Sociology Mind 2011. Vol.1, No.2, 36-44 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/sm.2011.12005 Social Exclusion in Non-Government Organizations’ (NGOs’) Development Activities in Bangladesh M. Rezaul Islam1, Koyela Sharmin2 1Institute of Social Welfare and Research, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh; 2Theatre Activist Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), Lalmatia, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Email: {rezauldu, koyelasharmin}@gmail.com Received February 4th, 2011; revised February 13th, 2011; accepted February 14th, 2011. This paper explores the nature and causes of social exclusion of the NGOs’ activities in Bangladesh. Data gath- ered from two NGOs (Proshika and Practical Action Bangladesh) working for the socio-economic development in Bangladesh. The paper shows that now a day the NGOs’ target groups and services have been specified to the people who are able to return back their micro-credit. As a result many people are now being excluded from NGO services who are known as ‘ultra poor’. The findings of this paper show that many blacksmiths and gold- smiths were out of services from both NGOs rather the NGOs selected purposeful target groups, replicate of program, and their short-term development approach, high-flying profile, rent seeking attitude, monolithic de- velopment approach, lack of accountability, complex loan procedure and high interest rate, and cut-off budget from their development project were helpful for such kind of social exclusion. The paper argues that that without inclusion of such groups of people, the overall socio-economic development would not be possible. Keywords: Social Exclusion, Social Inclusion, NGOs, Development, Bangladesh Introduction This paper looks the nature and causes of social exclusion of the NGOs’ activities in Bangladesh. The research reported in this article selected two programs from two leading NGOs in Bangladesh: the Markets and Livelihoods Program (MLP) of Practical Action Bangladesh (PAB) and the Small Economic Enterprise Development (SEED) program of Proshika. The study further selected two groups of people, blacksmiths (MLP) and goldsmiths (SEED), from two communities served by those NGOs. The article argues that most of the NGOs in Bangladesh are included those people as target groups who are capable to return back their credit and the people who are not being ex- cluded. As a result a huge number of people are now out of the NGO services who are known as ‘ultra poor’. The findings of this paper show that there are many blacksmiths and goldsmiths in those projects areas who were excluded from both NGOs services rather the NGOs selected purposeful target groups, replicate of program, and their short-term development ap- proach, high-flying profile, rent seeking attitude, monolithic development approach, lack of accountability, complex loan procedure and high interest rate, and cut-off budget from their development project were helpful for such kind of social exclu- sion. The paper argues that without inclusion of such groups of people, the overall socio-economic development would not be possible. Social Exclusion and Social Inclusion in Development The term ‘social exclusion’ is relatively recent origin in the development studies (Bynner, 1998) and the meanings associ- ated with it have evolved quickly. From use as a synonym of poverty through the 1960s and 1970s (Gauthier, 1995) to broad, relational analyses of the exclusionary forces in social structure and power, there is a wide gamut of thought on many of the numerous aspects of social exclusion. It is because the vision of a society in this 21 centuries has been outlined as: a society which would be characterized by a economic vibrancy; ensured basic needs of all citizens; participatory democracy; social jus- tice; women’s rights and equal opportunities; good governance based on rule of law, transparency, and accountability; guaran- teed human rights for all; non-communal and progressive social framework; and a pollution free natural environment (Ahmad, 2009). In this perspective, the term ‘social inclusion’ with so- cial exclusion becomes an important concept in the world. Social exclusion is a ‘process through which individuals or groups are wholly or partially excluded from the society in which they live in’. The socially excluded are not a homoge- nous group — they consist of many different groups, hierarchi- cal as well as horizontal (Ahmad, 2009). The DFID (2005) also describes this as a process by which certain groups are system- atically disadvantaged, because they are discriminated against on the basis of their ethnicity, race, religion, sexual orientation, caste, descent, gender, age, disability, HIV status, migrant status or where they live. Here discrimination occurs in public institutions, such as the legal system or education and health services, as well as social institutions like the household, and in the community. On the other hand, Raphael (2004) broadly describes this both the structures and the dynamic processes of inequality among groups in society which, over time, structure access to critical resources that determine the quality of mem- bership in society and ultimately produce and reproduce a com- plex of social outcomes. Here he considers social exclusion both as process and outcome. Kabeer (2006) focuses on the multiple and overlapping as- pects of disadvantage not captured by conventional approaches  M. R. ISLAM ET AL. 37 to poverty with their concentration on economic disadvantage and shortfalls in the satisfaction of basic needs. He agrees with the statement of the DFID (2005) that the spatial dimension of poverty thus reflects not only economic or resource deprivation but also identity-based discrimination: it is usually culturally devalued and economically impoverished groups that inhabit physically deprived or marginalised spaces. Saloojee (2001:2) explains this concept from more social angel that the concept is highly compelling because it speaks the language of oppression and enables the marginalized and victimized to give voice and expression to the ways in which they experience the driving forces of our society. It is very much a lived experience that occurs in many different settings and affects, such as street children, former prisoners, single parents, ethnic minorities and more. It can occur as a result of an equally wide variety of fac- tors, including unemployment, poor health, a lack of education or affordable housing, racism, fear of differences or political disempowerment (Guildford, 2000:4). Saloojee (2001:2) has identified multiple and varied sources of exclusion including: Structural/economic (iniquitous economic conditions; low wages, dual and segregated labour markets; etc.); Historical oppression (colonialism); Discrimination; The absence of legal/political recognition; Institutional/civic non acceptance; Self-exclusion. On the other hand, inclusion is a term that is familiar to most people in their everyday lives – we feel included, or excluded, for example, from family, neighbourhood, or community ac- tivities (Shookner, 2002). But social inclusion is even more than participating and feeling valued; it is also having what is needed materially and socially to live comfortably (Maritime Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, 2000). The Cana- dian Council on Social Development, drawing on the work of Amartya Sen, sees an inclusive society as characterized by a widely shared social experience and active participation, by a broad equality of opportunities and life chances for individuals and by the achievement of a basic level of well-being for all citizens (Jackson, 2001). In broader perspective social inclusion means that everybody must be equitably included, and nobody excluded. That is, the inclusive social transformation process must ensure every- body’s equitable participation in its constituent sub-processes – economic, social, political, environment, and so on (Ahmad, 2009). Inclusion is about society changing to accommodate difference, and to combat discrimination. It sees society as the problem, not the person. To achieve inclusion, a twin track approach is needed: Focus on the society to remove the barriers that exclude. (mainstreaming) Focus on the group of persons who are excluded, to build their capacity and support them to lobby for their inclu- sion. Inclusive Development therefore is the process of ensuring that all marginalized/excluded groups are included in the deve- lopment process (IDDC Paper, undated). The Laidlaw Foundation in Canada has done extensive work on the subject of social inclusion and mentions the following characteristics: Social inclusion is about making sure that all people par- ticipate as valued members of society, rather than just bringing people on the outside ‘in’. It is a normative concept (i.e. value-based) rather than a descriptive term. It is a way of ‘raising the bar’ – of un- derstanding where we want to be and what needs to change. It helps to guide the development of forward- looking indicators, rather than merely documenting ‘what’s wrong.’ It suggests a transformative agenda that points to the changes that are necessary in public policies, attitudes and institutional practices. Social inclusion requires more than the removal of barri- ers. It requires investments and actions to bring about the conditions of inclusion (Freiler, 2001:2). It is more than a critique of oppression, injustice, discrimin- ation and the other systemic factors that lead to social exclusion. It promotes a transformative agenda that aims to eliminate the barriers to full social and economic participation and create a more just and equitable world. Social inclusion, therefore, has value on its own as both a process and a goal; it is about under- standing where we want to be and how to get there. Saloojee (2001:7-8) suggests that social inclusion moves beyond an ex- clusion framework in a number of fundamental respects. He notes: Social inclusion is the political response to exclusion. Most analyses of racism and sexism, for example, focus on the removal of systemic barriers to effective participa- tion and focus on equality of opportunity. Social inclusion is proactive. It is about anti-discrimina- tion. It is not about the passive protection of rights, it is about the active intervention to promote rights and it confers responsibility on the state to adopt policies that will ensure social inclusion of all members of society (not just formal citizens, consumers, taxpayers). Social inclusion, by virtue of the fact that it is both proc- ess and outcome, can hold governments and institutions accountable for their policies. The yardstick by which to measure good government becomes the extent to which it advances the well-being of the most vulnerable and most marginalized in society. Social inclusion is about advocacy and transformation. It is about the political struggle and political will to remove barriers to full and equitable participation in society by all. Social inclusion is embracing. It posits a notion of de- mocratic citizenship as opposed to formal citizenship. Democratic citizens possess rights and entitlements by virtue of their being a part of the polity, not by virtue of their formal status (as immigrants, refugees or citizens). Shookner’s Inclusion Lens (2002) identifies (Table 1) some of the elements of exclusion and inclusion and the different dimensions in which they operate: cultural, economic, func- tional, participatory, physical, political, relational, and struc- tural. Social Exclusion, Poverty and NGOs in Bangladesh The relationship between social exclusion and poverty is well recognized in development studies. Both concepts are getting more popular to the developing countries, especially in Africa  M. R. ISLAM ET AL. 38 Table 1. An inclusion lens: workbook for looking at social and economic exclusion and inclusion. Elements of Exclusion Dimensions Elements of Inclusion Disadvantage, fear of differences, intolerance, gender stereotyping, historic oppression, cultural deprivation. Cultural Valuing contributions of women and men to society, recognition of differ- ences, valuing diversity, positive identity, anti-racist education. Poverty, unemployment, non-standard employment, inadequate income for basic needs, participation in society, stigma, embarrassment, inequality, income disparities, deprivation, insecurity, devaluation of care giving, illiteracy, lack of educational access. Economic Adequate income for basic needs and participation in society, poverty eradi- cation, employment, capability for personal development, personal security, sustainable development, reducing disparities, value and support care giving. Disability, restrictions based on limitations, overwork, time stress, undervaluing of assets available. Functional Ability to participate, opportunities for personal development, valued social roles, recognizing competence. Marginalization, silencing, barriers to participation, institutional dependency, no room for choice, not involved in decision making. Physical Access to public places and community resources, physical proximity and opportunities for interaction, healthy/supportive environments, access to transportation, sustainability. Denial of human rights, restrictive policies and leg- islation, blaming the victims, short-term view, one dimensional, restricting eligibility for programs, lack of transparency in decision making. Political Affirmation of human rights, enabling policies and legislation, social pro- tection for vulnerable groups, removing systemic barriers, will to take action, long-term view, multi-dimensional, citizen participation, transparent decision making. Isolation, segregation, distancing, competitiveness, violence and abuse, fear, shame. Relational Belonging, social proximity, respect, recognition, cooperation, solidarity, family support, access to resources. Discrimination, racism, sexism, homophobia, restric- tions on eligibility, no access to programs, barriers to access, withholding information, departmental silos, government jurisdictions, secretive/restricted commu- nications, rigid boundaries. Structural Entitlements, access to programs, transparent pathways to access, affirmative action, community capacity building, interdepartmental links, inter-govern- mental links, accountability, open channels of communication, options for change, flexibility. Source: Shookner (2002:5). and South Asia. It is because majority of their populations are finding that the remaining minority (sometimes called the ‘last 10 percent’, though it might be more or fewer based on the country), are a ‘hard to reach’ category, not responsive to gen- eral ‘pro-poor’ policies. In Bangladesh, there are approximately 23,000 NGOs (non-government organizations) working with a number of activities for these disadvantaged people in order to improve their socio-economic conditions including poverty alleviation. But it is counted that approximately 14 millions people are ultra poor who are excluded from NGO services. The Head Count Rate (HCR) of incidence of poverty is esti- mated using both upper and lower poverty lines in Bangladesh. The estimated HCR of incidence of poverty using upper pov- erty line declined from 58.8 per cent in 1991/92 to 40.0 percent in 2005 at national level and those using lower poverty line declined from 42.7 percent in 1991/92 to 25.5 per cent in 2005 at national level. Both estimated HCR declined in urban and rural areas respectively, except for those in urban areas during the period from 1995/96 to 2000. While the poverty rates have decreased rapidly due to the high economic growth, inequalities in the growth are observed as well. According to the Prelimi- nary Report on Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2005 (HIES, 2005), the inequality widened rapidly in the 1990s and the Gini coefficients have deteriorated from 0.388 in 1991/92 to 0.451 in 2000 for national level; from 0.364 to 0.393 for rural areas; and from 0.398 to 0.497 for urban areas. In terms of calorie intake, the incidence of poverty has im- proved in rural areas, but has worsened in urban areas. The number of population, which falls below a threshold calorie intake (2,122 kilocalories per person on a dairy basis), had de- creased by 4 per cent from 58.35 million in 1983/84 to 56 mil- lion in 2005. The number has decreased by 40 per cent from 30.22 million in 1983/84 to 18.7 million in 2005 if the dairy calorie intake per person of 1,805 kilocalories is applied. Fol- lowings are reasons of the widened inequalities. While rural areas achieved growth based on new income sources such as non-farm self-employment income, sala- ried wages and remittances from abroad in the 1990s, the extremely poor could not be benefited from those new income sources. Therefore, inequalities have increased in rural areas throughout the 1990s. In urban areas, the extremely poor are unable to fully ac- cess to new income sources such as non-farm self-em- ployment income, salaried wage, and remittances from abroad and rental value of housing. Further, nearly all an- tipoverty programs including human capital develop- ment. About 80 per cent of the total population lives in rural areas in Bangladesh and the incidence of poverty is overwhelmingly seen in rural areas. After the 1990s, the regional disparities became apparent between the areas, which benefited from the rapid high economic growth and those did not. The incidence of poverty is the highest in the Western areas including Rajshahi Division, following Khulna Division. Compared with Barisal and Rajshahi Divisions, the poverty reduction rates are higher in Dhaka, Chittagong and Sylhet Divisions. The rate of poverty has slightly increased in Khulna Division (Japan Bank for In- ternational Cooperation, 2007). In Bangladesh, the rural development is getting less priority for the last thirty years. In addition, as Curtin et al. (1997) ar- gues that ‘traditional rural development’ perspectives have generally taken for granted that rural poverty, in the sense of economic and social peripherality, is identical with or as a re- sult of geographical peripherality, and have sought intervene-  M. R. ISLAM ET AL. 39 tions that would make rural areas less marginal or less ‘spa- tially excluded. Due to natural disaster and geographical loca- tion many parts of the country are difficult to reach. Many N- GOs’ target population are such kind of disadvantaged and ultra-poor, but there are many causes which encourage such kind of exclusion of the NGOs’ activities. As a result, the num- ber of people in this group is increasing overtime. The DFID (2005) explains how the social exclusion leads to increase pov- erty in one hand and make obstacles in development on the other: Social Exclusion Causes the Poverty of Particular People, Leading to Higher Rates of Poverty among Affected Groups It hurts them materially – making them poor in terms of income, health or education by causing them to be denied access to resources, markets and public services. It can also hurt them emotionally, by shutting them out of the life of their community. Socially excluded people are often denied the opportuni- ties available to others to increase their income and escape from poverty by their own efforts. So, even though the economy may grow and general income levels may rise, excluded people are likely to be left behind, and make up an increasing proportion of those who remain in poverty. Social Exclusion Reduces the Productive Capacity – and Rate of Poverty Reduction of a Society as a Whole It impedes the efficient operation of market forces and restrains economic growth. Some people with good ideas may not be able to raise the capital to start up a business. Discrimination in the labour market may make parents de- cide it is not worthwhile to invest in their children’s edu- cation. Socially excluded groups often do participate but on un- equal terms. Labour markets illustrate this most clearly by exploiting the powerlessness of excluded groups and at the same time reinforcing their disadvantaged position. Social exclusion also increases the level of economic ine- quality in society, which reduces the poverty reducing im- pact of a given growth rate. Social Exclusion Makes It Harder to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals Social exclusion explains why some groups of people remain poorer than others, have less food, die younger, are less economically or politically involved, and are less likely to benefit from services. This makes it difficult to achieve the MDGs in some countries without particular strategies that directly tackle exclusion. Social Exclusion Leads to Conflict and Insecurity Social exclusion is a leading cause of conflict and insecu- rity in many parts of the world. Excluded groups that suf- fer from multiple disadvantages may come together when they have unequal rights, are denied a voice in political processes and feel marginalized from the mainstream of their society. Peaceful mobilization may be the first step, such as marches, strikes and demonstrations. But if this has no ef- fect, or if governments react violently to such protests, then groups are more likely to resort to violent conflict if they feel there is no alternative. When social groups feel unequal and suffer compared with others in society, conflict is more likely. Research over several decades has revealed that political and social forms of inequality are the most important factors in outbreaks of violence (particularly ethnic conflicts, revolutions and genocides). Social exclusion also causes insecurity in the form of gang violence. Young people who feel alienated from society and excluded from job opportunities and decision-making may turn to violence and crime as a way of feeling more powerful (DFID, 2005). Methods and Data This paper is based qualitative approach, which was influ- enced also by the ethnographic approach, considering different interacting social and cultural factors, such as people’s attitudes, norms, values and practices in their day to day life. The field work was carried out in the two communities from two NGOs: Proshika and Practical Action Bangladesh (PAB) and from two core projects such as the Markets and Livelihoods Program (MLP) (of PAB) and the Small Economic Enterprise Develop- ment (SEED) Program (of Proshika). One community was urban (Mirpur (1) Market for Proshika) in the capital Dhaka and another rural (Mostofapur Bazar (market) for PAB) in Madaripur district in Bangladesh and data were obtained from the two indigenous occupations: the goldsmiths and black- smiths respectively. The other stakeholders were NGO staff members and community leaders. A number of qualitative data collection methods such as participatory rural appraisal (PRA), social mapping, participant observation, in-depth study, focus group discussion (FGD) and documentation survey were em- ployed. The study uses twelve sets of research questionnaires/ guidelines and data were collected from forty two respondents (community people, local leaders and NGO staff members) of two NGOs and two communities. The data collection procedure was considered as a triangulation approach. Findings from the Two NGOs The exclusion of many poor people in program objectives is quite a common feature of NGO activities in Bangladesh. The realities of those, who were poor and marginalised, are often ignored or misread (Chambers, 2004:8). The notion of social exclusion focused on inadequate social participation, lack of social integration, and lack of power (Hunter, 2004:2). The NGOs’ conventional role towards development has been exten- sively debated. Bebbington (2005:937) notes that NGOs’ inter- ventions became biased toward the less poor. It is observed that the NGOs were concentrated in urban areas, where replication of their activities is frequent, but many of the bottom people are excluded from NGOs’ target. NGOs’ bureaucratic approach can not ensure a ‘sustainable community’; rather they further mar- ginalise many local people, such as blacksmiths and gold- smiths. The paper finds a number of elements of social exclusion, such as NGOs’ purposeful target group selection and repli- cation of program, short-term development approach versus impact of globalization, high-flying profile, rent seeking atti-  M. R. ISLAM ET AL. 40 tude, monolithic development approach, lack of accountability, complex loan procedure and high interest rate, and cut-off budget from social services (Figure 1). The major findings in term of social exclusion are shown as follows: Selection of Purposeful Target Groups and Replication of Program The field data confirms that micro-credit based NGO- Proshika, did not provide loan support to those goldsmiths, who were not guaranteed to re-pay such loans. As a result, many of the extreme poor remained beyond their services. Re- cent research has also criticised NGOs for lacking the capacity to involve the ‘ultra-poor’ (Rahman & Razzaque, 2000), and the poorest villages and neediest communities (Fruttero and Gauri, 2005:760). It was found that NGOs’ rigid practices kept away such vulnerable communities (Buckland, 2004:135 and 139). Proshika’s social and economic empowerment process usually side-lines the vulnerable population (Fatmi and Islam, 2001:253). One gold businessman said: “SEED selects the people to give loan support who are able to return their loan safely. I cannot find any difference between the normal bank and NGO bank. Both are same. But I think they should provide loan support to them who actually need it.” In addition to this, the replication of a program in a comm- nity had a strong negative effect on the flow of programs of the same sector or run by the same NGO. Short-Term Development Approach versus Impact of Globalization PAB worked with people’s existing employment rather than focusing support on new employment. Some NGO staff mem- bers, community leaders, and local producers raised questions about NGOs’ short-term development approach. This approach failed to sufficiently mobilise indigenous social and political capital that would build, or re-build, community capacity and Figure 1. Elements of social exclusion in NGOs’ activities.  M. R. ISLAM ET AL. 41 ensure sustainability of impact (Buckland, 1998:237). The NGOs also observed that the indigenous people, such as black- smiths and goldsmiths were suffering ‘minority’ and ‘isola tion’ problems, and their trust of NGOs was marginal. The local producers thought that, due to the expansion of large and sized industries through globalisation, they might disappear in the near future. The paper finds that there was a clear lack of con- fidence in their reluctance to face this global competition, as their education and quality of production were not sufficient. They were also afraid of the future, as they were not getting any kind of GOs’ and NGOs’ supports, and national and interna- tional networks towards their working capital, and modern tools and technologies. It was found that national and international involving technology-based firms were much stronger than local ones (Hendry et al., 2000). The finding of this paper is that, in the ‘winners and losers’ game of globalisation, more and more people were excluded from the benefits of this so-called progress of development. Only those who could sell their labour or services as a com- modity in an increasingly globalised economic system could survive; the majority who could not were left out (Tagicakibau, 2004:8). Local languages, oral histories and cultural traditions were also threatened (Holmes and Crossley, 2004:197). Equity and redistribution were increasingly recognised as the ‘missing link’. Devine (2003) found that the ‘ultra’ poor had been com- pletely marginalised in the NGO budgets in Bangladesh. It was not simply a lack of available resources; it was also fundamen- tally an issue of unequal power relations in which the poor were permanently marginalised and vulnerable, dependent as they were on local élites (Wood, 2003). High-Flying Profile Data found through reviewing policy documents confirm that both NGOs; policies were well written, and the NGOs had high-flying goals and objectives, and set out interesting pro- grams. The documents described how these would be achieved within the time framework. Notably, we gathered very good impressions from our meetings with the head office staff mem- bers in FGD sessions, who explained how they were helping the local producers. At this point, we would like to emphasise a couple of interesting arguments: the first is about their written ‘policy’, which was just ‘a policy by which they caught the attention of the donors’. However, there was a big ‘gap’ be- tween their written policy and real implementation at the field level. One Proshika staff member stated: “There is a gap between policy and implementation because of financial dependency. Most of the NGOs are project oriented. When final funding comes it is too small for the purposes, then the NGOs change their target and the donors again shorten their funding allocation during final allocation. Then the NGOs again shorten their project target.” Rent Seeking Attitude Many local producers and community leaders raised ques- tions about the ultimate controversial objectives of NGOs. A number of local producers and community leaders argued that the NGOs were ‘new money laundering’ agencies. They stated that the NGOs were using donations to ‘make money for them- selves’. Many said that they were confused, whether or not the NGOs used more than ten per cent of their resources at the field level, but they had expensive furniture, high salaries, and high consultancy fees and so on. Edwards (1999:367) found the same finding, when he reviewed the cost-effectiveness of two NGOs in Bangladesh because of high overheads (a large num- ber of staff and buildings). In this regard, Stubbs (2006:13) argues that the most active ‘high-profile NGOs’ are more con- cerned with personal gain rather than with the wider cause of poverty elimination. In addition, some NGO staff members’ attitudes were negative about their own value. They could not believe that their help would contribute a great deal of benefit for the local producers. This opinion was given by a field worker of PAB. Local producers also claimed that the staff members came to them just to take their kisti (instalment) and they gave them nothing, which eventually benefited them. Monolithic Development Approach Data gathered from different sources confirm that the NGOs’ development approach was ‘monolithic’. The MLP of PAB just provided training and advocacy, and SEED of Proshika mi- cro-enterprise loans, training, and advocacy. It has been argued that credit does not necessarily help the poor to accumulate assets, improve productivity, escape poverty and improve em- powerment (Nawaz, 2004:170). It is true that microfinance programs and institutions are increasingly important in devel- opment strategies, but knowledge about their impact is partial and contested (Hulme, 2000) and promotes lively debate (Si- manowitz, 2003:1). There were some other concerns within micro-finances, such as the distribution and usage. Nawaz (2004:170, 173 and 175) conducted a study in Comilla district in Bangladesh on the micro-finance clients of three NGOs: Grameen Bank, ASA and BRAC, and found that micro-credit did not reach two thirds of the households, and in particular did not reach to the bottom layer of extremely poor households. In addition to this, a significant amount of micro-credit was pro- vided to non-poor and non-targeted households. Importantly, the paper argues that micro-finance does not ‘automatically’ empower, just as with other interventions, such as formal edu- cation and political quotas that seek to bring about a radical structural transformation that true empowerment entails (Kabeer, 2005:4709). This approach can foster sustainable de- velopment if, and only if, it is integrated in a view of commu- nity development that links the social, economic and environ- mental dimensions (Vargas, 2001:11). Lack of Accountability The accountability of NGOs, particularly their ‘downward accountability’1 to their beneficiaries, affected NGOs’ effect- tiveness in the process of empowerment for the poor and mar- ginalised people in developing countries (Kilby, 2006:951) such as Bangladesh. This debate is well travelled, and much less concern is given to the NGO’s broad values and its effect. There was a considerable gap between ‘the talk and the walk’ (Keystone, 2006). This notion of accountability created practi- 1The question of downward accountability is sensitive to power issues and the word ‘beneficiaries’ is problematic in its own right. The term ‘downward’ reinforces the idea of power asymmetry. Mulgan (2003) and Kilby (2006:961) caution that the use of the term “downward” accountability can exaggerate the weakness of the beneficiary or client and so suppress the essential ingredient of authority inherent in the accountability relationship.  M. R. ISLAM ET AL. 42 cal knowledge gaps. While, in principle, donors generally as- signed a high value to it, in practice the ways in which they managed their grants and investments did not support it. Here, some areas such as common planning tools, reporting formats and information systems did not capture the quality of ac- countability in relationships between NGOs and their constitu- ents, nor did they actively enable learning and improvement (Keystone, 2006). It was seen in the findings that micro-credit demanded ‘a type and quality of relationship that actually lim- ited poor people’s room to manoeuvre’. Moreover, NGOs were replacing traditional informal credit sources (Davis, 2006: 12-13). Complex Loan Procedure and High Interest Rate Informal discussions with the local producers, who were nei- ther the members of SEED nor took a loan from any NGO, suggested that enterprises required larger amounts to be loaned, which the local NGOs found risky, and many of the local NGOs did not have the capacity to provide such enterprise de- velopment loans to the small enterprises. The government and private commercial banks also suffered from bureaucratic prac- tices and required collateral, which the small entrepreneurs in most cases were unable to provide (Chaudhury, 2006:64). In reviewing the conditions of a SEED loan, it was seen that the SEED provided loans on specific terms and conditions, which the goldsmiths found hard, complex and unaffordable. They calculated that, including all, the interest rate became up to thirty eight percent, which a producer had to pay from his first month of the instalment. It was also found from the list pro- vided by SEED (2006) that the flat rate of other NGOs (such as BRAC 15%, and MIDAS 16%), and other government and private banks (Janata Bank 12.5%, Agrani Bank 14%, and Prime Bank Ltd 15%) was comparatively low. The goldsmiths had serious problems formulating loan pro- cedures; for example, to complete nine pages of an application form with information on personal, business, property, business appraisal, and profit. SEED required ten types of documents, such as the original property or tenant agreement, two copies of a passport size photograph, letter (with two witnesses) and one copy of a passport size photograph from guarantor, citizenship certificate or two pages photocopy of passport, bank certificate mentioning current account of the business, photocopy of last month’s electricity bill, photocopy of last month’s rent payment receipt, photocopy of trade licence and two revenue stamps of Tk. 4, four non-judicial stamps of Tk. 150 (£1.36) each (two by the name of shop, one by the name of producer and one guar- antor). In many cases, the goldsmiths had difficulties to pro- duce such kind of documents. Cut-off Budget from Social Service Projects The paper argues that financial capital such as micro-credit is meaningless without the support of other services such as tech- nological support, management support, help to get access in the market, etc. The financial capital alone cannot build the social economy and develop communities; it has to be used in conjunction with other forms of capital, such as social, human, environmental and cultural capital (Kay, 2005:168). Recent literature has also shown that possessing physical and human capital is not in itself adequate to ensure project success (Nel et al., 2001:4). Even local knowledge alone was not enough any- where, but perhaps particularly in rural areas (Malecki, 1998:4). Both NGOs had limitations of resources as they could not provide additional support for local people, dependent upon their own assets, skills and enterprise. The findings found that the local producers had little capital, very limited access to credit, very little power in the market and rarely received sup- port from the formal institutions. Proshika’s social program, a small part of the budget, was the ‘glue’ that held community groups and the whole program together (Yildiz et al., 2003: v-vi). But recently the cuts in the social program of this NGO had been too deep. Compared to the first three years of Phase VI, the social programs had declined by 90 per cent for the training and health infrastructure components, and by 40 per- cent for universal education (Table 2). Table 2. Social component and achievement of Proshika. Social components Achievement First nine month compared to Annual Work Plan (2002-2003) Achievement compared to Phase VI targets (1999-2004) Organisational building Area expansion Low: 27% High: 139% for village/slum expansion Primary groups Low: 40% High: 86% Federations Very low: 6% to 28% Medium: 66% to 74% Training & popular theatre Human development Low 25% to 40% High: 53% to 144% Practical skills Low 13% to 37% Very low to very high: 22% to 128% Cultural programs Very low: 7% to 27% High: 81% to 99% Health Health training Medium to very high: 54% to over 500% High: 73% to over 300% Health infrastructure Very low to medium 13% to 51% Low to high: 15% to 100% Universal education NFP school & learners New schools: 0% High: 83% Adult literacy centres & learners New ALCs: 8% Medium: 56% to 61% Post literacy centres New PLCs: 0% Medium: 49% (first 4 years) Source: Yildiz et al., (2003: vi)  M. R. ISLAM ET AL. 43 It was found that the local producers were keen to participate in those projects, where their immediate financial benefits were obvious. The overall picture was that the local producers’ satis- faction level was comparatively poor with the long-term social development interventions. Allegedly, the NGOs neither gave advice, nor helped to link with other institutions, nor were they cooperative in linking with other people, such as business lead- ers, money lenders, and local administrators. In addition, some local producers argued that they had problems when they said that they were the client of a particular NGO. This situation was worse for SEED producers as they felt that the NGOs should link with the Government bank, where they had no access for loan facilities, though they were paying all kinds of taxes to the Government. The community leaders also added that the role of NGOs should be that of the ‘negotiator’. They also believed that their low amount of micro-enterprise loan would not be very helpful for their overall development without providing other supports. Conclusions The overalls assessment of the above discussion proves that NGOs’ social exclusion debate was extremely sharp, not only among community people such as blacksmiths and goldsmiths, but also among NGO staff members, community leaders, civil society, development thinkers, and policy makers. The NGOs’ conventional roles such as micro-credit business, target based approach, monolithic development approach, exclusion of the ‘ultra’ poor, work with existing employment rather creation new employment sectors, and downward accountability, were caught in this complex situation. However, the NGOs could not fulfil the demands of the marginal communities, such as black- smiths and goldsmiths because of their lack of services and lack of dedication to their services. In addition, their feeling of iso- lation was high in the competitive globalize markets. References Ahmad, Q. K. (2009). Key note address – Regional conference on inclusive development and climate justice in South Asia. Organized by Bangladesh Unnayan Parishad (BUP) under the auspices of Imagine a new South Asia, supported by ActionAid, Dhaka. Bank for International Cooperation (2007). Poverty profile People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Dhaka. Japan Bank for International Coop- eration. Bebbington, A. (2005). Donor–NGO Relations and representations of livelihood in non-governmental aid chains. World Development, 33, 937-950. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.09.017 Buckland, J. (1998). Social capital and sustainability of NGO inter- mediated development projects in Bangladesh. Community Devel- opment Journal, 33, 236-248. Buckland, J. (2004). Globalization, NGOs and civil society in Bang- ladesh. In J. L. Chodkiewicz and R. E. Wiest (Eds.), Globalization and community: Canadian perspectives. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. Bynner, J. (1998). Use of longitudinal data in the study of social exclu- sion. OECD: Centre for Educational Research and Innovation. http:// www.oecd.org/dataoecd/20/15/1856691.pdf. (Accessed: 11 October 2010). Chambers, R. (2004). Ideas for development: Reflecting Frwards’ IDS working paper 238. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. Chaudhury, I. A. (2006). Sustainable livelihoods through capacity building and enterprise development, documenting the evidence and lessons learned. Dhaka: Practical Action Bangladesh. Davis, J. K. (2006). NGOs and development in Bangladesh: Whose sustainability counts? Perth: Murdoch University. Devine, J. (2003). The paradox of sustainability: Reflections on NGOs in Bangladesh. Annals of the American Academy of Political and So- cial Science, 590, 227-242. DFID (2005). Girls’ education: Towards a better future for all. London: DFID. Edwards, M. (1999). NGO performance – What breeds success? New evidence from South Asia. World Development, 27, 361-374. Fatmi, M. N. E., & Islam, M. (2001). Towards a sustainable poverty forming model the proshika approach. In I. Sharif & G. Wood (Eds.), Challenges for second generation microfinance, regulations, su- pervision and resource mobilization. Dhaka: University Press Ltd.. Freiler, C. (2001). From experiences of exclusion to a vision of inclu- sion: What needs to change? Presentation for the CCSD/Laidlaw foundation conference on social inclusion. http://www.ccsd.ca/sub- sites/inclusion/bp/cf2.htm (Accessed: 10 October 2010). Fruttero, A., & Gauri, V. (2005). The strategic choices of NGO: Loca- tion in rural Bangladesh. The Journal of Development Studies, 41, 759-787. doi:10.1080/00220380500145289 Gauthier, M. (1995). L’exclusion, une notion récurrente au Québec mais peu utiliseée ailleurs en Amérique du Nord. Lien social et politiques - RIAC, 34, 151-156. Guildford, J. (2000). Making the case for social and economic inclu- sion. Population and Public Health Branch, Atlantic Region, Health Canada. http://www.hcsc.gc.ca/hppb/regions/atlantic/documents/index.html#s ocil (Accessed: 12 November 2010). Hendry, C., Brown J., & Defllippi, R. (2000). Regional clustering of high technology-based firms: Opto-electronics in three countries. Regional Studies, 34, 129-144. doi:10.1080/00343400050006050 Holmes, K., & Crossley, M. (2004). Whose knowledge, Whose values? The contribution of local knowledge to education policy processes: A case study of research development initiatives in the small state of Saint Lucia. Compare, 34, 193-208. doi:10.1080/0305792042000214010 Hulme, D. (2000). Protecting and strengthening social capital in order to produce desirable development outcome. Social Development Systems for Coordinated Poverty Eradication, SD Scope Paper No. 4. Bath: Centre for Development Studies, University of Bath. Hunter, B. (2004). Taming the social capital in hydra? Indigenous pov- erty, social capital theory and measurement. Discussion paper no. 261/2004 (Canberra, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Re- search, Australian National University). IDDC Paper (2009). Make development inclusive. http://www.make- development-inclusive.org/inclusivedevelopment.php?wid=1024&spk= en. Jackson, A. (2000). Why we don’t have to choose between social jus- tice and economic growth: The myth of the equity/efficiency trade- off. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development. Kabeer, N. (2005). Is microfinance a ‘magic bullet’ for women’s em- powerment? Analysis of findings from South Asia. Economic and Political Weekly, 29. Kabeer, N. (2006). Poverty, social exclusion and the MDGs: The chal- lenge of ‘durable inequalities’ in the Asian context. Background pa- per prepared for Asia 2015. Kay, A. (2005). Social capital, the social economy and community development. Community Development Journal, 41, 160-173. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsi045 Keystone (2006). Downward accountability to ‘beneficiaries’: NGO and donor perspectives. http://www.keystoneaccountability.org/files/ Keystone%20Survey%20Apr%2006%20Final%20Report.pdf (acce- ssed: 11 May 2008). Kilby, P. (2006). Accountability for empowerment: Dilemmas facing non-governmental organizations. World Development, 34, 951-963. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.11.009 Malecki, E. J. (1998). How development occurs: Local knowledge, social capital, and institutional embeddedness. Paper presented at the Meeting of the Southern Regional Science Association, Savannah.  M. R. ISLAM ET AL. 44 Maritime Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health (2000). Social and economic inclusion: Will our strategies take us there? Halifax. http://www.acewh.dal.ca/inclusion-preface.htm (Accessed: 114 November 2010). Mulgan, R. (2003). Holding power to account: accountability in mod- ern democracies. New York: Palgrave. Nawaz, S. (2004). An evaluation of micro-credit as a strategy to re- duce poverty: A case study of three micro-credit programs in Bang- ladesh. In: K. Jackson, N. Lewis, S. Adams, et al. (Eds.) Develop- ment on the edge (pp. 170-1175). The 4th Biennial Conference of the Aotearoa, New Zealand. Nel, E., Binns, T., & Motteux, N. (2001). Community-based devel- opment, non-governmental organizations and social capital in post- apartheid South Africa. Annaler Series B, Human Geography, 83, 3-13. Raphael, D. (2004). Social exclusion and health. Social Determinants of Health Listserv Bulletin, 3. Rahman, A., & Razzaque, A. (2000). On reaching the hardcore poor: Some evidence on social exclusion in NGO programmes. The Bang- ladesh Development Studies, 26, 1-35. Saloojee, A. (2001). Social inclusion, citizenship and diversity. Paper presented at CCSD/Laidlaw Foundation Conference on Social Inclu- sion. Shookner, M. (2002). An inclusion lens: Workbook for looking at so- cial and economic exclusion and inclusion. Population and Public Health Branch, Atlantic Region, Health Canada. Simanowitz, A. (2003). Appraising the poverty outreach of microfi- nance: A review of the cgap poverty assessment tool (PAT). Im- proving the Impacts of Microfinance on Poverty: Action Research Programme, 1, 1-7. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bistream/23743/1/ op030001.pdf (accessed: 1 August 2008). Stubbs, P. (2006). Community development in contemporary croatia: Globalization, neo-liberalisation and NGOI-isation. In L. Dominelli (Ed.), Revitalising communities in globalising World (pp. 161-174). London: Ashgate. Tagicakibau, E. G. (2004). Development-for whom in the pacific? Issues and challenges to globalization and human security at com- munity level. In K. Jackson, N. Lewis, S. Adams, et al. (Eds.) De- velopment on the Edge (pp. 7-12), The Fourth Biennial Conference of the Aotearoa, New Zealand. Vargas, C. M. (2001). Community development and micro-enterprises: Fostering sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 8, 11- 26. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1719(200002)8:1<11::AID-SD119>3.0.CO; 2-7 Wood, G. D. (2003). Staying secure, staying poor: The faustian bar- gain. World Development, 31, 455-473. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00213-9 Yildiz, N., Kassam, Y., Heel, C. V., et al. (2003). Annual Review 2003, Proshika Kendra, Phase-VI, Social Programme. Dhaka: Proshika.

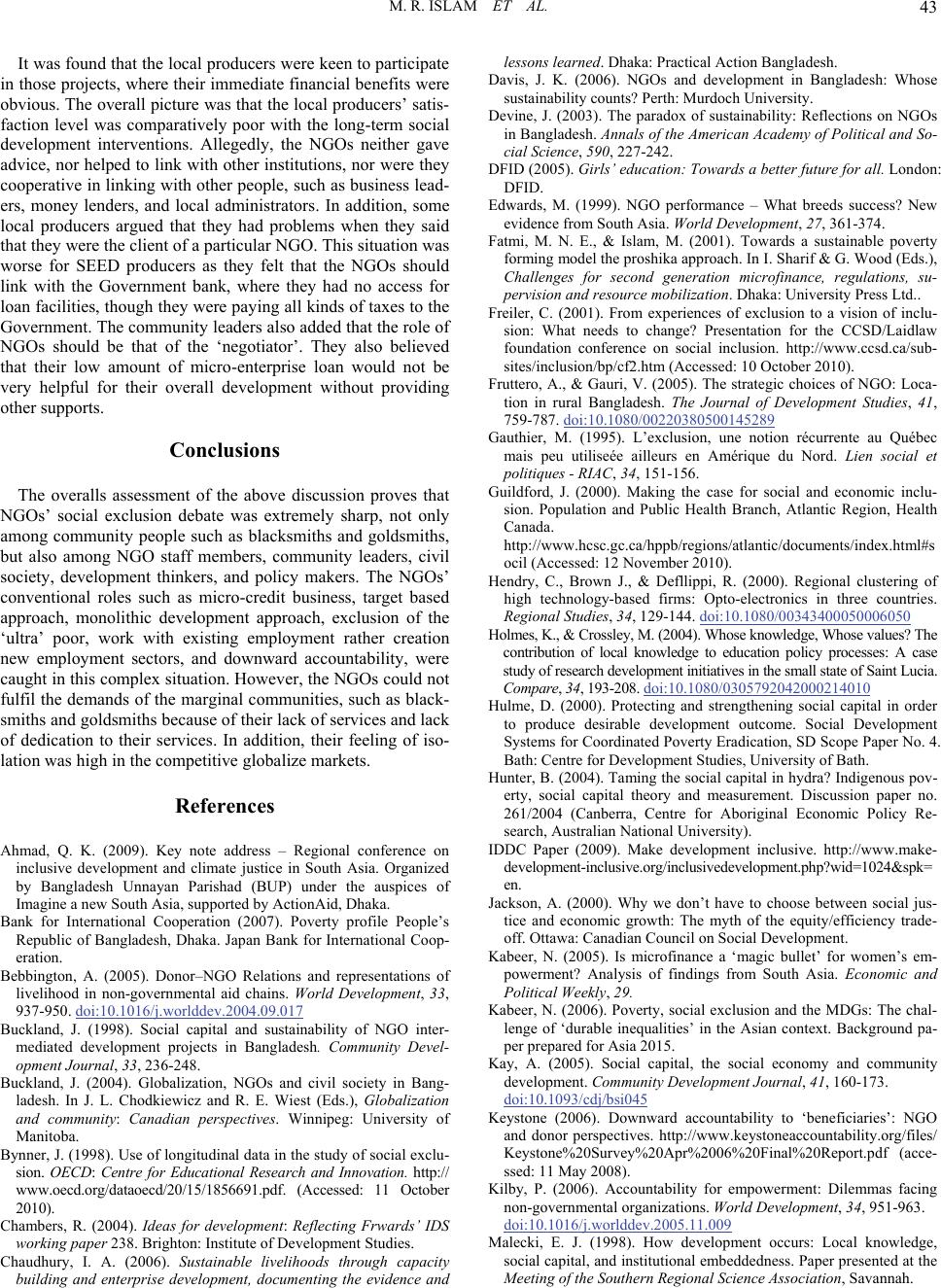

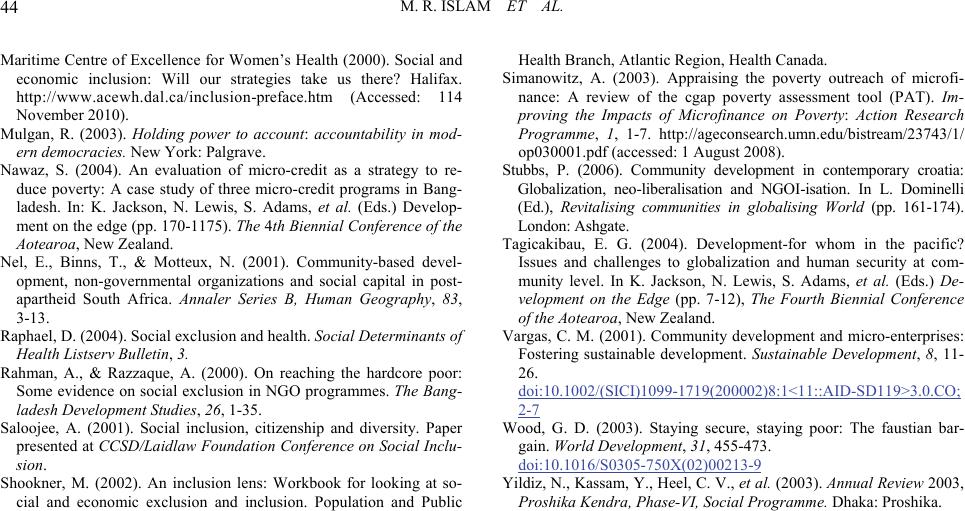

|