Advances in Bioscience and Biotechnology

Vol.4 No.2A(2013), Article ID:28442,12 pages DOI:10.4236/abb.2013.42A039

Synergistic effect between cryptotanshinone and antibiotics in oral pathogenic bacteria

![]()

1Department of Natural Products Research, Institute of Jinan Red Ginseng, Jinan, South Korea

2Department of Nursing, Dong-eui University, Busan, South Korea

3Department of Oral Microbiology and Institute of Oral Bioscience, Chonbuk National University, Jeonju, South Korea

Email: *kyleecnu@chonbuk.ac.kr

Received 29 November 2012; revised 30 December 2012; accepted 8 January 2013

Keywords: Cryptotanshinone; Antibacterial Activity; Oral Bacteria; Checker Board Method; Time-Kill Method; Synergistic Effect

ABSTRACT

Cryptotanshinone (CT), a major tanshinone of medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, demonstrated effective in vitro antibacterial activity against all oral bacteria tested in this experiment. The antibacterial activities of CT against oral bacteria were assessed using the checkerboard and time-kill methods to evaluate the synergistic effects of treatment with ampicillin or gentamicin. The CT was determined against oral pathogenic bacteria with MIC and MBC values ranging from 0.5 to 16 and 1 to 64 μg/mL; for ampicillin from 0.0313 to 16 and 0.125 to 32 μg/mL; for gentamicin from 2 to 256 and 4 to 512 μg/mL respectively. The range of MIC50 and MIC90 were 0.0625 - 8 μg/mL and 1 - 64 μg/mL, respectively. The combination effects of CT with antibiotics were synergistic (FIC index < 0.5) against tested oral bacteria except additive, Streptococcus sobrinus, S. criceti, and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (FIC index < 0.75 - 1.0). The MBCs were shown reducing ≥4 - 8-fold, indicating a synergistic effect as defined by a FBCI of ≤0.5. Furthermore, a time-kill study showed that the growth of the tested bacteria was completely attenuated after 3 - 6 h of treatment with the 1/2 MIC of CT, regardless of whether it was administered alone or with ampicillin or gentamicin. The results suggest that CT could be employed as a natural antibacterial agent against cariogenic and periodontopathogenic bacteria.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dental caries and periodontal disease are prevalent worldwide. Bacteria existing in the dental plaque or biofilm play an important role in the development of both dental caries and periodontal disease [1,2]. Of the more than 750 species of bacteria that inhabit the oral cavity, a number are implicated in oral diseases [3]. The development of dental caries involves acidogenic and aciduric gram-positive bacteria (mutans streptococci, lactobacilli and actinomycetes) [4]. Periodontal diseases have been linked to anaerobic gram-negative bacteria (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Actinobacillus, Prevotella, and Fusobacterium) [5]. Antibiotics such as ampicillin, chlorhexidine, erythromycin, penicillin, tetracycline and vancomycin have been very effective in preventing dental caries [6]. Of the selected putative periodontal species, strains of Prevotella intermedia, Fusobacterium nucleatum and to the first time, Tannerella forsythia, were β-lactamase positive, with P. intermedia being the most frequently detected enzyme positive species [7]. Subgingival isolates of P. gingivalis, P. intermedia and F. nucleatum in a group of subjects increase in the MIC values of tetracycline [8]. This clinical observation led to studies that established metronidazole as an important antibiotic for anaerobic infection. Since then, this compound has also played an important role in treating anaerobe related infection in the oral cavity, abdomen, and female genital tract, among others [9]. Oral bacteria have been reported to show increased resistance towards common antibiotics such as penicillin, cephalosporin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and metronidazole which have been used therapeutically for the treatment of oral infection [10,11]. The increase in resistance and adverse effects has lead researchers to explore novel anti-infective herbal compounds which could be used for effective treatment of oral diseases [12,13].

Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Danshen) is an herb commonly used in traditional oriental medicine the treatment of several pathologies including cardiovascular diseases, hepatitis, menstrual disorders, diabetes, and chronic renal failure [14-17]. Cryptotanshinone (CT) is one of the principal active constituents in Danshen extract and has several pharmacological effects, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, anti-bacterial, anti-angiogenic, antimutagenic, anti-platelet aggregation, anti-human hepatocellular carcinoma effects, and anti-cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) functions [18-23]. CT exhibits antimicrobial activity against a broad range of Gram-positive, including S. aureus, and Gram-negative bacteria as well as other microorganisms [24]. Although CT exhibited fairly high levels of activity against S. aureus, there have been no reports related to the inhibitory mechanisms of CT against S. aureus. For over 100 years, chemical compounds isolated from medicinal plants have served as the models for many clinically proven drugs and are now being reassessed as antimicrobial agents [25]. Plant-derived antibacterials are always a source of novel therapeutics.

We have investigated the antibacterial activity of cryptotanshinone, a major bioactive constituent isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Danshen) against oral pathogens when used alone and in combination with antibiotics.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Bacterial Strains

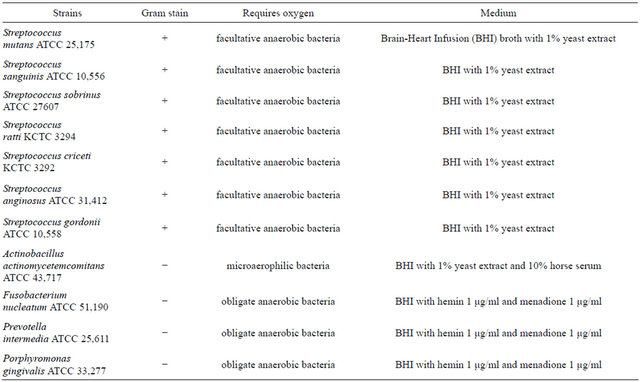

The cariogenic bacterial strains used in this study were: Streptococcus mutans ATCC 25,175, Streptococcus sanguinis ATCC 10,556, Streptococcus sobrinus ATCC 27,607, Streptococcus ratti KCTC (Korean collection for type cultures) 3294, Streptococcus criceti KCTC 3292Streptococcus anginosus ATCC 31,412, and Streptococcus gordonii ATCC 10,558 and the periodontopathogenic bacterial strains used: Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 43,717, Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC 10,953, Prevotella intermedia ATCC 25,611, and Porphylomonas gingivalis ATCC 33,277. Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) broth supplemented with 1% yeast extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) was used for cariogenic bacterial strains. For periodontopathogenic bacterial strains, BHI broth containing hemin 1 μg/ml (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and menadione 1 μg/ml (Sigma) was used. (Table 1)

2.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations/ Minimum Bactericidal Concentrations Assay

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined for CT by the broth dilution method [26], and were carried out in triplicate. The antibacterial activities were examined after incubation at 37˚C for 18 h (facultative anaerobic bacteria), for 24 h (microaerophilic bacteria), and for 1 - 2 days (obligate anaerobic bacteria) under anaerobic conditions. MICs were determined as the lowest concentration of test samples that resulted in a complete inhibition of visible growth in the broth. MIC50s and MIC90s, defined as MICs at which, 50 and 90%, respectively of oral bacteria were inhibited, were

Table 1. List of strains and culture media used for antimicrobial experiment.

determined. Following anaerobic incubation of MICs plates, the minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were determined on the basis of the lowest concentration of CT that kills 99.9% of the test bacteria by plating out onto each appropriate agar plate. Ampicillin (Sigma) and gentamicin (Sigma) were used as standard antibiotics in order to compare the sensitivity of CT against test bacteria.

2.3. Checker-Board Dilution Assay

The antibacterial effects of a combination of CT, which exhibited the highest antimicrobial activity, and antibiotics were assessed by the checkerboard test as previously described [26,27]. The antimicrobial combinations assayed included CT with ampicillin or gentamicin. Serial dilutions of two different antimicrobial agents were mixed in cation-supplemented Mueller-Hinton broth. After 24 h of incubation at 37˚C, the MIC was determined to be the minimal concentration at which there was no visible growth. The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) is the sum of the FICs of each of the drugs, which in turn is defined as the MIC of each drug when it is used in combination divided by the MIC of the drug when it is used alone. The interaction was defined as synergistic if the FIC index was less than or equal to 0.5, additive if the FIC index was greater than 0.5 and less than or equal 1.0, indifferent if the FIC index was greater than 1.0 and less than or equal to 2.0, and antagonistic if the FIC index was greater than 2.0 [26,27].

2.4. Time-Kill Assay

A time-kill kinetic study against oral bacteria was performed using the broth macrodilution method [26]. The following samples were incubated in BHI medium at 37˚C under anaerobic conditions: oral bacteria 5 - 7 × 106 CFU/mL + CT (MIC); oral bacteria 5 - 7 × 106 CFU/mL + CT (1/2 MIC) + Amp (1/2 MIC); and oral bacteria 5 - 7 × 106 CFU/mL + CT (1/2 MIC) + Gen (1/2 MIC). At 0, 30 min and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 12, and 24 h, samples were taken and viable counts were determined as follows. Colony counts were performed in duplicate, and means were taken. The solid media used for colony counts were Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) agar for streptococci and Brain-Heart Infusion agar containing hemin and menadione for P. intermedia and P. gingivalis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All the data are expressed as a mean ± standard error (SE) of triplicate experiments.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Antibacterial Activity of CT

In this study, CT was evaluated for their antimicrobial activities against eleven common bacterial species present in the oral cavity. The results of the antimicrobial activity showed that CT exhibited antimicrobial activities against cariogenic bacteria (MICs, 0.5 to 4 µg/mL; MBCs, 1 to 16 µg/mL), against periodontopathogenic bacteria (MICs, 8 to 32 µg/mL; MBCs, 16 to 64 µg/mL) and for ampicillin, either 0.125/0.5 or 64/64 μg/mL; for gentamicin, either 2/4 or 256/512 μg/mL on tested all bacteria (Table 2 and Figures 1-4). The MIC50 and MIC90 determinations for cariogenic bacteria confirmed higher antibacterial activity of CT than periodontopathogenic

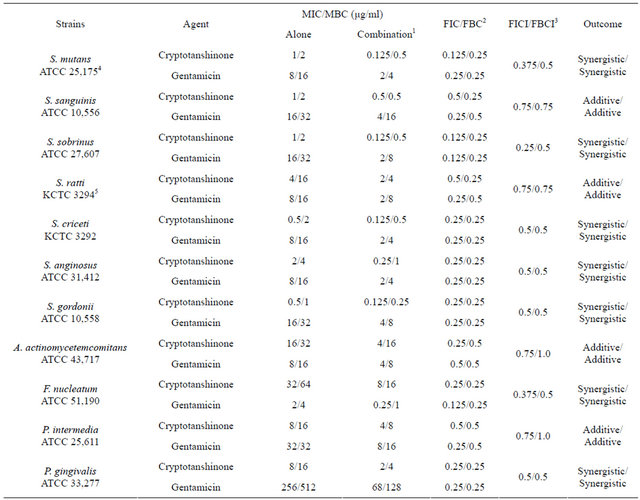

Table 2. Antibacterial activity of cryptotanshinone and antibiotics in oral bacteria.

1American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), 2Korean collection for type cultures (KCTC).

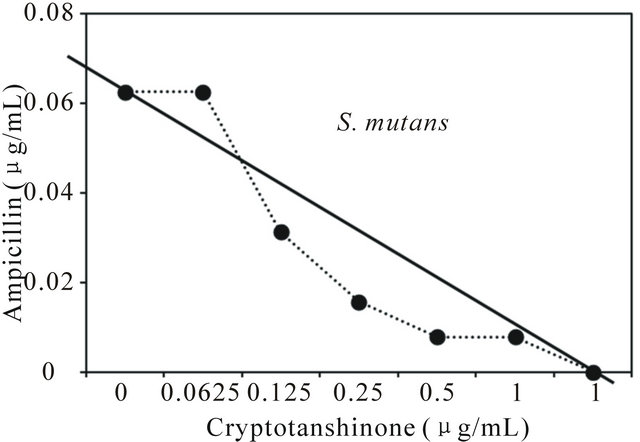

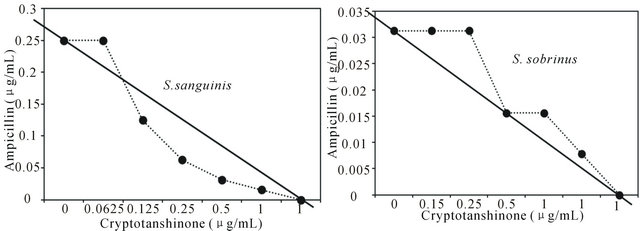

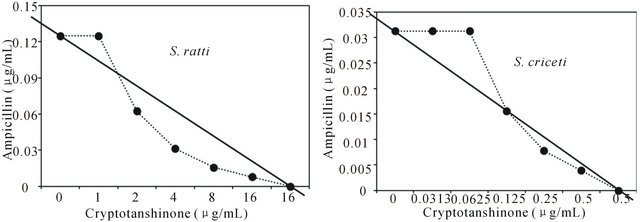

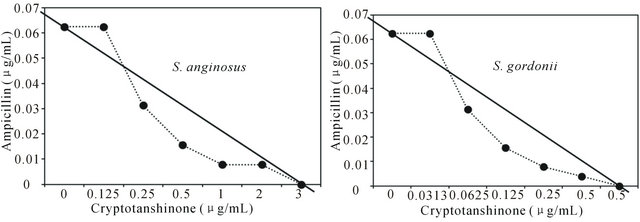

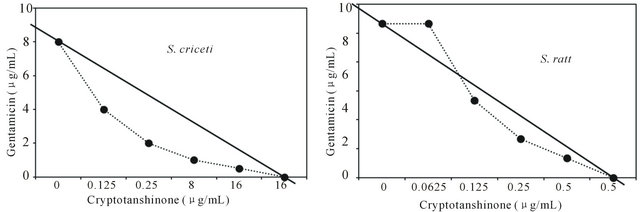

Figure 1. Isobologram curve revealing the synergistic effect of cryptotanshinone (CT) with ampicillin against cariogenic bacteria, S. mutans, S. sanguinis, S. sobrinus, S. anginosus, S. criceti, and S. ratti.

bacteria. The range of MIC50 and MIC90 were from 0.125 to 8 μg/mL and 0.5 to 32 μg/mL, respectively. The CT showed the strongest antimicrobial activity against cariogenic bacteria, S. criceti and S. gordonii (MIC/MBC, 0.5/1 - 2 μg/mL) and the range of MIC50 and MIC90 were 0.125 μg/mL and 0.5 μg/mL.

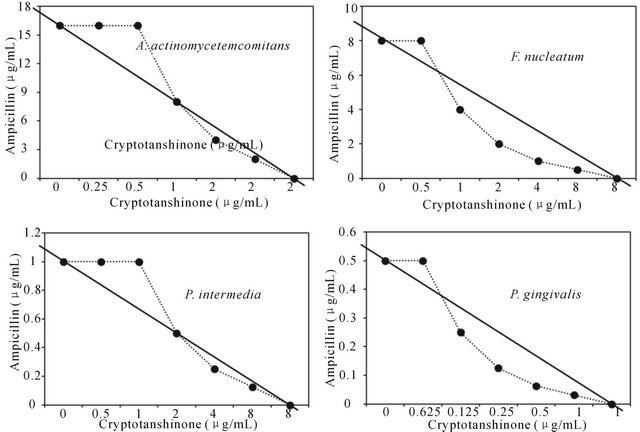

Figure 2. Isobologram curve revealing the synergistic effect of cryptotanshinone (CT) with ampicillin against periodontopathogenic bacteria, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, and P. gingivalis.

3.2. Synergistic Effect of CT with Antibiotics

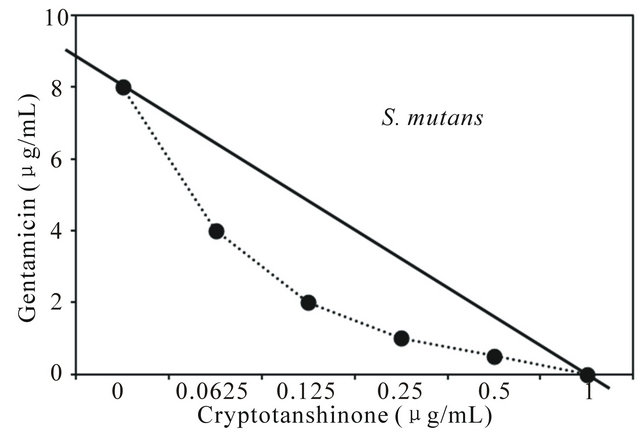

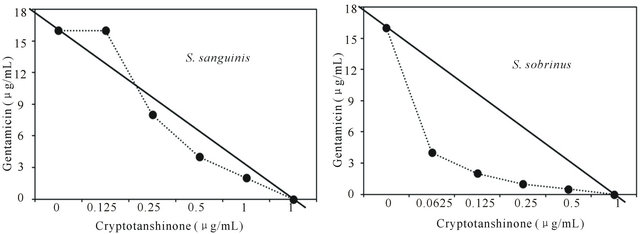

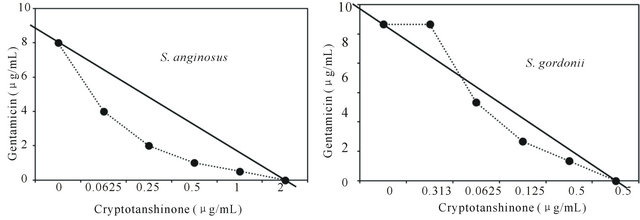

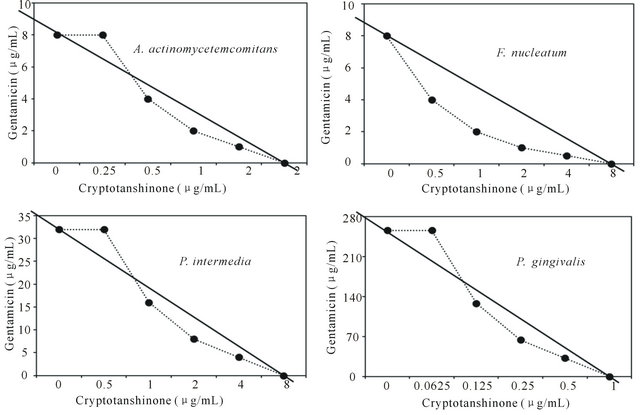

Activity of antibiotics plus the plant extract was determined using the checkerboard technique [26,28]. The synergistic effect of CT with ampicillin or gentamicin in oral bacteria was presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. In combination of CT with ampicillin, the MIC ranges were observed in cariogenic bacteria at 0.125 μg/mL to 1 μg/mL and reduced ≥4-fold, producing a synergistic effect as defined by FICI ≤ 0.5, except additive effect in S. sobrinus and S. criceti by FICI ≤ 0.75 - 1.0. The MBC ranges (0.5 μg/mL to 4 μg/mL) of CT with ampicillin were reduced ≥4-fold in S. ratti, S. anginosus, and S. gordonii (Table 3). In periodontopathogenic bacteria, the MIC values of CT with ampicillin was also observed by ≥4-fold, producing a synergistic effect as defined by FICI ≤ 0.5, except additive effect in A. actinomycetemcomitans by FICI ≤ 0.75 and the MBC values (4 μg/mL to 16 μg/mL) of CT with ampicillin were reduced ≥4-fold in F. nucleatum. The combination of CT with gentamicin was observed resulted in the decrease ≥4-fold in MIC for most of tested bacteria, except S. sanguinis, S. ratti, A. actinomycetemcomitans, and P. intermedia by FICI ≤ 0.5 and in MBC for S. mutans, S. criceti, S. anginosus, and P. gingivalis by FBCI ≤ 0.5 but additive for S. sanguinis, S. ratti, A. actinomycetemcomitans, and P. intermedia by FIBI ≤ 0.75 (Table 4).

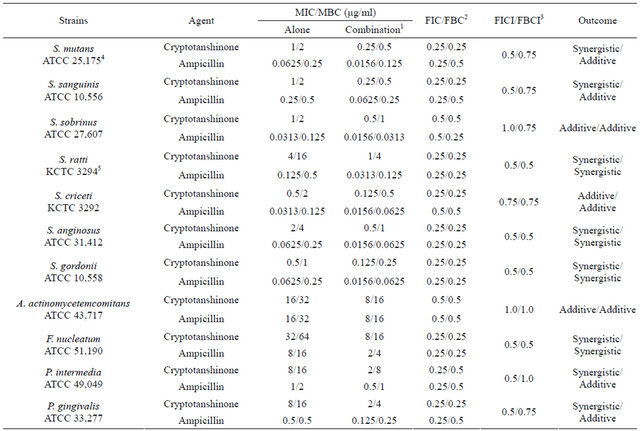

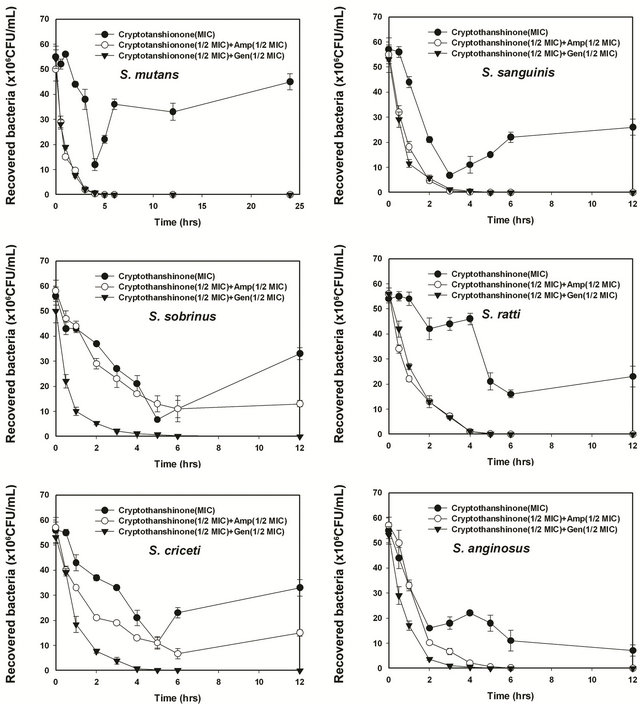

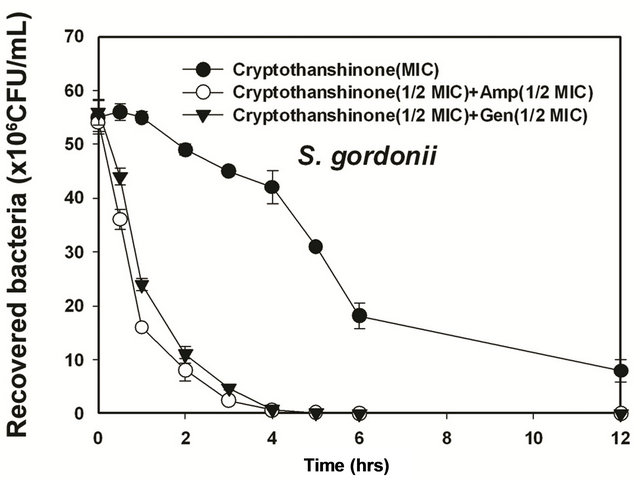

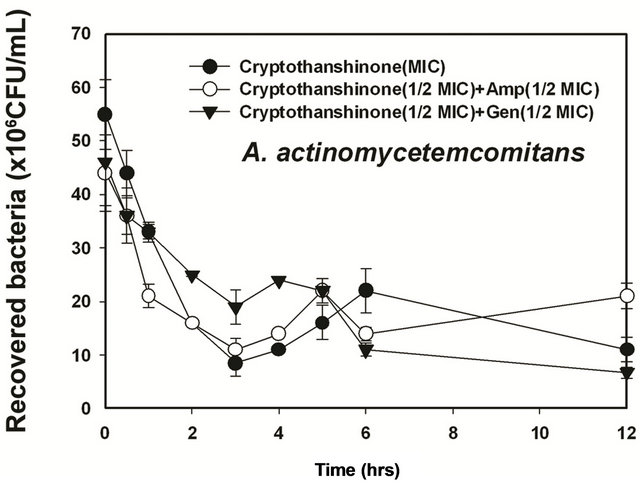

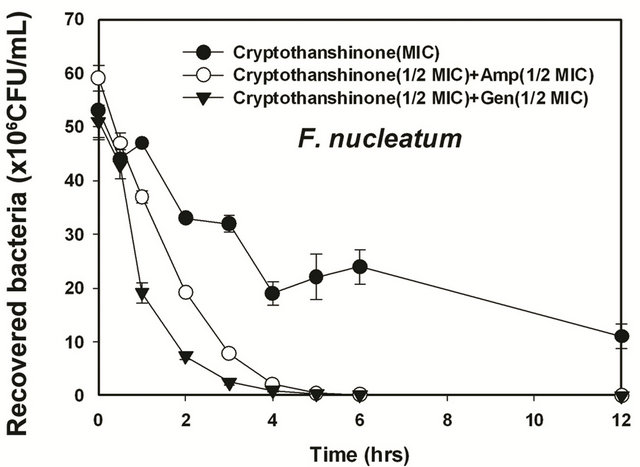

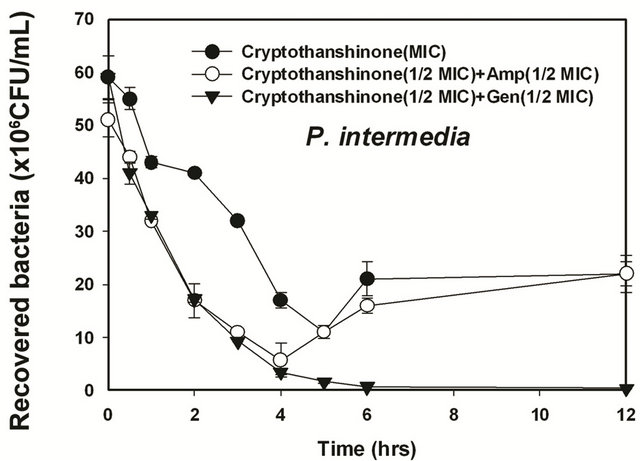

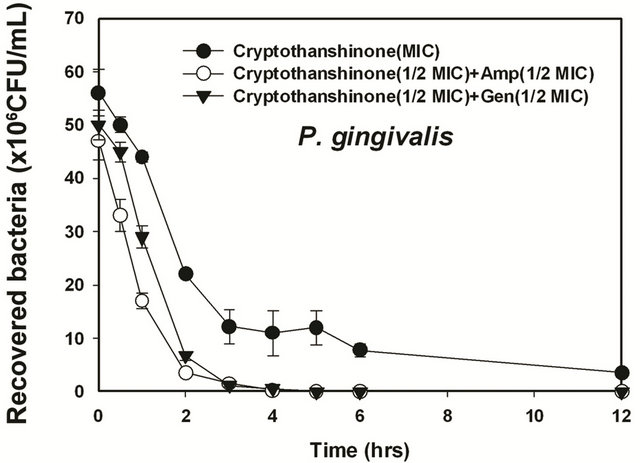

3.3. Time-Kill Curves

The synergistic effect of CT with ampicillin or gentamicin against oral bacteria was confirmed by time-kill curve experiments. The cultures of all bacteria, with a cell density of 105 CFU/ml, were exposed to MIC or 1/2 MIC of CT alone and with 1/2 MIC of ampicillin or gentamicin. We observed that CT with antibiotics resulted rate of killing increasing in CFU/ml at time-dependent manner (Figures 1 and 2). In order to assess the effects of combinations of CT and antibiotics, the MIC50 values of the antibiotics were determined as these provide the reference point for defining the interactions.

4. DISCUSSION

With the increase in the incidence of resistance to antibiotics, alternative natural products of plants could be of interest. Some plant extracts and phytochemicals are known to have antimicrobial properties, which could be of great importance in the therapeutic treatments [25-27, 29]. Many plants have been evaluated not only for direct antimicrobial activity but also as resistance-modifying agents [30,31]. In this study, the antibacterial activities and synergistic effects of CT or with antibiotics were exhibited in oral bacteria. The results of the antimicrobial activity showed that CT exhibited antimicrobial activities against cariogenic bacteria at 0.5 to 4 µg/mL of MICs

Figure 3. Isobologram curve revealing the synergistic effect of cryptotanshinone (CT) with gentamicin against cariogenic bacteria, S. mutans, S. sanguinis, S. sobrinus, S. anginosus, S. criceti, and S. ratti.

and 1 to 16 µg/mL of MBCs against periodontopathogenic bacteria at 8 to 32 µg/mL of MICs and 16 to 64 µg/mL of MBCs and the MIC50 and MIC90 determinations for cariogenic bacteria confirmed higher antibacterial activity of CT than periodontopathogenic bacteria. The CT showed the strongest antimicrobial activity against cariogenic bacteria, S. criceti and S. gordonii (MIC/MBC, 0.5/1 - 2 μg/mL) and the range of MIC50

Figure 4. Isobologram curve revealing the synergistic effect of cryptotanshinone (CT) with gentamicin against periodontopathogenic bacteria, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, and P. gingivalis.

Table 3. Synergistic effects of cryptotanshinone with ampicillin against oral bacteria.

1The MIC and MBC of the cryptotanshinone with ampicillin. 2The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC)/The fractional bactericidal concentration (FBC). 3The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI)/The fractional bactericidal concentration index (FBCI). 4American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). 5Korean collection for type cultures (KCTC).

Table 4. Synergistic effects of cryptotanshinone with gentamicin against oral bacteria.

1The MIC and MBC of the cryptotanshinone with gentamicin. 2The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC)/The fractional bactericidal concentration (FBC). 3The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI)/The fractional bactericidal concentration index (FBCI). 4American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). 5Korean collection for type cultures (KCTC).

and MIC90 were 0.125 μg/mL and 0.5 μg/mL.

These diterpene quinines are found exclusively in the genus Salvia and show antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-platelet aggregation effects [32-34]. The cryptotanshinone and dihydrotanshinone I exhibit strong antimicrobial activity and MIC values of these on the spore germination of M. oryzae were 6.25 μg/mL and 3.13 μg/mL, respectively and on A. tumefaciens, E. coli, P. lachrymans, R. solanacearum, X. vesicatoria, B. subtilis, S. aureus, and S. haemolyticus ranged from 6.25 μg/mL to 100 μg/mL, and the median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values from 3.66 μg/mL to 57.38 μg/mL. Combinations of some herbal materials and different antibiotics might affect the inhibitory effect of these antibiotics [26,27,29]. In combination of CT with ampicillin, the MIC ranges were observed in cariogenic bacteria at 0.125 μg/mL to 1 μg/mL and reduced ≥4-fold, producing a synergistic effect as defined by FICI ≤ 0.5 and in periodontopathogenic bacteria. The MIC values of CT with ampicillin was also observed by ≥ 4-fold, producing a synergistic effect as defined by FICI ≤ 0.5, except additive effect in A. actinomycetemcomitans by FICI ≤ 0.75 and the MBC values, 4 μg/mL to 16 μg/mL of CT with ampicillin were reduced ≥4-fold in F. nucleatum. The combination of CT with gentamicin was observed resulted in the decrease ≥4-fold in MIC and MBC for most of tested bacteria by FICI ≤ 0.5 but additive for S. sanguinis, S. ratti, A. actinomycetemcomitans, and P. intermedia by FIBI ≤ 0.75.

Such combinations would be synergistic if there is a decrease in the MIC of each agent of four-fold; partially synergistic if there is a MIC decrease for one drug of four-fold and a decrease of two-fold of the other agent; additive if there is a two-fold reduction in the MIC of both agents; indifference is all interactions not meeting the criteria listed above and not being antagonistic

Figure 5. Time-kill curves of MIC or MIC50 of cryptotanshinon (CT) alone and its combination with MIC50 of Amp or Gen against S. mutans, S. sanguinis, S. sobrinus, S. anginosus, S. criceti, and S. ratti. Bacteria were incubated with MIC of cryptotanshinon (●), 1/2 MIC of cryptotanshinon + 1/2 MIC of Amp (○), and 1/2 MIC of cryptotanshinon + 1/2 MIC of Gen (▼) over time. CFU, colony-forming units.

[27,35]. Antagonistic response refers to where a MIC increase of four-fold for each drug would be observed in combination [36]. The synergistic effect of CT with ampicillin or gentamicin against oral bacteria was confirmed. 1 - 3 hours of treatment with 1/2 MIC of CT with 1/2 MIC of antibiotics resulted from an increase of the rate of killing in units of CFU/mL to a greater degree than was observed with alone. Phenolic acids with a variety of bioactivities, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-thrombosis, anti-hypertension, antivirus and antitumor properties, are widely distributed in the plant kingdom [37-39]. CT demonstrates effective in vitro antibacterial activity against all 21 S. aureus strains [24]. Affymetrix GeneChips are utilized to determine the global transcriptional response of S. aureus ATCC 25,923 to treatment with subinhibitory concentrations of CT [24]. Those results were found similar to our results which were evaluated as strong antibacterial activity against gram-positive bacteria, cariogenic bacteria.

In conclusion, the results suggest that combinations of CT with antibiotics should be investigated further for possible use in antibacterial products. Particularly, these may be useful in the future for the treatment of cariogenic bacteria.

Figure 6. Time-kill curves of MIC of cryptotanshinon (CT) alone and its combination with MIC of Amp or Gen against S. gordonii, A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, and P. gingivalis. Bacteria were incubated with MIC of cryptotanshinon (●), 1/2 MIC of cryptotanshinon + 1/2 MIC of Amp (○), and 1/2 MIC of cryptotanshinon + 1/2 MIC of Gen (▼) over time. CFU, colony-forming units.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was supported in part by research funds of National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-20120008470). There is no conflict of interest related to this research.

REFERENCES

- Seneviratne, C.J., Zhang, C.F. and Samaranayake, L.P. (2011) Dental plaque biofilm in oral health and disease. The Chinese Journal of Dental Research: The Official Journal of the Scientific Section of the Chinese Stomatological Association (CSA), 14, 87-94.

- Sambunjak, D., Nickerson, J.W., Poklepovic, T., Johnson, T.M., Imai, P., Tugwell, P. and Worthington, H.V. (2011) Flossing for the management of periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7, CD008829.

- Zarco, M.F., Vess, T.J. and Ginsburg, G.S. (2012) The oral microbiome in health and disease and the potential impact on personalized dental medicine. Oral Diseases, 18, 109-120. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01851.x

- Takahashi, N. and Nyvad, B. (2011) The role of bacteria in the caries process: Ecological perspectives. Journal of Dental Research, 90, 294-303. doi:10.1177/0022034510379602

- Africa, C.W. (2011) Oral colonization of Gram-negative anaerobies as a risk factor for preterm delivery. Virulence, 2, 498-508. doi:10.4161/viru.2.6.17719

- Levi, M.E. and Eusterman, V.D. (2011) Oral infections and antibiotic therapy. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 44, 57-78. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2010.10.003

- Van Winkelhoff, A.J., Winkel, E.G., Barendregt, D., Dellemijn-Kippuw, N., Stijne, A. and Van Der Velder, U. (1997) Beta-Lactamase producing bacteria in adult periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 24, 538- 543. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.1997.tb00226.x

- Abu-Fanas, S.H., Drucker, D.B. and Hull, P.S. (1991) Amoxicillin with clavulanic acid and tetracycline in periodontal therapy. Journal of Dentistry, 19, 97-99. doi:10.1016/0300-5712(91)90098-J

- Falagas, M.E. and Gorbach, S.L. (1995) Clindamycin and metronidazole. The Medical clinics of North America, 79, 845-867.

- Rams, T.E., Degener, J.E. and van Winkelhoff, A.J. (2012) Prevalence of beta-lactamase-producing bacteria in human periodontitis. Journal of Periodontal Research, 23. doi:10.1111/jre.12031

- Bedenić, B., Budimir, A., Gverić, A., Plecko, V., Vranes, J., Bubonja-Sonje, M. and Kalenić, S. (2012) Comparative urinary bactericidal activity of oral antibiotics against gram-positive pathogens. Liječničkog Vjesnika, 134, 148- 155.

- Feldman, M., Santos, J. and Grenier, D. (2011) Comparative evaluation of two structurally related flavonoids, isoliquiritigenin and liquiritigenin, for their oral infection therapeutic potential. Journal of Natural Products, 74, 1862-1867. doi:10.1021/np200174h

- Greenberg, M., Dodds, M. and Tian, M. (2008) Naturally occurring phenolic antibacterial compounds show effectiveness against oral bacteria by a quantitative structureactivity relationship study. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 56, 11151-1156. doi:10.1021/jf8020859

- Zhou, R., He, L.F., Li, Y.J., Shen, Y., Chao, R.B. and Du, J.R. (2012) Cardioprotective effect of water and ethanol extract of Salvia miltiorrhiza in an experimental model of myocardial infarction. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 139, 440-446. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.030

- Hu, X., Zhou, Y.J., Xie, Q.R., Sun, X.C. and Xiao, Y. (2006) Clinical observation of sophocarpidine combined with Salviae miltiorrhizae injection in treating chronic hepatitis B. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao, 4, 648-650.

- Qian, Q., Qian, S., Fan, P., Huo, D. and Wang, S. (2012) Effect of Salvia miltiorrhiza hydrophilic extract on antioxidant enzymes in diabetic patients with chronic heart disease: A randomized controlled trial. Phytotherapy Research, 26, 60-66. doi:10.1002/ptr.3513

- Ahn, Y.M., Kim, S.K., Lee, S.H., Ahn, S.Y., Kang, S.W., Chung, J.H., Kim, S.D. and Lee, B.C. (2010) Renoprotective effect of Tanshione IIA, an active component of Salvia mitiorrhiza, on rats with chronic kidney disease. Phytotherapy Research, 24, 1886-1892. doi:10.1002/ptr.3347

- Chen, W., Liu, L., Luo, Y., Odaka, Y., Awate, S., Zhou, H., Shen, T., Zheng, S., Lu, Y. and Huang, S. (2012) Cryptotanshinone activates p38/JNK and inhibits Erk1/2 leading to caspase-independent cell death in tumor cells. Cancer Prevention Research (Phila), 5, 778-787. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0551

- Li, X., Lian, L.H., Bai, T., Wu, Y.L., Wan, Y., Xie, W.X., Jin, X. and Nan, J.X. (2011) Cryptotanshinone inhibits LPS-induced proinflammatory mediators via TLR4 and TAK1 signaling pathway. International Immunopharmacology, 11, 1871-1876. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2011.07.018

- Lee, D.S., Lee, S.H., Noh, J.G. and Hong, S.D. (1999) Antibacterial activities of cryptotanshinone and dihydrotanshinone I from a medicinal herb, Salvia miltiorrhiza bunge. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry, 63, 2236-2239. doi:10.1271/bbb.63.2236

- Hur, J.M., Shim, J.S., Jung, H.J. and Kwon, H.J. (2005) Cryptotanshinone but not tanshinone IIA inhibits angiogenesis in vitro. Experimental and Molecular Medicine, 37, 133-137. doi:10.1038/emm.2005.18

- Sato, M., Sato, T., Ose, Y., Nagase, H., Kito, H. and Sakai Y. (1992) Modulating effect of tanshinones on mutagenic activity of Trp-P-1 and benzo[a]pyrene in Salmonella typhimurium. Mutation Research, 265, 149-154. doi:10.1016/0027-5107(92)90043-2

- Chen, T.H., Hsu, Y.T., Chen, C.H., Kao, S.H. and Lee, H.M. (2007) Tanshinone IIA from Salvia miltiorrhiza induces heme oxygenase-1 expression and inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide expression in RAW 264.7 cells. Mitochondrion, 7, 101-105. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2006.11.018

- Feng, H., Xiang, H., Zhang, J., Liu, G., Guo, N., Wang, X., Wu, X., Deng, X. and Yu, L. (2009) Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the response of Staphylococcus aureus to cryptotanshinone. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology, 2009, 617509. doi:10.1155/2009/617509

- Mahady, G.B. (2005) Medicinal plants for the prevention and treatment of bacterial infections. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 11, 2405-24027. doi:10.2174/1381612054367481

- Cha, J.D., Jeong, M.R., Jeong, S.I. and Lee, K.Y. (2007) Antibacterial activity of sophoraflavanone G isolated from the roots of Sophora flavescens. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 17, 858-864.

- Chatterjee, S.K., Bhattacharjee, I. and Chandra, G. (2009) In vitro synergistic effect of doxycycline & ofloxacin in combination with ethanolic leaf extract of Vangueria spinosa against four pathogenic bacteria. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 130, 475-478.

- Garvey, M.I., Rahman, M.M., Gibbons, S. and Piddock, L.J. (2011) Medicinal plant extracts with efflux inhibitory activity against Gram-negative bacteria. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 37, 145-151. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.10.027

- Radhika, L.G., Meena, C.V., Peter, S., Rajesh, K.S. and Rosamma, M.P. (2011) Phytochemical and antimicrobial study of Oraxylum indicum. Ancient Science of Life, 30, 114-120.

- Konaté, K., Hilou, A., Mavoungou, J.F., Lepengué, A.N., Souza, A., Barro, N., Datté, J.Y., M’batchi, B. and Nacoulma O.G. (2012) Antimicrobial activity of polyphenol-rich fractions from Sida alba L. (Malvaceae) against cotrimoxazol-resistant bacteria strains. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials, 24, 11-15.

- Lee, J.W., Ji, W.J., Lee, S.O. and Lee, I.S. (2007) Effect of Saliva miltiorrhiza bunge on antimicrobial activity and resistant gene regulation against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Journal of Microbiology, 45, 350-357.

- Garcia, L.G., Lemaire, S., Kahl, B.C., Becker, K., Proctor, R.A., Denis, O., Tulkens, P.M. and Van Bambeke, F. (2012) Pharmacodynamic evaluation of the activity of antibiotics against hemin and menadione-dependent smallcolony variants of Staphylococcus aureus in models of extracellular (borth) and intracellular (THP-1 monocytes) infections. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 56, 3700-3711. doi:10.1128/AAC.00285-12

- Eldeen, I.M., Van Heerden, F.R. and Van Staden, J. (2010) In vitro biological activities of niloticane, a new bioactive cassane diterpene from the bark of Acacia nilotica subsp. kraussiana. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 128, 555-560. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.057

- Kobayashi, K., Nishiumi, S., Nishida, M., Hirai, M., Azuma, T., Yoshida, H., Mizushina, Y. and Yoshida, M. (2011) Effects of quinine derivatives, such as 1,4-naphthoquinone, on DNA polymerase inhibition and anti-inflammatory action. Medicinal Chemistry, 7, 37-44. doi:10.2174/157340611794072742

- Muroi, H. and Kubo, I. (1996) Antibacterial activity of anacardic acid and totarol, alone and in combination with methicillin, against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 80, 387- 394. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03233.x

- Sader, H.S., Streit, J.M., Fritsche, T.R. and Jones, R.N. (2004) Antimicrobial activity of Daptomycin against multidrug-resistant gram-positive strains collected worldwide. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 50, 201- 204. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.07.002

- Jiang, R.W., Lau, K.M., Hon, P.M., Mak, T.C., Woo, K.S. and Fung, K.P. (2005) Chemistry and biological activities of caffeic acid derivatives from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 12, 237-246. doi:10.2174/0929867053363397

- Wang, J., Lou, J., Luo, C., Zhou, L., Wang, M. and Wang, L. (2012) Phenolic compounds from Halimodendron halodendron (Pall.) Voss and their antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 13, 11349-11364. doi:10.3390/ijms130911349

- Hsu, S., Yu, F.X., Huang, Q., Lewis, J., Singh, B., Dickinson, D., Borke, J., Sharawy, M., Wataha, J., Yamamoto, T., Osaki, T. and Schuster, G. (2003) A mechanism-based in vitro anticancer drug screening approach for phenolic phytochemicals. Assay and Drug Development Technologies, 1, 611-618. doi:10.1089/154065803770380968

NOTES

*Corresponding author.