Journal of Environmental Protection, 2011, 2, 221-230 doi:10.4236/jep.2011.23026 Published Online May 2011 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 221 Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review Joseph R. Fianko1,4, Augustine Donkor2, Samuel T. Lowor3, Philip O. Yeboah4 1Department of Chemistry, NNRI/GAEC, Legon, Accra; 2Department of Chemistry, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra; 3Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana, Akim Tafo; 4School of Nuclear and Allied Sciences, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra. Email: jrfianko@yahoo.com Received August 18th, 2010; revised Janaury 17th, 2011; accepted February 22nd, 2011. ABSTRACT Agrochemicals are generally recognized as a significant factor in enhancing the ability to meet Ghana’s need for suffi- cient, safe and affordable food and fiber, however, increased usage have led to environmental deterioration. In Ghana agriculture and public health sectors remain the major contributors of pollutants into the environment. This is a sys- tematic review of studies done in Ghana to give an integrated picture of agrochemicals especially pesticides exposure to humans, animals, plants, water, soil/sediment and atmosphere in Ghana. Although the widespread usage of agro- chemicals in Ghana has contributed immensely to increased food supply and improvement in public health, it has caused tremendous harm to the environment. Water bodies, fish, vegetables, food, soil and sediment have been found to be pesticide contaminated. There is considerable evidence that farmers have overused agrochemicals especially pesti- cides. It is evident from biological monitoring studies that farmers are at higher risk for acute and chronic health ef- fects associated with pesticides due to occupational exposure. Furthermore the intensive use of pesticides involves a special risk of for field workers, consumers and unacceptable residue levels in exportable products may serve as bar- rier to international trade. This review will set the future course of action of different studies on agrochemical usage and pesticide exposure in Ghana. Keywords: Ghana, Agrochemicals, Environment, Pollution, Exposure 1. Introduction Agrochemicals are integral part of current agriculture production systems around the world. Accordingly, the use of agrochemicals viz fertilizers and pesticides remain a common practice particularly in many nations in the tropical world [1]. Pesticides like 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis (4-chlorophenyl) ethane (DDT) and 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexa- chlorocyclohexane (HCH) which are environmentally persistent prohibited from use in developed nations con- tinue to be most widely used pesticides in developing countries including Ghana because they are cheap, easy to synthesis or they are given by developed nations. Many pressure groups, example, Consumer Associations, Non-governmental Organizations and International bod- ies are against the presence of these persistent pesticides in the environment. They perceive the presence of pesti- cide residues in the environment as detrimental to human health and water quality. The contamination of the environment and exposure of the public to pesticide residues in food could lead to high health risk. Results of scientific research reveal that even in low concentrations, the combined effect of persistent synthetic chemicals such as pesticides causes suppression of immune response and hypersensitivity to chemical agents. Causes of breast cancer, reduced sperm count, male sterility etc are well documented as a result of pes- ticide ingestion [1]. Death cases and pesticide poisoning have been reported around the world particularly in de- veloping countries [2]. In Ghana, agrochemicals used in farming dates back to the colonial era and have been in- herent component in agricultural practices in the nation. The objective of this review is to summarize the agro- chemical monitoring studies in Ghana and gives the true picture of their detrimental effects to the environment. It will also determine the current state of knowledge in ag- rochemicals in Ghana to set the future plan of action in agrochemical research in Ghana. 2. Agro-Chemical Use in Crops in Ghana Agriculture is the most important sector in Ghana’s economy, forming nearly 41% of total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [3]. Out of the total area of 238.854  Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review 222 square kilometers of Ghana only 57% (13 628 000 hec- tares) is suitable for agriculture. However, 6 331 000 hectares of the arable land are cultivated because the soils are infertile and only productive with proper management and good agricultural practice [4,5]. In the light of these and the need to increase food supply, the use of crop protection chemicals, organic fertilizers, improved water and soil management as well as increased area of agri- culture land seems the simplest way to obtain better yield. Instead, the current trend has been the decrease of agri- culture land (hectares per inhabitant) in all regions of the globe as a result of population growth, net loss of agri- cultural land due to erosion, reduction of fertility, salini- zation and desertification of soils [1]. Therefore the best response to the need for increasing food production is more intensive use of agrochemicals. As farms have become massive in size, the challenges in keeping the crop free of damage have increased. Hand-tilling weeds have become impractical, as one example. Thus the whole world has known a continuous growth of agrochemical usage both in numbers and quantities. The use of agrochemicals has been critically important in increasing the yield of agricultural crops. However, some uses of agrochemicals cause environ- mental and ecological damage, which detracts signifi- cantly from the benefits gained by the use of these mate- rials. The most commonly used fertilizers are inorganic compounds of nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P) and potas- sium (K). In Ghana, agro-chemicals are used in cocoa, oil palm, cola nut, coffee and cotton farms, vegetable (e.g. tomato, eggplant, onion, pepper, okra, cabbage, lettuce, carrot) and fruit production (e.g. papaya, citrus, avocado, mango, cashew, pineapple), mixed-crop farming systems involv- ing cereals (e.g. maize, millet, sorghum, rice), tuber crops (e.g. yam, cassava, cocoyam, sweet potato) and legumes (e.g. cowpea, bambara nut, groundnut, soybean). Overall, agrochemical especially fertilizer use on pineapple is fairly high because pineapple is grown on sandy soils. 3. Fertilizer Use in Ghana The use of chemical fertilizers has increased tremen- dously worldwide since the 1960s and is largely respon- sible for the green “revolution” i.e. the massive increase in production obtained from the same surface of land with the help of mineral fertilizers (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) and intensive irrigation [1]. At present, Ghana does not manufactured fertilizers; all fertilizers used in Ghana are imported [1]. The major importers of fertilizers into Ghana are private companies, Agricultural Devel- opment Bank and some commercial farms. The most important imported products are compound fertilizers Ammonium Sulphate (AS) and Muriate of Potash (MOP) with urea, Single Super Phosphate (SSP) and Triple Su- per Phosphate (TSP) being minor imports (Table 1) [3]. Compound fertilizers accounted for 48 percent of the total amount of fertilizers consumed in Ghana between 1995 and 2003 with nitrogenous fertilizers (urea and ammonium sulphate) accounting for 30 percent of the total fertilizers consumed. The consumption of fertilizers fell substantially in the early 1980s because of adverse economic conditions; nonetheless, it increased in the second half of the 1990s following an improvement in the national economy, ever since it has been steady (Ta- ble 2). The Upper East and the Upper West Regions are Table 1. Fertilizer imports into Ghana (“000 tonnes”). Year N.P.K (15-15-15) Other Compounds Urea MOP AS SSP/TSP & others Total 1997 19.2 17.9 1.9 5.5 10.7 1.1 56.3 1998 13.1 8.8 0.5 3.1 13.3 3.6 42.4 1999 3.2 0.4 0 8.1 4.8 5.5 22.0 2000 14.1 0.8 0.1 4.5 23.2 0.8 43.5 2001 31.8 17.5 2.5 4.1 22.6 2.3 80.8 Table 2. Mean fertilizer consumption by region in Ghana. 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Region (tonnes) Ashanti 5167 3893 2023 4046 7438 Brong Ahafo 7582 5712 2969 5937 10,914 Central 1629 1229 638 1275 2345 Eastern 1011 762 396 792 1455 Greater Accra 1236 931 484 967 1779 Northern 15,220 11,467 5960 11,917 21,910 Upper Regions 15,501 11,679 6070 12,137 22,314 Volta 8481 6390 3321 6640 12,208 Western 337 254 132 264 483 Total 56,164 42,317 16,593 43,975 80,846 Source: [4,5] Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review223 the largest fertilizer consumers in Ghana. The Upper East Region has two large irrigation schemes at Tono and Vea. Because of the high economic value of tomatoes and onions during the dry season, farmers regularly tend to apply more fertilizers to these crops, hence the increased volume of fertilizers usage in the Northern sector. Pesticide Use in Ghana: Ghana is a developing coun- try experiencing high economic growth rate in the West African Sub-region [3]. As an agriculture-based nation, the use of pesticides contributes much to the national development and public health programmes. Ever since the inception of pesticides, its use to protect crops from pests has significantly reduced losses and improved the yield of crops such as cereals, vegetables, fruits and other crops. Ghana thus, has known a continuous growth of pesticide usage, both in number of chemicals and quanti- ties because of the expansion of area under cultivation for food, vegetables and cash crops [4]. Pesticide application in Ghana is more concentrated in cocoa, oil palm, cereals, vegetables and fruits sectors. Although purchased physical inputs (agrochemicals, seeds and tools) represent less than 30% of the total cost of crop production, the use of pesticides is becoming more widespread. For instance, between 1995 and 2000, about 21 different kinds of pesticides were imported into the country for agricultural purposes [5]. Its use has been embraced by local communities that are making a living from sale of vegetables and other cash crops. There is ample evidence that this products especially tomatoes are always sprayed and sold immediately after maturity for consumption. This inevitably puts a high risk on con- sumers who always get their supply directly from the farmers. In Ghana, it is estimated that 87% of farmers who use pesticides, apply any of the following or a com- bination of pyrethroids, organophosphates, carbamates, organochlorines on vegetables [6]. Among the different types of pesticides known, or- ganochlorine pesticides are the most popular and exten- sively used by farmers due to their cost effectiveness and broad spectrum activity. Lindane was widely used in Ghana on cocoa plantations, vegetable farms, and for the control of stem borers in maize [7]. Endosulfan is popu- larly applied in cotton growing areas, vegetables farms, and coffee plantations [5] in some parts Ghana. Pesti- cides particularly DDT and lindane which are no longer registered for any use in the country were once employed to control ecto-parasites of farm animals and pets in Ghana [8]. Pesticides mostly used to control foliar pests of pine- apple in Ghana include chlorpyrifos, dimethoate, diazi- non, cymethoate and fenitrothion while the fungicides maneb, carbendazim, imazil, copper hydroxide are used for post-harvest treatment [9,10]. Lambda-cyhalothrin, cypermethrin, dimethoate and endosulfan are also used by vegetable growers in tomato, pepper, okra, egg-plant, cabbage and lettuce farms. Glyphosate, fluazifop-butyl, ametryne, diuron or bromacil are normally employed in land clearing [11]. Nonetheless, the most extensively used pesticides in the pepper, tomato, groundnut and beans cultivation are karate, cymbush, thiodine, diathane, lubillite and kocide [12]. Dinham [13] estimates that 87% of farmers in Ghana use chemical pesticides to control pests and diseases on vegetables and fruits. Ntow et al. [8] gave the propor- tions of pesticides used popularly on vegetable farms as herbicides (44%), fungicides (23%) and insecticides (33%). In a study encompassing 30 organized farms and 110 kraals distributed throughout the 10 regions of Ghana, Awumbila and Bokuma [14] found that 20 dif- ferent pesticides were in use with the organochlorine lindane being the most widely distributed and used pesti- cides, accounting for 35% of those applied on farms. Of the 20 pesticides, 45% were organophosphorous, 30% were pyrethroids, 15% were carbamates and 10% were organochlorines [14]. In the public health sector, pesticides, primarily te- mephos have been used by the Onchocerciasis Pro- gramme in the Volta Basin for the control of black flies (Simulium spp. Diptera: Simulidae), which transmit Onchecerciasis (African river blindness, a disease caused by the pathogenic nematode, Onchocerca volvulus) to humans and for the control of diseases [15] and domestic pests, such as cockroaches, various flies, mosquitoes, ecto-parasites including ticks and other insects [16]. Pes- ticides have also been used to control black flies along the banks of the Tano and Pra rivers [17]. Analysis of pesticide trade flow patterns, recorded by Ghana’s Statistical Service, in 1993 indicated that a total of 3,854,126 kg of pesticides were imported with the following distribution and use as per Figure 1 [18]. Be- sides, a survey conducted between 1992 and 1994 in the Ashanti, Brong Ahafo, Eastern and Western Regions of Ghana revealed that the most broadly used pesticides by farmers are: copper(II) hydroxide (29.0%), mancozeb (11.0%), fenitrothion (6.0%), dimethoate (11.0%), pirimi- phos methyl (11.0%), λ-cyhalothrin (22.0%), and endo- sulfan (10.0%) [19]. Moreover, it was established that insecticides constituted about 67% of pesticides em- ployed by farmers while fungicides were about 30% and herbicides and other pesticides types form 3% of the total use. On the other hand, it is on record that between 1995 and 2000, an average of 814 tons of pesticides was im- ported into the country annually, the greatest quantity being insecticides, 70% [5]. The amount of pesticides imported into the country from 2002 to 2006 increased Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review 224 from 7763 metric tonnes to 27,886 metric tonnes, (Table 3). Updated register of pesticides from the Environ- mental Protection Agency in Ghana in 2008 indicated that about 141 different types of pesticide products have been registered in the country under the Part II of the Environmental Protection Agency Act, 1994 (Act 490). These consists of insecticides (41.84%), fungicides (16.31%), herbicides (0.43%) and others (0.01%) [20]. 4. Pesticides in Surface and Ground Water A fundamental contributor to the “Green Revolution” has been the development and application pesticides for the control of a wide variety of pests that would otherwise diminish the quantity and quality of food produce [2]. Notwithstanding the increased food production, massive use of pesticides has caused serious contamination of aquifers and surface water bodies, decreasing the quality of water for human consumption [1,21]. Pesticide resi- dues have been a catch cry of environmental and con- sumer groups since the mid-1960’s when Rachel Carson [22] drew the public’s attention to the deleterious eco- logical effects of organochlorine pesticides especially 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis-(4’-chlorophenyl) ethane (DDT), which were in widespread use at that time. Water samples from rivers in the intensive cocoa growing areas in the Ashanti and Eastern Regions of Ghana have been found to contain lindane and endosul- fan [23]. Water samples from Akumadan, a vegetable farming community in the Ashanti Region and different areas of Ghana revealed the presence of significant levels of pesticide residues (Table 4). The Volta Lake was also found to be mildly contaminated with lindane, DDT, DDE and endosulfan [17]. In Oda, Kowire and Atwetwe rivers in Ghana, mean pesticide concentrations found in water samples for lindane and endosulfan were 19.4 and 12.4 µg·L−1 (Oda), 16.4 and 17.9 µg·L−1 (Kowire) 20.5 and 21.4 µg·L−1 (Atwetwe), respectively [23]. Figure 1. Distribution of pesticides imported into Ghana in 1993. Table 3. Annual imported pesticides into Ghana from 2002 to 2006. Metric Tonnes Class of Pesticide 20022003 2004 2005 2006 Insecticides 41305974 8418 10,00612,728 Herbicides 2186 2939 4578 856610718 Fungicides 1079 1249 2402 2205 3195 Others 368 496 544 707 1224 Total 776310,658 15,942 21,484 27,886 Table 4. Pesticides detected in water samples from different areas of Ghana. Area Detected Concentration(µg·L−1) Freq. of detection Reference Lindane 9.5 76 [24] α-endosulfan 62.3 64 β-endosulfan 31.4 60 Akomadan Endosulfan sulfate 30.8 78 Lindane 0.008 22.8 [17] α-endosulfan 0.036 15.6 β-endosulfan 0.024 17.8 Endosulfan sulfate 0.023 10.6 P,p-DDT Volta Lake P,p’-DDE Lindane 0.071 [24] Endosulfan 0.064 DDE 0.061 82 Bosomtwi Lake DDT 0.012 78 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review225 5. Pesticides in Food Effects of pesticides have been reported in milk, vegeta- bles, fruits, meat, fish meal and other food at different intervals in the country. Analysis of street-vended food samples in Accra, between 1999-2000 revealed disturb- ing levels of contamination by pesticides, heavy metals, microorganisms and mycotoxins [23]. The pesticide chlorpyrifos was detected in six out of eight samples of waakye (rice and beans) and one out of eight samples of fufu (cassava and plantain dough). Vegetables on the Ghanaian market were found to contain detectable levels of chlopyrifos, lindane, endosulfan, lambda-cyhalothrin, and DDT residues in lettuce, cabbage, tomato and onion [6,25,26]. Significant amount of different pesticides have been reported for other foods besides that in vegetables and fruits (Table 5). The possible reason for pesticides to Table 5. Pesticide residues in different foods in Ghana. Area Commodity Detected Concentration (µg·kg−1) Reference Kumasi abattoir Beef fat Lindane 4.04 [24] endosulfan 21.35 Aldrin 2.06 DDE 118.45 DDT 545.24 dieldrin 5.25 Beef Lindane 2.07 endosulfan 1.88 Aldrin 1.43 DDE 42.93 DDT 18.83 dieldrin 5.92 Buoho abattoir Beef fat Lindane 1.79 endosulfan 2.28 Aldrin 4.11 DDE 31.89 DDT 403.82 dieldrin 6.01 Beef Lindane 0.60 endosulfan 0.59 Aldrin 0.73 DDE 5.86 DDT 10.82 dieldrin 11.48 Kumasi Cheese DDE 31.50 Yoghourt DDT 42.17 milk DDT 12.53 Endosulfan sulfate 10.6 Bosomtwi Lake fish Lindane 0.126 Endosulfan 0.713 DDE 5.23 DDT 3.64 Aldrin 0.018 dieldrin 0.035 Kumasi Vegetables Chlorpyrifos-methyl 94.0 Chlorpyrifos 153.5 Dichlorvos 86.5 Dimethoate 117.5 Malathion 209 Monocrotophos 61.5 Omethioate 61 Parathion methyl 31 parathion 71 Kumasi Lettuce Lindane 300 [25] Lambda Cyhalothrin 500 DDT 400 Chlorpyrifos 1600 Endosulfan 400 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review 226 reach these aquatic environments is through direct runoff, leaching, careless disposal of empty containers, equip- ment washing etc which is evident from literature [2]. Studies on pesticide residues in exportable quality cocoa beans collected from selected cocoa growing districts in the middle belt of Ghana and the two shipping ports at Tema and Takoradi also showed detectable amount of lindane residues; the average level was about 10% of the maximum residue level of 0.1 µg/g permitted by Codex Alimentarius Commission [27]. Nonetheless, many other studies conducted so far have revealed the presence of detectable levels of pesticides especially organochlorines in fruits, vegetables, fish and fish products [12,27,28]. The studies pointed out that majority of the samples contaminated by chlorinated pesticides exceeded the maximum residue limits which could cause pesticide hazard to the consumer. 6. Pesticides in Soils and Sediments The natural processes that govern that fate and transport of agrochemicals especially pesticides in the environ- ment can be grouped into the broad categories of runoff, leaching, sorption, volatilization, degradation and plant uptake [29]. Once applied to soil, a number of things may happen to an agrochemical [30]. It may be taken up by plants or ingested by animals, insects, worms, or mi- croorganisms in the soil. It may move downward in the soil and either adheres to particles or dissolve. The pesti- cide may vaporize and enter the atmosphere, degrade via solar energy or break down via microbial and chemical pathways into other less toxic compounds. Pesticides may leach out of the root zone or wash off the surface of land by rain or irrigation water, eventually ending in the sediments through the water column. Evaporation of water at the ground surface can lead to upward flow of water and pesticide [30]. The fate of pesticides applied to soil depends largely on two of its properties: persistence and sorption [1,2,29]. Two other pathways of pesticide loss are removal in the harvested plant and volatilization into the atmosphere, which subsequently impact water, sediment, soil, and air quality negatively and creating problems for agricultural workers who could be pesticide intoxicated via inhala- tion at the treated areas. The sources of all these con- tamination are the consequences of human activities like domestic, industrial discharges, agricultural chemical application and soil erosion due to deforestation. Ac- cordingly, high concentrations of pesticide residues in harvested produce could have ecological health impacts on consumers. However, in the case of fish subsequent accumulation in biota could occur through bioaccumula- tion and biomagnifications through different trophic lev- els in the aquatic food chain. Studies in Ghana [17,24,31,32] have reported the de- tection of different kinds of pesticides especially or- ganochlorines in soil and sediment in different parts of Ghana (Table 6). The fate of propoxur residues in cocoa ecosystem studied revealed that no residue of propoxur could be detected after 21 days after spraying [33]. Glover-Amengor et al., [31] and Nuertey et al., [32] Table 6. Pesticides detected in soils/sediments in Ghana. Area Detected Concentration (µg·kg−1) Frequency of Detection (%) Reference Lindane 3.20 95.2 [6] α-endosulfan 0.19 95 β-endosulfan 0.13 88 Endosulfan Sulfate 0.23 97 HCB 0.90 90.5 Heptachlor 0.63 97.6 Akomadan (Soil) DDE 0.46 88.1 Lindane 2.30 91.7 [17] α-endosulfan 0.21 86.1 β-endosulfan 0.17 88.9 Endosulfan Sulfate 0.36 94.4 P,p-DDT 9.00 22.2 Volta Lake (Sediment) P,p’-DDE 52.30 97.2 Lindane 6.76 [24] Endosulfan 9.68 DDE 8.34 98 DDT 4.41 Aldrin 0.065 Bosomtwi Lake (sediment) Dieldrin 0.072 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review227 measured the effect of excessive use of pesticides on biomass and microorganisms in oil palm and vegetable agro-ecosystems. They observed that the pesticides in- hibit bacterial population resulting in inhibited nitrifica- tion and blockage of other soil microorganisms of both organic and inorganic constituents in the soil, hence de- creasing the soil fertility. Yield of vegetables notably garden eggs and tomato were suppressed by increased application of lindane. Pesticide application had a higher effect on fungal population. Studies of the solubility of pesticides and its sorption on soil are known to be inversely related, increased solu- bility implies less sorption. One of the most useful indi- ces for quantifying pesticide sorption on soils is the par- tition coefficient (Koc) defined as the ratio of pesticide concentration in the sorbed-state (bound to soil particles) to solution-phase (dissolved in the soil-water). Thus, for a given amount of pesticide applied, the smaller the Koc value, the greater the concentration of pesticide in solu- tion. Pesticides with small Koc values are more likely to be leached compared to those with large Koc values [34]. Studies on depletion of herbicides in two soil ecosystems in Ghana [35] indicated that the kinetics involved in the process of depletion of the herbicides to a higher degree could be described as first order reaction kinetics and the half-life of herbicides ranged between 14.8 and 32.2 days. Apoh et al., [36] in their study of the persistence of lin- dane in Ghanaian coastal savanna topsoil reported that the dissipation pattern favours second order kinetics and persistence depend on the organic matter content of the soil. Sunlight induced reactions may contribute to the chemical transformation of organic pollutants. Recent evidence [29,30] suggests that organic pollutants may react through both direct and indirect photochemical pathways. Many river basins are eutrophic and contain higher amounts of dissolved organic matter (DOM). In connection with these, studies of both DOM and nitrate was shown to the degradation of pesticides by sunlight. Moisture and organic matter content was found to facili- tate depletion of herbicides in soils [31,35,36]. The de- gree to which this could occur may highly depend upon the composition and amount of photosensitizers present. Most of the dissolved organic matter in natural waters is comprised of decomposed organic matter and extracellu- lar products as well as amorphous humic substances which may contain a variety of chromophoric functional groups that absorb sunlight. 7. Pesticides and Human Health Impacts Pesticides have improved longevity and the quality of life, chiefly in the area of public health. The use of pesti- cides also constitutes an important aspect of modern ag- riculture. Unfortunately, most pesticides are poisons and can be particularly dangerous when misused. Fish-kills, reproductive failure in birds, and acute illnesses in peo- ple have all been attributed to exposure to or ingestion of pesticides, usually as a result of misapplication or care- less disposal of unused pesticides and containers. Pesti- cide losses from areas of application and contamination of non-target sites such as surface and ground water rep- resent a monetary loss to the farmer as well as a threat to the environment [1]. Meeting the minimum requirements of occupational health standards is regarded as one of the elements of sustainable agricultural development. In Ghana, there are no countrywide statistics on the extent of poisoning of farmers through pesticide. Three reasons have been iden- tified for this: 1) farmers seek medical attention only in cases of serious health problems due to the costs in- volved 2) most of the farmers are not aware of the spe- cific symptoms of pesticide poisoning and 3) health workers are not informed and therefore cannot draw the right conclusions, and the system of health statistics does not clearly specify cases of poisoning. While epidemiological studies have often implicated agrochemicals especially pesticides as causative agents in human cancer, it has usually been at a marginal level of significance. It is suspected that DDT and its metabo- lite DDE, still persisted in the environment long after being banned and may be involved in the causation of breast cancer as a result of estrogenic activity [16]. Human exposure to pesticides in Ghana may be exces- sive, especially through ground application in cocoa, pineapple, cotton and vegetable farms where compounds of high toxicity are often used [33,38]. Large number of workers, labourers, and spraying observers are involved in spraying of these farms but unfortunately, they are often not equipped with protective clothes or masks. Therefore, this may reflect the great magnitude of human exposure to pesticide intoxication in Ghana. Official re- ports on agro-chemical poisoning are lacking, except a few published reports [2,5,8]. A survey on the extent of pesticide associated symptoms in farmers involved in irrigation projects in Ghana revealed that about 36% of the farmers had experienced negative side effects after applying pesticides [16]. The most significant symptoms include headache, dizziness, fever, blurred vision, and nausea/vomiting. A study on farmer’s perception and use of pesticides in Ghana [8] also revealed that although some farmers may be aware of pesticide hazards, ade- quate protection is hardly taken to minimize risk while knowledge of pesticide selection, application rates and timing are also poor. A study on possible poisoning caused by pesticides was carried out by researchers of the Ghana Standards Board Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review 228 and the Department of Pathology of the University of Ghana between 1989 and 1997 [37]. The research ana- lyzed organs of the body, body fluids, foods and drinks submitted by various hospitals and other state institutions in Ghana. Out of the 1215 toxicological cases examined, 963 tested positive for chemical poisoning. The 30% cases of chemical poisoning were directly related to the misuse of pesticides. The main causes for deaths were carbamates (126 cases), organophosphorous (66 cases) and organochlorines (74 cases). Unfortunately in March 1999, three children died after consuming fruits contain- ing high residue of carbamates [5] in Ghana. An epidemiological survey and haematological studies on the probable effect of pesticide on the health status of farmers in Akomadan and Afrancho traditional area of the Ashanti Region of Ghana conducted by Mensah et al. [38], revealed that most of the farmers have experienced sneezing (56%), skin irritation (65.9%), headaches (48.2%), dizziness (40.0%), abdominal pains (20.0%) and cough (57.6%). About 30% of the farmers were found to have low red blood cells (RBC) and 38% low white blood cells (WBC). Yeboah et al., [39] reported cases of fatal occu- pational poisoning recorded by the Plant Protection and Regulatory Services of the ministry of Agriculture in Ghana (PPRS) between 1986 and 1989. Further investigation into probable effects of aerosol pesticides on hepatic functions among farmers in Ako- madan and Afrancho districts in the Ashanti region [12] indicated that aerosol pesticides used by farmers did not pose any immediate threat to hepatic function of farmers at least in short term, however, long term effect of per- sistent pesticide usage could not be overlooked. Mercury from mercuric pesticide has been known to cause poi- sonings in areas where seed grains were treated with mercuric pesticides to curb fungal growth. These occur- rences have exhibited toxic effects in humans and wild- life [40] in Ghana. Feeding birds are also susceptible to adverse effects of mercuric pesticide coated grains and several species have experienced reduced reproduction and increased mortality. Thus, the unfortunate conse- quences of pesticide use has led to wildlife distress, in- terference with reproduction, birth defects, and depressed immunity which detrimentally affects wildlife popula- tions and on a larger scale the surrounding ecosystem. 8. Pesticides in Air and Human Exposure In Ghana, the chances of misuse of agrochemicals are relatively high due to low awareness of the safe use of agrochemicals especially pesticides and illiteracy. There are various means by which human become exposed to agrochemicals and other toxic chemicals, notable among which are exposure via diet, drinking water, soil and air. Persistent pesticides move through air, soil, and water finding their way into living tissues where they can bio- accumulate up the food chain. The public health risks of pesticides depend not only on how toxic various com- pounds are, but also on how many people are exposed, their risk-related demographic, socioeconomic and health profile, the kinds of contaminants they are exposed to, and the extent and routes of exposure. The general popu- lation can be exposed to low levels of pesticides in three general ways: vector control for public health and other non-agricultural purposes; environmental residues; and food residues. Health and safety issues are exacerbated by a general lack of hazard awareness; the lack of protective clothing, or difficulty of wearing protective clothing in tropical climates; shortage of facilities for washing after use, or in case of accidents; the value of containers for re-use in storing food and drink; illiteracy; labeling difficulties relating either to language, complexity or misleading information; lack of regulatory authorities; and lack of enforcement. Poisoning surveillance systems are usually maintained only at large urban hospitals. Village health centers may be completely excluded from monitoring reports [16]. A study by Yeboah et al., [12] and Mensah et al., [38], revealed that about 82% of farmers in Ghana are illiter- ates and do not always use any form of standard protec- tive clothing. Most of the farmers were not aware of long term chemical and physiological effect associated with improper agrochemical handling. About 41.5% of farm- ers claim they change their cloths before and after pesti- cide use, however, less than 5% washed these clothing before using them again. These contaminated clothing can enhance dermal exposure which can result in sys- temic poisoning. It was also revealed that some of the farmers were involved in unhealthy practices that put them at high risk of being affected by the pesticides. They drink from water bodies near their farms and eat without washing their hand with any detergent. Malnutrition could bring about an increased suscepti- bility to pesticide intoxication, especially in women and children. Malnourishment, infectious diseases, and toxic chemicals interact with each other and with the immune system. Consequently, pesticides immunosuppressive effects which have more pronounced health consequences in developing countries, could significantly affect im- mune responses at very low doses. Humans ingesting food preparations contaminated with pesticide, workers in pesticide manufacturing and packing units, and agricul- tural workers who prepare, mix, and apply pesticides in the fields are all potentially exposed to more than one pesticide on the same or on successive days. Such expo- sure may induce a wide array of health effect, ranging from myelotoxicity to cytogenetic changes and carcino- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review229 genic effects. Human exposure is on more sporadic basis through a hodgepodge of human activities, farmers and farm workers; workers and laborers in pesticide factories; populations that live in areas of intensive pesticide use or production; and populations exposed to persistent pesti- cides that bioaccumulate in food are potentially exposed to pesticide hazards [12]. Those that can be exposed to high levels of bio-accumulated pesticides include: con- sumers of fish, livestock, and dairy products; foetus and nursing infants whose mother’s bodies have accumulated substantial levels of persistent agrochemicals; and sick people who metabolize pesticide-bioaccumulated fatty tissues while ill [38]. Soil can be a key source of expo- sure in young children who show significant hand-to- mouth activity. Although modern pesticides are readily degraded in the environment by soil micro-organisms, residues on treated crops such as fruit or vegetables often do not dissipate quickly. Most pesticides lack systemic action and therefore residues are mainly on the exterior surfaces where they are amenable to removal in opera- tions such as trimming, washing or peeling that most crops undergo before consumption. 9. Conclusions Agrochemicals are generally recognized as a significant factor in enhancing the ability to meet Ghana’s need for sufficient, safe and affordable food and fiber, however, increased usage have led to environmental deterioration. The review of agrochemical monitoring and exposure clearly indicate that not much have been done in the area of agrochemical studies in Ghana. There was lack or absence of corrective and preventive measures, presence of persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic agrochemicals in water, fish, vegetables and human fluids and there is strong evidence that accidents of pesticide exposure in Ghana may occur due to lack of awareness about safe use of agrochemicals. Keeping in view of the present scenario, it is strongly recommended that extensive awareness creation for safe use of agrochemicals be in- troduced, epidemiological studies and impact of agro- chemical usage in the country be instituted. This will provide information on biological indices of agrochemi- cals for effective monitoring of exposure of farmers and farm workers to agrochemicals. REFERENCES [1] P. F. Carvalho, “Agriculture, Pesticides, Food Security and Food Safety,” Environmental Science and Policy, Vol. 9, No. 7-8, 2006, pp. 685-692. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2006.08.002 [2] M. I. Tariq, S. Afzal, I. Hussain and N. Sultana, “Pesti- cide Exposure in Pakistan: A Review,” Environment In- ternational, Vol. 33, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1107-1122. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2007.07.012 [3] FAO, “Fertilizer Use by Crop in Ghana,” FAO Corporate Document Repository, Rome, 2005. [4] Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA), “Agriculture in Ghana: Facts and Figures,” Produced by the Statistics, Research and Information Directorate, Accra, 2003. [5] FAO, “Scaling soil nutrient balances,” FAO Fertilizer & Plant Nutrition Bulletin, No. 15, Rome, 2004. [6] W. J. Ntow, “Organochlorine Pesticides in Water, Sedi- ment, Crops and Human Fluids in a Farming Community in Ghana,” Environmental Contamination and Toxicol- ogy , Vol. 40, No. 4, 2001, pp. 557-563. doi:10.1007/s002440010210 [7] Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA), “National Soil Fertility Management Action Plan,” Directorate of Crop Services, Accra, Ghana, 1998. [8] J. W. Ntow, H. J. Gijzen, P. Kelderman and P. Drechsel, “Farmer Perception and Pesticide Use Practices in Vege- table Production in Ghana,” Pest Management Science, Vol. 62, No. 4, 2006, pp. 356-365. doi:10.1002/ps.1178 [9] M. Kyofa-Boamah and E. Blay, “A Study on Pineapple Production and Protection Procedure in Ghana,” Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Plant Protection and Regulatory Services Directorate, Accra, Ghana, 2000. [10] A. R. Cudjoe, M. Kyofa-Boamah and M. Braun, “Se- lected Fruit Crops (Mango, Papaya and Pineapple),” Handbook of Crop Protection Recommended in Ghana, an IPM Approach, Ministry of Food and Agricul- ture/Plant Protection and Regulatory Services Director- ate/GTZ, Accra-Ghana, Vol. 4, 2002, pp. 60-63. [11] E. Aboagye, “Patterns of Pesticide Use and Residue Lev- els in Exportable Pineapple (Ananas Cosmosus L. Merr),” M.Phil Thesis, University of Ghana, Legon, 2002. [12] F. A. Yeboah, F. O. Mensah and A. K. Afreh, “The Prob- able Toxic Effects of Aerosol Pesticides on Hepatic Function among Farmers at Akomadan/Afrancho Tradi- tional Area of Ghana,” Journal of Ghana Science Asso- ciation, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2004, pp. 39-43. [13] B. Dinham, “Growing Vegetables in Developing Coun- tries for Local Urban Populations and Export Markets: Problems Confronting Small-Scale Producers,” Pest Management Science, Vol. 59, No. 5, 1993, pp. 575-582. doi:10.1002/ps.654 [14] B. Awumbila and E. Bokuma, “Survey of Pesticides Used in the Control of Ectoparasites of Farm Animals in Ghana,” Tropical Animal Health and Production, Vol. 26, No. 1, 1994, pp. 7-12. doi:10.1007/BF02241125 [15] B. Awumbila, “Acaricides in Tick Control in Ghana and Methods of Application,” Tropical Animal Health and Production, Vol. 28, No. 2, 1996, pp. 10-16. doi:10.1007/BF02310699 [16] E. E. K. Clarke, L. S. Levy, A. Spurgeon and I. A. Cal- vert, “The Problems Associated with Pesticide Use by Ir- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP  Agrochemicals and the Ghanaian Environment, a Review Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JEP 230 rigation Workers in Ghana,” Occupational Medicine, Vol. 47, No. 5, 1997, pp. 301-308. doi:10.1093/occmed/47.5.301 [17] J. W. Ntow, “Pesticide Residues in Volta Lake, Ghana,” Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2005, pp. 243-248. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1770.2005.00278.x [18] O. Boateng, “External Trade Statistics January-December 1992,” Ghana Statistical Services, Accra, 1993, pp. 79-80. [19] S. O. Acquaah and E. Frempong, “Organochlorine Insec- ticides in African Agrosystem,” IAEA, IAEA TEC- DOG-93, Vienna, 1995, pp. 111-118. [20] Ghana, EPA, “Registered Pesticides Handbook,” Ghana Environmental Protection Agency, Accra, 2008. [21] J. A. Camargo and A. Alonso, “Ecological and Toxico- logical Effects of Inorganic Nitrogen Pollution in Aquatic Ecosystems: A Global Assessment,” Environment Inter- national, Vol. 32, No. 6, 2006, pp. 831-849. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2006.05.002 [22] R. Carson, “Silent Spring,” Fawcett Crest, Greenwich, 1962. [23] S. O. Acquaah, “Lindane and Endosulfan Residues in Water and Fish in the Ashanti Region of Ghana,” Pro- ceedigs of Symposium on Environmental Behaviour of Crop Protection Chemicals by the IAEA/FAO, IAEA, Vienna, 1-5 July, 1997. [24] G. Darko and S. O. Acquaah, “Levels of Organochlorine Pesticide Residues in Diary Products in Kumasi, Ghana,” Chemosphere, Vol. 71, No. 2, 2008, pp. 294-298. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.09.005 [25] A. K. Armah, G. A. Dapaah and G. Wiafi, “Water Qual- ity Studies on Two Irrigation Associated Rivers in Southern Ghana,” Journal of Ghana Science Association, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1999, pp. 100-109. [26] W. J. Ntow, “Pesticide Misuse at Akumadan to be Tack- led,” NARP Newsletter, Vol. 3, No. 3, 1998. [27] F. Botchway, “Analysis of Pesticide Residues in Ghana’s Exportable Cocoa,” Higher Certificate Project, Institute of Science and Technology, London, 2000. [28] D. K. Essumang, G. K. Togoh and L. Chokky, “Pesticide Residues in the Water and Fish (Lagoon Tilapia) Samples from Lagoons in Ghana,” Bulletin of the Chemical Soci- ety of Ethiopia, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2009, pp. 19-27. [29] L. R. Goldman and S. Koduru, “Chemicals in the Envi- ronment and Developmental Toxicity to Children: A Public Health Policy Perspective,” Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 109, No. 9, 2001, pp. 412-413. [30] D. C. Gooddy, P. J. Chilton and I. Harrison, “A Field Study to Assess the Degradation and Transport of Diuron and Its Metabolites in a Calcareous Soil,” Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 297, No. 1-3, 2002, pp. 67-83. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00079-7 [31] M. Glover-Amengor and F. M. Tetteh, “Effects of Pesti- cide Application Rate on Yield of Vegetables and Soil Microbial Communities,” West Africa Journal of Applied Ecology, Vol. 12, 2008, pp. 1-7. [32] B. N. Nuertey, F. M. Tetteh, A. Opoku, P. A. Afari and T. E. O. Asamoah, “Effect of Roundup-Salt Mixtures on Weed Control and Soil Microbial Biomass under Oil Palm Plantation,” Journal of Ghana Science Association, Vol. 9, 2007, pp. 61-75. [33] P. O. Yeboah, S. Lowor and C. K. Akpabli, “Comparism of Thin Layer Chromatography and Gas Chromatography Determination of Propoxur Residues in a Cocoa Ecosys- tem,” African Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2003, pp. 24-28. [34] W. J. Mavura and P. T. Wangila, “Distribution of Pesti- cide Residues in Various Lake Matrices: Water, Sediment, Fish and Algae, the Case of Lake Nakuru, Kenya,” ANCP Inaugural Conference Proceedings, Tanzania, 2004. [35] S. Afful, S. A. Dogbe, K. Ahmad and A. T. Ewusie, “Thin Layer Chromatographic Analyses of Pesticides in a Soil Ecosystem,” West Africa Journal of Applied Ecology, Vol. 14, 2008, pp. 1-7. [36] F. E. Apoh, P. O. Yeboah and D. K. Dodoo, “Persistence of Lindane in Ghanaian Coastal Savanna Topsoil,” Pro- ceedings of the 6th International Chemistry Conference in Africa, University of Ghana, Legon, 1995. [37] E. Adetola, J. K. Ataki, E. Atidepe, D. K. Osei and A. B. Akosa, “Pesticide Poisoning—A Nine Year Study (1989- 1997),” Department of Pathology, University of Ghana Medical School and Ghana Standards Board, Accra, 1999. [38] F. O. Mensah, F. A. Yeboah and M. Akman, “Survey of the Effect of Aerosol Pesticide Usage on the Health of Farmers in the Akomadan and Afrancho Farming Com- munity,” Journal of Ghana Science Association, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2004, pp. 44-48. [39] P. O. Yeboah, G. M. S. Klufio, G. A. Dixon and A. Youdeowe, “TCDC Oriented Subregional Workshop on Pesticides Management Report,” FAO, 1989. [40] L. K. A. Derban, “Outbreak of Food Poisoning Due to Alkyl Mercury Fungicide on Southern Ghana State Farms,” Archives of Environment Health, Vol. 28, No. 1, 1974, pp. 49-52.

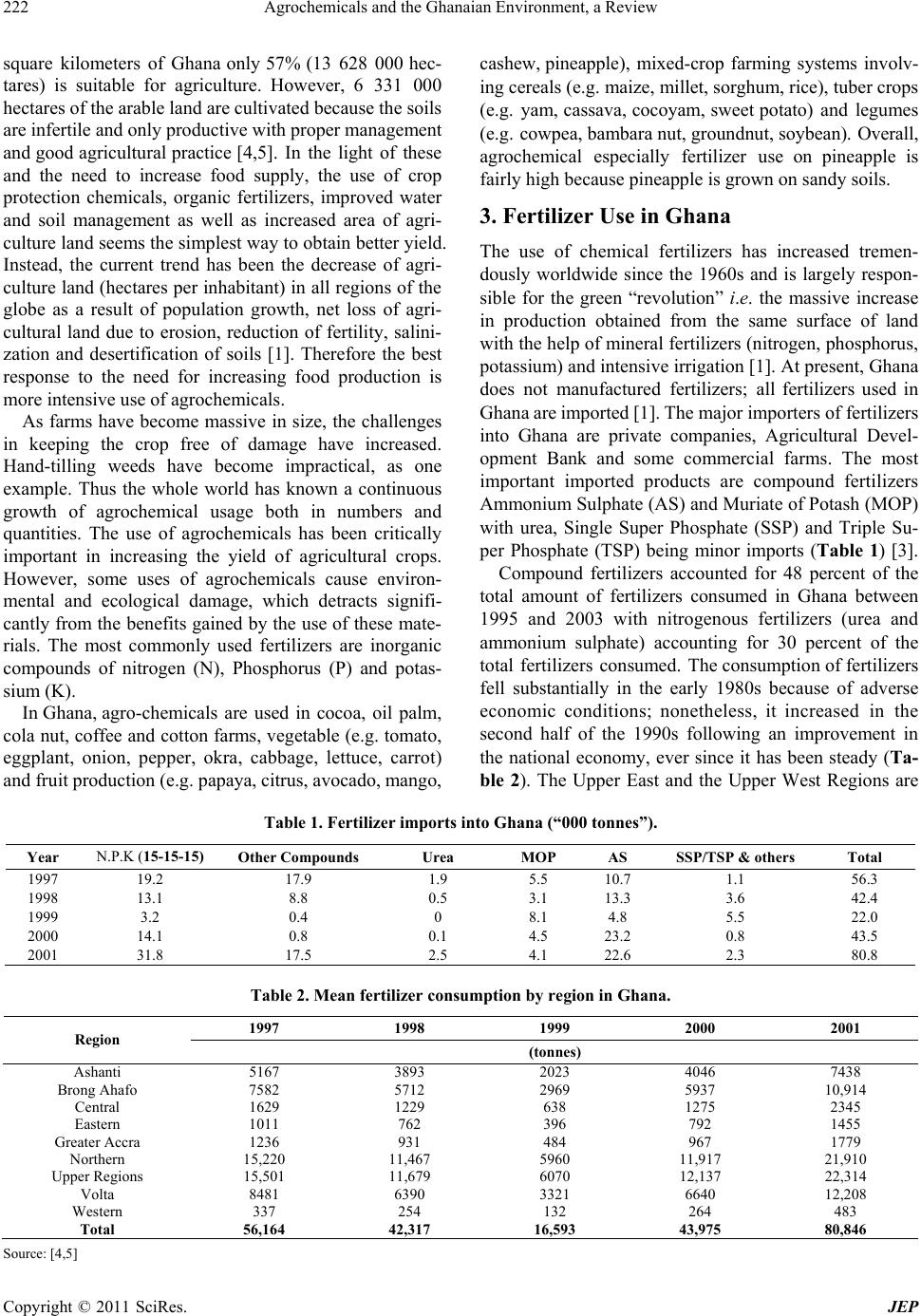

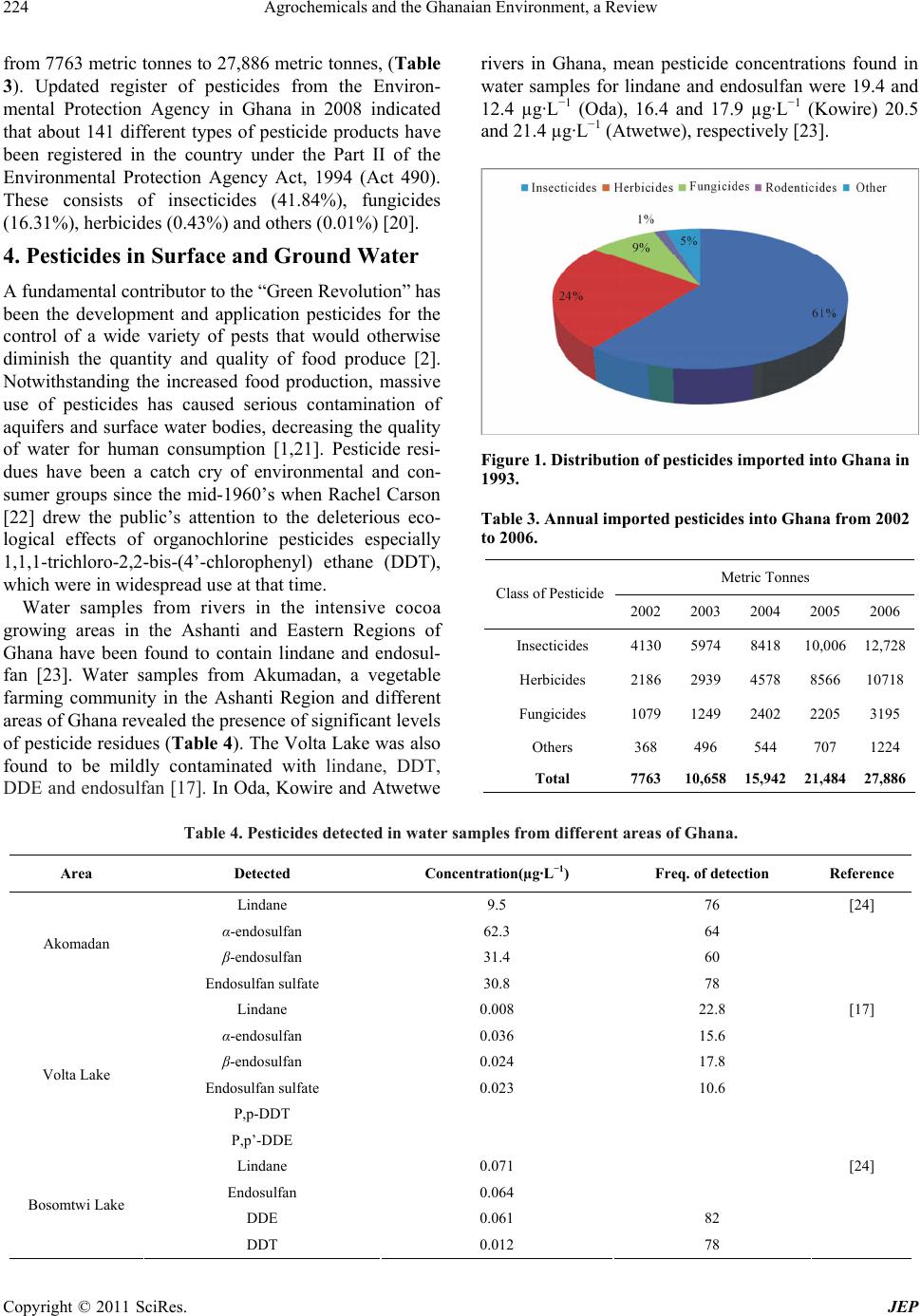

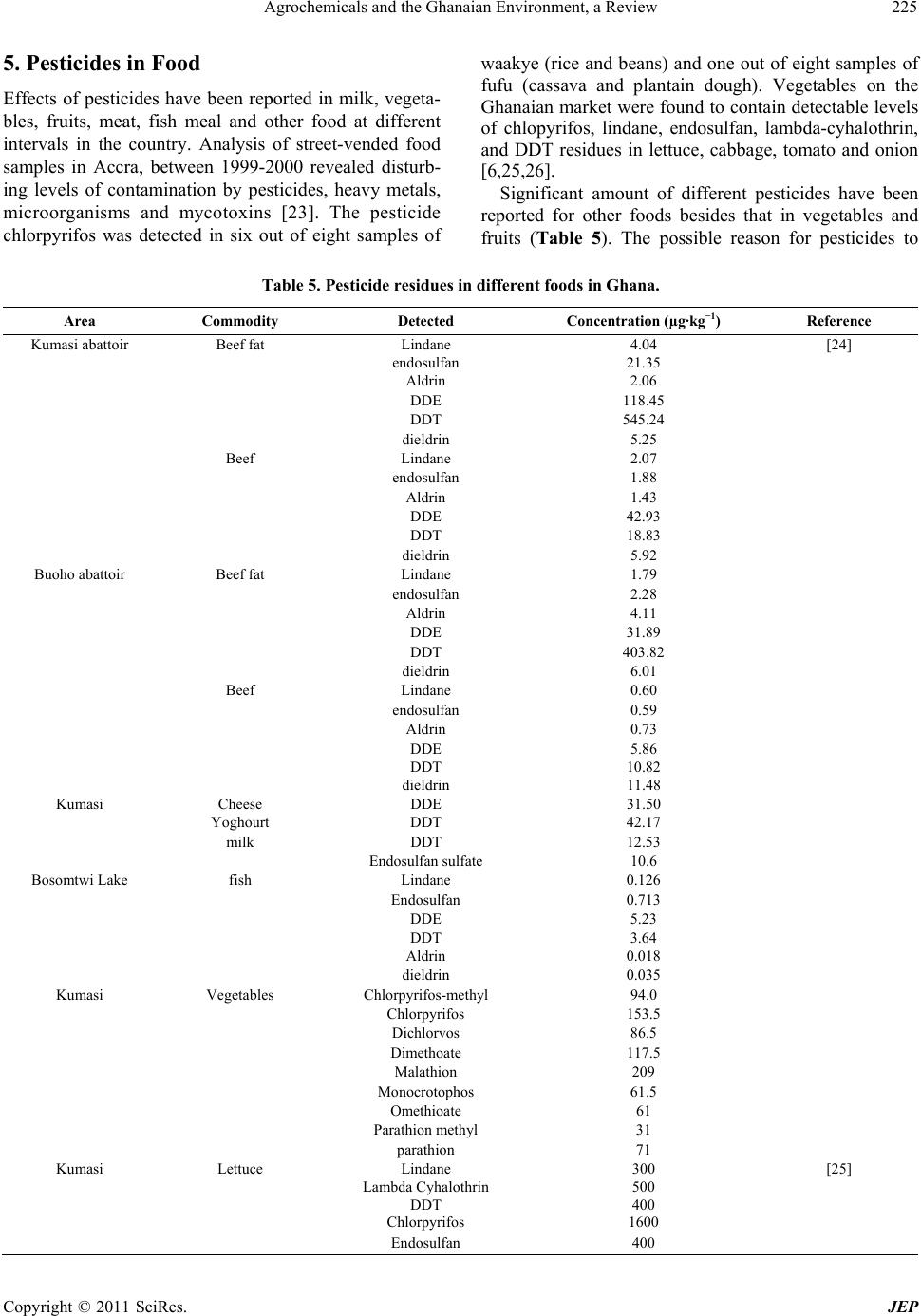

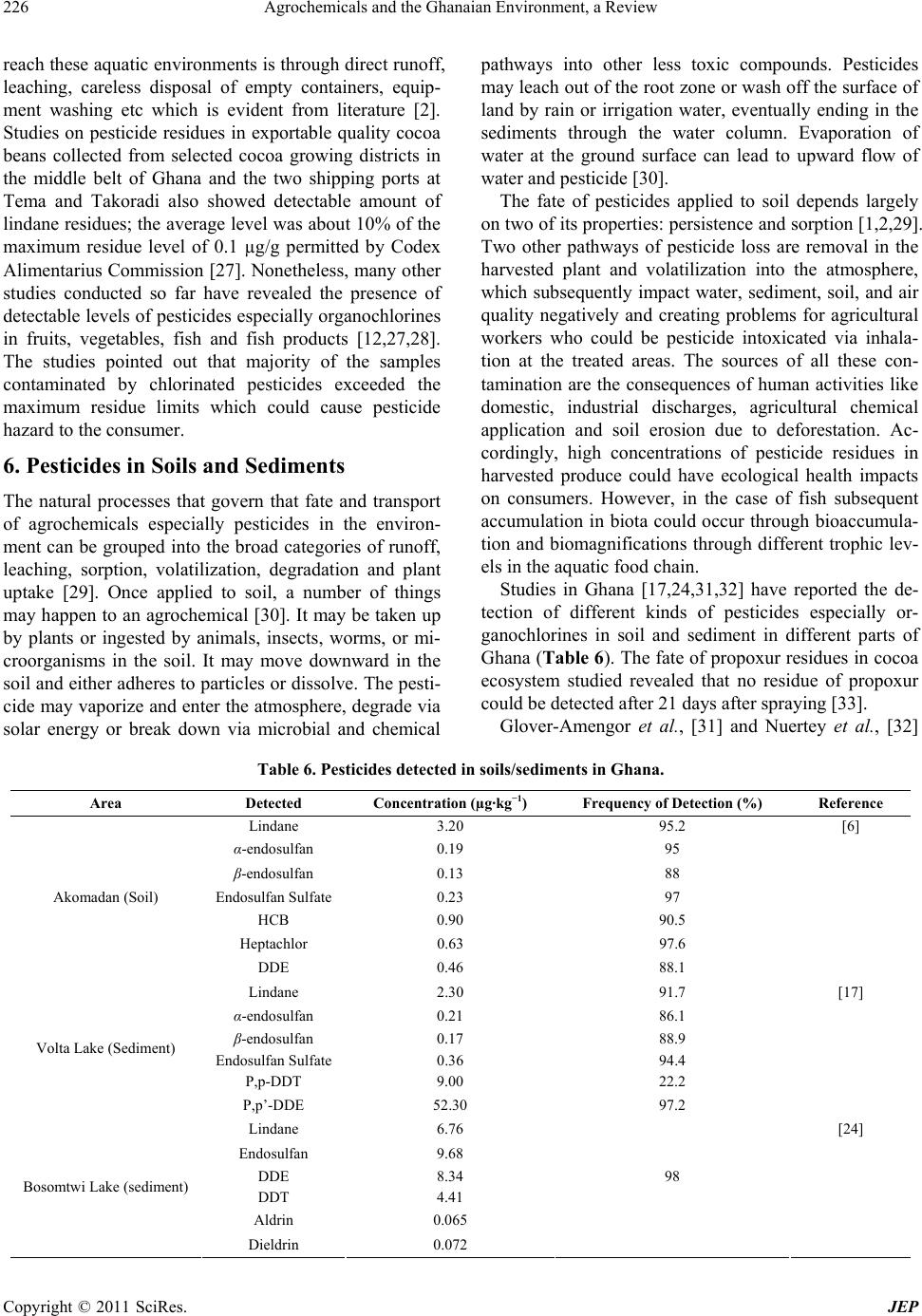

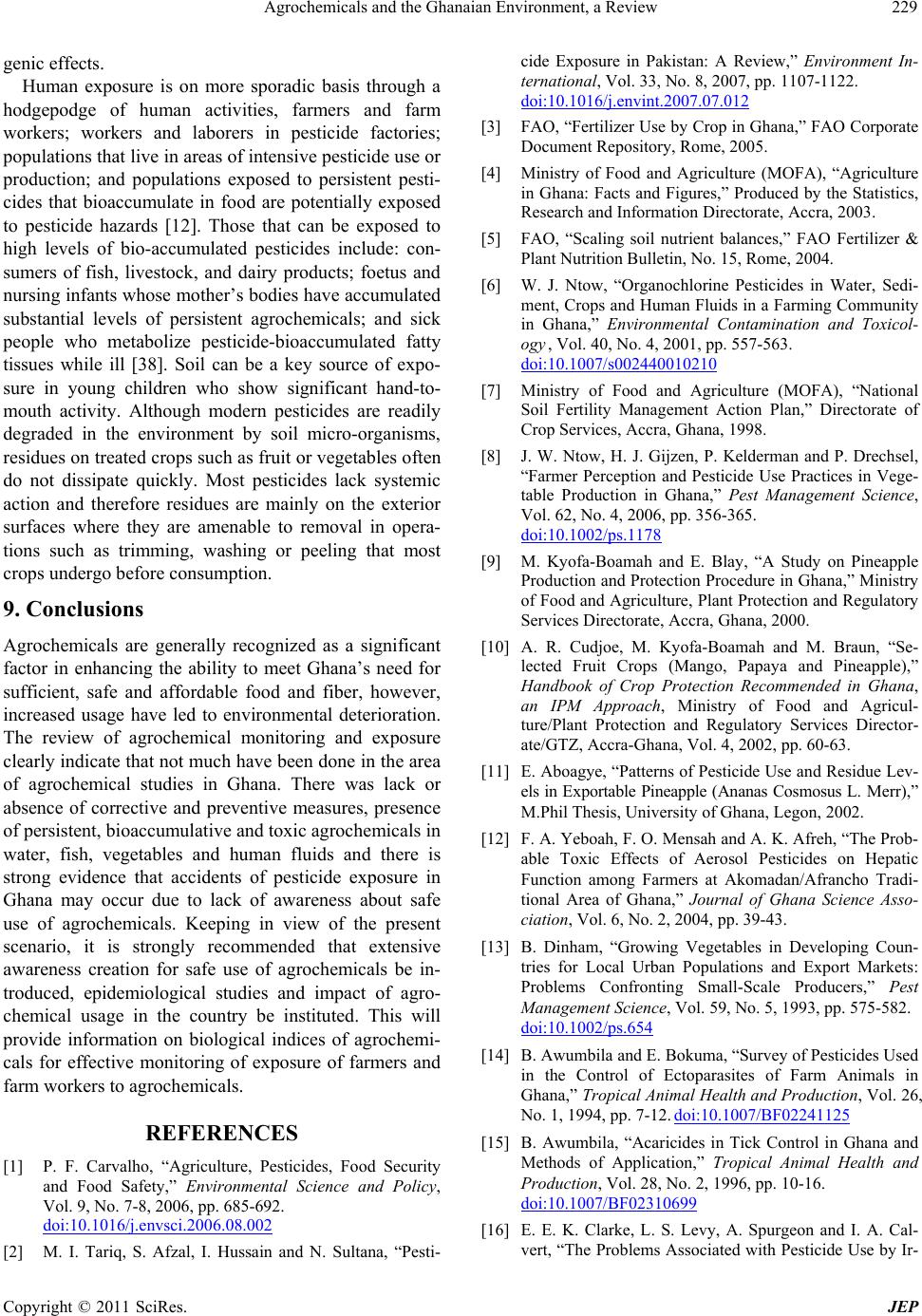

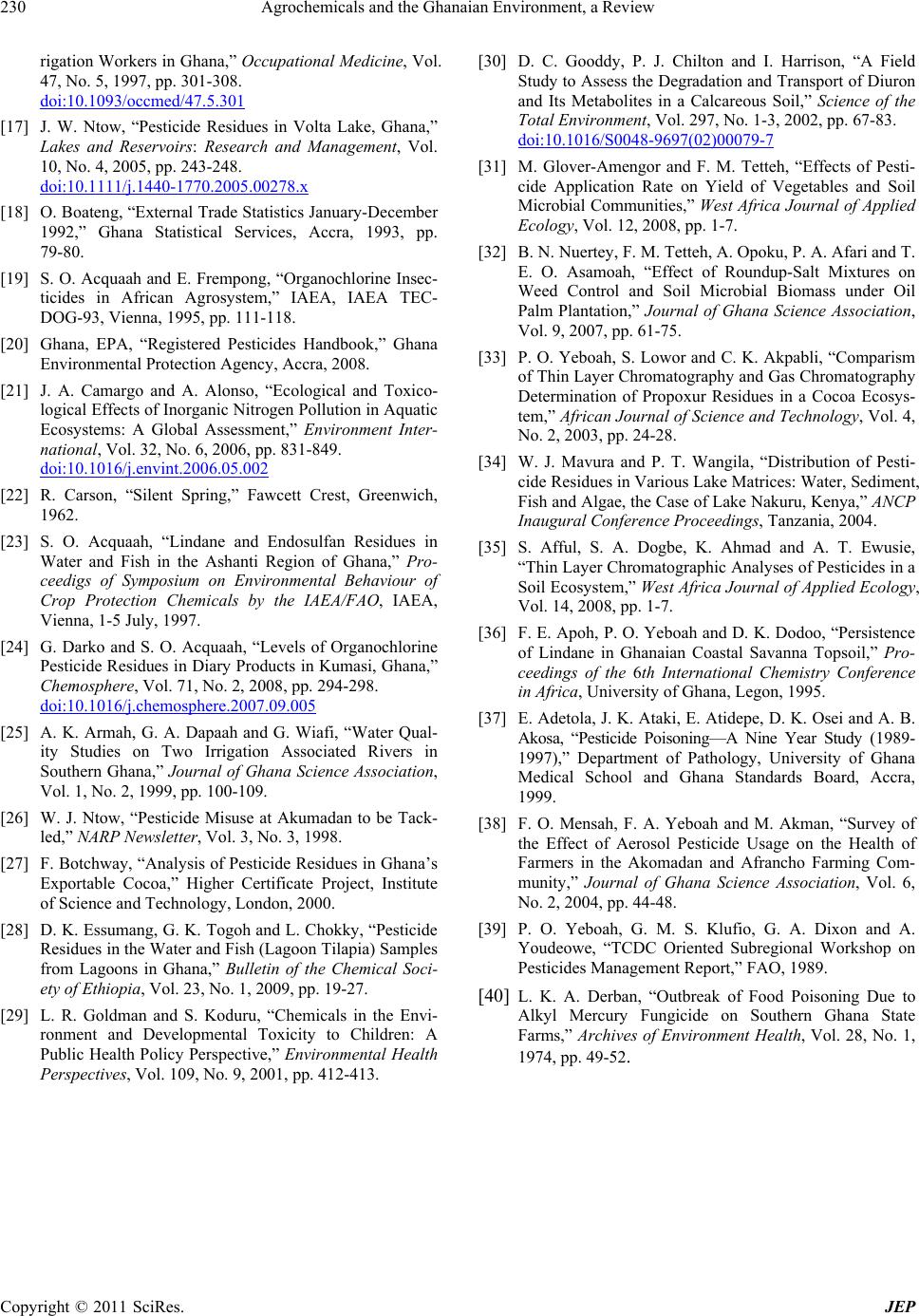

|