Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 2014, 2, 54-59 Published Online June 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/gep http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/gep.2014.23007 How to cite this paper: Zhang, Y. Q., & Welker, J. M. (2014). Global Warming Impacts on Alpine Vegetation Dynamic in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 2, 54-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/gep.2014.23007 Global Warming Impacts on Alpine Vegetation Dynamic in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China Yan Qing Zhang1*, Jeffery M. Welker2 1Department of Geography, School of Computing Science, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada 2Environment and Natural Resources Institute, University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, USA Email: *instca@yahoo.com Received March 2014 Abstract This study is to illustrate alpine vegetation dynamics in Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau of China from simulated filed experimental climate change, vegetation community dynamic simulation integrat- ed with scenarios of global temperature increase of 1 to 3˚C, and simulated regional alpine vegeta- tion distribution changes in responses to global warming. Our warming treatment increased air temperatures by 5˚C on average and soil temperatures were elevated by 3˚C at 5 cm depth. Above- ground biomass of grasses responded rapidly to the warmer conditions whereby biomass was 25% greater than that of controls after only 5 wk of experimental warming. This increase was ac- companied by a simultaneous decrease in forb biomass, resulting in almost no net change in community biomass after 5 wk. Under warmed conditions, peak community bio-mass was ex- tended into October due in part to continued growth of grasses and the postponement of senes- cence. The Vegetation Dynamic Simulation Model calculates a probability surface for each vegeta- tion type, and then combines all vegetation types into a composite map, determined by the maxi- mum likelihood that each vegetation type should distribute to each raster unit. With scenarios of global temperature increase of 1˚C to 3˚C, the vegetation types such as Dry Kobresia Meadow and Dry Potentilla Shrub that are adapted to warm and dry conditions tend to become more dominant in the study area. Keywords Global Warming, Alpine Vegetaion, Qing h a i -Tibet Plateau 1. Introduction Global temperatures are increasing due to the effects of greenhouse gases emission. It is projected that climate changes will have profound biological effects, including the changes in species distributions as well as vegeta- tion patterns (Walther et al., 2002; Klanderud & Birks, 2003; Tape et al., 2006). Many results from observations *Corresponding author.  Y. Q. Zhang, J. M. Welker and experiments (Sullivan & Welker, 2005), and simulation studies (Zhang, Yang , et al., 1996; Ni, 2000; Song et al., 2005) have depicted shifts in the distribution of vegetation boundary and the mixture of shrubs and grasses. The Tibetan Plateau covers approximately 2.5 million km2 with an average altitude of more than 4000 m dominated by alpine tundra (Zheng, 1996). Alpine tundra vegetation is predicted to be one of the most sensitive terrestrial ecosystems to changing climate (Chapin et al., 1992, 2000). This type of ecosystem is composed of slow-glowing plants and are dominated by the soils which can be concentrated with high organic matter near surface soil that undergo frost heave and cryoturbation (Billings, 1987; Xia, 1988). Simultaneously, warmer weather may increase plant growth, and primary production (Wookey et al., 1995) as well as changes in species dominance (Walker et al., 1994; Klein et al., 2007). Based on 38 years (1959-1996) of climate observations and statistical analysis, the annual mean temperature increased during this period ranged from 0.4˚C to 0.6˚C in the area of Haibei Alpine Tundra Ecosystem Re- search Station (Li et al., 2004), that is located on northeastern part of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (37˚N, 101˚E). In order to study alpine tundra vegetation changes at the regional scale, we model alpine tundra vegetation spatial and temporal dynamics in response to global warming by integrating a raster-based cellular automata and a Geographic Information System (Zhang et al., 2008). Temperature changes across the study area are not only due to elevation, but also to aspect and distance from the nearest stream channel. The liner regression model provided a temperature spatial distribution based on elevation alone, which is the primary step. The normalized temperature surface created by the Multi-Criteria Evaluation (MCE) is highly representative of the potential temperature distribution in a normalized fuzzy format. Assuming each vegetation type in the raster cell unit re- acts as homogeneous entity, we conduct a spatial and temporal simulation by combining cellular automata and MCE provided in the IDRISI software (Eastman, 2003). 2. Alpine Tundra above Ground Biomass and Community Responses to Simulated Changes in Climate 2.1. Experimental Treatments and Observations Our experiment research site is located near Haibei Alpine Meadow Ecosystem Station (37˚N, 101˚E) at an ele- vation of 3250 m (Xia, 1989). The vegetation of our field site is typical of a Kobresia humilis meadow (Zhang & Zhou, 1992). The greenhouse treatment increased mean air temperature by 20% from 12.4˚ to 17.8˚ Cover the course of the growing season. Warmer air temperature subsequently caused higher soil temperatures at 5, 10, and 15 cm under greenhouse (G) as opposed to ambient (C) conditions (Zhang & Welker, 1996). 2.2. Results and Discussion Total community aboveground biomass in all four treatments was not significantly different in July. The peak aboveground biomass between Greenhouse (G), occurred in September 351.36 g∙m−2, and ambient (C) condition, occurred in October 346.19 g∙m−2. Total maximum aboveground biomass at our Tibetan alpine tundra site ranged from 161 to 351 g∙m−2 under ambient conditions. These ranges in biomass are similar to the peak aboveground biomass at other alpine tundra sites such as on Niwot Ridge, Colorado, U.S.A., where the intercommunity aboveground biomass in different vegetation types ranges from 71 to 309 g∙m−2 (Walker et al., 1994). Our environmental manipulations simulating climate warming resulted in warmer air and soil temperatures between 1˚C and 5˚C, which is within the ranges of increase reported for higher elevations in Western Europe over the past 15 years ( Grabherr et al., 1994) and is within the ranges predicted for tundra habitats under a doubling of CO2 over the next 50 yr (Maxwell et al., 1992). The season long average increases are also similar to those accomplished in other tundra experimental warming treatments though our lack of nighttime measurements means our averages are slightly higher than those actually experienced by plants and soil in these treatment plots (Chapin & Shaver, 1985; Wookey et al., 1993). However, most importantly, higher temperatures were maintained in our warmed plots into October and may partially explain the extended growing season observed for grasses (Zhang & Welker, 1996). In conclusion, our findings suggest that Tibetan alpine grasses are predisposed to rapid increases in biomass under simulated climate warming due in part to their inherent life history traits. In addition, the ability of grasses to produce tillers late in the season under warmer conditions extends the period of carbon gain and extends the  Y. Q. Zhang, J. M. Welker period in which the community exhibits maximum aboveground biomass. We find that sedges at our site are in- sensitive in the short term to changes in environmental conditions, while forbs may decrease at the expense of grass biomass. Increases in cloudiness over the Tibetan alpine tundra would likely result in lower aboveground biomass, but if accompanied by higher rainfall the effects may be counter-acting. The extension of peak com- munity biomass into the autumn may in the long term have cascading effects on net ecosystem CO2 fluxes, nu- trient cycling, and forage availability in the alpine ecosystem (Welker et al., 2004). 3. Cellular Automata: Simulating Alpine Tundra Vegetation Dynamics in Response to Global Warming 3.1. Vegetation Dynamic Simulation Model (VDSM) Spatial modeling processes are available in current Geographic Information System (GIS) software such as IDRISI, which is capable of dealing with a large set of raster data and manipulating the data via operations in a series of discrete time steps, where single raster cells can be influenced by their neighborhood or other data in an overlay. All map layers are imposed on the same grid system. This type of GIS environment provides a sophis- ticated tool to help us target the real problem in a complex system (Wolfram, 1984; Itami, 1994; Shanmugana- than et al., 2011). In our study, we use GIS analysis, linear regression, MCE, cellular automata (CA), and a raster image calculator to build a unique Vegetation Dynamic Simulation Model (VDSM) (Figure 1). Global warming scenarios are interpreted as inputs of the spatial parameters. Large processing tasks are completed by the computer system. Figure 1. Vegetation Dynamic Simulation Model (VDSM).  Y. Q. Zhang, J. M. Welker The predicted outcome of this study is that individual vegetation types will respond to a global mean tem- perature increase (GMTI) in 2100 of 1˚C or 3˚C by either expanding or shrinking their range because of plant species’ suitability to the warmer and drier climate conditions. This corresponds to 0.1˚C or 0.3˚C per decade, respectively (Leemans, 2004). 3.3. Results and Discussions Temperature changes across the study area are not only due to elevation, but also due to aspect and distance from the nearest stream channel. The linear regression model provided a temperature spatial distribution based on elevation alone, which is our primary step. Furthermore, the normalized temperature surface created by the MCE is highly representative of the potential temperature distribution in a normalized fuzzy format, showed as Normalized temperature spatial distribution (Figure 2). Temperature distribution is correlated with and con- trolled primarily by elevation. Numerous spatial interpretation methods have been applied to estimate the spatial distribution of temperature (Li, 2005). The interpolation results do not always agree with the actual sample points, including using geo-statistical methods, and spatio-temporal spline. These methods are highly dependent on the distance to the sample points, and the surface equation. In our study, our first step is to create the primary temperature surface based a linear relation with elevation. The objective is to obtain a more accurate temperature map in terms of aspect, suitable temperature, and distance to the stream. We use the Multi-Criteria Evaluation Figure 2. Normalized temperature with values from 0 to 255.  Y. Q. Zhang, J. M. Welker with Weighted Linear Combination (MCE_WLC) to calibrate the spatial temperature distribution. The fuzzy memberships between the temperature and each factor (aspect, suitable temperature, distance to stream) are based on previous research works (Zhang & Zhou, 1992; Zhang & Welker, 1996, Zhang et al., 2008, 2010). The output, the normalized temperature surface is set into fuzzy format (0 - 255). Since the temperature is major factor on determining vegetation composition, structure, and distribution, the normalized temperature surface plays an important role when we simulate vegetation dynamics in spatial and temporal dimensions. The VDSM integrates the suitability maps created from MCE, Macro-Modeler, CA, and spatial environ- mental factors. And the temperature-time dimension model is incorporated into the VDSM, which makes the temperature a spatial parameter that affects the vegetation dynamics over a discrete time step. The simulating processes conducted by Macao Modeler generate the temperature increase of 0.1˚C to 0.3˚C per decade, which represents the influences of the different global warming scenarios. The results demonstrate that global tem- perature increase reduces moisture availability (Zhang & Welker, 1996) such that dry vegetation can invade ar- eas previously occupied by vegetation adapted to moist conditions. The structure of the model is generally ap- plicable to other situations, but the particular factors and constraints used in this model are unique to the Haibei alpine tundra ecosystem. References Billings, W. D. (1987). Constraints to Plant Growth, Reproduction and Establishment in Arctic Environments. Arctic and Alpine Research, 19, 357-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1551400 Chapin, F. S., & Shaver, G. R. (1985). Individualistic Growth Response of Tundra Plant Species to Environmental Manipu- lations in the Field. Ecology, 66, 564-576. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1940405 Chapin, F. S., Jefferies, R. L., Reynolds, J. E, & Svoboda, J., (1992). Arctic Plant Physiological Ecology in an Ecosystem Context. In, E. S. Chapin, R. L. Jefferies, J. E. Reynolds, G. R. Shaver, & J. Svoboda (Eds.), Arctic Ecosystems in a Changing Climate: An Ecophysiological Perspective (pp. 441-452). San Diego: Academic Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-168250-7.50027-4 Chapin, F. S., III, McGuire, A. D., Randerson, J., Pielke, R. Sr, Baldocchi, D., Hobbie, S. E., Roulet, N., Eugster, W., Kasis- chke, E., Rastetter, E. B., Zimov, S. A., & Running, S. W. (2000). Arctic and Boreal Ecosystems of Western North Amer- ica as Components of the Climate System. Global Change Biology, 6, 211-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.06022.x Coulelis, H. (1985). Cellular World: A Framework for Modeling Micro-Macro Dynamics. Environment and Planning A, 17, 585-596. http://dx.doi.org/10.1068/a170585 Eastman, J. R. (2003). IDRISI Kilimanjaro Tutorial. Manual Version 14.0. Worcester, Massachusetts: Clark Labs of Clark University, 61-123. Grabherr. G., Gottfried, M., & Pauli, H. (1994). Climate Effects on Mountain Plants. Nature, 369, 448-450. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/369448a0 Itami, R. M. (1994). Simulating Spatial Dynamics: Cellular Automata Theory. Landscape and Urban Planning, 30, 27-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(94)90065-5 Klanderud, K., & Birks, H. J. B. (2003). Recent Increases in Species Richness and Shifts in Altitudinal Distributions of Norwegian Mountain Plants. Holocene, 13, 1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0959683603hl589ft Klein, J. A., Harte J., & Zhao, X. Q. (2007). Experimental Warming, Not Grazing, Decreases Rangeland Quality on the Ti- betian Plateau. Ecological Applications, 17, 341-557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/05-0685 Leemans, R. E. (2004). Another Reason for Concern: Regional and Global Impacts on Ecosystems for Different Levels of Climate Change. Global Environmental Change, 14, 219-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.04.009 Li, Y. N., Zhao, X. Q., Cao, G. M., Zhao, L., & Wang, Q. X. (2004). Analysis on Climates and Vegetation Productivity Background at Haibei Alpine Meadow Ecosystem Research Station. Plateau Meteorology, 23, 558-567. Li, X., Cheng, G. D., & Lu, L. (2005). Spatial Analysis of Air Temperature in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 37, 246-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1657/1523-0430(2005)037[0246:SAOATI]2.0.CO;2 Maxwell, B. (1992). Arctic Climate: Potential for Change under Global Warming. In F. S. Chapin, R. L. Jefferies, J. F. Rey- nolds, G. R. Shaver, & J. Svoboda (Eds.), Arctic Ecosystems in a Changing Climate: An Ecophysiological Perspective (pp. 11-34). San Diego: Academic Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-168250-7.50008-0 Ni, J. (2000). A Simulation of Biomes on the Tibetan Plateau and Their Responses to Global Climate Change. Mountain Re- search and Development, 20, 80-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2000)020[0080:ASOBOT]2.0.CO;2 Shanmuganathan, S., Ajit Narayanan, A. , & Robinson, N. (2011). A Multi-Agent Cellular Automaton for Grapevine Growth  Y. Q. Zhang, J. M. Welker and Crop Simulation. International Journal of Machine Learning and Computing (IJMLC), 1, 291-296. http://dx.doi.org/10.7763/IJMLC.2011.V1.43 Song, M., Zhou, C., & Ouyang, H. (2005). Simulated Distribution of Vegetation Types in Response to Climate Change on the Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Vegetation Science, 16, 341-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2005.tb02372.x Sullivan, P. F., & Welker, J. M. (2005). Warming Chambers Stimulate Early Season Growth of an Arctic Sedge: Results of a Minirhizotron Field Study. Oecologia, 142, 616-626. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1764-3 Tape, K., Sturm, M., & Racine, C. (2006). The Evidence for Shrub Expansion in Northern Alaska and the Pan-Arctic. Global Change Biology, 12, 686-702. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01128.x Walker, M. D., Webber, P. J., Arnold, E. H., & Ebert-May, D. (1994). Effects of Interannual Climate Variation on Above- ground Phytomass in Alpine Vegetation. Ecology, 75, 393-408. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1939543 Walther, G. R., Post, E., Convey, P., Menzel, A., Parmesan, C., Beebee, T. J. C., Fromentin, J. M., Hoegh-Guldberg, O., & Bairlein, F. (2002). Ecology Responses to Recent Climate Change. Nature, 416, 389-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/416389a Welker, J. M., Fahnestock, J. T., Povirk, K., Bilbrough, C., & Piper, R. (2004). Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics in a Long- Term Grazed Alpine Grassland. Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research, 36, 10-19. Wolfram, S. (1984). Cellular Automata as Models of Complexity. Nature, 311, 419-424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/311419a0 Wookey, P. A., Parsons, A. N., Welker, J. M., Potter, J., Callaghan, T. V., Lee, J. A., & Press, M. C. (1993). Comparative Responses of Phonology and Reproductive Development to Simulated Environmental Change in Sub-Arctic and High Arctic Plants. Oikos, 67, 490-502. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3545361 Wookey, P. A., Robinson, C. H., Parsons, A. N., Welker, J. M., Press, M. C., Callaghan, T. V., & Lee, J. A. (1995). Envi- ronmental Constraints on the Growth, Photosynthesis and Reproductive Development of Dry as Octopetala at a High Arc- tic Polar Semi-Desert, Svalbard. Oecologia, 102, 478-489. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00341360 Xia, W. P. (1988). A Brief Introduction to the Fundamental Characteristics and the Work in Haibei Research Station of Al- pine Meadow Ecosystem. Proceedings of the International Symposium of an Alpine Meadow Ecosystem. Beijing: Aca- demic Sinica, 1-10. Zhang, X. S., Yang, D. A., Zhou, G. S., Liu, C. Y., & Zhang, J. (1996). Model Expectation of Impacts of Global Climate Change on Biomes of the Tibetan Plateau. In K. Omasa, K. Kai, H. Taoda, Z. Uchijima, & M. Yoshino (Eds.), Climate change and plants in East Asia (pp. 25-38). Tokyo, JP: Springer-Verlag. Zhang, Y. Q., & Zhou, X. M. (1992). The Quantitative Classification and Ordination of Haibei Alpine Meadow. Acta Phy- toecological ET Geobotanica Sinica, 16, 36-42. Zhang, Y. Q., & Welker, J. M. (1996). Tibetan Alpine Tundra Responses to Simulated Changes in Climate: Aboveground Biomass and Community Responses. Arctic and Alpine Research, 28, 203-209. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1551761 Zhang, Y. Q. A., Peterman, M. R., Aun, D. L., & Zhang, Y. M. (2008). Cellular Automata: Simulating Alpine Tundra Vege- tation Dynamics in Response to Global Warming. Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research, 40, 256-263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1657/1523-0430(06-048)[ZHANG]2.0.CO;2 Zhang, Y. Q. A., Song, M. H., & Welker, J. M. (2010). Simulating Alpine Tundra Vegetation Dynamics in Response to Global Warming in China, Global Warming. InTech. http://www.intechopen.com/books/global-warming/simulating-alpine-tundra-vegetationdynamics-in-response-to-global-w arming-in-china Zheng, D. (1996). The System of Physico -Geographical Regions of the Tibet Plateau. Science in China Series D, 39, 410-417.

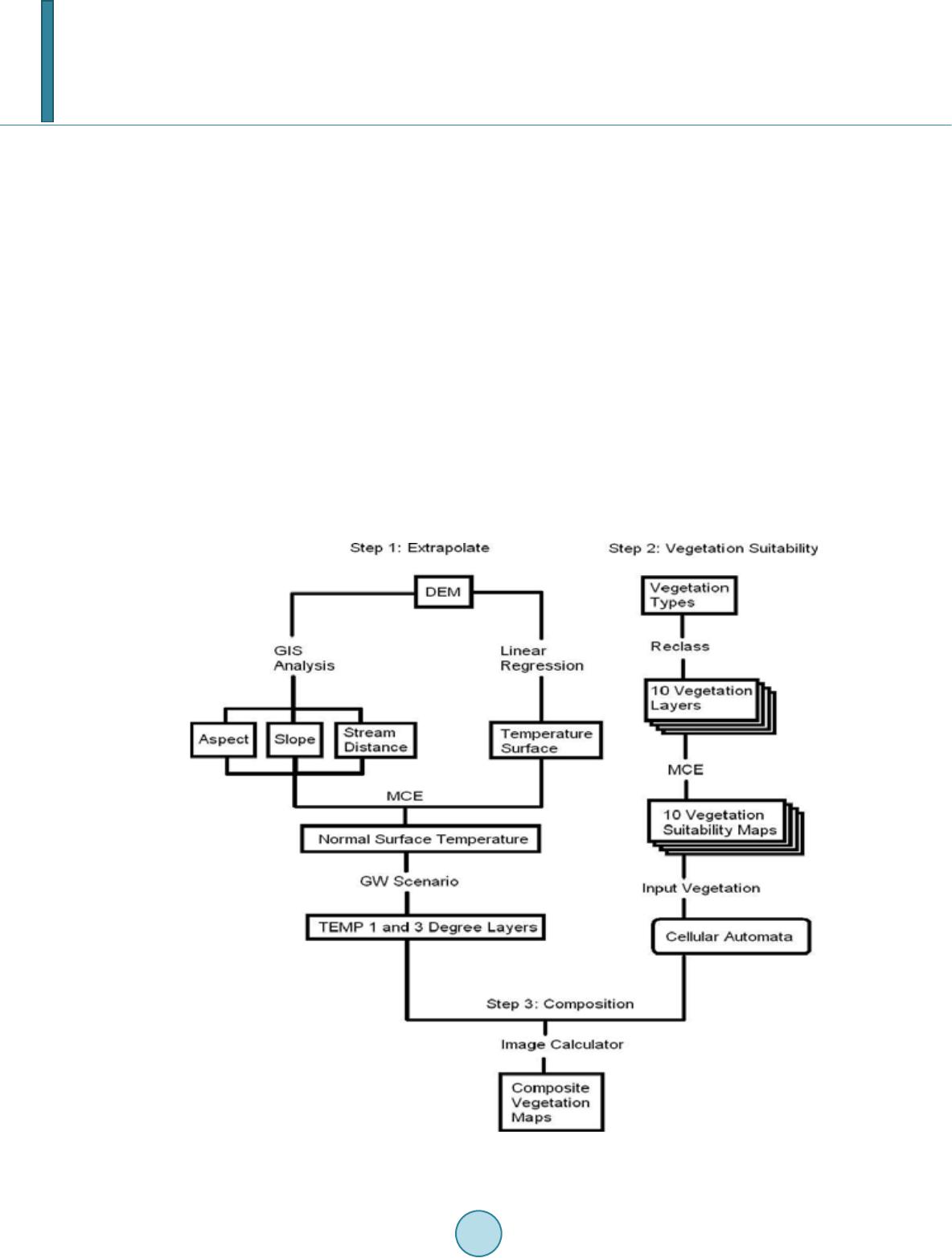

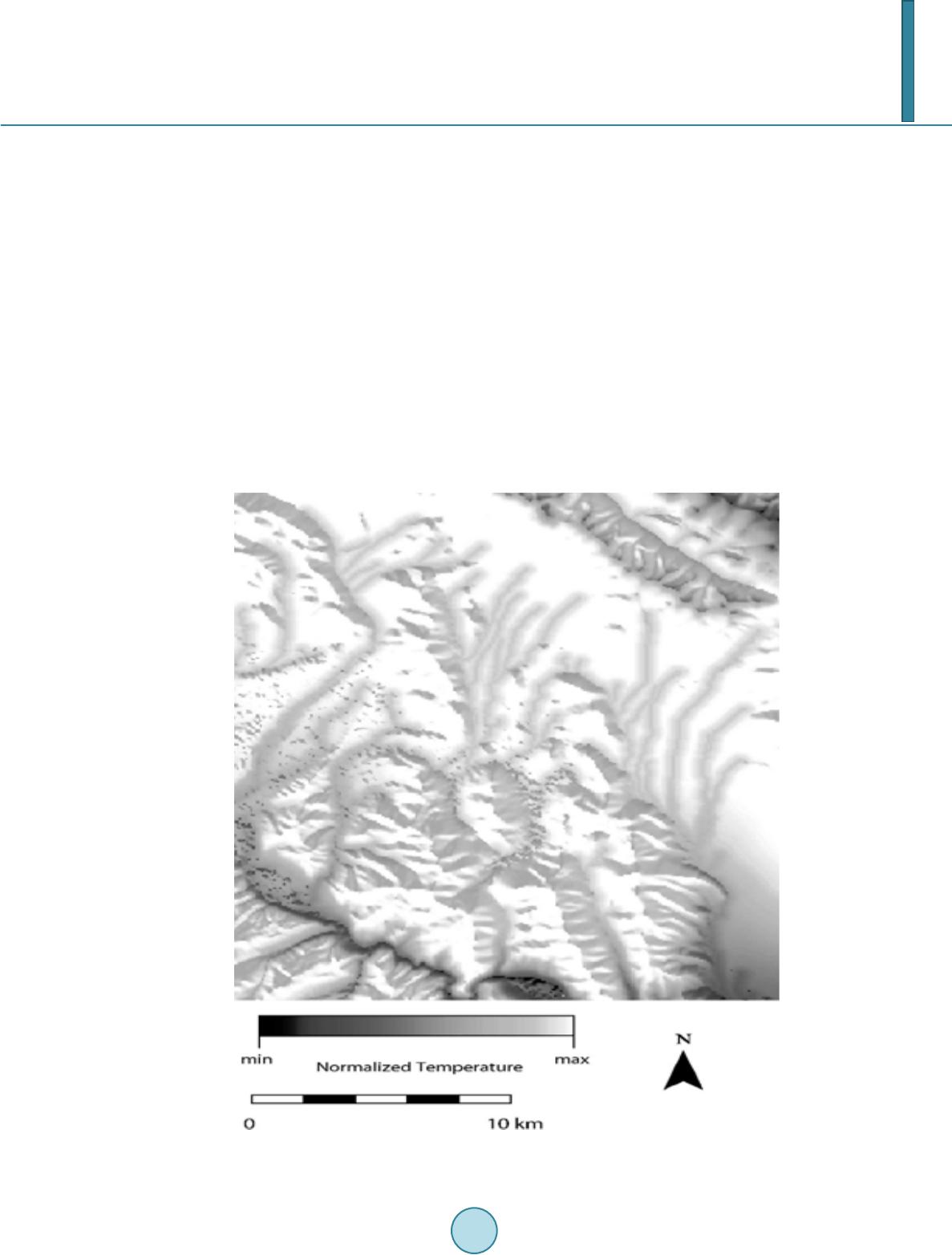

|