Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

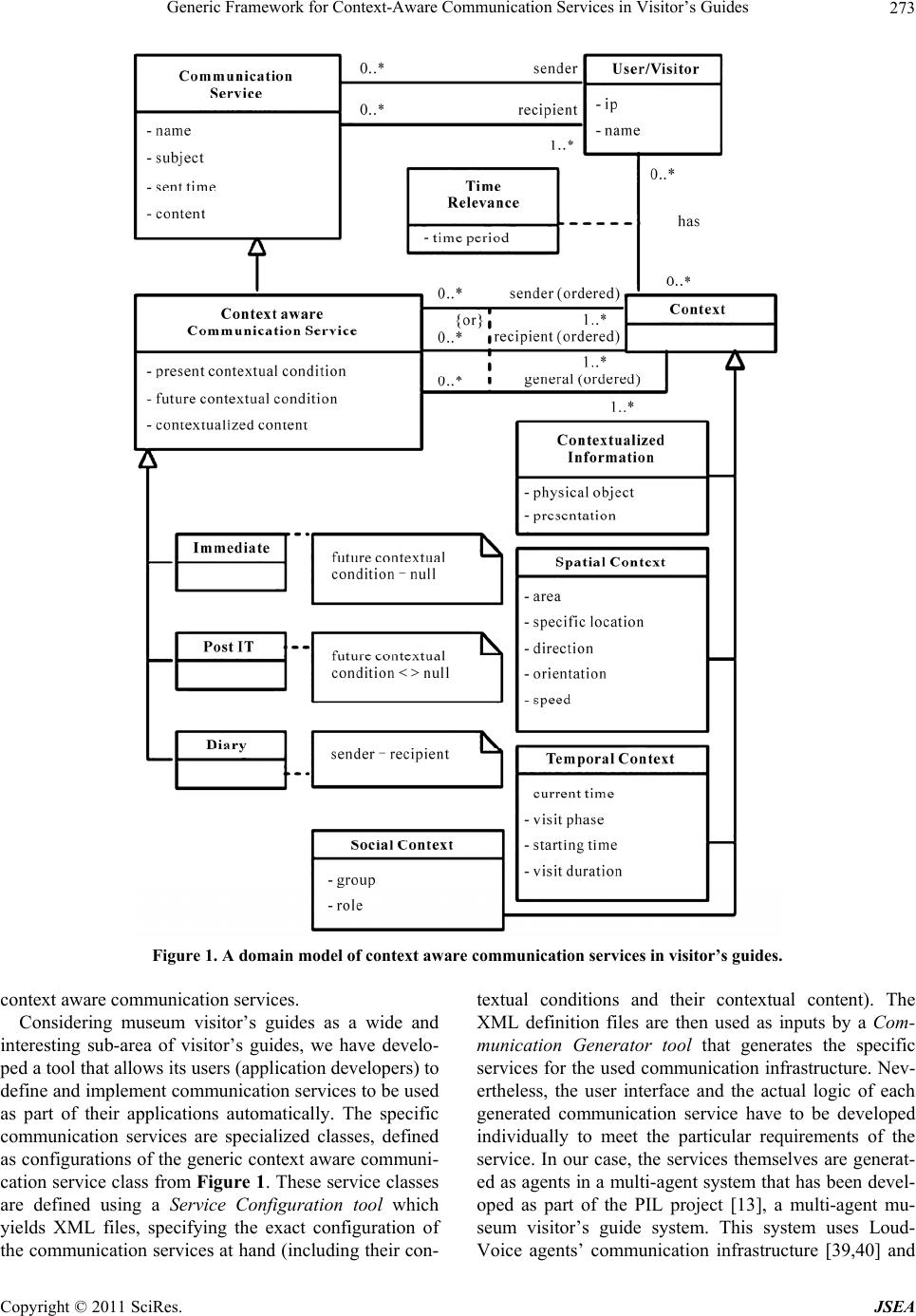

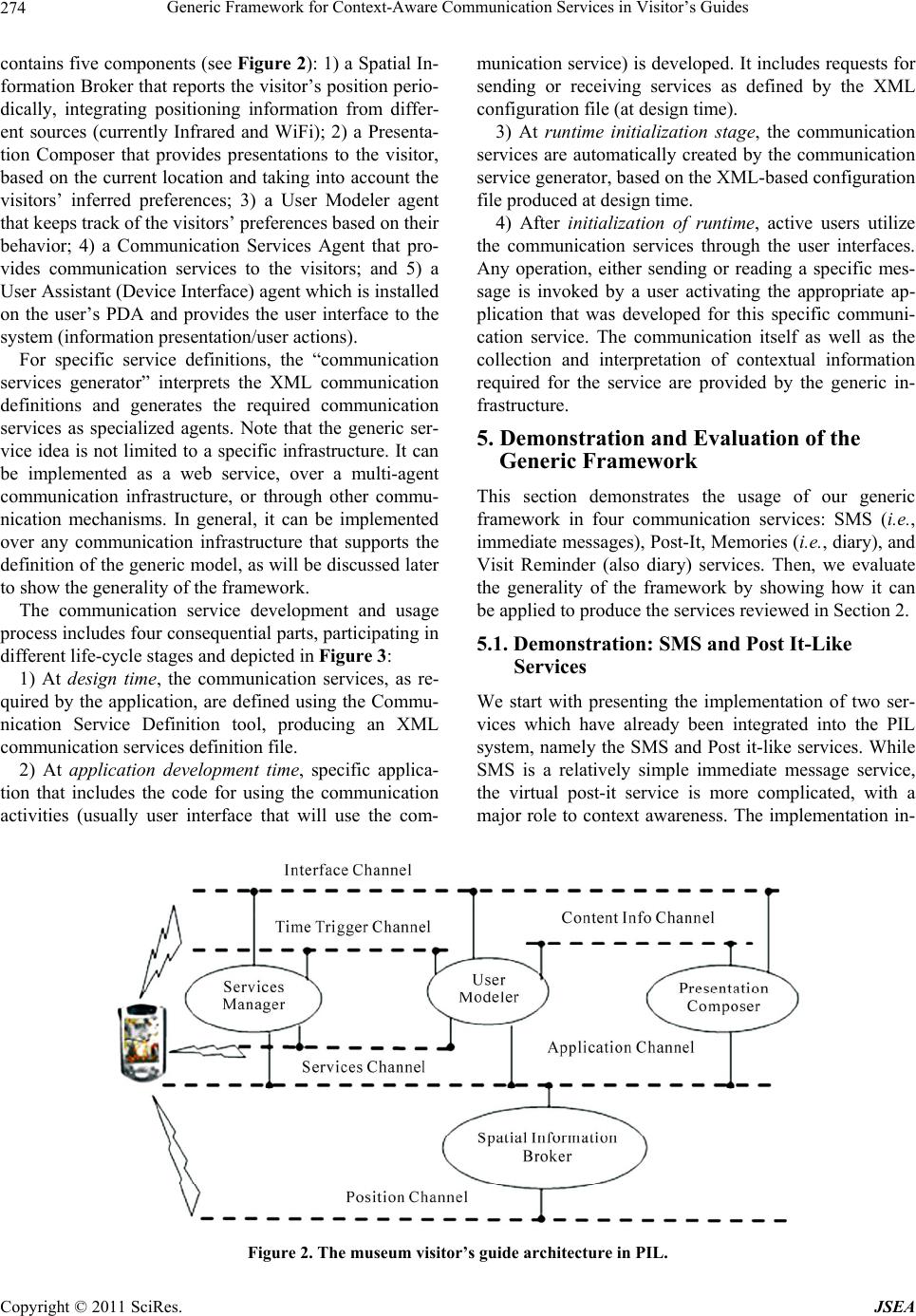

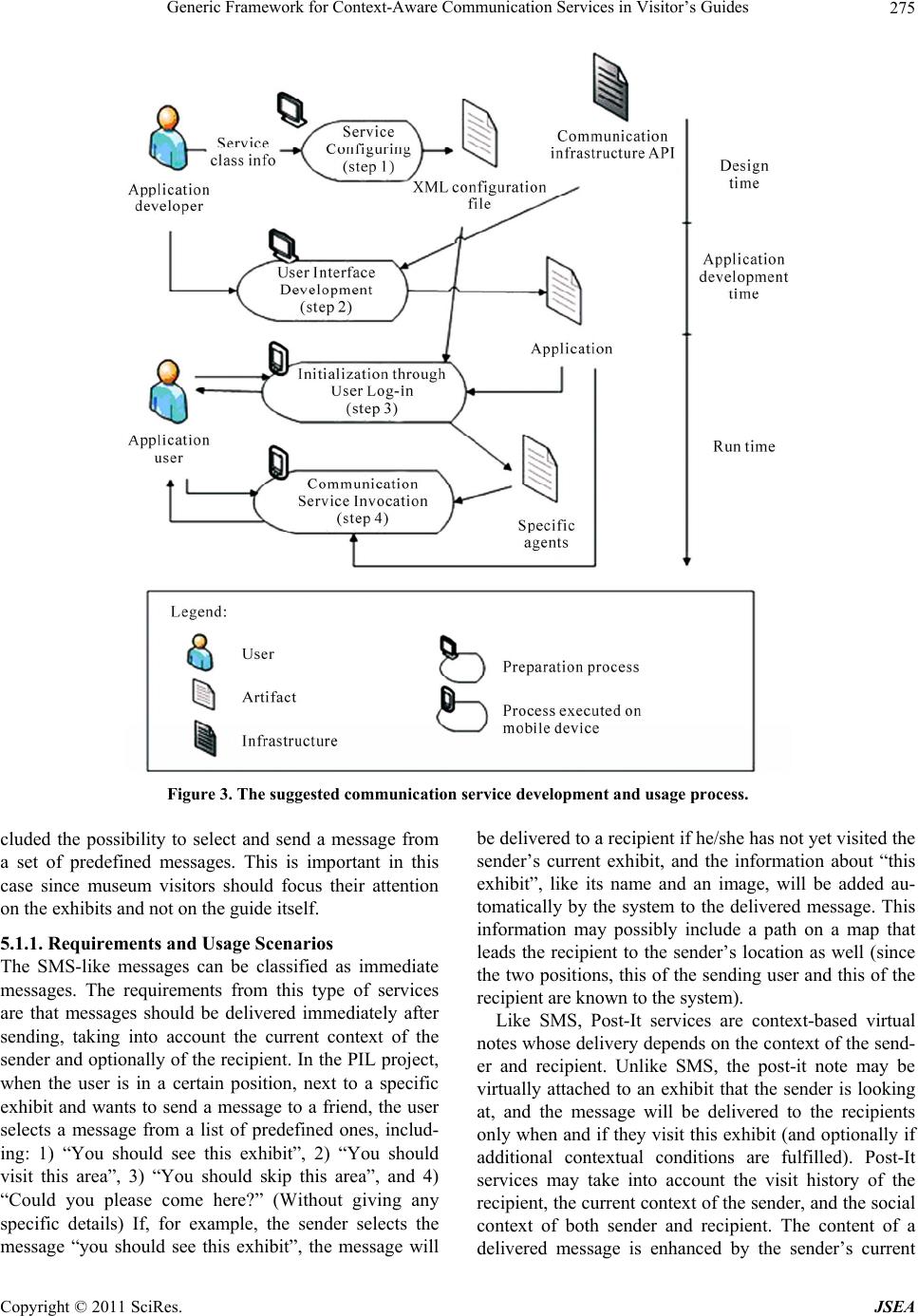

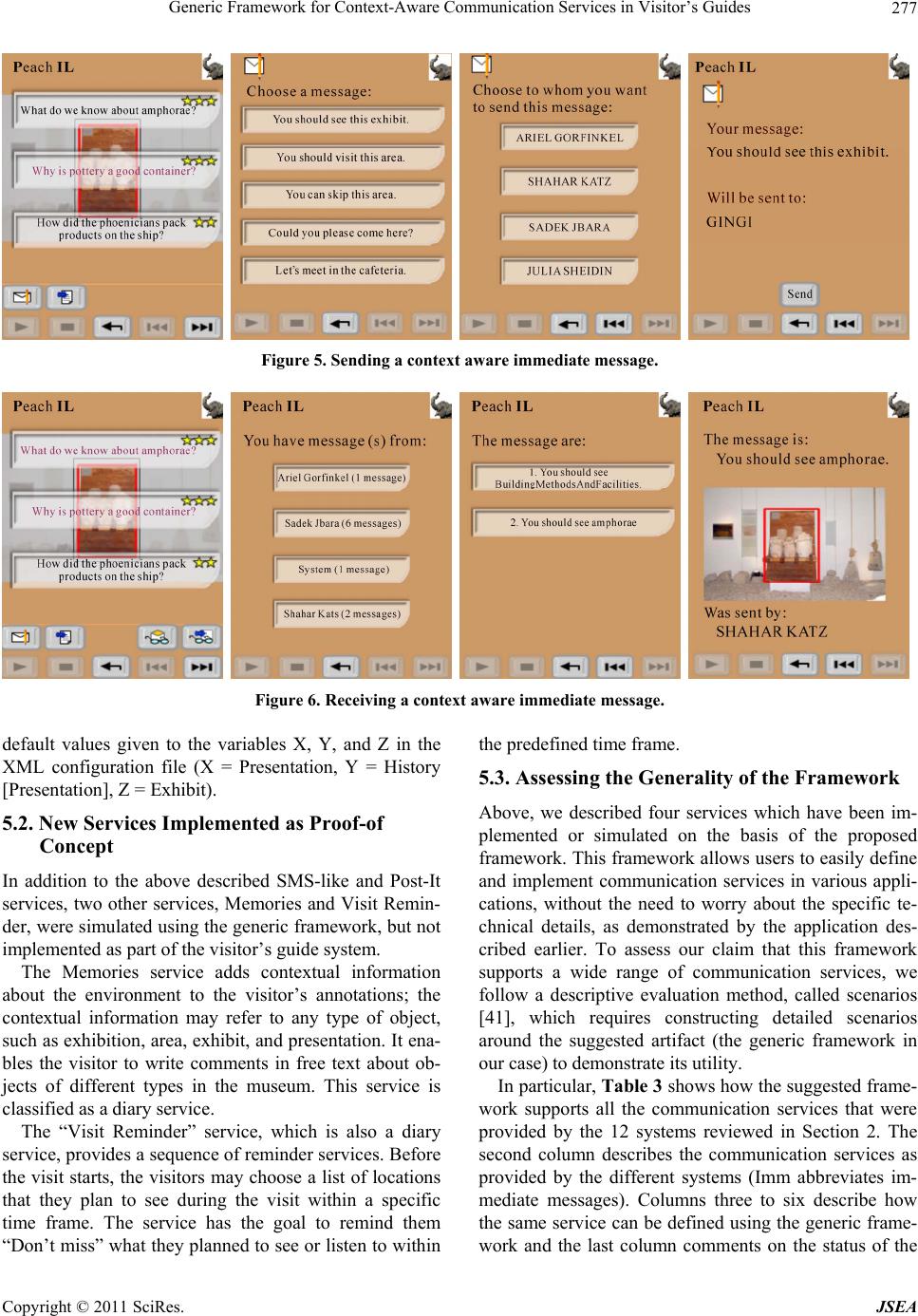

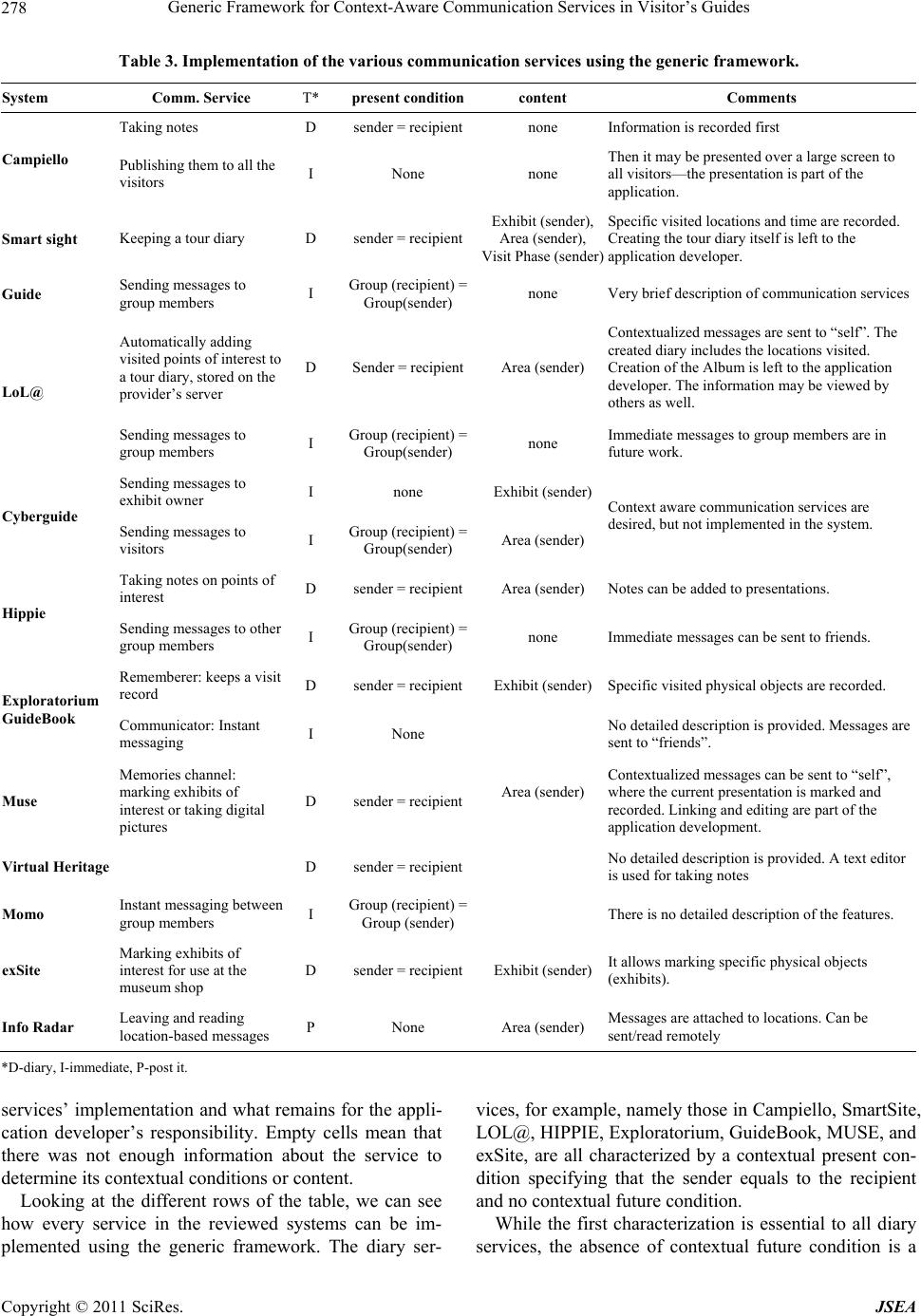

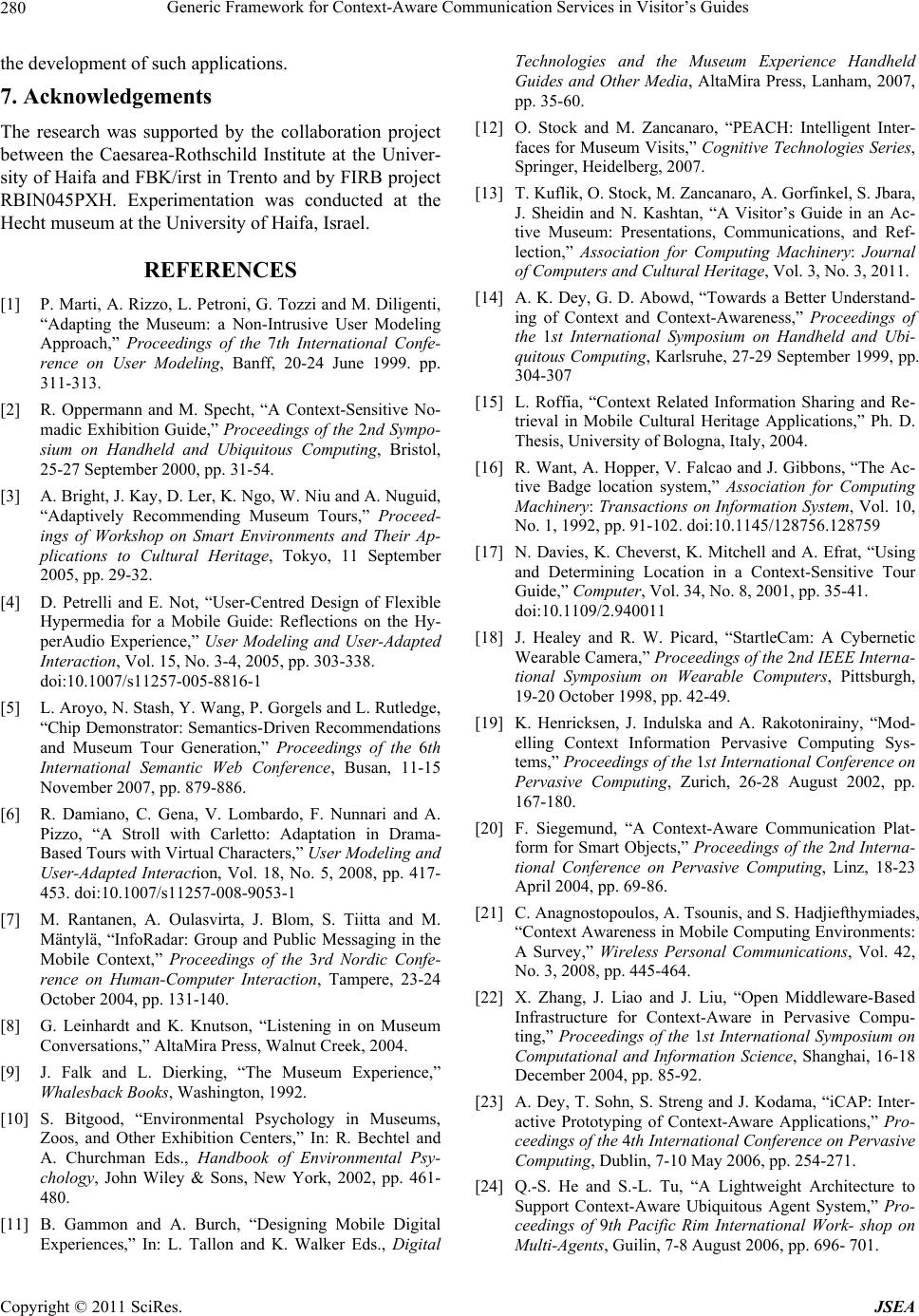

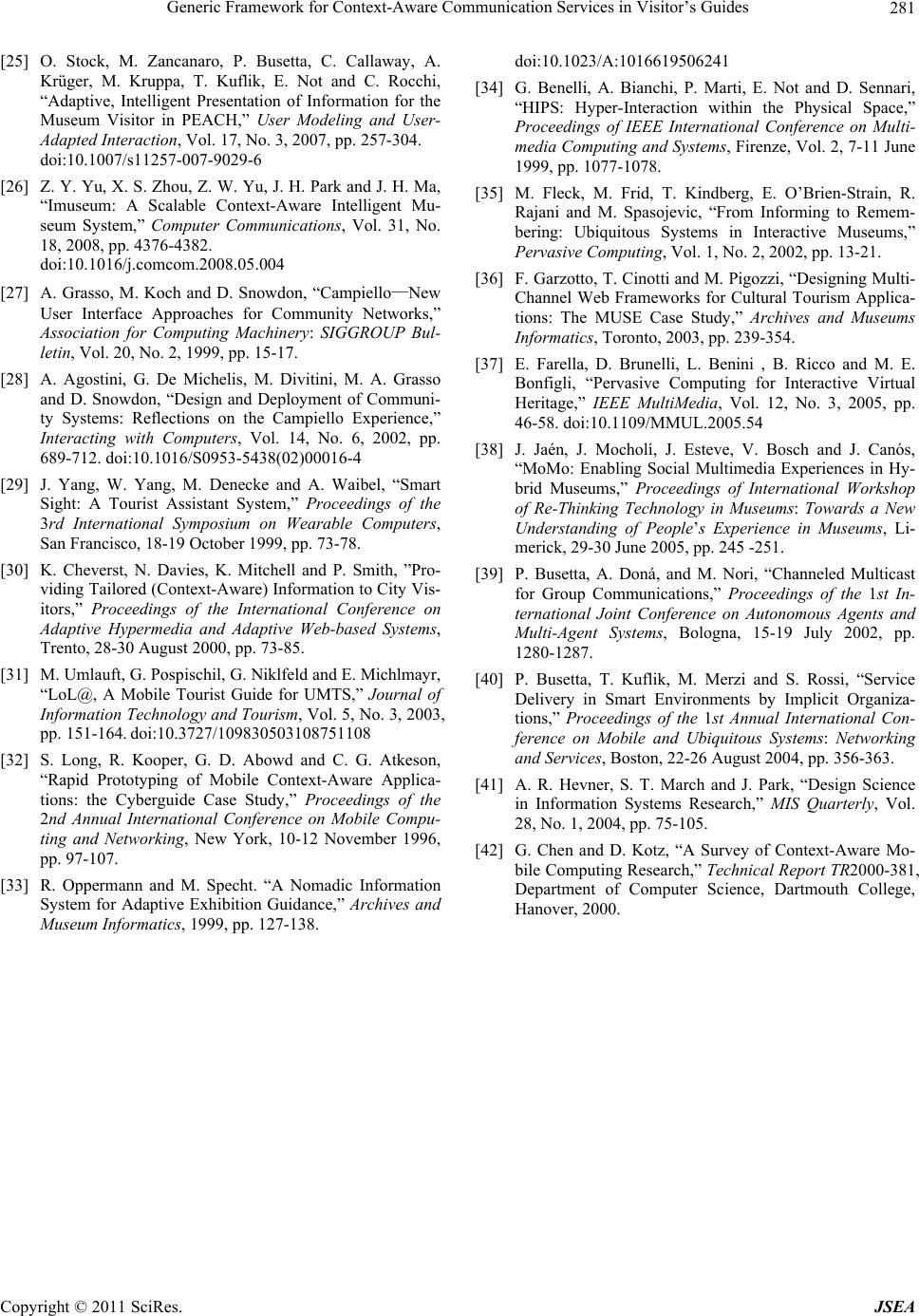

Journal of Software Engineering and Applications, 2011, 4, 268-281 doi:10.4236/jsea.2011.44030 Published Online April 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jsea) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Tsvi Kuflik1, Pnina Soffer1, Iris Reinhartz-Berger1, Sadek Jbara1, Oliviero Stock2 1Department of Information Systems, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel; 2FBK-irst, Trento, Italy. Email: {tsvikak, sp nin a, iri s}@ is.haifa.ac.il, sjbara@gmail . com, stock@fbk.eu Received April 2nd, 2011; revised April 12th, 2011; accepted April 21st, 2011. ABSTRACT Ubiquitous computing plays an increasing role in our lives. Typically, applications in ubiquitous computing environ- ments are context aware, namely, they react to the situations of their users at a given moment in time. One example for such environment is visitor’s guides in cultural heritage sites, supporting visits of individuals or small groups, such as families or friends. In such environments, it is well known that interaction among visitors enhances the overall visit experience. Recently, some research prototypes of visitor’s guides have started supporting such interaction through textual communication services embedded in them. However, these applications have so far been developed separately in an ad-hoc mann er, despite common features and infrastructures they share. The research described here generalizes communication services offered by different visitor’s guides and suggests a systematic and generic framework for de- veloping context-aware communication services for visitor’s guides. The specific communication services are ab- stracted into a d omain model, later used in pra ctice for adapting and tailoring the differen t concepts to the specific re- quirements of the applications. The framework is demon strated in the specific setting of a multi-ag ent museum visitor’s guide system. We also show that the suggested framework is not limited to the specific museum visitor’s guide system but may facilitate the development of context-aware communication applications in general. Keywords: Communication Services, Context Aware Communication, Visitor’s Guides, Domain Analysis 1. Introduction In the past decad e, when mobile technology h as matured enough, many research prototypes of context aware mo- bile tour guides and museum visitor’s guides appeared, aimed at providing museum visitors with personalized and context aware information. Most of the works fo- cused on exploring how the novel technology can be ap- plied for supporting individuals, mainly by providing context aware information and navigation support to vis- itors in museums [1-6]. In many cases, these systems sup- ported also interaction among visitors by providing them with some communication services. For example, Ran- tanen et al. [7] suggested enab ling users to “post” virtual messages for each other's attention at specific physical locations. Interaction among museum visitors is known to en- hance the visit experience [8]. Moreover, since a group visit is a common form in museums [9-11] and other cu- ltural heritage sites, the focus of the research now turns to supporting groups in these places [12,13]. In such sce- narios, technology-supported communication between museums visitors enables them to interact even when they are not in close proximity. As such, communication services should be considered not as a minor add-on, but as a central group-supporting service in the applications. Context awareness of such services makes them an in- tegral part of the vi si t expe ri ence for groups. To the best of our knowledge, all the works done so far in the area of context aware communication services have developed each service separately in an ad-hoc manner. This makes the development of each service a considera- ble effort, and limits the variety of services that can be offered by a specific system. We claim that these services can be considered a domain that exhibits a large variety of features, fulfilling different needs, but with common features that characterize all or most services in the do- main. Since all these communication services share com- mon basic characteristics, and possibly a common infra- structure, it would be reasonable to utilize the commo- nalities and all the possib le variations and provide a basis over which specific services can be easily developed. An easy development process will facilitate the inclusion of  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 269 a variety of communication services in Visitor’s Guide systems. Following this idea, this paper addresses contex t aware communication services in a systemic way, through domain analysis. While there is an abundance of research about context awareness in general, we focus on the com-munication services themselves. To this end, a ge- neric framework for defining and implementing context aware communication services has been developed, pro- viding a configurable infrastructure, which can be tai- lored to meet the various needs and requirements of spe- cific communication services. The framework has been implemented and demonstrated in an “active museum” environment, which is one example of a visitor’s guide. The environment is composed of a physical space con- taining exhibits and computation equipment (communi- cation infrastructure, computers, presentation devices, etc.). Specifically, the framework was applied within a multi-agent museum visitor’s guide system, developed as a part of the PIL1 project, an Italian-Israeli research col- laboration project dealing with Personal Experience with Active Cultural Heritage. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the background for the current research and reviews related work. Section 3 introduces the suggested framework for defining context-aware communication services, developed through analyzing the domain of in- terest. Section 4 reports an implementation of the frame- work in a museum visitor’s guide system, whereas Sec- tion 5 evaluates this framework through application case studies. Conclusions and future research directions are given in Section 6. 2. Background and Related Work This section provides background about context-aware services and applications in general, and communication services in visitor’s guides in particular. It motivates our work on context aware communication services and is a basis for gener a l i zat i on. 2.1. Context Aware Services and Applications Defining “Context” is a challenging task. Many resear- ches in the area of context awareness tried to define the context of a user in a way suited to their application needs. Dey et al. [14] claim that “while most people ta- citly understand what context is, they find it hard to elu- cidate”. They defined context as “any information that can be used to characterize the situation of an entity”, whereas an entity is defined as “a person, place, or object that is considered relevant to the interaction between a user and an application, including the user and applica- tions themselves”. This definition of context can be spe- cialized when dealing with a specific application or a fa- mily of applications. For example, Roffia [15] speciali- zed context definition to mobile cultural heritage applica- tions, stating that “context is a coordinate’s pair, named physical and logical coordinates. The physical coordinate represents the curren t user’s position and orientation. The logical coordinate represents information on the level of detail explicitly provided by the user.” A context-aware service is a service which uses con- text-related information and adapts itself to the changes of user’s and environment’s context dynamically and automatically. A large number of context aware applica- tions have been proposed under the vision of ubiquitous computing in general and visitor’s guides in particular. An early example of con-text-aware computing is the Olivetti Active Badge system [16]. Based on emitted in- frared signals from a badge, the system determined users location information. The most common usage of the system was by a receptionist who routinely used it while forwarding telephone calls from the main switchboard. The receptionist would look at the display of locations and then redirect the telephone call to the correct loca- tion. In the cultural heritage domain, th e “Guide” pr oject [17 ] provided an electronic handheld guide that enabled visi- tors to Lancaster access city information, create tailored city tours, and access interactive services, such as mak- ing ticket reservatio ns or booking hotel accommodatio ns. It also included communication services among visitors, reviewed later on in this paper. Context aware systems can also use physiological sen- sors like in StartleCam [18], developed at MIT media lab. This system is composed of a wearable video camera, a computer, and a sensing system, enabling the camera to be controlled via both conscious and preconscious events involving the wearer. A skin conductivity signal is mea- sured, related to the attention level. Traditionally, a wea- rer consciously hits record on the video camera, or runs a computer script to trigger the camera according to some prespecified frequency. The system offers an additional option: images are saved by the system when it detects certain events of supposed interest to the wearer. Developing context aware application is not easy and it draws a lot of research attention in recent years, as demonstrated by numerous conferences and workshops addressing this issue. Many attempts were made to pro- vide generic infrastructure for general context aware ap- plication development (to list just a few, see [14,19-24], some even for the specific setting of cultural heritage sites [25,26]. However, most of them focused on context modeling and infrastructure, rather than on the services themselves. Conversely, we focus on communication services, assuming that an application can use one of the 1http://www.cri.haifa.ac.il/connections/pil/  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 270 existing context modeling tools. 2.2. Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Context aware communication services have been in- cluded in various systems and especially in mobile con- text aware museums and city guides. Since such services are the focus of interest in our work, we surveyed 55 mobile tourist guide systems developed from the early 1990s until recently, only with respect to these services. Twelve of them provide textual communication services, which are of particular relevance to museums, where voice-based communication might not be welcomed. These systems are presented and discussed below in de- tail (grouped by type, in chronological order). They serve as a basis for analyzing and defining the domain of in- terest. 2.2.1. City Guides The Campiello system [27,28] aims to encourage the creation of connected communities in cultural towns. Using paper-based interfaces, Campiello enables the vis- itors to add information to a personal diary. These pages can be printed or faxed in order to be processed later. Furthermore, people can post their paper forms to large screens, and they can immediately view the newest input to the system together with others, to get immediate feedback on their input. Smart Sight [29] is a voice activated tourist gu ide sys- tem. It provides its visitors with “Tourist Diary” to help them organize their trip experience. When the tourist arrives at a point of interest, the system logs the position and time retrieved from the GPS and system clock. The tourist can ask the system to take a pictur e or digital vid- eo clip, and to add captions to the picture or dictate the description or comments during his/her visit at the point of interest. After the tourist finishes visiting the site or the day ends, he/she can ask the system to generate an HTML document based on the stored information. GUIDE [17,30] an electronic handheld tour guide al- ready introduced in Section 2.1, provides its users with personalized location aware information. It also enables visitors to send and receive messages to/from compa- nions, sharing their experiences with others. LoL@ [31] is a mobile electronic tour guide designed for tourists visiting the city center of Vienna. It provides predefined tours through the city center, information about the sights, navigation and routing, and an electron- ic tour diary. All visited places are automatically in- cluded in a tour diary stored on the application provider’s server. Additionally, users can include comments and private data like digital photographs. The diary can be retrieved after returning from the trip and can be ac- cessed by people staying at home during the trip. As fu- ture work the authors suggest to consider immediate messages to be sent between visitors during their tour (real time tour reporting). 2.2.2. Museum Guides CyberGuide [1,32] is a mobile, context aware tour guide that allows its users to send messages to exhibit owners and to report their location to a central server, accessible by others. Hippie [33] is a nomadic museum guide developed within the HIPS (Hyper-Interaction within the Physical Space) project [34]. It allows its users to take notes and annotate visited exhibits in order to store personal expla- nations or bookmarks av ailable during the visit. It fu rther supports sending immediate messages that can be di- rected to a dedicated addressee, such as family or group members in a museum, or to a specified full e-mail ad- dress, to contact a remote user. Exploratorium Guidebook [35], a location aware visi- tor’s guide developed for the Exploratorium in San Fran- cisco2, provides two communication functionalities, named “rememberer” and “communicator”. The first one provides the visito rs with means to build a reco rd of their experiences which they can consult during and after their visit, while the second one helps visitors communicate by electronic bulletin boards for individual exhib its, instant- messaging, and/or beaming information between hand- held devices. The researchers conclude that their remem- bering service may have value for personal and social uses. They also conclude that people seem to enjoy help- ing each other and discussing the exhibits, and this seems to encourag e additional interaction with the exhibits. MUSE [36], a location aware museum guide, allows visitors to mark the currently disp layed screen or to use a built-in camera to take a picture of what they are look ing at and update a “visit memory album”. At any time, ei- ther during or at the end of the visit, the visitors can mo- dify the memory album by deleting some selected items, re-ordering them, or includ ing co mments and annotatio ns. The final album can be saved on CDs, which represent the “memory” of the on-site visits. Virtual Heritage [37] is the focus of a research that ex- plores the possibility of using virtual reality in order to enrich visitors experience on sites. The system also al- lows visitors to take notes and exchange information with peers in a chat-like mechanism. MOMO [38] allows visitors to communicate and send messages to other visitors, and to see the names of visi- tors that already visited a specific artwork, in order to share similar interests at the museum or to keep in touch more easily. The researchers claim that the messaging feature is the main poin t of the social interaction because 2http://www.exploratorium.edu/  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 271 it allows visitors to communicate and to interact with the rest of the museum visitors, either by sending messages individually or by sending the same message to all the members of a group. The exSite museum visitor’s guide, made by ESPRO3, offers MyCollection, a service that allows its users to mark artworks of interest and select later on objects to be printed at the museum shop. 2.2.3. Mess a gi ng Se rvi ces InfoRadar [7] provides public and private location-based messaging and a novel radar interface for accessing mes- sages, where nearby messages can be tracked in the mo- bile device on a map. Such messages have an expiry time and visibility, and can be viewed remotely if the recipient is unlikely to visit the location of the message. The In- foRadar package contains a compact-size digital camera that can be connected via infrared to the InfoRadar main device and allows the users to attach a picture to a mes- sage being composed. 2.2.4. Summary of Communication Services Suppor t in Visitor’s Guides In summary, after reviewing 55 mobile visitor’s guides, we found that about 20% of them (i.e., 12 systems) pro- vide text-based communication services to their users. Table 1 presents the classification of these systems ac- cording to the types of commu nication services they pro- vide and the contextual aspects they consider: an imme- diate message sent to a recipiant, a virtual “Post-It” left at a location (e.g., personalized Geo-Note), or a “memory” —message to self (e.g., personal diary entry). The pre- vailing contextual aspects found in the cultural heritage guides involve Spatial, Temporal and Social aspects, whereas the contextualized information is an adaptation of the information deliv ered to the visitors based on con- textual aspects. As can be seen, the various applications, which repre- sent a variety of communications services suggested by Visitor’s Guides, share some common features, but each has its uniqueness too. Looking at the services, most of them can be categorized either as immediate messages or diary-like applications and some applications provide more than one type of communication services. As far as contextual aspects, most of them are location aware, where about half provide contextualized information. Most of them also have some form of social awareness (that is tightly coupled with communication services). In the following section we use all this info rmation in order to get a generalized view of the domain under cons idera- tion. Table 1. Classification of the reviewed systems according to communication service types* and type of context. System Comm. service* Type of Context IPD Cont Info. Spatial Temp.Soc. City Guides Campiello# XX X Smart Sight X X X X GUIDE X X X LoL@ XX X X Museum Guides CyberGuide X X X HIPPIE XX X X X Exploratorium GuideBook XX X X X MUSE X X X Virtual HeritageX MOMO X X exSite X X Msg. serv. InfoRadar X X X X *Immediate (I), Post it (P) or Diary (D); #The type of context in the service provided by Campiello is not specif ic, and depends on the user’s cho ice 3. A Generic Framework for Developing Context Aware Communication Services As noted, the variety of systems is quite large. However, some guidelines constraining their common features can be outlined. First, each communication service has one sender and potentially several recipients, one of which may be the sender (e.g., in diary communication ser- vices). In most cases, the sender and recipient are all us- ers or visitors using the system to be developed and they are usually identified by IPs and/or names. The commu- nication service itself is characterized by its name, sub- ject, sending time, and the content to be sent. Each user (or visitor) may have different context attri- butes in various time periods. As already noted, these context attributes can be divided into four categories: 1) Contextualized Information includes general attri- butes regarding the visiting environment that the user (visitor) is exposed to, including physical objects and presentations. In active museums, the physical objects may be exhibits, and the presentations may be audio or video files about exhibits and exhibitions. 2) Spatial Context includes the current location and movement of the visitor. The spatial context is charac- terized by the area, the specific location (e.g., a specific exhibition in an active museum), direction (of move- ment), orientation (indicating where the visitor focus is 3http://www.espro.com/  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 272 and possibly the general view, and speed. 3) Temporal Context includes attributes such as cur- rent time, visit phase, phase start time, and visit duration. 4) Social Context refers to groups of users (visitors) and to the particular role of a user in the group, as well as aspects such as attitude and mood. Even if we do not use explicitly the term “cognitive context” it is clear we mean (and other systems may also implicitly aim) to take into account the physical and the perceptive, epistemic and possibly emotional state of the visitor. We have chosen this level of representation to accommodate various experiences; and also for our own work (see the following) we prefer not to be bound to a specific model, but just to propose the generic elements that can then be used at a higher level to provide a char- acterization of the cognitive context. Note that the context of a particular visitor changes over time during the visit. Furthermore, potentially, a user can change groups during the visit. Thus, context aware communication services should be able to refer to the current and past context of their users, both senders and recipients. Examples of involving contextual aspects of the sender include adding to a communication service the location of the sender or information regarding his/ her group. Considering the context of a recipient, mes- sages, for instance, are not sent to a recipient who has already visited the exhibit or left the museum. For sup- porting these, each context aware communication service is connected to different context objects, representing conditions on the sender, the recipients, and the envi- ronment. These context objects may be embedded in the service as contextual conditions and/or contextualized content. Contextual conditions define constraints on the delivery of a given message. They usually use at least the context of the recipient. Contextualized content, on the other hand, usually refers to the sender’s context to be in- cluded in the message. Contextual conditions can be further divided into pre- sent and future contextual conditions. Evaluation of pre- sent contextual conditions at run time determines wheth- er the message should be sent or not. They are evaluated once at delivery time. Future contextual conditions, on the other hand, should be dynamically evaluated with every change in contextualized data. Messages that have future contextual conditions will be delivered as soon as their (future) contextual conditions are satisfied. Regard- ing the types of messages defined above, immediate mes- sages have no future con textual conditions, whereas post- it services must have such conditions. Note that diary services are characterized by the equality between their sender and recipient. Tabl e 2 exemplifies how to specify context aware communication services in the suggested framework, whereas Figure 1 depicts the domain model of the suggested framework, expressed as a class di agram. Note that in general the domain model includes con- cepts that are not specific to visitor’s guides. The only part that is specific to visitor’s guides is the specialized context (con textualized info rmation, spatial co ntext, tem- poral context, and social co ntext). In addition, th e specia- lized context aware communication services in the model (i.e., immediate, post-it, and diary) rely on our analysis, which was done for that area. Hence, this list may not be complete when considering other application areas. 4. Implementation of the Generic Framework in Active Museums As seen in the domain model, there exists a solid com- mon basis to the various communication services that can be offered in visitor’s guides. We propose to utilize this understanding of the commonality and variability to en- able easy development of a variety of services that may be required by different applications. These services will be provided by configuring a common and generic com- munication service infrastructure. This way, when spe- cific applications are developed, specific communica- tion services can be rapidly provided as configurations of the generic service. Such architecture can streamline the development process of new applications that require Table 2. Context aware communication services in the suggested framework. Communication Service T* present condition# future condition content Send a message to all the users in the sender’s group who have not visited the area in which the sender is visiting now, calling them to visit this area I Group (recipient) = Group (sender) AND NOT Area (sender) in VisitHistory. Area (recipient) Area (sender) Send a message to all the users in the sender’s group who have not visited the exhibit the sender is visiting now to watch this exhibit as soon as they enter its area, but only if this happens in the next 5 minutes P Group (recipient) = Group(sender ) AND NOT Exhibit (sender) in VisitHistory. Exhibit (rec ipient) Area (recipient) = Area (sender) AND Current Time (recipient) Message.SentTime + 5 Exhibit (sender) Remind the sender regarding the area in which he/she is visiting now D sender = recipient Area (sender) *Immediate ( I) , P ost it (P) or Diary (D); #VisitHistory refers to the past c ontext of a user (sender or re cipient).  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 273 Figure 1. A domain model of context aware communication services in visitor’s guides. context aware communication services. Considering museum visitor’s guides as a wide and interesting sub-area of visitor’s guides, we have develo- ped a tool that allows its users (application developers) to define and implement communication services to be used as part of their applications automatically. The specific communication services are specialized classes, defined as configurations of the generic context aware communi- cation service class from Figure 1. These service classes are defined using a Service Configuration tool which yields XML files, specifying the exact configuration of the communication services at hand (including their con- textual conditions and their contextual content). The XML definition files are then used as inputs by a Com- munication Generator tool that generates the specific services for the used communication infrastructure. Nev- ertheless, the user interface and the actual logic of each generated communication service have to be developed individually to meet the particular requirements of the service. In our case, the services themselves are generat- ed as agents in a multi-agent system that has been devel- oped as part of the PIL project [13], a multi-agent mu- seum visitor’s guide system. This system uses Loud- Voice agents’ communication infrastructure [39,40] and  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 274 contains five components (see Figure 2): 1) a Spatial In- formation Broker that reports the visitor’s positio n perio- dically, integrating positioning information from differ- ent sources (currently Infrared and WiFi); 2) a Presenta- tion Composer that provides presentations to the visitor, based on the current location and taking into account the visitors’ inferred preferences; 3) a User Modeler agent that keeps track of the visitors’ preferences based on their behavior; 4) a Communication Services Agent that pro- vides communication services to the visitors; and 5) a User Assistant (Device Interface) agent which is installed on the user’s PDA and provides the user interface to the system (information presentation/user actions). For specific service definitions, the “communication services generator” interprets the XML communication definitions and generates the required communication services as specialized agents. Note that the generic ser- vice idea is not limited to a specific infrastructure. It can be implemented as a web service, over a multi-agent communication infrastructure, or through other commu- nication mechanisms. In general, it can be implemented over any communication infrastructure that supports the definition of the generic model, as will be discussed later to show the generality of the framework. The communication service development and usage process includes four consequential p arts, participating in different life-cycle stages and depicted in Figure 3: 1) At design time, the communication services, as re- quired by the application, are defined using the Commu- nication Service Definition tool, producing an XML communication services definition file. 2) At application development time, specific applica- tion that includes the code for using the communication activities (usually user interface that will use the com- munication service) is developed. It includes requests for sending or receiving services as defined by the XML configuration file (at design time). 3) At runtime initialization stage, the communication services are automatically created by the communication service generator, ba sed on the XML-b ased conf igur ation file produced at design time. 4) After initialization of runtime, active users utilize the communication services through the user interfaces. Any operation, either sending or reading a specific mes- sage is invoked by a user activating the appropriate ap- plication that was developed for this specific communi- cation service. The communication itself as well as the collection and interpretation of contextual information required for the service are provided by the generic in- frastructure. 5. Demonstration and Evaluation of the Generic Framework This section demonstrates the usage of our generic framework in four communication services: SMS (i.e., immediate messages), Post-It, Memories (i.e., diary), and Visit Reminder (also diary) services. Then, we evaluate the generality of the framework by showing how it can be applied to produce the services reviewed in Section 2. 5.1. Demonstration: SMS and Post It-Like Services We start with presenting the implementation of two ser- vices which have already been integrated into the PIL system, namely the SMS and Post it-like services. While SMS is a relatively simple immediate message service, the virtual post-it service is more complicated, with a major role to context awareness. The implementation in- Figure 2. The museum visitor’s guide architecture in PIL.  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 275 Figure 3. The suggested communication service development and usage process. cluded the possibility to select and send a message from a set of predefined messages. This is important in this case since museum visitors should focus their attention on the exhibits and not on the guide itself. 5.1.1. Requirements and Usage Scenar io s The SMS-like messages can be classified as immediate messages. The requirements from this type of services are that messages should be delivered immediately after sending, taking into account the current context of the sender and optionally of the recipient. In the PIL project, when the user is in a certain position, next to a specific exhibit and wants to send a message to a friend, the user selects a message from a list of predefined ones, includ- ing: 1) “You should see this exhibit”, 2) “You should visit this area”, 3) “You should skip this area”, and 4) “Could you please come here?” (Without giving any specific details) If, for example, the sender selects the message “you should see this exhibit”, the message will be delivered to a recipien t if he/she has not yet visited th e sender’s current exhibit, and the information about “this exhibit”, like its name and an image, will be added au- tomatically by the system to the delivered message. This information may possibly include a path on a map that leads the recipient to the sender’s location as well (since the two positions, this of the sending user and this of the recipient are known to the system). Like SMS, Post-It services are context-based virtual notes whose delivery depends on the context of the send- er and recipient. Unlike SMS, the post-it note may be virtually attached to an exhibit that the sender is looking at, and the message will be delivered to the recipients only when and if they visit this ex hibit (and optionally if additional contextual conditions are fulfilled). Post-It services may take into account the visit history of the recipient, the current context of the sender, and the social context of both sender and recipient. The content of a delivered message is enhanced by the sender’s current  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 276 contextual information. As an example to a Post-It note consider: “Remember this exh ibit—I’d like to talk to you about it later”. The message will be delivered to the reci- pient if he/she arrives at the sender’s (current) location within a given time period (the message expiry time), and if he/she has not yet visited the sender’s current ex- hibit. Furthermore, information about “this exhibit” will be added to the message. This information will suggest the recipient to choose the exhibit recommended by the sender when (and if) visiting the location where the post- it is attached. 5.1.2. Configuration Pr ocess In order to define these two services, fulfilling the abov e requirements, the developer of an application configures a generic communication service, using a configuration tool developed for this purpose The result of the process is an XML definition file, where each communication service is defined as a class element with a unique iden- tifier and two sub-elements, conditions and content. Fig- ure 4 represent s the SMS de finition fil e . The conditions element includes information on pre- sent and future conditions to handle the current commu- nication service, as well as possibility to initializing va- riable values needed for defining contextual content or conditions. The SMS configuratio n file (Figure 4) inclu- des only present conditions, specifying that the recipient should be in the sender’s group and has not visited the area the sender is currently visiting. The Post-It configu- ration file includes both present and future conditions. The present conditions require that the recipient is in the sender’s group and has not visited the exhibit the sender is currently visiting; future conditions specify that the message has to be delivered to a recipient that arrives at the area the sender is currently in within 5 minutes. The content element includes the contextual element in the actual content of the communication service. The SMS service should augment the area of the sender (name, picture) into the message, while the Post-It mes- sage should include the exhibit information (current ex- hibit of the sender). The XML file is used during system initialization to generate the relevant communication services, as described below. 5.1.3. Runtime Ap plicati on In addition to the configuration definition file, an appro- priate user interface for these services has been devel- oped. For the SMS service, the application is executed in runtime based on the user’s selection of a predefined message (listed at the beginning of Section 5.1.1, and on the second screen from left in Figure 5). At initialization time, i.e., when the system is initia- lized, communication service agents are created follow- ing the definitions in the configuration file for every logged-in user. At runtime, while the visitors are using the guide, they can press the button of the envelope (the icon in the left bottom of Figure 5) in order to open a list of predefined text messages (Figure 5, second screen from the left). After the sender chooses the de- sired message from the list (“you shou ld see this exhibit” in this case), a list of other visitors’ names appears (Fig- ure 5, third screen from the left) to enable the sender to choose the actual recipients (one or all). A final screen includes the text message and recipient names to confirm sending (Figure 5, rightmost screen). In the example the sender recommends the recipient to see the exhibit at which she is currently looking. Upon delivery, a button at th e bottom of th e screen no- tifies a recipient that a message is received (the icon in Figure 6, left screen). If he/she chooses to read the message by pressing the button, then a list of sender names appears (Figure 6, second screen from the left), and when one is selected, a list of messages sent by that visitor is presented (Figure 6, third screen from the left). Finally, after choosing one of the messages, a new screen with the delivered message appears. Recall that the con- tent of the delivered message depends on the sender’s context. Specifically, the phrase “this exhibit” is replaced with the name of the exhibit that was recommended by the sender, and an image of this exhibit is added to the message (Figure 6, rightmost screen). Runtime application of the Post-It service is similar to that of the SMS, with the following differences. First, the list of possible messages is slightly different (see Figure 7 left side). In the given list, messages 4 and 5 match the configuration specified in Figure 5, where the message is attached to an Area and bearing the information of an Exhibit in that area as its content. In contrast, the first three messages (1, 2, and 3) relate to a slightly different configuration. These messages are supposed to be at- tached to an Exhibit rather than to an Area, and their content provides a recommendation about some Presen- tations rather than Exhibits. This would mean different <CommunicationServices> <class id="send"> <conditions Condition ="(Group (sen der)==Group(recipient s )) AND (NOT(X(sender) in Y(recipients)))" FutureCondition = "null" VariablesInit = "X=Area, Y=History[Area]"/> <Content attrs = "X(sender)"/> </class> </CommunicationServices> Figure 4. The XML configuration file for the SMS-like im- mediate message service.  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 277 Figure 5. Sending a context aware immediate message. Figure 6. Receiving a context aware immediate message. default values given to the variables X, Y, and Z in the XML configuration file (X = Presentation, Y = History [Presentation], Z = Exhibit). 5.2. New Services Implemented as Proof-of Concept In addition to the above described SMS-like and Post-It services, two other services, Memories and Visit Remin- der, were simulated using the generic framework, but not implemented as part of the visitor’s guide system. The Memories service adds contextual information about the environment to the visitor’s annotations; the contextual information may refer to any type of object, such as exhibition, area, exhibit, and presentation. It ena- bles the visitor to write comments in free text about ob- jects of different types in the museum. This service is classified as a diary service. The “Visit Reminder” service, which is also a diary service, provides a sequence of reminder services. Before the visit starts, the visitors may choose a list of locations that they plan to see during the visit within a specific time frame. The service has the goal to remind them “Don’t miss” what they planned to see or listen to within the predefined time frame. 5.3. Assessing the Generality of the Framework Above, we described four services which have been im- plemented or simulated on the basis of the proposed framework. This framework allows users to easily define and implement communication services in various appli- cations, without the need to worry about the specific te- chnical details, as demonstrated by the application des- cribed earlier. To assess our claim that this framework supports a wide range of communication services, we follow a descriptive evaluation method, called scenarios [41], which requires constructing detailed scenarios around the suggested artifact (the generic framework in our case) to demonstrate its utility. In particular, Table 3 show s how the sugg ested frame- work supports all the communication services that were provided by the 12 systems reviewed in Section 2. The second column describes the communication services as provided by the different systems (Imm abbreviates im- mediate messages). Columns three to six describe how the same service can be defined using the generic frame- work and the last column comments on the status of the  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 278 Table 3. Implementation of the various communication services using the generic framework. System Comm. Service T* present conditioncontent Comments Campiello Taking notes D sender = recipient none Information is recorded first Publishing them to all the visitors I None none Then it may be presented over a large screen to all visitors—the presentation is part of the application. Smart sight Keeping a tour diary D sender = recipient Exhibit ( se nd er), Area (sender), Visit Phase (sender) Specific visited locations and time are recorded. Creating the tour diary its elf is left to the application developer. Guide Sending messages to group members I Group (recipient) = Group(sender) none Very brief description of communication services LoL@ Automatically adding visited points of intere st t o a tour diary, stored on the provider’s server D Sender = recipientArea (sender) Contextualized messages are sent to “self”. The created diary includes the l ocations visited. Creation of the Album is left to the application developer. The information may be viewed by others as well. Sending messages to group members I Group (recipient) = Group(sender) none Immediate messages to group members are in future work. Cyberguide Sending messages to exhibit owner I none Exhibit (sender) Context aware communication services are desired, but not implemented in the system. Sending messages to visitors I Group (recipient) = Group(sender) Area (sender) Hippie Taking notes on p oi nts of interest D sender = recipient Area (sender) Notes can be added to presentations. Sending messages to other group members I Group (recipient) = Group(sender) none Immediate messages can be sent to friends. Exploratorium GuideBook Rememberer: keeps a visit record D sender = recipient Exhibit (sender) Specific visited physical obje cts are recorded. Communicator: Instant messaging I None No detailed description is pro vided. Messa ges are sent to “friends”. Muse Memories channel: marking exhibits of interest or taking digital pictures D sender = recipient Area (sender) Contextualized messages can be sent to “self”, where the current presentation is marked and recorded. Linking and editing are part of the application development. Virtual Heritage D sender = recipient No detailed d e sc ription is provided. A text editor is used for taking notes Momo Instant messaging between group members I Group (recipient) = Group (sender) There is no deta iled des cription of the features. exSite Marking exhibits of interest for use at the museum shop D sender = recipient Exhibit (sender) It allows marking specific physical objects (exhibits). Info Radar Leaving and reading location-based messages P None Area (sender) Messages are attached to locations. Can be sent/read remotely *D-diary, I-im mediate, P-post it. services’ implementation and what remains for the appli- cation developer’s responsibility. Empty cells mean that there was not enough information about the service to determine its contextual conditions or content. Looking at the different rows of the table, we can see how every service in the reviewed systems can be im- plemented using the generic framework. The diary ser- vices, for example, namely those in Campiello, SmartSite, LOL@, HIPPIE, Exploratorium, GuideBook, MUSE, and exSite, are all characterized by a contextual present con- dition specifying that the sender equals to the recipient and no contextual future condition. While the first characterization is essential to all diary services, the absence of contextual future condition is a  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 279 matter of current reality: no system has yet implemented a diary service with post-it capabilities (e.g., a personal reminder service). Furthermore, all diary services in the reviewed systems partially support spatial context (in the form of area) and contextualized information (in the form of exhibits); they do not support temporal neither social context awareness. Regarding immediate messages, one can see that the reviewed systems are at most social aware (referring to the sender’s and recipient’s groups) while delivering the messages. In addition, the messages themselves may contain spatial context (in the form of area) and contex- tualized information (in th e form of exhibits). Our frame- work can provide more sophisticated immediate messag- ing (e.g., sending messages only to the visitors who have not yet been at the location of the sender are currently at a specific location). Finally, the post-it service of Info Radar refers to the location (area) of the recipient, with respect to the sender, and embeds spatial-related and con- textualized information in the message to be sent. Again, while our generic framework supports these services, it is also capable of supporting more complicated post-it me- chanisms. While the basic context aware communication mecha- nisms are common, the applications themselves differ. As a result, a large variety of applications can be developed using the suggested framework. Note that the contextual conditions used in all the reviewed systems are quite sim- ple and only partially use the attributes proposed by our framework. Another dimension of the generality of our framework is its independence of the underlying infrastructure type. The configuration is expressed by means of an XML file, which makes it possible to use with different kinds of infrastructures over which these applications can be de- veloped. Yet, it requires an interpreting componen t, as an interface with the infrastructure. 6. Conclusions and Future Work Context aware communication services can play an im- portant role in supporting visitors in cultural heritage sites, as demonstrated by the abundance of related work that exists. Our work shows that although there may be many “flavors” to communication services, they all share a small set of common characteristics. This calls for a standard definition of such services that can be applied in any application, so developers can define the specific “flavor” of services according to their system require- ments, while reusing the common, generic infrastructure. The framework suggested in this paper focuses on communication services. It defines two dimensions for classifying context aware communication services: the communication service type (namely immediate, post-it, or diary) and the supported context type (i.e., contextua- lized information, spatial context, temporal context, and social context). Given the abundance of context aware toolkits, it is possible to use any context management tool kit that can provide the required contextual data. This framework has been implemented using two main components: a service configuration tool and a generic communication generator tool. The generic communica- tion service relies on the LoudVoice multi-agent system. However, specific application components that tailor user interfaces to the communication services have to be de- veloped separately for each communication service type. Since our conceptual framework is not dependent on a specific communication solution, future work will focus on developing a web service-based “Communication Generator” to allow applying the newly suggested frame- work to a widely used technology. Although analyzed and ev aluated in the context of Vis- itor’s Guides, the suggested framework aims at facilitat- ing the development of context-aware communication services in general, which nowadays is considered to be a complex and time-consuming task due to the lack of an adequate infrastructure support [42]. Furthermore, consi- dering the increasing number of applications providing context-aware communication services to their users and the heterogeneity of communication services which an application may use, such a framework can be genera- lized for context-aware communication services in active environments in general. Furthermore, the contextual as- pects can be extended to include, for instance, cognitive context of the senders and recipients, which includes their believed knowledge at a certain time. Indeed, this kind of context may partially be addressed in the current frame- work by relating to the visit history and assuming it represents what the visitor knows. In order to address a richer range of contextual aspects, developers may con- sider using a generic tool like the tool developed by [14] and others, and by doing so to focus on application speci- fic aspects, rather than developing ad-hoc context aware communication services. As for the futur e, we may use the framewo rk presented here and apply it to context aware applications in general. Consider, for example, the area of context-aware shop- ping recommendations. Different applications can be developed in this domain, such as location-aware recom- mendation or recommendation of products that are sup- plementary to a product recently bought. These applica- tions, as well as others, may share a common infrastruc- ture. Similarly to our framework, a service configuration tool can be designed and implemented in that area. Such service configuration tool would build on a domain mod- el which captures the unique features and relevant con- textual attributes in that domain, and would streamline  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 280 the development of such applications. 7. Acknowledgements The research was supported by the collaboration project between the Caesarea-Rothschild Institute at the Univer- sity of Haifa and FBK/irst in Trento and by FIRB project RBIN045PXH. Experimentation was conducted at the Hecht museum at the University of Haifa, Israel. REFERENCES [1] P. Marti, A. Rizzo, L. Petroni, G. Tozzi and M. Diligenti, “Adapting the Museum: a Non-Intrusive User Modeling Approach,” Proceedings of the 7th International Confe- rence on User Modeling, Banff, 20-24 June 1999. pp. 311-313. [2] R. Oppermann and M. Specht, “A Context-Sensitive No- madic Exhibition Guide,” Proceedings of the 2nd Sympo- sium on Handheld and Ubiquitous Computing, Bristol, 25-27 September 2000, pp. 31-54. [3] A. Bright, J. Kay, D. Ler, K. Ngo, W. Niu and A. Nuguid, “Adaptively Recommending Museum Tours,” Proceed- ings of Workshop on Smart Environments and Their Ap- plications to Cultural Heritage, Tokyo, 11 September 2005, pp. 29-32. [4] D. Petrelli and E. Not, “User-Centred Design of Flexible Hypermedia for a Mobile Guide: Reflections on the Hy- perAudio Experience,” User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, Vol. 15, No. 3-4, 2005, pp. 303-338. doi:10.1007/s11257-005-8816-1 [5] L. Aroyo, N. Stash, Y. Wang, P. Gorgels and L. Rutledge, “Chip Demonstrator: Semantics-Driven Recommendations and Museum Tour Generation,” Proceedings of the 6th International Semantic Web Conference, Busan, 11-15 November 2007, pp. 879-886. [6] R. Damiano, C. Gena, V. Lombardo, F. Nunnari and A. Pizzo, “A Stroll with Carletto: Adaptation in Drama- Based Tours with Virtual Characters,” User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, Vol. 18, No. 5, 2008, pp. 417- 453. doi:10.1007/s11257-008-9053-1 [7] M. Rantanen, A. Oulasvirta, J. Blom, S. Tiitta and M. Mäntylä, “InfoRadar: Group and Public Messaging in the Mobile Context,” Proceedings of the 3rd Nordic Confe- rence on Human-Computer Interaction, Tampere, 23-24 October 2004, pp. 131-140. [8] G. Leinhardt and K. Knutson, “Listening in on Museum Conversations,” AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, 2004. [9] J. Falk and L. Dierking, “The Museum Experience,” Whalesback Books, Washington, 1992. [10] S. Bitgood, “Environmental Psychology in Museums, Zoos, and Other Exhibition Centers,” In: R. Bechtel and A. Churchman Eds., Handbook of Environmental Psy- chology, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2002, pp. 461- 480. [11] B. Gammon and A. Burch, “Designing Mobile Digital Experiences,” In: L. Tallon and K. Walker Eds., Digital Technologies and the Museum Experience Handheld Guides and Other Media, AltaMira Press, Lanham, 2007, pp. 35-60. [12] O. Stock and M. Zancanaro, “PEACH: Intelligent Inter- faces for Museum Visits,” Cognitive Technologies Series, Springer, Heidelberg, 2007. [13] T. Kuflik, O. Stock, M. Zancanaro, A. Gorfinkel, S. Jbara, J. Sheidin and N. Kashtan, “A Visitor’s Guide in an Ac- tive Museum: Presentations, Communications, and Ref- lection,” Association for Computing Machinery: Journal of Computers and Cultural Heritage, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2011. [14] A. K. Dey, G. D. Abowd, “Towards a Better Understand- ing of Context and Context-Awareness,” Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Handheld and Ubi- quitous Computing, Karlsruhe, 27-29 September 1999, pp. 304-307 [15] L. Roffia, “Context Related Information Sharing and Re- trieval in Mobile Cultural Heritage Applications,” Ph. D. Thesis, University of Bologna, Italy, 2004. [16] R. Want, A. Hopper, V. Falcao and J. Gibbons, “The Ac- tive Badge location system,” Association for Computing Machinery: Transactions on Information System, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1992, pp. 91-102. doi:10.1145/128756.128759 [17] N. Davies, K. Cheverst, K. Mitchell and A. Efrat, “Using and Determining Location in a Context-Sensitive Tour Guide,” Computer, Vol. 34, No. 8, 2001, pp. 35-41. doi:10.1109/2.940011 [18] J. Healey and R. W. Picard, “StartleCam: A Cybernetic Wearable Camera,” Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE Interna- tional Symposium on Wearable Computers, Pittsburgh, 19-20 October 1998, pp. 42-49. [19] K. Henricksen, J. Indulska and A. Rakotonirainy, “Mod- elling Context Information Pervasive Computing Sys- tems,” Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Pervasive Computing, Zurich, 26-28 August 2002, pp. 167-180. [20] F. Siegemund, “A Context-Aware Communication Plat- form for Smart Objects,” Proceedings of the 2nd Interna- tional Conference on Pervasive Computing, Linz, 18-23 April 2004, pp. 69-86. [21] C. Anagnostopoulos, A. Tsounis, and S. Hadjiefthymiades, “Context Awareness in Mobile Computing Environments: A Survey,” Wireless Personal Communications, Vol. 42, No. 3, 2008, pp. 445-464. [22] X. Zhang, J. Liao and J. Liu, “Open Middleware-Based Infrastructure for Context-Aware in Pervasive Compu- ting,” Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Computational and Information Science, Shanghai, 16-18 December 2004, pp. 85-92. [23] A. Dey, T. Sohn, S. Streng and J. Kodama, “iCAP: Inter- active Prototyping of Context-Aware Applications,” Pro- ceedings of the 4th International Conference on Pervasive Computing, Dublin, 7-10 May 2006, pp. 254-271. [24] Q.-S. He and S.-L. Tu, “A Lightweight Architecture to Support Context-Aware Ubiquitous Agent System,” Pro- ceedings of 9th Pacific Rim International Work- shop on Multi-Agents, Guilin, 7-8 August 2006, pp. 696- 701.  Generic Framework for Context-Aware Communication Services in Visitor’s Guides Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSEA 281 [25] O. Stock, M. Zancanaro, P. Busetta, C. Callaway, A. Krüger, M. Kruppa, T. Kuflik, E. Not and C. Rocchi, “Adaptive, Intelligent Presentation of Information for the Museum Visitor in PEACH,” User Modeling and User- Adapted Interaction, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2007, pp. 257-304. doi:10.1007/s11257-007-9029-6 [26] Z. Y. Yu, X. S. Zhou, Z. W. Yu, J. H. Park and J. H. Ma, “Imuseum: A Scalable Context-Aware Intelligent Mu- seum System,” Computer Communications, Vol. 31, No. 18, 2008, pp. 4376-4382. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2008.05.004 [27] A. Grasso, M. Koch and D. Snowdon, “Campiello—New User Interface Approaches for Community Networks,” Association for Computing Machinery: SIGGROUP Bul- letin, Vol. 20, No. 2, 1999, pp. 15-17. [28] A. Agostini, G. De Michelis, M. Divitini, M. A. Grasso and D. Snowdon, “Design and Deployment of Communi- ty Systems: Reflections on the Campiello Experience,” Interacting with Computers, Vol. 14, No. 6, 2002, pp. 689-712. doi:10.1016/S0953-5438(02)00016-4 [29] J. Yang, W. Yang, M. Denecke and A. Waibel, “Smart Sight: A Tourist Assistant System,” Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Wearable Computers, San Francisco, 18-19 October 1999, pp. 73-78. [30] K. Cheverst, N. Davies, K. Mitchell and P. Smith, ”Pro- viding Tailored (Context-Aware) Information to City Vis- itors,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Adaptive Hypermedia and Adaptive Web-based Systems, Trento, 28-30 August 2000, pp. 73-85. [31] M. Umlauft, G. Pospischil, G. Niklfeld and E. Michlmayr, “LoL@, A Mobile Tourist Guide for UMTS,” Journal of Information Technology and Tourism, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2003, pp. 151-164. doi:10.3727/109830503108751108 [32] S. Long, R. Kooper, G. D. Abowd and C. G. Atkeson, “Rapid Prototyping of Mobile Context-Aware Applica- tions: the Cyberguide Case Study,” Proceedings of the 2nd Annual International Conference on Mobile Compu- ting and Networking, New York, 10-12 November 1996, pp. 97-107. [33] R. Oppermann and M. Specht. “A Nomadic Information System for Adaptive Exhibition Guidance,” Archives and Museum Informatics, 1999, pp. 127-138. doi:10.1023/A:1016619506241 [34] G. Benelli, A. Bianchi, P. Marti, E. Not and D. Sennari, “HIPS: Hyper-Interaction within the Physical Space,” Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Multi- media Computing and Systems, Firenze, Vol. 2, 7-11 June 1999, pp. 1077-1078. [35] M. Fleck, M. Frid, T. Kindberg, E. O’Brien-Strain, R. Rajani and M. Spasojevic, “From Informing to Remem- bering: Ubiquitous Systems in Interactive Museums,” Pervasive Computing, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2002, pp. 13-21. [36] F. Garzotto, T. Cinotti and M. Pigozzi, “Designing Multi- Channel Web Frameworks for Cultural Tourism Applica- tions: The MUSE Case Study,” Archives and Museums Informatics, Toronto, 2003, pp. 239-354. [37] E. Farella, D. Brunelli, L. Benini , B. Ricco and M. E. Bonfigli, “Pervasive Computing for Interactive Virtual Heritage,” IEEE MultiMedia, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2005, pp. 46-58. doi:10.1109/MMUL.2005.54 [38] J. Jaén, J. Mocholí, J. Esteve, V. Bosch and J. Canós, “MoMo: Enabling Social Multimedia Experiences in Hy- brid Museums,” Proceedings of International Workshop of Re-Thinking Technology in Museums: Towards a New Understanding of People’s Experience in Museums, Li- merick, 29-30 June 2005, pp. 245 -251. [39] P. Busetta, A. Doná, and M. Nori, “Channeled Multicast for Group Communications,” Proceedings of the 1st In- ternational Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, Bologna, 15-19 July 2002, pp. 1280-1287. [40] P. Busetta, T. Kuflik, M. Merzi and S. Rossi, “Service Delivery in Smart Environments by Implicit Organiza- tions,” Proceedings of the 1st Annual International Con- ference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Systems: Networking and Services, Boston, 22-26 August 2004, pp. 356-363. [41] A. R. Hevner, S. T. March and J. Park, “Design Science in Information Systems Research,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2004, pp. 75-105. [42] G. Chen and D. Kotz, “A Survey of Context-Aware Mo- bile Computing Research,” Technical Report TR2000-381, Department of Computer Science, Dartmouth College, Hanover, 2000. |