Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2014, 2, 41-48 Published Online August 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.28007 How to cite this paper: Deng, K., Tsuda, A., Horiuchi, S., Kim, E., Matsuda, T., Doi, S., Tsuchiyagaito, A., Kobayashi, H. and Hong, K. (2014) Development of a Korean Version of Pro-Change’s Processes of Change Measure for Effective Stress Man- agement. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2, 41-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.28007 Development of a Korean Version of Pro-Change’s Processes of Change Measure for Effective Stress Management Ke Deng1, Akira Tsuda2, Satoshi Horiuchi3, Euiyeon Kim4, Terumi Matsuda5, Satomi Doi6, Aki Tsuchiyagaito6, Hisanori Kobayashi3, Kwangshik Hong7 1Institute of Comparative Studies of International Cultures and Societies, Kurume University, Kurume, Japan 2Department of Psychology, Kurume University, Kurume, Japan 3University of Rhode Island, Kingston, USA 4Department of Education, Inha University, Inchon, Korea 5Graduate School of Psychology, Kurume University, Kurume, Japan 6Graduate School of Psychological Science, Health Sciences University of Hokkaido, Tob et su , Japan 7Depart ment of Elemenrary Education, Jeonju National University of Education, Jeonju, Korea Email: sztouka@yahoo.co.jp Received Ju ly 2014 Abstract This study aimed to develop a Korean version of Pro-ch an ge’s processes of change measure for ef- fective stress management (PPSM). Effective stress management refers to any form of healthy ac- tivity practiced at least 20 min per day to manage stress. PPSM includes 30 items and consists of two higher-order and ten first-order factors. It measures the covert and overt strategies that indi- viduals use to initiate and maintain effective stress management, namely the processes of change. The participants included 542 Korean college students. The Korean version of PPSM was found to consist of two higher-order and ten fir st-order factors, which was consistent with the original PPSM. Reliability was examined in terms of internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.41 to 0.83, which was largely compatible to those of the original, Japanese, and Chinese PPSM. The Korean PPSM version was validated against the stages of change for effective stress management. The differences in the scores of the processes of change were largely consis- tent with those of previous studies. Keywords Processes of Change , Stages of Change , Effective Stress Management, Transtheoretical Mod el 1. Introduction Managing stress—that is, coping effectively with stressful situations—is a public concern in East Asian coun- tries such as Japan and South Korea [8 ] . Stressful experiences have been found to be linked to numerous chronic  K. Deng et al. diseases such as cardiovascular diseases [10]. To prevent stress-related health problems, it is important to prac- tice effective stress management [6], which refers to any form of healthy activity practiced for at least 20 min per day to reduce a person’s perceived stress [11] (P ro -Change Behavior Systems, Inc., 2003). Unfortunately, it is estimated that more than half of Korean college students do not engage in effective stress management [4], which points to a need for some assistance in practicing effective stress management. To design such interven- tions, appropriate behavioral change theories need to be identified. One such model is the transtheoretical model (TTM) of behavioral change [12]. This model describes beha- vioral change through five stages: precontemplation (havi ng no intention to begin in the next six months), con- templation (intending to begin in the next six months), preparation (intendi ng to begin in the next month), action (having been practicing for less than six months), and maintenance (havi ng been practicing for at least six mont hs). Other factors such as processes of change are assumed to facilitate stage transitions. Processes of change refer to the covert and overt strategies that individuals use to progress to the next stage. Ten processes of change are assumed to be needed to facilitate a stage transition. Table 1 gives a definition for each of these processes, which are divided into higher-order processes, and include both experiential and behavioral pro- cesses. Use of processes of change has been found to depend on stages of change. Pertinent to this study, Hor iuchi et al. [6] reported tight relationships between stages and processes of change for effective stress management. The least use of these processes was found in the precontemplation stage, whereas experiential processes were most frequently used in the preparation stage, and behavioral processes were most frequently used in the preparation, action, and maintenance stages. These results suggest that increasing and maintaining these processes are im- portant to progress through the stages. Model-based interventions have been found to successfully increase the proportion of participants practicing effective stress management [3] [5]. The development of a model-based intervention could provide Korean re- searchers and practitioners with a new intervention approach to help college students initiate effective stress mana ge ment practices. To do this, however, we first need a measure that can assess how frequently each indi- vidual uses each process of change. Such a measure not only enables the identification of specific processes that affect stage progression but also allows practitioners to assess the interventions based on the TTM. Unfort u- nately, no measure is currently available for assessing the processes of change for effective stress management. Pro-change’s processes of change measure for effective stress management (PPSM) [2] have been shown to be a reliable and valid measure. PPSM includes 30 items, with two higher-order factors (experiential and beha- vioral processes) and ten first-order factors (individual processes). Its structure was evaluated and found to be acceptable, with a comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.76. Reliability was also found to be acceptable with Cron- bach α coefficients ranging from 0.59 to 0.79. Validity was confirmed with significant inter-stage differences in the use of the processes. This study aimed to develop a Korean version of PPSM. Table 1. Processes of change for effective stress management. Processes of change Definition Experiential processes Consciousness raising Increasing awareness Dramatic relief Reacting emotionally to warnings about stress Environmental re-evaluation Considering how the practice or lack of stress management affects others Self-re-evaluation Realizing that stress management can enhance one’s identity Social liberation Acknowledging how society is changing to encourage stress management Behavioral processes Self-liberation Making a commitment to initiate stress management Helping relationships Listing and utilizing support for stress management Reinforcement management Using positive reinforcement and reward for stress management Counter conditioning Substituting new and positive behavioral choices Stimulus control Restructuring one’s environment for stress management  K. Deng et al. 2. Method 2.1. Participants and Procedure s The institutional review board of Kurume University approved this study. Five-hundred and eighty Korean col- lege students gave informed written consent for the participation, and completed the questionnaire packet. The data of 22 students were removed as they had not been stressed over the past month, which was assessed using the staging algorithm described below. A further 16 students were removed because of missing data. The final data of 542 Korean college students were subject to the analyses. Of the 542 stud e nts , 206 were male and 336 were female. The average age was 20.77, with a standard deviation of 2.91 years. The participants included 35.98% freshmen (n = 195), 37.27% sophomores (n = 202), 22.64% juniors (n = 123), and 4.06% seniors (n = 22). 2.2. Measures 2.2.1. Processes of Change PPSM (Evers et al., 2000) [2] was translated into Korean for this study, with permission from Pro-Change Beha- vior Systems, Inc. First, two Korean psychologists translated the PPSM English items into Korean. Another two psychologists checked that the original meaning of each item had not changed through the translation. Each par- ticipant was asked to rate each of the 30 PPSM items on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 5 = Repeatedly). 2.2.2. Stages of Cha nge The participants’ stages of change were assessed using the Korean version of Pro-Change’s staging algorithm [7]. The participants were asked whether they effectively managed stress in their daily life. They chose from one of the si x items that represented the five stages and a further item “I had no stress.” A one-week test-retest relia- bility was found to be acceptable. Validity was confirmed by demonstrating that the relationships of depressive symptoms were consistent with the predictions [7]. 2.3. Statistical Analyses The analyses were conducted using SPSS 20 for Windows and R. The statistical significance was set as p < 0.05. First, to examine if the Korean PPSM version consisted of two higher-order and ten first-order factors, a con- firmatory factor analysis was conducted. Three items were expected to represent one fir st-order factor and five first-order factors were expected to repr esent one higher-order factor. The root mean square error of approxima- tion (RMSEA) and CFI were used to evaluate the model fit. RMSEA values of less than 0.08 show an accepta- ble fit, and those of 0.76 or larger show a compatible fit to the original measure. Then, reliability was evaluated in terms of internal consistency. The Cronbach α coefficient was calculated for each subscale. Finally, to vali- date the Korean PPSM version, we examined whether the differences in mean values for the processes of change for effective stress management across the five stages were consistent with those of Horiuchi et al. [6]. Te- none -way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted. The model assumes that the processes of change cause stage transitions [13], so they were put in the ANOVAs as independent variables. However, this study aimed to examine the relationships between the stages and processes of change. In previous cross-sectional stu- dies of the relationships between processes and stages of change for effective stress management [1] [2] [6], processes of change were put into the analyses as a dependent variable. Therefore, this study also put the processes of change as the dependent variable. 3. Results 3.1. Factor St ru cture A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to examine whether the original PPSM factor structure was ac- ceptable in this sample. The two higher-order and ten first-order factor models showed an acceptable fit to the data (CFI = 0.81; RMSEA = 0.07). The factor loadings ranged from 0.32 to 0.89 (Table 2). Strong correlations emerged between the fir s t - and higher-order factors with the standardized path coefficients ranging from 0.60 to 1.01 (Figure 1).  K. Deng et al. Table 2. Item factor loadingsfor the Korean PPSM* version. Item Factor loadings Consciousness raising (α = 0.75) I search for information about how to deal with stress in a healthy way. 0.73 I think about information on healthy stress management. 0.83 I read about people who have successfully used healthy stress management techniques. 0.72 Dramatic relief (α = 0.53) I get upset when people ignore health warnings about not practicing stress management. 0.68 It upsets me to hear about people who do not manage their stress in a healthy way. 0.72 I react emotionally to warnings about stress. 0.42 Environmental re-evaluation (α = 0.73) I think about how managing my stress in a healthy way would have a positive effect on the people around me. 0.66 I stop to think about how my stress can affect others. 0.74 I consider how managing my stress would benefit my family and friends. 0.77 Self-re-evaluation (α = 0.70) I feel good about myself when I use healthy strategies to manage my stress. 0.66 I believe that I am a more confident person when I successfully manage my stress. 0.56 I see myself as a more responsible person when I manage my stress. 0.75 Social liberation (α = 0.46) Society is providing more healthy options for managing stress. 0.32 I notice that managing stress is becoming a greater concern in our society. 0.55 I notice stress management techniques being discussed more openly. 0.67 Self-liberation (α = 0.54) I refuse to use unhealthy strategies to manage my stress. 0.36 I tell myself that I can choose to manage my stress in a healthy way. 0.65 I promise myself that I will take active steps to manage my stress. 0.65 Helping relationships (α = 0.77) I have someone I can count on when I experience stress in my life. 0.66 There is at least one person who can provide feedback about how I’m managing my stress. 0.78 An important person in my life helps me confront my problems with managing my stress. 0.89 Reinforcement management (α = 0.83) Friends and family say something positive when I use healthy strategies to manage stress. 0.77 Others praise my choice to use healthy strategies to manage stress. 0.84 I am rewarded by others when I use healthy strategies to manage stress. 0.81 Counter conditioning (α = 0.41) When I start to feel stressed out, I take a short break to relax. 0.33 I focus on one problem at a time instead of becoming overwhelmed by stress. 0.39 When I begin to feel stressed, I engage in healthy activities I enjoy. 0.59 Stimulus control (α = 0.57) I save some healthy pleasures, like taped TV shows, for times of stress. 0.39 I keep things at home that remind me to use healthy stress management techniques. 0.64 I keep reminders to think positively when I feel stressed. 0.64 Note: PPSM = Pro-Change’s processes of change measure for effective stress management. *© 2004. Pro-Change Behavior Systems, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 3.2. Reliability The Cronbach’s α coefficient was calculated for each subscale (Table 2), and ranged from 0.41 to 0.83. While the α coefficients for the five subscales were at 0.60 or above, those for the other subscales were below 0.59.  K. Deng et al. Figure 1. Hierarchal model for the processes of change for effective stress management. CR = consciousness raising, DR = dramatic relief, ER = environmental re-evaluation, SR = self-re- evaluatio n, SO = social liberation, SL = self-liberation, HR = helping relationships, RM = reinforcement management, CC = counter conditioning, SC = stimulus control. 3.3. Validity The distribution of the participants was as follows: 16.79% in preconte mplation (n = 91), 21.59% in contempla- tion (n = 117), 26.20% in preparation (n = 142), 12.18% in action (n = 66), and 23.25% in maintenance (n = 126).The distribution was independent of gender (χ(4)2 = 2.89, p = 0.58). To examine the validity of the Korean PPSM version, the relationships between the stages and processes of change were examined using ten ANOVAs. The differences in the processes of change scores across the stages are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The results of these ANOVAs are summarized in Table 3. The ANOVAs found significant main effects in the stages for all ten processes. The differences in the scores for the processes of change showed patterns of increase in the processes’ use across the stages. 4. Discussion This is the first study in which a measure for the processes of change for effective stress management was de- veloped in South Korea. After translating PPSM into Korean, its factor structure, reliability, and validity were examined. The Korean PPSM version provides aninitial tool to assess the use of each process of change for ef- fective stress management. The model enables researchers and practitioners to develop interventions that help people manage stress by tailoring the intervention content to an individual’s stages. This requires the identifica- tion of specific processes that cause forward stage transitions, such as the progression from precontemplation to contemplation. The Korean PPSM version is expected to not only enable researchers identify such processes but also to assist practitioner se valuate the effects of interventions based on the TTM. The two higher- and ten first-order factor structures in the Korean PPSM version were supported by a co nfi r- matory factor analysis. The value of CFI was compatible to that of the original PPSM (0.81 versus 0.76). In ad- dition, the RMSEA value was found to be acceptable. However, note that two of the ten path coefficients be- tween the first- and higher-order factors exceeded 1.00. These abnormal values indicated that ten of the ind ivid- ual processes of change were highly correlated. These high correlations were also found in a sample of Chinese college students, wher e Deng et al. [1] reported that the path coefficients ranged from 0.60 to 0.93 and ten processes were found to be highly correlated. Because of these high correlations, it could be argued that the va- lidity of the division of the processes of change into ten processes should be re-examined. We agree with this possible argument, but accept the two hi g her -order and ten-factor model because of the following two reasons. First, five experiential and five behavioral processes are clearly differentiated in the content, and differential techniques are required to facilitate each process. Second, we aim to develop the Korean PPSM version, whose development will enable further explorations into the validity on Korean populations. The reliability of the Korean PPSM version was examined in terms of internal consistency. The α coefficie nt for each subscale ranged from 0.41 to 0.83 . The subscales for dramatic relief, social liberation, self-liberation,  K. Deng et al. Figure 2. Differences in the scores for the experiential processes across the stages of change for effective stress management. Not e: PC = precontemplation; C = contemplation; PR = preparation; A = action; M = maint enance. Figure 3. Differences in the behavioral processes scores across the stages of change for effec- tive stress management. Note: PC = precontemplation; C = contemplation; PR = preparation; A = action; M = maintenan ce. counter conditioning, and stimulus control were below acceptable values (i.e., >0.60). Among the five subscales, the low value of the counter c o nd it io ni ng subscale (α = 0.41) was in line with that of the original PPSM (α = 0.59) [2]. The three items that assess counter c o nd it i o ni ng include three coping options to manage stress. It is expected that the broadness of the subscale resulted in low α values. Relatively low α values for dramatic relief (α = 0.53), self-liberation (α = 0.54), and stimulus control (α = 0.57) were lower than those for the original PPSM, but were largely consistent with those for the Chinese (α = 0.49 - 0.65) [1] and Japanese PPSM (α = 0.55 - 0.73) [6]. Note that the low α value fo r social liberation (α = 0.46) was substantially lower than that for the Chinese (α = 0.67) [1] and Japanese PPSM (α = 0.69) [6]. In summary, nine of the ten subscales in the Korean PPSM version showed compatible levels of internal consistency to the Japanese and Chine se PPSM. These re- sults suggested that the Korean PPSM version can be useful for cross-cultural studies a cr oss mainland China, Japan, and South Korea.  K. Deng et al. Table 3. Summary of analyses of variances. Processes of change F(4, 537) Results of Tukey HSD Experiential processes Consciousness raising 9.78** PC < PR, A, M; C < A, M; PR < A Dramatic relief 3.54** PC < PR, A Environmental re-evaluation 9.84** PC < C, PR, A, M Self-re-evaluation 13.45** PC < PR, A, M; C < A, M; PR < M Social liberation 11.76** PC, C, PR < A, M Behavioral processes Self-liberation 14.01** PC < C, PR, A, M; C < A, M; PR < M Helping relationships 11.20** PC < M; C < A, M; PR < M Reinforcement management 9.96** PC, M < A, M; PR < M Counter conditioning 12.90** PC, C, PR < A, M Stimulus control 17.20** PC, C, PR < A, M Note: PC = precontemplation; C = contemplation; PR = preparation; A = action; M = maintenance. The measure was validated against the stages of change. Consistent with the findings of previous studies [1] [6], the use of each process was at least in precontemplation. Individuals in this stage are not ready to initiate effective stress management, so it is reasonable that they would use the processes less frequently. Differences in the experiential and behavioral processes across the stages showed patterns of increase in the use of these processes, which was largely consistent with the findings of previous studies [1] [6]. The progression through effective stress management stages requires the initiation and maintenance of healthy activities to manage stress. Thus, it is reasonable that the use of both experiential and behavioral processes is more frequent in the action and maintenance stages than in the earlier stages. These results supported the validity of the Korean PPSM ver- sion. The results of this study provide a new measure that can a sses s the pro cesses of change for effective stress management in Korean college students. Helping college students to manage stress is an important issue for South Korea [4], and this new measure is expected to be used in future studies in South Korea. In addition, the results extend the literature by providing initial evidence that supports the application of the processes of change to stress management in Korean college students. Studies applying processes of change in stress management have been reported from other countries such as United States [2], J ap an [6], mainland China [1], and Germany [15], but it had been unknown as to whether this construct would be applicable to the South Korean population. Hence, this extension is important. Nishimura and Chikamoto [9 ] pointed out the importance of examining the external validity of findings when the findings in some cultures are applied to other cultures. This study pre- dicted the relationships between the stages and processes of change for effective stress management in Ko rean college students. Therefore, the study results suggested that the processes of change can be applied to effective stress management in Korean college students. The study has following limitations. First, the participants were recruited at only two colleges. As a result, it remains to be seen how representative the participants were as a sample of Korean college students. This study succe ssfu ll y developed the Korean PPSM version, which can be used for cross-cultural comparative studies with the United States, mainland China, Japan, and South Korea. Based on the study results, it is possible to examine the extent to which the findings can be generalized. Second, it remains unclear whether the Korean PPSM ver- sion is appropriate for populations other than students. To assess this, other populations need to be examined based on the study findi n gs. References [1] Deng, K., Tsuda, A., Horiuchi, S. and Matsuda, T. (2013) Relationships between Stages and Processes of Changefor Effective Stress Management in Chinese College Students. Stress Science Research, 28 , 74-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.5058/stresskagakukenkyu.28.74 [2] Evers, K.E., Evans, J.L., Fava, J.L. and Prochaska, J.O. (2000) Development and Validation of Trans Theoretical Model Variables Applied to Stress Management. Presented at the 21st Annual Scientific Sessions of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, Nashville.  K. Deng et al. [3] Evers, K.E., Prochaska, J.O., Johnson, J. L., Mauriello, L. M., Padula, J. A. and Prochaska, J.M. (2006) A Randomized Clinical Trial of a Population- and Transtheoretical Model-based Stress-management Intervention. Health Psychology, 25, 521-529. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.521 [4] Horiuchi, S., Tsuda, A., Kim, E., Hong, K.-S. and Prochaska, J.M. (2010) Relationship between Stage of Change and Self-Efficacy for Stress Management Behavior in Korean University Students. Japanese Journal of Behavioral Medi- cine, 16 , 12-20. [5] Horiuchi, S., Tsuda, A., Kim, E., Morita, T. and Kobayashi, H. (2013) Effectiveness of the Expert System for Modify- ing Effective Stress Management Behavior based on the Transtheoretical Model in College Students. Stress Manage- ment Research, 9, 69-84. [6] Horiuchi, S., Tsuda, A., Prochaska, J. M., Kobayashi, H. and Mihara, K. (2012) Relationships between Stages and Processes of Change for Effective Stress Management in Japanese College Students. Psych olog y, 3, 494-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.36070 [7] Kim, E., Tsuda, A., Horiuchi, S., Park, Y.-S., Kim, U. and Hong, K.-S. (2009) The Relationship between Stages of Change for Stress Management and Depressive Symptoms in a Sample of Korean University Students. Kurume Uni- versity Psychological Research, 8, 103-110. [8] Kim, U., Park, Y-S, Kim, E., Tsuda, A. and Horiuchi, S. (2010) The Influence of Parental Social Support and Resi- liency of Efficacy on Stress, Depression, and Stress Management Behavior: Comparative Analysis of Elementary School, Middle School and University Students. Korean Journal of Psycholog y and Social Issu es, 16, 197-219. [9] Nishimura, Y. and Chikamoto, Y. (2005) Health Promotion in Japan: Comparisons with U.S. Perspectives. American Journal of Health Promotion, 19, 213-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-19.3s.213 [10] McEwen, B.S. (2007) Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain. Physiological Reviews, 87, 873-904. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00041.2006 [11] P ro -Change Behavior Systems, Inc. (2003) Road to Healthy Living: A Guide for Effective Stress Management. P ro -Change Behavior Systems, Inc., Kingston. [12] Prochaska, J.O. and DiClemente, C.C. (1983) Stages and Processes of Self-Change of Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 390-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X. 51. 3.39 0 [13] ]rochaska, J.O., DiClemente, C.C. and Norcross, J.C. (1992) In Search of How People Change. Applications to Addic- tive Behaviors, 47, 1102-1114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102 [14] Vandenberg, R.J. and Lance, C.E. (2000) A Review and Synthesis of the Measurement Invariance Literature: Sugges- tions, Practices, and Recommendations for Organizational Research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/109442810031002 [15] Vierhausa, M., Maassa, A., Fridricia, M. and Lohausa, A. (2010) Effects of a School-Based Stress Prevention Pro- gramme on Adolescents in Different Phases of Behavioural Change. Educational Psychology, 30, 465-480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0144341100372462 4

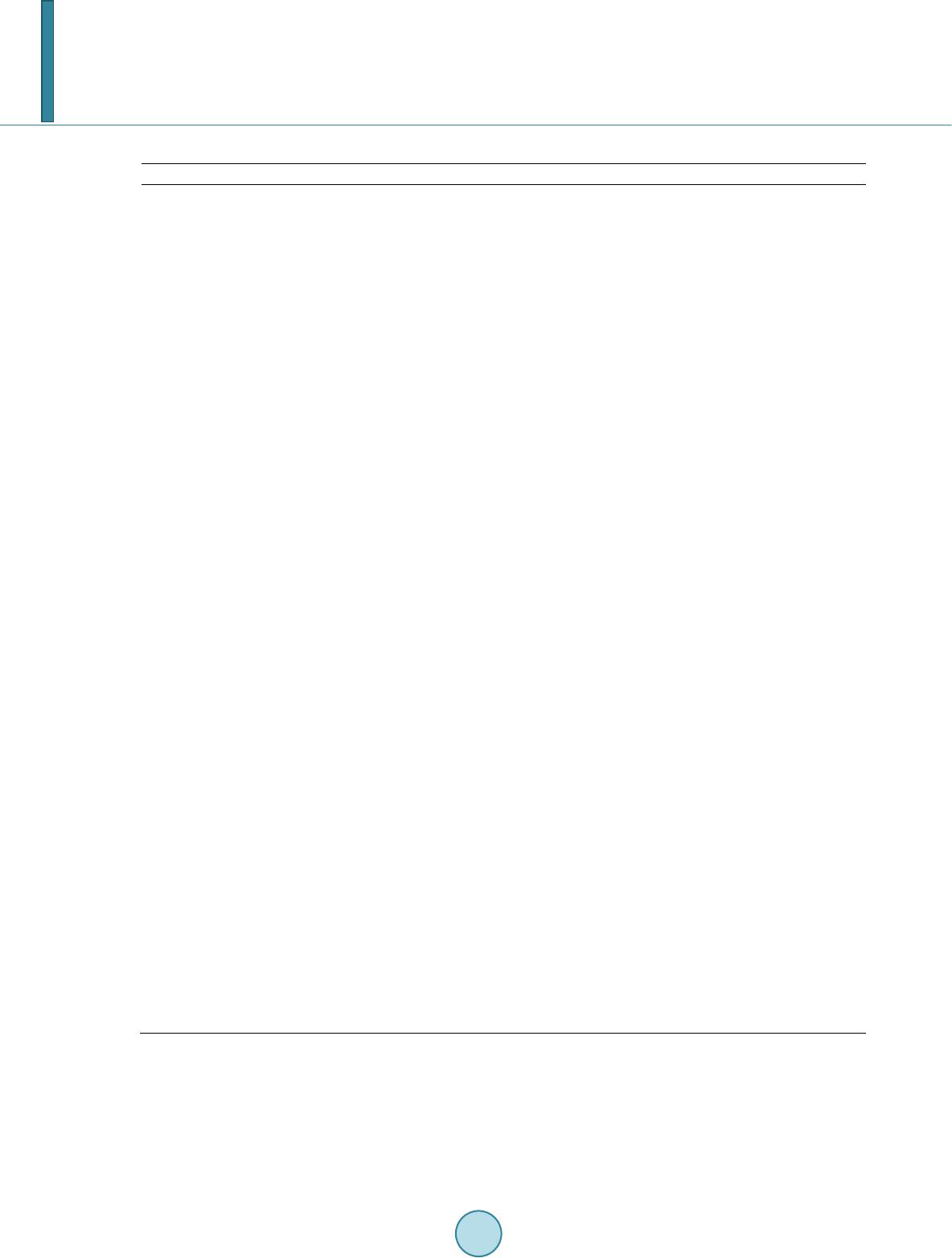

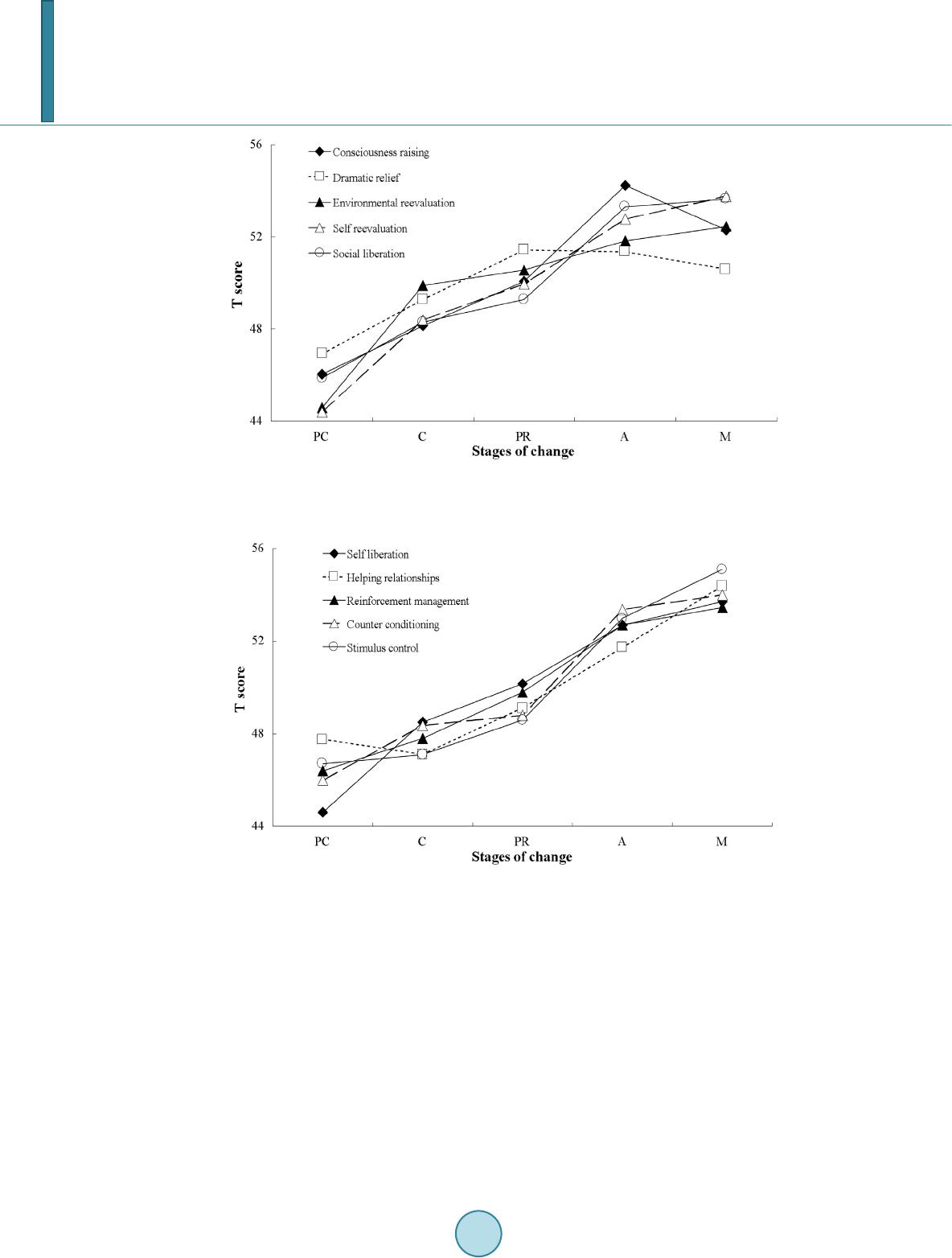

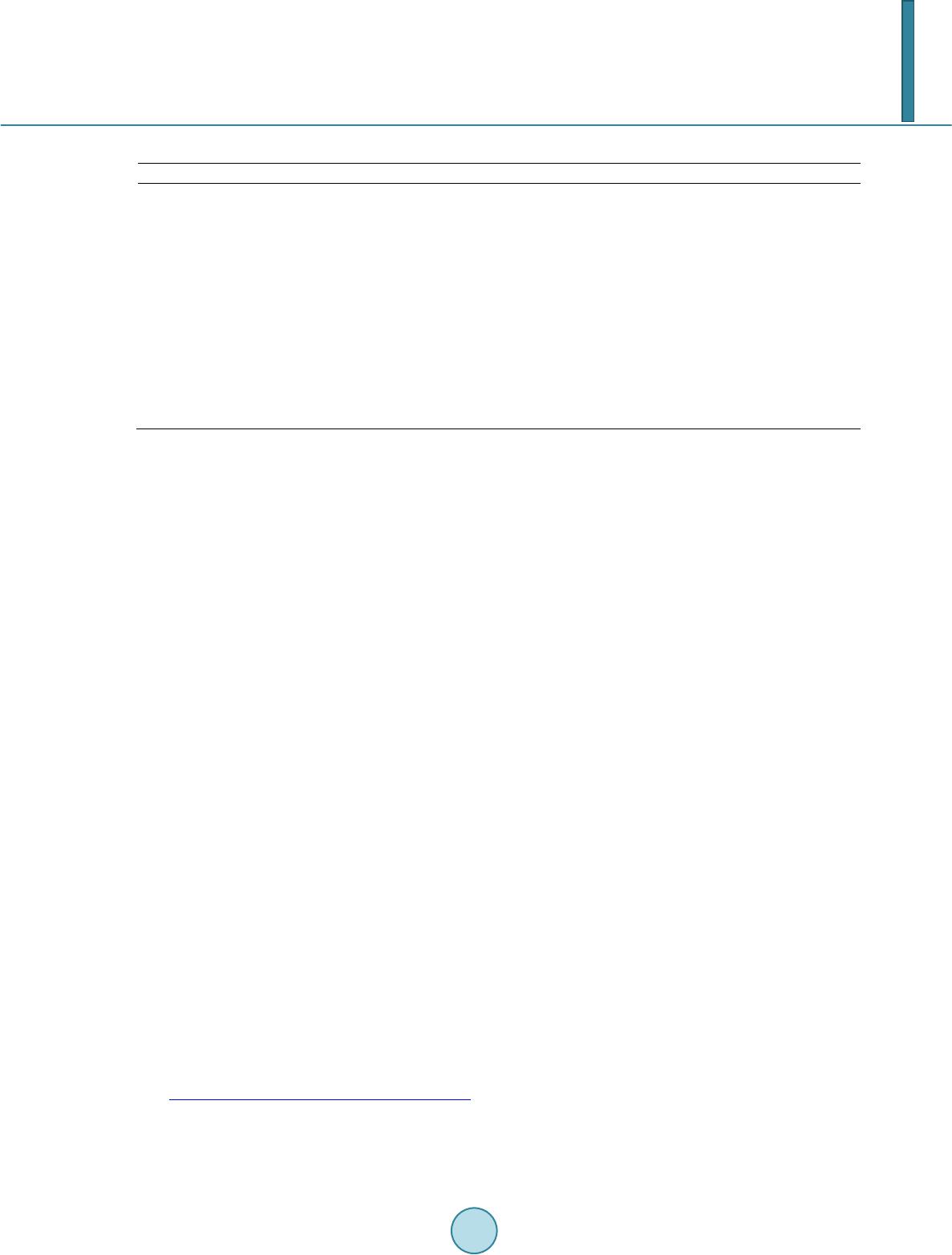

|