Open Journal of Marine Science

Vol.04 No.03(2014), Article ID:48423,20 pages

10.4236/ojms.2014.43019

Analytical Models for Hurricanes

Arkadii I. Leonov

Departments of Applied Mathematics and Polymer Engineering, The University of Akron, Akron, OH, USA

Email: leonov@uakron.edu

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 4 April 2014; revised 11 May 2014; accepted 30 June 2014

ABSTRACT

A two-layer theoretical model of hurricanes traveling (quasi-) steadily over open seas has been developed. The use of coherency concept allowed avoiding the common turbulent approximations, except a thin sub-layer near the air/sea interface. The model analytically describes 3D distribu- tions of dynamic and thermodynamic variables in hurricanes and analyzes processes of evapora- tion and condensation. Using this modeling, the following fundamental problems were naturally resolved-change in the cyclonic/anti-cyclonic directions of hurricane rotation and the directions of radial wind in lower and upper parts of hurricane; increase in wind angular momentum in hur- ricane boundary layer; dramatic effect of ocean spray and its radial distribution; and a high in- crease in temperature at the upper region of boundary layer. Additionally, integral balances al- lowed expressing the governing parameters of field variables via two external parameters, the sailing wind and temperature of a warm air band, in which direction the hurricane travels. A rude model for the hurricane genesis and maturing has also been developed.

Keywords:

Hurricane, Aerodynamics, Adiabatic and Boundary Layers, Air-Sea Interaction

1. Introduction

The hurricanes (typhoons) have been extensively investigated during the last 60 years. Many of their features have been observed and experimentally studied using satellites, aircrafts, ships, and buoys. These observations created a detailed qualitative picture of hurricane structure, documented in several well-known texts by Dunn [1] , Anthes [2] , Hsu [3] , Cotton & Anthes [4] , Ogawa [5] , and Emanuel [6] .

Some idealized models [7] -[12] of several problems in hurricanes have also been developed. Complicated role of mesovortices in the hurricane eye was experimentally modeled in laboratory and discussed [13] . Lighthill developed a thermodynamic theory of ocean spray [14] , and its effect on the dynamics of near water air turbu- lence was revealed by Barenblatt et al. [15] . Detailed models of coupled interactions between the turbulent wind and oceanic waves near the air/sea interface have also been elaborated in text [16] (Ch. 3). Other conceptual ideas are mixed with numerical studies. Some works [17] -[20] modeled intriguing aspects of hurricane maturing. Many other papers developed turbulent baroclinic and barotropic numerical models (e.g. see paper [21] and ref- erences there). To forecast hurricane travel these models interact with the current synoptic and lower scale ob- servations (see recent extensive reviews in Refs. [22] [23] ).

Yet several fundamental problems in hurricane physics remain unresolved. These are the change in the direc- tions of hurricane rotation and radial wind in lower and upper parts of hurricane, radial increase in wind angular momentum in hurricane boundary layer, dramatic effect of ocean spray and its radial distribution, and a high in- crease in temperature at the upper region of boundary layer. The problems of hurricane genesis and maturing are also currently vaguely addressed.

Thus the main objective of this paper is to resolve the above problems by developing and analyzing some quantitative models, based on the author’s results [24] -[27] pre-published in Arxive. The models being rude enough still provide a consistent analytical description of the basic physical phenomena in hurricanes. The con- ceptual view of hurricanes as coherent structures, allows avoiding the common turbulent approximations except friction factors at the air/sea interface. The use in the model the aerodynamics of ideal gas requires implement- ing continuity for dynamic variables to avoid the Kelvin-Helmholtz (K-H) instability. Additionally, integral balance equations allow expressing all parameters in the distributions of field variables via only two external parameters―the sailing wind and temperature of warm air band the hurricane travels along.

The paper is organized as follows. The next Section briefly discusses the external forces causing horizontal travel of hurricanes, thermodynamics of air, dynamics of ideal liquids, and hurricane structure. Section 3 models the basic airflows in the upper layer of hurricane. Section 4 models the basic processes in the hurricane boun- dary layer. The last, Section 5 presents simple analytical models for hurricane genesis and maturing.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Horizontal Travel of Hurricanes

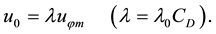

Two factors affect the horizontal travel of hurricane: 1) stirring or “sailing” wind with velocity

and 2) “af- finity” motion with velocity

and 2) “af- finity” motion with velocity

because of hurricane’s tendency for accepting warmer air from environment. The value

because of hurricane’s tendency for accepting warmer air from environment. The value

is unknown and should be found with solving problem. The additivity principle

is unknown and should be found with solving problem. The additivity principle

holds for describing horizontal hurricane travel.

holds for describing horizontal hurricane travel.

2.2. Aerodynamic Equations for Air Flows

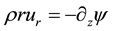

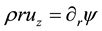

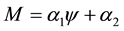

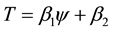

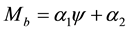

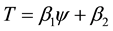

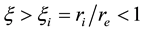

We consider air motions in hurricane as axially symmetric flows of ideal compressible gas. The frame of refer- ence used below is a cylindrical coordinate system with vertical

-axis directed upward, slowly traveling in a horizontal direction. The axially symmetric motions of air relative to the local Earth rotation have very well known form (e.g. see Equations (1.7)-(1.10) in [24] ). In the stationary cases, these equations yield two first in- tegrals, which present the angular momentum M and temperature T as arbitrary functions of the stream function

-axis directed upward, slowly traveling in a horizontal direction. The axially symmetric motions of air relative to the local Earth rotation have very well known form (e.g. see Equations (1.7)-(1.10) in [24] ). In the stationary cases, these equations yield two first in- tegrals, which present the angular momentum M and temperature T as arbitrary functions of the stream function .

.

2.3. Thermodynamics of Humid Air

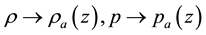

Far away from hurricane, the atmosphere is assumed to be horizontally homogeneous with vertically distributed ambient density

pressure

pressure

and temperature

and temperature . These distributions are described by the equilibrium equations within the thermodynamics of humid ideal gas [28] .

. These distributions are described by the equilibrium equations within the thermodynamics of humid ideal gas [28] .

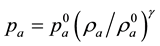

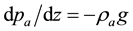

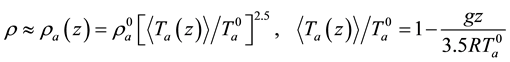

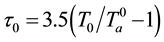

Using adiabatic description of air,

, (1)

, (1)

and the static equation,

, (2)

, (2)

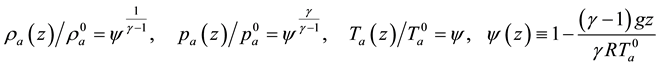

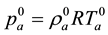

the vertical distributions of thermodynamic parameters are presented as:

. (3)

. (3)

Here

with

with

being ambient parameters at the surface,

being ambient parameters at the surface,

is the adiabatic index, and

is the adiabatic index, and

and

and

2.4. Hurricane Structure and Basic Processes

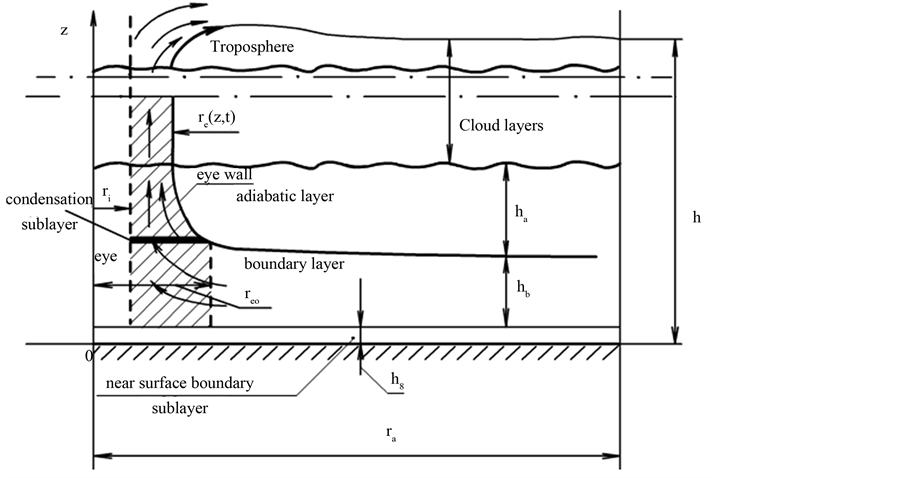

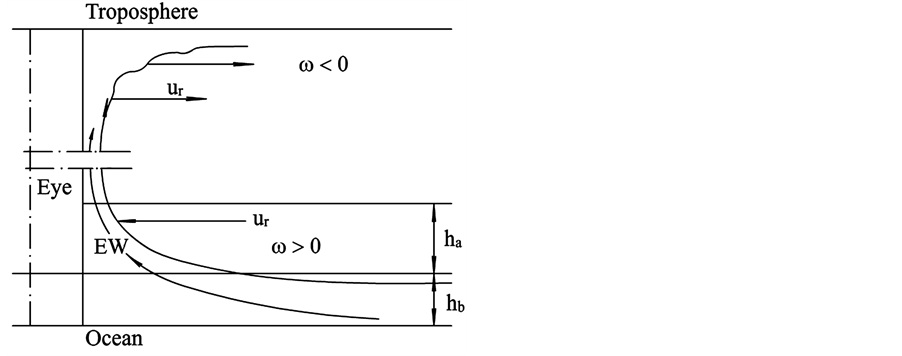

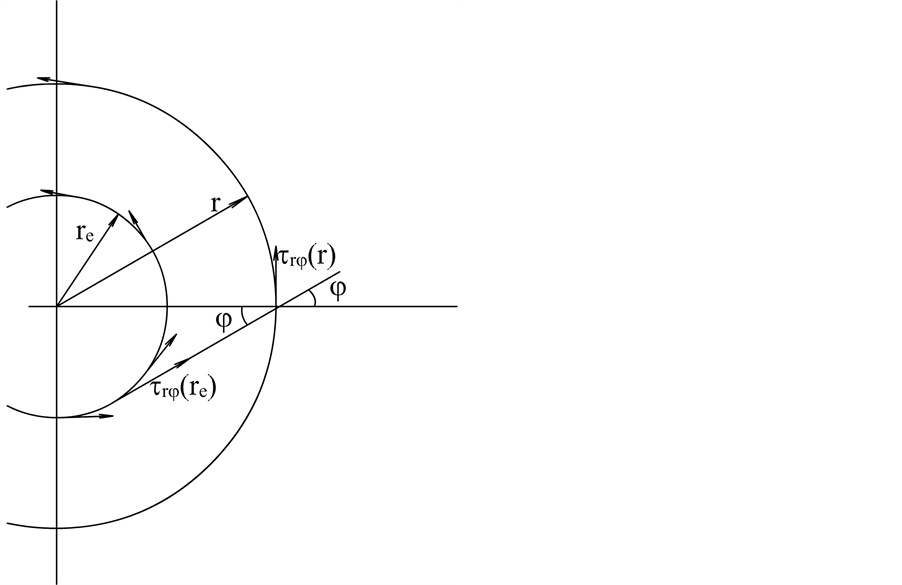

A typical structure of a mature hurricane traveling (quasi-) steadily over the open sea is sketched in Figure 1. The hurricane is viewed as a solitary vertical air vortex rotating in the cyclonic direction near the bottom with additional radial and vertical air flows. It has a central “eye”, a vertical column of radius

The vertical structure employed in the following models, includes the turbulent boundary sub-layer of thick- ness

In the HBL, the air-sea interaction directly affects the dynamics at the air/sea interface, generating oceanic waves which in turn interact with air flows in the outer part of HBL. There is also evaporation and the heat/mass exchange between the hurricane and environment. The moisture, sensible and latent heats are transported via HBL towards the EW jet. The height of HBL is limited by air moisture condensation, which causes the forma- tion of spiral rain bands, layered clouds and rainfall from them. Dynamic effects of rainfall can seemingly be neglected, though the rainfall can balance the evaporation from the oceanic surface. This results in a constant sa- linity level in the oceanic boundary layer.

Figure 1. Schematic structure of a hurricane.

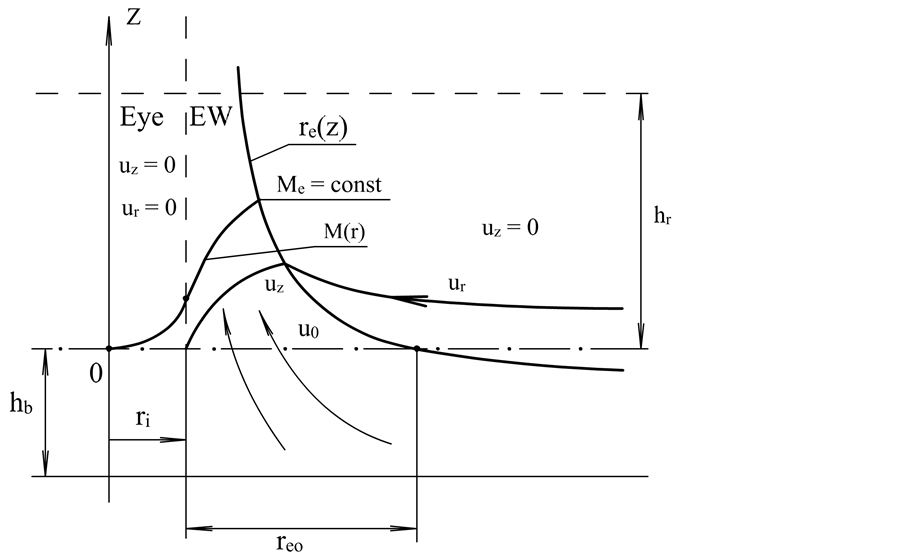

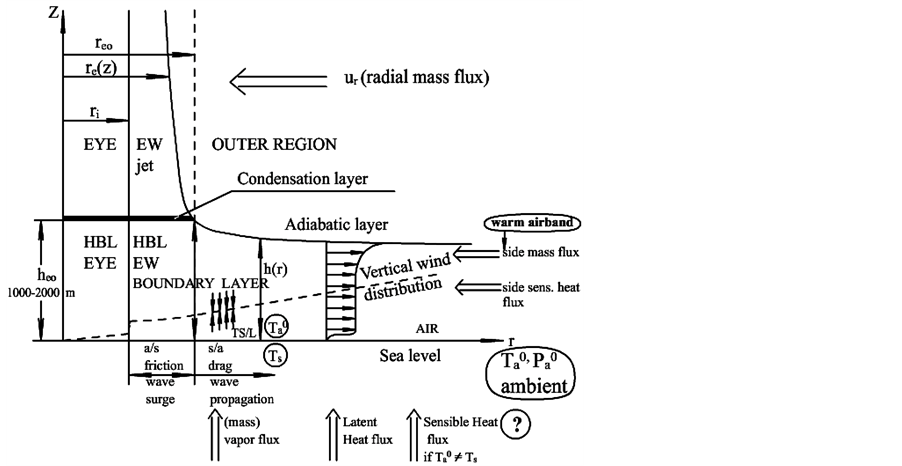

3. Model of Adiabatic Layer for Steady Hurricane [25]

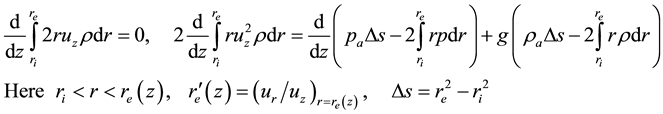

Neglecting the air band effects, air flows in upper layer of hurricanes can be modeled using the adiabatic ap- proximation. The structure and basic flows in the hurricane adiabatic layer is sketched in Figure 2, and the air- flows there are axi-symmetric. Here is a solid-like rotation of air in the eye region, and no vertical wind compo- nent exists in the outer region of hurricane. For convenience, we use in this Section the vertical axis z shifted upward by the height

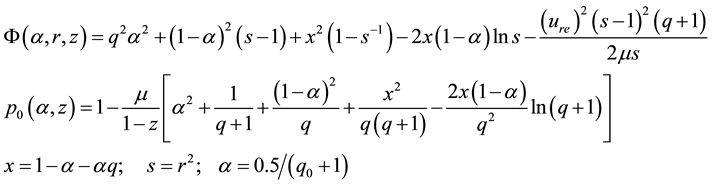

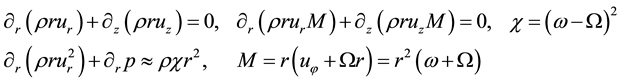

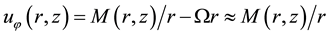

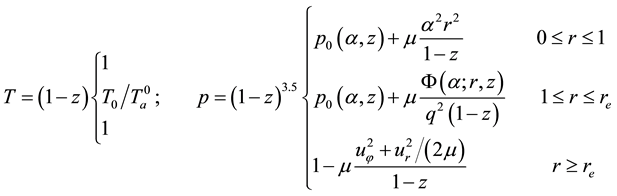

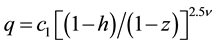

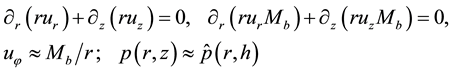

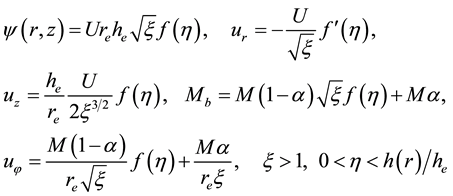

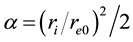

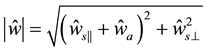

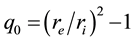

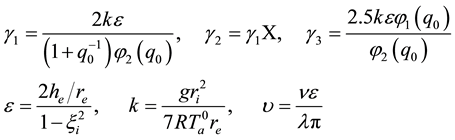

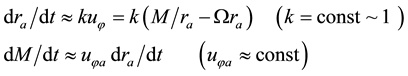

The following modeling equations are used below [25] :

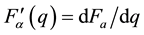

In aeromechanical Equations (4),

We now introduce two simplifying approximations:

(i)

Here (6i) presents the “well mixing” assumption introduced by Deppermann [30] , and independency from air rotation introduced in (6ii) has been justified in Ref. [25] .

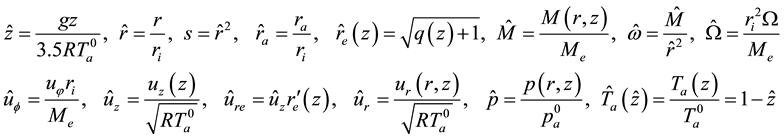

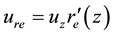

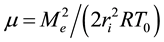

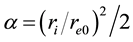

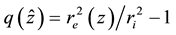

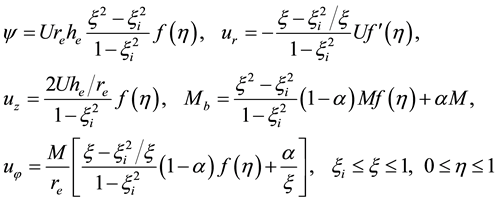

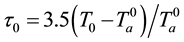

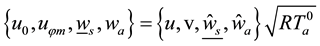

It is convenient to introduce the non-dimensional variables:

Figure 2. Sketch of adiabatic layer.

Here

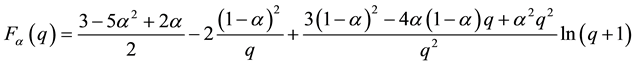

Tedious calculations of set (4) with approximations (6) yield the explicit expressions for radial non-dimen- sional distributions of dynamic variables:

The approximation

Formulas (8) show that streamlines in hurricane are the circles in eye and outside EW, and ascending spirals in EW with kinks at

Here

There are simple asymptotic solutions of (9) in two limiting cases.

1)

Here

2)

When

It was found that the numerical solution of steady problem (9) exists only for physically feasible case

The values of calculated parameters are:

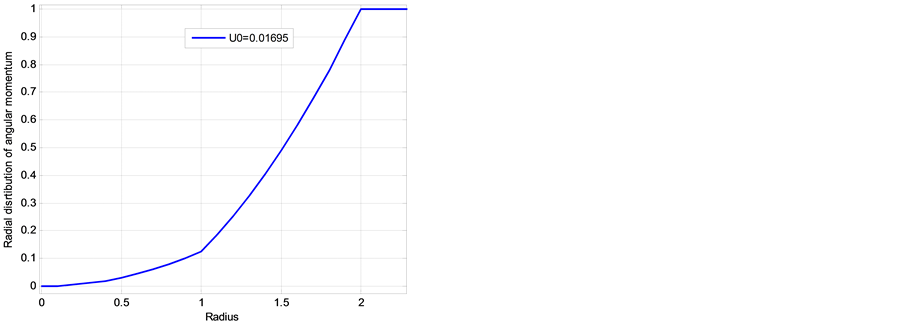

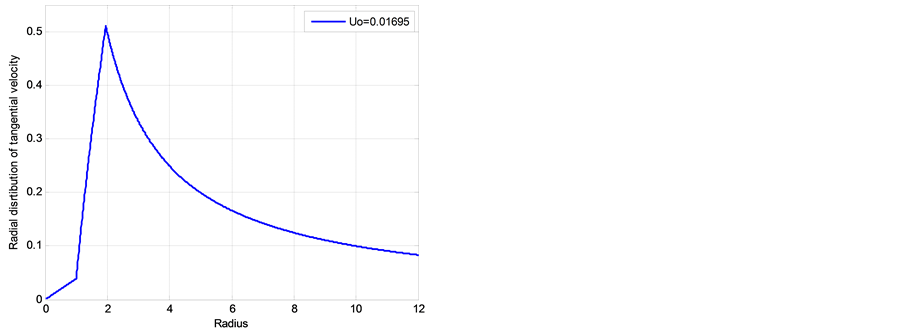

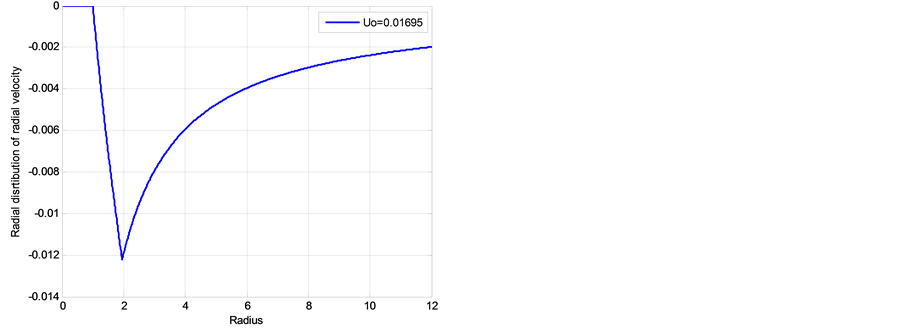

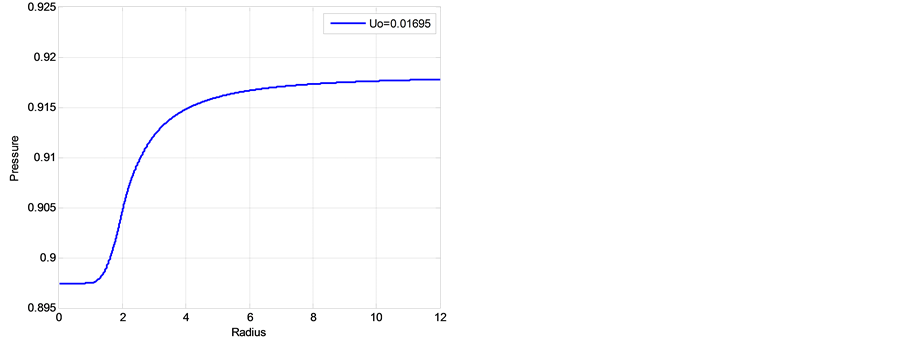

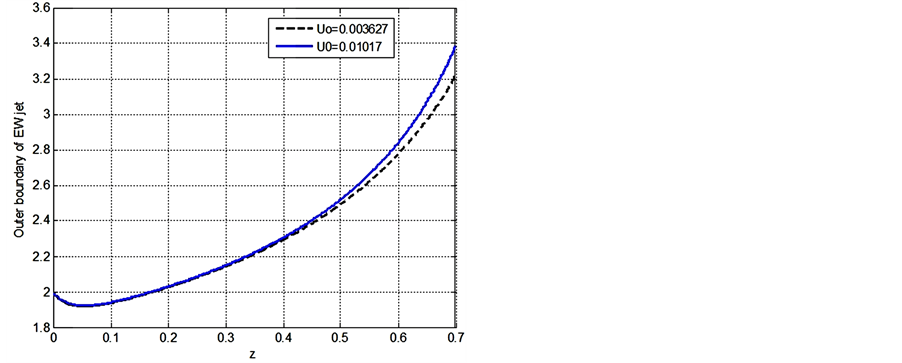

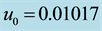

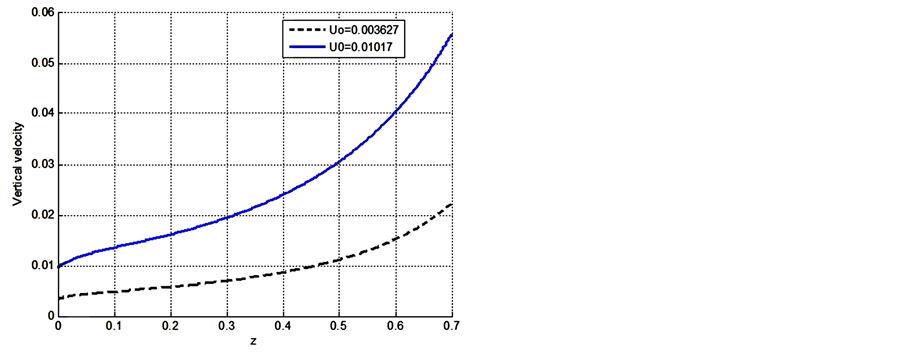

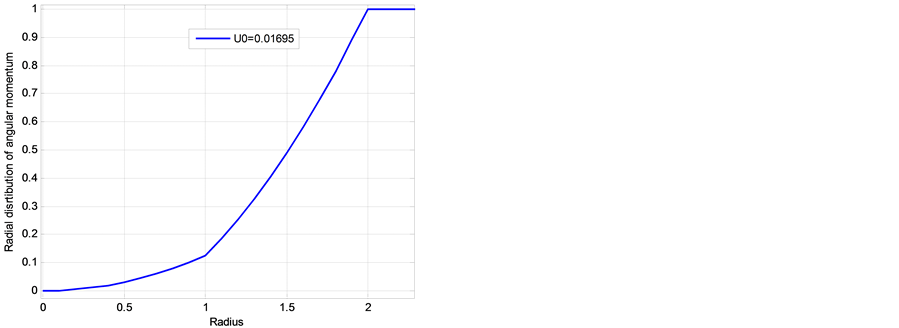

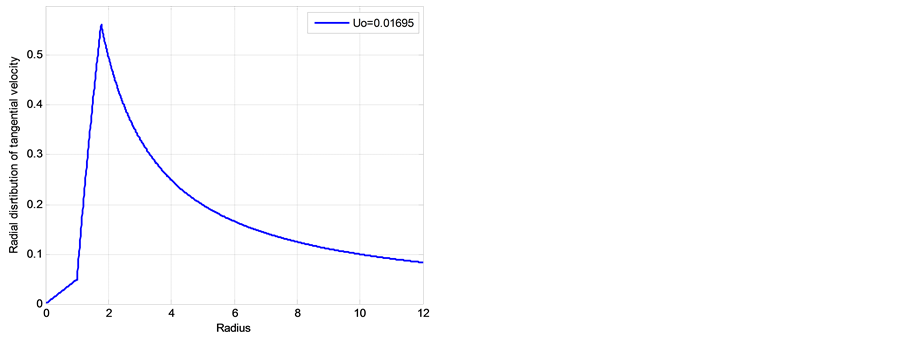

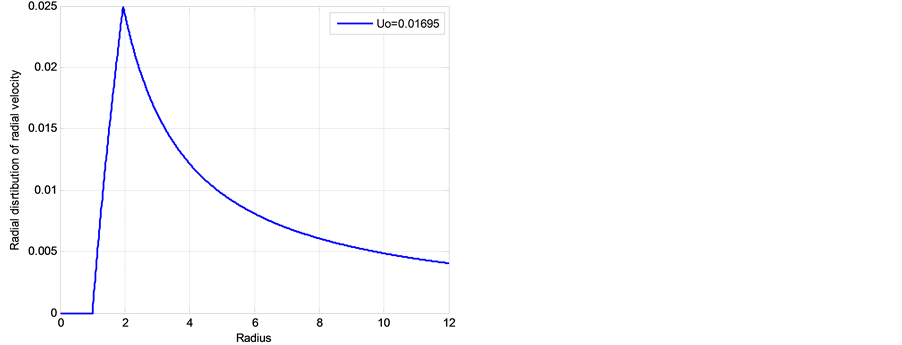

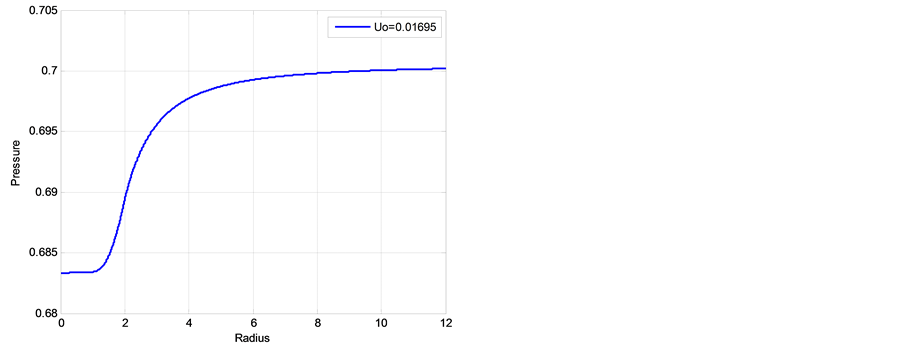

Figures 3-9 illustrate the calculated radial distributions of basic variables, depending on altitude and initial value of vertical velocity

Figure 3. Non-dimensional altitude dependence of outer boundary of EW jet

Figure 4. Non-dimensional altitude dependence of vertical velocity

Figure 5. Vertical distribution of non-dimensional angu- lar velocity

Figure 6. Non-dimensional radial distributions of angular momentum

Figure 7. Non-dimensional radial distributions of tangential velocity

negative (centripetal) at lower and positive at higher altitudes, with absolute maximum at the outer boun dary of EW jet. Finally, Figure 9 show two similar radial distributions of pressure which display a characteristic “depression” area at the center of hurricane. These results support a well-documented characteristic structure of hurricane sketched in Figure 10. Additionally, the radial distributions of tangential velocity and pressure at the bottom of adiabatic layer were found in [25] in a good agreement with these obtained using semi-empirical modeling and observation data by Deppermann [30] .

4. Modeling the Boundary Layer in Steady Hurricane [26]

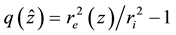

The structure and basic interactions in hurricane boundary layer (HBL) are sketched in Figure 11. Here the HBL is horizontally separated in the same three regions as in previous Section: the eye, HBL EW, and outer HBL region, the latter having generally a curvilinear upper surface. There are two major vertical sub-sections in HBL: upper aerodynamic and lover turbulent ones. Additionally, there is a condensation sub-layer located at the top of HBL EW and assumed to be very thin (~100 m). The height

Figure 8. Non-dimensional radial distributions of radial velocity

Figure 9. Non-dimensional radial distributions of pressure

Figure 10. Sketch of the total vertical distribution of EW jet.

Figure 11. Cross-sectional sketch of HBL and diagram of air/sea interactions.

depression at the sea surface. The common evaluation

4.1. Fluid Mechanical Effects in HBL

They include coherent aerodynamic airflows in upper part of HBL, turbulent airflows in lower part of HBL, and dynamic interaction of oceanic waves with HBL airflows.

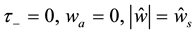

4.1.1. Aerodynamic Airflow

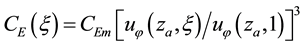

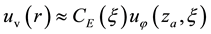

Models employ simplified equations of aerodynamics of ideal gas similar to Equations (4) with

Omitting the

The same assumptions as in the previous Section are employed here: the rigid-like airflow in HBL eye, the radial independence of vertical wind in HBL EW, and the same boundary conditions at the inner HBL EW in- terface. It is also assumed that the outer upper boundary

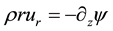

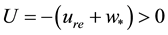

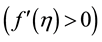

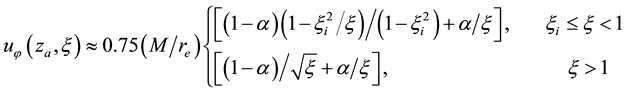

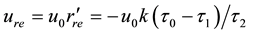

Introducing the stream function

Here

At the upper boundary HBL EW,

condition at

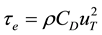

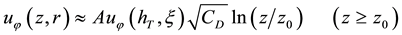

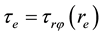

4.1.2. Airflow in Turbulent Sub-Layer

A huge air wind near the radius

waves propagating outside this region. The radial wind contribution can be neglected in this sub-layer because of very low variation assumed for

We use for friction factor

height

Evaluation of the roughness factor

4.1.3. Interaction of Air Wind and Oceanic Waves

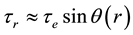

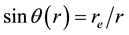

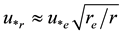

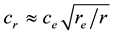

The radial increase in angular momentum

Consider the oceanic waves initiated in the vicinity

Here the low indexes “e” and “r” denote the values of variables at the radii

Table 1. Values of roughness parameter

Figure 12. A sketch of skew interactions of oceanic waves with turbulent air in HBL.

4.2. Physical Effects in HBL

Evaporation from the oceanic surface and latent heat. Over calm oceanic water, the vertical air flux (per unit mass of vapor) caused by moisture evaporation can be approximated as

Here

Consider an example. Using (15) with

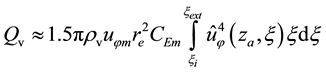

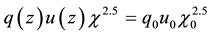

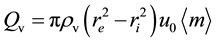

Using (15) and (17), the total mass flux of evaporation

Here

Transfer of sensible heat is considered in the steady model under condition of complete sea/air temperature balance

Condensation is assumed to happen in a relatively thin vertical layer whose height is less than hundred meters, where the over-saturated vapor comes into the upper layer of HBL. Neglecting the thickness of the layer, it is considered as a weak condensation jump, which is described by basic equations including the conservation of vertical fluxes of mass, momentum and energy [34] . For a weak jump these equations are reduced to the conti- nuity of mass flux, pressure and enthalpy on the jump interface, averaged over EW radius:

Since the differences between velocities, pressures and densities over the jump are negligible,

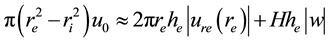

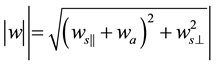

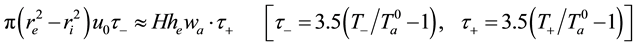

4.3. Integral Balances in the HBL Eyewall

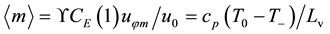

The average temperature

In the following we use the plane Cartesian axes

4.3.1. Mass Balance of Dry Air in HBL

Two fluxes of the “dry” air masses come from HBL to the EW jet via the bottom of adiabatic layer: 1) the flux from the radial airflow into the HBL and 2) fresh air coming because of horizontal travel of hurricane. Neglect- ing density variations, the balance is:

Here

4.3.2. Balance of the Sensible Heat in HBL Reads

In (22) the differences between heat capacities are neglected. The left-hand side of (22) describes the heat en- tering the hurricane condensation layer with unknown temperature

4.3.3. Oceanic Vapor Mass Balance Is

Here

Balance of the latent heat is presented by second formula in (18).

Assuming that the oceanic vapor is completely condensed in the condensation layer, the last formula in (19) along with (23) yields two useful chain equalities:

The values of

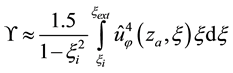

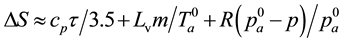

Entropy balance, detailed in [26] , starts with the well-known equation:

Here entropy

Here numerical parameter

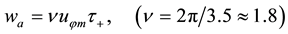

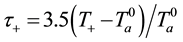

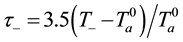

Affinity velocity of hurricane travel was determined in [26] , assuming the stream from warm air band is effec- tively mixed by dominant tangential air wind,

Thus, all the unknown parameters,

Recall that the non-dimensional temperatures

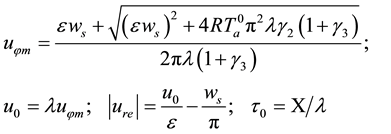

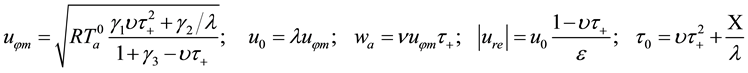

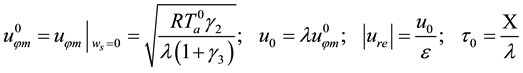

It is convenient to introduce non-dimensional wind components, scaled with the adiabatic speed

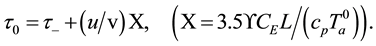

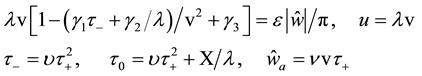

The above relations yield the five equations for parameters

Here

[25] , and non-dimensional constants

Substituting

1) External sensible heat supply is negligible―

One can see that due to (30)

2) Sailing wind is negligible―

Formulas (31) show that

In the limit cases,

Formulas (32) show that the steady, rotating hurricane can exist even without horizontal travel. Here the heat supply

4.4. Numerical Illustrations

1) Accepted and calculated parameters

Geometrical parameters known for the “standard” hurricane are:

Physical parameters are―

Note that values

Parameters calculated from (29) are shown in Table 2.

2) Results of calculations. Using Table 2, the basic variables of hurricane for both cases were calculated and shown in Table 3 and Table 4. It was shown in [26] that the stability condition

In both the cases, the most striking result of calculations is a high increase in temperature

Table 2. Calculated non-dimensional parameters of standard hurricane.

Table 3. Results of calculations of basic variables in hurricane travel under given values of sailing wind

Table 4. Results of calculations of basic variables in affine travel of hurricane under given values of

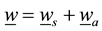

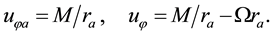

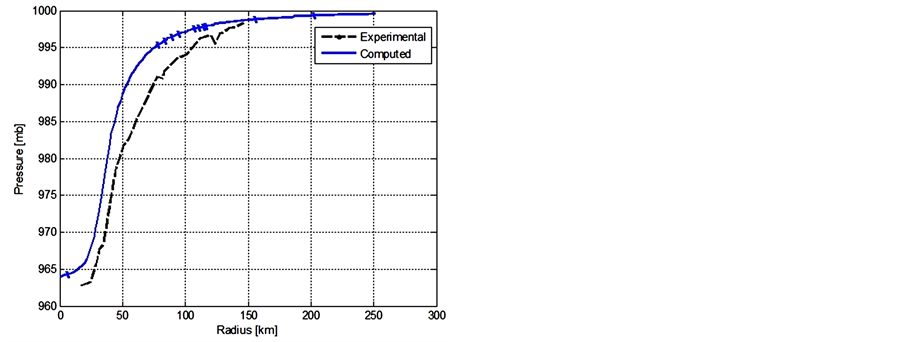

Calculations of the radial distributions of surface pressure and wind for hurricane Frederic, 1979, using the data according to paper [31] , were detailed in Ref. [26] . Comparison of data with our rough calculations is shown in Figure 13(a) and Figure 13(b).

5. On the Hurricane Genesis and Maturing [27]

The emergence of hurricanes is still mysterious. Many observations of initial stages of hurricanes (e.g. see the text [2] ) found a threshold value of vorticity, exceeding which the hurricane is maturing. Analyses in papers by Ooyama [17] [18] and Emanuel [19] [20] have a mutual defect-adjustable diffusivity of angular momentum to fit the data. Also, most hurricanes in Atlantics are formed in near equator zone, indicating the importance of Co- riolis factor, which was not considered in the above papers.

Paper [27] proposed a two-steps scenario of hurricane’s genesis. In the first step, an emerged plume of warm and humid air formed in the near equator zone, moves upward (see the model of plume dynamics in [27] ). In the second step, the plume captures the rotation from a horizontally sheared wind, with restructuring of the plume and acquiring an initial value of angular momentum. If this plume is stable, the maturing stage begins. In this case the hurricane grows in the radial direction, presumably caused by the K-H instability with radial propaga- tion into ambient air under action of Earth rotation.

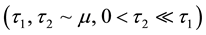

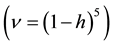

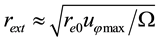

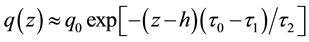

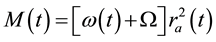

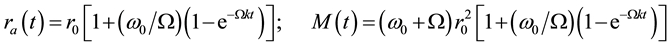

To describe the maturing stage of hurricanes we first consider the quasi-static relation for angular momentum extended to the external boundary

The absolute

The slow evolution of

The first equation in (35) describes propagation of the hurricane front due to the K-H instability with the rela- tive rotational velocity at the boundary

Figure 13. Comparison of our adiabatic calculations and measurements [31] for radial distributions of tangential wind and surface pressure for hurricane Frederic for measurements on 09/11/1979: (a) Tangential wind; (b) Surface pressure; maximal wind speed

to the radial propagation of unstable boundary is the dominant contribution in the change of angular momentum.

The initial conditions are:

Here

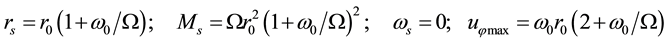

The solution of Equations (33)-(35) with conditions (36) is:

Formulas (37) show that depending on sign

1) In the cyclonic case

2) In the anti-cyclonic case

Thus the model selects as only stable, the cyclonic initial rotation, which naturally explains the observed cy- clonic rotation of matured hurricanes. However, the model does not describe the observed threshold in value of

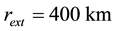

To illustrate the model predictions we choose the following parameters

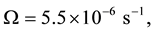

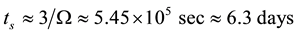

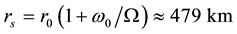

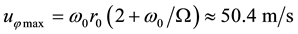

i) Characteristic time of hurricane development:

ii) Characteristic radius of developed hurricane:

iii) Maximum speed of developed hurricane:

iv) The grow of angular momentum: from

These results are consistent with observations in text [2] that the initial tropical cyclone is transformed into a hurricane during 5 - 6 days after the action of wind with vorticity

6. Conclusions

The paper presents analytical two-layer hurricane model. The approach employed in the paper uses simplified aerodynamic equations for ideal humid gas with additional models for heat transfer, evaporation and condensa- tion. It mostly avoids the common turbulent approximations, except a thin near-water sub-layer.

Analysis of adiabatic aerodynamic modeling in the hurricane upper layer reveals a “hyperboloid” structure of eye wall (EW) jet. The radial and vertical distributions of basic variables have been theoretically calculated. It was found that upper layer of hurricane is stable when the thermal heat supplied into the layer exceeds the adia- batic cooling. The model also explains the change in the cyclonic/anti-cyclonic directions of hurricane rotation, as well as the directions of radial wind component in lower and upper parts of hurricane.

The model of hurricane boundary layer (HBL) employs aerodynamic approach only in its upper sub-layer and matches it with the turbulent approach in its lower sub-layer. The increase in the wind angular momentum in HBL is explained as an additional generation of wind by ocean waves propagating out of HBL EW. A dramatic effect of ocean spray and its radial distribution on evaporation has been modeled taking into account the ocean whitecaps generated by wind. A high increase in temperature in the upper sub-layer of HBL has been modeled by the condensation jump.

The balance relation applied to the HBL EW, presented the basic parameters governing the space distributions of field variables in hurricane via two external parameters-the sailing wind and horizontal temperature of a warm air band.

Additionally, a rude model for the hurricane genesis and maturing has also been developed. It explains the reason of cyclonic rotation of hurricanes.

All examples in the paper demonstrated a good correspondence with the existing observations when using common data for geometrical, fluid mechanical and thermodynamic parameters of hurricane.

It finally should be noted that developing the hurricane structure during hurricane genesis and maturing presents a very challenging numerical problem which by no means could be resolved by simplified analytical approaches.

The results of the paper could be used for easy tune-up of complicated numerical models, which take into ac- count real interaction of hurricane with environment.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Dr. A. Benilov for extensive and highly productive discussions, as well as the participants of Physical Science Division Seminar at NOAA in Boulder, CO (July, 2012). A lot of thanks are also given to for- mer PhD Student, Dr. A. Gagov for help in calculations and graphics, and Dr. A. Voronovich for patiently read- ing the paper and making valuable suggestions.

Cite this paper

Arkadii I.Leonov, (2014) Analytical Models for Hurricanes. Open Journal of Marine Science,04,194-213. doi: 10.4236/ojms.2014.43019

References

- 1. Dunn, G.E. (1951) Tropical Cyclones. In: Compendium of Meteorology, American Meteorological Society, Boston, 887-901.

- 2. Anthes, R.A. (1982) Tropical Cyclones, Their Evolution, Structure and Effects. American Meteorological Society, Science Press, Ephrata, 208 p.

- 3. Hsu, S.A. (1988) Coastal Meteorology. Academic Press, New York, 260 p.

- 4. Cotton, W.R. and Anthes, R.A. (1989) Storms and Cloud Dynamics. Academic Press, San Diego, 883 p.

- 5. Ogawa, A. (1993) Vortex Flow. CRS Press, Inc., Boca Raton.

- 6. Emanuel, K.A. (2005) Divine Wind. Oxford University Press, New York, 285.

- 7. Emanuel, K.A. (1983) An Air-Sea Interaction Theory for Tropical Cyclones. Part I. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 42, 1062-1071.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1985)042<1062:FCITPO>2.0.CO;2 - 8. Emanuel, K.A. (1995) The Behavior of Simple Hurricane Model Using a Convective Scheme Based on Subcloud Layer—Entropy Equilibrium. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 52, 3959-3968.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1995)052<3960:TBOASH>2.0.CO;2 - 9. Emanuel, K.A. (1999) Thermodynamic Control of Hurricane Intensity. Nature, 401, 665-669.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/44326 - 10. Holland, G.I. and Merrill, R.T. (1984) On the Dynamics of Tropical Cyclone Structural Changes. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 110, 723-745.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/qj.49711046510 - 11. Holland, G.J. (1997) The Maximal Potential Intensity of Tropical Cyclones. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 54, 2519-2541.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1997)054<2519:TMPIOT>2.0.CO;2 - 12. Bister, M. and Emanuel, K.A. (1998) Dissipative Heating and Hurricane Intensity. Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics, 65, 233-240.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01030791 - 13. Montgomery, M.T., Vladimirov, V.A. and Denissenko, P.V. (2002) An Experimental Study on Hurricane Mesovortices. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 471, 1-32.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022112002001647 - 14. Lighthill, J. (1999) Ocean Spray and the Thermodynamics of Tropical Cyclones. Journal of Engineering Mathematics, 35, 11-42.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1004383430896 - 15. Barenblatt, G.I., Chorin, A.J. and Prostokishin, V.M. (2005) A Note Concerning the Lighthill Sandwich Model of Tropical Cyclones. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102, 1114811150.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0505209102 - 16. Kagan, B.A. (1995) Ocean-Atmospheric Interaction and Climate Modeling. Cambridge University Press, New York, 377.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511628931 - 17. Ooyama, K.V. (1982) Conceptual Evolution of the Theory and Modeling of the Tropical Cyclone. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan, 60, 369-379.

- 18. Ooyama, K.V. (1983) Numerical Simulations of Life Cycle of Tropical Cyclones. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 26, 3-40.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1969)026<0003:NSOTLC>2.0.CO;2 - 19. Emanuel, K.A. (1989) The Finite Amplitude Nature of Tropical Cyclogenesis. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 46, 3431-3456.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1989)046<3431:TFANOT>2.0.CO;2 - 20. Emanuel, K.A. (1997) Some Aspects of Hurricane Inner-Core Dynamics and Energetic. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 54, 1014-1026.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1997)054<1014:SAOHIC>2.0.CO;2 - 21. Liu, Y., Zhang, D.-L. and Yao, M.K. (1997) A Multi-Scale Numerical Study of Hurricane Andrew, 1992. Part I: Explicit Simulation and Verification. Monthly Weather Report, 125, 3073-3093.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1997)125<3073:AMNSOH>2.0.CO;2 - 22. Wang, Y. and Wu, C.-C. (2004) Current Understanding of Tropical Cyclone Structure and Intensity Changes—A Review. Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics, 87, 257-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00703-003-0055-6

- 23. Chan, C.L., Duan, Y. and Shay, L.K. (2001) Tropical Cyclone Intensity Change from a Simple Ocean-Atmosphere Coupled Model. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 58, 154-172.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(2001)058<0154:TCICFA>2.0.CO;2 - 24. Leonov, A.I. (2008) Aerodynamic models for hurricanes I. Model description and horizontal motion of hurricane.

http://arxiv.org/abs/0812.3173 - 25. Leonov, A.I. (2008) Aerodynamic Models for Hurricanes II. Model of the Upper Hurricane Layer.

http://Arxiv.Org/Abs/0812.3176 - 26. Leonov, A.I. (2008) Aerodynamic Models for Hurricanes III. Modeling Hurricane Boundary Layer.

http://arxiv.org/abs/0812.3178 - 27. Leonov, A.I. (2008) Aerodynamic Models for Hurricanes IV. On the Hurricane Genesis and Maturing.

http://arxiv.org/abs/0812.3180 - 28. Curry, J.A. and Webster, P.J. (1999) Thermodynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans. Academic Press, London, 467.

- 29. Yarin, A.L. (1993) Free Liquid Jets and Films: Hydrodynamics and Rheology. Longman Sci. & Tech. with John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 446 p.

- 30. Deppermann, C.E. (1947) Notes on the Origin and Structure of Philippine Typhoons. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 28, 399-404.

- 31. Powell, M. (1982) The Transition of Hurricane Frederic Boundary Layer Wind Field from the Open Gulf of Mexico to Landfall. Monthly Weather Review, 10, 1912-1932.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1982)110<1912:TTOTHF>2.0.CO;2 - 32. Zhao, D. and Toba, Y. (2001) Dependence of Whitecup Coverage on Wind and Wind-Wave Properties. Journal of Oceanography, 57, 603-615.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1021215904955 - 33. Hwang, P.A. and Sletten, M.A. (2008) Energy Dissipation and Wind-Generated Whitecup Coverage. Journal of Geophysical Research, 113, Article ID: CO2012.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2007JC004277 - 34. Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. (1986) Theoretical Physics. Vol. IV: Fluid Mechanics. Section 132 (in Russian), Nauka, Moscow, 733.

Appendix: Structural Functions in the Section 3