Advances in Pure Mathematics

Vol.06 No.10(2016), Article ID:70665,17 pages

10.4236/apm.2016.610055

A Weight-Coded Evolutionary Algorithm for the Multidimensional Knapsack Problem

Quan Yuan, Zhixin Yang

Department of Mathematical Science, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: March 14, 2016; Accepted: September 16, 2016; Published: September 19, 2016

ABSTRACT

A revised weight-coded evolutionary algorithm (RWCEA) is proposed for solving multidimensional knapsack problems. This RWCEA uses a new decoding method and incorporates a heuristic method in initialization. Computational results show that the RWCEA performs better than a weight-coded evolutionary algorithm pro- posed by Raidl (1999) and to some existing benchmarks, it can yield better results than the ones reported in the OR-library.

Keywords:

Weight-Coding, Evolutionary Algorithm, Multidimensional Knapsack Problem (MKP)

1. Introduction

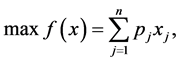

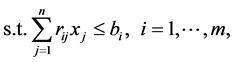

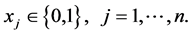

The multidimensional knapsack problem (MKP) can be stated as:

(1a)

(1a)

(1b)

(1b)

(1c)

(1c)

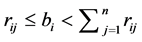

Each of the m constraints described in (1b) is called a knapsack constraint. A set of n items with profits  and m resources with

and m resources with  are given. Each item j con- sumes an amount

are given. Each item j con- sumes an amount  from each resource i. The 0-1 decision variables

from each resource i. The 0-1 decision variables  indicate which items are selected. A well-stated MKP also assumes that

indicate which items are selected. A well-stated MKP also assumes that  and

and  for all

for all ,

,  , since any violation of these condi- tions will result in some constraints being eliminated or some

, since any violation of these condi- tions will result in some constraints being eliminated or some ’s being fixed.

’s being fixed.

The MKP degenerates to the knapsack problem when  in Equation (1b). It is well known that the knapsack problem is not a strong

in Equation (1b). It is well known that the knapsack problem is not a strong  -hard problem and solvable in pseudo-polynomial time. However, the situation is different to the general case of

-hard problem and solvable in pseudo-polynomial time. However, the situation is different to the general case of . Garey and Johnson (1979) [1] proved that it is strongly

. Garey and Johnson (1979) [1] proved that it is strongly  -hard and exact techniques are in practice only applicable to instances of small to moderate size.

-hard and exact techniques are in practice only applicable to instances of small to moderate size.

A real-world application example of MKP is selecting projects to fund. Assume there are n different projects and we need to select some projects and fund them for m years. Each project provides a profit and each of them has a budget determined for each year. Our objective is to maximize the total profit and not exceed yearly budgets. This problem can be formulated as Equation (1). What is more, many practical problems such as the capital budgeting problem [2] , allocating processors and databases in a distributed computer system [3] , project selection and cargo loading [4] , and cutting stock problems [5] can be formulated as an MKP. The MKP is also a sub problem of many general integer programs.

Given the theoretical and practical importance of the MKP, a large number of papers have devoted to the problem. It is not the place here to recall all of these papers. We refer to the papers of Chu and Beasley (1998) [6] , Fréville (2004) [7] and the monograph of Kellerer (2004) [8] for excellent overviews of theoretical analysis, exact methods, and heuristics of the MKP. Recently, some new algorithms for the MKP have been proposed such as some variants of the genetic algorithm [9] , the ant colony algorithm [10] , the scatter search method [11] , and some new heuristics [12] - [15] . Some studies on analysis of the MKP [16] , [17] and generalizations of the MKP [18] - [20] have also been put forward.

An Evolutionary algorithm (EA) is a generic population-based metaheuristic optimization algorithm. Candidate solutions to the optimization problem play the role of individuals (parents) in a population. Some mechanisms inspired by biological evolution: selection, crossover and mutation are used. The fitness function determines the environment within which the solutions “survive”. Then new groups of the population (children) are generated after the repeated application of the above operators. EAs have found application in computational science, engineering, economics, chemistry, and many other fields (see [21] - [25] ).

In the last two decades EAs were studied for solving the MKP. Although the early works do not successfully show that genetic algorithms (GAs) were an effective tool for the MKP, the first successful GA’s implementation was proposed by Chu and Beasley (1998) [6] . Extended numerical comparisons with CPLEX (version 4.0) and other heuristic methods showed that Chu and Beasley’s GA has a robust behavior and can obtain high-quality solutions within a reasonable amount of computational time. Raidl and Gottlieb (2005) [17] introduced and compared six different EAs for the MKP, and performed static and dynamic analyses explaining the success or failure of these algorithms, respectively. They concluded that an EA based on direct representation, combined with local heuristic improvement (referred to as DIH in [17] , i.e., GA of Chu and Beasley (1998) [6] with slight revision), can achieve better performance than other EAs mentioned in [17] from empirical analysis.

The best success for solving the MKP, as far as we known, has been obtained with tabu-search algorithms embedding effective preprocessing [26] , [27] . Recently, impressive results have also been obtained by an implicit enumeration [28] , a convergent algorithm [29] , and an exact method based on a multi-level search strategy [30] . Compared with EAs, the methods mentioned above can yield better results when excellent solutions are required. But they are more complicated to implement or their computation takes extremely long time. Since EAs are simple to implement and their computation time are easy to control, they are good alternatives if the quality requirement of solutions of the MKP is not very strict.

In this paper, we will consider a variant of EA to solve the MKP. This EA will use a special encoding technique which is called weight-coding (or weight-biasing). We will revise a weight-coded EA (WCEA) proposed by Raidl (1999) [31] and propose a revised weight-coded EA (RWCEA). The numerical experiments of some benchmarks will show that the RWCEA performs better than the WCEA. Moreover, this RWCEA can compete with DIH in some benchmarks.

2. An Introduction to the Weight-Coding and Its Application to the MKP

When combinatorial optimization problems are solved by an EA, the coding of candi- date solutions is a preliminary step. Direct coding such as the binary coding is an intui- tive method. The main drawback of this coding lies in that many infeasible solutions may be generated by EA’s operators. To avoid that, the basic idea of the weight-coding is to represent a candidate solution by a vector of real-valued weights . The phenotype that a weight vector represents is obtained by a two-step process.

. The phenotype that a weight vector represents is obtained by a two-step process.

Step (a): (biasing) The original problem P is temporarily modified to  by biasing problem parameters of P according to the weights

by biasing problem parameters of P according to the weights

Step (b): (decoding heuristic) A problem-specific decoding heuristic is used to gene- rate a solution to

The weight-coding is an interesting approach because it can eliminate the necessity of an explicit repair algorithm, a penalization of infeasible solutions, or special crossover and mutation operators. It has already been successfully used for a variety of problems such as an optimum communications spanning tree problem [32] , problem [33] , the traveling salesman problem [34] , and the multiple container packing problem [35] .

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the work of Raidl (1999) [31] is the first to use weight-coded EA (WCEA) to deal with the MKP. In that paper, some variants of WCEAs were proposed and compared. And Raidl finally suggested one of them and compared the WCEA with other EAs in [17] . In this WCEA,

where

Corresponding to Step (b), the decoding heuristic which Raidl (1999) [31] suggested is making use of the surrogate relaxation (see [36] , [37] ). The m resource constraints (1b) are aggregated into a single constraint using surrogate multipliers

where

A higher pseudo-utility ratio heuristically indicates that an item is more efficient. After the items are sorted by decreasing order of

Raidl’s WCEA can be described as follows (we will explain the details of Steps 6, 7, and 8 afterward):

Algorithm of Raidl’s WCEA

Step 1: set

Step 2: initialize

Step 3: evaluate

for each

3-1: bias original MKP;

3-2: use decoding heuristic as in [31] (described above) to get phenotype

3-3: substitute

Step 4: find

Step 5: select

Step 6: crossover

Step 7: mutate C;

Step 8: evaluate C as Step 3, get

Step 9: if

Step 10: discard C and goto Step 6;

end if

Step 11: find

Step 12: if

Step 13:

end if

Step 14:

end while

Step 15: return

In Step 6, a binary tournament selection is used. That is, two pools of individuals, which consist of 2 individuals drawn from the population randomly, are formed re- spectively at first. Then two individuals with the best fitness, each taken from one of the two tournament pools, are chosen to be parents.

In Step 7, Raidl (1999) [31] suggested a uniform crossover instead of one- or two- point crossover. In the uniform crossover two parents have one child. Each

Once a child has been generated through the crossover, a mutation step in Step 8 is performed. Each

In numerical experiments, the N in Step 2 is taken as 100 and

3. Our Revised WCEA for the MKP

3.1. Motivation

The core of Raidl’s WCEA is the surrogate relaxation based heuristic in decoding. In our points of view, this heuristic has two drawbacks. First, the dual variables of an LP- relaxed MKP used in heuristic decoding step are just good approximations of optimal surrogate multipliers and it may mislead the search [26] . LP-relaxed MKP used in heuristic decoding step are just approximations of optimal surrogate multipliers. And deriving optimal surrogate multipliers is a difficult task in practice [38] . Secondly, the heuristic decoding might mislead the search if the optimal solution is not very similar to the solution generated by applying the greedy heuristic [39] .

In order to avoid using surrogate multipliers, we set

as mentioned in Section II, all feasible solutions of this biased MKP are feasible to (1). In decoding heuristic, we also use first-fit strategy, i.e., the items are sorted by de- creasing order of

This form of

It is well known that only relaxing the integrality constraints in an MKP may not be sufficient because its optimal solution may be far away from the optimal binary solution. However, Vasquez and Hao in [26] observed when the integrality constraints was replaced by a hyperplane constraint

In the above example, if we take

Inspired by this idea, initialization is guided by the LP relaxation with a hyperplane constraint. To begin with, we use some simple heuristic (such as a greedy algorithm) to obtain a 0 - 1 lower bound z. Next, the two following problems:

and

are solved to obtain

Then, N linear programming problems

are solved where

3.2. Implementation

The scheme of the RWCEA is as follows:

Algorithm of the RWCEA

Step 1: set

Step 2: initialize

3-1: bias original MKP;

3-2: use decoding heuristic as in [31] (described in Section 2) to get phenotype

3-3: substitute

Step 3: find

Step 4: select

Step 5: crossover

Step 6: mutate C: one random

Step 7: evaluate C as Step 3, get

Step 8: if

Step 9: discard C and goto Step 6;

end if

Step 10: find

Step 11: if

Step 12:

end if

Step 13:

end while

Step 14: return

The scheme of the RWCEA is similar to Raidl’s WCEA. And we take the same values of N and

1) The initial population in Raidl’s WCEA is generated randomly, while in the RWCEA, N linear programming problems should be solved;

2) Each

3) Raidl’s WCEA sorts items by pseudo-utility ratios in heuristic decoding step while the RWCEA sorts items by biased profits directly;

4) In the mutation step, one random

In summary, we revised Raidl’s WCEA by avoiding using surrogate multipliers and using “good” initial population. We think this RWCEA can yield better result than WCEA in some instances of MKP. The performance of RWCEA is shown in the next section.

4. Experimental Comparison

As in [17] , two test suites of MKP’s benchmark instances for experimental comparison are used in this paper. The first one, referred to as CB-suite in this paper, is introduced by Chu and Beasley (1998) [6] and is available in the OR-Library1. This test suite contains 270 instances for each 10 ones are combination of

Although some commercial integral linear programming (ILP) solvers, such as CPLEX, can solve ILP problems with thousands of integer variables or even more, it seems that the MKP remains rather difficult to handle when an optimal solution is wanted. To CB- suit, the results in [6] showed that major instances of this suit cannot be solved in a reasonable amount of CPU time and memory by CPLEX. To GK-suit, which includes still more difficult instances with n up to 2500, Fréville (2004) in [7] mentioned that CPLEX cannot tackle these instances. Therefore, it appears that the MKP continues to be a challenging problem for commercial ILP solvers.

The best known solutions to these benchmarks, as far as we known, were obtained by Vasquez and Hao (2001) [26] and was improved by Vasquez and Vimont (2005) [27] . Their method is based on tabu search and time-consuming compared with EA.

Raidl and Gottlieb (2005) [17] tested six different variants of EAs, which are called Permutation Representation (PE), Ordinal Representation (OR), Random-Key Represen- tation (RK), Weight-Biased Representation (WB), i.e. Raidl’s WCEA, and Direct Repre- sentation (DI and DIH). We compare the RWCEA with these EAs except DIH first. We use all GK-suite and draw out nine instances (called CB1 to CB9) from CB-suite, which are the first instances with

For a solution x, the gap is defined as:

where

We implement the RWCEA on a personal computer (Inter CoreTM Duo T5800, 2 GHz, 1.99 GB main memory, Windows XP) using DEV-C++. The initial population is generated by MATLAB. The population size is 100, and each run was terminated after 106 created solution candidates; rejected duplicates were not counted.

Table 1 shows the average gaps of the final solutions and their standard deviations obtained from independent 30 runs per problem instance obtained by the RWCEA and other six variants. The results of other six variants come from [17] . In the last column, bold fonts mean that the results of RWCEA is the best (or equally best) in the seven EAs. Italics in the last column mean that the results of RWCEA is better or equal than PE, OR, RK, DI, and WCEA but slightly worse than DIH. From this table we can draw the conclusion that the RWCEA is an improvement of WCEA. Especially in GK02 to GK11, the RWCEA performed much better than Raidl’s method.

Table 1 also shows that the RWCEA performed averagely slightly worse than DIH. But we will point out that can yield better results than DIH in some instances. Since the best results can be obtained by CPLEX in CB-suite when

5. Conclusion

We have proposed a RWCEA for solving multidimensional knapsack problems. This

Table 1. Average gaps of best solutions and their standard deviations of the RWCEA and other EAs.

Table 2. The data of the numbers that the RWCEA yielded better, equal and worse results than the results reported in OR-library.

Table 3. The results of CB-suite reported in OR-library (ORCB) and the ones obtained by the RWCEA (

Table 4. The results of CB-suite reported in OR-library (ORCB) and the ones obtained by the RWCEA (

Table 5. The results of CB-suite reported in OR-library (ORCB) and the ones obtained by the RWCEA (

Table 6. The results of CB-suite reported in OR-library (ORCB) and the ones obtained by the RWCEA (

Table 7. The results of CB-suite reported in OR-library (ORCB) and the ones obtained by the RWCEA (

Table 8. The results of CB-suite reported in OR-library (ORCB) and the ones obtained by the RWCEA (

RWCEA has been different from Raidl’s WCEA in the ways that surrogate multipliers are not used and a heuristic method is incorporated in initialization. Experimental com- parison has shown that the RWCEA can yield better results than Raidl’s WCEA in [31] and better results than the ones reported in the OR-library to some existing benchmarks. So we think this RWCEA is a good opinion in solving MKPs. A more detailed investigation of the working mechanism of the RWCEA and the application of RWCEA to other variants of knapsack problems (such as multiple choice multidimensional knapsack problems) will be the subjects of further work.

Cite this paper

Yuan, Q. and Yang, Z.X. (2016) A Weight-Coded Evolutionary Algorithm for the Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Advances in Pure Mathematics, 6, 659-675. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/apm.2016.610055

References

- 1. Garey, M.R. and Johnson, D.S. (1979) Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. W. H. Freeman & Co., New York.

- 2. Markowitz, H.M. and Manne, A.S. (1957) On the Solution of Discrete Programming Problems. Econometrica, 25, 84-110.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1907744 - 3. Gavish, B. and Pirkul, H. (1982) Allocation of Databases and Processors in a Distributed Computing System. In: Akoka, J., Ed., Management of Distributed Data Processing, North-Holland, 31, 215-231.

- 4. Shih, W. (1979) A Branch and Bound Method for the Multiconstraint Zero-One Knapsack Problem. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 30, 369-378.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/jors.1979.78 - 5. Gilmore, P.C. and Gomory, R.E. (1966) The Theory and Computation of Knapsack Func-tions. Operations Research, 14, 1045-1075.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/opre.14.6.1045 - 6. Chu, P.C. and Beasley, J.E. (1998) A Genetic Algorithm for the Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Journal of Heuristics, 4, 63-86.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1009642405419 - 7. Fréville, A. (2004) The Multidimensional 0-1 Knapsack Problem: An Overview. European Journal of Operational Research, 155, 1-21.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(03)00274-1 - 8. Kellerer, H., Pferschy, U. and Pisinger, D. (2004) Knapsack Problems. Springer, Berlin.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-24777-7 - 9. Li, H., Jiao, Y., Zhang, L. and Gu, Z. (2006) Genetic Algorithm Based on the Orthogonal Design for Multidimensional Knapsack Problems. Advances in Natural Computation. Springer Berlin/Heidelberg, 696-705.

- 10. Kong, M., Tian, P. and Kao, Y. (2008) A New Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm for the Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Computers & Operations Research, 35, 2672-2683.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2006.12.029 - 11. Hanafi, S. and Wilbaut, C. (2008) Scatter Search for the 0-1 Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Journal of Mathematical Modelling and Algorithms, 7, 143-159.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10852-008-9078-9 - 12. Boyer, V., Elkihel, M. and El Baz, D. (2009) Heuristics for the 0-1 Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. European Journal of Operational Research, 199, 658-664.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2007.06.068 - 13. Fleszar, K. and Hindi, K.S. (2009) Fast, Effective Heuristics for the 0-1 Multi-Dimensional Knapsack Problem. Computers & Operations Research, 36, 1602-1607.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2008.03.003 - 14. Puchinger, J., Raidl, G.R. and Gruber, M. (2005) Cooperating Memetic and Branch-and-Cut Algorithms for Solving the Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Proceeding of the 6th Metaheuristics International Conference, Vienna, 22-26 August 2005, 775-780.

- 15. Zou, D., Gao, L., Li, S., et al. (2011) Solving 0-1 Knapsack Problem by a Novel Global Harmony Search Algorithm. Applied Soft Computing, 11, 1556-1564.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2010.07.019 - 16. Fréville, A. and Hanafi, S. (2005) The Multidimensional 0-1 Knapsack Problem—Bounds and Computational Aspects. Annals of Operations Research, 139, 195-227.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10479-005-3448-8 - 17. Raidl, G.R. and Gottlieb, J. (2005) Empirical Analysis of Locality, Heritability and Heuristic bias in Evolutionary Algorithms: A Case Study for the Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Evolutionary Computation, 13, 441-475.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/106365605774666886 - 18. Changdar, C., Mahapatra, G.S. and Pal, R.K. (2013) An Ant Colony Optimization Approach for Binary Knapsack Problem under Fuzziness. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 223, 243-253.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2013.07.077 - 19. Hifi, M., M’Halla, H. and Sadfi, S. (2005) An Exact Algorithm for the Knapsack Sharing Problem. Computers & Operations Research, 32, 1311-1324.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2003.11.005 - 20. Mavrotas, G., Figueira, J.R. and Florios, K. (2009) Solving the Bi-Objective Multi-Dimen-sional Knapsack Problem Exploiting the Concept of Core. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 7, 2502-2514.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2009.08.045 - 21. Yuan, Q., Qian, F. and Du, W. (2010) A Hybrid Genetic Algorithm with the Baldwin Effect. Information Sciences, 180, 640-652.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2009.11.015 - 22. Yuan, Q., He, Z. and Leng, H. (2008) A Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for a Class of Global Optimization Problems with Box Constraints. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 197, 924-929.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2007.08.081 - 23. Yuan, Q. and Qian, F. (2010) A Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for Twice Continuously Differentiable NLP Problems. Computers & Chemical Engineering, 34, 36-41.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2009.09.006 - 24. Yuan, Q., He, Z. and Leng, H. (2008) An Evolution Strategy Method for Computing Eigenvalue Bounds of Interval Matrices. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 196, 257-265.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2007.05.051 - 25. Yuan, Q. and Yang, Z. (2013) On the Performance of a Hybrid Genetic Algorithm in Dynamic Environments. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 219, 11408-11413.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2013.06.006 - 26. Vasquez, M. and Hao, J.-K. (2001) A Hybrid Approach for the 0-1 Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Proceeding of the 17th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Seattle, 4-10 August 2001, 328-333.

- 27. Vasquez, M. and Vimont, Y. (2005) Improved Results on the 0-1 Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. European Journal of Operational Research, 165, 70-81.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2004.01.024 - 28. Vimont, Y., Boussier, S. and Vasquez, M. (2008) Reduced Costs Propagation in an Efficient Implicit Enumeration for the 0-1 Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Journal of Combinatorial Optimization, 15, 165-178.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10878-007-9074-4 - 29. Hanafi, S. and Wilbaut, C. (2011) Improved Convergent Heuristic for the 0-1 Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Annals of Operations Research, 183, 125-142.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10479-009-0546-z - 30. Boussier, S., Vasquez, M., Vimont, Y., Hanafi, S. and Michelon, P. (2010) A Multi-Level Search Strategy for the 0-1 Multidimensional Knapsack Problem. Discrete Applied Mathematics, 158, 97-109.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dam.2009.08.007 - 31. Raidl, G.R. (1999) Weight-Codings in a Genetic Algorithm for the Multiconstraint Knapsack Problem. Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Washington DC, 6-9 July 1999, 596-603.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/CEC.1999.781987 - 32. Palmer, C.C. and Kershenbaum, A. (1994) Representing Trees in Genetic Algorithms. Proceeding of the 1st IEEE International Conference of Evolutionary Computation, Orlando, 27-29 June 1994, 379-384.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/icec.1994.349921 - 33. Capp, K. and Julstrom, B. (1998) A Weight-Coded Genetic Algorithm for the Minimum Weight Triangulation Problem. Proceeding of 1998 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Atlanta, 27 February-1 March 1998, 327-331.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/330560.330833 - 34. Julstrom, B. (1998) Comparing Decoding Algorithms in a Weight-Coded GA for TSP. Proceeding of 1998 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Atlanta, 27 February-1 March 1998, 313-317.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/330560.330830 - 35. Raidl, G.R. (1999) A Weight-Coded Genetic Algorithm for the Multiple Container Packing Problem. Proceeding of the 14th ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, San Antonio, 28 February-2 March 1999, 291-296.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/298151.298354 - 36. Glover, F. (1975) Surrogate Constraint Duality in Mathematical Programming. Operations Reserach, 23, 434-451.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/opre.23.3.434 - 37. Hanafi, S. and Féville, A. (1998) An Efficient Tabu Search Approach for the 0-1 Multidimensional Kanpsack Problem. European Journal of Operational Research, 106, 659-675.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(97)00296-8 - 38. Gavish, B. and Pirkul, H. (1985) Efficient Algorithms for Solving Multiconstraint Zero-One Knapsack Problems to Optimality. Mathematical Programming, 31, 78-105.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02591863 - 39. Rothlauf, F. and Goldberg, D.E. (2003) Redundant Representation in Evolutionary Computation. Evolutionary Computation, 11, 381-415.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/106365603322519288 - 40. Hinterding, R. (1999) Representation, Constraint Satisfaction and the Knapsack Problem. Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Washington DC, 6-9 July 1999, 1286-1292.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/CEC.1999.782591

NOTES

1http://people.brunel.ac.uk/~mastjjb/jeb/info.html.

2This suite can be downloaded from http://hces.bus.olemiss.edu/tools.html.