Advances in Journalism and Communication

Vol.02 No.03(2014), Article ID:50129,11 pages

10.4236/ajc.2014.23012

Decision Making in International Tertiary Education: The Role of National Image

Jing Cai1, Theresa Loo2

1Department of Advertising, School of Communication, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

2Training Department, Ogilvy & Mather, Beijing, China

Email: jcai@comm.ecnu.edu.cn, theresa.loo@ogilvy.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 12 June 2014; revised 16 July 2014; accepted 10 August 2014

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to explore the influence of the national image on the image of its tertiary education among non-nationals and on their choice of location for study. We present a conceptual model of how the image of the nation impacts on the image of tertiary education based upon Ajzen & Fishbein’s (1980) “theory of reasoned action”. With data from China & India, a model is developed from a calibration sample and tested against a validation sample using structural equation modelling. The model fits the data well and shows that a national image for Chic (prestigious, refined, elegant) and Enterprise (innovative, cool, trendy) has a positive influence on the beliefs about, attitudes towards and propensity to consume tertiary education offered by the UK. Our work indicates that there will be mileage in investing not just on the image of education itself, but on the image of the nation in the promotion of international tertiary education.

Keywords:

Country of Origin, International Tertiary Education, Nation Brand, National Image, National Reputation, Place Brand

1. Introduction

The market for international tertiary education services is large and developing. Host countries are inducing “imports” of students while “exporting” their education services in the form of, for example, twinning programmes, distance learning and offshore campuses. In a globalized marketplace, where the competition among products and services is severe, there is a need to differentiate to maintain competitive advantage and the image of the nation is a potentially powerful cue for tertiary education providers to position themselves differently from their international competitors.

In this paper, our aims are to explore the influence of the national image on the image of its tertiary education among non-nationals and on their choice of location for study. We present a conceptual model of how the image of the nation impacts on the image of tertiary education that a country provides based upon Ajzen & Fishbein’s (1980) “theory of reasoned action” and we refine and test this with empirical data from China & India.

2. International Tertiary Education

The predominant trend in international tertiary education has been an increasing flow of students from developing to developed countries. Students go abroad to study because they are interested in the advanced degrees and the promise of individual advancement that education provides (McMahon, 1992). Furthermore, they are interested in the higher prestige offered by a foreign degree. They expect higher lifetime income and an ability to raise their economic and social status after graduation. In this sense, students are not just buying degrees; they are buying the benefits that a degree can provide in terms of opportunity for employment and social advancement. On the side of the host nation, overseas students are welcomed because their participation enriches the learning environment for both students and faculty. They also bring in a substantial amount of fee income to the university while contributing to the economy of the host nation via spending in the local communities. Furthermore, when they go back to their home countries, they act as ambassadors for the host country.

Services differ from products in four ways: intangibility, heterogeneity, inseparability of production and consumption and perishability (Dotchin & Oakland, 1994; Zeithaml et al., 1985; Shostack, 1977). While many services have associated products, tertiary education is mainly intangible in nature and it is characterized by a high degree of interpersonal contact, complexity and customization (Owalia & Aspinwall, 1996; Shostack, 1982; Rushton & Carson, 2001). There are no physical products, although it has tangible goods inseparable from its provision, such as lecture notes distributed by professors and diplomas awarded at the completion of a university degree. It is also difficult to evaluate the service before its consumption, as the production and consumption of international tertiary education are simultaneous and inseparable (Zeithaml et al., 1985). Teaching and learning are inextricably intertwined. Students are involved in the production of the learning experience. When students enrol in a university programme, they interact with the university faculty and other students, at once learning from the professors and helping one another to learn (Harvey & Busher, 1996). Students play the multiple roles of consumer, participant in the education process and end product at the completion of the degree. Heterogeneity is another hallmark of education (Owalia & Aspinwall, 1996) because it is difficult to standardize the distribution of knowledge. An MBA for example can be both a two-year full time program or a one-year part time program. Due to the importance of the human element, the actual experience and quality also varies markedly from class to class, lecturer to lecturer. Lastly, international tertiary education is characterized by perishability. If a student misses a class or an exam, it is gone. Even if the student is allowed a chance to repeat the class or retake the exam, it is not the same as the first one.

So complex are these interactions of people, process and environment that there is a great deal of uncertainty involved when students are in the process of selecting an institution for tertiary education. This uncertainty is further compounded by the far-reaching impact of tertiary education as students are long-term stakeholders of their education provider. The allure of a university stems not just from the knowledge it can impart or the education experience it provides, but also from the perception of what it stands for its prestige, ideology and reputation. Students are looking for benefits such as employment, status, lifestyle from their university education (Binsardi & Ekwulugo, 2003). Their own image and that of the school from which they attain their qualifications are intertwined (Davies & Chun, 2002) as the image of the school is going to be a door opener for graduates when they enter the job market. It is also going to be a badge of honour (I come from an Ivy League school) or a membership card (I am a Harvard alumnae/alumnus) for the rest of the student’s life as s/he moves around in the world of employment and in society. Selecting an institution for tertiary education is often one of the most significant and expensive decisions that students and their families have to make (Mazzarol, 1998). There is a high degree of risk associated with such purchasing decisions and a great deal of consideration goes into the decision making of the purchase.

3. The Decision Making Process and Research Hypotheses

Due to the intangibility and heterogeneity inherent in international tertiary education, there is no reliable way to know the quality of the education that will be received prior to entering the university. Students can only fall back on cues, such as the physical outlook of the campus or the calibre of its faculty, as indications of what their education experience might be like. This lack of reliable measurements to gauge the quality of education makes it most difficult for potential students to decide on which university to choose (Harvey & Busher, 1996).

When intrinsic cues are unknown or not available, consumers often evaluate products and services by using extrinsic cues, such as reputation of the institution, or the country of origin of a product or service (Ahmed & d’Astous, 1996; Bilkey & Nes, 1982; Chao, 1989). A well-known brand name and a reputation for quality are consequently significant sources of competitive advantage (Aaker, 1996) for a marketer. It is often the university’s perceived excellence which guides the decisions of prospective students and staff (Kotler & Fox, 1995). The success of Ivy League institutions is linked to their image and reputation regardless of their teaching quality (Huber, 1992).

Another important influence on the choice of university is the image of the country in which the university is situated (e.g. Bourke, 2000; Kinnell, 1989), or the so called country of origin effect. Some countries have a good reputation for education, e.g. the US and the UK, and students tend to believe that tertiary education provided by these countries is of high quality (Bourke, 2000). There are also countries where different inferences are made. In one study, Japanese and American students perceived Australia as a place of “beaches and fun”, but not somewhere to undertake “serious” education (AGB, 1992 in Mazzarol & Soutar, 2002). Students use a nation’s image to categorize information, reduce perceived risk and manage the social acceptability of their purchases (Papadopoulos et al., 1990).

Many students choose the host country for study before selecting the host institution (Bourke, 2000; McMahon, 1992). The image of the nation in which the university is located is used as a signal of quality and influences a student’s choice of international tertiary education (Srikatanyoo & Gnoth, 2002) much as the country of origin effect influences the purchase of a physical product, such as a motor vehicle. Recognizing this, Canadian providers of English courses use the national image of “natural beauty, clean air and safe environment” as a sell- ing proposition to position Canada as a unique location for learning English over their Australian and American competitors (Ferguson, 2001).

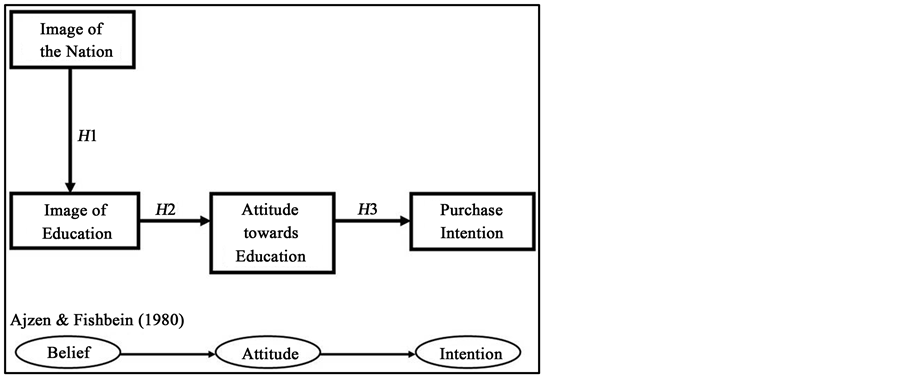

The “theory of reasoned action” (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) implies that consumer behaviour can be predicted from a sequence of linked cognitive constructs (Foxall et al., 2001): belief à attitude à intention. The summed set of beliefs about an object’s attributes affects attitude towards the object. Attitude plays an important role in consumer behaviour because it constructs the way consumers perceive their environment, guides the ways in which they respond to it and affects intention to purchase (Blackwell et al., 2001). Applying this to decision making about where to study, we would expect the image of the nation to influence the student’s belief about its education services, which in turn influences attitude towards those services. The attitude towards the education service influences propensity to choose a university in that country.

Hence, the following hypotheses were formulated for testing (see Figure 1):

Figure 1. Conceptual model of how the image of the nation affects the purchase intention of international tertiary education.

H1: Image of the nation is a significant and positive predictor of image of education.

H2: Image of education is a significant and positive predictor of attitude towards education.

H3: Attitude towards education is a significant and positive predictor of intention to study in the host country.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sample

The context for our empirical study was the United Kingdom, which has a thriving international tertiary education industry. We chose China and India as the locations for our surveys because Chinese and Indian students are major consumers of British tertiary education. With a headcount of 66,050 in the academic year 2011/2012, Chinese students represented the largest student minority in the UK. Indian students, totalling 24,030 in number, came next in the ranking (HESA, 2013).

Students from China go abroad to study after their bachelor degree, while students from India interested in pursuing postgraduate work in the UK have to engage in one year of postgraduate studies in their home country before they can apply to a postgraduate programme in the UK. Therefore, undergraduate and postgraduate students in Shanghai and New Delhi were chosen as the Chinese and Indian samples respectively. Students were approached during or after class on university campuses in the two locations. A structured questionnaire was prepared and piloted in English and translated into Chinese using the back translation method. It was administered in Chinese for the Chinese sample and in English for the Indian sample. Recruitment quotas for gender and level of study were established, with proportional allocation of students to each of those criteria (see Table 1). In China, out of a total number of 479 students approached, 438 agreed to participate in the survey, a response rate of 91.4%. In India, among the 440 questionnaires distributed, 435 questionnaires were returned, a response rate of 98.9%. Questionnaires with more than 10% missing values were discarded. Out of the 438 questionnaires collected from China, 429 were usable (overall response rate of 89.6%) while all the 435 questionnaires collected from India were usable (overall response rate of 98.9%). The total sample size for data analysis was 864.

4.2. Instrument

Image of the nation. Countries and companies are becoming more like each other in their marketing (Olins, 1999; Graby, 1993), hence research tools for measuring corporate reputation can be adapted to measure the reputation of a nation (Passow et al., 2003; Davies & Loo, 2006). This study adapted such a scale by Davies et al. (2003) for measuring the image of the nation. The measure adopts a projective technique and respondents were asked to imagine that the nation “has come to life as a human being” and to rate it for each item using a 5-point, Likert- type scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The scale is multidimensional with a number of items used to assess each dimension: Agreeableness (e.g. honest, open, pleasant), Enterprise (e.g. cool, up to date, innovative), Competence (e.g. reliable, leading, secure), Chic (e.g. stylish, prestige, elitist) and Ruthlessness (e.g. arrogant, aggressive, inward looking).

Table 1. Sample profile.

In the absence of an existing scale for beliefs and attitudes towards education, measurement scales and extant literature on education, place branding, marketing and country of origin were consulted. The items were then confirmed in interviews with 8 experts involved either professionally or academically with the marketing of international tertiary education.

Belief about education. To measure the image of education, an 18-item, 5-point Likert-type scale was developed from extant literature (e.g. Srikatanyoo & Gnoth, 2002; Bourke, 2000), e.g. “the UK has high standards in selecting students”. The scale was anchored at 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree.

Attitude towards education. Attitude towards education was measured by a 3-item scale which aimed to measure the cognitive, affective and conative components of attitude: “Please indicate your overall satisfaction with the UK as provider of tertiary education”, “I would recommend the UK as a provider of tertiary education to my colleagues or friends” and “I have an affinity with the UK as provider of tertiary education”. A 5-point, Likert-type scale was used, with the first question ranging from 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = highly satisfied and the last two questions anchored as per the measurements of the image of the nation.

Purchase intention. A single-item measure, with a 5-point, Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 = highly unlikely to 5 = highly likely, was used: “How likely are you to further your tertiary education in the UK in the next 5 years?”

5. Model Testing & Results

Structural equation modeling was used to develop and refine the conceptual model. In such circumstances, Jöreskog (1993) pointed out that models obtained via modifications might have been derived to some extent by “capitalising on chance” (i.e., data mining). Therefore, he recommended that the final model be cross-validated on independent data. This was also to make sure that data idiosyncrasies were not misleading the research results. Furthermore, the extent to which the model fits the data with an independent data set provided some evidence of the generalisability of the model (Bullock et al., 1994). The total sample size of 864 was therefore randomly split up into a calibration sample (n = 433), consisting of half Chinese and half Indians for developing the model, and a validation sample (n = 431) for cross-validation (see Table 2).

With the calibration sample of, factor analysis using principal component analysis with orthogonal rotation (varimax) was conducted on each of the constructs and their reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. Items not making a positive contribution to a scale were eliminated. Factors that were below the cut- off value of .60 for exploratory research (Nunnally, 1967; Slater, 1995) were also dropped from further analysis. As a result, Ruthlessness, with a Cronbach’s coefficient alpha below .6, implying that this dimension was not reliable in the context of a nation’s image, was dropped. In the end, four national image factors, two education factors and “affinity with education” were retained (see Table 3).

Structural equation modeling was then performed with AMOS using the Maximum Likelihood method on the calibration sample. A two-step process was adopted; confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using the measurement models before testing the structural model (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The initial measurement models for the national image and education constructs did not fit the data well and the models were re-specified. Standardised residuals and modification indexes were examined to guide the re-specification (Hatcher, 1994; Byrne, 2001) until well-fitted measurement models were obtained. The next step was to specify the structural model of how the national image of the UK affects the image of the nation’s tertiary education. The measurement models were combined together to form the theoretical model to be tested as per Figure 1. The initial structural model did not fit the data well and the model was re-specified. As a result, the Agreeableness and Competence factors of the national image construct and the Support factor of the education construct were eliminated. The factors making up the final structural model and the items representing them are presented in Table 4.

Table 2. Split-up of samples.

Table 3. Test of scale reliability.

Table 4. Constructs, factors and items of the final structural model.

The final structural model after re-specification is presented in Figure 2. The data fitted the model well (X2(61) = 97.97, p = .002), fit indices (GFI = .967, AGFI = .950, CFI = .963 and TLI = .953, RMSEA = .037, Hoelter N (.01) = 396) were all better than the recommended levels.

The final structural model was cross-validated by re-running the model with the validation sample (n = 431). The Chinese sample (n = 429), the Indian sample (n = 435) and total sample (n = 864) were also used to cross-validate the model independently. Table 5 is a summary of the fit indexes for the calibration, validation, Chinese, Indian and total samples. The fit indices for all the models used for validation, except those for the total sample, are slightly lower than those for the calibration model, but all are within recommended limits.

Figure 2. Final structural model of how the image of the nation affects the purchase intention of international tertiary education.

Table 5. Summary of fit indexes of calibration, validation, Chinese, India and total samples.

Having identified a valid model, we then tested the hypotheses by examining the standardized parameter estimates for each relationship (see Table 6). This was done from the final structural model using the calibration data set. H1, which proposed that the image of the nation was a significant and positive predictor of the image of the nation’s tertiary education (r = .234, p < .001), was supported. H2, that education was a significant and positive predictor of affinity with education (r = .133, p < .001) was also supported by the data. H3, which stated that attitude towards education was a significant and positive predictor of intention to study in the UK (r = .091, p < .001), was also supported.

Table 6. Standardized parameter estimates.

Note: ***Significant at .001; X2(61) = 97.97, p = .002, GFI = .967, AGFI = .950, CFI = .963 and TLI = .953, RMSEA = .037.

In Figure 2, the numbers in bold are standardised regression weights. The numbers in italics inside the brackets beside the latent variables are squared multiple correlations (R2), which represent the proportion of variance that is explained by the predictors of the variable in question. Take for example, 52% of the variance in the image of education (as in “quality”) is explained by the image of the nation. When all the effects are taken together, the model accounted for 11% of the variance in “intention to study in the UK”. Enterprise and Chic were the two dimensions of the UK national image that drove the image of UK education, leading to affinity with education and finally intention to study in the UK. Respondents that rated the nation’s image high were more likely to consume its education.

The decomposition of structural effects into direct and indirect effects (see Table 7) provided a more in-depth understanding of how the image of the nation impacts on students’ intention to study in the UK. Conceptually, the direct effects represent causal effects of one variable on another while indirect effects involve mediator variables that “transmit” a portion of the effect of a prior variable onto a subsequent one (Kline, 1998). The image of the nation has an indirect effect on affinity with education (.547) and intention to study in the UK (.185) while the image of education has an indirect effect on intention to study in the UK (.257).

While the image of education has the strongest direct and indirect effect on affinity with education and intention to study in the UK respectively, the indirect effect of the national image on “affinity with education” (.547) is also strong, which supports the argument that the image of the nation casts a halo effect on the image of the nation’s tertiary education. This is in tandem with findings from other research in country of origin literature (e.g. Sauer et al., 1991; Knight & Calantone, 2000), which suggest that both the image of the nation and the image of the nation’s outputs influence consumers’ affinity with the outputs simultaneously. However, there was no suggestion in the analysis of a direct link from the “image of the nation” to “affinity with education”, implying that its influence is fully mediated via a person’s beliefs about that education. This is in accordance with Erickson et al. (1984), which indicated that country of origin affects beliefs, but not attitudes.

Table 7. Summary of standardised direct and indirect effects.

6. Discussion and Implications

We have provided empirical evidence to show that the image of a nation can contribute to the image of the nation’s tertiary education in the international arena. Our findings show that both the image of the nation and the image of education affect the interest of overseas students to study in the UK. There is mileage in setting policies to enhance image at both levels.

The relevant aspects of the UK national image are Chic and Enterprise. Chic is indicated by “elegant”, “prestigious” and “refined”, representing the traditional image of the UK, while Enterprise is indicated by “cool”, “trendy” and “innovative”, representing the modern image of the nation. It seems that in the minds of Chinese and Indian young adults, the image of the UK is a mixture of the traditional and the new. At first glance, the dichotomy of the UK being steeped in heritage/tradition while at the same time characterized by innovation/ trendiness, might be a cause for concern. Hiscock (2002) aptly commented that the UK presented “… a confusing image to the outside world, and domestically. On one hand the nation is famed for its traditions; on the other, a new and more enterprising personality has been gradually emerging. This very British dichotomy is exemplified in brand pairings such as Jaguar and Mini, Crabtree & Evelyn and The Body Shop, British Airways and Virgin” (p. 16). However, it is only natural for a nation’s image to consist of paradoxes given the complexity of a nation (Silver & Hill, 2002) and we would argue that the dichotomy of the two different dimensions of the image of the UK is an opportunity rather than a problem.

Chinese young adults had been exposed to a number of promotional campaigns by the UK government (e.g. Britain at the Leading Edge, 2002, Think UK1), which aimed to show that innovative and creative thinking were core to the UK (FCO, 2003). Therefore, on top of the traditional image of the UK, Chinese young adults now see the UK as Enterprising. Nonetheless, images of the traditional UK still linger. Given these “conflicting” images, it is therefore not surprising that the UK is perceived as both Chic and Enterprising among young Chinese. As for the Indians, given their past colonial ties with the UK, they are living in this dichotomy of British traditions and modernity. An example of the best of British traditions still embedded in the everyday lives of the Indians is their own educational institutions, founded by the British. Schools, such as The Sacred Heart, are still seen as providing the best and most prestigious education one can have in India.

The UK is a country of astonishing diversity and creativity (Smith, 2003) and both the images of heritage and trendiness carry elements of truth. Rather than denying past glories and focusing mainly on the modern, as in “Cool Britannia”2 and “Think UK”, authorities promoting UK tertiary education can leverage this paradox in their communication programmes. It is a matter of finding the right stories and examples to juxtapose the Chic and Enterprise images of the UK, thus bringing the national image to life in the marketing of education. Take for example the University of Manchester, which can benefit from its association with the city from which the Industrial Revolution originated and its longstanding by comparison with many British universities by using its positioning as “established in 1824” to evoke the tradition and status of British education. At the same time its business school was one of the first to be established in Britain and credited with developing an experiential approach the “Manchester Method”, a project-oriented and learn-by-doing approach to business education studies which has since been adopted by other MBA programmes worldwide. Such associations bring out an image of being Enterprising.

On a macro level, the finding that the image of the nation has an impact on attracting overseas students to the country to study has implications for policy making. Many host countries already have a national agency or centralized body (e.g., British Council, Austrade) to promote the nation’s educational offerings overseas (Bourke, 2000). Our work indicates that there will be mileage in investing at a higher level, the national image level. Choosing a university is a major and expensive decision for overseas students. It is easy for them to fall back on a “safe” option, such as a host country with a good national image and a good reputation for providing quality education. A major factor that explains the popularity of the US as a host country for international tertiary education is its dominance of the world’s media, news services and the entertainment industries, making the nation known throughout the world (Mazzarol & Soutar, 2002). The better knowledge or awareness a student has of a particular host country, the more likely they will select it as a study destination. The UK Government can contribute to international tertiary education development efforts by improving the country’s overall image in the international arena.

Since the image of education has a strong direct impact on attitude towards education, our findings also argue for co-ordinated attempts by universities to establish a broad market presence in order to raise overall knowledge about UK educational capabilities at the industry level, such as a “study in the UK campaign”. The UK government has already taken a proactive stance in response to the increase in competition. The “Education UK” brand campaign, launched in 2000, is part of the initiative of the British government to attract more international students (British Council, 2001) through positioning British education as the best in quality and promoting UK as the world’s leading nation in international education (Binsardi & Ekwulugo, 2003).

The 3 items making up the “quality” factor that constitute the relevant image of education are “high quality faculties”, “high rankings in media surveys” and “high standards in selecting students”. These items are in line with findings in other research (e.g. Mazzarol & Soutar, 2002) and can be worked on to improve the image of UK education generally. Programmes aiming to improve these items will lead to an increase in affinity with UK education, hence increasing purchase intention.

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building Strong Brands. New York: Free Press.

- AGB (1992). International Competitiveness Study. Canberra: Education Information and Publication.

- Ahmed, H. D., & d’Atous, A. (1996). Country of Origin and Brand Effects: A Multi-Dimensional and Multi-Attribute Study. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 9, 93-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J046v09n02_05

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing D. W. (1988). Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411-423. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Bilkey, W. J., & Nes, E. (1982). Country of Origin Effects on Product Evaluation. Journal of International Business, 13, 89-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490539

- Binsardi, A., & Ekwulugo, F. (2003). International Marketing of British Education: Research on the Students’ Perception and the UK Market Penetration. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 21, 318-327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02634500310490265

- Blackwell, R. D., Miniard, P. W., & Engel, J. F. (2001). Consumer Behavior. Texas: Harcourt College Publishers.

- Bourke, A. (2000). A Model of the Determinants Of international Trade in Higher Education. The Service Industries Journal, 20, 110-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02642060000000007

- British Council (2001). New Increase in Overseas Students in UK Higher Education. http://www.britishcouncil.org/ecs/news/2001/0502

- Bullock, H. E., Harlow, L. L., & Mulaik, S. A. (1994). Causation Issues in Structural Equation Modelling Research. Structural Equation Modeling, 1, 253-267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10705519409539977

- Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Chao, P. (1989). The Impact of Country Affiliation on the Creditability of Product Attribute Claims. Journal of Advertising Research, 29, 35-41.

- Davies, G., & Chun, R. (2002). Branding a Business School. The 6th International Conference on Corporate Reputation, Seminar, Boston.

- Davies, G., & Loo, T. (2006). Nation Branding: How the National Image of the United Kingdom Influences the Attractiveness of Its Outputs. The Academy of International Business Annual Meeting, Beijing.

- Davies, G., Chun, R., da Silva, R. V., & Roper, S. (2003). Corporate Reputation and Competitiveness. London: Routledge.

- Dotchin, J. A., & Oakland, J. S. (1994). Total Quality Management in Services: Part 1: Understanding and Classifying Services. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 11, 9-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02656719410056459

- FCO (2003). Think UK, China 2003. http://www.fco.gov.uk

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Foxall, G., Goldsmith, R., & Brown, S. (2001). Consumer Psychology for Marketing. London: Thomson Learning.

- Graby, F. (1993). Countries as Corporate Entities in International Markets. In N. Papadoupolos, & L. Heslop (Eds.), Product-Country Images: Impact and Role in International Marketing (pp. 257-283). New York: Haworth Press.

- Harvey, J., & Busher, H. (1996). Marketing Schools and Consumer Choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 10, 26-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513549610122165

- Hatcher, L. (1994). A Step-by-Step Approach to Using the SAS System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute.

- Hiscock, J. (2002). What Makes a Brand British? Marketing, 16.

- Huber, R. M. (1992). Why Not Run a College Like a Business? Across the Board, 29, 28-32.

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1993). Testing Structural Equation Models. In K. A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing Structural Equation Models (pp. 294-316). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kinnell, M. (1989). International Marketing in UK Higher Education: Some Issues in Relation to Marketing Educational Programmes to Overseas Students. European Journal of Marketing, 23, 7-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000000566

- Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Knight, G. A., & Calantone, R. J. (2000). A Flexible Model of Consumer Country-of-Origin Perceptions: A Cross-Cultural Investigation. International Marketing Review, 17, 127-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02651330010322615

- Kotler, P., & Fox, K. (1995). Strategic Marketing for Educational Institutions. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Mazzarol, T. (1998). Critical Success Factors for International Education Marketing. International Journal of Educational Management, 12, 163-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513549810220623

- Mazzarol, T., & Soutar, G. (2002). Push-Pull Factors Influencing International Student Destination Choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 16, 82-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513540210418403

- McMahon, M. E. (1992). Higher Education in a World Market: An Historical Look at the Global Context of International Study. Higher Education, 24, 465-482. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00137243

- Nunnally, J. C. (1967). Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Olins, W. (1999). Trading Identities. London: The Foreign Policy Centre.

- Owalia, M. S., & Aspinwall, E. M. (1996). A Framework for the Dimensions of Quality in Higher Education. Quality Assurance in Education, 4, 12-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684889610116012

- Papadopoulos, N., Heslop, L. A., & Bamossy, G. J. (1990). A Comparative Image Analysis of Domestic versus Imported Products. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 7, 283-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-8116(90)90005-8

- Passow, T., Fehlmann, R., & Grahlow, H. (2003). The Country Reputation Cockpit: Translating Reputation Measurement into Reputation Management. The 7th International Conference on Corporate Reputation, Identity and Competitiveness, Manchester.

- Rushton, A., & Carson, D. (2001). The Marketing of Services: Managing the Intangibles. European Journal of Marketing, 19, 19-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004748

- Sauer, P., Young, M., & Unnava, H. (1991). An Experimental Investigation of the Processes behind the Country of Origin Effect. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 3, 29-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J046v03n02_04

- Shostack, G. L. (1977). Breaking Free from Product Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 41, 73-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1250637

- Shostack, G. L. (1982). How to Design a Service? European Journal of Marketing, 16, 49-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004799

- Silver, S., & Hill, S. (2002). Marketing: Selling Brand America. Journal of Business Strategy, 23, 10-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb040255

- Slater, S. F. (1995). Issues in Conducting Marketing Strategy Research. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 3, 257-270. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09652549500000016

- Smith, C. (2003). Beyond Cool Britannia. Locum Destination Review, 12, 4-7.

- Srikatanyoo, N., & Gnoth, J. (2002). Country Image and International Tertiary Education. The Journal of Brand Management, 10, 139-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540111

- Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). Problems and Strategies in Services Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 49, 33-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1251563

NOTES

1Think UK—An initiative by the Foreign & Commonwealth Office to bring a variety of British innovators, performers and personalities to China to showcase the creative and innovative ideas from contemporary Britain, and to strengthen links between young people in the two countries.

2Cool Britannia—A term coined by the press to describe the effort by the Tony Blair government to promote the creative industries of contemporary Britain, which accounts for a substantial part of the nation’s economy, to the international arena.