Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.2 No.2(2012), Article ID:20430,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2012.22009

Prioritising, downplaying and self-preservation: Processes significant to coping in advanced cancer patients

![]()

1Department of Surgery, Roskilde and Koege Hospitals, Roskilde, Koege, Denmark

2Research Unit of Nursing, Institute of Clinical Research, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

3Research Unit of Nursing, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark

Email: #thst@regionsjaelleand.dk, t@grotheonline.com

Received 8 November 2011; revised 12 December 2011; accepted 18 January 2012

Keywords: cancer; coping and adaptation; palliative care; grounded theory

ABSTRACT

To date there has been little research that describes the relation between the individual and their environment as the foundation for the coping process in advanced cancer patients. The aim of the study was to identify and describe, from a patient perspective, processes that are significant to coping with advanced cancer. We used the method Grounded Theory as described by Strauss and Corbin. Data were generated through qualitative interviews. A total of 18 interviews were conducted. The central theme was “The struggle to be a participant in one’s own life”. This theme involved three processes: prioritising, downplaying and self-preservation, each of which in different ways endeavours to either maintain or reestablish the feeling of being a participant. The awareness of the processes complement existing knowledge about coping in advanced cancer patients, by showing how patients make use of meaning-based coping efforts to increase their experience of being a participant in their own lives.

1. INTRODUCTION

When the status of patients with advanced cancer changes from that of being a cancer patient in active treatment to being in the palliative stage of the treatment with little or no chance of surviving the illness, their ability to express and cope with their physical, psychosocial and spiritual problems deteriorates greatly [1,2]. In this situation patients express an increasing need for professional support to cope with their suffering [2-4]. From a patient perspective one of the great challenges in providing a professional support system is that the support from healthcare professionals may be dominated by a focus on symptom treatment and effectiveness and there may be less focus on individual and situation-determined needs [1,4-7]. With a view to developing a professional support system that is designed to better enable the patient to cope, it is necessary to increase our knowledge about coping in advanced cancer as seen from a patient perspective.

In this study, coping is understood as “constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” [8,9]. In a review that draws upon relevant research in the period 1996-2006 we show how coping strategies have been pivotal in coping research from the patient perspective [10]. The limitation of focusing on coping strategies could be that coping appears to be presented exclusively as a behavioural pattern in patients, instead of being founded in the dynamic relationship between the individual and their environment [8]. Lazarus therefore recommends that, in addition to studies that employ measurements and questionnaires to reveal actual coping strategies, qualitative studies also be carried out that identify how patients evaluate the conditions they experience in the actual situation that underpins the coping process [8:125]. Thus a study by Davies and Sque [11] shows how eight women with advanced breast cancer facilitated their re-entry into everyday life through “reconciling a different me”, which described the ongoing process of adaptation and coping. Research further shows how patients with an advanced cancer struggle to cope with the illness and simultaneously maintaining their routine daily lives [12,13] and living a life with continued meaning [14].

The collective research in the area points to coping in advanced cancer patients as a complex process. At the same time it is clear that only very little research deals with the connections between factors that characterise coping. The article forms part of a larger, grounded theory study focusing on key characteristics of coping—and the connection between the key characteristics—in advanced cancer patients seen from a patient perspective. In another article we show how coping involved four significant life conditions: Alleviation from a life-threatening illness, Carry on a normal life, Live with powerlessness and Find courage and strength. Each of the four life conditions was characterised by both coping limitations and coping resources [15].

The aim was to identify and describe processes that, from a patient perspective, are significant to coping in advanced cancer patients.

2. METHODS

We chose to employ the grounded theory method, as described by Strauss and Corbin [16,17] because a particular coding layer in a Strauss and Corbin-inspired methodological approach called “axial coding” allows for intense coding around significant categories. This made it be possible to reveal and describe processes significant to coping [16,17]. From the epistemological viewpoint, the method is firmly rooted in the pragmatic and symbolic, interactive perspective [17,18]. The method is described as an inductive-deductive process, where comparative analysis is continually carried out [16].

2.1. Participants

We invited 23 patients to participate in the study. They were admitted to seven medical and surgical departments in the Capital Region of Denmark during the period June 2006-March 2009. Eleven patients declined: seven due to tiredness; one because of breathlessness; one considered it would interfere with her control over her situation; two preferred to devote their energies to other activities, and one died before the first interview. One patient was excluded due to confusion. Ten patients between 43 and 80 years of age (mean age 61) consented to participate: four women (mean age 58) and six men (mean age 62). The patients had known of their cancer diagnosis for between one month and three years (mean 18 months). Seven were married and three were divorced. Three had children of less than 18 years of age. The patients represented all the “social groups”, i.e. social groups I - IV, which is a Danish-developed measure of social status based on placement in “higher” or “lower” social classes [19].

2.2. Screening Procedure

To be included in the study patients had to be over 18 years of age, born in Denmark and Danish-speaking. Additionally, it should be evident in the patient’s records that any continued treatment would be of a palliative nature or that at least one course of treatment for relapse had not had a satisfactory effect on the cancer condition. In advance of being interviewed, it was ascertained that the participants had scored 24 points or more in Folstein’s “Mini-Mental State Examination” (MMSE), which is proven to be applicable as a screening test of cognitive function in cancer patients [20]. A score of fewer than 24 points was an exclusion criterion. This did not occur in this study.

A range of principles was employed in the screening process [21]. One such principle was availability, which meant that the first patients were chosen as soon as they were identified by the chosen departments. Another principle was variation, both in cancer type and socialdemographic terms. A third principle was development over time, which allowed for time-related variation in coping to be studied, as the patients were interviewed three times at intervals of approximately one month, on condition that they had enough energy to undergo an interview and their illness allowed it. A fourth principle employed was theoretical sampling [16,17,21], where the patients were chosen according to the descriptive needs of the emerging categories and theory. By employing the principle “theoretical sampling” it was possible to study specific aspects of the developed categories. This principle also supported the assessment of the point when new data no longer led to new theoretical insights nor identified new features in relation to the theoretical categories, i.e. when “theoretical saturation” was reached [16:143].

2.3. Interview Process

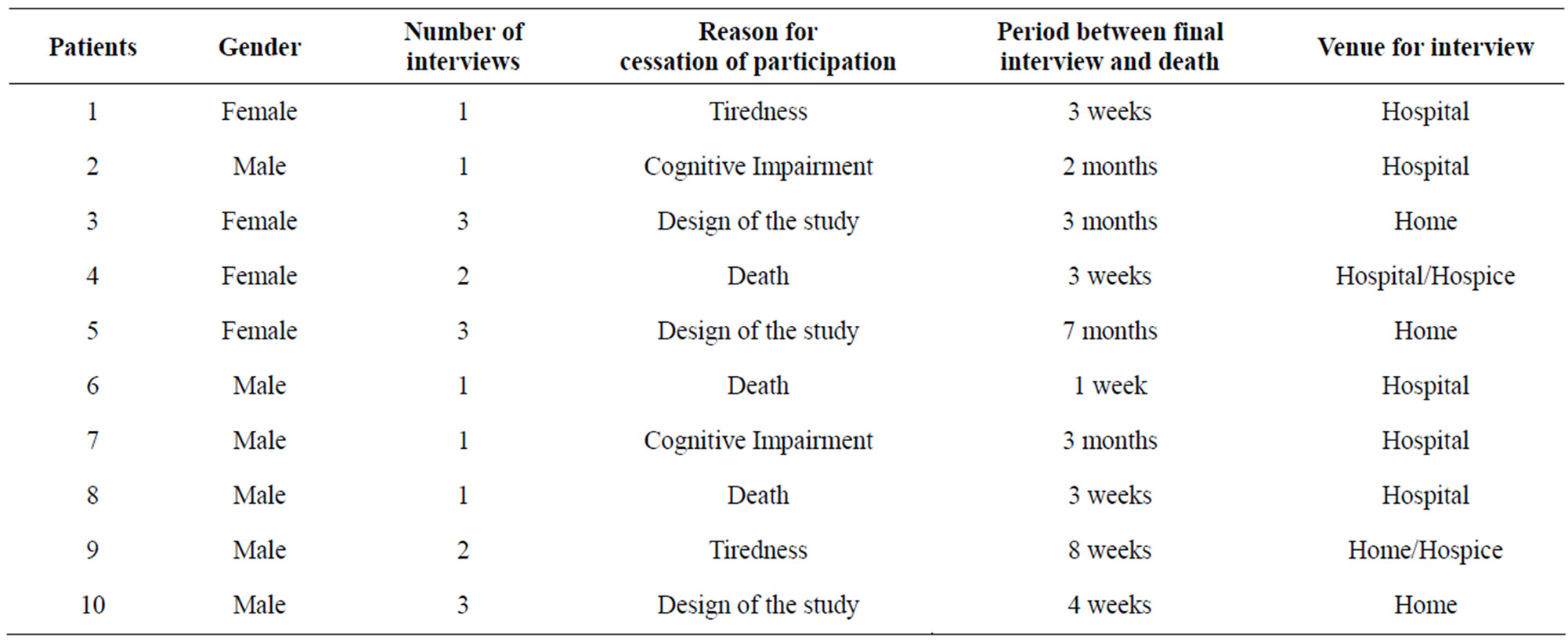

A total of 18 interviews were carried out. Interviews lasted between 45 minutes and two hours (mean 80 minutes). The interviews were carried out where the patient was accommodated at that time; either in hospital, at home or in a hospice—see Table 1.

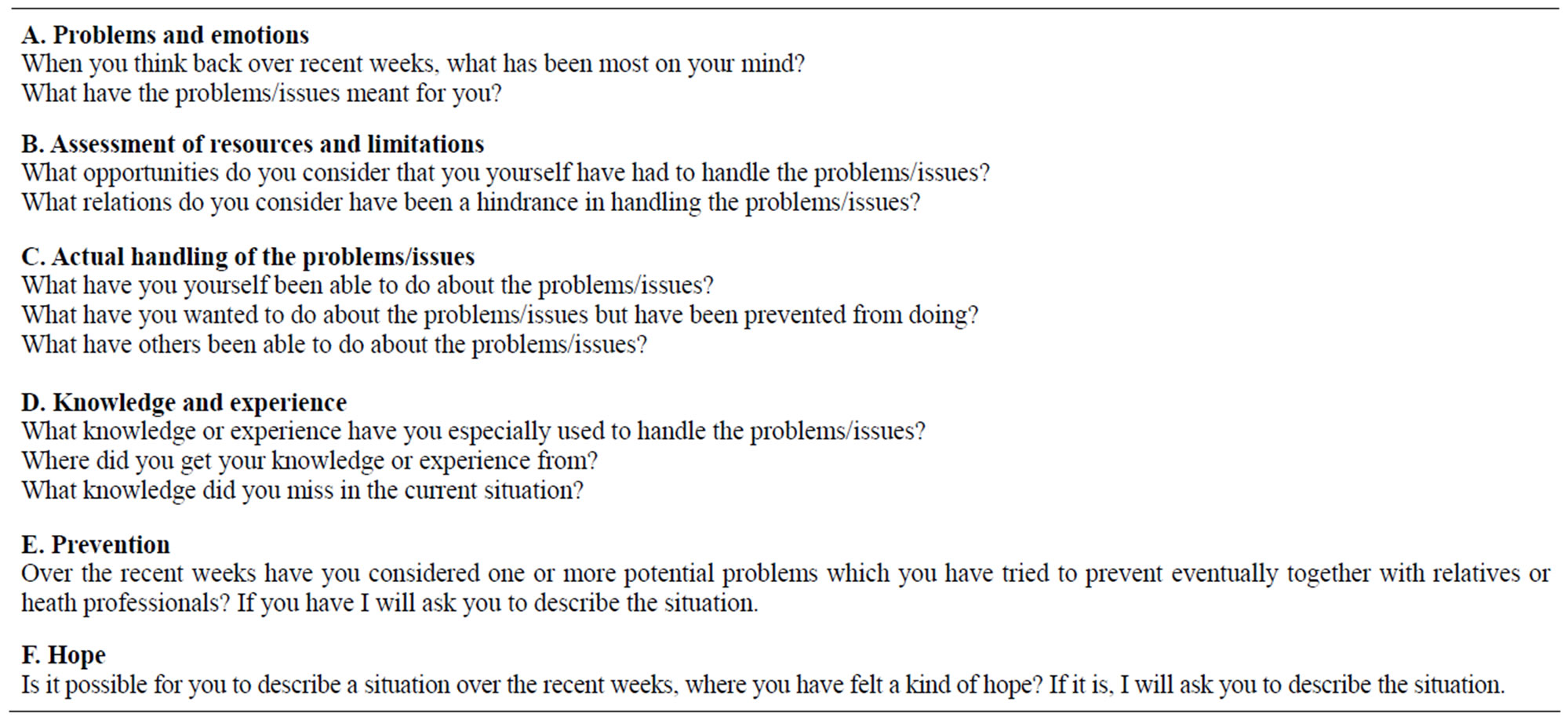

One researcher carried out all the interviews. In the first interviews a semi-structured interview guide was used in the conversation, which ensured that significant information about coping in advanced cancer patients was collected. The semi-structured interview guide was inspired by Lazarus and Folkman’s understanding of the connection between problems, emotions, assessment and coping [8,9]. The following themes were included in the questions: Problems and emotions, assessment of resources and limitations, actual handling of the situation, knowledge and experience, prevention and hope—see Table 2. Over time the interview guide was refined to make it possible to develop and validate categories and processes that were revealed through the analysis [16].

Table 1. Interview characteristics.

Table 2. Themes in the semi-structured interview guide and examples of questions.

By using different types of question, e.g. follow-up questions and specifying questions, the interviewer continually encouraged the patients to describe in their own words their experiences in assessing and coping with their current situation and/or issues. The interviewer was also careful to check agreement between what was said and her own understanding of the words. Whenever implicit or unclear descriptions arose, for example, interpreting questions were used to check meaning [22]. Furthermore, silence was actively employed in the interviews. The interviewer used silence to allow the patient to make associations and to reflect. In many cases it was considered necessary to pause the interview, and start recording again only when the patient said that she/he was ready to continue. On a very few occasions the interviewer was challenged by emotional engagement in the patient’s situation, which entailed a break in the interview technique. The transcripts however showed that there was no systematic error in this regard.

3. ETHICS

The study touched on themes that could bring up intimate and unconscious or repressed thoughts and feelings [23,24], which necessitated an assessment of whether individual patients were capable of participating in the study and understanding patient information. The assessment was made in consultation with health staff who knew the patient. Patients were informed both orally and in writing about their rights, the scope of the study, and that at all times they could determine for themselves what they wanted to, and felt they could participate in. All included patients gave their informed consent. The patients expressed that it was a relief to be able to tell someone, who had time and the willingness to listen, about their current situation. They further expressed that it was meaningful for them to contribute to a study that over time could help to improve the coping conditions associated with an advanced cancer illness. The study was approved by the local Scientific Ethical Committee, number KF 01297281, and registered with the Data Authority.

4. ANALYSIS PROCESS

All interviews were recorded on a minidisc and transcribed verbatim. The inductive-deductive process was carried out as three, not necessarily sequential, analysis steps: open, axial and selective coding [16,17]. In all three analysis steps memos were written, which retained and systematised thoughts and ideas about the connections and patterns between the components of the analysis [25].

“Open coding” is defined as: “Breaking data apart and delineating concepts to stand for blocks of raw data. At the same time, one is qualifying those concepts in terms of their properties and dimensions” [17]. The open coding was commenced immediately after undertaking the first interview. In the open coding the individual interview was analysed by breaking up the text into smaller meaning units. By addressing questions in each unit of meaning and by undertaking constant comparisons between the meaning units it was possible to specify what the unit was about and on this basis to identify the categories. In the process the analysis gradually became more and more focused on the most effective and stable categories.

Axial coding is defined as: “The process of relating categories to their subcategories, termed ‘by dealing with axial’ because coding occurs around the axis of a category, linking categories at the level of properties and dimensions” [16]. Corbin and Strauss [17] recommend that in this coding phase the analytic focus be placed on both context—which is also termed “structural context” or “structure”, see for example Strauss and Corbin [16]—and process. With reference to the aim of the current article, we will focus particularly on process. According to Corbin and Strauss process can be defined as “sequences of actions/interactions/emotions changing in response to a set of circumstances, events, or situations” [17]. Corbin and Strauss mention several advantages in analysing data for process. It allows the relations between the developed categories to be infused with a kind of “life” or movement. In addition process coding serves to encourage the researcher to incorporate variation in the findings and thereby to look for new patterns. Thus process coding is an essential aspect in the development towards a substantive grounded theory. One way to code for process is, according to Corbin and Strauss, to pose questions such as “What happens?” and “What conditions and activities connect a series of events with other series of events?” [17]. In the current study the process coding was most obvious in specific memos, because the ongoing memo-writing made it possible, by using few or many words, to describe the processes which emerged, for example by addressing the above questions in the data.

Selective coding is defined as “the final step in analysis—the integration of concepts around a core category and filling in of categories in need of further development and refinement” [16]. Selective coding thus allowed us to nuance and refine both the theory’s core category, which represents the main theme or central tendency in the developed theory, and the integration between the core category and other categories. One element in the selective coding was integrative diagrams, which from a visual perspective helped us to focus on the logical integration between concepts and categories and between the core category and sub-categories [16]. The selective coding stopped when theoretical saturation was achieved [16].

5. ASSESSMENT OF VALIDITY

The research process was assessed on an ongoing basis by giving critical attention to each step of the process. Similarly, all codings, memos and critical reflections were systematised to ensure both stringency and transparency. The empirical foundation of the study was maintained by undertaking continual comparative analyses at each step and between the steps. At the same time these analyses supported the control of systematics, variation and density at all three steps of the analysis [22, 26].

The meaning of what the patients said was validated by the researcher, who enquired about what was said, and repeated interviews with the same patient allowed for further exploration and validation of what the patient had said. By giving the patient space to describe in their own words their experiences of assessing and coping with their current situation and/or issues, the researcher ensured that it was the patients’ assertions that constituted the foundation for the development of a grounded theory and not an analytical framework developed in advance. After each interview the researcher wrote down her immediate reflections and hypotheses in a research diary, thereby ensuring that the verbal and non-verbal assertions could be followed up in the subsequent interviews, and which could lead to further exploration [27]. Many of the patients subsequently told the researcher that the interviews had given them the opportunity to formulate their own thoughts and feelings, which had been a good experience. The patients’ assertions helped to validate that the interviews were not experienced as an extra burden in an otherwise highly vulnerable situation. In order to avoid bias the connections between the developed categories and sub-categories were discussed frequently in the research group. They were also discussed in relevant clinical and research situations so that the researcher could ascertain to what extent the findings found resonance with health professionals’ own clinical experience [16,17].

6. FINDINGS

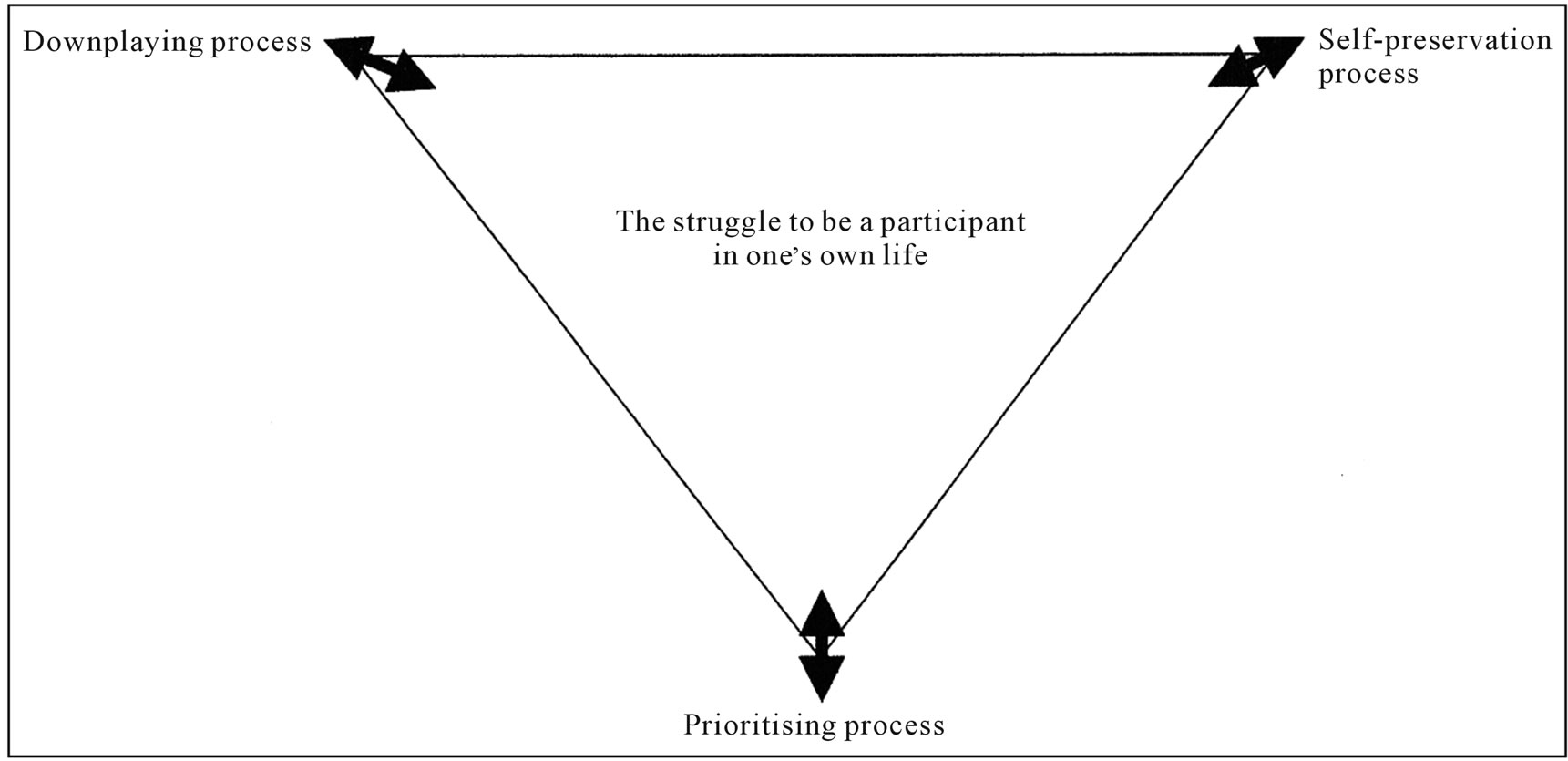

A pattern emerged around a central theme “The struggle to be a participant in one’s own life”, that involved four significant life conditions [15] and three processes: Prioritising, Downplaying and Self-preservation. The three processes in different ways were seen to underpin the patients’ continual struggle to maintain or re-establish the experience of participating. We describe the central theme below and thereafter set out the processes in more detail—see Figure 1.

6.1. The Struggle to Participate in One’s Own Life

All the patients found themselves at a stage where they experienced their progressive illness and the many accompanying social and relational challenges as an intense pressure, which could be felt both physically and mentally.

Coupled with this they also described how thoughts about the severity of the situation and the possibility of becoming a burden on those around them cropped up constantly. Enduring and coping with the pressure was incredibly demanding, and the patients often became overwhelmed by strong emotional reactions, which on the one hand meant that at times they could not think clearly, acted unfocusedly and could no longer take the initiative and control that they otherwise would have done. However, the constant pressure also prompted patients to fight for, and put a lot of energy and strength into, maintaining or re-establishing the feeling of influence on life despite of little or no hope of surviving the illness—that is in this context, being a participant in their own lives.

A central element in “the struggle to be a participant in one’s own life” was that the patients had the opportunity to act in ways that, despite their failing powers and lack of energy, gave them a sense of being able to affect or steer the situation they found themselves in at that moment, and thereby have a meaningful influence on their lives. In the process of discovering how to act appropriately in their actual situation, the patients used to a great extent the knowledge or experiences they had from before the onset of the illness. However the situation was so unique that the patients often found themselves without a precedent, and therefore did not have any specific knowledge or experience to draw upon. A consequence of this was that the patients either gave up and became passive, tried to move forward as best they could, or threw themselves into gathering knowledge and information, especially from the internet, because the health professionals had a tendency to give different or more knowledge and information than the patient needed which could lead to an increase in uncertainty and anxiety. Therefore the patients often left it to their relatives to gather knowledge, which in a way made them feel both

Figure 1. Model to illustrate the connection between the central tendency and three processes developed from data.

more secure and relieved, but which at the same time could mean that the relatives and professionals began to take over more and more. Consequently some patients felt dependent on the relatives and thereby less autonomous.

However, one common factor among all the patients was that the participant role involved three different processes which supported the patient’s coping abilities.

6.2. The Prioritising Process

The central theme involved Prioritising. Prioritising was shown to be a process where the patents fought to be an active participant in relation to judging, prioritising and finally deciding which actions and interactions to take or not to take. There was a big difference between what patients included in the prioritisation process. Several patients described how they were happy to leave the responsibility for symptom alleviation and palliative care to the health professionals, because over time they had come to acknowledge that they symptoms were of such a character that neither they nor their relatives could do anything about them. At the same time it was described as very significant that the patients were well informed about plans for symptom alleviation and possible palliative care, so that they could evaluate and prioritise which practical and social steps were important to take there and then; how they most appropriately could use their failing powers and energy, and who they considered the most wanted to spend time with.

In relation to the prioritising process, several patients described how it made them very happy, either alone or with relatives, to set out realistic, short term goals, that helped them to hold firmly onto what should be done and when. In this way it was easier to keep an overview of an otherwise pressured and sometimes chaotic situation. It was, however, essential, that the goals were constantly reviewed, so they fitted the ever-changing situation. Many patients described how they often spent time and energy on making lists of purely practical tasks that they wanted to have control over, before they finally would have to give up on life.

The prioritising process was largely based on the patients’ accumulated knowledge and experience about what had helped in similar situations. At the same time, many patients expressed confusion, and to a certain extent astonishment, about how the health professionals in some situations apparently did not consider the patients’ experiences to be as important as factual knowledge about, for example, the effects of medicines. One patient told how he had experienced that if he sat in a certain way he could reduce the increasing pains. Therefore he prioritised spending money on buying a new chair. However, his experience was that it was difficult to get help to buy the right chair, because the health professionals considered that the pains would be best alleviated by changes to his medicine. The example clearly shows how the prioritisation process could be characterised by conflicts between patients and health professionals, but the conflicts also showed up between patients and relatives which made it vulnerable for the patients to undertake this process, and many patients felt both alone or sad, despite feeling and knowing what was right for them to do in the specific situation.

6.3. The Downplaying Process

To be a participant in one’s own life furthermore involved Downplaying, which was visible in how the patients put time and energy into making sure that the illness and its consequences did not take up more time than absolutely necessary in their lives. The patients thus spoke of how, on the one hand, they were forced to prepare themselves to live with increasing symptoms and palliative care for the rest of their lives. On the other hand, however, they described how important it was, whether or not they were admitted to hospital, that they had the opportunity to continue to live out aspects of the life that they had built up over many years together with their relatives. Without that, there was no point in living.

The downplaying process was closely linked to the possibility of maintaining and adapting daily customs and activities which really meant something to the patients. All the patients, however, described how admission to hospital made it almost impossible to maintain customs and habits because the whole hospital organisation was based on system logistics, which to a far greater extent were designed to meet the needs of the system and not the advanced cancer patient’s struggle to be a participant in their own life. During admission, therefore, small daily activities, such as wearing one’s own clothes and taking a drive or a short walk out in the sun to hear the birds sing and for a short while experience life outside the hospital, took on a great significance in relation to downplaying the invading illness and perhaps even for short periods completely drop all thought of the illness and possible death. In the same way, receiving visits—as far as the patients’ energies allowed—emails, telephone calls or SMS’s, also from more distant acquaintances, held great significance, because it meant that the patients still had social worth and were not completely forgotten, despite their serious illness.

Patients living at home described how they constantly fought to adapt everyday customs and activities, so that they and their families could continue to live out the life that they had built up together over the years. That could mean that far more “ready meals” were bought, or that the children had to take on more chores, such as tidying up, shovelling snow, etc. At the same time it was significant to all the patients to move and use their body as much as their failing strengths allowed, in that it gave an immediate feeling of doing something good for oneself and strengthened the feeling of being present and alive.

In connection with living out their usual lives and maintaining and adapting habits and daily activities, family members and close friends were indispensable, both because they often came just when they could see there was a need of their help with practical tasks, and because their company gave the patients the feeling of social worth. On the other hand the situation was vulnerable, because the patients feared that over time they would become dependent on help from friends, family and health professionals and would end up being a burden on those around them.

At the same time, living at home and knowing that one could be sure of immediate access to a familiar department gave a great degree of security, that was based on an assurance that contact to health professionals who knew the patient’s situation could quickly be established, and that they would act quickly if illness-related questions arose or if there was an acute deterioration in the illness.

6.4. Self-Preservation

Finally, the central theme involved Self-preservation. Self-preservation was shown to be a process, which made it possible for patients to suddenly find themselves face to face with a feeling of powerlessness and yet not lose their strength and courage to face reality and continue live. Specifically, the use of self-preservation could manifest in patients mixing thoughts and talk of their own death and funeral with, for example, the language of music, faith and spirituality. Thus, one patient often made use of a German saying: “Wenn die Sprache aufhört, dann fängt die Musik an” [When the talking stops, the music begins], where after he would completely spontaneously throw himself into a description of which music should be played at his funeral and other thoughts about the funeral. Another patient, while describing what his Christian faith meant to him, suddenly began to relate about a very difficult conversation that had taken place the day before, where he had been confronted with his own death completely unprepared. Afterwards, he returned to talking about his increasing religious faith.

Similarly, it was possible to tolerate powerlessness when patients got the opportunity to carry out specific actions that they themselves judged to be significant in their situation. Thus, several patients described that the powerlessness became more tolerable when they threw themselves into fighting the uphill battle for instance by finding the treatment that could prolong their life a little. Other patients described how finding an inner peace or balance allowed them for a brief moment not to relate to the powerlessness.

All the patients described self-preservation as a very personal and often intimate process, which the patients usually kept to themselves or certainly only involved those with whom they had a relationship built upon mutual understanding and respect, and where the patients felt sure that what they said would be kept confidential. This could include close relatives or very good friends, but it could also include health professionals who meant something special to the patient. The most crucial factor, however, was that it was the patient him/herself who controlled when and what they talked about.

7. DISCUSSION

The identification of the central theme “The struggle to be a participant in one’s own life” and the pattern that unfolded around it, involving three processes: Prioritising, Downplaying and Self-preservation, was an important finding that adds to existing knowledge about coping in advanced cancer patients.

The process of Prioritising can be considered a cognitive appraisal of the situation, where the individual evaluates what the actual situation means to them, and based on this identifies coping efforts that give meaning to the person in that specific situation [28]. According to Link et al. advanced cancer patients draw upon a wide range of internal and external factors, when they choose specific coping strategies—for example: the personal approach, previous experiences, personal belief system, coping styles, personal goals, perceptions of illness and the influence of others, e.g. physicians and cancer survivors [29]. The findings indicate that advanced cancer patients involve “relational meaning” when choosing appropriate coping strategies. According to Lazarus and Folkman relational meaning is an essential part of the appraisal process, which refers to a constant interaction between personal and environmental factors, although it is the person themselves who in the end judges what the situation means to them [8,9]. Relational meaning can explain why it is apparently significant for patients to be actively participant in evaluating and prioritising specific actions. At the same time relational meaning can also explain why some patients in the study experienced the prioritising process as a conflictual and vulnerable process, in that a personal judgement of a hugely complex and often totally chaotic situation necessarily opens up relational conflicts and conflicts of interest. Based on this, further research is necessary to develop specific tools that are capable of supporting patients—and their relatives—to evaluate and prioritise which coping efforts are most appropriate in the situation—see for example White [30].

A second process found in this study was Downplaying, where patients on the one hand accepted that in certain situations they had to focus on the illness and its consequences, while in other situations it was supremely important to live out that life they had built up over many years with their relatives, because it was here they found meaning in life. A similar process was found in a study of Houldin and Lewis [12], where an interview study demonstrated how 14 patients with terminal cancer fought to find a way of living where it was possible to balance between the illness and normal life. The patients’ struggle to both relate to the burdensome illness and to a meaningful life can be understood as a perspective shift between illness and wellness. The concept of the perspective shift between illness and wellness is elaborated in a meta-study, what included 292 qualitative studies pertaining to chronic physical illness [31]. The study shows chronic illness as an ongoing, continually shifting process in which people experience a complex dialectic between an illness-in-the-foreground perspective and a wellness-in-the-foreground perspective. According to Patterson the shift between the two perspectives can take place either as a gradual process or as a result of sudden actions. Despite the fact that The Shifting Perspective Model focuses on chronically ill patients and not specifically on patients with advanced and incurable cancer, the description of the constant perspective shift between illness and wellness can be used to understand how patients who cannot look forward to being cured of their illness find themselves in a situation which is characterised by constant readjustment processes.

A third process shown in this study was Self-preservation. Self-preservation was characterised by patients on the one hand being forced to live with powerlessness that arose from a growing acknowledgement of impending death. On the other hand, the patients were able in certain situations to find the courage and strength necessary so that the powerlessness did not completely overwhelm them. Sand et al. [32] demonstrate how the efforts of 20 advanced cancer patients with different cancer diagnoses to develop useful strategies to restrain death could be symbolised as a cognitive and emotional pendulum, swinging between the extremes of life and death. While the pendulum is swinging, the informants strove to find factors that fitted their conceptual system and supported their inner balance and structure, all to keep death at a distance and preserve their links to life. Self-preservation and the coping efforts identified in relation to self-preservation can be compared to the swings of the pendulum, in that there was constant movement between finding courage and strength while also living with powerlessness.

The demonstration of the three processes: Prioritising, Downplaying and Self-preservation indicates that the patients fight an ongoing battle through specific actions and interactions to maintain or re-establish a kind of meaning in life, despite the fact that their life probably wouldn’t last much longer. From a symbolic interactional perspective [18] it is described how human beings act towards things on the basis of the meanings that the things have for them. The meanings of such things are derived from, or arise out of, the social interaction that one has with one’s fellow humans. These meanings are handled in, and modified through, an interpretive process. This understanding of the connection between action and meaning underpins how patients do not act solely to solve the many problems that crop up in their complex illness and life situation [33,34], but also act to create meaning and connection in their lives. It is thereby suggested that, apart from using problem-focused and emotion-focused coping [8,9] patients also make use of meaning-based coping. The concept “meaning-based coping” was developed by Folkman [35], and describes the role of meaning in dealing with the pressures of stressful situations, because it shows that, when people don’t succeed in solving a problem with the help of emotion-focused or problem-focused coping strategies, they might try to use meaning-based actions, which gives rise to a re-evaluation of the situation and thereby the achievement of a better connection between their outlook on the world and the actual situation. Thus it becomes possible to increase positive feelings in the midst of an otherwise very difficult situation [36]. By drawing upon Folkman’s understanding of meaning-based coping as an element of the theoretical context, Lethborg et al. [14] shows, in a study using a qualitative approach to interview 10 patients with different forms of advanced cancer, how all the patients applied meaning-based coping in order to achieve and sustain a balance between positive and negative emotional states. The positive reappraisal encouraged the patients to focus their energies and appreciate what was meaningful in their lives and thereby respond to the impact of cancer by embodying their life fully and with meaning. The same response to the impact of cancer can be found in results from this study, given that the patients attempt to act in a meaningful way in specific situations. In this way the patients create a form of an “adaptive pathway towards coherence and the sense of self” [14], which is central to meaning-based coping.

The use of grounded theory methodology, as described by Strauss and Corbin [16,17], has given rise to intense codings in the axial coding layer, which were directed to various aspects in the data material—namely context and process. Context and process can, on the one hand, be considered as two directions of analysis, which can demonstrate different theoretical dimensions in the analysis material. On the other hand the two analysis dimensions are inextricably linked. Since we put particular focus in this article on the connection between the central tendency and the three processes, it is therefore necessary to point out that coding for process took place alongside coding for context. We evaluated, however, that it is essential to show a clear marking of the identified processes, since “theory without process is missing a vital part of its story—how the action/interaction evolves” [17].

One limitation of this study is that it does not say anything about differences in coping-patterns in men and women, or in patients who live at home, in the hospital or at a hospice. A further limitation could be the small number of participants from only one area in Denmark, which means that the results cannot be generalised.

8. CONCLUSION

The purpose of the article was to identify and describe processes that from a patient perspective are significant to coping in advanced cancer patients. The findings point to how the central tendency in coping in advanced cancer patients was the patients’ struggle to be a participant in their own lives. This central tendency involved three processes: Prioritising, Downplaying and Self-preservation. Prioritising was shown to be a process where patients were active participants in relation to evaluating, prioritising and finally deciding which actions and interactions they considered constituted appropriate coping efforts in their situation. Downplaying showed how patients fought to play down the invasive influence of the illness on the lives they had built up over many years together with their relatives. Self-preservation pointed to how patients set coping efforts in motion that made it possible for them to find the courage and strength necessary to live with the powerlessness that an acknowledgement of imminent death inherently brought to bear. The discussion indicated that the three processes allowed the patients to make use of meaning-based coping efforts which increased their experience of being a participant in their own lives.

9. PERSPECTIVES

From a clinical perspective the findings can contribute to greater understanding by professionals in the clinical field of processes significant to coping in advanced cancer patients, which have been shown to come into play when coping is considered from a patient perspective. Furthermore, the results of the research project can feature in debates around how patients can be optimally supported to prioritise the activities on which they should spend their remaining strengths. This could include assessment of tools considered appropriate by the patient to pinpoint and express the goals they see as meaningful— see for example the Ph.D. Thesis written by Zoffmann [37], which focuses on as well a theory as guidelines that describes a life-skills approach called Guided Self-Determination. From a research perspective the findings can contribute to further research that investigates coping in advanced cancer patients from other perspectives, for example from the relatives’ and health professionals’ perspectives. By juxtaposing the results from such studies a detailed and multi-faceted picture of coping can be delineated.

10. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors received financial support for the research of this article from: The Danish Cancer Society, CVU University College Oeresund, The Novo Nordic Foundation, University of Southern Denmark, The Harboe Foundatio, The Family Hede Nielsens’ Foundation, and Aase and Einar Danielsen Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Hansen, S.R. (2003) Hospitalsindlagte patienters oplevede lidelse i livet med uhelbredelig kræft [Hospitalised patients’ experienced suffering in life with incurable cancer]. Bispebjerg Hospitals Forlag, Copenhagen.

- Rydahl-Hansen, S. (2005) Hospitalized patients experienced suffering in life with incurable cancer. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 19, 213-222. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00335.x

- Hald, M. (1993) Døende kræftpatienter på hospitalet [Terminally ill cancer patients in hospitals]. Kræftens Bekæmpelse, Århus.

- Lawton, J. (2000) The dying process—Patients experiences of palliative care. Routhledge, London.

- Eriksen, T. (1996) Livet med kræft—I et støtte og omsorgsperspektiv [Living with cancer—Seen from a support and care perspective]. Munksgaard, Copenhagen.

- Cassel, E.J. (1999) Diagnosing suffering: A perspective. Annals of Internal Medicine, 131, 531-534.

- Hart, B., Sainsbury. P. and Short, S. (1998) Whose is dying? A sociological critique of the “good death”. Mortality, 3, 65-77. doi:10.1080/713685884

- Lazarus, R.S. (1999) Stress and emotion—A new synthesis. Free Association Books, London.

- Lazarus, R.S. and Folkman, S. (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company, Inc., New York.

- Thomsen, T.G., Hansen, S.R. and Wagner, L. (2010) A review of potential factors relevant to coping in advanced cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19, 3410- 3426. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03154.x

- Davies, M. and Sque, M. (2002) Living on the outside looking in: A theory of living with advanced breast cancer. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 8, 583- 590.

- Houldin, A.D. and Lewis, F.M. (2006) Salvaging their normal lives: A qualitative study of patients with recently diagnosed advanced colorectal cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 33, 719-725. doi:10.1188/06.ONF.719-725

- Luoma, M.L. and Hakamies-Blomqvist, L. (2004) The meaning of quality of life in patients being treated for advanced breast cancer: A qualitative study. Psychooncology, 13, 729-739. doi:10.1002/pon.788

- Lethborg, C., Aranda, S., Bloch, S. and Kissane, D. (2006) The role of meaning in advanced cancer-integrating the constructs of assumptive world, sense of coherence and meaning-based coping. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 24, 27-42. doi:10.1300/J077v24n01_03

- Thomsen, T.G., Hansen, S.R. and Wagner, L. (2011) How to be a patient in a palliative life experience? A qualitative study to enhance knowledge about coping abilities in advanced cancer patients. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 29, 254-273. doi:10.1080/07347332.2011.563345

- Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research. SAGE Publication, Thousand Oaks.

- Corbin, J. and Strauss, A. (2008) Basics of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications, Los Angeles.

- Blumer, H. (1998) Symbolic interactionism—Perspective and method. University of California Press, Ltd., Berkeley.

- Hansen, E.J. (1984) Socialgrupper i Danmark [Social groups in Denmark]. Socialforskningsinstituttet, Copenhagen, Studie 48.

- Folstein, M.F., Fetting, J.H., Lobo, A., Niaz, U. and Capozzoli, K.D. (1984) Cognitive assessment of cancer patients. Cancer, 53, 2250-2257.

- Morse, J.M. (2007) Sampling in grounded theory. In: Bryant, A.B.D. and Charmaz, K., Eds., The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory, SAGE Publications, Los Angeles, 229-244.

- Kvale, S. and Brinkmann, S. (2009) Interviews learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publications, Los Angeles.

- Davies, E.A., Hall, S.M., Clarke, C.R., Bannon, M.P. and Hopkins, A.P. (1998) Do research interviews cause distress or interfere in management? Experience from a study of cancer patients. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 32, 406-411.

- Wilkie, P. (1997) Ethical issues in qualitative research in palliative care. Palliative Medicine, 11, 321-324. doi:10.1177/026921639701100411

- Lempert, L.B. (2007) Asking Questions of the Data: Memo Writing in the Grounded Theory Tradition. In: Bryant, A. and Charmaz, K., Eds., The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory. SAGE Publications, Los Angeles, 245-264.

- Morse, J.M., Barnett, M., Mayan, M., Olsen, K., and Spiers, J. (2002) Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11. http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/IJQM/index

- Olsen, H. (2002) Kvalitative kvaler—Kvalitative metoder og danske kvalitative interviewundersøgelsers kvalitet [Qualitative concerns—qualitative methods and quality in Danish interview studies]. Akademisk Forlag A/S, Copenhagen.

- Folkman, S. (1984) Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality Social Psychology, 46, 839-852. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.839

- Link, L.B., Robbins, L, Mancuso, C.A. and Charlson, M.E. (2005) How do cancer patients choose their coping strategies? A qualitative study. Patient Education and Counseling, 58, 96-103. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.07.007

- White, M. (2008) Kort over narrative landskaber [Maps of narrative practice]. Hans Reitzels Forlag, Copenhagen.

- Paterson, B.L. (2001) The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33, 21- 26. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00021.x

- Sand, L., Olsson, M. and Strang, P. (2009) Coping strategies in the presence of one’s own impending death from cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 37, 13-22. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.01.013

- Osse, B.H., Vernooij-Dassen, M.J., Schade, E. and Grol, R.P. (2005) The problems experienced by patients with cancer and their needs for palliative care. Supportive Care in Cancer, 13, 722-732. doi:10.1007/s00520-004-0771-6

- Wilson, K.G., Chochinov, H.M., McPherson, C.J., LeMay, K., Allard, P., Chary, S., Gagnon, P.R., Macmillan, K., De, L.M., O’Shea, F., Kuhl, D. and Fainsinger, R.L. (2007) Suffering with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 1691-1697. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6801

- Folkman, S. (1997) Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science & Medicine, 45, 1207-1221. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00040-3

- Park, C.L. and Folkman, S. (1997) Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology, 1, 115-144. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.1.2.115

- Zoffmann, V. (2004) Guided self-determination a life skills approach developed in difficult type 1 diabetes. Ph.D. Thesis, Fællestrykkeriet for Sundhedsvidenskab, University of Aarhus, Aarhus.

NOTES

*Author contributions: SRH and TGT were responsible for the study conception and design. TGT performed the data collection and the data analysis. TGT, SRH and LW made the critical revisions to the study. SR-H and LW supervised the study.

#Corresponding author.