Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

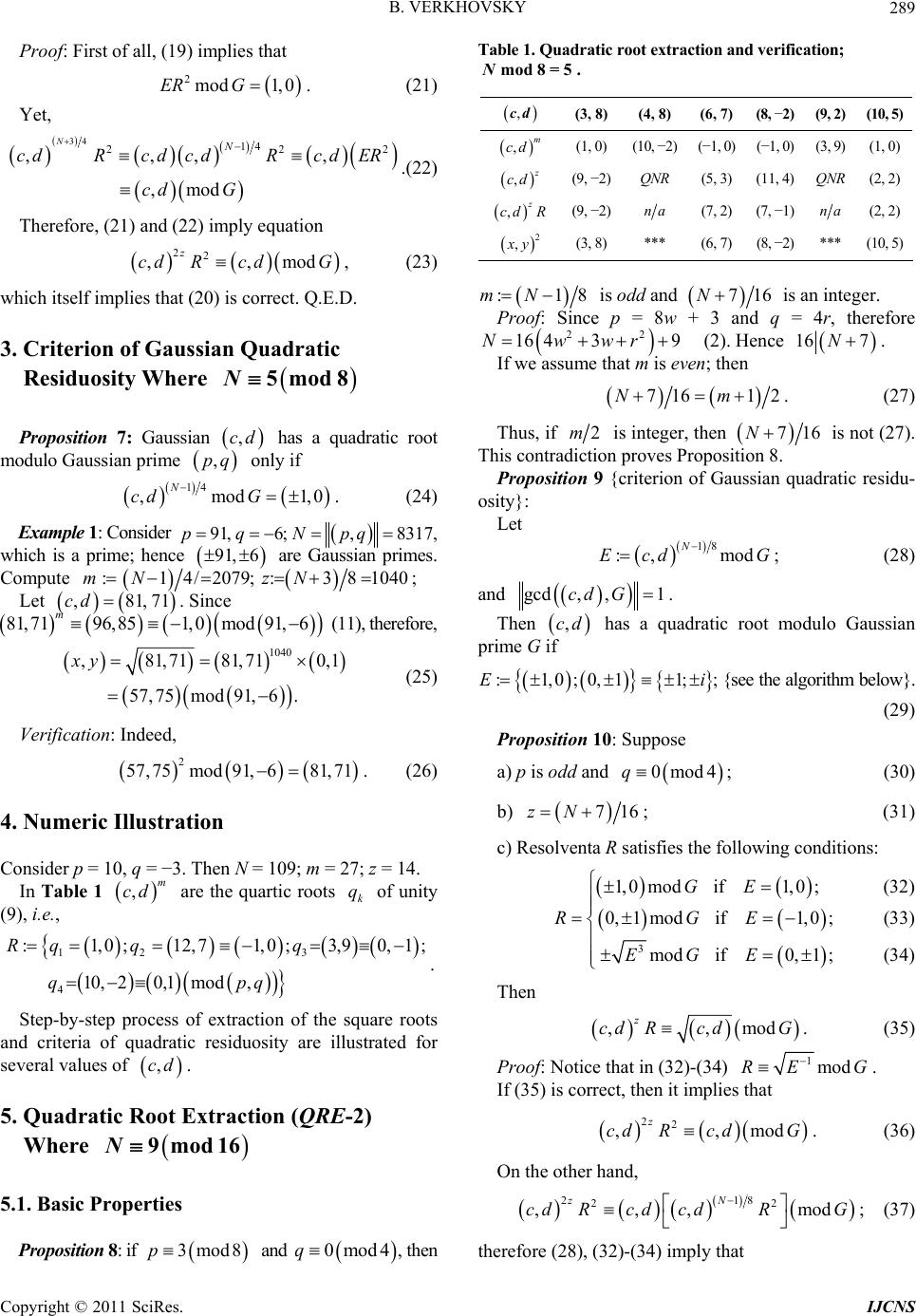

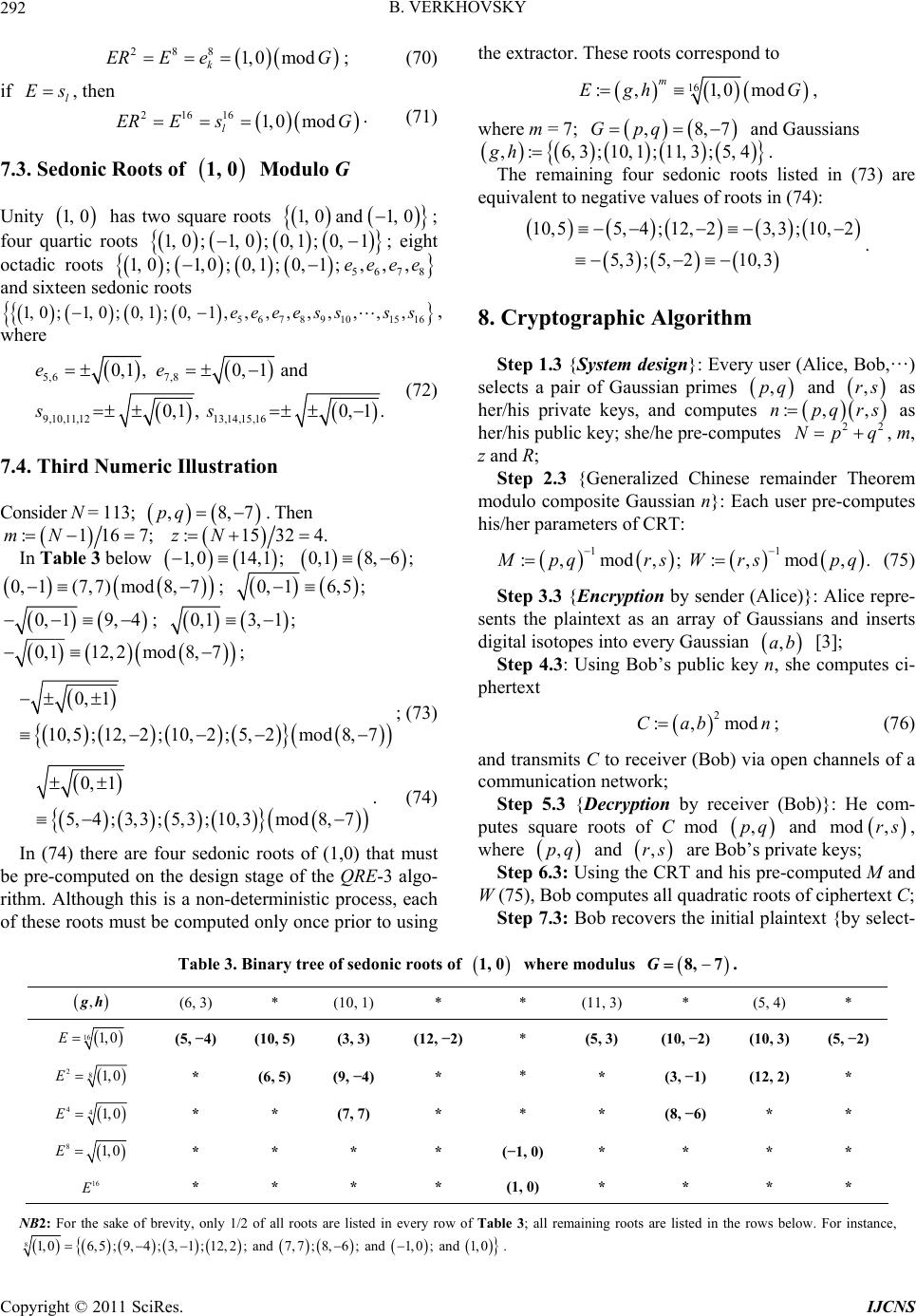

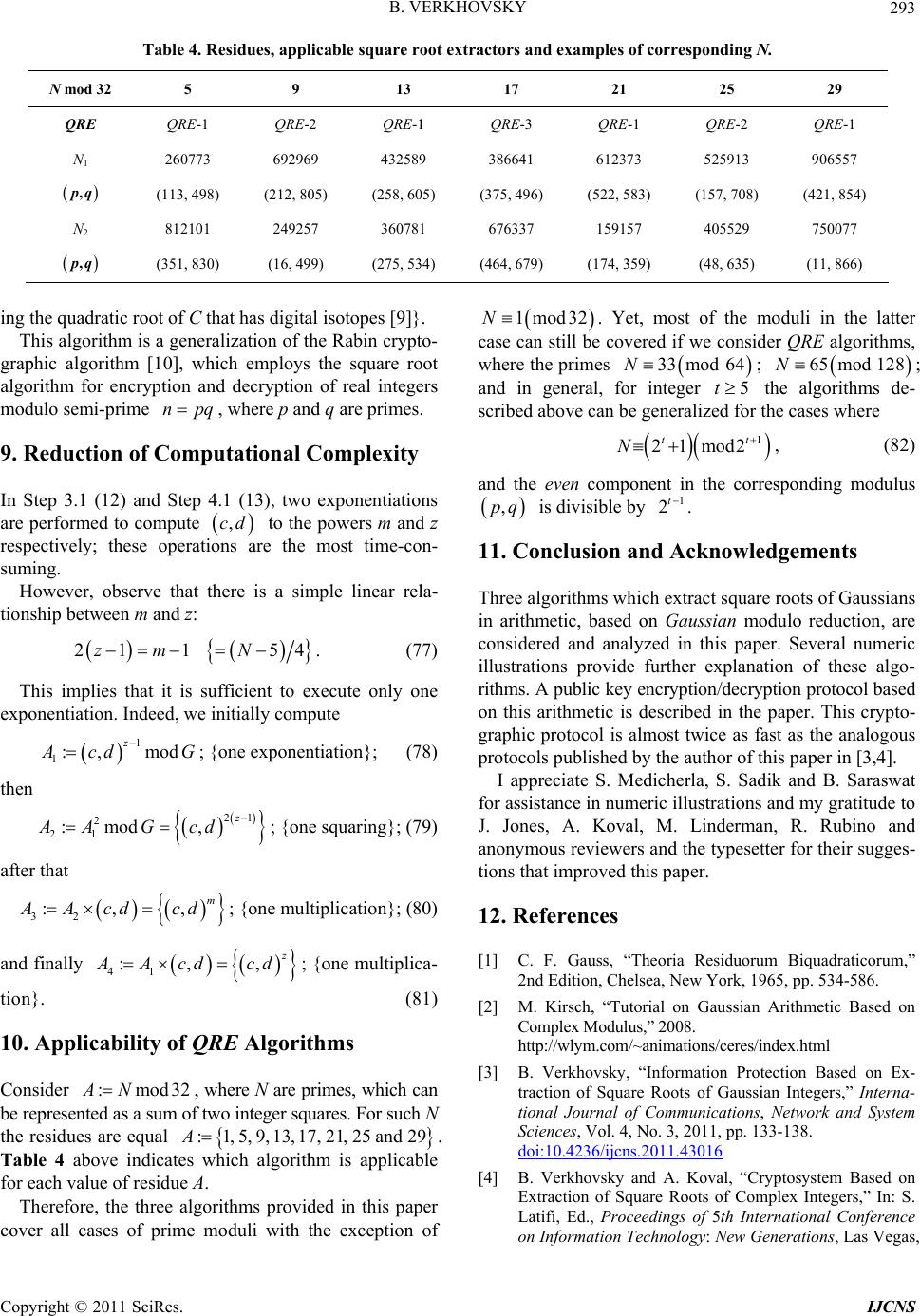

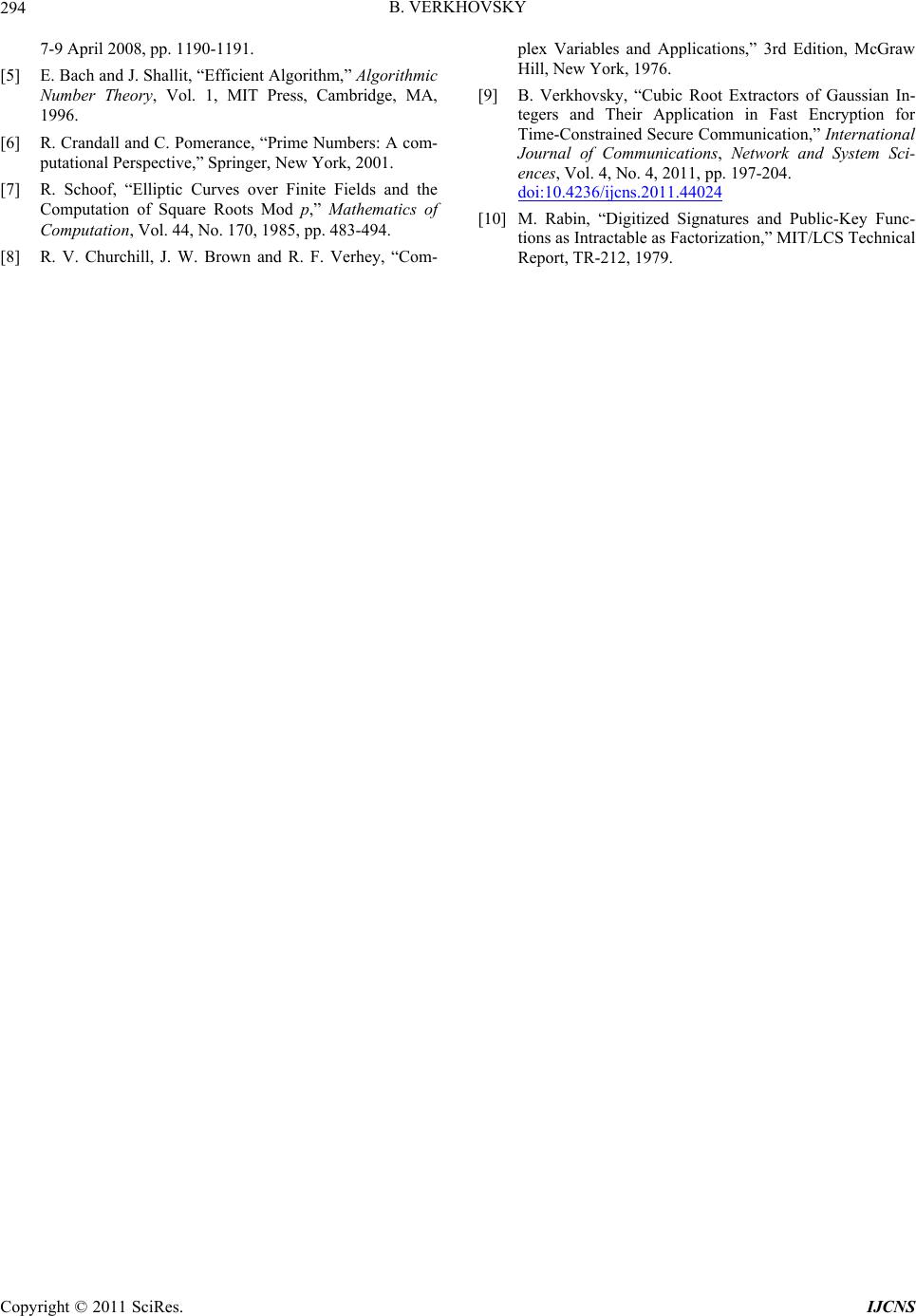

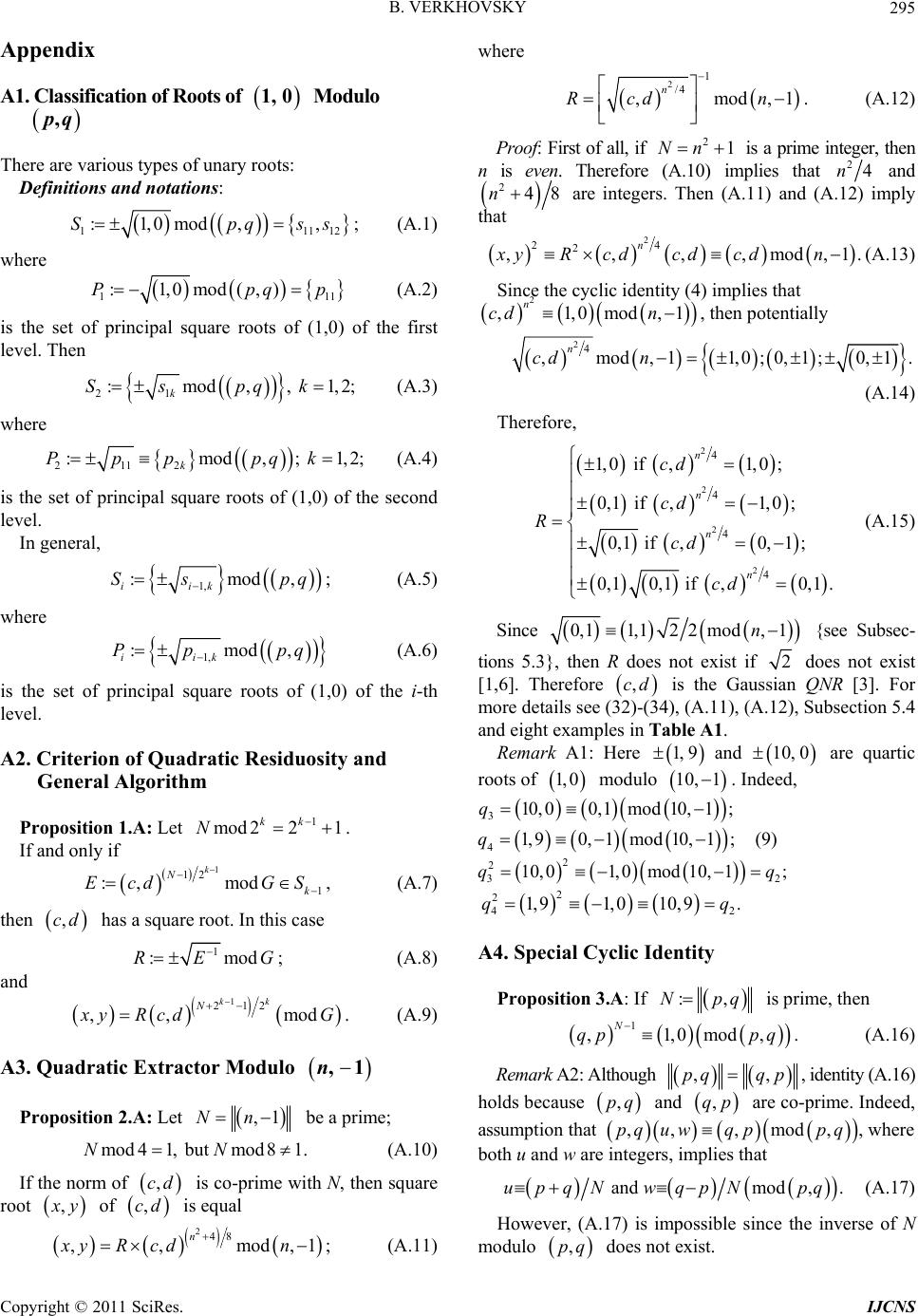

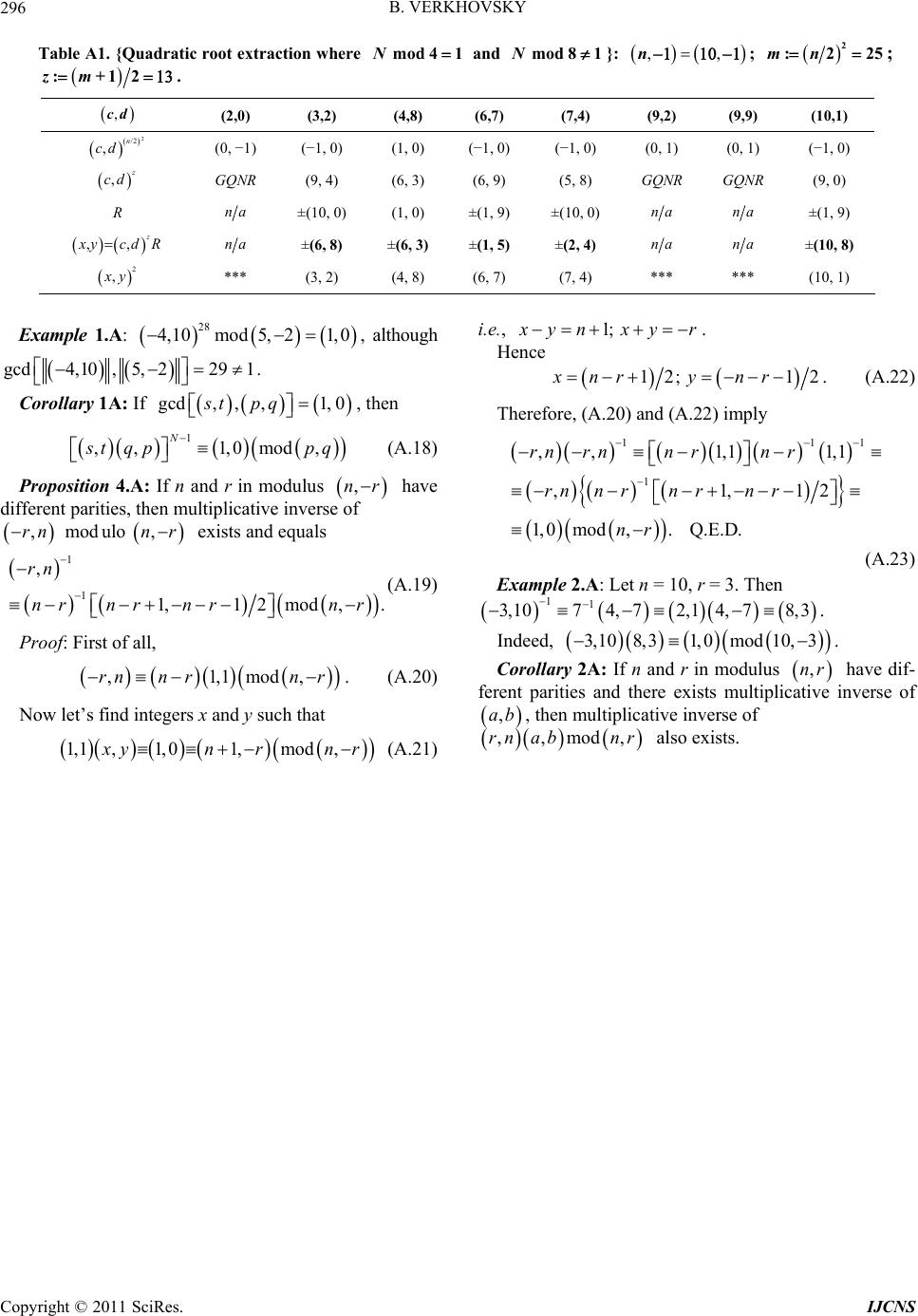

Int. J. Communications, Network and System Sciences, 2011, 4, 287-296 doi:10.4236/ijcns.2011.45033 Published Online May 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ijcns) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS Protection of Sensitive Messages Based on Quadratic Roots of Gaussians: Groups with Complex Modulus* Boris Verkhovsky Computer Science Department, New Jersey Institute of Technology, University Heights, Newark, USA E-mail: verb73@gmail.com Received April 5, 2011; revised May 3, 2011; accepted May 20, 2011 Abstract This paper considers three algorithms for the extraction of square roots of complex integers {called Gaus- sians} using arithmetic based on complex modulus p + iq. These algorithms are almost twice as fast as the analogous algorithms extracting square roots of either real or complex integers in arithmetic based on modulus p, where p is a real prime. A cryptographic system based on these algorithms is provided in this paper. A procedure reducing the computational complexity is described as well. Main results are explained in several numeric illustrations. Keywords: Complex Modulus; Computational Efficiency; Cryptographic Algorithm; Digital Isotopes; Multiplicative Control Parameter; Octadic Roots, Quartic Roots, Rabin Algorithm, Reduction of Complexity, Resolventa, Secure Communication, Square Roots 1. Introduction and Problem Statement The concept of complex modulus was introduced by C. F. Gauss [1]. The set of complex integers is an infinite sys- tem of equidistant points located on parallel straight lines, such that the infinite plane is decomposable into infi- nitely many squares. Analogously, every integer that is divisible by a complex integer m = a + bi forms infini- tely many squares, with sides equal to 22 ab. 1.1. Complex Moduli Let’s denote . Associates of ,:aba bi :,Gpq are –G, iG and –iG; they are the vertices of a square where ; ,Gpq 0, 1,p q ,q piG , ,p qqp ; . 0, 1iG To understand the congruencies, let’s consider a sys- tem of integer Cartesian coordinates. The squares on this system of coordinates are inclined to the former squares if neither of integers a, b is equal to zero [1]. Then the associates of the modulus are rotations of “vec- tor” on 90 degrees. Let’s consider the plane of complex numbers and as an example, the complex prime number [2]. Let the left-most bottom point of the mesh be the origin of the coordinate system for Gaussians, and let be the Gaussian modulus. Inside each square there is a number of Gaus- sian integers; plus every vertex of each square is also a Gaussian integer. In order to avoid multiple counting of the same vertex, we consider that only the left-most bot- tom vertex of each square belongs to that square [1]. For more insights and graphics see [2]. ,pq , ,pq 1, 4 :14i :1 41,4Gi 2 ,,mod This paper is a logical continuation of a recently pub- lished paper [3], which considered a cryptographic scheme based on complex integers modulo real semi-prime pq. The above mentioned paper describes an extractor of quadratic roots from complex integers called Gaussians. A slightly different approach is considered in [4]. Several general ideas for computation of a square root in modular arithmetic are provided in [5-7]. This paper considers arithmetic based on complex in- tegers with Gaussian modulus. As demonstrated below, the extraction of square roots in such arithmetic requires a smaller number of basic operations. As a result, the described cryptographic system is almost twice faster than the analogous systems in [3,4]. Consider quadratic equation x ycdpq, (1) where modulus :,Gpq is a Gaussian prime; and let 2 :,Npqpq 2 . (2) *Dedicated to the memory of Samuel A. Verkhovsky.  B. VERKHOVSKY 288 1.2. General Properties Proposition 1: Gaussian is a prime if and only if its norm N is a real prime [1]. ,pq Remark 1: Since ,,pq qp , without loss of generality we assume that, if is prime, then p is odd and q is even {unless it is stated otherwise}. ,pq Proposition 2: If norm of ,pq is a prime (2), then for every ,, 14pq N is an integer. Proof: Let and . Then (2) implies that :2 1pk :2qr r 2 14 1Nkk . Q.E.D. (3) Proposition 3 {cyclic identity}: If g cd,,,1, 0abpq and G is a prime, then the following identity holds: 1 ,mod,1, N ab pq 0 d . (4) Remark 2: More details about identity (4) are provided in the Appendix in Proposition 3.A. Proposition 4 {Modular multiplicative inverse}: if , then gcd, ,,1,0abpq 12 ,,mo N ab abG . (5) Remark 3: Yet, more computationally-efficient is to solve an appropriate Diophantine equation. However, this is beyond the scope of this paper. Definition 1: Gaussian , x y is called a quadratic root of modulo G if ,cd , x y and satisfy Equation (1); we denote it as ,cd ,: ,mod x ycdG. (6) 2. Quadratic Root Extraction Where 5mod8N Proposition 5: If ,pq is prime and 5mod8N, then :14 moq mN is odd. Proof: Notice that d 42 , otherwise (3) implies that . Q.E.D. 1mod8N 2.1. Quadratic and Quartic Roots of 1, 0 Modulo ,pq Consider a quadratic root ,uw of mo1, 0d,pq: ,: 1,0mod,uw pq , Thi Go (7) Since the last equation does not lu . Then ,uw s equation holds if either w = 0 and 2 ur if u = 0 and 222 ,21,0moduw uwpq . 1mod; 21modGw . have a real integer so- tion for w, it implies that ,0, modp qG ,1,01uw . (8) Hence, if a root , x y is known, then another root of ,d is c ,y There ar , d.uw xG mo oots: e Qu 1, 0, artic rfour quartic roots of each satisfying 41,0 k q: (1,0);qq q 123 4 (1,0);0,1;0,1 ;q (9) where 22 3,4 22 1 mod; 1,0mod.qq GqqG .2. Quadratic Root Extractor (QRE-1) Step 1.1: Compute 2 22 :; Nmpq :14; 38NzN (10) Step 2.1: if N is not a prime, then QRE-1 algor no ithm is t applicable, na ; Remark 4: 1,1, 0modpq G; (11) Step 3.1: Compute (12) Step 4.1: if mod m cd G; :,E 0, 1E , due (GQNR then dr 5.1: if ,cd its squ is Gaussian qua- atic non-resi}, i.e. are root does not exist; Step 1, 0E, then 38 m N x ,: ,odyc G; (13) Step 6.1: if d 1, 0E , then 1 :0,1 mod;mod REGGR ; (14) ,:,mod z x yRcd G ; nd (15) Step 7.1 {2 square root}: ,:1,,tvpqxymodG (11). (16) .3. Validation of Algorithm Proposition 6: Suppose 2 a) ,pq is a prime and 2mod4q; (17) b) 14 38; md :,o N Ecd GzN ; (18) c) 1 if 1,mod0 or 1,0REEG ; (19) then ,,mo z cd RcdG.d (20) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS  B. VERKHOVSKY289 Proof: First of all, (19) implies that (21) Yet, 2mod1, 0ERG . 34 14 222 ,, , ,mod NN R cdcdR cdER cd G .(22) Therefore, (21) and (22) imply equation (23) which itself implies that (20) is correct. Q.E. has a quadratic root odulo Gaussian prime ly if ,cd ,,modcd RcdG 22 z, D. 3. Criterion of Gaussian Quadratic Residuosity Where 5mod8N Proposition 7: Gaussian ,cd ,pq onm 14 ,md1,0 N cd G . (24) o Example 1: Consider ,8317,pq es. 91,6; Npq which is a prime; hence are Gaussian prim C 91, 6 ompute : 1mN Let ,81,71cd . S 4/2079; : ince 38 1040zN ; 81,71 m 96,85 1,0mod 91,6 (11), therefore, 0,1 (25) ,81,71 81,71 57,75mod91,6. xy Verification: Indeed, . (26) 4. Numeric Illustration N = 109; m = 27; z = 14. In Table 1 are the quartic roots of unity 1040 57,75 m 2od 91,681,71 Consider p = 10, q = −3. Then m ,cd k (9), i.e., q 1 :1,012,71,0;3,90,1 ;q q 2 3 4 ; 10,20,1mod, R q qpq . Step-by-step process of extraction of the square roo and criteria of quadratic residuosity are illustrated for se ts veral values of ,cd . 5. Quadratic RExoot traction (QRE-2) 5.1. Basic Properties and Where 9mod 16N Proposit ion 8: if 3pmod8 0mod4 q , then able 1. Quadratic root extraction and verification; T mod 8 = 5 . N ,cd (3, 8)(4, 8) (6, 7) (8, −2) (9, 2)(10, 5) ,m cd (1, 0) (10, −2) (−1, 0) (−1, 0) (3, 9)(1, 0) , z cd (9, −2) QNR (5, 3) (11, 4) QNR (2, 2) ,z cd R(9, −2) na (7, 2) (7, −1) na (2, 2) 2 , x y (3, 8) *** (6, 7) (8, −2) *** (10, 5) :1mN 8 is odd and 716N is an integer. Proof Si = + 3 and he : nce p 8w q =4r, terefor 22 16 439Nwwr (2). Hence 16 7N . If we assume that m is even; then 7 7) 1612Nm. (2 Thus, if 2m is integer, then 716N is not (27). This contradiction proves Proposition 8 Proposition 9 {criterion of Gaussian os . quadratic residu- ity}: Let 18 :, mod N Ecd G ; (28) and gcd, ,1cdG . Then ,cd if has a quadratic root e G modulo Gaussian prim ,0;0:1 ,11;iE ; {see the algorithm below}. (29) Proposition 10: Suppose a) p is odd and 0mod4q; (30) b) 716zN ; (31) satisfies the fc) Resolventa Rollowing conditions: 3 1,0mod if 1,0; (32)GE 0,1mod if 1,0; (RGE 33) mod if 0,1; (34)EGE Then ,,mo z cd RcdG.d (35) in (32)-(34) Proof: Notice that 1modRE G . s that If (35) is correct, then it implie d (36) ,,cd Rcd 22mo zG. On the other hand, odG; (37) 218 22 ,,,m zN cd Rcd cdR th ply that erefore (28), (32)-(34) im Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS  B. VERKHOVSKY 290 ords, it confirms as- 5. 2mod ,1ERp q. (38) Hence (36) is correct. In other w sumption (35). Q.E.D. 2. Octadic Roots of 1,0 Modulo ,pq onsider roots of 8th poCwer (called the octadic roots) of roots: 8 unity; there are eight suchfor k = 1, ···, 81,23,4 5,6 7,8 :1,0: 1,0;:0,1; :0,1;:0,1 k eee ee (39) Then 2 e e . (40) Therefore, the resolventa R must satisfy the following equations for k = 1, 2, ···, 8: . (41) if3,4 an (43) 5.3. Computation of 22 213,4 22 5,637,84 1, 0;1, 0; 0,1;0,1 eee eee 1 mod1,0 or mod kk ReGR eG Thus, 1 : if 1,2 kk Re ek ; 132 : kkkkk Reeeeek ; (42) d 17422 0,1 if : 0,1 if 7,8 k kk kkkkkk e R eeeeeeeek 5,6 k. 0,1i Modulo ,pq If is fixed and , then this root Direct computation: Since ,pq mod 169N advance. must be pre-computed in cos π2sinπ2ii cosπ4sinπi41,122, it is necessary to compute square root of two and multi- plicative inverse of two modulo G. 5.4. Multiplicative Inverse of 2 Modulo ,pq f p is odd and q is even, then I 1 212,2mod,pq pq ; if q is odd and p is even, then 1 212,2mod,qp pq . Otherwise the modular inverse of 2 does not exist. then Example 2: Let G = (8, −3); 1 22,4mod8,3 and 25,1mod8,3. Hence 1, 15, 12,42,3mod8,3i [8 deed, ]. In 8 2,31,0mod8,3 . Indirect computation: In general, observe that if square root of 2 does notnd for a Gaussian exist a ,ab houality lds ineq ,mod1,;0,1ab G 18N : 0F , (44) then 18 ,mod or N abG ii . (45) Although in this case we do not directly compute 0,1mod G, it is obvious that if 2mod 0,1FG (44), then 0,1 modiFG ; (46) otherwise 0, 10, 0, 11modiFG . (47) for Quadratic Root Extraction Step 1.2: 5.5. Algorithm 22 :; :18; 716mNNp Nqz (48) Step 2.2: if N is not a prime, then the QRE-2 algo- rit plicable; Step 3.2: Find a Gaussian for which hm is not ap ,ab, :, mod1,0;0,1Fab G; (49) Step 4.2: if m , 20,1F m:oRF iG then d; if 20,1F , then m:0 odRFiG ,1; ( Step 6.2: if Step 5.2: Compute :, mod m Ecd G; 50) 1, 0;0,1E (22), then square root of ,cd does not exist; E = (1,0), then ,: ,mod z Step 7.2: if x ycdG; goto Step 10.2; Step 8.2: if 1, 0E , then ,: mo0d,1 z , x yc G; goto Step 10.2; d Step 9.2: if 0,1E, then ,: , 0,1 modR z x ycdG; goto Step 10.2; (51) else (52) Step 10.2 {2nd square root}: ,: modxy G; ,z cd R ,:1,,modtvpq xyG . (53) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS  B. VERKHOVSKY Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS 291 6. Second Numeric Illustration C= 73, i.e., 41,0mod, 1,2,3,4. j qGj (56) onsider ,8,3pq, then N Definition 4: is a octadic root of if k e 1, 0 739mod16; 9; 5;mz (54) 81,0mod, 1,2,,8. k eGk (57) Octadic roots of 1, 0: Definition 5: l s is a sedonic root of if 1, 0 2 110,51,0;e 16 1,0mod, 1,2,,16. l sGl (58) 2 10,51,0mod8,3e ; 7.2. Resolventa of Quadratic Root Extractor 2 3 8,2; e 10, 58,20,1; Proposition 12: Suppose 2 4 3,710,5; 3,70,1e ; a) 7mod16 and 0mod8pq , (59) 2 5 2,38,2; 2,30,1e ; b) 22 :; 1532; :116Lc dzmNN (60) 2 6 9,28,2; 9,20,1e; c) Let ; and resolventa R satis- fies the following conditions: :, mod, m Ecd pq 2 7 5,13,7; 5,10,1e; 1 :mod if ii Ruu GEu ; i (61) 2 8 6,63,7; 6,60,1e. The following nine values of 13 :mod if j; j j Rqq GEq (62) ,cd rithm. in Table 2 illus- trate various cases of QRE-2 algo 7. Quadratic Root Extraction (QRE-3) .1. Basic Property and Roots of Where 17mod 32N 17 :mod if kkk Ree GEe ; (63) 115 :mod if ll Rs s GEs ; l (64) then ,,mo z cd RcdG d. (65) 1, 0 7 Proposition 11: Anroved th 7 mod8 Proof: Let alogously it can be pat if and , then ,, ,:m z od x ycdRcdG . (66) 16p 0modq 15 3 2 N is integer and 6:11mN is odd. ; then i.e., Therefore Proof: Let 16 7pk and 8qr 15 1622 ,, N cdRcd ERG mod. (67) 32872 49Nkk , 32 15N. If i Eu , then Notice that 15 322 . On the other hand, if m is even, en 1Nm th 12m is not an inte im ger, which 222 1, 0mod i ERE uG ; (68) 15 32N plies that is noteger. Q.E Definition q ua re r 1, 0 if an int.D. 2: is a sot of i u oif j Eq , then 21,0mod, 1,2 ii 244 1, 0mod j ER E qG ; (69) .uG (55) Definition 3: is ic root of 1, 0 if if k Ee , then a quart j q Quadoot extractor where 9mod 16N. Table 2.ratic r ,cd (1, 1) (3, −1) (5, 1) (5, 5) (7, −1) (8, 5) (10, 3) (3, 4) (4, 3) ,m cd (2, 3) (0, 1) ) (0, −1(0, −1)(1, 0) (0, 1) (9, 2) (8, −2) (−1, 0) , z cd na ((8, 1) 8, 5) (3, 6) (5, 7) (1, 2) na (3, −1) (9, 19) ,z cd Rna (4, 5) (9, 4) (4, 1) (1, 2) (5, 4) na (2, 2) (7, 6) 2 , x y na (3, −1) (3, 4) (4, 3) (5, 1) (5, 5) na (8, 5) (10, 3) 58 ,,Ee eNB1: If , then QRE-2 algorithm is not applicable, since the square roots of do not exist. 58 ,,ee  B. VERKHOVSKY 292 1, 0 ; 288 mod k RE eGE ( if , the ( .3onic Roots of 70) l Esn 1, 0 21616 mo l ER Es dG. 71) 7. Sed 1, 0 Modulo G ity wo square rootsUn 0 has t 1, 1, 0and1, 0; 0,1; 0,fouroots ctadi quartic r c roots 1,0; 1,0; 1; eight o 5678 ; 0,1;,,,eeee1,0;1,0; 0,1 and sixteen sedonic roots 5678910 1516 1 ,,,,es s, 1, 0;1, 0;0,1;0,,,,,,eeess where 5,6 0,1 ,e 7,8 13,14,15,16 0,1 and 0,1. e s (72) d Numeric Illustration Consider N = 113; 7. Then 9,10,11,12 0,1 ,s 7.4. Thir ,8,pq :1167; mN :1zN w 5324. In Table 3 belo ; 1,014, 1 0,18,6 ; 0, 1(7,7)mod8, 7 ; 6,5 ; 0,1 0, 19,4; 0,13,1 ; 0 mo ,112, 2d8,7 ; 1 0,5;12, 2;10, 2;5, 2mod8, ; (73) 0, 1 7 0, 1 5, 4;3,3;5,3;10,3mod8, 7 . (74) In (74) there are four sedonic roots of (1,0) that be pre-computed on the design stage of the QRE-3 algo- rithm. Although this is a non-deterministic process, each of these roots must be computed only once prior thctose roots crresp must to using e extrar. Theoond to mod , 1,0 m gh G, w = 7 16 :E here m; ,8,pqG 7 and Gaussians 6 4. ,: ;10,1;11gh ,3 ,3;5, The remaining four sedonic roots li equivalent to negative values of roots in (7 sted in (73) are 4): 10,55, 4;12,23,3;1,2 5,3;5,21 0,3 0 . Step 1.3 {System design}: Every user (Alice, Bob,…) selects a pair of Gaussian primes and 8. Cryptographic Algorithm ,pq rs , as his private keys, and computher/es ,qrs 22 q , :,np Np es as m, Step 2.3 {Generalized Chinese remainder Theorem m . her/his public key; she/he pre-comput z and R; odulo composite Gaussian n}: Each user pre-computes his/her parameters of CRT: 11 :,mod,; :,m od, M pqrsWrs 75) Step 3 pq ( .3 {Encryption by sender (Alice)}: Alice repre- sents the plaintext as an array of Gaussians and inserts digital isotopes into every Gaussian ,ab [3]; Step 4.3: Using Bob’s public keye computes ci- phertext roots of C mod n, sh 2 :,modCab n; (76) and transmits C to receiver (Bob) via open channels of a communication network; Step 5.3 {Decryption by receiver (Bob)}: He com- putes square ,pq and mod ,rs , where ,pq and ,rs he CRT are Bob’s p d his pre-com rivate keys; Step 6.Using t an Table 3. Binary tree of sedonic roots of 3: puted M and W (75), Bob computes all quadratic roots of ciphertext C; Step 7.3: Bob recovers the initial plaintext {by select- 1, 0 where modulus 8, 7G. ,gh (6, 3) * (10, 1) * * (11, 3) * (5, 4) * 16 1, 0E (5, −4) (10, 5) (3, 3) (12, −2) * (5, 3) (10, −2) (10, 3) (5, −2) 281, 0E * (6, 5) (9, −4) * * * (3, −1) (12, 2) * 441,0E * * (7, 7) * * * (8, −6) * * 81, 0E * * * * (−1, 0) * * * * * * * * (1, 0) * * * * 16 E NB2: For the sake of brevity, only 1/2 of all roots are listed in every row of Table 3; all remaining roots are listed in the rows below. For instance, 81,06,5;9,4;3,1;12,2; and 7,7;8,6; and 1,0; and 1,0. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS  B. VERKHOVSKY293 Table 4. Residuespplicaare rooxtractornd exams of coding N N mod 32 59 13 , able squt es aplerrespon. 17 21 25 29 QRE QR E-2 QRE-1 Q E-1 QRE-2 QREE-1 QR RE-3 QR-1 N1260773 692969 432589 386641 612373 525913 906557 5, 496) (113, 498) (212, 805) (258, 605) (37 (522, 583) (157, 708) (421, 854) N2 750077 (35130) (16,9) (274) (469) (179) (485) (116) ,pq 812101 249257 360781 676337 159157 405529 ,pq , 8 495, 534, 674, 35, 63, 86 ing the quratic rootat has sotope This algorithm is a gn cryp graphic algothm [h eme sq algorithmr encrypecryf real modulo semi-prime , where are primes. . Reduction of Computational Complexity ad of C th eneralizatio digital i of the Rabin s [9]}. to- ri10], whicploys thuare root fotion and d npq ption o p and q integers 9 In Step 3.1 (12) and Step 4.1 (13), two exponentiations are performed to compute ,cd to the powers m an d z respectively; these operations are the most time-con- suming. However, observeere is a simple linear rela- that th tionship between m and z: 21 154zm N . (77) This implies that it is sufficient to execute only one exponentiation. Indeed, we initially compute 1 1:, mod z A cd G ; {one exponentiation}; (78) then 1 21 2 2mod:, z AA cdG ; {one nally squaring}; (79) after that 32 :,, m AA cdcd ; {one multiplication}; (80) and fi 41 :,, z AA cdcd ; {one multiplica- tion}. icability of QRE Algorithms Consider , wh o integer squares. For such N his paper tion of (81) 10. Appl :mod 32AN be represented as a sum of tw A ere N are primes, which can the residues are equal 21,25 and29 Table 4 above indicates which algorithm is applicable r each value of residue A. :1,5,9, 13, 17,. fo Therefore, the three algorithms provided in t over all cases of prime moduli with the excepc od32N case can still be cov prim 1m . Yet, ered most moduli latter if we coner QR rithms, of the sid in the E algo where the es od 64; 33Nm 128N; the als de- 65 mod ageneralnd in d , for integer 5t gorithm es wherescribeabove can be generalized for the cas t, 1 mod2 t 21N (82) en component and the ev in the corresponding modulus ,pq is divisible by 1 2t . 11. Conclusion and Acknowledgements Th d and y ncryption/ecrtion protocol based I appreciate S. Medicherla, S. Sadi n onynd typesetter for their sugges- - ree algorithms which extract square roots of Gaussians in arithmetic, based on Gaussian modulo reduction, are considere analyzed in this paper. Several numeric illustrations provide further explanation of these algo- rithms. A public keedyp on this arithmetic is described in the paper. This crypto- graphic protocol is almost twice as fast as the analogous protocols published by the author of this paper in [3,4]. k and B. Saraswat for assistance in numeric illustrations and my gratitude to J. Joes, A. Koval, M. Linderman, R. Rubino and mous reviewers athean tions that improved this paper. 12. References [1] C. F. Gauss, “Theoria Residuorum Biquadraticorum,” 2nd Edition, Chelsea, New York, 1965, pp. 534-586. [2] M. Kirsch, “Tutorial on Gaussian Arithmetic Based on Complex Modulus,” 2008. http://wlym.com/~animations/ceres/index.html [3] B. Verkhovsky, “Information Protection Based on Ex- traction of Square Roots of Gaussian Integers,” Interna tional Journal of Communications, Network and System Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2011, pp. 133-138. doi:10.4236/ijcns.2011.43016 [4] B. Verkhovsky and A. Koval, “Cryptosystem Based on Extraction of Square Roots o Latifi, Ed., Proceedings of 5 f Complex Integers,” In: S. th International Conference : New Generations, Las Vegas, on Information Technology Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS  B. VERKHOVSKY 294 7-9 April 2008, pp. 1190-1191. A, rs: A com- 001. ariables and Applications,” 3rd Edition, McGraw n In- [5] E. Bach and J. Shallit, “Efficient Algorithm,” Algorithmic Number Theory, Vol. 1, MIT Press, Cambridge, M Hil 1996. [6] R. Crandall and C. Pomerance, “Prime Numbe putational Perspective,” Springer, New York, 2 [7] R. Schoof, “Elliptic Curves over Finite Fields and the Computation of Square Roots Mod p,” Mathematics of Computation, Vol. 44, No. 170, 1985, pp. 483-494. [8] R. V. Churchill, J. W. Brown and R. F. Verhey, “Com- plex V l, New York, 1976. [9] B. Verkhovsky, “Cubic Root Extractors of Gaussia tegers and Their Application in Fast Encryption for Time-Constrained Secure Communication,” International Journal of Communications, Network and System Sci- ences, Vol. 4, No. 4, 2011, pp. 197-204. doi:10.4236/ijcns.2011.44024 [10] M. Rabin, “Digitized Signatures and Public-Key Func- tions as Intractable as Factorization,” MIT/LCS Technical Report, TR-212, 1979. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS  B. VERKHOVSKY295 Appendix A1. Classification of Roots of 1,0 Modulo ,pq There are various types of unary roots: Definitions and notations: 11 :1,0mod, ,Spq 112 ss; (A.1) where 11 :1,0mod(,)Ppq 1 p (A.2) is the set of principal square roots of (1,0) of the first level. Then 21 :mod,, k Ss pqk1,2; (A.3) where 2112 :mod,; k Ppp pqk 1,2; (A.4) is the set of principal square roots of (1,0) of the second level. In general, 1, :mod iik Ss p ,q; (A.5) where 1, :mod, iik Pp pq (A.6) is the set of principal square roots of (1,0) of the i-th level. A2. Criterion of Quadratic Residuosity and General Algorithm Proposition 1.A: Let . 1 mod 221 kk N If and only if 1 12 1 :, mod k k N Ecd GS , (A.7) then has a square root. In this case ,cd 1 :moRE dG; (A.8) and 1 212 mo,d, kk N xy RcGd . (A.9) A3. Quadratic Extractor Modulo ,1n Proposition 2.A: Let ,1Nn be a prime; mod41, but mod81.NN (A.10) If the norm of is co-prime with N, then square root ,cd , x y of is equal ,cd 248 ,,mod n xyRcdn where 21 /4 ,mod, n Rcdn 1 . (A.12) Proof: First of all, if 21Nn is a prime integer, then n is even. Therefore (A.10) implies that 24n and 248n are integers. Then (A.11) and (A.12) imply that 2 24 2 ,,,,mod n xyR cdcdcdn,1. 1 (A.13) Since the cyclic identity (4) implies that 2 ,1,0mod, n cd n , then potentially 24n ,mod,11,0;0,1;0,1.cdn (A.14) Therefore, 2 2 2 2 4 4 4 4 1,0 if ,1,0; 0,1 if ,1,0; 0,1 if ,0,1; 0,10,1 if ,0,1. n n n n cd cd Rcd cd (A.15) Since 0,11,122 mod,1n {see Subsec- tions 5.3}, then R does not exist if 2 does not exist [1,6]. Therefore ,cd is the Gaussian QNR [3]. For more details see (32)-(34), (A.11), (A.12), Subsection 5.4 and eight examples in Table A1. Remark A1: Here 1, 9and10, 0 are quartic roots of 1, 0 modulo 10, 1. Indeed, od 10,1; 310,,1mq0 0 od 10,1; 41,91mq 0, (9) 32 mod10,1;qq 42 10,9.qq 2 ,0 2 9 210 1,0 21,1, 0 A4. Special Cyclic Identity Proposition 3.A: If :,Npq is prime, then 1 ,1,0mod, N qp pq . (A.16) Remark A2: Although ,,pq qp, identity (A.16) holds because ,pq and ,qp are co-prime. Indeed, assumption that w q ,, ,mod,up pqpq, where both u and w are integers, implies that and mod,.upqNwqpNpq (A.17) However, (A.17) is impossible since the inverse of N odulo ,1; (A.11) m ,pq does not exit. s Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS  B. VERKHOVSKY Copyright © 2011 SciRes. IJCNS 296 Table A1. {Quadratic root extraction where mod 41N and mod 81N }: , n ; 2 :22mn5; :12zm+. ,cd (2,0) (3,2) (4,8) (6,7) (7,4) (9,2) (9,9) (10,1) 2 /2 ,n cd (0, −1) (−1, 0) (1, 0) (−1, 0) (−1, 0) (0, 1) (0, 1) (−1, 0) ,z cd GQNR (9, 4) (6, 3) (6, 9) (5, 8) GQNR GQNR (9, 0) R na ±(10, 0) (1, 0) ±(1, 9) ±(10, 0) na na ±(1, 9) ,, z xy cd R na ±(6, 8) ±(6, 3) ±(1, 5) ±(2, 4) na na ±(10, 8) 2 , x y *** (3, 2) (4, 8) (6, 7) (7, 4) *** *** (10, 1) i.e., 1; x ynxy r . Example 1.A: , although 28 4,10mod5,21, 0 Hence gcd4,10,5, 2291 . 12; 12xnrynr . (A.22) Corollary 1A: If gcd,,,1, 0stpq , then Therefore, (A.20) and (A.22) imply 1 ,, 1,0mod, N s tqp pq (A.18) 11 1 ,,1,1 1,1 ,1,1 1,0 mod,.Q.E.D. rn rnnrnr rn nrnrnr nr 1 2 Proposition 4.A: If n and r in modulus ,nr have different parities, then multiplicative inverse of exists and equals , modulo ,rnn r (A.23) 1 1 , 1,1 2mod,. rn nr nrnrnr Example 2.A: Let n = 10, r = 3. Then . 11 3,1074,72,14,78,3 (A.19) Indeed, 3,108,31, 0mod10,3 . Proof: First of all, ,nrCorollary 2A: If n and r in modulus ,1,1mod,rnn rnr . (A.20) have dif- ferent parities and there exists multiplicative inverse of ,ab, then multiplicative inverse of ,,mod,ab nrrn also exists. Now let’s find integers x and y such that 1,1,1, 01,mod, x ynrn r (A.21) |