Creative Education

Vol.5 No.4(2014), Article ID:43651,12 pages DOI:10.4236/ce.2014.54028

Exploring Transactional Analysis in Relation to Post-Graduate Supervision—A Balancing Process

Patrik Thollander1*, Wiktoria Glad2, Patrik Rohdin1

1Department of Management and Engineering, Division of Energy Systems, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

2Linköping, Sweden Department of Thematic Studies—Technology and Social Change, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

Email: *Patrik.thollander@liu.se

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 13 December 2013; revised 13 January 2014; accepted 20 January 2014

ABSTRACT

The PhD student supervision process is an important process, and the need for PhD students, who often form the backbone of the research community, to receive professional, inspiring and efficient supervision cannot be understated. This paper explores the benefits and values of Transactional Analysis (TA) as a way to further understand and work with PhD supervision. Using TA and the legitimacy ladder applied on PhD education, a modified model for increased understanding of the PhD student supervision process is presented, and is then related to empirical findings from a questionnaire among PhD students. The model shows for example the need for the supervisor to balance his or her role towards the PhD student, and suggests that professional PhD student supervision means moving from a Parent to Child relationship between the supervisor and the PhD student, towards a more mature Adult to Adult relationship.

Keywords:PhD Student Supervision Process; Transactional Analysis; The Legitimacy Ladder; Supervision Model

1. Introduction

Supervision is often referred to as one of the most important factors for a well-functioning research community (Halse & Malfroy, 2010; Pearson & Kayrooz, 2004; Mainhard et al., 2009; Watts, 2009; Delamont et al., 1998; Deuchar, 2008), while it can also be regarded as one of the most responsible (Armstrong, 2004). In Degerblad and Hagglund (2001) the authors addressed the Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (HV)’s view of the criteria in the evaluation of post-graduate studies. Their study presents a more comprehensive list of criteria for what constitutes a functioning research environment and these criteria should be interpreted as minimum criteria for a well-functioning post-graduate environment (Degerblad & Hagglund, 2001). These general criteria are (1) the economic and infrastructural conditions, (2) student recruitment, which places demands on those who step into the activities in terms of motivation to demands for an adequate basic knowledge and (3) teacher recruitment, protection of high scientific and teaching skills (Degerblad & Hagglund, 2001). When the activity in the post-graduate program is in addition to subject-specific quality criteria, a number of general requirements of from HV include (1) subject depth, (2) interdisciplinary, (3) related to research activity, (4) qualified supervision, (5) scientific cooperation, and (6) the existence of a creative environment. Beyond this, also the formal requirements for the delivery of education in the form of graduated doctors and producing papers and publications (Degerblad & Hagglund, 2001). It is in this context that graduate supervision is a part, i.e. a balance between the organizational, economic and social factors (Delamont et al., 1998; Watts, 2009).

As the supervision process has been shown to be a key component of a well-functioning research community, one can ask questions about what well-functioning supervision and the factors affecting this process look like. In the scientific literature, methods, theories and possibilities to structure and clarify the supervision, such as guidance as a supervisor (Manathunga, 2007), supervision related to the cognitive style used (Armstrong, 2004; Deuchar, 2008; Halse & Malfroy, 2010; Baker & Lattuca, 2010), all of which span the theoretical models of how PhD student supervision can be theorized and understood. These authors all point out in one sense that supervision is a complex phenomenon and as Manathunga and Goozée (2007) point out, one is not an effective and complete supervisor just because you yourself have been supervised.

The PhD student supervision process is thus a complex process and supervision and supervisors of higher quality have become increasingly important when it comes to post-graduate education (Halse 2010; Deuchar, 2008; Watts, 2009; Delamont et al., 1998). In Sweden, the importance of PhD student supervision began to be accentuated in the early 1980s (Bjurmark, 2011). The need for PhD students, who often form the backbone of the research community, and in particular the university part of the scientific community, to be given professional supervision, cannot be understated. A study by the Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (2003) found that one of the most common reasons why 67% of the female and 56% of the male PhD students had considered quitting their education was problems in the supervisor-PhD student relationship. Theory developing, experience sharing, and empirical studies to improve knowledge and create better structures in this highly complex area, PhD student supervision, are thus of great importance, not least with regard to the actual relationship between the supervisor and the PhD student, as outlined above.

Transactional Analysis (TA), derived from the psychiatry field and founded by psychiatrist Eric Berne, has since Berne’s introduction of the theory in 1964, spread widely among various research disciplines (Berne, 1964). Even though research has been conducted on the relationship between the supervisor and the PhD student (e.g. Watts, 2009; Delamont et al., 1998; Deuchar, 2008), to the authors’ knowledge TA has not yet been applied in relation to the PhD student supervision process. This underlines a plausible improvement potential in using TA related to the PhD student supervision process, in order to enhance understanding of the complex PhD student supervision process. The aim of this paper is to explore the use of Transactional Analysis (TA) in PhD student supervision and it is an attempt to enhance understanding of this complex and important process. The paper first briefly introduces the scientific discourse on research in higher education and then the concept of TA in relation to the PhD student supervision process. The model is then related to empirical findings from a survey among PhD students.

The survey was conducted at one of the five larger universities in Sweden with the aim of mapping PhD students’ research and work environments (Lindblad & Ullman, 2010). In September and October 2010, a webbased questionnaire was sent to all PhD students registered at Linköping University who were at least 1% active as PhD students (n = 1132). The response rate was 70% (n = 794). The response rate for women and men was equal (70%) but the figure differed between faculties, where the response rate for Arts and Sciences (AS) and Science and Engineering (SE) were higher (72%) than those for Health Sciences (HS) (68%) and Educational Sciences (ES) (61%). The questions in the survey covered such areas as level of satisfaction in general, attitudes towards the university and the work environment, and current experiences of supervision and the supervisor-PhD student relationship. The questionnaire also had an open part at the end to allow respondents to make general comments. A total of 13 pages of free text responses were collected. For this paper, we selected answers related to the two latter groups of questions: experiences of supervision and relationships between supervisor and PhD student.

In the survey, different statements were presented to the respondents. One example was: “The time which I receive for supervision satisfies my needs”. Respondents were asked to tick one of six boxes, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (agree completely) and also a “don’t know” alternative. Findings from this survey are presented below.

Generally, questions about supervision have in previous surveys proven to be the area that generated the highest frequency of comments and the strongest opinions from respondents (Andersson, 2005). A conclusion drawn from previous surveys is thus that the relationship between supervisor and PhD student might be the single most important factor determining success or failure in getting a PhD. The answers might therefore be a clue to understanding drop-outs and the questionnaire was designed to include relatively many questions about the relationship (Lindblad & Ullman, 2010).

PhD student supervision is highly complex and thus most likely cannot be fully understood by means of one single theory, or, as stated by the Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (2003)’s study of PhD student supervision covering 900 PhD students: “A striking observation during our work in the project has been how complex the supervision relationship is and how it works” (Swedish National Agency for Higher Education, 2003).

2. Transactional Analysis (TA) in Relation to PhD Student Supervision

TA states that when individuals interact with one another, three major roles may be taken. One is the role of an Adult who is communicating with another Adult. In TA, this is the desired outcome of a well-established relationship between two people. Apart from the Adult role, one may also take the role of a Parent or that of a Child. Using these three roles, four standpoints might be taken: I’m okay, You’re okay; I’m okay, You’re not okay; I’m not okay, You’re okay; I’m not okay, You’re not okay, see Figure 1 (Stewart, 2007; Berne, 1964).

Figure 1. Transactional Analysis (TA), and the three different roles, Parent, Adult, and Child, which might be taken. (Inspired by on Johnson, 2011).

The Adult role is a state in which the individual takes balanced decisions free from feelings. The Parent role, on the other hand, may represent the unconscious reaction to the way that person was threatened during childhood. Finally, the Child role is a state where the individual acts in the way he or she used to act during childhood (Stewart, 2007).

Naturally, the actions and attitudes from a parent towards a new-born baby are quite different from a mother’s or father’s interaction with a teenager. While the former takes the role of a Parent to Child relationship, the latter preferably includes a degree of Adult to Adult relationship. It is argued that the very same parable holds for the education system, including higher education and post-graduate studies. During first grade in elementary school, children are taught extensively by the teacher, with a low degree of freedom and a high degree of standardized teaching material, i.e. a more Parent to Child-relationship. However, for those who end up pursuing studies at University level, the final part of most graduate programmes, or post-graduate programmes (PhD studies), involves lower levels of standardized teaching methods. Instead, there is a high degree of freedom involved, a more Adult to Adult relationship between the teacher/supervisor and the student/PhD student.

Connecting TA to PhD student supervision indicates that the degree of freedom given to the student by the supervisor needs to be consistent with the PhD student’s current capacity and ability to take responsibility, as well as the supervisor’s perceived trust or belief in the PhD student. The goal in TA, to reach an Adult to Adult relationship, may thus be said to be closely related to the goal in higher education of producing a mature junior researcher, ready to conduct his or her own research in his or her particular field.

Connecting TA to PhD student supervision may reveal some further insight of importance for understanding and improving the PhD student supervision process. According to TA, the actions of a person in a stressful situation, may lead to a switch from an Adult role to a Child role. What in turn is perceived as a stressful situation, according to TA, is heavily dependent on past experience of similar relationships, in particular relationships with parents. This implies, we argue, that a supervisor using the same tone of voice as, or similar body language to, a parent of a PhD student, who has violated integrity borders during the PhD student’s childhood, may prevent the PhD student from moving forward to an improved level of relationship with the supervisor. Instead, a type of game play may be the outcome, where the supervisor may or may not be aware that the student is acting as he or she acted when his or her parent interacted with the PhD student during childhood. If the supervisor has characteristics which make the PhD student perceive the supervisor in any way like his or her own parent, particularly if related to negative experiences, there is a risk that the supervisor-PhD student relationship will be affected negatively.

It must be noted in this context that the opposite could also be the case, i.e. a mature PhD student who has to deal with a supervisor who, based on his or her previous relationships, particularly with parents, can make the supervisor perceive the PhD student as something other than what the PhD student intends to be. An active role on the part of the PhD student in discussions with the supervisor could be perceived as disrespectful, regardless of the noble intents of the PhD student. Or a too passive role on the part of the PhD student might be perceived a lack of interest in the subject, etc.

If the supervisor (and preferably also the PhD student) understands this, the chances of a successful outcome, i.e. a mature researcher finalizing his or her post-graduate studies, might increase. In fact, a means to improve this may be for the supervisor to aim to strengthen the relationship by asking questions that are irrelevant to the project such: What was the canteen food like today? Did you have a good weekend? Will the national team win today’s soccer game do you think?

On the contrary, an immature relationship between the supervisor and the PhD student may not only take the form of an Adult supervisor and a Child student, the opposite may also occur, i.e. it is the supervisor who takes a more childish (or perhaps very passive) role and the PhD student takes a more offensive Adult role. Such relationship roles may work given that the work is in progress. However, if the PhD student ends up taking turns in the work, which is not within the scope of what has been agreed upon, and this does not change over a period of time, these relationship roles, positions, or as Berne (1964) would put it, games, may generate problems in the PhD supervision process. Eventually, the supervisor should at least take up a more Parental position stating that work is not going so well in his or her eyes. Here a conflict is certain to occur with a very uncertain outcome. This risk of such a conflict could however be greatly reduced if the supervisor maintains a continuous dialogue with the student and already at an early stage indicates his or her view. A previous passive role on the part of the supervisor will on the contrary increase the risk of a negative outcome, e.g. a change of supervisor or even termination of the PhD studies. This may be reflected in the second phase of Hessle (1987)’s legitimacy ladder, shown in Figure 2.

TA in relation to Hessle (1987)’s work on the legitimacy ladder applied to PhD education thus provides some further input to the complexity of the supervision process.

The ability of the PhD student to foster assignments and challenges given by the mission and the supervisor is not static but rather, as in the case of raising a child, changes over time. If the supervisor is unfamiliar with this, he or she might provide too slack guidelines to the student (Adult to Adult) too early in the process, leading to a potential risk of failure with regard to the given assignment or challenge, e.g. writing the first peer-reviewed article, conducting the first in-depth interview study, doing the first lab experiment, or building the first optimization or simulation model. Or the supervisor might provide too strict guidelines to the student (Parent to Child), even though the PhD student has the necessary capacity with regard to the given assignment or challenge. This creates a risk of the PhD student following the guidelines given by the supervisor, but which does not, given that it is static over time, encourage and empower the PhD student to think in new and innovative ways. Rather, it may at worst create a passive listener with little left for own initiatives, an undesired outcome in higher education.

The role of the supervisor or teacher was outlined as a factor of major importance in a study by Rosenthal and Jacobson (1966), who conducted an IQtest on all the students, grade one to six, in an American elementary school. After the IQtest was collected and the results were known, the researchers randomly selected a number of students at the local elementary school and told the teachers that these were the top-ranked students at their school, expected to produce great learning improvement. Naturally, not all of these students were doing quite so well with their studies. After a period of eight months, the researchers approached the local elementary school once again and conducted a second IQtest. While one may question the research ethics of this research design, the results were surprising. The results from the second IQtest showed that the randomly selected “top-ranked” students had now significantly increased their IQtest results: “For the school as a whole those children from whom the teachers had been led to expect greater intellectual gain showed a significantly greater gain in IQ score than did the control children”.

Rosenthal and Jacobson (1966) suggested that the teachers, after the first IQtest results were presented, took a more mature approach towards the high-ranked students. For some students, this implied that the teacher did not merely look into the visual realm, as not all of the claimed high-score students in fact had as good prerequisites to perform well. Based on Rosenthal and Jacobson (1966), believing in the PhD students may thus be stated to represent a basic element in successful PhD student supervision, rather than a more controlling Parent to Child approach.

Figure 2. The legitimacy ladder applied on PhD-education (Hessle, 1987).

3. A Modified Model for Increased Understanding of the PhD Student Supervision Process

Using TA and the legitimacy ladder applied to PhD education, a modified model for greater understanding of the PhD student supervision process may be developed. This modified model, which is a contribution from TA and the legitimacy ladder applied to PhD education, outlines some important aspects. In relation to raising a child, the need to “blindly support” the PhD student at the beginning of the PhD student supervision process cannot be emphasized enough. This may be done by various means but includes, as with raising a child, a balance between more parental means and vast amounts of encouragement and support. This “blind support” naturally involves a higher degree of risk than when the PhD student is at the end of their PhD education. Frankly speaking, the supervisor may face the risk of supporting a person from whom he or she cannot at the moment see any visible results; results are (hopefully) yet to come. For a parent, this support may be of a rebellious young boy or girl in their teens on their way into adulthood, and in the case of post-graduate education, might be a seemingly uninterested PhD student heading towards their doctoral thesis presentation. With the often rigid quality control which exists in the scientific discourse, with little (nothing) left for gambling or taking great risks, this may naturally be one of the most challenging aspects for the PhD supervisor. A very rigid supervisor or supervision structure with rules and regulations, may, in fact, simply be a manifestation of lack of belief or trust in the PhD student.

Violations of the aspect of trust may, as stated earlier, rather create a passive listener, not ready to conduct independent research (the fifth step in Hessle (1987)’s legitimacy ladder), and even worse, create a risk of the PhD student terminating their PhD education. This is understood by Halse and Malfroy (2010) as the Learning Alliance: “Supervisors described the importance of a personable relationship with students as central to the learning alliance, as the following interview extracts illustrate: My relationship with my students is one based on mutual respect, rapport, genuine warmth … I also like to make sure that my students and I interact with a sense of humour…Supervisors also emphasized that the learning alliance is not an equal or democratic” (Halse & Malfroy, 2010).

4. Results from a Survey on the PhD Student Supervision Process among PhD Students

A requisite for building relationships between PhD student and supervisor is to have contact and to communicate. The PhD students’ responses to the question “How often do you receive some form of guidance/supervision from your supervisor? Consider the spring semester 2010” were as follows, see Table 1.

In the questionnaire, PhD students were also asked answer “How well do you agree with the following statements about your supervisor (main supervisor and assistant supervisors) and your general situation with regard to supervision?”

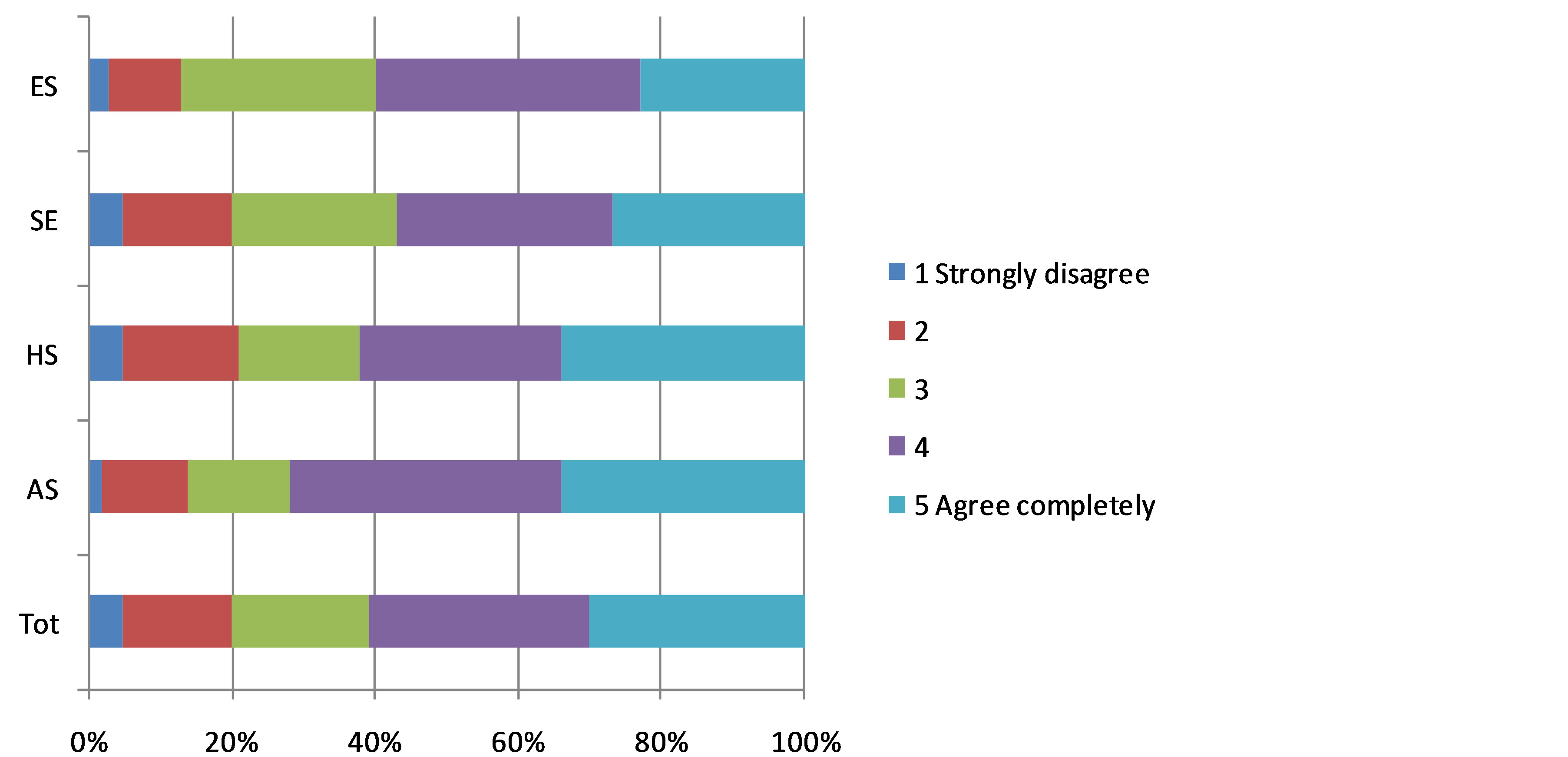

Regarding time for supervision, students were asked to answer whether they thought the time they got was sufficient. Figure 3 shows the results. Most answers were positive but in about 20% of cases were on the negative side, i.e. the students want more time for supervision.

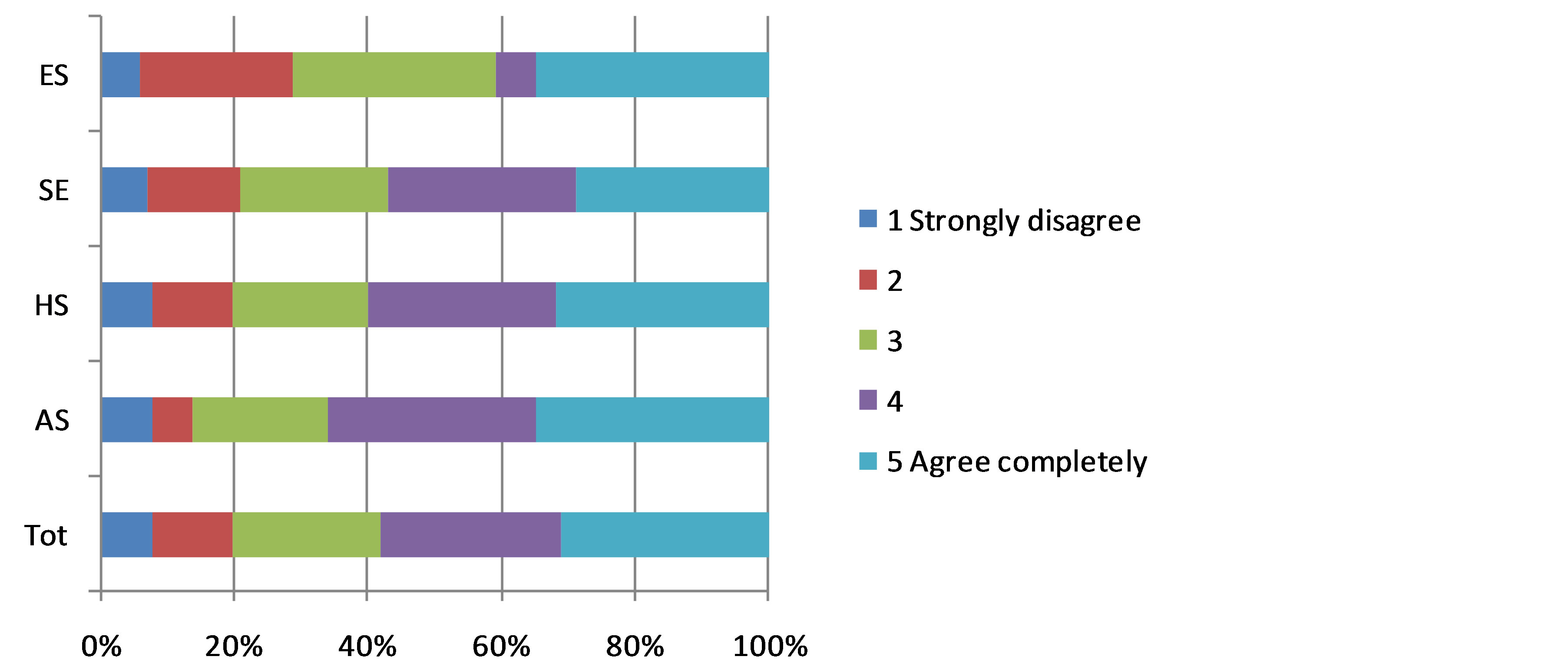

Another indicator of PhD student-supervisor relationships identified for this research was how the supervisor(s) facilitated contact with other researchers (see Figure 4). Again, 20% of the answers were on the negative side. PhD students in Educational Sciences (ES) stood out as slightly more negative and almost 30% experienced that supervisors do not open their professional networks for the student.

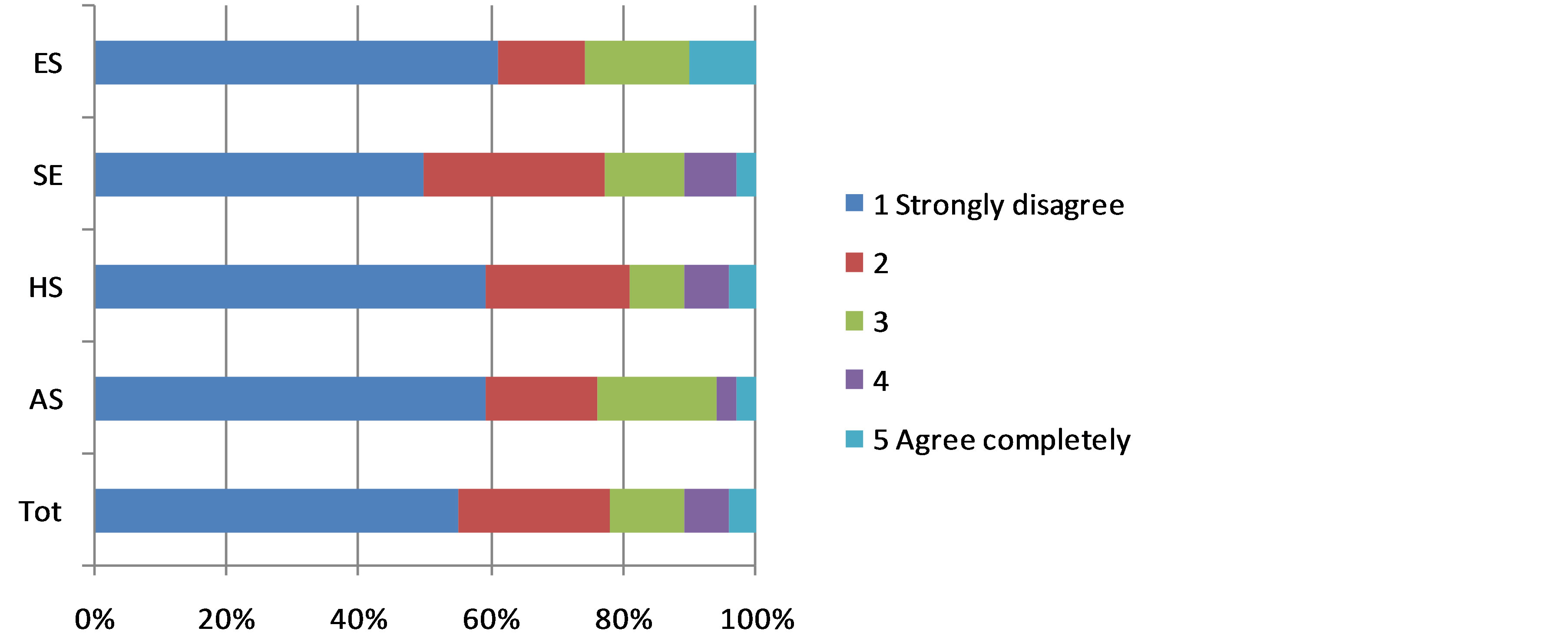

Heavy dependency on the main supervisor has proven to be problematic and can cause the student to stay longer in a negative relationship since no alternatives are within reach. The question that the students were asked to react to was: “I am in a situation of dependency upon my main supervisor, which is worrying/problematic”. the results can be seen in Figure 5. In all, about 10% experienced this.

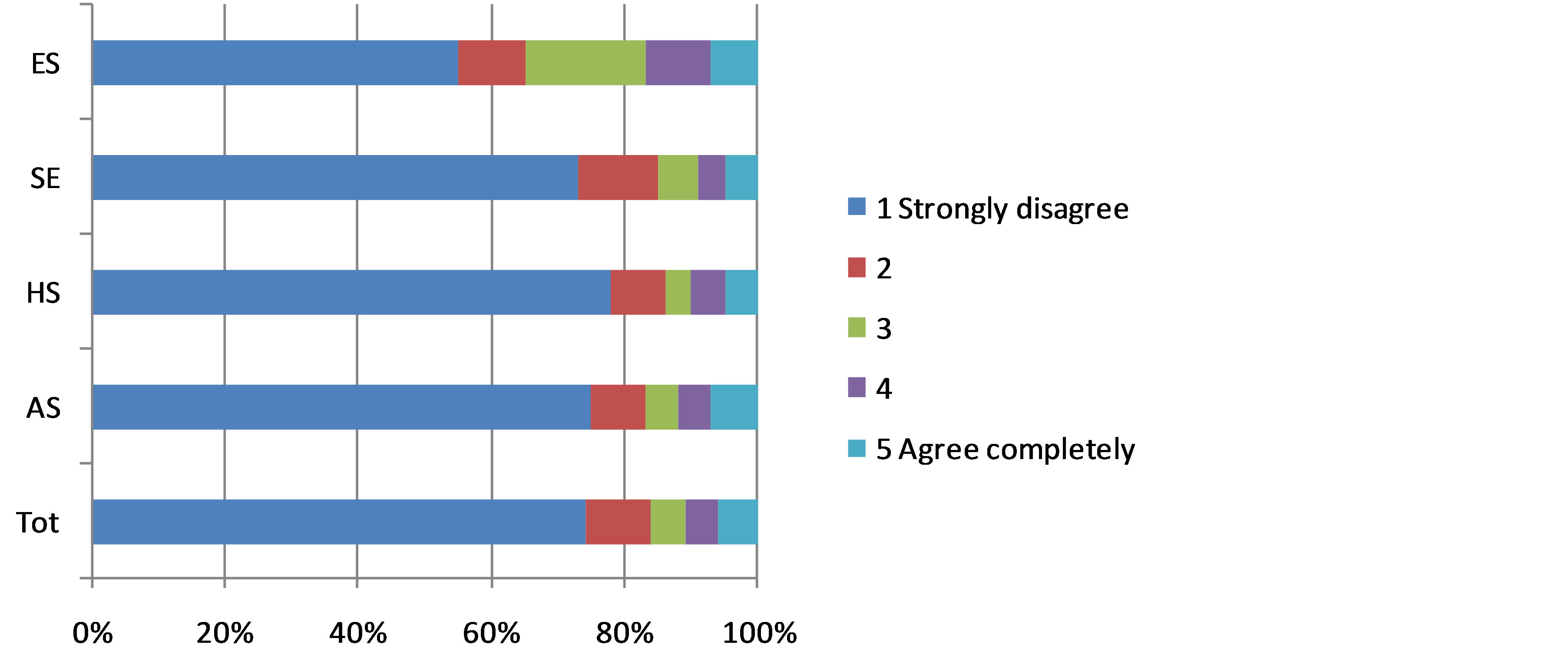

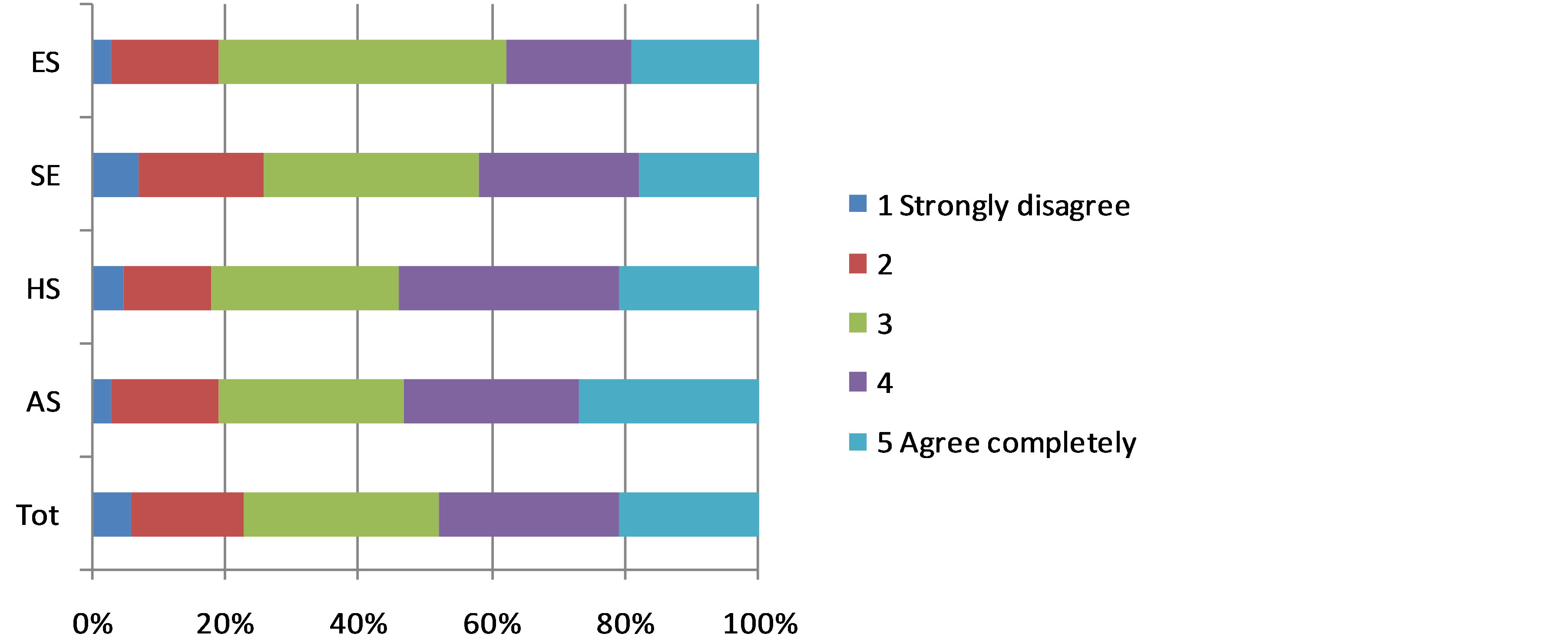

Another indicator of a good supervisor-PhD student relationship is a good balance between demand and support from the supervisor. The results are shown in Figure 6. 15% of the answers were on the negative side. Noticeable is that none of the PhD students in Educational Sciences (ES) were totally satisfied with the balance.

Experiences of deficiencies in supervision may also show how the relationship between PhD student and supervisor is working. Figure 7 shows the responses to the statement “I feel that deficiencies in the supervision I receive hamper the work with my thesis.” More than 15% of the PhD students agreed with this, students in Science and Engineering (SE) and Health Sciences (HS) a little more than the others. Students in Arts and Sciences

Table 1. Frequency (%) of contact with guidance/supervision between PhD student and supervisor. (Abbreviations: Arts and Sciences (AS), Science and Engineering (SE), Health Sciences (HS) and Educational Sciences (ES)) (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

Figure 3. Answers to the statement: The time which I receive for supervision satisfies my needs (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

Figure 4. Answers to the statement: My supervisor/-s facilitates contacts with other researchers (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

Figure 5. Answers to the statement: I am in a situation of dependency upon my main supervisor, which is worrying/problematic (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

Figure 6. Answers to the statement: There is a good balance between the demands which my supervisor(s) put(s) on me and the support which I receive (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

Figure 7. Answers to the statement: I feel that deficiencies in the supervision I receive hampers the work with my thesis (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

(AS) responded more negatively than the other students.

Change of supervisor is one way to end a non-functioning relationship between PhD Student and supervisor, see Figure 8. 11% agreed to some extent that they had considered a change of supervisor. Students in Educational Sciences (ES) agreed with this slightly more strongly, 17%. Also noticeable is that fewer ES students answered “strongly disagree” than students from the other faculties.

Responses to the statement “The supervisor/-s gives me a straight answer about my responsibility and what is expected from me in the on-going work” varied, see Figure 9. More than 20% of the PhD students answered negatively. About 50% thought that the level of straight answers and clear expectations were satisfactory and about one third were neither negative nor positive and ticked the middle box.

About one fourth of all PhD students have experienced a lack of planned meetings for supervision, see Figure 10. In total, this phenomenon is a little less common in Educational Science (ES), while students in other areas had a similar degree of negative answers. However, more students in ES had strong negative experiences (ticked 5) of lack of planned meetings.

On the general level, most PhD students agreed with the statement that supervision had worked well over the last year, see Figure 11. Students in Arts and Sciences responded more positively to this statement than the other students.

Figure 8. Answers to the statement: I have been considering a change of supervisor (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

Figure 9. Answers to the statement: The supervisor/-s gives me a straight answer about my responsibility and what is expected from me in the on-going work (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

Figure 10. Answers to the statement: I have experienced a lack of planned meetings for supervision (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

Figure 11. Answers to the statement: In conclusion: In my view, the supervision has worked well during the past year (LiU Questionnaire, 2010).

In general, the PhD students responded that supervision worked well, but there was a difference in the answers between men and women (Lindblad & Ullman 2011). Women in Science and Engineering (SE) and Health Sciences (HS) thought to a lesser extent that supervision worked well. The difference was about 10 percentage points for each. The opposite was true of students in Educational Sciences (ES), where men were less satisfied with supervision. Here the difference was greater, about 35 percentage points.

In general, the 2010 survey concluded that on the positive side of the PhD studies were good supervisors, senior researchers and other PhD students as colleagues. They were perceived as helpful, supportive, acknowledging and respectful and there were no hierarchies (Lindblad & Ullman, 2010). One PhD student stated:

“I have a very good and competent main supervisor who is very responsive and takes care of the economic part for me. The department’s PhD student principal and the administrators are always supportive. There is a good plan in my department for how the PhD student process should proceed which allows for individualization. I feel that everyone (PhD students, assistant professors, lab assistants, lecturers and professors) I contact for advice concerning for example research methods are supportive, that we want to support each other to push colleagues’ research forward here at AA if one has the chance to do so. I have a decent working place.” (PhD Student)

On the negative side were supervisors that did not do their job and gave slow or bad feedback. The dependency on a single supervisor was also perceived as negative. According to one of the students:

“To not be so dependent on the supervisor’s arbitrary standpoints all the time, which among other things means that in practice, one cannot apply for another PhD student position at the same university without it affecting both the continuation of supervision process and one’s future career. The dependency is almost feudal.” (PhD Student 2010).

5. Concluding Discussion

TA has provided valuable and interesting insight into the PhD supervision process, and can lead to new questions about how PhD supervision could be better organized and carried out. The empirical results from the survey presented in this paper support the idea of that bringing TA into this highly complex issue—PhD student supervision—an increased understanding of the process is gained. Ultimately, bringing in the TA model would help improve the quality of post-graduate education, by allowing us to structure our supervision in a more aligned way related to the goal of reaching an adult-adult relation at the end of the post-graduate time. It is evident as such that there is not one-approach-fits-all in relation to this process. Factors like faculty and department cultures and routines, knowledge discourse, i.e. episteme, techne etc., and numerous other factors, influence the process. However, with an implicit goal of viewing the PhD-supervision as a process of moving the relationship from Adult-to-Child to Adult-to-Adult, an improved supervision is likely to occur.

The next step to further investigate the relationship between PhD students and their supervisors would be to dig deeper into certain aspects of this relationship. It is suggested that this include a methodological switch from questionnaire to in-depth interviews. It would also be of great importance here to include the perspectives of the supervisors.

The modified TA model presented in this paper distinguishes the need for the supervisor to balance his or her role towards the PhD student. This balance, as also presented by Hessle (1987), changes over time. From a TA perspective, a professional PhD student supervision process means moving from a Parent to Child relationship between the supervisor and the PhD student towards a mature Adult to Adult relationship—in summary a balancing process.

References

- Andersson, K. (2005). Livet som doktorand vid Linköpings universitet (Life as PhD student at Linköping University). Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Armstrong, S. J. (2004). The Impact of Supervisors’ Cognitive Style on the Quality of Research Supervision in Management Education. British Journal of Psychology, 74, 599-616.

- Baker, V. L., & Lattuca, L. R. (2010). Development Networks and Learning: Towards an Interdisciplinary Perspective on Identity Development during Doctorial Study. Studies in Higher Education, 35, 807-827. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070903501887

- Berne, E. (1964). Games People Play: The Basic Hand Book of Transactional Analysis. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Bjurmark, A. (2011). Personal Communication. Linköping. (in Swedish)

- Degerblad, J.-E., & Hägglund, S. (2001). Kriterier vid bedömning av forskarutbildning. Högskoleverket: Leanders Tryckeri AB, Kalmar. (in Swedish)

- Delamont, S., Parry, O., & Atkinson, P. (1998). Creating a Delicate Balance: The Doctoral Supervisor’s Dilemmas. Teaching in Higher Education, 3, 157-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1356215980030203

- Deuchar, R. (2008). Facilitator, Director or Critical Friend?: Contradiction and Congruence in Doctoral Supervision Styles. Teaching in Higher Education, 13, 489-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562510802193905

- Halse, C., & Malfroy, J. (2010). Retheorizing Doctorial Supervision as Professional Work. Studies in Higher Education, 35, 79-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070902906798

- Hessle, S. (1987). En modell för kunskapsformation i forskarutbildningen. Rapport i socialt arbete nr 31, Stockholm: Stockholm University. (in Swedish)

- Johnson, R. (2011). Transactional Analysis Psychotherapy: Three Methods Describing a Transactional Analysis Group Therapy. Doctoral Dissertation, Lund: Lund University.

- LiU Questionnaire (2010). PhD Student Questionnaire at Linköping University 2010. Resultdiagram for LiU Total, LiU-2010-01063. (in Swedish)

- Mainhard, T., Van Der Rijst, R., et al. (2009). A Model for the Supervisor—Doctorial Student Relationship. Higher Education, 58, 359-373. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9199-8

- Manathunga, C., & Goozée, J. (2007). Challenging the Dual Assumption of the “Always/Already” Autonomous Student and Effective Supervisor. Teaching in Higher Education, 12, 309-322. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562510701278658

- Pearson, M., & Kayrooz, C. (2004). Enabling Critical Reflection on Research Supervisory Practice. International Journal of Academic Development, 9, 99-116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1360144042000296107

- Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1966). Teachers’ Expectancies: Determinants of Pupils’ IQ Gains. Psychological Reports, 19, 115-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1966.19.1.115

- Stewart, (2007). Transaktionsanalysens grunder: En ny introduktion. Falköping: TAiF. (in Swedish)

- Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (2003). Forskarhandledning: möte med vandrareochmedvandrarepå vetenskapensvägar (PhD Supervision: Meeting with Hikers and Co-Hikers on the Roads of Science). Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Higher Education. (in Swedish)

NOTES

*Corresponding author.