of this balance law for establishing restrictions on the material coefficients.

2. Notations and Definitions of Bases

The notations used in this paper conform to Reference [32] but are different than conventional notations in continuum mechanics writings. These new notations are used to provide more clarity and transparency. , , , , refer to material point coordinates (in a fixed Cartesian frame), area, volume, boundary of , and surface bounding , all in the reference or undeformed configuration, whereas , , , , are their counterparts in the current configuration. and are Lagrangian and Eulerian descriptions of a quantity at a material point in the reference configuration with its corresponding location in the current configuration.

A tetrahedron in the undeformed configuration (volume ) with its oblique plane constituting a part of surface bounding deforms and rotates in the current configuration. Equilibrium considerations associated with conservation and balance laws require measurement of stress, strain rates, etc. associated with the deformed tetrahedron. Two obvious choices are covariant and contravariant bases. If the edges of the tetrahedron in the undeformed configuration represent material lines, then upon finite deformation the material lines will become curvilinear. The tangent vectors to these deformed lines at a material point (a point from which the material lines emanate) forming the edges of the deformed tetrahedron are covariant base vectors ( ). The vectors orthogonal to the faces of the deformed tetrahedron (formed by the covariant base vectors) are called contravariant base vectors ( ). and form nonorthogonal covariant and contravariant bases that are reciprocal to each other. Since the covariant base vectors are tangent to the deformed material lines, the convected time derivative of the covariant strain tensor is a physical measure of the strain rate tensor. Likewise the contravariant directions normal to the faces of the tetrahedron is a natural way to define stress tensor. Thus, we define as contravariant Cauchy stress tensor, as the first convected time derivative of the Green’s strain tensor. These measures are physical as these are related to the faces and edges of the true deformed tetrahedron. Since and form reciprocal bases, we could also use covariant directions for stress measure and contravarian directions for strain rate measures, i.e., and , covariant Cauchy stress tensor and contravariant strain rate tensor. Mathematically this is justified, however in terms of physics, this description requires to be normal to the tetrahedron faces and to be the material line tangent vectors. In other words, this description requires a new configuration of the actual deformed tetrahedron that is non-physical. When strain rates are small, the two measures are the same as the deformed and undeformed configurations are virtually the same.

3. Internal Rotation Rates and Their Gradients

Velocities ( ) and velocity gradients ( ) are fundamental measures of deformation physics in fluent continua, hence these in their entirety must form the basis for a complete thermodynamic framework. Polar decomposition of the changing velocity gradient tensor in the deforming fluent continua into stretch rates and pure rotation rates shows that a location and its neighboring locations can experience different rotation rates during deformation. Alternatively, we can also consider decomposition of the velocity gradient tensor into symmetric and antisymmetric tensors. The symmetric tensor is a measure of strain rates whereas the antisymmetric tensor is a measure of pure rotation rates. The measures of internal rotation rates due to deformation in the two approaches describe the same physics but in different forms. Polar decomposition gives rotation rate matrix and not the rotation angle rates whereas the antisymmetric part of the velocity gradient tensor yields rotation angle rates that are explicitly defined in terms of velocity gradients.

If the varying internal rotation rates between the neighboring locations are resisted by the fluent continua, then there must exist conjugate internal moments corresponding to these. The internal rotation rates and the conjugate moments can result in additional energy storage and/or dissipation as well as memory. Since this physics of internal rotation rates arises due to , it exists in all deforming isotropic, homogeneous fluent continua. Incorporating entirety of in the conservation and balance laws implies that we incorporate the additional physics due to internal rotation rates in the existing thermodynamic framework as the physics due to the symmetric part of velocity gradient tensor is already present in it. The internal rotation rates can be visualized as the rotation rates about the axes of a triad located at a material point (or location) whose axes are parallel to the fixed Cartesian x-frame. We present details in the following. The velocity gradient tensor can be decomposed into pure rotation rate tensor and the right and left stretch rate tensors and . is orthogonal and and are symmetric and positive-definite.

(1)

Let ( ); be the eigenpairs of in which , then

(2)

The columns of are eigenvectors and is a diagonal matrix of the eigenvalues ; . If we choose

(3)

then (2) holds, hence definition of in (3) is valid. can now be defined using (1).

(4)

Furthermore, using

(5)

and following a similar procedure we can establish

(6)

(7)

defined by (4) and (7) is unique. We note that in this approach is a rotation rate transformation matrix, hence does not contain rotation angle rates. Alternatively, we can consider decomposition of into symmetric ( ) and antisymmetric ( ) tensors.

(8)

(9)

or

(10)

Expanded form of can be written as

(11)

(12)

Alternatively, (12) can be derived as

(13)

(14)

or

(15)

The rotation rates in (12) are in clockwise sense, whereas quantities in (15) are twice the magnitude compared to (12) and are in counterclockwise sense. We note that , the antisymmetric part of , has rotation rates whereas from the polar decomposition of is a transformation matrix related to rotation rates. The details in both are related to rotation rates and are derived using , hence use of or is interchangeable depending upon the need. Another important point we note is that from (11), is undoubtedly a tensor of rank two. This is also obvious from (13) containing term. However, the rotation rates as in (12) can be viewed as a vector quantity. That is, the three rotations about the axes of a triad at a material point can be arranged in the form of a vector. This form is advantageous when determining gradients of the rotation rates (shown later). We clearly observe that are completely defined by the components of , i.e., dependent on the components of , therefore are not unknown degrees of freedom at a material point or at a location. Definition of from (9) or (10) clearly shows that it is a tensor of rank two, i.e.,

(16)

The gradient of in (16) can be written as

(17)

Clearly , i.e., gradient of , is a tensor of rank three. An alternative presentation of the gradients of is simple and easier to incorporate in the further developments. Let us represent rotation rates as a vector

(18)

Gradients of in (18) can be defined using

(19)

The gradient tensor of rotation rates in (19) can be decomposed into symmetric and antisymmetric tensors and .

(20)

(21)

4. Considerations of Stress, Moment, and Strain Rate Tensors

When the velocity gradient tensor varies between neighboring material points (or locations), so do the internal rotation rates . Hence, the rotation rate tensor can vary between the material points. When the rotation rates are resisted by the deforming fluent continua, conjugate moments are created. and conjugate moments can result in additional energy storage, dissipation, and rheology, in addition to dissipation, rheology, etc., which are already present due to Cauchy stress tensor and the strain rate tensor. Thus, in the deforming fluent continua, rotation rates are conjugate to the moment tensor which necessitates that on the boundary of the deformed volume there must exist resultant moment.

Consider a volume of matter in the reference configuration with closed boundary . The volume is isolated from by a hypothetical surface as in the cut principle of Cauchy. Consider a tetrahedron such that its oblique plane is part of and its other three planes are orthogonal to each other and parallel to the planes of the x-frame. Upon deformation, and occupy and and likewise and deform into and . The tetrahedron deforms into whose edges (under finite deformation) are non-orthogonal covariant base vectors . The planes of the tetrahedron formed by the covariant base vectors are flat but obviously non-orthogonal to each other. We assume the tetrahedron to be the small neighborhood of material point so that the assumption of the oblique plane being flat but still part of is valid. When the deformed tetrahedron is isolated from volume it must be in equilibrium under the action of disturbance on surface from the volume surrounding and the internal fields that act on the flat faces which equilibrate with the mating faces in volume when the tetrahedron is placed back in the volume .

Consider the deformed tetrahedron . Let be the average stress per unit area on plane , be the average moment per unit area on plane (henceforth referred to as moment for short), and be the unit exterior normal to the face . , , and all have different directions when the deformation is finite [32] .

As mentioned earlier, the edges of the deformed tetrahedron are covariant base vectors that are tangent to deformed curvilinear material lines:

(22)

and

(23)

The columns of are covariant base vectors that form non-orthogonal covariant basis. Contravariant base vectors are normal to the faces of the deformed tetrahedron formed by the covariant base vectors:

(24)

and

(25)

The rows of are contravariant base vectors . These form a non-orthogonal contravariant basis. Covariant and contravariant bases are reciprocal to each other [32] .

4.1. Contravariant Cauchy Stress Tensor

The definition of the stresses on the non-oblique faces of the deformed tetrahedron formed by the covariant base vectors in the contravariant directions orthogonal to the faces of the deformed tetrahedron is most natural. Let or be the contravariant stress tensor with components or with dyads . Component or is in the direction on a face of the tetrahedron with unit exterior normal , i.e., on the face. Likewise or and or act on and faces in the and directions. Using dyads or contravariant law of transformation, we can write [32]

(26)

Using (22) in (26), we can write

(27)

is a contravariant Cauchy stress tensor (Lagrangian description) from which can be easily obtained by replacing by and by in (27). Since the dyads of or are , the Cauchy principle holds between and .

(28)

4.2. Covariant Cauchy Stress Tensor

Instead of using contravariant directions and stress components and covariant basis , we could use covariant stress components or and contravariant basis . Consideration of of course will require a different deformed tetrahedron such that covariant base vectors are normal to its oblique faces. The adverse consequences of choosing this measure of stress for finite deformation are discussed by Surana, et al. [32] [33] . Here we proceed with this measure as an alternative to the contravariant stress measure. Using dyads and components , we can write [32]

(29)

And using (24)

(30)

is the covariant Cauchy stress tensor (Eulerian description) from which can be obtained by replacing with and with in (30). Since the dyads of are , the Cauchy principle holds between and .

(31)

Remarks.

The Cauchy stress tensors or and or are non-symmetric at this stage and so are the stress tensors and . Following the details given in Reference [32] we can also define Jaumann stress tensor using and stress measures.

4.3. Contravariant and Covariant Cauchy Moment Tensor

When the deformed tetrahedron with moment on its oblique face is isolated from the volume , its faces will have existence of moments (per unit area) on them. As in case of stress measure, contravariant basis is the most natural way to define these. Following the notations parallel to those used in case of Cauchy stress tensors, we can write the following using contravariant measures of moment tensor:

(32)

Using (22) in (32) we obtain

(33)

and the Cauchy principle

(34)

Likewise when using covariant measure of moment tensor we have

(35)

And using (24) in (35) we obtain

(36)

and the Cauchy principle

(37)

As in case of stress tensors and , the moment tensors and are also non-symmetric at this stage.

4.4. Convected Time Derivatives of the Stress and Strain Tensors

Convected time derivatives of strain and stress tensors in covariant and contravariant bases play an important role in the Eulerian description, especially in

constitutive theories. If we define and covariant and contrava-

riant Cauchy stress tensors and and as corresponding second

Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensors, then the convected time derivatives of

and in co- and contravariant bases are defined by and ;

and are given by the following for compressible matter [32] .

(38)

and

(39)

and Jaumann rates are defined as

(40)

If and are Green’s and Almansi strain tensors in co- and contravariant bases, then their convected time derivatives and ; are defined as [32]

(41)

and

(42)

and Jaumann rates ; are defined as

(43)

In classical continuum theories for thermoviscous fluids without memory [32] , only stress rates of order zero, i.e., , , and , are used in the ordered rate constitutive theories of up to order n [32] . In such theories, , , and ; are considered as argument tensors (in addition to some others) of , , and , respectively. Thus, the Cauchy stress tensor and the constitutive theory for it are basis dependent. In the derivations of the conservation and balance laws and the constitutive theories, we choose basis independent as Cauchy stress tensor which could be , , or ; . ; convected time derivatives are considered as arguments of which could be , , or . These choices of and ; make all derivations hold for any desired choice of stress measure and the corresponding convected time derivatives of the strain measures. In case of non-classical theories considered here, exactly the same notation is used except that the Cauchy stress tensor is not symmetric, thus ; cannot be the argument tensors of , but can be paired with it. Similarly, the Cauchy moment tensor choice can be , , or , depending upon the choice of basis. In the derivations and the details that follow, we consider and as Cauchy stress and moment tensors. With these choices the details that follow hold for any desired choice of basis.

5. Conservation and Balance Laws

The non-classical continuum theory used in this paper for fluent continua incorporates new physics due to internal rotation rates that are defined by , hence known. This new physics is absent in the currently used thermodynamic framework for fluent continua. Introduction of this new physics may influence some or all conservation and balance laws which can only be determined by initiating their derivations from the most fundamental stage as we do in classical continuum theories [32] [34] . In this process of deriving conservation and balance laws with the new rotation rate physics we may very well find that some conservation and balance laws are not affected; however, such conclusions without rigorous derivations are not possible. In the non-classical continuum theory for fluent continua with velocities, velocity gradients, strain rate tensor, internal rotation rates, and their gradients describing the kinematics of deformation, we must at least consider the following conservation and balance laws based on the assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium that are used for classical continuum theories during the evolution of the deforming matter: 1) conservation of mass, 2) balance of linear momenta, 3) balance of angular momenta, 4) first law of thermodynamics (i.e., balance of energy), and 5) second law of thermodynamics (i.e., entropy inequality).

The use of conservation and balance laws that are necessary for classical continuum theories for non-classical continuum theories with additional physics due to internal rotation rates raises a fundamental concern: are these sufficient to ensure equilibrium of deforming non-classical fluent continua? It is pointed out by Yang, et al. [31] that an additional balance law is required in non-classical continuum theories for solids incorporating internal rotations (also see [29] [30] ) arising from the Jacobian of deformation. In case of fluent continua, the existence of internal rotation rates due to the velocity gradient tensor necessitates an additional balance law to ensure that in the presence of this physics the entire volume of fluid will remain in equilibrium. In recent papers by Surana, et al. [29] [30] , comprehensive discussion of the work of Yang, et al. [31] as well as authors’ own view regarding the need for this additional balance law in non-classical continuum theories for solid and fluid continua have been presented. This is not repeated here for the sake of brevity. The readers can refer to References [29] [30] [31] .

Balance of moments of moments (similar to balance of moments of forces in classical continuum theory) is an additional balance law needed due to the presence of Cauchy moment tensor that is independent of forces. In the derivation presented subsequently, one notes that this balance law yields the Cauchy moment tensor to be symmetric, just like the balance of angular momenta in classical continuum theory gives rise to the symmetry of the Cauchy stress tensor. One can use inductive reasoning to extend this concept of the need for additional balance laws when additional kinematic variables (over and beyond velocities and rotation rates) and their conjugates appear in the theory. One notes that each additional kinematic variable introduces its conjugate that requires two balance laws, out of which the balance law that requires their sum to balance with others already exists from the consideration of prior kinematic variables; hence the new conjugate quantities can be incorporated in it, but the other balance law that requires balance of their moments is an additional balance law. In other words, only one balance law is needed for each conjugate quantity corresponding to each kinematic variable.

In the non-classical continuum theory considered here for fluent continua, we need only one additional balance law, namely the balance of moments of moments, due to the fact that balance of moments balance law already exists from the classical continuum theory. Whether we consider balance of moments of moments as an additional balance law in non-classical continuum theories for fluent continua influences the derivation of the constitutive theories for the Cauchy moment tensor. In the present work we consider both cases and the associated constitutive theories to establish restrictions on the material coefficients appearing in them.

5.1. Conservation of Mass, Balance of Linear and Angular Momenta

We consider compressible fluent non-classical continua with internal rotation rates to present conservation and balance laws. For incompressible fluent continua, and , hence the conservation and balance laws presented here can be easily modified.

Conservation of mass in a deforming volume of fluid leads to continuity equation that remains the same in the present work as it is for the classical continuum theory [32] [34] and is given in the following for compressible fluent continua in Eulerian description.

(44)

or

(45)

in which is the density at a material point at in the current configuration.

For a deforming volume of matter, the rate of change of linear momenta must be equal to the sum of all other forces acting on it. This is Newton’s second law applied to a volume of matter. The derivation is exactly same as that for classical continuum theory. Following Reference [32] and using Cauchy stress tensor , we can write the following.

(46)

or

(47)

in which are body forces per unit mass and is basis independent Cauchy stress tensor. Equations (46) or (47) are momentum equations in , , and directions.

The principle of balance of angular momenta for a non-classical continuum can be stated as: The material derivative (time rate of change) of moments of momenta must be equal to the vector sum of the moments of forces and the moments. Thus, due to the surface stress , total surface moment (per unit area), body force (per unit mass), and the momentum for an elemental mass in the current configuration we can write the following in Eulerian description.

(48)

The negative sign for is due to the fact that clockwise rotation rates are considered positive. The moments created by these must also be considered positive when clockwise. Following the derivation given by Surana, et al. [1] - [6] , we obtain

(49)

Since volume is arbitrary, we have

(50)

or

(51)

Equation (51) represents balance of angular momenta. The basis independent Cauchy stress tensor is non-symmetric and so is the basis independent Cauchy moment tensor .

5.2. First Law of Thermodynamics

The sum of work and heat added to a deforming volume of matter must result in increase of the energy of the system. This is expressed as a rate equation in Eulerian description in the following.

(52)

, , and are total energy, heat added, and work done. These can be written as [1] - [6] [32]

(53)

(54)

(55)

where is specific internal energy, is body force vector per unit mass, and is rate of heat. Note that the additional term in contributes additional rate of work due to rates of internal rotations . Expanding integrals and following Reference [32] , one can show the following.

(56)

Since volume is arbitrary, the following holds:

(57)

We note that in the term we can substitute from the balance of angular momenta (51), thereby eliminating gradients of but instead introducing Cauchy stress tensor .

5.3. Second Law of Thermodynamics

Let be entropy density in deformed volume , be the entropy flux between and the volume of matter surrounding it (i.e., contacting sources), and be the source of entropy in due to non-contacting bodies, then the rate of increase of entropy in volume is at least equal to that supplied to from all contacting and non-contacting sources [32] . Thus

(58)

Using Cauchy’s postulate for , we have

(59)

(60)

Since the volume is arbitrary, the following holds:

(61)

Using

(62)

where is the absolute temperature, is the heat vector, and is a suitable potential. Substituting for ( ) from energy equation (after inserting term in it) and expressing Helmholtz free energy density in terms of , , and ( ), we can derive the following for (61) [1] - [6] [32] :

(63)

in which is the gradient of internal rotation rates. Inequality (63) resulting from the second law of thermodynamics is the most fundamental form of entropy inequality in Helmholtz free energy density .

5.4. Balance of Moments of Moments as a Balance Law

In a deforming volume of matter, conservation and balance laws ensure thermodynamic equilibrium. Thus, in classical continuum theories, conservation of mass, balance of linear and angular momenta, and the first and second laws of thermodynamics must be satisfied. In non-classical continuum theories for solids and fluids incorporating the internal rotations (due to Jacobian of deformation) and the internal rotation rates (due to velocity gradient tensor), are the conservation and balance laws for classical continuum theories sufficient to ensure equilibrium of the deforming matter?

Yang, et al. [31] pointed out, using geometric considerations, that in non-classical continuum theories, an additional balance law, balance of moments of moments, is required to ensure equilibrium of the deforming solid matter. Surana, et al. [1] - [10] have used this concept successfully. More recently Surana, et al. [29] [30] showed theoretically as well as through model problems that in the case of non-classical continuum theories the balance of moments of moments is a necessary balance law. In the absence of this balance law the constitutive theories for non-classical solid and fluent continua become non-physical and spurious.

Balance of moments of moments (similar to balance of moments of forces in classical continuum theory) is additional balance law needed due to the presence of Cauchy moment tensor that is independent of forces. In the derivation presented subsequently, one notes that this balance law yields the Cauchy moment tensor to be symmetric, just like the balance of angular momenta in classical continuum theory gives rise to the symmetry of the Cauchy stress tensor. One can use inductive reasoning to extend this concept of the need for additional balance laws when additional kinematic variables (over and beyond velocities and rotation rates) and their conjugates appear in the theory. One notes that each additional kinematic variable introduces its conjugate that requires two balance laws, out of which the balance law that requires their sum to balance with others already exists from the consideration of prior kinematic variables; hence the new conjugate quantities can be incorporated in it, but the other balance law that requires balance of their moments is an additional balance law. In other words, only one balance law is needed for each conjugate quantity corresponding to each kinematic variable [6] .

In the non-classical continuum theory considered here for fluent continua, we need only one additional balance law, namely the balance of moments of moments, due to the fact that balance of moments balance law already exists from the classical continuum theory. Consider the current configuration at time t. Consider Eulerian description. For the deforming volume of fluid to be in equilibrium, moments of moments (or couples) must vanish. In the moments of moments balance law, we must consider and also the shear components of the stress tensor , that is, . Thus, we can write the following (neglecting inertial terms) in Eulerian description.

(64)

We expand the second term in (64) and then convert the integral over to the integral over using the divergence theorem and use balance of angular momenta for further simplification to obtain the following:

(65)

and since is arbitrary, we obtain the following form:

(66)

Equation (66) implies that the Cauchy moment tensor is symmetric. Thus in the non-classical continuum theory presented here for fluent continua, the Cauchy moment tensor is symmetric if the new balance law is used but the Cauchy stress tensor is always non-symmetric. In the classical continuum theory, the Cauchy stress tensor is symmetric and the Cauchy moment tensor does not exist as the rotation rates are not considered in the theory. We remark here also as we did in our earlier papers [9] [10] [29] [30] that in most reported works on non-classical theories (specifically for solids) except Reference [31] this balance law is not considered. As a consequence the Cauchy moment tensor remains non-symmetric, requiring additional constitutive theories for the non-symmetric part of the moment tensor. However, the constitutive theory for the symmetric part of Cauchy moment tensor remains the same regardless of whether one uses balance of moments of moments as a balance law. In this paper we consider both cases, i.e., symmetric as well as non-symmetric (in the absence of balance of moments of moments). The resulting constitutive theories are compared and the material coefficients and the restrictions on them are established.

6. Constitutive Theories

In this section we present constitutive theories for compressible non-classical fluent continua with dissipation when the balance of moments of moments is not considered as a balance law. Thus, is non-symmetric, requiring constitutive theories for as well as . When the balance of moments of moments is used as an additional balance law, , hence, there is no constitutive theory for . The constitutive theories for incompressible fluids can be easily obtained using the constitutive theories presented here for compressible case by imposing restriction that and . These details are intentionally omitted for the sake of brevity.

From entropy inequality as well as other balance laws it is straightforward to conclude that , , , , , and are the constitutive variables. A decision on their argument tensors is facilitated if we can establish rate of work conjugate pairs from the entropy inequality. From the entropy inequality (63) we note that and are conjugate, but both of the trace terms contain non-symmetric tensors, hence these are not conjugate pairs [35] - [54] .

Consider decomposition of , , , and into symmetric and antisymmetric tensors

(67)

Note that

(68)

and

(69)

(70)

Using (67) - (70), the entropy inequality (63) reduces to

(71)

In and both tensors are symmetric and in both tensors are antisymmetric, hence these are rate of work conjugate pairs. Likewise, in , and are conjugate as well.

We consider , , , , , and as possible dependent variables in the constitutive theories. For compressible fluent continua, density must be incorporated as an argument of all dependent variables in the constitutive theories. We note that compressibility is due to determinant of the Jacobian

of deformation . Recall that in Lagrangian description (from

continuity) , hence in which is density in the reference configuration (constant), i.e., instead of we can use in Lagrangian description or in Eulerian description as an argument of all dependent variables in the constitutive theories. At later stages can be replaced by simply using simple calculus. Temperature is certainly a valid choice for thermoviscous behavior. From the conjugate pairs in (71), we note that , , , and are natural choices of argument tensors for , , , and dependent variables in the constitutive theories, respectively.

Additionally , , , , and all must be considered as argument tensors of and . Thus, at this stage we have the following for the dependent variables in the constitutive theories and their argument tensors.

(72)

Using in (72) one can obtain the material derivative of needed in (71).

(73)

From the continuity Equation (44)

(74)

and

(75)

Using (74) and (75) in (73)

(76)

Substituting (76) into (71) and regrouping terms

(77)

For inequality (77) to hold for arbitrary but admissible , , , , and the following must hold.

(78)

(79)

(80)

(81)

(82)

and

(83)

Equations (78)-(83) are fundamental relations resulting from the entropy inequality.

Remarks.

a) Equations (78)-(81) imply that is not a function of , , , and .

b) Based on (82), is not a dependent variable in the constitutive theory as , hence is deterministic from .

c) The inequality (83) in this form is essential. For example, if we set

(84)

and

(85)

then from (84) we note that is not a function of as is not a function of , which is a contradiction as and are conjugate.

In view of these remarks, the arguments of the dependent variables in the constitutive theories in (72) can be modified. We can use instead of

.

(86)

We note that even though in (86) we do have argument tensors of the dependent variables in the constitutive theory, resolution of the first term in the entropy inequality (83) is essential before we can proceed further.

Decomposition of Symmetric Cauchy Stress Tensor

We consider decomposition of into equilibrium and deviatoric stress

tensors, and . The motivation for doing this is to separate the

stress tensor into one that is purely responsible for change in volume and another one that only causes change in shape, i.e., distortion.

(87)

in which we consider the following

(88)

That is, is not a function of and vanishes when is zero. Substituting (87) into entropy inequality (83) and rearranging terms

(89)

6.1. Constitutive Theory for Equilibrium Stress : Compressible Thermofluids

Since is not a function of and neither is (due to (88)), the constitutive theory for must be derivable from

(90)

in which

(91)

is called thermodynamic pressure and is generally referred to as equation of state [32] [34] in which is expressed as a function of and or

and , where is specific volume. If we assume compressive pres-

sure to be positive, then in (90) can be replaced by . Using (90), inequality (89) reduces to

(92)

6.2. Constitutive Theory for Equilibrium Stress : Incompressible Thermofluids

For incompressible matter density is constant, hence . For this case

, hence the constitutive theory for this case cannot be derived using

(90), instead we must consider . We must incorporate the incompressibility condition in the entropy inequality. We recall that the incompressibility condition in Eulerian description is given by

(93)

Based on (93), we can write

(94)

in which is an arbitrary Lagrange multiplier. Adding (94) to (89) and realizing that for incompressible matter , we obtain

(95)

In case of incompressible fluids is a function of only, hence we have

(96)

is called mechanical pressure. Since is an arbitrary Lagrange multiplier, it is not deterministic from the deformation field. In view of (96), inequality (95) also reduces to (92), that is, (92) holds for both compressible and incompressible matter.

The final form of the entropy inequality is given by

(97)

This form of the entropy inequality has all the conjugate pairs needed for constitutive theories.

6.3. Final Choice of the Dependent Variables and Their Argument Tensors in the Constitutive Theories

In view of the stress decomposition, constitutive theories for , and the conjugate pairs in (92), we finally can write the following.

Compressible Matter

(98)

If compressive pressure is considered positive, then can be replaced by in (98).

Incompressible Matter

In this case , constant, hence we have

(99)

The choice of argument tensors for can be modified and made more general by recognizing that

(100)

and being the first convected time derivatives of Green’s and Almansi strain tensors in covariant and contravariant bases. Let

(101)

be the convected time derivatives of Green’s and Almansi strain tensors and Jaumann rates up to order n. We note that contravariant stress measure is conjugate with the covariant convected time derivatives and likewise covariant stress measure is conjugate with contravariant convected time derivatives. Thus with as deviatoric stress measure its argument (same as ) can be replaced by in (98) and (99). Using the basis independent notation, we consider

(102)

in (98) for compressible case (all others remaining same) and

(103)

in (99) for incompressible case (all others remaining same).

6.4. Conditions to be Satisfied by the Constitutive Theories

The final form of the entropy inequality (97) must be satisfied by the constitutive theories for , , , and . The entropy inequality (97) is satisfied if

(104)

The inequalities in (104) imply that the rate of work due to , , and (i.e., , , and ) must be positive. Thus, the constitutive theories for , , , and must ensure that the inequalities in (104) are satisfied. In other words, the inequalities in (104) form the basis for determining restrictions on the material coefficients. We note that any other means of determining restrictions on the material coefficients in the constitutive theories do not have thermodynamic basis. In this paper we use inequalities (104) to determine restrictions on the material coefficients in the constitutive theories for non-classical thermoviscous compressible and incompressible fluids as well as classical fluids.

6.5. Theory of Generators and Invariants (Representation Theorem)

In the following sections we present derivations of the constitutive theories for , , , and using theory of generators and invariants (representation theorem) based on pioneering works of Spencer, Wang, Zheng, etc. [35] - [54] . To illustrate the basic concepts of representation theorem, consider a symmetric tensor of rank r with as its arguments that could be a mix of tensors of rank r or lower. If tensor belongs to a space, then the space must have a basis, referred to as integrity. It has been shown that for a symmetric tensor of rank r the basis consists of all possible tensors of rank r that are derived using its arguments , called the combined generators of the argument tensors. If , are the combined generators constituting the basis of the of space of tensor , then we can represent by a linear combination of , , i.e.

(105)

(106)

in which are the combined invariants of the argument tensors of .

Remarks.

1) When is an antisymmetric tensor of rank r then the same representation theorem concept applies except that in this case the combined generators will all be antisymmetric tensors of rank r.

2) It has not been shown in references [35] - [54] or elsewhere, to our knowledge, that if is a non-symmetric tensor of some rank with non-symmetric tensors as its arguments, then the representation theorem holds.

3) Material coefficients are derived from using Taylor series expansion in the invariants and others (like temperature ) about a known configuration.

4) We use the representation theorem to derive constitutive theories for , , , and and consider their simplified forms to illustrate the restrictions on the material coefficients.

6.6. Constitutive Theory for : Compressible Matter

Consider

(107)

is a symmetric tensor of rank two whose arguments are , a tensor of rank zero, , all symmetric tensors of rank two, and , a tensor of rank zero. Based on the theory of generators and invariants, can be expressed as a linear combination of the combined generators of its argument tensors that are symmetric tensors of rank two.

Let I, be the combined generators of the argument tensors of that are symmetric tensors of rank two and be the combined invariants of the same argument tensors of , then we can write

(108)

in which

(109)

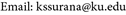

We note that (108) and (109) hold in the current configuration in which the deformation is not yet known, hence are not material coefficients. To determine or establish material coefficients from (109), we consider Taylor series expansion of each in and about a known configuration of the deforming volume of matter and retain only up to linear terms in the invariants and (for simplicity). Following reference [32] , we can derive

(110)

, , , , and are material coefficients defined in known configuration . This constitutive theory requires material coefficients. The material coefficients are functions of , , and . This constitutive theory is nonlinear in the components of the augument tensors of and is based on integrity, the only assumption being in the Taylor series expansion of .

Rate Constitutive Theory of Order One for : Compressible Matter

In this case we limit the number of argument tensors of to , (or ), and by choosing . That is, we consider

(111)

Based on (111) we have

(112)

and

(113)

In (113) we could have also considered principal invariants of . Since the two sets of invariants are related, the resulting constitutive theory is unaffected. Thus

(114)

Using (112) and (113) for and in the general expression (110) we can obtain the following explicit expression for the first order ( ) consti-

tutive theory for .

(115)

This constitutive theory requires 14 material coefficients and contains up to fifth degree terms in the components of .

6.7. Constitutive Theory for : Compressible Matter

Using (98) defining the argument tensors of , we have

(116)

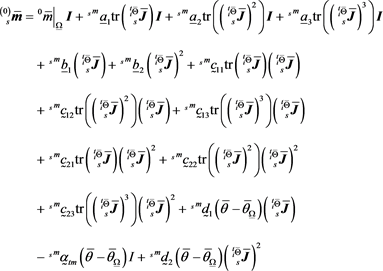

and are both symmetric tensors of rank two and and are tensors of rank of zero. Based on the theory of generators and invariants (i.e., representation theorem), can be expressed as a linear combination of the combined generators of its argument tensors that are symmetric tensors of rank two. , , and are the combined generators of , , and that are symmetric tensors of rank two. Thus, based on representation theorem, we can write

(117)

in which

(118)

are the combined invariants of the argument tensors of in (116). We can either choose

(119)

or the principal invariants of , i.e., , , and . In the

following derivation we consider (119). To derive material coefficients using (118), we expand each ; in Taylor series in ; and about a known configuration and retain only up to linear terms in the invariants and (for simplicity). Following Reference [32] we can derive

(120)

(120)

This constitutive theory requires determination of 14 material coefficients, all evaluated in a known configuration . This constitutive theory is based on integrity. The only assumption is in Taylor series expansion of ; . Material coefficients , , , and are functions of , , and . This constitutive theory requires ( ) material coefficients. The constitutive theory is also nonlinear in the argument tensors and is based on integrity, the only assumption being Taylor series expansion of ; .

6.8. Constitutive Theory for : Compressible Matter

Consider (using (98))

(121)

We note that and are both antisymmetric tensors of rank two and and are tensors of rank zero. We have the following invariants for .

(122)

Thus, the only non-zero invariants in this case are and . These are obviously related.

(123)

Let be the non-zero combined invariant of the argument ten-

sors of in (121). The combined generators of the argument tensors of that are antisymmetric tensors of rank two only include . Hence, we can write

(124)

(125)

To determine material coefficients in the constitutive theory for in (124), we expand in (125) in Taylor series in and about a known configuration and retain only up to linear terms in and . Following Reference [32] , we can derive

(126)

This constitutive theory requires three material coefficients, , , and . However, if the term is neglected then the constitutive theory (126) only requires two material coefficients, and . This constitutive theory contains up to cubic terms in the components of the antisymmetric tensor , hence is a nonlinear constitutive theory in the components of .

6.9. Constitutive Theory for Heat Vector

Recall the inequality (104) resulting from the second law of thermodynamics.

(127)

In (127), and are conjugate. The simplest possible constitutive theory for can be derived by assuming that is proportional to which leads to the following constitutive theory for :

(128)

Alternatively, if we assume

(129)

then using representation theorem, we can begin with (as is the only combined generator of , , and that is a tensor of rank 1)

(130)

in which

(131)

being the only invariant of the argument tensors , , and . Expanding in Taylor series in and about a known configuration and retain only up to linear terms in and , we obtain the following [32] :

(132)

in which

(133)

This nonlinear constitutive theory is a complete constitutive theory based on the representation theorem (using (130) and (131)). The only assumption in the constitutive theory is the truncation of the Taylor series beyond linear terms in and . Obviously standard Fourier heat conduction law (128) is a subset of (133) when k is the only material coefficient that only depends on temperature .

7. Restrictions on the Material Coefficients in the Constitutive Theories for , , , and

In this section we consider the constitutive theories for , , , and derived using

(134)

with these argument tensors, the constitutive theories are basis independent as

and and are basis independent as well. When

is replaced with ; , the constitutive theories for the deviatoric part of the symmetric Cauchy stress tensor become basis dependent. Thus, in what follows, we could replace , , and in (134) with , , and , but instead we continue with the notation in (134) as this is more general and holds when the constitutive theories are basis dependent. For simplicity we neglect term and terms without loss of generality.

7.1. Constitutive Theory for

7.1.1. Compressible Matter

We consider the constitutive theory for given by (115) derived from the conditions (Equation (104)) resulting from entropy inequality. The constitutive theory for must satisfy

(135)

Substituting for from (115) in (135) (after neglecting first term and term) the following must hold (redefining and to conform to standard notation used in fluid mechanics).

(136)

In inequality (136) some trace terms with the material coefficients are always positive whereas the others may be positive or negative. We note that for arbitrary but admissible choice of , the following holds.

(137)

Using (137), we can determine the signs of the terms containing products of the trace terms in (136). To ensure that always holds regardless of those terms that can be negative, the material coefficients corresponding to these terms must be set to zero so that always holds for all arbitrary but admissible choices of . This gives

(138)

with the following restrictions on the material coefficients

(139)

with these restrictions on the material coefficients the constitutive theory for

becomes

(140)

This constitutive theory (140) for satisfies the condition for arbitrary but admissible as required by the entropy inequality.

7.1.2. Incompressible Matter

For incompressible fluids and , hence and reduce to

(141)

(142)

The restrictions on the material coefficients are the same as in (139). The constitutive theory (142) ensures that in (104) is positive, hence satisfies entropy inequality.

7.2. Constitutive Theory for : Compressible and Incompressible Matter

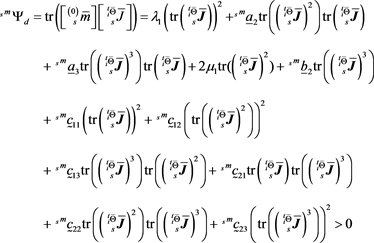

We consider the constitutive theory for given by (120) derived using integrity. From the conditions (equation (104)) resulting from the entropy inequality, the constitutive theory for must satisfy

(143)

Substituting for from (120) in (143) (after neglecting the first term and without loss of generality) the following must hold (redefining and to conform with the notations used for the constitutive theory for ).

(144)

(144)

In inequality (144) some trace terms with the material coefficients are always positive, whereas the others may be positive or negative, hence the products of such terms are not ensured to be positive. We note that

(145)

Using (145) we can determine the signs of terms continuing products of the trace terms in (144). To ensure that always holds regardless of those terms that can be negative, the material coefficients corresponding to those terms that can be negative must be set to zero so that always holds for all arbitrary but admissible choices of . This gives

(146)

with the following restrictions on the material coefficients.

(147)

with these restrictions on the material coefficients, the constitutive theory for becomes

(148)

This constitutive theory for satisfies the condition for arbitrary but admissible as required by entropy inequality.

7.3. Constitutive Theory for : Compressible and Incompressible Matter

Consider the constitutive theory for given by (126) derived using integrity. From the conditions (Equation (104)) resulting from the entropy inequality, the constitutive theory for must satisfy

(149)

Substituting for from (126) into (149) (after neglecting the first term and without loss of generality) the following must hold (redefining and ).

(150)

We note that is negative, hence

(151)

are the restrictions on the material coefficients that ensure that holds for arbitrary but admissible choices of tensor.

7.4. Constitutive Theory for

Consider the constitutive theory for derived based on integrity [32] using given by (132). The conditions (Equation (104)) resulting from the entropy inequality require that

(152)

Substituting from (132) in (152), the following must hold (dropping for and ).

(153)

Since , the inequality (152) is satisfied for arbitrary but admissible choices of if

(154)

The conditions on and are the restrictions on these material coefficients due to the condition (152) resulting from the entropy inequality.

8. Remarks Regarding Constitutive Theories and Restrictions on the Material Coefficients

1) The entropy inequality provides two important pieces of information: the first one, the conjugate pairs, is crucial in determining the constitutive theories and the second, dissipation functions and , provides mechanism for establishing restrictions on the material coefficients in the constitutive theories.

2) The conjugate pairs in the entropy inequality are essential in establishing the constitutive variables and their argument tensors.

3) Once the argument tensors of the constitutive variables are known, the representation theorem provides a consistent and rigorous mathematical frame for deriving the constitutive theories as well as establishing the material coefficients. The constitutive theories so derived are based on integrity, hence utilize complete basis of the space in which the constitutive variables exist. In deriving these constitutive theories we have only utilized one important piece of information from the entropy inequality, the conjugate pairs.

4) The other important aspect present in the conjugate pairs is that the trace of their products represents the rate of work (dissipation function), hence must be positive. Thus, the constitutive theories derived in (3) must be substituted in the dissipation function and examined to ensure that the dissipation function is always positive. This provides means to establish restrictions on the material coefficients in the constitutive theories. It may very well be that some material coefficients need to be forced to be zero (as shown in Section 7) in order for the dissipation function to be unconditionally positive.

5) We have shown in Sections 7.1 - 7.4 that the constitutive theories based on representation theorem and integrity do not always satisfy the conditions of the corresponding dissipation function to be unconditionally positive.

6) We emphasize that within the restriction of the thermodynamic frame, and specifically the entropy inequality and the conditions resulting from it, the dissipation function (and some other similar terms) is the only means of establishing restrictions on the material coefficients. One may alternatively seek other means that may lead to different conclusions [55] regarding the restrictions on the material coefficients, hence may result in altogether different restrictions on the material coefficients than reported in this paper. However, if we only follow the conditions resulting from the entropy inequality, then obviously these alternate approaches and the restrictions on the material coefficients derived using them are thermodynamically not admissible.

7) We note that all constitutive theories presented here are based on integrity (complete basis) and are nonlinear, that is, the constitutive variables are nonlinear functions of their argument tensors. In such theories solving for the argument tensor in terms of the constitutive variable is non-unique and may not even be possible. However, if the constitutive theory is linear, then one could possibly obtain an expression for the argument tensor in terms of the constitutive variable and the material coefficients. Can this expression for the argument tensor be used to establish restrictions on the material coefficients? Maybe so, but it has no thermodynamic basis, that is, it is not justified based on the conditions resulting from the entropy inequality.

8) In the section that follows we consider specialized form of the constitutive theories presented in this paper that are valid for classical continuum theories in which the Cauchy stress tensor is symmetric and is a linear function of the first convected time derivative of the strain tensor. We examine restrictions on the material coefficients using the concepts presented here and compare these with the published works.

9. Classical Continuum Theory for Viscous Fluids: Restrictions on Material Coefficients

In classical continuum theory for compressible viscous fluids without memory the Cauchy stress tensor is symmetric and if we only consider linear constitutive theory for the deviatoric Cauchy stress tensor, then the Cauchy stress tensor basis is independent as the first convected time derivatives of the Green’s and Almansi strain tensors are the same, namely, the symmetric part of the velocity gradient tensor, and we can write the following for the constitutive theory for the deviatoric Cauchy stress tensor.

(155)

From the derivation of the constitutive theory for for the non-classical case presented in this paper, we clearly note the and are two independent material coefficients as the derivation of the constitutive theory provides no mechanism of dependence of one on the other. Stokes [55] suggested that if the density of the fluid remains nearly constant, that is, if the fluid is almost incompressible, one could make the assumption that . This has been referred to as Stokes’ assumption or Stokes’ hypothesis and is used almost universally in fluid mechanics. More recently, Rajagopal [56] advocated that must hold and that is invalid. The derivation by Rajagopal [56] in simple terms is explained in the following.

Using (155), we postulate that inverse of (155) should be unique, that is, we derive in terms of , which gives us

(156)

From (156), we note that when , is infinity, hence Rajagopal [56] argued that must hold (under the presumption that ). This conclusion has also been arrived at by Eringen [22] using but, unfortunately, using incorrect tensor algebra; hence, this derivation in support of is not valid either. In the approach used by Rajagopal [56] there are several issues that are in violation of thermodynamic consistency, as explained next.

1) First, we have seen that the constitutive theory for is nonlinear in when it is based on integrity; hence, if we attempt to express as a function of , it will be non-unique.

2) Secondly, the derivation of (156) has nothing to do with the condition resulting from the entropy inequality which requires that

(157)

Thus, using (156) to establish the restriction that must hold has no thermodynamic basis. This restriction is as unfounded as proposed by Stokes [55] .

3) We have already seen that and are two independent material coefficients based on the derivation of the constitutive theory for or . There has to be a much more compelling argument based on physics to make them dependent on each other than the relation (156).

4) Based on entropy inequality, validity of (156) implies that it satisfies (157). Substituting (156) in (157), we obtain

(158)

In (158), when and , we cannot ensure that in (158) is

positive for all admissible as the magnitudes of and

cannot be quantified, and due to the negative sign associated with the second term in (158). Thus (156) may be in violation of the condition (157) resulting from the entropy inequality.

If we just consider constitutive theory (155) and use inequality (157), then we have

(159)

For to be greater than zero, and must hold. Furthermore, since and are two independent non-zero material coefficients, they cannot be expressed in terms of each other. No other restrictions on and can be inferred from (159). Restrictions on and for the constitutive theory for the heat vector remain the same as discussed earlier, that is, and must hold.

Remarks.

1) We have shown that and are the only restrictions on the material coefficients and that are thermodynamically justified based on entropy inequality.

2) (Stokes’ hypothesis) or advocated by Rajagopal [56] have no thermodynamic basis, hence cannot be justified.

3) and are two independent material coefficients that must be determined from experiments for a fluid of interest.

10. Summary and Conclusions

1) A consistent derivation of the constitutive theories for , , , and for non-classical viscous fluent continua has been presented using the conjugate pairs in the entropy inequality in conjunction with the representation theorem (theory of generators and invariants). In this derivation, balance of moments of moments is not considered as a balance law, hence is not symmetric. When the balance of moments of moments is used as a balance law, is symmetric, hence . In each case, material coefficients are derived using Taylor series expansion of the coefficients in the linear combination in terms of invariants of the argument tensors and temperature . All material coefficients in these constitutive theories are independent of each other.

2) The constitutive theories are based on integrity (complete basis) and are nonlinear functions of the argument tensors (used in determining the combined generators and the invariants).

3) The restrictions on the material coefficients in the nonlinear constitutive theories are established strictly using the conditions resulting from the entropy inequality requiring the corresponding dissipation functions to be positive.

4) Steps (1) - (3) are based on thermodynamic considerations, hence the constitutive theories and the restrictions on the material coefficients satisfy the entropy inequality.

5) Simplified forms of the linear constitutive theory for used in classical continuum theories for fluent continua are also considered. In this case, Cauchy stress tensor is symmetric and is only a linear function of the symmetric part of the velocity gradient tensor, hence is basis independent. In this constitutive theory (Equation (155)), and are two independent material coefficients. Consideration of yields that and must hold for all arbitrary but admissible choices of . This is consistent when the constitutive theory is nonlinear or when it is for non-classical viscous fluent continua. At this stage, there are no other thermodynamic or constitutive considerations that can be used to establish that and are dependent on each other, that is, they are not independent material coefficients. Based on the work presented here, we are compelled to conclude:

a) Stokes’ hypothesis [55] as originally postulated has no thermodynamic basis because it is not derived using thermodynamic considerations resulting from the entropy inequality.

b) Referring to (156), expressing in terms of (same as deriving constitutive theory for in terms of ) to establish restrictions on the

material coefficients in the constitutive theory for [56] has no ther-

modynamic basis. Thus, the conclusion that based on (156) has no thermodynamic basis either (since , the bulk modulus, one can simply say that, in general, ). We have also shown that if we consider (156) to hold, then as required by the entropy inequality may not hold; hence, this restriction may result in violation of thermodynamic equilibrium. This approach can only be used in linear constitutive theories. The constitutive theories presented here (and in general) based on integrity are nonlinear in which case this approach is not only invalid, but will fail.

In conclusion, the work presented in this paper is thermodynamically consistent and provides a rigorous approach of deriving constitutive theories and of establishing restrictions on the material coefficients for non-classical and classical thermoviscous compressible and incompressible fluent continua. In the case of classical compressible viscous fluids when using linear constitutive theory for deviatoric Cauchy stress tensor, and are the only thermodynamically consistent restrictions on the independent material coefficients and . Furthermore, (Stokes’ hypothesis) and advocated in the literature as a replacement for Stokes’ hypothesis do not have any thermodynamic basis and are in violation of the fundamental conclusion from the derivation of the constitutive theory that and are independent material coefficients. The restrictions on the material coefficients in the non-classical theories for , , and have been derived. These all need to be greater than zero to ensure the dissipation functions to be greater than zero and as required by the entropy inequality.

Acknowledgements

The first and third authors are grateful for the support provided by their endowed professorships during the course of this research. The computational infrastructure provided by the Computational Mechanics Laboratory (CML) of the Mechanical Engineering department of the University of Kansas is gratefully acknowledged.

Cite this paper

Surana, K.S., Joy, A.D. and Reddy, J.N. (2018) Restrictions on the Material Coefficients in the Constitutive Theories for Non-Classical Viscous Fluent Continua. Applied Mathematics, 9, 44-85. https://doi.org/10.4236/am.2018.91005

References

- 1. Surana, K.S., Powell, M.J. and Reddy, J.N. (2015) A More Complete Thermodynamic Framework for Solid Continua. Journal of Thermal Engineering, 1, 1-13.

- 2. Surana, K.S., Powell, M.J., Nunez, D. and Reddy, J.N. (2015) A Polar Continuum Theory for Solid Continua. International Journal of Engineering Research and Industrial Applications, 8, 77-106.

- 3. Surana, K.S., Powell, M.J. and Reddy, J.N. (2015) Constitutive Theories for Internal Polar Thermoelastic Solid Continua. Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics: Advances and Applications, 14, 89-150.

- 4. Surana, K.S., Powell, M.J. and Reddy, J.N. (2015) A More Complete Thermodynamic Framework for Fluent Continua. Journal of Thermal Engineering, 1, 14-30.

- 5. Surana, K.S., Powell, M.J. and Reddy, J.N. (2015) Ordered Rate Constitutive Theories for Internal Polar Thermofluids. International Journal of Mathematics, Science, and Engineering Applications, 9, 51-116.

- 6. Surana, K.S., Reddy, J.N. and Powell, M.J. (2015) A Polar Continuum Theory for Fluent Continua. International Journal of Engineering Research and Industrial Applications, 8, 107-146.

- 7. Surana, K.S., Joy, A.D. and Reddy, J.N. (2016) A Non-Classical Internal Polar Continuum Theory for Finite Deformation of Solids Using First Piola-Kirchhoff Stress Tensor. Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics: Advances and Applications, 16, 1-41.

- 8. Surana, K.S., Joy, A.D. and Reddy, J.N. (2016) A Non-Classical Internal Polar Continuum Theory for Finite Deformation and Finite Strains in Solids. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, 4, 59-97.

- 9. Surana, K.S., Joy, A.D. and Reddy, J.N. (2017) A Non-Classical Continuum Theory for Solids Incorporating Internal Rotations and Rotations of Cosserat Theories. Continuum Mechanics and Thermodynamics, 29, 665-698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00161-017-0554-1

- 10. Surana, K.S., Joy, A.D. and Reddy, J.N. (2017) A Non-Classical Continuum Theory for Fluids Incorporating Internal and Cosserat Rotation Rates. Continuum Mechanics and Thermodynamics, 29, 1249-1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00161-017-0579-5

- 11. Koiter, W. (1964) Couple Stresses in the Theory of Elasticity, I and II. Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie Van Weteschappen: Series B, 67, 17-44.

- 12. Yang, J.F.C. and Lakes, R.S. (1982) Experimental Study of Micropolar and Couple Stress Elasticity in Compact Bone in Bending. Journal of Biomechanics, 15, 91-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(82)90040-9

- 13. Lubarda, V.A. and Markenscoff, X. (2000) Conservation Integrals in Couple Stress Elasticity. Journal of Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 48, 553-564. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5096(99)00039-3

- 14. Ma, H.M., Gao, X.L., and Reddy, J.N. (2008) A Microstructure-Dependent Timoshenko Beam Model Based on a Modified Couple Stress Theory. Journal of Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 56, 3379-3391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmps.2008.09.007

- 15. Ma, H.M., Gao, X.L. and Reddy, J.N. (2010) A Reddy-Levinson Beam Model Based on Modified Couple Stress Theory. Journal of Multiscale Computational Engineering, 8, 167-180. https://doi.org/10.1615/IntJMultCompEng.v8.i2.30

- 16. Reddy, J.N. (2011) Microstructure Dependent Couple Stress Theories of Functionally Graded Beams. Journal of Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 59, 2382-2399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmps.2011.06.008

- 17. Reddy, J.N. and Arbind, A. (2012) Bending Relationship Between the Modified Couple Stress-based Functionally Graded Timoshenko Beams and Homogeneous Bernoulli-Euler Beams. Annals of Solid Structural Mechanics, 3, 15-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12356-012-0026-z

- 18. Srinivasa, A.R. and Reddy, J.N. (2013) A Model for a Constrained, Finitely Deforming Elastic Solid with Rotation Gradient Dependent Strain Energy and Its Specialization to Von Kármán Plates and Beams. Journal of Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 61, 873-885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmps.2012.10.008

- 19. Lazar, M. and Maugin, G.A. (2004) Defects in Gradient Micropolar Elasticity I: Screw Dislocation. Journal of Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 52, 2263-2284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmps.2004.04.003

- 20. Eringen, A.C. (1964) Mechanics of Micromorphic Materials. Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Applied Mechanics, 131-138.

- 21. Eringen, A.C. (1968) Mechanics of Micromorphic Continua, in Mechanics of Generalized Continua. E. Kroner Ed., Spring-Verlag, Berlin, 18-35. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-30257-6_2

- 22. Eringen, A.C. (1968) Theory of Micropolar Elasticity, in Fracture. H. Liebowitz Ed., Academic Press, Cambridge, 621-729.

- 23. Eringen, A.C. (1970) Balance Laws of Micromorphic Mechanics. International Journal of Engineering Science, 8, 819-828.

- 24. Eringen, A.C. (1990) Theory of Thermo-Microstretch Fluids and Bubbly Liquids. International Journal of Engineering Science, 28, 133-143.

- 25. Eringen, A.C. (1999) Microcontinuum Field Theories. Springer US, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-0555-5

- 26. Eringen, A.C. (1966) A Unified Theory of Thermomechanical Materials. International Journal of Engineering Science, 4, 179-202.

- 27. Eringen, A.C. (1967) Linear Theory of Micropolar Viscoelasticity. International Journal of Engineering Science, 5, 191-204.

- 28. Eringen, A.C. (1972) Theory of Micromorphic Materials with Memory. International Journal of Engineering Science, 10, 623-641.

- 29. Surana, K.S., Shanbhag, R.S. and Reddy, J.N. (2017) Necessity of Balance of Moments of Moments Balance Law in Non-Classical Continuum Theories for Solid Continua Meccanica. (Submitted)

- 30. Surana, K.S., Long, S.W. and Reddy, J.N. (2017) Necessity of Balance of Moments of Moments Balance Law in Non-Classical Continuum Theories for Fluent Continua. Acta Mechanica. (Submitted)

- 31. Yang, F., Chong, A.C.M., Lam, D.C.C. and Tong, P. (2002) Couple Stress Based Strain Gradient Theory for Elasticity. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 39, 2731-2743.

- 32. Surana, K.S. (2015) Advanced Mechanics of Continua. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton.

- 33. Surana, K.S., Ma, Y., Reddy, J.N. and Romkes, A. (2010) The Rate Constitutive Equations and their Validity for Progressively Increasing Deformation. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, 17, 509-533.

- 34. Eringen, A.C. (1967) Mechanics of Continua. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey.

- 35. Wang, C.C. (1969) On Representations for Isotropic Functions, Part I. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 33, 249. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00281278

- 36. Wang, C.C. (1969) On Representations for Isotropic Functions, Part II. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 33, 268. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00281279

- 37. Wang, C.C. (1970) A New Representation Theorem for Isotropic Functions, Part I and Part II. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 36, 166-223. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00272241

- 38. Wang, C.C. (1971) Corrigendum to “Representations for Isotropic Functions”. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 43, 392-395. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00252004

- 39. Smith, G.F. (1970) On a Fundamental Error in Two Papers of C.C. Wang, “On Representations for Isotropic Functions, Part I and Part II”. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 36, 161-165. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00272240

- 40. Smith, G.F. (1971) On Isotropic Functions of Symmetric Tensors, Skew-Symmetric Tensors and Vectors. International Journal of Engineering Science, 9, 899-916.

- 41. Spencer, A.J.M. and Rivlin, R.S. (1959) The Theory of Matrix Polynomials and Its Application to the Mechanics of Isotropic Continua. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 2, 309-336.

- 42. Spencer, A.J.M. and Rivlin, R.S. (1960) Further Results in the Theory of Matrix Polynomial. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 4, 213-230.

- 43. Spencer, A.J.M. (1971) Theory of Invariants. Academic Press, Cambridge, 239-253. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-240801-4.50008-X

- 44. Boehler, J.P. (1977) On Irreducible Representations for Isotropic Scalar Functions. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics, 57, 323-327.

- 45. Zheng, Q.S. (1993) On the Representations for Isotropic Vector-Valued, Symmetric Tensor-Valued and Skew-Symmetric Tensor-Valued Functions. International Journal of Engineering Science, 31, 1013-1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7225(93)90109-8

- 46. Zheng, Q.S. (1993) On Transversely Isotropic, Orthotropic and Relatively Isotropic Functions of Symmetric Tensors, Skew-Symmetric Tensors, and Vectors. International Journal of Engineering Science, 31, 1399-1453.

- 47. Reiner, M. (1945) A Mathematical Theory of Dilatancy. American Journal of Mathematics, 67, 350-362.

- 48. Rivlin, R.S. and Ericksen, J.L. (1955) Stress-Deformation Relations for Isotropic Materials. Journal of Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 4, 323-425.

- 49. Todd, J.A. (1948) Ternary Quadratic Types. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 341, 399-456. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.1948.0025

- 50. Rivlin, R.S. (1955) Further Remarks on the Stress-Deformation Relations for Isotropic Materials. Journal of Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 4, 681-702.

- 51. Hill, R. (1968) On Constitutive Inequalities for Simple Materials—I. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 16, 229-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5096(68)90031-8

- 52. Hill, R. (1968) On Constitutive Inequalities for Simple Materials—II. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 16, 315-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5096(68)90018-5

- 53. Hill, R. (1970) Constitutive Inequalities for Isotropic Elastic Solids under Finite Strain. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A, 314, 457-472. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1970.0018

- 54. Hill, R. (1978) Aspects of Invariance in Solid Mechanics. Advances in Applied Mechanics, 18, 1-75.

- 55. Stokes, G.G. (1845) On the Theories of Internal Friction of Fluids in Motion and of the Equilibrium and Motion of Elastic Solids. Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 8, 287-305.