Creative Education

Vol.10 No.01(2019), Article ID:89910,19 pages

10.4236/ce.2019.101005

The Online World Languages Anxiety Scale (OWLAS)

Barry Chametzky1,2

1American College of Education, Indianapolis, USA

2City University of Seattle, Seattle, USA

Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: December 17, 2018; Accepted: January 12, 2019; Published: January 15, 2019

ABSTRACT

Sadly, anxiety and stress exist all around us. While anxiety has previously been studied in traditional foreign language environments, no information exists about anxiety in an online foreign language environment. Without having a detailed understanding of potential problems in an online environment, educators, administrators, and course designers would not be able to help struggling, suffering students. Thus, the purpose of this seven-participant pilot study was to develop a more refined understanding of foreign language anxiety in the online learning environment. In some respects, the results of this study confirm what foreign language educators already know: students prefer writing rather than speaking, interacting with the instructor rather than with peers, and keeping up with the work is sometimes a challenge. Additionally, if students don’t know basic grammatical elements in their native language, there may be issues in the target language. Yet, researchers can now begin to understand additional components of anxiety that were not examined previously in online foreign language courses in a more nuanced manner.

Keywords:

Anxiety, Stress, Online Learning, Foreign Languages, World Languages, e-Learning

1. Introduction

Anxiety in foreign language classes has been a well-researched topic studied by numerous educational theorists (Blake, 2008; Chametzky, 2013a, 2017; Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986; Krashen, 1981; Pichette, 2009; von Wörde, 2003) . Foreign language theorists and educators know that anxiety and the associated stress are obstacles for foreign language students (Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986) . Such anxiety may result, as Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986) mentioned, from the inability (perceived or real) to speak, from the fear of making a mistake, or from the unfavorable appraisal. It is equally possible that students may experience anxiety because of the difficulty in using and understanding the language’s rules, self-esteem (Aslim-Yetiş & Çapan, 2013) , or other variables. While these components may be valid in a traditional learning environment, it is not yet evident that they manifest themselves in an online environment.

In an asynchronous online environment, however, from where do the stress and the associated angst of learners come? Is the unease caused by the need to produce the foreign language orally, the unknown of the online environment, the use of the technology, a combination of these elements or something else? Research on anxiety in the online foreign language venue is sparse; at best, however, researchers may infer from extant research in a traditional learning environment what those elements of unease might be. What is not clear is which type or component of anxiety is most prevalent and experienced by online foreign language learners (Aslim-Yetiş & Çapan, 2013) . The objective of this research is to address that gap by further examining the angst felt by learners in an online foreign language experience.

2. Purpose

The purpose of this descriptive, qualitative pilot study is to develop a more nuanced understanding of foreign language anxiety in the online learning environment. “Lorsqu’un apprenant est anxieux, son estime de soi se réduit, sa confiance en lui diminue et ainsi, est moins tenté de prendre des risques” (Aslim-Yetiş & Çapan, 2013: p. 14) . Likewise, “les apprenants anxieux sont moins compétents en production orale” (Aslim-Yetiş & Çapan, 2013: p. 14) . With a deeper understanding, educators, course designers, and post-secondary administrators will be in a better position not only to aid students who exhibit symptoms of anxiety but also to help bolster their self-esteem, self-efficacy, and confidence levels (Aslim-Yetiş & Çapan, 2013) .

3. Problem

While anxiety has previously been studied in foreign language environment (Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986) , no information exists about anxiety in an online foreign language environment. Without having a detailed understanding of potential problems in such an environment (Cochran & Benuto, 2016) , educators, administrators, and course designers would not be able to help struggling, suffering students. In the 21st century, with the ubiquitousness of the Internet and the increased prevalence of online learning (Allen & Seaman, 2010, 2013) , a need exists for such a study.

4. Research Questions

There exist two questions that guided the researcher in this study. These questions are stated as follows:

1) What element (or elements) of anxiety causes (or cause) the most stress in learners?

2) How do these potential elements of anxiety interact with each other?

5. Literature Review

Foreign language classes are not like other classes (Myers, 2008) for in these classes, learners invariably leave their realm of comfort (Chametzky, 2013a) . In traditional and online elementary foreign language classes, students must rediscover communication and grammar. The abilities of intelligent adults to interact with one another become greatly reduced because they are not able to express themselves, as they are accustomed. The students in these courses must consciously work on circumlocution, accept minimal infantine utterances as acceptable, and suppress the desire to say what they truly wish to say. Such restrictive linguistic ability may cause great anxiety in learners (Horwitz, Horwitz, & Cope, 1986) .

Though Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope (1986) defined foreign language anxiety as “a distinct complex construct of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviours related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of language learning process” (p. 128), in asynchronous online foreign language classes, additional elements (Gabarre & Gabarre, 2010) of disease exist may exist along with the decreased ability to express oneself (Aslim-Yetiş & Çapan, 2013; Tóth, 2012) . In an online environment, it is possible to include three additional points of angst: 1) the experience of learners functioning in an online environment, 2) the fear of some learners regarding the technological tools, and 3) the complicated learning environment (Chametzky, 2013b) . Though these elements exist in an asynchronous online environment, it is important to realize that each does not work in isolation for the environment is complex.

The first point of angst is a misalignment between experience and expectation. Kiliç-Çakmak, Karataş, and Ocak (2009) opined in order for interaction to exist in an online course, learners’ experience needs to match with their expectations. If a student is expecting the type of learning experience he or she had in a traditional class, a clear mismatch of expectation and experience will happen. The misalignment of experience and expectation may impinge on other components in an online learning environment.

A second element of learner anxiety concerns fear. It might be that the inexperience of a learner towards the online learning environment makes him or her fearful. Similarly, if a student has previously had a bad experience with technology he or she might subsequently develop a fear of it. Such technophobia (Anderson & Williams, 2011; Nsomwe-a-nfunkwa, 2010) could possibly lead to debilitating effects for the student. The causes for this fear could be multifaceted involving any or all of the following components: 1) a lack of self-efficacy, 2) an inability to develop “knowledge mobility” (Jashapara & Tai, 2011: p. 71) , or 3) an overall non-descript anxiety (Tran, 2012) . Each of these three elements may be intertwined with the other components, as it might not be possible to separate one from another.

5.1. A Lack of Self-Efficacy

If a learner is not expecting a learning environment where knowledge is not obtained passively (Jashapara & Tai, 2011) ―as is often the case in a traditional learning environment―then he or she will exhibit great stress. Such a learning environment requires learners to have a firm belief in their own abilities (Aslim-Yetiş & Çapan, 2013) to accomplish a given task. When learners have a negative sense of their abilities to learn effectively or a negative sense of the technological tools’ “perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness” (Jashapara & Tai, 2011: p. 71) ―making allusion to Gibson’s (1986) discussion of affordances and constraints)―disease will ensue. Because of “low thresholds for trying new technologies and high levels of computer anxiety, a traditional classroom setting may be more effective than e-learning interventions” (Jashapara & Tai, 2011: p. 80) .

5.2. An Inability to Use Knowledge

Foreign language educators are no doubt aware of the national guidelines set forth by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) (2012): learners studying a foreign language must be able to communication orally in that target language. From a learners’ perspective, however, an inability may exist preventing some learners from mobilizing knowledge (Jashapara & Tai, 2011) . The idea of actively using information requires a person to incorporate elements of andragogy, self-efficacy, and motivation (Chametzky, 2013b) that might not be within the ability of a learner. Such inability would prevent the application of cognition to practice (i.e., speaking). In a foreign language, cognition (understanding), affect (emotion), and oral production must work in concert one with another if a learner is to succeed in acquiring the target language.

5.3. A Non-Descript Anxiety

Finally, it is plausible that an overall non-descript anxiety (Tran, 2012) might cause learners to be afraid thereby impeding their progress in the online foreign language course. Such anxiety might stem from many possible areas such as a mismatch of learning style versus class presentation style (Chametzky, 2013a) , a dislike of feeling isolated, an inadvertent misconstruing of a written or oral communication, an inability―especially for those people born in 1978 or later―to wait because of the intense desire for immediacy (Meister & Willyerd, 2010) commonplace in their lives, or, possibly a myriad of other causes.

The third and final point of angst for learners stemming from their inexperience could be the extremely complicated online learning environment (Bertin et al., 2010; Salcedo, 2010) ; such an environment might overwhelm the learners. In a face-to-face environment, the transmission of the message is immediate because the communication occurs in real-time. If transmission of the message is broken, it is easy to rectify the situation. In an asynchronous online foreign language environment, shown below in Figure 1, communication is complicated. Not only are multiple layers of technological tools involved (that is, the different browsers used, the LMS, and/or any additional technological tools required), but also the complexity of the foreign language comes into play. In an asynchronous environment, should there be any sort of miscommunication, one of the interlocutors would not be aware of it until a network connection is reestablished and he or she logs into the class area.

Figure 1. Online foreign language environment (Chametzky, 2013b: p. 64) .

5.4. Summary

The acquisition of a foreign language in an asynchronous, online environment is considerably more complex than a traditional learning environment and often poses challenges for some learners. These challenges stem from the various types of discomfort they might experience. If the aforementioned causes of anxiety are reduced while supporting and strengthening the positive affordances (Gibson, 1986) , then, in theory, anxiety should be reduced. However, if one of the elements is not aligned with the others, then the affective filters (Chametzky, 2017) of the learners will undoubtedly increase thereby impeding knowledge.

6. Methodology

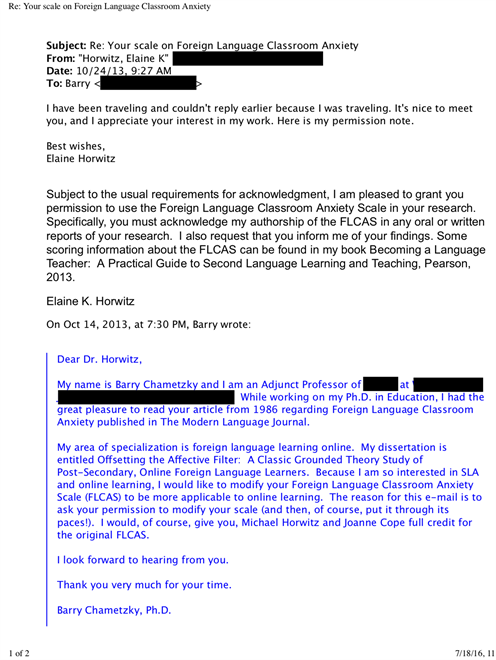

For this qualitative, descriptive pilot study, the researcher developed 37 questions adapted with permission from Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986) (see Appendix A). The newly created instrument, henceforth referred to OWLAS (Online World Languages Anxiety Scale), was then validated by four experts in the field. Modifications to the questions were made in accordance with their comments and suggestions.

With only seven participants, it is evident that the study is not complete. Yet, the data presented here are important and point to further, necessary study. With that idea in mind, then, it is reasonable to say that the research done thus far was a rather small pilot study.

7. Participants

The instrument was administered to participants throughout the United States who had taken at least one online foreign language class. Initially, the research received IRB approval from a school in Springfield, Missouri to administer the questionnaire to online students in the Fall of 2013 and the Spring of 2014 (academic year 2013-2014). However, because of insufficient participation, the researcher discontinued the study at that location. In the Spring of 2016, the researcher posted a request for participation to numerous LinkedIn groups. In both instances, participants were given an Informed Consent to read and acknowledge; participation was anonymous. Minimal demographic information obtained was insufficient to identify participants. For this research study, 7 participants (n = 7) were involved.

8. Instrument

The impetus for the Online World Languages Anxiety Scale (OWLAS), came from the instrument done by Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope (1986) . The questions used in the OWLAS study are different from those presented by Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope (1986) . However, similarity exists. As such, permission was requested and granted for such modifications.

Anxiety can manifest itself because of several different criteria and may stem from different elements that are related to behaviors and emotions that students exhibit or suppress. As such, the questions in the instrument presented in this section may be subdivided into the following 12 categories: 1) comfort, 2) embarrassment, 3) concern, fear, and overwhelm, 4) help, 5) linguistic interference, 6) listening, 7) inadequacies, 8) oral production, 9) the need to practice saying or writing before submission, 10) positive thinking, 11) putting oneself down, and 12) demographics. The chart presented in this section shows a breakdown of the questions in each of the aforementioned categories. The total number of questions in each section is given in parentheses (Table 1).

The 37-question OWLAS instrument can be subdivided into two groups consisting of 33 questions concerning online foreign language and 4 questions regarding demographics. For the 33 questions, participants responded via a 5-point Likert-scale: Strong Agree, Agree, Neither Agree Nor Disagree, Disagree, and Strongly Disagree. Here are the questions in the OWLAS.

Online World Language Anxiety Scale

Please respond to each question with respect to your online foreign language class.

1) I am anxious when I need to record myself speaking in the foreign language.

Table 1. Breakdown of questions in OWLAS.

2) I have sufficient time and opportunities to prepare before I give an oral response in the foreign language.

3) I get anxious when I have to do listening exercises in the e-book or online homework and cannot understand the speakers in the foreign language.

4) I have to write down my answers so I feel confident in them before I can record them for class.

5) I have to practice saying my answers several times so I feel confident in them before I can record them for class.

6) I am anxious about making mistakes in the online foreign language class when I participate orally.

7) I am anxious about making mistakes in the foreign language when I submit written work in my class.

8) I would enjoy taking more online foreign language classes.

9) I am at ease during oral tests.

10) I am at ease during written tests.

11) I feel confident in my speaking abilities in class.

12) I feel confident when I write in the foreign language.

13) I would feel anxious if I were around native speakers of the foreign language and tried speaking with them in their native language.

14) I am comfortable doing several things at one time (for example, reading and listening or writing and listening) in my online foreign language class.

15) I am comfortable using all the required technological tools (for example, but not limited to web browser, learning management system [like Blackboard], multimedia tools, Discussion Board, and so on) in my online foreign language class.

16) Based on what I read and hear in the course area, I think other students are doing better in this class than I.

17) I ask for help from the instructor publicly in the Discussion board when I have questions.

18) I ask for help from the instructor privately via e-mail when I have questions.

19) I ask for help from other students when I have questions.

20) I am concerned about the consequences of failing my online foreign language class.

21) In my online foreign language class, I become so nervous that I forget things I studied.

22) Because my class moves so quickly, I am anxious about falling behind in the coursework.

23) I feel more tense and nervous in my online foreign language class than in my other classes (traditional or online).

24) I feel overwhelmed by the number of grammar rules you have to learn to speak a foreign language.

25) Because of my anxiety, I become more confused when I study for a test.

26) I feel overwhelmed by the complexity of the online learning environment.

27) I do not know how the required assignments and tasks contribute to my success in the online foreign language course.

28) I use positive thinking (or other calming stimuli) to reduce my anxiety and stress from the online foreign language class.

29) I want to take another online foreign language class.

30) I have studied one or more foreign languages prior to this one.

31) Words from other foreign languages “pop up” when I try to use the current language.

32) I am anxious when words from other foreign languages “pop up” while I am trying to use the current language.

33) My lack of understanding of grammar in my native language makes it difficult for me to succeed in my online foreign language class.

34) Gender: __ M__ F

35) Age Bracket: ___ 18 - 25

___ 26 - 30

___ 31 - 35

___ 36 - 40

___ 41 - 45

___ 46 - 50

___ 50 - 55

___ 56 and older

36) How much experience with online classes do you have?

___ less than one year

___ 1 - 3 years

___more than 3 years

37) Length of time in foreign language classes?

___ 8 weeks

___ 12 weeks

___ 15 weeks

___ other (please specify)

9. Results

9.1. Internal Consistency and Validity

The Standard Deviation for this small pilot study ranged between. 4 (question 11 regarding comfort) and 1.83 (question 20 regarding concern). In calculating Cronbach’s alpha, the researchers determined a high internal consistency in the questions (a = 1.0). While a score of 1.0 may initially surprise some people, as generally the value is ideally in the.8 range, the value is reasonable because of the extremely small sample size; the elevated value of Cronbach’s alpha occurred because of the small sample size.

Additionally, the questions used in this instrument were derived from the instrument that Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope (1986) had used. However, the questions for this instrument were modified to reflect online foreign language learning. As such, several experts in the field―not part of the pilot study―reviewed the questions for reliability and validity. The researchers made appropriately modifications according to the comments of the experts. Therefore, based on Cronbach’s alpha score and the review of the experts, the questions in this study have been proven to be reliable and valid.

9.2. Data Analysis

The instrument is comprised of the following 12 categories of questions: 1) demographics, 2) comfort, 3) embarrassment that resulted in additional anxiety, 4) concern/fear/overwhelm (CFO) because of and in the online environment, 5) asking for help, 6) linguistic interference, 7) listening, 8) personal inadequacies, 9) oral production, 10) the need to practice writing or saying work before it is submitted, 11) positive thinking, and 12) putting oneself down. Each of the categories will be analyzed in turn. Admittedly, to have only seven participants (n = 7) is, at best, a mini-pilot study. Yet, even with a small number of participants, the data presented here are valuable and point to the need for further, more in-depth research.

9.2.1. Demographics

For the instrument items concerning participant demographics (questions 34, 35, 36, and 37), though it might be incorrect to talk about generalizability in a study with only a handful of participants, given the varied ages, experience with online courses, and length of time spent in the foreign language class, it is evident that participants come from different environments with varied experiences. As such, it is accurate and indeed correct to say that the results of this study are not limited to millennials or any one age bracket or experience level.

9.2.2. Comfort

Though the environment of online learning is complex, it is clear from question 15 (“I am comfortable using all the required technological tools (for example, but not limited to web browser, learning management system [like Blackboard], multimedia tools, Discussion Board, and so on) in my online foreign language class.”) that technology is neither an impediment nor something that causes anxiety for participants. All the participants agreed or strongly agreed that they were comfortable using the required technology. This statement and the demographic information are rather important as the implication is that millennials are not the only people comfortable with technology and online learning.

A number of items dealt with comfort (questions 8 - 12, 14, 15, and 29). A substantial number of participants (42.9%) agreed with the statement (question 8) that they would enjoy taking another course. Nearly fourteen percent (14.3%) disagreed and 42.9% were indifferent. Yet, for question 29 (“I want to take another online foreign language class”) the results were a bit different: 57.1% were indifferent and 42.9% responded that they agreed and strongly agreed with the statement. Given the anxiety that all students feel at one time or another, it is remarkable that so many students would want to take another online foreign language course. These ideas are confirmed with question 26 (dealing with concern, fear, and feelings of overwhelm in an online environment) in which learners did not feel overwhelmed by the online learning environment: 57.1% of participants strongly disagreed with the statement “I feel overwhelmed by the complexity of the online learning environment”. Only 14.3% of participants strongly agreed, disagreed, and neither agreed nor disagreed.

For the question about comfort during written exams in the target (or foreign) language (question 10), participants were in the agree to disagree range; 42.9% responded that they neither agreed nor disagreed and 42.9% disagreed. The remaining 14.3% agreed with the statement that “I am at ease during written exams”. One possible reason for this anxiety is that an exam is taking place. Perhaps students have test anxiety and the foreign language component compounds such anxiety.

For oral exams and speaking abilities, results were similar. For question 9 (“I am at ease during oral tests.”), students mostly disagreed (70.5% of the participants responded with Disagree or Strongly Disagree). These findings match the earlier questions about oral abilities. With question 11 (“I feel confident in my speaking abilities in class.”), 71.4% of the participants disagreed while 28.6% were ambivalent about their confidence levels. These results point to speaking as an element that causes anxiety in novice learners. For the question about writing in the target language (question 12―“I feel confident when I write in the foreign language.”), 42.9% were ambivalent (neither agree nor disagree) while 42.9% were in the Agree and Strongly Agree ranges. Only 14.3% of the participants disagreed. One reason for the increased confidence in writing may be that writing is easier for many students compared with speaking.

Finally, in an online foreign language environment, students are often required to multitask in order to complete tasks. In question 14 (“I am comfortable doing several things at one time (for example, reading and listening or writing and listening) in my online foreign language class.”), nearly half of the participants responded that they were comfortable multitasking. Nearly 17% of the participants (16.7%) responded strongly agreed that they are comfortable multitasking. Only 16.7% were ambivalent; only 16.7% disagreed about their comfort in multitasking.

9.2.3. Embarrassment Resulting in Additional Anxiety

Questions 6 (“I am anxious about making mistakes in the online foreign language class when I participate orally.”), 7 (“I am anxious about making mistakes in the foreign language when I submit written work in my class.”), and 13 (“I would feel anxious if I were around native speakers of the foreign language and tried speaking with them in their native language.”) address anxiety and situations in which embarrassment could exist. Participants expressed that oral communication is an extremely stressful activity (question 6). Nearly 43% (42.9%) of the participants responded that they agreed or strongly agreed that when they participate orally in an online foreign language class, they are anxious about speaking and making mistakes. Only one participant (14.3%) disagreed. Similarly, if these learners were around native speakers and needed to converse with them in the target language (question 13), 42.9% agreed strongly that they would be rather anxious. Nearly 29% of participants (28.6%) either agreed or were neutral about possible anxiety when communicating with native speakers.

On the other hand, for written work (question 7), the answers were more spread out: 14.3% of participants strongly agreed, disagreed, and strongly disagreed that they were anxious about making mistakes in the target language when submitted written work in class. The other participants, 28.6%, either agreed or were ambivalent about their feelings.

The implication with these statistics is that fewer students feel anxious when they write a foreign language than when they are required to speak it. This assertion makes sense when one considers the temporality of the two media. With oral communication, there is minimal or no time to reflect on the numerous grammatical constructions required for a comprehensible response. With writing, though, a person could revise his or her ideas before submission. When viewed in this light, then, writing would seem to be easier than speaking.

9.2.4. CFO (Concern/Fear/Overwhelm) Because of and in the Online Environment

For questions 20 - 26, not surprisingly, because online foreign language classes tend to seem to move more quickly than traditional ones (due to less in-class, direct instruction time and the inexperience of students to direct their own learning), the participants were rather anxious about keeping up with the class; they were also extremely anxious about the consequences of failing. Interestingly, though, a “disconnect” exists between questions 20 (“I am concerned about the consequences of failing my online foreign language class.”) and 22 (“Because my class moves so quickly, I am anxious about falling behind in the coursework.”); while students are concerned about the consequences of failing their online course (57% responded that they strongly agreed), the speed of the course is only a concern to approximately 42% of the respondents (n = 3). Nearly the same percentage of participants disagree that they are anxious about failing the course. Therefore, a connection could possibly exist between the consequences of failing the course and its speed.

Not surprisingly, nearly all (85.7%) of participants felt “overwhelmed by the number of grammar rules you have to learn to speak a foreign language” (question 24). No doubt, the learners do not realize that their native language is perhaps as or more complicated than the target language. Yet, because they learned their native language as a child through many hours of hearing it, they are not cognizant of this fact. Perhaps because of the numerous grammatical rules and for other, as yet unknown, reasons, students are nervous and tense in online foreign language classes compared with other classes (question 23―“I feel more tense and nervous in my online foreign language class than in my other classes.”). More than half of the participants (57.2%) responded either that they strongly agreed or agree to this question. No participant responded that they strongly disagreed and only one participant (14.3%) responded with Neither Agree or Disagree. The remaining participants (28.6%) disagreed with the statement. Because of the skew of these statistics, perhaps learners are forced, in these language classes, to focus more than they would in non-foreign language courses.

Finally, the statistics for question 23 were similar to the responses for question 25 (“Because of my anxiety, I become more confused when I study for a test.”). More than half of the respondents (57.2%) strongly agreed or agreed with question 25. The remaining participants (42.9%) either disagreed (28.6%) or strongly disagreed (14.3%) with the statement. Because of this intense focus, and the need for exams in an (online) educational environment, students are tense and may forget things more easily (question 21―“In my online foreign language class, I become so nervous that I forget things I studied.”) than if the course were taught in their native language. The statistics support this assertion: 28.6% of the respondents strongly agreed and 14.3% agreed that they get so nervous that they forget previously learned information. Nearly fourteen percent (14.3%) strongly disagreed and responded with a neutral answer about their forgetfulness. Only one participant strongly disagreed with question 21.

9.2.5. Asking for Help

It is evident from the data for questions 17 (“I ask for help from the instructor publicly in the Discussion board when I have questions.”), 18 (“I ask for help from the instructor privately via e-mail when I have questions.”), and 19 (“I ask for help from other students when I have questions.”) that students prefer asking the instructor for help rather than peers. Between asking for help publicly or privately, all the participants preferred asking for help from the instructor privately. The results showed that learners do not want to show their ignorance or confusion in public; they want to save face from their peers. Additionally, because nearly one third of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the idea of asking peers for help (question 19), they recognized that perhaps the peers might not be as knowledgeable in the subject area as the instructor.

9.2.6. Linguistic Interference

When learning a second or subsequent foreign language―regardless of the timeframe―it is reasonable to expect that previous words and ideas will “come out” when a learner is trying to study a new language. There were two primary objectives of questions 30, 31, and 32. The first was to determine whether participants were first time foreign language learners; the second was to determine to what extent linguistic interference was a factor in anxiety. According to question 30 (“I have studied one or more foreign languages prior to this one.”), 71.4% of the participants have studied one or more foreign languages prior to current one. Strangely, though, 42.9% of participants commented that words do and do not “pop up” when trying to use the current language (question 31―“Words from other foreign languages ‘pop up’ when I try to use the current language.”). One participant (14.3%) responded that “sometimes” such an occurrence takes place. It has been the experience of one of the researchers, that whenever a second or third language is taught, linguistic interference is a common occurrence. It would have been expected, then, that more than the 42.9% of participants (n = 3) would have agreed with question 31 and fewer than 42.9% would have disagreed. Based on the results of question 32 (“I am anxious when words from other foreign languages ‘pop up’ while I am trying to use the current language.”), only 14.3% of the participants strongly agree that they become anxious when other foreign language words occur inadvertently. Twenty eight percent (28.6%) were ambivalent while 42.9% disagreed and 14.3% strongly disagreed.

9.2.7. Listening

Question 3 (“I get anxious when I have to do listening exercises in the e-book or online homework and cannot understand the speakers in the foreign language.”) involves listening and anxiety. Most participants (42.9%) reported that they strongly agreed with the statement. Nearly 30% (28.6%) responded that they agree with the statement. Only 14.3% neither agreed nor disagreed and disagreed with the statement. It is reasonable to presume that because learners are not as familiar with the target language as they are in their native language, they may benefit from seeing the text as they listen to it. It is also reasonable to presume that if learners do not understand the speakers in the oral exercises, it could be due to the perceived quick rate of speech. Very often, oral exercises are said by native speakers at a quicker rate-of-speech from that of the instructor.

9.2.8. Personal Inadequacies

For questions 27 and 33, it was important to determine whether external influences played a role in student anxiety. In question 27 (“I do not know how the required assignments and tasks contribute to my success in the online foreign language course.”), only 14.3% of the participants (n = 1) agreed that he or she did not know “how the required assignments and tasks” related to and helped learners be successful in the course. Another participant was ambivalent. The remaining participants (70.5%) disagreed and strongly disagreed with the statement.

With question 33 (“My lack of understanding of grammar in my native language makes it difficult for me to succeed in my online foreign language class.”), most participants (57.1%) strongly disagreed and 28.6% disagreed that their lack of understanding of grammar in their native language made it difficult to succeed in the online foreign language course. No participants agreed or strongly agreed. The other participant (14.3%) was ambivalent in his or her opinion. Thus, any possible lack of grammatical knowledge in the native language is not an impediment in the foreign or target language.

9.2.9. Oral Production

For questions 1 and 2, focus was on oral production. Participants felt anxious when they had to speak in the target language. In question 1 (“I am anxious when I need to record myself speaking in the foreign language.”), 42.9% of participants rated strongly agree while 28.6 agreed and 14.3% each disagreed and strongly disagreed. Clearly, the majority of participants were anxious when they were required or speak in the foreign language.

For question 2 (“I have sufficient time and opportunities to prepare before I give an oral response in the foreign language.”), more than 70% of the participants (71.4%) were ambivalent; they responded neither agree nor disagree. Nearly 14% of respondents (14.3%) responded that they strongly agreed or agreed with the statement. The inference that could be made from these statistics is that sufficient preparation (in terms of time and opportunities) can mitigate some anxiety.

9.2.10. Need to Practice Writing or Saying Work before Submission

Confidence plays a significant role in the level of anxiety, based on the data for questions 4 and 5 (“I have to write down my answers so I feel confident in them before I can record them for class.” and “I have to practice saying my answers several times so I feel confident in them before I can record them for class.” respectively). The majority of participants responded with agree and strongly agree to the questions. In both instances, no one strongly disagreed. This information indicates a desire to say the words or ideas correctly the first time. Only two participants (28.6%) disagreed with the need to write down answers to “feel confident in them before” the responses could be recorded. Given these statistics, students need to be mindful that mistakes will most certainly happen in a foreign language environment; perfection is an unrealistic dream―especially in lower-level foreign language classes even though learners want to be perfect. It is possible that a relationship may exist between the need to practice what will be said and the strong desire to save face in front of peers and not be embarrassed. After all, no one wants to feel embarrassed in front of his or her peers.

From a descriptive statistical perspective, 57.1% agreed with question 4 (the need to practice writing answers before recording them); 14.3% strongly agreed and 28.6% disagreed. For question 5 (the need to practice saying answers before they are recorded for class), 42.9% strongly agreed and agreed while 14.3% were indifferent.

9.2.11. Positive Thinking

Question 28 (“I use positive thinking [or other calming stimuli] to reduce my anxiety and stress from the online foreign language class.”) involved positive thinking and reinforcement of optimistic thoughts. According to participants, nearly 30% (28.6%) strongly agreed, agreed, and neither agreed nor disagreed that they used positive reinforcement in online foreign language classes. Only 14.3% disagreed with the statement. From a psychological perspective, giving oneself positive thoughts helps reduce anxiety. Thus, in the percentages, it is clear that based on their actions, many students are anxious and try to alleviate their anxiety. It was not clear from the data whether positive thinking and reinforcement were the only ways participants alleviated anxiety.

9.2.12. Putting Oneself down

For the results of the question about putting oneself down (question 16―“Based on what I read and hear in the course area, I think other students are doing better in this class than I.”), five participants responded that they neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement. Nearly 14% (14.3%) of the participants strongly agreed and disagreed. These statements may indicate that learners are not able to or do not perceive their peers in a superior position than they. It would be reasonable to imagine that if participants felt that “other students [were] doing better in the class”, then anxiety levels would have existed and increased. That they are not feeling this way helps keep anxiety in check―at least to the extent possible.

9.3. Summary

Foreign language learners are generally comfortable using the online technology but are not comfortable speaking; they do not want to make mistakes and feel embarrassed even though mistakes are a normal part of language acquisition. When they have questions, students would rather ask the instructor a question privately than be embarrassed asking peers in a public venue. Learners prefer writing in the foreign language than speaking it. When they need to speak the language, they prefer to have time to prepare the responses. While speaking causes anxiety, so does listening as learners cannot always see the text and the native speakers in the activities speak at a faster pace than the instructor.

As with all traditional classes, learners do not want to fall behind and fail. This fear is heightened in an online foreign language class for a number of reasons. Perhaps they are not accustomed to online learning where the instructor is the facilitator and guide, not the sage who is pouring knowledge into their heads; such fear could fuel anxiety. Or, perhaps they are not accustomed to learning grammatical rules because their knowledge of grammar in the native language might be limited.

It is not yet evident whether positive thinking is the only way participants alleviate anxiety in online language classes. Likewise, it is not clear whether linguistic interference causes high anxiety in novice learners. Many learners are not well versed in grammar in their native language as they might want to be. To that end, it could be highly desirable to have a detailed explanation with examples of the various grammatical rules in the native language posted in the course area and constructions in the native language to which learners could refer as they study the target language. Finally, though self-put downs may be normal in everyday life unfortunately, they do not affect the online foreign language learning process.

10. Conclusion

As anxiety levels of learners increase and they become increasingly distressed, they may overtly or covertly exhibit certain behaviors (Chametzky, 2017) as coping strategies to deal with the situation and the increased stress. In an online environment, student anxiety may not always be visible to the educator and may be more systemic than the foreign language class. Yet, anxiety must be reduced. The first step is understanding from where the anxiety comes. With this study, researchers can understand the various components of anxiety in online foreign language courses. Armed with the new knowledge from this study about anxiety, it would behoove educators and course designers to modify online foreign language courses―and perhaps other courses as well―so that learners have more opportunities to practice orally with minimal stress. In other words, it would be highly valuable for educators and course designers to take their future cues from the National Institute of Health (1979) (often referred to as the Belmont Report) and reduce anxiety levels to “do no [further] harm” (p. 3).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to offer a very special “thank you” to several people for their help during this research. First, Dr. Kelley Walters helped with the validation of the instrument and the development of some of the questions. Second, Dr. Rita Marie O’Brien for her statistical knowledge and insights. Finally, Dr. Elaine Horwitz for her permission to modify her instrument for the online environment. This research could not have been accomplished without their assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Cite this paper

Chametzky, B. (2019). The Online World Languages Anxiety Scale (OWLAS). Creative Education, 10, 59-77. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2019.101005

References

- 1. Allen, I., & Seaman, J. (2010). Class Differences: Online Education in the United States, 2010 (pp. 1-26). Needham, MA: The Sloan Consortium. http://sloanconsortium.org/publications/survey/class_differences [Paper reference 1]

- 2. Allen, I., & Seaman, J. (2013). Changing Course: Ten Years of Tracking Online Education in the United States, 2010 (pp. 1-26). Needham, MA: The Sloan Consortium. http://sloanconsortium.org/publications/survey/class_differences [Paper reference 1]

- 3. Anderson, L., & Williams, L. (2011). The Use of New Technologies in the French Curriculum: A National Survey. The French Review, 84, 764-781. [Paper reference 1]

- 4. Aslim-Yetis, V., & Capan, S. (2013). L’anxiétélangagière chez des étudiantsturcsapprenant le fran?ais. The Journal of International Social Research, 6, 14-26. http://www.sosyalarastirmalar.com [Paper reference 7]

- 5. Bertin, J.-C., Gravé, P., & Narcy-Combes, J.-P. (2010). Second Language Distance Learning and Teaching: Theoretical Perspectives and Didactic Ergonomics. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-61520-707-7 [Paper reference 1]

- 6. Blake, R. (2008). Brave New Digital Classroom: Technology and Foreign Language learning. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Paper reference 1]

- 7. Chametzky, B. (2013a). Offsetting the Affective Filter and Online Foreign Language Learners. http://www.igi-global.com/open-access/paper/offsetting-affective-filter-classic-grounded/7 [Paper reference 3]

- 8. Chametzky, B. (2013b). Offsetting the Affective Filter: A Classic Grounded Theory Study of Post-Secondary Online Foreign Language Learners. Doctoral Dissertation, San Diego: Northcentral University. http://pqdtopen.proquest.com/#results?q=3570240 [Paper reference 3]

- 9. Chametzky, B. (2017). Offsetting the Affective Filter. Grounded Theory Review, 16. http://groundedtheoryreview.com [Paper reference 3]

- 10. Cochran, C., & Benuto, L. (2016). Faculty Transitions to Online Instruction: A Qualitative Case Study. The Online Journal of Distance Education and e-Learning, 4, 42-54. http://www.tojdel.net [Paper reference 1]

- 11. Gabarre, C., & Gabarre, S. (2010). Raising Exposure and Interactions in French through Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 18, 33-44. [Paper reference 1]

- 12. Gibson, J. (1986). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. http://books.google.com/books?id=DrhCCWmJpWUC&printsec=frontcover&dq= james+gibson&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RdP1TqaDJOjj0QHJ9fmFAg&ved=0CEYQ6AEwAA#v= onepage&q=james%20gibson&f=false [Paper reference 2]

- 13. Horwitz, E., Horwitz, M., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70, 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x [Paper reference 10]

- 14. Jashapara, A., & Tai, W.-C. (2011). Knowledge Mobilization through e-Learning Systems: Understanding the Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Anxiety on Perceptions of Ease of Use. Information Systems Management, 28, 71-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2011.536115 [Paper reference 5]

- 15. Kilic-Cakmak, E., Karatas, S., & Ocak, M. (2009). An Analysis of Factors Affecting Community College Students’ Expectations One-Learning [sic]. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 10, 351-363. http://www.infoagepub.com/quarterly-review-of-distance-education.html [Paper reference 1]

- 16. Krashen, S. (1981). Second Language Acquisition and Second Language Learning. Pergamon. https://www.sk.com.br/sk-krash.html [Paper reference 1]

- 17. Meister, J., & Willyerd, K. (2010). Looking Ahead at Social Learning: 10 Predictions. https://www.td.org/magazines/td-magazine/looking-ahead-at-social-learning-10-predictions [Paper reference 1]

- 18. Myers, C. (2008). Divergence in Learning Goal Priorities between College Students and Their Faculty: Implications for Teaching and Learning. College Teaching, 56, 53-58. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.56.1.53-58 www.pdx.edu/sites/https://www.pdx.edu.cae/files/StFacLrngGls.pdf [Paper reference 1]

- 19. National Institute of Health, Office of Human Subjects Research (1979). Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html [Paper reference 1]

- 20. Nsomwe-a-nfunkwa, B. (2010). Sharing the Obstacles to Distance Education at the University of Kinshasa. Distance Learning, 7, 83-85. http://www.infoagepub.com/index.php?id=89&i=59 [Paper reference 1]

- 21. Pichette, F. (2009). Second Language Anxiety and Distance Language Learning. Foreign Language Annals, 42, 77-93. http://www.actfl.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3320 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2009.01009.x [Paper reference 1]

- 22. Salcedo, C. S. (2010). Comparative Analysis of Learning Outcomes in Face-to-Face Foreign Language Classes vs. Language Lab and Online. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 7, 43-54. http://journals.cluteonline.com/index.php/TLC https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v7i2.88 [Paper reference 1]

- 23. Tóth, Z. (2012). Foreign Language Anxiety and Oral Performance: Differences between High vs. Low-Anxious EFL Students. US-China Foreign Language, 10, 1166-1178. [Paper reference 1]

- 24. Tran, T. (2012). A Review of Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope’s Theory of Foreign Language Anxiety and the Challenges to the Theory. English Language Teaching, 5, 69-75. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n1p69 [Paper reference 2]

- 25. von Worde, R. (2003). Students’ Perspectives on Foreign Language Anxiety. Inquiry, 8, 21-40. http://www.vccaedu.org/inquiry/inquiry-spring2003/i-81-worde.html [Paper reference 1]

Appendix A: Permission to Modify the FLCAS