Paper Menu >>

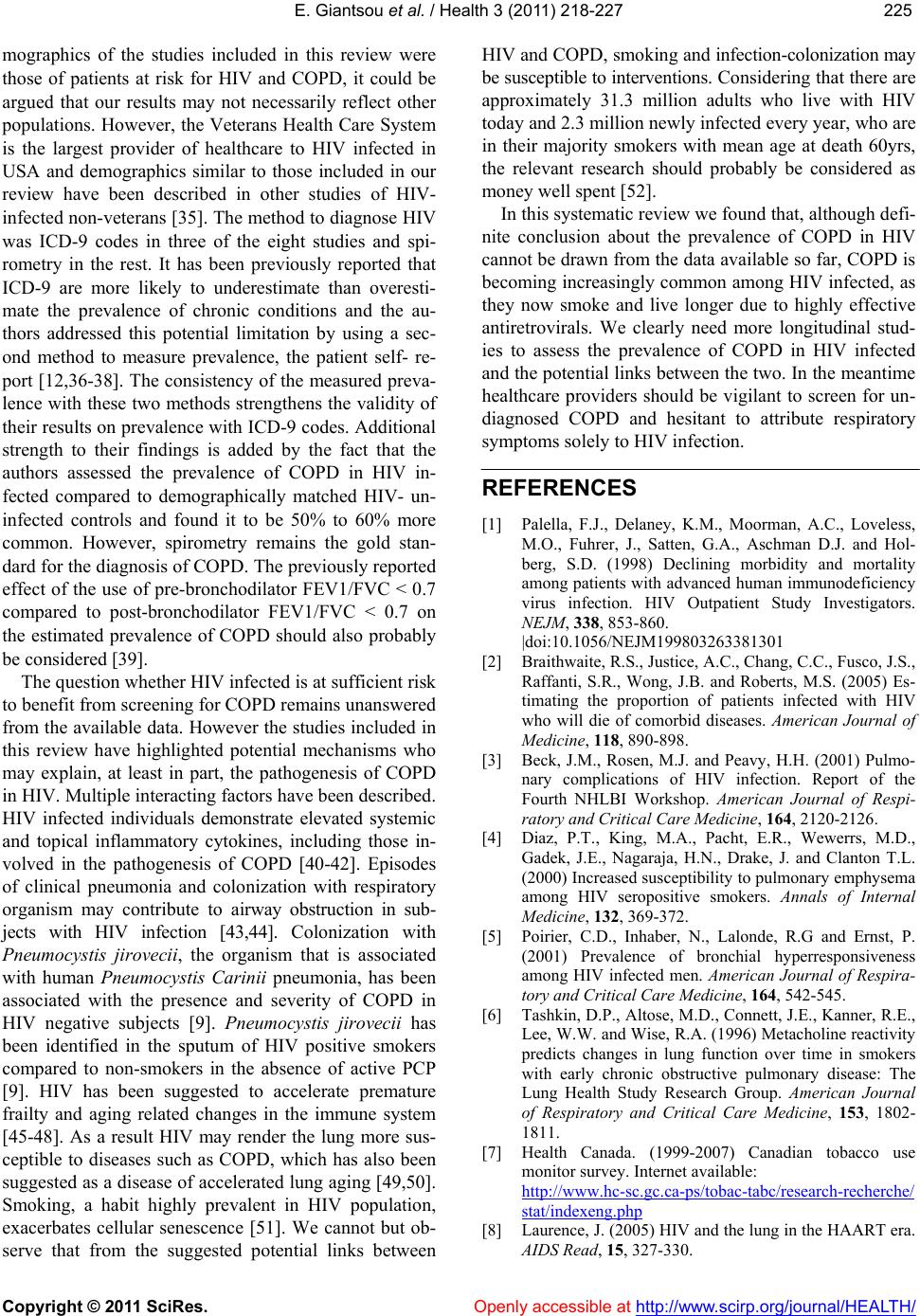

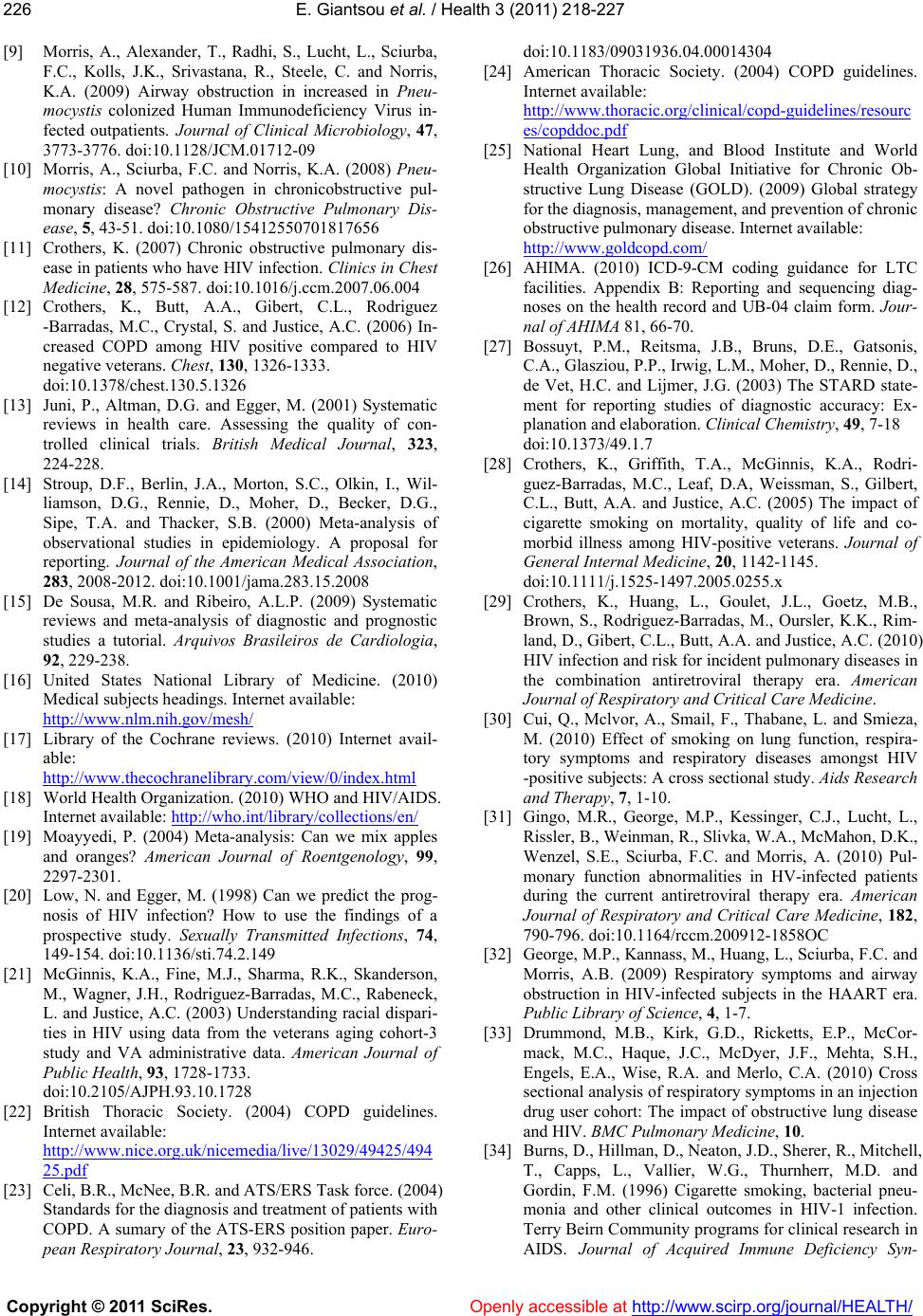

Journal Menu >>

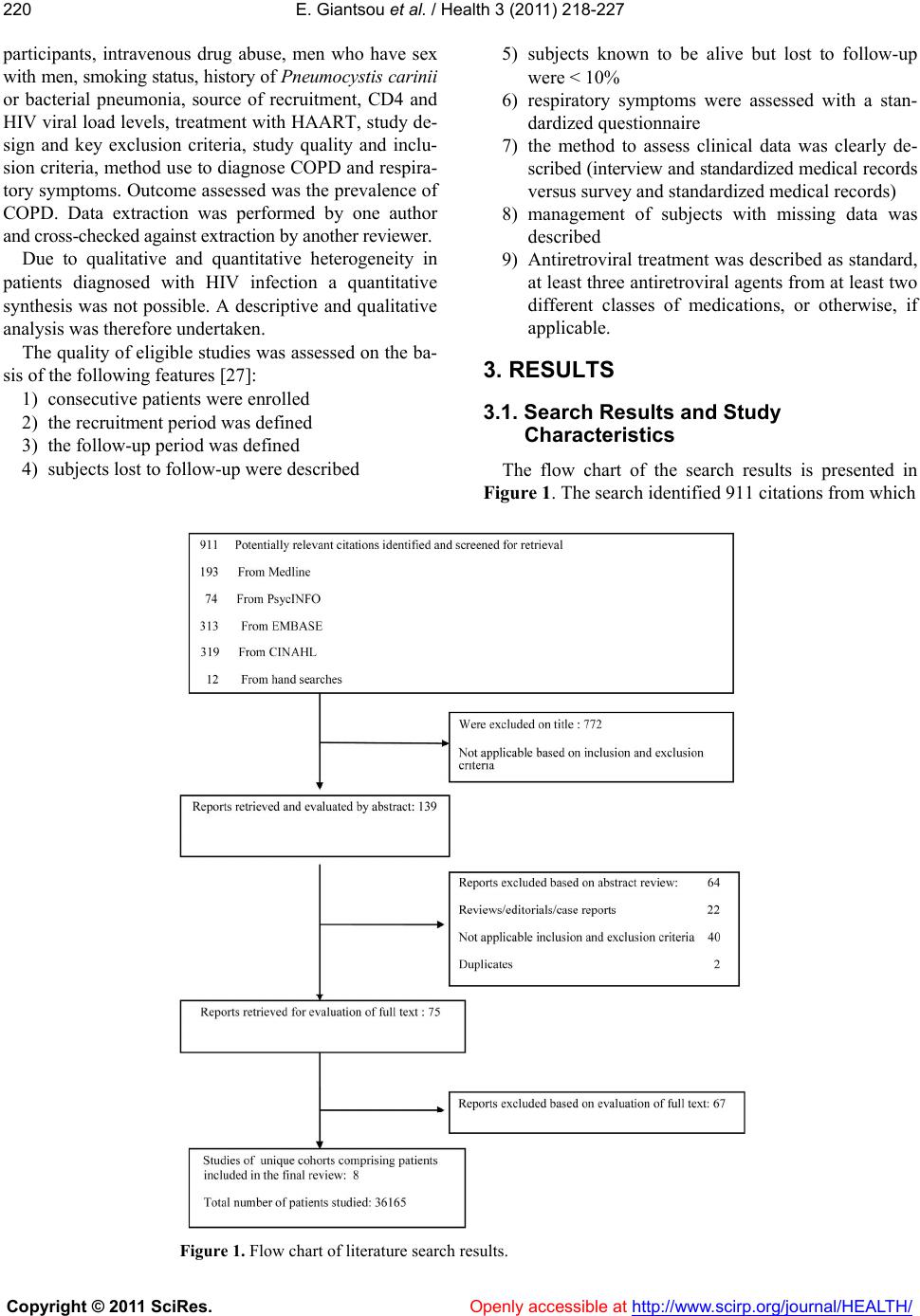

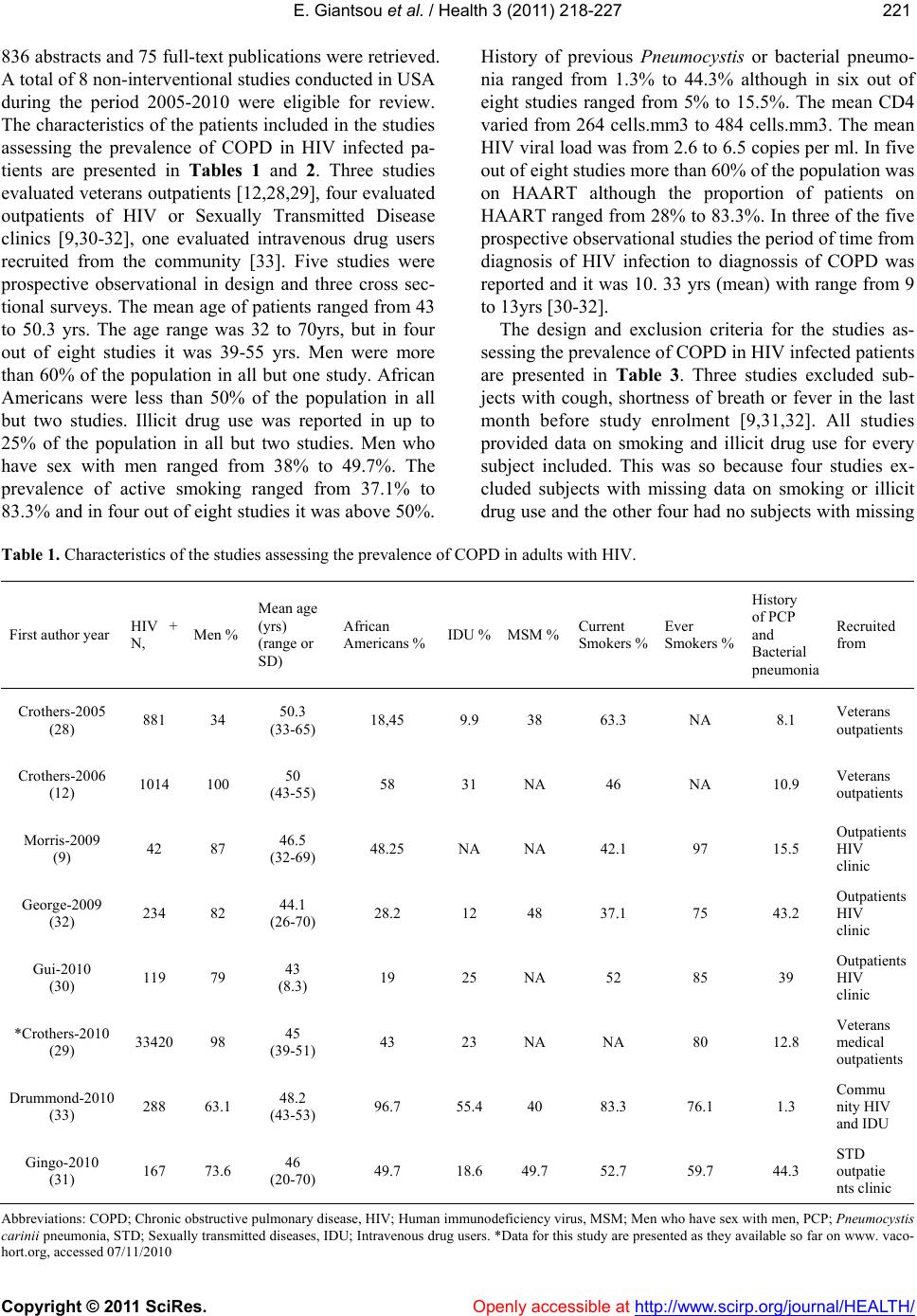

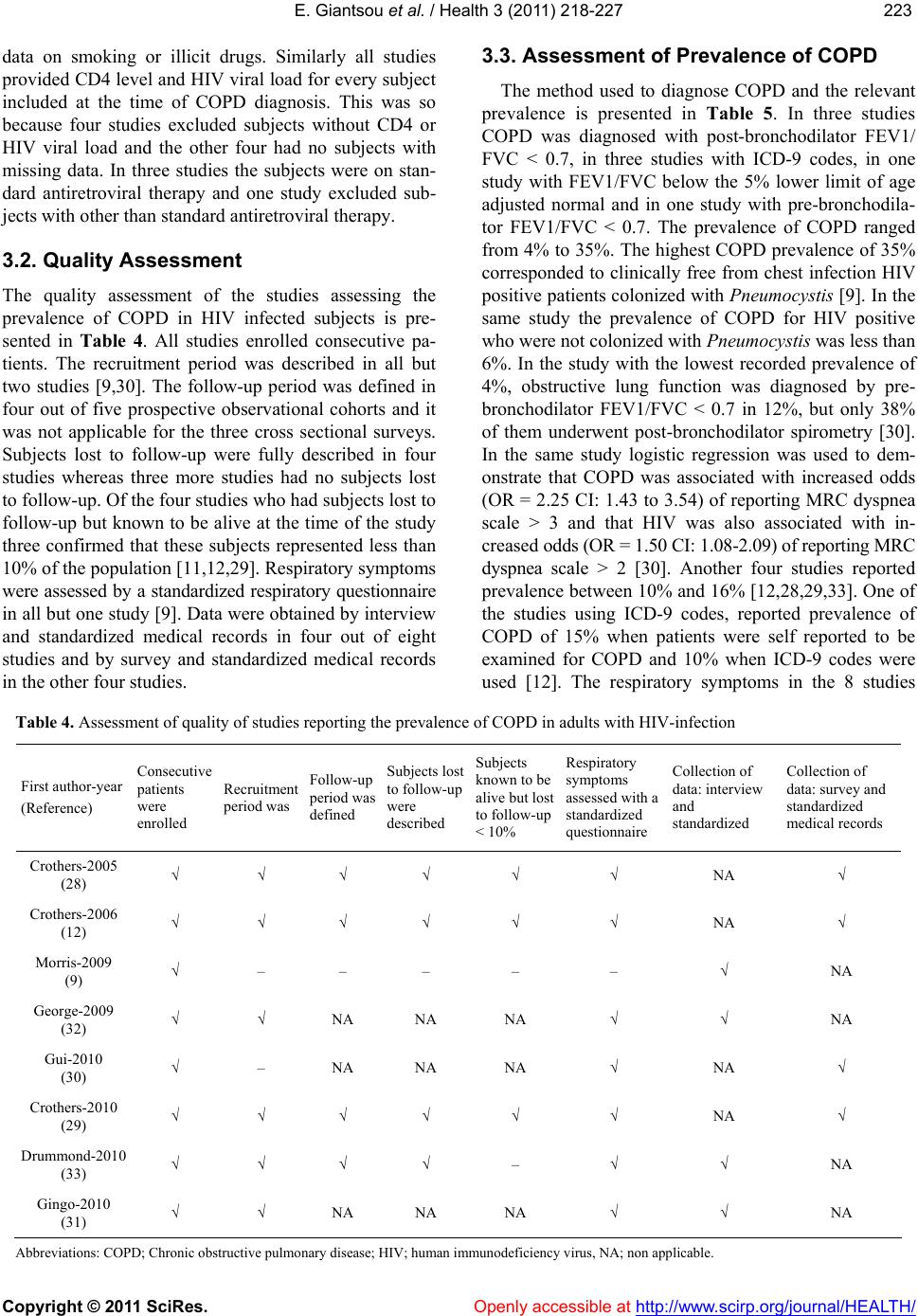

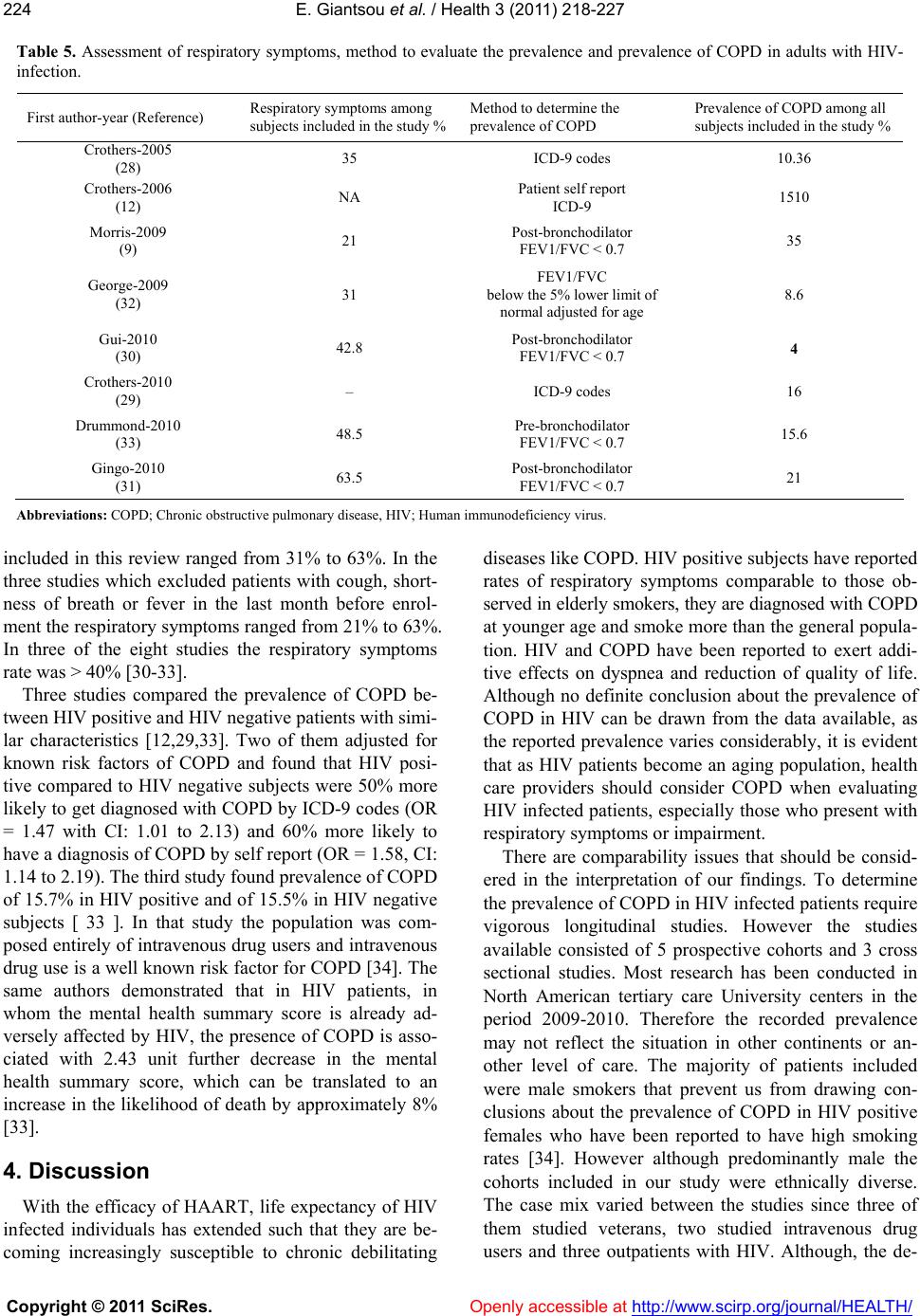

Vol.3, No.4, 218-227 (2011) Health doi:10.4236/health.2011.34039 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a systematic review Elpis Giantsou1,2*, Duncan Powrie2 1Acute Medical Unit, Southend University Hospital, Essex, England; *Corresponding Author: elpisgiantsou@yahoo.com; 2Heart and Chest Clinic, Southend University Hospital Received 29 January 2011; revised 20 February 2011; accepted 23 March 2011. ABSTRACT Objective: To determine the prevalence of chro- nic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in adults with Human Immunodeficiency virus in- fection (HIV). Design: Systematic review of Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO and ref- erences from identified papers. Study selection: Studies determining the prevalence of COPD in adults with HIV infection. Independent duplicate data extraction. Study quality was assessed in terms of whether consecutive patients were en- rolled, recruitment and follow-up periods were defined, <10% of subjects were lost to follow-up, subjects with missing data, method of COPD diagnosis and antiretroviral treatment were de- scribed. Data synthesis and results: Of the 911 citations identified, 8 North American studies conducted from 2005 to 2010 were reviewed. The demographics were: mean age 43 - 50.3yrs, >60% males, <50% African Americans, 37.1% - 83.3% active smokers, >60% on antiretroviral therapy. COPD was diagnosed by post-bron- chodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 in three studies, by International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) codes in three studies, by FEV1/FVC < 5% of lower adjusted normal in one and by pre- bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 in another study. The prevalence was 10% - 35%, except for one study that recorded prevalence of 4% by post- bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7, but <38% of patients with prebronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 had post-bronchodilator spirometry in that study. Conclusion: COPD is becoming increas- ingly common in HIV infected as they smoke and live longer due to efficient antiretrovirals. However, definite conclusions cannot be drawn and more longitudinal studies are needed. In the meantime health care providers should be vigi- lant to screen for undiagnosed COPD and hesi- tant to attribute respiratory symptoms solely to HIV infection. Keywords: HIV, COPD; Systematic Review 1. INTRODUCTION Effective antiretroviral therapies have improved the prognosis for patients infected with the Human Immu- nodeficiency Virus (HIV) [1]. The Collaborations in HIV Research–US (CHORUS ) cohort study reported a median survival of 20.4 years for HIV positive subjects, with mean age at death 60.4yrs and cause of death not directly attributable to HIV in 41% [2]. Therefore in the era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) patients with HIV infection live longer and experience increased mortality from causes not directly attributable to HIV. Recent data suggest that Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary disease (COPD) is becoming increasingly common in HIV-infected patients on antiretrovirals [3]. However even studies conducted before the introduction of HAART suggested that HIV infected patients have increased susceptibility to COPD. Diaz et al reported that the prevalence of emphysema in 114 HIV infected patients was 15% compared to only 2% in 44 HIV nega- tive patients [4]. Poirier et al reported that the prevalence of airway hyperresponsiveness was 30.1% in 151 HIV positive smokers compared to 13.3% in 82 HIV negative smokers [5]. As bronchial hyperresponsiveness can be a potential risk factor for progressive COPD in smokers, the data by Poirier et al may indicate a potential link between smoking and HIV infection that could acceler- ate the development of COPD [6]. The fact that 40-70% of HIV positive subjects smoke in the era of HAART should probably also be considered [7]. The rate of in- fectious pulmonary complications has been reduced withthe new antiretrovirals [8]. However, Morris et al  E. Giantsou et al. / Health 3 (2011) 218-227 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 219219 suggested that, colonization with Pneumocystis jirovecii can predict lower FEV1 and FEV1/FVC, as well as clinical airway obstruction without having necessarily clinical evidence for chest infection [9]. These investi- gators reported that the presence of Pneumocystis in the lungs even at low levels in clinically healthy HIV posi- tive subjects can produce inflammatory changes similar to those seen in COPD independant of smoking. This observation lend support to the hypothesis that Pneumo- cystis can be involved in the progression of airway ob- struction in HIV infected [10]. Recent reports suggested that HIVinfection may be an independant risk factor for COPD [11,12]. The prevalence of COPD in HIV infected subjects has important clinical and policy implications for future de- livery of care. Although previously assessed it has yet to be summarized in a systematic review. The purpose of this review is to systematically retrieve and appraise the available data on the prevalence of COPD in patients with HIV-infection. 2. METHODS 2.1. Search Strategy The review followed the methodology of systematic re- views [13,14,15]. Two researchers independently searched the literature by using the Ovid search platform of CI- NAHL (1981 to October 2010), EMBASE (1980 to Oc- tober 2010), Medline (1950 to October 2010) and Psy- chINFO (1967 to January 2010) databases. The follow- ing search terms were identified through the Medical Subject Headings dictionary [16]: HIV, COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, Chronic Airflow Obstruction, Chronic ir- reversible airflow obstruction, Chronic Bronchitis, Em- physema. All different possible combinations of terms were used in the literature searches to maximize refer- ences retrieved. The library of the Cochrane reviews was consulted to verify whether a given review has already been made [17]. A hand search was also performed of reference lists of the relevant review articles and of the articles identified at the electronic search regardless of the initial publication language. Annals of relevant con- gresses were reviewed searching for presented but not published studies. 2.2. Eligibilty Criteria Potentially relevant studies were identified by title, then by abstract, then by full text. Studies were selected for review if they met the three following inclusion criteria: 1) Adults (> 16 years old) 2) HIV infection as defined by the World Health Or- ganization [18] and 3) COPD documented in patients diagnosed with HIV-infection. All retrieved reports were checked for inclusion crite- ria in a blinded fashion by two authors. In the case of duplicate publication the largest study, if applicable was included. Any disagreement between the investigators was solved independently by a third experienced reviewer. 2.3. Exclusion Criteria Studies were excluded first by title, then by abstract and finally by full text if they were: 1) Case reports. Studies with small samples have a greater chance of publication bias [19] 2) Narrative pieces without data to support observa- tions (editorials, policy recommendations, opinion surveys and commentaries) 3) Enrolling patients with HIV exclusively from hos- pital inpatient wards. The rate of COPD in hospital inpatients may be biased upwards compared to pa- tients at a similar stage of disease who were not hospitalized. Hospital inpatients may have faster rates at which they develop Acquired Immune De- ficiency Syndrome and therefore susceptibility to comorbidities, including COPD [20]. 4) Using International Codes for Disease classifica- tion (ICD-9 codes) to diagnose COPD without provision to improve the accuracy of this source of data by including inpatient codes at least once and outpatient codes at least twice [21]. 2.4. Description of Methods to Diagnose COPD Criteria of COPD diagnosis are as following: 1) British Thoracic Society: FEV 1 /FVC < 0.70 and if FEV 1 > 80% of predicted, presence of symp- toms like cough and dyspnea [22]. 2) European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.70 [23,24]. 3) Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease: post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.70 [25]. For the use of ICD-9 codes to diagnose COPD the relevant guideline suggests that the code is to be used when the medical record documentation substantiates obstructive lung disease including among other tests spirometry according the ATS protocol [26]. 2.5. Data Extraction, Synthesis and Analysis For each eligible study data were extracted on number of patients included, gender, age, race or ethnicity of  E. Giantsou et al. / Health 3 (2011) 218-227 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 220 participants, intravenous drug abuse, men who have sex with men, smoking status, history of Pneumocystis carinii or bacterial pneumonia, source of recruitment, CD4 and HIV viral load levels, treatment with HAART, study de- sign and key exclusion criteria, study quality and inclu- sion criteria, method use to diagnose COPD and respira- tory symptoms. Outcome assessed was the prevalence of COPD. Data extraction was performed by one author and cross-checked against extraction by another reviewer. Due to qualitative and quantitative heterogeneity in patients diagnosed with HIV infection a quantitative synthesis was not possible. A descriptive and qualitative analysis was therefore undertaken. The quality of eligible studies was assessed on the ba- sis of the following features [27]: 1) consecutive patients were enrolled 2) the recruitment period was defined 3) the follow-up period was defined 4) subjects lost to follow-up were described 5) subjects known to be alive but lost to follow-up were < 10% 6) respiratory symptoms were assessed with a stan- dardized questionnaire 7) the method to assess clinical data was clearly de- scribed (interview and standardized medical records versus survey and standardized medical records) 8) management of subjects with missing data was described 9) Antiretroviral treatment was described as standard, at least three antiretroviral agents from at least two different classes of medications, or otherwise, if applicable. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Search Results and Study Characteristics The flow chart of the search results is presented in Figure 1. The search identified 911 citations from which Figure 1. Flow chart of literature search results.  E. Giantsou et al. / Health 3 (2011) 218-227 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 221221 836 abstracts and 75 full-text publications were retrieved. A total of 8 non-interventional studies conducted in USA during the period 2005-2010 were eligible for review. The characteristics of the patients included in the studies assessing the prevalence of COPD in HIV infected pa- tients are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Three studies evaluated veterans outpatients [12,28,29], four evaluated outpatients of HIV or Sexually Transmitted Disease clinics [9,30-32], one evaluated intravenous drug users recruited from the community [33]. Five studies were prospective observational in design and three cross sec- tional surveys. The mean age of patients ranged from 43 to 50.3 yrs. The age range was 32 to 70yrs, but in four out of eight studies it was 39-55 yrs. Men were more than 60% of the population in all but one study. African Americans were less than 50% of the population in all but two studies. Illicit drug use was reported in up to 25% of the population in all but two studies. Men who have sex with men ranged from 38% to 49.7%. The prevalence of active smoking ranged from 37.1% to 83.3% and in four out of eight studies it was above 50%. History of previous Pneumocystis or bacterial pneumo- nia ranged from 1.3% to 44.3% although in six out of eight studies ranged from 5% to 15.5%. The mean CD4 varied from 264 cells.mm3 to 484 cells.mm3. The mean HIV viral load was from 2.6 to 6.5 copies per ml. In five out of eight studies more than 60% of the population was on HAART although the proportion of patients on HAART ranged from 28% to 83.3%. In three of the five prospective observational studies the period of time from diagnosis of HIV infection to diagnossis of COPD was reported and it was 10. 33 yrs (mean) with range from 9 to 13yrs [30-32]. The design and exclusion criteria for the studies as- sessing the prevalence of COPD in HIV infected patients are presented in Table 3. Three studies excluded sub- jects with cough, shortness of breath or fever in the last month before study enrolment [9,31,32]. All studies provided data on smoking and illicit drug use for every subject included. This was so because four studies ex- cluded subjects with missing data on smoking or illicit drug use and the other four had no subjects with missing Table 1. Characteristics of the studies assessing the prevalence of COPD in adults with HIV. First author year HIV + N, Men % Mean age (yrs) (range or SD) African Americans %IDU %MSM %Current Smokers % Ever Smokers % History of PCP and Bacterial pneumonia Recruited from Crothers-2005 (28) 881 34 50.3 (33-65) 18,45 9.9 38 63.3 NA 8.1 Veterans outpatients Crothers-2006 (12) 1014 100 50 (43-55) 58 31 NA 46 NA 10.9 Veterans outpatients Morris-2009 (9) 42 87 46.5 (32-69) 48.25 NA NA 42.1 97 15.5 Outpatients HIV clinic George-2009 (32) 234 82 44.1 (26-70) 28.2 12 48 37.1 75 43.2 Outpatients HIV clinic Gui-2010 (30) 119 79 43 (8.3) 19 25 NA 52 85 39 Outpatients HIV clinic *Crothers-2010 (29) 33420 98 45 (39-51) 43 23 NA NA 80 12.8 Veterans medical outpatients Drummond-2010 (33) 288 63.1 48.2 (43-53) 96.7 55.4 40 83.3 76.1 1.3 Commu nity HIV and IDU Gingo-2010 (31) 167 73.6 46 (20-70) 49.7 18.6 49.7 52.7 59.7 44.3 STD outpatie nts clinic Abbreviations: COPD; Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV; Human immunodeficiency virus, MSM; Men who have sex with men, PCP; Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, STD; Sexually transmitted diseases, IDU; Intravenous drug users. *Data for this study are presented as they available so far on www. vaco- hort.org, accessed 07/11/2010  E. Giantsou et al. / Health 3 (2011) 218-227 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 222 Table 2. Assessment of the characteristics of HIV infection in the reports evaluating the prevalence of COPD in adults with HIV infection. First authoryear (Reference) First author (year) Mean CD4 cells.mm3 (range or SD) Mean Log10 HIV-RNA viral load copies/ml (range or SD) at diagnosis of COPD On HAART % Crothers-2005 (28) Crothers (2005) 345 (2 - 1880) 2.6 (1.6 - 5.9) 28 Crothers-2006 (12) Crothers (2006) 322 (225 - 544) 3.15 (1.7 - 4.4) 31.3 Morris-2009 (9) Morris (2009) 456 (4 - 1059) 3.9 (0.50 - 22.2) 78.6 George-2009 (32) George (2009) 371 (3 - 1368) 6.5 (2.8) 83.3 Gui-2010 (30) Cui (2010) 484 (274) 3.38 (1.26) 84 Crothers-2010 (29) Crothers 2010 264 (108 - 451) 4.1 (3 - 4.93) 65 Drummond-2010 (33) Drummond (2010) 314 (177 - 503) 3.99 (0.5 - 26.7) 53.8 Gingo-2010 (31) Gingo (2010) 479 (22 - 1390) 3.89 (3.89 - 14.3) 80.7 Abbreviations: HIV; Human Immunodeficiency Virus, COPD; Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, HAART; Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Table 3. Design and key exclusion criteria for studies assessing the prevalence of COPD in adults with HIV-infection. First author-year (Reference) Type of study-name Females were excluded Subjects with cough, SOB* or fever in the Last month were excluded Subjects with Missing data on smoking, illegal drug use were excluded Subjects without CD4 or HIV RNA levels were excluded or Comparisons with and without subjects with missing data found no significant differences Subjects reporting antiretroviral other than standard* were excluded Crothers-2005 (28) Prospective observational- VA C S - 3 – – √ √ – Crothers-2006 (12) Prospective observational- VA C S - 5 √ – √ √ – Morris-2009 (9) Prospective observational – √ NA NA NA George-2009 (32) Cross sectional survey – √ NA √ √ Gui-2010 (30) Cross sectional survey – – NA NA NA Crothers-2010 (29) Prospective observational- VACS-VC – – √ NA – Drummond-2010 (33) Prospective observational- ALIVE – – √ NA – Gingo-2010 (31) Cross sectional survey – √ NA √ NA Abbreviations: COPD; Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV; Human immunodeficiency virus infection, SOB; Shortness of breath, NA; Non-ap- plicable, as there are no missing data *At least three antiretroviral agents from at least two classes of medications.  E. Giantsou et al. / Health 3 (2011) 218-227 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 223223 data on smoking or illicit drugs. Similarly all studies provided CD4 level and HIV viral load for every subject included at the time of COPD diagnosis. This was so because four studies excluded subjects without CD4 or HIV viral load and the other four had no subjects with missing data. In three studies the subjects were on stan- dard antiretroviral therapy and one study excluded sub- jects with other than standard antiretroviral therapy. 3.2. Quality Assessment The quality assessment of the studies assessing the prevalence of COPD in HIV infected subjects is pre- sented in Table 4. All studies enrolled consecutive pa- tients. The recruitment period was described in all but two studies [9,30]. The follow-up period was defined in four out of five prospective observational cohorts and it was not applicable for the three cross sectional surveys. Subjects lost to follow-up were fully described in four studies whereas three more studies had no subjects lost to follow-up. Of the four studies who had subjects lost to follow-up but known to be alive at the time of the study three confirmed that these subjects represented less than 10% of the population [11,12,29]. Respiratory symptoms were assessed by a standardized respiratory questionnaire in all but one study [9]. Data were obtained by interview and standardized medical records in four out of eight studies and by survey and standardized medical records in the other four studies. 3.3. Assessment of Prevalence of COPD The method used to diagnose COPD and the relevant prevalence is presented in Table 5. In three studies COPD was diagnosed with post-bronchodilator FEV1/ FVC < 0.7, in three studies with ICD-9 codes, in one study with FEV1/FVC below the 5% lower limit of age adjusted normal and in one study with pre-bronchodila- tor FEV1/FVC < 0.7. The prevalence of COPD ranged from 4% to 35%. The highest COPD prevalence of 35% corresponded to clinically free from chest infection HIV positive patients colonized with Pneumocystis [9]. In the same study the prevalence of COPD for HIV positive who were not colonized with Pneumocystis was less than 6%. In the study with the lowest recorded prevalence of 4%, obstructive lung function was diagnosed by pre- bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 in 12%, but only 38% of them underwent post-bronchodilator spirometry [30]. In the same study logistic regression was used to dem- onstrate that COPD was associated with increased odds (OR = 2.25 CI: 1.43 to 3.54) of reporting MRC dyspnea scale > 3 and that HIV was also associated with in- creased odds (OR = 1.50 CI: 1.08-2.09) of reporting MRC dyspnea scale > 2 [30]. Another four studies reported prevalence between 10% and 16% [12,28,29,33]. One of the studies using ICD-9 codes, reported prevalence of COPD of 15% when patients were self reported to be examined for COPD and 10% when ICD-9 codes were used [12]. The respiratory symptoms in the 8 studies Table 4. Assessment of quality of studies reporting the prevalence of COPD in adults with HIV-infection First author-year (Reference) Consecutive patients were enrolled Recruitment period was Follow-up period was defined Subjects lost to follow-up were described Subjects known to be alive but lost to follow-up < 10% Respiratory symptoms assessed with a standardized questionnaire Collection of data: interview and standardized Collection of data: survey and standardized medical records Crothers-2005 (28) √ √ √ √ √ √ NA √ Crothers-2006 (12) √ √ √ √ √ √ NA √ Morris-2009 (9) √ – – – – – √ NA George-2009 (32) √ √ NA NA NA √ √ NA Gui-2010 (30) √ – NA NA NA √ NA √ Crothers-2010 (29) √ √ √ √ √ √ NA √ Drummond-2010 (33) √ √ √ √ – √ √ NA Gingo-2010 (31) √ √ NA NA NA √ √ NA Abbreviations: COPD; Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV; human immunodeficiency virus, NA; non applicable.  E. Giantsou et al. / Health 3 (2011) 218-227 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 224 Table 5. Assessment of respiratory symptoms, method to evaluate the prevalence and prevalence of COPD in adults with HIV- infection. First author-year (Reference) Respiratory symptoms among subjects included in the study % Method to determine the prevalence of COPD Prevalence of COPD among all subjects included in the study % Crothers-2005 (28) 35 ICD-9 codes 10.36 Crothers-2006 (12) NA Patient self report ICD-9 1510 Morris-2009 (9) 21 Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 35 George-2009 (32) 31 FEV1/FVC below the 5% lower limit of normal adjusted for age 8.6 Gui-2010 (30) 42.8 Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 4 Crothers-2010 (29) – ICD-9 codes 16 Drummond-2010 (33) 48.5 Pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 15.6 Gingo-2010 (31) 63.5 Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 21 Abbreviations: COPD; Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV; Human immunodeficiency virus. included in this review ranged from 31% to 63%. In the three studies which excluded patients with cough, short- ness of breath or fever in the last month before enrol- ment the respiratory symptoms ranged from 21% to 63%. In three of the eight studies the respiratory symptoms rate was > 40% [30-33]. Three studies compared the prevalence of COPD be- tween HIV positive and HIV negative patients with simi- lar characteristics [12,29,33]. Two of them adjusted for known risk factors of COPD and found that HIV posi- tive compared to HIV negative subjects were 50% more likely to get diagnosed with COPD by ICD-9 codes (OR = 1.47 with CI: 1.01 to 2.13) and 60% more likely to have a diagnosis of COPD by self report (OR = 1.58, CI: 1.14 to 2.19). The third study found prevalence of COPD of 15.7% in HIV positive and of 15.5% in HIV negative subjects [ 33 ]. In that study the population was com- posed entirely of intravenous drug users and intravenous drug use is a well known risk factor for COPD [34]. The same authors demonstrated that in HIV patients, in whom the mental health summary score is already ad- versely affected by HIV, the presence of COPD is asso- ciated with 2.43 unit further decrease in the mental health summary score, which can be translated to an increase in the likelihood of death by approximately 8% [33]. 4. Discussion With the efficacy of HAART, life expectancy of HIV infected individuals has extended such that they are be- coming increasingly susceptible to chronic debilitating diseases like COPD. HIV positive subjects have reported rates of respiratory symptoms comparable to those ob- served in elderly smokers, they are diagnosed with COPD at younger age and smoke more than the general popula- tion. HIV and COPD have been reported to exert addi- tive effects on dyspnea and reduction of quality of life. Although no definite conclusion about the prevalence of COPD in HIV can be drawn from the data available, as the reported prevalence varies considerably, it is evident that as HIV patients become an aging population, health care providers should consider COPD when evaluating HIV infected patients, especially those who present with respiratory symptoms or impairment. There are comparability issues that should be consid- ered in the interpretation of our findings. To determine the prevalence of COPD in HIV infected patients require vigorous longitudinal studies. However the studies available consisted of 5 prospective cohorts and 3 cross sectional studies. Most research has been conducted in North American tertiary care University centers in the period 2009-2010. Therefore the recorded prevalence may not reflect the situation in other continents or an- other level of care. The majority of patients included were male smokers that prevent us from drawing con- clusions about the prevalence of COPD in HIV positive females who have been reported to have high smoking rates [34]. However although predominantly male the cohorts included in our study were ethnically diverse. The case mix varied between the studies since three of them studied veterans, two studied intravenous drug users and three outpatients with HIV. Although, the de-  E. Giantsou et al. / Health 3 (2011) 218-227 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 225225 mographics of the studies included in this review were those of patients at risk for HIV and COPD, it could be argued that our results may not necessarily reflect other populations. However, the Veterans Health Care System is the largest provider of healthcare to HIV infected in USA and demographics similar to those included in our review have been described in other studies of HIV- infected non-veterans [35]. The method to diagnose HIV was ICD-9 codes in three of the eight studies and spi- rometry in the rest. It has been previously reported that ICD-9 are more likely to underestimate than overesti- mate the prevalence of chronic conditions and the au- thors addressed this potential limitation by using a sec- ond method to measure prevalence, the patient self- re- port [12,36-38]. The consistency of the measured preva- lence with these two methods strengthens the validity of their results on prevalence with ICD-9 codes. Additional strength to their findings is added by the fact that the authors assessed the prevalence of COPD in HIV in- fected compared to demographically matched HIV- un- infected controls and found it to be 50% to 60% more common. However, spirometry remains the gold stan- dard for the diagnosis of COPD. The previously reported effect of the use of pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 compared to post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 on the estimated prevalence of COPD should also probably be considered [39]. The question whether HIV infected is at sufficient risk to benefit from screening for COPD remains unanswered from the available data. However the studies included in this review have highlighted potential mechanisms who may explain, at least in part, the pathogenesis of COPD in HIV. Multiple interacting factors have been described. HIV infected individuals demonstrate elevated systemic and topical inflammatory cytokines, including those in- volved in the pathogenesis of COPD [40-42]. Episodes of clinical pneumonia and colonization with respiratory organism may contribute to airway obstruction in sub- jects with HIV infection [43,44]. Colonization with Pneumocystis jirovecii, the organism that is associated with human Pneumocystis Carinii pneumonia, has been associated with the presence and severity of COPD in HIV negative subjects [9]. Pneumocystis jirovecii has been identified in the sputum of HIV positive smokers compared to non-smokers in the absence of active PCP [9]. HIV has been suggested to accelerate premature frailty and aging related changes in the immune system [45-48]. As a result HIV may render the lung more sus- ceptible to diseases such as COPD, which has also been suggested as a disease of accelerated lung aging [49,50]. Smoking, a habit highly prevalent in HIV population, exacerbates cellular senescence [51]. We cannot but ob- serve that from the suggested potential links between HIV and COPD, smoking and infection-colonization may be susceptible to interventions. Considering that there are approximately 31.3 million adults who live with HIV today and 2.3 million newly infected every year, who are in their majority smokers with mean age at death 60yrs, the relevant research should probably be considered as money well spent [52]. In this systematic review we found that, although defi- nite conclusion about the prevalence of COPD in HIV cannot be drawn from the data available so far, COPD is becoming increasingly common among HIV infected, as they now smoke and live longer due to highly effective antiretrovirals. We clearly need more longitudinal stud- ies to assess the prevalence of COPD in HIV infected and the potential links between the two. In the meantime healthcare providers should be vigilant to screen for un- diagnosed COPD and hesitant to attribute respiratory symptoms solely to HIV infection. REFERENCES [1] Palella, F.J., Delaney, K.M., Moorman, A.C., Loveless, M.O., Fuhrer, J., Satten, G.A., Aschman D.J. and Hol- berg, S.D. (1998) Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. NEJM, 338, 853-860. |doi:10.1056/NEJM199803263381301 [2] Braithwaite, R.S., Justice, A.C., Chang, C.C., Fusco, J.S., Raffanti, S.R., Wong, J.B. and Roberts, M.S. (2005) Es- timating the proportion of patients infected with HIV who will die of comorbid diseases. American Journal of Medicine, 118, 890-898. [3] Beck, J.M., Rosen, M.J. and Peavy, H.H. (2001) Pulmo- nary complications of HIV infection. Report of the Fourth NHLBI Workshop. American Journal of Respi- ratory and Critical Care Medicine, 164, 2120-2126. [4] Diaz, P.T., King, M.A., Pacht, E.R., Wewerrs, M.D., Gadek, J.E., Nagaraja, H.N., Drake, J. and Clanton T.L. (2000) Increased susceptibility to pulmonary emphysema among HIV seropositive smokers. Annals of Internal Medicine, 132, 369-372. [5] Poirier, C.D., Inhaber, N., Lalonde, R.G and Ernst, P. (2001) Prevalence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness among HIV infected men. American Journal of Respira- tory and Critical Care Medicine, 164, 542-545. [6] Tashkin, D.P., Altose, M.D., Connett, J.E., Kanner, R.E., Lee, W.W. and Wise, R.A. (1996) Metacholine reactivity predicts changes in lung function over time in smokers with early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The Lung Health Study Research Group. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 153, 1802- 1811. [7] Health Canada. (1999-2007) Canadian tobacco use monitor survey. Internet available: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca-ps/tobac-tabc/research-recherche/ stat/indexeng.php [8] Laurence, J. (2005) HIV and the lung in the HAART era. AIDS Read, 15, 327-330.  E. Giantsou et al. / Health 3 (2011) 218-227 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 226 [9] Morris, A., Alexander, T., Radhi, S., Lucht, L., Sciurba, F.C., Kolls, J.K., Srivastana, R., Steele, C. and Norris, K.A. (2009) Airway obstruction in increased in Pneu- mocystis colonized Human Immunodeficiency Virus in- fected outpatients. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 47, 3773-3776. doi:10.1128/JCM.01712-09 [10] Morris, A., Sciurba, F.C. and Norris, K.A. (2008) Pneu- mocystis: A novel pathogen in chronicobstructive pul- monary disease? Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Dis- ease, 5, 43-51. doi:10.1080/15412550701817656 [11] Crothers, K. (2007) Chronic obstructive pulmonary dis- ease in patients who have HIV infection. Clinics in Chest Medicine, 28, 575-587. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2007.06.004 [12] Crothers, K., Butt, A.A., Gibert, C.L., Rodriguez -Barradas, M.C., Crystal, S. and Justice, A.C. (2006) In- creased COPD among HIV positive compared to HIV negative veterans. Chest, 130, 1326-1333. doi:10.1378/chest.130.5.1326 [13] Juni, P., Altman, D.G. and Egger, M. (2001) Systematic reviews in health care. Assessing the quality of con- trolled clinical trials. British Medical Journal, 323, 224-228. [14] Stroup, D.F., Berlin, J.A., Morton, S.C., Olkin, I., Wil- liamson, D.G., Rennie, D., Moher, D., Becker, D.G., Sipe, T.A. and Thacker, S.B. (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology. A proposal for reporting. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283, 2008-2012. doi:10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [15] De Sousa, M.R. and Ribeiro, A.L.P. (2009) Systematic reviews and meta-analysis of diagnostic and prognostic studies a tutorial. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia, 92, 229-238. [16] United States National Library of Medicine. (2010) Medical subjects headings. Internet available: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/ [17] Library of the Cochrane reviews. (2010) Internet avail- able: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/index.html [18] World Health Organization. (2010) WHO and HIV/AIDS. Internet available: http://who.int/library/collections/en/ [19] Moayyedi, P. (2004) Meta-analysis: Can we mix apples and oranges? American Journal of Roentgenology, 99, 2297-2301. [20] Low, N. and Egger, M. (1998) Can we predict the prog- nosis of HIV infection? How to use the findings of a prospective study. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 74, 149-154. doi:10.1136/sti.74.2.149 [21] McGinnis, K.A., Fine, M.J., Sharma, R.K., Skanderson, M., Wagner, J.H., Rodriguez-Barradas, M.C., Rabeneck, L. and Justice, A.C. (2003) Understanding racial dispari- ties in HIV using data from the veterans aging cohort-3 study and VA administrative data. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1728-1733. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.10.1728 [22] British Thoracic Society. (2004) COPD guidelines. Internet available: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13029/49425/494 25.pdf [23] Celi, B.R., McNee, B.R. and ATS/ERS Task force. (2004) Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD. A sumary of the ATS-ERS position paper. Euro- pean Respiratory Journal, 23, 932-946. doi:10.1183/09031936.04.00014304 [24] American Thoracic Society. (2004) COPD guidelines. Internet available: http://www.thoracic.org/clinical/copd-guidelines/resourc es/copddoc.pdf [25] National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute and World Health Organization Global Initiative for Chronic Ob- structive Lung Disease (GOLD). (2009) Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Internet available: http://www.goldcopd.com/ [26] AHIMA. (2010) ICD-9-CM coding guidance for LTC facilities. Appendix B: Reporting and sequencing diag- noses on the health record and UB-04 claim form. Jour- nal of AHIMA 81, 66-70. [27] Bossuyt, P.M., Reitsma, J.B., Bruns, D.E., Gatsonis, C.A., Glasziou, P.P., Irwig, L.M., Moher, D., Rennie, D., de Vet, H.C. and Lijmer, J.G. (2003) The STARD state- ment for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: Ex- planation and elaboration. Clinical Chemistry, 49, 7-18 doi:10.1373/49.1.7 [28] Crothers, K., Griffith, T.A., McGinnis, K.A., Rodri- guez-Barradas, M.C., Leaf, D.A, Weissman, S., Gilbert, C.L., Butt, A.A. and Justice, A.C. (2005) The impact of cigarette smoking on mortality, quality of life and co- morbid illness among HIV-positive veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 1142-1145. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0255.x [29] Crothers, K., Huang, L., Goulet, J.L., Goetz, M.B., Brown, S., Rodriguez-Barradas, M., Oursler, K.K., Rim- land, D., Gibert, C.L., Butt, A.A. and Justice, A.C. (2010) HIV infection and risk for incident pulmonary diseases in the combination antiretroviral therapy era. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. [30] Cui, Q., Mclvor, A., Smail, F., Thabane, L. and Smieza, M. (2010) Effect of smoking on lung function, respira- tory symptoms and respiratory diseases amongst HIV -positive subjects: A cross sectional study. Aids Research and Therapy, 7, 1-10. [31] Gingo, M.R., George, M.P., Kessinger, C.J., Lucht, L., Rissler, B., Weinman, R., Slivka, W.A., McMahon, D.K., Wenzel, S.E., Sciurba, F.C. and Morris, A. (2010) Pul- monary function abnormalities in HV-infected patients during the current antiretroviral therapy era. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 182, 790-796. doi:10.1164/rccm.200912-1858OC [32] George, M.P., Kannass, M., Huang, L., Sciurba, F.C. and Morris, A.B. (2009) Respiratory symptoms and airway obstruction in HIV-infected subjects in the HAART era. Public Library of Science, 4, 1-7. [33] Drummond, M.B., Kirk, G.D., Ricketts, E.P., McCor- mack, M.C., Haque, J.C., McDyer, J.F., Mehta, S.H., Engels, E.A., Wise, R.A. and Merlo, C.A. (2010) Cross sectional analysis of respiratory symptoms in an injection drug user cohort: The impact of obstructive lung disease and HIV. BMC Pulmonary Medicine, 10. [34] Burns, D., Hillman, D., Neaton, J.D., Sherer, R., Mitchell, T., Capps, L., Vallier, W.G., Thurnherr, M.D. and Gordin, F.M. (1996) Cigarette smoking, bacterial pneu- monia and other clinical outcomes in HIV-1 infection. Terry Beirn Community programs for clinical research in AIDS. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syn-  E. Giantsou et al. / Health 3 (2011) 218-227 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 227227 dromes and Human Retrovirology, 13, 374-383. doi:10.1097/00042560-199612010-00012 [35] Niaura, R., Shadel, D.G., Morrow, K., Tashima, K., Flanigan, T. and Abrams, D.B. (2000) Human immuno- deficiency virus infection, AIDS, and smoking cessation: The time is now. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 31, 808-812. [36] Justice, A.C., Lasky, E., McGinnis, K.A., Skanderson, M., Conigliaro, J., Fultz, S.L., Crothers, K., Rabeneck, L., Rodriguez-Barradas, M., Weissman, S.B. and Bryant. K. (2006) Medical disease and alcohol use among veterans with human immunodeficiency virus infection: A com- parison of disease measurement strategies. Medical Care, 44, 52-60. [37] Quan, H., Parsons, G.A. and Ghali, W.A. (2002) Validity of information on comorbidity derived from ICD-9-CCM administrative data. Medic,” Medical Care , 40, 675-685. doi:10.1097/00005650-200208000-00007 [38] Wilchesky, M., Tamblyn, R.M. and Huang, A. (2004) Validation of diagnostic codes within medical services claims. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57, 131-141. [39] Lindberg, A., Johnsson, A.C., Ronmark, E., Lundgren, R., Larsson, L.G. and Lunback, B. (2005) Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to BTS, ERS, GOLD and ATS criteria in relation to doctor’s di- agnosis, symptoms, age, gender, and smoking habits. Respiration, 72, 471-479. [40] Matsumoto, T., Mike, T., Nelson, R.P., Trudeau, W.L., Lockey, R.F. and Yodoi, J. (1993) Elevated serum levels of IL-8 in patients with HIV-infection. Clinical & Ex- perimental Immunology, 93, 149-151. [41] Lahdevirta, J., Maury, C.P., Teppo, A.M. and Repo, H. (1988) Elevated levels of circulating cachectin/tumor ne- crosis factor in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. American Journal of Medicine, 85, 289-291. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(88)90576-1 [42] Kaner, R.J., Santiago, F. and Crystal, R.G. (2009) Up -regulation of alveolar matrix metalloproteinases in HIV1+ smokers with early emphysema. Leucoc Biology, 86, 913-922. [43] Morris, A., Huang, L., Bacchetti P, P., Turner, J., Hope- well, P.C., Wallace, J.M., Kvale, P.A., Rosen, M.J., Glassroth, J., Reichman, L.B. and Stansell, J.D. (2000) Permanent decline in pulmonary function following pneumonia in Human Immunodeficiency virus infected persons. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 162, 612-616. [44] Morris, A., Sciurba, F.C., Lebedeva, I.P., Githaiga, A., Elliot, M., Hoqq, J.C., Huang, L. and Norris, K.A. (2004) Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity and Pneumocystis colonization” American Jour- nal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 170, 408-413. doi:10.1164/rccm.200401-094OC [45] Desquilbet, L., Jacobson, L.P., Fried, L.P., Phair, J.P., Jamieson, B.D., Holloway, M. and Margolick, J.B. (2007) HIV-1 infection is associated with an earlier occurrence of a phenotype related to frailty. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 62, 1279-1286. [46] Cao, W., Jamieson, B.D., Hultin, L.E., Hultin, P.M., Effros, R.B. and Detels, R. (2009) Premature aging of T cells is associated with faster HIV-1 disease progression. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 50, 137-147. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181926c28 [47] Tenorio, A.R., Spritzler, J., Martinson, J., Gichinga, C.N., Pollard, R.B., Lederman, M.M., Kalayjian, R.C. and Landay, A.L. (2009) The effect of aging on T-regulatory cell frequency in HIV infection. Clinical Immunology, 130, 298-303. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2008.10.001 [48] Appay, V., Almeida, J.R., Sauce, D., Autran, B. and Papagno, L. (2007) Accelerated immune senescence and HIV-1 infection. Experimental Gerontology, 42, 432-437. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2006.12.003 [49] Ito, K. and Barnes, P.J. (2009) COPD as a disease of accelerated lung aging. Chest, 42, 173-180. doi:10.1378/chest.08-1419 [50] MacNee, W. (2009) Accelerated lung aging: A novel pathogenic mechanism of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Biochemical Society Transactions, 37, 819-823. doi:10.1042/BST0370819 [51] Nyunoya, T., Monick, M.M., Klingelhutz, A.T., Yarovin- sky, A.O., Cagley, J.R. and Hunninghake, G.W. (2006) Cigarette smoke induces cellular senescence. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology, 35, 681-688. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2006-0169OC [52] World Health Organization. Global epidemic data and statistics. A global view of HIV in 2008. Internet avail- able: http://www.who.int/hiv/data/global_data-slideshow. html. |