Creative Education

Vol.5 No.5(2014), Article ID:45204,13 pages DOI:10.4236/ce.2014.55043

Harmonization of the Educational Sub-Systems of Cameroon: A Multicultural Perspective for Democratic Education

Valentine Banfegha Ngalim

Department of the Sciences of Education, Higher Teacher Training College, University of Bamenda, Bambili, Cameroon

Email: Valbnga2000@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 6 March 2014; revised 6 April 2014; accepted 13 April 2014

ABSTRACT

This study explains that lack of harmonization is responsible for the problems of equity and quality education in Cameroon. The objective of this paper is to inquire whether the discrepancies in achievement levels of students from the two sub-systems of education in Cameroon can be traced in lack of harmonization. To attain this objective, a mixed research method of quantitative and qualitative data collection was used to diagnose the problems of lack of harmonization in the educational sub-systems of Cameroon. Some of the problems highlighted include, lack of equity and quality education in both general and technical secondary schools. This paper therefore, exploits Dewey’s democratic theory of education, James Banks multicultural theory of education and the system theory in order to emphasize the importance of harmonization in educational development of Cameroon. A critical perspective is recommended for the process of harmonization. This emphasizes harmonization in a multicultural context. In order to produce democratic citizens for a democratic and multicultural society, a blending of values must recognize and preserve the differences that exist. That is, the experiences of learners, aptitudes and cultures must be given recognition.

Keywords:Harmonization; Multiculturalism; Democratic Education

1. Background

The history of Cameroon presents numerous interventions from European powers and these play a great role in the country’s diversity. The first contact between Cameroon and the Europeans was in the fifteenth century. These Europeans were Portuguese traders and missionaries who established bases along the coastal land (Fonlon, 1969: p. 29 in Fonkeng, 2007: p. 14). The initial name given to Cameroon at the time was “Rio dos Cameroes” a Portuguese equivalence for “river of prawns”. The British later changed this name to the Cameroons. When Germany later annexed Cameroon, the German version of the name became Kamerun. This also explains the French appellation “Cameroun” which came when the French took over from the Germans.

Cameroon fell under colonial rule in the second half of the nineteenth century during the scramble for Africa. At this time, the Germans governed Cameroon. This is precisely from the period of 1884 until the end of World War I when Germany lost the war in Europe. As a result, the allied powers took control of the German territories by employing the Mandate system. This system is derived from the tradition of the Roman Empire “Mandatum”. The principle of the Roman law Mandatum applied that someone, a mandarius (agent), could administer a territory on behalf of the owner, the Mandatum (Fonkeng, 2007: p. 16). To this effect, the colony of Germany, Kamerun was recognised as a possession of the League of Nations. Cameroon became known as a mandated territory administered by France and Britain on behalf of the League of Nations.

The consequence of this mandatory system was the formation of an Anglo-French condominium. Cameroon was therefore divided into two: that is, between the French and the British in 1918. The partition of the territory gave France control of more than two thirds of the territory. Britain acquired a small piece of the territory. The League of Nations supervised the administration of Cameroon through the permanent Mandates Commission. This League of Nations’ Mandate was later terminated in 1945 and replaced after the Second World War by the Trusteeship Council of the United Nations Organisation. As a result, Cameroon became a Trust territory of the United Nations Organisation still under the control of the British and the French administration.

On 1st January 1960, French-speaking Cameroon declared their independence from the French administered United Nation’s Trusteeship. French Cameroon was known as La Republique du Cameroun. British Cameroon became independent of the British supervised United Nation’s Trusteeship in October 1961. This part was known as West Cameroon. This led to the emergence of a Federal Republic of Cameroon. North Cameroon, the Northern British part became part of Nigeria at independence. Southern Cameroon, the English South Western highlands area chose to follow the separate course of development in French speaking regions. A decade later, on 20th May 1972, the Federal Republic was transformed into the United Republic of Cameroon. In 1984, the United Republic of Cameroon became known as the Republic of Cameroon.

In a nutshell, a historical survey of Cameroon reveals that foreign influences have played a big role in the history of Cameroon. This is evident from the League of Nations to the United Nations Organization in the former French and British Cameroons as mandated and Trusteeship territories. These events enhanced the emergence of Cameroon as the first bilingual nation in Black Africa. Today, Cameroon has ten administrative regions comprising eight Francophone regions: Far North, North, Adamawa, Centre, Littoral, Western, Eastern and Southern and two Anglophone regions in the Northwest and the Southwest. Appointed governors in addition to the divisional and sub-divisional officers administer these regions. Executive powers are conferred on the President of the Republic. The bicultural nature of Cameroon is rooted in colonial influence. Therefore, knowledge of the history of Cameroon constitutes the explanation of the two sub-systems of education.

In most African countries like Cameroon, formal education comprises different stages of development. The pre-primary, the primary, the secondary and the university are the components of formal education. In countries with one official language like Nigeria, Ghana, and Senegal and so on, there is one regular system. On the other hand, in bilingual countries like Cameroon, there are two or more sub-systems. In Cameroon, there are three sub-systems if one recognizes the Arabic system in the Adamawa and Northern regions. However, there are prominent two sub-systems, which constitute our point of focus. These include the English and the French subsystems. These two sub-systems are expected to co-exist with each jealously keeping its values. One of the educational objectives of this country is to coordinate the school programmes of the two sub-systems. This objective has not been fully implemented as a policy because of many problems associated with its conception.

2. Reasons for Lack of Harmonization

Harmonization is a term that has raised controversies in its understanding within the Cameroonian milieu. The difficulty of this term arises from the bicultural situation of Cameroon. Cameroon is a bilingual country with two colonial linguistic cultures, viz English and French. Harmonization in this case raises an ambiguous situation. Does it mean the values of one culture are made universal to the relative neglect of the other culture? Does it also imply a union of values from the two cultures to ensure a common platform for operation? These questions pose the difficulty underlying an understanding of the term. For instance, consider the process of harmonizing the legal system in Cameroon. What are the problems arising in this context which point to the difficulty of consensual understanding of the term? Though the situation of the legal system is not our focus in this paper, we think it is a source of controversy.

Many persons think that the harmonization of the educational sub-systems in Cameroon is not possible. The arguments advanced are that Cameroon is a bicultural country and it is impossible to have one system of education. This position is untenable because countries like Belgium and Canada are multicultural and bilingual respectively. At the same time, there is only one system of education in these countries. What, therefore, renders the condition of Cameroon impossible given that the cultures referred to are even alien to Cameroonians? The educational systems of Belgium and Canada are to a large extent harmonized. In these countries, two or more languages are spoken (Fonkeng, 2007). The feeble attempts to establish a harmonized system today in Cameroon is the promotion of bilingualism and competency-based pedagogy. This is also manifested in the opening of Bilingual Secondary Schools. It is interesting to note that there is nothing bilingual in these schools. It is merely a juxtaposition of students from the English and French speaking backgrounds.

There are many obstacles to the policy of harmonization. These include; bicultural nature of Cameroon, misconceptions of the term, pedagogic considerations and weak political will which make policies incapable of being transformed into action. Firstly, one major barrier to harmonization is the bicultural nature of the country owing to colonial heritage. The argument goes that Cameroon is a bilingual country where two cultures must coexist (Tchombe, 1999). These cultures are said to exist in all spheres of life including education. For this reason, each culture jealously seeks to preserve its values and colonial heritage. None of them, neither the English nor the French sub-system of education wants to compromise their educational values for the sake of a harmonious system of education. The need to preserve each cultural heritage complicates the process towards harmonization. However, this is very frustrating because there is a misconception of harmonization.

Secondly, the process of harmonizing the educational sub-systems in Cameroon has been misconstrued. This process has been conceived as assimilation (Fonkeng, 2007: p. 299). By assimilation, one refers to the process of one culture integrating the other and consequently rendering it extinct. This conception frustrates the process and explains the reason for each culture wanting to jealously keep its values without any compromise. The need for diversity in Cameroon cannot simply be maintained without critical observations of its merits for the development of the country. It is still possible for Cameroon to maintain a bicultural educational alternative with a common school curriculum as in other bilingual and multilingual countries like Canada and Belgium respectively. It is unity in diversity. Godfrey Tangwa holds that objective reality is multi-coloured (2011). To perceive the educational system of Cameroon from this perspective, one can therefore argue that diversity in the systems enhances educational development. It is acceptable to entertain diversity and different viewpoints as prescribed by multiculturalism and democratic education. At the same time, the different colours are diverse accidents that require a basic substratum on which to subsist. Accidents have their existence and perception by subsisting in a substance. In the educational context in Cameroon, there must be a common ground which every sub-system has to forge ahead in its diverse characteristics. In spite of the many changes and varieties that arise, there is a basic reality beneath all those changes. This is the context in which harmonization of the sub-systems of education is thought of.

Thirdly, the absence of a political will renders the process of harmonization theoretical. A major contemporary objective of education in Cameroon is the harmonization of the sub-systems. The result of this process entails a common curriculum leading to uniform syllabuses and schemes of work. This educational politics has not yet attained its objectives even in basic education where the number of years for learning has been harmonized. The number of years is the same in the secondary schools but the two sub-systems are not having a common curriculum. Harmonization in educational politics entails the same curriculum, elaborated in the syllabuses and schemes of work in the two official languages (Fonkeng, 2007; Tchombe, 1999). This has to be done from the pre-primary, primary, secondary and high schools. With harmonization, the problem of equity and quality hardly arise. Education is about fairness; therefore, all citizens in the same country should be given equal opportunities of learning and development to ensure national integration.

Another problem in the organization and lack of harmony in the curricula can be traced in Pedagogic discrepancies. The syllabus for History in the Francophone sub-system is distinct from the syllabus of History in the Anglophone sub-system in both depth and breath. This former sub-system limits itself with foreign History and little or no attention is given to Cameroon History. Multicultural education insists on the need of the subject matter to be founded on the interests of the learners. The learners are citizens in Cameroon who have to study their past and present experiences in order to prepare for the future. The problems of educational alienation and indoctrination arise in the syllabus of History in the Francophone sub-system. In the English sub-system, History and Geography are two distinct subjects to be studied. On the contrary, in the Francophone sub-system, the two subjects are combined and popularly described as “Histoire-geo”.

Moreover, differences in the examination systems at the secondary school level in particular serve as a barrier to the policy of harmonization. While the students in the English sub-system have a single subject certificate system, those from the French sub-system have a group certificate system. In the second cycle, for example, the former has different series of specialization (Arts, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and Science, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5,). The highest number of subjects a candidate can take in the final year examinations in this sub-system is five. This is for the sake of an in-depth study accompanied with practice as in the case of the sciences. On the other hand, the syllabus of the latter is wider in terms of the number of subjects (Baccalaureates A and B and Baccalaureates C and D and about twelve subjects for science students). This compromises profundity in some areas of specialization. Harmonization of the two sub-systems is limited to structural aspects in terms of the duration of the courses. At the level of the primary, both sub-systems begin with Nursery education lasting for a period of two years. This is done between the age intervals of four to six years. Afterwards, primary education is done for six years. The present six years is indicative of the reduction of one year for the Anglophone sub-system prior to the 2006/ 2007 academic year.

At the level of secondary education our point of focus, the duration of courses for both sub-systems is seven years. However, the structures differ with the two cycles involved in the two sub-systems. The first cycle has an observation sub-cycle of two years with a common core syllabus and an orientation sub-cycle of three years of general or technical education following 1963 Law (Tchombe, 1999: p. 16). The second cycle is two years for both general and technical education. Here, there is no focus on the Probatoire. In fact, the French sub-system differs from the English sub-system in structural organization. While the former has a period of four years course for the first cycle prior to Brevet d’Etude du Premier Cycle, the latter has a period of five years prior to General Certificate of Education/Ordinary Level. Also, while the French sub-system has three years for the second cycle with two public examinations, Probatoire and Baccalaureate, the English sub-system has two years with one public examination, General Certificate of Education/Advanced Level. This is the same case for technical education. But a candidate who writes the Certificat d’Aptitude Professionelle, Probatoire and Baccalaureate follows the structure of the French sub-system and one who writes the General Certificate of Education in technical education follows the structure of the English sub-system. These discrepancies may be taken for granted, but they communicate something of pedagogic significance. For instance, the syllabus coverage and the level of profundity before completion is a question of quality education. What is interesting to note is that some English speaking students in technical education are daring to write the two examinations from the two subsystems at the same time. Part of the explanation lies in the uncertainty of the outcome of the results. There is some confusion in the management of the whole process of writing two different examinations at the same time. After writing a subject in Baccalaureate technique, a student proceeds to write another paper in the technical General Certificate of Education (GCE) in Advanced Level. In some courses, they come late and sit in to write while other students have already finished writing. It becomes questionable whether this is an acceptable conduct in running a public examination (Focus group discussion with students writing Technical GCE, Government Technical High School Kumbo, 30/05/2013).

Furthermore, the existence of two examination boards compromises a common vision expressed in the policy of harmonization. The end of course and common entrance examinations is centrally organized by the Ministry of National Education with the GCE Board for the Anglophone examinations and the Baccalaureate Board for the Francophone Examinations. The critical concern here is the criteria for making decisions by the distinct examination bodies. At the moment, there are pilot schools preparing students to sit for the examinations of the two boards at both cycles. It is imperative to question the objective of this experiment. Is it a step towards harmonization? From the problems highlighted with regard to lack of harmonization in the curricula of the two subsystems, the problem of equity in the educational system in Cameroon is evident. The learners do not have equal access to some educational values. At the same time, there are many foreign languages like German and Spanish in the francophone sub-system. These languages do not exist in the Anglophone sub-system and deprives them of all privileges associated with these languages. This reveals the problems underlying the question of fairness and quality education, which constitute the requirements for multicultural education in a democratic society.

However, the vision of the country contrasts the organization of the curricula in Cameroon. In spite of the bicultural nature of the country, the present politics is that of unity and national integration. This expresses the need for all Cameroonians to live and feel as one and to have a common destination. For the country to attain these objectives there is a need to establish an enabling environment, which will help Cameroonians perceive themselves as one. This condition therefore justifies the need for a common curriculum leading Cameroonians to a common destiny. With the conflicting values from a bicultural system as indicated above, harmonization, which is a synthesis of the dialectic of values stands as a means of releasing Cameroon from some educational problems like the absence of fairness, poor quality education and some deficient democratic educational values. The problem of harmonizing the two sub-systems is real. The powers that be stand to allow each system operate independent. This can only be effective if both sub-systems are accorded the same value, privileges and status (Tchombe, 1999: p. 16).

3. Research Question

Can lack of harmonization explain the problems of quality and equity in the educational system of Cameroon? This research question has a twofold articulation;

Do the discrepancies in the achievement levels of students in the two sub-systems betray problems of lack of harmonization?

Are problems of student mobility from one sub-system to another traced in lack of harmonization?

4. Hypothesis

This paper sets out to argue that lack of harmonization explains the problems of equity and quality education in the educational system of Cameroon. These problems carry a twofold expression. Firstly the discrepancies in the achievement levels of students from the different sub-systems. Secondly, the mobility of students from one subsystem to another creates problems of determining the standard and level to be considered.

5. Theoretical Framework

In order to resolve the problem of harmonization in the Cameroonian school system, this paper identified three main theories. These include the Deweyan democratic theory of education, the multicultural theory of James Banks and the system theory. John Dewey considers education as a process of life through which an individual continuously adapts to the innovations and vicissitudes of his environment. This Deweyan truism is timeless and universal. This does not exclude the educational system of Cameroon at the moment. The Curriculum is the “instrumentum laboris” (working document) that each educational system employs to attain the objective of helping the learners in the process of growth. For this precise reason, the organization of the curriculum in Cameroon educational system is the means through which the socio-political and economic objectives and values of the state can be attained. Dewey reiterates that:

I believe that school is primarily a social institution. Education being a social process, the school is simply that form of community life in which all these agencies are concentrated that will be most effective in bringing the child to share in the inherited resources of the race, and to use his own powers for social ends (…) I believe that education, therefore is a process of living and not a preparation for future filling (Dewey, 1897, in Dworkin, 1972: p. 22).

The Deweyan intuition above defines the relationship between Cameroonians and the secondary schools. Schools are extensions of the community in Cameroon. Said differently, the school is a microcosm of Cameroon. Life in school is a reflection of the society in which the child lives and grows. Dewey’s position here is that the school shares in the burden of caring for the children of the community. It equips them with skills and habits necessary to survive and succeed. It is the place of the school, with the help of the curriculum, to translate the highest ideals of the community into academic and social programmes for all children. As Dewey says, “What the best and wisest parent wants for his own child the community wants for all children (Dworkin, 1972: p. 54). Democratic education refers to an educational approach which ensures that all learners have equal access to learning opportunities and privileges irrespective of age, sex, region, race, tribe, religion, country and colour. Democratic education and equity refer to fairness in the provision of educational facilities and values (Dewey, 1966: p. 81). In the Cameroonian context, being an Anglophone or a Francophone does not justify any negligence in the provision of learning values or facilities. Equity refers to the provision of equal access and opportunities to all learners irrespective of socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. Equity frowns on all forms of discrimination. The socio-economic, cultural and political causes of lack of equity are to be traced in order to limit it from education (Nelson, Palonsky, & McCarthy, 2006: p. 81). The presence of equity is what ensures democratic education in a multicultural context like Cameroon.

This paper limits itself within Deweyan pedagogy of interest in democratic education. This theory explains the problem of equity and quality education in the educational achievements in the Cameroonian society. Lack of harmonization affects equity pedagogy, which is a major characteristic in multicultural and democratic education alternatives. By equity pedagogy, all learners are given equal opportunities and privileges to develop their potentials. The teaching and evaluation procedures are established to foster the aptitudes, needs and experiences of learners (Dewey, 1966; Nelson, Palonsky, & McCarthy, 2006). Quality education is also determined from the fact that the learners acquire the necessary skills to enhance their full integration into the community. Within this framework, quality education is possible if the curricula in Cameroon enhance the acquisition of the basic achievement levels of all students in the various specializations. This fact is possible with a harmonized curriculum even if these educational values are transmitted within the processes and procedures of the respective cultures.

Another prominent theory in this study is the multicultural education theory. The values of multiculturalism are not very distinct from democratic education. This educational alternative also advocates equity and quality education in the organization of the curricula of the two sub-systems of education in Cameroon. To be more preciseMulticulturalism is a reform movement designed to restructure educational institutions so that all students, including white, male and middleclass students, will acquire the knowledge skills, and attitudes needed to function effectively in culturally and ethnically diverse nation and world (…). Multicultural education (…) is not an ethnic or gender specific movement, but a movement designed to empower all students to become knowledgeable, caring and active citizens (…) (Appiah, 2000: p. 291).

James Banks defines multiculturalism as an educational alternative and strategy, which recognizes and attempts to reform the inequalities that exist in educational theory and practice (2001). Parker explains that the central purpose of multicultural education is “to improve race relations and to help all students acquire the knowledge, attitudes and skills needed to participate in cross-cultural interactions and in personal, social and civic action that will make our nation more democratic and just” (2003: p. 1). In the context of this paper, multicultural education is a form of democratic citizenship education that recognizes plurality of Cameroon and attempts to bring historically marginalized groups to the forefront of public education in order to develop active democratic citizens. Multicultural education fosters citizenship education, and attempts to connect the concepts of “Pluribus ad Unum (unity in diversity) to create inclusive, equitable and just Cameroon. Multicultural education is not just for individuals that characterize diverse backgrounds (Banks, 2002). However, it is citizenship education for everyone. This leads us to the democratic conception of education in a pluralistic society.

Lastly, a system theory was used to explain the inter-connectedness of all parts of the two cultures in Cameroon. The two sub-systems are parts of a whole, which is the educational system in Cameroon. Any problem in one of the sub-systems affects the whole educational system. The pedagogic problems encountered by the English sub-system of education in Cameroon are not only detrimental to the well-being of the English speaking Cameroonians. It affects the whole system because this sub-system is meant to provide democratic citizens for a harmonious functioning in the state. The same situation holds for the problems identified in the French sub-system of education. Therefore, it is imperative to establish a system that functions harmoniously. Each part has to play its proper function. This is to ensure the well-being of the whole system.

6. Conceptual Framework

To begin with, harmonization is a noun derived from the verb to harmonize. It is both a transitive and intransitive verb meaning to blend pleasingly or to make things combine pleasingly. As a transitive verb, it has to make the school sub-systems agree, make rules, regulations or systems similar or in accord to each other. As a transitive verb, one gives examples as; he adds harmony to melody. He provides harmony to a melody. As an intransitive verb, one can talk of playing in harmony, that is, to sing or play musical instruments in harmony (Hornsby, 2000). It is used in the context of our study to mean a blend or a synthesis of commendable values for a way forward in educational theory and practice in Cameroon. Fonkeng Epah George explains the concept of harmonization in the educational context as a coordination of programmes from the primary, secondary and tertiary levels (2007: p. 298). The coordination of the school programmes from the French sub-system and the English sub-system leads to a strong and unique system with common certification and examinations. It is used in the context of our study to mean a blend or a synthesis of commendable values for a way forward in educational theory and practice in Cameroon. Synthesis here refers to the gradual progress from thesis to antithesis. This conception does not contradict what Fonkeng refers to as a coordination of school programmes.

Also, Therese Mungah Tchombe explains this concept in the sense of coordinating school programmes (1999). At the same time, she argues that this does not degenerate to a monolithic system. This strategy to blend the educational practices of Francophones and Anglophones does not necessarily mean the creation of a monolithic system (Tchombe, 1999: p. 7). Harmonization entails that certain aspects of the curricula or syllabi of the two sub-systems at the primary and secondary levels should have the same contents. These contents may be taught in conformity with methods and procedures of each of the existing sub-systems. The assumption that underlies harmonization is that the contents taught in the two sub-systems are universal. The standard will be maintained irrespective of the medium of instruction (Tchombe, 1999: p. 7).

The programmes are the same but the two sub-systems maintain their autonomy in terms of the language of instruction. From the opinions given as regards harmonization, this study maintains a synthesis of values in the Hegelian sense. Here, the coordination of school programmes comes with time. It must be subjected to the processes of dialogue and exchange of opinions. The argument of maintaining the dialectic conception of harmonisation is that it emphasizes the place of dialogue. Fonkeng observes that this conception does not contradict the coordination of school programmes (2007). However, our study wants to complement the conception of coordination with the element of dialogue. Harmonization refers to the process of reconciling the conflicting values of the two sub-systems of education in Cameroon. The dialectic of curricular organization proposes a progress from the thesis to antithesis and thus synthesis. This synthesis is also found in the attainment of full inclusive education. Prior to this stage, there was exclusion, separation and limited inclusion. Lack of harmonization is a problem of curricular organisation in Cameroon secondary education. One finds the need for a synthesis or a reconciliation of progressive educational values for a strong and unified curriculum that gives everybody equal access to learning opportunities and privileges (Dewey, 1966: p. 99).

7. Methodology of Study

There are two approaches of research in this study. These include: the quantitative and qualitative methods of research. The reason for these two methods lies in the fact that the weaknesses of one approach should be complemented by the strength of the other. The idea is that one can be more confident with a result if different methods lead to the same result. By combining multiple observers, theories, methods, and empirical materials, researchers can hope to overcome the weaknesses or intrinsic biases and the problems that come from single method, single-observer and single-theory studies (Gay, 1996; Akuezuilo, 2002). Triangulation is a powerful technique that facilitates validation of data through cross verification from two or more sources. In particular, it refers to the application and combination of several research methodologies in the study of the same phenomenon (Gay, 1996). For this quantitative method, the instrument was a questionnaire. The construction of a questionnaire was based on the main theme in the research question. These were questions on equity pedagogy and quality education in the context of harmonization. Five hundred questionnaires were sent out to the two sampled regions and the return rate was 80%. For qualitative approach, the instruments were interview and focus group discussion guides for collecting data.

A pilot test of twenty answered questionnaires was carried out to test the validity of the main research instrument, the questionnaire. The pilot test proved that the instrument was reliable. It had the score of 0.76 indicating the consistency of the responses. This test also helped to modify some of the questions to avoid ambiguity. The sample regions for collection of data included the Centre and North-West regions representing the French and English speaking regions of the country respectively. The target population included University professors and lecturers, pedagogic inspectors, teachers, students and student teachers in secondary schools and Higher Teacher Training Colleges for both general and technical education. The data collected was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 17). The hypothesis was tested and the results obtained affirmed the alternative hypothesis and the null hypothesis rejected.

8. Presentation of Findings

There are two aspects justifying lack of harmonization in the curricula of the two sub-systems of education in Cameroon. These include the differences in the achievement levels in the two sub-systems and fear of falling standards as regards the mobility of students from one sub-system to another.

8.1. Different Achievement Levels of Students in the Two Sub-Systems

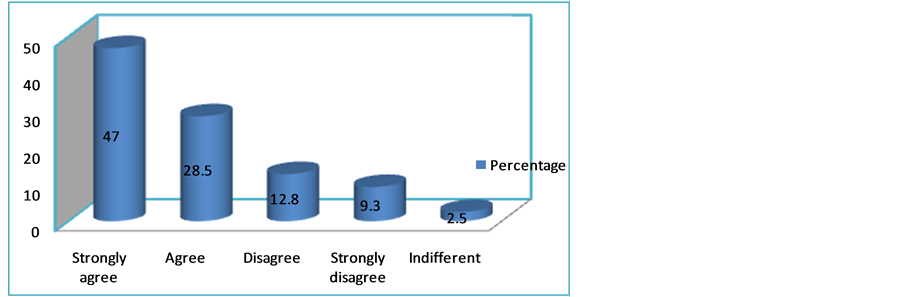

In Table 1 below, there is an expression of opinions as regards the basic achievement levels of secondary school leavers in the two sub-systems of education in Cameroon. An achievement level refers to the basic knowledge and skills a secondary school leaver possesses at the time of graduation (Akuezuilo, 2002: p. 83). Considering 400 respondents who reacted, 188 of them strongly agree and 144 simply agree that there are differences in the minimum achievement levels of the students in the two sub-systems of education. This implies that 47% of the respondents strongly agree and 28.5% simply agrees. Therefore, the total number of respondents who affirm the differences in achievement level is 75.5%.

On the other hand, 51 respondents disagree with the proposition and 37 of them strongly disagree. This amounts to the sum of 88 respondents, thus 22% of persons who say that there are no differences in the basic achievement levels of secondary school leavers in the two sub-systems of education. 10 respondents remain indifferent which gives the score of 2.5% as seen in Table 1 and Figure 1. Consequently, the gap between those who affirm the difference and those who disagree is wide. From the results obtained, there is a high probability that secondary school students from the respective sub-systems of education in Cameroon complete school with different achievement levels. These differences can be explained by the fact that there are discrepancies in the curricular contents, objectives, methods of teaching, textbooks, didactic materials and evaluation procedures and processes in the two sub-systems of education in Cameroon.

In the same context, generally, the differences in achievement levels are also portrayed in the academic performance of the students from the two sub-systems in Higher education. From our interviews and focus group discussions, we learn that students from the Francophone sub-system of education consistently outperform those from the Anglophone sub-system of education in Mathematics, Physics and other fields of studies requiring Mathematical competence. Also, students from the Anglophone sub-system of education outperform their Francophone counterparts in Chemistry, Biology and Geology. Also, Francophones complete secondary education with a linguistic competence in either Spanish or German. Presently, there is Chinese in some schools in their sub-system. None of these values is present in the schools of the Anglophone sub-system.

Table 1. Distribution of opinions on the different achievement levels of students in the two sub-systems as a result of lack of harmonization.

Figure 1. Percentage distribution of opinions on the different achievement levels of students in the two sub-systems.

The differences confirmed by the examples above justify the problem of equity and quality in the educational system of Cameroon. In this way, the urgent need for harmonization of the curricula is visible. One cannot acknowledge educational equity and quality education in a country where different citizens acquire different educational values in different degrees. The justification for this position lies in the problems and complaints faced by students in higher education. These problems are visible in competitive examinations. In these exams, emphasis laid on the syllabus of one sub-system as opposed to that of the other limits the chances of those whose syllabus has not been the reference. Therefore, harmonization of educational values is imperative if equity and quality education are commendable.

8.2. Fear of Credible Standards as Regards Mobility of Students from One Sub-System to Another

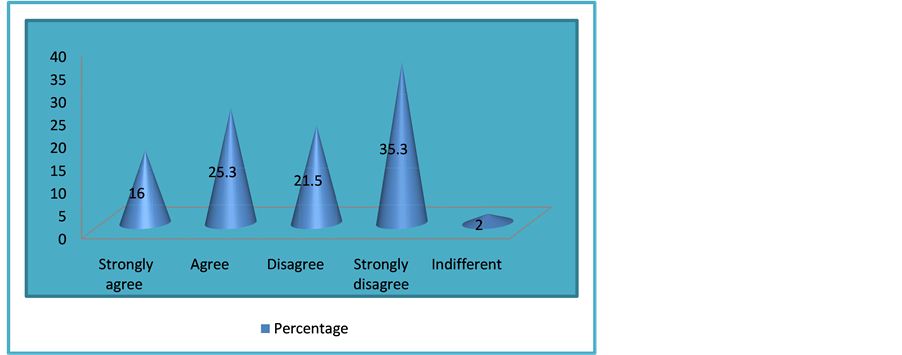

In Table 2, opinions on the mobility of students in two sub-systems of education are represented. Following the results, 64 respondents strongly agree. Therefore, 16% of the respondents strongly agree that the mobility of students in the schools of the two sub-systems of education is possible. It is possible because there is no fear of incredible educational standards. In Table 2, 101 respondents agree, which give 25.3% as presented in Figure 2. On the contrary, 86 respondents, which represent 21.5% disagree with the proposition and 141, which make 35.3% strongly disagree. Only 8 respondents, 2.0% remain indifferent.

Considering these results, 165 respondents affirm that the mobility of students in the two sub-systems is possible. This is opposed to 227 respondents who disagree with the proposition. The gap between those who affirm and those who disagree with the proposition is 62 respondents. This difference between those who affirm the proposition and those who negate it is wide. There is an affirmation that moving from one sub-system of education to another probably causes academic problems. There is a possibility of experiencing falling standards in one domain as opposed to the other. This betrays a fluctuating educational experience in secondary education context in Cameroon.

The outcome of this analysis is that a synthesis of values in the name of harmonization is imperative. Harmonization is a means through which a common vision in the curicula of the two sub-systems can be promoted. With a common curriculum in the two sub-systems, student mobility causes little or no problem. Harmonization serves as a means to enhance the process of bilingualism in the country. The movement of families from one part of the country to another hardly prevents the educational progress of children. In every part of the country

Table 2. Distribution of opinions on fear of credible standards as regards students’ mobility in the two sub-systems.

Figure 2. Percentage distribution of opinions on fear of credible standards as regards students’ mobility in the two sub-systems of education.

there is going to be educational facilities that facilitate the child’s integration into the school system. This is done irrespective of the language of instruction. Therefore, these results strongly justify the need for harmonization.

8.3. Test of Hypothesis

In Table 3, the Chi Square probability is 0.000. This is less than 0.01 or (1%). This result negates the null hypothesis that harmonization and different achievement levels of students in the two sub-systems are independent. There is therefore a relation between the two variables, harmonization and the achievement levels of students in the two sub-systems. The discrepancies in question justify lack of harmonization. The differences in the achievement levels of students in the sub-systems portray problems of equity and quality education. For this reason, the urgency of harmonization cannot be over-emphasized.

The results obtained as regards the hypothesis reveal that lack of harmonization in the two sub-systems of education justifies problems of equity and quality in the educational system of Cameroon. Problems of equity and quality education range from the gab in achievement levels for graduates in the two school sub-systems, differences in subject contents, differences in subjects and years of study. These facts affirm the hypothesis, which holds that lack of harmonization in the educational system can be explained by problems of equity and quality in the curricula of the two sub-systems of education in Cameroon.

9. Discussions

There are several educational problems that accrue from lack of harmonization in the educational sub-systems in Cameroon. The need to harmonize the educational sub-systems has become more evident as Cameroon faces up to changes in society and the world. It ensures a strong equity pedagogy and quality assurance teaching capacity. Also, it reduces the achievement levels of students from the two sub-systems and creates an atmosphere of peace and good citizenship in Cameroon.

Firstly, harmonization enhances equity pedagogy in the educational system of Cameroon. Equity pedagogy is a dimension of multicultural education, which organizes teachers to ensure the academic success of students irrespective of sub-systems, tribes, religions, languages, sex or regions (Banks, 2002). This strategy is attained with a task force that examine and compare the performance of students from the two sub-systems in the various areas of study. Reconsider the case of technical education. There is the problem of evaluation in Technical examinations. The CAP, Probatoire and Baccalaureate are different examinations in the context of technical edu

Table 3. Association between harmonization and the different achievement levels of the sub-systems.

a1 cells (6.3%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 4.67.

cation. The French sub-system has been dominating technical education in evaluation. It is due to the problems encountered by the many Anglophone candidates that the GCE Board also introduced Technical GCE exams for interested candidates. The previous French sub-system of evaluation viz; CAP, Probatoire and Baccalaureat explains numerous school dropouts from technical institutions. In the Anglophone part of Cameroon, technical secondary education has not been greatly promoted. Unfortunately, it has always been considered as a second-class type of education for academically-weak persons. This mentality coupled with problems of evaluation has been influential in shaping the children’s disposition to secondary technical education. A harmonized system provides a high-level task force with a central system. This force serves as an aid to study the situation of the central system thus minimising entrenched tribal, cultural, linguistic as well as regional interests. One may argue that a decentralized system facilitates administration. The educational system of any country has to provide equal access and opportunities to all persons pursuing education. In this context, only a harmonized educational curriculum rather than an assimilated one, like the case in Cameroon, can bring equal educational standards within the framework of multiculturalism and democratic education.

Secondly, harmonisation facilitates values of multicultural education like teamwork, exchanges and sharing of teaching experiences. The practice of working in teams is prevalent in all types of organizations in the world today. Inter-departmental teams are formed to engage workers on collaborative efforts to resolve problems, integrate new programs, processes and engage in long-range planning (Nelson, Palonsky, & McCarthy, 2006). These experiences are rare in the present Cameroonian school sub-systems. Part of the reason could be traced in lack of a central system to ensure the realization of progressive ideas in schools. In order to bring together all stakeholders in an organization, interdisciplinary and cross-functional teams are formed. This is in an attempt to improve communication, increase involvement, improve quality and efficiency and increase productivity. Pedagogic forums for teachers provide a platform for exchanges amongst teachers. This approach refers to cooperative learning which has the merit of bringing people together to work. Also, getting students to work together, to listen to every member, to consider all view points and to exercise courtesy and respect for each other are challenges from multiculturalism and democratic education (Fonkoua, 2007). The reason behind these challenges lies in the cultural beliefs, attitudes and practices that influence communication styles. This condition requests an organized system where educators can have training on the strategies to prepare students for future interactions in a culturally diverse background like Cameroon. Harmonization provides a forum that brings teachers from the two sub-systems to share and exchange teaching values. This strategy leads to the reduction of prejudices (Banks, 2001). Teachers acquire values that help them to use materials and different methods to modify students’ attitudes. This is an approach that leads to tolerance, recognition and acceptance of the differences in cultures and understanding. This is the merit of teamwork in multicultural education (Nelson, Palonsky, & McCarthy, 2006).

Thirdly, harmonization ensures fairness in the provision of educational facilities and privileges. This is seen in multicultural education perspectives. Secondary schools are not seen as treating students with equality. The question of fairness in the educational system in Cameroon is a sensitive issue because most schools are responsible for educational inequalities. The underlying question is whether the cause for inequalities is political, economic or socio-cultural. This problem stems from the distribution of educational assets in the various regions of the country. The respect for human rights must be primordial in determining this distribution rather than political or economic ambitions. Democratic education emphasizes equal access of all persons to quality education. This does not refer to the same subject matter and content of education, but educational facilities that enhance the aptitude and interests of all persons (Dewey, 1966: 81).

Besides, educational infrastructure is not limited to school buildings but extends to teaching facilities like different teaching laboratories that respond to the needs of modern times. For instance, New Information Technology is no longer a novelty in schools. The demands of education require that all schools should afford to impart basic skills of Information and Communication Technology (ICTS) in the learners. This requirement poses a problem of equity in the democratization process of education in Cameroon. Less than half of secondary schools are fully engaged in the teaching and practice of ICTs. There are many conditions associated to this problem. It is not only the availability of computers, but also the facilities that go along with these appliances. Fairness in education cannot be attained if teachers do not possess the basic skills required for research and teaching. The introduction of new technology in education is not narrowed to audio-visual aids. It includes the use of the computer and other information tools. Unfortunately, the training of teachers has not laid emphasis on this aspect of teacher formation. The inevitable effect is that there are many teachers who do not employ these facilities for research.

10. Conclusion and Recommendations

This paper is set out to study the process of harmonization in the educational system in Cameroon from the perspective of multicultural education. This educational alternative promotes democratic values in Cameroon especially in the context where there are educational problems related to equity and quality education. Multicultural education in Cameroon advocates values that unite Cameroonians and those that portray their diversity, and ancestral roots. For the process of harmonization to be democratic, it has to go beyond the politics of simply recognizing the bicultural nature of the educational system. The need for harmonization introduces the politics of redistribution. This perspective brings forth the debate of educational equity as a means of enhancing peace and good citizenship in Cameroon. Education has an a priori objective of facilitating life in the community. For there to be unity and peace amongst people, there must be social structures that preserve these values. A culture of peace consists in values, habits and behavioural patterns that reflect and favour a life of sharing in freedom, justice and democracy, human rights and the spirit of tolerance. These attitudes prevent conflicts and aim at resolving problems through dialogue and negotiation (Fonkoua, 2007: p. 253). This means that good education has the objective of promoting democratic citizenship. The school curricula in Cameroon aim at enforcing peace and unity. This is attained by helping each Cameroonian to develop his potential for full participation in the life of the community.

The problem in this paper has been to prove that the problems of equity and quality education in Cameroon are associated to the lack of harmonization in the educational sub-systems. The perspectives to resolve this problem requires a critical attention. For the spirit of unity to be established, there is a need for dialectic of values in the two sub-systems of education. In order to establish a synthesis with commendable and admirable values for the two sub-systems of education for all Cameroonian citizens, there is a necessity to encourage collaboration and exchange of values in the two sub-systems. The justification for the reconciliation of the syllabi, examination and educational structure includes a common platform for the creation of a national curriculum and coherence in the educational system.

This study recommends harmonization in its context of preserving cultural patrimony as an objective of multicultural education. Cultural patrimony refers to the sum total of ways of living, including values, beliefs, aesthetic standards, linguistic expression, and patterns of thinking, behavioural norms and styles of communication, which a group of people has developed to assure its survival in a particular physical and human environment (Mvesso, 2005: p. 88). The educational system of a nation stands as the most appropriate means for the preservation of cultural values. Cameroon is often referred to as Africa in miniature. This conception portrays that the educational system requires a curriculum which is Cameroonian. Cameroon is characterized by diversity, which goes beyond the bicultural nature of its educational system. There are more than two hundred and thirty ethnic groups in Cameroon. This reflects the society where Cameroonian students live and grow. With the multiplicity of ethnic groups and their diverse cultural values, Cameroonian schools have to organize their structures to accommodate inter-cultural diversity in the spirit of unity. Therefore, the school is expected to enhance inter-cultural dialogue towards tolerance in diverse cultures. This is the context in which harmonization of the sub-systems of education in Cameroon is acceptable.

References

- Akuezuilo, E. O. (2002). Research and Statistics in Educating and Social Sciences: Methods and Applications. Akwa: Academic Press Ltd.

- Appiah, K. A. (2000). Culture, Subculture, Multiculturalism: Educational Options. In E. M. Durate, & S. Smith (Eds.), Foundational Perspective Education. New York: Longman.

- Banks, J. A. (2001). Cultural Diversity and Education: Foundations, Curriculum and Teaching. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Banks, J. A. (2002). An Introduction to Multicultural Education (3rd ed.) Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Dewey, J. (1966). Democracy and Education. An Introduction to Philosophy of Education. New York: Free Paper Press.

- Dworkin, M. S. (1972). Dewey in Education. New York: Delta Publishing.

- Fonkeng, G. E. (2007). The History of Education in Cameroon: 1884-2004. Queenstown Lampester, New York: The Edwin Mellen Press.

- Fonkoua, P. et al. (2007). Elements d’education a la morale et a la citoyennete au Cameroun. Rocare Cameroun: Editions Terroirs.

- Gay, L. R. (1996). Education Research: Competencies and Applications. USA: Prentice-All Inc.

- Hornsby, A. S. (2000). Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mvesso, A. (2005). Pour une nouvelle education au Cameroun; Les fondements d’une ecole citoyen du developpement. Yaounde: Presses Universitaire de Yaounde.

- Nelson, J. L., Palonsky, S. B., & McCarthy, M. R. (2006). Critical Issues in Education: Dialogue and Dialectics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Parker, P. (2003). Teaching Democracy: Unity and Diversity in Public Life. New York: Teachers’ College.

- Tangwa, G. (2011). Ethics in African Education. In A. B. Nsamenang, & T. M. Tchombe (Eds.), Handbook of African Educational Theories & Practices: A Generative Teacher Education Curriculum (pp. 91-106). Bamenda: Presses Universitaire d’Afrique.

- Tchombe, M. T. (1999). Structural Reforms in Education in Cameroon. http://www.educationdev.net/educationdev/Docs/Cameroon.PDF