Advances in Pure Mathematics

Vol.3 No.9(2013), Article ID:40886,10 pages DOI:10.4236/apm.2013.39097

Global Properties of Evolutional Lotka-Volterra System

1Department of Mathematics, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Higashi-Hiroshima, Japan

2Research Center for Environmental Risk, National Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba, Japan

Email: yoshinom@hiroshima-u.ac.jp, ytanaka@nies.go.jp

Copyright © 2013 Masafumi Yoshino, Yoshinari Tanaka. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2013 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Masafumi Yoshino, Yoshinari Tanaka. All Copyright © 2013 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

Received November 9, 2013; revised December 9, 2013; accepted December 15, 2013

Keywords: Lotka-Volterra System; Global Dynamics; Evolution

ABSTRACT

We will study global properties of evolutional Lotka-Volterra system. We assume that the predatory efficiency is a function of a character of species whose evolution obeys a quantitative genetic model. We will show that the structure of a solution is rather different from that of a non-evolutional system. We will analytically show new ecological features of the dynamics.

1. Introduction

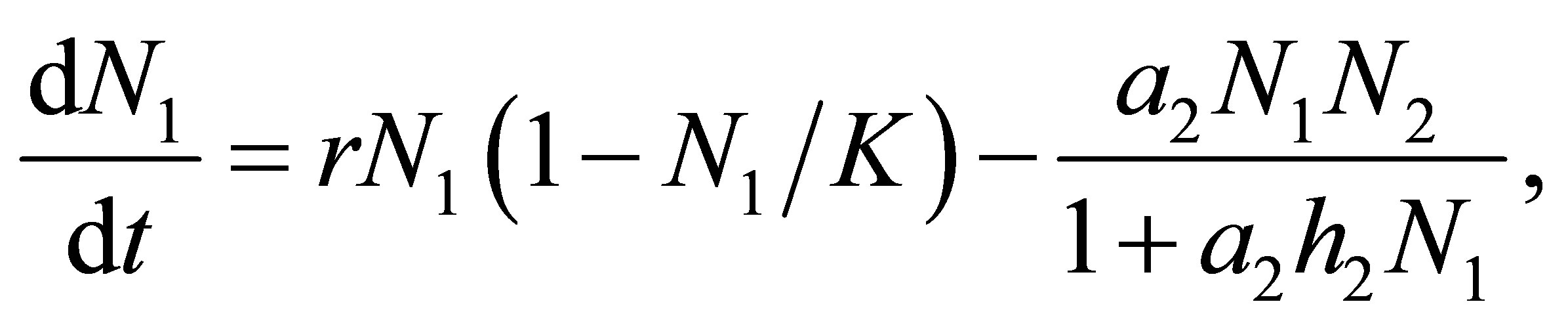

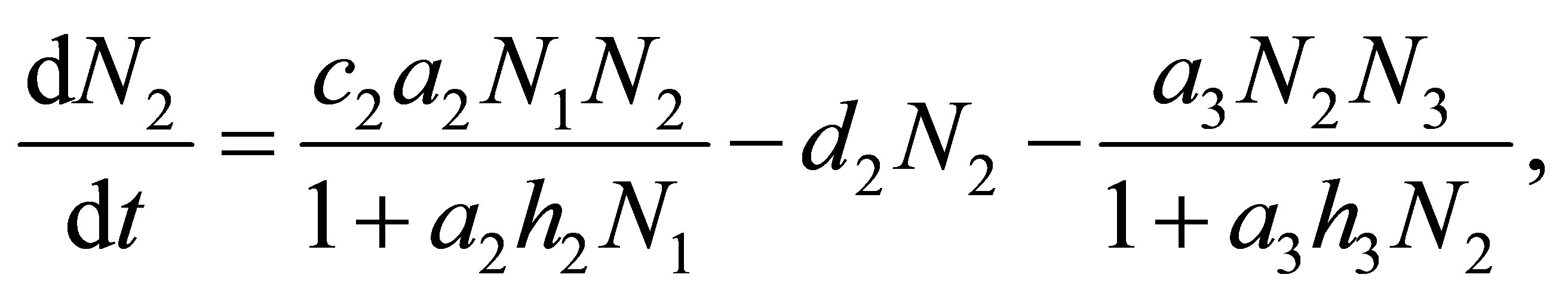

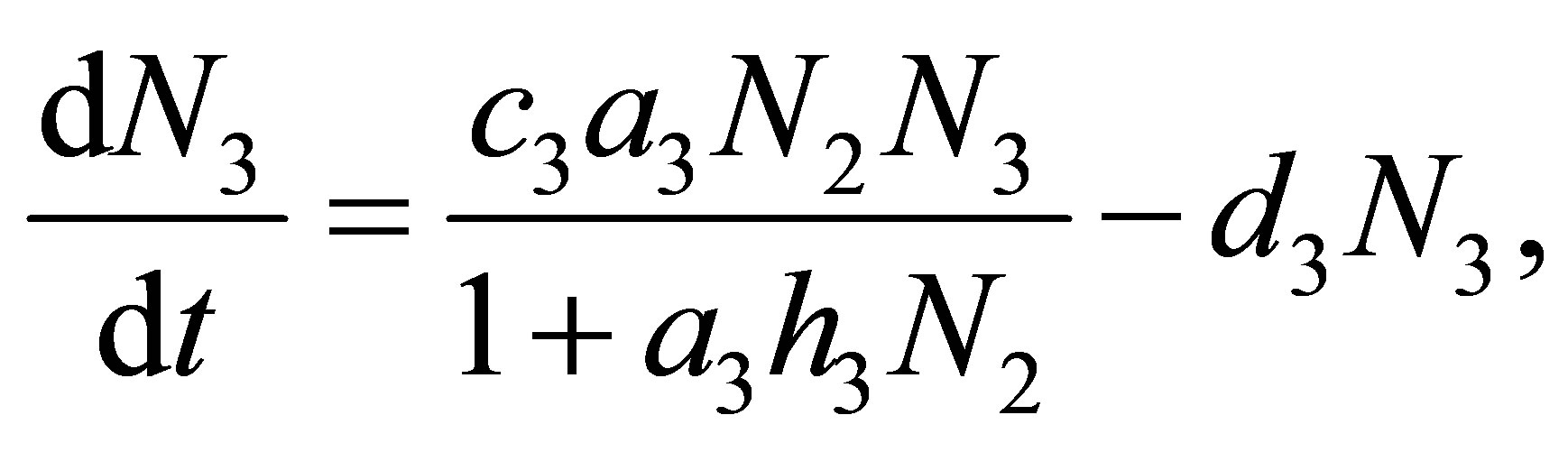

In this paper, we study global behavior of an evolutional Lotka-Volterra system for three species

(1.1)

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.3)

(1.3)

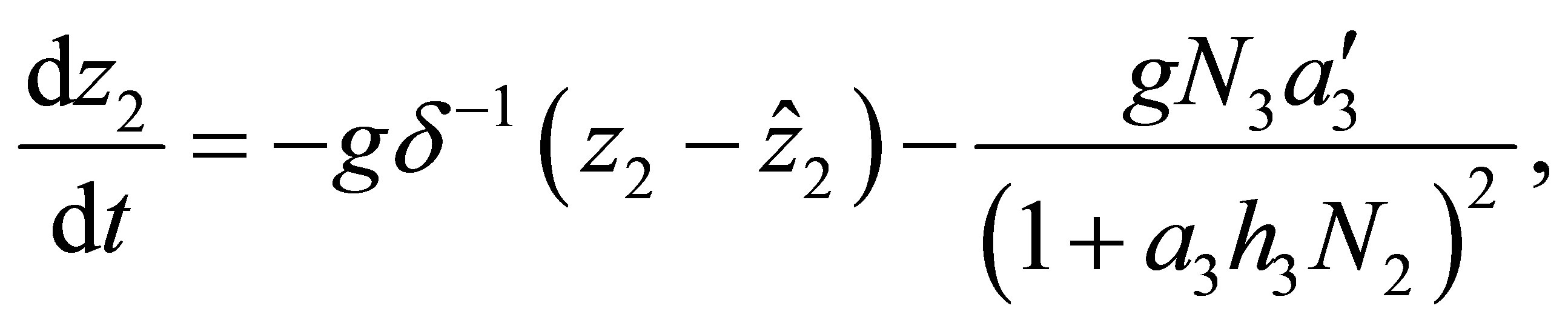

(1.4)

(1.4)

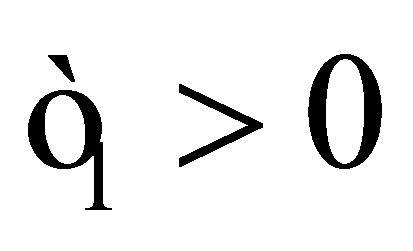

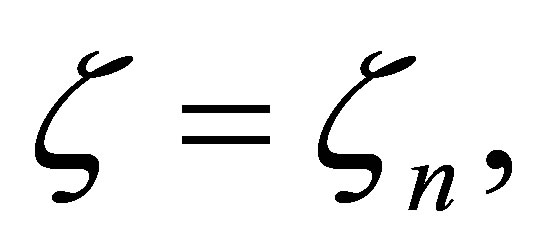

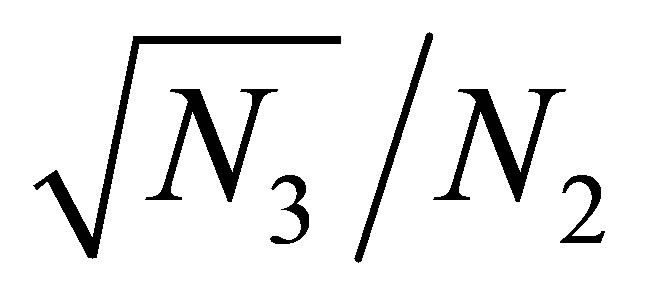

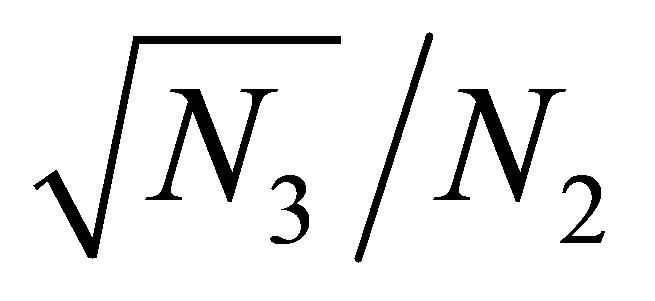

for the unknown quantities  and

and  which are the population of jth species and the mean character value of the second species, respectively. Here

which are the population of jth species and the mean character value of the second species, respectively. Here  are certain constants, and

are certain constants, and  and

and  are death rate of the second and the third species, respectively. The quantities

are death rate of the second and the third species, respectively. The quantities  and

and  are the predatory efficiency of the second and the third species, respectively. The number

are the predatory efficiency of the second and the third species, respectively. The number  is the mean character value of the second species with minimal cost. The quantity

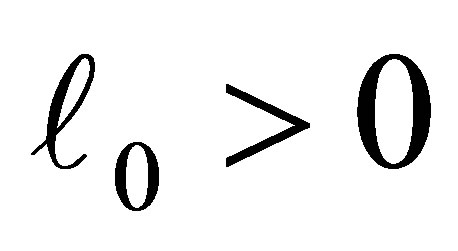

is the mean character value of the second species with minimal cost. The quantity  is the additive genetic variance and

is the additive genetic variance and  is the cost of evolution, namely, if

is the cost of evolution, namely, if  decreases, then the cost increases.

decreases, then the cost increases.

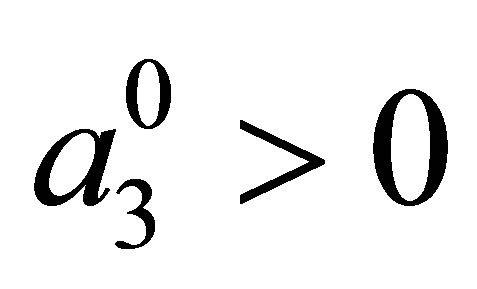

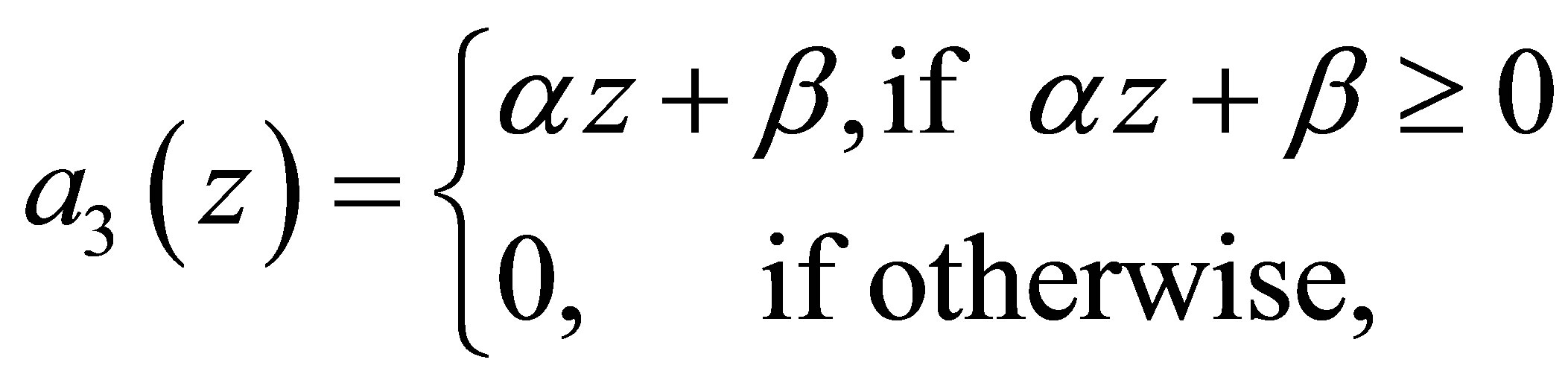

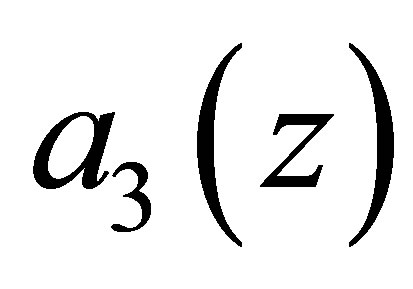

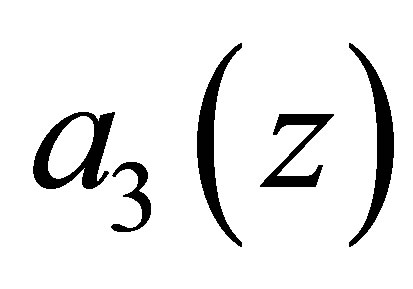

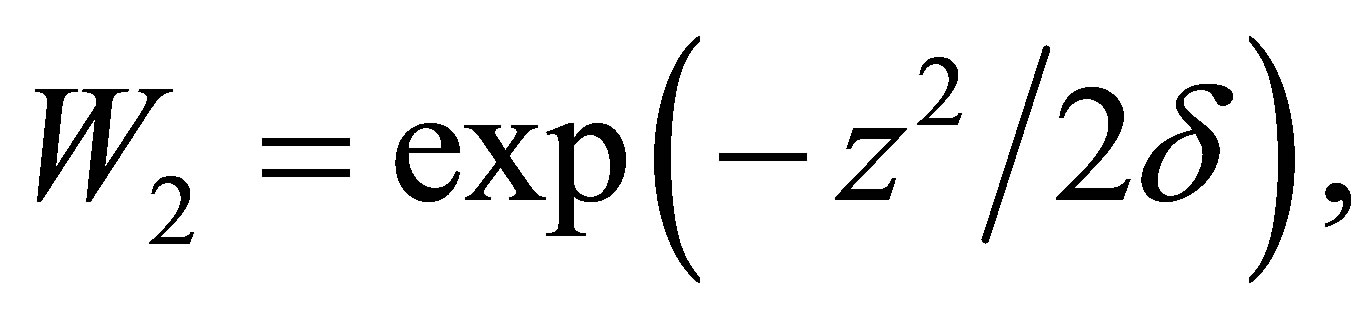

The effect of evolution is expressed in terms of (1.4) and the condition that the predatory efficiency  is given by

is given by

(1.5)

(1.5)

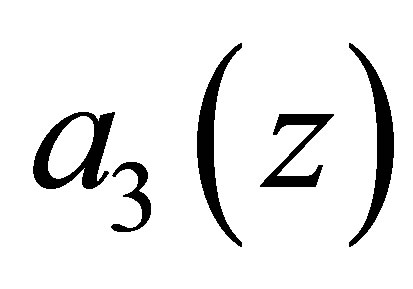

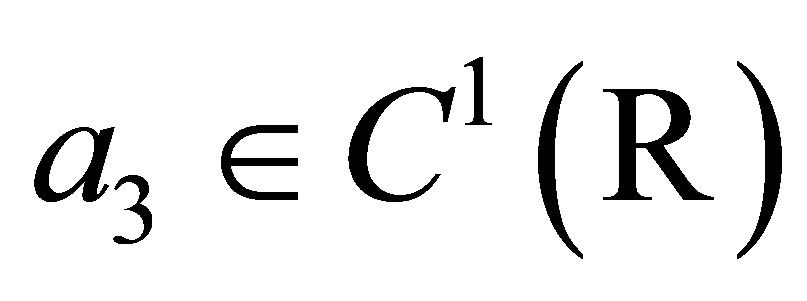

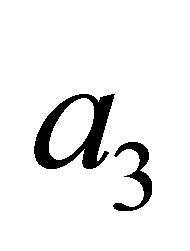

where  is a given constant and

is a given constant and  is a function of

is a function of . An example of a3 is given by (C.1) in Section 3. Equation (1.4) follows the quantitative genetical model (cf. [1-5]. See also Section 7). The evolutional Lotka-Volterra system for two species was studied in [3], where rather detailed numerical analysis was made. As for the system for three species, very little is known as to global behavior of solutions even from a numerical point of view. In this paper, we shall make the analytical study of evolutional Lotka-Volterra model for three species and show several new phenomena caused by evolution.We also refer [6] as to non-evolutional case.

. An example of a3 is given by (C.1) in Section 3. Equation (1.4) follows the quantitative genetical model (cf. [1-5]. See also Section 7). The evolutional Lotka-Volterra system for two species was studied in [3], where rather detailed numerical analysis was made. As for the system for three species, very little is known as to global behavior of solutions even from a numerical point of view. In this paper, we shall make the analytical study of evolutional Lotka-Volterra model for three species and show several new phenomena caused by evolution.We also refer [6] as to non-evolutional case.

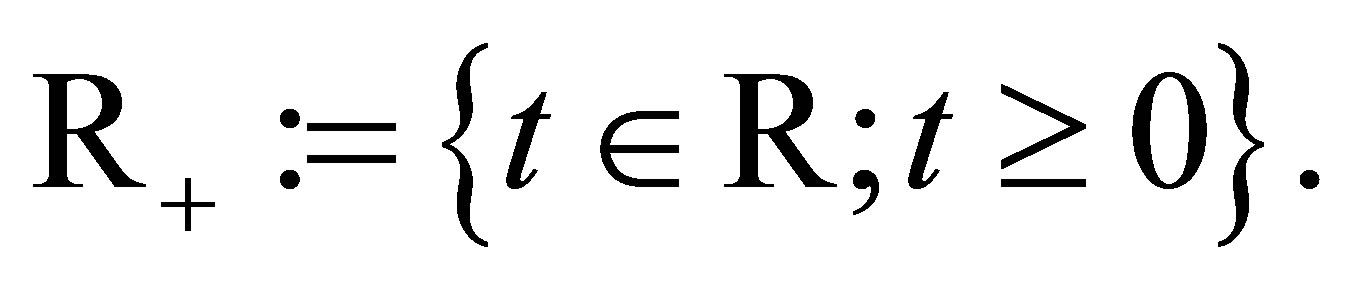

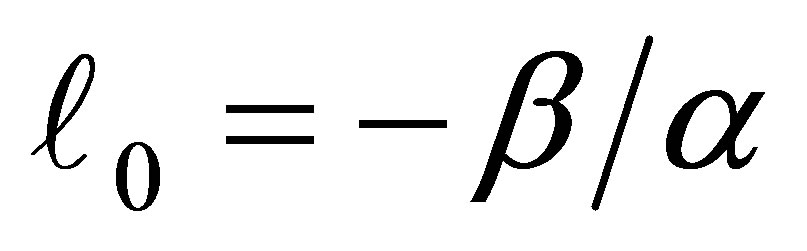

Let  Let

Let  and

and  and

and  be given. We first prove that (1.1)-(1.4) with the initial condition

be given. We first prove that (1.1)-(1.4) with the initial condition

(1.6)

(1.6)

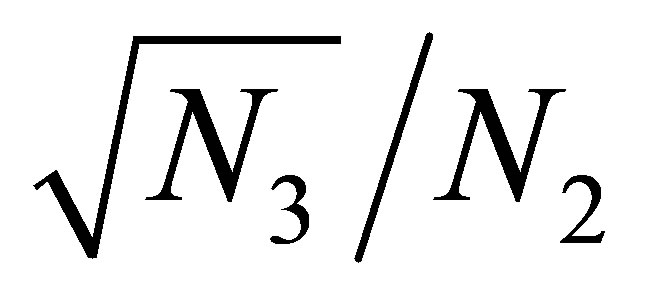

have unique smooth time global solution. (cf. Theorem 2). Then, in terms of estimate of a solution obtained in the proof of Theorem 2, we study behaviors of a solution related to evolution. Indeed, we will show that the behavior of a solution near the equilibrium point is different from those in the case of tea-cup attractors for a nonevolutional system. Namely, the decay of the predator  starts before the quantity

starts before the quantity  becomes small because the predatory efficiency a3 tends to zero, by evolution. We remark that although

becomes small because the predatory efficiency a3 tends to zero, by evolution. We remark that although  plays an important role in the non-evolutional system near equilibrium point, the quantity

plays an important role in the non-evolutional system near equilibrium point, the quantity  is crucial in the evolutional one. This is because the quantity

is crucial in the evolutional one. This is because the quantity  is related with the dynamics of evolution. We remark that the effect of evolution in our system is intermittent in the sense that in some subdomain of the phase space flactuations of pray

is related with the dynamics of evolution. We remark that the effect of evolution in our system is intermittent in the sense that in some subdomain of the phase space flactuations of pray  occur as in the case of non-evolutional model, while in other subdomain, evolution stabilizes large fluctuations of

occur as in the case of non-evolutional model, while in other subdomain, evolution stabilizes large fluctuations of  and

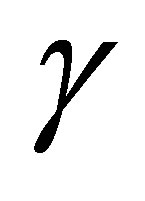

and . We also discuss the role of γ in (C.1), which is related with the sensitivity of evolution to the character bias

. We also discuss the role of γ in (C.1), which is related with the sensitivity of evolution to the character bias . (cf. Lemma 3 and Section 4 for the case of a linear efficiency). In Section 5, we study the uniform convergence of solutions of an evolutional system as the cost of evolution tends to infinity, i.e.,

. (cf. Lemma 3 and Section 4 for the case of a linear efficiency). In Section 5, we study the uniform convergence of solutions of an evolutional system as the cost of evolution tends to infinity, i.e.,  decreases to zero.

decreases to zero.

2. Time Global Solution

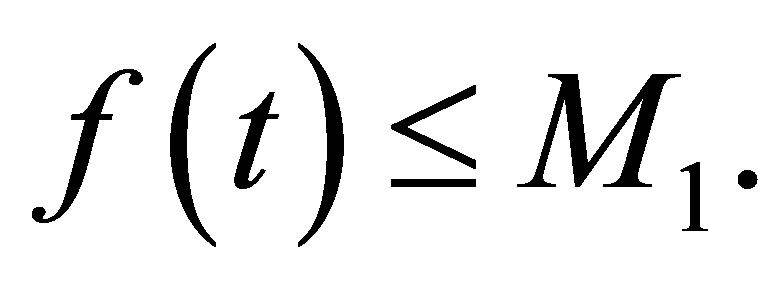

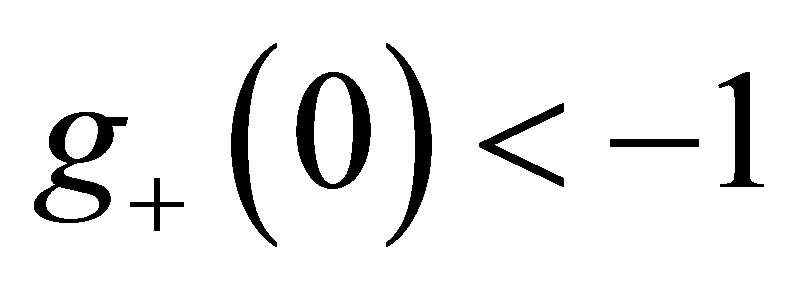

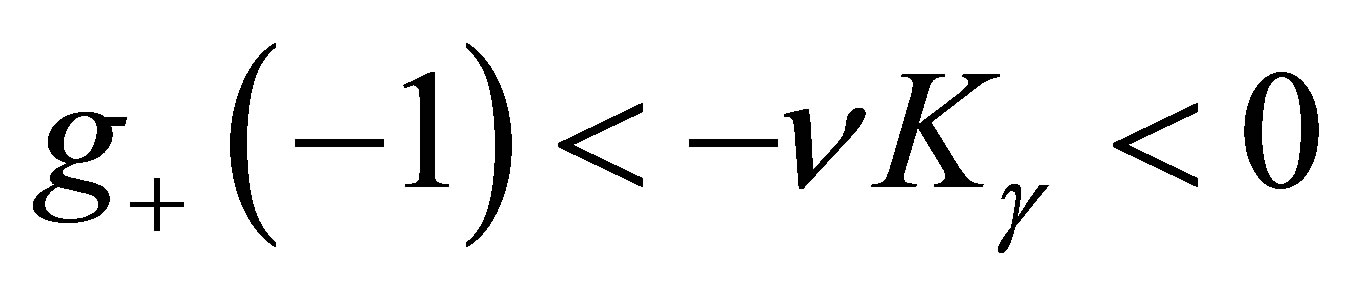

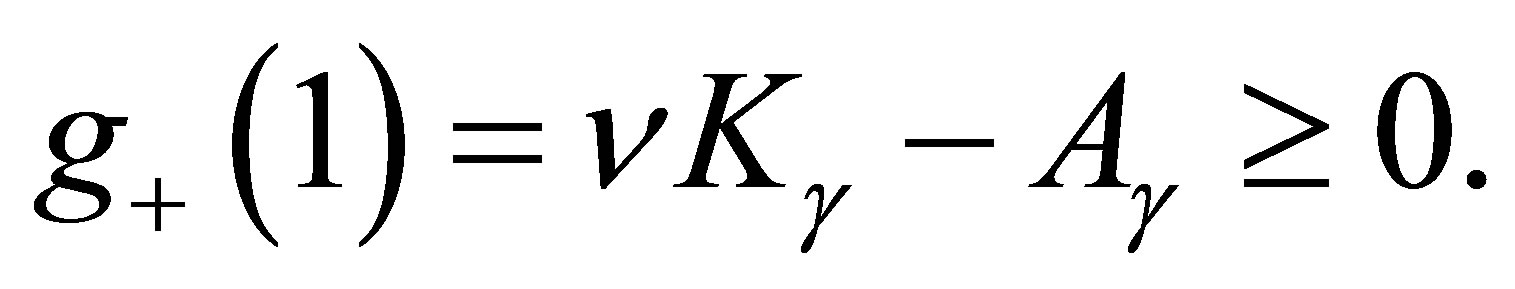

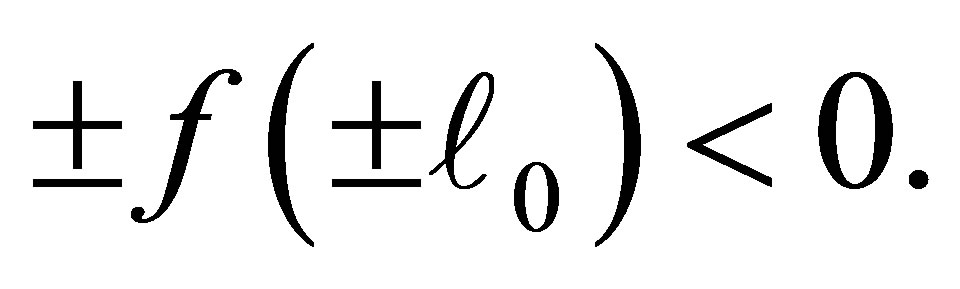

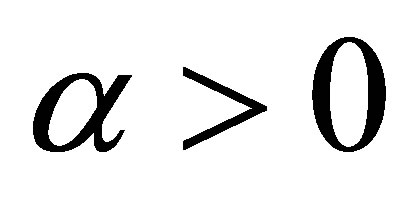

We shall study the global existence and uniqueness of a solution of the initial value problem. We assume that  is the twice continuously differentiable function which satisfies

is the twice continuously differentiable function which satisfies

(2.1)

(2.1)

for some . Moreover we suppose that there exist

. Moreover we suppose that there exist  and

and  such that

such that

(2.2)

(2.2)

The following local existence and uniqueness theorem is well known.

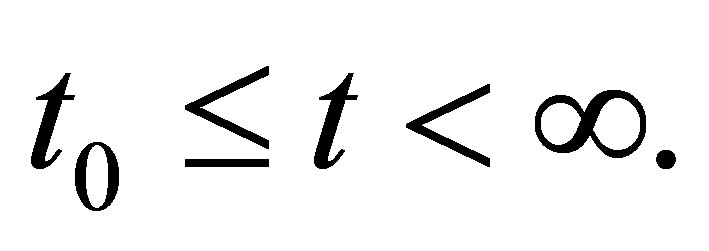

THEOREM 2.1. Assume (2.1) and (2.2). Then there exists a  such that the system of Equations (1.1)- (1.4) with the initial conditions (1.6) has a unique continuously differentiable solution

such that the system of Equations (1.1)- (1.4) with the initial conditions (1.6) has a unique continuously differentiable solution ,

,  in

in

In the following we study the existence of a global solution. We require the condition

(2.3)

(2.3)

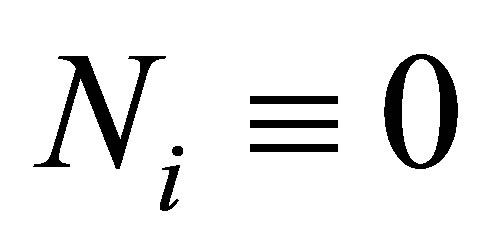

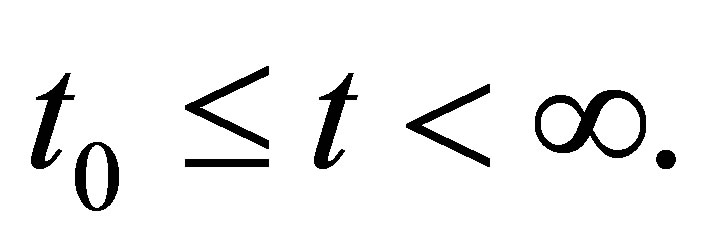

Remark. If  for some j, then, by the uniqueness, any solution of (1.1)-(1.4) satisfies

for some j, then, by the uniqueness, any solution of (1.1)-(1.4) satisfies . Hence it reduces to a system with less unknown quantities. Note that we avoid this case in (2.3).

. Hence it reduces to a system with less unknown quantities. Note that we avoid this case in (2.3).

We have

THEOREM 2.2. Suppose that (2.3) is satisfied. Then the system of Equations (1.1)-(1.4) with the initial condition (1.6) has a unique global solution in

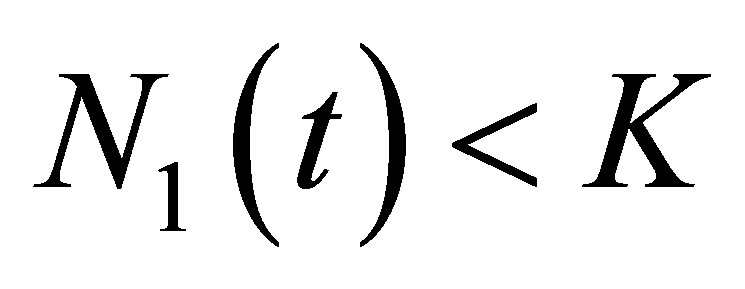

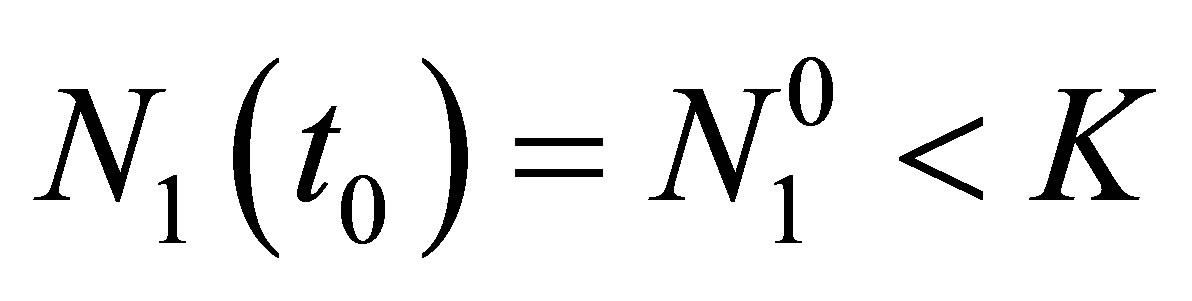

Proof. First we will show the apriori estimate  for all

for all . Suppose that this is not true. Then, by the continuity of

. Suppose that this is not true. Then, by the continuity of  and

and  in (2.3) we can take the smallest time

in (2.3) we can take the smallest time  such that

such that  Assume that

Assume that  If we set

If we set  in (1.1)-(1.4), then we have

in (1.1)-(1.4), then we have

(2.4)

(2.4)

By the local existence and uniqueness theorem, Equations (2.4) with the initial condition  has a unique solution. We denote the solution by

has a unique solution. We denote the solution by . Then (1.1)-(1.4) with the initial value

. Then (1.1)-(1.4) with the initial value  at

at  has a solution

has a solution  By the uniqueness of the solution we obtain

By the uniqueness of the solution we obtain  It follows that

It follows that  Because

Because  by (2.3), we have a contradiction. Hence we have

by (2.3), we have a contradiction. Hence we have  By the continuity of

By the continuity of  one may assume that

one may assume that  in a sufficiently small neighborhood of

in a sufficiently small neighborhood of . Then, the second term in the right hand side of (1.1) satisfies

. Then, the second term in the right hand side of (1.1) satisfies  in a sufficiently small neighborhood of

in a sufficiently small neighborhood of  On the other hand, since

On the other hand, since  can be made arbitrarily small by taking a neighborhood of small, it follows that

can be made arbitrarily small by taking a neighborhood of small, it follows that  there. Hence

there. Hence  is a decreasing function. This contradicts to

is a decreasing function. This contradicts to  Therefore, there is not

Therefore, there is not  such that

such that  which shows the desired estimate.

which shows the desired estimate.

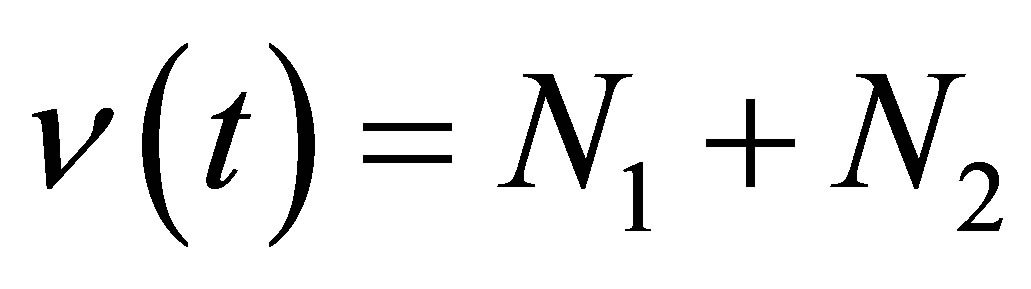

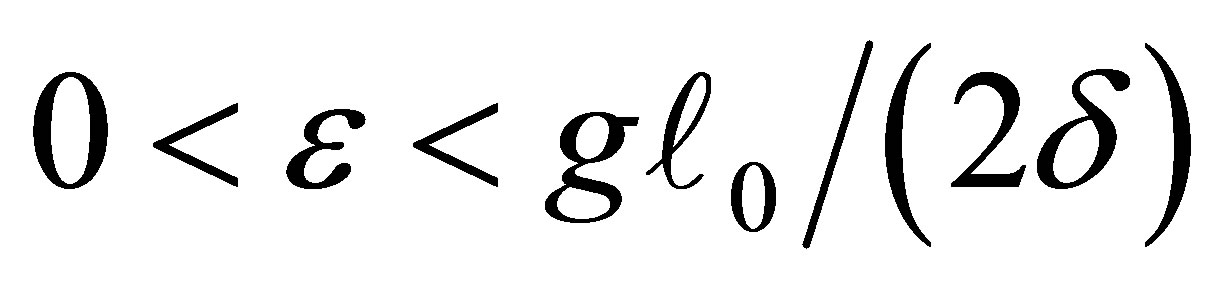

Next we will estimate N2 from the above. Take  that

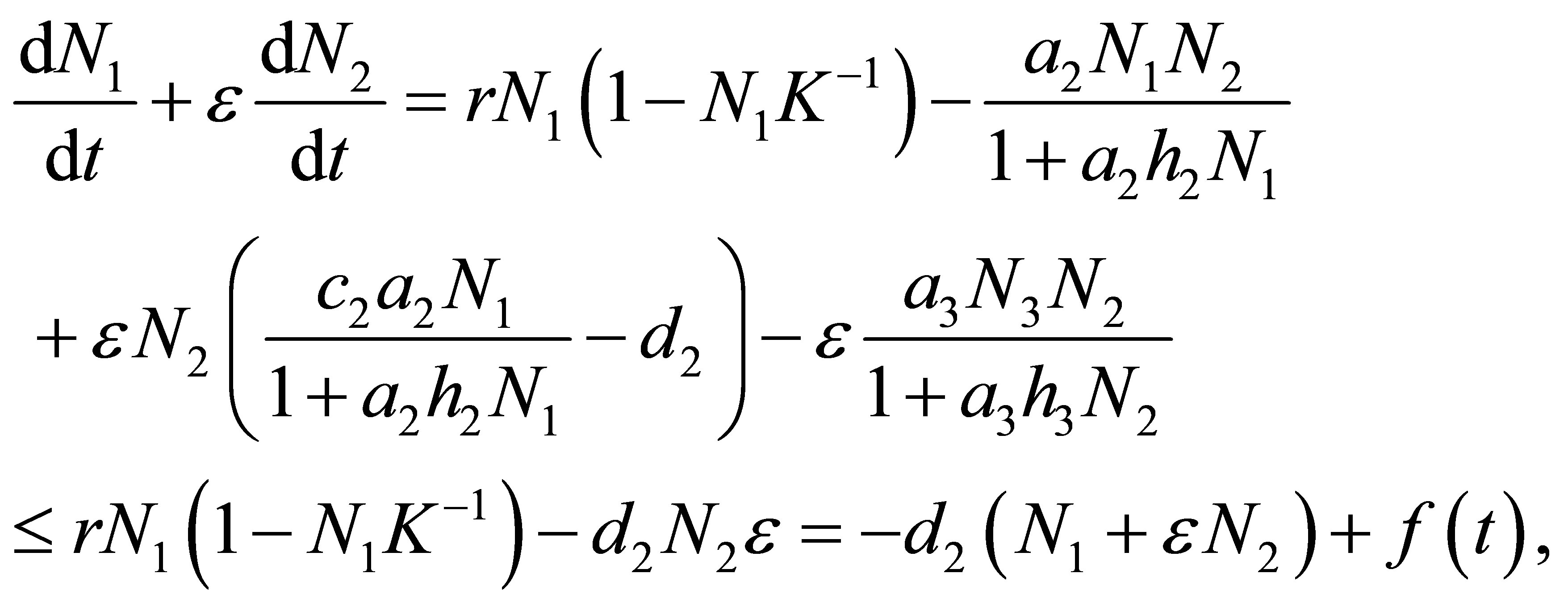

that  and add ε times (1.2) to (1.1). Then we have

and add ε times (1.2) to (1.1). Then we have

(2.5)

(2.5)

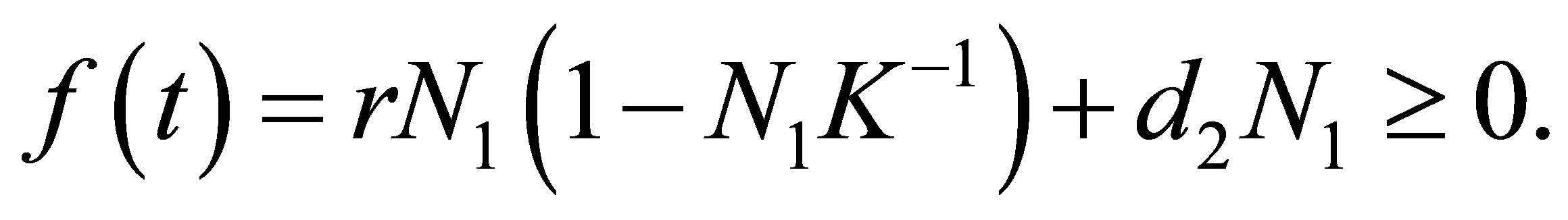

where

Hence, by setting  we obtain

we obtain

(2.6)

(2.6)

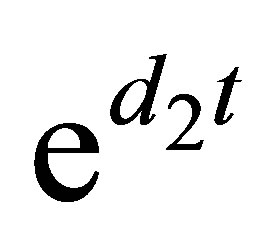

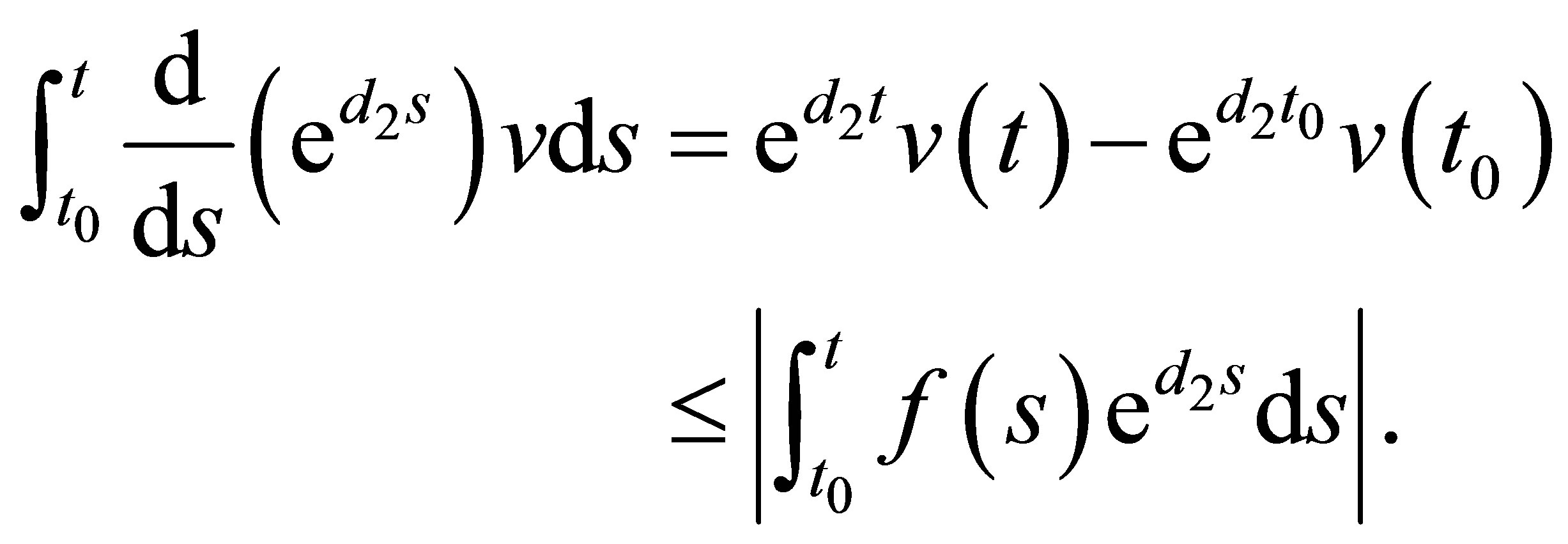

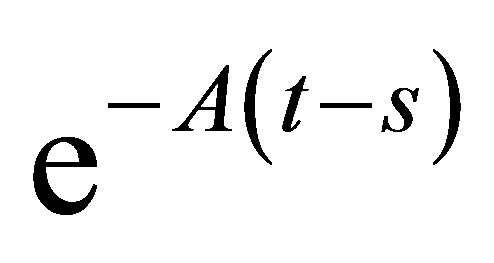

Multiplying  to both sides, and integrating from

to both sides, and integrating from  to

to  we obtain

we obtain

(2.7)

(2.7)

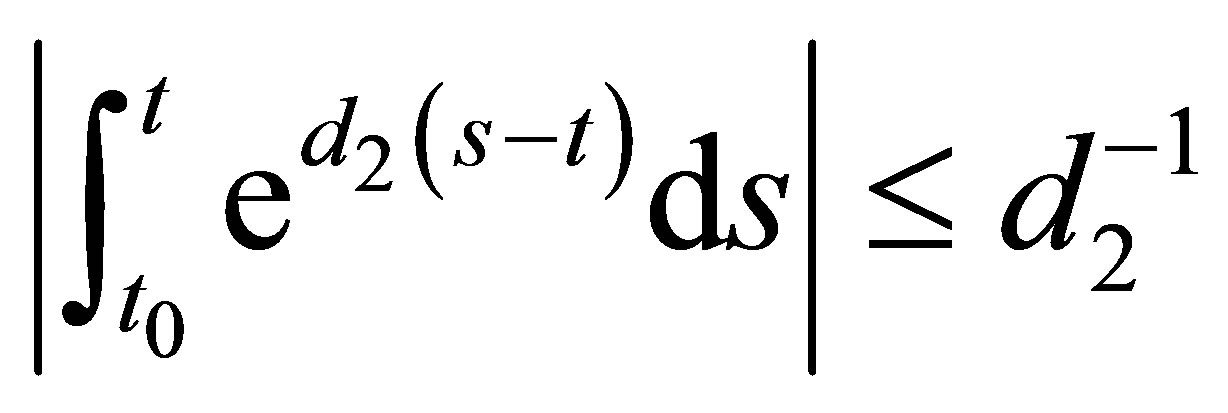

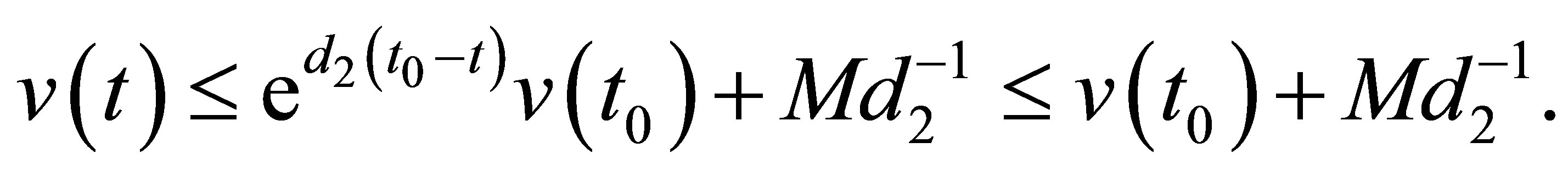

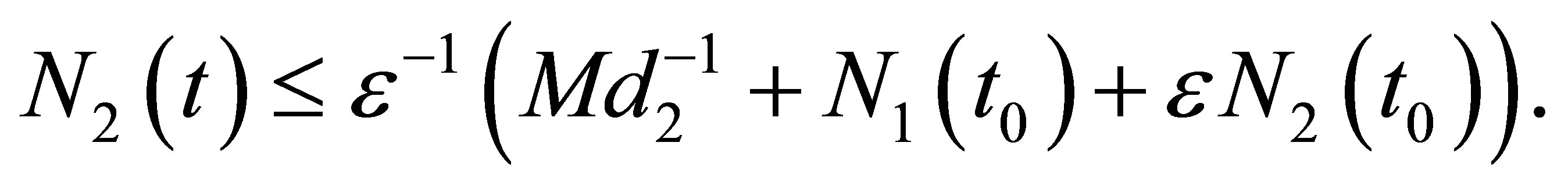

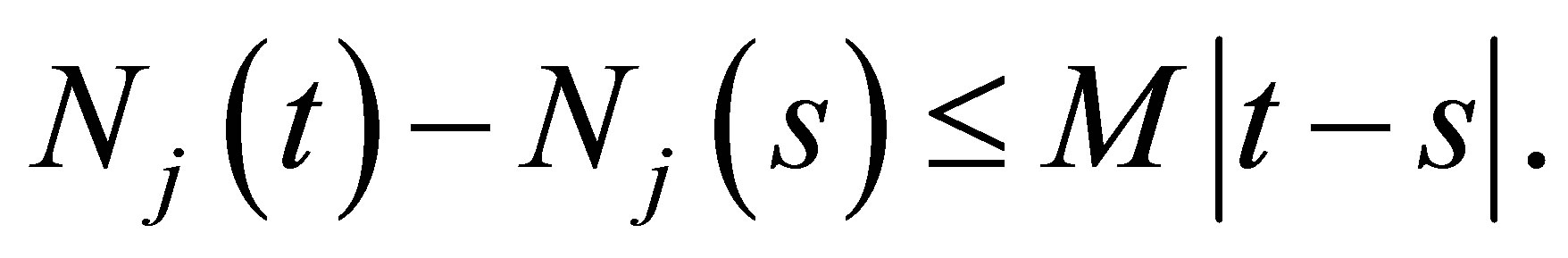

By the apriori estimate there exists M > 0 depending only on r, K and  such that

such that  Hence we have

Hence we have

Because , we obtain

, we obtain

(2.8)

(2.8)

It follows that, for

(2.9)

(2.9)

Note that the right hand side quantity depends on the initial value and the equation and depends neither on δ > 0 nor on g > 0.

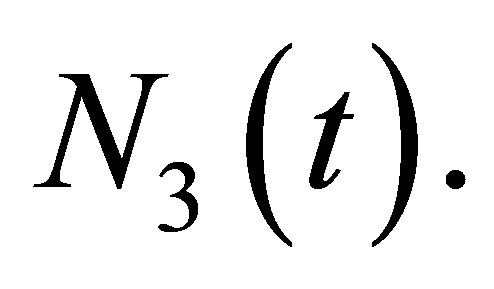

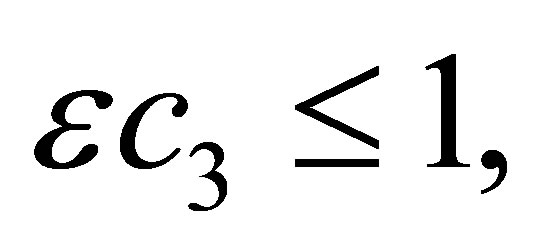

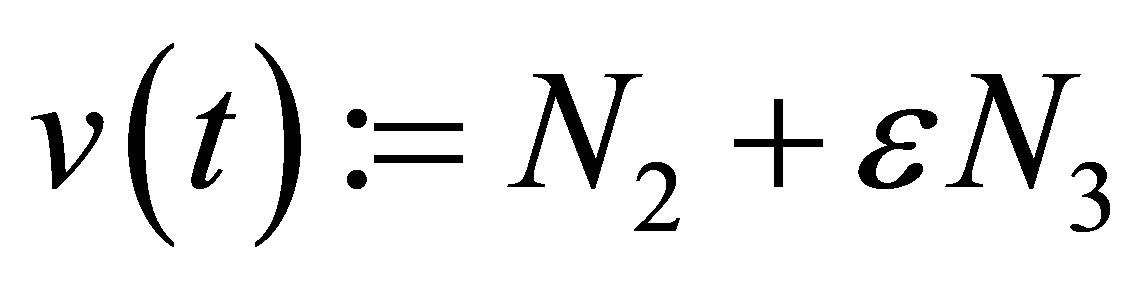

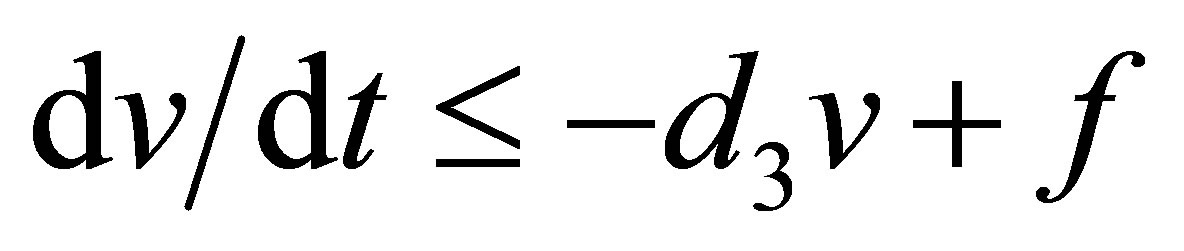

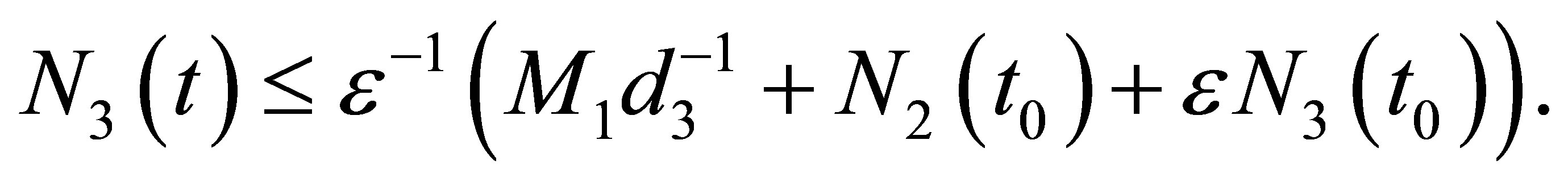

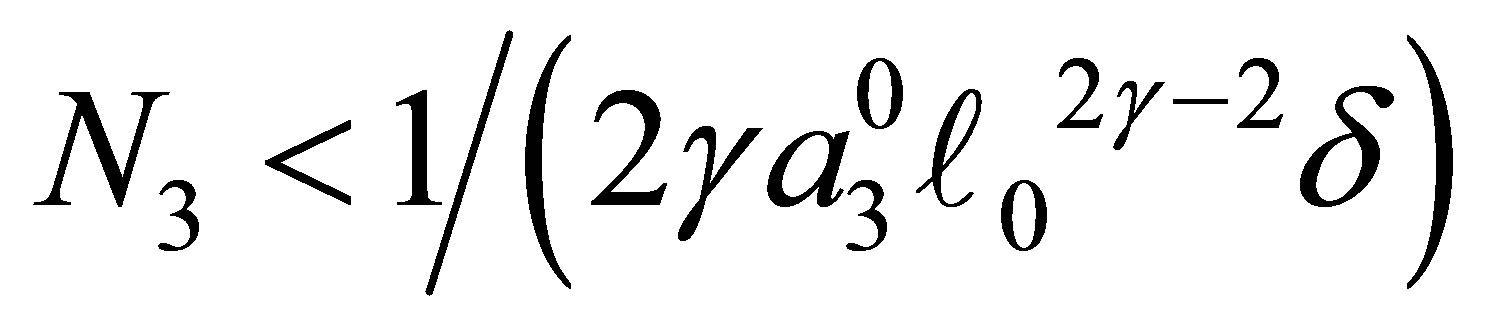

We make the same argument for  Take ε so that

Take ε so that  and add ε times (1.3) to (1.2). Then we have

and add ε times (1.3) to (1.2). Then we have

(2.10)

(2.10)

where

By setting  we obtain the equation

we obtain the equation . Because this equation has a similar form as in the case

. Because this equation has a similar form as in the case , we can choose a constant

, we can choose a constant  depending only on

depending only on  and the initial values so that

and the initial values so that  Then we argue in the same way and we obtain

Then we argue in the same way and we obtain

(2.11)

(2.11)

In view of the definition of v we have

(2.12)

(2.12)

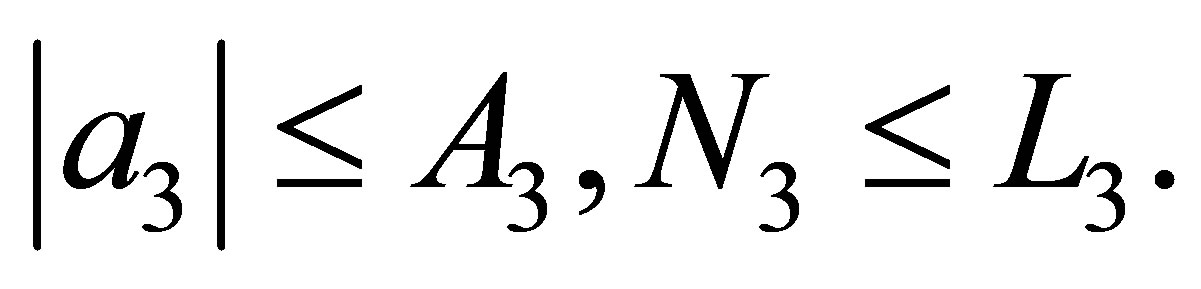

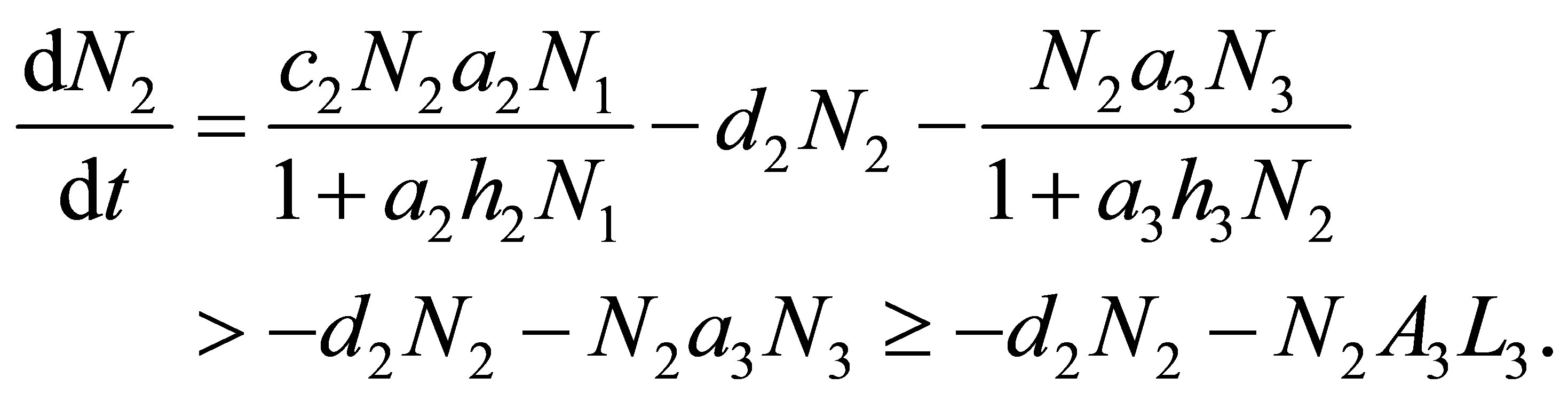

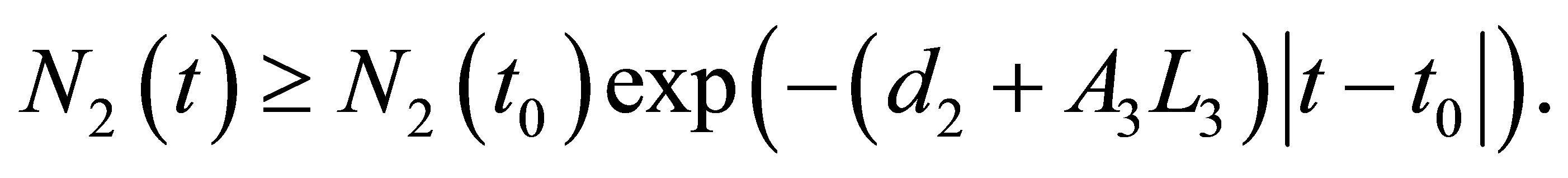

Next we will estimate  from the below. By the estimates of

from the below. By the estimates of  and

and  from the above there exists

from the above there exists  such that

such that  It follows that

It follows that

By integrating from  to t we obtain

to t we obtain

(2.13)

(2.13)

We will estimate N2 from the below. There exist constants  depending on the equation and the initial values such that,

depending on the equation and the initial values such that,  Hence we have

Hence we have

By integrating the inequality from  to t we obtain

to t we obtain

(2.14)

(2.14)

The estimate of  from the below can be shown by simple computations.

from the below can be shown by simple computations.

(2.15)

(2.15)

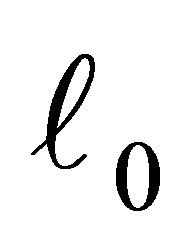

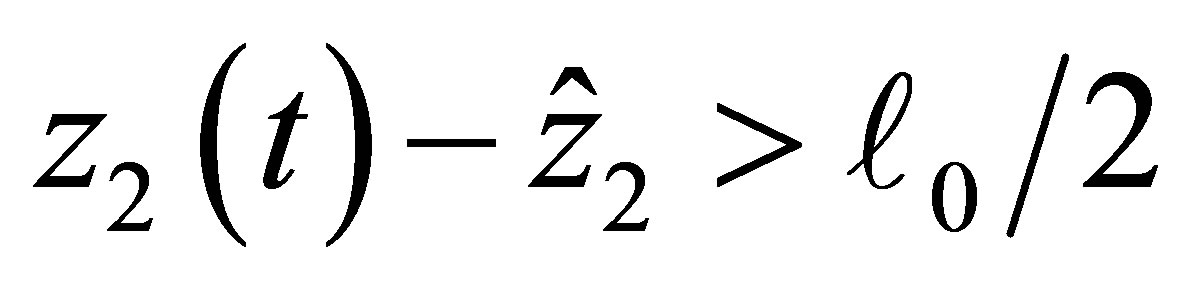

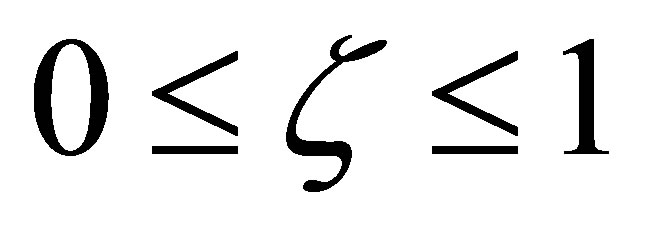

Next we will prove

(2.16)

(2.16)

Indeed, we have (2.16) for  by the initial condition. It follows that if

by the initial condition. It follows that if  is sufficiently small, then (2.16) holds true.

is sufficiently small, then (2.16) holds true.

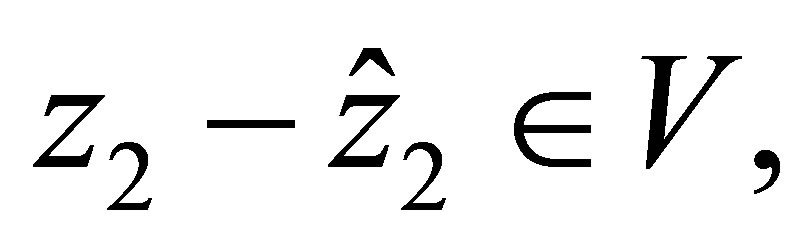

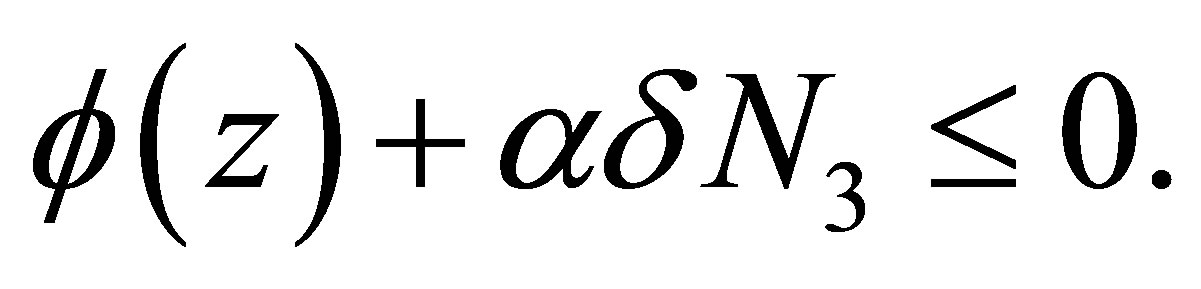

In order to prove (2.16) we assume that there exists  such that either

such that either  or

or  holds and we show the contradiction. For the sake of simplicity let us assume the former case holds. The latter case can be treated in the same way.By the estimate of

holds and we show the contradiction. For the sake of simplicity let us assume the former case holds. The latter case can be treated in the same way.By the estimate of  from the above we have, for any

from the above we have, for any ,

,  there exists a neighborhood V of

there exists a neighborhood V of  such that if

such that if  then

then  and

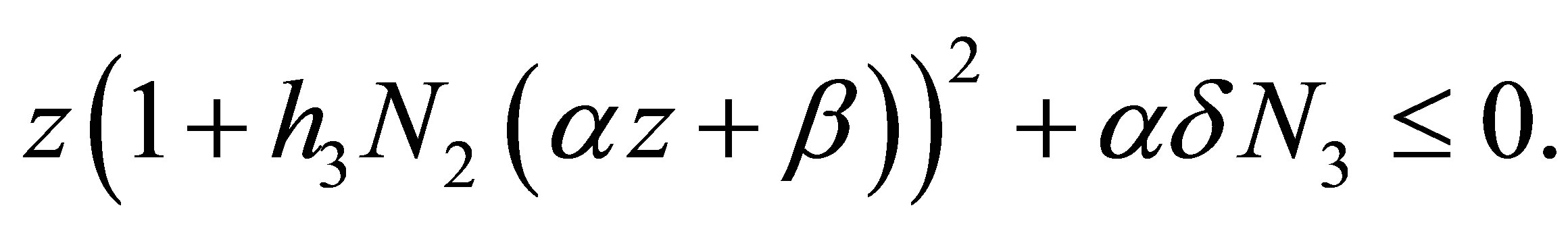

and  hold. Hence we have

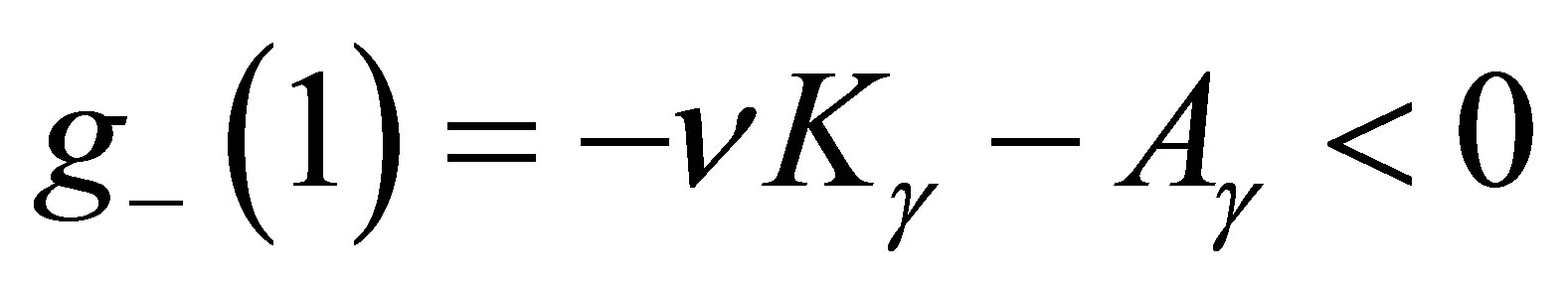

hold. Hence we have

(2.17)

(2.17)

If  then the right hand side of (2.17) is negative. Therefore

then the right hand side of (2.17) is negative. Therefore  is decreasing near

is decreasing near . This implies that

. This implies that  does not tend to

does not tend to  when

when . Because

. Because  is continuous, we have

is continuous, we have . This is a contradiction. Hence we have the desired estimate.

. This is a contradiction. Hence we have the desired estimate.

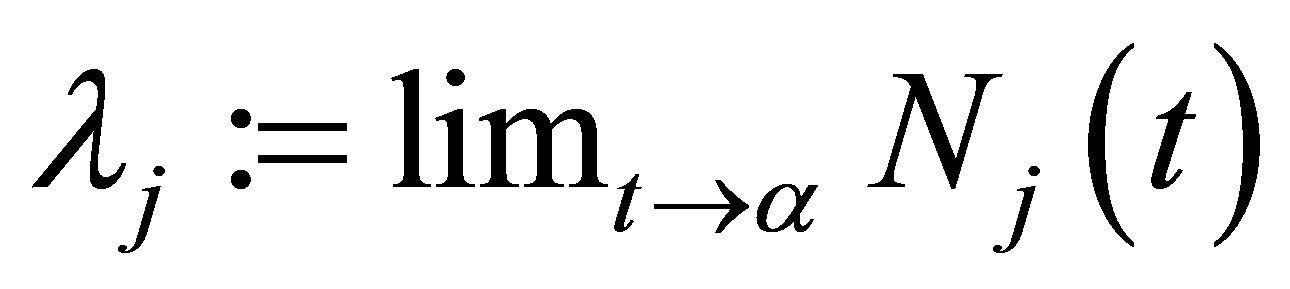

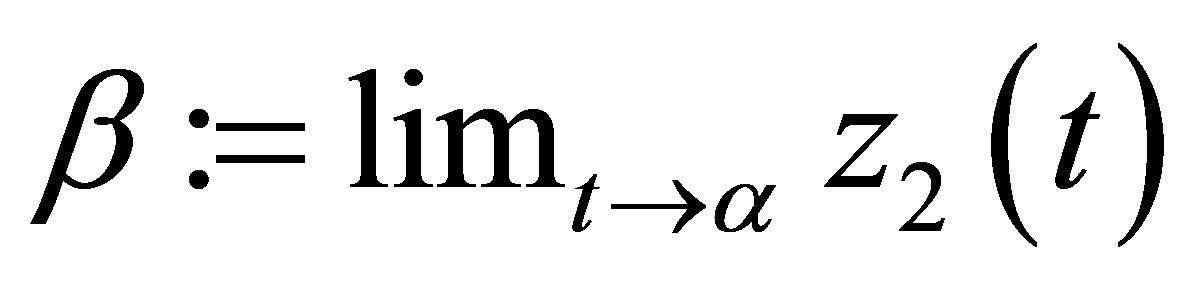

We shall prove the existence of a global solution. Set  and let

and let  be the maximal interval for which

be the maximal interval for which  and

and  are defined. If

are defined. If , then we are done. Assume that

, then we are done. Assume that  We will show that the limits

We will show that the limits  and

and  exist. We set

exist. We set  where

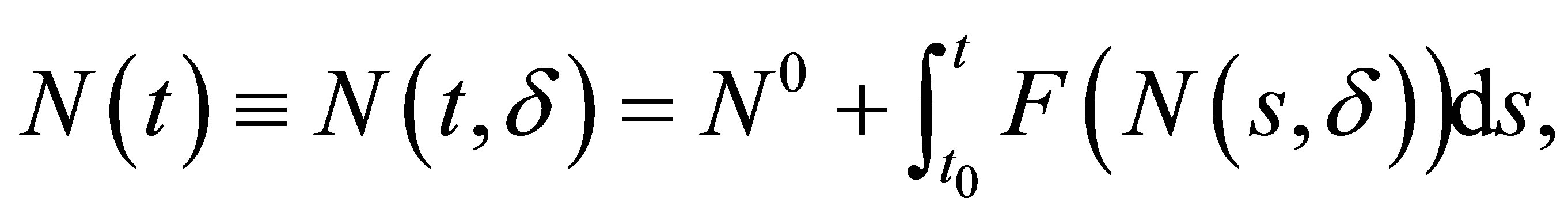

where  is the right hand sides of the Equations (1.1)-(1.4), respectively. We write (1.1)-(1.4) into an equivalent system of integral equations

is the right hand sides of the Equations (1.1)-(1.4), respectively. We write (1.1)-(1.4) into an equivalent system of integral equations

(2.18)

(2.18)

By the apriori estimates from the above,  is bounded on

is bounded on . Hence there exists M such that

. Hence there exists M such that  It follows that the limit

It follows that the limit  exists. If we define

exists. If we define , then

, then  is continuous up to

is continuous up to . We will show that it is

. We will show that it is . For this purpose it is sufficient to show that

. For this purpose it is sufficient to show that  We note that

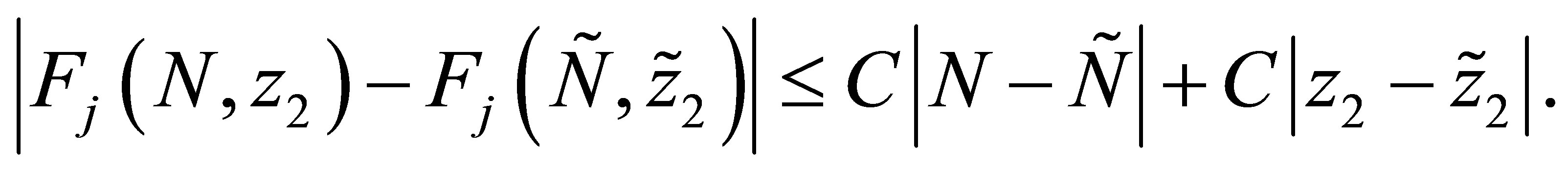

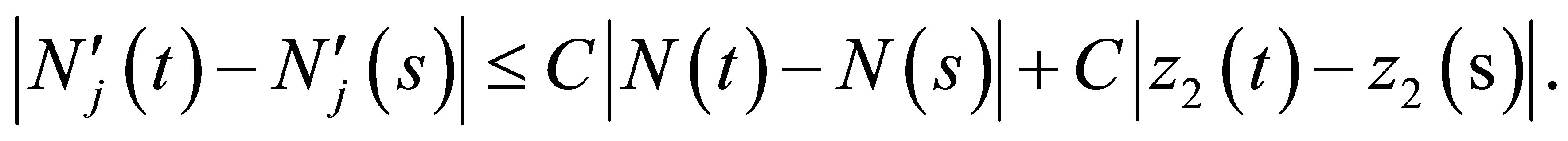

We note that  is Lipschitz continuous in each variable because we have apriori estimates of N and

is Lipschitz continuous in each variable because we have apriori estimates of N and . Namely there exists C > 0 independent of N and

. Namely there exists C > 0 independent of N and  such that

such that

Hence, by (1.1)-(1.4) we have

This proves the assertion. We can similarly prove for  .We can solve (1.1)-(1.4) with the initial values

.We can solve (1.1)-(1.4) with the initial values  and

and  at

at . Then by the unique existence of the solution we can extend

. Then by the unique existence of the solution we can extend  and

and  to some neighborhood of

to some neighborhood of . This contradicts to the definition of

. This contradicts to the definition of . Hence we have

. Hence we have . This ends the proof.

. This ends the proof.

Remark. 1) We remark that the apriori estimate of a solution does not depend on the cost of evolution  and the additive genetic variance g>0. This means that the evolution of a character has little effect to the bound of sum of populations of three species.

and the additive genetic variance g>0. This means that the evolution of a character has little effect to the bound of sum of populations of three species.

2) As a corollary to Theorem 2 we see that if there is no effect of evolution, i.e.,  then (1.1)- (1.3) with the initial condition (1.6) has a unique global solution. Indeed, (1.1)-(1.4) can be split into (1.1)-(1.4),

then (1.1)- (1.3) with the initial condition (1.6) has a unique global solution. Indeed, (1.1)-(1.4) can be split into (1.1)-(1.4),  The latter equation can be integrated. In view of the uniqueness of the solution of (1.1)-(1.4) we see that (1.1)-(1.3) has a unique solution.

The latter equation can be integrated. In view of the uniqueness of the solution of (1.1)-(1.4) we see that (1.1)-(1.3) has a unique solution.

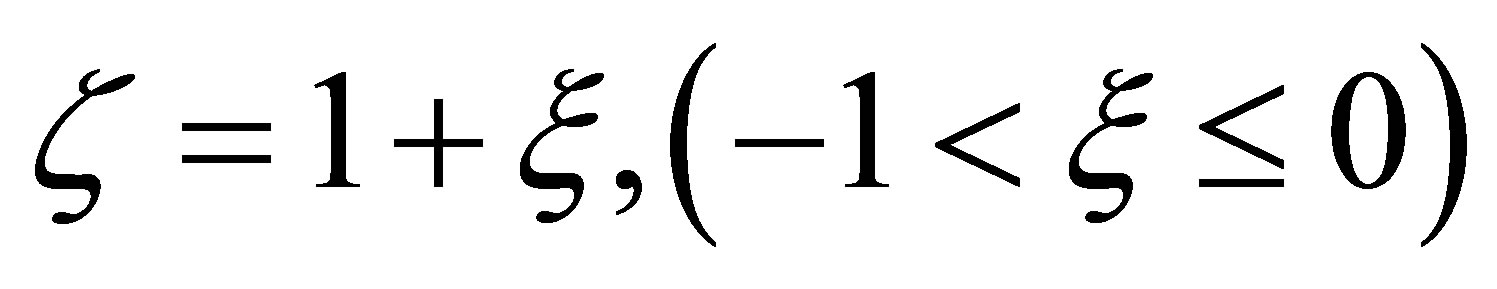

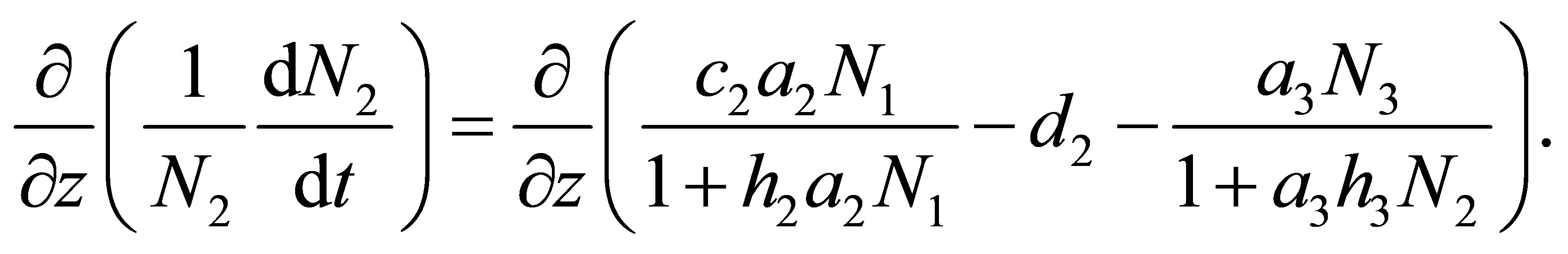

3. Intermittency of Evolution Effect

We shall study the effect of evolution to dynamics of (1.1)-(1.4).More precisely, we will study how the dynamics of (1.4) is related with that of (1.1)-(1.3).By setting  we write (1.4) in the form

we write (1.4) in the form

(3.1)

(3.1)

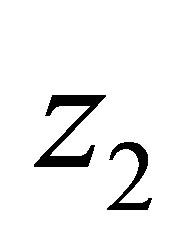

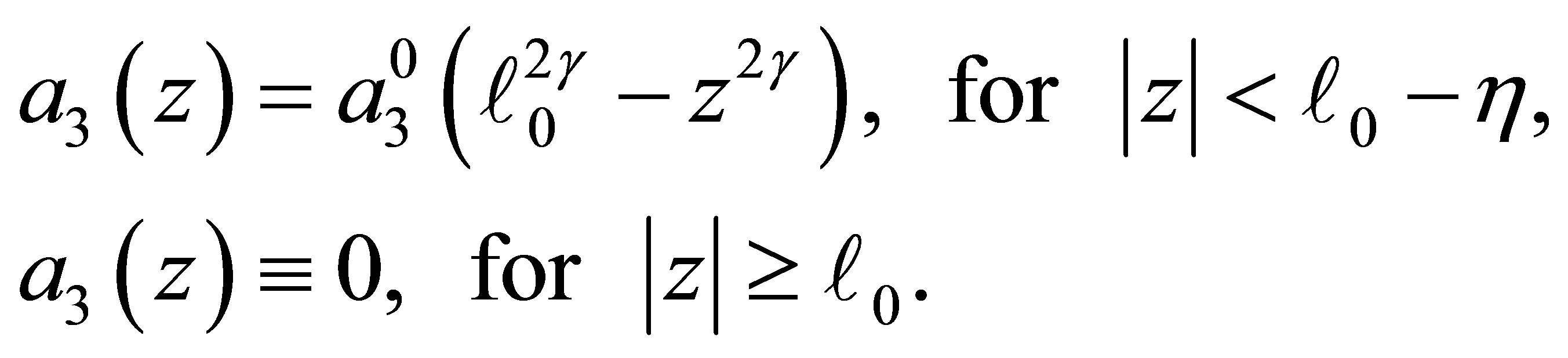

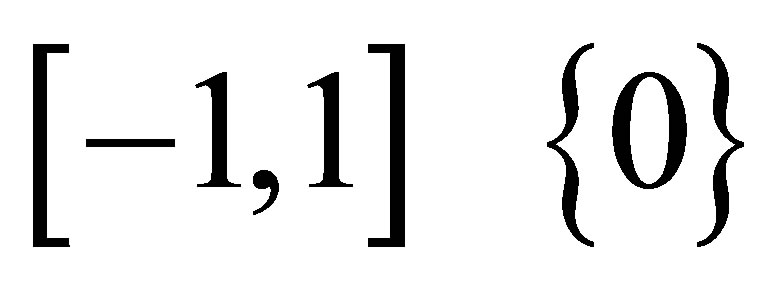

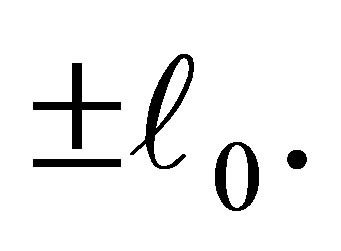

Let  be an integer and

be an integer and  and

and  be constants. We assume

be constants. We assume

(C.1)

(C.1)

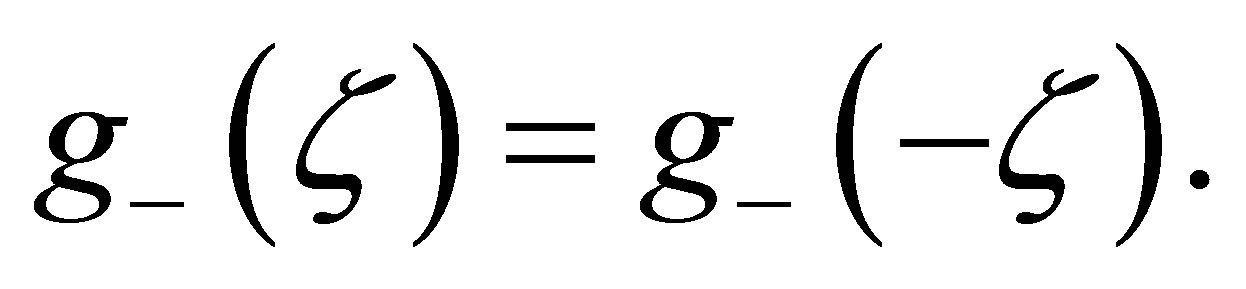

We also assume that  is twice continuously differentiable and nonnegative in the closed intervals

is twice continuously differentiable and nonnegative in the closed intervals  and

and . If we denote the right-hand side of (3.1) by

. If we denote the right-hand side of (3.1) by , then, by (C.1) we have

, then, by (C.1) we have

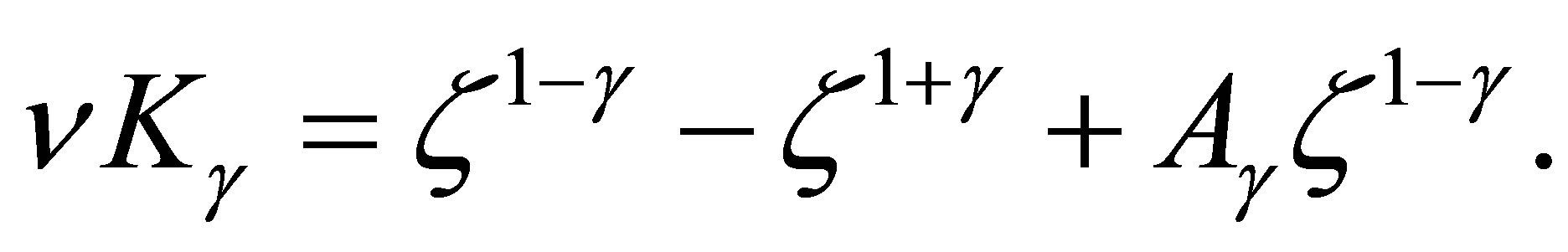

(3.2)

(3.2)

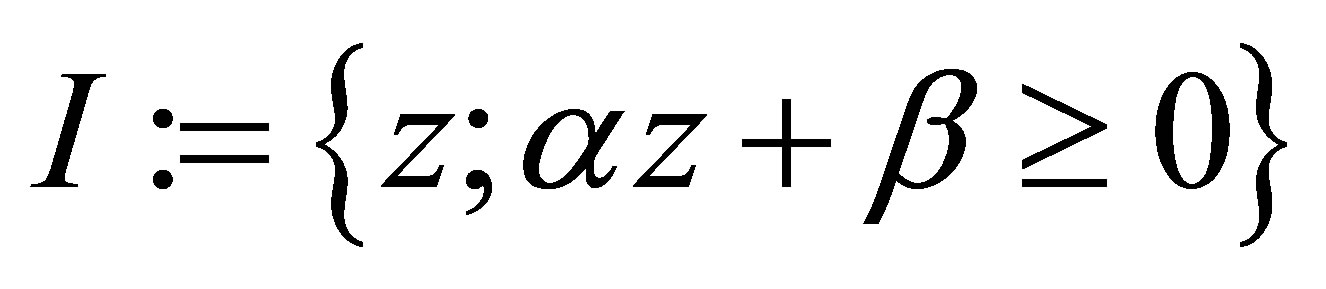

on  We define

We define on

on  by the right-hand side of (3.2). Define, for

by the right-hand side of (3.2). Define, for

(3.3)

(3.3)

We first study the behavior of .

.

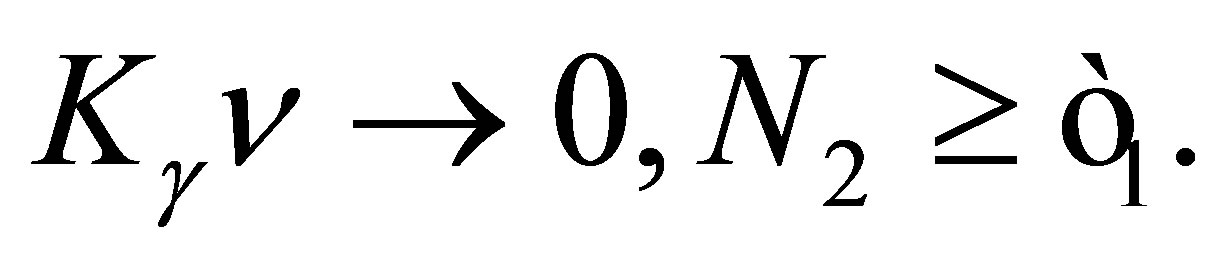

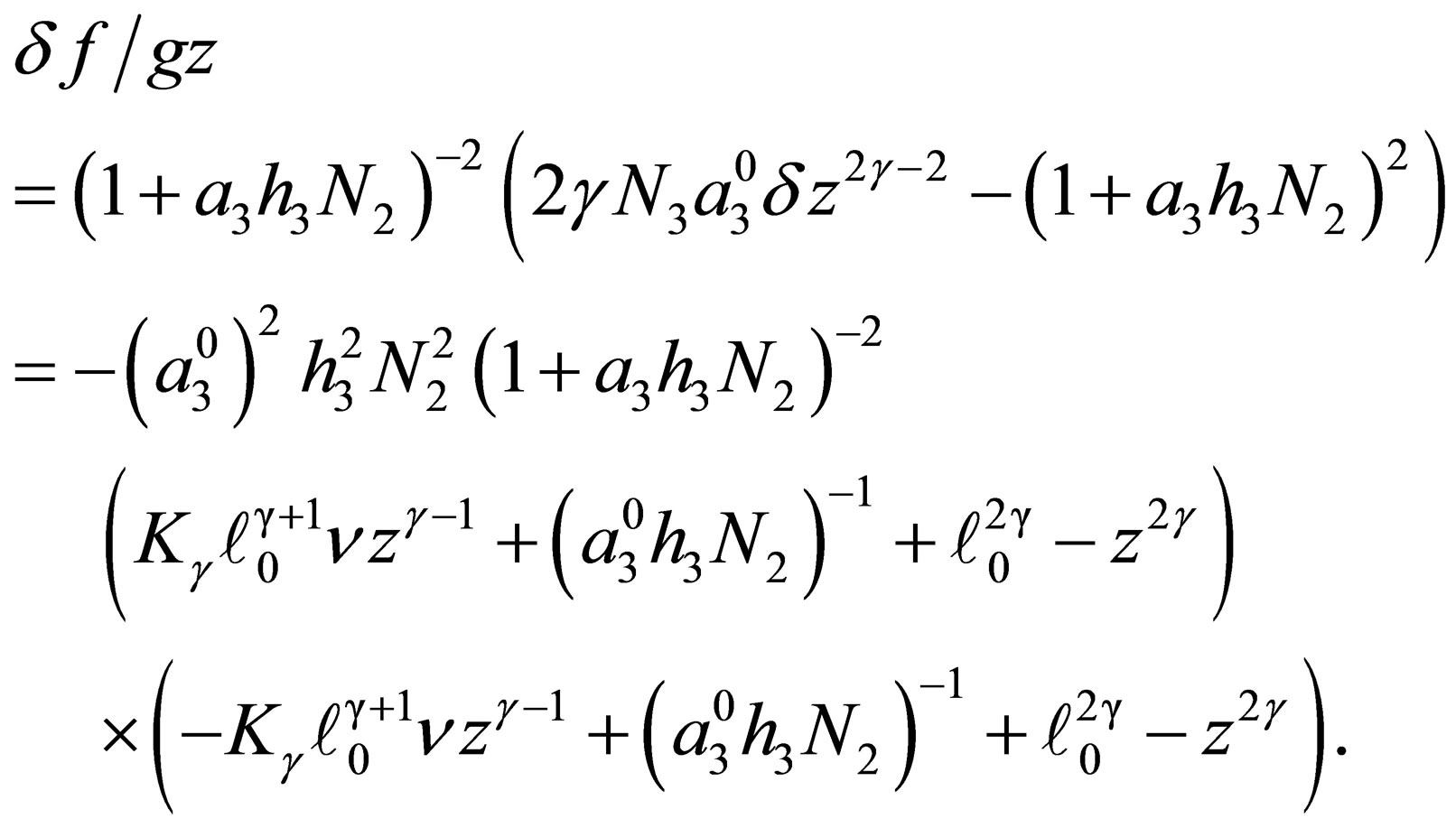

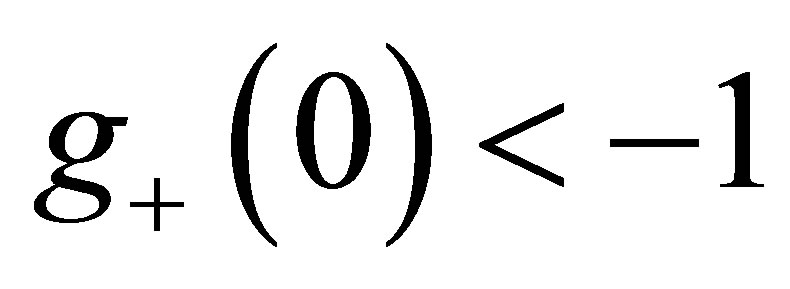

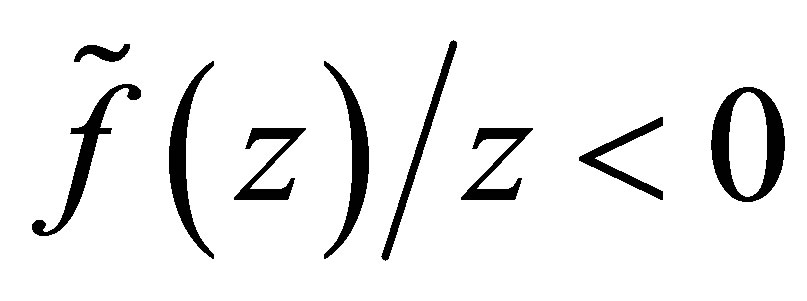

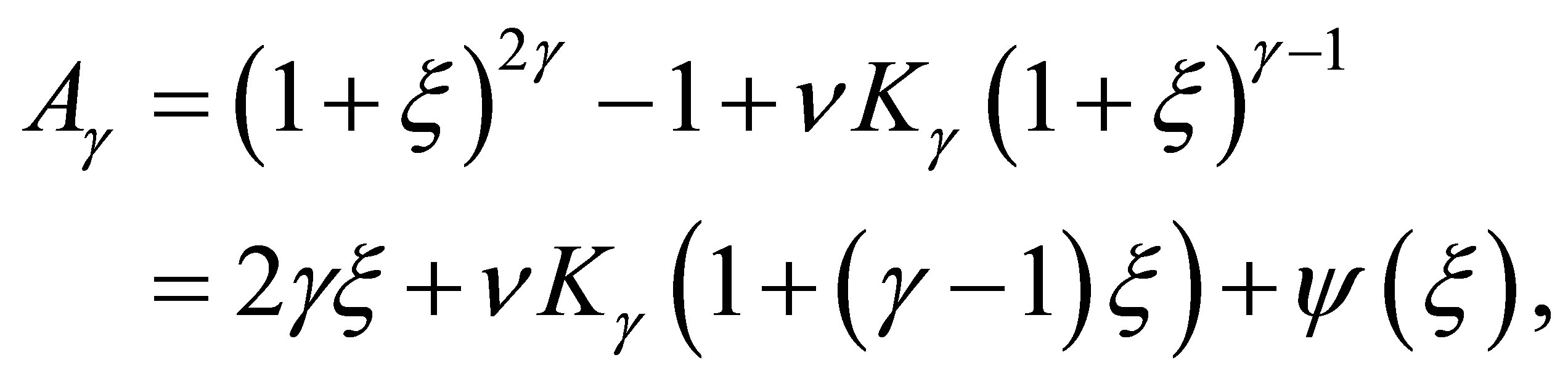

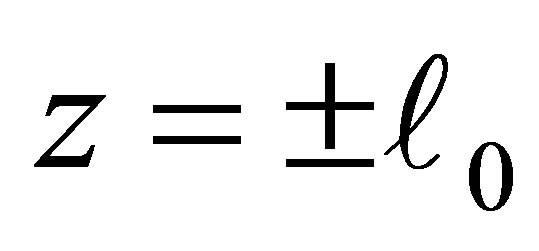

LEMMA 3.1. 1) Assume  Suppose that

Suppose that . Then

. Then  has a unique zero z = 0 in the interval

has a unique zero z = 0 in the interval  and

and  is negative on

is negative on .

.

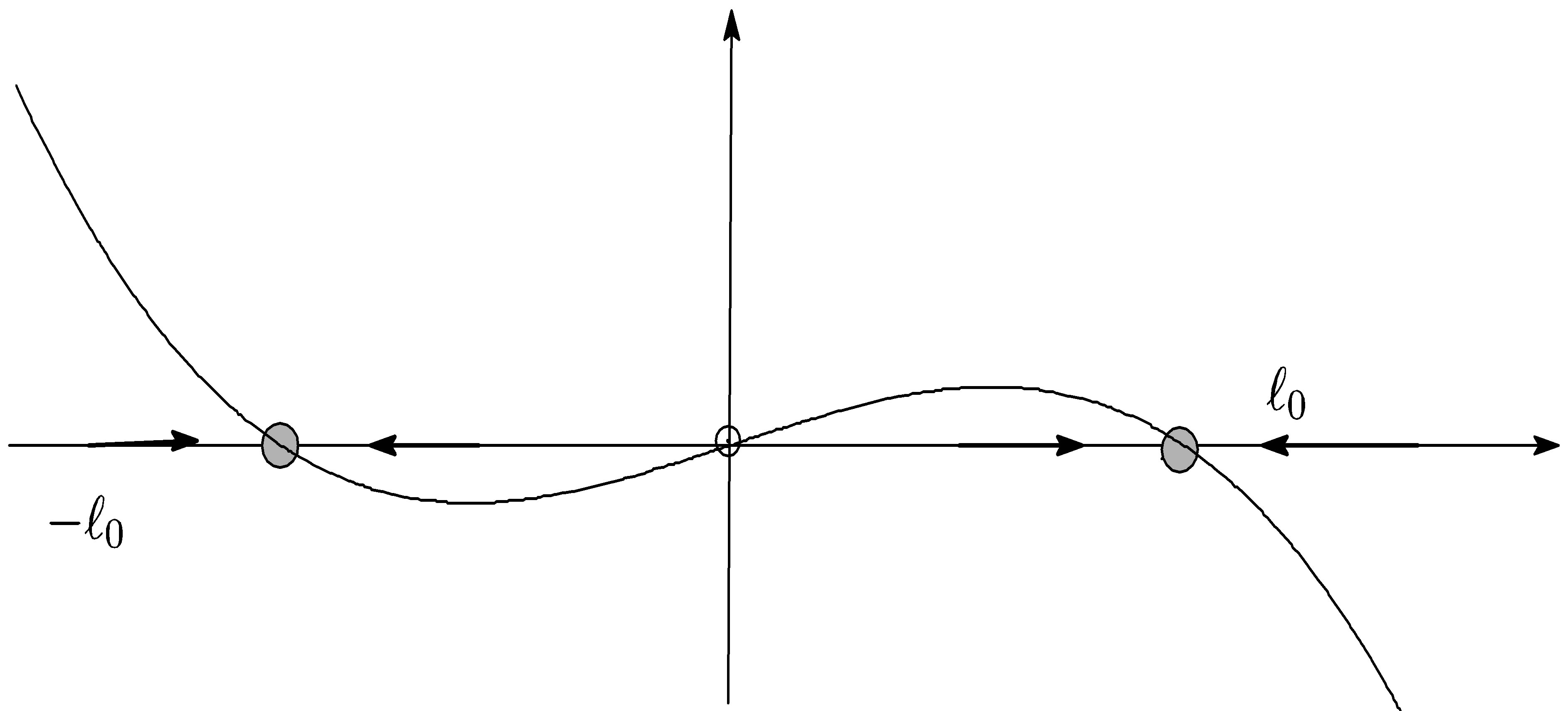

Assume . Then

. Then  has simple zeros,

has simple zeros,  and 0 on

and 0 on . The function

. The function  is negative on the intervals

is negative on the intervals  and

and , while it is positive on

, while it is positive on  and

and . (cf. Figure 1).

. (cf. Figure 1).

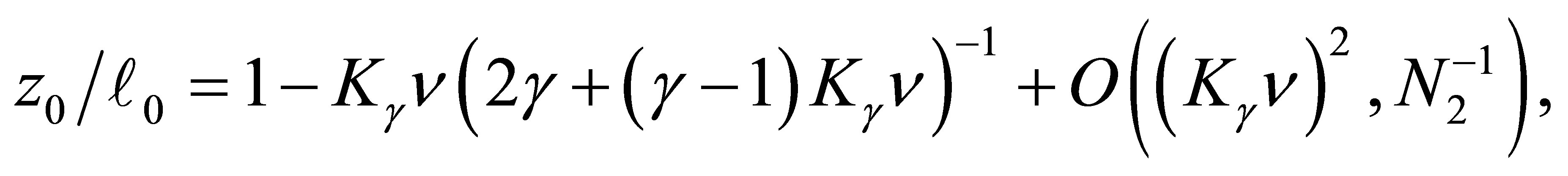

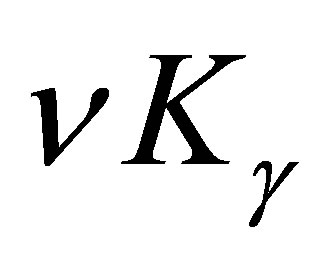

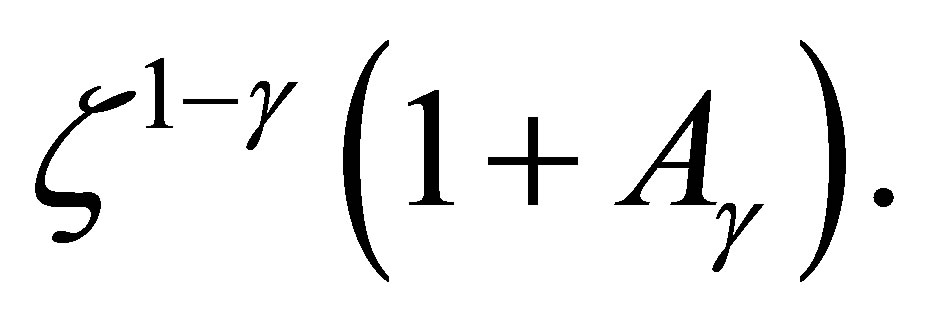

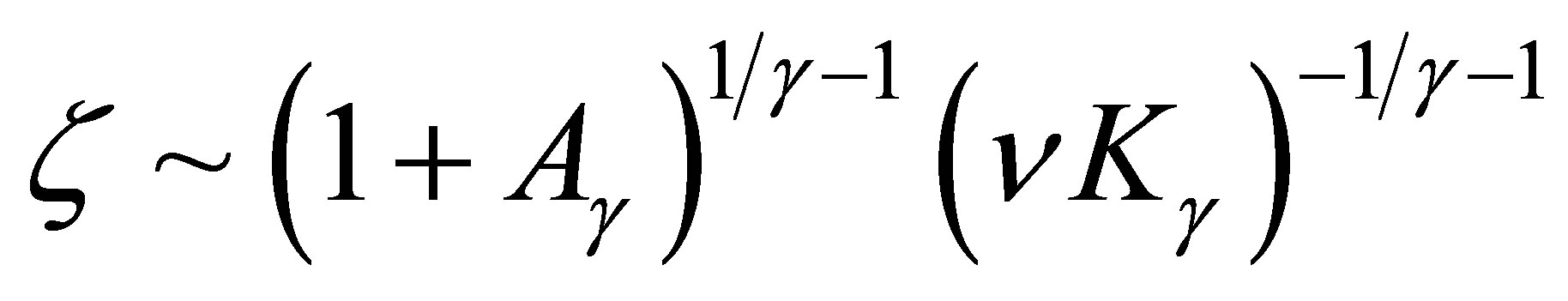

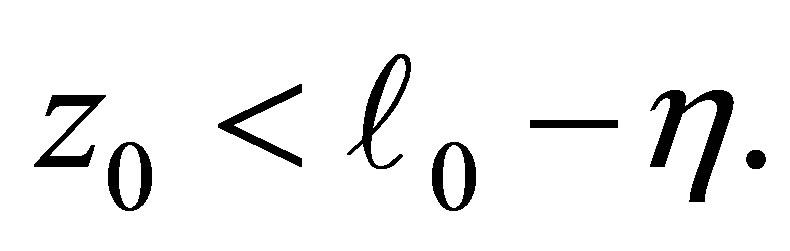

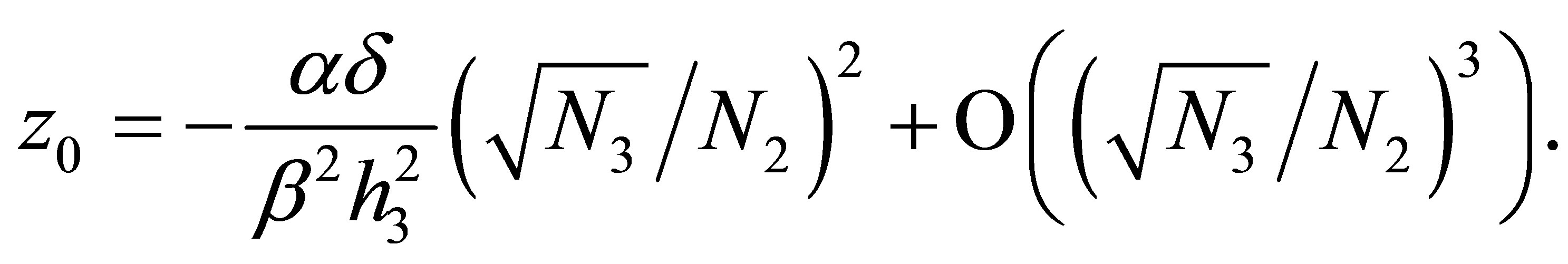

Moreover, there exists  such that z0 has an asymptotic behavior

such that z0 has an asymptotic behavior

(3.4)

(3.4)

when  Similarly we have

Similarly we have

(3.5)

(3.5)

when

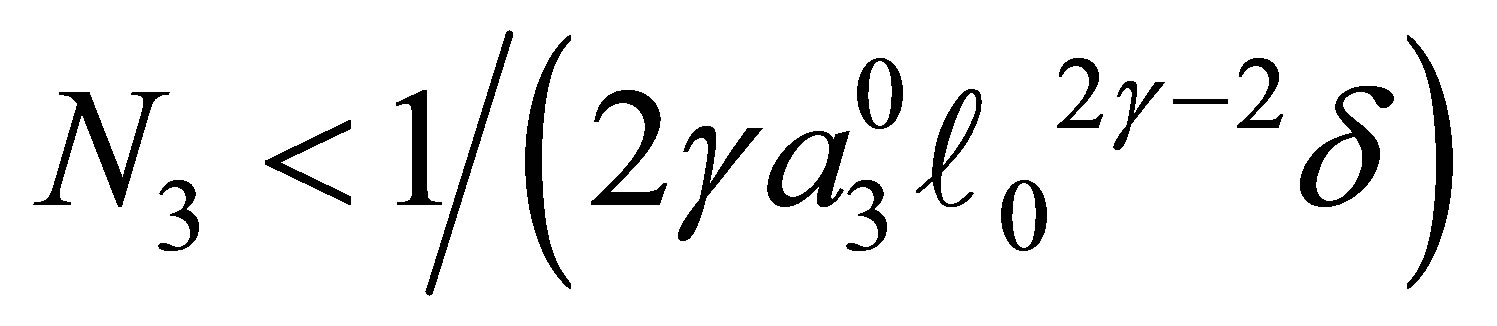

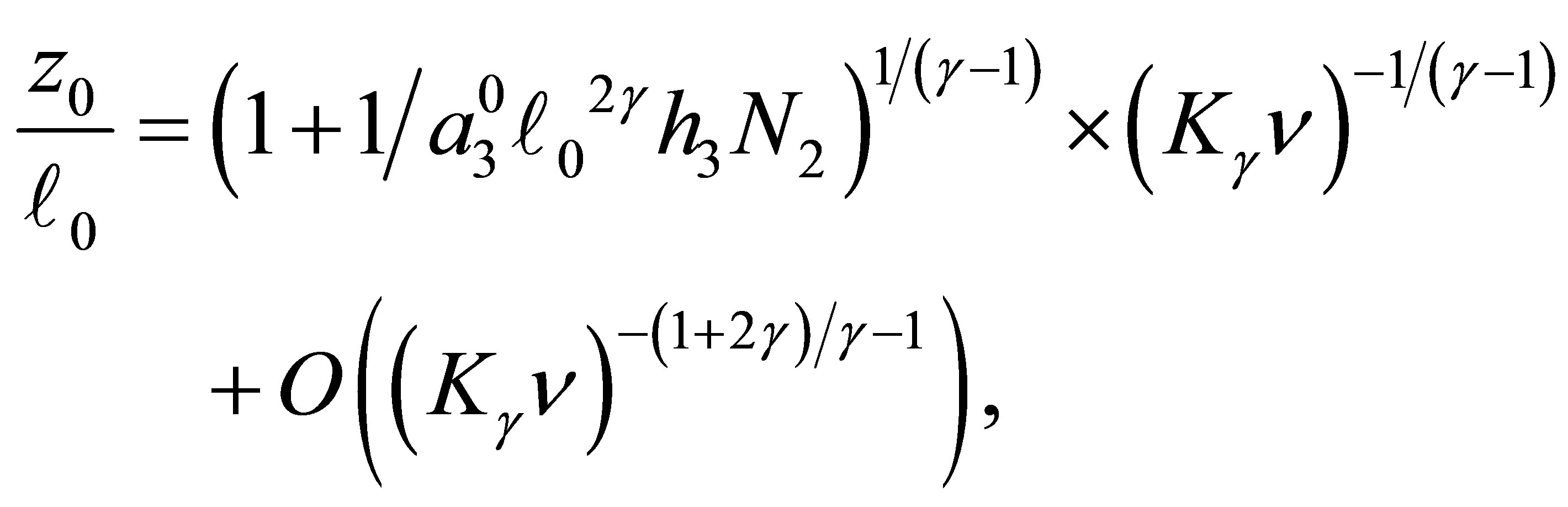

2) Assume  If

If  then

then  has simple zeros,

has simple zeros,  and 0 on

and 0 on .

.

The function  is negative on the intervals

is negative on the intervals  and

and  while it is positive on

while it is positive on  and

and . (cf. Figure 1).

. (cf. Figure 1).

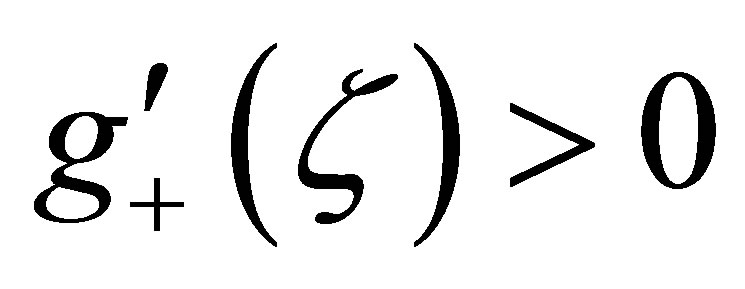

If  then

then  has a unique zero z = 0 in

has a unique zero z = 0 in  and

and  is positive on

is positive on  (cf. Figure 2).

(cf. Figure 2).

Figure 1. .

.

Proof. We divide the proof into 5 steps.

Step 1. By (C.1) we have

(3.6)

(3.6)

Set

(3.7)

(3.7)

and define

(3.8)

(3.8)

We consider the zeros and the sign of  in the interval

in the interval

Step 2. First we consider the case  Assume that

Assume that  is an odd integer. Because

is an odd integer. Because  is an even integer, we have

is an even integer, we have  We have

We have  and

and . Because we easily see that

. Because we easily see that  if

if , it follows that

, it follows that  has no zero point on

has no zero point on .

.

In order to study the zero of  in (0,1), note

in (0,1), note . One easily see that the assumption

. One easily see that the assumption  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  Because

Because  on (0,1], we see that

on (0,1], we see that  has only one zero point in the interval (0,1] if

has only one zero point in the interval (0,1] if  In view of (3.6) we conclude that

In view of (3.6) we conclude that  has zero points

has zero points  and 0 in the interval

and 0 in the interval  for some

for some . It is also clear that if the opposite inequality

. It is also clear that if the opposite inequality  holds, then

holds, then  on

on .

.

Next we consider the case  is even. By the same way as in the odd case, we have

is even. By the same way as in the odd case, we have ,

,  and

and  Since

Since  is strictly increasing on (0,1), there exists unique

is strictly increasing on (0,1), there exists unique ,

,  such that

such that  In order to show that

In order to show that  has no zero on

has no zero on  we note

we note

Figure 2.  and

and

Because

Because  and

and

on

on , we see that

, we see that  has a unique zero point

has a unique zero point  on

on . Clearly,

. Clearly,  has only one zero

has only one zero , because

, because  for all

for all  which proves the assertion. The sign of

which proves the assertion. The sign of  is almost clear from the definitions of

is almost clear from the definitions of  and the argument in the above.

and the argument in the above.

Step 3. We will show the asymptotic formula of  in (3.4). In view of the argument in Step 2 we may consider

in (3.4). In view of the argument in Step 2 we may consider

If we set , then we have

, then we have

(3.9)

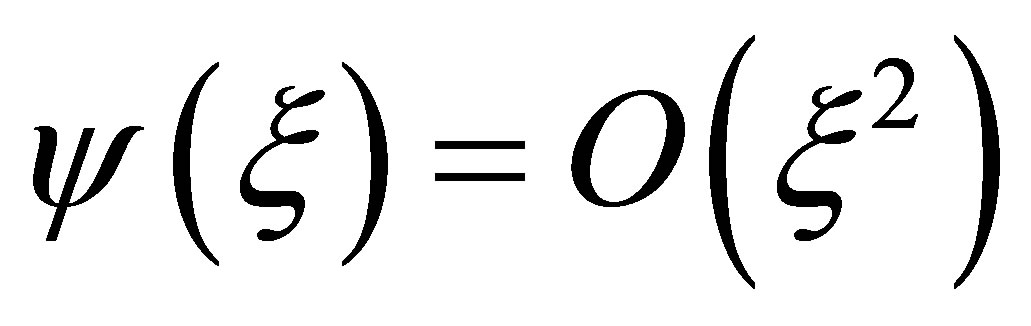

(3.9)

where  is a polynomial of

is a polynomial of  with positive coefficients. Hence we have

with positive coefficients. Hence we have

(3.10)

(3.10)

Hence, for  sufficiently small we can uniquely solve (3.10). By an implicit function theorem we see that

sufficiently small we can uniquely solve (3.10). By an implicit function theorem we see that  is a smooth function of

is a smooth function of  such that

such that  It follows that

It follows that

Therefore we have (3.4).

Step 4. Next we will prove (3.5). We will solve  namely

namely

(3.11)

(3.11)

for  Hence we have

Hence we have

(3.12)

(3.12)

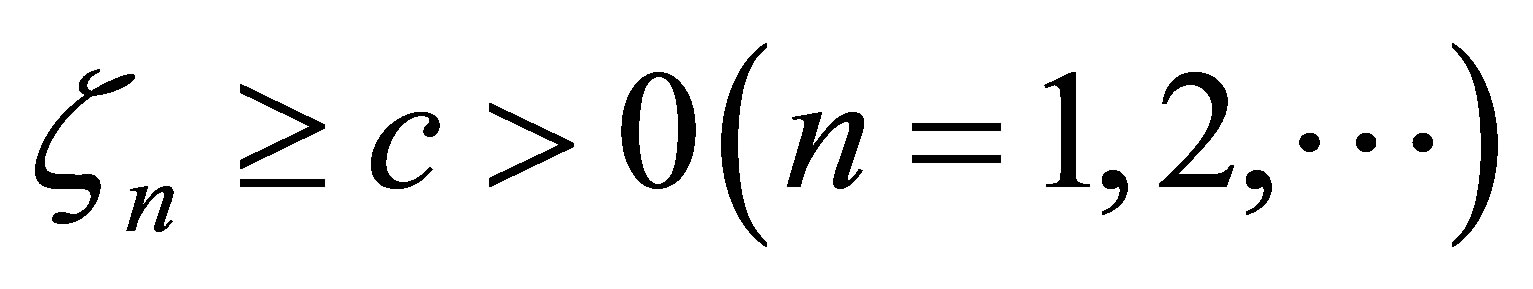

If  does not converges to zero when

does not converges to zero when  then there exist c>0 and a sequence

then there exist c>0 and a sequence  . Since the right-hand side of (3.12) is bounded for

. Since the right-hand side of (3.12) is bounded for  this leads to a contradiction. Hence

this leads to a contradiction. Hence  is asymptotically equal to

is asymptotically equal to

By solving this relation we have

when  By (3.11) we have

By (3.11) we have  . It follows that

. It follows that

By simple computations we obtain (3.5).

Step5. If  then we have

then we have  We can easily see that

We can easily see that  on

on  The solution of

The solution of  is given by

is given by  The rest of the assertion is almost clear from this formula. This completes the proof.

The rest of the assertion is almost clear from this formula. This completes the proof.

Remark. We will briefly discuss the difference of dynamics of z in (3.1) for f and  We note that two functions are identical for

We note that two functions are identical for  For a small number

For a small number , consider the case shown in Figure 2 for

, consider the case shown in Figure 2 for  Then f looks like as in Figure 3 where new attractive equilibrium points appear near

Then f looks like as in Figure 3 where new attractive equilibrium points appear near  because we have made a modification to

because we have made a modification to  so that

so that  The new equilibrium point corresponds to that of

The new equilibrium point corresponds to that of  with modulus larger than

with modulus larger than . Because of the new equilibrium points we have an apriori estimate of the solution for f. Namely, the orbit started from a neighborhood of the origin does not go beyond

. Because of the new equilibrium points we have an apriori estimate of the solution for f. Namely, the orbit started from a neighborhood of the origin does not go beyond  This fact is important since, if otherwise, the efficiency

This fact is important since, if otherwise, the efficiency  becomes negative. Note that the dynamics of f and

becomes negative. Note that the dynamics of f and  is the same outside some neighborhood of the boundary

is the same outside some neighborhood of the boundary . We also note that a similar situation occurs in the case

. We also note that a similar situation occurs in the case  with

with  (cf. Figures 1 and 4).On the other hand, if

(cf. Figures 1 and 4).On the other hand, if , then the dynamics of f and

, then the dynamics of f and  in

in  may be different, while in other part both are the same.

may be different, while in other part both are the same.

We also note that the apriori estimate holds for f. Therefore apart from the neighborhood of  the dynamics of f is well approximated by that of

the dynamics of f is well approximated by that of , for which

, for which  we can make concrete analysis of the dynamics, although we do not have the apriori estimate.

we can make concrete analysis of the dynamics, although we do not have the apriori estimate.

Figure 3. Picture of f.

Figure 4. Picture of f.

We will study behaviors of solutions under the effect of evolution.

1) Behaviors near the equilibrium point.

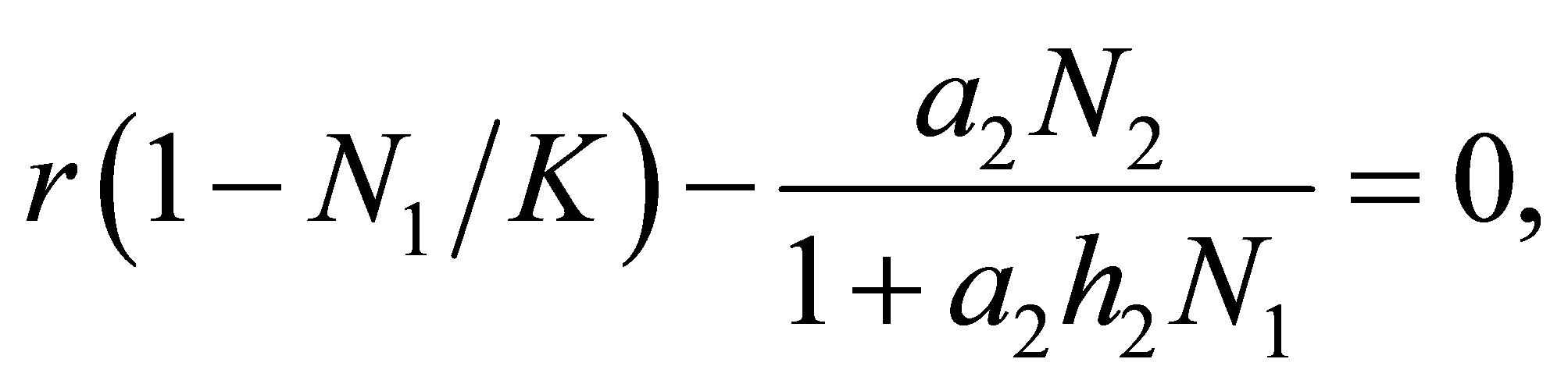

We consider how the dynamics of (1.1)-(1.4) is related to the dynamics (1.1)-(1.3) without evolution. We recall that (1.1)-(1.3) without an evolutional effect has what is called a tea-cup attractor. The isocline of (1.1)-(1.3), (3.1) is given by the family of equations

(3.13)

(3.13)

(3.14)

(3.14)

(3.15)

(3.15)

(3.16)

(3.16)

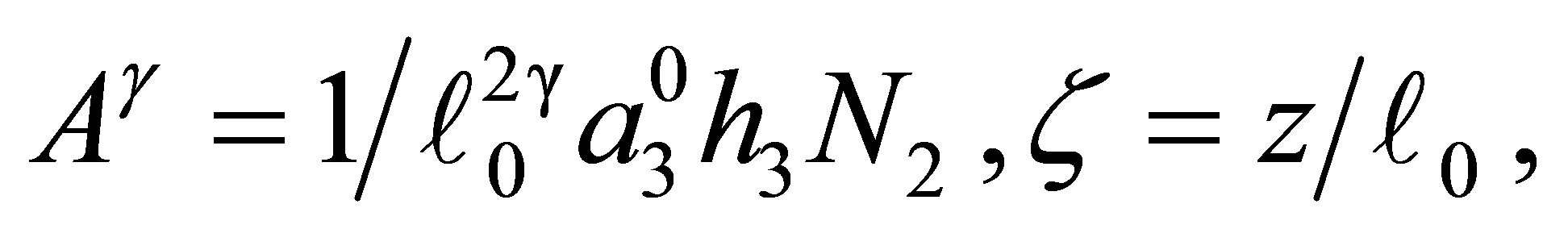

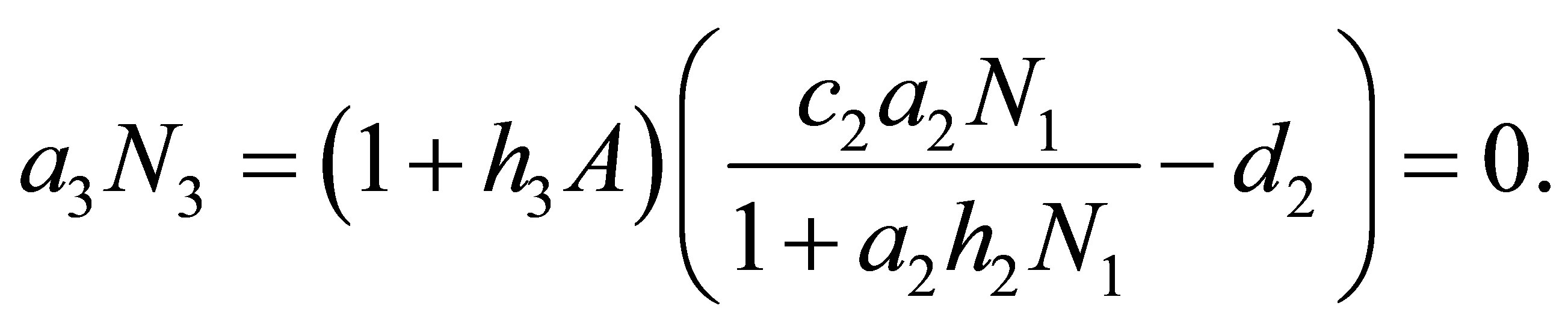

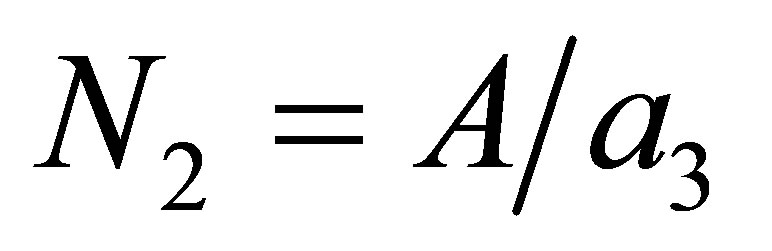

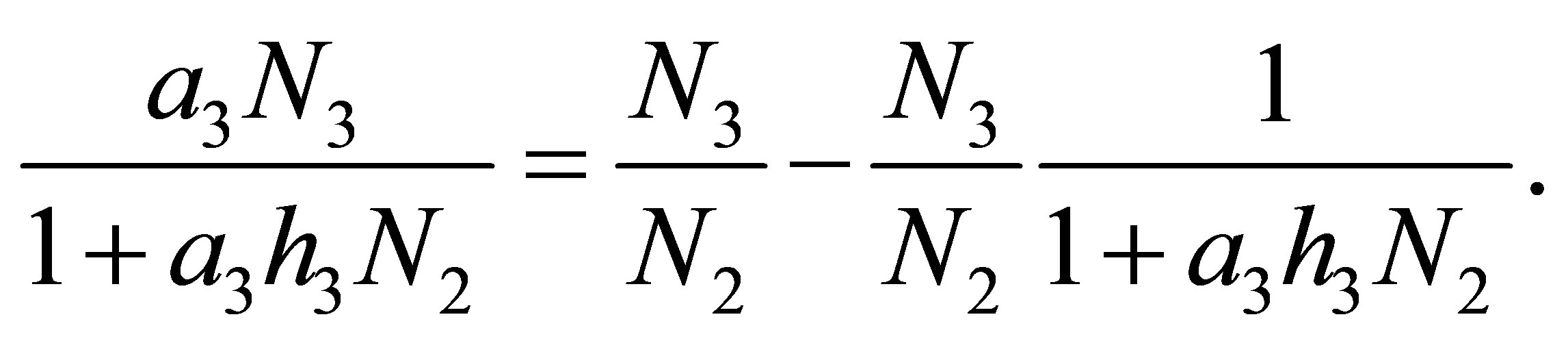

It follows from (3.15) that

(3.17)

(3.17)

One may assume that A is small since  is small. By (3.14) we have

is small. By (3.14) we have

(3.18)

(3.18)

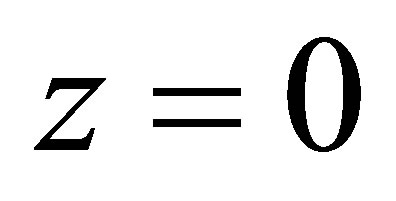

Let us first consider the non-evolutional case, z = 0 or the case where evolution becomes stationary, namely . Then there exists C > 0 such that

. Then there exists C > 0 such that  Hence

Hence  is small and

is small and  is close to K, by (3.13). It follows that there exists

is close to K, by (3.13). It follows that there exists  such that

such that  if

if  is sufficiently small. In terms of (3.17) and (3.18)

is sufficiently small. In terms of (3.17) and (3.18)  tends to infinity when

tends to infinity when . This implies a typical behavior of

. This implies a typical behavior of  and

and  around an equilibrium point when there is little effect of evolution. Numerical experiments show that the decrease of

around an equilibrium point when there is little effect of evolution. Numerical experiments show that the decrease of  occurs soon after the orbit approaches to the equilibrium point, namely

occurs soon after the orbit approaches to the equilibrium point, namely  becomes sufficiently large.

becomes sufficiently large.

Let us consider the evolutional case. Then the main difference from the non-evolutional case is that  may tends to zero. For the sake of simplicity, let us consider the case

may tends to zero. For the sake of simplicity, let us consider the case  or

or . Assume that there exists an orbit such that

. Assume that there exists an orbit such that  and

and  grows large. Because

grows large. Because  also grows large, it follows from (3.4) that

also grows large, it follows from (3.4) that  tends to zero, and we are in the situation that the orbit of

tends to zero, and we are in the situation that the orbit of  tends to

tends to . Therefore

. Therefore  tends to zero. Hence the boundedness of

tends to zero. Hence the boundedness of  implies that

implies that  becomes negative. Therefore, by (1.3),

becomes negative. Therefore, by (1.3), exponentially decreases. Note that the decrease of

exponentially decreases. Note that the decrease of  begins after

begins after  exceeds a certain constant independent of

exceeds a certain constant independent of  and

and  when

when . This exhibits a strong contrast to the non evolutional case where the collapse of

. This exhibits a strong contrast to the non evolutional case where the collapse of  occurs after

occurs after  becomes sufficiently large.

becomes sufficiently large.

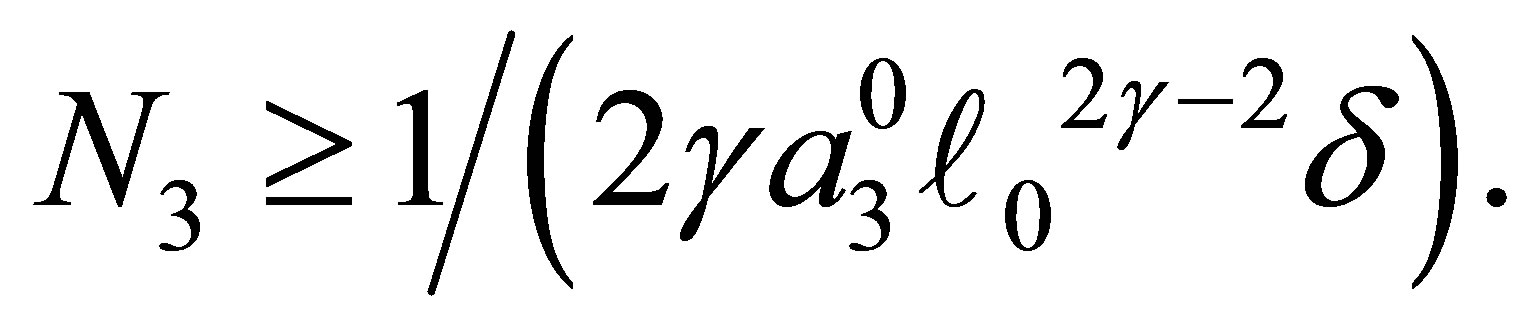

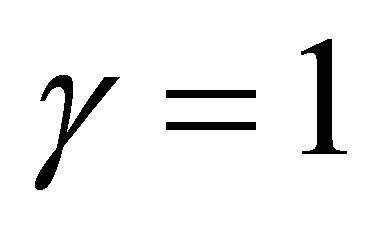

2) Effect of the parameter  to evolution.

to evolution.

In the predatory efficiency  in (C.1)

in (C.1)  represents sensitivity to z. Namely, as

represents sensitivity to z. Namely, as  increases,

increases,  for small z approaches to a constant function. The dynamics of z is quite different in the cases

for small z approaches to a constant function. The dynamics of z is quite different in the cases  and

and . Indeed, if

. Indeed, if  and

and

then evolution progresses. (cf. Figure 2 and Figure 3). The latter condition means either the cost of evolution is small,  or

or . We note that the attracttive equilibrium points near

. We note that the attracttive equilibrium points near  have the effect to hold the orbits around

have the effect to hold the orbits around . Conversely, if

. Conversely, if  , then we see that fluctuations in progress and rest of evolution takes place.

, then we see that fluctuations in progress and rest of evolution takes place.

In the case  we have a different situation. Indeed, if

we have a different situation. Indeed, if  then the evolution becomes stationary. If otherwise, then similar fluctuations in progress and rest of evolution as in the case

then the evolution becomes stationary. If otherwise, then similar fluctuations in progress and rest of evolution as in the case  takes place. We will show in the next section that in the linear case

takes place. We will show in the next section that in the linear case  we have a sharp contrast to the case

we have a sharp contrast to the case .

.

3) Fluctuations of  and

and .

.

The rhythm of  and

and  is also observed in a nonevolutional system and it is related with the structure of a tea-cup attractor. We have a similar phenomenon for an evolutional system.

is also observed in a nonevolutional system and it is related with the structure of a tea-cup attractor. We have a similar phenomenon for an evolutional system.

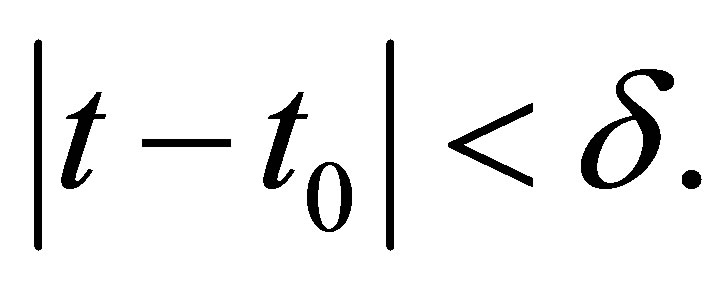

Let  and

and  be a solution of (1.1)- (1.4). One can show by Poincaré –Bendixon theorem that

be a solution of (1.1)- (1.4). One can show by Poincaré –Bendixon theorem that  and

and  are an oscillating solution of two species under appropriate choice of parameters. Note that

are an oscillating solution of two species under appropriate choice of parameters. Note that  tends to zero exponentially. By the continuity of solutions of the initial value problem with respect to an initial value and the apriori estimate of a solution, one can see that for every

tends to zero exponentially. By the continuity of solutions of the initial value problem with respect to an initial value and the apriori estimate of a solution, one can see that for every  and

and  there exists

there exists  such that if

such that if

then

for all  Here, without loss of generality we may assume that the initial time is 0.Especially, this shows that there appears a rhythm of

Here, without loss of generality we may assume that the initial time is 0.Especially, this shows that there appears a rhythm of  and

and  for some interval of time. Note that

for some interval of time. Note that  is small and the evolution becomes stationary, i.e.,

is small and the evolution becomes stationary, i.e., .

.

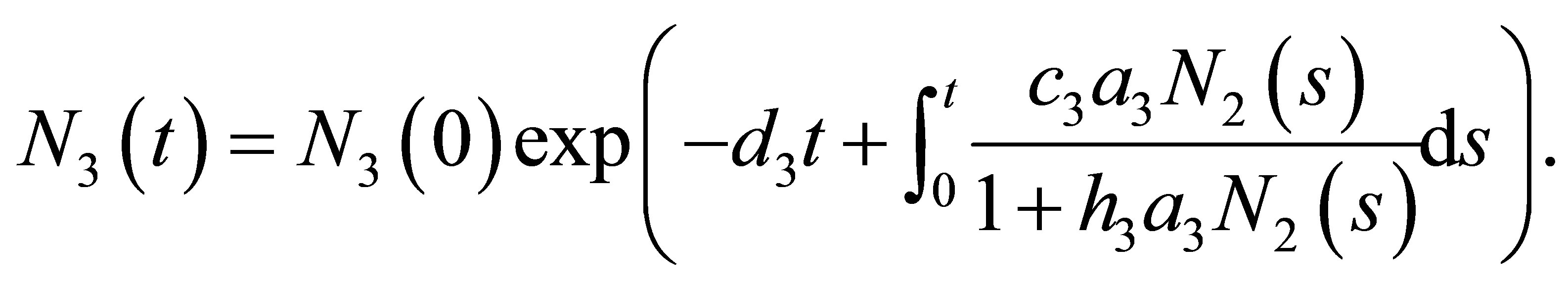

In order to estimate T, we take ,

,  and

and . By integrating the equation of

. By integrating the equation of , one has

, one has

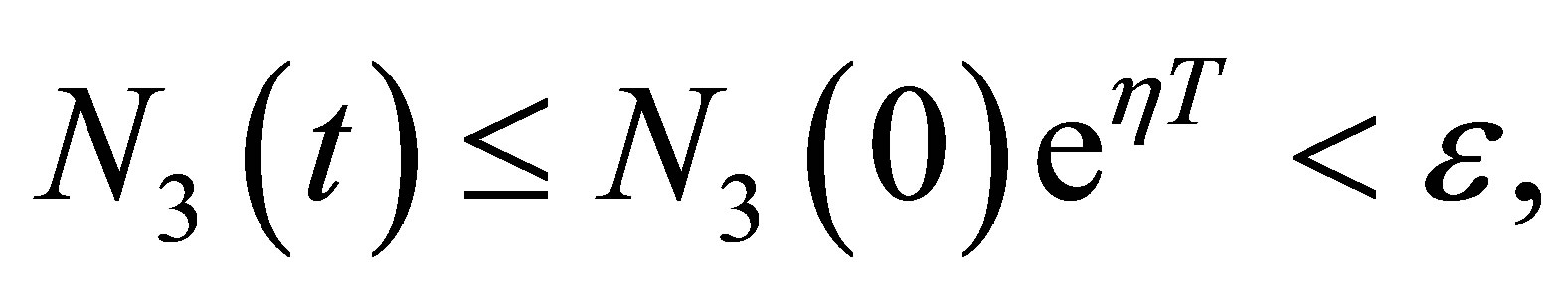

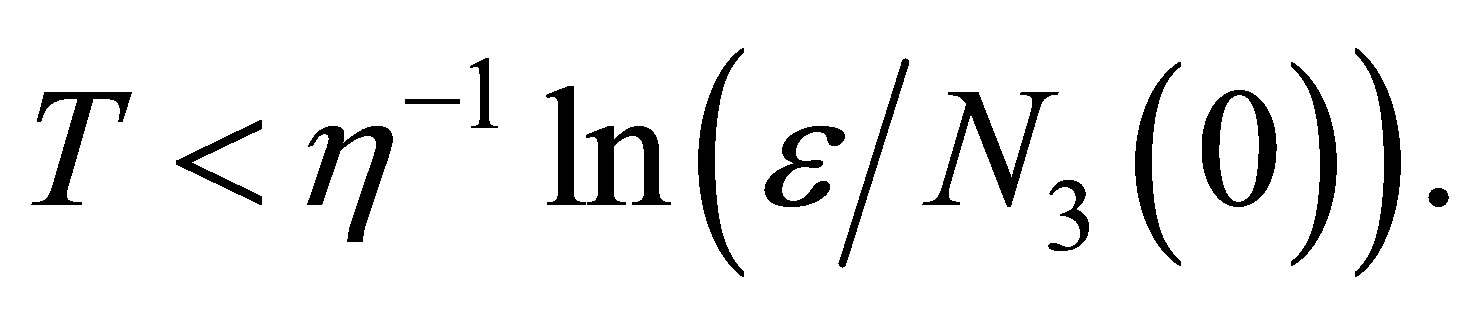

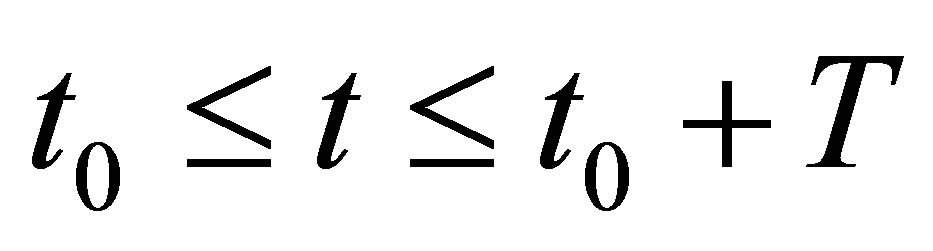

Hence, if we have

(3.19)

(3.19)

for sufficiently small , then we have

, then we have  from which we have the estimate of time length T,

from which we have the estimate of time length T,  We have a similar condition like (3.19) in the general case

We have a similar condition like (3.19) in the general case  by replacing 0 and T, respectively, by

by replacing 0 and T, respectively, by  and

and  A similar condition like (3.19) holds for some

A similar condition like (3.19) holds for some  and T if we have an averaging property:

and T if we have an averaging property:

4) The limit case when evolution cost tends to zero.

We assume . If the evolution cost tends to zero, namely

. If the evolution cost tends to zero, namely  grows from zero to

grows from zero to  , then, by (3.4) and the definition of

, then, by (3.4) and the definition of

approaches to the origin.

approaches to the origin.

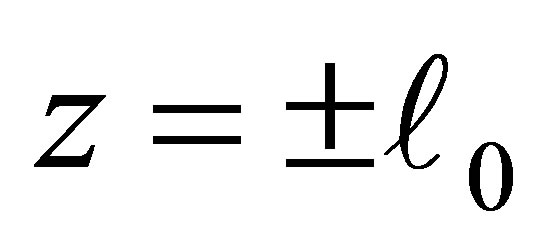

Therefore, the evolution progresses, namely z approaches either of the points . It follows that the predatory efficiency

. It follows that the predatory efficiency . By the same reasoning as in 1)

. By the same reasoning as in 1)  tends to zero. We note that in the limit case

tends to zero. We note that in the limit case  the third species dies out. This agrees with an ecological observation.

the third species dies out. This agrees with an ecological observation.

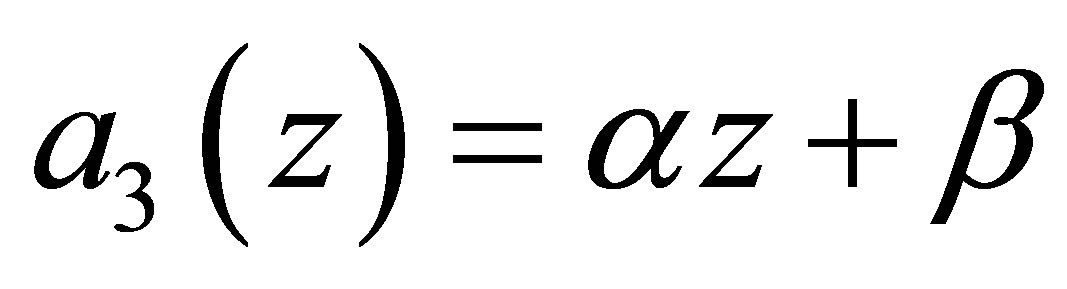

4. Evolution for a Linear Predatory Efficiency

We will discuss the evolution in the case

(4.1)

(4.1)

where  is a real constant and

is a real constant and  .As in the previous case we make modifications of

.As in the previous case we make modifications of  in some small neighborhood of the zero point

in some small neighborhood of the zero point  such that

such that .

.

For the sake of simplicity, we assume that . By repeating the same arguments as in Section 2 we see that the system of Equations (1.1)-(1.4) with the initial condition (1.6) has a unique global solution in

. By repeating the same arguments as in Section 2 we see that the system of Equations (1.1)-(1.4) with the initial condition (1.6) has a unique global solution in

We will study the dynamics of the evolution in relation with the populations  and

and .We now define

.We now define

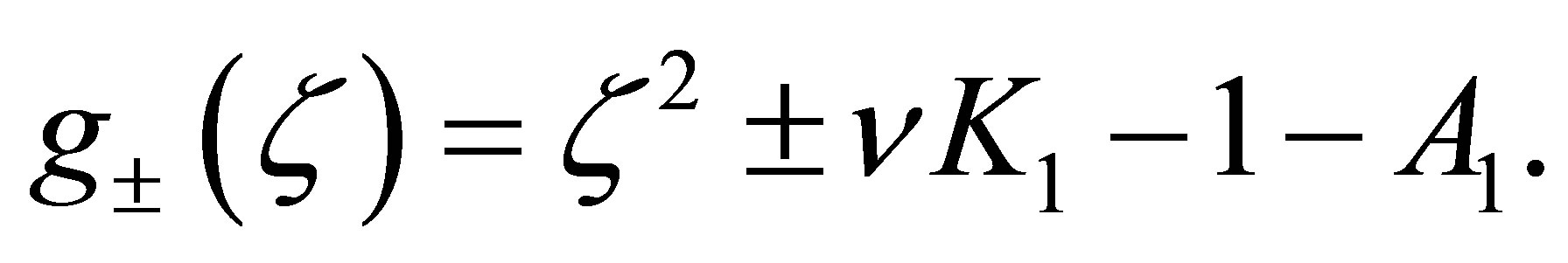

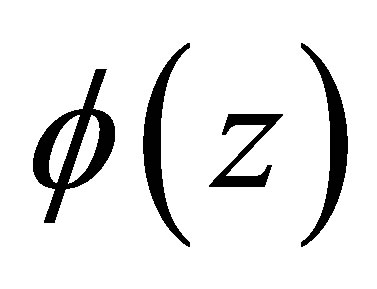

(4.2)

(4.2)

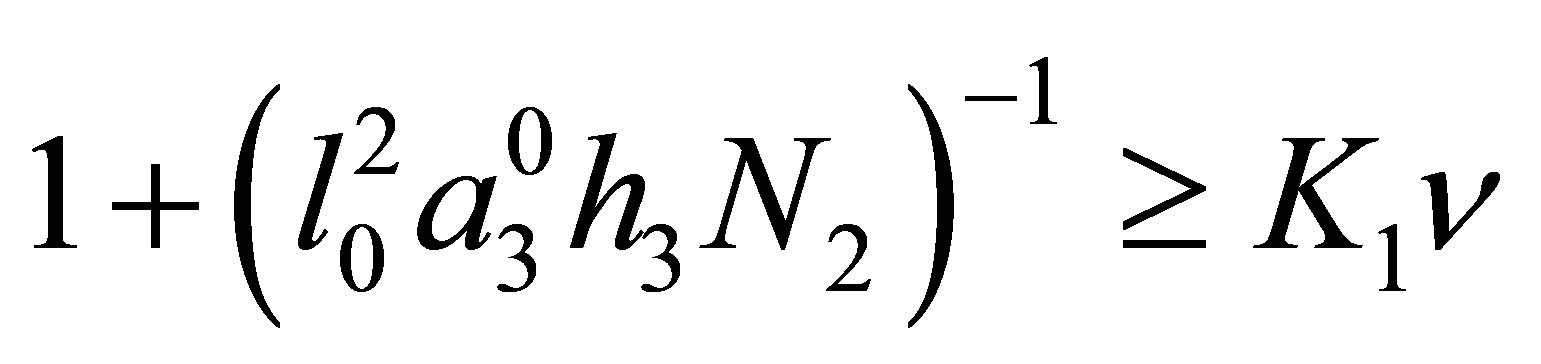

The condition  is equivalent to

is equivalent to

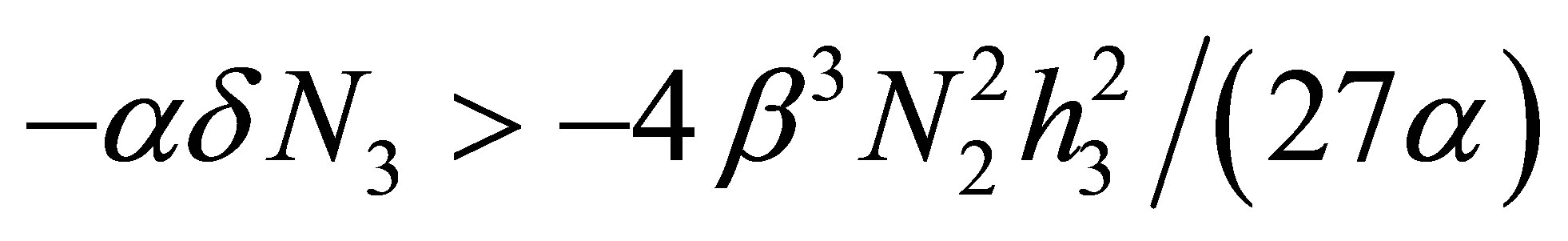

By definition we may consider (4.3) in the set  because, if otherwise,

because, if otherwise,  Set

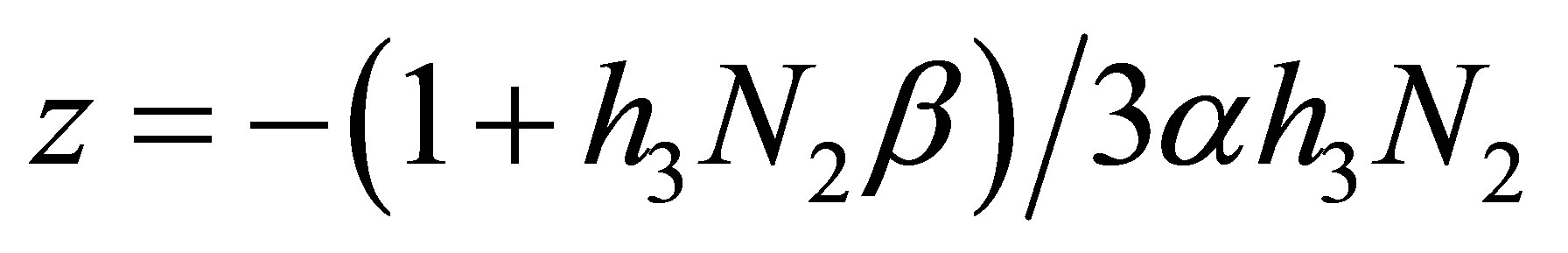

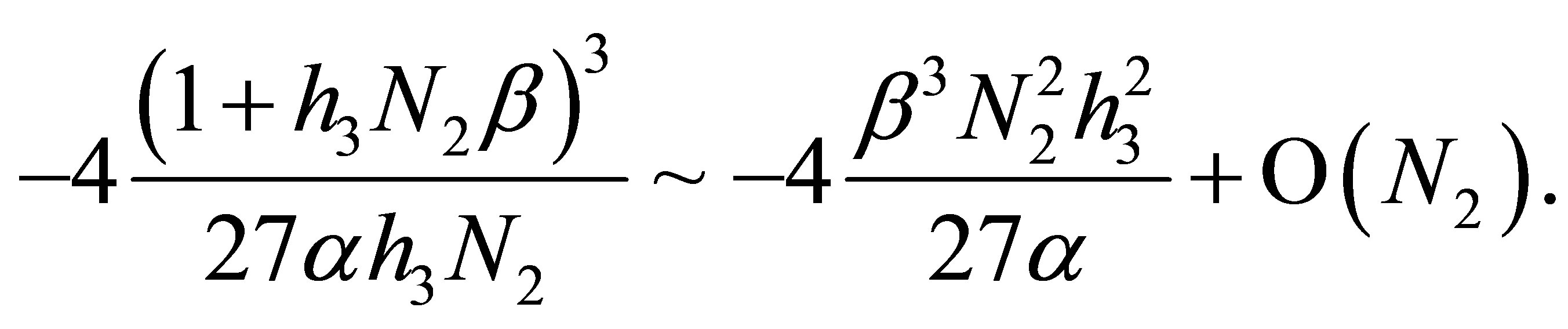

Set

and calculate the minimum of  in I. It is taken at

in I. It is taken at  with the minimum value given by

with the minimum value given by

We recall that  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  Therefore, if

Therefore, if  modulo terms of

modulo terms of  namely

namely

(4.4)

(4.4)

then there appear an attractive equilibrium point  near the origin

near the origin . This means that the predatory efficiency

. This means that the predatory efficiency  is close to a constant function if

is close to a constant function if  is sufficiently small. Indeed, the equilibrium point

is sufficiently small. Indeed, the equilibrium point  can be estimated as

can be estimated as

In view of the linearity of  and the smallness of

and the smallness of  near the equilibrium point we see that

near the equilibrium point we see that  is almost constant for small changes of

is almost constant for small changes of .

.

Suppose now that (4.4) does not hold. Then the attracttive equilibrium point near  disappears, and there remains an attractive equilibrium point near the zero of

disappears, and there remains an attractive equilibrium point near the zero of .Hence the evolution progresses and

.Hence the evolution progresses and  tends to zero. This alternative between the rest and the progress of evolution shows a high contrast to the case of a convex predatory efficiency function discussed in the previous section.

tends to zero. This alternative between the rest and the progress of evolution shows a high contrast to the case of a convex predatory efficiency function discussed in the previous section.

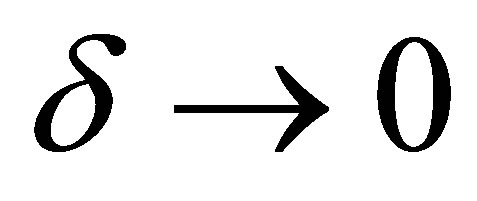

5. Behaviors of Solutions as Cost Increases

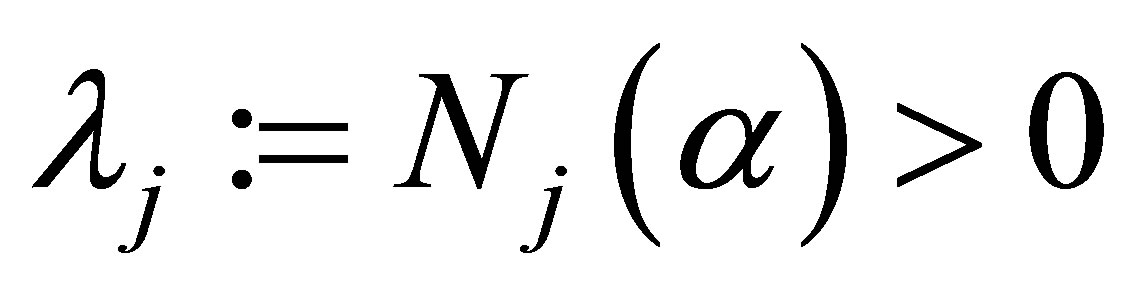

In this section we study the convergence of a solution of an evolutional system to that of a non-evolutional one when the evolutional cost increases, namely  decreases to zero. Let

decreases to zero. Let  and

and  be the solution of (1.1)-(1.4). Let

be the solution of (1.1)-(1.4). Let  be the solution of the non-evolutional system (1.1)-(1.3), namely

be the solution of the non-evolutional system (1.1)-(1.3), namely  Then we have

Then we have

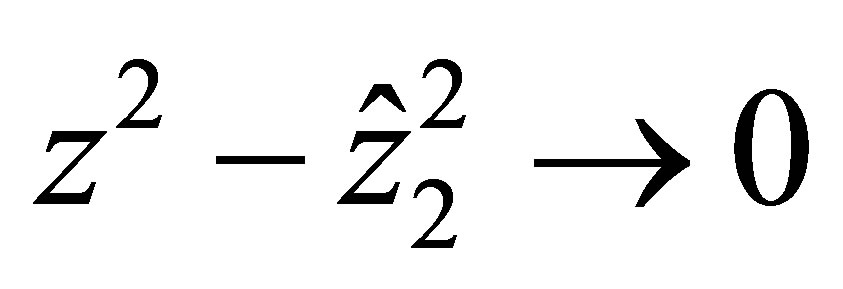

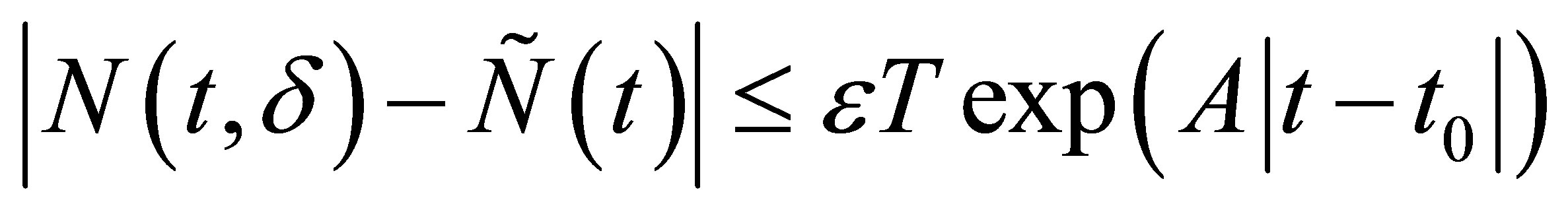

THEOREM 5.1. Assume (2.3). Let  be arbitrarily given. Then we have

be arbitrarily given. Then we have

uniformly in t on

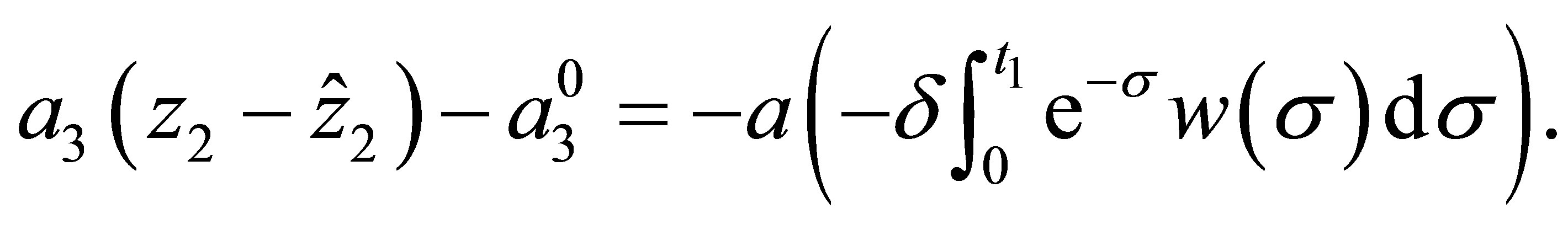

Proof. By integrating (1.4) we have

(5.1)

(5.1)

If we make the change of variables,  , then we have

, then we have

(5.2)

(5.2)

where  and

and

Because  is uniformly bounded in

is uniformly bounded in  by the apriori estimate, it follows that

by the apriori estimate, it follows that  times the integrand is uniformly bounded in

times the integrand is uniformly bounded in  when

when . Hence, the modulus of the integral can be bounded by a constant times

. Hence, the modulus of the integral can be bounded by a constant times  It follows that

It follows that

uniformly in  when

when . This entails that

. This entails that

uniformly in

uniformly in .

.

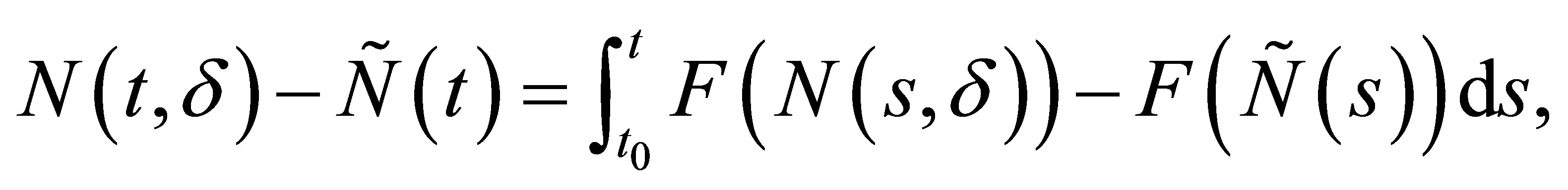

For the sake of simplicity we write (1.1)-(1.3) in

where we use the same notation F as in (2.18). Since

we have

(5.3)

(5.3)

where the absolute value of a vector means the norm of a vector. Because we have the uniform estimate of  in

in  by (1) of Remark in Section 2, we have

by (1) of Remark in Section 2, we have

for some  independent of

independent of .

.

By (1.5) and (5.2) we have

(5.4)

(5.4)

Because  there exists a constant

there exists a constant  independent of

independent of  such that the right hand side of (5.4) can be estimated by

such that the right hand side of (5.4) can be estimated by  It follows that for any

It follows that for any  there exist

there exist  and A>0 such that, for

and A>0 such that, for

Therefore we have

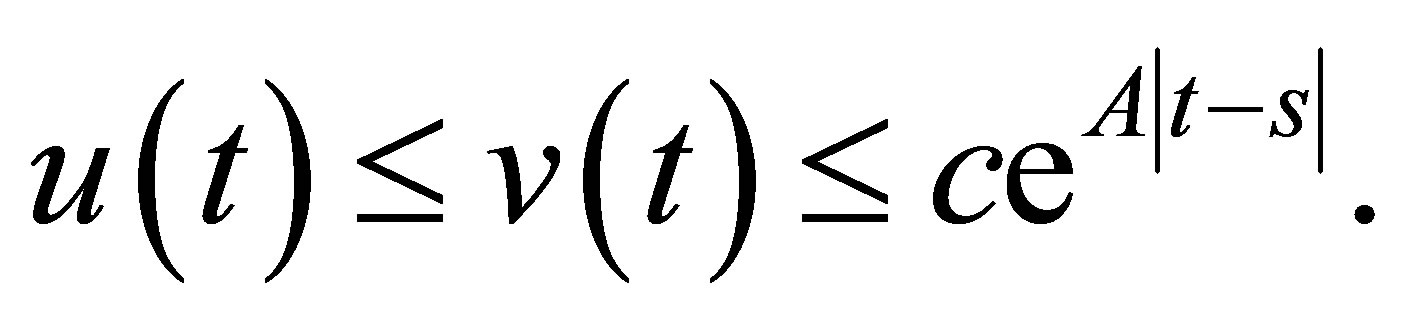

By Gronwall’s inequality we obtain, for

Because  is arbitrary, we have the desired estimate.

is arbitrary, we have the desired estimate.

6. Discussion

Evolutional Lotka-Volterra system does not seem to be well understood analytically except for the case of two species. In this paper, we have studied how the evolutional change of a character influences global behaviors of a Lotka-Volterra system for three species. We introduced an evolutional equation based on a quantitative genetic model into a Lotka-Volterra system of equations and we proved the existence and the uniqueness of a global solution as well as apriori estimates of a solution. By virtue of these properties, we have given analytical proofs of properties which are different from the nonevolutional system. We hope that some of the properties shown in this paper hold for more general food web settings. It is also interesting to make numerical analysis of our theory in order to understand the effect of evolution. The study of these problems will be left for the future study.

REFERENCES

- R. Lande, “Quantitative Genetic Analysis of Multivariate Evolution Applied to Brain: Body Allometry,” Evolution, Vol. 33, No. 1, 1979, pp. 402-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2407630

- R. Lande and S. J. Arnold, “The Measurement of Selection on Correlated Characters,” Evolution, Vol. 37, No. 6, 1983, pp.1210-1226. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2408842

- P. A. Abrams and H. Matsuda, “Prey Adaptation as a Cause of Predator-Prey Cycles,” Evolution, Vol. 51, No. 6, 1997, pp. 1742-1750. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2410997

- P. A. Abrams, “Evolutionay Responses Offoraging-Related traits in Unstable Predator-Prey Systems,” Evolutionary Ecology, Vol. 11, No. 6, 1997, pp. 673-686. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1018482218068

- P. A. Abrams and H. Matsuda, “Fitness Minimization and Dynamic Instability as a Consequence of Predator-Prey Coevolution,” Evolutionary Ecology, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1997, pp. 1-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1018445517101

- Y. Takeuchi, “Global Dynamical Properties of LotkaVolterra Systems,” World Scientific, Singapore, 1996.

- R. A. Fisher, “The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection,” Claredon Press, Oxford, 1930.

Appendix

(A) The following lemma is used in Section 5.

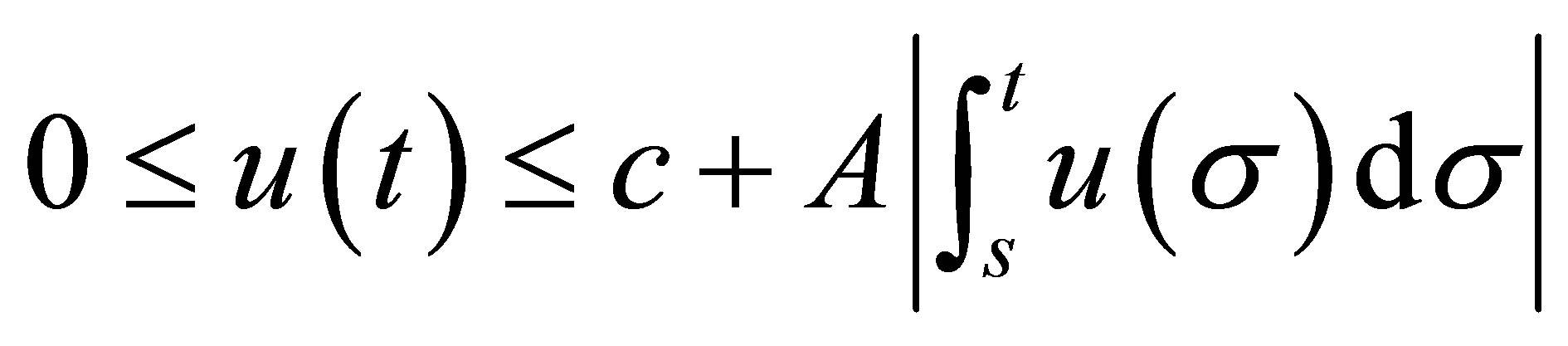

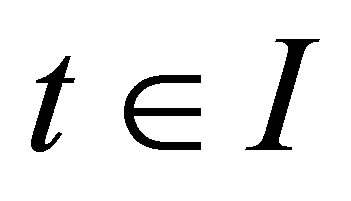

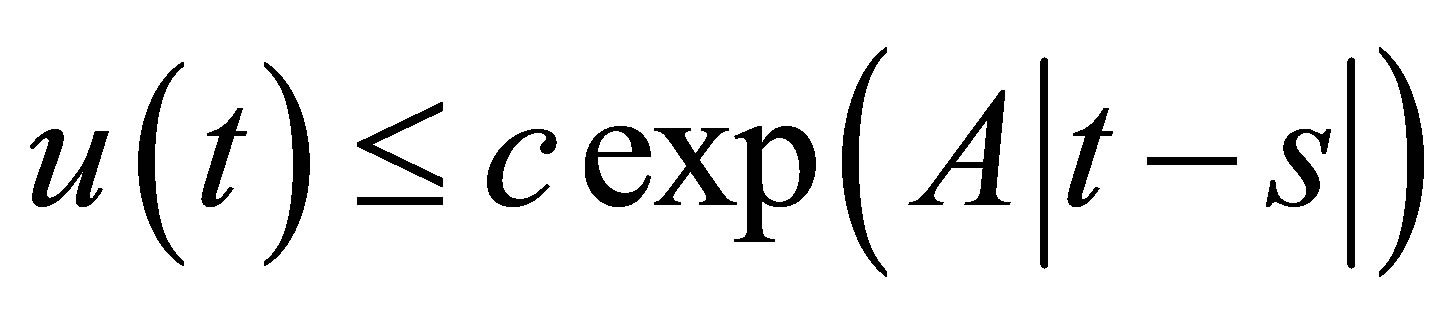

LEMMA. (Gronwall) Let  be a closed interval and let

be a closed interval and let  Let u be continuously differentiable in I such that, for some constants

Let u be continuously differentiable in I such that, for some constants  and

and  the inequality

the inequality

holds true for . Then we have

. Then we have  on I.

on I.

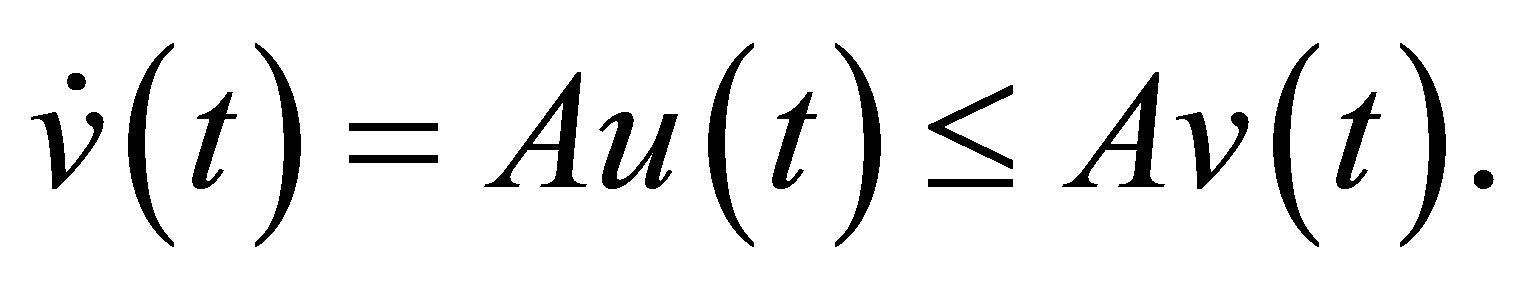

Proof. For the sake of simplicity, we consider the case  Denoting the right hand side of the inequality by v(t) we have the relations,

Denoting the right hand side of the inequality by v(t) we have the relations,

and

and

Multiplying the last inequality with

Multiplying the last inequality with , we have

, we have  By integration we get

By integration we get

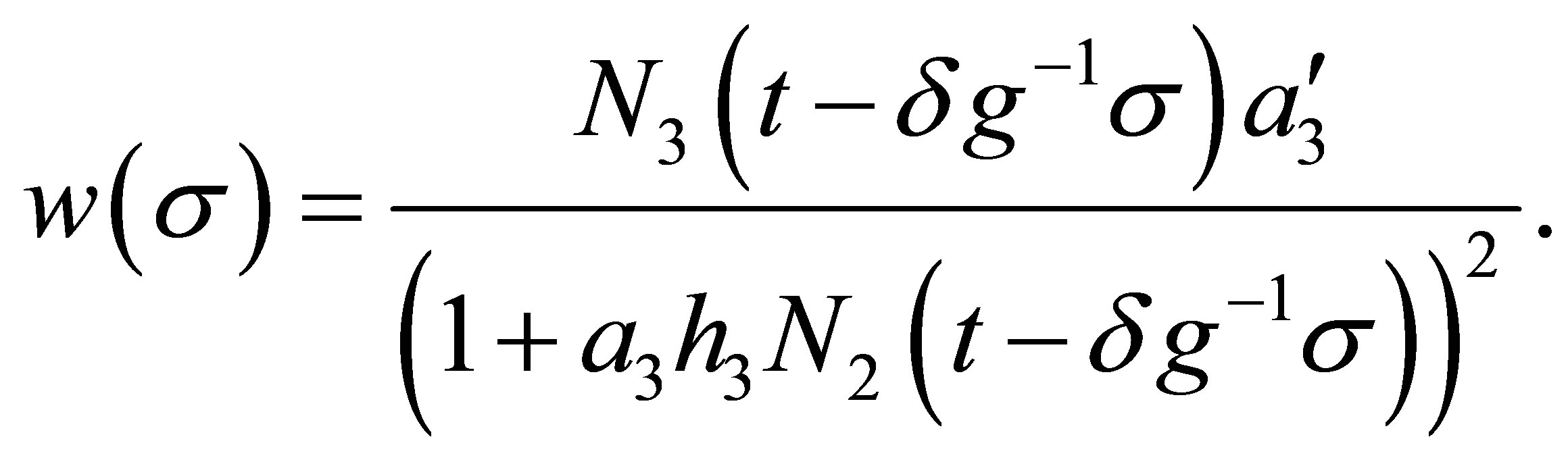

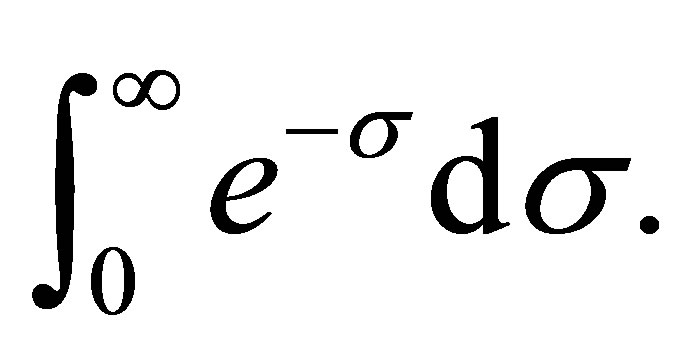

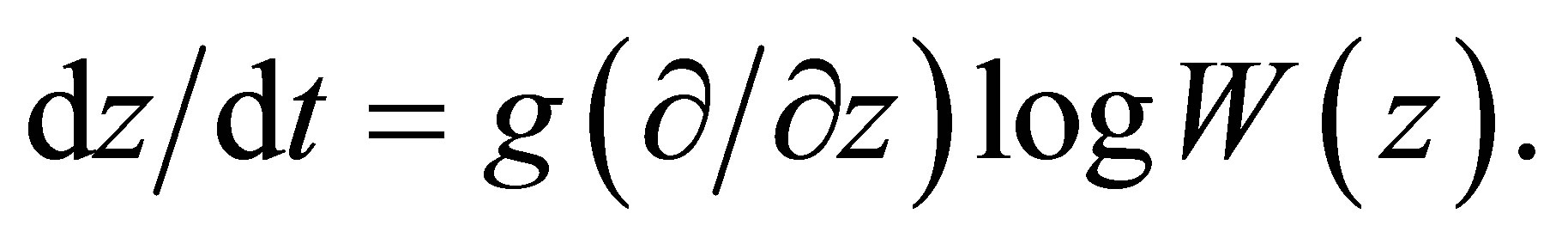

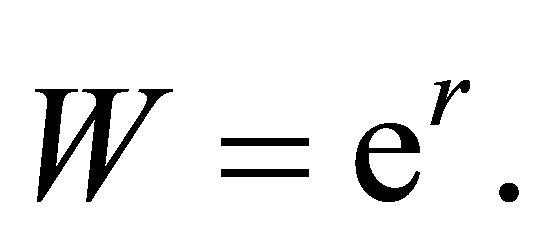

(B) We will briefly show how to deduce (1.4) from the theory of quantitative genetics. Let , g and w be the average character value,the additive genetic variance and the average adaptability of the character value z, respectively. Following the quantitative genetical model we have (cf. [1] and [2]).

, g and w be the average character value,the additive genetic variance and the average adaptability of the character value z, respectively. Following the quantitative genetical model we have (cf. [1] and [2]).

The left-hand side is the speed of evolution of a character value. Following Fisher, [7] we have  We assume that (cf. [3-5])

We assume that (cf. [3-5])

where  is the cost of evolution. By definition we have

is the cost of evolution. By definition we have

(7.1)

(7.1)

Here ,

,  and

and  are certain constants. We have

are certain constants. We have

Because one may regards  as a constant function when z varies, the right-hand side of (7.1) can be replaced by

as a constant function when z varies, the right-hand side of (7.1) can be replaced by

Hence we obtain (1.4).