Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics

Vol.02 No.08(2014), Article ID:47578,11 pages

10.4236/jamp.2014.28085

Inversion of Meg Data for a 2-D Current Distribution

George Dassios, Konstantia Satrazemi

Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Patras and ICE/HT-FORTH, Patras, Greece

Email: gdassios@otenet.gr

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 4 May 2014; revised 2 June 2014; accepted 12 June 2014

ABSTRACT

The support of a localized three-dimensional neuronal current distribution, within a conducting medium, is not identifiable from knowledge of the exterior magnetic flux density, obtained via Magnetoencephalographic (MEG) measurements. However, this is not true if the neuronal current is supported on a set with dimensionality less than three. That is, the support of a dipolar current distribution can be recovered if it is a set of isolated points, a segment of a curve, or a surface patch. In this work we provide an analytic algorithm for this inverse MEG problem and apply it to the case where the current is supported on a localized disk having arbitrary position and size within the brain tissue. The proposed recovery algorithm reduces the identification of the characteristics of the current to the solution of a nonlinear algebraic system, which can be handled numerically.

Keywords:

Magnetoencephalography, Inversion of Current

1. Introduction

Magnetoencephalography associates a neuronal current within the functional brain with the magnetic flux den- sity and it creates outside the head. In particular, the direct problem consists of the calculation of the exterior magnetic field when the primary neuronal current is given, and the inverse problem seeks to identify the current that generates a given exterior magnetic field. The main difficulty with the inverse problem of Magnetoencephalography is due to the fact that, besides the excitation of the neuronal current within the conductive brain tis- sue, a secondary induction current is generated which, in a sense, makes the primary neuronal current less “visible” by the exterior magnetic field. The induction current is supported on the conductive brain tissue and therefore it depends on the geometry of the brain-head system. Even for relatively simple geometrical models such as a triaxial ellipsoid the calculations are very complicated [1] . An excellent review of the electromagnetic activity of the human brain can be found in [2] , while the standard book for an introduction of the brain imaging modalities of Electroencephalography and Magnetoencephalography is the book by Malmivuo and Plonsey [3] .

The most important question for the inverse problem is the question of uniqueness, that is, whether it is possi- ble to recover the complete information about the current from the exterior magnetic data. The answer to this question is negative. The fact that a current within a conductor cannot be identified, from measurements of the exterior magnetic field it generates, was known to Helmholtz 160 years ago [4] . However, the problem of deter- mining exactly what part of the current can be recovered was a topic of intense investigation during the last de- cade, and the final answer was given in [5] . A complete discussion of all the existing results on the topic can be found in [6] . Today we know that, no matter what the geometry of the brain-head system is, complete knowledge of the electric potential on the surface of the head can give us no more than one third of the neuronal current, and complete knowledge of the exterior magnetic field can give us no more than two thirds of the neuronal current, one of which is the one obtained from the electroencephalographic measurements. Hence, even in the very difficult situation where we have complete and synchronous data from both electroencephalographic and Magnetoencephalographic data, still one third of the current cannot be identified.

The next question one can ask, in connection to the inverse problem of Magnetoencephalography, has to do with the possibility to identify the position and the extent of a localized current. Albanese and Monk [7] , have shown that this is not possible if the support of the current is a three-dimensional set. However, this is possible if the support of the current is a two-, one-, or zero-dimensional set. That is we can identify a localized current if it is supported on a set of isolated points, on a segment of a curve, or on a surface patch.

The purpose of this work is to provide a concrete example of the Albanese-Monk result. In particular, we con- sider a neuronal current that is supported on a small circular disk, orthogonal to the radius that passes through its center, and we construct an algebraic algorithm that solves the inverse Magnetoencephalographic problem. In fact, the identification of the location and the size of the supporting disk is reduced to the solution of a nonlinear algebraic system which can be solved numerically.

The paper is organized as follows. The solution to the problem of calculating the exterior magnetic potential for a single dipolar current within a conductive sphere is briefly described in Section 2. This solution plays the role of the fundamental solution for the problem of Magnetoencephalography in spherical geometry. Section 3 contains the calculations that lead to the magnetic potential in the case where the source current is distributed on a small disk. Finally, Section 4 develops the algorithm for the inversion of the measured data in the case des- cribed in the previous section. An Appendix at the end of the paper provides some explanations about the long and tedious calculations that are used in Section 3.

2. The MEG Problem for a Single Dipole

Quasi-Static theory of Electromagnetism Magnetoencephalography [8] - [10] assumes that the time derivatives of the electric and magnetic fields are very small and therefore the corresponding terms in Maxwell’s equations can be neglected. Then, it can be shown that the magnetic field, generated by a dipolar current at the point  hav- ing moment

hav- ing moment , is given by the Geselowitz formula [11]

, is given by the Geselowitz formula [11]

(1)

(1)

where  is the electric potential on the boundary

is the electric potential on the boundary  of the conducting medium

of the conducting medium  representing the brain- head system. In Formula (1),

representing the brain- head system. In Formula (1),

denotes the exterior domain,

denotes the exterior domain,  is the constant conductivity of the brain tissue,

is the constant conductivity of the brain tissue,  is the common magnetic permeability both inside and outside

is the common magnetic permeability both inside and outside  and

and  stands for the outward unit normal on the boundary

stands for the outward unit normal on the boundary .

.

If  is a sphere of radius

is a sphere of radius , then we know from the solution of the corresponding Electroencephalography problem [12] , that the electric potential on the boundary of the sphere is given by

, then we know from the solution of the corresponding Electroencephalography problem [12] , that the electric potential on the boundary of the sphere is given by

(2)

(2)

where

and

Inserting expression (2) in the Formula (1) and performing the indicated integration we obtain the magnetic field outside the sphere. However, since the magnetic field

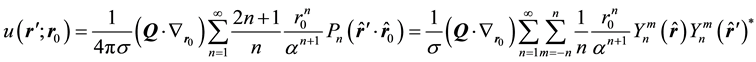

Then, utilizing the orthogonality properties of the spherical harmonics we can calculate the magnetic potential and arrive at the following expression [12] [13]

The above expression provides the magnetic potential in the exterior of the sphere due to a single current dipole {

3. The Field of a 2-D Current Distribution

Suppose now that the neuronal current

where

which, if it is assumed to be small, it can be represented by the linear part of its Taylor expansion

In particular, if the surface that curies the current is a small disk of radius

Utilizing the freedom we have to select a coordinate system we choose the direction

and

where

and

Then, the absence of a term involving

which means that, the left contraction of the dyadic

which gives the three scalar conditions

Consequently, the approximate current (11) is now written as

We can utilize the coordinate invariance principle to simplify our calculations. We actually want to calculate the total magnetic potential, given in (5), which is generated by the approximate current (28). Since our ultimate goal is to invert the MEG data that will give us the quantities

For the generic excitation dipole

and through some direct calculation with the Legend polynomials [17] we obtain the following relations, which are written in dyadic form [16] in order to isolate the factors that are going to be integrated

The symbol

and similarly the triple contraction [16] is defined as

Furthermore, the exterior magnetic potential given in (29) can be written in its Cartesian form [13] , [15] as follows

where the coefficients

are homogeneous harmonic functions [15] .

In order to obtain the magnetic potential, generated by the neuronal current which is distributed over the disk

where

is the vector invariant [16] of the dyadic

The actual calculations that led to the above expressions, and especially to the Formula (32), are involved and quiet long. In order to facilitate the reader we provide, in the Appendix, an outline of the basic steps that lead the above expressions.

If we insert the above expressions of the harmonic functions

4. Inversion of MEG Data

In the previous section we defined the functions

with

and

with

In the present work we assume the idealized case where the exterior magnetic potential

or

where

where the constrain (36) is easily verified.

Next we consider the cubic polynomials (32) and (37). The coefficients of the cubic monomials

The coefficients of the monomials involving the cross-product terms

where it is straightforward to verify the constraints (38)-(40). Finally, from the equality of the coefficients of the product terms

The solution of the above nonlinear system of algebraic equations determines the position, the orientation and the size of the disk that supports the primary neuronal current. A series of numerical tests to obtain the solution of this system show that there exists a unique real solution.

Acknowledgments

The present work is part of the project “Functional Brain”, which is implemented within the “ARISTEIA” Ac- tion of the “OPERATIONAL PROGRAMME EDUCATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING” and is cofunded by the European Social Fund (ESF) and National Resources.

References

- Dassios, G. and Kariotou, F. (2003) Magnetoencephalography in Ellipsoidal Geometry. Journal of Mathematical Phy- sics, 44, 220-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1522135

- Hamalainen, M., Hari, R., Ilmoniemi, R.J., Knuutila, J. and Lounasmaa, O.V. (1993) Magnetoencephalography-Theory, Instrumentation, and Applications to Noninvasive Studies of the Working Human Brain. Reviewed Modern Physics, 65, 413-497.

- Malmivuo, J. and Plonsey, R. (1995) Bioelectromagnetism. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Helmholtz, H. (1853) Ueber einige Gesetze der Vertheilung elektrischer Strme in k orperlichen Leitern mit Anwendung auf die thierisch-elektrischen Versuche. Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 89, 211-233,353-377.

- Fokas, A.S. (2008) Electro-Magneto-Encephalography for the Three-Shell Model: Distributed Current in Arbitrary, Spherical and Ellipsoidal Geometries. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 6, 479-488. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2008.0309

- Dassios, G. and Fokas, A.S. (2013) The Definitive Non Uniqueness Results for Deterministic EEG and MEG Data. In- verse Problems, 29, 1-10.

- Albanese, R. and Monk, P.B. (2006) The Inverse Source Problem for Maxwell’s Equations. Inverse Problems, 22, 1023-1035. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0266-5611/22/3/018

- Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. (1960) Electrodynamics of Continuous Media. Pergamon Press, London.

- Plonsey, R. and Heppner, D.B. (1967) Considerations of Quasi-Stationarity in Electrophysiological Systems. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, 29, 657-664. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02476917

- Sarvas, J. (1987) Basic Mathematical and Electromagnetic Concepts of the Biomagnetic Inverse Problems. Physics in Medicine and Biology, 32, 11-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/32/1/004

- Geselowitz, D.B. (1970) On the Magnetic Field Generated outside an Inhomogeneous Volume Conductor by Internal Current Sources. IEEE Transactions in Biomagnetism, 6, 346-347. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.1970.1066765

- Dassios, G. (2009) Electric and Magnetic Activity of the Brain in Spherical and Ellipsoidal Geometry. In: Ammari, H., Ed., Mathematical Modeling in Biomedical Imaging, Mathematical Biosciences Subseries, Springer-Verlag, 183, 133- 202.

- Dassios, G. (2012) Ellipsoidal Harmonics. Theory and Applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139017749

- Dassios, G. and Fokas, A.S. (2009) Electro-Magneto-Encephalography and Fundamental Solutions. Quarterly of Appli- ed Mathematics, 67, 771-780.

- Dassios, G. and Fokas, A.S. (2009) Electro-Magneto-Encephalography for the Three-Shell Model: Dipoles and Beyond for the Spherical Geometry. Inverse Problems, 25, 1-20.

- Brand, L. (1947) Vector and Tensor Analysis. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- Morse, P.M. and Feshbach, H. (1953) Methods of Theoretical Physics. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Appendix

The four basic integrals we need to calculate are

Choosing

we obtain

Similarly,

and

Finally, for the tetradic integral [16] we obtain

which involves

Therefore, we arrive at the following combination of the survived 21 tetrads

The integral

which, in view of the condition (14), implies that whenever the third vector of a tetrad is the base vector

Substituting

Further manipulations show that

In view of these identities the expression for

The above intermediate calculations are used to derive Formulae (30), (31) and (32), where the special direc- tion