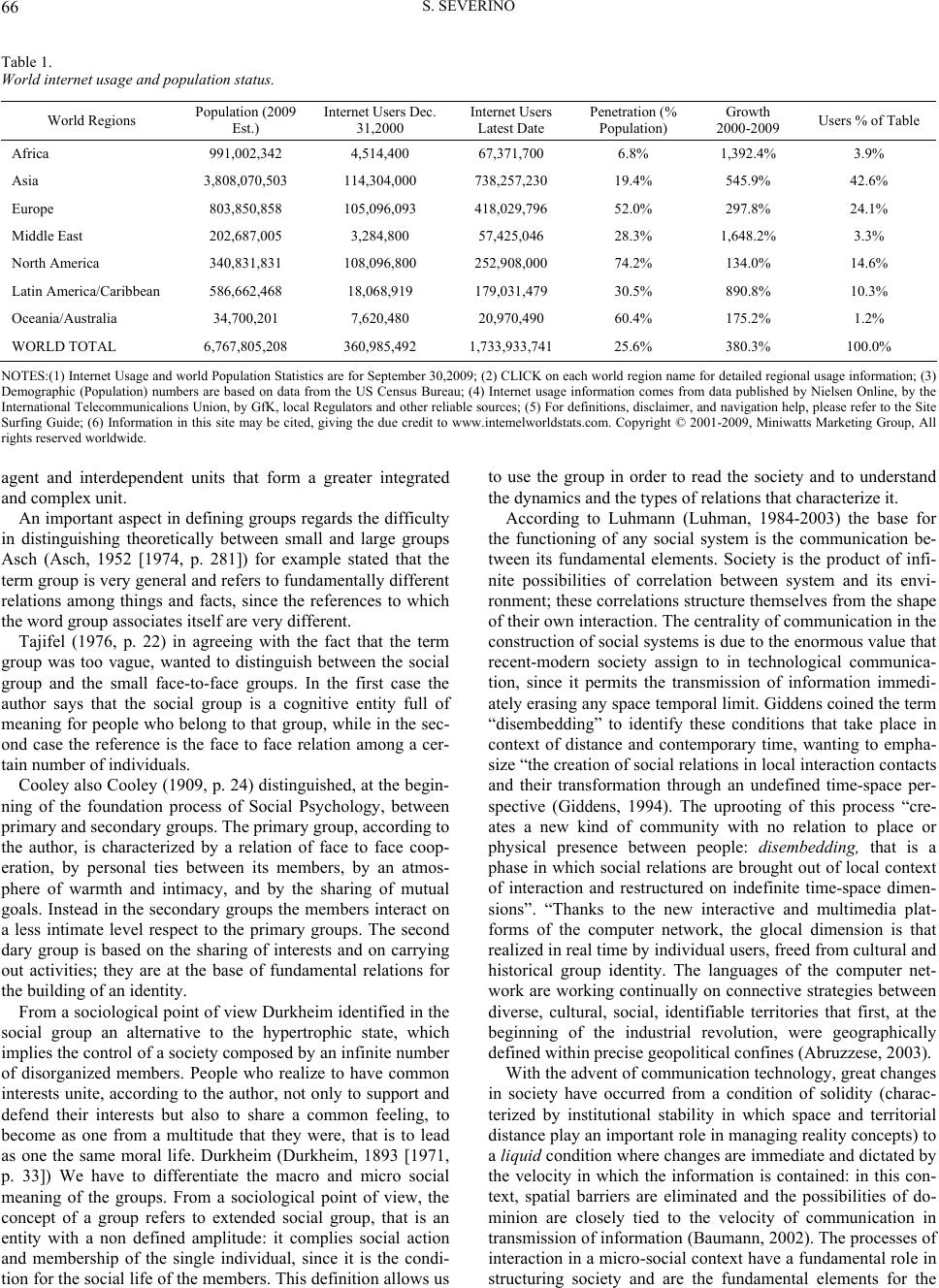

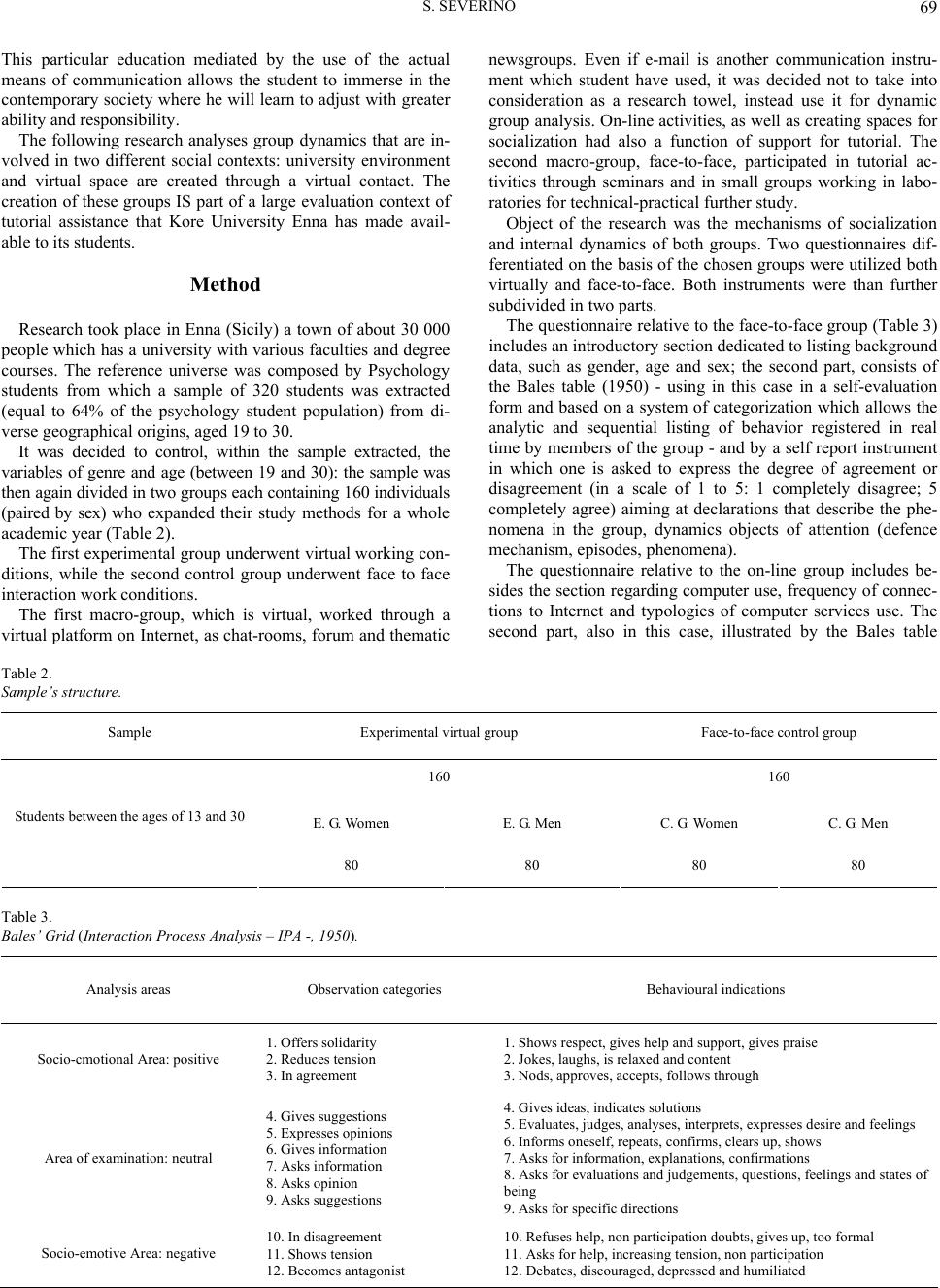

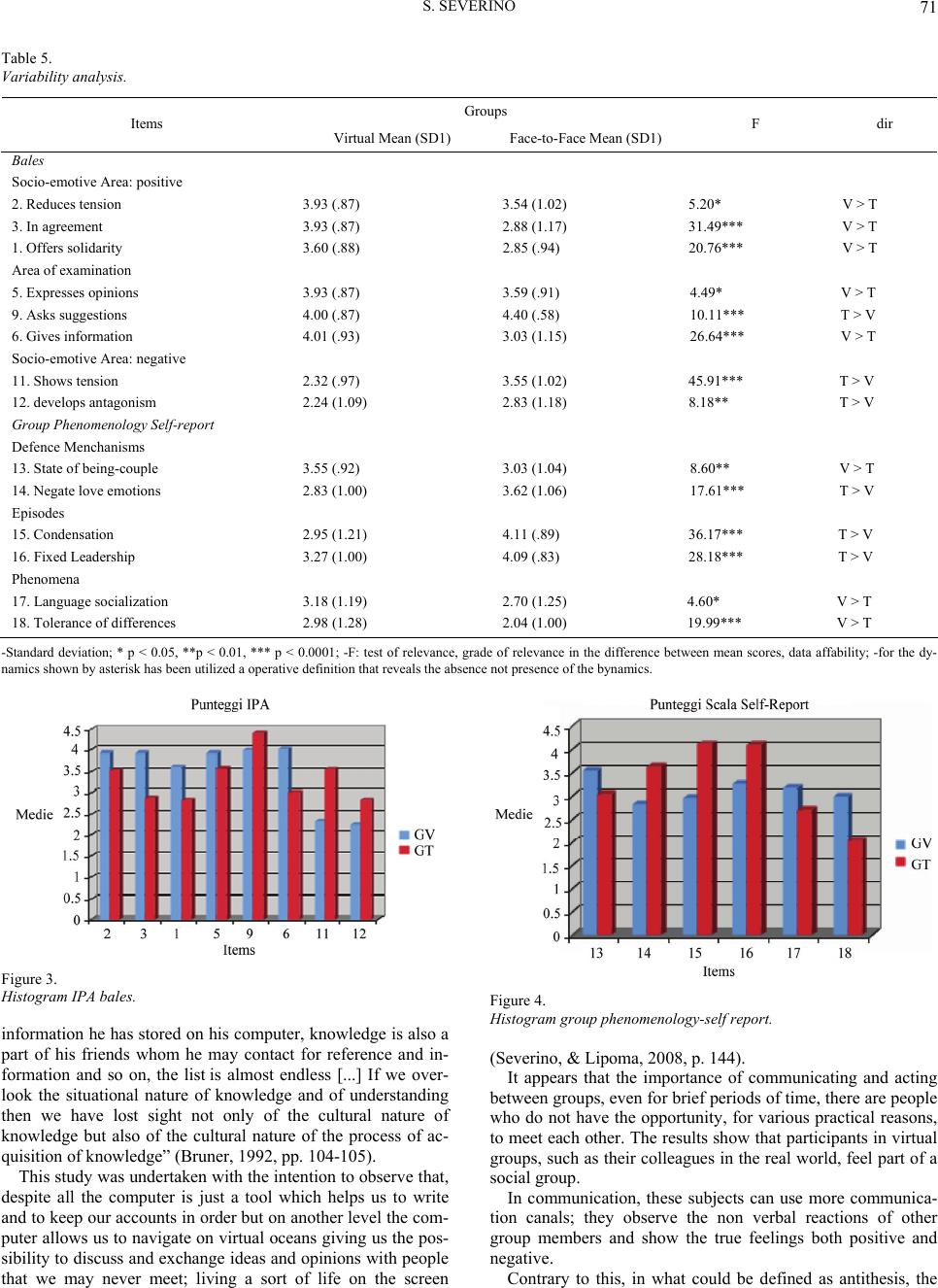

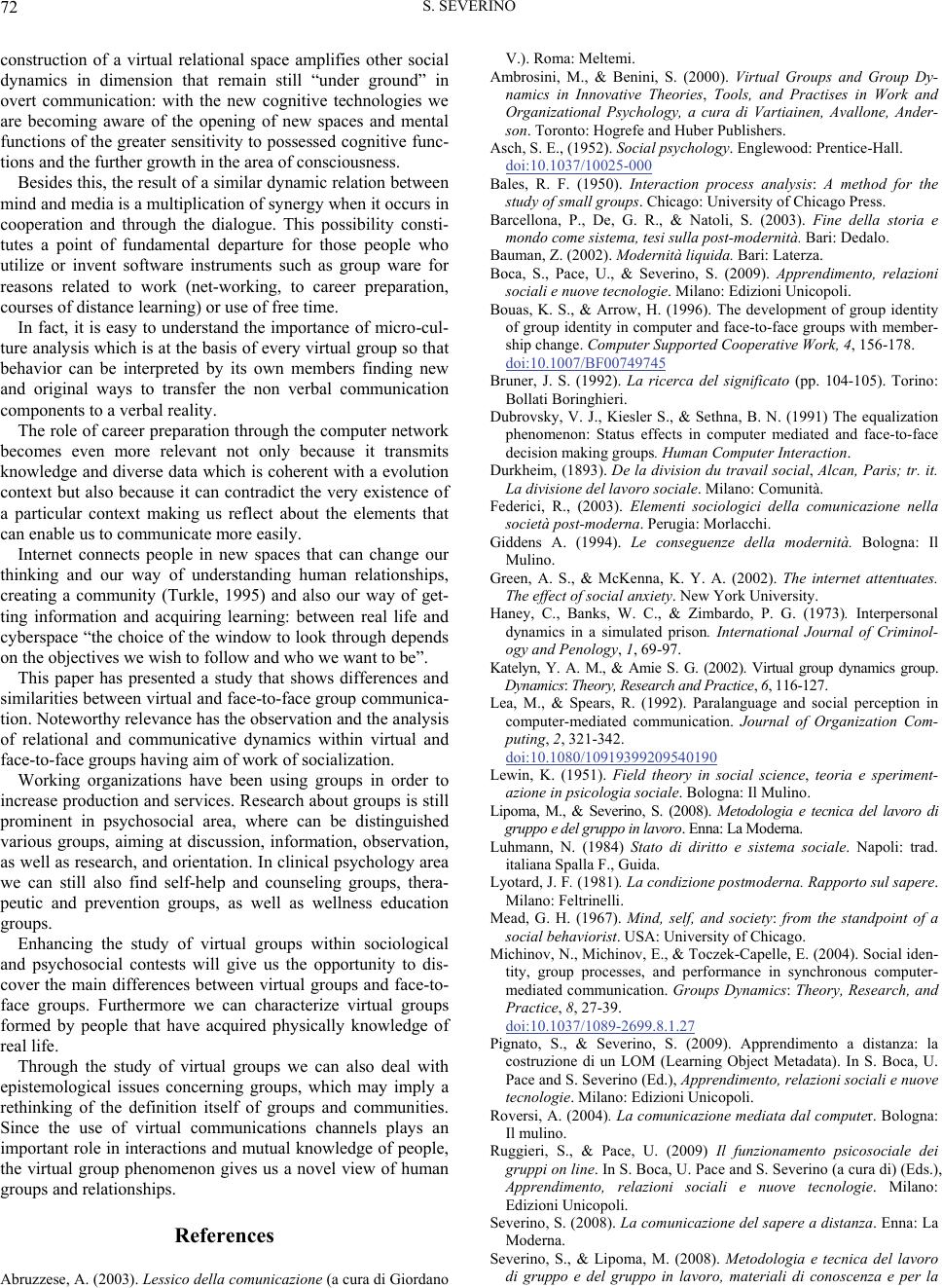

Sociology Mind 2011. Vol.1, No.2, 65-73 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/sm.2011.12008 Group Dynamics in On-Line and Face-to-Face Interactions: An Experimental Study on Learning Methods Sergio Severino, Roberta Messina University of Enna, Kore, Italy. Email: sergio.severino@unikore.it, messina.roberta@gmail.com Received February 2nd, 2011; revised February 21st, 2011; accepted March 2nd, 2011. Organizing in groups does not represent an objective definition, but rather a way to better understand the mean- ing of plurality. At the same time modern technologies modify perceptive and cognitive transformation. This re- search shows that on-line groups develop objective dynamics in face-to-face groups; it evaluates the quality of the University student services and studies the dynamics of the creation of face-to-face and on-line groups. Stu- dents were divided into experimental on-line (forum, chat, newsgroup) and face-to-face encounters (seminars, laboratories). The two level analyses show the defence mechanisms, the lack of socialization attitudes and the tolerance of differences that characterized on-line groups. The new technologies open new horizons and cogni- tive functions. Keywords: Face to face, Alternative Community, Post-modern, Group, Disembodying, Social-network. Introduction Internet users are currently accounting for 24.7% of the global population. From 2000 on, this figure has grown by 362.3% (www.internetworldstats.com, 2009), following a pro- gressive reinforcement in the relationship between information technologies and traditional processes of communication (see Table 1, Figure 1). Communication through computers travels in a parallel dimension to that of the traditional interactive face-to-face processes. When people use Internet to communicate or create relations with others, they are able to satisfy the same important personal and social needs that generally are welcomed through tradi- tional relationships: among these, for example, one can find the need to belong to a group. Belonging to a group, in fact, does not simply mean finding oneself at the same point of encounter: Turner (1982) believed that defining oneself as a part of a group is sufficient for determining ones unique existence. So- cial groups, in fact, do not represent an objective condition of socialization but rather an idea of social plurality; therefore the behavior of a person in a group derives from a synergy between its representation as a plurality and the two principle dimen- sions of identity: individual and social. The group is a very important part of human existence, since it represents the privileged context in which individuals grow, work, play and build their identities. Clearly the functional processes that distinguish the type of groups vary with the varying of the number of components. The behavior of each component varies according to the functional dynamics of the entire group. Lewin (1951) defined human behavior as a dynamic process determined by the interaction of forces present in the psycho- logical context, created by people and the environment; the following function illustrates its characteristics: B = f (E, P) where B is individual behavior, E the Environment and P the Person. This formula can be extended to group behavior: from the interaction between psychological areas of individuals who belong to the same life environment, one will obtain a unique social reference point whose dynamics derive from the interact- tion of the totality of groups and the external environment. The group (and its behavior) represents a dynamic totality whose endogenous and exterior factors appear to be tied to each other. This connection forms an organic system where every- thing intersects and refers uniquely to itself showing organiza- tion or structure according to a specific modality both con- sciously and unconsciously but no less important in a group level exchange. With the classical definition a group is something different- from the sum of its members: it has its own structure, its own particular goals and its own relations with the other groups. What makes the essence of a group is not the resemblance or non resemblance found among the members of a group, but the interdependence among its own members. Lewin points out that the group recognizes itself on the basis of the principle of interdependence and that therefore finishes with perceiving a certain group identity that gives meaning to the life of the group and reflects a subjective involvement which helps form one’s personality. The group can be assimilated to a system made up by inter Figure 1. World internet users by world regione.  S. SEVERINO 66 Table 1. World internet usage and population status. World Regions Population (2009 Est.) Internet Users Dec. 31,2000 Internet Users Latest Date Penetration (% Population) Growth 2000-2009 Users % of Table Africa 991,002,342 4,514,400 67,371,700 6.8% 1,392.4% 3.9% Asia 3,808,070,503 114,304,000 738,257,230 19.4% 545.9% 42.6% Europe 803,850,858 105,096,093 418,029,796 52.0% 297.8% 24.1% Middle East 202,687,005 3,284,800 57,425,046 28.3% 1,648.2% 3.3% North America 340,831,831 108,096,800 252,908,000 74.2% 134.0% 14.6% Latin America/Caribbean 586,662,468 18,068,919 179,031,479 30.5% 890.8% 10.3% Oceania/Australia 34,700,201 7,620,480 20,970,490 60.4% 175.2% 1.2% WORLD TOTAL 6,767,805,208 360,985,492 1,733,933,741 25.6% 380.3% 100.0% NOTES:(1) Internet Usage and world Population Statistics are for September 30,2009; (2) CLICK on each world region name for detailed regional usage information; (3) Demographic (Population) numbers are based on data from the US Census Bureau; (4) Internet usage information comes from data published by Nielsen Online, by the International Telecommunicalions Union, by GfK, local Regulators and other reliable sources; (5) For definitions, disclaimer, and navigation help, please refer to the Site Surfing Guide; (6) Information in this site may be cited, giving the due credit to www.intemelworldstats.com. Copyright © 2001-2009, Miniwatts Marketing Group, All rights reserved worldwide. agent and interdependent units that form a greater integrated and complex unit. An important aspect in defining groups regards the difficulty in distinguishing theoretically between small and large groups Asch (Asch, 1952 [1974, p. 281]) for example stated that the term group is very general and refers to fundamentally different relations among things and facts, since the references to which the word group associates itself are very different. Tajifel (1976, p. 22) in agreeing with the fact that the term group was too vague, wanted to distinguish between the social group and the small face-to-face groups. In the first case the author says that the social group is a cognitive entity full of meaning for people who belong to that group, while in the sec- ond case the reference is the face to face relation among a cer- tain number of individuals. Cooley also Cooley (1909, p. 24) distinguished, at the begin- ning of the foundation process of Social Psychology, between primary and secondary groups. The primary group, according to the author, is characterized by a relation of face to face coop- eration, by personal ties between its members, by an atmos- phere of warmth and intimacy, and by the sharing of mutual goals. Instead in the secondary groups the members interact on a less intimate level respect to the primary groups. The second dary group is based on the sharing of interests and on carrying out activities; they are at the base of fundamental relations for the building of an identity. From a sociological point of view Durkheim identified in the social group an alternative to the hypertrophic state, which implies the control of a society composed by an infinite number of disorganized members. People who realize to have common interests unite, according to the author, not only to support and defend their interests but also to share a common feeling, to become as one from a multitude that they were, that is to lead as one the same moral life. Durkheim (Durkheim, 1893 [1971, p. 33]) We have to differentiate the macro and micro social meaning of the groups. From a sociological point of view, the concept of a group refers to extended social group, that is an entity with a non defined amplitude: it complies social action and membership of the single individual, since it is the condi- tion for the social life of the members. This definition allows us to use the group in order to read the society and to understand the dynamics and the types of relations that characterize it. According to Luhmann (Luhman, 1984-2003) the base for the functioning of any social system is the communication be- tween its fundamental elements. Society is the product of infi- nite possibilities of correlation between system and its envi- ronment; these correlations structure themselves from the shape of their own interaction. The centrality of communication in the construction of social systems is due to the enormous value that recent-modern society assign to in technological communica- tion, since it permits the transmission of information immedi- ately erasing any space temporal limit. Giddens coined the term “disembedding” to identify these conditions that take place in context of distance and contemporary time, wanting to empha- size “the creation of social relations in local interaction contacts and their transformation through an undefined time-space per- spective (Giddens, 1994). The uprooting of this process “cre- ates a new kind of community with no relation to place or physical presence between people: disembedding, that is a phase in which social relations are brought out of local context of interaction and restructured on indefinite time-space dimen- sions”. “Thanks to the new interactive and multimedia plat- forms of the computer network, the glocal dimension is that realized in real time by individual users, freed from cultural and historical group identity. The languages of the computer net- work are working continually on connective strategies between diverse, cultural, social, identifiable territories that first, at the beginning of the industrial revolution, were geographically defined within precise geopolitical confines (Abruzzese, 2003). With the advent of communication technology, great changes in society have occurred from a condition of solidity (charac- terized by institutional stability in which space and territorial distance play an important role in managing reality concepts) to a liquid condition where changes are immediate and dictated by the velocity in which the information is contained: in this con- text, spatial barriers are eliminated and the possibilities of do- minion are closely tied to the velocity of communication in transmission of information (Baumann, 2002). The processes of interaction in a micro-social context have a fundamental role in structuring society and are the fundamental elements for the  S. SEVERINO 67 definition of group: the study of group dynamics through com- puter technology is absolutely essential for the comprehension of the flexibility of structural mechanism typical of contempo- rary reality (Federici, 2003). The ICT (Information and Com- munication Technology) is technology applied to information and communication and it is one of the inventions that in the last decades has revolutionized not only the communicational and informative processes but the educational ones as well. Through the application of this technology to training it is pos- sible to stimulate the cognitive elaboration (processes of acqui- sition, processing and consolidation of knowledge), stimulate meta-communicative skills and stimulate planning skills through the mental anticipation of the events. The structure of virtual groups is equivalent to that of face- to-face groups: in both cases one can define norms, roles, status processes of cohesion and feelings of group identity (Ruggieri, Pace, 2009). What divides these two social realities regards the environmental dimension in which they exist: if in the tradi- tional group, most face-to-face interaction is realized through a continuous exchange of information through a non verbal canal of communication, in the virtual groups analogical communica- tion is much less important because it is mediated through the use of an avatar, images and emoticon. The absence of physi- cality, therefore, influences the presentation of one’s personal identity, which is manipulated creating images of itself that are not necessarily corresponding to reality. Even if virtual groups have the same components of face-to-face groups, these elements work in different way. The absence of a physical presence and anonymity are elements capable of influencing the nature of the relations between members of groups on line, depriving them of the possibility to transmit information through the non verbal analogical dimen- sion of human communication. Research has shown in fact that the material aspects of the environment in which the face to face group interacts, the interpersonal distance and the position of the members all play a fundamental role in the structuring of the dynamics that govern it (Shaw, 1976). The internal relations in an on line group instead will be conditioned by specific ele- ments of the virtual environment such as the conversational style of the members or the resemblance of values and interests expressed during the conversations. Linked to the theme of anonymity is the management of per- sonal identity on the Internet: in the news groups, in the chat rooms and in the MUD (Multi User Dimension) individuals build Virtual Identities or representations of oneself which do not totally coincide with reality or which only give a small trace of the real situation. So users relate to their interlocutors after manipulating their physical moral and character image, often following different codes of social conduct: “they present them- selves as different people in a kind of consensual simulation; they amuse themselves in challenging, manipulating and alter- ing, disassembling and reassembling over and over the main pieces of their daily dimension and the regulations and rules that govern it so as to build a collective and imaginary dimen- sion totally different from the real one” (Roversi, 2004). The absence of a physical appearance and anonymity typical of CMC are at the base of the phenomenon called deindividua- tion, originally studied in relation to the function of large social groups where the elevated number of people contributes to reduce self awareness and to stimulate behavior non adherent to social standards. Anonymity and the perception of solitude felt by the web users during interaction through their computers produce a psychological state which loosens social pressures. It can bring, in extreme cases, towards behavior called flaming or the manifestation of open hostility and aggressiveness towards the individuals with whom they are interacting. This effect, according to LEA and SPEARS (1992) gets stronger as the sense of affiliation within the group gets weaker; in this case the negative effects of deindividuation are determined by the tendency of a user with a strong social identity to diminish the importance attributed to the group and to affirm his own ego through hostile behavior towards the other members. The re- duction of social pressures does not always produce negative effects: in many cases it may stimulate individuals to open up towards others in a larger measure respect to when they com- municate in a non anonymous condition. Anonymity facilitates the participation and the interaction within a group on the part of socially anxious individuals, too, that in virtual group context are not subject to all those situa- tions, which in real contexts cause social anxiety. Green and Mckenna (2002) have shown how anxious subjects in a group face-to-face condition show levels of social anxiety higher than those experimented by anxious subjects within virtual groups. These evidences contribute in explaining the phenomenon of “status equalization effect” (Dubrowky et al, 1991) which con- sists in the fairer participation on the part of all members of virtual groups thanks to the reduction of status differences: in face-to-face groups, in fact, the tendency on the part of low social status subjects to participate to a smaller extent than high status subjects, is remarkably reduced in respect to the virtual condition. Cohesion and status constitute a fundamental element in the structural factors of a group: some research has observed that “in less rich communication modes regarding the transferring of information the cohesion links will develop more slowly and with major difficulty than in the FTF contexts. Against this research other studies show that the cohesion processes of the group in virtual contexts are in reality simply slower to form” (Boca, Pace, & Severino, 2009). Anonymity and textual communication do not preclude the creation of a sense of belonging among the members of an on line group (Michinov, Michinov e Toczek, & Capelle, 2004), and neither the development of group standards nor adhesion to these standards by the participants are precluded (Bovas, Arrow, 1996; Finholt, & Sproull, 1990; Lea, Spears, & De Groot, 1998; Postmates, Spears, & Lea, 1999). “The position assumed re- spect to the group standards is closely related to the identity reference of the individuals. The results available to date show that if the participants are involved as members of a group the on line behavior could result more rigidly accordant to group standards than in non deindividuated situations” (Boca, Pace, & Severino, 2009). So identity has a social origin just as the intelligence of an individual. The importance of the group on the cognitive level is given by the possibility of identifying within the social, categories in which we can place ourselves and manage social relations. This way, social identity joins personal identity, which, in a group situation, as Zimbardo sustains (Zimbardo et al., 1979) is supported by a sort of anonymity given by the spread of the per- sonal responsibilities of ones own actions.  S. SEVERINO 68 Graphic composed by four areas, generated by the interaction between private dimension (face to face) and collective dimen- sion (social networking). I don’t know other ways where intelligence or mind can grow or be grown if not through the internal growth on the part of the individual through experience and behaviour through so- cial processes (Mead, 1967). Mead is convinced that the indi- vidual behaves on the basis of the principle for which a stimu- lus coming from the environment creates the right reaction: in particular in the case of human being, between a stimulus and its reaction is created a symbol, which is coordinated with one’s personal orientation of behavior. The “self” and the “mind”, far from being innate rather are developed in the effort to adapt (themselves) to (their) environment. The capacity to interpret gestures and behavior is the capac- ity to take the role of the other. Without this capacity, it would be impossible to co-operate with others that characterizes every society. Besides this, this capacity implies that the individual considers himself also from the point of view of the other: in this way, you can better evaluate the consequences of one’s behavior compared to another’s. According to Mead, one of the peculiarities of human race is that of making of one’s self an object of representation. The different impressions that are formed from different situations in which we interact with others and in different context (in- cluding on-line) converge in a context which is more or less coherent with our “self”. In this way, individuals acquire the perspective of a community of attitudes, thanks to which they cooperate with different people in different environments em- pathize with them. Society is nothing but an organized interact- tion among individuals: it is far from being a casual cones- quence; it is rather coordinated and it needs the “mind” since one could not coordinate one’s actions without assuming roles and other possibilities of action. The subject is not only a sim- ple consciousness blocking external influences: next to the conscious state of “I” there is also “Me”, which means the con- ception that others have of me, so it is the process of internali- zation of what others expect of me. The idea of Mead is that we are what others want us to be; facing other people, the subject will develop an articulate vision of “Me” that is synthesized in a coherent context. Only when such synthesis is successful can the “self” be created, that is the personal identity as a structural unit orientated towards cooperation. So understood, the “self” is the synthesis in a fine balance of different “Me’s” (see Figure 2). Figure 2. Severino’s flowchart. As recent research shows, the material elements of group set- tings (like the interpersonal distance in a group) play a very important role in the construction of internal dynamics. In the same way, internal relations in on-line groups are influenced by specific factors from a virtual environment, as for example the conversational style of group members and their similarities to values and interests shown during conversation (Lipoma, & Severino, 2008). By the original Lewin’s formula B=f E,P the psycho- logical field is a sum of interdependent psychological facts: the first one is the subject’s space life (P), which is based on the subject’s representation of the world; the second category of facts (E) is social and/or environmental, including any physical and social process that influences the internal subject’s world. Furthermore Lewin theorizes a borderline, which represents the boundary between the subjective representation of the world and the real or substantial (physical and social) world. Accord- ingly, the psychological field is the results of the interaction between the subjective dimension and the external dimension. In fact this interaction regulates individual behavior. If Lewin formula is transposed to a virtual context, it can be observed that a person’s behavior is the function of the interact- tion between virtual environment and individual characteristics, as indicated in the following formula: f, VV V iE ergoBEP where B is the individual’s behavior in the virtual group, E is the virtual environment and P is the individual. The behavior of the individual in a virtual group (BV) is regulated by the interaction of psychological facts (EV, P) de- scribed by the original formula. Virtual identity, anonymity, as well as the absence of the physical interaction and the absence of a verbal communicational channel (replaced with avatar, image and emoticon) are determining factors that characterize interaction precesses within virtual groups against interaction processes within face-to-face groups. Another relevant effect of being anonymous and lacking physical presence is the reduction of one’s understanding of oneself that implicates a lessening of social pressures. Even if this process in some cases leads to a flaming effect (that con- sists of an aggressive mode of expression and hostility towards other users in the virtual world) (Ruggieri, & Pace, 2009); in other cases, it can facilitate social interactions above all in the case of anxious individuals; Green and McKenna (2002) have observed, in fact, that the socially anxious subjects show higher level of anxiety in face-to-face group respects to what occurs in virtual group settings. This difference is defined as Status Equalization Effect (Ruggieri, & Pace, 2009) that is the condition of reduced status difference between virtual groups. In our research, the effect of the process of reduction in the difference of status seems to be at the origin of the activation of positive behavior dynamics seen in greater measure in virtual groups rather that those that are traditional. The use of virtual groups in learning fields represents there- fore a fine opportunity for development in the education and formative paths in the world (Pignato, & Severino, 2009). In a virtual group, the student is protagonist of his own learning process during which he can communicate and interact with teachers and other students without temporal limitation in a hierarchical direction (teacher/student) and between equals.  S. SEVERINO 69 This particular education mediated by the use of the actual means of communication allows the student to immerse in the contemporary society where he will learn to adjust with greater ability and responsibility. The following research analyses group dynamics that are in- volved in two different social contexts: university environment and virtual space are created through a virtual contact. The creation of these groups IS part of a large evaluation context of tutorial assistance that Kore University Enna has made avail- able to its students. Method Research took place in Enna (Sicily) a town of about 30 000 people which has a university with various faculties and degree courses. The reference universe was composed by Psychology students from which a sample of 320 students was extracted (equal to 64% of the psychology student population) from di- verse geographical origins, aged 19 to 30. It was decided to control, within the sample extracted, the variables of genre and age (between 19 and 30): the sample was then again divided in two groups each containing 160 individuals (paired by sex) who expanded their study methods for a whole academic year (Table 2). The first experimental group underwent virtual working con- ditions, while the second control group underwent face to face interaction work conditions. The first macro-group, which is virtual, worked through a virtual platform on Internet, as chat-rooms, forum and thematic newsgroups. Even if e-mail is another communication instru- ment which student have used, it was decided not to take into consideration as a research towel, instead use it for dynamic group analysis. On-line activities, as well as creating spaces for socialization had also a function of support for tutorial. The second macro-group, face-to-face, participated in tutorial ac- tivities through seminars and in small groups working in labo- ratories for technical-practical further study. Object of the research was the mechanisms of socialization and internal dynamics of both groups. Two questionnaires dif- ferentiated on the basis of the chosen groups were utilized both virtually and face-to-face. Both instruments were than further subdivided in two parts. The questionnaire relative to the face-to-face group (Table 3) includes an introductory section dedicated to listing background data, such as gender, age and sex; the second part, consists of the Bales table (1950) - using in this case in a self-evaluation form and based on a system of categorization which allows the analytic and sequential listing of behavior registered in real time by members of the group - and by a self report instrument in which one is asked to express the degree of agreement or disagreement (in a scale of 1 to 5: 1 completely disagree; 5 completely agree) aiming at declarations that describe the phe- nomena in the group, dynamics objects of attention (defence mechanism, episodes, phenomena). The questionnaire relative to the on-line group includes be- sides the section regarding computer use, frequency of connec- tions to Internet and typologies of computer services use. The second part, also in this case, illustrated by the Bales table Table 2. Sample’s structure. Sample Experimental virtual group Face-to-face control group 160 160 E. G. Women E. G. Men C. G. Women C. G. Men Students between the ages of 13 and 30 80 80 80 80 Table 3. Bales’ Grid (Interaction Process Analysis – IPA -, 1950). Analysis areas Observation categories Behavioural indications Socio-cmotional Area: positive 1. Offers solidarity 2. Reduces tension 3. In agreement 1. Shows respect, gives help and support, gives praise 2. Jokes, laughs, is relaxed and content 3. Nods, approves, accepts, follows through Area of examination: neutral 4. Gives suggestions 5. Expresses opinions 6. Gives information 7. Asks information 8. Asks opinion 9. Asks suggestions 4. Gives ideas, indicates solutions 5. Evaluates, judges, analyses, interprets, expresses desire and feelings 6. Informs oneself, repeats, confirms, clears up, shows 7. Asks for information, explanations, confirmations 8. Asks for evaluations and judgements, questions, feelings and states of being 9. Asks for specific directions Socio-emotive Area: negative 10. In disagreement 11. Shows tension 12. Becomes antagonist 10. Refuses help, non participation doubts, gives up, too formal 11. Asks for help, increasing tension, non participation 12. Debates, discouraged, depressed and humiliated  S. SEVERINO 70 (1950) used in a self-correction form, has been adapted as computer language for web users (Table 4); besides, self-report section dealing with group phenomenology is present. The SPSS Statistical Software Package for Social Sciences has been used to make quantitative analysis of data, applying analysis of the scores obtained from the questionnaires. This one-way analysis has been applied to scores from the Bales’ table while the two-way analysis has allowed us to show the difference between dynamics revealed in the two groups (experimental/on-line and check/face-to-face). Findings and Results A one-way analysis (Table 5) applied to the data has shown the existence of significant statistical differences between the on-line and face-to-face group dynamics. The items referring to these three Bales IPA areas were grouped in different index; the application of ANOVA in these new variables has produced interesting results: behavior regarding the positive social emo- tional area were indicated in a greater measure in virtual group members; this result is a positive effect of the reduction of the status of virtual group members who are involved in internal behavioral dynamics. These results are coherent with the ten- dency by face-to-face groups to show behavior included a negative social-emotive context. The results of behavior in the Task Area (Neutral) show that in two or three cases the com- ponents of the virtual group are more involved than members of the face-to-face group. This area includes functional behavior aimed at the comprehension of the situation and resolution of the problems. The interviewed subjects showed the activation of defense mechanisms, episodes and phenomena in both groups; the three elements are indicators of development of group dynamics. These results confirm early research conducted on newsgroups (Ambrosini, Bernardi, & Bernini, 2000). The differences regard mechanisms of defense from “cou- pling up” (p < 0.01) “escape from love” (p < 0.001), episodes of “condensation” (p < 0.001) and “permanent leadership” (p < 0.001) and two group phenomena of “language socialization” (p < 0.05) and “tolerance of differences” (p < 0.001) (Table 5). In particular, defense mechanism have been seen in both groups (coupling in virtual groups avoiding love relationships in face- to-face groups); the episodes (condensation and permanent leadership) seem to regard above all groups in traditional inter- action; the absence of language socialization regards the virtual group, while it is significantly present tolerance for differences (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Conclusions and Recommendations Today every aspect of human life is intrinsically linked to the new possibilities which ICT offers. Communication which can take place regardless of physical or temporal distances and the building of a body of knowledge based on endless communica- tion possibilities are just some of the fundamental aspects of the continuous dynamics of change in society. Training and educa- tional processes also change at great speed through the use of new technology. McLuhan was the first, more than forty years ago (indeed, drawing much from Vygotskij’s opinions) to un- -derline the influence that the new technologies would have had not only on the way of communicating but also on the devel- opment of the human mind and on collective culture which is the product of the new ways of interacting between individuals. Virtual experience allow us to reach certain dimensions of thought of training and of learning that were unthinkable just a few decades ago; the diffusion of fast connections furthermore, has determined the passage from the conception of the WEB as a static container of information from which to draw towards a reality in continuous transformation where knowledge adds to knowledge and is transformed thanks to the flow of the context in which this knowledge is produced. A person’s knowledge is not only in his mind in a solo form, it is in the notes which he takes and refers to, in the underlined books that he has in his bookshelves, in the manuals he has learned to consult, in the Table 4. Bales’s grid (interaction process analysis – IPA -, 1950), adapted for web language users. Analysis areas Observation categories Behavioural indications Socio-motional Area: positive 1. Offers solidarity 2. Reduces tension 3. In agreement 1. Shows respect, gives help and support, praise through textual language, funny faces, appropriate images 2. Jokes, uses funny faces and images that express a positive attitude (encouraging smiles) 3. Nods, approves, accepts through textual and funny face language Area of examination: neu- tral 4. Gives suggestions 5. Expresses opinions 6. Gives information 7. Asks information 8. Asks opinions 9. Asks suggestions 4. Gives ideas, indicates solutions through textual “question language” 5. Evaluates, judges, analyses, interprets, expresses desires and feelings through tex- tual, image, funny face and “question language” 6. Informs, repeats, confirms, clarifies, illustrates through post, new topic and a link insertion 7. Asks for information, explanations, confirms through, post or new topic, openness to new topics 8. Asks evaluations and judgements and questions, sentiments and states of the mind through post or openness to new topics 9. Asks directions through post or new topics Socio-emotive Area: nega- tive 10. In disagreement 11. Shows tension 12. Develops antagonism 10. Refuses help, is absent, doubts, gives up or reveals formalistic analysis through language and use of emotion 11. Asks help, uses funny faces that express negative attitudes, is absent 12. Argues, is discouraged, is depressed and humiliated through textual language, the use of emotion and images  S. SEVERINO 71 Table 5. Variability analysis. Groups Items Virtual Mean (SD1) Face-to-Face Mean (SD1) F dir Bales Socio-emotive Area: positive 2. Reduces tension 3.93 (.87) 3.54 (1.02) 5.20* V > T 3. In agreement 3.93 (.87) 2.88 (1.17) 31.49*** V > T 1. Offers solidarity 3.60 (.88) 2.85 (.94) 20.76*** V > T Area of examination 5. Expresses opinions 3.93 (.87) 3.59 (.91) 4.49* V > T 9. Asks suggestions 4.00 (.87) 4.40 (.58) 10.11*** T > V 6. Gives information 4.01 (.93) 3.03 (1.15) 26.64*** V > T Socio-emotive Area: negative 11. Shows tension 2.32 (.97) 3.55 (1.02) 45.91*** T > V 12. develops antagonism 2.24 (1.09) 2.83 (1.18) 8.18** T > V Group Phenomenology Self-report Defence Menchanisms 13. State of being-couple 3.55 (.92) 3.03 (1.04) 8.60** V > T 14. Negate love emotions 2.83 (1.00) 3.62 (1.06) 17.61*** T > V Episodes 15. Condensation 2.95 (1.21) 4.11 (.89) 36.17*** T > V 16. Fixed Leadership 3.27 (1.00) 4.09 (.83) 28.18*** T > V Phenomena 17. Language socialization 3.18 (1.19) 2.70 (1.25) 4.60* V > T 18. Tolerance of differences 2.98 (1.28) 2.04 (1.00) 19.99*** V > T -Standard deviation; * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.0001; -F: test of relevance, grade of relevance in the difference between mean scores, data affability; -for the dy- namics shown by asterisk has been utilized a operative definition that reveals the absence not presence of the bynamics. Figure 3. Histogram IPA bales. information he has stored on his computer, knowledge is also a part of his friends whom he may contact for reference and in- formation and so on, the list is almost endless [...] If we over- look the situational nature of knowledge and of understanding then we have lost sight not only of the cultural nature of knowledge but also of the cultural nature of the process of ac- quisition of knowledge” (Bruner, 1992, pp. 104-105). This study was undertaken with the intention to observe that, despite all the computer is just a tool which helps us to write and to keep our accounts in order but on another level the com- puter allows us to navigate on virtual oceans giving us the pos- sibility to discuss and exchange ideas and opinions with people that we may never meet; living a sort of life on the screen Figure 4. Histogram group phenomenology-self report. (Severino, & Lipoma, 2008, p. 144). It appears that the importance of communicating and acting between groups, even for brief periods of time, there are people who do not have the opportunity, for various practical reasons, to meet each other. The results show that participants in virtual groups, such as their colleagues in the real world, feel part of a social group. In communication, these subjects can use more communica- tion canals; they observe the non verbal reactions of other group members and show the true feelings both positive and negative. Contrary to this, in what could be defined as antithesis, the  S. SEVERINO 72 construction of a virtual relational space amplifies other social dynamics in dimension that remain still “under ground” in overt communication: with the new cognitive technologies we are becoming aware of the opening of new spaces and mental functions of the greater sensitivity to possessed cognitive func- tions and the further growth in the area of consciousness. Besides this, the result of a similar dynamic relation between mind and media is a multiplication of synergy when it occurs in cooperation and through the dialogue. This possibility consti- tutes a point of fundamental departure for those people who utilize or invent software instruments such as group ware for reasons related to work (net-working, to career preparation, courses of distance learning) or use of free time. In fact, it is easy to understand the importance of micro-cul- ture analysis which is at the basis of every virtual group so that behavior can be interpreted by its own members finding new and original ways to transfer the non verbal communication components to a verbal reality. The role of career preparation through the computer network becomes even more relevant not only because it transmits knowledge and diverse data which is coherent with a evolution context but also because it can contradict the very existence of a particular context making us reflect about the elements that can enable us to communicate more easily. Internet connects people in new spaces that can change our thinking and our way of understanding human relationships, creating a community (Turkle, 1995) and also our way of get- ting information and acquiring learning: between real life and cyberspace “the choice of the window to look through depends on the objectives we wish to follow and who we want to be”. This paper has presented a study that shows differences and similarities between virtual and face-to-face group communica- tion. Noteworthy relevance has the observation and the analysis of relational and communicative dynamics within virtual and face-to-face groups having aim of work of socialization. Working organizations have been using groups in order to increase production and services. Research about groups is still prominent in psychosocial area, where can be distinguished various groups, aiming at discussion, information, observation, as well as research, and orientation. In clinical psychology area we can still also find self-help and counseling groups, thera- peutic and prevention groups, as well as wellness education groups. Enhancing the study of virtual groups within sociological and psychosocial contests will give us the opportunity to dis- cover the main differences between virtual groups and face-to- face groups. Furthermore we can characterize virtual groups formed by people that have acquired physically knowledge of real life. Through the study of virtual groups we can also deal with epistemological issues concerning groups, which may imply a rethinking of the definition itself of groups and communities. Since the use of virtual communications channels plays an important role in interactions and mutual knowledge of people, the virtual group phenomenon gives us a novel view of human groups and relationships. References Abruzzese, A. (2003). Lessico della comunicazione (a cura di Giordano V.). Roma: Meltemi. Ambrosini, M., & Benini, S. (2000). Virtual Groups and Group Dy- namics in Innovative Theories, Tools, and Practises in Work and Organizational Psychology, a cura di Vartiainen, Avallone, Ander- son. Toronto: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers. Asch, S. E., (1952). Social psychology. Englewood: Prentice-Hall. doi:10.1037/10025-000 Bales, R. F. (1950). Interaction process analysis: A method for the study of small groups. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Barcellona, P., De, G. R., & Natoli, S. (2003). Fine della storia e mondo come sistema, tesi sulla post-modernità. Bari: Dedalo. Bauman, Z. (2002). Modernità liquida. Bari: Laterza. Boca, S., Pace, U., & Severino, S. (2009). Apprendimento, relazioni sociali e nuove tecnologie. Milano: Edizioni Unicopoli. Bouas, K. S., & Arrow, H. (1996). The development of group identity of group identity in computer and face-to-face groups with member- ship change. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 4, 156-178. doi:10.1007/BF00749745 Bruner, J. S. (1992). La ricerca del significato (pp. 104-105). Torino: Bollati Boringhieri. Dubrovsky, V. J., Kiesler S., & Sethna, B. N. (1991) The equalization phenomenon: Status effects in computer mediated and face-to-face decision making groups. Human Computer Interaction. Durkheim, (1893). De la division du travail social, Alcan, Paris; tr. it. La divisione del lavoro sociale. Milano: Comunità. Federici, R., (2003). Elementi sociologici della comunicazione nella società post-moderna. Perugia: Morlacchi. Giddens A. (1994). Le conseguenze della modernità. Bologna: Il Mulino. Green, A. S., & McKenna, K. Y. A. (2002). The internet attentuates. The effect of social anxiety. New York University. Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison. International Journal of Criminol- ogy and Penology, 1, 69-97. Katelyn, Y. A. M., & Amie S. G. (2002). Virtual group dynamics group. Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice, 6, 116-127. Lea, M., & Spears, R. (1992). Paralanguage and social perception in computer-mediated communication. Journal of Organization Com- puting, 2, 321-342. doi:10.1080/10919399209540190 Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science, teoria e speriment- azione in psicologia sociale. Bologna: Il Mulino. Lipoma, M., & Severino, S. (2008). Metodologia e tecnica del lavoro di gruppo e del gruppo in lavoro. Enna: La Moderna. Luhmann, N. (1984) Stato di diritto e sistema sociale. Napoli: trad. italiana Spalla F., Guida. Lyotard, J. F. (1981). La condizione postmoderna. Rapporto sul sapere. Milano: Feltrinelli. Mead, G. H. (1967). Mind, self, and society: from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. USA: University of Chicago. Michinov, N., Michinov, E., & Toczek-Capelle, E. (2004). Social iden- tity, group processes, and performance in synchronous computer- mediated communication. Groups Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 8, 27-39. doi:10.1037/1089-2699.8.1.27 Pignato, S., & Severino, S. (2009). Apprendimento a distanza: la costruzione di un LOM (Learning Object Metadata). In S. Boca, U. Pace and S. Severino (Ed.), Apprendimento, relazioni sociali e nuove tecnologie. Milano: Edizioni Unicopoli. Roversi, A. (2004). La comunicazione mediata dal computer. Bologna: Il mulino. Ruggieri, S., & Pace, U. (2009) Il funzionamento psicosociale dei gruppi on line. In S. Boca, U. Pace and S. Severino (a cura di) (Eds.), Apprendimento, relazioni sociali e nuove tecnologie. Milano: Edizioni Unicopoli. Severino, S. (2008). La comunicazione del sapere a distanza. Enna: La Moderna. Severino, S., & Lipoma, M. (2008). Metodologia e tecnica del lavoro di gruppo e del gruppo in lavoro, materiali di conoscenza e per la  S. SEVERINO 73 formazione. Enna: La Moderna editori. Shaw, M. E. (1976). Group dynamics (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill. Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the screen. Identity in the age of the internet. New York: Simon & Shuster. Turner, J. C. (1982). Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Social Identity and Inter Group Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tajifel, H. (1976). Psicologia sociale e processi sociali. In A. Palmonari (a cura di), Problemi attuali della psicologia sociale, Bologna: Il Mulino.

|