Creative Education

Vol.06 No.11(2015), Article ID:57451,7 pages

10.4236/ce.2015.611112

Clinical Didactic Analysis of the Practices Declared in Soccer and Identification of a “déjà-là” Decisional of Two Beginner’s Teachers

Maher Guerchi1, Hanene Lengliz1, Mohamed Ali Hammami2, Denis Loizon3, Marie-France Carnus1

1UMR ETFS, Université de Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Toulouse, France

2Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education in Kef, Kef, Tunisia

3ESPE Bourgogne, SPMS (EA 4180), Université de Bourgogne, Dijon, France

Email: makwiss@yahoo.fr

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 25 May 2015; accepted 23 June 2015; published 26 June 2015

ABSTRACT

In the context of teaching of football at school, we are particularly interested in how new teachers use and transform the knowledge learned in the act of teaching and the ways of linking the personal determinants and the professionally acquired knowledge, that is to say, the involvement of the private sphere of the teacher in the educational process of the football field. From a didactic clinical study of two cases―Riadh, a specialist in football and Jalel, an athletics specialist, we demonstrate that certain knowledge is presented implicitly in connection with a “pre-acquired experimental, intentional and conceptual Déjà-Là1” of the two teachers. These personal didactic determinants have an impact on certain decisions, and they influence the choice of certain knowledge and guide the instructional behavior of the two teachers. So, we are committed to highlight the existence of similarities and differences shown in the study of questionnaires and analysis of preliminary interviews.

Keywords:

Declared Practices, Clinic Didactics, Decisional déjà-là, Teacher Trainees, Personal Determinants, Football

1. Introduction

The analysis of teaching practices has revealed considerable divergences between teachers’ intentions and their decisions, and between what is expected and actual practice ( Durand, 1996 ). In fact, these differences are intensifying as the teacher finds him/herself in quite unusual situations marked by multiple contingencies. These contingencies are related to the institution when the teacher is teaching under difficult conditions due to lack of space, absence of equipment, etc. Other contingencies are related to students when the teacher is confronted with increasingly important groups of students which are a mixture of girls and boys, weak and good ones, and this makes the performance of sessions rather intricate and hard to handle. In addition to this, the “cultural misunderstanding” between teachers and students is sometimes due to their highly divergent conceptions ( Goirand, 1998 ). And finally, the contingencies related to the selection, construction and transmission of knowledge are highly influenced by cultural references. These references are presumably the result of the growing gap between high-performance football practices and school practices.

Beyond the difficulties and constraints related to the football teaching practice, many internal factors sometimes occur without the teacher’s realization and they seem to have a decisive role in the teacher’s decision- making. Thus, the PE (Physical Education) teacher is entitled to make objective or subjective choices, in an urgent attempt to meet the requirements of the teaching situation. This decision-making process is “both an intimate and a specific phenomenon” ( Carnus, 2003 ). In this context, Loizon (2004) considers that these phenomena act as “didactic action filters”. These filters have similar effects on the “intent layers” reported by Portuguese (1998) , which implicitly or explicitly guide the teacher’s choices before and during the didactic action. “This particular filter is always present and acts as a representation of the world, the other and authentic” ( Blaquier, 2003 ).

This research is interested in teaching football. It aims to implement the determinants of the teacher’s didactic action ( Goigoux, 2007 ) and in particular the personal determinant which is very heterogeneous (aims and objectives, knowledge and know-how, designs, values and beliefs, experience and training) ( Goigoux, 2007 ). In other words, the part of subjectivity is involved in the educational treatment of the taught physical activity ( Loizon & Carnus, 2014 ). In PE, workshops in clinical teaching ( Terrisse, Carnus, & Loizon, 2010 ) show that the activity of PE (EPS) teachers is also determined by a very personal “déjà-là” which is a hidden part of the teacher’s decision-making process ( Carnus, 2002 ). Thus, this “déjà-là” provides the teacher, at some point, with motives in the framework of his professional activity.

In order to monitor the evolution of knowledge overtaken in the classroom, the analysis of teaching practices requires the building up of a temporality that takes into account the history of the “didactic subject” and goes back in time as far as possible to have accurate information about his teaching path, on his report of the physical activity and sports (APS) and on what happened before. This, firstly, allows us to have access to the personal experience of both the teaching subject and the taught activity. Through a questionnaire and preliminary discussions, we have empirically identified experiential and epistemological reports of each teacher concerning their knowledge of the football field.

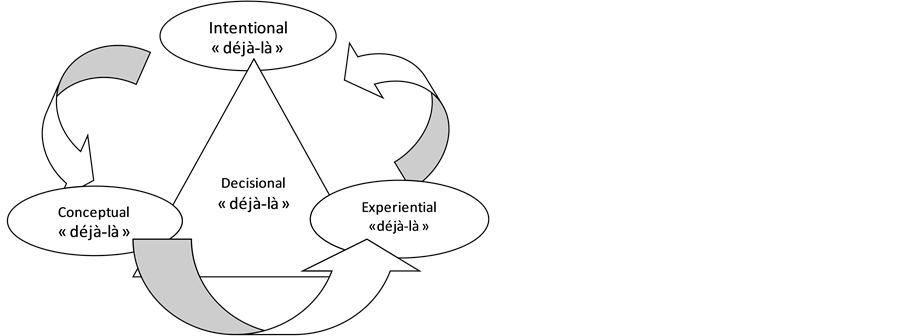

This methodological procedure formulates the first time of the clinical didactic analysis that allows access, in general, to the teacher’s “Déjà-Là” ( Terrisse, 2000 ). It is also a specific time analysis in clinical didactics, which allows access to the “decisional déjà-là” ( Carnus, 2002 ). In this respect, Carnus considers the “decisional déjà-là” as a hidden part of the teacher’s decision-making process, providing, at some point, motives and reasons in the context of his/her professional activity. Latently and consistently influencing the decisions, this “decisional déjà-là” is made up of three sections that represent three major instances responsible for any decision: “the conceptual déjà-là” “the intentional déjà-là” and “the experiential déjà-là” ( Carnus, 2002 ). These instances act as “didactic action filters” ( Loizon, 2004 ).

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Conceptual “Déjà-Là”

The conceptual “Déjà-là” uses the concept designs that are built with respect to some knowledge. For Giordan & De Vecchi (1987) design is “a driving force enhancing the construction of knowledge and even allowing the necessary transformations” This notion focuses on the cognitive aspect which represents a preamble supporting any decision. However, the designs are “constructed” by the subject following an analysis and a synthesis of a set of information often related to a field of knowledge. The performances, as such, are like a contextual coherent set of ideas: “A representation is a mental phenomenon that corresponds more or less to conscious, organized and coherent cognitive and emotional elements and fields of values for a particular object. Thereof, we find the conceptual elements, attitudes, values, mental images, connotations. It is a symbolic, culturally-deter- mined universe, where spontaneous theories, opinions, prejudices, actions and decisions are forged” ( Garnier & Sauvé, 1999 ). In the professional position of the subject, the performances can be a “form of socially-developed and shared knowledge with a practical aim and contributing to the construction of a common reality for a social group” ( Jodelet, 1989 ). These constructions are not strictly personal, but they appear as mental constructs produced in the community, which refer to the collective consciousness. Thus they contribute to the regulation of the interaction between the individual and his/her material and human environment alleviated in the memory for a long time.

2.2. The Intentional “Déjà-Là”

In its work on decisions, and trying to locate a teacher’s “Decisional déjà-là”, Carnus (2001) defines intention as a “tension towards a goal, the direction of an object”. It is precisely the difficulty to reach such a dimension in a teaching-learning situation. Meanwhile, the location of these intentions is shaped on the verbalization of teachers in the interview and before the implementation of the test. We believe that the intention of a teacher is driven by the unforeseen situation of teaching/learning, which assists in a genesis of intentions due to the sequence and articulation of chronological-genetic decisions on the mesoscopic level of the learning situation.

This genesis that designates the order in which the action should take place for conveying the would-be taught knowledge, implies a chain of intentions which reveals social intentions at the beginning and then turns out thereafter during the phase of interaction within the more personal intentions thus making up a foreshadowing of the internal didactic transposition. Upstream of decisions, more or less conscious intentions are part of the hidden part of the decision-making process that refers to the causes, the reasons and motives, and which partly determines the teacher’s choice of teacher before, during and after action. The complexity that arises between “intention” and “decision” leads us to believe that teaching is “an impossible activity” ( Freud, 1900 ) within the “layers of intention and intentionality” ( Portuguese, 1998 ), which act as “filters of the didactic action”. Intention directs the choice towards a teacher’s specific teaching content and the way to transmit it in the form of didactic situation.

2.3. The Experiential “déjà-là”

The “experiential déjà-là” refers to the teacher’s experience. It is a manifestation of the experiential knowledge that leads to theorizing. It is a directory for the teacher to “say” and “do” that the researcher must decipher in order to unravel the riddle of practice or the teacher’s experiential knowledge. To access the already-there experiential and identify experiential knowledge, the researcher can use the questionnaire and preliminary interviews. To locate the various “déjà-là” on the clinical side, we refer to the psychoanalytic theory of Freud’s first topic, stating that the two “intentional déjà-là” would be located in the sphere of consciousness. This is actually the objectives clearly expressed in the words of teachers, while the “already-there concept” would be in the preconscious. The “already-there experiential” would turn, firmly rooted in the unconscious as regards to the learner’s experience. When it comes to explaining the practices of teaching, this topic reveals a close relationship between the three instances of “it”, “ego” and “superego”. Therefore, these “déjà-là” acts as personal filters that influence and guide the selection of knowledge qualified by the “didactic intentions” as well as the “educational decisions” taken in the session. In fact, we believe that this phenomenon explains why two teachers who have to teach the same knowledge objects never actually teach the same objects of knowledge because they have fundamentally different “déjà-là” filters, because of their personal history ( Loizon, Margnes, & Terrisse, 2008 ) (Figure 1).

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection Techniques

Our first methodological device is the questionnaire. It aims to highlight the designs, intentions related to the practices of PE teachers. The issues were addressed one by one with a categorization of responses to open questions. In this section we have selected the most significant results in our object of study. All the results of this

Figure 1. Explanatory diagram of the components of the decisional “déjà-là” (Guerchi, 2015).

survey are footnoted. The questionnaire allows the emergence of a “déjà-là” (conceptual, experiential and intentional). This questionnaire allows us to locate the responses of teachers in light of the different variables. Experience, expertise and genre it has an exploratory function regarding the conceptions and representations of teachers, and provides support to account for differences between the designs and actual practices.

The second instrument is the semi-structured interview, this type of maintenance leaves freedom of speech for the teacher when questioned on a particular theme. The talks were held at various schools. They lasted about thirty five minutes; these interviews were recorded and fully transcribed.

3.2. Presentation of the Population

167 teachers randomly recruited filled in the questionnaire: 109 are men and 58 are women; among them, there were 85 teachers working in college, 59 at high school and 23 in elementary schools. Furthermore, 49 say they are “experts” in football. 118, however, are said to be “non-experts”.

Among these 167 PE teachers, we have randomly selected four teachers to participate in our survey, whose teaching experience does not exceed 3 years, two of them are experts in football and the other two have other areas of expertise.

3.3. Presentation of Two Cases

Our first case has the profile of a specialist teacher in football, called Riadh. He holds a Degree in Fundamental Physical Education, a federal diploma and is coach of a football club.

Our second case has the profile of a non-specialist teacher in football, his name is Jalel. He also holds a Degree in Fundamental Physical Education and a federal diploma in Athletics.

3.4. Data Analysis Techniques

To process the questionnaires, we found it useful to use both the method of analysis―“global” and “analytical”. The data collected are processed through the statistical method which is a mathematical set of tests used to calculate what is related to research. For our research, we used the Chi-square test “Chi 2”. The interviews were analyzed by using a method that reports teaching practices. We proceeded first to a “floating” reading for the general sense expressed by the interviewee about the teaching practice, then we process the division of a text, “shears work” ( Bardin, 1998 ), to select “units of meaning” (id.), which represent significant events in relation to football in teaching practices.

4. Two Case Studies Riadh and Jalel

4.1. Designing the Football Field

To bring out the conceptuel “déjà-là”, we used the responses of PE teachers of the following question: “what is your definition of football?”

Quantitative analysis of responses evoked shows that the football discipline appears to PE teachers as an (opposition activity and cooperation) with (44%) of the citations. Other statements reveal Side conceptions relating to collective confrontation with (29%) of citations. For (17%) of statements, football is seen as a (team sport), while only (10%) teacher quotes give football the status of a (male contact sport connotation). A more detailed analysis of the questionnaire of the teacher Riadh shows it is a general trend that sees football as an “opposition activity and cooperation.” Likewise the content analysis of the preliminary interview confirms this attitude “... it is a collective activity based on opposition and cooperation ... it is a competition played between two teams”.

In an attempt to highlight the conceptuel “déjà-là”, of the teacher Jalel, we treated the teacher’s response regarding the design of the football field. Unlike Riadh, Jalel is in a trend more or less minor. For him this is a “team sport”, “football is a team sport consisting of two teams competing...” The notion of “collective” appears as a priority for Jalel.

This analysis, namely the most cited by a panel of PE Teachers, expresses the knowledge acquired throughout the course of the academic training on the football field that is defined according to the literature as a team sport between two teams of eleven players around a ball. It will be seen in this stratum that the PE teachers include in their definition the aspect of confrontation and collaboration that is identical to all collective sports.

Following this analysis, we believe that teachers have “complex conceptual networks, articulating beliefs and conceptions” ( Carnus, 2003 ). It seems that the use of these conceptual networks allows PE Teachers to give meaning to the business of football. This leads us to a more general idea of football as a team sport. Regardless of the context of practice, football assumes a direct confrontation between the two teams; this confrontation involves the collaboration within the same team to achieve a common goal.

4.2. Teacher’s Didactic Intentions

In this part, we will treat only the stated options. For this purpose, we will proceed in the same way as previously. We will extract the “Intentional déjà-là” of the PE teachers for the analysis of the teachers’ reply to the following question: When you are teaching, do you focus on techniques, pedagogy, tactics or strategy?

The centers of interest of PE teachers translate knowledge that would be taught by them. Thus, we can see that the teachers’ interests are always “educational” with (83) declarations, more than (62) statements opt for the “technical” aspect while only (18) statements opt for the “tactical” aspect. After this analysis, we will retain that the teachers’ intentions coincide with the reported didactic, educational and sports references. In the same perspective Riadh positioned himself in a general trend towards the planning of educational goals in school. So his statement confirms this position: “... I emphasize in my work on the development of the spirit of the group ...” he adds, “... I especially focus on the development of the students’ emotional side because I am not convinced personally of a technical or tactical work of an activity in the rather hard working conditions that exist in the majority of schools in our area...”. This intentional déjà-là corresponds to Riadh’s intentions in preferred objectives to teach football in schools.

In these statements, Jalel tells us some of his didactic intentions in relation to the educational goals of these different objectives (educational, technical, and tactical).

Like Riadh, the teacher is interested in the benefit of educational goals. In this sense Jalel says that it will be interesting to work “I think in a football cycle we seek to develop students priority: integration within the group, understanding, respect for the others, compliance with the rules of the game and tolerance... the other goals as the perfection of the game are second...” He adds, “I prefer to develop cognitive skills in my students”.

When one wonders about the content preferred to teach football in schools, quantitative analysis refers us to the “Intentional déjà-là” of PE teachers. It is, in percentage terms, the largest technical knowledge that would be taught in schools. So we read that (29%) opt for “passes” (24%) for “ball control” (19%) for “ball lines” (16%) for “kicks” and only (12%) for the “along kicks”. In the same context, Riadh prefers the planning of technical knowledge within the school: “... it is important to emphasize the basic work such as learning passes, controls ... because boys and girls are alike when dealing with the ball”. Like Riadh, Jalel gives a particular interest for basic techniques to learn how to play football “... in an EP session, I prefer teaching the elementary ABCs of football such as simple techniques, passes, dribbling, shooting and possession of the ball”.

A qualitative analysis of responses evoked by teachers has stated references displayed by the panel. Indeed, there is an illustration of a set of basic technical elements (pass, control, dribbling, ball control and shooting). No teacher evokes for example such specific learning techniques of the goalkeeper, and yet they are part of football since the game always includes the goalkeeper. It is true as far as it is not the most important aspect to teach students at the outset, but it proves the correctness of teacher knowledge in an activity rarely taught in schools.

When it comes to teaching football to a mixed class, the qualitative analysis of the brings us back to Mohamed Ali’s “Intentional déjà-là”. Thus, we can identify in the teacher talk two types of knowledge; technical knowledge chosen for the girls and one tactical for boys “there are not lots of things to learn by girls and boys... for example at the end of a football cycle, boys can arrange to collect the ball and build attacks and master some rules of the game as ‘off sides, kick-off and repair kick’, Also, they know how to officiate a game, and most importantly to me during a game, respect the referee’s decision of the even if the referee is a student and prone to makes mistakes”.

He adds, “they mastered, at the end of a cycle, how to handle the ball, and they can perform any technical gesture such as passing and ball control as well as the use of some terms specific to football, but sincerely they cannot manage a football game”. Unlike Riadh, Jalel offers the same knowledge and technical expertise which is for girls and for boys. Indeed, Jalel does not think teaching another tactical or strategic knowledge. His statements in the interview confirm our hypothesis: “I sincerely believe that during a football cycle I cannot give my students big things in football... I’m not an expert... I do not like football... boys may also play”.

The knowledge mentioned by Riadh expresses his declared intentions and focus on two types of knowledge: technical and tactical for girls and boys. As for Jalel, technical knowledge is at the center of his interests. Following this analysis and aiming to reach the most important goals of this activity in schools, the PE teachers have pedagogical orientation “cognitive, emotional, relational, security rules...”. Also, they have some technical tactics for girls and boys. Indeed, it seems that the two teachers have a complex intentional network. The didactic intentions declared by Riadh and Jalel are certainly a fraction of private intentions of teachers. However, these intentions are used to guide their teaching. This composite network seems to have more or less contradictory relations with the designs.

4.3. Report on Experiential Football

In this part of the study data collected on teaching practices are declarative. Our analysis refers to examples that the PE teacher smoothly describes and develops in his answers. To bring out Riadh’s “experiential déjà-là”, we analyzed the responses to the first question of our questionnaire: “What are the references used to choose the educational content? “Where does the teacher often reveal his experience related to the football field?”

Examinations of all PE teachers show that there is a remarkable disparity in the teachers’ responses. The curricula are most visited by teachers (97 replies) then being admitted in university education (71 responses) and thirdly the PE teachers are using their experiences with sports (44 replies). Any time Riadh in his experiential relation to football, refers to his own experience sports in order to build knowledge of teaching and learning because “I often remember how I used to train when I was young and if I did not have done, I would have difficulty teaching this discipline...” In fact, Riadh makes a kind of transposition of his own experience into his students and what he experienced in civil clubs “I often use my own sport experience”.

In his experiential report of football and unlike Riadh, Jalel refers to formal programs in order to build some knowledge of teaching and learning “for educational program purposes I often refer to the official programs”.

Qualitative analysis of Riadh’s replies concerning the learners’ assessment reveals a cross-reference between the sporting experience and the academic training. To assess a student’s learning in a football cycle, Riadh combines technical circuit with a global game “generally in team games and even in football I use technical circuits to assess student’s individual behavior and a mini-game to assess individual behavior within the group and collective behavior in attack or defense”. However, Jalel’s statements in connection with the evaluation of Learning reveals the use of technical systems “I think I will carry out an evaluation at the end of the cycle as a technical circuit to assess my students on an individual basis…”.

The building of a teaching-learning content relies on the handling of certain educational variables. Riadh is well-positioned to make didactic learning content accessible to learners. Thus, one can note that (35%) quotes refers to the manipulation of the variable “number of the ball touches”, (30%) quotes refer to the variable of “defenders number” (18%) quotes refer to the variables of the game space “and finally (17%) quotezs refer to the handling of the variable “joker player”. Therefore, we find that PE Teachers act first on “digital” variables. In this perspective, Jalel joins Mohamed Ali in the same trend that involves the manipulation of the variable “number of ball touches”.

5. Discussion

The analysis of questionnaires and interviews allowed us to learn more about the nature of the reported teaching practices that appear to be crossed by an identity dimension where personal determinants are present. In this research, we were able to identify consistency between their relationships to knowledge, then we find that Riadh and Jalel select the same educational goals and take an interest in the transmission of technical knowledge. In this analysis, we reach Blanchard-Laville, who indicates that the teacher “brought to stage his/her own report to the mathematical knowledge” and that it is “deeply rooted in the personal history of each [...] It is not knowledge that is exposed; it is the subject” ( Blanchard-Laville, 2001 ).

In the same class, it is for Riadh to teach different educational content based on the student’s gender. While Riadh appears to be divided between girls and boys, Jalel rather seems to propose the same content for boys and girls. In fact, both teachers always offer “something from their deep personal connection to this type of knowledge and what it represents for them” ( Rochex, 1996 ).

The teaching activity is seen as “a creative activity, design and development that questions the theoretical knowledge acquired to relearn, retranslate otherwise and convert” ( Altet, 2004 ). This requires reference to a repository in order to select and build knowledge. In our study we found that Riadh often refers to his sports experience to build an educational knowledge whereas Jalel and like the majority of PE teachers refers to school programs to choose his objectives and build the knowledge to be transmitted to his students. In a way, one can find this logic as PE teachers who filled in the questionnaires are often overwhelmed by the educational guidelines. These school programs are, in mostly formal codification, speeches that reflect the broad guidelines of the educational process defined by the school authorities and various specific objectives and learning situations. Moreover, these programs offer teachers many divisions and subdivisions of knowledge to pass on to students (by level, class, discipline, period, cycle, etc...). For that, teachers find a certain comfort in the use of curricula to select targets and disseminate selected knowledge based on a culture or political orientation, economic, religious or other criteria in a context of interaction with students, while using some useful working tools included in school programs such as: ministerial directives, programs, teaching guides, manuals, etc. Specifying the nature of the goals and provide the means to achieve them.

6. Provisional Conclusion

In conclusion, the singularity of the two teachers shows how the three “déjà-la” (conceptual, intentional and experiential) influence their teaching practices. Without seeking to generalize the results from two case studies, we can argue that the “decisional déjà-là” is a determinant factor in the teaching practice. Thus, the “already-there experiential” appears as the most rational dimension that offers the teachers the necessary tools to choose their teaching strategies. Like the “already-there experiential”, the “already-there concept”, shaped by the history of the subject, his beliefs and his miscellaneous professional experience, seems to be a crucial element in terms of the educational activity of the subject in influencing certain educational decisions. In the same sense, the “already-there intentional” which is the hidden part of the decision-making process refers to the causes, the reasons and motives, and partly determines teachers’ choices before, during and after the action. This is a foreshadowing of the internal didactic transposition. It refers to the order in which the teaching practices should open out.

This work also points to the multiplicity of phenomena involved in the decision making. Although it is still too early to conclude on the decision-making process, it appears that the three poles of “already-there decision” are three main bodies responsible for any decision during the teaching process ( Carnus, 2003 ). The result of this study intends to explore this “already-there decision” among our four teachers involved in the research.

References

- Altet , M. (2004). The Integration of Knowledge in Education Science Teacher Expertise: Representations and Reports to the Professional Knowledge of Teachers. In C. Lessard, M. Altet, L. Paquay, & P. Perrenoud (Eds.), Between Common Sense and Human Sciences, What Knowledge to Teach? Brussels: De Boeck.

- Bardin, L. (1998). The Content Analysis. Paris: PUF.

- Blanchard-Laville , C. (2001). The Teachers between Pleasure and Pain. Paris: PUF.

- Blaquier, J. L. (2003). The Anti-Philosophy of J. Lacan. www.Philagora.net/psychanalyse

- Carnus, M.-F. (2001). Didactic Analysis of the Decision of the EPS’s Teacher of Gymnastics Process. A Cross-Case Study. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University Paul Sabatier.

- Carnus, M.-F. (2002). Beliefs, Ideas, Intentions and Actual Practices in the Teaching of Gymnastics: The Case of ATR and tracking. In J.-F. Robin, & A. Durny (Eds.), To Actua Works.

- Carnus, M.-F. (2003). Didactic Analysis of the Decision of the Teacher of Gymnastics EPS Processes: A Case-Study. In C. Amade-Escot (Ed.), Didactics of Physical Education, State of Research (pp. 195-224). Paris: Editions Revue EPS.

- Durand, M. (1996). Teaching in Schools. Paris: PUF.

- Freud, S. (1900). The Interpretation of Dreams. Paris: PUF.

- Garnier, C., & Sauvé, L. (1999). Contribution of the Theory of Social Representations to Education on the Environment― Conditions for a Research Design for Environmental Education-Looks, Research, Reflections (pp. 65-77). Arlon: FUL.

- Giordan, A., & De Vecchi, G. (1987). The Origins of Knowledge. Neuchâtel: Delachaux and Niestlé.

- Goigoux, R. (2007). Analysis Model of the Activity of Teachers. Education and Teaching, 1, 47-70.

- Goirand, P. (1998). EPS in College and Gymnastics. Paris: NPRI.

- Jodelet, D. (1989). Social Representations. Paris: PUF.

- Loizon, D. (2004). Analysis of Judo Teaching Practices: Identification of the Knowledge Transmitted across Didactic Variables Used by Teachers for Club and EPS. Thesis under the Direction of André Terrisse, Toulouse: University Paul Sabatier.

- Loizon, D., & Carnus, M.-F. (2014). The Influence of Personal Determinants in the Choice of Teaching for PES Teachers. eJRIEPS, 33, 30-48.

- Loizon, D., Margnes, E., & Terrisse, A. (2008). Analysis of Judo Teaching Practices EPS. eJRIEPS, 14, 63-82.

- Portuguese, J. (1998). Sketching a Model of Didactic Intentions, Contribution to Mathematics Education. In J. Brown, F. Conne, R. Floris, & M. L. Schubauer-Léoni (Eds.), Didactic Interactions, Study the Work of Teaching Methods (pp. 57- 88). Acts of Seconds Didactic Days Fouly, Grenoble: The Savage Mind.

- Rochex, J.-Y. (1996). Youth Report to the Education System Today. Revue EPS, 262, 96-98.

- Terrisse, A. (2000). Epistemology of Clinical Research in Combat Sport. In A. Terrisse (Ed.), Research Combat Sports and Martial Arts (pp. 95-108). Paris: Revue EPS.

- Terrisse, A., Carnus, M.-F., & Loizon, D. (2010). The Clinic Didactic EPS: Perspectives for Training. In Mr. Musard Mr. Latch, G. Carlier (Dir), Intervention in EPS and Sports Sciences. Research Findings and Theoretical Foundations (pp. 137-158). Paris: Éditions EP.S.