American Journal of Analytical Chemistry

Vol.4 No.10A(2013), Article ID:37313,9 pages DOI:10.4236/ajac.2013.410A1005

Thermogravimetric Analysis of Zirconia-Doped Ceria for Thermochemical Production of Solar Fuel

1German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Solar Research, Köln, Germany

2German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Material Research, Köln, Germany

3Total RM—New Energies, La Defense Cedex, Paris, France

Email: *friedemann.call@dlr.de, martin.roeb@dlr.de, christian.sattler@dlr.de, robert.pitz-paal@dlr.de, martin.schmuecker@dlr.de, helene.bru@total.com, daniel.curulla-ferre@total.com

Copyright © 2013 Friedemann Call et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received July 14, 2013; revised August 15, 2013; accepted September 9, 2013

Keywords: Water Splitting; CO2 Splitting; Thermochemical Cycle; Ceria; CO; Solar Fuels; Hydrogen; H2; Zirconia; Synthesis Gas

ABSTRACT

Developing an efficient redox material is crucial for thermochemical cycles that produce solar fuels (e.g. H2 and CO), enabling a sustainable energy supply. In this study, zirconia-doped cerium oxide (Ce1−xZrxO2) was tested in CO2-splitting cycles for the production of CO. The impact of the Zr-content on the splitting performance was investigated within the range 0 ≤ x < 0.4. The materials were synthesized via a citrate nitrate auto combustion route and subjected to thermogravimetric experiments. The results indicate that there is an optimal zirconium content, x = 0.15, improving the specific CO2-splitting performance by 50% compared to pure ceria. Significantly enhanced performance is observed for 0.15 ≤ x ≤ 0.225. Outside this range, the performance decreases to values of pure ceria. These results agree with theoretical studies attributing the improvements to lattice modification. Introducing Zr4+ into the fluorite structure of ceria compensates for the expansion of the crystal lattice caused by the reduction of Ce4+ to Ce3+. Regarding the reaction conditions, the most efficient composition Ce0.85Zr0.15O2 enhances the required conditions by a temperature of 60 K or one order of magnitude of the partial pressure of oxygen p(O2) compared to pure ceria. The optimal composition was tested in long-term experiments of one hundred cycles, which revealed declining splitting kinetics.

1. Introduction

Synthesis gas (or syngas)—primarily a mixture of H2 and CO—is one of the most promising sustainable energy carriers when produced from renewable resources. It offers an exceptional energy density and is a universal precursor for the production of a very broad variety of chemical substances like polymers, or methanol and especially gaseous and liquid synthetic fuels via the Fischer-Tropsch synthesis, and related processes [1-3]. Syngas can also be combusted for electricity generation in highly efficient combined Brayton-Rankine cycles [4].

Today, syngas is mainly produced by steam or dry (CO2) reforming or partial oxidation of fossil resources, mainly natural gas, accompanied by a substantial emission of greenhouse gases [5-7]. For a transition away from fossil energy, several processes have been developed that produce syngas from renewable sources (CO2, water) employing solar energy to cover the reaction heat [8,9]. These processes meet the demands of a secure, clean and sustainable energy supply converting solar energy into transportable and dispatchable fuels [10] referred to as solar fuels.

The direct method to produce syngas from solar thermal energy is the thermolysis of water and CO2 molecules in a single step. This prevents energy losses during material handling and exhibits the closest match between the theoretically required solar energy and the energy released by utilizing the produced fuel. On the downside, the equilibrium constant for thermolysis of water and CO2 is not unity at temperatures less than approximately 4000˚C [11,12]. Reasonable H2 or CO production yields via thermolysis require at least temperatures of about 2000˚C [12,13] and/or a significantly reduced partial pressure of oxygen. Besides the challenges for the reactor construction caused by these impractical temperatures, direct thermolysis produces a mixture of H2 and O2 or CO and O2, requiring high-temperature gas separation [8].

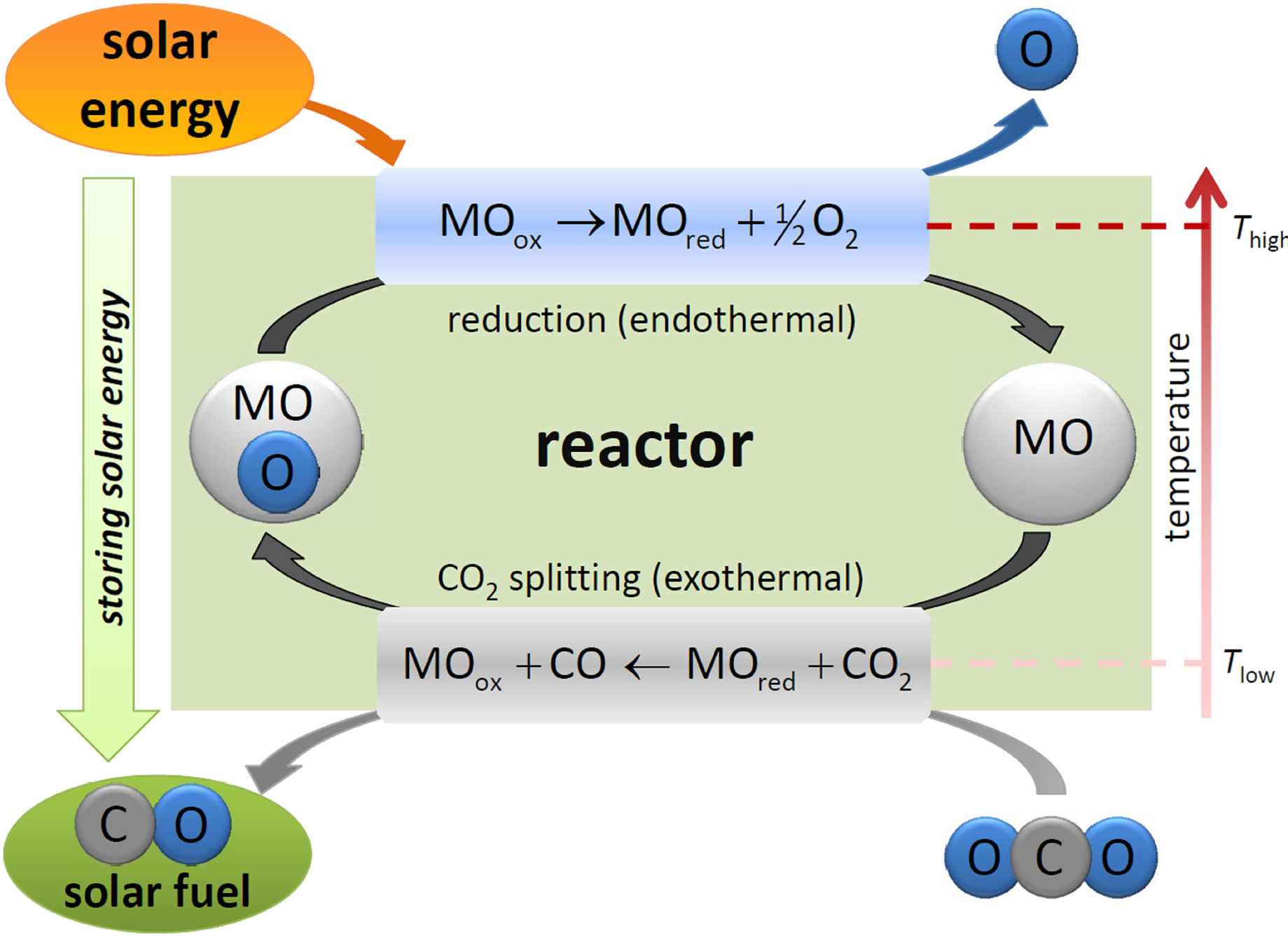

Thermochemical two-step cycles based on metal oxides that operate at significantly lower temperatures have drawn great attention in the last decades [14-18]. The general process concept of two-step CO2-splitting cycles is depicted in Figure 1. MO denotes a metal-based redox material, which is either reduced (MOred) or oxidized (MOox). The first step, referred to as thermal reduction (red), is the solar-driven endothermic dissociation of the metal oxide either to the elemental metal or the lowervalence metal oxide. The second step, the CO2 splitting (ox), is the exothermic oxidation of the reduced material to form CO. The overall reaction of the cycle is as follows:

(1)

(1)

Injecting water steam instead of (or with) carbon dioxide enables the production of hydrogen (or syngas).

While experimental campaigns such as HYDROSOL 2 proved the operability of this process on a solar tower [19,20], identifying that an efficient metal oxide is crucial for the commercialization of this technology. Many materials have been investigated such as various types of ferrites that suffer from sintering and slow kinetics [21-28] as well as cycles based on zinc or tin oxide requiring rapid quenching because of volatilization [29-32]. Recent material studies focused on ceria as the active material [33-36]. Non-stoichiometric ceria combines excellent reactivity due to high oxygen ion conductivity with good cyclability thanks to high-temperature stability. A test campaign at the High-Flux Solar Simulator of ETH Zurich confirmed the feasibility of a ceria-based cavity reactor [37,38] and innovative reactor designs are promising in regard to the overall process efficiency [39].

Figure 1. General schematic of the two-step thermochemical cycle for CO2 splitting. MO denotes a metal-based redox material.

Doping ceria with zirconia or lanthanides enhances the cycle performance [40-42].

In the present study, the impact of zirconia doping in ceria on the CO2-splitting performance was investigated by means of thermogravimetric analyses. Particularly, the Zr-content featuring the highest specific yield has been identified and analyzed in terms of reaction conditions and long-term stability.

2. Experimental Section

The materials were synthesized via the citrate nitrate auto combustion route similar to ones reported elsewhere [43]. Desired amounts of cerium (III) nitrate (99.9% purity, Merck) and zirconoium (IV) oxynitrate hexahydrate (99.99% purity, Sigma Aldrich) were dissolved in deionized water using a reaction vessel made of quartz. Citric acid (99% purity, Merck) also dissolved in deionized water was added to the nitrates in a molar ratio of 1:2 (cations:citric acid). Water evaporation at 95˚C on a heating plate under continuous stirring yielded a yellowcolored gel. Heating this gel to 200˚C for 20 minutes resulted in a swollen foam exhibiting a very low density. During slow heating to 500˚C, the auto combustion took place leaving a fine oxide powder in the reaction vessel. Subsequent calcination in the reaction vessel in a muffle furnace at 800˚C for 1h under air ensured the removal of remaining carbonaceous species. Further calcination at 1400˚C for 1 h in a Pt crucible completed the synthesis route. For each composition two batches were synthesized to guarantee reproducibility.

Phase analyses were performed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a computer-controlled diffractometer (D- 5000, Siemens, Germany) with CuKα radiation. As a result, all materials showed a cubic fluorite structure as observed for pure ceria with a small peak shift to high 2θ angle due to the lattice contraction caused by the smaller Zr4+ ions. Microstructures were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) Ultra 55 FEG (Carl Zeiss, Germany) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) system.

The performance of the synthesized materials was investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) with the aid of a thermo balance STA 449 F3 Jupiter (Netzsch, Germany). The powder was placed on an Al2O3 plate (13 mm in diameter covered with a Pt-foil). During reduction, the measuring cell was purged with Ar (5.0). Due to oxygen impurities of less than 2 ppm, the partial pressure was calculated to be approximately 5 × 10−6 bar. Comparison of maximum reducibilities obtained in calibration runs of pure ceria with literature values confirmed this presumed partial pressure [44]. The calibration runs comprised long reduction steps of more than 4 h at different temperatures providing equilibrium conditions. CO2 splitting was performed under a mixture of 6 vol.% CO2 (4.8) in Ar (5.0). The flow rate was set to 85 ml∙min−1 for all experiments. A mass spectrometer connected to the gas outlet valve of the TGA qualitatively confirmed the redox reaction, detecting O2 during reduction and CO during splitting.

The mass loss  during thermal reduction corresponds to the oxygen release; the mass gain

during thermal reduction corresponds to the oxygen release; the mass gain  during CO2 splitting to the oxygen uptake.

during CO2 splitting to the oxygen uptake.  and

and  were estimated based on the regulation EN ISO 11358. These values allow the calculation of the mole ratio of reduced/oxidized cerium atoms to the total amount of cerium atoms (redox extent: Xred and Xox in at.%

were estimated based on the regulation EN ISO 11358. These values allow the calculation of the mole ratio of reduced/oxidized cerium atoms to the total amount of cerium atoms (redox extent: Xred and Xox in at.%  and at.%

and at.% , respectively) and the specific O2 and CO yield (specific yield: nm(O2) and nm(CO) in mmol O2 and mmol CO per gram oxidized material, respectively).

, respectively) and the specific O2 and CO yield (specific yield: nm(O2) and nm(CO) in mmol O2 and mmol CO per gram oxidized material, respectively).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Thermo Balance

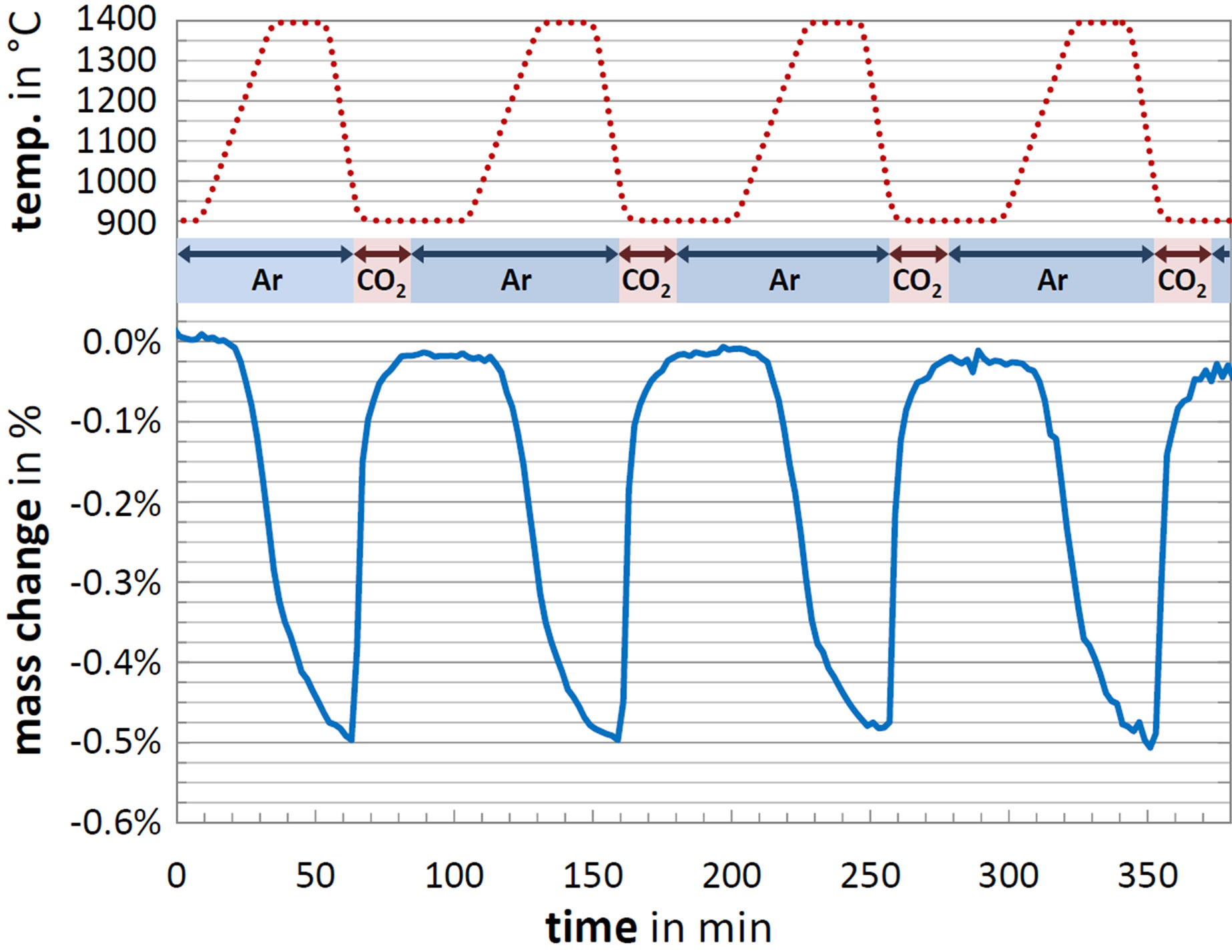

The reducibility and CO2-splitting ability of Ce1−xZrxO2 compositions with varying x in the range of 0 to 0.375 were assessed via successive cycling. The data of a typical TGA run is shown in Figure 2. After a pre-heating step to 1300˚C with subsequent cooling to 900˚C (not shown here), four similar cycles were performed consisting of a reduction step (heating to 1400˚C with 20 Kmin−1; isothermal for 20 minutes) and a splitting step (cooling to 900˚C with 50 Kmin−1; isothermal for 20 minutes under 6.3 vol.% CO2 in Ar and 20 minutes under pure Ar). Three to five individual samples per composition with masses of approximately 30 mg were subjected to cycling runs. Each of these sample runs were corrected with five independent blank runs that were conducted periodically during the test campaign. Therewith, we achieved reasonable standard uncertainties of the calcu-

Figure 2. TGA program (temperature and atmosphere) applied in experiments and corresponding mass change vs. time. Composition: Ce0.85Zr0.15O2.

lated redox ratios and specific yields.

The mass gain and loss alternately occur in the cyclic reaction along with the temperature variation as seen in Figure 2. During the heating process from 900˚C to 1400˚C, the reduction starts at about 1200˚C corresponding to a sharp mass loss. The reaction rate markedly increases with temperature. As the temperature plateau begins, the  curve exhibits an inflection point representing a gradual reaction deceleration. This behavior was also observed from other groups and attributed to the rate-limiting transition between the surface reaction and the bulk reaction [45]. At the end of the isothermal, the reduction is close to completion. Upon cooling to 900˚C, CO2 was injected into the measuring cell causing a sharp mass increase. The oxidation reaction is significantly faster than the reduction and does not slow down before

curve exhibits an inflection point representing a gradual reaction deceleration. This behavior was also observed from other groups and attributed to the rate-limiting transition between the surface reaction and the bulk reaction [45]. At the end of the isothermal, the reduction is close to completion. Upon cooling to 900˚C, CO2 was injected into the measuring cell causing a sharp mass increase. The oxidation reaction is significantly faster than the reduction and does not slow down before  is reached. After 20 minutes injecting CO2, the sample mass approximates its initial value equaling full reoxidation.

is reached. After 20 minutes injecting CO2, the sample mass approximates its initial value equaling full reoxidation.

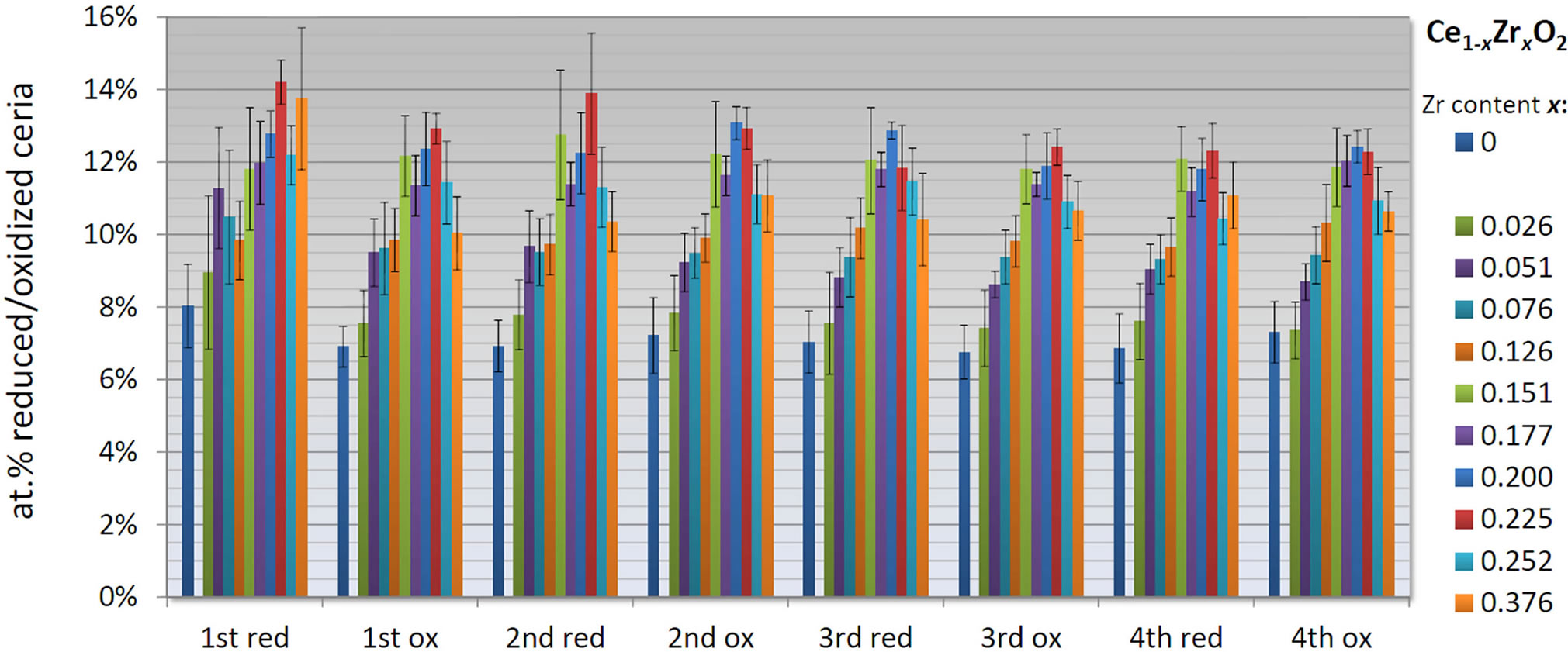

3.2. Splitting Performance Depending on the Zirconia Content x

Figure 3 summarizes the calculated redox extents Xred and Xox depending on the Zirconia content x, based on the obtained  and

and . For each cycle, the reduction extent approximately equals its following oxidation extent. Only the first oxidation seems incomplete. This might be due to difficulties to determine the actual starting point of the reduction, causing values of Xred of the first reduction that are slightly too high. The redox extents marginally decrease in the first two cycles until they stabilize in the last two cycles. For further discussion only the third and fourth cycles are taken into account due to high uncertainties of the first two cycles.

. For each cycle, the reduction extent approximately equals its following oxidation extent. Only the first oxidation seems incomplete. This might be due to difficulties to determine the actual starting point of the reduction, causing values of Xred of the first reduction that are slightly too high. The redox extents marginally decrease in the first two cycles until they stabilize in the last two cycles. For further discussion only the third and fourth cycles are taken into account due to high uncertainties of the first two cycles.

The redox extent augments with increasing Zr content from Xred/ox ≈ 7% observed for pure ceria to Xred/ox ≈ 12% for compositions in the range of 15% to 22.5% Zr content. These results are in good agreement with results found in the literature [45,46]. Further increasing the Zr content diminishes the reducibility of the material to Xred/ox ≈ 10%. Accordingly, the optimal Zr content concerning the redox extent is in the range of 0.15 ≤ x ≤ 0.225.

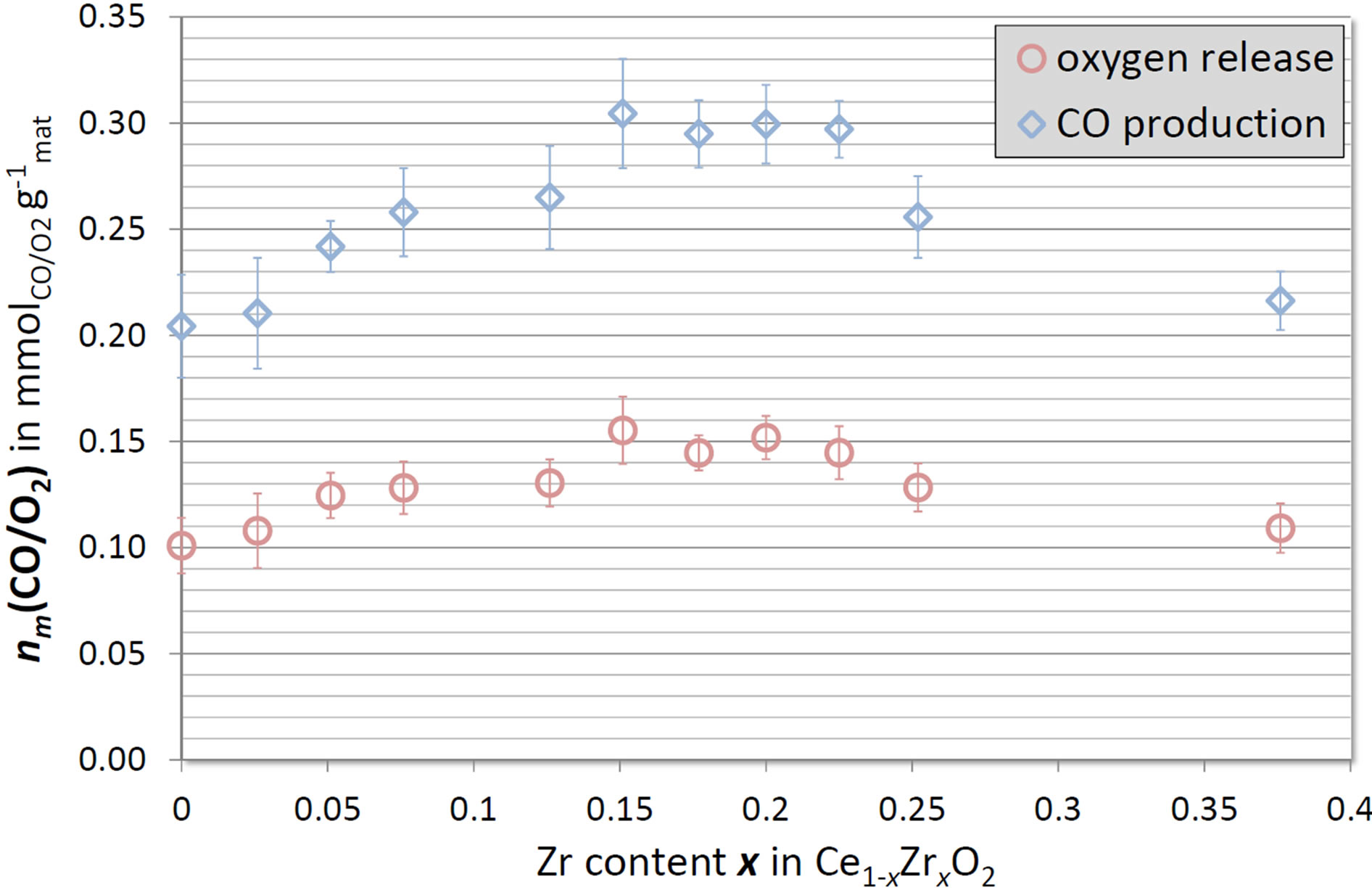

Specific yields are necessary to assess the performance of the material towards a technical realization of the process because they convey information important for the reactor design. The specific yields of O2 and CO averaged over the third and fourth cycles are depicted in Figure 4.

Increasing the Zr-content inherently influences the specific yields in two ways. On the one hand, the molar weight decreases due to the lower molar weight of zirconium compared to cerium. Hence, higher Zr-contents enhance the specific yields compared to the redox extents.

Figure 3. Redox extents Xred and Xox of Ce1−xZrxO2 compositions vs. each step (reduction conditions: 20 min at 1400˚C, 5.0 Ar atmosphere, oxidation condition: 20 min at 900˚C, 6.3 vol.% CO2).

Figure 4. Specific yields nm(O2) and nm(CO) calculated from TGA runs of Ce1−xZrxO2 with 0 ≤ x < 0.4 (average yields over cycle 3 - 4).

On the other hand, the load of active sites (cerium) and therewith the actual activity of the material decreases. Taking these opposed effects into account modifies the ranking based on the redox extents and determines the optimal Zr-content to be 15%. Ce0.85Zr0.15O2 releases 0.155 ± 0.016 mmol O2 per gram material during reduction and produces 0.305 ± 0.026 mmol CO per gram material, respectively. This represents an increase of approximately 50% with respect to pure ceria.

The results clearly indicate that the substitution of Ce4+ by isovalent Zr4+ enhances the reducibility, which agrees with earlier studies [40,46-48]. For some authors, the enhancement is attributed to modifications in the crystal structure. The reduction from Ce4+ to Ce3+ causes the lattice to expand, since Ce4+ exhibits a smaller ionic radius resulting in a stress that suppresses further reduction [49]. Introducing Zr4+ into the fluorite structure of ceria compensates for the expansion of the crystal lattice, since Zr4+ ions are smaller than Ce4+ and Ce3+ ions [46,50]. Theoretical calculations of CeO2-ZrO2 solid solutions showed that the introduction of 10% of zirconia substantially lowered the reduction energy of Ce4+ [51]. However, for higher Zr-contents the reduction energy remained approximately constant.

Recently, Kuhn et al. fitted a point defect model to TGA data indicating a decline in the reduction enthalpy with increasing Zr-content up to 20%, consistent with the findings in the present study [52]. Kuhn et al. also suggested that the smaller Zr4+ drives the formation of oxygen vacancies caused by the reduction of Ce4+ to Ce3+. This is due to the fact, that Zr4+ prefers a lower coordination with oxygen (e.g. Zr [7] in monoclinic ZrO2) in contrast to Ce [8].

3.3. Impact on the Reaction Conditions

The reaction conditions required to reduce ceria-based materials are one of the major barriers to technical success of the process. Particularly, the high temperature T and/or the low partial pressure of oxygen p(O2) cause a significant decrease on the process efficiency. Recently, Ermanoski et al. [39] exemplary estimated the process efficiency depending on the reduction extent δ of the following reaction:

(2)

(2)

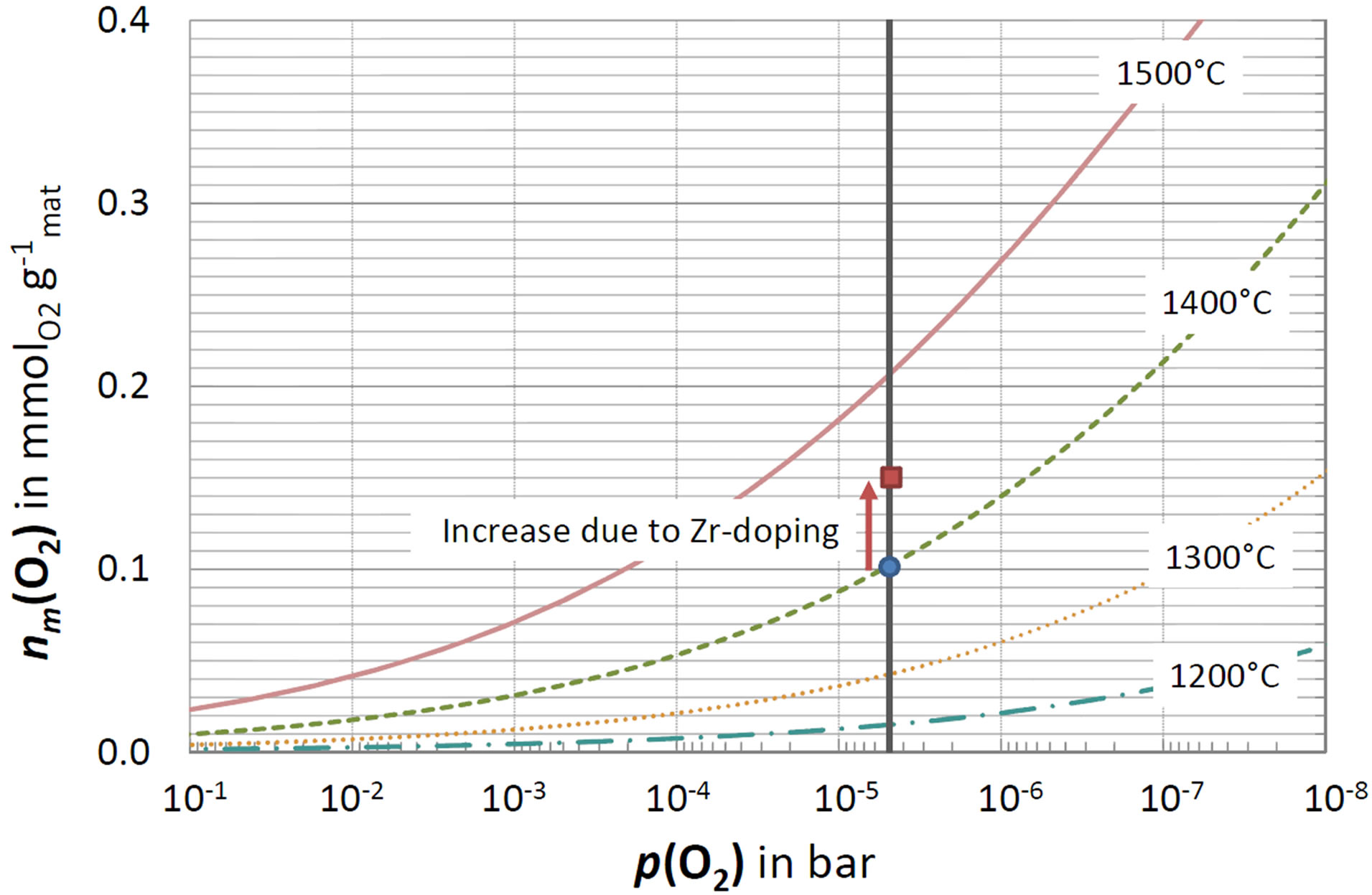

Thereby, they introduced a routine that fit thermogravimetric data of pure ceria for a wide range of temperatures and oxygen partial pressures p(O2) published by Panlener et al. [44]. Based on this routine, the specific yields nm(O2) depending on T and p(O2) of pure ceria are assessable and depicted in Figure 5.

At a reduction temperature of T = 1400˚C (green dashed line) and an oxygen partial pressure of p(O2) = 5 × 10−6 bar (vertical solid line), pure ceria releases approximately 0.1 mmol O2  (blue circle). In our experiments, ceria evolved 0.101 ± 0.010 mmol O2

(blue circle). In our experiments, ceria evolved 0.101 ± 0.010 mmol O2 , demonstrating agreement with the literature data. The most efficient composition Ce0.85Zr0.15O2, releases 0.156 ± 0.016 mmol O2 per gram material (red square). Pure ceria does not release this amount until a temperature of 1460˚C is reached or p(O2) is further decreased by one order of magnitude. In other words, Zr-doping saves 60 K or one order of magnitude of p(O2). Hence, Zr-doping significantly enhances the process efficiency.

, demonstrating agreement with the literature data. The most efficient composition Ce0.85Zr0.15O2, releases 0.156 ± 0.016 mmol O2 per gram material (red square). Pure ceria does not release this amount until a temperature of 1460˚C is reached or p(O2) is further decreased by one order of magnitude. In other words, Zr-doping saves 60 K or one order of magnitude of p(O2). Hence, Zr-doping significantly enhances the process efficiency.

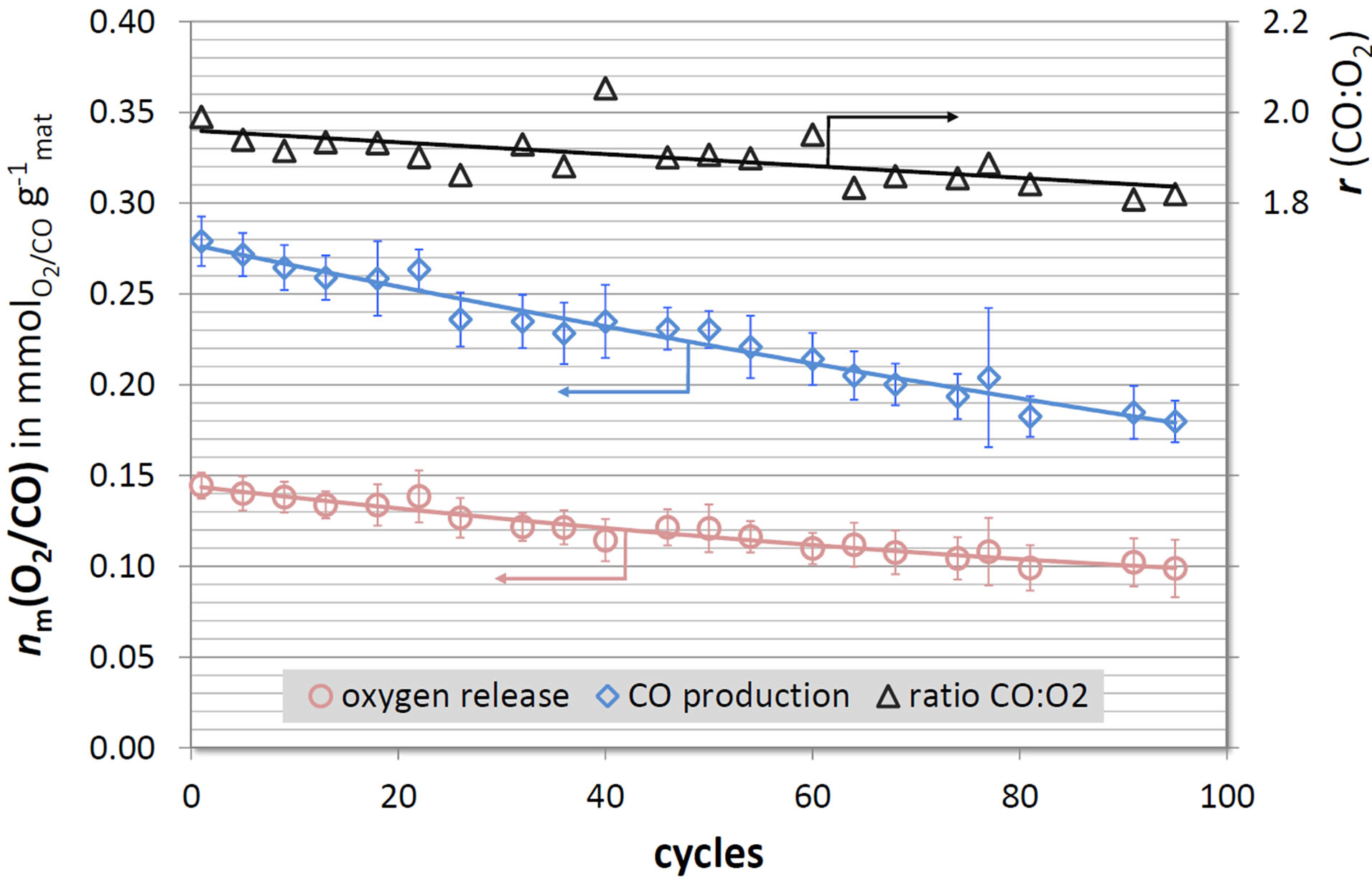

3.4. Durability of Zirconia-Doped Ceria

In the past, the long-term stability of the redox material was a major barrier to technical success of solar-driven fuel-production processes. Especially, ferrite-based materials suffered from long-term cycling at temperatures close to the melting point. Presumably, ceria-based materials exhibit an improved long-term behavior, because they feature much higher melting points (>2000˚C). To evaluate the long-term stability, several 16-cycle experiments were performed consecutively with the same powder sample of the most efficient composition (Ce0.85Zr0.15O2). The same temperature program was employed for all cycles: a reduction step (heating to 1400˚C with 20 Kmin−1; isothermal for 20 minutes) followed by a splitting step (cooling to 900˚C with 50 Kmin−1; isothermal for 20 minutes under 6.3 vol.% CO2 in Ar followed by 20 minutes under pure Ar). The specific yields nm(O2) and nm(CO) vs. the cycle number are depicted in Figure 6 as well as the corresponding ratio r of CO:O2 release (reduction with its following oxidation). Due to the stoichiometry of the reaction, r should equal two (see Equation 1).

The yields of the sample slightly but continuously decrease with increasing cycle number. After 100 cycles,

Figure 5. The specific oxygen yield nm(O2) versus the partial pressure of oxygen p(O2). The dashed lines were calculated based on a fitting routine published by Ermanoski et al. [39] who fitted data of Panlener et al. [44]. The vertical solid line marks p(O2) = 5 × 0−6 bar, which was achieved in the thermo balance. The blue circle represents the result obtained at 1400˚C by TGA for pure ceria; the red square for Ce0.85Zr0.15O2.

Figure 6. Specific yields nm(O2) and nm(CO) calculated from long-term TGA runs of Ce0.85Zr0.15O2 (data averaged over 4 cycles). Ratio r of CO:O2 release (stoichiometrical: r = 2).

the material only evolves 0.100 ± 0.014 mmol O2 and produces 0.195 ± 0.016 mmol CO per gram and cycle, respectively, corresponding to a decrease of more than 30% of the initial value (first cycle). The ratio r equals two only for the first cycles and continuously declines with increasing cycle number to r ≈ 1.8. Ratios r smaller than 2 indicate incomplete reoxidation of the material. Hence, with increasing cycle number, the twenty minutes under CO2 did not suffice to ensure complete reoxidation. In turn, only a smaller amount of cerium atoms are reduced in the following cycle.

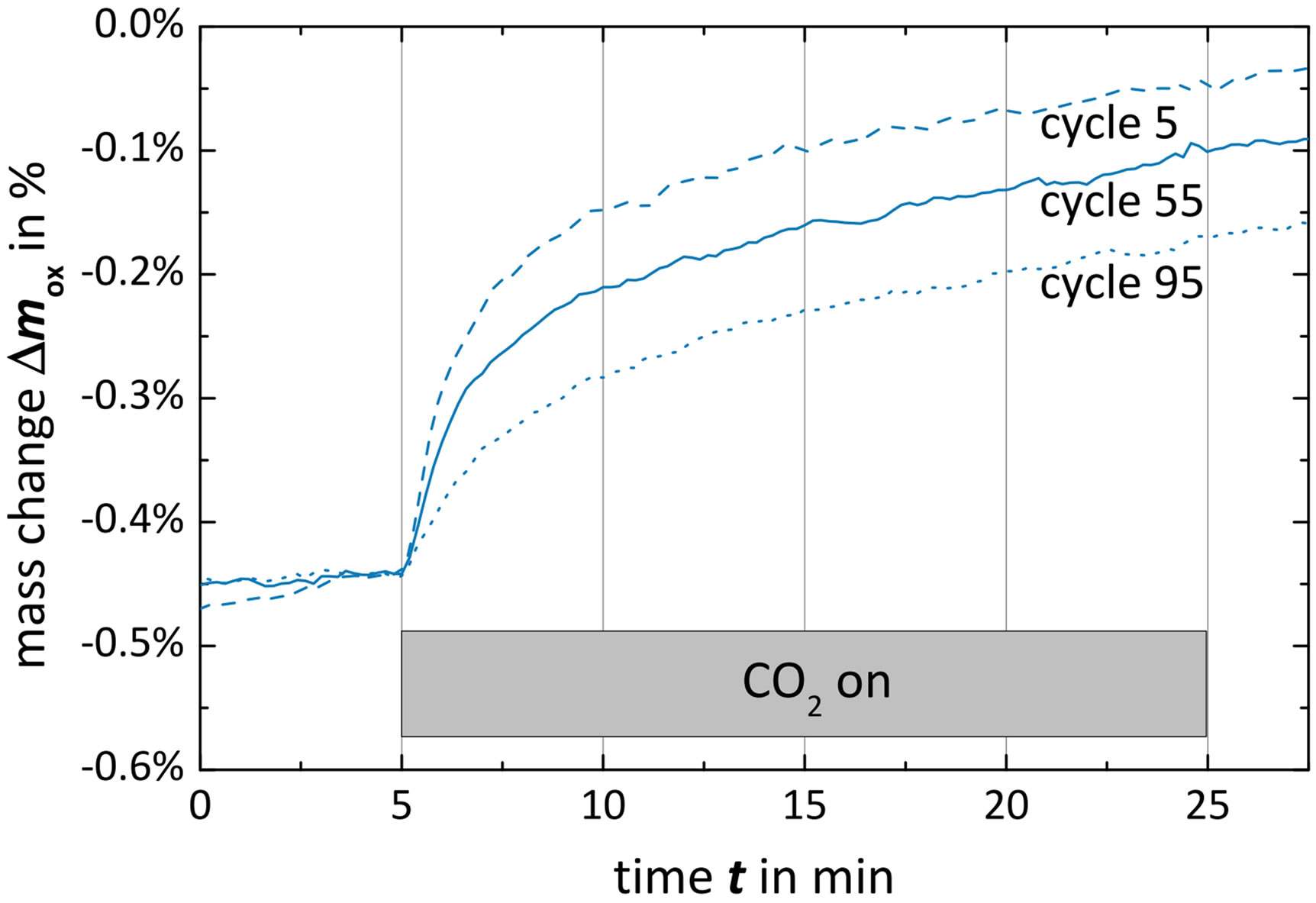

Figure 7 shows the  data of three oxidation steps (beginning, middle and end of long-term cycling), as well as the impact of long-term cycling on the microstructure. As CO2 is injected (minute 5), the oxidation immediately starts corresponding to a mass gain. In the beginning of all three oxidation steps, the mass change exhibits an almost linear increase that smoothly segues into a logarithmical increase. The lower the cycle number, the longer and steeper is the linear regime. The logarithmical slope, however, is independent of the cycle number and is approximately constant yielding to decreasing oxidation extents with increasing cycle number. As mentioned before, the linear regime is associated with the surface reaction in contrast to the following bulk reaction [45]. Hence, difference in the linear regimes should correspond to changes of the specific surface.

data of three oxidation steps (beginning, middle and end of long-term cycling), as well as the impact of long-term cycling on the microstructure. As CO2 is injected (minute 5), the oxidation immediately starts corresponding to a mass gain. In the beginning of all three oxidation steps, the mass change exhibits an almost linear increase that smoothly segues into a logarithmical increase. The lower the cycle number, the longer and steeper is the linear regime. The logarithmical slope, however, is independent of the cycle number and is approximately constant yielding to decreasing oxidation extents with increasing cycle number. As mentioned before, the linear regime is associated with the surface reaction in contrast to the following bulk reaction [45]. Hence, difference in the linear regimes should correspond to changes of the specific surface.

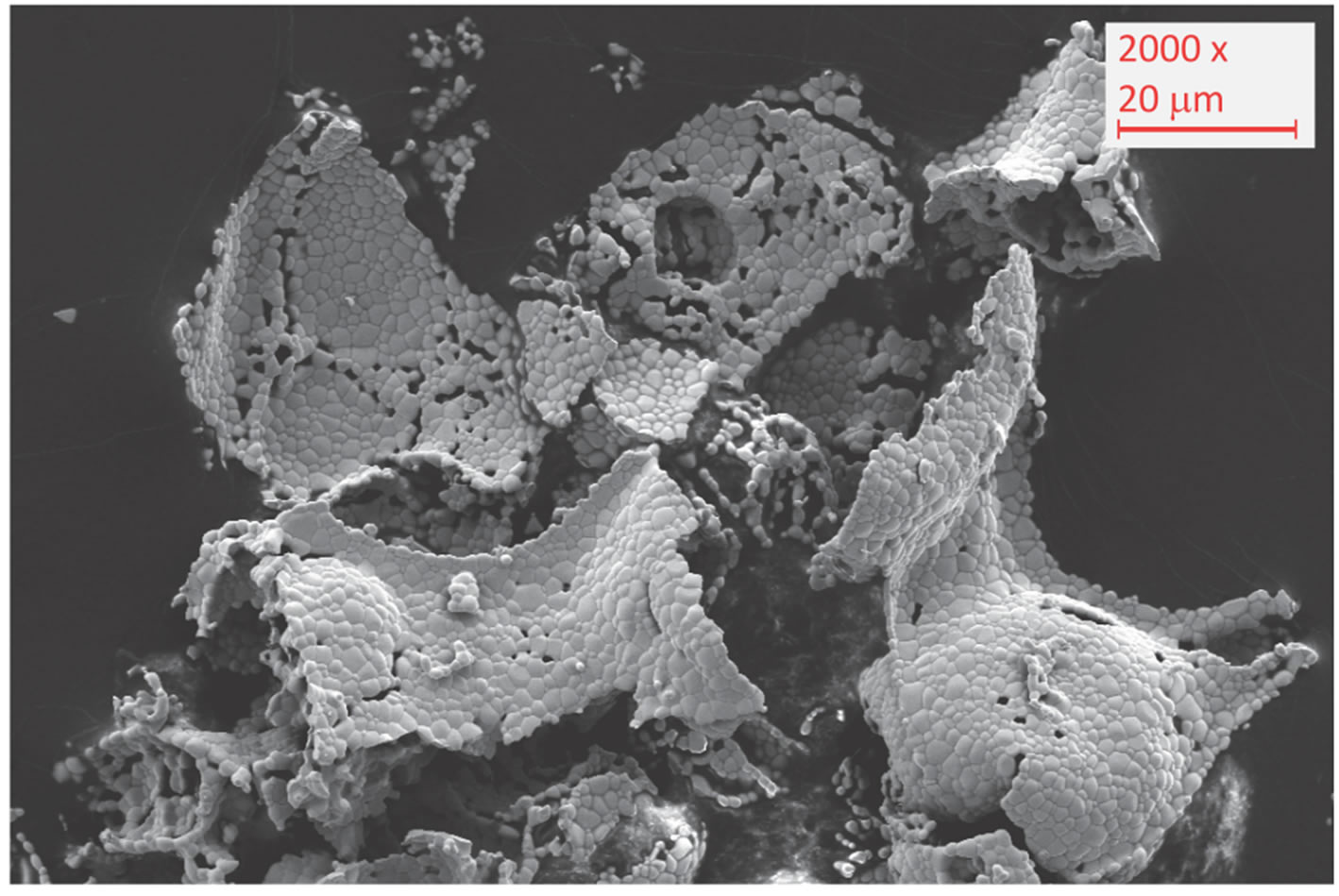

SEM imaging of the material before and after longterm cycling reveals that particle and grain sizes of the material significantly increase. The grains grow from sizes less than 1 μm after four cycles to sizes of 1 - 3 μm after one hundred cycles and agglomerate to particles of more than 50 μm. This sintering takes place gradually during long-term cycling of the material. Accordingly, the specific surface continuously decreases causing deceleration of the oxidation. Since the reduction kinetics (not shown here) feature no changes with increasing cycle number, we conclude that in the case of powder ma-

(a)

(a) (b)

(b) (c)

(c)

Figure 7. Long-term test campaign of Ce0.85Zr0.15O2: (a) course of Dmox during cycles; (c) SEM image after one hundred cycles.

terials the microstructure rather influences the kinetics of the splitting step than the reduction kinetics.

Further evidence for the crucial dependency of the oxidation on the specific surface rather than on the diffusion can be derived from literature data [53,54]. Oxygen diffusivities DO at a temperature of 900˚C of at least 2 ×10−9 m2s−1 are reported. According to Einstein’s relation, the characteristic diffusion length scale ld is as follows:

(3)

(3)

t denotes the time for the investigated process. Assuming t = 600 s, which is half of the time of the oxidation step, the diffusion length scale ld is more than 1.5 mm. Since only particle sizes of approximately 50 μm are observed, the oxygen diffusion is unlikely to be ratelimiting.

When cycled at temperatures of 1400˚C, the sintering of ceria-based materials cannot be entirely prevented. Hence, the observed dependency of the oxidation kinetics on the specific surface emphasizes the importance of adjusting the reduction and oxidation durations during long-term operation. Particularly, this is important when powder materials are employed. One way to improve the kinetics was discussed by Le Gal et al. [41]. They observed an enhanced reactivity by doping ceria-zirconia solid solutions with small amounts of trivalent lanthanides. The doping caused a less pronounced sintering activity.

4. Conclusions

The production of solar fuels by means of thermochemical redox cycles that split H2O and CO2 and produce synthesis gas has been considered to enable a secure, clean and sustainable energy supply. The active ceriabased materials have been proposed and investigated regarding the impact of Zr-doping on the splitting performance. In this study, Ce1−xZrxO2 oxides were synthesized via the citrate nitrate auto combustion route at different Ce:Zr molar ratios (0 ≤ x < 0.4). In order to evaluate their applicability for solar fuel production, they were subjected to thermogravimetric experiments, simulating CO2-splitting cycles. The Zr-content featuring the highest specific yield was identified and analyzed in terms of reaction conditions and long-term stability.

The results indicate that a certain Zr-content (0.15 ≤ x ≤ 0.225) enhances the reducibility and therefore the splitting performance. Increasing the Zr-content to x = 0.15 improved the specific CO2-splitting performance by 50% compared to pure ceria. Further increasing the Zr-content to x = 0.38 diminished the specific yields to values of pure ceria. This finding agrees with theoretical studies attributing the improvements to lattice modification caused by the introduction of Zr4+. Compared to pure ceria, the most efficient composition Ce0.85Zr0.15O2 enhances the required reaction conditions by a temperature of 60 K or one order of magnitude of the partial pressure of oxygen p(O2). Long-term cycling of one hundred cycles was performed revealing declining oxidation kinetics.

The future interest is to understand how the microstructure influences the splitting as well as the reduction performance. Particularly, the splitting and reduction kinetics will be investigated in upcoming studies. Doping ceria-zirconia solutions with trivalent lanthanides may improve long-term stability, further enhancing the overall process efficiency.

5. Acknowledgements

Part of the work was co-funded by the Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers.

REFERENCES

- F. Fischer and H. Tropsch, “Über Die Direkte Synthese von Erdöl-Kohlenwasserstoffen bei Gewöhnlichem Druck. (Erste Mitteilung),” Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series), Vol. 59, No. 4, 1926, pp. 830-831. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cber.19260590442

- A. A. Adesina, “Hydrocarbon Synthesis via Fischer-Tropsch Reaction: Travails and Triumphs,” Applied Catalysis A: General, Vol. 138, No. 2, 1996, pp. 345-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0926-860X(95)00307-X

- M. Dry, “The Fischer—Tropsch Process: 1950-2000,” Catalysis Today, Vol. 71, No. 3-4, 2002, pp. 227-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(01)00453-9

- J. Mantzaras, “Catalytic Combustion of Syngas,” Combustion Science and Technology, Vol. 180, No. 6, 2008, pp. 1137-1168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00102200801963342

- J. R. Rostrup-Nielsen, “Syngas in Perspective,” Catalysis Today, Vol. 71, No. 3-4, 2002, pp. 243-247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(01)00454-0

- C. Koroneos, A. Dompros, G. Roumbas and N. Moussiopoulos, “Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrogen Fuel Production Processes,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 29, No. 14, 2004, pp. 1443-1450. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2004.01.016

- K. Li, H. Wang, Y. Wei and D. Yan, “Syngas Production from Methane and Air via a Redox Process Using Ce-Fe Mixed Oxides as Oxygen Carriers,” Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, Vol. 97, No. 3-4, 2010, pp. 361-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.04.018

- C. Perkins and A. W. Weimer, “Solar-Thermal Production of Renewable Hydrogen,” AIChE Journal, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2009, pp. 286-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/aic.11810

- G. Centi and S. Perathoner, “Towards Solar Fuels from Water and CO2,” ChemSusChem, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2010, pp. 195-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cssc.200900289

- N. S. Lewis and D. G. Nocera, “Powering the Planet: Chemical Challenges in Solar Energy Utilization,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 103, No. 43, 2006, pp. 15729-15735.

- N. Itoh, M. A. Sanchez, W.-C. Xu, K. Haraya and M. Hongo, “Application of a Membrane Reactor System to Thermal Decomposition of CO2,” Application of Membrane Science, Vol. 77, No. 2-3, 1993, pp. 245-253.

- R. J. Price, D. A. Morse, S. L. Hardy, T. H. Fletcher, S. C. Hill and R. J. Jensen, “Modeling the Direct Solar Conversion of CO2 to CO and O2,” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, Vol. 43, No. 10, 2004, pp. 2446-2453. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ie030745o

- A. Kogan, “Direct Solar Thermal Splitting of Water and On-Site Separation of the Products. III. Improvement of Reactor Efficiency by Steam Entrainment,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 25, No. 8, 2000, pp. 739-745. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0360-3199(99)00102-0

- T. Nakamura, “Hydrogen Production from Water Utilizing Solar Heat at High Temperatures,” Solar Energy, Vol. 19, No. 5, 1977, pp. 467-475. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0038-092X(77)90102-5

- Y. Tamaura, A. Steinfeld, P. Kuhn and K. Ehrensberger, “Production of Solar Hydrogen by a Novel, 2-Step, Water-Splitting Thermochemical Cycle,” Energy, Vol. 20, No. 4, 1995, pp. 325-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0360-5442(94)00099-O

- A. Steinfeld, P. Kuhn, A. Reller, R. Palumbo, J. Murray and Y. Tamaura, “Solar-Processed Metals as Clean Energy Carriers and Water-Splitters,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 23, No. 9, 1998, pp. 767-774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0360-3199(97)00135-3

- T. Kodama and N. Gokon, “Thermochemical Cycles for High-Temperature Solar Hydrogen Production,” Chemical Reviews, Vol. 107, No. 10, 2007, pp. 4048-4077. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/cr050188a

- E. N. Coker, M. A. Rodriguez, A. Ambrosini, R. R. Stumpf, E. B. Stechel, C. Wolverton, et al., “Sandia Final Report: Fundamental Materials Issues for Thermochemical H2O and CO2 Splitting Final Report,” 2008.

- M. Roeb, J. P. Säck, P. Rietbrock, C. Prahl, H. Schreiber, M. Neises, et al., “Test Operation of a 100 kW Pilot Plant for Solar Hydrogen Production from Water on a Solar Tower,” Solar Energy, Vol. 85, No. 4, 2011, pp. 634-644. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2010.04.014

- J.-P. Säck, M. Roeb, C. Sattler, R. Pitz-Paal and A. Heinzel, “Development of a System Model for a Hydrogen Production Process on a Solar Tower,” Solar Energy, Vol. 86, No. 1, 2012, pp. 99-111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2011.09.010

- Y. Tamaura, R. Uehara, N. Hasegawa, H. Kaneko and H. Aoki, “Study on Solid-State Chemistry of the ZnO/Fe3O4/ H2O System for H2 Production at 973 - 1073 K,” Solid State Ionics, Vol. 172, No. 4, 2004, pp. 121-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ssi.2004.02.041

- C. Agrafiotis, M. Roeb, A. G. Konstandopoulos, L. Nalbandian, V. T. Zaspalis, C. Sattler, et al., “Solar Water Splitting for Hydrogen Production with Monolothic Reactors,” Solar Energy, Vol. 79, 2005, pp. 409-421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2005.02.026

- M. Roeb, C. Sattler, R. Klüser, N. Monnerie, L. D. Oliveria, A. G. Konstandopoulos, et al., “Solar Hydrogen Production by a Two-Step Cycle Based on Mixed Iron Oxides,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, Vol. 128, No. 2, 2006, pp. 125-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1115/1.2183804

- P. Charvin, S. Abanades, G. Flamant, F. Lemort, “TwoStep Water Splitting Thermochemical Cycle Based on Iron Oxide Redox Pair for Solar Hydrogen Production,” Energy, Vol. 32, No. 7, 2007, pp. 1124-1133.

- H. Ishihara, H. Kaneko, N. Hasegawa and Y. Tamaura, Two-Step Water-Splitting at 1273-1623 K Using YttriaStabilized Zirconia-Iron Oxide Solid Solution via CoPrecipitation and Solid-State Reaction,” Energy, Vol. 33, No. 12, 2008, pp. 1788-1793. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2008.08.005

- M. Neises, M. Roeb, M. Schmücker, C. Sattler and R. Pitz-Paal, “Kinetic Investigations of the Hydrogen Production Step of a Thermochmical Cycle Using Mixed Iron Oxides Coated on Ceramic Substrates,” International Journal of Energy Research, Vol. 34, No. 8, 2009, pp. 651-661.

- L. J. Ma, L. S. Chen and S. Y. Chen, “Studies on Redox H2-CO2 Cycle on CoCrxFe2-xO4,” Solid State Sciences, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2009, pp. 176-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2008.05.008

- N. Gokon, T. Kodama, N. Imaizumi, J. Umeda and T. Seo, “Ferrite/Zirconia-Coated Foam Device Prepared by Spin Coating for Solar Demonstration of Thermochemical Water-Splitting,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2011, pp. 2014-2028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.11.034

- A. Steinfeld, “Solar Hydrogen Production via a Two-Step Water-Splitting Thermochemical Cycle Based on Zn/ZnO Redox Reactions,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 27, No. 6, 2002, pp. 611-619. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00177-X

- A. Stamatiou, P. G. Loutzenhiser and A. Steinfeld, “Solar Syngas Production via H2O/CO2-Splitting Thermochemical Cycles with Zn/ZnO and FeO/Fe3O4 Redox Reactions,” Chemistry of Materials, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2010, pp. 851-859. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/cm9016529

- P. G. Loutzenhiser, A. Meier and A. Steinfeld, “Review of the Two-Step H2O/CO2-Splitting Solar Thermochemical Cycle Based on Zn/ZnO Redox Reactions,” Materials, Vol. 3, No. 11, 2010, pp. 4922-4938. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ma3114922

- S. Abanades, P. Charvin, F. Lemort and G. Flamant, “Novel Two-Step SnO2/SnO Water-Splitting Cycle for Solar Thermochemical Production of Hydrogen,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 33, No. 21, 2008, pp. 6021-6030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.05.042

- S. Abanades and G. Flamant, “Thermochemical Hydrogen Production from a Two-Step Solar-Driven WaterSplitting Cycle Based on Cerium Oxides,” Solar Energy, Vol. 80, No. 12, 2006, pp. 1611-1623. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2005.12.005

- W. C. Chueh, C. Falter, M. Abbott, D. Scipio, P. Furler, S. M. Haile, et al., “High-Flux Solar-Driven Thermochemical Dissociation of CO2 and H2O Using Nonstoichiometric Ceria,” Science, Vol. 330, No. 6012, 2010, pp. 1797- 1801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1197834

- W. C. Chueh and S. M. Haile, “A Thermochemical Study of Ceria: Exploiting an Old Material for New Modes of Energy Conversion and CO2 Mitigation,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, Vol. 368, No. 1923, 2010, pp. 3269-3294.

- J. R. Scheffe and A. Steinfeld, “Thermodynamic Analysis of Cerium-Based Oxides for Solar Thermochemical Fuel Production,” Energy & Fuels, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2012, pp. 1928-1936. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ef201875v

- P. Furler, J. Scheffe, M. Gorbar, L. Moes, U. Vogt and A. Steinfeld, “Solar Thermochemical CO2 Splitting Utilizing a Reticulated Porous Ceria Redox System,” Energy & Fuels, Vol. 26, No. 11, 2012, pp. 7051-7059.

- P. Furler, J. R. Scheffe and A. Steinfeld, “Syngas Production by Simultaneous Splitting of H2O and CO2 via Ceria Redox Reactions in a High-Temperature Solar Reactor,” Energy & Environmental Science, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2012, pp. 6098-6103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c1ee02620h

- I. Ermanoski, N. P. Siegel and E. B. Stechel, “A New Reactor Concept for Efficient Solar-Thermochemical Fuel Production,” Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, Vol. 135, No. 3, 2013, Article ID: 031002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1115/1.4023356

- S. Abanades, A. Legal, A. Cordier, G. Peraudeau, G. Flamant and A. Julbe, “Investigation of Reactive CeriumBased Oxides for H2 Production by Thermochemical TwoStep Water-Splitting,” Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 45, No. 15, 2010, pp. 4163-4173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10853-010-4506-4

- A. Le Gal and S. Abanades, “Dopant Incorporation in Ceria for Enhanced Water-Splitting Activity during Solar Thermochemical Hydrogen Generation,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, Vol. 116, No. 25, 2012, pp. 13516- 13523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jp302146c

- Q.-L. Meng, C.-I. Lee, T. Ishihara, H. Kaneko and Y. Tamaura, “Reactivity of CeO2-Based Ceramics for Solar Hydrogen Production via a Two-Step Water-Splitting Cycle with Concentrated Solar Energy,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 36, No. 21, 2011, pp. 13435- 13441. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.07.089

- A. Banerjee and S. Bose, “Free-Standing Lead Zirconate Titanate Nanoparticles: Low-Temperature Synthesis and Densification,” Chemistry of Materials, Vol. 16, No. 26, 2004, pp. 5610-5615. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/cm0490423

- R. J. Panlener, R. N. Blumenthal, J. E. Garnier, “A Thermodynamic Study of Nonstoichiometric Cerium Dioxide,” Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, Vol. 36, No. 11, 1975, pp. 1213-1222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-3697(75)90192-4

- A. Le Gal and S. Abanades, “Catalytic Investigation of Ceria-Zirconia Solid Solutions for Solar Hydrogen Production,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol. 36, No. 8, 2011, pp. 4739-4748. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.01.078

- H. Kaneko, S. Taku and Y. Tamaura, “Reduction Reactivity of CeO2-ZrO2 Oxide under High O2 Partial Pressure in Two-Step Water Splitting Process,” Solar Energy, Vol. 85, No. 9, 2011, pp. 2321-2330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2011.06.019

- R. Di Monte and J. Kašpar, “Heterogeneous Environmental Catalysis—A Gentle Art: CeO2-ZrO2 Mixed Oxides as a Case History,” Catalysis Today, Vol. 100, No. 1-2, 2005, pp. 27-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2004.11.005

- G. Zhou, P. R. Shah, T. Kim, P. Fornasiero and R. J. Gorte, “Oxidation Entropies and Enthalpies of Ceria-Zirconia Solid Solutions,” Catalysis Today, Vol. 123, No. 1-4, 2007, pp. 86-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2007.01.013

- R. D. Shannon, “Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides,” Acta Crystallographica Section A, Vol. 32, No. 5, 1976, pp. 751-767. http://dx.doi.org/10.1107/S0567739476001551

- S. Lemaux, A. Bensaddik, A. M. J. van der Eerden, J. H. Bitter and D. C. Koningsberger, “Understanding of Enhanced Oxygen Storage Capacity in Ce0.5Zr0.5O2: The Presence of an Anharmonic Pair Distribution Function in the ZrO2 Subshell as Analyzed by XAFS Spectroscopy,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, Vol. 105, No. 21, 2001, pp. 4810-4815. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jp003111t

- G. Balducci, J. Kašpar, P. Fornasiero, M. Graziani, M. S. Islam and J. D. Gale, “Computer Simulation Studies of Bulk Reduction and Oxygen Migration in CeO2-ZrO2 Solid Solutions,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, Vol. 101, No. 10, 1997, pp. 1750-1753. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jp962530g

- M. Kuhn, S. R. Bishop, J. L. M. Rupp and H. L. Tuller, “Structural Characterization and Oxygen Nonstoichiometry of Ceria-Zirconia (Ce1−xZrxO2−δ) Solid Solutions,” Acta Materialia, Vol. 61, No. 11, 2013, pp. 4277-4288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2013.04.001

- F. Giordano, A. Trovarelli, C. de Leitenburg, G. Dolcetti and M. Giona, “Some Insight into the Effects of Oxygen Diffusion in the Reduction Kinetics of Ceria,” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, Vol. 40, No. 22, 2001, pp. 4828-4835. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ie010105q

- G. Chiodelli, G. Flor and M. Scagliotti, “Electrical Properties of the ZrO2-CeO2 System,” Solid State Ionics, Vol. 91, No. 1-2, 1996, pp. 109-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2738(96)00382-7

NOTES

*Corresponding author.