Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

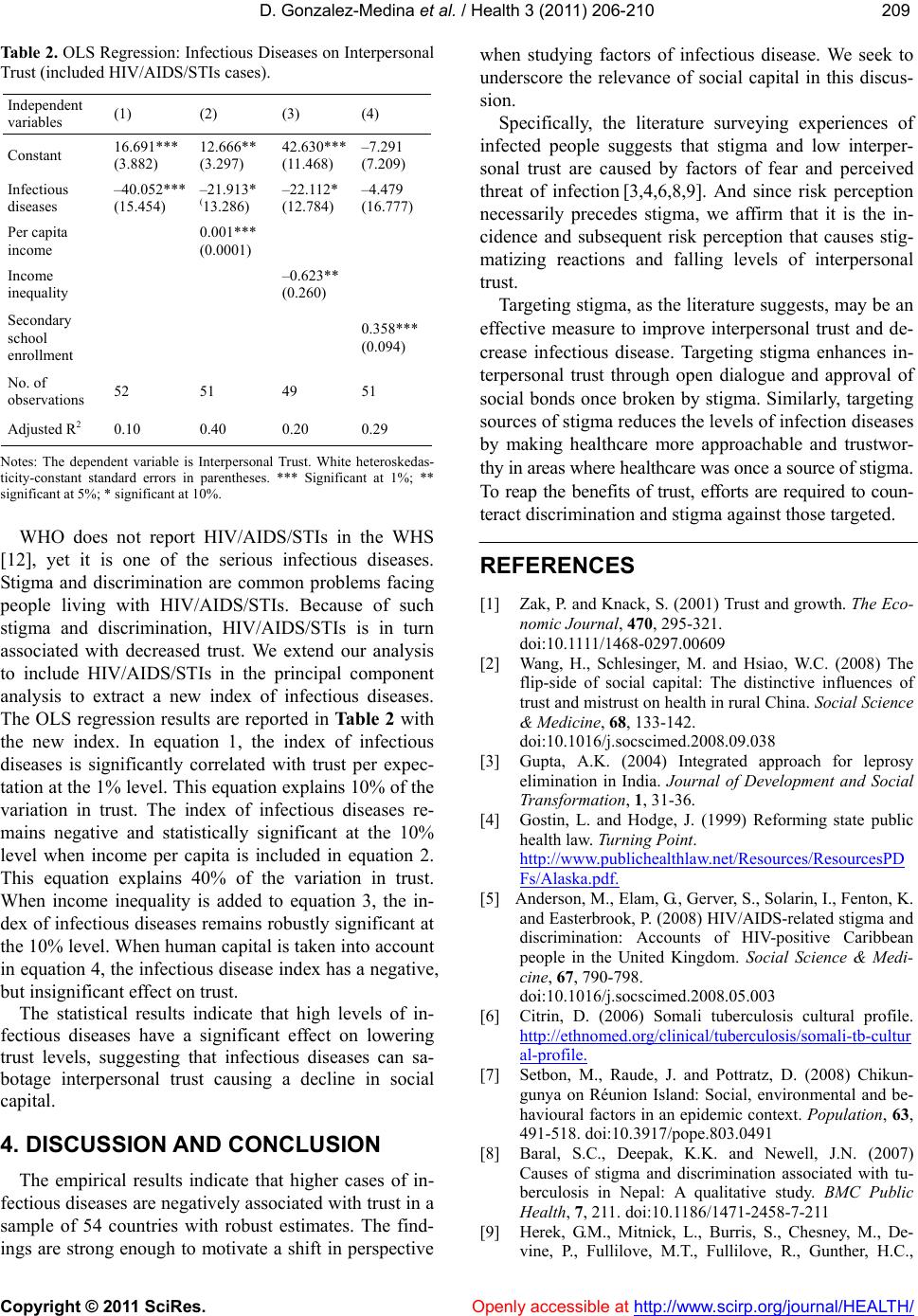

Vol.3, No.4, 206-210 (2011) Health doi:10.4236/health.2011.34037 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Infectious diseases and interpersonal trust: international evidence Diego Gonzalez-Medina1, Quan V. Le2* Seattle University, 901 12th Avenue, Seattle, USA; *Corresponding Author: lequ@seattleu.edu Received 18 January 2011; revised 23 March 2011; accepted 27 March 2011. ABSTRACT The objective of this paper is to investigate the relationship between infectious disease and trust, hypothesizing a negative relationship. In- terpersonal trust is defined as the aggregate response that fellow citizens are trustworthy. We explore stigma as a channel in the relation- ship. We apply cross-country regression analy- sis on a sample of 54 countries. We test our hypothesis using data on selected infectious diseases from the World Health Statistic s ( WHS) published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and data on trust from the World Values Surveys (WVS). We cre ate an index of infectious disease using factor analysis. The OLS regres- sion equation includes control variables of in- come inequality, per capita income and human capital. The empirical results are considerably robust showing that higher cases of infectious diseases are negatively associated with trust when controlling for macroeconomic and social variables. Keywords: Trust; Stigma; Social Capital; Infectious Disease; HIV/AIDS 1. INTRODUCTION The topic of trust is relatively new to the field of so- cial science and public health. Trust positively facilitates our social institutions, which rely considerably on col- laboration. In their seminal paper on trust and growth, Zak and Knack [1] explain trust as a driver for lowering transaction costs by reducing oversight costs with as- sumed aggregate effects. It can do this because trus t is a force behind social capital formation rewarding coordi- nation within social structures. Wang et al. [2] define trust as a form of cognitive social capital, meaning that it predisposes people to work in a mutually beneficial man- ner. Their research shows that there is strong and com- plex relationship between trust and health [2], which we seek to investigate further. In this paper we focus on this relationship in the context of in fectious disease. Previous literature has provided strong empirical evidence that social support promotes preventative action and treat- ment of infectious disease [2,3]. Our objective is to in- vestigate the correlation of infectious disease and aggre- gate trust levels, hypothesizing a negative relationship. Using a sample of 54 countries, we test our hypothesis using data on selected infectious diseases from the World Health Statistics (WHS) published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and data on trust from the World Values Surveys (WVS). In previous studies, relationships between trusting behavior and infectious disease were examined in the context of public health [2-7]. Though samples were limited to specific coun tries or diseases, stigma rose as a common theme. The interaction between infectious dis- ease, stigma and trust implies stigma as the main actor between the others. Stigma is created from “an attribute that is deeply dis- crediting” of the infected population, provoking mistrust or sympathy, fear or support [8]. Where interpersonal trust is a reward of social collaboration, stigma disrupts it by invoking widespread prejudice, discrimination and disregard against infected members of society and those associated with them [9]. Thus, the presence of stigma undermines trust on an individual level, with assumed aggregate effects1. Yet, stigma also leads infected people to conceal their disease and making it unlikely for them to seek testing, treatment and support [3]. Such inaction generally increases the load of infectious disease since effective treatment is not taken. Therefore, stigma has the power to both undermine aggregate trust and in- crease a country’s incidence of infectious disease. The research on the stigma surrounding tuberculosis 1We elevate the relationship between stigma and interpersonal trust up to aggregate trust levels because stigma, by definition, must be widely held. Otherwise, it is indistinguishable from individual prejudice.  D. Gonzalez-Medina et al. / Health 3 (2011) 206-210 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 207207 in Nepal and Somalia illustrates how a widespread dis- ease can sabotage interpersonal trust [6,8]. Since tuber- culosis is a curable disease, it b enefits highly from effec- tive social institutions. These would have the effect of expediting successful identification and treatment of tuberculosis. In one interview from the study, support is clearly lacking: “…they want that you also have TB…because they know that they will be isolated and they become very vindictive. They want everyone to have it…He will trick you…the person with TB will drink, spit inside and throw the rema ining back in the pot…” [6] Previous studies in Nepal, Réunion Island, and of Caribbean immigr ants in the Un ited Kingdo m found fear of contamination and presence of stigma [5,7,8]. One woman from the Caribbean expressed how it caused her to lose her job as a teacher: “You’ve got AIDS. I don’t want nobody to come and burn my school down, so it’s best if you leave.”[5] Left to its own devices, widespread mistrust and fear can introduce discrimination into the healthcare system. This has large implications for the spread of infectious diseases. For example, breaches of confidentiality and refusal to exam an infected patient leads to delays in treatment or complete evasion [5]. When social institu- tions like these become a source of discrimination, the infected are left on their own to find support [9]. Thus it is clear that stigma has the effect of both diminishing trust and raising levels of infectious disease. And given its dominance in previous studies, it is assumed to be the main actor behind the negative relationship between trust and infectious disease. In the following sections, we provide cross-national evidence displaying a negative relationship between in- fectious diseases and aggregate levels of interpersonal trust. Following the two-tier methodology of Zak and Fakhar [10], we use WVS data on interpersonal trust to capture generalized trust and test it against country level data of infectious diseases. We are, in essence, testing whe- ther trust (at a personal level) has a relationship with infectious disease that scales up to the country level. Ex- planatory variables of per capita income, income ine- quality and human capital are also taken into account. Specifically, we use secondary education enrollment as an adequate proxy for human capital, citing previous growth literature [11]. 2. DATA AND METHODS We attempt to provide testable implications of our hypothesis using relevant data on infectious diseases and interpersonal trus t in a cro ss-section of countries. We use second level data on selected infectious diseases from the World Health Statistics (WHS) published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2009 [12].2 There are 18 officially reported infectious diseases based pri- marily on the availability of data in 2007.3 This is the most comprehensive data available despite its limita- tion.4 The International Health Regulations reported some diseases, while countries and the WHO monitor other diseases in the context of specific control programs [12]. The database reveals that the Eastern Mediterra- nean region has the highest cases reported, while the region of the Americas has the lowest number of cases reported. The database also reports that lower middle income group has the highest number of cases reported, while the high income group has the lowest number of cases reported. Because the dataset includes a large number of infec- tious disease cases, examining them one-by-one does not provide sufficiently strong evidence to test the relation- ship between infectious diseases and interpersonal trust. It is more feasible to construct a statistical indicator us- ing data reduction method on the cases of infectious diseases. We construct an index of infectious diseases by employing factor analysis. Principal component analysis, the most common form of factor analysis, is used to ex- tract the first principal component based on the largest loading. The data on trust are obtained from the World Values Surveys (WVS) 1990-2000 [1,13-15]. The WVS con- tains data from thousands of respondents from both de- veloping and developed countries.5 The respondents in each country respond to the question using the native language, and the questions correspond to impressions of the respondents’ own countries: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” This question captures “interpersonal trust”, describing whether two randomly selected individuals trust each other. This general phrasing of trust captured in the WVS survey question suggests that this is a reasonable cross-country measure of trust. This trust variable has been used in a 2World Health Statistics (2009), Table 3: Selected Infectious Diseases, p p. 59-69. Geneva: WHO. The numbers are officially reported, but vary greatly in quantity, representatives, comparability and informa- tion value (WHS, p. 5 9 , 2009). 3H5N1 influenza cases were reported in 2008. WHS differentiates between zero cases reported and no information available for a country where possible. 4There is a limitation when using this dataset. WHO recognizes tha t there are inadequacies in the measurement of cases of infectious dis- eases [12]. The report states that it is difficult to understand the sever- ity of infection in a country solely by the recorded number of occur- rences. This inadequacy can be due to the nature of the disease itself or due to the nature of data collection [12]. In addition, the disease itsel f can be difficult to report (e.g. H5N1 influenza, Japanese encephalitis) without specific laboratory testing that is not always available [12]. Depending on the country, data collection can also be a significan t challenge. 5See the WVS’s website for further technical information about the questionnaire at: www.wordvaluessurvey.org.  D. Gonzalez-Medina et al. / Health 3 (2011) 206-210 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 208 cross-country contex t in several studies [1,10,13] despite its limitation. 6 Given the availability o f the data fro m the WVS, we are able to compare the levels of trust to cases of infectious diseases across countries in this study. The data vary noticeably between 54 rich and poor countries. In poor countries such as Uganda, Tanzania, and the Philippines, less than 10% of the respondents say their fellow citizens are trustworthy, more than 65% of the respondents in Sweden and Denmark believe this is so. If societies are at high risk of contracting deadly dis- eases from the afflicted individuals, stigma and dis- crimination can sabotage interpersonal trust. Thus, high scores on the infectious disease index are associated with lower trust levels. For instance, the trust levels in Swe- den and Denmark are remarkably high with low scores on the infectious disease index, whereas the trust levels in Uganda, Tanzania, and the Philippines are considera- bly low with high scores on the infectious disease index. We also utilize other explanatory variab les that have a strong effect on trust such as per capita income [13]. Per capita income is expected to take a positive sign. Other variables also included in the regression analysis are income inequality and the level of human capital. In- come inequality plays a role in discouragement of social cohesion amongst individuals causing class distrust through polarization [16]. Thus, societies with high in- come inequality exhibit lower trust. We used the Gini coefficient of income as a proxy for income inequality. The sign is expected to be negative. Human capital ef- fects trust in the way that it enhances social networks and presents rewards for integrity. These rewards given on the basis of meeting performance criteria with integ- rity establishes the fundamental social infrastructure for trust upon which an eco nomy can be built. We used per- centage of gross secondary school enrollment as a proxy for human capital. Secondary education provides not only the tools of reading, writing and mathematics, but also lays the foundations of on-going learning and de- velopment, allowing individuals to make constructive criticisms and rightful judgments. This leads us to expect human capital to take a positive sign. Data for per capita income, Gini coefficient, and gross secondary school enrollment are the taken from the World Development Indicators [17]. 3. RESULTS In this paper we hypothesize that societies with high levels of infectious diseases are more likely to respond, in aggregate, that their fellow citizens are less trustwor- thy. Table 1 reports OLS regressions of infectious dis- eases on trust controlling for other explanatory variables. In equation 1, the index of infectious diseases explains 10% of the variation in trust. The coefficient estimate for infectious diseases has a negative and significant effect, as hypothesized. In equation 2, the infectious disease index remains statistically significant with the expected sign when per capita income is included in the regression. By adding per capita income to the regression, the ex- planatory power increases to 34% of the variation in trust. Income inequality is added to equation 3 as a con- trol variable. The result shows that the index of infec- tious diseases has a negative and remains statistically significant per expectation. The coefficient on income inequality is negative and significant, suggesting dispar- ity in income decreases the levels of trust. This equ ation explains 20% of the variation in trust. Last but not least, when human capital is taken into account in equation 4, the infectious disease index has a negative, but insig- nificant effect on trust. However, per expectation, the coefficient on secondary education is positive and sig- nificant, suggesting that the skills attainted in secondary school are poised to develop critical thinking that are necessary for trust to triumph through truth.7 This equa- tion explains 29% of the variation in trust. Table 1. OLS Regression: Infectious Diseases on Interpersonal Trust (excluded HIV/AIDS/STIs cases) Independent variables (1) (2) (3) (4) Constant 12.278** (5.312) 10.832** (4.571) 39.099** (11.263) –7.606 (7.062) Infectious diseases –58.718*** (22.266) –33.065* (20.069) –40.098* (22.806) –0.792 (25.469) Per capita income 0.001*** (0.0002) Income inequality –0.640*** (0.239) Secondary school enrollment 0.371*** (0.097) No. of observations 54 53 50 52 Adjusted R2 0.10 0.34 0.20 0.29 Notes: The dependent variable is Interpersonal Trust. White heteroskedas- ticity-constant standard errors in parentheses. ***Significant at 1%; **sig- nificant at 5%; *significant at 10%. 6For example, Wang et al. [2] survey trust by measuring levels o f trustworthiness and mistrust separately. They find that a low level o f trust does not necessarily mean a high level of mistrust. They suggest that when surveying trust, researchers asking questions regarding trust should be careful to separate those emphasizing mistrust from those emphasizing trust and report them differently. This is because their research shows that the effects of low levels of trust can differ from those of hi g h mistrust [ 2 ] . 7We also included primary education in the regression.The result reveals that the infectious disease index has a negative and significant effect, as expected. However, the coefficient on primary educationis negative and insignificant. Possible explanation for this is that primary education is more universal than secondary education across countries. Thus, secondary education was much more effective in explaining trust.  D. Gonzalez-Medina et al. / Health 3 (2011) 206-210 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 209209 Table 2. OLS Regression: Infectious Diseases on Interpersonal Trust (included HIV/AIDS/STIs cases). Independent variables (1) (2) (3) (4) Constant 16.691*** (3.882) 12.666** (3.297) 42.630*** (11.468) –7.291 (7.209) Infectious diseases –40.052*** (15.454) –21.913* (13.286) –22.112* (12.784) –4.479 (16.777) Per capita income 0.001*** (0.0001) Income inequality –0.623** (0.260) Secondary school enrollment 0.358*** (0.094) No. of observations 52 51 49 51 Adjusted R2 0.10 0.40 0.20 0.29 Notes: The dependent variable is Interpersonal Trust. White heteroskedas- ticity-constant standard errors in parentheses. *** Significant at 1%; ** significant a t 5 %; * s i gnificant at 10%. WHO does not report HIV/AIDS/STIs in the WHS [12], yet it is one of the serious infectious diseases. Stigma and discrimination are common problems facing people living with HIV/AIDS/STIs. Because of such stigma and discrimination, HIV/AIDS/STIs is in turn associated with decreased trust. We extend our analysis to include HIV/AIDS/STIs in the principal component analysis to extract a new index of infectious diseases. The OLS regression results are reported in Table 2 with the new index. In equation 1, the index of infectious diseases is significantly correlated with trust per expec- tation at the 1% level. This equation explains 10% of the variation in trust. The index of infectious diseases re- mains negative and statistically significant at the 10% level when income per capita is included in equation 2. This equation explains 40% of the variation in trust. When income inequality is added to equation 3, the in- dex of infectious diseases remains robustly significant at the 10% level. When human capital is tak en into accou nt in equation 4, the infectious disease in dex has a negative, but insignificant effect on trust. The statistical results indicate that high levels of in- fectious diseases have a significant effect on lowering trust levels, suggesting that infectious diseases can sa- botage interpersonal trust causing a decline in social capital. 4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION The empirical results indicate that higher cases of in- fectious diseases are negatively associated with trust in a sample of 54 countries with robust estimates. The find- ings are strong enough to motivate a shift in perspective when studying factors of infectious disease. We seek to underscore the relevance of social capital in this discus- sion. Specifically, the literature surveying experiences of infected people suggests that stigma and low interper- sonal trust are caused by factors of fear and perceived threat of infection [3,4,6,8,9]. And since risk perception necessarily precedes stigma, we affirm that it is the in- cidence and subsequent risk perception that causes stig- matizing reactions and falling levels of interpersonal trust. Targeting stigma, as the literature suggests, may be an effective measure to improve interpersonal trust and de- crease infectious disease. Targeting stigma enhances in- terpersonal trust through open dialogue and approval of social bonds once broken by stigma. Similarly, targeting sources of stigma reduces the levels of infection diseases by making healthcare more approachable and trustwor- thy in areas where healthcare was once a source of stigma. To reap the benefits of trust, efforts are required to coun- teract discrimination and stigma against those targeted. REFERENCES [1] Zak, P. and Knack, S. (2001) Trust and growth. The Eco- nomic Journal, 470, 295-321. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00609 [2] Wang, H., Schlesinger, M. and Hsiao, W.C. (2008) The flip-side of social capital: The distinctive influences of trust and mistrust on health in rural China. Social Science & Medicine, 68, 133-142. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.038 [3] Gupta, A.K. (2004) Integrated approach for leprosy elimination in India. Journal of Development and Social Transformation, 1, 31-36. [4] Gostin, L. and Hodge, J. (1999) Reforming state public health law. Turning Point. http://www.publichealthlaw.net/Resources/ResourcesPD Fs/Alaska.pdf. [5] Anderson, M., Elam, G., Gerver, S., Solarin, I., Fenton, K. and Easterbrook, P. (2008) HI V/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: Accounts of HIV-positive Caribbean people in the United Kingdom. Social Science & Medi- cine, 67, 790-798. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.003 [6] Citrin, D. (2006) Somali tuberculosis cultural profile. http://ethnomed.org/clinical/tuberculosis/somali-tb-cultur al-profile. [7] Setbon, M., Raude, J. and Pottratz, D. (2008) Chikun- gunya on Réunion Island: Social, environmental and be- havioural factors in an epidemic context. Population, 63, 491-518. doi:10.3917/pope.803.0491 [8] Baral, S.C., Deepak, K.K. and Newell, J.N. (2007) Causes of stigma and discrimination associated with tu- berculosis in Nepal: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 7, 211. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-211 [9] Herek, G.M., Mitnick, L., Burris, S., Chesney, M., De- vine, P., Fullilove, M.T., Fullilove, R., Gunther, H.C.,  D. Gonzalez-Medina et al. / Health 3 (2011) 206-210 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 210 Levi, J., Michaels, S., Novick, A., Pryor, J., Snyder, M. and Sweeney, T. (1998) Workshop report: AIDS and stigma: A conceptual framework and research agenda. AIDS Public Policy Journal, 13, 36-47. [10] Zak, P. and Fakhar, A. (2006) Neuroactive hormones and interpersonal trust: International evidence. Economics and Human Biology, 4, 412-429. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2006.06.004 [11] Barro, R. (1991) Economic growth in a cross section of countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 407-443. doi:10.2307/2937943 [12] World Health Organization: World Health Statistics. 2009: 50-69. http://www.who.int/entity/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS09_ Full.pdf. [13] Knack, S. and Keefer, P. (1997) Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Quarterly of Journal Economics, 112, 1251-1288 doi:10.1162/003355300555475 [14] Inglehart, R. et al. (2000) World values surveys and European values surveys, 1981-1984, 1990-1993 and 1995-1997. ICPSR Study No. 2790, Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. [15] Inglehart, R., Basáñez, M., Díez-Medrano, J., Halman, L. and Luijkx, R. (2004) Human beliefs and values, a cross-cultural sourcebook based on the 1999-2002 values surveys. siglo XXI editores, S. A. de C.V., Mexico. [16] Keefer, P. and Knack, S. (2002) Polarization, politics and property rights: Links between inequality and growth. Public Choice, 111, 127-154 doi:10.1023/A:1015168000336 [17] World Development Indicators 2009. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. |