Applied Mathematics

Vol.4 No.10A(2013), Article ID:37402,9 pages DOI:10.4236/am.2013.410A1005

Equivalence of Subclasses of Two-Way Non-Deterministic Watson Crick Automata

Electronics and Communication Science Unit, ISI, Kolkata, India

Email: ksray@isical.ac.in, kingshukchaterjee@gmail.com, debayan3737@gmail.com

Copyright © 2013 Kumar Sankar Ray et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received June 5, 2013; revised July 5, 2013; accepted July 12, 2013

Keywords: Non-Deterministic Watson Crick Automata; Two-Way Non-Deterministic Watson Crick Automata; RE Languages

ABSTRACT

Watson Crick automata are finite automata working on double strands. Extensive research work has already been done on non deterministic Watson Crick automata and on deterministic Watson Crick automata. Parallel Communicating Watson Crick automata systems have been introduced by E. Czeziler et al. In this paper we discuss about a variant of Watson Crick automata known as the two-way Watson Crick automata which are more powerful than non-deterministic Watson Crick automata. We also establish the equivalence of different subclasses of two-way Watson crick automata. We further show that recursively enumerable (RE) languages can be realized by an image of generalized sequential machine (gsm) mapping of two-way Watson-Crick automata.

1. Introduction

The tremendous progress in biotechnology has resulted in decoding of DNA sequences, synthesizing and manipulating DNA, which lead to its usage in computation by computer scientists. As a result sticker systems, splicing systems and carving systems came into existence [1]. Many of the NP-complete problems were solved efficiently using DNA computing. The first, the Adleman experiment was done in 1994 [2]. As the interest in using DNA in computation increased so did the need for automata which exploit the properties of DNA. The first such automata which exploited the DNA property were the Watson-Crick automata [3] which are the automata counterpart of the Sticker Systems. Essentially Watson-Crick automata are finite automata having two independent heads working on double strands where the characters on the corresponding positions of the two strands are connected by a complementarity relation similar to the Watson-Crick complementarity relation.

The movement of the heads although independent of each other is controlled by a single state.

Details of several variants of non-deterministic Watson-Crick automata have been explored in [4].

Deterministic Watson-Crick automata and their variants have been explicitly handled in [5,6]. Parallel Communicating Watson-Crick automata were introduced in [7] and further investigated in [8]. A survey of WatsonCrick automata can be found in [9]. The effect of the complementarity relation on the computing power of Watson Crick automata is discussed in [10].

Two-way finite automaton (FA) is an abstract machine, a generalized version of the finite automaton which can revisit characters already processed. As in FA, in twoway FA there are finite number of states with transitions between them based on the current character; but each transition is also labeled with a value indicating whether the machine will move its reading head to the left, right, or stay at the same position. Equivalently, 2FAs can be seen as read-only Turing machines with no work tape; only a read-only input tape. The accepting condition is that when the reading head falls off the right end of the tape and the state in which the machine is at that time is final state then the input word is accepted. A twoway Watson Crick automaton (2AWK) is similar in concept to a two-way finite automaton. The only difference between them is that in two-way Watson Crick automata the input tape is double stranded. The idea of two-way Watson Crick automata were introduced in [4] but no comparison of its power with respect to AWK was discussed. The importance of 2AWK is that unlike two-way FA which is equal in power to a FA, 2AWK are more powerful than AWK which we establish in this paper.

In this paper, we give a general description of non-deterministic Watson Crick automata and its different subclasses in Sections 2 and 3. In Section 4 we describe the twin shuffle language and state the relation of twin shuffle language with RE languages. In the following section we state the rules governing two-way non-deterministic Watson Crick automata. In Section 6 we give the definition of the different classes (variants) of 2AWK and investigate the relationship between classes of 2AWK automata. We show that 2AWK = 2SWK = 21WK = 2FWK = 2FSWK = 2F1WK similar to the case of Watson Crick automata. We further show the family of languages accepted by 2AWK is context sensitive. In Section 7 we show that two-way non-deterministic Watson Crick automata are more powerful than non-deterministic Watson Crick automata. In Section 9 we further show that recursively enumerable (RE) languages can be realized by an image of generalized sequential machine (gsm) mapping of two-way Watson-Crick automata.

2. Basic Terminology for Watson-Crick Automata

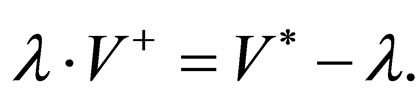

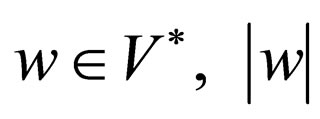

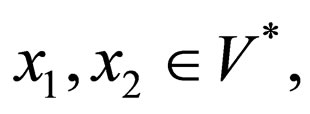

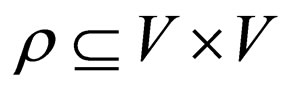

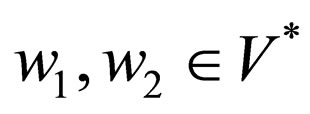

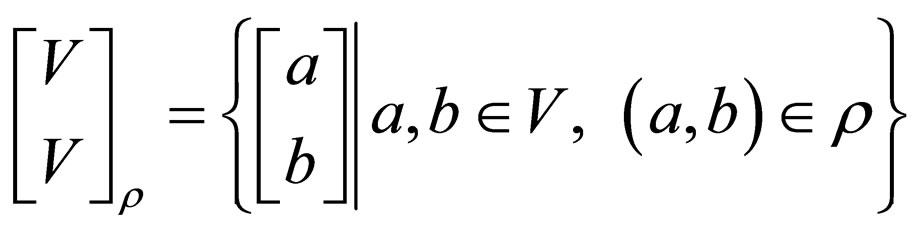

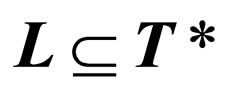

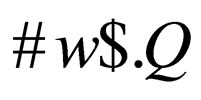

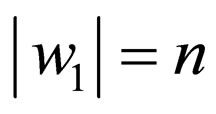

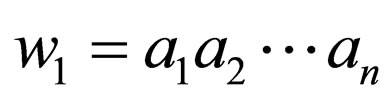

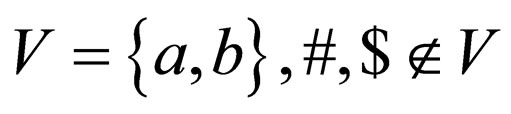

V is a finite alphabet. V* denotes the set of all finite words over V, including the empty word For

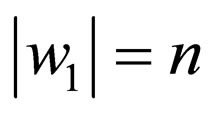

For  denotes the length of w. Let

denotes the length of w. Let  and

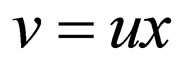

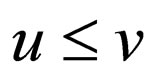

and  be two words and if there is some word

be two words and if there is some word , such that

, such that , then u is the prefix of v, denoted by

, then u is the prefix of v, denoted by . Two words, u and v are prefix comparable denoted by u~pv if u is a prefix of v or vice versa.

. Two words, u and v are prefix comparable denoted by u~pv if u is a prefix of v or vice versa.

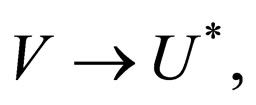

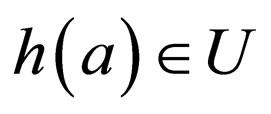

Given two alphabets V and U a mapping h:

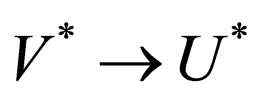

extended to s:

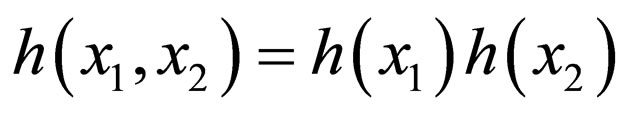

extended to s:  by

by  and

and  for

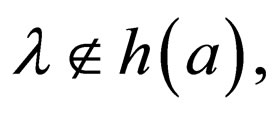

for  is called a morphism. If

is called a morphism. If  for each

for each , then h is a λ free morphism.

, then h is a λ free morphism.

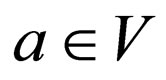

A morphism h:  is called a coding if

is called a coding if for each

for each  and a weak coding if

and a weak coding if for each

for each  If

If  is the morphism defined by

is the morphism defined by  for

for , and

, and  otherwise, then we say that h is a projection (associated with

otherwise, then we say that h is a projection (associated with ) and we denote it by prV1.

) and we denote it by prV1.

For  we define their shuffle by

we define their shuffle by

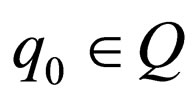

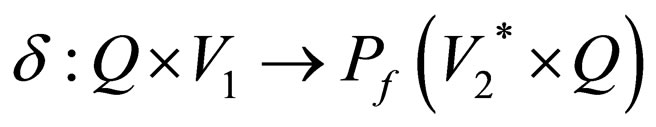

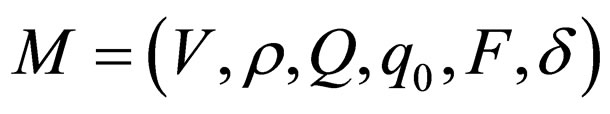

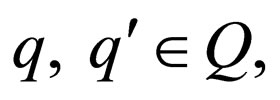

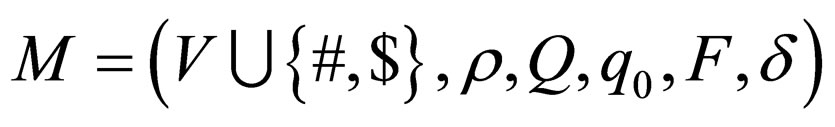

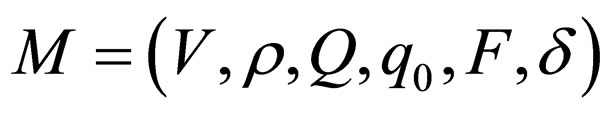

A generalized sequential machine (gsm) is a sequential transducer. Such a device is a system where Q is the set of states,

where Q is the set of states,  are the alphabets(input and output alphabets) of the automaton,

are the alphabets(input and output alphabets) of the automaton,  is the initial state,

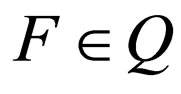

is the initial state,  is the set of final states and

is the set of final states and  is the transition mapping.

is the transition mapping.

The definitions of morphism, gsm and shuffle are stated in [1].

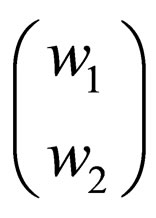

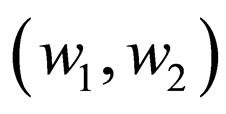

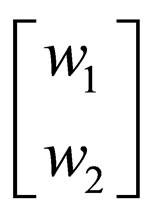

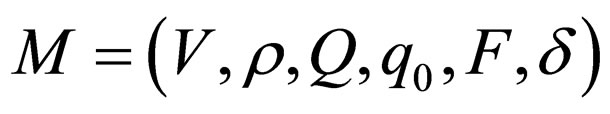

A Watson-Crick automaton is a 6-tuple of the form  where

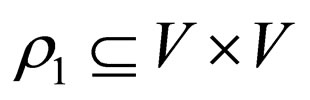

where  is an alphabet set,

is an alphabet set,  is a set of states,

is a set of states,  is the complementarity relation similar to Watson Crick complementarity relation and q0 is the initial state and

is the complementarity relation similar to Watson Crick complementarity relation and q0 is the initial state and  is the set of final states. The function

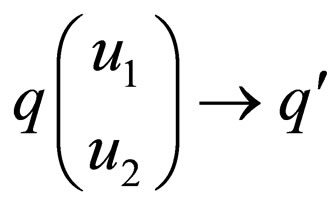

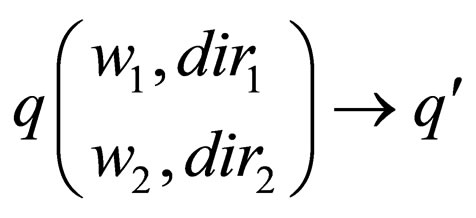

is the set of final states. The function  contains a finite number of transition rules of the form

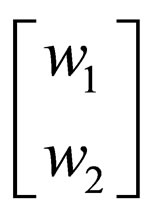

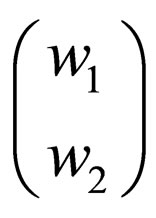

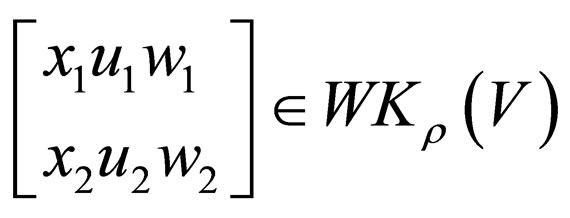

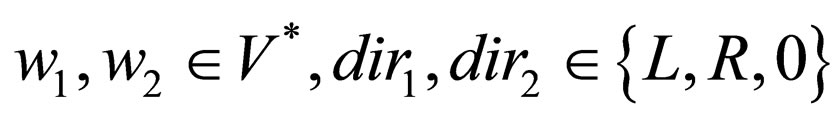

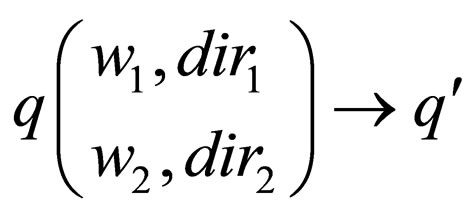

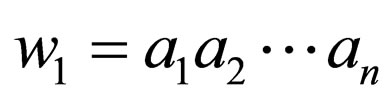

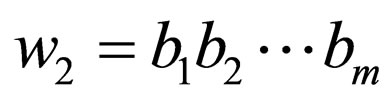

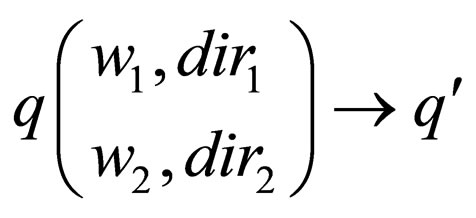

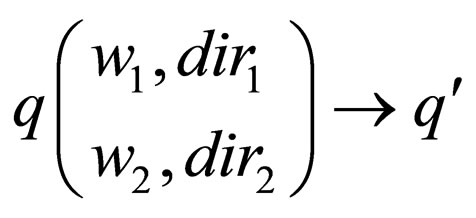

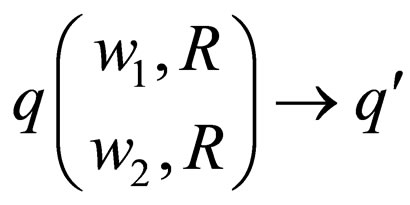

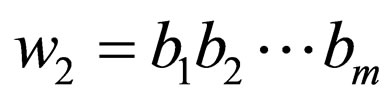

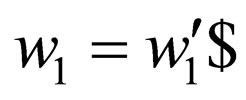

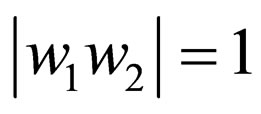

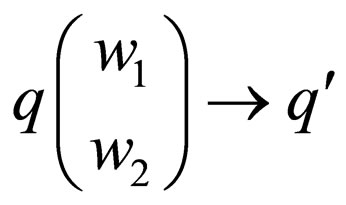

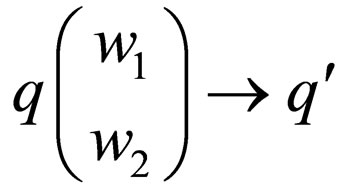

contains a finite number of transition rules of the form , which denotes that the machine in state q parses w1 in upper strand and w2 in lower strand and goes to state

, which denotes that the machine in state q parses w1 in upper strand and w2 in lower strand and goes to state  where

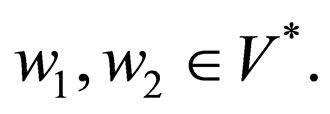

where .

.  is different from

is different from .

.  is just a pair of strings written in that form instead of

is just a pair of strings written in that form instead of whereas in

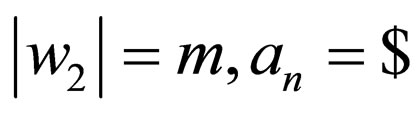

whereas in  the two strands are of same length i.e.

the two strands are of same length i.e.  and the corresponding symbols in two strands are complementarity in the sense of relation ρ.

and the corresponding symbols in two strands are complementarity in the sense of relation ρ.

and

and

.

.

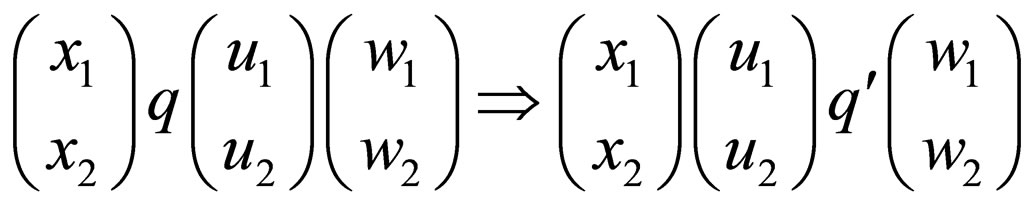

A transition in a Watson-Crick finite automaton can be defined as follows:

For,  such that

such that

and

and

iff there is transition rule

iff there is transition rule  in

in .

.

denotes the transitive and reflexive closure of

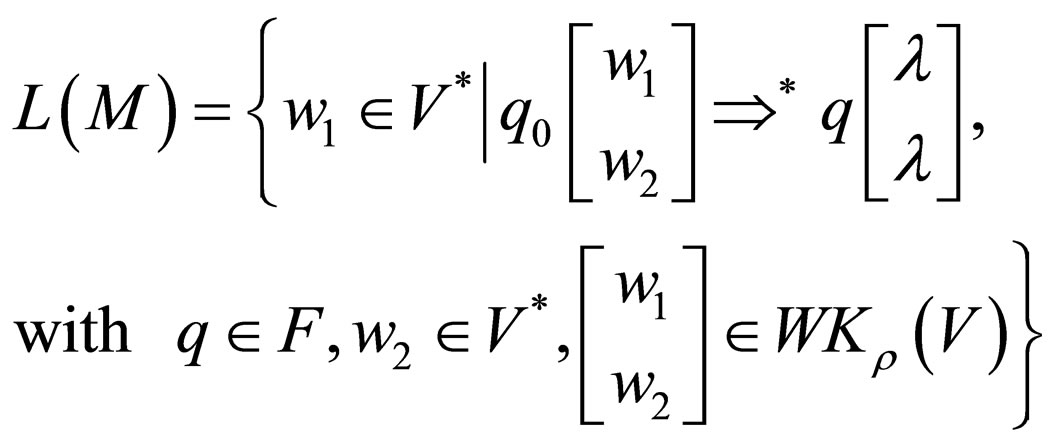

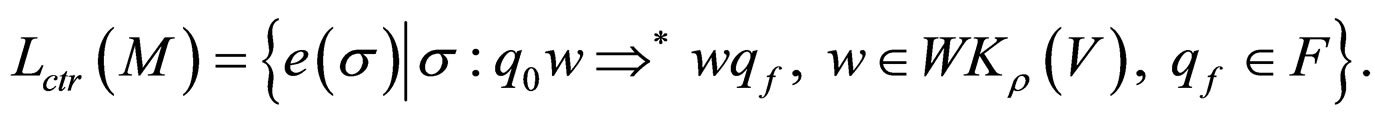

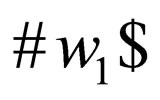

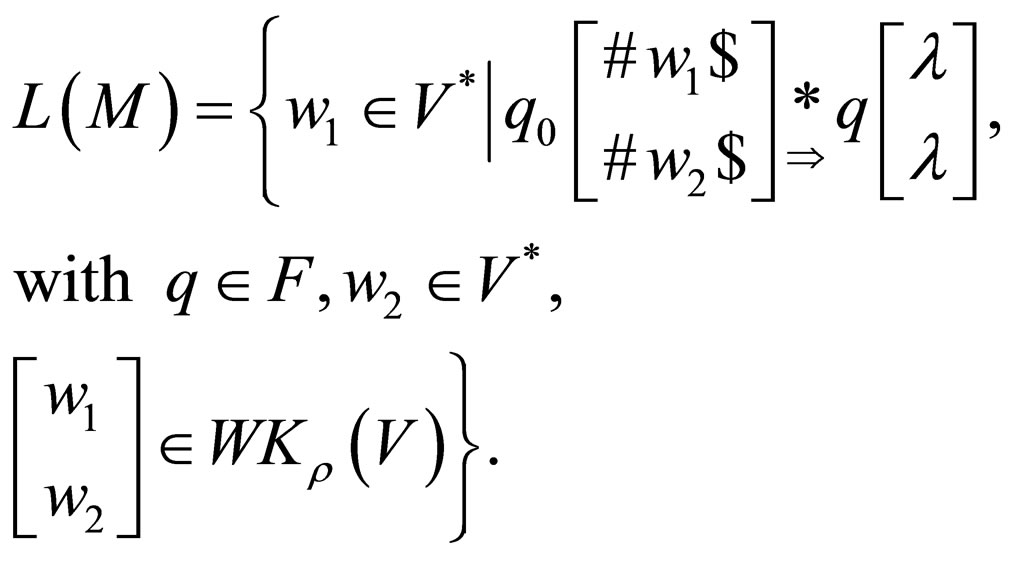

denotes the transitive and reflexive closure of .The language accepted by Watson-Crick Automata is

.The language accepted by Watson-Crick Automata is

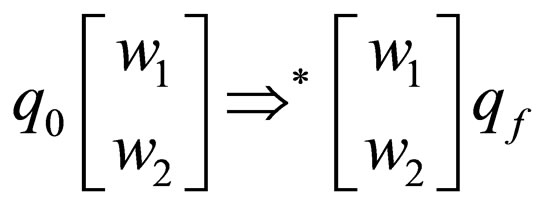

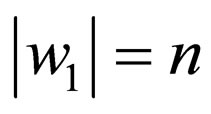

For a Watson-Crick Automaton M, with input where w1 is any string in V* and

where w1 is any string in V* and  where q0 is the initial state and qf is a final state. Then

where q0 is the initial state and qf is a final state. Then  is a computation in M denoted by

is a computation in M denoted by .

.

Another important language associated with WatsonCrick automaton is defined taking into consideration the transitions and not the language recognised.

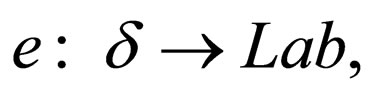

For a Watson-Crick Automaton  consider a labeling

consider a labeling of rules in

of rules in  with elements in a set Lab. For computation

with elements in a set Lab. For computation denoted by

denoted by the control word of

the control word of , that is the sequence of labels of transition rules used in

, that is the sequence of labels of transition rules used in . In this way the language is obtained.

. In this way the language is obtained.

The definition of  is stated in [4].

is stated in [4].

3. Subclasses of Non-Deterministic Watson-Crick Automata (AWK)

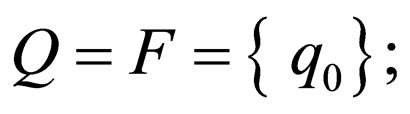

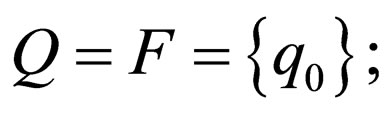

Depending on the type of states and transition rules there are four types or subclasses of Watson-Crick Automata. Watson-Crick Automaton  is

is

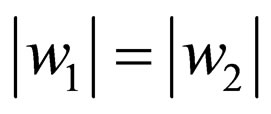

1) stateless (NWK): If it has only one state, i.e.

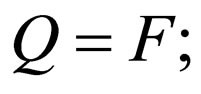

2) all-final (FWK): If all the states are final, i.e.

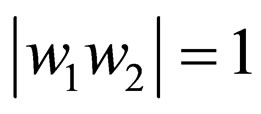

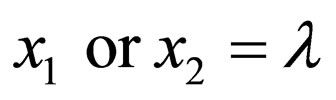

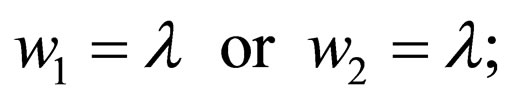

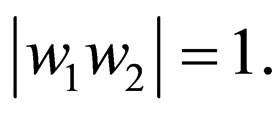

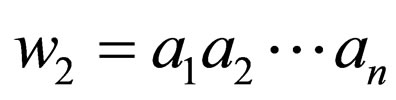

3) simple (SWK): If at each step the automaton reads either from the upper strand or from the lower strand, i.e. for any transition rule

4) 1-limlited (1WK): If for any transition rule q

, we have

, we have .

.

Theorem 1: Simple and 1 limited Watson-Crick automata accept the same family of languages as the family of languages accepted by Watson-Crick automata with arbitrary transition rules.

The proof of Theorem 1 is in [4].

Theorem 2: Non-deterministic Watson-Crick automata are equivalent with non-deterministic simple Watson-Crick automata.

Corollary 1: Non-deterministic Watson-Crick automata are equivalent with non-deterministic 1-limited Watson-Crick automata.

The proof of Theorem 2 and Corollary 1 are given in [4].

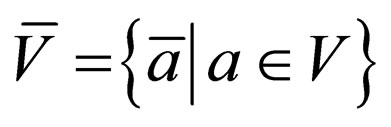

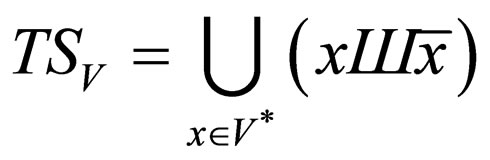

4. Twin-Shuffle Language

Consider an alphabet V and its barred variant, . The language

. The language

is called the twin-shuffle language over . (For a string

. (For a string  denotes the string obtained by replacing each symbol in x with its barred variant).

denotes the string obtained by replacing each symbol in x with its barred variant).

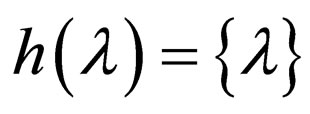

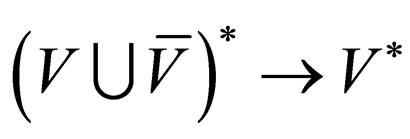

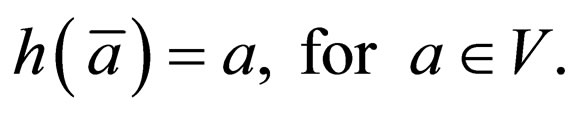

For the morphism h:  defined by

defined by

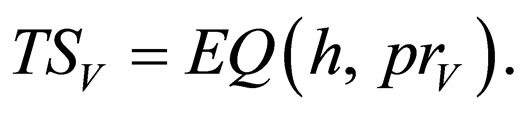

Clearly the equality is

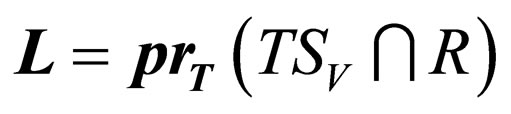

Theorem 3: Each recursively enumerable language  can be written in the form

can be written in the form  , where

, where  is an alphabet and R is a regular language.

is an alphabet and R is a regular language.

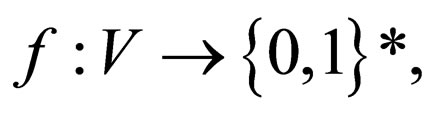

In this representation, the language TSV depends on the language L. This can be avoided in the following way:

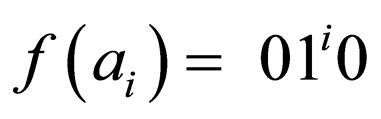

Let a coding be  for instance,

for instance, , where

, where  is the

is the  symbol of

symbol of  in a specified ordering. The language

in a specified ordering. The language  is regular. A generalized sequential machine

is regular. A generalized sequential machine  can simulate the intersection with a regular language, the projection

can simulate the intersection with a regular language, the projection  as well as the decoding of elements in

as well as the decoding of elements in  Thus we obtain:

Thus we obtain:

Corollary 2: For each recursively enumerable language  there is a gsm gL such that

there is a gsm gL such that

Therefore, by using a sequential transducer which can be a deterministic one, we can obtain all recursively enumerable language, starting from the unique language  Proofs of Theorem 3 and Corollary 2 are in [1].

Proofs of Theorem 3 and Corollary 2 are in [1].

5. Two-Way Non-Deterministic Watson Crick Automata (2AWK)

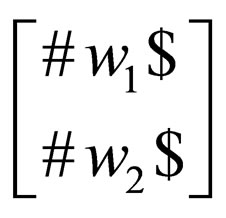

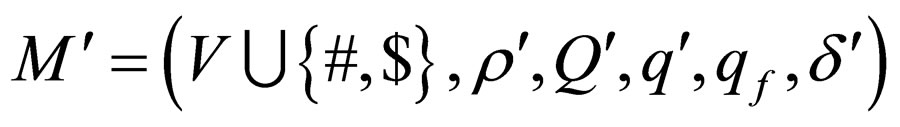

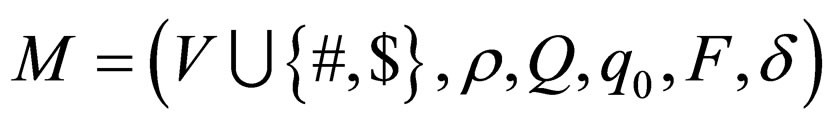

Two-way non-deterministic Watson Crick automata system is a 6 tuple,  where

where  is a set of alphabet,

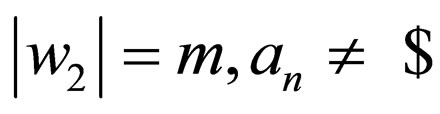

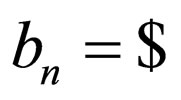

is a set of alphabet,  are the beginning and the end marker respectively; that is the word w to be recognized is provided as an input to the automaton in the form

are the beginning and the end marker respectively; that is the word w to be recognized is provided as an input to the automaton in the form  is a set of states,

is a set of states,  and

and  and

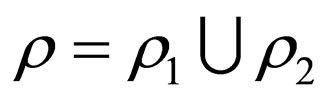

and  is the complementarity relation and

is the complementarity relation and  is the initial state and

is the initial state and  is the set of final states.

is the set of final states.  is the finite number of transition rules;

is the finite number of transition rules;

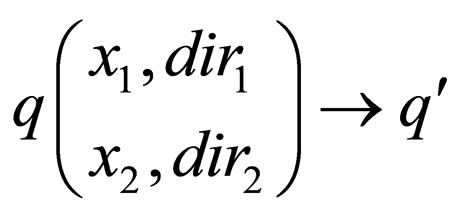

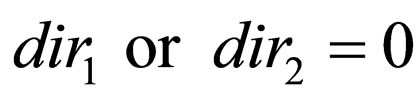

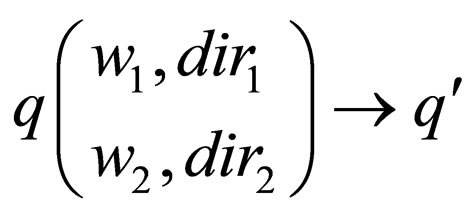

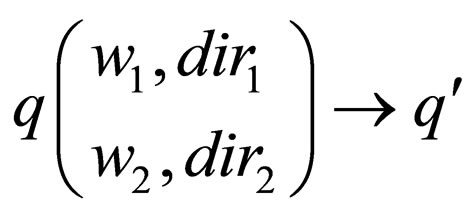

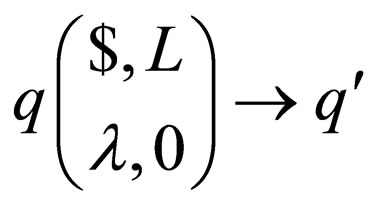

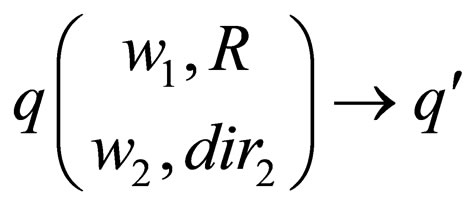

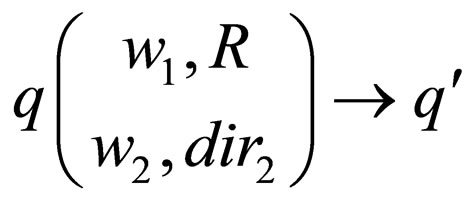

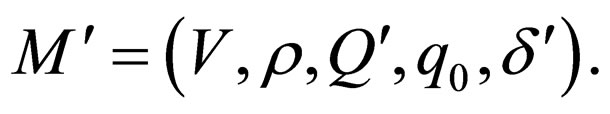

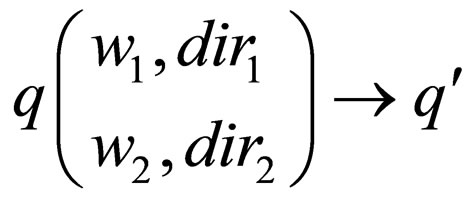

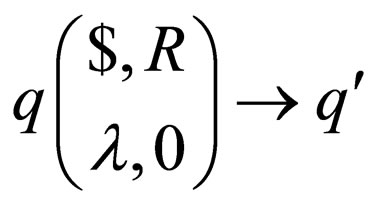

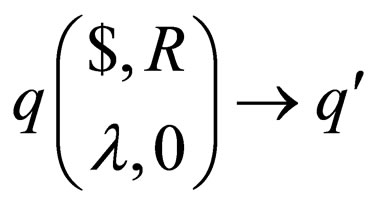

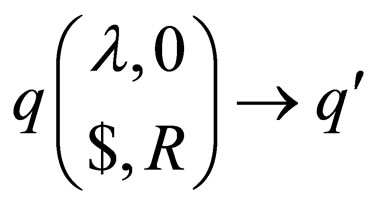

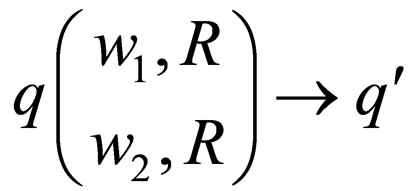

1) either of the form , which denotes that the machine in state q parses

, which denotes that the machine in state q parses  in upper strand in dir1 direction and

in upper strand in dir1 direction and  in lower strand in dir2 direction and goes to state

in lower strand in dir2 direction and goes to state  where

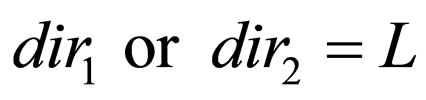

where where L signifies that the head is reading the word in the left direction, R signifies that the head is reading the word in right direction and if a head reads the empty word

where L signifies that the head is reading the word in the left direction, R signifies that the head is reading the word in right direction and if a head reads the empty word  it remains in its current position denoted by 0.

it remains in its current position denoted by 0.

2) or of the forms , where

, where and

and  with restrictions that when

with restrictions that when  the corresponding

the corresponding and when

and when  the corresponding

the corresponding . Moreover, there cannot be transition rules having the form

. Moreover, there cannot be transition rules having the form  where

where where

where  and

and  or

or  where

where  and

and  or both. These rules ensure that the reading heads do not go past the input word on the left side or the heads do not move when it reads empty word. Moreover once a head goes past the right end of the tape it cannot comeback.

or both. These rules ensure that the reading heads do not go past the input word on the left side or the heads do not move when it reads empty word. Moreover once a head goes past the right end of the tape it cannot comeback.

Accepting conditions

is accepted by

is accepted by  if, starting in state

if, starting in state  (initial state) with

(initial state) with  and

and  on the double stranded input tape and the two heads at the left end of

on the double stranded input tape and the two heads at the left end of  and

and  respectively,

respectively,  eventually enters a final state at the same time both the heads fall off the right hand side of the double stranded input tape.

eventually enters a final state at the same time both the heads fall off the right hand side of the double stranded input tape.

The word  is rejected if one of the following 3 conditions occurs:

is rejected if one of the following 3 conditions occurs:

1) The two-way WK automaton goes into a loop which is identified in a similar way as loops in two-way FAs are identified.

2) When both the heads fall off the right hand side of the input tape and the machine is in a non final state.

3) If the machine comes to a halt (i.e. there are no transition rules that can be applied for that particular state in which the machine is) before the heads fall off the right hand side of the input tape.

i.e. mathematically

6. Subclasses of Two-Way Non-Deterministic Watson-Crick Automata (2AWK)

Depending on the type of states and transition rules there are four types or subclasses of two-way Watson-Crick Automata similar to Watson Crick automata.

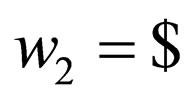

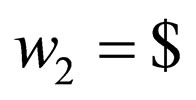

2-way Watson-Crick Automaton

is

is

1) stateless (2NWK): If it has only one state, i.e.

2) all-final (2FWK): If all the states are final, i.e.

3) simple (2SWK): If at each step the automaton reads either from the upper strand or from the lower strand, i.e.for any transition rule  either

either

4) 1-limlited (21WK): If for any transition rule , we have

, we have

Many combinations of these classes can also be obtained such as all-final simple two-way WK automata (2FSWK), all final 1 limited two-way WK automata (21FWK), stateless 1 limited two-way WK automata (21NWK) etc.

Theorem 4: Simple and 1 limited two-way Watson Crick automata accept the same family of languages as the family of languages accepted by two-way Watson Crick automata with arbitrary transition rules.

The proof of theorem is similar to the proof done in [4] for Theorem 1.

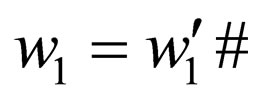

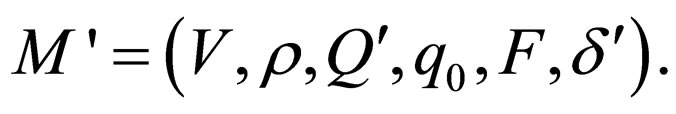

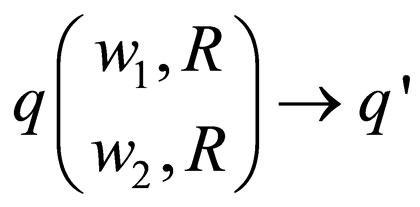

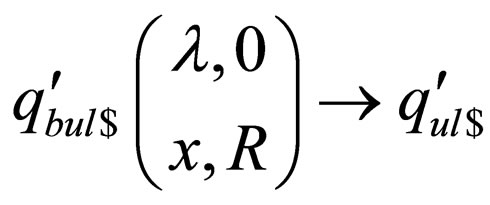

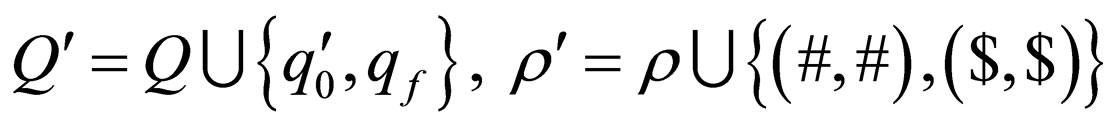

Let  be a non-deterministic two-way Watson Crick automaton. We introduce a 1 limited two-way Watson Crick automaton

be a non-deterministic two-way Watson Crick automaton. We introduce a 1 limited two-way Watson Crick automaton For each transition rule t of the form

For each transition rule t of the form  in

in  where

where  where

where  and

and  where

where  and

and  the condition

the condition  is imposed because rules with

is imposed because rules with  is already in the 1-limited form and no further modification is required for them. We introduce new rules in

is already in the 1-limited form and no further modification is required for them. We introduce new rules in  of the form

of the form

.

.

All the new states are introduced in Q’ along with states in Q. From the construction of M’ which is obtained from M it is obvious that both M’ and M recognize the same language. So 2AWK are subset of 21WK and from the definition of 21WK and AWK we know that 21WK are subset of 2AWK. So 2AWK and 21WK are equivalent i.e. they accept the same family of languages. A similar proof can also be established for 2SWK. Therefore we can say, 2AWK = 2SWK = 21WK.

Theorem 5: All final two-way Watson Crick automata accept the same family of languages as the family of languages accepted by two-way Watson Crick automata with arbitrary transition rules.

Let  be a two-way non-deterministic Watson Crick automaton. We introduce an all final two-way Watson Crick automaton

be a two-way non-deterministic Watson Crick automaton. We introduce an all final two-way Watson Crick automaton Each transition rule t of the form

Each transition rule t of the form  in δ where

in δ where  where

where and

and  where

where  falls under one of the five classes. The classes are defined as follows:

falls under one of the five classes. The classes are defined as follows:

Class 1: Transition rules of the form

in

in  where

where  where

where and

and  where

where  and

and  and

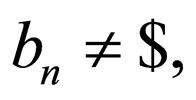

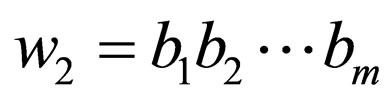

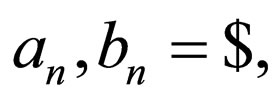

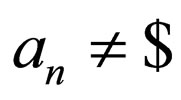

and  i.e. w1 and w2 do not have $ at their ends.

i.e. w1 and w2 do not have $ at their ends.

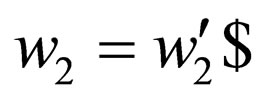

Class 2: Transition rules of the form

in

in  where

where  where

where  and

and

where

where , and

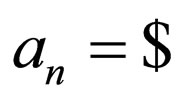

, and  i.e.

i.e.  and

and  both have $ at their ends.

both have $ at their ends.

Class 3: Transition rules of the form

in

in  where

where  where

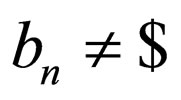

where

and

and  where

where  and

and  i.e.

i.e.  has

has  at its end and

at its end and  does not have

does not have  at its end.

at its end.

Class 4: Transition rules of the form

in

in  where

where  where

where  and

and where

where  and

and  i.e.

i.e.  does not have

does not have  at its end and

at its end and  has

has  at its end.

at its end.

Class 5: Either transition rules of the form

in

in  or transition rules of the form

or transition rules of the form

in

in  or transition rules of the form

or transition rules of the form  in

in .

.

The transition rules of  are modified as follows to form the transition rules of

are modified as follows to form the transition rules of .

.

Transition rules of  which fall in class 1 and class 5 are kept same in

which fall in class 1 and class 5 are kept same in .

.

For transition rules of  which belong to class 2 two instances can occur;

which belong to class 2 two instances can occur;

case 1: For transition , where

, where  is a final state. In this case the transition rules are kept same in

is a final state. In this case the transition rules are kept same in .

.

case 2: For transition , where

, where  is a non final state. In this case the transition rules of

is a non final state. In this case the transition rules of  are modified as follows for

are modified as follows for .

.

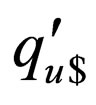

For each transition rule  in

in  belonging to class 2 where

belonging to class 2 where  is a non final state,

is a non final state, where

where  and

and  are introduced in

are introduced in  and there is no transition from

and there is no transition from  in

in . These new rules in

. These new rules in  ensure that if the heads go off the right end of the tape in

ensure that if the heads go off the right end of the tape in  when

when  is in a non final state then

is in a non final state then  would go to state

would go to state  and would not accept the string as there is no transition from

and would not accept the string as there is no transition from  i.e. the above stated rules ensure the heads do not fall off the right end of the tape for

i.e. the above stated rules ensure the heads do not fall off the right end of the tape for  when

when  does not accept the word. As

does not accept the word. As  is all final if the heads go off the right end of the tape it will accept the given string.

is all final if the heads go off the right end of the tape it will accept the given string.

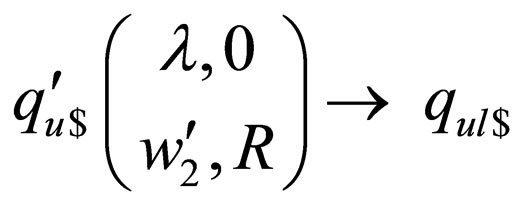

For transition rules of  which belong to class 3 the following modifications are needed. Class 3 also has two instances similar to class 2.

which belong to class 3 the following modifications are needed. Class 3 also has two instances similar to class 2.

case 1: For transition , where

, where  is a final state. In this case the transition rules are kept same in

is a final state. In this case the transition rules are kept same in .

.

case 2: For transition , where

, where  is a non final state. In this case the transition rules of

is a non final state. In this case the transition rules of  are modified as follows for

are modified as follows for .

.

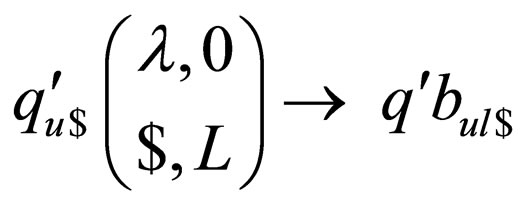

For each transition rule  in

in  belonging to class 3 where

belonging to class 3 where  is a non final state,

is a non final state, where

where  is introduced in

is introduced in where

where  denotes that the head on the upper strand has gone past the right end marker

denotes that the head on the upper strand has gone past the right end marker  in the original machine

in the original machine  on application of the above transition rule.

on application of the above transition rule.

Only rules having λ on the upper strand are applied to  because in the actual machine

because in the actual machine  if the above rules of class 3 are applied then the upper head would have gone past the right end of the tape. So only rules having λ on the upper head can be applied to the machine

if the above rules of class 3 are applied then the upper head would have gone past the right end of the tape. So only rules having λ on the upper head can be applied to the machine . As

. As  replicates

replicates  similar thing is done in

similar thing is done in  too.

too.

Thus, all the transition rules that can be applied to  in

in  with

with  on the upper strand and

on the upper strand and  and

and  in the lower strand can also be applied to

in the lower strand can also be applied to  in

in . Rules having

. Rules having  on the upper strand and

on the upper strand and  and

and  in the lower strand where the transition goes to a final state are applied to

in the lower strand where the transition goes to a final state are applied to . Finally for rules with

. Finally for rules with  on the upper strand and

on the upper strand and and

and  in the lower strand where the transition goes to a non final state, the rules of the form

in the lower strand where the transition goes to a non final state, the rules of the form  where

where  are introduced in

are introduced in  and there are no transition rules from

and there are no transition rules from  These rules ensure that when M reaches the end of the string on a non final state then

These rules ensure that when M reaches the end of the string on a non final state then  goes to

goes to  and

and  does not accept the string as there is no transition from

does not accept the string as there is no transition from  i.e. the above stated rules ensure the heads do not fall off the right end of the tape for

i.e. the above stated rules ensure the heads do not fall off the right end of the tape for  when heads off M fall off the right end and the state to which M goes is non final.

when heads off M fall off the right end and the state to which M goes is non final.

Class 4 rules are handled in a similar way to class 3 rules.

It is obvious from the transition rules introduced in  that

that  accepts the same family of languages as M.

accepts the same family of languages as M.

Thus, 2FWK = 2AWK.

Theorem 6: All final 1 limited two-way Watson Crick automata accept the same family of languages as the family of languages accepted by 1 limited twoway Watson Crick automata with arbitrary transition rules.

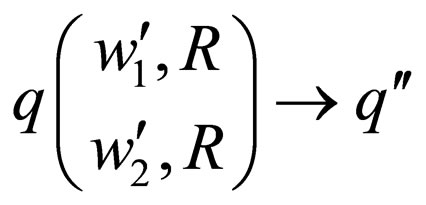

Let  be a two-way 1 limited non-deterministic Watson Crick automaton. We introduce an all final 1 limited two-way Watson Crick automaton

be a two-way 1 limited non-deterministic Watson Crick automaton. We introduce an all final 1 limited two-way Watson Crick automaton  Each transition rule t of the form

Each transition rule t of the form  in

in  where

where  falls under one of the four classes. The classes are defined as follows:

falls under one of the four classes. The classes are defined as follows:

Class 1: Transition rules of the form

in

in  where

where

Class 2: Transition rules of the form

in

in .

.

Class 3: Transition rules of the form

in

in .

.

Class 4: Transition rules of the form

in

in  or transition rules of the form

or transition rules of the form  in

in

The transition rules of  are modified as follows to form the transition rules of

are modified as follows to form the transition rules of .

.

Transition rules of  which fall in class 1 and class 4 are kept same in

which fall in class 1 and class 4 are kept same in .

.

For transition rules of  which belong to class 2 have two instances.

which belong to class 2 have two instances.

case 1: For transition , where

, where  is a final state. In this case the transition rules are kept same in

is a final state. In this case the transition rules are kept same in .

.

case 2: For transition , where

, where  is a non final state. In this case the transition rules of

is a non final state. In this case the transition rules of  are modified as follows for

are modified as follows for .

.

For each transition rule  in

in  belonging to class 2 where

belonging to class 2 where  is a non final state,

is a non final state, and

and  where

where  are introduced in

are introduced in .

.  denotes that the head on the upper strand has gone past the right end marker

denotes that the head on the upper strand has gone past the right end marker  in the original machine

in the original machine .

.

Only rules having  on the upper strand can be applied to

on the upper strand can be applied to  (for reasons similar to reasons stated in proof of Theorem 5). Thus, all the transition rules that can be applied to

(for reasons similar to reasons stated in proof of Theorem 5). Thus, all the transition rules that can be applied to  with

with  on the upper strand and

on the upper strand and  in the lower strand are applied to

in the lower strand are applied to . For rules having

. For rules having  on the upper strand and

on the upper strand and  in the lower strand where the transition goes to a final state are applied to

in the lower strand where the transition goes to a final state are applied to . Finally for rules with

. Finally for rules with  on the upper strand and

on the upper strand and  in the lower strand where the transition goes to a non final state in

in the lower strand where the transition goes to a non final state in , the rules of the form

, the rules of the form and

and , where

, where are introduced in

are introduced in . These rules ensure that when

. These rules ensure that when  reaches the end of the string on a non final state,

reaches the end of the string on a non final state,  does not accept the string as there are no transitions from state

does not accept the string as there are no transitions from state

Class 3 is handled in a similar way as class 2.

It is obvious from the transition rules introduced in  that

that  accepts the same family of languages as

accepts the same family of languages as .

.

Thus, 21FWK = 21WK.

Corollary 3: All final 1 limited two-way Watson Crick automata accept the same family of languages as the family of languages accepted by arbitrary twoway Watson Crick automata with arbitrary transition rules.

Proof: From Theorem 4 we know 2AWK = 21WK and from Theorem 6 we obtain 21FWK = 21WK. Thus combining both the results we get 21FWK = AWK.

Thus from the above Theorems we can state that 2AWK = 21FWK = 21WK = 2SWK = 2FSWK = 2FWK.

7. Power of Two-Way Non-Deterministic WK Automata

In this section we first show that AWK are subset of 2AWK. Then we further show that this subset relation is proper i.e. 2AWK are more powerful than AWK.

Theorem 7: AWK  2AWK.

2AWK.

The theorem says that non-deterministic Watson Crick automata are subset of two-way non-deterministic Watson Crick automata.

Proof:

Let  be a non-deterministic Watson Crick automaton where

be a non-deterministic Watson Crick automaton where  is a set of alphabet,

is a set of alphabet,  is a set of states,

is a set of states,  is the complementarity relation and

is the complementarity relation and  is the initial state and

is the initial state and  is the set of final states.

is the set of final states.  is the finite number of transition rules of the form

is the finite number of transition rules of the form , where

, where

We introduce a two-way non-deterministic Watson Crick automaton

where

where  is a set of alphabet,

is a set of alphabet,  are the beginning and the end marker respectively, that is, the word w to be recognized is provided as an input to the automaton in the form

are the beginning and the end marker respectively, that is, the word w to be recognized is provided as an input to the automaton in the form

is the complementarity relation and

is the complementarity relation and  is the initial state and qf is a final state.

is the initial state and qf is a final state.  is the finite number of transition rules of the form

is the finite number of transition rules of the form

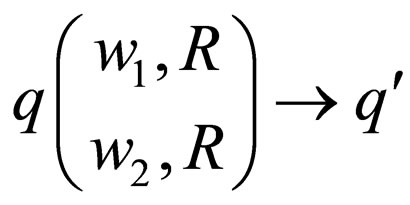

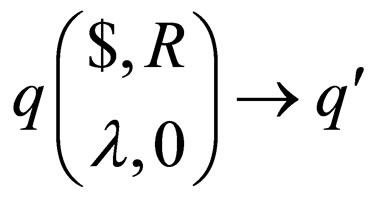

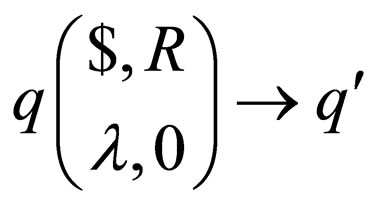

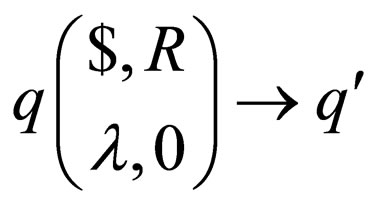

1) For each rule  in

in  introduce

introduce

in

in .

.

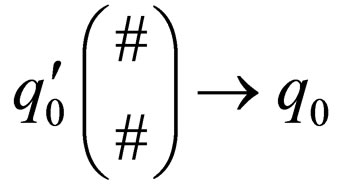

2) .

.

3) For each state  in

in  introduce

introduce

in

in .

.

From the construction of  it is evident that all that will be accepted by

it is evident that all that will be accepted by  will be accepted by

will be accepted by .

.

Theorem 8: One-Way Two headed finite automata are equivalent to AWK

An informal proof of this theorem is in [4].

Example 1

Let  be a 2AWK where

be a 2AWK where  are the beginning and the end marker respectively, that is, the word w to be recognized is provided as an input to the automaton in the form

are the beginning and the end marker respectively, that is, the word w to be recognized is provided as an input to the automaton in the form

is a set of states,

is a set of states,

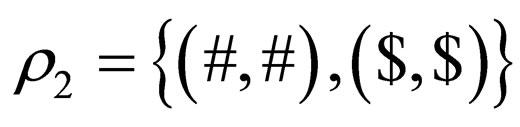

is the identity complementarity relation and

is the identity complementarity relation and  is the initial state and

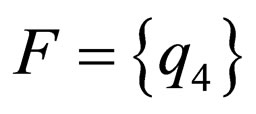

is the initial state and  is the set of final states.

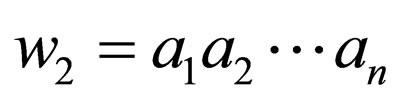

is the set of final states.  is the finite number of transition rules. In this example the mirror language

is the finite number of transition rules. In this example the mirror language  and

and where

where  denotes the reverse of

denotes the reverse of  is accepted using two-way Watson Crick automaton.

is accepted using two-way Watson Crick automaton.

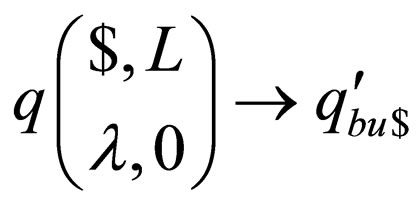

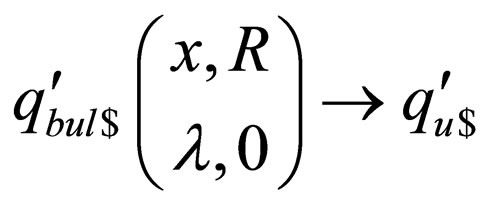

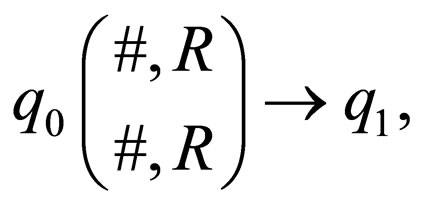

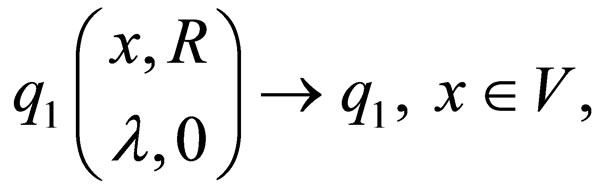

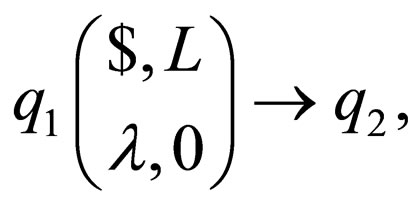

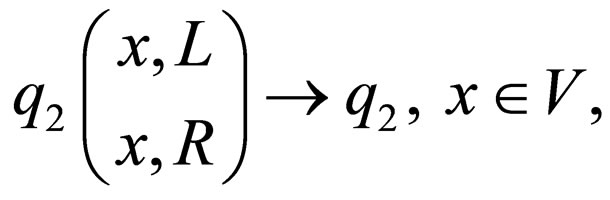

The transition rules of  are as follow

are as follow

.

.

Theorem 9: One-way finite automata with 2 heads cannot accept the mirror language.

The above theorem is stated in [11].

Theorem 10: 2AWK are more powerful than AWK i.e. AWK  2AWK.

2AWK.

Proof. From Theorem 8 we know that AWK is equivalent to 1-way two headed finite automata and from Theorem 9 we know that 1-way two headed finite automata cannot recognize the mirror language. Thus AWK cannot recognize the mirror language. But in Example 1 we have shown that two-way AWK can accept the mirror language and in theorem 7 we have shown that AWK  2AWK i.e. 2AWK accepts all the family of languages which are accepted by AWK. Moreover it also accepts the mirror language which AWK cannot accept. Thus 2AWK accepts at least one language more than AWK. Hence we conclude that the accepting power of two-way AWK is more than AWK. Mathematically AWK

2AWK i.e. 2AWK accepts all the family of languages which are accepted by AWK. Moreover it also accepts the mirror language which AWK cannot accept. Thus 2AWK accepts at least one language more than AWK. Hence we conclude that the accepting power of two-way AWK is more than AWK. Mathematically AWK  2AWK, i.e. the subset relation is proper.

2AWK, i.e. the subset relation is proper.

Theorem 11: Family of languages accepted by WK automata is context sensitive.

A linear bounded Turing machine (LBA) can simulate the actions of two-way Watson Crick automaton. As the language accepted by LBA is context sensitive so the family of languages accepted by two-way Watson Crick automaton is also context sensitive.

8. Characterization of Recursively Enumerable (RE) Languages in Terms of 2AWK Automata

In this section we discuss 2AWK in the light of the RE languages. We show each language in the family of RE is the image of a gsm mapping of a language in 2 AWK.

Theorem 12: TSV ( AWK(ctrl)

( AWK(ctrl)

The proof of this theorem is in [4].

Theorem 13: For each recursively enumerable language L there is a gsm gL such that L = gL (2AWK (ctrl)).

Proof: We have already shown in Theorem 7 AWK  2AWK and it is stated in [4] that TSV Î AWK(ctrl) and from corollary 2 we know that each language in the family of RE is the image of a gsm mapping of a language in TS{0,1}. As TSV Î AWK(ctrl) and AWK Î 2AWK, so we can state, each language in the family of RE is the image of a gsm mapping of a language in 2AWK(ctrl).

2AWK and it is stated in [4] that TSV Î AWK(ctrl) and from corollary 2 we know that each language in the family of RE is the image of a gsm mapping of a language in TS{0,1}. As TSV Î AWK(ctrl) and AWK Î 2AWK, so we can state, each language in the family of RE is the image of a gsm mapping of a language in 2AWK(ctrl).

9. Conclusion

In this paper, we discuss about the power of a variant of non-deterministic Watson Crick automata known as 2AWK. We describe their structure and accepting conditions. We introduce different subclasses of 2AWK similar to AWK and show the equivalence of some of those subclasses. We further establish the fact that 2AWK are more powerful than AWK. Based on the relation between AWK and 2AWK we show that a gsm mapping of 2AWK results in the generation of each language in the family of the recursively enumerable languages.

REFERENCES

- L. C. S. Calude and G. Paun, “Computing with Cells and Atoms: An Introduction to Quantum, DNA and Membrane Computing,” Taylor & Francis Publishers, London, 2001.

- L. M. Adleman, “Molecular Computation of Solutions to Combinatorial Problems,” Science, New Series, Vol. 226, No. 5187, 1994, pp. 1021-1024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.7973651

- R. Freund, G. Paun, G. Rozenberg and A. Saloma, “A, Watson-Crick Finite Automata,” Proceedings of the 3rd DIMACS Workshop on DNA Based Computers, Philadelphia, 1997, pp. 297-328.

- G. Paun, G. Rozenberg and A. Salomaa, “DNA Computing: New Computing Paradigms,” Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1998.

- E. Czeizler, E. Czeizler, L. Kari and K Salomaa, “WatsonCrick Automata: Determinism and State Complexity,” Proceeding of: 10th International Workshop on Descriptional Complexity of Formal Systems, DCFS, 16-18 July 2008, pp. 121-133.

- E. Czeizler, E. Czeizler, L. Kari and K. Salomaa, “On the Descriptional Complexity of Watson-Crick Automata,” Theoretical Computer Science, Vol. 410, No. 35, 2009, pp. 3250-3260. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tcs.2009.05.001

- E. Czeizler, E. Czeizler,” Parallel Communicating Watson-Crick Automata Systems,” In: Z. Fulop Z. Esik (Ed.), Proceedings of 11th International Conference, AFL 2005, 2005, pp. 83-96.

- E. Czeizler, “On the Power of Parallel Communicating Watson-Crick Automata Systems,” Theoretical Computer Science, Vol. 358, No. 1, 2006, pp. 142-147.

- E. Czeizler, “A Short Survey on Watson-Crick Automata,” Bulletin of the EATCS, Vol. 88, 2006, pp. 104-119.

- D. Kuske and P. Weigel, “The Role of the Complementarity Relation in Watson-Crick Automata and Sticker Systems,” Developments in Language Theory, Vol. 3340, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer, Berlin, 2004, pp. 272-283.

- M. Holzer, M. Kutrib and A. Malcher, “Multi-Head Finite Automata: Characterizations, Concepts and Open Problems,” Proceedings International Workshop on the Complexity of Simple Programs, Cork, 6-7 December 2008, pp. 93-107.

Abbreviations

AWK: non-deterministic Watson-Crick automata.

NWK: stateless non-deterministic Watson-Crick automata.

FWK: all final non-deterministic Watson-Crick automata.

SWK: simple non-deterministic Watson-Crick automata.

1WK: 1-limited non-deterministic Watson-Crick automata.

2AWK: two way non-deterministic Watson-Crick automata.

2NWK: two way stateless non-deterministic WatsonCrick automata.

2FWK: two way all final non-deterministic WatsonCrick automata.

2SWK: two way simple non-deterministic WatsonCrick automata.

21WK: two way 1-limited non-deterministic WatsonCrick automata.

TSV: twin-shuffle language.

RE: recursive enumerable.

gsm: generalized sequential machine.