Advances in Pure Mathematics

Vol.06 No.05(2016), Article ID:65743,11 pages

10.4236/apm.2016.65024

Inference in the Presence of Likelihood Monotonicity for Polytomous and Logistic Regression

John E. Kolassa

Department of Statistics and Biostatistics, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ, USA

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 21 November 2015; accepted 19 April 2016; published 22 April 2016

ABSTRACT

This paper addresses the problem of inference for a multinomial regression model in the presence of likelihood monotonicity. This paper proposes translating the multinomial regression problem into a conditional logistic regression problem, using existing techniques to reduce this conditional logistic regression problem to one with fewer observations and fewer covariates, such that probabilities for the canonical sufficient statistic of interest, conditional on remaining sufficient statistics, are identical, and translating this conditional logistic regression problem back to the multinomial regression setting. This reduced multinomial regression problem does not exhibit monotonicity of its likelihood, and so conventional asymptotic techniques can be used.

Keywords:

Polytomous Regression, Likelihood Monotonicity, Saddlepoint Approximation

1. Introduction

We consider the problem of inference for a multinomial regression model. The sampling distribution of responses for this model, and, in turn, its likelihood, may be represented exactly by a certain conditional binary regression model.

Some binary regression models and response variable patterns give rise to likelihood functions that do not have a finite maximizer; instead, there exist one or more contrasts of the parameters such that as this contrast is increased to infinity, the likelihood continues to increase. For these models and response patterns, maximum likelihood estimators for regression parameters do not exist in the conventional sense, and so monotonicity in the likelihood complicates estimation and testing of binary regression parameters. Because of the association between binary regression and multinomial regression, multinomial regression methods inherit this difficulty. In particular, methods like those suggested by [1] , using higher-order asymptotic probability approximations like those of [2] , are unavailable in these cases, since the methods of [2] use values of the maximized likelihood, both with the parameter of interested fixed and allowed to vary, and use the second derivatives of the likelihood at these two points.

[3] provides a method for diagnosing and adjusting for likelihood monotonicity for conditional testing in binary regression models. This manuscript extends this method to facilitate estimation in multinomial regression, for approximate inference, and in particular makes practical the use of the approximation of [2] .

Section 2.1 reviews binary and multinomial regression models, and relations between these models that let one swap back and forth between them. Section 2.2 reviews conditional inference for canonical exponential families. Section 2.3 reviews techniques of [3] for performing conditional inference in the presence of likelihood monotonicity for binary regression, makes a suggestion for improving the efficiency of this earlier technique, and expands on its implication for estimation. Section 2.4 reviews some existing techniques for addressing likelihood monotonicity. Section 2.5 develops new techniques for detection of likelihood monotonicity in multinomial regression models, and explores discusses non-uniqueness of maximum likelihood estimates in this case. Section 3 applies the techniques of Section 2.5 to some examples. Section 4 presents some conclusions.

2. Methods and Materials

This section describes existing methods used in cases of likelihood monotonicity in multinomial models, and presents new methods for addressing these challenges.

2.1. Multinomial and Logistic Regression Models

Methods will be developed in this manuscript to address both multinomial and binary regression models. In this section, relationships between these models are made explicit.

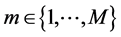

Consider first the multinomial distribution. Suppose that M multinomial trials are observed; for trial , one of

, one of  alternatives is observed, with alternative

alternatives is observed, with alternative  having probability

having probability

(1)

(1)

Here  (for

(for  representing the real numbers and K a positive integer) are covariate vectors associated with each of the alternatives, and

representing the real numbers and K a positive integer) are covariate vectors associated with each of the alternatives, and  are the number of replicates with this covariate pattern. These probabilities depend only on on the differences between

are the number of replicates with this covariate pattern. These probabilities depend only on on the differences between  and

and  for

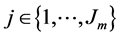

for ; without loss of generality we will take

; without loss of generality we will take , treating the last category as a baseline. Let

, treating the last category as a baseline. Let  be independent random variables such that

be independent random variables such that  and let

and let  if

if  and

and

Let

The binary regression model is similar; let

for

where

for

The binary regression model can be recast as a multinomial regression model. Furthermore, the multinomial regression model may be expressed as a conditional binary regression model. Suppose that (1) and (2) hold. Let

are 0. Let

with

2.2. Conditional Inference

The model for

for

When

Then

least

The cumulative probabilities implicit in (9) may be approximated as

for

logarithm of the likelihood (in the multinomial regression case, given by (2)),

and

Similar techniques may be applied to the multinomial regression model, with

2.3. Infinite Estimates

This section reviews and clarifies techniques for inference in the presence of monotonicity in the logistic regression likelihood (4) given by [3] , who built on results of [4] - [6] , and [7] . Choose

for

Theorem 1. Suppose that random vectors

with

where

Furthermore, the conditional probabilities are the same as those arising if observations with positive entries in

The matrix

2.4. Other Approaches

Suppose that there exists a vector

with strict inequality holding in place of at least one of the inequalities. Then the likelihood

Bias-correction is possible for maximum likelihood estimators [8] , and may be employed in this type of cituation [9] . Estimates with this correction applied are the same as those maximizing the posterior density of the parameters under the invariant prior of [10] , in which the likelihood function is multiplied by the square root of the determinant of the information matrix; this is equivalent to maximizing a penalized likelihood. That is, if

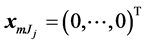

Standard errors may be calculated from the second derivative of the unpenalized log likelihood [8] ; one could also calculate standard errors from the second derivative of the penalized log likelihood [11] . This second approach is used in this manuscript for comparison purposes, and so the asymptotic confidence intervals considered below for

Here the superscript 11 on

The approach using Jeffreys’ prior to penalize the likelihood has some disadvantages. The union of all possible confidence intervals resulting as the penalized estimator plus or minus a multiple of the standard error has a finite range, and so the confidence region procedure as described above has vanishing coverage probability for large values of the regression parameter.

2.5. Estimation

We investigate the behavior of maximum likelihood estimates in the multinomial regression model (2). Maximizers for both the original likelihood and for the likelihood of the distribution of sufficient statistics of interest (6) or (3) conditional on the remaining canonical sufficient statistics are considered. Conditional probabilities arising from the logistic regression model (4) are of form (2), and so may also be handled as below.

Consider the occurrence of infinite estimates for model (2). Denote the sample space for the

Corollary 1. Unique finite maximizers of the likelihood given in (2) exist if and only if

is greater than zero.

Proof. If

Suppose that

given by

Now take

One may determine whether such a c exists by maximizing c over non-negative c and

The second corollary follows directly from Theorem 1.

Corollary 2. Suppose that the random vector

If either Corollary 1 or Corollary 2 indicates that finite maximum likelihood estimators do not exist, one might look for estimators in the extended real numbers

[9] motivates the penalized likelihood approach for estimation in order to reduce biases of estimators. Since the standard approach to estimation in this case allows for infinite estimators, expectations of the conventional estimators do not exist, and so bias is an inappropriate criterion for our estimator. In what follows, the median bias (that is, the difference between the median of the sampling distribution of the estimator, minus the true value of the parameter) is used to assess quality of estimation.

3. Results

The following date reflects the results of a randomized clinical trial testing the effectiveness of a screening procedure designed to reduce hepatitis transmission in blood transfusions [9] [14] . The clinical trial was divided into two time periods. The data may be summarized as in Table 1 [9] . Hepatitis outcome is modeled as a function of period (

A log linear model is used, implying a comparison between each of the two hepatitis categories and the third no-disease baseline category. Each of these comparisons involves parameters for I, S, T, and

The lack of any Hepatitis C cases among the treated individuals in the early period gives rise to infinite estimate for the T and

In this simple case, closed-form maximizers of (2) under the alternative hypothesis exists, since the alternative hypothesis may be viewed as a saturated model for a

The sampling distribution of the sufficient statistics is available in under the hypothesis that all six S, T, and

Table 1. Hepatitis data.

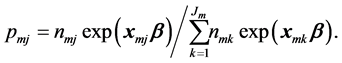

Inference on the two

Figure 1. Median bias.

Figure 2. Coverage for various two-sided confidence interval procedures.

A second example concerns polling data related to British general elections [16] . The data set investigated here represents a subset of voters in one of eight geographic areas (London North, London South, Greater Manchester, Merseyside, South Yorkshire, Tyne and Wear, West Midlands, and West Yorkshire), and includes survey respondents who provided their ages and an informative response to a question measuring age at which education was finished (coded as 1 = 15 or younger, 2 = 16, 3 = 17, 4 = 18, 5 = 19 or older), and reported a party of preference, and party of intended vote in the 2005 election. Three parties (Conservative, Labor, and Liberal Democrat) were reported as answers to these last two questions. The resulting data set included 67 individuals. We model voting choice as a function of usual party preference and education, treated as an ordinal variable. In this case,

The null distribution of this data set cannot be trivially expressed as the independence distribution for a contingency table. One might enumerate the conditional sample space for the sufficient statistics vectors of (3), and the associated conditional probabilities [17] ; this calculation, however, took over 16 hours to complete when coded in FORTRAN 90 and run on a 2.6 GHz processor with a 1 GB cache and 8 GB of memory, and is too intensive for routine use. This condition distribution is tabulated in Table 4. Figure 3 shows the median bias for estimates [8] and the proposed method, explicitly recognizing infinite estimates associated with the extreme points in the conditional sample space. While the median bias for both estimators is poor, the corrected estimator generally performed better than the uncorrected estimator, as reported by other authors.

This manuscript is primarily concerned with producing confidence intervals. One might use the asymptotic intervals calculated using the penalized likelihood (17), or (9), with probabilities calculated exactly using Table 4 in conjunction with (8) and the nominal level adjusted using (10), or (9), with cumulative probabilities approximated (in the present case using a double saddlepoint conditional distribution function approximation of [2] ). Table 5 shows the resulting confidence intervals, and Figure 4 shows the coverage of these intervals. As

Table 2. Median bias in two estimation methods for hepatitis data.

Table 3. Minimal coverage for two confidence interval methods for the hepatitis data.

Table 4. Probabilities

Table 5. Two-sided confidence intervals for the effect of education on voting for labor candidate.

Figure 3. Median bias.

Figure 4. Coverage for various two-sided confidence interval procedures.

noted above, coverage for the asymptotic interval is zero for

Figure 5. Conditional sample space for education effects.

fails to cover some values of

In practice, Table 4, and hence the exact intervals in Table 5 and Figure 4, are not computationally feasible. The saddlepoint confidence intervals are computationally feasible, but when the entire sufficient statistic vector lies on the boundary of the convex hull of the sufficient statistic sample space, the methods of Corollary 2 are required to apply these methods.

One can also consider simultaneous inference on both education parameters. Figure 5 displays the conditional sample space for these the sufficient statistic vectors for the effects on education on preference for Labor and Liberal Democratic Candidates. Corollary 1 indicates that the observed sufficient statistic vector (indicated by W in the figure) corresponds to finite estimates. Note that the point indicated by Δ is an example of one corresponding to ambiguous estimates; the parameter associated with the first component is clearly estimated as

4. Conclusion

This paper presents an algorithm for converting a multinomial regression problem that features nuisance parameters estimated at infinity to a similar problem in which all nuisance parameters have finite estimates; this conversion is such that the distribution of a sufficient statistic associated with the parameter of interest, conditional on all other sufficient statistics, remains unchanged. These conditional probabilities in the reduced model may be approximated using standard asymptotic techniques to yield confidence intervals with coverage behavior superior to those that arise from, for example, asymptotics derived from the likelihood after penalizing using Jeffreys’ prior.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by NSF grant DMS 0906569.

Cite this paper

John E. Kolassa, (2016) Inference in the Presence of Likelihood Monotonicity for Polytomous and Logistic Regression. Advances in Pure Mathematics,06,331-341. doi: 10.4236/apm.2016.65024

References

- 1. Davison, A.C. (1988) Approximate Conditional Inference in Generalized Linear Models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 50, 445-461.

- 2. Skovgaard, I. (1987) Saddlepoint Expansions for Conditional Distributions. Journal of Applied Probability, 24, 875-887.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3214212 - 3. Kolassa, J.E. (1997) Infinite Parameter Estimates in Logistic Regression, with Application to Approximate Conditional Inference. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 24, 523-530.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9469.00078 - 4. Albert, A. and Anderson, J.A. (1984) On the Existence of Maximum Likelihood Estimates in Logistic Regression Models. Biometrika, 71, 1-10.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/biomet/71.1.1 - 5. Jacobsen, M. (1989) Existence and Unicity of Miles in Discrete Exponential Family Distributions. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 16, 335-349.

- 6. Clarkson, D.B. and Jennrich, R.I. (1991) Computing Extended Maximum Likelihood Estimates for Linear Parameter Models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 53, 417-426.

- 7. Santner, T.J. and Duffy, D.E. (1986) A Note on A. Albert and J. A. Anderson’s Conditions for the Existence of Maximum Likelihood Estimates in Logistic Regression Models. Biometrika, 73, 755-758.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/biomet/73.3.755 - 8. Firth, D. (1993) Bias Reduction of Maximum Likelihood Estimates. Biometrika, 80, 27-38.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/biomet/80.1.27 - 9. Bull, S.B., Mak, C. and Greenwood, C.M. (2002) A Modified Score Function Estimator for Multinomial Logistic Regression in Small Samples. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 39, 57-74.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9473(01)00048-2 - 10. Jeffreys, H. (1961) Theory of Probability. 3rd Edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- 11. Heinze, G. and Schemper, M. (2001) A Solution to the Problem of Monotone Likelihood in Cox Regression. Biometrics, 57, 114-119.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2001.00114.x - 12. Barndorff-Nielsen, O.E. (1978) Information and Exponential Families in Statistical Theory. Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics. Wiley, New York.

- 13. Robinson, J. and Samonenko, I. (2012) Personal Communication.

- 14. Blajchman, M., Bull, S. and Feinman, S., C.P.-T.H.P.S. (1995) Group Post-Transfusion Hepatitis: Impact of Non-a, Non-b Hepatitis Surrogate Tests. The Lancet, 345, 21-25.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91153-7 - 15. Pagano, M. and Halvorsen, K.T. (1981) An Algorithm for Finding the Exact Significance Levels of r × c Contingency Tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 76, 931-934.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2287590 - 16. Sanders, D.J., Whiteley, P.F., Clarke, H.D., Stewart, M. and Winters, K. (2007) The British Election Study. University of Essex.

- 17. Hirji, K.F. (1992) Computing Exact Distributions for Polytomous Response Data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 87, 487-492.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1992.10475230