Natural Resources

Vol.05 No.13(2014), Article ID:51014,18 pages

10.4236/nr.2014.513072

Probabilistic Model for Wind Speed Variability Encountered by a Vessel

1Mathematical Sciences, Chalmers University of Technology, Göteborg, Sweden

2Department of Shipping and Marine Technology, Chalmers University of Technology, Göteborg, Sweden

Email: rychlik@chalmers.se, wengang.mao@chalmers.se

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 6 August 2014; revised 12 September 2014; accepted 2 October 2014

ABSTRACT

As a result of social awareness of air emission due to the use of fossil fuels, the utilization of the natural wind power resources becomes an important option to avoid the dependence on fossil resources in industrial activities. For example, the maritime industry, which is responsible for more than 90% of the world trade transport, has already started to look for solutions to use wind power as auxiliary propulsion for ships. The practical installation of the wind facilities often requires large amount of investment, while uncertainties for the corresponding energy gains are large. Therefore a reliable model to describe the variability of wind speeds is needed to estimate the expected available wind power, coefficient of the variation of the power and other statistics of interest, e.g. expected length of the wind conditions favorable for the wind-energy harvesting. In this paper, wind speeds are modeled by means of a spatio-temporal transformed Gaussian field. Its dependence structure is localized by introduction of time and space dependent parameters in the field. The model has the advantage of having a relatively small number of parameters. These parameters have natural physical interpretation and are statistically fitted to represent variability of observed wind speeds in ERA Interim reanalysis data set.

Keywords:

Wind Speeds, Wind-Energy, Spatio-Temporal Model, Gaussian Fields

1. Introduction

In the literature typically cumulative distribution function (CDF) of wind speed W, say, is understood as the long-term CDF of the wind speeds at some location or region. The distribution can be interpreted as variability of W at a randomly taken time during a year. Weibull distribution gives often a good fit. Limiting time span to, for example, January month affects the W CDF simply because, as it is the case for many geophysical quantities, the variability of W depends on seasons. To avoid ambiguity when discussing the distribution of W, time span and region over which the observations of W are gathered need to be clearly specified. By shrinking the time span to a single moment t and geographical region to a location p, one obtains (in the limit) the distribution of . This is used as the distribution of W in this paper. Obviously the long-term CDF can be retrieved from the “local”

. This is used as the distribution of W in this paper. Obviously the long-term CDF can be retrieved from the “local”

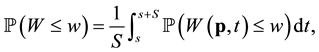

distributions by means of an average of the local distributions, viz for a fixed location p

distributions by means of an average of the local distributions, viz for a fixed location p

(1)

(1)

where S can be a month, a season or a year. Similarly the long-term CDF over a region A, say, is proportional to .

.

In order to identify the distributions at all positions p and times t, vast amount of data are needed. Here the reconstruction of W from numerical ocean-atmosphere models based on large-scale meteorological data, called also reanalysis, is utilized to fit a model. The reanalysis does not represent actual measurements of quantities but extrapolations to the grid locations based on simulations from complex dynamical models. It is defined on regular grids in time and space, and hence convenient to use. In this paper, the ERA Interim data [1] produced by European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts is used to fit the model. However the model can also be fitted to other data sets, e.g. to satellites wind measurements which has also good spatial coverage, see [2] .

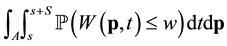

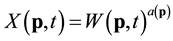

Modeling spatial and temporal dependence of wind speed is a very complex problem. Models proposed in the literature are reviewed in [3] . Here we propose to use the transformed Gaussian model, which assumes that there exists a deterministic function , possibly dependent on location p, such that

, possibly dependent on location p, such that

is Gaussian. The

is Gaussian. The

field is defined by the mean

field is defined by the mean

and covariance structure

and covariance structure

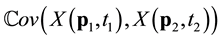

. Obviously for a given transformation G and many years of hind-cast, one could estimate the covariance for any pair

. Obviously for a given transformation G and many years of hind-cast, one could estimate the covariance for any pair ,

,

, see, e.g. [4] [5] . However such an approach is limited to relatively small grids in space. Employing the empirical covariances in time and space would result in huge matrices, which limit the applicability of such empirical approach. Consequently, a simple parametric model that catches only some aspects of the wind speed variability, important for a particular application, is of practical interest. The minimal requirements on the model are that it should provide a correct estimates of long-term distributions of the wind speeds, accurate predictions of average durations of the extreme winds conditions and reliable estimates of CDFs of top speeds during storms encountered by a vessel. In order to demonstrate the capability of the proposed model for such minimal requirements, this paper is organized as follows:

, see, e.g. [4] [5] . However such an approach is limited to relatively small grids in space. Employing the empirical covariances in time and space would result in huge matrices, which limit the applicability of such empirical approach. Consequently, a simple parametric model that catches only some aspects of the wind speed variability, important for a particular application, is of practical interest. The minimal requirements on the model are that it should provide a correct estimates of long-term distributions of the wind speeds, accurate predictions of average durations of the extreme winds conditions and reliable estimates of CDFs of top speeds during storms encountered by a vessel. In order to demonstrate the capability of the proposed model for such minimal requirements, this paper is organized as follows:

In Section 2, a general construction of non-stationary model for wind speed variability in time and space is presented. Section 3 presents probabilistic model for the velocity of storms movements. Then statistical properties of some storms characteristics are described in Section 4. The physical interpretations of the introduced parameters are also given in this section and in Appendix 1. In Section 5, on board measured wind speeds are used to validate the proposed model, where the long term CDFs of encountered wind speeds and persistence statistics are used. Total forty routes are used, see Figure 1. The time when routes were sailed are well spread over a year. Finally in Section 6, means to simulate the encountered wind speeds are briefly reviewed. Paper closes with three appendixes containing somewhat more technical matters.

2. Transformed Gaussian Model and Long-Term CDFs

In this section we shall introduce the transformed Gaussian model for the variability of wind speeds. In particular the transformation G making the transformed wind speed data

normally distributed will be presented. Seasonal model for the mean and variance of X is given and assumed normality of X validated.

normally distributed will be presented. Seasonal model for the mean and variance of X is given and assumed normality of X validated.

The wind speed

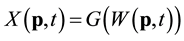

is the ten minutes average of the wind speed measured at position p, defined in degrees of longitude and latitude, while t is the time of the year. We will use the transformation

is the ten minutes average of the wind speed measured at position p, defined in degrees of longitude and latitude, while t is the time of the year. We will use the transformation , where a is a fixed constant that depends on the location p, viz

, where a is a fixed constant that depends on the location p, viz

(2)

(2)

The parameter a is nonnegative with convention that the case

corresponds to the logarithm. We assume that

corresponds to the logarithm. We assume that

Mean and variance of

Figure 1. The considered routes in the validation process.

time. The temporal variability of mean and variance is approximated by seasonal components with trends defined as follows

Here t has units years. This type of model has been used in the literature, see e.g. classical paper [6] .

Remark 1 For a fixed position p, the parameters a and mi in Equation (3) are fitted simultaneously in such a way that the distance between yearly long-term empirical CDF of

More precisely for a wind data at fixed position p and parameter

A table of a and mi values as function of the location p is created. As additional parameters of the model will be estimated new columns with parameters estimates will be added to the table. For example, having estimated a and mi the variance

Validation of Gaussianity of

Ten years of data

Usefulness of the proposed model relies on the accuracy of the approximation of

In the right plots of Figure 4, the standard deviation

Figure 2. Values of parameter a in the transformation Equation (2).

Figure 3. Left: Ten years of wind speeds W (t) with t limited to February at the four locations. (−20, 60), (−10, 40), (−40, 50), (−20, 45) plotted on normal probability paper. Right: Transformed wind speeds X (t) limited to February at the four locations plotted on normal probability paper. The values of parameter a in transformation Equation (2) are a = 0.850, 0.675, 0.875, 0.875, respectively.

instead. The values of the median for February and August are presented in two left plots of Figure 4. As expected, wind speeds are higher in winter than in summer.

Finally we check whether the regressions Equations (3) and (4) used to model seasonal variability of m and

where

Figure 4. Left top―Median wind speed m [m/s], defined in Equation (5), in February; Left bottom―Median wind speed in August; Right top―Standard deviation of X, computed by means of Equation (4) in February; Right bottom―The standard deviation in August.

Figure 5. Comparisons of estimates of the long-term probability

3. Velocity of a Wind Storm

A storm occurring at time t is a region where

Following [8] the velocities in the direction θ and θ − 90˚ are given by

where Wt is the time derivative of the wind speed,

The general assumption of this paper is that parameter a does not depend on time and changes much slower in space than the wind speed W varies, see Figure 2. Hence the gradient

where

For a homogeneous Gaussian field the velocities have median values equal to

see [8] for proof. The speeds in directions θ and θ − 90˚ will be denoted by

Remark 2 The angle θ depends on properties of the covariance matrix Σ of the gradient

Let Aθ be the rotation by angle θ around the t-axis matrix making covariance between Xx and Xy zero. Then let denote by

where

Example 1 Let consider the following field

where

Obviously Xx is independent of Xy and hence θ = 90˚, see Remark 2. Further

while

In this simple example the median velocities agree with the velocity of the harmonic wave moving along the x-axis.

In Figure 6, variability of the median velocities

4. Statistics of Encountered Wind Speeds

Main subject of the paper is development of a simple model describing variability of wind speeds time series encountered by a vessel or at a fixed location. In this section we will define the model and give means to estimate the long-term CDF of encountered winds; expected duration and strength of an encountered storm.

A ship route is a sequence of positions pi, say, a ship intends to follow. We assume that a ship will follow straight lines between the positions having azimuth

A ship sailing along a route

Figure 6. Top―Estimates of the median velocities, km/h, the windy field moves in direction θ in February and August. The color corresponds to speed. The highest speed (orange) is

where

The process

The long-term CDF of encountered wind speeds is defined by

The CDF given in Equation (16) could be be estimated by fitting an appropriate distribution to available data. (Weibull distribution is often used.) Alternative approach is to compute the theoretical CDF, viz.

4.1. Distributions of Storm Characteristics

Similarly as in Section 3 we will say that a ship encounters stormy conditions at time t if wind speed

The region of stormy conditions consists of time intervals when the wind speed is constantly above threshold u. The intervals will be called storms. Then let Nu denote the number of encountered storms. For example,

Figure 7. Illustration of the definition of stormy, windy weather regions. Top―A route taken in October; Bottom―Solid thick line shows the on- board measured wind speeds. The thin solid line presents variability of the median wind speed along the route. The intervals plotted at level

Let the number of encountered storms for which event (statement) A is true be denoted by

Next the theoretical, based on model, probability of event A, e.g.

The proposed model Equation (15) will be validated by comparing the empirical distribution of storms strength Ast and the average durations of storms with theoretically computed

introduced in [11] , and the expectations

will be used for validation purposes. In Equation (20), Tcl denotes time period when wind speed is uninterruptedly below the threshold u, i.e. a time period between storms. The Equation (20) will be proved in Appendix 2.

In order to evaluate Equation (19) and Equation (20), the formula for

see also [13] . Here

Remark 3 Consider a stationary Gaussian process X with mean m and variance

Consequently the average distance between upcrossing of the mean level m by X is

4.2. Evaluation of

From definition of the encountered wind speed process We it follows that the number of upcrossings of the level w by

In the following we shall use an additional parameter

and write Equation (24) in an alternative form

Note that if Xe is stationary, then

5. Validation of the Model

The proposed model is validated by investigating the accuracy of the theoretically computed distributions with the empirical distributions estimated from data. Firstly at fixed positions p the theoretical statistics of the storm characteristics Ast, Tst and Tcl will be compared with estimates of the statistics derived using ten years of hind- cast data. Secondly, the long-term wind speed distributions encountered by vessels are compared with the theoretically computed distributions using the model and the estimates derived from the hind-cast. The expected number of encountered upcrossing will also be used in the validations. However statistics of encountered storm characteristics will not be used in the validation process. This is because the wind speeds measured on-board ships are biased by captains’ decisions to avoid sailing in heavy storms, reported also in [14] . Some validations of the model at inland locations was presented in [15] .

5.1. Distributions of Storm Characteristics Ast, Tst and Tcl at a Fixed Position

Consider a buoy at position p then

In Figure 8 values of the parameter

The values

The probabilities

Figure 8. Comparison of spatial variability of

Figure 9. Probabilities

Table 1. Long-term (one year) expected storm/calm durations in days.

5.2. Validation-Wind Speeds Encountered by Vessels

Measurements of the wind speed over ground, i.e. ten minutes averages, recorded each ten minutes on-board some ships, are used to validate the proposed model. Since the data are recorded much denser than the hind-cast we have removed high frequencies from the signals (periods above 1.5 hour were removed using FFT). The data used in this study is limited to the North Atlantic and western region of Mediterranean Sea. The accuracy of the theoretically computed long-term distribution of encountered wind speed will be investigated.

First a single voyage operated in late August, shown in the top left plot of Figure 10, is considered. In right top plot of the figure, the measured wind speeds, shown as solid line, are compared with the estimated wind speeds using hind-cast, dashed dotted line. One can see that the two signals are reasonably close.

In the left bottom plot of Figure 10, ten thin lines show the empirical long term probabilities

Figure 10. Top left―A route sailed from Europe to America in late August. Top right― Wind speeds measured on-board a vessel (solid irregular line) compared with their estimates derived from the hind-cast data (dashed dotted line); Bottom left―Comparisons of estimates of the long-term probability

Figure 11. Left―Comparisons of the estimates of the long-term probability

shown. Based on the results presented in Figure 10 and Figure 11, we conclude that the theoretical long term distribution of wind speeds encountered by a sailing vessels agrees well with the distribution derived using hind- cast; and secondly that the routing systems used in planning a route is successful in selecting routes with calmer wind conditions than average one.

In Figure 10, bottom right plot, and in Figure 11, right plot, estimates of

6. Simulation of the Encountered Wind Speeds

Common experience says that wind speeds vary in different time scales, e.g. diurnal patten due to different temperatures at day and night; frequency of depressions and anti-cyclones which usually occur with periods of about 4 days and annual pattern. To follow the claim the transformed observed wind speed field

Now for any voyage one can compute parameters

More precisely, for a ship route

Here

The process

Obviously the integrals in Equation (28) have to be computed numerically. This is carried out using the following approximation

where Zij,

The proposed model gives means for efficient simulation of wind speeds along any ship routes. The parameters

Figure 12. Top―A route sailed in Northern Atlantic in April; Middle―The expected length of encountered windy weather period

Figure 12 bottom plot. The measured wind speeds are presented as the solid thick line while dashed dotted line is the hind-cast based estimate of the speeds.

Note that parameters

7. Conclusion

A statistical model for the wind speed field variability in time and over large geographical region has been proposed. The model was fitted to ERA Interim reanalyzed data. Validation tests show very good match between the distributions estimated from the data and the theoretical computed one from the model. The model was also used to estimate risk of encountering extreme winds and the theoretical estimates agree well with the empirical one. Realistic wind profiles can be simulated using the model.

Acknowledgements

Support of Chalmers Energy Area of Advance is acknowledged. Research was also supported by Swedish Research Council Grant 340-2012-6004 and by

Cite this paper

IgorRychlik,WengangMao, (2014) Probabilistic Model for Wind Speed Variability Encountered by a Vessel. Natural Resources,05,837-855. doi: 10.4236/nr.2014.513072

References

- 1. Dee, D.P., Uppala, S.M., Simmons, A.J., Berrisford, P., Poli, P., Kobayashi, S., Andrae, U., Balmaseda, M.A., Balsamo, G., Bauer, P., Bechtold, P., Beljaars, A.C.M., van de Berg, L., Bidlot, J., Bormann, N., Delsol, C., Dragani, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A.J., Haimberger, L., Healy, S.B., Hersbach, H., Hólm, E.V., Isaksen, L., Kallberg, P., Kohler, M., Matricardi, M., McNally, A.P., Monge-Sanz, B.M., Morcrette, J.J., Park, B.K., Peubey, C., de Rosnay, P., Tavolato, C., Thépaut, J.N. and Vitart, F. (2011) The ERA-INTERIM Reanalysis: Configuration and Performance of the Data Assimilation System. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 137, 553-597.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/qj.828 - 2. Baxevani, A., Caires, S. and Rychlik, I. (2008) Spatio-Temporal Statistical Modelling of Significant Wave Height. Environmetrics, 20, 14-31.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/env.908 - 3. Monbet, V., Ailliot, P. and Prevosto, M. (2007) Survey of Stochastic Models for Wind and Sea State Time Series. Probabilistic Engineering Mechanics, 22, 113-126.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.probengmech.2006.08.003 - 4. Caralis, G., Rados, K. and Zervos, A. (2010) The Effect of Spatial Dispersion of Wind Power Plants on the Curtailment of Wind Power in the Greek Power Supply System. Wind Energy, 13, 339-355.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/we.355 - 5. Kiss, P. and Jánosi, I.M. (2008) Limitations of Wind Power Availability over EUROPE: A Conceptual Study. Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics, 15, 803-813.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/npg-15-803-2008 - 6. Brown, B.G., Katz, R.W. amd Murphy, A.H. (1984) Time Series Models to Simulate and Forecast Wind Speed and Wind Power. Journal of Climate and Applied Meteorology, 23, 1184-1195.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1984)023<1184:TSMTSA>2.0.CO;2 - 7. Longuet-Higgins, M.S. (1957) The Statistical Analysis of a Random, Moving Surface. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 249, 321-387.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsta.1957.0002 - 8. Baxevani, A., Podgórski, K. and Rychlik, I. (2003) Velocities for Moving Random Surfaces. Probabilistic Engineering Mechanics, 18, 251-271.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0266-8920(03)00029-8 - 9. Baxevani, A. and Rychlik, I. (2006) Maxima for Gaussian Seas. Ocean Engineering, 33, 895-911.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2005.06.006 - 10. Podgórski, K., Rychlik, I. and Machado, U.E.B. (2000) Exact Distributions for Apparent Waves in Irregular Seas. Ocean Engineering, 27, 979-1016.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0029-8018(99)00030-X - 11. Rychlik, I. and Leadbetter, M.R. (2000) Analysis of Ocean Waves by Crossing and Oscillation Intensities. International Journal of Offshore and Polar Engineering, 10, 282-289.

- 12. Rice, S.O. (1944) The Mathematical Analysis of Random Noise Part I and II. Bell System Technical Journal, 23, 282332.

- 13. Rychlik, I. (2000) On Some Reliability Applications of Rice Formula for Intensity of Level Crossings. Extremes, 3, 331-348.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1017942408501 - 14. Mao, W., Ringsberg, J.W., Rychlik, I. and Storhaug, G. (2010) Development of a Fatigue Model Useful in Ship Routing Design. Journal of Ship Research, 54, 281-293.

- 15. Rychlik, I. and Mustedanagic, A. (2013) A Spatial-Temporal Model for Wind Speeds Variability. Department of Mathematical Sciences, Division of Mathematical Statistics, Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenbourg, Gothenburg, 1-18.

www.math.chalmers.se/Math/Research/Preprints/2013/8.pdf

Appendix 1: Computation of

The parameter

Obviously

where

Parameter

The variance

and following off-diagonal elements

The ships velocity

Obviously

where the encountered velocity, e.g. the difference between the ship velocity and the wind field velocity is, in the rotated coordinates, given by

In order to interpret components in Equation (35), we need to introduce some additional parameters that describe average size of windy weather regions and some irregularity factors.

Recall that windy weather conditions region at time t is the region consists all p where wind speeds exceeds the median

see Equation (22) and Remark 3. Obviously the values of parameters are slowly changing functions of position and time and that why we call them local sizes of windy regions. However if the field

Now by multiplying both sides of the Equation (35) by

where

are useful irregularity factors. Roughly, smaller values of the factors higher risks of extreme storms, see [9] for more details. Further, if

If p has rotated coordinates then

For a homogeneous wind field

Appendix 2: Proof of Equation (20)

Let assume that

Since

and hence

Appendix 3: Estimation of Parameters

The parameters of the model have been fitted for the North Atlantic. Here the ERA Interim data has been used, although in future work we plan to also use data from satellite based sensors. A moment’s method and regression fit were employed to estimate the parameters. In this section we give a short description of the applied estimation procedure. In the following the measured wind speeds at a location will be denoted by

Step 1: For a fixed geographical location and

residual

Step 2: Estimation of signals

Step 3: For a signal

tions

Step 4: Estimation of