Current Urban Studies

Vol.04 No.03(2016), Article ID:70618,26 pages

10.4236/cus.2016.43021

Governance Deficits in Dealing with the Plight of Dwellers of Hazardous Land: The Case of the Msimbazi River Valley in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Joseph Mukasa Lusugga Kironde

School of Real Estate Studies (SRES), Ardhi University, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Email: lusuggakironde@gmail.com

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: July 17, 2016; Accepted: September 13, 2016; Published: September 16, 2016

ABSTRACT

Hazardous land is given high profile in the Tanzanian National Land Policy 1995. Subsequent land laws provide for participatory procedures to declare land to be hazardous. Public authorities have over the years been concerned about the continued living on a flood-prone Msimbazi River Valley in the city of Dar es Salaam. Despite adopting carrot policies such as allocating alternative land, and stick policies including forced eviction and demolition, sections of the population have continued to live in the Valley. Research on the ways public authorities have dealt with flood-prone areas, established that legal procedures to declare Msimbazi River Valley to be hazardous or environmentally sensitive have never been taken, and are not well-known among officials. Moreover, focus has been placed on valley dwellers instead of addressing citywide flooding. Paternalism, dealing with market failure and exerting political authority are considered to be the drivers motivating the government to evict valley dwellers. It is concluded that the approach dealing with dwellers of flood- prone areas should adhere to legal provisions by, in particular, being participatory; should utilize available technology to identify, declare and demarcate hazardous land, should put this land to the badly needed greening of the city; and should address citywide flooding as a part of managing the city instead of focusing on a few individuals in a particular hazardous area.

Keywords:

Hazardous Land, Eviction, City Flooding, Governance, Climate Change

1. Introduction

In many parts of the World, governments have shown concern over people living on land where they can lose their life or get hurt, or where property can be damaged or destroyed, from happenings external to these dwellers. Authorities have thus passed policy and legislation regulating and in some cases prohibiting occupation of land that is considered to be hazardous which in many cases is occupied by low income households, although, where such land is on high-value sites, it can be occupied by high income households or put to commercial or industrial uses, as investors spend huge sums on one form or other of reclamation. There are cases of confrontation between public authorities and land-users over the continued occupation of hazardous land, but there are also cases where governments turn a blind eye to this phenomenon. This paper, based on research carried out during the latter part of 2015 (Kironde, 2016) , examines the attitude of the Government to those occupying land in river valleys liable to flooding, citing the case of the Msimbazi River in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

2. Hazard, Hazard Land, Disaster and Urban Flooding

Hazard is conceived as a potentially damaging physical event, phenomenon or human activity, which may cause the loss of life or injury, property-damage, social and economic disruption or environmental degradation to the extent of leading to a disaster. Flooding, fire outbreak, cholera strike, tuberculosis (TB) outbreak, landslide, hurricane, thunderstorm, earthquakes to mention but a few, are good examples of potential physical phenomena/events or human activity, which may cause such events. The potentiality of these physical phenomena/events or man-made activities to cause negative impacts is what makes them qualify as being regarded as hazards. A hazard, therefore, refers to any natural or human-made phenomenon/event that when exposed to vulnerable elements may cause loss of life or damage to property and environment (AU- NEPAD et al., 2004) .

A disaster refers to a remarkable occurrence (phenomenon) in which a significant number of people, properties and environments suffer severe damage, disrupting the livelihood system; thus making the affected society/population unable to cope by using its own resources (AU-NEPAD et al., 2004).

Hazardous land, whose conceptualisation may include environmentally fragile land, is land where a natural hazard exists. It includes flood plains and steep slopes; or land subject to high levels of pollution.

Flooding afflicts many urban households in the world, but particularly so, in African cities. Douglas et al. (2008) identify four types of flooding that is: localized flooding due to inadequate drainage; flooding from small streams whose catchment area lie almost entirely within built up areas; flooding from major rivers on whose banks the major towns and cities are built; and, coastal flooding from the sea, or from a combination of high tides and high river flows from inland. The first two types are common in the city of Dar es Salaam even in central and high income areas.

There is considerable literature on urban flooding which presents dwellers of land liable to flooding to be mainly those in low income categories, and who adopt various coping strategies to the danger facing them (Pharoah, 2014; Fogwe and Asue, 2016; Sakijege et al., 2014; Douglas et al., 2008) . Many governments have legislation enabling them to zone land liable to flooding so that it is not constructed upon, or it is used in such a way that danger to human life and property is minimised. However there is also observation that in many cases especially where land is occupied by low income households, governments do nothing about these areas.

Sakijege et al. (2012: pp. 5-6) identify risks associated with flooding to be: water and air pollution, diseases, water-logging and blocked accessibility. One must add loss of life, injury, loss or damage to property, forced, if temporary, displacement and many others.

Concern about living on hazard land can be about the plight of the poor or about the rich developing land which is environmentally sensitive such as mangrove forests, or delicate beaches to the detriment of society in general. Such development may directly affect other people including increasing flooding. It was observed, in the case of Kampala that causes of flooding in some areas included: “expansion of commercial property and industrial developments on reclaimed wetlands where floodwater used to drain” and “the discriminatory enforcement of wetlands policies that allow the rich to block natural drainage areas greatly disadvantaging the poor through consequent flooding”. (Douglas et al. (2008: p. 195) .

Similar sentiments have been expressed from Dar es Salaam. Victor et al. (2008: p. 26) report respondents from Bonde la Mpunga, a notorious flood-prone area, saying the following: “We have complained to the authority about flooding of the area because the natural drainage was blocked by a rich man’s building erected in its middle. No actions have been taken so far, and the building is now complete. Come this rainy season, we do not know what would be our fate”. Indeed the affected community felt that the authorities were unwilling to provide basic services to their area including drainage.

Concern about occupying hazard land may change with time. In Dar es Salaam in the 1980s, it was the rich who were being accused of taking over and privatizing environmentally sensitive land. Kironde (1995) relates the struggles between the environmental lobby and developers over the private development of the beaches of Dar es Salaam. By and large, the environmentalists lost the battle. The current concern, highlighted most after incidences of flooding and loss of life, is about the poor living in flood-prone areas.

While there has been ample coverage about the coping strategies of people living in flood-prone areas, this paper identified a need to look at the legal provisions empowering public authorities to deal with hazardous areas and the extent to which these are implemented to avert or minimize loss or injury for both people and property.

3. Policy and Legal Provisions for Addressing Hazardous Land in Tanzania

Among the many issues that the National Land Policy 1995 (NLP) addressed was hazardous (as well as what was called: “sensitive”) land which was supposed to be protected (URT, 1995) . Section 7.9 of the NLP talks of “Protection of Hazard Lands”, noting:

There is increasing encroachment on hazard lands for housing and other developments in towns. Such areas including river valleys, areas of steep slopes, mangrove swamps, marshlands are being intensively developed. Apart from the dangers they pose to life and property, such development contribute to land degradation, pollution and other forms of environmental destruction. (p. 38)

The Policy Statement going with the above observations stated (Section 7.9.1):

Measures will be taken to prevent building on hazard lands and on all fragile environments. Hazard lands should be developed for public uses benefitting the local community. (p. 39)

Measures taken included putting sections in both the Land Act 1999 (LA) and Village Land Act 1999 (VLA), defining and providing what to do about hazardous land; and how, in particular, to identify and demarcate such land; and declaring and protecting it.

The LA makes it the duty of the Minister for Lands to declare any areas that he deems to be hazardous. Section 7 of the LA lists types of land which can be considered to be hazardous to include: mangrove swamps and coral reefs, wetlands and offshore islands; land within sixty meters of a river bank, shoreline on an inland lake, beach or coast; land on steep slopes and land “specified by the appropriate authority as land which should not be developed on account of its fragile nature or of its environmental significance”.

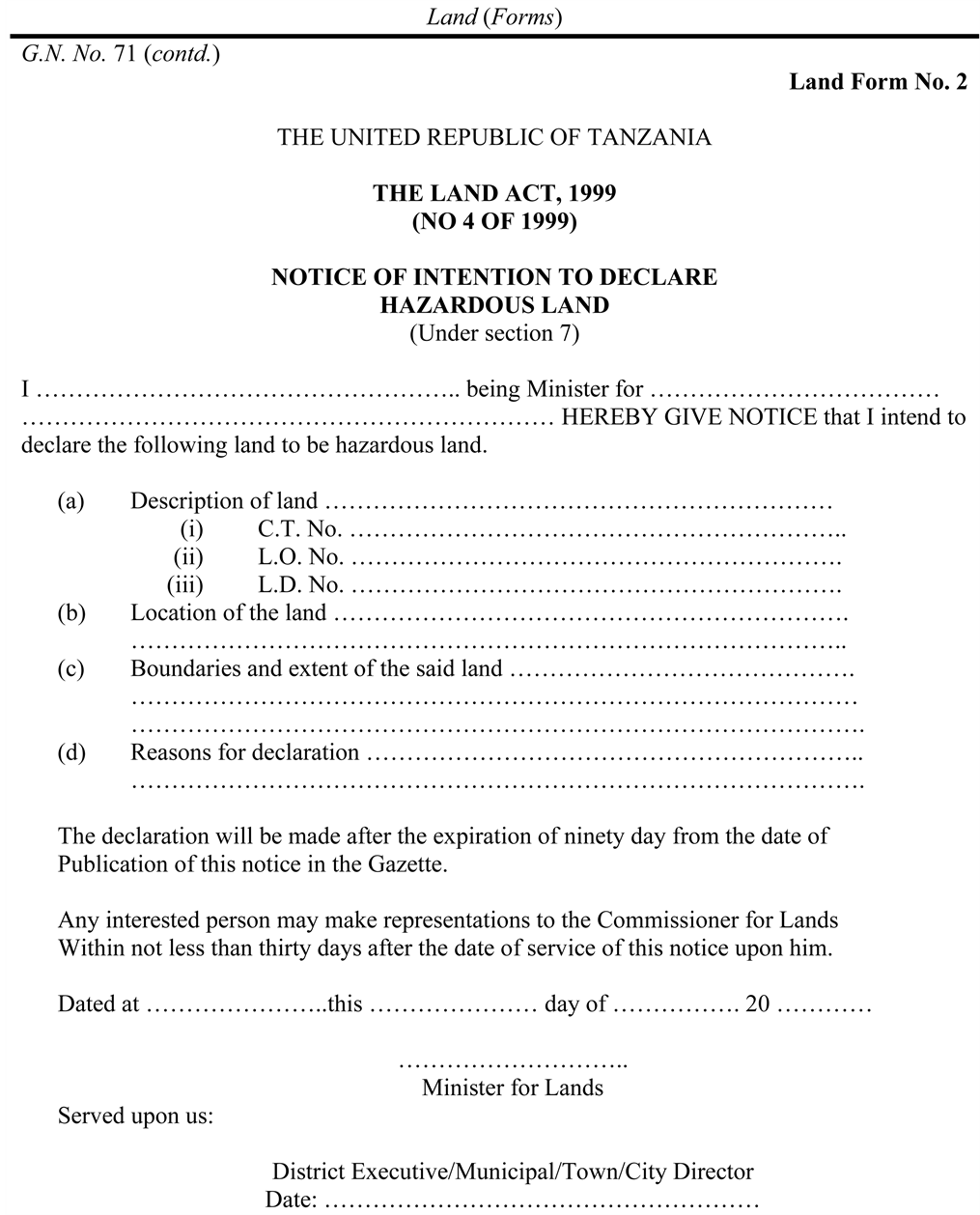

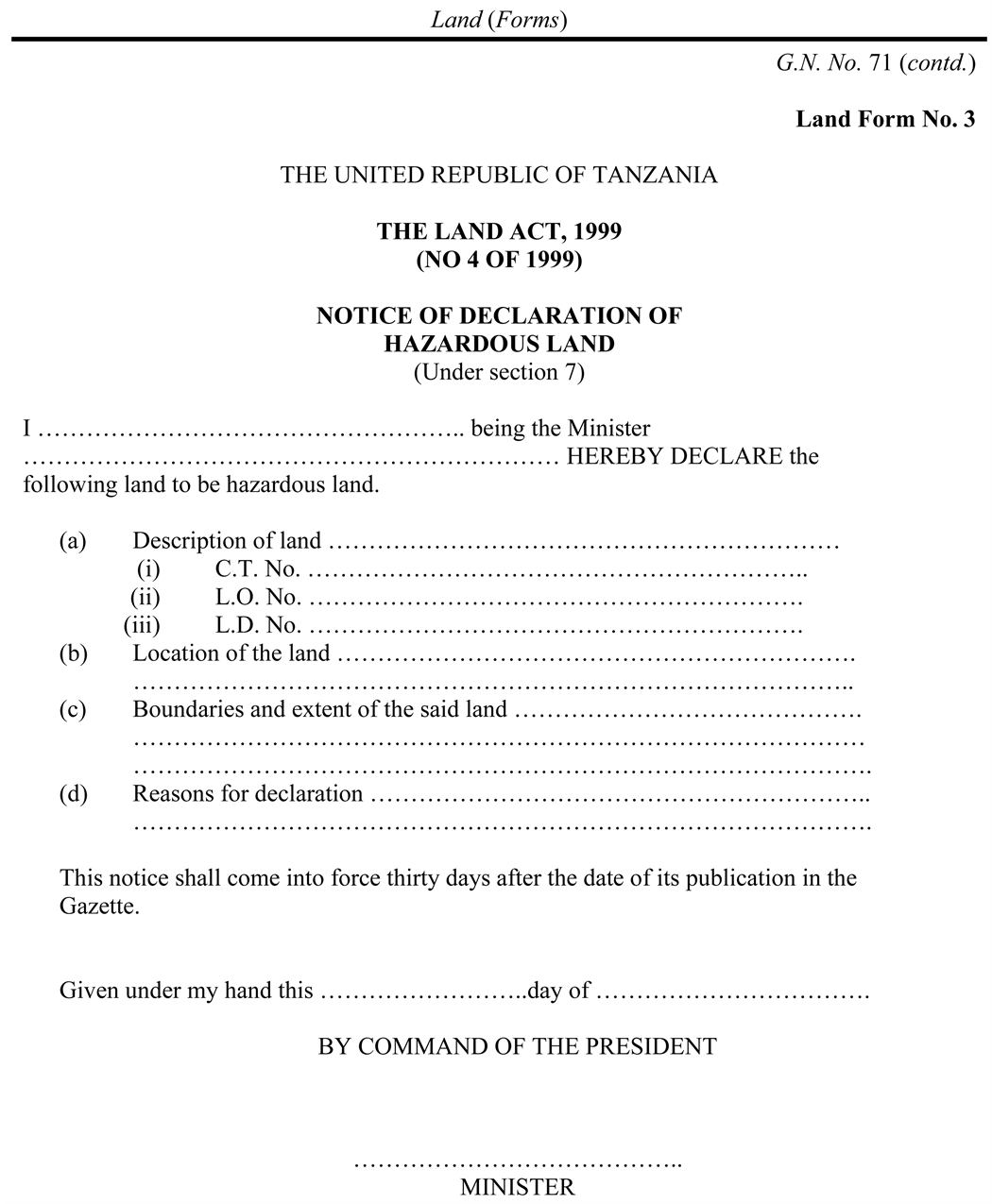

The procedure to declare land to be hazardous is summarized in Table 1.

The onus of declaring an area to be hazardous land therefore lies on the Minister for Lands, on the advice of the Commissioner for Lands. This study sought to find out if this procedure has been followed anywhere in the country.

4. Conceptual Framework

Three lines of thought can be advanced positioning the responsibility of public authorities with regard to dwellers of hazardous land. One is that flood-prone areas dwellers are endangering their life and property; and that they may not know what is good for them. This is Parternalism (or parentalism) which is the behaviour by an organization or state which limits some person or group's liberty or autonomy for what is presumed to be that person’s or group’s own good.

The other approach is from economic theory which justifies the intervention of public authorities in land markets on both economic (dealing with market failure) and social grounds (e.g. equity) and has been widely discussed in the literature (Cheshire and Vermulen, 2009) . Among the many reasons justifying this intervention are: dealing with externalities, providing goods and services with public good characteristics, and addressing issues of equity and income redistribution. Regulating or preventing the use of flood-prone areas is a way to deal with externalities.

It can be argued that, the public, over and above the individual, suffers when its members are adversely affected by floods. Valley dwellers who are forced to leave their houses as a result of floods, impose a burden on the whole society which has to shelter them, feed them or get them treated. Moreover, floods can be a source of epidemics in-

Table 1. Procedures to declare land to be hazardous. Source: URT (1999) .

cluding cholera which affect valley and non-valley dwellers alike. Valley dwellers may have limited knowledge of what may happen to their area in the future, if nothing has happened for so many years. Public authorities may have the history, the data and other information that indicates that such an area can, one of these days, suffer from floods.

In the case of the study area, the concepts of paternalism and externalities may not be an adequate explanation since public authorities do not seem show equal concern for all areas suffering from flooding. Their concern is selective. The Msimbazi River Valley has received most attention over the years compared to other flood-prone areas in the City. Indeed, there are cases, where flooding is a result of public action such as allocating down stream wetlands for development into real estate, as is the case with Msasani Bonde la Mpunga (Kiunsi et al., 2009) ; or where civil works carried out elsewhere divert or concentrate run off water to areas that were not subject to flooding before as in the case of Keko (Sakijege et al., 2014) .

It is proposed that another driver motivating public authorities to declare some parts of the city hazardous and to try to evict, or actually evict the occupiers is the exertion of political authority. Over the past 30 years the Government has ordered dwellers of Msimbazi Valley especially on both sides of Morogoro road (Jangwani) to move, to no avail, despite the use of both stick and carrot policies approaches. At one time a Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner went to the Jangwani area of and physically demolished a number of houses, but this did not make others leave the place. Floods have caused only temporary movement from the area but dwellers have trickled back soon after the floods had subsided.

The Jangwani area of the Msimbazi Valley is very conspicuous. Open defiance of public authority as demonstrated by the valley dwellers may be an added reason why the Government is always requiring dwellers to vacate.

Thus we see at least three concepts guiding the attitude of policy makers towards the valley dwellers of Msimbazi River: Paternalism, dealing with externalities and exerting public authority (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptualisation of Public Authorities’ attitudes towards flood-prone areas dwellers.

Jangwani valley dwellers themselves have always expressed another motive; that their land is earmarked for allocation to some developer.

5. Research Methodology

5.1. Justification for Research

This paper is based on research that was carried out over the Msimbazi river valley area in Dar es Salaam in the latter part of 2015 and was justified on four grounds. One, the National Land Policy had just turned 20 and it was time to evaluate whether its vision of dealing with hazardous land had been achieved. Two, the continued of loss and property affecting people living in flood-prone areas called for research on the problem.

Three, in December 2015 a major demolition exercise was undertaken involving properties in the Msimbazi River Valley and its tributaries. By the time the courts put a moratorium to this demolition in January 2016, hundreds of property worth millions and hundreds of residents had been rendered homeless, the main argument for this demolition being that these people were occupying hazardous land. According to newspaper reports, by time the exercise was suspended 700 houses already been demolished; 8,000 houses were earmarked for demolition and 15,000 had already been marked with an X, meaning they were to be demolished1. Some 200,000 people were left homeless after demolitions2.

Lastly, the continued warnings by the MET of impending heavy rains as a result of climate change and El Nino meant that there was need for preparedness.

5.2. Research Methodology

Objectives of the study included: establishing the legal and practical process of declaring an area to be hazardous; finding out which areas had been declared hazard lands and what their status was in terms of protection and development; finding out why many areas that are hazardous land have not been so declared; learning from those occupying hazard lands of their reasons for doing so; establishing whether public authorities have a regular audit of land that is hazard or potential hazard; finding out if land that is considered hazard can be allocated by public authorities; and proposing a way forward that would lead to the realization of the aspirations of the National Land Policy and the Land (and other sectors’) legislation as far as hazardous land is concerned, such as developing it for public purposes

Besides, the study sought to establish whether there was a register or some other official document showing declared hazardous land in Tanzania; which authority had the powers to declare land to be hazardous and how they discharged their duties; bottlenecks in declaring an area to be hazard and in protecting such land from occupation; and, options open to public authorities once potential hazard land has been occupied.

Findings are based on extensive reading of documents including research reports, published and unpublished papers, acts of Parliament, newspaper articles, numerous Government Gazettes from 2002 to the present and so on. Relevant documents kept in the libraries of the Ministry of Lands, Civil Service Documentation Centre and Attorney General’s Chambers, especially the Government Gazettes and the Government Bookshop were read.

Aerial photographs over Dar es Salaam in general, and Msimbazi Valley in particular, were procured and, using GIS technology, tracing was made of the 60-meter buffer zone along the river Msimbazi to establish the extend of encroachment.

Formal and informal interviews were carried out with officials of the Ministry of Lands, particularly Ministerial lawyers, officials from Commissioner for Lands; Directorate of Physical Planning; Ilala and Kinondoni Municipal Councils; NEMC; Dar es Salaam Regional Offices; Ardhi University; and the Centre for Community Initiatives (CCI).

The mass media also provided valuable information which has formed inputs for this study especially in the wake of mass demolitions that took place in Msimbazi Valley and Mkwajuni in December 2015 and January 2016.

Physical visits for participant observations and interviews with local leaders and demolition victims were made to Msimbazi and Mkwajuni Valleys before and after it had rained heavily; and after the December/January demolitions.

6. Findings

6.1. Msimbazi River Valley, the Case Study

Msimbazi River (Figure 2) is the second longest river within Dar Salaam originating in Pugu Hills and discharging into the Indian Ocean. It has a length of around 32 km and a catchment area of 289 m2. Its important tributaries include rivers Sinza (Ng’ombe), Luhanga, Ubungo, and Kinyerezi. It and its tributaries have attracted valley living which historically began as land being used for agriculture before getting converted into low and medium cost residences.

Since the study sought to establish the extent of encroachment into the 60 m buffer zone. Using GIS-based calculations it was established as shown in Table 2.

Thus 19% of the land within the 60m buffer zone is built upon. However, the Valley is much wider than the 60 meters envisaged in the law and parts of this valley which are flood prone are built upon mainly by low income households and in many cases, industries and institutions. The 60m buffer zone is not related to how flood-prone an area is (Figure 3).

Table 2. Extent of encroachment into the 60 meter buffer zone over the Msimbazi River.

Source: Calculated by the researcher on the basis of 2012 Population and Housing Census aerial photographs.

Figure 2. Msimbazi River and its main tributaries.

Figure 3. The mouth of River Msimbazi and the surviving mangrove forest. The informal area in the middle to the rights is outside the buffer zone but is flood prone.

Construction in the valley in general and within the buffer zone includes residences industries and institutions (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Industrial uses in the Msimbazi Valley and in the Buffer Zone.

6.2. Lack of a Directory of Legal Instruments Declaring Areas to Be Hazardous Land

From the Ministry of Lands, it was established that there was no directory of the Government Notices (GN) prepared by the Ministry concerning various aspects of land use and administration. Had this directory existed, it would have been relatively easy to identify which land has been declared hazardous, or environmentally sensitive.

Subsequently, a search was made through all Government Gazettes published since 2001 when the Land Act became operative. There were several GNs published under the Town and Country Planning and Land Acquisition legislations but these talked about the redevelopment of some urban areas not on hazardous land.

Only one GN, No. 348 of 19/2/2002, made public the Minister of Land’s intention to declare hazardous land over a piece of land with CT No. 39597, which apparently had been allocated to a certain religious community for the development of a sports ground. No evidence could be found to show that the Minister went ahead and declared the said land to be a hazardous area.

The other found GN was No. 227 published on 05/08/2011 under the Urban Planning Act 2007and titled “Urban Planning (Msimbazi River Area) (Special Planning Area) Notice, 2011”. It referred to: “All the area of land delineated in red in the Msimbazi River Valley proposed Park, commencing from Surrender (sic! Selander) Bridge to Vingunguti”.

A detailed planning scheme for the area was to be prepared and deposited with the Director of Urban Planning (DUD), Ministry of Lands, as well as with the Municipalities of Ilala and Kinondoni. It was established that such a scheme had not been prepared since the Notice got out in 2011. Only a preliminary study had been carried out.

Under section 24 of the Urban Planning Act (URT, 2007) :

24.-(1) The Director may, by notice published in the Gazette and after consultation with the relevant planning authority, declare any area with unique development, potential or problems, as a special planning area for the purpose of preparation by the relevant planning authority of a planning scheme irrespective of whether such area lies within a planning area or not.

This is what was done with respect to the Msimbazi Valley was declared a Special Planning Area in 2011.

Section 25 refers to hazardous land:

25. A declaration of hazardous land by the President under the Land Act shall be deemed to be a declaration of a planning area for the purpose of preparation of detailed planning scheme under this Act.

The Urban Planning Act reaffirms therefore that powers to declare land to be hazardous are within the Land Act.

In replying to a question whether Msimbazi River Valley has ever been declared a hazardous land, one official referred to the 2011 Notice of declaring Msimbazi a Special Planning Area.

It is held here that declaring an area to be a special planning area does not mean that it is hazardous. Therefore the need to declare Msimbazi Valley a hazardous area, on the grounds of its being prone to regular flooding, is still urgent despite the existence of other legislation.

We could not find any GN declaring Msimbazi to be an environmentally sensitive area either under the Environment Management Act 2004, which law provides for consultations with concerned communities and other stakeholders.

Besides not finding any legal instruments declaring Msimbazi valley, or any land for that matter, to be hazardous land, it was established that there were no consultations or dialogue with land users or those neighbouring areas considered hazardous.

Our interviews with those who were affected by the demolitions established that land owners and occupiers have never been served with a notice of the intention to declare their land hazardous, let alone the notice that land has been declared to be hazardous land.

Indeed, after the government put a moratorium on the demolition of properties n January 2016 to give owners a chance to demolish themselves in order to salvage assets from their property, many said they could not do that since they did not know whether their properties were within the boundaries of hazardous land or not. On realizing this, the government, as an after thought, started putting marks on buildings earmarked for demolition, before the court put a stop to the whole exercise. By then 353 houses out of the earmarked 8000 had been demolished.

6.3. Conflicts in Institutional Responsibility and Actions

Msimbazi Valley has attracted many authorities each showing concern and each purporting to have authority over the area. These have included the President, Regional and District authorities, the Ministry for Lands, Dar es Salaam Municipalities and lately the National Environmental Management Council (NEMC).

Way back in 2011, after floods that left at least 49 people dead, the President ordered that flood victims in Dar es Salaam be allocated plots in Mabwepande, and be given assistance in form of building materials.

In 2012 the Minister for Lands informed of the preparation, by her Ministry in collaboration with the Municipalities of Ilala and Kinondoni, of a detailed land use plan for the Msimbazi River Valley which was being declared to be a Special Planning Area.

In May 2015 after an episode of flooding, the President once again urged all valley dwellers to relocate, promising to provide new plots to those willing to vacate. At the same time, the Kinondoni District Commissioner, said that in Mkwajuni area near River Ng’ombe (Sinza) there were 680 households and 976 families, all of whom were affected by floods. “We had plans to relocate them but only 102 households moved out of the area while others were resistant”3.

In December 2015 the Minister for Lands said Msimbazi River Valley was a high-risk area and that the government had allocated it for construction of a public city parking. He said construction of human settlement and other commercial structures is contrary to the rules of Urban Planning Act of 2007 and the Environmental Management Act No. 4 of 2004. The Minister fell short of pointing out that it was his Ministry that was responsible for the declaration of the areas to be a hazardous land. Moreover it came to light that some of those whose houses were demolished had Certificates of Title issued by the Ministry of Lands.

Again in December 2015, NEMC came in strong spearheading the demolition of houses in river valleys under Environmental Management Law. Up to then, the Msimbazi River Valley had attracted little attention from NEMC but this time they were at the forefront. This raises questions. The timing was when peoples’ representatives (Councilors and Mayors) had yet to take office. Secondly who was footing the bill of property demolitions? The high cost of demolition had, in 2011, thwarted efforts to demolish houses of those who had been allocated alternative land but were suspected of going back to occupy or renting out their valley properties. NEMC acted without consulting valley dwellers, as required by the law.

The Jangwani dwellers and others along the Msimbazi River have for years been required by the government to relocate from the low-lying areas, all in vain. The latest call was from Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner in April 2016, warning Jangwani residents of the impeding heavy rains. Residents however blamed civil works over the Msimbazi which had reduced the water flow and made flooding worse4.

Laws related to land tenure (Land Act 1999), Land Use Planning (Urban Planning Act 2007) and to the Environment (Environmental Management Act 2004) have all been applied to Msimbazi Valley, creating confusion as to which was which.

6.4. Public Authorities Acting in a Contradictory Manner

The study established that while there is unanimous agreement among public officials that Msimbazi River Valley was hazardous as well as environmentally sensitive, it is private individuals who have been declared illegal occupiers (even where some have certificates of title). In what seems to be a contradiction, the government allowed the construction of a large BRT bus stop which is now acting as a barrier to the smooth flow of the water along the Msimbazi River and making flooding worse.

In a rather interesting twist of events, this bus stand has on a number of occasions served as temporary shelter when the floods in the valley necessitated temporary abandonment of water filled homes.

Moreover, many of the properties constructed “illegally” in the valleys have public services such as electricity, and water; and property owners pay property tax. Some have residential licences and at least 20 of those demolished properties carried certificates of title. All this is contradictory behavior on the part of the public authorities creating confusion in the whole saga of valley living.

6.5. Political Support for Valley Dwellers

The study found that valley dwellers had support from their national and local representatives (MPs and Councilors). The December 2015 demolitions were suspended on the initiative of a local MP who spearheaded a court case to ensure that property owners were heard before their properties were demolished.

Indeed it was interesting to see the Minister for Environment visiting the victims of demolitions carried out by his Ministry, to console them. The Minister promised assistance in form of making sure pupils whose homes were demolished went to school.

6.6. Little or No Consultation with Valley Dwellers or Local Government Leaders

The study found that there all along, there has been little or no consultation with valley dwellers as to their fate. It is a fiat. They must move; the area is dangerous: How, when, to where? These were not questions for discussion. There was no socio-economic evaluation of the valley dwellers and what made them to prefer living in these areas. Likewise local government leaders and peoples representatives (MPs and Councilors) complained that the central government never consulted them, nor warned them of the impeding demolitions

6.7. Lack of Sympathy for Valley Dwellers

The study found that save for representative politicians and NGOs like CCI, there was little sympathy from the public including officials and academicians for valley dwellers. To some extent, the dwellers were the victims of a public that wanted tough action from the (new) government. On the other hand there were generalizations, unsupported by data, that these people had been allocated plots in 2011, which were assumed to have been either sold, or abandoned in favour of valley living.

It is true that some flood victims of 2011 were given plots in Mabwepande. Some 1004 plots were allocated, meant to cater for all the flood victims of Dar es Salaam. This excluded tenants and was but a drop in the ocean considering the number of valley- dwellers which ran into tens of thousands. The President also promised those who suffered from the May 2015 floods that they would get alternative plots. That, some of the victims argued, had not been fulfilled5. Thus, the argument that valley dwellers had all been allocated alternative land is a distortion of the facts6.

Valley dwellers were considered stubborn who deserved no sympathy. However, the fact that after the demolitions the victims remained marooned on the rubble of their houses suffering come rain come shine suggested that they had nowhere else to go (Figure 5).

6.8. Msimbazi River Valley Gets Flooded Seasonally but to the Dwellers, the Benefits Outweigh the Risks

The study established without doubt that the Msimbazi River Valley floods occasionally

Figure 5. No where to go. Valley dwellers make makeshift shelter after demolitions. Source: Daily News, January 2016.

during the rainy seasons. In some years (e.g. 2011) floods are severe and this may be linked to the effects of climate change. In some years light or no floods are suffered.

Our interviews supported by a number of other studies (e.g. Ngware, 2003 ) indicated that people who live in these hazardous areas are aware of the dangers facing them but do so because land is (or was) easy, and cheap to acquire; that for tenants rents were low; and that accessibility to the city center was very good and cheap. Moreover livelihood activities could be undertaken either within the settlement or around it, given the high population densities. As for floods, many had coping strategies.

6.9. Jangwani-Mkwajuni Seem to Be Selectively Targeted

Over the years, Jangwani Valley (of the Msimbazi River), and recently, Mkwajuni have been the target of public authorities as far as valley living is concerned. Valley dwellers elsewhere, or indeed non-valley dwellers who nevertheless suffer regular disasters from floods, are not as pointed a finger at, as have been those living in the Jangwani and Mkwajuni areas. It is suggested that this is because these latter areas are on locations that are very conspicuous to users of highways like Morogoro Road and Kawawa Road. They are an eye sore and also represent defiance to authority.

6.10. Floods and Disasters in Jangwani Valley Are Not Related to Those Elsewhere in the City

Dar es Salaam suffers regularly from flooding even after a short downpour, but it is amazing how flooding elsewhere is ignored when that of Jangwani is highlighted. In an open letter to the Ministers for Lands and Environment, reacting to the December 2015 demolitions of properties in the area, a renown businessman had this to say:

Quite a big fuss has been made of the frequent floods in our cities as the main reason behind the most recent Government action. However, while flooding affects the central business district of Dar es Salaam just as badly, city and ministry officials choose only to react to flooding in the Msimbazi and Jangwani valleys while turning a blind eye to such flooding hot spots as Bibi Titi Road near the Morogoro Rd crossing, Ohio Street near ATC House and Works Ministry headquarters at Holland House, Ocean Road, Ghana Avenue and others where flooding can occur after hardly five minutes of rain. Now we know that most of the flooding in the CBD is caused by the blocked storm water drainage system that has not been expanded to match the needs of a fast growing metropolis over the years. And the flooding in the Jangwani valley is not so much caused by the valley residents as it is by the millions of tones of garbage that are thrown into the river by residents miles away upstream of the Msimbazi. When the government insists that this problem will be solved merely by relocating the Jangwani Valley residents to other places, it gives rise to the growing suspicion amongst the population that the exercise is not based on a correct and thorough analysis of the causes and its outcome may therefore not be sustainable even in the near term (Mufuruki, 2016) (Figure 6).

In May 2015 there were floods in many parts of Dar es Salaam prompting the President to order the unblocking or construction of drains in areas such as Boko, yet the focus has always been on Jangwani. The problem of flooding affects the whole city and is a reflection of how the city is managed.

Figure 6. Floods in the high income Upanga area in Dar es Salaam. (Photo by Kironde, 2008).

6.11. Bottlenecks in Declaring Areas to Be Hazard Land

The study found that there have been no efforts to identify and declare hazardous land in many settlements, as the National Land Policy envisaged and as the Land Act legislates for. Moreover, there is this lacuna in the law as to who should identify that land in the first place. It may be assumed that it is the local governments, but they have no incentive or resources to do so. There are also costs and technical expertise implications.

Besides what may seem hazardous land to some authority may not look the same to another. What is hazardous today may not be so tomorrow. Improvement in drainage, for example, can minimize flooding thus make land that may seem to be dangerous to occupy, relatively safe. Local authorities who are weighed down by the pressure to manage rapid urbanisation do not want to expend resources fighting citizens who feel they are able to live on land that is considered hazardous.

Indeed this could be the reason why governments, in the light of their failure to declare hazardous land wherever it may be, concentrate on an area which they know every body considers to be hazardous.

Lack of political will, limited resources and lack of expertise, as well as the fluidity of the concept of hazardous land itself, have been bottlenecks preventing the large scale identification and declaration of many areas to hazardous land.

6.12. Protecting Assumed Hazardous Land from Occupation

The study found that there are no measures to protect land assumed to be hazardous from occupation. Just as public authorities are failing to control the growth of informal settlements elsewhere, they are powerless when it comes to protecting hazardous land. Flooding seems to give public authorities strong reasons to want dwellers in such areas to move, although the movement into low-lying flood prone areas is usually an extension of unplanned and informal areas slightly up the valleys.

6.13. Hazard Land Not Given the Significance Envisaged in National Land Policy and Land Laws

The NLP and the subsequent land laws accorded hazard high importance. However, this was not followed up in action. We could not find that there was an officer dedicated to address issues of hazardous land within the Ministry or within the Dar es Salaam Municipalities. There is no mention of hazardous land in SPILL I (URT, 2005) . The Ministry focused its attention to land formalization, improving land information, decentralisation, village mapping, provision of new plots, dispute resolution and so on but there was little on hazardous land. In fact it appears that hazardous land is considered to be part of town planning and becomes an issue when floods occurred.

However, there is mention of hazard land in SPILL II (URT, 2013) which envisages an organized approach to dealing with hazardous land. However, there does not seem to be much activity in implementing SPILL since was prepared in 2013. There is no mention of hazardous land in the Budget Speeches of the Minister for Lands for the financial years 2014/15 and 2015/16 (URT, 2014, 2015) .

7. Discussions

The way public authorities deal with hazardous land in Tanzania depicts governance deficits. The law has set out a clear procedure of identifying and declaring land to be hazardous. Public authorities especially when there has been a spite of flooding rush to move people from flood prone areas. This action is usually augmented by the doom predicted from the MET people of impeding floods, and of calls for those living in valleys to move. Rarely do MET people call on authorities to institute, maintain or unblock drains to prevent or minimize flooding.

The Land and Environmental laws put down very participatory procedures to declare land to be hazardous or environmentally sensitive. There is little evidence that officials contemplate using such procedures. Whenever they address flood-prone areas, it is a case of confrontation not dialogue. The conditions making people live in flood-prone areas, which are part and parcel of the dynamics of urban survival in a situation of poverty, are rarely considered. Thus the course of action taken has in part been unlawful and in most cases, unsuccessful.

Moreover, authorities have been acting in a contradictory manner with regard to hazard land, without a clear indication as to which of the public institutions is responsible for what aspect of addressing hazardous land.

It could be said, besides, that non-identification and declaration of hazardous land is part of a bigger picture of limited implementation of NLP and Land laws. The little achievements realized in this sector have been where external assistance has been forthcoming. It is also part of lack of a wider framework to manage urban areas.

Further governance deficits include non-consultation with valley dwellers, some of whom had liven in the area for over 20 years (CCI, 2016) their local governments and their representatives; lack of transparency in terms of for example publishing who was allocated land and who was not; and implementing the eviction from the central government level without involving local governments. Seven months after the December 2015 demolitions, neither the victims who have since constructed shackles on their former plots, nor local government leaders know what the next move by the government is.

8. Recommendations

In view of the findings presented above, the study comes up with a number of recommendations:

8.1. Define Critical Hazardous Areas Adhering to Legal Procedures

Identification and declaration of hazardous land is urgent in urban areas given the disasters that can come from climate change and the resultant flooding. The continued and growing pressure on all available land from rapid urbanization and poverty means that if no urgent action is taken more and more valleys are going to be occupied. Technology, especially the use of GIS and satellite pictures, can be used to identify city wide valleys and other lands liable to flooding (or to other hazards like landslides). There could be a time line to demarcate these and follow the provision of the law to declare them hazardous land and get them protected or quickly planned into other uses such as botanical gardens. This does not have to wait to have a city-wide land use plan such as a master plan.

Dar es Salaam has regular experience with annual flooding and loss of life and property and this should not be left to continue. As it may not be possible to declare as hazardous all the areas that may seem to be so, it may be possible to declare those that are critical. In such a case however, the law must be followed. One clear advantage of adhering to the law is that it provides for consultation with communities around such areas.

Where the declared hazardous area is already occupied, public authorities should strike an agreement with the occupiers, when to move and to where, taking into consideration their requirements, like compensation alternative land and resettlement.

The areas declared to be hazardous need to be put to known uses and not just left vacant as this is likely to attract new occupiers to take the areas, or old occupiers to retake the area.

Once declared hazardous, areas should be conspicuously demarcated, as is the case with road reserves and way leaves for electricity transmission lines. It needs to be emphasized that hazard land is declared by command of the President, therefore its importance should not be under estimated.

8.2. Consider Hazardous Land in Terms of Greening the City

Land may be hazardous for human occupation but it may be very good for greening the city in terms of botanical gardens and nature parks. At one time or the other, this has been the idea of the City of Dar es Salaam with regard to the Msimbazi Valley. However, nothing has been implemented and plans for the area keep on changing. The current Minister for Lands talks of the Valley being converted into a parking area.

It is recommended strongly that in view of the current global concern with climate change, and in view of the need to create livable cities, river valleys within urban areas should be converted into urban botanical forests for the benefit of city residents.

Efforts to keep Msimbazi Valley from buildings need to be intensified by proper marking of the area and declaring it a hazardous land following the procedures put into the law which includes extensive community consultations. Dar es Salaam lacks public open spaces and botanical gardens and Msimbazi would be one such suitable candidate. It will offer a breathing area for the high density occupants of Kariakoo and Magomeni Kigogo etc as well as support the current global drive to deal with global warming.

8.3. Hazardous Land Should Be Conceived as Part of a City-Wide Land Use Framework

Over the years public authorities have shown concern about the continued occupation of the Msimbazi Valley especially at the Jangwani area. Illegality, and risk to life and property have been put forward justifying the calls for people to vacate that area. However, the same concern has not been shown over occupation of valley land along the rest of the length of the Msimbazi; along other river valleys and other low lying areas

Besides, this area has been considered in isolation and not in a city-wide land use framework. Not only would this indicate other hazardous lands, it would also show where land is available for occupation

Those living in what has been conceived as valleys in Dar es Salaam, have always been admonished especially when rains are approaching. However, valley land should not be considered in isolation of the overall city land use framework.

It is therefore recommended that Dar es Salaam and other urban areas in the country need to have an overall land use framework guiding urban development7. This should not be equated to the highly technical and expensive master plans.

A city-wide land use plan can be developed using local experts, working hand in hand with city residents. It must be a peoples’ city land use plan. This will, as one of its tenets, identify areas that may be liable to flooding and these could be put to the proposed urban forests or botanical gardens.

8.4. Debate and Agree on What Hazardous Land Is and How It Should Be Demarcated

Various concepts are used in the law to depict what is potentially, hazardous land. These however need further debating and clarification. For example there is this general statement that hazardous land includes land within 60 m of the river bank. There is need for having practical definitions of what might constitute a hazardous area instead of the general “60 meters from a river bank”. What should be defined as a river? Dar es Salaam has over 25 rivers and many other rivulets and streams. It is not practical to delineate 60 m. buffer zone for all of these rivers. If the 60 meter buffer was applied to them all, there would be no room for construction. At the same time, hazard land may be extending to beyond the 60 metres. That is why the law requires that before an area is declared to be hazardous, there must expert opinion and consultation with the various stakeholders.

8.5. The Disaster That Jangwani Poses Should Not Be Considered in Isolation

The disaster that occurs at Jangwani Valley after it rains heavily is serious and in 2011 at least 49 people died, but these were not all from Jangwani. Many low-lying parts of the City get flooded but it is the Jangwani valley that bears the brunt of the wrath of the authorities. Moreover there are many city areas that get flooded as a result of construction blocking natural drains; and lack or poor maintenance of, storm water drains.

There must therefore be city-wide disaster mapping. The Msimbazi Valley will be only one of many areas that can be affected by disaster. Any remedial measures will therefore take into consideration many more areas.

8.6. Institutional Coordination and Legal Harmonisation

Addressing the Msimbazi flooding concern has seen various actors play important roles which sometimes contradict. It is recommended that there should be institutional and legal harmonization. This area need not be one where every authority wants to exert its muscle.

Chief actors should be the Municipal authorities, especially the authorized land officers, with support from national authorities such as the Ministry of Lands and the Ministry responsible for environment. Capacity needs to be built within municipal authorities in order that they may be able to address issues of flooding and local disasters.

8.7. Capacity Building within the Office of the Commissioner for Lands

Declaration of hazardous land is by command of the President. The Commissioner for Lands and authorised offices in the various local authorities, are key officials in advising on what should be declared to be hazardous land. They may be unaware of this duty of theirs. Capacity building is therefore necessary, to create awareness within the Commissioner’s office of their duties. Historically, the majority of Commissioners for Lands have been lawyers but the National Land Policy imposes land management duties such as the declaration of land to be hazardous, and declaration of regularization areas on the Commissioner. In these two cases, the office of the Commissioner has not been active.

The needed capacity includes human resources such as people who have knowledge in GIS and remote sensing; financial resources; and awareness creation.

8.8. Prioritization of Identification of Hazardous Land

Besides prioritization of the declaration of hazardous land, the Ministry needs to require all authorized offices on the various local authorities to indentify, and demarcate such land to enable the Minister to make the necessary declaration. The fact that deaths occur regularly, and the fact that we are aware of the potential damage of climate change, mean that hazard land must be defined urgently in both rural and urban areas, and steps taken to prevent its occupation.

9. Conclusion

This study has established that, while there has been concern over the Msimbazi River Valley as a disaster-prone area, no legal steps or procedures have ever been taken to declare the area to be hazardous as the Land Act provides for. Concern has mainly heightened when there are floods. The duty to declare land to be hazardous is within the Minister for Lands on the advice of the Commissioner for Lands. Many officials were not aware of the existence of Land Form No. 2 (Notice of intention to Declare Hazardous Land) and Land Form No. 3 (Notice of Declaration of Hazardous Land). There are parallel Village Land Forms 6 and 7 for Village Land. Awareness that this is the case needs to be created and resources for implementation provided.

While the study does not want to single out Msimbazi Valley as the most hazard- prone area in Dar es Salaam, it recommends nevertheless that legal steps be taken to declare the area a hazardous area. Were this to be done, current occupiers will have a chance to express their views, and whatever stand is taken; the views of the occupiers will have been heard. Some clearly are entitled to compensation.

At the same time potentially hazardous lands within Dar es Salaam (and within other local authority areas) need to be identified and declared as a matter of urgency to prevent regular deaths from flooding. Technology can help in this; which can be undertaken as an independent activity, instead of waiting for the development of a city wide land use plan. Resources earmarked for dealing with the effects of climate change can be used for this purpose.

Procedures provided for in the law must be followed not only to avoid litigation but also to take advantage of public consultation provisions which will mean that communities will be aware of what land is hazardous and will make it their duty to protect it, especially if such land is converted into nature reserves such as urban forests or botanical gardens for common use.

Cite this paper

Kironde, J. M. L. (2016). Governance Deficits in Dealing with the Plight of Dwellers of Hazardous Land: The Case of the Msimbazi River Valley in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Current Urban Stu- dies, 4, 303-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/cus.2016.43021

References

- 1. AU-NEPAD, AFDB, UN/ISDR (2004). Guidelines for Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Assessment in Development. [Paper reference 1]

- 2. Centre for Community Initiatives (CCI) (2016). Assessment of the Impacts of Demolition of Houses along Msimbazi River. Unpublished Research Report. Dar es Salaam: CCI. [Paper reference 1]

- 3. Cheshire, P., & Vermuelen, W. (2009). Land Markets and Their Regulation: The Welfare Economics of Planning. LSE Research Online Version. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/307871 [Paper reference 1]

- 4. Douglas, I., Alam, K., Maghenda, M., McDonnel, Y., McLean, L., & Campbell, J. (2008). Unjust Waters. Climate Change, Flooding and the Urban Poor in Africa. Environment and Urbanisation, 20, 187-205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956247808089156 [Paper reference 3]

- 5. Fogwe, Z. N., & Asue, E. N. (2016). Cameroonian Urban Floodwater Retaliations in Human Activity and Infrastructural Development in Channel Floodways of Kumba. Current Urban Studies, 4, 85-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/cus.2016.41007 [Paper reference 1]

- 6. Kironde, J. M. L. (1995). The Evolution of the Land Use Structure of Dar es Salaam 1890-1990: A Study in the Impacts of Land Policy. PhD Thesis, Nairobi: Faculty of Architecture, Design and Development, University of Nairobi. [Paper reference 1]

- 7. Kironde, J. M. L. (2016). Implementation of the Provisions of the National Land Policy 1995 and Subsequent Legislation in Dealing with Hazard Land in Tanzania: The Case of Dar es Salaam. Research Report, Dar es Salaam: USAID Peri Peri U Project, Disaster Management Training Centre (DMTC), Ardhi University. [Paper reference 1]

- 8. Kiunsi, R., Kassenga, G., Lupala, J., Malele, B., Uhinga, G., & Rugai, D. (2009). Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction in Urban Planning Practice in Tanzania. Auran Phase II, Research Report, Dar es Salaam: Ardhi University. [Paper reference 1]

- 9. Misigaro, A. (2013). Orodha ya Halmashauri za Jiji, Manispaa, Wilaya, Miji na Mamlaka za Miji Midogo Zilizo na Mipango ya Jumla (General Planning Schemes). Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Lands. (Mimeo) [Paper reference 1]

- 10. Mufuruki, A. (2016). Open Letter to the Minister for Lands, and to the Minister for Environment. [Paper reference 1]

- 11. Ngware, N. (2003). A Crisis of Urban Settlements in Tanzania: Coping Strategies at Msimbazi Valley Dar es Salaam from a Gender Perspective. Research Report, Dar es Salaam: UCLAS. [Paper reference 1]

- 12. Pharoah, R. (2014). Built-In Risk: Linking Housing Concerns and Flood Risk in Subsidized Housing Settlements in Cape Town, South Africa. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 5, 313- 322. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13753-014-0032-3 [Paper reference 1]

- 13. Sakijege, T., Lupala, J., & Sheuya, S. (2012). Flooding, Flood Risks and Coping Strategies in Urban Informal Residential Areas: The Case of Keko Machungwa, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 4, 46-56. [Paper reference 1]

- 14. Sakijege, T., Sartohadi, J., Marfai, M. A., Kassenga, G., & Kasala, S. (2014) Government and Com- munity Involvement in Environmental Protection and Flood Risk Management: Lessons from Keko Machungwa, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Journal of Environmental Protection, 5, 760-771. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jep.2014.59078 [Paper reference 2]

- 15. URT (1999). Land Act 1999. Dar es Salaam: Government Printer. [Paper reference 1]

- 16. URT (2005). Strategic Plan for the Implementation of Land Laws I (SPILL). Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development. [Paper reference 1]

- 17. URT (2007). Urban Planning Act 2007. Dar es Salaam: Government Printer. [Paper reference 1]

- 18. URT (2013). Strategic Plan for the implementation of Land Laws II (SPILL). Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development. [Paper reference 1]

- 19. URT (2014). Budget Speech of the Minister of Lands to Parliament for Financial Year 2014/2015, Dar es Salaam: Government Printer. [Paper reference null]

- 20. URT (2015). Budget Speech of the Minister of Lands to Parliament for Financial Year 2015/2016. Dar es Salaam: Government Printer. [Paper reference 1]

- 21. URT (United Republic of Tanzania) (1995). National Land Policy. Dar es Salaam: Government Printer. [Paper reference 1]

- 22. Victor, M. A. M., Makalle, A. M. P., & Ngware, N. (2008). Establishing Indicators for Poverty-Environment Interaction in Tanzania: The Case of Bonde la Mpunga, kinondoni, Dar es Salaam. Research Report 08.4, Dar es Salaam: REPOA. [Paper reference 1]

Appendix 1: Land Form 2 Intention to Declare Hazardous Land

Appendix 2: Land Form 3, Declaration of Hazardous Land

NOTES

1Mwananchi, 18 January, 2016, p. 28.

2Mwananchi, 13 January, 2016, p. 17, “Bomoa bomoa ni tatizo mtambuka”.

3Daily News May 15, 2015.

4“Makonda awaonya wanaoishi mabondeni”, Uhuru, April 16, 2016, p. 3.

5“Mabomu yarindima bomoabomoa Dar”, Mwananchi, 31st December 2015, p. 3; “Dar demolition victims to JK’s land offer” Guardian January 21, 2016, p. 4.

6The Mchikichini and Upanga local government leaders said that out of the 1500, and 400 households in their areas, only 48 and 150 respectively got land.

7As of 2013, all the 5 cities and 18 municipalities in the country did not have a current approved general land use framework (Misigaro, 2013) .